Abstract

Tamoxifen is a widely known anti-estrogen which has been employed in adjuvant treatment of early-stage, estrogen-sensitive breast cancer for over 20 years. Less well known are the effects of tamoxifen on immune function, which we discuss here. We review the growing body of evidence which demonstrates immunomodulatory effects of tamoxifen, including in vitro and in vivo studies as well as observations made in breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen. Taken together these studies suggest that tamoxifen is capable of inducing a shift from cellular (T-helper 1) to humoral (T-helper 2) immunity. Interestingly, the immunomodulatory effects of tamoxifen appear to be independent of the estrogen-receptor and may be mediated through the multi-drug resistance gene product, Permeability-glycoprotein, for which a role in immunity has recently emerged. We furthermore discuss the clinical implications of the immunomodulatory effects of tamoxifen which are twofold. First, tamoxifen may be utilized in the treatment of immune-mediated disorders, particularly of those arising from aberrant T-helper 1 cell activity, including allograft rejection, Crohn’s disease, and Th1-mediated autoimmune conditions such as diabetes mellitus, scleroderma, and multiple sclerosis. Second, given that cellular T-helper 1 immunity is targeted against cancer cells, the tamoxifen-induced shift away from cellular immunity represents a significant step in fostering a cancerogenic environment. This may limit the anti-cancer effects of tamoxifen and thus explain why tamoxifen is inferior compared to other anti-estrogens in preventing disease recurrence in early-stage breast tumors.

Keywords: Tamoxifen, immunity, modulation, Permeability-glycoprotein, P-glycoprotein

INTRODUCTION

A fundamental milestone in the treatment of breast cancer was the discovery that adjuvant anti-estrogen therapy increases survival in women with estrogen-sensitive tumors. For over two decades tamoxifen had been the first-line anti-estrogen for adjuvant hormonal treatment of breast cancer in post-menopausal women and was recently replaced by a different class of anti-estrogens, the aromatase inhibitors [1–3]. Whilst its role in breast cancer treatment may be diminishing, a growing body of evidence has defined a novel role for tamoxifen as an immune modulator. Here, we review the effects of tamoxifen on immunity, discuss underlying pharmacological mechanisms and explore potential clinical applications.

PHARMACOLOGY OF TAMOXIFEN

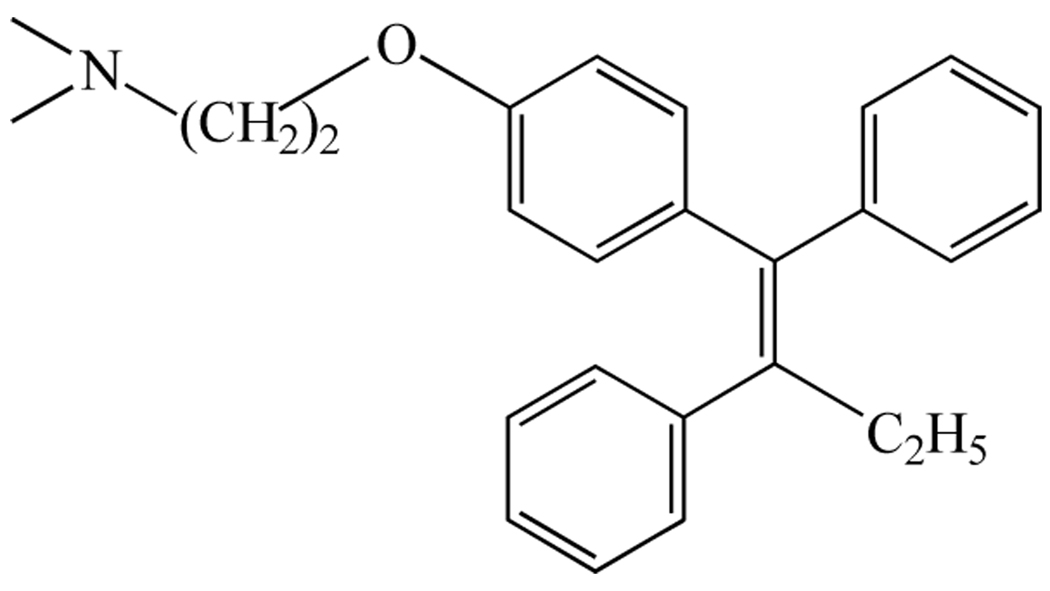

Tamoxifen, first described 1967 as a potential contraceptive agent [4], belongs to a class of molecules called triphenylethylenes derived from the estrogen agonist diethylstilbestrol which was first synthesized in 1938 [5]. The structure of tamoxifen, which is closely related to that of clomiphene, is depicted in Fig. (1). The stilboestrol-like backbone with a basic side chain is thought to mediate the anti-estrogenic effects [6]. The pharmacological targets of tamoxifen include the estrogen receptor (ER), the multi-drug resistance gene product, Permeability-glycoprotein (P-glycoprotein) [7], and the recently discovered 7-transmembrane G protein-coupled receptor 30 [8].

Fig. (1).

Chemical structure of tamoxifen.

Tamoxifen is metabolized in the liver into a variety of metabolites which are mainly estrogenic [9]. Interestingly, one of its major metabolites, 4-hydroxytamoxifen, is thought to be mutagenic by forming DNA adducts which may mediate the carcinogenic effects of tamoxifen [5].

The anti-estrogen effects of tamoxifen are mediated through the ER, which is present in the cytosol but also within cell membranes [6]. Whilst in breast tissue the action of tamoxifen on the ER is predominantly inhibitory, tamoxifen stimulates the ER in other tissues. Estrogen agonism and antagonism give rise to a variety of beneficial and adverse effects including: protection of osteoporotic bone, postmenopausal symptoms, an increased risk of endometrial cancer, thromboembolism, and strokes [5,6]. In addition to its action on the ER, tamoxifen is an inhibitor of P-glycoprotein, a 170-kDa protein located both within the cell membrane and in the cytosol [10]. P-glycoprotein is a member of the ATP-binding cassette superfamily of active transporters [11], and it has been proposed that tamoxifen inhibits P-glycoprotein through interference with its ATPase activity [12]. Traditionally associated with multi-drug resistance of certain mammalian solid tumors and hematological malignancies, a role for P-glycoprotein in immunity has recently emerged [13]. Its function in various immune cells has been demonstrated, including lymphocytes and dendritic cells [14–17]. The role of P-glycoprotein in immunity is particularly interesting for the present discussion interesting for the present discussion because P-glycoprotein inhibition may account for some of the effects of tamoxifen on immunity.

TAMOXIFEN AS AN IMMUNE MODULATOR

Yearlong clinical experience with tamoxifen suggesting it has no apparent effects on immunity is backed by studies into the effects of tamoxifen on immunity in breast cancer patients. A number of such studies from the 1980s and early 1990s failed to reveal any influence of the drug on immune function [18]. However, more recent evidence from investigations in humans, in animal models as well as observations from in vitro studies indicate the contrary (Table 1).

Table 1.

The Effects of Tamoxifen on Immunity

| Model / patient population | Key observations |

|---|---|

| Studies in humans | |

| Breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen | ↓ Natural Killer cell activity [19, 20] |

| ↑ proliferation of lymphocytes in presence of mitogen [19] | |

| ↓ number of CD4 lymphocytes [20] | |

| Case reports of a patient with Riedel’s disease | Tamoxifen induced remission [21] |

| Case report of a patient with dermatomyositis rash | Tamoxifen induced remission [22] |

| In vivo animal models | |

| Mice models that develop autoimmune diseases akin to systemic lupus erythematosus mice |

Delayed onset of disease [24] |

| ↑ survival of tamoxifen treated mice [23, 25, 26] | |

| ↓ proteinuria [23, 24, 25] | |

| ↓ auto-antibody production [23, 25] | |

| ↓ thrombocytopaenia [23, 24] | |

| Normal leukocyte count [24] | |

| ↓ number of splenic B-cells [25] | |

| ↓ serum tumor necrosis alpha levels [25] | |

| ↓ lymphadenopathy [26] | |

| ↓ renal disease on histopathological examination [23, 24, 25] | |

| Murine autoimmune encephalitis | ↓ disease symptoms [27] |

| ↓ degree of demyelination [27] | |

| ↓ myelin-induced T-cell production [27] | |

| ↓ ability of dendritic cells to stimulate myelin-specific T-cells [27] | |

| Differential effects on Th1 and Th2 cells with Th2 bias [27] | |

| Autoimmune uveitis in rats | Delayed onset of disease [28] |

| Differential effects on Th1 and Th2 cells with Th2 bias [28] | |

| In vivo models | |

| Human peripheral blood lymphocytes | ↓ alloantigen-induced T-cell proliferation [15] |

| ↓ cytokine production [15] | |

| Human monocyte-derived dendritic cells | Distinct phenotype (CD14−, CD1a−, CD80−, CD86+) [29] |

| ↓ capacity to induce proliferation amongst allogeneic T-cells [29] | |

| ↓ production of interleukin 12 upon stimulation [29] | |

| Human synovial fluid macrophages | Distinct phenotype (CD14−, CD1a−, CD80−, CD86+) [30] |

| ↓ capacity to induce proliferation amongst allogeneic T-cells [30] | |

Symbols ↑ = increase; ↓ = decrease.

Rotstein et al. and subsequently Robinson et al. reexamined the effects of tamoxifen on immunity in breast cancer patients and demonstrated modulatory effects [19,20]. Rotstein et al. studied the function of peripheral lymphocytes derived from breast cancer patients (n=23) treated with tamoxifen for 1.5 to 2 years [19]. They observed that lymphocytes from tamoxifen-treated women, compared to those from healthy controls, showed significantly reduced Natural Killer activity against a human leukemia cancer cell line (K562) whilst exhibiting a higher proliferation response in the presence of a mitogen (concanavalin A). Robinson et al. studied the effects of tamoxifen on immunity in patients with bilateral breast cancer (n=21) who were in remission and had completed radiotherapy and chemotherapy at least one year prior to the study. They observed that the relative proportion and absolute number of CD4 lymphocytes was reduced in tamoxifen treated patients, compared to untreated breast cancer patients and to healthy controls [20]. Moreover, in vitro proliferation of lymphocytes derived from tamoxifen treated patients was decreased. Finally, in vitro Natural Killer cell activity, which is increased in untreated patients, returned to levels of healthy controls in patients treated with tamoxifen. In addition to these two studies in breast cancer patients, two case reports point towards tamoxifen-mediated modulation of immune function in humans [21,22]. De et al. have presented a patient suffering from corticosteroid-resistant Riedel’s disease, a rare chronic inflammatory disease of the thyroid gland, in whom remission was induced and maintained by tamoxifen [21]. Similarly, Sereda and Werth reported successful treatment with tamoxifen of a dermatomyositis rash which was difficult to control with conventional systemic immunosuppressants [22].

Further evidence demonstrating tamoxifen-mediated immunomodulation stems from a variety of in vivo models including: mice developing autoimmune diseases akin to systemic lupus eryhthematosus [23–26]; murine experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis [27]; and experimental autoimmune uveitis in rats [28].

In experimental systemic lupus erythematosus mice (NZBxNZW F1 mice) tamoxifen was shown to increase survival; at six months of age all mice treated with tamoxifen were alive whereas 40% of untreated mice had died [23]. Other beneficial effects of tamoxifen treatment in these mice were reduced thrombocytopenia and proteinuria, less advanced renal disease (on histopathological examination) and diminished production of IgG3 auto-antibodies (against nuclear extracts and DNA) [23]. In another mouse model of experimental systemic lupus eryhthematosus (16/6 idiotype-induced disease in BALB/c female mice) tamoxifen has been shown to delay the onset disease [24]. Furthermore, tamoxifen-treated mice developed a milder disease phenotype with normal leukocyte and platelet numbers and no renal immune complex deposition. Similarly, in NZB/W F1 mice, which also develop a lupus-like disease, tamoxifen increased survival, reduced proteinuria and lessened histopathological renal disease [25]. Moreover, tamoxifen decreased numbers of splenic B-cells and serum levels of tumor necrosis factor receptors in these mice. In another mouse model of lupus, the MRL-1pr/1pr mice, tamoxifen again increased survival rates and disease severity as evidenced by diminished proteinuria, auto-antibodies (anti-double stranded DNA) and lymphadenopathy [26].

An intriguing in vivo observation was made by Bebo et al. who studied the effects of tamoxifen in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis of mice [27]. They found that tamoxifen induced a T-helper cell 2 (Th2) bias with increased Th2 transcription factors in cultures of myelin-specific lymphocytes, which suggests that tamoxifen may have differential effects on cellular (T-helper 1, Th1) and humoral (Th2) immunity. Other effects of tamoxifen treatment in autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice that Bebo et al. observed include: reduction of symptoms and the degree of demyelination; suppression of T-cell production stimulated by myelin; impairment of the ability of dendritic cells to stimulate myelin-specific T-cells. Differential effects of tamoxifen on Th1 and Th2 immunity has also been reported by de Kozak et al. who studied the effects of tamoxifen in experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis of rats [28]. The investigators found that intraocular injection of tamoxifen-loaded nanoparticles significantly inhibited onset of disease and induced a shift from a Th1- to a Th2-mediated immune response. Tamoxifen decreased gamma interferon (a Th1 cytokine) production by inguinal lymph node cells, reduced their Th1-mediated delayed hypersensitivity response and induced an antibody class switch indicative of a Th2 response. Interestingly, the immunomodulation by tamoxifen was not fully reversed by concomitant intraocular injection of 17beta-estradiol, suggesting that tamoxifen modulates immune function in part through an estrogen-independent mechanism.

That tamoxifen modulates immunity through an estrogen-independent mechanism has also been demonstrated by Komi et al. who studied the effects of tamoxifen on function of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells, key regulator cells of the immune system, in vitro [29]. Compared to control cells, dendritic cells cultured in the presence of tamoxifen developed a distinct phenotype (CD14−, CD1a−, CD80−, CD86+). Furthermore, tamoxifen-treated dendritic cells were inferior in inducing proliferation amongst allogeneic T-cells and in producing interleukin-12 upon stimulation. Interestingly, blockade of the estrogen receptor did not reverse or affect the action of tamoxifen on dendritic cells suggesting that tamoxifen exerts its effects on dendritic cells through an estrogen-independent mechanism. In a different series of experiments [30], Komi et al. demonstrated that tamoxifen also modulated the differentiation into dendritic cells of synovial fluid macrophages, obtained from the synovial fluid of patients suffering from rheumatoid arthritis. Macrophages treated in vitro with tamoxifen developed a phenotype (CD14−, CD1a−, CD80−, CD86+) similar to that of tamoxifen-treated dendritic cells [29], and the ability of tamoxifen-treated macrophages to induce proliferation of allogeneic T-cells was reduced.

Taken together, the evidence from human, in vivo and in vitro studies presented here suggests that tamoxifen modulates immune function with differential effects on Th1 and Th2 immunity, which may be mediated through an estrogen-independent mechanism. As discussed above, tamoxifen is an established inhibitor of P-glycoprotein which has recently been shown to regulate immunity [14–17]. Thus, it is conceivable that the immunomodulatory effects of tamoxifen are at least in part mediated through P-glycoprotein, which is supported by work from our laboratory [15,17].

Studying the in vitro effects on human lymphocytes of tamoxifen and the anti-P-glycoprotein monoclonal antibody (Hyb-241), we demonstrated that both tamoxifen and Hyb-241 blocked P-glycoprotein, as assessed by P-glycoprotein mediated efflux of calcein-AM dye [15]. We then showed that both tamoxifen and Hyb-241 inhibited alloantigen-induced T-cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner and reduced cytokine production measured in supernatants of the lymphocyte cultures (interleukin-2, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, gamma-interferon). In a different study, we repeated the aforementioned experiments of Komi et al. and substituted tamoxifen with the pharmacological P-glycoprotein inhibitor PSC833 [17]. We were able to reproduce the findings of Komi et al. and showed that P-glycoprotein blockade has the same effects on dendritic cell phenotype and function as tamoxifen did in the study of Komi et al. [29]. Interestingly, we also observed differential effects of P-glycoprotein inhibition of Th1 and Th2 immunity. Dendritic cells treated with the P-glycoprotein inhibitor PSC833 lost the ability to induce Th1 responses whilst retaining the ability to stimulate Th2 cells. For instance, when mixed with lymphocytes in vitro, control dendritic cells predominantly activated gamma-interferon secreting Th1 lymphocytes. In contrast, dendritic cells treated with the P-glycoprotein inhibitor mainly stimulated interleukin-5-secreting Th2 lymphocytes. Thus, similar to the effects of tamoxifen in murine experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and in experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis of rats, P-glycoprotein inhibition induced a shift from Th1 to Th2 activity in vitro.

Despite this intriguing in vitro evidence, the effectiveness of P-glycoprotein as an immune modulator in the clinic remains to be demonstrated. Tamoxifen may be an attractive P-glycoprotein inhibitor for clinical use given its favorable safety profile compared to most existing pharmacological P-glycoprotein inhibitors which have exhibited unacceptable toxicity in clinical trials [28]. Tamoxifen may also be superior to specific monocloncal antibodies in targeting P-glycoprotein dependent-immune mechanisms because as a lipophilic substance it would reach the intracellular compartment where P-glycoprotein is located within dendritic cells [10], which are key target cells of immune therapy.

Whilst we propose that tamoxifen exerts its immunomodulatory effects through P-glycoprotein, it is possible that these effects are mediated through other pathways. For example, it has been proposed that tamoxifen may modulate nuclear factor kappa beta, a key regulator of immune function, which is structurally and functionally closely related to the estrogen receptor [5]. However, this hypothesis remains to be explored experimentally. Furthermore, a novel 7-transmembrane G protein-coupled receptor 30 that binds both estrogen and tamoxifen has recently been discovered [8]. Its function is currently being defined, and it may be worth investigating whether it is linked into immune regulatory networks.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

The clinical implications of the effects of tamoxifen on immunity are twofold. First, tamoxifen may be utilized in the treatment of immune-mediated disorders. We speculate that particularly Th1-mediated disorders would be amenable to treatment with tamoxifen, including allograft rejection, Crohn’s disease, and Th1-mediated autoimmune conditions such as diabetes mellitus, scleroderma, and multiple sclerosis. Major clinical benefits would be gained if these immune disorders, which are traditionally treated with systemic immunosuppressants, responded to tamoxifen which has a comparably favorable safety and adverse effect profile. However, the long-term use of tamoxifen would be limited by its adverse effects, especially the aforementioned increased risk of developing endometrial cancer. It would therefore be important to develop tamoxifen analogues without substantial adverse effects for the treatment of chronic immunological diseases.

Second, the effects of tamoxifen on immunity may explain why compared to aromatase inhibitors tamoxifen is inferior in preventing disease recurrence in breast tumors [1–3]. The inferiority of tamoxifen remains elusive, particularly in the treatment of breast cancer requiring chemotherapy, since as a P-glycoprotein inhibitor tamoxifen would be expected to enhance the effectiveness of chemotherapy. Based on our review one may speculate that the inferiority of tamoxifen is due to a shift away from anti-cancer cellular immunity, which represents a significant step in fostering a cancerogenic environment.

CONCLUSION

Here we have discussed the growing body of evidence demonstrating a role for tamoxifen as an immune modulator. Whilst we propose that the effects of tamoxifen on immunity are mediated at least in part through P-glycoprotein, more research is required to fully understand the mechanisms underpinning the immunomodulatory effects of tamoxifen. Furthermore, because the clinical studies of immunity in breast cancer patients receiving tamoxifen were conducted in the 1980s and early 1990s it would be important to reinvestigate immunity in these patients with the whole range of modern immunological research methods. Finally, given the beneficial safety profile of tamoxifen, particularly when used short-term, it would seem appropriate to take findings from the laboratory to the bedside and to test tamoxifen in a variety of immune-mediated conditions. Tamoxifen, which has once failed as a contraceptive and then revolutionized the treatment of breast cancer, may re-emerge as a novel modulator of the immune system.

References

- 1.Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group. Tamoxifen for early breast cancer: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 1998;351:1451–1467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breast International Group (BIG) 1–98 Collaborative Group. Thurlimann B, Keshaviah A, Coates AS, Mouridsen H, Mauriac L, Forbes JF, Paridaens R, Castiglione–Gertsch M, Gelber RD, Rabaglio M, Smith I, Wardley A, Price KN, Goldhirsch A. A comparison of letrozole and tamoxifen in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353:2747–2757. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howell A, Cuzick J, Baum M, Buzdar A, Dowsett M, Forbes JF, Hoctin-Boes G, Houghton J, Locker GY, Tobias JS ATAC Trialists' Group. Results of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) trial after completion of 5 years' adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. Lancet. 2005;365:60–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17666-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jordan VC. Tamoxifen (ICI46,474) as a targeted therapy to treat and prevent breast cancer. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006;147 Suppl 1:S269–S276. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grainger DJ, Metcalfe JC. Tamoxifen: teaching an old drug new tricks? Nat. Med. 1996;4:381–385. doi: 10.1038/nm0496-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jordan VC. The science of selective estrogen receptor modulators: concept to clinical practice. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006;12:5010–5013. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callaghan R, Higgins CF. Interaction of tamoxifen with the multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein. Br. J. Cancer. 1995;71:294–299. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prossnitz ER, Oprea TI, Sklar LA, Arterburn JB. The ins and outs of GPR30: a transmembrane estrogen receptor. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008;109:350–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clarke R, Leonessa F, Welch JN, Skaar TC. Cellular and molecular pharmacology of antiestrogen action and resistance. Pharmacol. Rev. 2001;53:25–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schroeijers AB, Reurs AW, Scheffer GL, Stam AG, de Jong MC, Rustemeyer T, Wiemer EA, de Gruijl TD, Scheper RJ. Up-regulation of drug resistance-related vaults during dendritic cell development. J. Immunol. 2002;168:1572–1578. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gottesman MM, Pastan I. Biochemistry of multidrug resistance mediated by the multidrug transporter. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1993;62:385–427. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.002125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rao US, Fine RL, Scarborough GA. Antiestrogens and steroid hormones: substrates of the human P-glycoprotein. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1994;48:287–292. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pendse S, Sayegh MH, Frank MH. P-glycoprotein - a novel therapeutic target for immunomodulation in clinical transplantation and autoimmunity? Curr. Drug. Targets. 2003;4:469–476. doi: 10.2174/1389450033490894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gollapud S, Gupta S. Anti-P-glycoprotein antibody-induced apoptosis of activated peripheral blood lymphocytes: a possible role of P-glycoprotein in lymphocyte survival. J. Clin. Immunol. 2001;21:420–430. doi: 10.1023/a:1013177710941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frank MH, Denton MD, Alexander SI, Khoury SJ, Sayegh MH, Briscoe DM. Specific MDR1 P-glycoprotein blockade inhibits human alloimmune T cell activation in vitro. J. Immunol. 2001;166:2451–2459. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pilarski LM, Paine D, McElhaney JE, Cass CE, Belch AR. Multidrug transporter P-glycoprotein 170 as a differentiation antigen on normal human lymphocytes and thymocytes: modulation with differentiation stage and during aging. Am. J. Hematol. 1995;49:323–335. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830490411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pendse SS, Behjati S, Schatton T, Izawa A, Sayegh MH, Frank MH. P-Glycoprotein Functions as a Differentiation Switch in Antigen Presenting Cell Maturation. Am. J. Transplant. 2006;6:2884–2893. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joensuu H, Toivanen A, Nordman E. Effect of tamoxifen on immune functions. Cancer Treat. Rep. 1986;70:381–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rotstein S, Blomgren H, Petrini B, Wasserman J, von Stedingk LV. Influence of adjuvant tamoxifen on blood lymphocytes. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 1988;12:75–79. doi: 10.1007/BF01805743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson E, Rubin D, Mekori T, Segal R, Pollack S. In vivo modulation of natural killer cell activity by tamoxifen in patients with bilateral primary breast cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 1993;37:209–212. doi: 10.1007/BF01525437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De M, Jaap A, Dempster J. Tamoxifen therapy in steroid-resistant Riedels disease. Scott. Med. J. 2002;47:12–13. doi: 10.1177/003693300204700106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sereda D, Werth VP. Improvement in dermatomyositis rash associated with the use of antiestrogen medication. Arch. Dermatol. 2006;142:70–72. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sthoeger ZM, Zinger H, Mozes E. Beneficial effects of the anti-oestrogen tamoxifen on systemic lupus erythematosus of (NZBxNZW)F1 female mice are associated with specific reduction of IgG3 autoantibodies. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2003;62:341–346. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.4.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sthoeger ZM, Bentwich Z, Zinger H, Mozes E. The beneficial effect of the estrogen antagonist, tamoxifen, on experimental systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Rheumatol. 1994;21:2231–2238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu WM, Lin BF, Su YC, Suen JL, Chiang BL. Tamoxifen decreases renal inflammation and alleviates disease severity in autoimmune NZB/W F1 mice. Scand. J. Immunol. 2000;52:393–400. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2000.00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu WM, Suen JL, Lin BF, Chiang BL. Tamoxifen alleviates disease severity and decreases double negative T cells in autoimmune MRL-lpr/lpr mice. Immunology. 2000;100:110–118. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00998.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bebo BF, Jr, Dehghani B, Foster S, Kurniawan A, Lopez FJ, Sherman LS. Treatment with selective estrogen receptor modulators regulates myelin specific T-cells and suppresses experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Glia. 2008 Nov 20; doi: 10.1002/glia.20805. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Kozak Y, Andrieux K, Villarroya H, Klein C, Thillaye-Goldenberg B, Naud MC, Garcia E, Couvreur P. Intraocular injection of tamoxifen-loaded nanoparticles: a new treatment of experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis. Eur. J. Immunol. 2004;34:3702–3712. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Komi J, Lassila O. Nonsteroidal anti-estrogens inhibit the functional differentiation of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Blood. 2000;95:2875–2882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Komi J, Möttönen M, Luukkainen R, Lassila O. Non-steroidal anti-oestrogens inhibit the differentiation of synovial macrophages into dendritic cells. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2001;40:185–191. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/40.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krishna R, Mayer LD. Multidrug resistance (MDR) in cancer. Mechanisms, reversal using modulators of MDR and the role of MDR modulators in influencing the pharmacokinetics of anticancer drugs. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2000;11:265–283. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0987(00)00114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]