Abstract

Lung cancer is a leading cause of cancer death, where the amplification of oncogenes contributes to tumorigenesis. Genomic profiling of 128 lung cancer cell lines and tumors revealed frequent focal DNA amplification at cytoband 14q13.3, a locus not amplified in other tumor types. The smallest region of recurrent amplification spanned the homeobox transcription factor TITF1 (thyroid transcription factor 1; also called NKX2-1), previously linked to normal lung development and function. When amplified, TITF1 exhibited increased expression at both the RNA and protein levels. Small interfering RNA (siRNA)- mediated knockdown of TITF1 in lung cancer cell lines with amplification led to reduced cell proliferation, manifested by both decreased cell-cycle progression and increased apoptosis. Our findings indicate that TITF1 amplification and overexpression contribute to lung cancer cell proliferation rates and survival and implicate TITF1 as a lineage-specific oncogene in lung cancer.

Keywords: TITF1, lineage-specific oncogene, genomic profiling, lung cancer, TTF-1, NKX2-1

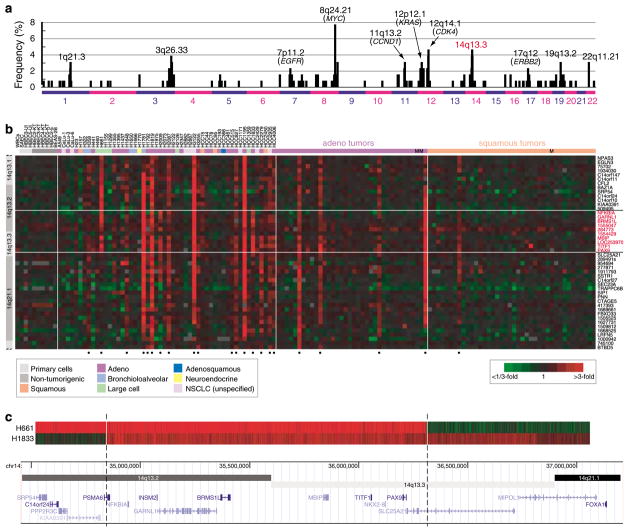

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the United States (Jemal et al., 2007). In lung cancers, the amplification of oncogenes such as MYC, KRAS, MET, EGFR, ERBB2, CCND1 and CDK4 contributes to tumor development and progression, and amplified genes have become important targets for molecularly-directed therapies (Sato et al., 2007). To discover novel amplicons, we profiled 52 non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines and 76 NSCLC tumors (36 adenocarcinomas including 2 metastases, and 40 squamous cell carcinomas including 1 metastasis), by array-based comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) on cDNA microarrays (Pollack et al., 1999) covering ~22 000 human genes with a median inter-probe distance of ~30 kb. The most frequent focal DNA amplification not associated with a previously known oncogene occurred at cytoband 14q13.3 (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

TITF1 is focally amplified in lung cancer. (a) Frequency plot of cytobands harboring high-level DNA amplification in NSCLC cell lines and tumors (Supplementary Table 3). Cell lines were obtained from the Hamon Center for Therapeutic Oncology Research, UT Southwestern Medical Center. Tumors were banked at the University Hospital Charité, Berlin, Germany, with patient consent and Institutional Review Board approval, and DNA was extracted from several 30 μm cryostat tissue sections containing ≥ 70% tumor cells. CGH was performed on cDNA microarrays from the Stanford Functional Genomics Facility containing 39 632 human cDNAs (representing 22 279 different mapped human genes/cDNAs), using our published protocol (Pollack et al., 2002). Map positions for arrayed cDNA clones were assigned using the NCBI genome assembly, accessed through the UCSC genome browser database (NCBI Build 36) (Kent et al., 2002). High-level DNA amplification was defined as tumor/normal aCGH ratios >3; selected cytobands with frequent amplification are indicated. The complete microarray data set is accessible from the GEO repository (GSE9995). (b) Genomic profiles by CGH on cDNA microarrays for NSCLC cell lines and tumors, histologies indicated (M = metastasis), for a segment of chromosome 14q13.1–q21.1. Genes are ordered by genome position. Red indicates positive tumor/normal aCGH ratios (scale shown), and samples called gained, using the fused lasso method (Tibshirani and Wang, 2008), at 14q13.3 are marked below by closed circles. Genes and ESTs (IMAGE clone ID shown) on the microarray residing within the amplicon core are highlighted by red text. (c) Genomic profiles by CGH on an Agilent (Santa Clara, CA, USA) high-definition custom microarray tiling 14q13.2–q21.1. The arrays comprised 10 614 probes tiling 3.3Mb (nt 34 457 000–37 750 000) at 14q13.2–q21.1 with an average inter-probe spacing of 310 nt, with an additional 32 451 probes spanning the remaining genome for data normalization. DNAs were labeled as above, then hybridized to the array following the manufacturer’s instructions. Arrays were scanned using an Agilent G2505B scanner and data extracted and normalized using Agilent Feature Extraction software (version 9.1) with default settings. Shown are two informative samples defining the amplicon boundaries, mapped onto the UCSC genome browser. The smallest region of recurrent amplification spans eight named genes. cDNA, complementary DNA; CGH, comparative genomic hybridization; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; UCSC, University of California Santa Cruz.

Gain at 14q13.3 was present in 17 of 52 (33%) lung cancer cell lines, where it was more often observed in cell lines derived from adenocarcinomas (including bronchioloalveolar carcinomas) compared to other histologies (P = 0.04, Fisher’s exact test; unspecified NSCLCs excluded from the analysis) (Figure 1b). 14q13.3 gain was also detectable in 4 of 36 (11%) lung adenocarcinomas and in 1 of 40 (3%) squamous cell carcinomas (all samples with gain were primary tumors). The lower frequencies observed in patient tumors may reflect an under-calling of gains due to contaminating non-cancerous cells in tumor samples or alternatively to a bias in the tumors attempted or successfully established as cultures or to selective pressures on cultured cells. Gain of 14q13.3 was significantly associated with the presence of EGFR-activating mutations (P = 0.03, Mann–Whitney U-test) (but not KRAS or TP53 mutations), as well as the presence of specific DNA gains/losses elsewhere in the genome, including gain at 5p15.33 (TERT) (Supplementary Table 1). Notably, we have not observed the 14q13.3 locus to be amplified in other tumor types that we have profiled on the same platform, including cancers (totaling 385 specimens) of the breast, prostate, colon and pancreas (Bashyam et al., 2005; Bergamaschi et al., 2006; Lapointe et al., 2007; unpublished data), suggesting that the putative driver oncogene(s) within this locus is lung cancer specific.

The smallest region of recurrent amplification, corroborated by CGH on a custom high-definition oligonucleotide microarray with probes spanning 14q13.2–q13.3 at 300 bp intervals (Figure 1c), included just eight named genes: NFKBIA, INSM2, GARNL1, BRMS1L, MBIP, TITF1, NKX2-8 and PAX9. Because TITF1 (thyroid transcription factor 1; also called TTF-1 and NKX2-1) was known to participate in normal lung development (Kimura et al., 1996) and had been characterized as a histological marker of lung adenocarcinoma (Travis et al., 2004), we sought to explore a possible functional connection of TITF1 gene amplification with lung cancer.

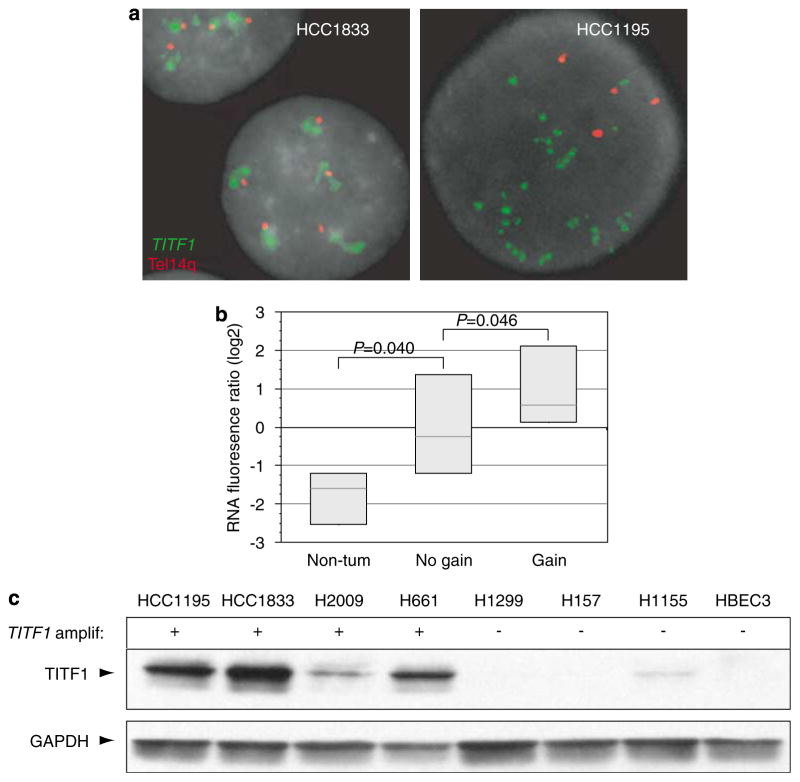

Consistent with an oncogenic role, TITF1 exhibited increased expression at both the RNA (P = 0.046, Mann–Whitney U-test) (Figure 2b) and protein level (Figure 2c) in NSCLC cell lines with amplification. Notably, while other genes at 14q13.3 also exhibited increased expression when amplified, TITF1 was the only well-measured gene that also exhibited significantly increased expression in tumorigenic compared to non-tumorigenic cell lines (Figure 2b and Supplementary Table 2). Sequencing of the TITF1 open reading frame (and splice sites) from four NSCLC cell lines (HCC1195, HCC1833, H2009 and H661) with amplification revealed no DNA mutations, indicating that amplification- driven overexpression of the wild-type gene product would be of relevance.

Figure 2.

TITF1 is overexpressed when amplified in lung cancer lines. (a) FISH validation of TITF1 amplification in select NSCLC cell lines. FISH was performed using Vysis (Downers Grove, IL, USA) reagents according to the manufacturer’s protocols. A locus-specific BAC mapping to TITF1 at 14q13.3 (RP11-1083E2; BACPAC Resources Centre, Oakland, CA, USA) was labeled with SpectrumGreen, and co-hybridized with a SpectrumOrange-labeled telomere–14q probe (Vysis). Slides were counterstained with DAPI and imaged using an Olympus BX51 fluorescence microscope with Applied Imaging (San Jose, CA, USA) Cytovision 3.0 software. DNA amplification is evidenced by increased TITF1 (green)/telomere–14q (red) signals (HCC1195, right) or by TITF1 signal clusters (HCC1833, left). (b) mRNA levels of TITF1, measured by microarray, are elevated in NSCLC cell lines with TITF1 amplification and also in comparison to primary and immortalized (but non-tumorigenic) lung epithelial cultures (Ramirez et al., 2004). Gene expression profiling was performed as described (Lapointe et al., 2004). Reported fluorescence ratios for TITF1 are normalized to the average TITF1 expression level across all samples. Box plots show 25th, 50th and 75th percentiles of expression. P-values (Mann–Whitney U-test) are indicated. (c) Western blot analysis of representative NSCLC cell lines indicates that TITF1 is overexpressed at the protein level when amplified. Electrophoresis and blotting were performed as described (Kao and Pollack, 2006). TITF1 (~47 kDa) and GAPDH (loading control) were detected using anti-TITF1 rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and anti-GAPDH rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:5000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:20 000; Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Detection was carried out using the ECL kit (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA). FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; TITF1, thyroid transcription factor 1.

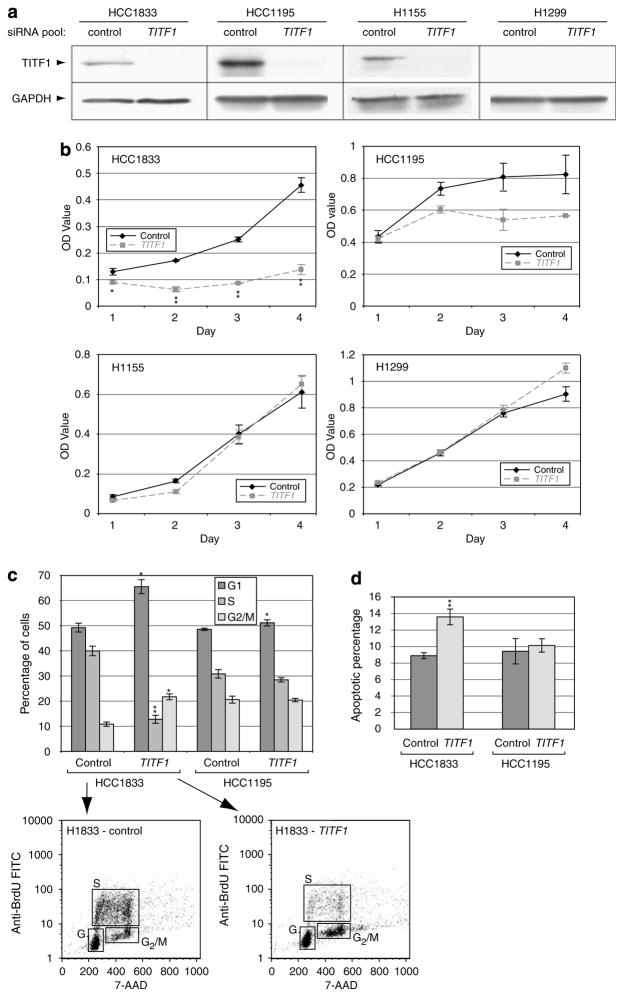

To assess the functional significance of TITF1 amplification and overexpression, we used RNA interference to target TITF1 knockdown in two lung cancer cell lines, HCC1833 and HCC1195, with TITF1 amplification validated by fluorescence in situ hybridization (Figure 2a). Transfection of a Dharmacon On- TARGETplus pool of four different short interfering RNAs (siRNAs), designed and chemically modified to minimize off-target effects (Birmingham et al., 2006; Jackson et al., 2006), led to decreased TITF1 protein (Figure 3a) and decreased cell proliferation compared to a negative control siRNA pool (Figure 3b). Transfection of individual siRNAs from the same pool showed comparable effects (data not shown). In contrast, siRNA transfection of a lung cancer cell line (H1155) without TITF1 amplification but with detectable expression did not diminish cell proliferation, indicating the functional importance of amplification-driven overexpression. Transfection of a cell line (H1299) without amplification or detectable expression also did not alter cell proliferation, supporting the specificity of TITF1 targeting (Figure 3b). Similar negative results were observed upon transfection of a non-lung cancer cell line (colorectal cancer line SW48; data not shown). In the lung cancer cell lines with 14q13.3 amplification, the TITF1-targeted reduction in cell proliferation was attributable to both decreased cell-cycle progression (as evidenced by decreased S-phase fraction with G1 block; Figure 3c) and increased apoptosis (Figure 3d). The effects were more pronounced in HCC1833 compared to HCC1195.

Figure 3.

TITF1 amplification/overexpression contributes to cell proliferation. (a) Confirmation of siRNA-mediated knockdown of target protein TITF1 by western blot. On-TARGETplus siRNAs targeting TITF1, along with a negative control siRNA pool (ON-TARGETplus siCONTROL Non-targeting Pool), were obtained from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO, USA). Sequences of siRNAs are listed in Supplementary Table 4. Cell lines were maintained at 37 °C in RPMI-1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum. For transfection, 125 000–200 000 cells were seeded per well in a six-well plate and transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, using a final concentration of 50 nM siRNA for 6 h. Cell lysates were harvested 72 h post-transfection; GAPDH served as a loading control. (b) TITF1 knockdown results in decreased cell proliferation in cells with (HCC1833, HCC1195) but not without (H1155, H1299) TITF1 amplification. At 24, 48, 72 and 96 h post-transfection, cell proliferation was quantified by colorimetry based on the metabolic cleavage of the tetrazolium salt WST-1 in viable cells, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Transfections were performed in replicate and mean (±1 s.d.) OD reported. (c) TITF1 knockdown reduces cell-cycle progression, evidenced by decreased S-phase fraction with G1 block. At 72 h post-transfection, cell-cycle distribution analysis was performed using the BrdU-FITC Flow kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were incubated with 10 μM BrdU at 37 °C for 4 h prior to processing for analysis. Anti-BrdU FITC and 7- aminoactinomycin D (for total DNA content) stainings were scored by FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) and analysed using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences). Transfections were performed in triplicate and mean (±1 s.d.) cell-cycle fractions reported. Representative FAC S plots are also shown. (d) TITF1 knockdown leads to increased apoptosis. At 72 h post-transfection, apoptosis was assayed by annexin-V staining and quantified by flow cytometry using the Vybrant Apoptosis Assay kit (Invitrogen) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Transfections were performed in triplicate, and mean (±1 s.d.) percent apoptosis reported. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01 (Student’s t-test; TITF1 compared to control). BrdU, bromodeoxyuridine; siRNA, small interfering RNA; TITF1, thyroid transcription factor 1.

TITF1 is a tissue-specific transcription factor required for branching morphogenesis during normal lung development, as well as for the differentiation of pulmonary epithelial cells, as marked by the expression of surfactant proteins (which are among its transcriptional targets) (Bohinski et al., 1994; Kimura et al., 1996; Minoo et al., 1999). In the developing and adult lung, TITF1 is expressed mainly in peripheral airway cells and small-sized bronchioles (Yatabe et al., 2002). TITF1 has also been found to be expressed in approximately 40–50% of NSCLCs, more frequently in adenocarcinomas compared to squamous cell carcinomas and with expression linked to more favorable prognosis in some but not all studies (Puglisi et al., 1999; Tan et al., 2003). Immunostaining of TITF1 is used as the major lineage-specific marker to distinguish primary lung adenocarcinoma from metastatic adenocarcinoma to the lung (Travis et al., 2004). Our findings indicate that TITF1 amplification and resultant overexpression contribute to increased cell proliferation rates and survival in lung cancer cells, and now implicate TITF1 as a lung cancer-specific oncogene.

Recently, Tanaka et al. (2007) reported that TITF1 knockdown led to decreased colony formation, which they attributed to increased apoptosis in a cell line (NCIH358) with TITF1 expression but (in their hands) no amplification. In our study, we showed that TITF1 amplification led to protein overexpression and sensitivity to siRNA-mediated knockdown, highlighting the role of TITF1 amplification as a critical event in the pathogenesis of a subset of lung cancers. Tanaka et al. also reported increased gene dosage of TITF1, measured by Southern blot and TaqMan PCR, in 2% of primary lung adenocarcinomas. The higher proportion we observed (11%) may reflect a higher sensitivity of aCGH (where multiple probes per locus are considered), or differences between the patient cohorts. Importantly, aCGH analysis also permitted us to define the 14q13 amplicon structure and boundaries, where our studies placed TITF1 squarely within the amplicon core, consistent with a ‘driver’ role.

Given its connection to pulmonary epithelium differentiation, an oncogenic role of TITF1 might seem counterintuitive. However, other tissue-specific transcription factors have been found to be amplified in cancers, including MITF in melanoma (Garraway et al., 2005), AR in prostate cancer (Visakorpi et al., 1995) and ESR1 in breast cancer (Holst et al., 2007). The deregulated expression of such transcription factors, with normal roles in lineage proliferation or survival, may be required for tumor survival and progression in some cellular and genetic contexts, reflecting a state of ‘lineage dependency’ (Garraway and Sellers, 2006). More generally, the deregulated expression of transcription factors with roles in normal development reflects the principle of ‘oncology recapitulates ontogeny’ (Lechner et al., 2001).

Our finding that 14q13.3 amplification occurs mainly in lung adenocarcinomas (and their derived cell lines), the same histology in which TITF1 expression (even when not amplified) is predominantly restricted, is consistent with TITF1 being the primary driver oncogene within 14q13.3. Nonetheless, other genes within the 14q13 amplicon may contribute to tumorigenesis. Notably, also residing within the amplicon core are two other homeodomain-containing genes, NKX2-8 and PAX9; the former of which has been recently implicated in the control of normal lung development (Tian et al., 2006). Our preliminary data (not shown) indicate that PAX9 is overexpressed when amplified in some NSCLC cell lines, and exhibits positive immunostaining in a subset of lung tumors. In another context, TITF1 and the paired-box member PAX8 have been shown to cooperatively activate the expression of thyroid-specific target genes (Miccadei et al., 2002). It is tempting to speculate that co-amplification of NKX2-8 and/or PAX9, together with TITF1, may contribute to lung cancer development or progression. Indeed, very recently Kendall et al. (2007), who discovered the same 14q13.3 amplicon, reported that both NKX2-8 and PAX9 can synergize with TITF1 to promote proliferation of immortalized human lung epithelial cells.

Future investigations are required to more precisely define the transcriptional effectors and pathways through which TITF1 mediates its oncogenic function. Nonetheless, our genomic profiling and functional studies implicate TITF1 as a lineage-specific oncogene in lung cancer, a discovery that may lead to new opportunities for therapeutic intervention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the SFGF for microarray manufacture, the SMD for database support, Ilana Galperin (Stanford Cytogenetics Laboratory) for assistance with FISH analysis and Eon Rios for assistance with FACS analysis. We also thank the members of the Pollack lab for helpful discussions. This work was supported in part by grants from the NIH: R01 CA97139 (JRP), T32 CA09151 (KAK), SPORE P50CA70907 (JDM), the DOD (JDM), the Vital, Anderson and Longenbaugh Foundations (JDM) and the Deutsche Krebshilfe: 10-2210-Pe4 (IP).

Footnotes

Note added in proof : The TITF1 amplicon was also recently identified by Weir et al. (2007).

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Oncogene website (http://www.nature.com/onc).

References

- Bashyam MD, Bair R, Kim YH, Wang P, Hernandez-Boussard T, Karikari CA, et al. Array-based comparative genomic hybridization identifies localized DNA amplifications and homozygous deletions in pancreatic cancer. Neoplasia. 2005;7:556–562. doi: 10.1593/neo.04586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergamaschi A, Kim YH, Wang P, Sorlie T, Hernandez-Boussard T, Lonning PE, et al. Distinct patterns of DNA copy number alteration are associated with different clinicopathological features and gene-expression subtypes of breast cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2006;45:1033–1040. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmingham A, Anderson EM, Reynolds A, Ilsley-Tyree D, Leake D, Fedorov Y, et al. 3′ UTR seed matches, but not overall identity, are associated with RNAi off-targets. Nat Methods. 2006;3:199–204. doi: 10.1038/nmeth854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohinski RJ, Di Lauro R, Whitsett JA. The lung-specific surfactant protein B gene promoter is a target for thyroid transcription factor 1 and hepatocyte nuclear factor 3, indicating common factors for organ-specific gene expression along the foregut axis. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:5671–5681. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.5671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garraway LA, Sellers WR. Lineage dependency and lineage-survival oncogenes in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:593–602. doi: 10.1038/nrc1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garraway LA, Widlund HR, Rubin MA, Getz G, Berger AJ, Ramaswamy S, et al. Integrative genomic analyses identify MITF as a lineage survival oncogene amplified in malignant melanoma. Nature. 2005;436:117–122. doi: 10.1038/nature03664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holst F, Stahl PR, Ruiz C, Hellwinkel O, Jehan Z, Wendland M, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha (ESR1) gene amplification is frequent in breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2007;39:655–660. doi: 10.1038/ng2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AL, Burchard J, Leake D, Reynolds A, Schelter J, Guo J, et al. Position-specific chemical modification of siRNAs reduces ‘off-target’ transcript silencing. RNA. 2006;12:1197–1205. doi: 10.1261/rna.30706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:43–66. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao J, Pollack JR. RNA interference-based functional dissection of the 17q12 amplicon in breast cancer reveals contribution of coamplified genes. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2006;45:761–769. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall J, Liu Q, Bakleh A, Krasnitz A, Nguyen KC, Lakshmi B, et al. Oncogenic cooperation and coamplification of developmental transcription factor genes in lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:16663–16668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708286104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, Roskin KM, Pringle TH, Zahler AM, et al. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002;12:996–1006. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura S, Hara Y, Pineau T, Fernandez-Salguero P, Fox CH, Ward JM, et al. The T/ebp null mouse: thyroid-specific enhancer-binding protein is essential for the organogenesis of the thyroid, lung, ventral forebrain, and pituitary. Genes Dev. 1996;10:60–69. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapointe J, Li C, Giacomini CP, Salari K, Huang S, Wang P, et al. Genomic profiling reveals alternative genetic pathways of prostate tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8504–8510. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapointe J, Li C, Higgins JP, van de Rijn M, Bair E, Montgomery K, et al. Gene expression profiling identifies clinically relevant subtypes of prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:811–816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304146101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechner JF, Fugaro JM, Wong Y, Pass HI, Harris CC, Belinsky SA. Perspective: cell differentiation theory may advance early detection of and therapy for lung cancer. Radiat Res. 2001;155:235–238. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2001)155[0235:pcdtma]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miccadei S, De Leo R, Zammarchi E, Natali PG, Civitareale D. The synergistic activity of thyroid transcription factor 1 and Pax 8 relies on the promoter/enhancer interplay. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:837–846. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.4.0808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minoo P, Su G, Drum H, Bringas P, Kimura S. Defects in tracheoesophageal and lung morphogenesis in Nkx2.1(−/−) mouse embryos. Dev Biol. 1999;209:60–71. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack JR, Perou CM, Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, Pergamenschikov A, Williams CF, et al. Genome-wide analysis of DNA copy-number changes using cDNA microarrays. Nat Genet. 1999;23:41–46. doi: 10.1038/12640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack JR, Sorlie T, Perou CM, Rees CA, Jeffrey SS, Lonning PE, et al. Microarray analysis reveals a major direct role of DNA copy number alteration in the transcriptional program of human breast tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12963–12968. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162471999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puglisi F, Barbone F, Damante G, Bruckbauer M, Di Lauro V, Beltrami CA, et al. Prognostic value of thyroid transcription factor-1 in primary, resected, non-small cell lung carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 1999;12:318–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez RD, Sheridan S, Girard L, Sato M, Kim Y, Pollack J, et al. Immortalization of human bronchial epithelial cells in the absence of viral oncoproteins. Cancer Res. 2004;64:9027–9034. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Shames DS, Gazdar AF, Minna JD. A translational view of the molecular pathogenesis of lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:327–343. doi: 10.1097/01.JTO.0000263718.69320.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan D, Li Q, Deeb G, Ramnath N, Slocum HK, Brooks J, et al. Thyroid transcription factor-1 expression prevalence and its clinical implications in non-small cell lung cancer: a high-throughput tissue microarray and immunohistochemistry study. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:597–604. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(03)00180-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H, Yanagisawa K, Shinjo K, Taguchi A, Maeno K, Tomida S, et al. Lineage-specific dependency of lung adenocarcinomas on the lung development regulator TTF-1. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6007–6011. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian J, Mahmood R, Hnasko R, Locker J. Loss of Nkx2.8 deregulates progenitor cells in the large airways and leads to dysplasia. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10399–10407. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani R, Wang P. Spatial smoothing and hot spot detection for CGH data using the fused lasso. Biostatistics. 2008;9:18–29. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxm013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis WD, Brambilla E, Muller-Hermelink HK, Harris CC. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. IARC Press; Lyon: 2004. Pathology & Genetics: Tumours of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart. [Google Scholar]

- Visakorpi T, Hyytinen E, Koivisto P, Tanner M, Keinanen R, Palmberg C, et al. In vivo amplification of the androgen receptor gene and progression of human prostate cancer. Nat Genet. 1995;9:401–406. doi: 10.1038/ng0495-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir BA, Woo MS, Getz G, Perner S, Ding L, Beroukhim R, et al. Characterizing the cancer genome in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2007;450:893–898. doi: 10.1038/nature06358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yatabe Y, Mitsudomi T, Takahashi T. TTF-1 expression in pulmonary adenocarcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:767–773. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200206000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.