Abstract

Although it is commonly assumed that alcohol consumption has a significant impact on employee absenteeism, the nature of the alcohol-absence relationship remains poorly understood. Proposing that alcohol impairment likely serves as a key mechanism linking drinking and work absence, we posit that this relationship is likely governed less by the amount of alcohol consumed, and more by the way it is consumed. Using a prospective study design and a random sample of urban transit workers, our results indicate that the frequency of heavy episodic drinking over the previous month is positively associated with the number of days of absence recorded in the subsequent 12 month period, whereas modal consumption (a metric capturing the typical amount of alcohol consumed in a given period of time) is not. In addition, consistent with both volitional treatments of absenteeism and social exchange theory, perceived co-worker support was found to attenuate, and supervisory support to amplify, the link between the frequency of heavy episodic drinking and absenteeism.

Keywords: Absenteeism, Alcohol Consumption, Peer Support, Supervisor Support

Employee absenteeism takes a heavy toll on worker productivity in the United States, costing employers approximately $225.8 billion per year or $1685 per employee per year (Stewart et al., 2003). Although employee drinking is widely assumed to serve as an important antecedent of such employee behavior (General Workplace Impact, 2003), as noted by Frone (2008), “a broader review of more recent studies shows a fair amount of inconsistency regarding this relation” (p. 234). Indeed, with the link between drinking and workplace absenteeism continuing to perplex scholars, a number of absence researchers have come to view the impact of drinking on employee absenteeism as being “more complex” than the impact of other individual and workplace factors on absenteeism (Harrison & Martocchio, 1998; Gmel & Rehm, 2003). Underlying this complexity are two main issues.

The first issue concerns the assumed nature of the alcohol-absenteeism relationship, and in particular, the degree to which the mechanism underlying this relationship is governed by the amount of alcohol consumed as opposed to the way it is consumed. To date, nearly all of the studies examining the alcohol-absence relationship have focused on the former, with most based on the logic that modal alcohol consumption (the typical quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption) is linked to absence via the increased risk of chronic health problems and/or injury associated with higher modal levels of consumption (Harrison & Martocchio, 1998). In contrast, despite recent evidence by McFarlin and Fals-Stewart (2002) that the alcohol-absenteeism relationship may be governed by a short-term or acute impairment mechanism, research has largely neglected the possible role of the pattern of alcohol consumption (i.e., how much is consumed at a particular time) as a predictor of absenteeism. Assuming that it is impairment or some impairment-related consequence (e.g., injury) that deters employees from reporting to work, then it is likely that the frequency of impairment-producing episodes of drinking (i.e., heavy drinking) would be more predictive of absence than the average or modal level of consumption. Accordingly, as suggested by Harrison & Martocchio (1998) the nature of the alcohol-absence relationship may be complicated by divergent theories regarding the dynamic driving such a relationship and the way in which to operationalize drinking so as to best capture that dynamic.

The second issue concerns the elasticity of the alcohol-absence relationship, and in particular, the degree to which it may be conditional upon the relational context at work. Several scholars (e.g., Ames, Grube, & Moore, 2000; French, Zarkin, Hartwell, & Bray, 1995) suggest that the impact of alcohol consumption on workplace absenteeism is likely to vary as a function of workplace conditions, and that until theoretical models specify such moderation effects, we are unlikely to fully understand the true nature of the alcohol-absence relationship. For example, since workplace absenteeism may have important implications for the individual employee’s co-workers (e.g., forcing them to work overtime or perform tasks for which they may lack adequate training; Goodman & Garber [1988]), depending on the nature of the relationship between the alcohol-consuming individual and his/her workplace peers, the former may feel more or less obligated to attend work regardless of the amount of alcohol that s/he has consumed. Similarly, the degree to which alcohol consumption may serve as an antecedent of workplace absenteeism may depend on the individual worker’s relations with his/her supervisor. As noted by Blum, Roman, and Martin (1993), the level of alcohol consumption may be less predictive of absence among employees who deem their supervisors to focus more on attendance policy enforcement, since such employees are likely to use “presenteeism” as “an effective screen” by which to avoid identification as a potential “troubled worker.” Such ideas are consistent with recent research on employee absenteeism suggesting that the relational context at work may serve as a key factor conditioning the impact of a variety of individual and workplace factors on absenteeism (Bamberger & Biron, 2007; Rentsch & Steel, 2003).

Theory-grounded research aimed at addressing these two issues is important for a number of reasons. First, although several researchers report a positive alcohol-absence relationship (e.g., Lennox, Steele, Zarkin, & Bray, 1998; McFarlin & Fals-Stewart, 2002), as noted by Frone (2008), the research is limited and findings remain inconsistent. Thus, insights into the nature of the alcohol-absenteeism relationship may help explain why other researchers report U-shaped (Marmot, North, Feeney, & Head, 1993; Vahtera, Kivimaki, Pentti, & Theorell, 2000), null (e.g., Ames, Grube & Moore, 1997; Vasse, Nijhuis, & Kok, 1998; Moore, Grunberg, & Greenberg, 2000; Foster & Vaughan, 2005), and even inverse relationships (Blum et al., 1993; Stewart et al., 2003). Insights into the nature of the alcohol-absenteeism relationship may also enhance the ability of policy makers and managers to more effectively allocate resources aimed at addressing employee absence problems and their root causes (Foster & Vaughan, 2005). Second, given that the alcohol-absence relationship focuses on a form of alcohol consumption (i.e., off-the-job drinking) that is more difficult for management to control, a better understanding of how relational conditions in the workplace may attenuate or amplify this relationship may provide a basis for the development of more effective absence-control policies and practices.

In this context, the current study addresses the first issue by generating a model of the alcohol-absenteeism relationship encompassing variables capturing both the amount of alcohol consumed and the way in which it is consumed. Drawing from social exchange theory (Blau, 1964), we address the second issue by generating hypotheses regarding the role of co-worker and supervisor support as conditioning factors in the alcohol-absence relationship. Negative binomial regression analysis is used to test these hypotheses on the basis of archival absence data collected in the context of a prospective study design.

Alcohol Use and Workplace Absenteeism: Main Effects

As noted above, researchers exploring the association between employee drinking and absenteeism have tended to conceptualize the former in terms of the modal level of alcohol consumption, a metric aimed at capturing the typical amount of alcohol the individual consumes in a given period of time. In most studies, this has typically been operationalized in terms of the product of: (a) the average number of servings consumed on those days when the individual drinks (i.e., modal quantity), and (b) the number of days in the past week (e.g., Vasse et al., 1998) or month (e.g., Blum et al., 1993) alcohol was consumed (i.e., frequency). Moreover, based on consistent findings that alcohol consumption patterns among adults remain relatively stable over time (Webb et al., 1994; Hasin, Van Rossem, McCloud, & Endicott, 1997; Gruenewald & Johnson, 2006; Bacharach, Bamberger, Doveh, & Cohen, 2007), much of this research assumes that modal consumption remains generalizable over the period of time over which absence is assessed. For example, based on such an implicit assumption, Vasse et al. (1998) examine the relationship between modal weekly alcohol consumption and the rate of absence in the prior six months, while Webb et al. (1994) examine the relationship between modal weekly alcohol consumption and the rate of injury-related absence in the subsequent 12 months.

In most of these studies, the hypothesized linkage between employee drinking and absence is grounded on an illness and/or injury logic. More specifically, these studies propose that a higher level of modal alcohol consumption has an adverse impact on employee health which in turn increases the probability and/or duration of workplace absence. Indeed, research has consistently shown that excessive drinking over time increases the risk of a wide variety of chronic health problems including liver, musculoskeletal and cardiovascular problems (Hanebuth, Meinel, & Fischer, 2006; Jones, Casswell, & Zhang, 1995). Moreover, the incidence and severity of such chronic health problems have been directly associated with the level of employee sickness absence (Gmel & Rehm, 2003; Jones et al., 1995). Additionally, because alcohol may have both immediate and longer-term adverse effects on mental function (i.e., pattern recognition, reasoning, detection of auditory and visual stimuli, ability to divide attention, time estimation, hazard perception, anticipation time, coordination and general reaction time), the risk of injury stemming from work and non-work accidents may be greater for those with higher levels of modal consumption (Moskowitz & Fiorentino, 2000). And to the extent that injuries such as those resulting from falls or motor vehicle accidents may be associated with long recovery periods, there may be a further basis for positing a link between modal alcohol consumption and sickness/injury-based workplace absence. Indeed, given that cognitive impairment occurs at blood alcohol content levels as low as 0.05 percent (the level reached by the average adult male within an hour of consuming two drinks), to the extent that individuals engage in even moderate levels of consumption on a more frequent basis, there may be an increase in the risk of such injury-based absence.

Despite the intuitive appeal of the argument above, as noted earlier, the empirical evidence regarding such a link between modal consumption and employee absence remains equivocal (Frone, 2008). Cross-study inconsistencies in the assessment of absenteeism may offer one explanation for these mixed findings. For example, most of the studies finding either a null or inverse relationship between alcohol consumption and workplace absenteeism (e.g., Ames, Grube & Moore, 1997; Blum et al., 1993; Foster & Vaughan, 2005; Stewart et al., 1993) have been based on retrospective, self-reports of absence behavior. As noted by Blum et al. (1993), denial tendencies on the part of problem drinkers might increase the likelihood that such individuals “deliberately distort their reports of job behaviors in an effort to normalize their apparent deviation from performance standards”, and as such, potentially account for the inverse or null relationships detected (p. 66). Moreover, Johns and Xie (1998) found that when given the opportunity to self-report absenteeism, employees tend to under-report their own absenteeism level, and show an attendance rate superior to that attributed to co-workers. Those in denial about a drinking problem might have an incentive to portray themselves even more superior than those lacking such a problem, particularly if they have received warnings about their absenteeism in the past.

Another possible explanation for the inconsistent findings may be that rather than having a monotonic relationship with absence, modal alcohol consumption may have a curvilinear , U-shaped association with absence. Such a relationship is reasonable considering that individuals abstaining from alcohol may do so due to medical conditions that may be associated with both higher rates of absenteeism and the need for abstinence (Blum et al., 1993; Vasse et al., 1998). To the extent that this is true, those reporting a moderate level of modal consumption may in fact manifest lower rates of absenteeism than those consuming no alcohol at all. Indeed, a number of studies (e.g., Marmot et al., 1993; Vahtera et al., 2000) find precisely such a relationship between modal alcohol consumption and employee absenteeism. Thus, the inconsistency in findings regarding the alcohol-absence relationship may stem from the tendency of many studies to assume linearity in what may in fact be a curvilinear relationship.

However, more likely is that modal consumption – for several reasons – fails to effectively capture the primary mechanisms linking drinking to work absence for most employees (Frone, 2008). First, because the health implications of heavier drinking only emerge gradually over time (Maxwell, 1960; Blum et al., 1993), for most workers the concurrent association between the level of modal consumption and health is likely to be limited. As a result, the physiological mechanism noted above may be inadequately captured when framing drinking strictly in terms of modal consumption. That is, while higher levels of modal consumption may result in the absence-related health consequences noted above, this is likely to be a highly time-dependent process manifesting itself only among those employees who have consistently consumed alcohol at high levels for an extended period of time (e.g., late-stage alcoholics). Supporting such an argument, Mangione, Howland, and Lee (1998) found that the majority of alcohol-related workplace problems such as absenteeism (60%) in their sample were attributable to the 80% of those workers who, while not abstaining from alcohol, also did not consistently consume large quantities. Moreover, any adverse impact of modal consumption on employee health may be attenuated by the health benefits said to be afforded by moderate consumption of alcohol (Poikolainen, 1994; Vahtera et al., 2000).

Second, modal consumption is likely to be a poor predictor of injury-based absence in that: (a) there is little evidence of a link between modal consumption and work-based injury (Webb et al., 1994; Frone, 2008), and (b) alcohol-based injuries can and often do occur among those individuals who, despite reporting moderate or low modal consumption, periodically engage in heavy (i.e., “binge”) drinking (Ames et al., 1997; Cherpitel, 1993). Indeed, precisely because how much one “normally” drinks may not necessarily be indicative of the amount consumed just prior to an absence event, this approach may offer a relatively poor basis for capturing either the heightened risk of injury posed by alcohol or the more general impairment dynamic suggested by McFarline and Fals-Stewart (2002) as being the key mechanism underlying the alcohol-absence relationship.

Capturing the Impairment Dynamic

In contrast, a focus on how alcohol is consumed, and in particular, the frequency with which an individual engages in episodes of heavy drinking, may more effectively capture this impairment dynamic. As an alcohol metric, episodic heavy drinking, defined as the consumption of five or more drinks on a single occasion (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2005), captures precisely that alcohol-related behavior that is most likely to generate pharmacological impairment. Moreover, research suggests that for most adults, the pharmacological effects of alcohol consumption at such levels often linger several hours after the actual drinking episode ends (Morrow, Leirer, & Yesavage, 1990). Accordingly, underlying a focus on the frequency with which employees engage in heavy drinking episodes is the assumption that it is how employees typically drink off the job, and in particular, the degree to which their typical pattern of consumption is characterized by more frequent episodes of heavy drinking, that is likely to have the strongest alcohol-related impact on employee absenteeism. That is, those reporting to engage in episodic heavy drinking more frequently are likely to report a greater number of lost days at work than those either not engaging in such activity at all, or engaging in such activity only rarely.

Aside from Ames et al.’s (1997) finding of a higher rate of absenteeism among workers reporting at least one episode in the past year in which they consumed 10 or more servings of alcohol, research has yet to empirically establish a link between the frequency of heavy drinking episodes and employee absence. Nevertheless, there is at least indirect evidence that impairment resulting from such episodes may serve as an important motivator of employee absence. First, impairment may be manifested in “hangover’ symptoms (e.g., headache, dehydration, tremor, dizziness, nausea and vomiting; Wiese, Shlipak & Browner, 2000) which, depending on the absence culture of the employing organization (Rentsch & Steel, 2003; Bamberger & Biron, 2007), may be viewed by the employee as a legitimate reason for missing work. Second, a number of studies indicate that alcohol impairment at work may increase the likelihood of interpersonal workplace problems such as conflicts with co-workers or supervisors (Ames, et al. 1997; Lehman and Simpson, 1992; McFarlin, Fals-Stewart, Major, & Justice, 2001; Moore et al., 2000). To the extent that employees recognize this association and are concerned that such problems may be cause for disciplinary action or even dismissal, individuals experiencing any of the shorter-term, pharmacological effects of heavy alcohol consumption may prefer to miss work rather than attend work and risk discipline (what Blum et al. [1993] refer to as “stay-away” absence). Third, studies have demonstrated a link between alcohol-impairment at work and the risk of job-related injury, particularly in safety-sensitive jobs (e.g., transport, punch-press operator, welding, assembly) in which cognitive or psychomotor impairment increases accident risk (Frone, 2004; 2008). Thus, as noted by Blum et al (1993), workers may utilize absence as a “precaution against on-the-job injury following periods of heavy drinking when they are more vulnerable to accidents” (p. 62). Finally, because for many employers, on-the-job intoxication or alcohol impairment is viewed as a gross violation of shop rules, impaired employees may prefer to miss work rather than taking the risk of being detected, disciplined or even dismissed (Blum et al., 1993). Accordingly, we posit:

Hypothesis 1a: The frequency of episodic heavy drinking is positively associated with the number of absence days.

Moreover, given the conceptual and methodological limitations associated with examining the alcohol-absenteeism relationship on the basis of modal alcohol consumption, we also posit that a metric capturing the way in which employees drink will explain more of the variance in employee absence than how much they typically drink, even when the latter is modeled as having a curvilinear relationship with absence. In other words:

Hypothesis 1b: The frequency of episodic heavy drinking is a more robust predictor of absence than modal alcohol consumption.

Hypothesis 1c: The frequency of heavy episodic drinking explains a significantly greater share of the variance in absence than modal alcohol consumption even when taking into account the possible curvilinear relationship of the latter with absence.

The Moderating Effect of the Relational Context at Work: Peer and Supervisor Support

Recent research regarding the determinants of employee absence emphasizes the likely role played by employee volition and the utility calculations underlying such choice (Harrison & Martocchio, 1998). Surprisingly, however, scholars examining the alcohol-absence relationship have made little attempt to integrate notions of expected utility (Fichman, 1984) into their models. To the extent that the alcohol-absence relationship is grounded on an illness or injury dynamic, the absence of such an element is more understandable in that in such cases, individual employee volition is likely to play little role in determining whether or not the individual attends work. Simply put, to the extent that the injuries and chronic illnesses often associated with alcohol are severe, sick or injured employees may be unable to attend work even if they wish to. However, to the extent that the alcohol-absence relationship is grounded on an impairment dynamic, individual employee volition is indeed likely to play a significant role in determining whether or not work is missed. While impairment may, in some cases, be severe enough to physically prevent the employee from attending work, in many cases, physical attendance is not prevented, thus leaving the employee with the need to make a decision as to whether or not to attend work.

Previous research suggests that a variety of workplace conditions are likely to influence the choices that impaired employees make when faced with such a decision (Ames et al., 2000; Martocchio & Harrison, 1993). More specifically, adopting a subjective expected utility perspective (Stevenson, Busemeyer & Naylor, 1990), Blum et al. (1993) suggest that workplace factors influencing the relative benefits and risks of absence versus attendance are likely to determine the motivation of employees to report to work despite a given level of alcohol impairment. According to the logic suggested by Blum et al. (1993), employees are likely to be more motivated to report to work despite experiencing some level of alcohol impairment to the extent that they believe that the likely costs of absenteeism outweigh the expected costs of attendance. Building on this logic, we propose that co-workers and supervisors, particularly with regard to the extent to which they offer support (i.e., exhibit understanding and provide useful ideas as to how to overcome challenges; House, 1981), are likely to play a key role in shaping such beliefs.

To the extent that employees view their co-workers as more supportive, we posit that, for two reasons, they are likely to downwardly estimate the costs of attending relative to those associated with being absent, resulting in an increased motivation to attend and the attenuation of the alcohol-absenteeism relationship. First, co-workers are typically deemed to be more supportive to the extent that they provide one another with emotional or instrumental forms of assistance (House, 1981). To the extent that co-worker support may provide a certain degree of relief from the work- or home-based stressors potentially underlying the individual’s drinking behavior (Frone, 1999), individuals may be motivated to attend work despite impairment or its associated sequellae (e.g., hangover) so as to be able to receive such assistance. Furthermore, to the extent that co-worker support is more instrumental in nature and, consistent with findings in the ethnographic literature (e.g., Sonnenstuhl, 1996), manifests itself in the form of recommendations as to how to avoid detection (or actual assistance in doing so), the subjective expected costs of attending work (i.e., detection and discipline) may be lessened. In sum, as long as they have more supportive co-workers, individuals reporting a modal pattern of alcohol consumption characterized by more frequent instances of heavy drinking may associate more benefits and fewer risks with regular work attendance. To the extent that this occurs, the generally positive association between alcohol consumption and absenteeism may be attenuated under conditions of increased perceived co-worker support.

Second, given that such social support is typically provided in the context of a broader framework of social exchange (Blau, 1964; Lawler & Yoon, 1996), a core tenant of which is the norm of reciprocity (Gouldner, 1960), individuals reporting more supportive co-workers may – compared to those reporting less supportive co-workers – view absenteeism as a form of behaviour inconsistent with the norm of reciprocity. To the degree that this is indeed the case, it would suggest that the generally positive association between the frequency of episodic heavy drinking and absenteeism may only be further attenuated as a function of co-worker social support. From a social exchange perspective, relations between two co-workers are the joint product of the actions of both parties, with the actions of each being dependent on those of the other (Blau, 1964). Thus supportive interactions generate a sense of commitment and obligation, with the understanding that, if party “A” is supportive of party “B”, party “B” should respond in kind. While previous research suggests that coworkers are likely to be adversely affected by an individual’s absence from work (Johns 1997), these adverse affects on coworkers are likely to be more salient to the individual and thus impose increased social costs on the individual to the extent that the individual feels more obligated and committed to these coworkers (Lawler & Yoon, 1996). Accordingly, recognizing the potential adverse impact of absenteeism on one’s co-workers (in the form of work overload, overtime demands, and/or the need for them to perform tasks for which they may not be adequately trained), individuals perceiving their co-workers as being more supportive may be less willing to impose these costs on their co-workers and attend work despite alcohol-related impairment. Such a notion is consistent with recent trends in absenteeism research suggesting that employee attendance behaviour is influenced by social control in general (Johns, 1997; 2008) and perceptions of equity and psychological contract breach in particular (Johns, 2001; 2008). Taking these two considerations into account, we posit that:

Hypothesis 2a: The generally positive association between the frequency of episodic heavy drinking and the number of days absent from work is attenuated as a function of the degree to which the individual deems his/her co-workers as supportive.

In contrast, to the extent that employees with more frequent/heavier patterns of alcohol consumption view their supervisors as more supportive, they may be likely to upwardly estimate the costs of attending work relative to those associated with being absent, resulting in a decreased motivation to attend and the amplification of the alcohol-absenteeism relationship. Underlying this logic is the assumption that to the degree that supervisors are viewed as more willing to listen to subordinate problems, talk subordinates through such problems, and use their knowledge to help employees comply with organizational policies and procedures when confronting such problems (i.e., are perceived as being more supportive), they may also be viewed as preferring facilitative engagement as an alternative to direct policy enforcement (Bacharach, Bamberger, & Sonnenstuhl., 2002). That is, supervisors viewed by their subordinates as being more supportive may also be assumed by these same subordinates to be less likely to turn to formal discipline as a preferred means by which to address workplace problems such as absenteeism. In this sense, supervisory support may diminish the expected costs of impairment-associated absence.

This lowering of the expected costs of impairment-related absence is unlikely to be counterbalanced by a reciprocity-based, sense of obligation to attend work on the part of the employee in that the supervisor (unlike a co-worker) is unlikely to be perceived as incurring any personal, pecuniary cost as a result of the individual’s absence. Thus, rather than experiencing a guilt-based obligation to reciprocate support by attending work, individuals may reciprocate supervisor support in an alternative manner, such as being more cooperative when on the job or doing favours for the supervisor either at work or away from it. Indeed, as noted by Blum et al. (1993), the workplace alcohol literature suggests that problem drinkers tend to receive similar or even higher supervisory ratings on cooperation, initiative, job knowledge and work quality than those who are not problem drinkers.

However, beyond diminishing the expected costs of impairment-associated absence, supervisory support may also increase the perceived expected costs of attendance. This is because more supportive supervisors may also be perceived as being more engaged, and hence more likely to notice any change in work behavior caused by impairment. Thus, even if the risk of discipline by such supervisors is perceived to be lower, impaired employees may view attendance as heightening the risk that their supervisor will detect and scrutinize their off-the job behavior, thus, at the very least, generating feelings of shame and/or embarrassment2. The upshot is that employees perceiving their supervisors as more supportive may be more likely to perceive the expected costs of absenteeism as being lower than those associated with presenteeism (i.e., being impaired at work; Hemp, 2004), leading us to propose:

Hypothesis 2b: The generally positive association between the frequency of episodic heavy drinking and the number of days absent from work is amplified as a function of the degree to which the individual deems his/her supervisor as supportive.

Method

Design and Sample

We designed the current study taking three main methodological concerns into account. First, given the limited generalizability of findings regarding the alcohol-absence relationship generated on the basis of clinical samples (e.g., individuals undergoing treatment for a drinking problem; Gmel & Rehn, 2003), we framed our study around a non-clinical working population. Second, recognizing that field studies based on the collection of anonymous, retrospective self-reports of both drinking behavior and missed days of work may be subject to percept-percept bias (Blum et al., 1993; McFarlin & Fals-Stewart, 2002), we relied on self-reports for drinking behaviour and drew our absence data from archival data in the context of a prospective design. The use of archival absence data eliminates the validity concerns associated with self-reported absence reported by others (Goldberg & Waldman, 2000; Johns & Xie, 1998). Moreover, while researchers have little choice but to rely on self-reports as a basis for assessing modal drinking behaviour in the past one to four weeks, there is consistent evidence supporting the validity of such reports (Lehman & Simpson, 1992; Gruenewald & Nephew, 1994; Gruenewald & Johnson, 2006). Additionally, as noted earlier, self-reported drinking behavior – both modal consumption and modal frequency of episodic heavy drinking – appear to remain stable over time among adults (Grant et al., 1995; Hasin et al. 1997; Kerr, Fillmore & Bsotrom, 2002) allowing alcohol researchers to assume that typical patterns reported over a recent past time frame are likely to be representative of drinking patterns in the near-term (Gruenewald & Johnson, 2006). Finally, we test our hypotheses on a sample drawn from a single organization in order to control for the possibility that cross-organizational norms regarding employee drinking and absence may be systematically linked (i.e., organizations characterized by permissive drinking norms may also tend to have more permissive absence norms).

Participants were identified through the membership files of a large local union representing all non-exempt workers employed by the transportation authority of a large municipality in the United States. This transportation authority is known to closely monitor employee attendance and enforce a strict absence policy requiring employees to submit medical certification for any absence other than an approved vacation or personal day, and to submit to an employer-sponsored medical examination for any absence spell longer than two days. Non-sickness absence that is neither a vacation nor an approved personal day is considered unexcused and is grounds for discipline up to and including dismissal.

A random sample of 1093 workers, stratified by operating division, was drawn from among those workers employed by the authority for at least 12 months. All were employed in one of the authority’s three main operating divisions, namely buses (e.g., bus drivers, mechanics), stations (e.g., station agents, cleaners) and underground/subway operations (e.g., conductors, train operators, track maintenance). While many of those in particular occupations work independently (e.g., bus drivers, train operators), even these individuals have extensive break time (at least 1 hour a day) which is typically spent with their co-workers at the depot, terminal or shop. The size of each division-specific target sample was determined on the basis of the proportionate size of each division. Sampled workers were requested to complete an 18-page questionnaire with confidentiality guaranteed by the union. Approximately one year later, absenteeism data for the 12-month period beginning with the survey administration were drawn from the authority’s personnel archives.

Working with the union, survey data were collected from 626 transit workers using a coding mechanism designed to ensure that no party would be able to physically link a name to a questionnaire. 37 observations were excluded from our analyses due to either suspect or excessive missing (e.g., 33% or more uncompleted items) data. An additional 47 observations were excluded from our analysis due to participants’ failure to provide data on the alcohol-related variables. Finally, data from another 72 survey participants had to be excluded because they either retired or went out on disability within the year following the survey, making it impossible to collect data on the dependent variable (i.e., absenteeism). Of the remaining 470 participants, 69% were males, 49% were married, the mean age was 45.7 years (STD= 8.2), and the mean tenure was 11.3 years (STD= 6.6). 42 percent were employed in the authority’s bus division, 49.5 percent in the station division, and 8.5 percent in the rapid transit (i.e., subway) division. Given the size of the overall target sample (1093), the effective response rate for the study as a whole was 43 percent.

In order to check for possible response bias, we compared the mean annual absence rate for study participants with union estimates of absenteeism for their membership as a whole for roughly the same period of time, finding no appreciable difference (10.9 vs. 10.7 days). Additionally, we found no significant differences between participants’ mean scores and those of the members of a separate random sample of members (n=186) of the same union local from whom drinking and support-related data had been collected five years earlier. Finally, the results of t test analyses comparing mean scores along all study variables indicated no significant differences between those dropped from the analyses and those remaining.

Measures

Drinking Measures

To assess the modal level of alcohol consumption, we adopted the approach of Blum et al. (1993), calculating the product of responses to two consumption items, namely: (1) On how many days in the last month they consumed an alcoholic beverage such as beer, wine or liquor (i.e., frequency of alcohol consumption), (2) On those occasions when they did drink alcoholic beverages in the last month, the average number of drinks they consumed each time (i.e., average quantity of consumption). The distribution on this variable was highly skewed (Skewness = 13.75; S.E = 0.12). Such a high skewness makes it illogical to assume that unit increases in low versus high modal consumption values will give rise to the same change in absenteeism. Consequently, consistent with prior research (e.g., Mangione et al., 1999), in the multivariate analyses reported herein this variable was transformed using log to the base “e” by first adding “1” to the average amount consumed. Frequency of episodic heavy drinking was calculated on the basis of the SAMHSA (1995) metric noted earlier, namely by asking participants on how many days in the past month they consumed five or more drinks.

Absenteeism

Absence data were provided by the employer. With non-sickness absence (other than in the context of an approved vacation or personal day) subject to discipline, the employer considered and recorded all missed days other than approved vacation and personal days as absence events. Accordingly, like the employer, we operationalized absence in terms of the number of workdays recorded by the transit authority in the employee’s personnel record as having been lost for any reason other than an approved vacation in the 12-month period following the administration of the survey. The mean number of days absent for those in the sample was 10.9 (SD=11.54). Absence data were highly skewed to the right (Skewness = 4.4 (S.E = .096); Kurtosis = 27.26 (S.E = .191)) and a Kolomogorov-Smirnov test confirmed that they were not normally distributed (KS = 5.661, P<0.01). As we describe in detail below (see ‘Analysis Technique’), such data require the use of non-linear modeling strategies (e.g., Bamberger & Biron, 2007; Hammer & Landau, 1981).

Social Support

We used an 8-item index adopted from Anderson and Williams (1996) to assess perceived social support. With respect to peer support, participants were asked to think about “the two individuals to whom you feel closest at work; that is, those co-workers – peers with whom you work – to whom you feel most comfortable turning for support and advice and whose opinion you really value”. For each of these co-workers, participants were asked to indicate how often during the past month each one provided them with such support as “Talked you through work-related problems, helping you come up with solutions”, “Provided you with encouragement (positive feedback) about your work” and “Offered to assist you with work when you where having a stressful shift”. Participants responded using a 5-point scale ranging from (0) “never”, to (4) “Several times a day”. The level of inter-member agreement (rWG) was calculated for each referent dyad on the support variable, denoting the degree to which ratings of the two referents of each individual were interchangeable (Bliese, 2000). Across the 470 referent dyads, the mean rWG was 0.77, which is considered high enough to justify aggregation. Accordingly, we calculated the mean support score for each referent other and then took the average of these two mean scores as our indicator of peer support. We used the same social support index to measure supervisor support, with supervisor support operationalized as the mean score along these same 8 items with respect to the individual’s immediate (i.e., direct) supervisor.

A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to assess the discriminant validity of these two support measures (i.e., peer and supervisor support). Accordingly, a single-factor model was compared to the assumed 2-factor model. The results indicate that the two-factor solution provided a significantly better fit to the data than the one-factor solution (χ2= 383.2, p<0.01; CFI= 0.95, GFI= 0.93, RMSR= 0.04; and χ2= 597.3, CFI= 0.67, GFI= 0.73, RMSR= 0.12, respectively; Δχ2= 214.1, p<0.001). Because each of these factors might contain two sub-factors – one relating to more instrumental or tangible support, and the other to more emotional or intangible support (See Table 1 for descriptive statistics on these two sub-factors), a second set of confirmatory factor analyses (one for peer support and the other for supervisory support) were conducted. In both cases, the two factor solution was not significantly better than one-factor solution (Δχ2df=1 = 1.19, p>.10 and Δχ2df=1 = 0.16, p>.10 for peer and supervisory support, respectively). Consequently, we retained two support measures for our analyses, namely peer and supervisor support (Cronbach coefficient alpha = 0.94 and 0.92, respectively).

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations and Intercorrelation (Pearson) of the Measured Variables (N=421)

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gender (1=male; 2=female) | 1.3 | .44 | --- | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Age | 45.5 | 7.8 | .00 | --- | |||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Marital Status (1=Married, 0=else) | .52 | .50 | −.18** | .07 | --- | ||||||||||||||||

| 4 | Tenure | 11.3 | 6.3 | .07 | .47** | .02 | --- | |||||||||||||||

| 5 | Average work hours/week | 45.6 | 10.2 | −.08 | −.01 | .03 | .01 | --- | ||||||||||||||

| 6 | Household Income | 4.2 | 2.2 | −.10* | .01 | .35** | .16** | .09 | --- | |||||||||||||

| 7 | Disciplinary Grievances | .22 | .81 | −.06 | −.02 | .06 | .10* | .00 | .09 | --- | ||||||||||||

| 8 | Depression | 1.3 | .55 | .03 | −.07 | −.08 | .05 | −.05 | −.09 | −.05 | --- | |||||||||||

| 9 | Division 1 | .09 | .29 | −.32* | −.13* | .13** | −.28** | .26** | .11* | .02 | −.04 | --- | ||||||||||

| 10 | Division 2 | .44 | .50 | −.07 | −.06* | .01 | .25** | −.06 | .17** | .00 | .00 | −.29** | --- | |||||||||

| 11 | Division 3 | .46 | .50 | .36** | .10 | −.13** | .14** | −.22** | −.22** | .06 | .04 | −.83** | −.29** | --- | ||||||||

| 12 | Modal Alcohol Consumption (Log) | .87 | 1.3 | −.16** | .04 | −.04 | .08 | .01 | −.01 | −.07 | .04 | −.02 | .04 | −.00 | --- | |||||||

| 13 | Frequency Heavy Drinking | .34 | 1.1 | .03 | .14** | .04 | .05 | .02 | .01 | −.05 | −.02 | −.03 | −.08 | .07 | .47** | --- | ||||||

| 14 | Peer Support | 1.3 | 1.0 | −.01 | −.16** | .01 | .02 | .05 | −.01 | −.02 | −.24** | .01 | .05 | −.02 | .06 | −.02 | --- | |||||

| 15 | Peer Support - Tangible | 1.3 | 1.1 | .03 | −.08 | .00 | −.03 | .04 | .06 | −.04 | −.16** | .04 | .02 | −.00 | .09 | .00 | .65** | --- | ||||

| 16 | Peer Support - Intangible | 1.2 | 1.0 | .01 | −.06 | −.05 | −.07 | .03 | .00 | −.02 | −.20** | .02 | .07 | −.05 | .06 | .03 | .69** | .55** | --- | |||

| 17 | Supervisior Support | .97 | .78 | .02 | −.01 | .06 | .13** | −.01 | −.00 | .02 | .02 | −.18** | .12* | .10* | −.07 | −.05 | .37** | .38** | .33** | --- | ||

| 18 | Supervisor Support - Tangible | 1.0 | .81 | .02 | −.09 | −.01 | .10 | −.03 | .03 | .02 | −.04 | −.08 | .10* | .05 | −.04 | −.06 | .34** | .39** | .30** | .64** | --- | |

| 19 | Supervisor Support - Intangible | .95 | .75 | .01 | −.05 | −.03 | .07 | −.05 | −.01 | .06 | −.08 | −.11* | .14* | .09 | −.08 | −.09 | .39** | .31** | .34** | .70** | .61** | --- |

| 20 | Absenteeism | 9.55 | 6.95 | .05 | .04 | −.05 | .08 | .12* | −.01 | .06 | .05 | .07 | −.11* | −.00 | .13* | .24** | −.06 | −.06 | −.07 | −.11* | −.12* | −.14* |

p<.05

p<.01

Control Variables

In order to rule out any spurious relations, we controlled for gender, age, marital status, tenure, household income (a proxy for socio-economic status; operationalized in terms of 8 equal-sized categories from $35K-$45K to $105K-$115K), and average hours worked per week. These variables have all been identified as related to both drinking (e.g., Mangione et al., 1999, Webb et al., 1994) and absenteeism (Farrell & Stamm, 1988; Price, 1995). We also controlled for depression in order to rule out the possible comorbidity effects. To do so, we used the 7-item depression subscale of the DASS-21 instrument (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995), which has been validated in a number of studies (e.g., Antony, Bieling, Cox, Enns, & Swinson, 1998; Crawford & Henry, 2003). Cronbach’s coefficient alpha for the depression scale was 0.93. Furthermore, because social deviance may also serve as a comorbidity factor (Blum et al., 1993), we also controlled for the number of discipline charges filed against the employee by the employer during the prior 12 months (as a rough indicator of such deviance). Finally, because the safety-sensitivity of a job may affect the motivation of an employee to avoid coming to work impaired, we controlled for the safety sensitivity of jobs by taking into account the division in which the individual was employed. Two dummy variables represented the three divisions (with ‘stations’ – the division whose employees were in the least safety-sensitive positions – serving as the reference group).

Analysis Technique

With absenteeism typically modelled as a count variable, there is a need to properly account for its typically non-normal distribution. Although the single-parameter Poisson distribution is widely applied in such cases, it is often criticized for its restrictive assumption of equality between the variance and the mean, as well as its tendency to generate too many false positives (Sturman, 1999). Accordingly, in addition to the Poisson model, we also considered two alternative extensions of this model based on the work of Cameron and Trivedi (1986). The first is the standard Negative Binomial model, and the second – a form of the Negative Binomial model but with a variance function linear to the mean – is the over-dispersed Poisson model.

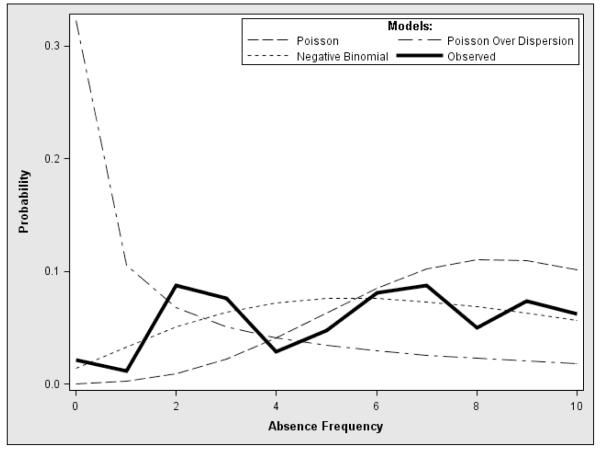

We evaluated the goodness of fit of each of these three models by comparing the observed and predicted probabilities based on the probability distribution of the model at hand. WenSui and Cela (2008) proposed this method as an alternative to the more popular approach in which the goodness of fit of a regression for count data is evaluated by comparing the predicted and observed values of the dependent variable. Accordingly, we applied the SAS/ETS Countreg Procedure and PROBCOUNTS macro (available at http://support.sas.com) to produce the average predicted count probability from Poisson, Negative Binomial and Over-dispersed Poisson Regressions. We than compared these average predicted count probabilities to the observed probability values. Figure 1 presents the comparison between the average predicted count probabilities of the three possible models and the observed probabilities. As the figure clearly demonstrates, the probability based on a Negative Binomial model best fits the observed probabilities. Accordingly, we tested our hypotheses on the basis of a negative binomial model.

Figure 1.

Comparison between Observed and Average Predicted Count Probability from Poisson, Negative Binomial and Over-dispersed Poisson Regressions.

Results

Means, standard deviations and correlations among the variables are displayed in Table 1. In order to ensure consistency between the bivariate and multivariate analyses, the statistics reported in this table are based on the list-wise deletion of observations with missing data on any of the control variables. T test analyses comparing the drinking behavior and absence of those dropped from the analyses (n=49) and those remaining (n=421) indicate no significant differences between the two groups (p>0.10). The bivariate results indicate a positive relationship between absenteeism and both drinking measures i.e., log of modal consumption (r=.13, p<0.01) and frequency of episodic heavy drinking (r=.24, p<0.01), with both drinking measures being, not surprisingly correlated (r=.47). It is also interesting to note the significant inverse correlation between supervisory support and days absent (r=−.11, p<.05).

The results of our multivariate analyses testing Hypotheses 1a, 1b, and 1c (which specified that the frequency of episodic heavy drinking: (a) is positively associated with the number of absence days, (b) is a more robust predictor of absence than modal consumption, and (c) explains a greater share of the variance in absence than modal alcohol consumption even when taking into account the possible curvilinear relationship of the latter with absence) are presented in Models 2-5 of Table 2. Although neither of the two modal consumption parameter estimates specified in Model 2 were statistically significant, it is notable that this model still explained 2 percent more variance than the control model and that the contrast analysis indicated that this difference is statistically significant (χ2df=2 = 9.39, p<.01). The lack of significant parameter estimates for the two modal consumption variables likely stems from the high correlation between the log of modal consumption and its squared term (r=0.92). Consequently, we ran an additional analysis specifying a linear effect only. In this model (Model 3), the log of modal alcohol consumption had a significant, positive effect on absenteeism (B=0.07, p<.01). Moreover, a contrast analysis indicates that the addition of a curvilinear effect for modal consumption fails to significantly add to the predictive utility of the model (χ2df=1 = 1.26, n.s.).

Table 2.

Negative Binomial Analyses Testing the Influence of Modal Alcohol Consumption and the Frequency of Episodic Heavy Drinking on Absenteeism, and the Moderating Effects of Peer & Supervisor Support (N=421)

| Model Variable |

(1) Control Model | (2) Main Effect Model- Curvilinear Modal Consumption |

(3) Main Effect Model- Linear Modal Consumption |

(4) Main Effect Model- Curvilinear Modal Consumption + Heavy Drinking |

(5) Main Effect Model- Linear Modal Consumption + Heavy Drinking |

(6) Moderation (Full) Model |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | S.E | B | S.E | B | S.E | B | S.E | B | S.E | B | S.E | |

| Gender (1= male; 2= female) | −.08 | .08 | −.13 | .08 | −.13 | .08 | −.13 | .08 | −.13 | .08 | −.13 | .08 |

| Age | .00 | .00 | −.00 | .00 | −.00 | .00 | −.00 | .00 | −.00 | .00 | −.01 | .00 |

| Marital status (1= married; 0= else) | .06 | .07 | .06 | .07 | .06 | .07 | .06 | .07 | .06 | .07 | .05 | .07 |

| Tenure | .02* | .00 | .01* | .00 | .01* | .00 | .02* | .01 | .02* | .01 | .02** | .01 |

| Average work hours per week | .01 | .00 | .01 | .00 | .01 | .00 | .01 | .00 | .01 | .00 | .01 | .00 |

| Household Income | −.00 | .01 | −.00 | .01 | −.00 | .01 | −.00 | .01 | −.00 | .01 | −.01 | .02 |

| Disciplinary Grievances | .03 | .04 | .04 | .04 | .04 | .04 | .04 | .04 | .04 | .04 | .04 | .04 |

| Depression | .07 | .06 | .07 | .06 | .07 | .06 | .07 | .06 | .07 | .06 | .06 | .06 |

| Division 1 | .10 | .08 | .14 | .08 | .14 | .08 | .14 | .08 | .14 | .08 | .13 | .08 |

| Division 2 | −.31* | .13 | −.30* | .12 | −.30* | .12 | −.25* | .12 | −.25* | .12 | −.20 | .12 |

| Alcohol Consumption | −.00 | .07 | .07** | .03 | −.03 | .07 | .02 | .03 | −.10 | .07 | ||

| Alcohol Consumption squared | .02 | .02 | --- | --- | .01 | .02 | --- | --- | .04 | .02 | ||

| Frequency of heavy drinking | .11** | .04 | .12** | .04 | .13** | .04 | ||||||

| Peer support | −.04 | .03 | ||||||||||

| Supervisor support | −.05 | .05 | ||||||||||

| Heavy drinking X Peer support | −.08** | .03 | ||||||||||

| Heavy drinking X Supervisor support |

.22** | .07 | ||||||||||

| Model Summary |

◆R2 =.05 Full Log Likelihood= −1320.91 |

◆R2=.07 Full Log Likelihood= −1316.22 ΔR2 =.02** (Relative to Model 1) |

◆R2=.07 Full Log Likelihood= −1316.84 ΔR2 =.02** (Relative to Model 1) |

◆R2 =.010 Full Log Likelihood= −1310.77; ΔR2=.03** (Relative to Model 2) |

◆R2 =.010 Full Log Likelihood= −1311.02; ΔR2=.03** (Relative to Model 3) |

◆R2 =.14 Full Log Likelihood= −1301.18; ΔR2 =.04** (Relative to Model 4) |

||||||

p<0.05

p<0.01

Cox and Snell’s (1989) generalized R2.

We nevertheless tested Hypotheses 1a-c on the basis of the more conservative specification including a curvilinear effect for modal consumption. The results of these tests (displayed in Model 4) indicate that, as proposed in Hypothesis 1a, the frequency of episodic heavy drinking is positively associated with the number of absence days (B=.11, p<.01). Additionally, as proposed in Hypothesis 1b, even when contrasted against a strictly linear effect of modal consumption (Model 5), the effect of heavy drinking is of a larger magnitude (B=.12, p<.01) than that of the log of modal consumption (B=.02, n.s.). Finally, consistent with Hypothesis 1c, the model including the frequency of heavy drinking (Model 4) explains a significantly greater share of the variance in absence days (R2= .10) than that explained by modal consumption alone (Model 2 -- R2= .07) (ΔR2=.03, χ2df=1 = 10.21, p<0.01). Consequently, Hypotheses 1a - 1c were fully supported.

In order to test Hypotheses 2a (positing that the positive association between episodic heavy drinking and the number of days absent would be attenuated as a function of peer support) and 2b (positing that the positive association between episodic heavy drinking and the number of days absent would be amplified as a function of supervisor support), we first centered the two interaction terms, namely the three alcohol measures and two support measures (Aiken & West, 1991). These interactions terms were then incorporated into the full model. As shown in Model 6 of Table 2, the generally positive association between episodic heavy drinking and the number of days absent was found to be attenuated as a function of peer support (B for the interaction= −.08, p<0.01) and amplified as a function of supervisor support (B for the interaction= .22, p<0.01). The inclusion of the interaction terms resulted in a further increase in the total effect size relative to Model 4 (ΔR2= .04, χ2df=4 = 18.72, p<0.01). An expansion of this same model to include the interaction of peer and supervisor support with the centered log of modal alcohol consumption failed to explain a significantly greater degree of variance in absenteeism, and neither of the modal consumption interaction terms was significant.

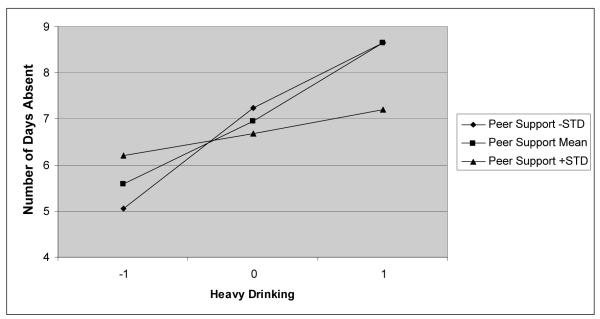

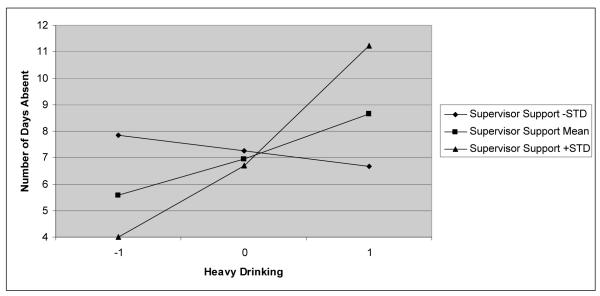

To further examine the effect of peer and supervisor support on the link between the frequency of heavy episodic drinking and absenteeism, we graphically illustrated the interaction utilizing a procedure similar to the one recommended by Stone and Hollenbeck (1989). Specifically, we plotted three slopes of each of the two moderating variables (i.e., peer support, supervisory support): one at one standard deviation below the mean, one at the mean, and one at one standard deviation above the mean. The slopes presented in these graphs are not necessarily linear in that the regression model upon which they are based assume the log of the expected value of absenteeism.

As Figure 2 illustrates, while under conditions of low and average levels of peer support there is the expected positive association between heavy drinking and the number of days absent, under conditions of high peer support, the link between heavy drinking and absenteeism is largely invariant. In addition, as Figure 3 illustrates, while the highest level of absenteeism was obtained under conditions of a high level of heavy drinking and a high level of supervisor support, the generally positive association of heavy drinking and the number of days absent is attenuated and, indeed, reversed as a function of low levels of supervisor support.

Figure 2.

The association between Heavy Drinking and Absenteeism as a Function of Peer Support: Curves for 3 Different Levels of the Moderator (−1 STD, mean, and +1 STD of peer support).

Figure 3.

The association between Heavy Drinking and Absenteeism as a Function of Supervisor Support: Curves for 3 Different Levels of the Moderator (−1 STD, mean, and +1 STD of supervisor support).

Simple slopes analyses were conducted on the heavy drinking-absence relationship under 9 different conditions determined by the combination of varying levels of peer support and supervisory support (each at −1 SD below the mean, mean, and +1 SD above the mean). Consistent with our hypothesis, the effect of heavy drinking on absence is positive and significant under conditions of high (+1SD) supervisory support, regardless of the level of peer support (estimates of 0.23, 0.32 and 0.40, respectively for high, mean and low levels of peer support, all at a significance level of p<0.01). The effect of heavy drinking on absence is also significant at mean levels of supervisory support when the level of peer support is at and below mean levels (estimates of 0.13 and 0.22 respectively for mean and low levels of peer support, both at a significance level of p<0.01). However, consistent with our hypotheses, assuming a mean level of supervisory support for those perceiving a high level of peer support (+1SD), the effect of heavy drinking on absence (estimate = 0.03) is not statistically significant. Moreover, assuming a low level of supervisory support (− 1 S.D.), for those perceiving a high level of peer support (+1SD), the effect of heavy drinking on absence is negative (estimate = −.14), although not statistically significant (p=.08). Consequently, Hypotheses 2a and 2b were also supported.

Discussion and Implications

The findings reported above suggest that modal consumption has a positive, linear association with employee absence, but only when the frequency of episodic heavy drinking is left unspecified in the model. When the latter is included in the model, the effect of modal consumption on absence is no longer significant. In contrast, even when controlling for modal consumption, the effect of the frequency of episodic heavy drinking on employee absence is significant. Moreover, our results suggest that the perceived degree of support – and in particular, the degree to which employees perceive their co-workers and supervisors as more supportive – can play an important role in determining the extent to which such risky drinking behavior is associated with increased rates of absenteeism. More specifically, our findings indicate that the effect of heavy drinking on absence is attenuated under conditions of greater co-worker support and strengthened under conditions of greater supervisor support.

The first set of findings regarding the main effects of modal consumption versus episodic heavy drinking on employee absence are of significant theoretical importance in that they suggest that the primary mechanism underlying any linkage between employee drinking behavior and absenteeism is the way alcohol is consumed rather than how much alcohol is consumed on average. More specifically, by testing models that included variables capturing both dynamics, our results provide some of the first evidence that, as suggested by others (e.g., McFarlin & Fals-Stewart, 2002; Frone, 2008), it is likely to be the short-term or acute impairment associated with heavy drinking episodes (rather than the more widely studied chronic-health mechanism associated with modal consumption) that explains the alcohol-absenteeism relationship. Indeed, the fact that the frequency of episodic heavy drinking was a significant predictor of subsequent employee absence even when controlling for modal consumption suggests that these effects cannot be simply explained by the adverse health-related effects of frequently drinking larger quantities of alcohol. The fact that our analyses took into account both the possible curvilinear effects of modal consumption on absenteeism as well as the possible conditioning role of peer and supervisor support on this relationship allows us to rule out the possibility that the more robust findings for episodic heavy drinking are a function of simple specification error. Indeed, as noted above, our findings suggest that to the extent that modal alcohol consumption is associated with absenteeism, the effects are linear.

Our findings also indicate that to the extent that modal alcohol consumption has been found to be associated with employee absence, this may be because this metric is highly correlated with the frequency of heavy drinking and thus captures some of the variance in how employees drink. Indeed, as our results indicate, controlling for the frequency of heavy drinking, modal alcohol consumption is no longer associated with employee absence. This lack of support for a main effect of modal consumption on absence is consistent with theory suggesting that employees’ engagement in light drinking on a regular basis, or infrequent heavy consumption may be so contained and/or temporally distal from the workplace so as to generate no apparent absence-related effect (Frone, 2008).

For a number of reasons, these main effect findings are also of empirical significance. First, they indicate that, at least in the organization studied, drinking behaviour in general, and episodic heavy drinking in particular, explains a relatively large proportion of the variance in employee absenteeism (i.e., 5 percent of the variance beyond that explained by the control variables). While this effect may be greater than that typically reported in studies using clinical samples, we believe that any difference in effect sizes likely stems from the underestimation of the relationship when estimated on the basis of clinical samples. Several researchers suggest that to the extent that archival medical excuses (often offering a psychiatric rather than alcohol diagnosis for individuals with a recognized alcohol use disorder) serve as the basis for estimating the prevalence of alcohol-related absenteeism in such studies, prevalence rates tend to be substantially underestimated (Saad & Madden, 1976; Hore, 1981. Marmot et al., 1993; Österberg, 2006). Furthermore, while non-clinical studies may over-estimate prevalence of alcohol-related absenteeism, for the reasons noted earlier, we do not believe that this was the case in the current study given the methodological precautions undertaken such as the use of a sample drawn from a single organization operating under a single collective bargaining agreement, the reliance on objective absence data retrieved from employer personnel records, a prospective study design, and the estimation of effects on the basis of a negative binomial model. Second, our findings are of empirical import in that they bolster Frone’s (2008) argument that how researchers operationalize employee drinking can directly influence findings regarding the impact of such behavior on work-related outcomes. And to the extent that significant resources are often allocated on the basis of such findings, a greater understanding of which alcohol-related behaviors are more tightly linked to absence may help managers and policy-makers better target expenditures aimed at employee absence-control.

Turning to the conditioning effects of social support, consistent with our hypotheses, we found that support received from different sources – i.e., co-workers or supervisors – may have different influences on the association between heavy drinking and absenteeism. The fact that the drinking-absenteeism relationship was attenuated as a function of co-worker support is consistent with the notion that employees value the peer-based advice, positive feedback and assistance that they receive by attending work. Such peer-based benefits may raise the expected utility of attending work relative to the utility associated with being absent (Harrison & Martocchio, 1998). Employees may also use this support as a means by which to lower the risks of employment termination. To the degree that peers are perceived as providing support in the form of cover-up, individuals may view the odds of termination due to absence as being higher than the risk of termination due to at-work impairment or alcohol-related presenteeism. The attenuating effect of peer support on the drinking-absenteeism relationship may also stem from a sense of obligation to peers from whom caring or sympathetic treatment is received. From a social exchange perspective (Blau, 1964), employees may seek to reciprocate such positive treatment by attending work, so as to avoid inflicting the potential adverse costs of their absenteeism on these peers. The significant attenuating effect of peer support on the heavy drinking-absenteeism relationship suggests that such supportive peer relations should be encouraged, particularly if employers can build upon such relations by training peers to identify possible alcohol problems among their coworkers and encourage such co-workers to seek help (Bacharach, Bamberger, & Sonnenstuhl, 1994).

In contrast to the attenuating effect of peer support on the link between heavy drinking and absenteeism, the effect of heavy drinking on absenteeism was strengthened as a function of supervisory support. In fact, the results of the simple slope analyses indicate that supervisor support has a predominant effect on the association between heavy drinking and absenteeism. Specifically, regardless of the level of peer support, higher levels of supervisory support amplified the association between heavy drinking frequency and employee absence. While, consistent with the literature (e.g., Goff, Mount, & Jamison, 1990; Eisenberger, Fasalo & Davis-LaMastro, 1990), the significant inverse correlation between perceived supervisory support and absenteeism noted earlier suggests a generally beneficial effect of supervisor support on employee absenteeism, these findings suggest that – in the case of employees who more frequently engage in heavy drinking – supervisory support may be a double-edged sword, having a net mixed or even reversed effect. This finding makes intuitive sense in that supervisors offering assistance to employees having a stressful shift or talking employees through a workplace problem (i.e., those perceived as more supportive) – particularly to the extent that these strains or problems themselves stem from a pattern of heavy drinking – may also be deemed as being more understanding and tolerant of alcohol-related absenteeism.

To this extent, employees that more heavily consume alcohol may take advantage of such supervisory support to pursue self-interested behaviors, such as absenteeism, assuming that their supportive supervisor will tolerate such behaviors (Bacharach et al., 2002). Moreover, in order to maintain balanced exchange relationships, employees may use strategies other than presenteeism to reciprocate supervisory support. Indeed, greater cooperation and initiative when attending work (Blum et al., 1993) may be deemed more meaningful reciprocation to their direct supervisor than simply attending work, since supervisors may not necessarily have to personally pay the price for their subordinates’ absence.

Accordingly, our findings suggest that employers should be cautious in encouraging their supervisory staff to exercise “across the board” support. Particularly for employees exhibiting problematic patterns of alcohol consumption, such support may be wrongly interpreted as a sign of supervisory ‘softness’ or forgiveness, leading to increased rates of absenteeism. To the degree that perceived supervisory support amplifies the impact of heavy drinking on absenteeism, employers may wish to reinforce to line managers the importance of monitoring employee absence and enforcing organizational absence policies, at least among those known to chronically abuse such policies. Employers may also wish to train their front-line supervisors in constructive confrontation (Sonnenstuhl & Trice, 1990) as a means by which to confront chronic absenteeism problems and encourage employees whose absenteeism is likely alcohol-based, to seek help.

Taken together, the interaction effects found in our study suggest that employee volition may play a far more significant role in the alcohol-absence relationship than previously thought. Moreover, despite the fact that alcohol-related absence is the result of behavior occurring outside of the workplace, they suggest that supervisory and peer-relations at work may still play an important role in shaping the outcome of work attendance decisions driven by alcohol-related impairment. From a practical perspective, the importance of such a finding cannot be understated in that, the literature suggests that managers typically have limited options in seeking to control alcohol-related absence (Sonnenstuhl & Trice, 1990; Blum et al., 1993). To the extent that managers are able to shape relational dynamics at work and thus influence employee perceptions of the expected benefits of absence to themselves as well as the impact that their absence is likely to have on supportive peers, our findings suggest that they may have a useful means by which to begin to address problems of alcohol-based absenteeism.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

The findings of our study should be considered in light of its limitations, some of which may also offer research opportunities. One such limitation stems from our inability to effectively examine whether these alternative operationalizations of drinking have the expected effects on the number of absence spells of varying duration (as opposed to the total number of days missed). More specifically, if acute impairment underlies the link between the frequency of heavy episodic drinking and absence while chronic illness underlies the link between modal consumption of alcohol and absence, we should observe a link between the frequency of episodic heavy drinking and the frequency of short (i.e., one- or two-day) but not long (i.e., 5+ day) absence spells, and between modal consumption and the frequency of long, but not short, absence spells. Using study participants’ absence spell data for the two months concurrent with the survey (the only spell data available to us), we conducted a post-hoc test for both of these propositions by running a series of negative binomial regression analyses paralleling those reported above but in which the dependent variable was the number of short/long absence spells in the 2 months concurrent with the survey (as opposed to the number of days absent in the 12 month period subsequent to it). While the results for both drinking variables were in the expected, positive direction, none of the effects even approached statistical significance. This is not surprising given the limited number of absence spells that can be observed in a two-month period. Consequently, in order to further enhance the understanding of the alcohol-absence relationship, we believe that an important next step in the research will involve the competitive testing of alternative operationalizations of drinking as predictors of the frequency of short and long absence spells over a more extended period of time.

A second limitation stems from the lack of anonymity in our data collection (necessary in order to link data regarding alcohol behavior with objective absentee data). The lack of participant anonymity may have encouraged more socially desirable responses and thus downwardly biased estimates of drinking and drinking problems (i.e., heavy drinking). In order to take this possibility into account, we re-ran the models reported above including a control for self-enhancement bias (namely, Paulhus’ [1991] BIDR measure) finding that the inclusion of this variable had no meaningful effect on the observed relationships.

Unfortunately, however, we were unable to control for the possible confounding effects of two other variables, namely smoking and coworker drinking. In terms of the former, studies suggest that because cigarette and alcohol consumption are correlated (King & Epstein, 2005, smoking may confound the alcohol-absence relationship (Ault, Ekelund, Jackson, Saba, & Saurman, 1991). Additionally, it is possible that the observed interaction effects may be different in models in which smoking is specified as a control variable. Consequently, we suggest that any future research exploring the alcohol-absence relationship take smoking into account.

Similarly, we suggest that future research also consider the degree to which heavy drinking episodes typically involve the individual’s coworkers since the attenuation effect attributed to peer support may be inflated to the extent that individuals tend to engage in such activity with these work-based peers. To the extent that they do, impaired employees may be even more motivated to attend work in order not to be seen as taking advantage of (i.e., “free-riding” on) those with whom they regularly engage in heavy drinking and who nevertheless report to work and are forced to cover for them.

Third, although over 600 employees participated in our survey and despite a response rate of nearly 60 percent, close to third of the observations (205) could not be included in our analyses due to missing data or other sample-related (e.g., drop-outs due to retirement, disability) problems. While the t test analyses mentioned earlier suggest that the responses of those excluded from the analysis were no different from those retained along all study variables, the risk of sample bias remains. In order to better assess the possible impact of this attrition on the results generated by our analyses, we applied a procedure recommended by Goodman and Blum (1996). Specifically, using logistic regression, we tested a model in which the dependent variable was a dichotomous variable distinguishing between observations used in our analyses (i.e., ‘stayers’) and those dropped for any reason (‘leavers’). The independent variables specified included all of the variables – predictor or criterion – of theoretical interest to us. With none of the coefficients emerging statistically significant, we are reasonably confident that any attrition was random and hence unlikely to have biased our results (Little & Rubin, 1987). Indeed, to the extent that those drinking more heavily may have had a greater interest in not completing the alcohol items than those abstaining or drinking more moderately, this would only serve to strengthen the conclusions drawn from our findings. More specifically, any such attenuation of the variance in drinking would serve to only reduce the likelihood of finding a significant alcohol-absence relationship, thus suggesting that, if anything, our findings err on the conservative.

Finally, although the evidence presented above is consistent with the argument that it is impairment that underlies the tendency of those more frequently engaging in episodic heavy drinking to miss more days of work, we are unable to conclusively demonstrate impairment is to blame. Indeed, previous studies (e.g., Blum et al., 1993) suggest that there are likely to be deviant clusters of “problematic behavior” (e.g., peer bullying, theft of company property), and that as such, it may not be the episodic heavy drinking itself that causes absenteeism, but rather the other problematic behaviors often co-occurring with episodic heavy drinking (e.g., aggressiveness, impaired driving) and the outcomes often associated with them (e.g., legal or financial problems). Although we attempted to control for such a confound by including in our specification a dummy variable for discipline, this metric only captures those “problematic behaviors” occurring in the workplace. Consequently, here too additional research is needed in order to clearly demonstrate the role of impairment as the link between drinking and absence, and to rule out the possibility that episodic heavy drinking may just be serving as a proxy for other non-work problematic behaviors that may be the real culprit behind employee absenteeism.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Terry Blum, Michael Frone, Gary Johns and two anonymous reviewers for their comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. The authors also thank Etti Doveh, Mickey Horowitz, Claudia Preparata and Edward Watt for all of their assistance.

Footnotes

All authors contributed equally and names appear in alphabetical order.

We are grateful to an anonymous reviewer for bringing this argument to our attention.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/journals/apl

Contributor Information

Samuel B. Bacharach, Smithers Institute, School of Industrial and Labor Relations, Cornell University

Peter Bamberger, Smithers Institute, School of Industrial and Labor Relations, Cornell University Faculty of Industrial Engineering & Management, Technion: Israel Institute of Technology.

Michal Biron, Graduate School of Management, Haifa University.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ames GM, Grube JW, Moore RS. The relationship of drinking and hangovers to workplace problems: An empirical study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:37–47. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames GM, Grube JW, Moore RS. Social control and workplace drinking norms: A comparison of two organizational cultures. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:203–219. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SE, Williams LJ. Interpersonal, job, and individual factors related to helping processes at work. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1996;81:282–296. [Google Scholar]

- Antony MM, Bieling PJ, Cox BJ, Enns MW, Swinson RP. Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10:176–181. [Google Scholar]

- Ault R, Ekelund R, Jackson J, Saba R, Saurman D. Smoking and absenteeism. Applied Economics. 1991;23:743–754. [Google Scholar]

- Bacharach S, Bamberger P, Doveh E, Cohen A. Retirement, social support and drinking behavior: A cohort analysis of males with a baseline history of problem drinking. Journal of Drug Issues. 2007;37:717–736. [Google Scholar]

- Bacharach SB, Bamberger PA, Sonnenstuhl WJ. Member assistance programs in the workplace: The role of labor in the prevention and treatment of substance abuse. ILR Press; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bacharach SB, Bamberger PA, Sonnenstuhl WJ. Driven to drink: Managerial control, work-related risk factors, and employee problem drinking. Academy of Management Journal. 2002;45:637–658. [Google Scholar]