Abstract

Ca2+ is a major determinant of many biochemical processes in various cell types and is a critical second messenger in cell signalling. High molecular weight calmodulin-binding protein (HMWCaMBP) was originally discovered and purified in the authors’ laboratory. It was identified as a homologue of calpastatin – an inhibitor of Ca2+-activated cysteine proteases (calpains). Decreased expression of HMWCaMBP in ischemia suggests that it is proteolyzed by calpains during ischemia and reperfusion. In normal myocardial muscle, HMWCaMBP may protect its substrate from calpains, but during an early stage of ischemia/reperfusion with increased Ca2+ influx, calpain activity exceeds HMWCaMBP activity, leading to proteolysis of HMWCaMBP and other protein substrates, resulting in cellular damage. The role of HMWCaMBP in ischemia/reperfusion is yet to be explored. The present review summarizes developments from the authors’ laboratory in the area of HMWCaMBP.

Keywords: Calcium, Calmodulin, Calpain, Calpastatin, High molecular weight calmodulin-binding protein, Ischemia, Reperfusion

Calmodulin (CaM) is a heat-stable acidic protein (1). One of the characteristics of CaM is its ability to associate with many different proteins in a Ca2+-dependent and reversible manner (2–3). A number of enzymes and proteins have been reported to be regulated by CaM (2,3). Although their biological roles are largely unknown, their molecular structures and modes of interaction with CaM appear to be diverse. A number of studies indicated that CaM-dependent enzymes and proteins exist in tissue-specific isoforms (4–6). This suggests that the tissue-specific function of CaM is partly dependent on the properties and distribution of CaM-binding proteins.

In many cases, CaM-regulated enzymes have been identified using in vitro testing of Ca2+-dependent CaM binding and its modulation of the activity of enzymes of known biological function. A number of CaM-dependent enzymes and proteins have been purified and extensively characterized as CaM-binding proteins before their intrinsic biological activity was established. For example, calcineurin (7) was discovered and purified as a CaM-binding protein (8,9) and had been extensively characterized before it was demonstrated to be a CaM-dependent protein phosphatase (10). Similarly, caldesmon was discovered as a CaM-binding protein (11) that has been implicated in the regulation of smooth muscle contraction (12–14). The high molecular weight protein that represents the most abundant CaM-binding protein in bovine heart was discovered and purified in our laboratory (15). The purpose of the present review article is to summarize some of the most significant advances performed in our laboratory in the study of high molecular weight CaM-binding protein (HMWCaMBP).

DISCOVERY OF HMWCaMBP

During purification of bovine heart CaM-dependent cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase using CaM-Sepharose 4B affinity column chromatography (15), we discovered that EGTA-eluted samples contained several CaM-binding proteins, including HMWCaMBP, which displayed a molecular mass of 140 kDa (15). CaM-deficient samples were prepared from a crude extract of bovine heart using DEAE-Sepharose CL-6B column chromatography (Pharmacia Corp, Sweden) (15). CaM-binding proteins were then isolated by CaM-Sepharose 4B affinity column chromatography (Figure 1, lane A). Such a preparation is expected to contain most, if not all, proteins that are capable of a reversible interaction with CaM. The further isolation of HMWCaMBP was based on manipulation of the elution conditions from the CaM-Sepharose 4B column to resolve the HMWCaMBP from the many other CaM-binding proteins (Figure 1, lanes B and C). HMWCaMBP was then purified to apparent homogeneity using Sepharose CL-6B column chromatography (Figure 1, lane D). The molecular mass of HMWCaMBP was determined to be 175 kDa from the sedimentation constant and Stokes radius of the protein. Sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of the protein showed a single protein band with an apparent molecular mass of 140 kDa. This indicated that the protein was monomeric (15). However, HMWCaMBP is highly susceptible to proteolysis. In addition, polyclonal antibodies raised against bovine heart HMWCaMBP were used to study the distribution of this protein in diverse bovine tissues. HMWCaMBP was also present in the lung and brain at a lower level than in the heart (16).

Figure 1).

Identification and purification of high molecular weight calmodulin (CaM)-binding protein (HMWCaMBP) from cardiac muscle. Heart tissue was homogenized in buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM magnesium acetate, 1 mM imidazole, pH 7.0, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol) and applied to a DEAE-Sepharose CL-6B column (Pharmacia Corp, Sweden); the eluate was applied to a CaM-Sepharose 4B column (15). Lanes A to C show the total CaM-binding protein fraction from the CaM-Sepharose 4B column eluted by 1.0 mM EGTA in buffer A in the presence of 0.2 M NaCl; 1.0 mM EGTA alone; and 1.0 mM EGTA containing 0.5 M NaCl, respectively. Lane D shows purified HMWCaMBP. Reproduced with the permission of Highwire Press from reference 15

BIOLOGICAL ROLE OF HMWCaMBP

To establish the biological functions of HMWCaMBP, the protein was digested with lysyl endopeptidase, which resulted in three purified peptides (H1, H2 and H3) that were used for partial peptide sequencing. Two peptides, H1 and H2, showed close homology to calpastatin, but the H3 peptide did not (17). These results suggested that HMWCaMBP could be a distinct protein that shares homology with calpastatin (17). Both calpastatin and calpains are ubiquitously expressed in different tissues (18–20). Calpains require Ca2+ and a reduced environment for their activity and play an important role in various physiological functions and pathological conditions (21). Calpastatin is an endogenous inhibitor of Ca2+-activated cysteine proteases (calpains). Calpains exist in two distinct forms, μ-calpain (calpain I) and m-calpain (calpain II), which are stimulated by micromolar and millimolar concentrations of Ca2+, respectively (22). To further test the possibility that HMWCaMBP contains calpastatin activity, the inhibition of m-calpain was performed by incubation with HMWCaMBP (17). HMWCaMBP inhibited the m-calpain activity in a concentration-dependent manner in the presence of Ca2+ (Figure 2A). To further substantiate that HMWCaMBP contains calpastatin activity, the inhibitory effect of HMWCaMBP on μ-calpain was examined. HMWCaMBP was also found to inhibit erythrocyte μ-calpain (Figure 2B). HMWCaMBP produced an essentially linear inhibition versus concentration relationship until at least 70% of the μ-calpain was inhibited. This is a typical feature of calpastatins, which are rapid, tightly binding inhibitors of calpains (23). In addition, HMWCaMBP appeared to possess four inhibitory domains per 80 kDa mass unit, as predicted for calpastatin (24). These results suggest that HMWCaMBP is a homologue of calpastatin. Furthermore, the polyclonal antibody raised against HMWCaMBP cross-reacted with calpastatin from bovine cardiac muscle, suggesting that both may have common antigenic epitopes (Figure 3).

Figure 2).

A Dose-dependent inhibition of calpain II (m-calpain) activity by high molecular weight calmodulin-binding protein (HMWCaMBP). HMWCaMBP inhibited the calpain II activity in a concentration-dependent manner in the presence of Ca2+. B Inhibition of human calpain I (μ-calpain) by both bovine cardiac HMWCaMBP and calpastatin. Purified calpain I at a concentration of 8 nM was assayed for caseinolytic activity in the presence of various concentrations of HMWCaMBP (•) and calpastatin (○). Both inhibited calpain I activity. Reproduced with the permission of the American Chemical Society from reference 17

Figure 3).

Western blot analysis of high molecular weight calmodulin-binding protein (HMWCaMBP) and calpastatin from bovine cardiac muscle. Purified HMWCaMBP and calpastatin from bovine cardiac muscle was subjected to 7.5% sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with anti-HMWCaMBP antibody. Lane 1, molecular weight marker; lane 2, HMWCaMBP; lane 3, calpastatin. Reproduced with the permission of the American Chemical Society from reference 17

ROLE OF HMWCaMBP IN ISCHEMIC MYOCARDIUM

Ischemia/reperfusion-induced myocardial injury leads to a wide range of structural and functional alterations (25). Defects in coronary blood flow due to occlusion and/or narrowing of coronary arteries can result in myocyte death at multiple sites in the ventricular wall (26). It was reported that, during ischemia and reperfusion, there is an increased influx of Ca2+ into the cells, which in turn increases the activity of calpains (27–29). Calpains are widely distributed in myocytes and are implicated in myocardial stunning and ischemia/reperfusion injury (27,28,30).

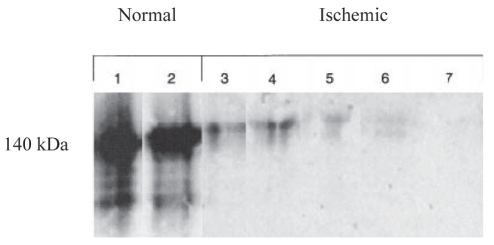

To investigate the distribution of HMWCaMBP in human cardiac muscle, ultrastructural localization studies were performed. These studies showed that in human cardiomyocytes, HMWCaMBP is distributed in the cytoplasm and myofilaments (Figure 4). Western blot analysis of normal and ischemic cardiac tissue homogenates indicated a strong immunoreactive band of HMWCaMBP in normal tissues, but in ischemic tissues, very little or no immunoreactivity was detected (Figure 5). Furthermore, the immunohistochemical study of normal human cardiac muscle showed strong to moderate staining of myocardial cells with the HMWCaMBP antibody, whereas ischemic tissue showed poor to negative staining (Figure 6). These observations suggest that HMWCaMBP exists mainly in cardiac muscle, binds to CaM and has an important role in the regulation of calpain activity in cardiac muscle (31). However, from this study, it was not clear what effect postmortem autolysis of tissues may have had on the most severely affected area and its possible contribution to myocardial damage due to hypoxia. Therefore, the role of HMWCaMBP along with calpains during ischemia and reperfusion was investigated in a rat model. Regional ischemia was induced in male rats and immunohistochemical studies were performed (32). The normal rat heart showed strong staining of HMWCaMBP (Figure 7A), whereas with an increase in the duration of ischemia, the expression of HMWCaMBP was significantly decreased (Figures 7B to 7G). Furthermore, an almost complete lack of expression of HMWCaMBP after 30 min ischemia and 30 min reperfusion was observed (Figure 7D). It has been reported that synthetic calpain inhibitors prevent proteolysis and contractile dysfunction during reperfusion (33), suggesting the involvement of calpains in proteolysis that characterizes reperfusion injury. Therefore, we examined the protective effect of cell-permeable inhibitor (N-acetylleucyl-leucyl-methioninal [ALLM]) on the preischemic perfused heart. The findings suggested that the expression of HMWCaMBP is increased with calpain inhibitor (ALLM treatment) (Figure 7H). In contrast to HMWCaMBP, μ-calpain and m-calpain expression increased during ischemia and reperfusion compared with control (Figure 8, group A versus groups B to G, panels 1 and 2), whereas preischemic perfusion and postischemic reperfusion with ALLM caused inhibition in the increase in μ-calpain and m-calpain expression (Figure 8, group H, panels 1 and 2). It is interesting to note that during ischemia alone, calpain expression did not increase significantly (Figure 8, group E, panels 1 and 2); however, with reperfusion, a significant increase in calpain expression was observed (Figure 8, groups F and G, panels 1 and 2) suggesting that the majority of calpain activity occurs during reperfusion. In addition, μ-calpain expression was increased after a shorter period of ischemia than for m-calpain. The Km of μ-calpain for Ca2+ has been reported to be 1 μM to 20 μM in vitro and 1 μM to 3 μM in vivo (19). μ-Calpain is activated when the short-lived elevation of Ca2+ concentration increases to 1 μM to 3 μM during myocardial ischemia. Therefore, μ-calpain is activated and can cleave m-calpain, thereby lowering its Ca2+ requirement to micromolar levels. In the ischemic heart, HMWCaMBP expression was low, which may have been due to the rise in calpain activity.

Figure 4).

Ultrastructural localization of high molecular weight calmodulin-binding protein (HMWCaMBP) in human cardiac myocytes using the immunogold labelling technique demonstrates cytoplasmic (arrow) and myofilament (circles) immunoreactivity with the anti-HMWCaMBP antibody. Reproduced with the permission of John Wiley & Sons Inc from reference 31

Figure 5).

Immunoblot of high molecular weight calmodulin-binding protein from normal human cardiac tissue and ischemic cardiac tissue supernatants. Reproduced with the permission of John Wiley & Sons Inc from reference 31

Figure 6).

Immunoperoxidase staining of high molecular weight calmodulin-binding protein (HMWCaMBP) in ischemic cardiac tissue demonstrated lack of staining, whereas surviving muscle showed positive staining with anti-HMWCaMBP antibody. Reproduced with the permission of John Wiley & Sons Inc from reference 31

Figure 7).

Expression of high molecular weight calmodulin-binding protein in rat cardiac tissues after ischemia (I) and reperfusion (R). A Control, no I or R; B 5 min I, 30 min R; C 15 min I, 30 min R; D 30 min I, 30 min R; E 15 min I, 0 min R; F 15 min I, 5 min R; G 15 min I, 15 min R; H Hearts were perfused with 100 μM calpain inhibitor in 0.1% dimethyl sulphoxide (DM) for 5 min before 15 min of I and again during 15 min of R; I Hearts were perfused with 0.1% DM alone for 5 min before 15 min of I and again during 15 min of R. Reproduced with the permission of Elsevier Ltd from reference 32

Figure 8).

Expression of calpains in rat cardiac tissues after ischemia (I) and reperfusion (R). Panel 1 μ-calpain; Panel 2 m-calpain. Details for groups A to I for each panel are provided in Figure 7. DM Dimethyl sulphoxide. Reproduced with the permission of Elsevier Ltd from reference 32

In some cases of cardiac ischemia, HMWCaMBP was highlighted in the necrotic contraction band, but in surviving muscle, intact staining was observed. Contraction band necrosis develops almost immediately on reperfusion of irreversibly injured myocytes (26,29). Degradation of HMWCaMBP may partly account for contraction band necrosis and contractile failure of the myocardium after ischemia/reperfusion injury. Calpains are concentrated in the Z-disk – the site where myofibril disassembly begins (34). It has been reported that Ca2+ activates calpains, and treatment of purified myofibrils with Ca2+ causes rapid and complete loss of the Z-disk, and partial degradation of M-lines (35). One of the physiological functions of the Z-disk and M-lines is to maintain the architecture of myofibrils; their disintegration can lead to masses of disorganized filaments (34,36). Calpains degrade tropomyosin and protein C, which contribute to the stability of thin and thick filaments, and various other cardiac contractile proteins (desmin, troponin T, C and I filaments, nebulin, gelsolin, titin, alpha-actin and myosin) (37,38). Therefore, calpains have a unique specificity for degradation of structural proteins that serve to keep actin-myosin assemblies in the form of myofibrils. The decrease in HMWCaMBP expression could be responsible for increased activity of cytoplasmic calpains, causing a subsequent increase in myofibrillar turnover that comprises approximately 60% of the total proteins in myocardium (35). Disruption of myofibrils can cause functional deficiencies, structural deformations and mechanical stress to the cell, resulting in membrane breakdown, which serves as an early marker of cell death. Therefore, a balance between calpains and HMWCaMBP is important to determine whether myofibril proteins are targeted for degradation.

CONCLUSION

HMWCaMBP was originally purified in our laboratory and was identified as a homologue of calpastatin, which is a calpain inhibitor. Furthermore, our studies showed decreased expression of HMWCaMBP in ischemic tissue, suggesting that it may be susceptible to proteolysis by calpains during ischemia/reperfusion injury. In normal myocardial muscle, HMWCaMBP may protect its substrate from calpains; however, during an early phase of ischemia/reperfusion with increased Ca2+ influx, calpain activity exceeds the HMWCaMBP activity, leading to its proteolysis and the proteolysis of other substrates, resulting in cellular damage.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Saskatchewan. The authors express their sincere thanks to Dr Ponniah Selvakumar for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cheung WY. Calmodulin plays a pivotal role in cellular regulation. Science. 1980;207:19–27. doi: 10.1126/science.6243188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klee CB. Interaction of CaM with calcium and target proteins. In: Cohen P, Klee CB, editors. Molecular Aspects of Cellular Regulation. Vol. 5. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1988. pp. 35–56. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogers MS, Strehler EE. Calmodulin. In: Celio MR, Pauls T, Schwaller B, editors. Guidebook to the Calcium Binding Proteins. Oxford: Sambrook and Tooze, Oxford University Press; 1996. pp. 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kakkar R, Raju RV, Sharma RK. Calmodulin-dependent cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase (PDE1) Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;55:1164–86. doi: 10.1007/s000180050364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yokoyama N, Wang JH. Demonstration and purification of multiple bovine brain and bovine lung calmodulin-stimulated phosphatase isozymes. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:14822–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma RK. Diversity of calcium action in regulation of mammalian calmodulin-dependent cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase. Ind J Biochem Biophys. 2003;40:77–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klee CB, Crouch TH, Krinks MH. Calcineurin: A calcium- and calmodulin-binding protein of the nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1979;76:6270–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.12.6270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang JH, Desai R. Modulator binding protein. Bovine brain protein exhibiting the Ca2+-dependent association with the protein modulator of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:4175–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma RK, Desai R, Waisman DM, Wang JH. Purification and subunit structure of bovine brain modulator binding protein. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:4276–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewart AA, Ingebristen TS, Manalan A, Klee CB, Cohen P. Discovery of Ca2+- and calmodulin-dependent protein phosphatase: Probable identity with calcineurin (CaM-BP80) FEBS Lett. 1982;137:80–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(82)80319-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sobue K, Muramoto Y, Fujita M, Kakiuchi S. Purification of a calmodulin-binding protein from chicken gizzard that interacts with F-actin. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1981;78:5652–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.9.5652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adelstein RS, Eisenberg E. Regulation and kinetics of the actin-myosin-ATP interaction. Annu Rev Biochem. 1980;49:921–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.004421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh MP, Hartshorne DJ. Actomyosin in smooth muscle calcium and cell. In: Cheung WY, editor. Calcium and Cell Function. Vol. 3. Orlando: Academic Press; 1982. pp. 223–69. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walsh MP. Calcium regulation of smooth muscle contraction. In: Marme D, editor. Calcium and Cell Physiology. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1985. pp. 170–203. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma RK. Purification and characterization of novel calmodulin-binding protein from cardiac muscle. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:1152–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma RK. Tissue distribution of high molecular weight calmodulin-binding protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;181:493–7. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81446-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kakkar R, Raju RVS, Mellgren RL, Radhi J, Sharma RK. Cardiac high molecular weight calmodulin binding protein contains calpastatin activity. Biochemistry. 1997;36:11550–5. doi: 10.1021/bi9711083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saido TC, Sorimachi H, Suzuki K. Calpain: New perspectives in molecular diversity and physiological and pathological involvement. FASEB J. 1994;8:814–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Croall DE, DeMartino GN. Calcium-activated neutral protease (calpain) system: Structure, function, and regulation. Physiol Rev. 1991;71:813–47. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1991.71.3.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sorimachi H, Ishiura S, Suzuki K. Structure and physiological function of calpains. Biochem J. 1997;328:721–32. doi: 10.1042/bj3280721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carragher NO. Calpain inhibition: A therapeutic strategy targeting multiple disease states. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:615–38. doi: 10.2174/138161206775474314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wendt A, Thompson VF, Goll DE. Interaction of calpastatin with calpain: A review. Biol Chem. 2004;385:465–72. doi: 10.1515/BC.2004.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maki M, Hatanaka M, Takano E, Murachi T. Structure-function relationships of calpastatin. In: Mellgren RL, Murachi T, editors. Interaction of Calpastatin with Calpain. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1990. pp. 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takano E, Maki M, Mori H, et al. Pig heart calpastatin: Identification of repetitive domain structures and anomalous behaviour in polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Biochemistry. 1988;27:1964–72. doi: 10.1021/bi00406a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reimer KA, Jennings RB. Myocardial ischemia, hypoxia and infarction. In: Fozzard HA, Haber E, Jennings R, Katz A, Morgan H, editors. The Heart and Cardiovascular System. New York: Raven Press; 1986. pp. 1133–201. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beltrami CA, Finato N, Rocco M, et al. The cellular basis of dilated cardiomyopathy in humans. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1995;27:291–305. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(08)80028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iizuka K, Kawaguchi H, Kitabatake A. Effects of thiol protease inhibitors on fodrin degradation during hypoxia in cultured myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1993;25:1101–9. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1993.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshida K, Sorimachi Y, Fujiwara M, Hironaka K. Calpain is implicated in rat myocardial injury after ischemia or reperfusion. Jpn Circ J. 1995;59:40–8. doi: 10.1253/jcj.59.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steenbergen C, Murphy E, Watts JA, London RE. Correlation between cystolic free calcium, contracture, ATP and irreversible ischemic injury in perfused rat heart. Cir Res. 1990;66:135–46. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao WD, Liu Y, Mellgren R, Marban E. Intrinsic myofilament alterations underlying the decreased contractility of stunned myocardium: A consequence of Ca2+ dependent proteolysis. Cir Res. 1996;78:455–65. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kakkar R, Radhi JM, Rajala RVS, Sharma RK. Altered expression of high-molecular-weight calmodulin binding protein in human ischemic myocardium. J Pathol. 2000;191:208–16. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(200006)191:2<208::AID-PATH618>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kakkar R, Wang X, Radhi JM, Rajala RVS, Wang R, Sharma RK. Decreased expression of high-molecular-weight calmodulin binding protein and its correlation with apoptosis in ischemia reperfused rat heart. Cell Calcium. 2001;29:59–71. doi: 10.1054/ceca.2000.0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arthur GD, Belcaastro AN. A calcium stimulated cysteine protease involved in isoproterenol induced cardiac hypertrophy. Mol Cell Biochem. 1997;176:241–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bird JW, Carter JH, Triemer RE, Brooks RM, Spanier AM. Proteinases in cardiac and skeletal muscle. Fed Proc. 1980;39:20–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goll DE, Kleese WC, Okitani A, Kumamoto T, Cong J, Kapprell HP. Historical background and current status of the Ca2+ dependent protease system. In: Mellgren RL, Murachi T, editors. Intracellular Calcium Dependent Proteolysis. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1990. pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dayton WR, Reville WJ, Goll DE, Stromer MH. A Ca2+-activated protease possibly involved in myofibrillar protein turnover. Partial characterization of the purified enzyme. Biochemistry. 1976;15:2159–67. doi: 10.1021/bi00655a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koohmaraie M. Ovine skeletal muscle multicatalytic proteinase complex (proteosome): Purification, characterization and comparison of its effect on myofibrils with micro-calpain. J Anim Sci. 1992;70:3697–708. doi: 10.2527/1992.70123697x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sorimachi H, Kimura S, Kinbara K, et al. Structure and physiological functions of ubiquitous and tissue-specific calpain species. Muscle-specific calpain, p94, interacts with connectin/titin. Adv Biophys. 1996;33:101–22. doi: 10.1016/s0065-227x(96)90026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]