Abstract

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is typically complicated by progressive hemorrhagic necrosis, an autodestructive process of secondary injury characterized by progressive enlargement of a hemorrhagic contusion during the first several hours after trauma. We assessed the role of Abcc8, which encodes sulfonylurea receptor 1 (SUR1), in progressive hemorrhagic necrosis. After SCI, humans and rodents exhibited similar regional and cellular patterns of up-regulation of SUR1 and Abcc8 messenger RNA. Elimination of SUR1 in Abcc8−/− mice and in rats given antisense oligodeoxynucleotide against Abcc8 prevented progressive hemorrhagic necrosis, yielded significantly better neurological function, and resulted in lesions that were one-fourth to one-third the size of those in control animals. The beneficial effects of Abcc8 suppression were associated with prevention of oncotic (necrotic) death of capillary endothelial cells. Suppression of Abcc8 with antisense oligodeoxynucleotide after SCI presents an opportunity for reducing the devastating sequelae of SCI.

INTRODUCTION

Spinal cord injury (SCI) remains one of the foremost unsolved challenges in medicine. Worldwide, the incidence of SCI ranges from 10 to 83 per million people per year, with half of these patients suffering a complete transection of the spinal cord and one-third becoming tetraplegic (1). At present, no treatment that is available for use immediately after injury ameliorates the ultimate damage suffered by the patient. The consequences in terms of physical impairments, functional limitations, disabilities, societal restrictions, and economic impact are so large as to be practically immeasurable.

The unique architecture and functional organization of the spinal cord are such that trauma gives rise to both local and distal loss of function. Damage to gray matter leads to segmental sensorimotor dysfunction that is restricted to muscles and dermatomes innervated by neurons located at the level of injury. Much worse than segmental injury, however, is the damage to ascending and descending white matter tracts that results in dysfunction of all muscles and dermatomes below the level of the injury. As a result, the clinical outcome is determined largely by the extent of white matter damage (2); for example, paraplegia after cervical (neck region) SCI is due exclusively to white matter destruction. White matter may be damaged by primary injury or secondary injury. Primary injury that is due to shearing or physical disruption of tissues is irreversible, whereas primary physiological or metabolic abnormalities without severance of axons may be reversible. Nevertheless, any potentially reversible primary injury to white matter is invariably worsened by secondary injury, which converts reversible white matter damage to irreversible damage and which further expands the overall injury.

Research on rodent models of SCI has revealed a mechanism of secondary injury unique to the central nervous system (CNS) that is exquisitely damaging to white matter. During the hours after injury, a dynamic process ensues wherein a hemorrhagic contusion enlarges progressively, resulting in autodestruction of spinal cord tissues (3, 4). Individual discrete petechial hemorrhages appear, first around the site of injury and then in more distant areas (5). Because petechial hemorrhages (small spots of bleeding from capillaries) continue to form and coalesce, the lesion gradually expands, with a characteristic region of hemorrhage that caps the advancing front of the lesion (4). A small hemorrhagic lesion that initially involves primarily the capillary-rich gray matter enlarges severalfold in the 3 to 24 hours after injury (6, 7). Recently, the concept of lesion evolution was validated in humans, with lesion enlargement shown to occur primarily within the first 24 hours after injury (8). The advancing hemorrhage results from delayed, progressive catastrophic failure of the structural integrity of capillaries, a phenomenon termed progressive hemorrhagic necrosis (PHN) (9). PHN is particularly damaging because it greatly expands the volume of neural tissue destroyed by the primary injury. The capillary dysfunction implicit with PHN causes tissue ischemia and hypoxia (10), and the blood resulting from PHN is particularly toxic to CNS cells, especially to the myelin-forming oligodendrocytes of white matter (11), resulting in further injury to neural tissues from oxidative stress and inflammation. Together, these processes render PHN the most destructive mechanism of secondary injury known in the CNS.

De novo expression of sulfonylurea receptor 1 (SUR1)–regulated NCCa-ATP channels in capillary endothelial cells is critical for the temporal and spatial evolution of PHN after SCI (9). SUR1 is an adenosine triphosphate (ATP)–binding cassette (ABC) transporter, a large superfamily of integral membrane proteins encoded by more than 48 genes. Most ABC proteins couple ATP hydrolysis to the translocation of solutes, transporting endogenous substances, xenobiotics, or drugs across biological membranes (12). A small number of atypical ABC proteins, including the sulfonylurea receptors SUR1/Abcc8 and SUR2/Abcc9, mediate other processes (13, 14). The SURs are not transporters and by themselves perform no function. Instead, they undergo obligate association with heterologous pore-forming subunits to form ion channels. The canonical association is with Kir6.1/Kcnj8 or Kir6.2/Kcnj11 to form ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels, which are constitutively expressed in pancreatic β cells, in the CNS, and in the cardiovascular system. SUR1 also associates with a nonselective cation pore-forming subunit to form SUR1-regulated NCCa-ATP channels, which are not constitutively expressed but are up-regulated de novo after CNS injury (15). Although both types of channels are regulated by SUR1, the two have opposite functional effects in CNS injury: Opening of SUR1-regulated KATP channels causes hyperpolarization, which may be neuroprotective (16), whereas opening of SUR1-regulated NCCa-ATP channels causes depolarization, which leads to oncotic (necrotic) cell death (17, 18). Mutations of ABCC8 and ABCC9 that lead to loss or gain of function can manifest as various diseases in humans (13, 14), but to our knowledge, no pathological condition has been identified wherein manifestation of disease requires transcriptional up-regulation of an ABC protein.

Here, we studied human tissues from SCI patients and rodent models of SCI to determine the role of SUR1 in PHN after SCI. To avoid masking the consequence of secondary injury and its prevention by treatment, we used hemicord contusion models with modest primary white matter damage (fig. S3) (9, 17). We found that the regional and cellular patterns of de novo Abcc8/SUR1 transcription after SCI were similar in humans, mice, and rats and that gene suppression of Abcc8 in rodents, even for as little as 24 hours, prevented PHN, significantly reduced tissue loss, and preserved neurological function.

RESULTS

ABCC8/SUR1 in human SCI

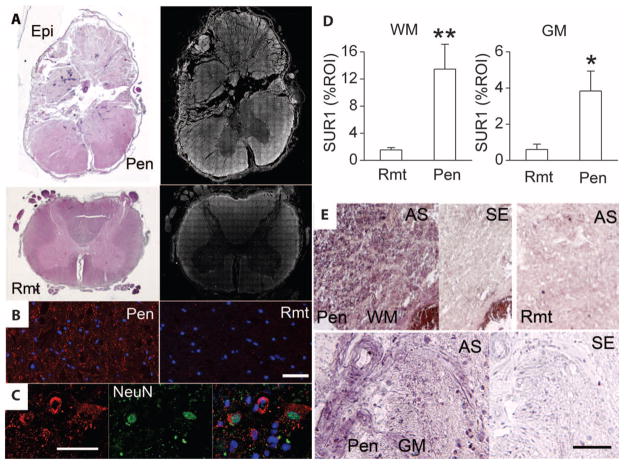

We studied spinal cord tissues from seven patients who died within 2 to 5 days of traumatic SCI (see table S1 for clinical details). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)–stained sections confirmed that there was often extensive mechanical disruption of tissues at the epicenter of injury (Fig. 1A, Epi). Penumbral tissues adjacent to the epicenter were grossly intact with no mechanical disruption (Fig. 1A, Pen). Spinal cord tissues remote from the epicenter always appeared normal with H&E staining (Fig. 1A, Rmt).

Fig. 1.

Abcc8 mRNA and SUR1 protein are up-regulated in human SCI. (A) Sections of spinal cord showing the epicenter (Epi) and adjacent intact penumbral tissues (Pen) at C3, as well a remote region (Rmt) at T10, stained with H&E or immunolabeled for SUR1. The montages showing SUR1 immunolabeling (right) were constructed from multiple individual images, and positive labeling is shown in white pseudocolor. (B and C) High-magnification images of white matter (B) and gray matter (C) from the penumbra immunolabeled for SUR1 (red) and colabeled for nuclear NeuN (green), indicative of neurons; the superimposed image is also shown in (C). (D) Bar graphs comparing SUR1 expression in a region of interest (ROI) in remote versus penumbral white matter (WM) and gray matter (GM); data from six patients. **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05. (E) In situ hybridization for Abcc8 in penumbra or remote white matter or gray matter, with antisense (AS) or sense (SE) probes. Scale bars, 50 μm [(B) and (C)], 100 μm (E). The images shown are from patients 238 (A and B), 176 (C), 222, and 162 (E).

After SCI, SUR1 expression was prominent in penumbral tissues but less so in necrotic tissues at the epicenter (Fig. 1A). SUR1 expression tapered off visibly in tissues rostral and caudal to the injury (Fig. 1A). High-power views showed that SUR1 was expressed in white matter bundles as well as in neurons (Fig. 1, B and C). Quantitative assessment indicated that SUR1 was ninefold more abundant in white matter and sevenfold more abundant in gray matter in penumbral regions compared to remote regions (Fig. 1D).

In situ hybridization showed more abundant ABCC8 messenger RNA (mRNA) in penumbral tissues compared to remote tissues, confirming transcriptional up-regulation of SUR1 (Fig. 1E). In situ hybridization showed widespread ABCC8 mRNA in white matter bundles, in individual cells, and in other structures (Fig. 1E). No specific labeling was present when we used sense probes in injured tissues or antisense probes in remote tissues, except for rare neuron-like cells (Fig. 1E).

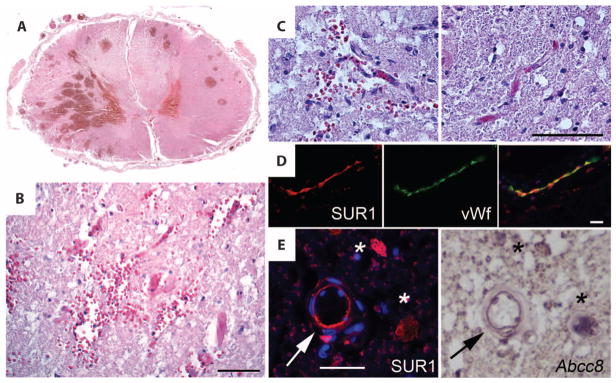

Although penumbral tissues adjacent to the epicenter appeared grossly intact with no mechanical disruption, microscopic examination sometimes (three patients) revealed the presence of discrete round intraparenchymal (petechial) hemorrhages (Fig. 2A) (19). At high magnification, penumbral tissues also showed areas with extravasated erythrocytes in the vicinity of microvessels (Fig. 2, B and C), as reported in rodent models of SCI (9, 17). High-power views of the penumbra showed expression of SUR1 in the endothelium of microvessels, which was confirmed with in situ hybridization (Fig. 2, D and E).

Fig. 2.

Secondary petechial hemorrhage in human SCI is associated with Abcc8 mRNA and SUR1 protein up-regulation in endothelium. (A) Section of spinal cord showing discrete secondary petechial hemorrhages in intact penumbra. (B and C) Magnified views of penumbral gray matter showing extravasated erythrocytes near microvessels (B and C, left); a normal microvessel without extravasated erythrocytes from the contralateral side is also shown (C, right). (D) High-magnification images of a microvessel in the penumbra immunolabeled for SUR1 (red) and colabeled for von Willebrand factor (vWf) (green), indicative of endothelium. The superimposed image is also shown. (E) High-magnification images of penumbral gray matter arteriole (arrow) immunolabeled for SUR1 (red) or hybridized in situ with probes complementary to Abcc8 mRNA, confirming specific SUR1 protein and Abcc8 mRNA colocalization in endothelium. Asterisks indicate neuron-like cells with colocalization of SUR1 protein and Abcc8 mRNA. Scale bars, 50 μm [(B), (C), and (E)], 100 μm (D). The images shown are from patients 175 (A), 119 (B to D), and 162 (E).

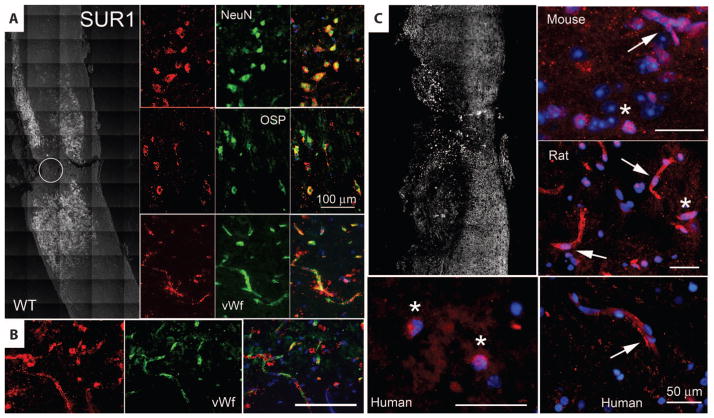

SUR1 in rodent models of SCI

Spinal cord tissues from mice and rats (9) also showed up-regulation of SUR1 after SCI. As with human tissues, SUR1 was up-regulated in the area of injury and gradually tapered off several millimeters rostral and caudal to the injury (Fig. 3A). Major cell types, including neurons and oligodendrocytes, exhibited prominent up-regulation of SUR1 (Fig. 3A). Up-regulation of SUR1 was also evident in capillaries (Fig. 3, A and B). Overall, the regional and cellular patterns of Abcc8/SUR1 expression after SCI in mouse and rat were similar to those in humans, consistent with a high degree of cross-species correspondence in the Abcc8/SUR1 response to spinal cord trauma.

Fig. 3.

SUR1 up-regulation is associated with the transcription factor Sp1. (A) Immunohistochemical localization of SUR1 24 hours after hemicord T9 SCI in wild-type mice. Left panel is a montage of images, with positive immunolabeling indicated as white pseudocolor. Circle denotes impact site. Right panels show high-magnification images of injured spinal cord colabeled for NeuN, OSP, or von Willebrand factor (all green), indicative of neurons, oligodendrocytes, or microvascular endothelium, respectively. Superimposed images are shown in the right column. Images shown are representative of findings in three mice. (B) Immunohistochemical localization of SUR1 (red) in capillaries colabeled for von Willebrand factor (green) after hemicord C7 SCI in rat. (C) Immunohistochemical localization of Sp1 24 hours after SCI in mouse, rat, and human, as indicated. The left upper panel is a montage of images after hemicord T9 SCI in a wild-type mouse, with positive immunolabeling indicated in white. High-power views of penumbral fields from mouse, rat, and human are also shown. Nuclei were labeled with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Pink nuclei indicate nuclear localization of Sp1. Arrows point to capillaries. Asterisks indicate neurons. Scale bars, 50 μm (C), 100 μm [(A) and (B)].

Sp1 transcription factor in SCI

The promoter regions of human, mouse, and rat Abcc8 all contain consensus sequences for binding of the transcription factor specific protein 1 (Sp1), and Sp1 drives expression of SUR1 in a concentration-dependent manner (20). The association between Abcc8 and Sp1 has been validated for CNS cells in vivo after ischemic injury (18). After SCI, both human and rodent tissues showed up-regulation of Sp1 in a distribution pattern similar to that of SUR1, with nuclear localization in both neurons and endothelial cells (Fig. 3C). These findings suggest that Sp1 may be part of the transcriptional program responsible for up-regulation of SUR1/Abcc8 after SCI.

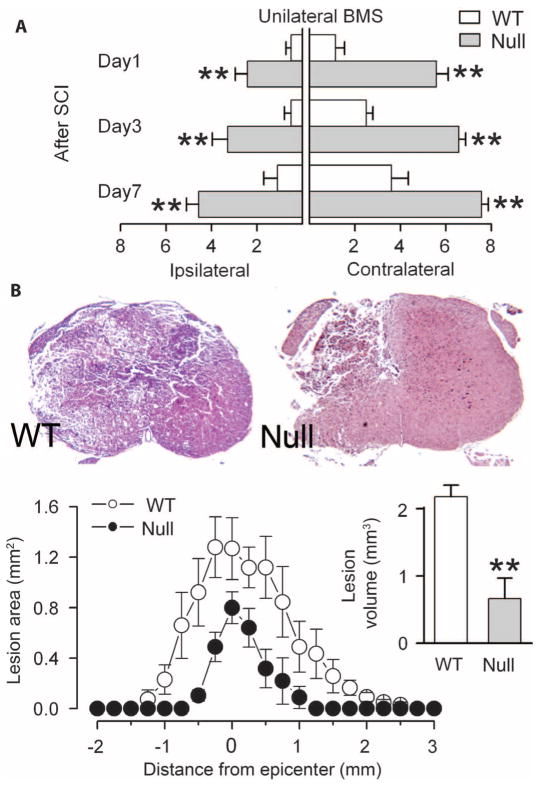

Outcomes of SCI in Abcc8−/− mice

To better understand the role of SUR1/Abcc8 in SCI, we examined the effect of hemicord injury at T9 in wild-type and transgenic mice in which Abcc8 had been silenced (Abcc8−/−) (21). We measured neurological function using the Basso Mouse Scale (BMS) (22), modified for unilateral scoring. Ipsilateral and contralateral BMS scores were consistently better in Abcc8−/− mice compared to wild-type mice (Fig. 4A). In wild-type mice 24 hours after injury, the hindlimb ipsilateral to the injury typically exhibited flaccid paralysis (no ankle movement), whereas in Abcc8−/− mice the ipsilateral hindlimb exhibited extensive ankle movement with occasional plantar placement. More striking, in wild-type mice 24 hours after injury, the contralateral hindlimb typically exhibited only minor ankle movement without plantar placement, whereas in Abcc8−/− mice the contralateral hind-limb exhibited consistent plantar stepping with at least some coordination. Some recovery of function was evident in both groups, but better performance in Abcc8−/− was durable for the full week of observation. Near-total recovery of function on the contralateral side by day 7 attested to minimal expansion of PHN in Abcc8−/− mice with unilateral injury.

Fig. 4.

Abcc8−/− mice are protected after SCI. (A) Ipsilateral and contralateral hindlimb function in wild-type (WT) and Abcc8−/− (null) mice, assessed using unilateral BMS on days 1 to 7 after unilateral T9 SCI (score in uninjured mice, 9; seven mice per group). **P < 0.01. (B) Low-power views of sections stained with H&E 7 days after SCI in WT and Abcc8−/− mice. Lesion areas and lesion volumes are shown for the same mice. **P < 0.01.

Lesion volumes, measured in the same mice, showed that silencing Abcc8 was associated with significant protection from tissue necrosis (Fig. 4B).

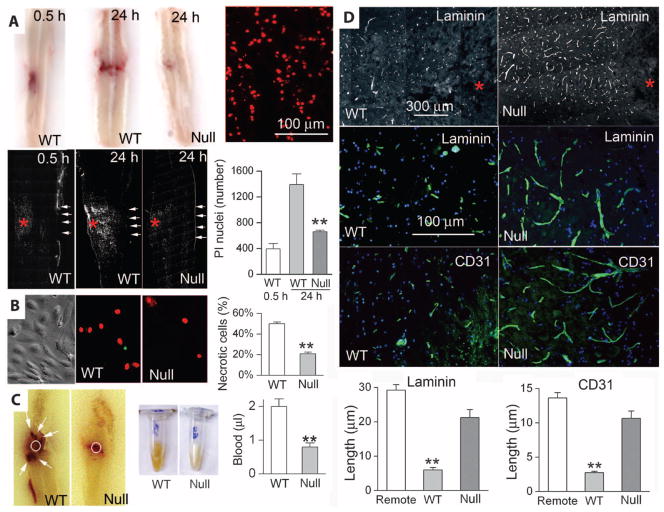

PHN in SCI in Abcc8−/− mice

As suggested by its name, PHN has two distinguishing features: (i) secondary necrosis and (ii) secondary hemorrhage (4). We tested for each of these separately, with necrosis assessed by using premortem administration of propidium iodide (PI) to label nuclei of necrotic cells and hemorrhage assessed by measuring extravasated blood.

The expanding nature of PHN was evident when we compared spinal cords at 30 min and 24 hours after injury. Both the expansion of the contusion and the spread of necrosis were apparent in tissues from wild-type mice (Fig. 5A). In wild-type mice, PI labeling 30 min after injury was confined to a limited region on one side of the cord, but by 24 hours, PI labeling was evident in a larger region both ipsilaterally and contralaterally (Fig. 5A). By contrast, in Abcc8−/− mice, PI labeling at 24 hours remained confined to a limited region on the injured side that was no larger and no more prominent than that observed at 30 min (Fig. 5A), consistent with significant protection from secondary necrosis.

Fig. 5.

Abcc8−/− mice have less necrosis and hemorrhage after SCI. (A) Longitudinal sections of spinal cords, obtained at the times indicated, from WT and Abcc8−/− (null) mice that sustained hemicord T9 SCI and were administered PI before death to identify necrotic cells. The sections shown either were unprocessed to demonstrate expanding contusion in WT but not in Abcc8−/− mice (top row, left) or were imaged with a fluorescent microscope to visualize PI-positive nuclei at high magnification at 24 hours in a WT mouse (red dots, top row right) or at low magnification at the times indicated and in the mice indicated (white dots, lower row of images). Asterisks, impact site; rows of arrows, pial surface contralateral to the impact site. Bar graph, mean ± SEM of PI-positive nuclei in the indicated conditions (three to five mice per group). **P < 0.01. (B) Phase-contrast (left) and fluorescent (middle and right) images of primary cultures of TNFα-exposed brain microvascular endothelial cells from WT and Abcc8−/− (null) mice. After depleting ATP, necrotic cells were identified with PI. Bar graph, percent (mean ± SEM) necrotic cells for each condition (n = 6). **P < 0.01. (C) Longitudinal sections (left) and homogenates (middle) of spinal cords from WT and Abcc8−/− (null) mice 24 hours after hemicord T9 SCI. Bar graph, volume (mean ± SEM) of extravasated blood (five mice per group). **P < 0.01. (D) Sections from the penumbra of wild-type and Abcc8−/− (null) mice 24 hours after sustaining hemicord T9 SCI, immunolabeled for laminin or CD31. Asterisks, impact sites. Bar graphs, lengths (mean ± SEM) of capillaries measured with laminin or CD31 in three groups of mice, as indicated. **P < 0.01. Images shown are representative of three mice per group.

To confirm the critical relation between SUR1 expression and necrotic cell death, we studied necrotic death of primary cultured brain microvascular endothelial cells isolated from wild-type and Abcc8−/− mice. Cells were exposed to tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), which induces expression of SUR1-regulated NCCa-ATP channels in normal endothelial cells (23), and were then subjected to ATP depletion, which induces necrotic death. In cells from wild-type mice, ATP depletion resulted in rapid death of 50% of the cells. By contrast, ATP depletion resulted in necrotic death of only 20% of Abcc8−/− cells (Fig. 5B), consistent with a lethal role of Abcc8/SUR1 under severe pathological conditions.

The second distinguishing feature of PHN is secondary hemorrhage (Fig. 5C), which results in extravasation of blood over a protracted time course [t1/2 = 6 to 8 hours (9, 24)]. In wild-type mice, the injury (22) resulted in formation of numerous secondary petechial hemorrhages surrounding the site of primary injury, whereas in Abcc8−/− mice secondary petechial hemorrhages were not apparent (Fig. 5C). In wild-type mice, the volume of extravascular blood 24 hours after injury was ~2 μl, whereas in Abcc8−/− mice only half of this amount of blood was present at 24 hours (Fig. 5C). Formation of secondary hemorrhages in wild-type mice was associated with significant (P < 0.01) fragmentation of capillaries in the penumbra surrounding the injury, a phenomenon that was absent in Abcc8−/− mice (Fig. 5D), in agreement with a protective role of Abcc8−/− against necrosis of microvascular endothelial cells shown above.

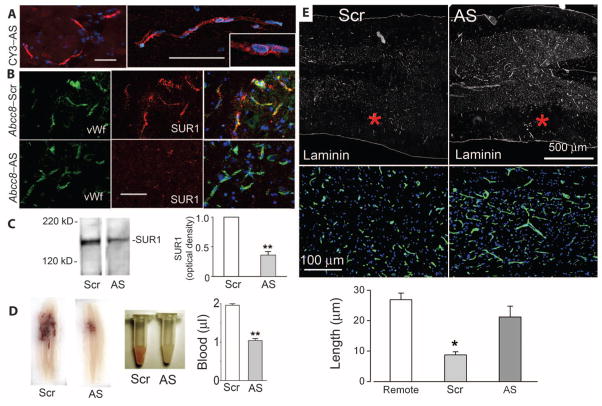

Abcc8 in a rat model of SCI

We also studied rats because they are more similar to humans than mice with respect to long-term pathological sequelae of SCI (4). For these experiments, we used a cervical-level injury, the most common type of injury in humans. To study gene suppression of Abcc8 in rats, we used Abcc8 antisense oligodeoxynucleotide (Abcc8-AS). We reasoned that an antisense strategy would be effective if SUR1 is transcriptionally up-regulated after trauma and that antisense could potentially be implemented as a treatment in humans. Scrambled oligodeoxynucleotide (Abcc8-Scr) was used as control. The Abcc8-AS that we used had been previously validated (25), and both oligodeoxy-nucleotides were phosphorothioated at four distal bonds to protect them from endogenous nucleases. Rats were infused intravenously with Abcc8-AS or Abcc8-Scr for only 24 hours, beginning 15 min after SCI.

We first studied the cellular localization of fluorescent CY3-conjugated Abcc8-AS (CY3-Abcc8-AS). After 24 hours of intravenous infusion, followed by washout of intravascular contents, CY3-Abcc8-AS was found in abundance in the liver and kidney. In the spinal cord, CY3-Abcc8-AS was prominent in the core of the lesion, where numerous intact cells were labeled. We were unable to discern whether CY3-Abcc8-AS reached cells in the core by traversing an intact blood–spinal cord barrier or whether it entered the tissues by being extravasated with blood via fragmented capillaries. However, in the penumbra, where tissues were intact, uptake of CY3-Abcc8-AS was prominent in capillaries (Fig. 6A), and little CY3-Abcc8-AS appeared to traverse capillaries and label parenchymal cells. No fluorescent label was detected in more distant normal capillaries or other tissues of the spinal cord or brain. Thus, in the CNS, only the injured spinal cord was labeled by CY3-Abcc8-AS, with the core of the lesion exhibiting diffuse pan-cellular uptake and the penumbra exhibiting uptake by capillaries.

Fig. 6.

Abcc8-AS reduces secondary hemorrhage and capillary fragmentation. (A) Fluorescence images of the penumbra 24 hours after hemicord C7 SCI in a rat administered CY3-Abcc8-AS (red) by constant infusion for 24 hours after SCI, showing uptake of CY3-Abcc8-AS by capillary endothelial cells at different magnifications, with intranuclear localization suggested by pink nuclei (inset). Rats were perfused to remove intravascular contents. Nuclei are labeled with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 50 μm. (B) Penumbral tissues immunolabeled for SUR1 (red) and double-labeled for von Willebrand factor (green) 24 hours after SCI in rats given Abcc8-Scr or Abcc8-AS, showing reduced expression of SUR1 in capillaries with Abcc8-AS. Scale bar, 50 μm. Images shown are representative of findings in three rats in each group. (C) Immunoblots for SUR1 in tissues obtained 24 hours after SCI from rats administered Abcc8-Scr or Abcc8-AS. Bar graph, densitometric analysis of immunoblots (three rats per group). **P < 0.01. (D) Spinal cord sections and homogenates from rats administered Abcc8-Scr or Abcc8-AS. Bar graph, spectrophotometric quantification of extravasated blood 24 hours after SCI in spinal cord homogenates from rats administered Abcc8-Scr or Abcc8-AS after SCI (five rats per group). **P < 0.01. (E) Sections of penumbra at two magnifications immunolabeled for laminin showing fragmentation of capillaries in rats administered Abcc8-Scr and elongated, intact capillaries in rats administered Abcc8-AS. Asterisks indicate site of impact. The images shown are representative of findings in three rats per group. Bar graph, length of capillaries measured with laminin in three groups of rats, as indicated. Remote sections were from 7 mm proximal to the injury. *P < 0.05.

Immunolabeling and immunoblotting confirmed that administration of Abcc8-AS resulted in a significant decrease in SUR1 expression (Fig. 6, B and C).

Outcome of SCI after brief systemic infusion of Abcc8-AS

In subsequent experiments, rats were infused intravenously with unlabeled Abcc8-AS or Abcc8-Scr for 24 hours, beginning 15 min after SCI.

In one series, spinal cords were examined 24 hours after hemicord injury to assess secondary hemorrhage. Spinal cords of control rats administered Abcc8-Scr examined 24 hours after SCI showed prominent bleeding internally, which consisted of a central region of hemorrhage at the impact site plus numerous discrete secondary petechial hemorrhages in tissues remote from the impact site (Fig. 6D). Administration of Abcc8-AS resulted in a reduction in petechial hemorrhages, which was confirmed by examining homogenates of injured tissues harvested after perfusion washout of intravascular contents (Fig. 6D). In rats administered Abcc8-Scr, trauma resulted in accumulation of ~2 μl of extravasated blood measured 24 hours after injury, whereas in rats administered Abcc8-AS extravasated blood at 24 hours was ~1 μl, consistent with elimination of secondary hemorrhage (Fig. 6D).

The reduction in secondary hemorrhage correlated with a significant (P < 0.05) reduction in fragmentation of capillaries in the penumbra. In rats administered Abcc8-Scr, broken fragments of capillaries were prominent in penumbral tissues adjacent to the site of injury, consistent with failure of capillary integrity (Fig. 6E). By contrast, in rats administered Abcc8-AS, intact elongated capillaries were present in penumbral tissues, in the same regions where CY3-Abcc8-AS had been localized (Fig. 6E).

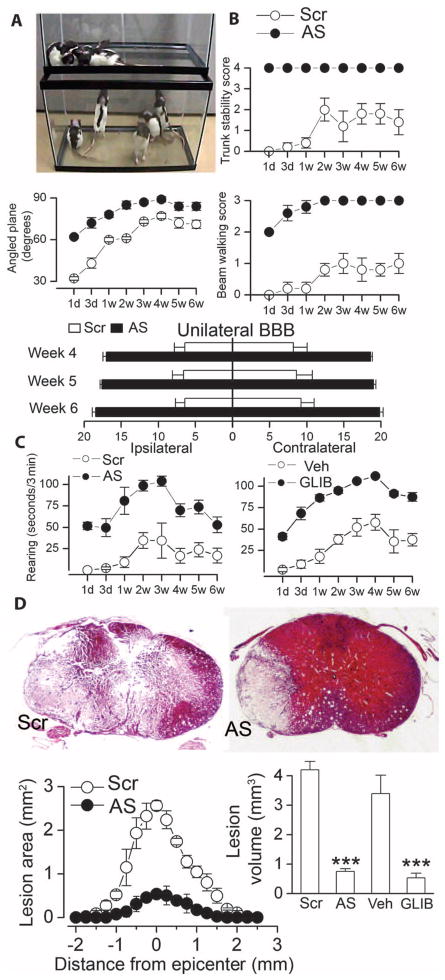

In another group of rats, we performed serial measurements of neurological function over the course of 6 weeks after SCI. Neurological function was evaluated by (i) trunk stability; (ii) up-angled plane; (iii) beam walking; (iv) the Basso, Beattie, Bresnahan (BBB) Locomotor Rating Scale; and (v) quantified spontaneous rearing. Performance on an inclined plane requires successively more dexterous function of the limbs and paws, as the angle of the plane is increased. Trunk stability is an individually gradable function that is an excellent marker of cervical cord function. BBB scoring is a sensitive and reproducible instrument that is particularly useful for evaluating hindlimb function in rats after SCI (26). Beam walking and spontaneous rearing, coerced and noncoerced tasks, respectively, are complex motor exercises that require balance, trunk stability, bilateral hindlimb dexterity and strength, and at least unilateral forelimb dexterity and strength, which, in combination, are excellent markers of cervical cord function (9).

Performance on all functional tests was consistently better in rats administered Abcc8-AS compared to Abcc8-Scr (Fig. 7, A to C). For each test, the difference between groups was significant (P < 0.01) and was maintained for the full 6 weeks of observation, even as recovery proceeded and reached a plateau or as animals habituated to non-coerced tasks. By week 4, all rats that had received Abcc8-AS exceeding a score of 15 bilaterally and none that had received Abcc8-Scr achieved a score of 15 on either side (see movie S1 showing spontaneous activity of the two groups of rats 1 week after injury).

Fig. 7.

Abcc8-AS and glibenclamide preserve neurological function after SCI. (A) Image captured from movie S1 depicting spontaneous locomotor activity 1 week after C7 hemicord SCI in rats administered Abcc8-Scr (upper tank) or Abcc8-AS (lower tank) for 24 hours after SCI (five rats per group). All subsequent panels in this figure are from these same rats. (B) Truncal stability, performance on up-angled plane, beam walking, and ipsilateral and contralateral hindlimb BBB scores (score in uninjured rats, 21), measured at the times indicated after SCI. For all tests, treatment groups at each time were significantly different (P < 0.01, except for weeks 4 and 5 for angled plane). (C) Quantified spontaneous rearing, measured at the times indicated after SCI, in rats administered Abcc8-AS versus Abcc8-Scr, or glibenclamide (GLIB) versus vehicle (Veh), as indicated. Treatment groups at each time were significantly different (P < 0.01). (D) Low-power views of sections stained with H&E 6 weeks after SCI. Lesion areas and volumes are also shown, as are lesion volumes for rats administered glibenclamide or vehicle, as indicated (five rats per group). Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. ***P < 0.001.

For comparison, we also examined the effect of pharmacological block of SUR1 with the potent inhibitor glibenclamide in the same injury model (9). As with Abcc8-AS, glibenclamide treatment resulted in significantly (P < 0.01) better performance in spontaneous rearing during 6 weeks of observation compared to vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 7C).

The spinal cords of the rats administered Abcc8-AS or Abcc8-Scr, as well as those administered glibenclamide or vehicle, were examined after the 6 weeks of testing to determine lesion characteristics. Administration of Abcc8-AS for only 24 hours after injury resulted in a fourfold reduction (P < 0.001) in lesion volume (Fig. 7D). Similarly, rats treated with glibenclamide exhibited a three- to fourfold (P < 0.001) reduction in lesion volume (Fig. 7D). Moreover, cyst formation and cavitation of the spinal cord, which were present in controls, were absent in rats administered Abcc8-AS or glibenclamide (Fig. 7D).

DISCUSSION

Most diseases that involve the ABC transporter superfamily of proteins are attributable to mutations that lead to loss of function (27). Here, we have described transcriptional up-regulation of an ABC protein that is directly linked to a harmful pathological process, the tissue destruction that follows spinal cord injury. Transcriptional up-regulation and activation of Abcc8/SUR1 in SCI may be compared to gain-of-function mutations of SUR1, as both lead to disease states that result from persistent activation of the associated channel. In the case of the pancreatic KATP channel, gain-of-function mutations result in persistent hyperpolarization of pancreatic β cells and a consequent deficient release of insulin that can cause neonatal diabetes (28). Overexpression and activation of the SUR1-regulated NCCa-ATP channel results in persistent depolarization of endothelial cells (29), causing increased susceptibility to cell death induced by ATP depletion (Fig. 5B) (9, 17), as well as secondary necrosis and secondary hemorrhage induced by spinal cord trauma. Despite the opposite effects of the two channels on cell polarization, both neonatal diabetes in humans (28) and SCI in animal models (9) are favorably treated by glibenclamide at doses too low to appreciably affect other ABC proteins (30).

Our data show that Abcc8 transcription is integral to the CNS injury response. Previous work on CNS injury showed that the SUR1 blocker glibenclamide improves outcome in animal models of CNS ischemia and trauma (9, 18, 23), as well as in humans with ischemic stroke (31). However, specific molecular evidence was lacking to definitively implicate Abcc8 in CNS injury. Moreover, because sulfonylurea drugs such as glibenclamide are general inhibitors of ABC transporters (30), they are not specific for SUR1. Here, we used two gene suppression strategies that target Abcc8 in mice and rats, finding that both approaches improved outcomes after SCI that were as favorable as effects of glibenclamide, supporting the hypothesis that glibenclamide acts via SUR1 and not via another ABC protein.

Expression of Abcc8/SUR1 in capillary endothelial cells appears to be of particular importance with regard to secondary injury after SCI. Edema and secondary hemorrhage, which are linked to expression of SUR1-regulated NCCa-ATP channels in capillaries (15, 32, 33), can amplify the primary injury and may contribute more to secondary injury and tissue loss in SCI than is generally recognized. After spinal cord trauma, the lesion enlarges by an advancing front of hemorrhage that caps the expanding lesion (4). Bleeding into the spinal cord results not only from the physical damage to tissues due to the original trauma (primary hemorrhage) but also from delayed failure of microvessels in the advancing front (secondary hemorrhage), a process that can go on for hours after injury. PHN is responsible for a twofold or more increase in the volume of extravasated blood during the first 24 hours after injury compared to the amount present shortly after trauma (9, 24). The fact that CY3-Abcc8-AS was localized predominantly in penumbral capillaries suggests that a major effect of treatment with either Abcc8-AS or glibenclamide was due to inhibition of SUR1 in capillaries. Abcc8/SUR1 was also up-regulated in parenchymal cells, however, including gray matter neurons and white matter oligodendrocytes, and inhibition of SUR1-regulated NCCa-ATP channels in such cells effectively blocks their oncotic (necrotic) death (18). Thus, the protective effects of Abcc8-AS may be due to inhibition of SUR1 in neurons and oligodendrocytes as well as in capillary endothelial cells.

We have shown here that both ABCC8 mRNA and SUR1 protein were up-regulated after traumatic SCI in humans. These gene products were sparsely expressed in uninjured spinal cords but were found in abundance in the spinal cords of patients examined within 2 to 5 days of SCI. Expression was greatest in penumbral tissues near the epicenter, and tapered off with distance, remaining prominent for several centimeters rostral and caudal, especially in the dorsal columns. Both mRNA and protein colocalized in neurons and microvessels, including capillaries and arterioles. Moreover, Sp1 up-regulation and nuclear translocation were also prominent, consistent with the fact that Sp1 is critical for transcriptional up-regulation of Abcc8/SUR1 (20). Each of these findings in humans closely replicated our data in mice and rats (9). The similarity in the regional and cellular patterns of SUR1 mRNA and protein up-regulation after injury suggests that pathophysiological mechanisms involving Abcc8/SUR1 may be similar in all three species.

Oligodeoxynucleotides have not yet gained widespread acceptance for the treatment of human diseases (34), in part because of an inflammatory response when they are administered for long periods of time and because of difficulties in reliably targeting the desired tissues or cells. SCI may present a unique opportunity for therapeutic use of these agents. The 24-hour-long administration of oligodeoxynucleotide, which effectively ameliorated injury, was too short to induce an inflammatory response in rats. Also, by a mechanism yet to be elucidated, oligodeoxynucleotides appeared to be specifically taken up by the penumbral capillary endothelial cells that are likely responsible for PHN.

Each year, traumatic injury to the spinal cord devastates the lives of thousands of people worldwide. In the United States, 250,000 people live with SCI and 11,000 new cases are added yearly. Short of preventing primary injury, the best hope for reducing the life-long impact of SCI rests with decreasing the secondary injury that results from PHN occurring during the acute phase after trauma. Although progress has been made in axonal and dendritic remodeling, cell replacement therapies, and rehabilitation, these treatments work best when administered to patients with the smallest possible lesion. To date, clinical trials with agents such as methylprednisolone (NASCIS II and III) and GM-1 ganglioside have shown risk-benefit profiles that are not sufficiently favorable to warrant routine clinical use, and other therapies intended for treatment in the acute phase have yet to be proven (35). Here, we demonstrate that in the earliest phase after trauma, Abcc8 mRNA and its product, SUR1, are up-regulated in human, as well as in mouse and rat, and that in animal models of SCI, suppressing this gene or inhibiting its product reduces secondary injury. Notably, administration of Abcc8-AS for only 24 hours after injury was sufficient for effective protection that was durable for 6 weeks. Future studies will be needed to determine the therapeutic window for Abcc8-AS as well as for SUR1 inhibitors such as glibenclamide. The possibility of administering Abcc8-AS to reduce de novo expression of the SUR1-regulated NCCa-ATP channel, coupled with administration of glibenclamide to block channels already expressed after injury, is a promising strategy for prevention of the devastating sequelae of spinal cord trauma in humans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human spinal cords

Clinical details are given in Supplementary Material.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin sections of human spinal cord tissues were processed and immunolabeled for SUR1 as detailed in Supplementary Material with a custom antibody to SUR1 described in Supplementary Material. Mouse and rat tissues were immunolabeled for SUR1 (1:200; 1 hour at room temperature and then 48 hours at 4°C; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Other primary antibodies included NeuN (1:100; 48 hours; Chemicon), OSP (1:100; Abcam), von Willebrand factor (1:100; 48 hours; Chemicon), CD31 (1:50; overnight; BD Pharmingen), and laminin (1:100; overnight; EY Labs). CY3- or fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) were used.

In situ hybridization

Digoxigenin-labeled probes (antisense, 5′-TGCAGGGGTCAGGG-TCAGGGCGCTGTCGGTCCACTTGGCCAGCCAGTA-3′), designed to hybridize to nucleotides 3217 to 3264 located within coding sequence of human ABCC8 gene (NM 00352), were supplied by GeneDetect. Hybridization was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (18).

Rodent models of SCI

Animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Maryland. Abcc8−/− mice, obtained as described (21), exhibited neurological function, gait, the normal maximum BMS score of 9, and spinal cord histology indistinguishable from wild-type (WT) mice. Female WT (C57BL/6) and Abcc8−/− mice (C57BL/6 background), 24 to 28 g, were anesthetized [ketamine (60 mg/kg) plus xylazine (7.5 mg/kg), intraperitoneally (ip)] and underwent a left hemicord contusion at T9 (0.6-mm impactor head; 10-g weight dropped vertically 5 mm) (17). Details for the unilateral cervical injury in rats are given in Supplementary Material. After SCI, mice and rats were given 2 or 10 ml of glucose-free normal saline subcutaneously. Temperature was maintained at ~37°C.

Suppression of Abcc8 in rats

We used Abcc8-AS (5′-GGCCGAGTGGTTCTCGGT-3′) for in vivo gene suppression (25) and Abcc8-Scr (5′-TGCCTGAGGCGTGGCTGT-3′) as control, and both were phosphorothioated at four distal bonds. Within 15 min of SCI, a loading dose of 300 μg in 300 μl of normal saline was given intravenously, and mini-osmotic pumps (Alzet 2001D, 8 μl/hour; Durect Corp.) with jugular vein catheters were implanted that delivered oligodeoxynucleotides in phosphate-buffered saline at a rate of 1 mg per rat per 24 hours (17).

Block of SUR1 in rats

Within 15 min of SCI, a loading dose of glibenclamide (10 μg/kg ip) was given, and a mini-osmotic pump (model 2001; 1.0 μl/hour; Durect) was implanted subcutaneously for continuous infusion of glibenclamide (200 ng/hour subcutaneously for 7 days) (33). Controls were administered vehicle (normal saline plus dimethyl sulfoxide) in the same way. We previously showed that inhibiting SUR1 does not influence hematocrit, serum electrolytes, blood clotting, blood pressure, or cerebral blood flow and has only modest effect on serum glucose (9, 18, 33)

Neurobehavioral assessments

All measurements were performed by two blinded evaluators. Vertical exploration (rearing) (9, 17), beam walking, inclined plane, BBB (36), and BMS (22) scoring were determined as described.

Tissue necrosis

Animals were administered PI to label necrotic cells in situ and, 45 min later, were killed and perfused with heparinized saline. Montages of longitudinal, fresh-frozen, postfixed sections through the epicenter were acquired using a motorized X-Y stage (Ludl), and PI-positive nuclei were counted using a segmentation algorithm (IPLab image analysis software).

Tissue blood

Animals were perfused with heparinized saline to remove intra-vascular blood, and 5-mm segments of cord encompassing the lesion were homogenized and processed using Drabkin’s reagent (9).

Lesion volumes

Lesion volumes were estimated as described (9).

In vitro necrotic cell death

Microvascular endothelial cells were isolated from brains of WT and Abcc8−/− mice by using CD31-coated beads, as described (37). Nearly confluent primary cultures were incubated with TNFα (20 ng/ml) overnight. ATP was depleted using sodium azide (1 mM) plus 2-deoxyglucose (10 mM) for 20 min. Cells were collected and resuspended in labeling reagent containing PI for 10 min and then counted. The number of cells exhibiting red nuclear staining was divided by the total number of cells.

Statistical analysis

Nonparametric data (serial scores for truncal stability, beam walking, BMS, and BBB) were analyzed by first rank-transforming the combined data, with tied ranks replaced by the average rank for the ties, and by using a repeated measures two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni comparisons between treatments at each time. All other data were analyzed with Student’s t test or a repeated measures two-way ANOVA with Tukey comparisons between treatments at each time.

Supplementary Material

www.sciencetranslationalmedicine.org/cgi/content/full/2/28/28ra29/DC1

Methods

Table S1. Clinical cases.

Fig. S1. Custom antibody is specific for SUR1.

Fig. S2. Rat model of cervical hemicord contusion used to incite progressive hemorrhagic necrosis with minimal primary white matter damage.

Fig. S3. Cervical hemicord contusion incites progressive hemorrhagic necrosis with minimal primary white matter damage.

Movie S1. Rats 1 week after SCI treated with Abcc8-Scr versus Abcc8-AS.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. L. Shyng (Oregon Health and Science University) for providing the hamster SUR1 clone.

Funding: Veterans Administration (Baltimore); National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute grant HL082517; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grants NS061808 and NS060801; and Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation (J.M.S.) and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grant NS061934 (V.G.).

Footnotes

Author contributions: J.M.S. conceived the study, participated in the analysis and interpretation of the data, and wrote the manuscript. S.K.W. designed and developed the custom antibody to SUR1 and designed in situ hybridization probes for Abcc8. M.D.N. and D.L. provided human specimens and aided in analyzing histopathology. C.T. performed immunolabeling and analysis for capillary fragmentation. Z.C. isolated and cultured microvascular endothelial cells from wild-type and SUR1-null mice and performed cell death experiments. S.I. performed most of the immunolabeling and all of the measurements of lesion volume after SCI. O.T. performed all of the surgical procedures for SCI and aided in evaluating neurobehavioral function of mice and rats. J.B. supplied SUR1-null mice. V.G. aided in the design of the experiments, analysis and interpretation of the data, and neurobehavioral assessment of mice and rats and contributed to writing the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests: J.M.S. holds a U.S. patent (number 7,285,574), “A novel non-selective cation channel in neural cells and methods for treating brain swelling.” J.M.S. is a member of the scientific advisory board and holds shares in Remedy Pharmaceuticals, a company that is developing small-molecule drugs targeting NCCa-ATP channels in acute CNS injury, including traumatic brain injury, stroke, and SCI. No support, direct or indirect, was provided to J.M.S., or for this project, by Remedy Pharmaceuticals.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Wyndaele M, Wyndaele JJ. Incidence, prevalence and epidemiology of spinal cord injury: What learns a worldwide literature survey? Spinal Cord. 2006;44:523–529. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayes KC, Kakulas BA. Neuropathology of human spinal cord injury sustained in sports-related activities. J Neurotrauma. 1997;14:235–248. doi: 10.1089/neu.1997.14.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steward O, Schauwecker PE, Guth L, Zhang Z, Fujiki M, Inman D, Wrathall J, Kempermann G, Gage FH, Saatman KE, Raghupathi R, McIntosh T. Genetic approaches to neurotrauma research: Opportunities and potential pitfalls of murine models. Exp Neurol. 1999;157:19–42. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guth L, Zhang Z, Steward O. The unique histopathological responses of the injured spinal cord. Implications for neuroprotective therapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;890:366–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawata K, Morimoto T, Ohashi T, Tsujimoto S, Hoshida T, Tsunoda S, Sakaki T. Experimental study of acute spinal cord injury: A histopathological study. No Shinkei Geka. 1993;21:45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balentine JD. Pathology of experimental spinal cord trauma. I. The necrotic lesion as a function of vascular injury. Lab Invest. 1978;39:236–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iizuka H, Yamamoto H, Iwasaki Y, Yamamoto T, Konno H. Evolution of tissue damage in compressive spinal cord injury in rats. J Neurosurg. 1987;66:595–603. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.66.4.0595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleming JC, Norenberg MD, Ramsay DA, Dekaban GA, Marcillo AE, Saenz AD, Pasquale-Styles M, Dietrich WD, Weaver LC. The cellular inflammatory response in human spinal cords after injury. Brain. 2006;129:3249–3269. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simard JM, Tsymbalyuk O, Ivanov A, Ivanova S, Bhatta S, Geng Z, Woo SK, Gerzanich V. Endothelial sulfonylurea receptor 1–regulated NCCa-ATP channels mediate progressive hemorrhagic necrosis following spinal cord injury. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2105–2113. doi: 10.1172/JCI32041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tator CH, Fehlings MG. Review of the secondary injury theory of acute spinal cord trauma with emphasis on vascular mechanisms. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:15–26. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.75.1.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Regan RF, Guo Y. Toxic effect of hemoglobin on spinal cord neurons in culture. J Neurotrauma. 1998;15:645–653. doi: 10.1089/neu.1998.15.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hollenstein K, Dawson RJ, Locher KP. Structure and mechanism of ABC transporter proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2007;17:412–418. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bryan J, Muñoz A, Zhang X, Düfer M, Drews G, Krippeit-Drews P, Aguilar-Bryan L. ABCC8 and ABCC9: ABC transporters that regulate K+ channels. Pflugers Arch. 2007;453:703–718. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0116-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burke MA, Mutharasan RK, Ardehali H. The sulfonylurea receptor, an atypical ATP-binding cassette protein, and its regulation of the KATP channel. Circ Res. 2008;102:164–176. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.165324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simard JM, Woo SK, Bhatta S, Gerzanich V. Drugs acting on SUR1 to treat CNS ischemia and trauma. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamada K, Inagaki N. Neuroprotection by KATP channels. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;38:945–949. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerzanich V, Woo SK, Vennekens R, Tsymbalyuk O, Ivanova S, Ivanov A, Geng Z, Chen Z, Nilius B, Flockerzi V, Freichel M, Simard JM. De novo expression of Trpm4 initiates secondary hemorrhage in spinal cord injury. Nat Med. 2009;15:185–191. doi: 10.1038/nm.1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simard JM, Chen M, Tarasov KV, Bhatta S, Ivanova S, Melnitchenko L, Tsymbalyuk N, West GA, Gerzanich V. Newly expressed SUR1-regulated NCCa-ATP channel mediates cerebral edema after ischemic stroke. Nat Med. 2006;12:433–440. doi: 10.1038/nm1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tator CH, Koyanagi I. Vascular mechanisms in the pathophysiology of human spinal cord injury. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:483–492. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.86.3.0483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hernández-Sánchez C, Ito Y, Ferrer J, Reitman M, LeRoith D. Characterization of the mouse sulfonylurea receptor 1 promoter and its regulation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18261–18270. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seghers V, Nakazaki M, DeMayo F, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J. Sur1 knockout mice. A model for KATP channel-independent regulation of insulin secretion. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9270–9277. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basso DM, Fisher LC, Anderson AJ, Jakeman LB, McTigue DM, Popovich PG. Basso Mouse Scale for locomotion detects differences in recovery after spinal cord injury in five common mouse strains. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23:635–659. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simard JM, Geng Z, Woo SK, Ivanova S, Tosun C, Melnichenko L, Gerzanich V. Glibenclamide reduces inflammation, vasogenic edema, and caspase-3 activation after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:317–330. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bilgen M, Abbe R, Liu SJ, Narayana PA. Spatial and temporal evolution of hemorrhage in the hyperacute phase of experimental spinal cord injury: In vivo magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2000;43:594–600. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(200004)43:4<594::aid-mrm15>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yokoshiki H, Sunagawa M, Seki T, Sperelakis N. Antisense oligodeoxynucleotides of sulfonylurea receptors inhibit ATP-sensitive K+ channels in cultured neonatal rat ventricular cells. Pflugers Arch. 1999;437:400–408. doi: 10.1007/s004240050794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Basso DM, Beattie MS, Bresnahan JC. Graded histological and locomotor outcomes after spinal cord contusion using the NYU weight-drop device versus transection. Exp Neurol. 1996;139:244–256. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1996.0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aittoniemi J, Fotinou C, Craig TJ, de Wet H, Proks P, Ashcroft FM. Review. SUR1: A unique ATP-binding cassette protein that functions as an ion channel regulator. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009;364:257–267. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J. Neonatal diabetes mellitus. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:265–291. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen M, Dong Y, Simard JM. Functional coupling between sulfonylurea receptor type 1 and a nonselective cation channel in reactive astrocytes from adult rat brain. J Neurosci. 2003;23:8568–8577. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-24-08568.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Golstein PE, Boom A, van Geffel J, Jacobs P, Masereel B, Beauwens R. P-glycoprotein inhibition by glibenclamide and related compounds. Pflugers Arch. 1999;437:652–660. doi: 10.1007/s004240050829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kunte H, Schmidt S, Eliasziw M, del Zoppo GJ, Simard JM, Masuhr F, Weih M, Dirnagl U. Sulfonylureas improve outcome in patients with type 2 diabetes and acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2007;38:2526–2530. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.482216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simard JM, Kent TA, Chen M, Tarasov KV, Gerzanich V. Brain oedema in focal ischaemia: Molecular pathophysiology and theoretical implications. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:258–268. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70055-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simard JM, Yurovsky V, Tsymbalyuk N, Melnichenko L, Ivanova S, Gerzanich V. Protective effect of delayed treatment with low-dose glibenclamide in three models of ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:604–609. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.522409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.White PJ, Anastasopoulos F, Pouton CW, Boyd BJ. Overcoming biological barriers to in vivo efficacy of antisense oligonucleotides. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2009;11:e10. doi: 10.1017/S1462399409001021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rossignol S, Schwab M, Schwartz M, Fehlings MG. Spinal cord injury: Time to move? J Neurosci. 2007;27:11782–11792. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3444-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Basso DM, Beattie MS, Bresnahan JC. A sensitive and reliable locomotor rating scale for open field testing in rats. J Neurotrauma. 1995;12:1–21. doi: 10.1089/neu.1995.12.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu Z, Hofman FM, Zlokovic BV. A simple method for isolation and characterization of mouse brain microvascular endothelial cells. J Neurosci Methods. 2003;130:53–63. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(03)00206-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

www.sciencetranslationalmedicine.org/cgi/content/full/2/28/28ra29/DC1

Methods

Table S1. Clinical cases.

Fig. S1. Custom antibody is specific for SUR1.

Fig. S2. Rat model of cervical hemicord contusion used to incite progressive hemorrhagic necrosis with minimal primary white matter damage.

Fig. S3. Cervical hemicord contusion incites progressive hemorrhagic necrosis with minimal primary white matter damage.

Movie S1. Rats 1 week after SCI treated with Abcc8-Scr versus Abcc8-AS.