Abstract

This study examines the effects of family characteristics, parental monitoring, and victimization by adults on alcohol and other drug (AOD) abuse, delinquency, and risky sexual behaviors among 761 incarcerated juveniles. The majority of youth reported that other family members had substance abuse problems and criminal histories. These youth were frequently the victims of violence. Relationships between victimization, parental monitoring, and problem behaviors were examined using structural equation modeling. Monitoring was negatively related to all problem behaviors. However, type of maltreatment was related to specific problem behaviors. The effects of family substance abuse and family criminal involvement on outcomes were mediated by monitoring and maltreatment. The study underscores the need to provide family-focused and trauma-related interventions for juvenile offenders.

Keywords: child victimization, parental monitoring, problem behaviors, incarcerated youth

Adolescents involved in the juvenile justice system engage in problem behaviors other than delinquency. Alcohol and other drug (AOD) use disorders are higher among juvenile offenders than adolescents in general (Cocozza, 1992). Juvenile offenders are more likely to be sexually active, to engage in sexual risk behaviors, and to be at higher risk for infection with HIV than their nondelinquent peers (Malow, Rosenberg, Donenberg, & Devieux, 2006). In addition, delinquency, sexual risk behavior, and AOD abuse often do not occur in isolation; rather, they tend to present simultaneously (Teplin et al., 2005).

Research has identified a set of family factors that may either increase the likelihood of involvement in problem behaviors or lessen the severity or duration of youth problems. Parental substance abuse, parent or sibling criminal involvement, domestic violence, and child victimization or maltreatment are recognized as risk factors for delinquency; having a stable family and good supervision or parental monitoring are considered protective factors against delinquent involvement (Huizinga, Weiher, Menard, Espiritu, & Ebensen, 1998). Child abuse (Cohen et al., 2000) and less parental monitoring (Laird, Pettit, Dodge, & Bates, 2003; Richards, Miller, O’Donnell, Wasserman, & Colder, 2004) also have been associated with substance abuse and sexual risk behavior for adolescents and adults.

Traditionally, studies of the impact of child victimization on youth problem behaviors have been conducted independently of research on parenting practices. If parental monitoring does indeed prevent a child’s involvement in delinquent activity or reduce the severity of such behavior, the question remains as to whether or not it has the same impact on other problem behaviors for children who have already become involved in the juvenile justice system. Furthermore, does this protective factor stay intact even when the child has experienced a number of stressors typically associated with victimization and maltreatment? The present study simultaneously examined the impact of victimization by adults, family risk, and family protective factors on three youth problem behaviors: AOD use, sexual risk behavior, and delinquency or juvenile justice system involvement. We focused on juvenile offenders because they are more likely to engage in problem behaviors than their nonoffending peers and because they are often victims of maltreatment and crime (Dembo, Williams, Schmeider, & Christensen, 1993).

This research integrated two models of delinquency to investigate family influences on multiple problem behaviors among juvenile offenders: the developmental damage model of delinquency originated by Dembo, Williams, Wothke, Schmeidler, and Brown (1992) and the social interaction model proposed by Patterson, Reid, and Dishion (1992), which incorporates both risk factors and family protective factors in its design. Child victimization and other family risk factors (Dembo et al., 1992) and parental monitoring (Patterson et al., 1992) were included in a structural equation model to examine the simultaneous relationships among victimization, parental monitoring, and problem behaviors for female and male juvenile offenders.

DEVELOPMENTAL MODELS OF ADOLESCENT PROBLEM BEHAVIOR

The developmental damage approach to youth problem behaviors (Dembo et al., 1992; Grella, Stein, & Greenwell, 2005) explains how family risk factors, including child maltreatment, can lead to juvenile justice and adult criminal justice involvement. Juvenile offenders frequently grow up in homes where mental illness, substance abuse or addiction, criminal justice involvement, and violence between family members are problems; these circumstances may contribute to adolescent problem behaviors (Robertson & Husain, 2001). Accordingly, family problems and youths’ early abuse experiences influence the youths’ initial involvement in drug use and delinquency. Once these problem behaviors become established, they tend to persist. A study of male juvenile offenders found that physical abuse, sexual abuse, and family mental illness or drug addiction were associated with youths’ marijuana use, drug sales, theft, and crimes against persons (Dembo et al., 1992). The research of Grella et al. (2005) also supported this model. It was found that early experiences of traumatic events, such as being a victim or a witness to assault by a stranger and foster care placement, were related to adult criminal behavior. The experience of childhood sexual abuse was mediated by adolescent substance abuse, and the effects of both childhood physical abuse and exposure to family violence on adult criminal behavior were mediated by adolescent conduct problems.

The second model drawn on in this study includes family protective and risk factors to explain the progression from aggressive and oppositional behavior in young children to adolescent antisocial behavior. Patterson et al. (1992) accounted for delinquent behavior in adolescents primarily through negative peer influence but suggested that poor parental monitoring and coercive family interactions during childhood explain the child’s association with deviant peers. The childrearing environment is also considered an important determinant in the development and maintenance of delinquency (Patterson & Yoerger, 2002). Disruptions in family life, such as unemployment, severe illness, divorce, and change in residence, were significantly associated with less effective monitoring and with increases in family conflict. In turn, family conflict and disrupted monitoring contributed to increased involvement with deviant peers.

CHILD VICTIMIZATION

Childhood experiences of abuse and victimization are associated with a number of adolescent problem behaviors. The relationship between child maltreatment by caregivers and victimization by other adults in juvenile delinquency and violent crimes has been well established (Stouthamer-Loeber, Loeber, Homish, & Wei, 2001). The evidence that abuse of alcohol and other drugs may be a consequence of physical or sexual abuse also is quite compelling (Perez, 2000). In addition, child maltreatment has been linked to various types of sexual risk behaviors (Bensley, Van Eenwyk, & Simmons, 2000), including unprotected sexual intercourse (Fergusson, Horwood, & Lynskey, 1997), teen pregnancy (C. Smith, 1996), and sexually transmitted infections among teenagers (Robertson, Thomas, St. Lawrence, & Pack, 2005).

Although many problem behaviors are manifested during the teen years, the cumulative effects of these experiences often persist well into adulthood (Johnsen & Harlow, 1996). Consistent with developmental damage theory, studies of adults with histories of child abuse and/or neglect have found higher rates of crime as teenagers and young adults compared with matched controls (Maxfield & Widom, 1996). Although alcohol abuse is more likely to be problematic for women with child sexual abuse histories than for men (Zierler et al., 1991), AOD problems are associated with childhood victimization for both genders (Malow et al., 2006). Moreover, a history of abuse is a significant predictor of HIV risk behavior for both males and females (Zierler et al., 1991).

Even though the outcomes of physical and sexual abuse pose problems for both men and women, evidence indicates that more women than men have been maltreated as children (Harlow, 1999). Moreover, females are much more likely to be sexually abused, to be abused by a relative, and to be abused for a longer period of time (Browne & Finkelhor, 1986). The increased probability of females to be sexually abused as compared to males, coupled with the startling rate of new HIV infections among minority women in the United States (Centers for Disease Control [CDC], 2004a), has resulted in much of the research on the relationship of child sexual abuse to HIV risk behavior being conducted with women (Arriola, Louden, Doldren, & Fortenberry, 2005). Yet studies that include men with histories of abuse find few gender differences in sexual risk behaviors (Bensley et al., 2000).

PARENTAL MONITORING

The structuring of a child’s environment and the monitoring of his or her activities, whereabouts, and companions by parents or guardians is an effective means of controlling childhood conduct (Dishion & McMahon, 1998). Generally, there is an inverse relationship between levels of parental monitoring and problem behaviors (J. J. Snyder, 2002). Differential levels of parental monitoring may be reflected in the availability of responsible adults as well as the capacity to effectively provide supervision. Family structure transitions, poverty, life stressors, maternal depression (Forgatch & DeGarmo, 2002; C. Johnson, 1996; R. A. Johnson, Su, Gerstein, Shin, & Hoffman, 1995; Patterson & Yoerger, 2002), and parents’AOD use (R. A. Johnson et al., 1995; Patterson et al., 1992) have all been found to interfere with effective monitoring.

Although poverty does not necessarily lead to problem behaviors, low socioeconomic status (SES) may make parenting more challenging. African American families are more likely to be low income and headed by females than other ethnic groups (United States Census Bureau, 2005). In addition, African American youth in disadvantaged communities are particularly at risk for violence exposure and victimization (Cooley-Quille, Boyd, Frantz, & Walsh, 2001; Weist, Acosta, & Youngstrom, 2001) and for engaging in delinquent activities (Gorman-Smith, Tolan, Zelli, & Huesmann, 1996). Yet monitoring by low-income parents is effective in reducing a number of youth problem behaviors (Forehand, Miller, Dutra, & Chance, 1997; Kapungu, Holmbeck, & Paikoff, 2006; Li, Stanton, & Feigelman, 2000; Richards et al., 2004; Schiff & McKay, 2003). A study that included middle-class families found that family SES did not make a difference in the effect of monitoring on outcomes (Bean, Barber, & Crane, 2006). Although the number of available guardians is associated with the level of monitoring (Pettit, Laird, Dodge, Bates, & Criss, 2001), it appears that it is the actual act of monitoring that provides protection from adolescent problem behaviors, not the family structure in which it occurs (Steinberg & Fletcher, 1994) or the type of guardian providing the supervision (Romer et al., 1999).

This study included both sexes and examined gender differences, as patterns of problem behavior and parental monitoring tend to vary by sex. Boys typically exhibit more problem behaviors than girls (Cairns & Cairns, 1994), and adolescent males engage in higher levels of delinquency and physical aggression (Giordano & Cernkovich, 1997). Males also are more likely to engage in sexual risk behaviors (CDC, 2004a; Robertson & Levin, 1999). Although men are more prone to have substance use disorders than women (Kessler et al., 1994), current patterns of AOD use among high school students are similar for males and females (CDC, 2004b). The sex of the child also factors into parental monitoring, with daughters receiving more supervision than sons (Patterson & Stouthamer-Loeber, 1984).

The higher level of monitoring of girls may be a reason for their lower involvement in problem behaviors (Hagan, Simpson, & Gillis, 1979). However, when parental monitoring is in place, it is a protective factor for both boys and girls with regard to delinquency and drug use (Richards et al., 2004). Parental monitoring also appears to be equally effective in reducing first sex and other sexual risk behavior among boys and girls (Romer et al., 1999), although this relationship is not conclusive (Donenberg, Wilson, Emerson, & Bryant, 2002).

To summarize, child maltreatment by caregivers and victimization by other adults are linked to adolescent problem behaviors. It appears that effective parental monitoring can substantially reduce some undesirable behaviors; however, it is not clear whether this relationship is supported when including other family factors (i.e., child maltreatment and antisocial caregivers). Also, gender differences exist in victimization, parental monitoring, and youth problem behaviors and should be examined in models exploring these behaviors. Given that juvenile offenders often demonstrate a number of concurrent problem behaviors, an expanded number of behaviors should be investigated. This research applied the developmental damage model of delinquency, with the inclusion of parental monitoring as a family protective factor, in a predictive model of multiple problem behaviors among male and female incarcerated juveniles. Although we expect parental monitoring to be inversely related to all outcomes, this study is exploratory in nature, and therefore, no hypotheses are tested.

METHOD

PARTICIPANTS

The participants were recruited from a secure detention center located in a southern U.S. city. The facility detains youths from 10 to 17 years of age. Adolescents who had recently been incarcerated (within 3 days of booking) and who were at least 13 years of age were eligible for study participation. Because this facility operates primarily as a short-term holding facility (61% of the juveniles were released within 2 days, and 71% were released within 3 days), researchers were unable to approach all detainees. Of the 816 juveniles who were approached, 763, or 94%, agreed to complete the survey. Intake data showed that there were no significant demographic differences between juveniles booked into the facility and study participants.

The sample was predominantly male (63.0%, n = 479) and of minority ethnicity (89.0%, n = 679 African American; 9.7%, n = 74 White; and 1.3%, n = 10 other race/ethnicity). The average age was 15.1 years (SD = 1.3; range 13 to 18), and the average grade level or last grade completed was Grade 9 (SD = 1.4, range 4 to 12). Reasons for incarceration included violent offense, 26.7% (n = 204); property crime, 22.3% (n = 170); status offense, such as running away from home, 15.7% (n = 120); public disorder, 18.9% (n = 144); AOD-related crime, 7.7% (n = 59); and other reasons, including violation of probation or parole, 8.7% (n = 66).

ASSESSMENT PROCEDURES

The Youth Court Judge granted permission to access youth in detention. Written informed assent was obtained from study participants. Only research personnel were present when youth assent was obtained and during data collection. Participants could refuse to answer any question and to stop responding to the survey at any time. To accommodate low literacy rates that are typical for this population, we used audio computer-administered interview (A-CASI) technology. The A-CASI system displays each question on a computer monitor and a computer-generated voice speaks each question. The participant enters his or her own responses using the keypad. Headphones were used to ensure privacy. Use of this method has been shown to result in higher reporting rates for sensitive sexual and drug-use behavior compared to face-to-face interviews (Des Jarlais et al., 1999). The Mississippi State University Institutional Review Board and the federal Office of Human Research Protections Panel on Prisoners approved the study protocol.

BACKGROUND PREDICTIVE VARIABLES

Single-item demographic variables included gender (0 = female, 1 = male), age in years, and ethnicity (African American, 0 = no, 1 = yes). Other single-item measures include family AOD abuse and family criminal history (0 = no, 1 = yes). The statement “Someone in my family, besides me, had an alcohol or drug problem” assessed family substance abuse. Family criminal history was determined by responses to two questions on whether siblings or parents had ever been arrested or in jail.

INTERVENING VARIABLES

Foster care placement was a single-item measure (0 = no, 1 = yes). Neglect, abandonment, and/or abuse can result in foster home placement. Although foster care placement is not always the result of maltreatment by caregivers, we included it in the model as a mark of serious family dysfunction and disorganization.

The latent variables described below were based on responses to multi-item scales and represent constructs in the model. These constructs included histories of physical and sexual victimization, level of parental monitoring, and various problem behaviors, including common and hard drug use, sexual risk behavior, and delinquent behaviors.

Physical maltreatment was assessed from responses to six items (coefficient α = .66). These items asked whether an adult, including family members, had mistreated them by using fists or kicking, using a whip or a strap, using a club or a stick, or whether they had been assaulted by a weapon, hurt badly enough to require medical treatment, or had been hurt enough to require hospitalization (0 = no, 1 = yes). Based on the size of the sample, and the structure of the hypothesized model, we needed to keep the number of measured indicators to a reasonable amount. Thus, scores for the six physical maltreatment items were randomly combined into parcels of two to obtain three mean indicators labeled Physical Abuse 1, Physical Abuse 2, and Physical Abuse 3. Parceling is an acceptable and normal practice in structural modeling (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002; Yuan, Bentler, & Kano, 1997).

Sexual maltreatment was assessed from responses to eight items that asked about unwanted sex, including showing sex organs, touching sex organs, oral sex, vaginal intercourse, and anal sex (coefficient α = .80; 0 = no, 1 = yes). Four parcels were created from the eight items; they are labeled Sexual Abuse 1, Sexual Abuse 2, Sexual Abuse 3, and Sexual Abuse 4.

Parental monitoring was indicated by responses to five items that questioned how much the participants’ parents know about where they go at night, what they do with their free time, where they go most afternoons after school, how much they know about who their friends are, and whether their parents set curfews for them. Responses ranged from 0 (doesn’t know at all) to 3 (always knows) for the first four questions. The question about curfews ranged from 0 (never) to 4 (always). Coefficient α for these five items was .77.

Outcome Latent Variables

The veracity of self-report data from criminal justice populations is a critical methodological issue (Malow et al., 2006; Richter & Johnson, 2001; Rosay, Najaka, & Herz, 2007). Yet self-reported substance use is reliable and valid when confidentiality of responses is assured (Bailey & Flewelling, 1992; Shillington & Clapp, 2000; G. T. Smith & McCarthy, 1995). Our youth assent document explicitly promised to keep all of their responses confidential.

Common drug use was represented by three self-report measures: frequency of alcohol use, frequency of marijuana use, and the score on the Problem Oriented Screening Instrument for Teenagers (POSIT) Substance Use/Abuse scale (Rahdert, 1991). All alcohol and drug use frequency items were assessed for the 3 months prior to incarceration and were measured on a 5-point, Likert-type scale ranging from 0 = never to 5 = every day. The POSIT is a self-report, multi-problem screening instrument for adolescents 12 to 19 years of age. The Substance Use/Abuse scale consists of 17 questions about problems related to the AOD use. A score was obtained by summing “yes” responses (0 = no, 1 = yes). Coefficient α for these three items was .78.

Hard drug use was represented by use of hallucinogens such as LSD and PCP, cocaine or crack, and other illegal drugs such as uppers, downers, or opiates. They were assessed during the same time period and on the same 5-point, Likert-type scale as alcohol and marijuana frequency. Coefficient α for these three items was .71.

Sexual risk behaviors were indicated by 3-month frequencies in having sex with an injecting drug user, nonmonogamous sex partners, sex under the influence of alcohol, trading sex for money, trading sex for drugs, and a sum score of the number of sex partners in the past 3 months. Coefficient α for these five items was .94.

Delinquency was indicated by (a) the number of school suspensions, (b) gang membership (0 = no, 1 = yes), and (c) the number of prior detentions/incarcerations (capped at eight).

ANALYSES

We used the EQS structural equation modeling (SEM) program (Bentler, 2006), which compares a proposed hypothetical model with a set of actual data. The closeness of the variance–covariance matrix implied by the hypothetical model to the empirical variance–covariance matrix is evaluated with goodness-of-fit indices. Fit was assessed with the comparative fit index (CFI), the maximum likelihood chi-square, and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The CFI indicates the proportion of improvement in the overall fit of the hypothesized model relative to a null model in which all covariances between variables are zero. CFI values of .95 or greater are desirable. The RMSEA is a measure of lack of fit per degrees of freedom, controlling for sample size; values less than .06 indicate a close-fitting model. Because of the multivariate kurtosis in the data set (normalized estimate = 492.60), goodness-of-fit of the model was also evaluated with the adjusted robust comparative fit index (RCFI) based on the Satorra–Bentler χ2 statistic (Bentler & Dudgeon, 1996). The Satorra–Bentler χ2 is preferable when the data are multivariately kurtotic (Bentler & Dudgeon, 1996). The EQS program identified 2 participants who were classified as extreme outliers and were thus deleted from the analyses reported below. The final analyses were based on data from 761 respondents.

An initial confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed with each hypothesized latent construct predicting its proposed manifest indicators. All latent constructs and single-item demographic variables were correlated. This analysis assessed the adequacy of the proposed factor structure (measurement model) and the relationships among the latent and manifest variables. Once the factor structure was confirmed, we tested a predictive path model in which foster care and the maltreatment and monitoring latent variables were positioned as intervening variables between the background predictive variables (demographics, family AOD, and family criminal history) and the problematic behavioral outcomes. In the predictive model, following the procedure for saturated models recommended by MacCallum (1986), all demographic and family characteristic variables predicted the intervening variables and also directly predicted the outcomes. Thus, this model tested the direct effects of the variables on the outcomes and also assessed indirect effects of the variables on the outcomes as mediated through the hypothesized risk and protective factors. Nonsignificant paths and covariances were gradually dropped until only significant paths and covariances remained.

RESULTS

GENDER DIFFERENCES IN VICTIMIZATION AND PROBLEM BEHAVIORS

All variables in the model were examined for gender differences (see Table 1). There were no gender differences for measures of family problems and parental monitoring. Just more than half of both boys (52.8%, n = 230) and girls (55.3%, n = 145) reported that a family member had a history of substance abuse, and more than 60% (n = 479) of juveniles reported that other family members had been arrested or incarcerated. Both boys and girls reported relatively high scores on the summated parental monitoring scale (scores range from 0 to 15), indicating that they perceived themselves to be closely monitored. Also, roughly equal proportions of males (11.5%, n = 55) and females (10.6%, n = 30) had been in foster care.

TABLE 1.

Gender Differences in Predictor, Mediator, and Outcome Variables

| Variable | Male (N = 479) | Female (N = 284) | Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family AOD use, yes | 52.8% | 55.3% | χ2 = 0.44 |

| Family criminal history, yes | 62.5% | 63.7% | χ2 = 0.12 |

| Foster care, yes | 11.5% | 10.6% | χ2 = 0.15 |

| Parental Monitoring Scale, mean score | 9.15 | 9.5 | F = 1.69 |

| Physical maltreatment | |||

| Any reported | 53.9% | 56.0% | χ2 = 0.32 |

| Assaulted with weapon | 31.3% | 25.7% | χ2 = 2.71* |

| Required medical treatment | 24.9% | 25.7% | χ2 = 0.67 |

| Sexual maltreatment | |||

| Any reported | 29.0% | 43.1% | χ2 = 15.68**** |

| Rape (forced vaginal or anal sex) | 13.8% | 20.6% | χ2 = 5.87** |

| Common drug use | |||

| POSIT Substance Abuse Scale, mean score | 2.6 | 1.5 | F = 25.72**** |

| Marijuana use, daily | 21.5% | 7.4% | χ2 = 46.61**** |

| Alcohol use, weekly or more often | 22.0% | 11.7% | χ2 = 18.82*** |

| Hard drug use | |||

| Cocaine/crack, any | 3.3% | 2.1% | χ2 = 4.57 |

| Hallucinogens, any | 2.9% | 2.8% | χ2 = 3.25 |

| Other drugs, any | 2.7% | 0.7% | χ2 = 4.50 |

| Delinquency | |||

| Gang member | 22.3% | 7.7% | χ2 = 26.91**** |

| Number of prior incarcerations | 1.8 | 0.9 | F = 19.96**** |

| Number of school suspensions | 6.2 | 4.15 | F = 34.71**** |

| Sexual risk behaviors | |||

| Sex with IVDU | 0.52 | 0.07 | |

| Sex with nonmonogamous partner | 2.27 | 1.51 | |

| Sex while drunk | 1.32 | 0.46 | F = 1.46 |

| Traded money/favors for sex | 0.34 | 0.10 | F = 1.23 |

| Traded sex for drugs | 0.27 | 0.0 | F = 5.53** |

| Number of partners | 5.52 | 1.74 | F = 0.71 |

Note. AOD = alcohol or drug; POSIT = Problem Oriented Screening Instrument for Teenagers; IVDU = intravenous drug user.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Incidence of physical and sexual abuse was relatively high. Reports of being beaten with a belt, strap, or whip were common (76%, n = 579). About one third (n = 248) of the youth reported other forms of physical abuse, and 29% (n = 223) reported that they were assaulted with a weapon. Overall, 25% (n = 179) of the youth reported seeking some type of medical treatment, with 6% (n = 47) reporting hospitalization. There were no significant gender differences in physical abuse. On the other hand, sexual abuse was more prevalent among the females. However, a substantial percentage of males and females reported forced sex.

Consistent with the literature, boys were more involved in AOD use and delinquency. Approximately twice as many males (22.0%, n = 105) as females (11.7%, n = 33) reported regular alcohol use, and almost 3 times as many males (21.5%, n = 105) as females (7.4%, n = 21) reported daily marijuana use. Boys also scored significantly higher on the POSIT Substance Abuse Scale. Both boys and girls infrequently reported the use of other drugs, and there were no significant gender differences in hard drug use. Males were much more likely than females to report gang membership and reported more prior incarcerations and school suspensions.

Few gender differences in sexual risk behavior were observed; however, males reported more sex partners and more frequent sex under the influence of alcohol. On average, males reported 5.5 partners and females reported 1.7 partners in the 3 months prior to incarceration.

CONFIRMATORY FACTOR ANALYSIS

A preliminary confirmatory factor model estimated the factor structure and relationships among all of the latent variables. Table 2 reports the means, standard deviations, ranges, and factor loadings for each variable. All factor loadings were significant (p < .001). Fit indexes were also quite acceptable: ML χ2 = 887.60, 421 df; CFI = .96, RMSEA = .04. Robust statistics were almost identical to those for the maximum likelihood solution and are not reported. Two supplementary covariances were added to improve the fit. These covariances were between (a) number of sex partners and having sex with a nonmonogamous partner and (b) number of sex partners and having sex while drinking. Table 3 reports the bivariate correlations among constructs of the model without any directionality of influence among them.

TABLE 2.

Summary Statistics and Factor Loadings in Confirmatory Factor Analysis

| Variables | M | SD | Factor Loadinga |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics and family characteristics | |||

| Gender (female = 0, male = 1) | 0.63 | 0.48 | — |

| Age (years) | 15.14 | 1.32 | — |

| African American (0 = no, 1 = yes) | 0.89 | 0.31 | — |

| Family AOD use | 0.53 | 0.48 | — |

| Family criminal history | 0.42 | 0.37 | — |

| Foster care (0 = no, 1 = yes) | 0.11 | 0.31 | — |

| Intervening latent variables | |||

| Physical maltreatment (0–1) | |||

| Physical abuse 1 | 0.54 | 0.36 | .55 |

| Physical abuse 2 | 0.30 | 0.37 | .75 |

| Physical abuse 3 | 0.15 | 0.27 | .53 |

| Sexual maltreatment (0–1) | |||

| Sexual abuse 1 | 0.14 | 0.26 | .75 |

| Sexual abuse 2 | 0.07 | 0.20 | .72 |

| Sexual abuse 3 | 0.11 | 0.25 | .75 |

| Sexual abuse 4 | 0.22 | 0.34 | .75 |

| Parental monitoring (0–3) | |||

| Where at night | 1.86 | 1.09 | .80 |

| Free time | 1.58 | 1.10 | .76 |

| Afternoons | 1.95 | 1.16 | .76 |

| Who their friends are | 1.95 | 1.04 | .52 |

| Curfew (0–4) | 2.94 | 1.32 | .39 |

| Outcome latent variables | |||

| Common drug use | |||

| Alcohol (0–5) | 1.03 | 1.36 | .64 |

| Marijuana (0–5) | 1.75 | 1.97 | .74 |

| POSIT score (0–17) | 2.15 | 2.92 | .83 |

| Hard drug use | |||

| Hallucinogens (0–5) | 0.04 | 0.29 | .79 |

| Cocaine (0–5) | 0.06 | 0.40 | .58 |

| Other illegal drugs (0–5) | 0.04 | 0.37 | .66 |

| Sexual risk behaviorsb | |||

| Sex with IVDU | 0.24 | 0.24 | .96 |

| Nonmonogamous partner | 1.68 | 5.71 | .63 |

| Sex while drunk | 0.95 | 4.88 | .75 |

| Trade sex for money | 0.26 | 3.80 | .98 |

| Trade sex for drugs | 0.17 | 3.78 | .99 |

| Number of partners | 4.01 | 10.67 | .70 |

| Delinquency | |||

| Times suspended | 5.95 | 5.59 | .48 |

| Gang member (0–1) | 0.16 | 0.37 | .54 |

| Detentions/incarcerations | 1.30 | 2.01 | .35 |

Note. AOD = alcohol or drug; POSIT = Problem Oriented Screening Instrument for Teenagers; IVDU = intravenous drug user.

All factor loadings significant, p ≤ .001.

Number of times in the past 3 months.

TABLE 3.

Correlations Among Latent and Measured Variables in the Confirmatory Factor Analysis

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Male | — | ||||||||||||

| 2. Age | .00 | — | |||||||||||

| 3. African American | .08** | −.05 | — | ||||||||||

| 4. Family AOD | −.02 | .08** | −.14**** | — | |||||||||

| 5. Family criminal history | .01 | −.10*** | .00 | .17**** | — | ||||||||

| 6. Physical maltreatment | −.01 | .06 | .03 | .27**** | .21**** | — | |||||||

| 7. Sexual maltreatment | −.24**** | .00 | −.02 | .16**** | .10** | .37**** | — | ||||||

| 8. Parental monitoring | −.05 | −.06 | .06 | −.23**** | −.16**** | −.38**** | −.12*** | — | |||||

| 9. Foster care | .00 | −.01 | −.10*** | .03 | .11*** | .17**** | .15**** | −.12*** | — | ||||

| 10. Common drug use | .24**** | .22**** | −.07 | .30**** | .13**** | .36**** | .14*** | −.43**** | .05 | — | |||

| 11. Hard drug use | .05 | .01 | −.24**** | .07 | .05 | .10** | .13*** | −.16**** | −.02 | .45**** | — | ||

| 12. Sexual risk behavior | .04 | −.06 | .02 | .04 | .01 | .07 | .16**** | −.08* | −.01 | .18**** | .78**** | — | |

| 13. Delinquency | .47**** | .02 | .24**** | .15*** | .18**** | .36**** | .03 | −.34**** | .14*** | .74**** | .11 | .10 | — |

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Focusing on the most substantial correlations, males reported less sexual maltreatment, more common drug use, and more delinquency. Greater age was associated with more common drug use. African American youth reported less hard drug use and more delinquency. Family AOD was associated positively with family criminal history, more physical and sexual maltreatment, and adolescent drug use and delinquency, and it was negatively associated with parental monitoring. Physical maltreatment was associated with sexual maltreatment, more likelihood of being in foster care, common drug use, and delinquency, and it was negatively associated with parental monitoring. Sexual maltreatment was most highly associated with prior foster care and sexual risk behavior. Greater parental monitoring was associated negatively with all of the dysfunctional outcomes. Common drug use was highly associated with hard drug use and delinquency, and sexual risk behavior was most highly associated with hard drug use.

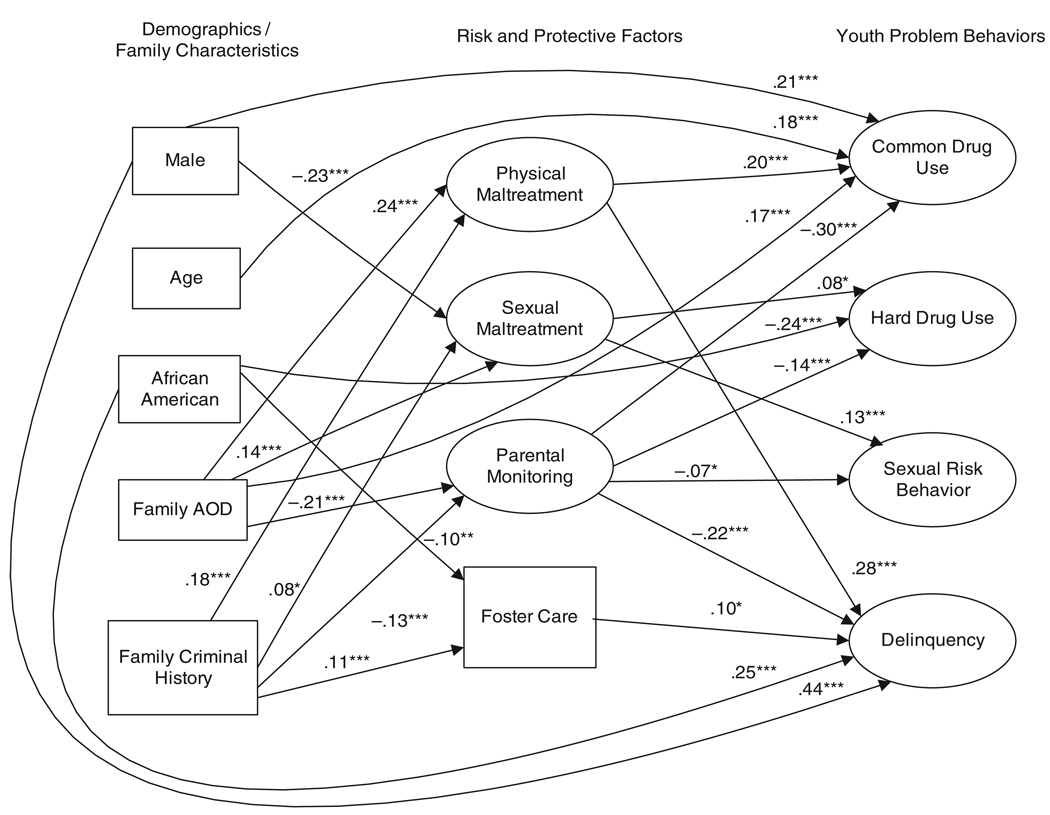

PATH MODEL

The final predictive path model is presented in Figure 1. As described above, nonsignificant paths and covariances were gradually dropped until only significant ones remained. Measured variables are in rectangles, and the multiple indicator latent variables are in ovals. Arrows indicate the directionality of influence of the model components. Fit indexes were quite acceptable: ML χ2 = 953.49, 464 df; CFI = .96, RMSEA = .04. Again, robust statistics were similar to the maximum likelihood goodness-of-fit statistics. Family AOD and a family criminal history significantly predicted physical maltreatment. Female gender, family AOD, and a family criminal history predicted sexual maltreatment. Family AOD and a family criminal history negatively predicted greater parental monitoring. Foster care was less likely among African Americans and more likely among families with a criminal history. Common drug use was predicted by male gender, greater age, more physical maltreatment, more family AOD, and less parental monitoring. Hard drug use was predicted by sexual maltreatment and was negatively predicted by parental monitoring; also, it was less common among African Americans. Sexual risk behavior was predicted by sexual maltreatment and less parental monitoring. Delinquency was predicted by physical maltreatment, less parental monitoring, foster care, ethnicity, and being male.

Figure 1. Final structural path model.

Note. All estimated parameters are standardized. The large circles designate latent variables; the rectangles represent measured variables. One-headed arrows represent regression paths; for readability correlations among predictors are not depicted.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Because this was a mediated model, we also examined the indirect effects of the intervening variables. Both family AOD and family criminal history had significant indirect effects on common drug use ( p < .001) mediated through physical maltreatment and parental monitoring. Family AOD ( p < .001) and family criminal history ( p < .01) also had significant effects on hard drug use, mediated through parental monitoring. Sexual risk behavior was indirectly affected by female gender ( p < .01) mediated through sexual maltreatment and was also indirectly affected by family criminal history and family AOD (p < .01) mediated by both monitoring and sexual maltreatment. Delinquency was significantly impacted indirectly by family AOD and family criminal history (p < .001) mediated by physical maltreatment and monitoring.

DISCUSSION

Ours was the first study to include both victimization by adults and parental monitoring in a single model of adolescent problem behavior. Our results integrate the developmental damage model (Dembo et al., 1992) with the model of Patterson et al. (1992) that links parental substance abuse with less parental monitoring. We focused on detained juveniles because youth in the juvenile justice system are more often victims of maltreatment and crime (Dembo et al., 1993). A comparison of our participants with high school students in the same state (CDC, 2004b) reveals that our participants were much more likely to be victims of forced sexual intercourse (8.4% high school students versus 16.3% juveniles in detention, χ2 = 62.1, p < .001). A substantial percentage of our participants reported physical and sexual victimization, and the rates of maltreatment exceeded estimated rates for the general population. Estimates of child abuse for the general population are 5% to 8% of males and 12% to 17% of females (Gorey & Leslie, 1997). Our findings also support previous research linking child abuse with high-risk sexual behavior, AOD abuse, and antisocial behavior.

Juvenile offenders are frequently the products of dysfunctional families (Acoca & Dedel, 1998). More than half of the respondents reported that family members had an AOD abuse problem, and almost two thirds had a sibling or parent with a criminal history. These family problems are risk factors associated with multiple problem behaviors of youth. These findings show that family AOD history and family criminal history were positively associated with physical and sexual maltreatment. Also, family criminal history was related to foster care placement. Research shows that adult prisoners reporting physical and sexual abuse before the age of 18 come from family backgrounds similar to those of the youth in our study. Prisoners reported higher levels of abuse if they grew up in foster care, if their parents were heavy users of alcohol or drugs, or if a family member had been incarcerated (Harlow, 1999).

Our results extend the developmental damage model (Dembo et al., 1992) from delinquency and drug use among male juvenile offenders to both males and females and to sexual risk behaviors. Our findings also support research linking parental substance abuse with less parental monitoring (R. A. Johnson et al., 1995). Although the disruptive effects of substance abuse in the family on parental monitoring were stronger in our sample, family criminal history inhibited parental monitoring as well.

Our study also supports research demonstrating the effectiveness of parental monitoring in preventing youth problem behaviors. However, ours was the first study to examine the effects of parental monitoring among juveniles in detention. Our findings suggest that even among youth with a history of behavioral problems, more parental monitoring can reduce poor outcomes. Greater parental monitoring had the most pervasive effect on all of the problem behavior outcomes. Given evidence that monitoring reduces adolescent problem behaviors regardless of the type of guardian (Romer et al., 1999), extended family or mentors could provide monitoring in single-parent homes and in families in which parental ability to monitor is impaired.

Research on the development of youth problem behaviors has clear implications for prevention programs. Problematic behaviors could be prevented by increasing therapeutic services and by providing training on parental monitoring, parent–youth communication, and other family management practices to families with histories of abuse and neglect allegations (Weibush, Freitag, & Baird, 2001). A family risk assessment can identify service needs. When appropriate services are delivered to these families, they can lower rates of subsequent maltreatment (Baird, Wagner, Caskey, & Neuenfeldt, 1995).

An assessment of family problems and family-focused interventions also has the potential to benefit youth involved in the juvenile justice system. Patterson’s version of parent training has been successful in reducing recidivism with repeat offending delinquent males (Marlowe, Reid, Patterson, & Weinrott, 1986, cited in Patterson & Yoerger, 2002). In addition to training parents to set rules and to monitor and discipline their children, family problems such as parental depression were also addressed. Behavioral-systems family therapy, which focuses on the entire family and includes behavioral skills training, has been found to reduce recidivism among delinquents (Gordon, Arbuthnot, Gustafson, & McGreen, 1988). These earlier interventions targeted primarily White male samples and those with juvenile justice involvement. More recently, a number of effective interventions have been developed for targeted family needs and for different family types, such as foster families, ethnic families, and rural families (Kumpfer & Alvarado, 1998). The most effective approaches impact a broad range of family risk and protective factors by combining social and life skills training for youth with parent skills training programs to improve supervision and nurturance (Stanton et al., 2004).

Our study is not without limitations. First, the majority (89%) of our sample consisted of African American youth. Although our sample reflected the racial makeup of the study site, the proportion of African American youth incarcerated there is higher than the proportion detained (45% in 1997) in facilities across the United States (H. N. Snyder & Sickmund, 1999). We, therefore, cannot generalize our findings to all incarcerated youth, although we did include African American ethnicity as a correlate and a predictor. Second, all measures, except the prior number of incarcerations, are based on self-report. Despite efforts to assure privacy and the use of A-CASI data collection, it is possible that AOD use and sexual risk behaviors were underreported. Even so, the risk behavior reported by these juveniles exceeds that of high school students participating in the Youth Risk Behaviors Surveillance study (CDC, 2004b). In addition, the collection of bio-markers for drug use and STD infection appears to corroborate youths’ reports (Robertson et al., 2005). Third, we collected limited information on victimization by adults. We asked participants whether various forms of physical and sexual abuse occurred and their age when the abuse first happened. We did not obtain information on how many times maltreatment occurred, nor did we collect information about the perpetrator. Furthermore, we do not know how many cases of abuse were investigated and substantiated by authorities. Although the rates of reported victimization seem high, adult prisoners report similar rates of physical and sexual abuse that occurred when they were minors (Harlow, 1999). Finally, we were not able to fully apply the developmental models on which this research is based. Our data were cross-sectional, and we did not collect information on when problem behaviors began. We can only speculate that the maltreatment occurred prior to the problem behavior. In addition, the influence of deviant peers is a large component of Patterson’s model. We did not assess problem behaviors among participants’ friends, and thus peer influences were not included in the model. Testing of more complex theoretical models is certainly warranted.

Despite these limitations, the study illustrates the roles of a dysfunctional family environment and child maltreatment as risk factors for adolescent problem behaviors. Our findings also demonstrate the protective role of parental monitoring among youth involved in the juvenile justice system. Greater recognition of the mediating effects of child victimization and parental monitoring should spur juvenile justice and child welfare program planners to initiate comprehensive prevention and intervention efforts targeted at enhancing effective parenting practices as well as reducing risk.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA 14695 to Dr. Robertson and DA 01070-34 to D r. Stein). The authors thank Gisele Pham, Alyson Herbert, and Rebecca Harvey for their secretarial and editing contributions.

Biographies

Angela Robertson, PhD, is an Associate Research Professor at the Social Science Research Center and the Coordinator of Research and Development for the Mississippi Alcohol Safety Education Program, a statewide intervention for first-time offenders convicted of impaired driving. Dr. Robertson conducts research on issues of deviance and health, i.e., substance abuse and addiction, mental disorders, and STD/HIV risk behavior among criminal justice populations. Current research includes a longitudinal analysis of STD/HIV exposure and prevention among female adolescent offenders and a study of HIV testing and prevention among clients of publicly funded alcohol and drug treatment programs.

Connie Baird-Thomas is the Associate Director of the Social Science Center for Policy Studies and Director of the Mississippi Health Policy Research Center. Her primary research interests include at-risk youth, STD/HIV prevention, health disparities and program evaluation. She is currently involved in assessing an STD/HIV risk intervention for adolescent female offenders and is leading the evaluation of a statewide effort to reduce health disparities among minorities.

Judith A. Stein, PhD, is the Associate Director of the UCLA/NIDA Center for Collaborative Research on Drug Abuse which is housed in the UCLA Department of Psychology. Her specialty is measurement and psychometrics with an emphasis on structural equation modeling. She participates in collaborative studies that involve research among disadvantaged at-risk populations.

Footnotes

Contributor Information

Angela A. Robertson, Mississippi State University

Connie Baird-Thomas, Mississippi State University.

Judith A. Stein, University of California, Los Angeles

REFERENCES

- Acoca L, Dedel K. No place to hide: Understanding and meeting the needs of girls in the California juvenile justice system. San Francisco, CA: National Council on Crime and Delinquency; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Arriola KRJ, Louden T, Doldren MA, Fortenberry RM. A meta-analysis of the relationship of child sexual abuse to HIV risk behavior among women. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2005;29:725–746. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey SL, Flewelling RL. The characterization of inconsistencies in self-reports of alcohol and marijuana use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1992;53:636. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1992.53.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird SC, Wagner D, Caskey R, Neuenfeldt D. Michigan Department of Social Services Structured Decision Making System: An evaluation of its impact on Child Protection Services. Madison, WI: National Council on Crime and Delinquency, Children’s Research Center; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bean RA, Barber BK, Crane RD. Parental support, behavioral control, and psychological control among African American youth. Journal of Family Issues. 2006;27:1335–1355. [Google Scholar]

- Bensley LS, Van Eenwyk J, Simmons KW. Self-reported childhood sexual and physical abuse and adult HIV-risk behaviors and heavy drinking. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2000;18:151–158. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00084-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. EQS 6 structural equations program manual. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Dudgeon P. Covariance structure analysis: Statistical practice, theory, and directions. Annual Review of Psychology. 1996;47:563. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.47.1.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne A, Finkelhor D. Impact of child sexual abuse: A review of research. Psychological Bulletin. 1986;99:66–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns RB, Cairns B. Lifelines and risks: Pathways of youth in our times. Cambridge, UK: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- CDC. HIV/AIDS among U.S. women: Minority and young women at continuing risk. 2004a Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pubs/facts/women.htm.

- CDC. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2003. 2004b Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/index.htm. [PubMed]

- Cocozza JJ. Responding to the mental health needs of youth in the juvenile justice system. Seattle, WA: National Coalition for the Mentally Ill in the Criminal Justice System; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M, Deamant C, Barkan S, Richardson J, Young M, Homan S, et al. Domestic violence and childhood sexual abuse in sexual abuse in HIV-infected women and women at risk for HIV. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:560–565. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.4.560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley-Quille M, Boyd RC, Frantz E, Walsh J. Emotional and behavioral impact of exposure to community violence in inner-city adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30(2):199–206. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3002_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembo R, Williams L, Schmeider J, Christensen C. Recidivism in a cohort or juvenile detainees: A 3 1/2-year follow-up. International Journal of the Addictions. 1993;28:631–658. doi: 10.3109/10826089309039653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembo R, Williams L, Wothke W, Schmeidler J, Brown CH. The role of family factors, physical abuse, and sexual victimization experiences in high-risk youths’ alcohol and other drug use and delinquency: A longitudinal model. Violence and Victims. 1992;7:245–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Paone D, Milliken J, Turner CF, Miller H, Gribble J, et al. Audio-computer assessment interviewing to measure risk behavior for HIV among injecting drug users: A quasi-randomized trial. Lancet. 1999;353:1657–1661. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)07026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McMahon RJ. Parental monitoring and the prevention of child and adolescent problem behavior: A conceptual and empirical formulation. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1998;1:61–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1021800432380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donenberg GR, Wilson HW, Emerson E, Bryant FB. Holding the line with a watchful eye: The impact of perceived parental permissiveness and parental monitoring on risky sexual behavior among adolescents in psychiatric care. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2002;14:138. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.2.138.23899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT. Childhood sexual abuse, adolescent sexual behaviors, and sexual revictimization. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1997;21:789–803. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forehand R, Miller KS, Dutra R, Chance MW. Role of parenting in adolescent deviant behavior: Replication across and within two ethnic groups. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:1036–1041. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.6.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, DeGarmo DS. Extending and testing the social interaction learning model with divorce samples. In: Reid JB, Patterson GR, Snyder JJ, editors. Antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: A developmental analysis and model for intervention. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 235–256. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano PC, Cernkovich SA. Handbook of antisocial behavior. In: Stoff DM, Breiling J, Maser JD, editors. Gender and antisocial behavior. New York: John Wiley; 1997. pp. 496–510. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon DA, Arbuthnot J, Gustafson KE, McGreen P. Home-based behavioral-systems family therapy with disadvantaged juvenile delinquents. The American Journal of Family Therapy. 1988;16(3):243–255. [Google Scholar]

- Gorey KM, Leslie DR. The prevalence of child sexual abuse: Integrative review adjustment for potential response and measurement biases. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1997;21:391–398. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(96)00180-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Zelli A, Huesmann LR. The relation of family functioning to violence among inner-city minority youths. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10:115–129. [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Stein JA, Greenwell L. Associations among childhood trauma, adolescent problem behaviors, and adverse adult outcomes in substance-abusing women offenders. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:43–53. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan J, Simpson JH, Gillis AR. The sexual stratification of social control: A gender-based perspective on crime and delinquency. British Journal of Sociology. 1979;30:25–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow CW. Prior abuse reported by inmates and probationers. 1999 Retrieved from http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/

- Huizinga D, Weiher AW, Menard S, Espiritu R, Ebensen F. Some not so boring findings from the Denver Youth Survey; Paper presented at the American Society of Criminology meeting; Washington, DC. 1998. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen LW, Harlow LL. Childhood sexual abuse linked with adult substance use, victimization, and AIDS risk. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1996;8:44–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C. Addressing parent cognition in interventions with families of disruptive children. In: Dobson KS, Craig KD, editors. Advances in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. pp. 193–209. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RA, Su SS, Gerstein DR, Shin H, Hoffman JP. Parental influences on deviant behavior in early adolescence: A logistic response analysis of age- and gender-differential effects. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 1995;11:167–193. [Google Scholar]

- Kapungu CT, Holmbeck GN, Paikoff RL. Longitudinal association between parenting practices and early sexual risk behaviors among urban African American adolescents: The moderating role of gender. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35:783–794. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer KL, Alvarado R. Effective family strengthening interventions. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Laird RD, Pettit GS, Dodge KA, Bates JE. Change in parents’ monitoring knowledge: Links with parenting, relationship quality, adolescent beliefs, and antisocial behavior. Social Development. 2003;12:401–419. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Stanton B, Feigelman S. Impact of perceived parental monitoring on adolescent risk behavior over 4 years. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;27:49–56. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Cunningham WA, Shahar G, Widaman KF. To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:151–173. [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum R. Specification searches in covariance structure modeling. Psychological Bulletin. 1986;100:107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Malow RM, Rosenberg R, Donenberg G, Devieux JG. Interventions and patterns or risk in adolescent HIV/ AIDS prevention. American Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2006;2:80–89. doi: 10.3844/ajidsp.2006.80.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield MG, Widom CS. The cycle of violence. Revisited 6 years later. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 1996;150(4):390–395. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170290056009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Reid JB, Dishion T. Antisocial boys: A social interactional approach. Eugene, OR: Castalia; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Stouthamer-Loeber M. The correlation of family management practices and delinquency. Child Development. 1984;55:1299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Yoerger K. A developmental model for early- and late-onset delinquency. In: Reid JB, Patterson GR, Snyder JJ, editors. Antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: A developmental analysis and model for intervention. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 147–172. [Google Scholar]

- Perez DM. The relationship between physical abuse, sexual victimization, and adolescent illicit drug use. Journal of Drug Issues. 2000;30:641–662. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit GS, Laird RD, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Criss MM. Antecedents and behavior-problem outcomes of parental monitoring and psychological control in early adolescence. Child Development. 2001;72:583. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahdert ER. The Adolescent Assessment-Referral System. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1991. (DHHS Publication No. [ADM] 91–7135) [Google Scholar]

- Richards MH, Miller BV, O’Donnell PC, Wasserman MS, Colder C. Parental monitoring mediates the effects of age and sex on problem behaviors among African American urban young adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2004;33:221–233. [Google Scholar]

- Richter L, Johnson PB. Current methods of assessing substance use: A review of strengths, problems, and developments. Journal of Drug Issues. 2001;31:809–832. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson AA, Husain J. Prevalence of mental illness and substance abuse disorders among incarcerated juvenile offenders. Mississippi State: Mississippi State University, Social Science Research Center; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson AA, Levin ML. AIDS knowledge, condom attitudes, and risk-taking sexual behavior of substance-abusing juvenile offenders on probation or parole. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1999;11:450–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson AA, Thomas CB, St. Lawrence JS, Pack R. Predictors of infection with chlamydia or gonorrhea in incarcerated adolescents. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2005;32:115–122. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000151419.11934.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romer D, Stanton B, Galbraith J, Feigelman S, Black MM, Li X. Parental influence on adolescent sexual behavior in high-poverty settings. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 1999;153(10):1055–1062. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.10.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosay A, Najaka S, Herz D. Differences in the validity of self-reported drug use across five factors: Gender, race, age, type of drug, and offense seriousness. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2007;23:41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Schiff M, McKay MM. Urban youth disruptive behavioral difficulties: exploring association with parenting and gender. Family Process. 2003;42:517–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2003.00517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shillington AM, Clapp JD. Self-report stability of adolescent substance use: Are there differences for gender, ethnicity and age? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;60:19–27. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00137-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C. The link between childhood maltreatment and teenage pregnancy. Social Work Research. 1996;20:131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, McCarthy DM. Self-reported drinking and alcohol-related problems among early adolescents: Dimensionality and validity over 24 months. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1995;56(4):383. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder HN, Sickmund M. Juvenile offenders and victims: 1999 national report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder JJ. Reinforcement and coercion mechanisms in the development of antisocial behavior: Peer relationships. In: Reid JB, Patterson GR, Snyder JJ, editors. Antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: A developmental analysis and model for intervention. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 101–122. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton B, Cole M, Galbraith J, Li X, Pendleton S, Cottrel L, et al. Randomized trial of a parent intervention: Parents can make a difference in long-term adolescent risk behaviors, perceptions, and knowledge. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2004;158:947–955. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.10.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Fletcher A. Parental monitoring and peer influences on adolescent substance use. Pediatrics. 1994;93:1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stouthamer-Loeber M, Loeber R, Homish DL, Wei E. Maltreatment of boys and the development of disruptive and delinquent behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:941–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplin LA, Elkington KS, McClelland GM, Abram KM, Mericle AA, Washburn JJ. Major mental disorders, substance use disorders, comorbidity, and HIV-AIDS risk behaviors in juvenile detainees. Pediatric Services. 2005;56(7):823–828. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.7.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. Statistical Abstract of the United States. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Weibush R, Freitag R, Baird C. Preventing delinquency through improved child protection services. 2001 Retrieved from http://www.ncjrs.org/pdffiles1/ojjdp/187759.pdf.

- Weist MD, Acosta OM, Youngstrom EA. Predictors of violence exposure among inner-city youth. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:187–198. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3002_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan K-H, Bentler PM, Kano Y. On averaging variables in a confirmatory factor analysis model. Behaviormetrika. 1997;24:71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Zierler S, Feingold L, Laufer D, Velentgas P, Kantrowitz-Gordon I, Mayer K. Adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse and subsequent risk of HIV infection. Journal of American Public Health. 1991;81(5):572–575. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.5.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]