Abstract

Poxvirus virions, whose outer membrane surrounds two lateral bodies and a core, contain at least 70 different proteins. The F18 phosphoprotein is one of the most abundant core components and is essential for the assembly of mature virions. We report here the results of a structure/function analysis in which the role of conserved cysteine residues, clusters of charged amino acids and clusters of hydrophobic/aromatic amino acids have been assessed. Taking advantage of a recombinant virus in which F18 expression is IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) dependent, we developed a transient complementation assay to evaluate the ability of mutant alleles of F18 to support virion morphogenesis and/or to restore the production of infectious virus. We have also examined protein-protein interactions, comparing the ability of mutant and WT F18 proteins to interact with WT F18 and to interact with the viral A30 protein, another essential core component. We show that F18 associates with an A30-containing multiprotein complex in vivo in a manner that depends upon clusters of hydrophobic/aromatic residues in the N′ terminus of the F18 protein but that it is not required for the assembly of this complex. Finally, we confirmed that two PSSP motifs within F18 are the sites of phosphorylation by cellular proline-directed kinases in vitro and in vivo. Mutation of both of these phosphorylation sites has no apparent impact on virion morphogenesis but leads to the assembly of virions with significantly reduced infectivity.

Vaccinia virus is the prototypic poxvirus and was the strain used in the successful vaccination campaign that led to the eradication of smallpox as a natural pathogen of humans. Poxvirus virions are large and structurally complex. Mature virions are approximately 350 by 250 nm in size and contain at least 70 different proteins, a lipid bilayer, and a double-stranded DNA genome of approximately 192 kb (4). Virion morphogenesis is quite unusual and occurs solely within the cytoplasm of infected cells. Initially, proteins destined for encapsidation within the virion accumulate in electron-dense zones known as factories or virosomes. At the periphery of these virosomes, membrane crescents appear. These crescents are composed of a single lipid bilayer that contains numerous integral membrane proteins (4); an external scaffold composed of the D13 protein supports the crescents as they enlarge and determines the size and curvature of the membrane (7, 29). As the membrane grows it becomes the delimiting boundary of the oval immature form of the virion (immature virion [IV]); the genome is encapsidated into the IV, most probably before the membrane seals. The D13 scaffold is then released from the IV, which mature into infectious, mature virions (MV). MV are brick-shaped and contain a dumbbell-shaped core; two lateral bodies of unknown function lie in the concavities of the core (4).

The outer boundary of the core is a proteinaceous shell which surrounds the genome, as well as the complete machinery for early transcription (4, 18). The proteins that comprise the core, as well as those found within the membrane, have been identified by a variety of biochemical, immunological, and mass spectrometric approaches (3, 21, 36). The function of many of these proteins has also been elucidated through the study of conditionally lethal viruses such as temperature-sensitive mutants or inducible recombinants in which the expression of individual gene products is IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) or TET dependent (6, 12, 14).

One of the very first core proteins shown to be essential for the production of infectious virions is an 11-kDa protein referred to in the literature as p11, F18, or F17 (8-10, 20, 37). This protein was originally annotated as the product of the F18R open reading frame (37), but in fact this reflected an annotation error; there are only 17 open reading frames in the HindIII F fragment. In this report, we will adhere to the original nomenclature and refer to the protein as F18 to provide continuity with most of the earlier literature. The abundant F18 protein is expressed at late times of infection; early reports indicated that ∼27,000 copies of the protein are encapsidated per virion (25). The protein is encoded by all known poxviruses but has no recognizable homologs outside of the poxvirus family. The amino acid sequence of F18 gives no hint to its function; early biochemical studies suggested that F18 could multimerize and was associated with a weak affinity for DNA (10). The protein is highly basic (predicted pI of 9.37) and is known to undergo phosphorylation on two serine residues (9, 10).

In an initial study (37) regarding the general utility of inducer-dependent viruses, repression of the F18 protein was shown to compromise virion assembly. The proteolytic processing of core proteins was found to be incomplete, and immature particles with aberrant internal structures were seen. No mature virions assembled in the absence of F18. The phenotype of the IPTG-inducible recombinant makes it clear that F18 is dispensable for the formation of membrane crescents but essential for the proper filling of immature virions and their conversion to mature virions. Consistent with such a role, we have previously utilized immunoelectron microscopy to localize F18 throughout the lumen of immature virions and to a ring corresponding to the core boundary in mature virions (32). Because no temperature-sensitive mutants with lesions that affect F18 have been identified, we have gained no further insight into how F18 functions or into which residues/domains contribute to its role in virion assembly. We therefore undertook a thorough structure/function analysis of F18 in order to better understand its contributions to poxvirus morphogenesis and maturation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Restriction endonucleases, T4 DNA ligase, calf intestinal phosphatase, pancreatic RNase, and Taq polymerase were purchased from Roche Applied Sciences (Indianapolis, IN) and were used according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA oligonucleotides were synthesized by IDT (Coralville, IA). Lipofectamine 2000, protein molecular-weight markers, and DNA molecular-weight standards were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). 14C-labeled protein molecular-weight standards were obtained from Amersham/GE Life Sciences (Piscataway, NJ). 32PPi and [35S]methionine were purchased from Perkin-Elmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Inc. (Boston, MA). Protein A-Sepharose, rifampin, and α-FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Enhanced chemiluminescent substrate was acquired from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) lacking phosphate or methionine was purchased from MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH). Active recombinant CDK1, ERK1, and JNK/SAPK1 kinases were purchased from Upstate (Lake Placid, NY). The following plasmids were used for expression studies described in the present study: pJS4 (kindly provided by B. Moss, National Institutes of Health), pJS4-3×FLAG (19), pTM1-3×FLAG (19), and pET16b (Novagen, Madison, WI).

Cells and viruses.

Monolayer cultures of African green monkey kidney BSC40 cells were maintained in DMEM containing 5% fetal calf serum (Invitrogen). Wild-type (WT) vaccinia virus (WR strain) and the vindF18-inducible virus (vRO11K; kindly provided by B. Moss, National Institutes of Health [National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease]) (37) were amplified in BSC40 cells. Viral stocks were prepared from cytoplasmic lysates of infected cells by ultracentrifugation through 36% sucrose and, when indicated, were further purified by banding on 25 to 40% sucrose gradients (15). During permissive infections with vindF18, IPTG was included in the culture medium at a final concentration of 5 mM. When indicated, rifampin was added to a final concentration of 100 μg/ml.

Construction of F18 expression constructs encoding WT or mutant alleles of F18.

The primers used to amplify WT, epitope-tagged, and mutant alleles of F18 used in the generation of plasmids described in the present study are shown in Table 1 . For each construct in Table 1, the outside primers (5′ primer, O1; 3′ primer, O4) insert an NdeI site (italic) that overlaps the translational start site (italic and underlined) of F18 and a BamHI site (boldfaced) downstream of the F18 termination codon (underlined), respectively. The mutant alleles described in the text were generated by overlap PCR. For each allele, primers labeled B and C were used to introduce the internal mutations. In the first round of PCR, two reactions utilizing primers O1 plus B and O4 plus C were performed to generate fragments of the F18 gene that contained the desired mutations and overlapped by 24 bp. These PCR products were then mixed and used as the template for a second round of PCR using primers O1 and O4. The final PCR products were purified on glass beads (34), digested with the relevant restriction enzymes, and ligated to pJS4 (2) or pJS43×-FLAG plasmid DNA and that had been previously digested with NdeI and BamHI and treated with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase. These plasmids place the F18 alleles under the regulation of a strong, synthetic early/late viral promoter. Plasmids were purified from Escherichia coli transformants and were verified by restriction enzyme digestion and DNA sequencing.

TABLE 1.

Primers utilized to generate the mutant alleles of F18 described in this studya

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| O1 | CCATCGATCATATGAATTCTCATTTTGCA |

| O4 | GCGGATCCTTAGTTCAAAAGTCTAG |

| S53A-B | CGCGGGTGCTGAGGGTTTATCTAC |

| S53A-C | AACCCTCAGCACCCGCGTGTGAGAGA |

| S62A-B | GGACGGGGCCGAAGGTCTTCTCTC |

| S62A-C | GACCTTCGGCCCCGTCCAGATGCGAG |

| S53E-B | CGCGGGTTCTGAGGGTTTATC |

| S53E-C | AACCCTCAGAACCCGCGTGTG |

| S62E-B | GGACGGTTCCGAAGGTCTTCTC |

| S62E-C | GACCTTCGGAACCGTCCAGATGCG |

| C30S-B | AACATCGGATACTTTAACGGC |

| C30S-C | CCGTTAAAGTATCCGATGTTAGAACTGTAG |

| C37S-B | CTTCCTTCGGATTCTACAGTT |

| C37S-C | GTAGAATCCGAAGGAAGTAAAGC |

| C44S-B | GAGTACGGAGGAAGCTTTACTTCC |

| C44S-C | GCTTCCTCCGTACTCAAAGTAG |

| C56S-B | CTTCTCTCAGACGCGGGTGATGAGGG |

| C56S-C | CCCGCGTCTGAGAGAAGACC |

| FYI-AAA-B | CTTTGGTATTGGCTGCTGCCGGAGTATGAGCAGATG |

| FYI-AAA-C | CATACTCCGGCAGCAGCCAATACCAAAGAAGGAAG |

| KEGR-AAGA-B | CCAGATATGCTCCTGCTGCGGTATTGATATAAAACG |

| KEGR-AAGA-C | CAATACCGCAGAAGGAGCATATCTGGTTCTAAAAGC |

| YLVL-AAAA-B | CGGCTTTTGCGGCCGCGGCTCTTCCTTCTTTGGTATTG |

| YLVL-AAAA-C | GAAGGAAGAGCCGCGGCCGCAAAAGCCGTTAAAGTATG |

| KAVKD31-AAAAQ31-B | GCATACTGCGGCGGCTGCTAGAACCAGATATCTTC |

| KAVKD31-AAAAQ31-C | GGTTCTAGCAGCCGCCGCAGTATGCGATGTTAGAAC |

| DVR-AVA-B | CTACAGTTGCAACGGCGCATACTTTAACGGC |

| DVR-AVA-C | GTATGCGCCGTTGCAACTGTAGAATGCGAA |

| E36-A-B | CTTCGCATGCTACAGTTCTAACATCG |

| E36-A-C | GAACTGTAGCATGCGAAGG |

| CVL-AAA-B | CTACTTTGGCTGCGGCGGAAGCTTTACTTCCTTCG |

| CVL-AAA-C | GCTTCCGCCGCAGCCAAAGTAGATAAACCCTC |

| KVDK-AVAA-B | GATGAGGGTGCAGCTACTGCGAGTACGCAGGAA |

| KVDK-AVAA-C | GTACTCGCAGTAGCTGCACCCTCATCACCCGCG |

| ERR-AAA-B | CGAAGGTGCTGCAGCACACGCGGGTGATGAGG |

| ERR-AAA-C | GCGTGTGCTGCAGCACCTTCGTCCCCGTCC |

| ER-AA-B | GTTATTCATTGCTGCGCATCTGGACGGGGA |

| ER-AA-C | GATGCGCAGCAATGAATAACCCTG |

| VPFM-AAAA-B | CCGTCCTCGCTGCCGCGGCTTGTTTTCCAGGGTTATTC |

| VPFM-AAAA-C | GGAAAACAAGCCGCGGCAGCGAGGACGGACATGCTAC |

| R80-A-B | GTCCGTCGCCATAAACGGGACTTG |

| R80-A-C | CGTTTATGGCGACGGACATGCTACAAAATATG |

| Stop 70-B | GGGTTTTACATTCTCTCGCATCTG |

| Stop 70-C | GAATGTAAAACCCTGGAAAACAAG |

| Stop 82-B | GTAGCATTTACGTCCTCATAAACG |

| Stop 82-C | GGACGTAAATGCTACAAAATATG |

Primer O1 inserts an NdeI site (italic) that overlaps the translational start site (italic and underlined) of F18. Primer O4 inserts a BamHI site (in bold) at the terminus, immediately downstream of the translational stop site (underlined) of the F18 open reading frame. The B and C primers were used to introduce the various mutations. The intact alleles were generated by two sequential rounds of PCR, as described in Materials and Methods and ligated into plasmids under the regulation of a strong, synthetic early late viral promoter (2).

Bacterial expression of F18. (i) Preparation of bacterial expression plasmids.

pJS43×-FLAG F18 constructs were digested with NdeI and BamHI to liberate the F18 insert, which was then ligated to pET16b-DNA that had been digested with the same enzymes and treated with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase. Plasmids were verified by restriction enzyme digestion and DNA sequencing.

(ii) Expression and purification of recombinant F18.

pET16b-F18 constructs were maintained in E. coli strain BL21DE3. Cultures were grown to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5 at 37°C, induced by the addition of IPTG to a final concentration of 1 mM, and incubated at 30°C for 4 h with aeration. Clarified lysates were prepared and applied to Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (Qiagen) resin, which was washed with increasing concentrations of imidazole; N′-His-F18 was eluted with 250 mM imidazole. Protein concentrations were determined by using the Bradford method with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Transient complementation assay.

Dishes (35-mm diameter) of confluent BSC40 cells were infected with vindF18 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5. The inoculum was removed, and fresh medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) was applied after a 30-min adsorption period in the presence or absence of IPTG (5 mM). At 3 h postinfection (hpi), 3.5 μg of supercoiled DNA (pJS4-F18 constructs) was introduced by transfection using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent. Cells were harvested at 24 hpi. Viral yields were determined by serial titration on monolayers of BSC40 cells at 37°C in the presence of 5 mM IPTG. At 48 hpi, the dishes were stained with crystal violet, and the plaques were enumerated. The lysates were also resolved by SDS-17% PAGE and subjected to immunoblot analysis with α-F18 serum (15) to assess the expression of F18. All experiments were performed in duplicate, and the results were averaged.

Immunoprecipitation of lysates prepared from metabolically labeled cultures. (i) Metabolic labeling with [35S]methionine.

Monolayers of BSC40 cells were infected at an MOI of 5 with vindF18 virus (with or without IPTG [vindF18+IPTG or vindF18−IPTG, respectively]) and at 3 hpi were transfected with 4 μg of supercoiled DNA (pJS4-F18 constructs) using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent. At 9 hpi, the cultures were rinsed with methionine-free DMEM supplemented with l-glutamine and then incubated with the same medium containing 100 μCi of [35S]methionine per ml for an additional 3 h. The cells were then harvested for immunoprecipitation analysis.

(ii) Metabolic labeling with 32PPi.

Dishes (60-mm diameter) of confluent monolayers of BSC40 cells were infected and transfected as described above. Metabolic labeling was performed from 6 to 24 hpi using phosphate-free DMEM supplemented with 1% l-glutamine, 5% phosphate-free fetal calf serum (prepared by dialysis against Tris-buffered saline (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 136 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl), and 32PPi (100 μCi/ml). Cells were harvested in the presence of phosphatase inhibitors (1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM sodium fluoride, and 40 mM β-glycerol phosphate), and lysates were analyzed by immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis.

(iii) Immunoprecipitation analysis.

Cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in 1× phospholysis buffer (10 mM NaPO4 [pH 7.4], 100 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate) and clarified by centrifugation. After incubation with the indicated antisera, antigen-antibody complexes were retrieved on protein A-Sepharose and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Phosphatase inhibitors (1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM sodium fluoride, and 40 mM β-glycerol phosphate) were included in the lysis and wash buffers.

Immunoblot analysis.

Extracts of cells and virions were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH) membranes in Tris transfer buffer (Tris-glycine, 20% methanol). Membranes were probed with the polyclonal sera indicated and then with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA). Immunoreactive species were visualized using antisera raised against the F18 (15), A30 (17), G7 (17), I3 (23), L4 (15), I1 (14), or A5 (P. Traktman, unpublished data) (35) proteins or commercial monoclonal antibodies with specificity for the FLAG or His epitopes; blots were developed by using enhanced chemiluminescence reagents.

Affinity pulldown assay for 3×FLAG-F18 and associated proteins.

Confluent 10-cm dishes of BSC40 cells were infected with vindF18 at an MOI of 5 with or without IPTG, and incubated at 37°C. At 3 hpi, 12 μg of supercoiled DNA (pJS43×FLAG-F18 constructs) was introduced using the Lipofectamine 2000 reagent. At 24 hpi, cells were harvested and incubated in FLAG lysis buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 1 μg of leupeptin/ml, 1 μg of pepstatin/ml, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride; 1 ml/107 cells) at 4°C for 30 min with end-over-end mixing. Clarified lysates were then incubated with EZview Red anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel beads for 16 h at 4°C. The beads were washed repeatedly with Tris-buffered saline (50 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl), and bound proteins were eluted by the addition of 150 ng of 3×FLAG peptide (Sigma)/μl. Eluates were subjected to analysis by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis.

Purification and analysis of virus particles.

Confluent 15-cm-diameter dishes of BSC40 cells were infected with vindF18 (with or without IPTG) at an MOI of 3; at 3 hpi, plasmids encoding WT or mutant forms of F18 (24 μg) were introduced by transfection. The cells were harvested at 24 hpi, and virus particles were purified from cytoplasmic extracts by ultracentrifugation through a 36% sucrose cushion, followed by banding on a 25 to 40% sucrose gradient. The light-scattering bands were collected by needle aspiration. Virions were quantitated using a conversion factor: 1 optical density unit at 260 nm = 1.2 × 1010 virion particles/ml. The infectious viral yield was determined by titration on BSC40 cells. Then, 1 μg of each virion preparation was resolved by SDS-PAGE for immunoblot analysis. An aliquot of purified virions was also diluted in 50 μl of water, boiled for 5 min, and applied (using a Bio-Dot microfiltration apparatus [Bio-Rad]) to a hydrated ZetaProbe membrane (Bio-Rad). Samples were denatured and renatured in situ, and the blot was then subjected to Southern dot blot hybridization using radiolabeled probe representing the vaccinia virus HindIII E and F fragments of the viral genome (6). The levels of hybridized probe were visualized and quantitated by autoradiography and phosphorimager analysis.

Gel filtration.

Gravity flow gel filtration columns (2 by 42 cm) were packed with Sephacryl S-200 or Sephacryl S-300 media (Amersham Biosciences) and equilibrated in gel filtration buffer (20 mM Tris pH [7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM, EDTA, 10 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 10% glycerol). Dextran blue and molecular-weight standards (high- and low-molecular-weight standards; Amersham Biosciences) were used to calibrate the column, which was developed at a flow rate of 1 min/ml. To analyze recombinant F18, ∼350 μg of purified N′His-F18 was utilized. To analyze F18 expressed in the context of infection, lysates were prepared from cells infected with WT virus (MOI of 5) or vindF18 with or without IPTG; rifampin was added at 3 hpi and, where appropriate, 12 μg of supercoiled DNA (encoding 3×FLAG-F18 FYI-AAA) was introduced using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent. At 24 hpi, cells were harvested and disrupted in FLAG lysis buffer. Next, 1-ml fractions were collected, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and subjected to immunoblot analysis.

Transmission electron microscopy.

Dishes (60-mm diameter) of BSC40 cells were infected with vindF18 virus (MOI of 5) with or without IPTG; at 1 hpi, plasmids encoding WT F18 or different mutants of F18 (8 μg) were introduced by transfection, as indicated. At 4 to 5 hpi, the inoculum was removed, and fresh medium containing Opti-MEM reagent in 2.5% FBS was applied. At 18 hpi, cells were rinsed with PBS and fixed in situ with 1% glutaraldehyde-0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4) and then processed for conventional electron microscopy. For analysis of purified virions, particles were concentrated by sedimentation (13,000 × g for 10 min) and then fixed in situ with 1% glutaraldehyde-0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4) prior to being processed for electron microscopic analysis. Samples were examined on a JEOL JEM2100 transmission electron microscope.

In vitro kinase assay.

Portions (100 ng) of commercially available CDK1, ERK1, and JNK/SAPK1 were assayed in 25-μl reactions containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 1 mM DTT, 5 μM rATP, and 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol), with or without the addition of 1 μg of WT or mutant F18. Reactions were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography.

In situ transcription assay.

In situ transcription reactions (1 μg of virions/50 μl) containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 5 mM DTT, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, 5 mM ATP, 1 mM GTP, 1 mM CTP, 0.02 mM UTP, and 1 μCi of [α-32P]UTP (3,000 Ci/mmol) were incubated at 30°C (22). At the indicated time points, 50-μl aliquots were removed from the master reaction mixture and quenched on ice for 30 min with an equal volume of 20% trichloroacetic acid-0.2 M Na2PPi. Trichloroacetic acid-insoluble precipitates were recovered on glass fiber filters (Whatman International, Ltd., United Kingdom), and the [α-32P]UTP incorporation was determined by Cerenkov counting.

Computer analysis.

Autoradiographic films and original data were scanned on an Epson expression scanner. Quantification of the incorporation of radiolabeled isotopes was acquired by using a Storm PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA) and quantified by using ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics). The data were plotted by using SigmaPlot software (SSPS, Chicago, IL), and final figures were assembled and labeled with Canvas software (Deneba Systems, Miami, FL). The sequence alignments were performed by using the CLUSTAL V method and Lasergene software (DNASTAR, Inc., Madison, WI) using sequences retrieved from the Poxvirus Bioinformatics Resource Center (http://www.poxvirus.org).

RESULTS

Repression of F18 impairs virion morphogenesis, leading to the accumulation of empty, abnormal IV, and aberrant, spherical MV.

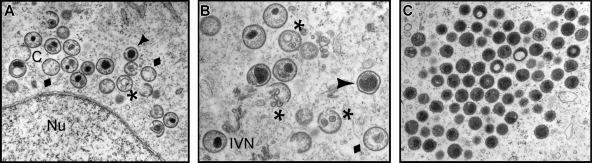

The impact of repression of F18 on virion morphogenesis was first reported 18 years ago (37). To revisit the role of F18 in more detail, we utilized transmission electron microscopy to examine the morphogenesis arrest seen in the absence of F18 expression, using the original IPTG-inducible recombinant generated and kindly supplied by Bernard Moss (referred to here is vindF18) (37). Cells infected with vindF18 (MOI of 2) in the presence or absence of IPTG were processed for transmission electron microscopy at 17 hpi. Clear defects in the progression of morphogenesis were seen when F18 was absent. First and foremost, no mature virions (MV) were seen. We observed (Fig. 1A and B) membrane crescents, empty immature particles, immature virions (IV) with unusual internal membranes, and immature virions with aberrant nucleoids. In addition, we observed clusters of electron-dense spherical particles (Fig. 1C) that accumulated at a distance from the immature forms. We believe that these are aberrant MV. Notably, we did not observe any cytoplasmic DNA crystalloids, implying that the viral DNA was not accumulating in cytoplasmic depots (1, 6, 33) but was instead packaged into the aberrant spherical particles, which we will refer to as aberrant mature virions. The presence of empty IV and empty IV with membranous inclusions has been seen before when other core proteins are repressed (27, 31). Aberrant spherical mature virions have also been seen, either when DNA encapsidation is blocked (1, 6) or when major components of the core are inactivated or repressed (13).

FIG. 1.

Electron microscopic examination reveals a clear morphogenesis defect in cells infected with vindF18-IPTG. BSC40 cells were infected with vindF18 (MOI of 2) in the absence of IPTG for 17 h and were then fixed in situ and processed for transmission electron microscopy. (A and B) Structures seen during these nonpermissive infections are indicated. Normal structures: C, crescents; IVN, immature virions with nucleoids. Abnormal structures: ⧫; empty immature virions; *, empty immature particles with unusual membranous inclusions; ▴, immature virions with aberrant nucleoids. Nu, nucleus. (C) Aberrant spherical particles that appear to be abnormal mature virions. Note the absence of MV as well as the absence of DNA crystalloids in the cytoplasm.

The characterization of these spherical particles as aberrant MV is supported by our ability to purify them by sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation; IV cannot be purified in this manner. As described in more depth below, the F18-deficient particles extracted from the light scattering band had a particle/PFU ratio that was at least 80-fold higher than those assembled in the presence of IPTG. Cumulatively, these data support the conclusion that F18 is essential for the assembly of normal IV and MV. When F18 is absent, morphogenesis continues, rather than arrests, but consequently results in the assembly of aberrant, noninfectious particles.

F18 self-associates in vivo; recombinant F18 assembles into high-molecular-weight forms.

Data obtained during the initial characterization of F18 as an abundant component of virosomes and virions suggested that it might associate into higher-order multimers and, in so doing, might serve to condense the encapsidated viral genome (10). As a first test of whether F18 self-associates in vivo, we infected BSC40 cells with vindF18 in the presence or absence of inducer and then introduced a plasmid encoding 3×FLAG-F18 under the regulation of a late viral promoter. Lysates were prepared at 24 hpi, and an α-FLAG affinity resin was used to retrieve 3×FLAG-F18 and any stably interacting proteins. Both the input sample and the eluates were resolved electrophoretically and subjected to immunoblot analysis with an α-F18 antibody (Fig. 2A). When F18 and 3×FLAG-F18 were both expressed (lanes 5), both were retrieved by the anti-FLAG resin. This association was retained even when cells were infected in the presence of rifampin (RIF), an inhibitor of virion morphogenesis (lanes 4), a finding consistent with the association of F18 into higher-order structures even in the absence of complete virion assembly. As expected, only background levels of untagged F18 were retrieved when 3×FLAG-F18 was not present (lanes 1). (In most experiments, as illustrated in later figures, this background of nonspecific retrieval was absent). The self-association of F18 molecules was seen when the resin was washed with buffers containing as much as 600 mM NaCl (lanes 6 to 8), indicating that high-affinity ionic interactions or hydrophobic interactions are involved. Moreover, incubation of the bound proteins with DNase did not diminish their association, indicating that the interaction is not mediated by DNA (lanes 9). Analysis of the eluates with α-L4 serum failed to detect the retrieval of the abundant L4 core protein (data not shown), strengthening the conclusion that the observed F18:F18 interaction was specific.

FIG. 2.

F18:F18 interactions in vivo and in vitro. (A) Interactions between F18 proteins can be detected in infected cell lysates. BSC40 cells were infected with vindF18 virus in the presence (+) (lanes 1, 3 to 5, and 6 to 9) or absence (−) (lanes 2) of IPTG and, at 3 hpi, transfected with empty vector (lanes 3) or plasmids encoding 3×FLAG-F18 (lanes 2 and 4 to 9). A portion of each clarified cytoplasmic lysate was removed prior to affinity purification (input); the remainder was used for affinity purification of 3×FLAG-F18 and any associated untagged F18 (eluate). For the samples shown in lanes 1 to 5, the beads were washed with buffer containing 150 mM NaCl prior to elution, whereas the beads for the samples shown in lanes 6, 7, and 8 were washed with buffer containing 100, 300, and 600 mM NaCl, respectively. For the sample shown in lane 9, the beads were treated with DNase prior to being washed with 150 mM NaCl. Input and eluates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblot analysis with α-F18 serum. (B) Purified, recombinant N′-His-F18 self-associates to form a high-molecular-weight complex. Recombinant N′-His-F18 protein purified from E. coli was resolved on a Sephacryl S-200 column; 1-ml fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and visualized by silver staining. The fraction numbers are depicted at the top of the immunoblot. The arrowhead indicates the void volume as assessed by dextran blue elution. The elution of the other standards is illustrated above the relevant fractions. Fractions 15 to 17 represent the peak elution of F18.

The pulldown assay described above does not elucidate whether or not F18 interacts directly with itself, since the apparent interaction could reflect the association of multiple F18 monomers with other complexes of proteins. We therefore expressed N′-His-F18 in E. coli and examined the native molecular weight of the purified protein by resolution on an S200 Sephacryl column. As shown in Fig. 2B, the elution of the F18 protein from the column reflected a native molecular weight of ∼150K. Little if any protein was found in the monomeric form (molecular weight, 11.3K). These data indicate that F18, in the absence of other viral or cellular proteins, assembles into higher-order structures that either contain a large number of subunits and/or assume a highly nonglobular shape.

The conserved cysteine residues present within the F18 protein are not involved in the formation of intermolecular disulfide bonds and are dispensable for the biological role of F18.

The fact that recombinant F18 self-associated in the absence of other proteins suggested that the apparent interaction of 3×FLAG-F18 and F18 within infected cells (Fig. 2A) might be direct, rather than being mediated by other proteins. Previously, F18 purified from virions was found to exhibit sedimentation properties consistent with the presence of both monomeric and dimeric forms (10). The primary sequence of F18 contains several cysteine residues that are highly conserved in F18 homologs encoded by diverse poxviruses (Fig. 3, red and blue circles below the alignment). These cys residues are predicted by PredictProgram (http://www.predictprotein) to form disulfide bonds (24). Although the formation of disulfide bonds is typically restricted to the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum, vaccinia virus encodes a redox pathway whose components mediate the formation of intermolecular disulfide bonds within cytoplasmic proteins (26). To assess the importance of these conserved residues for the function of F18, we established a transient complementation system (16, 19) to evaluate the competence of F18 variants to restore infectious virus production in the context of vindF18-IPTG infections. Plasmids encoding WT F18 or mutant forms in which Cys-30, Cys-37, Cys-44, and Cys-56 had been changed to serine, either individually or together, were evaluated in this assay.

FIG. 3.

Alignment of poxviral F18 homologs and identification of motifs and residues chosen for targeted mutagenesis. An alignment of the predicted amino acid sequence is shown for F18 homologs encoded by: vaccinia virus (VV, WR strain; GenBank accession no. YP_232938), variola virus (VAR; GenBank ABF23617) cowpox virus (CPV; GenBank NP_619853), monkeypox virus (MPX; GenBank NP_536476), myxoma virus (MYX; GenBank NP_051740), rabbit fibroma virus (RPX; GenBank NP_051915); swinepox virus (SPV; GenBank NP_570189), Yaba-like disease virus (YLDV; GenBank NP_073416), lumpy skin disease virus (LSDV; GenBank AAN02756), and molluscum contagiosum virus (MCV; GenBank NP_043981) (the sequences were obtained from www.poxvirus.org). Residues identical to the vaccinia virus F18 sequence are shaded in gray. The F18 mutants constructed for the present study are marked within the alignment and described in the legend below. Conserved cysteine residues evaluated for their possible participation in forming covalent F18-F18 dimers (blue and red circles, linked by horizontal lines) were changed to Ser individually and in combination. Several clusters of hydrophobic or charged residues that are highly conserved among the Poxviridae homologs were changed to Ala residues; these motifs are marked with colored lines and colored triangles, respectively. Red stop signs indicate new termination sites engineered after amino acids 70 and 82. The two PSSP motifs predicted to be recognition sites for cellular proline-directed cellular kinases are marked with curly brackets; these motifs were changed to PSAP and PSEP, both individually and in combination.

Figure 4 presents a graphic representation of the 24-h viral yield obtained from these infections/transfections; infections performed with IPTG (the black bar) served as a positive control, and those performed lacking IPTG without transfection or with transfection of empty vector (white bars) served as negative controls. All of the alleles (gray bars) exhibited statistically significant complementation activity (relative to the empty vector control, P < 0.05). Immunoblot analysis performed on the lysates confirmed that F18 had been expressed from each plasmid (Fig. 4, bottom). These results indicate that these Cys residues are not essential for F18's function during infection, whether or not they participate in disulfide bond formation. To test directly whether F18 does indeed form covalently linked dimers in vivo, purified virions and infected cell lysates were resolved by both nonreducing and reducing SDS-PAGE and then subjected to immunoblot analysis with our α-F18 serum (not shown). Even when DTT was omitted, only the 11,000-Mrmonomeric form of F18 was seen, indicating that F18 does not form intermolecular disulfide bond(s) in vivo.

FIG. 4.

Establishment of a transient complementation assay for structure/function analysis of F18; conserved cysteine residues are not required for the biological activity of F18. Cells were infected with vindF18 in the presence (+) or absence (−) of IPTG and either left untransfected or transfected with empty vector or plasmids encoding mutant alleles in which Cys residues at positions 30, 37, 44, or 56 were changed to Ser, either individually or in pairs, as shown. At 24 hpi, the yield of infectious virus was determined by plaque assay. The data are shown graphically. Here and in later figures, the horizontal black line represents the baseline yield obtained from cells infected without IPTG and transfected with empty vector. The expression of each form of F18 was confirmed by immunoblot analysis, which is shown beneath the graph.

Clusters of charged residues of F18 protein contribute to the ability of F18 to support virion morphogenesis but are not essential for F18-F18 interactions.

The F18 protein is a highly hydrophilic protein with 16 basic and 9 acidic residues; the predicted pI of the protein is 9.37. We therefore reasoned that conserved clusters of charged residues might mediate protein-protein interactions and/or other activities of F18 important for its biological role. Therefore, we constructed multiple alleles of F18 in which clusters of charged residues were changed to ala, as illustrated in Fig. 3 (colored wedges). Mutant alleles in which stop codons were inserted to terminate the protein after residue 70 or 82 (Stop70 and Stop82) were also constructed. Each of these alleles was evaluated in the transient complementation assay described above; the data are shown graphically in Fig. 5A. Two alleles, KVDK→AVAA and ERR→AAA, retained full complementation activity, whereas the alleles encoding DVR→AVA, E36→A, ER→AA, or R80→A substitutions exhibited partial complementation activity. Mutation of two charged clusters, KEGR→AAGA and KAVKVCD→AAVAVCQ, abolished complementation ability. Interestingly, these two clusters map near each other at the N′ terminus of the protein. Immunoblot analysis confirmed that the mutant proteins were each expressed, although some were present at diminished levels (Fig. 5A, bottom panel). It may be that this reduced expression contributes to the decreased complementation activity; it may also be that F18's stability is compromised when virus production, and presumably morphogenesis, is impaired. The two alleles containing truncations at the C′ terminus were unable to complement the F18-deficient infections. The Stop82 protein, but not the Stop70 protein, was readily detected by immunoblot analysis. We do not know whether the Stop70 protein is unstable or whether it lacks the dominant epitope recognized by our polyclonal antiserum.

FIG. 5.

Assessing the contribution of conserved clusters of charged residues to the function of F18 in vivo. (A) Transient complementation assay. Alleles of F18 in which clusters of charged residues had been changed to Ala residues or in which premature stop codons had been introduced were tested in the transient-complementation assay. The viral yield was determined at 24 hpi (graph), and protein expression was confirmed by immunoblot assay (bottom panel). (B) The KEGR→AAGA form of F18 retains the ability to interact with endogenous F18. Cells were infected with vindF18+IPTG and transfected with empty vector or plasmids encoding the 3×FL-WT and 3×FL-KEGR→AAGA forms of F18. As described for Fig. 2, affinity pulldown assays were used to compare the ability of the two tagged proteins to interact with endogenous F18. (C) Transient expression of WT F18, but not the KEGR→AAGA or KAVKVCD→AAVACQ forms of F18, restores virion morphogenesis in the context of a vindF18 -IPTG infection. Cells were infected with vindF18-IPTG and transfected with empty vector (data not shown) or plasmids encoding WT F18 or the KEGR→AAGA or KAVKVCD→AAVACQ forms of F18. At 17 hpi, the cells were processed for conventional electron microscopy. Representative images are shown.

This analysis identified several mutants of F18 that were expressed but could not restore the production of infectious virus. To probe further into their loss of function, we performed the pull-down assay described in Fig. 2A to monitor whether the KEGR→AAGA mutation, for example, compromised the ability of F18 to interact with itself in vivo (Fig. 5B); in fact, the behavior of this protein was indistinguishable from that of the WT protein. To determine whether it was virion morphogenesis or virion infectivity that was defective when the KEGR→AAGA or KAVKVCD→KAVKVCQ proteins were the only form of F18 expressed, we undertook electron microscopic analysis. Cells were infected with vindF18-IPTG, transfected with either empty vector or plasmids encoding WT or mutant forms of F18, and processed for electron microscopy analysis at 17 hpi. For this and subsequent electron microscopy analyses, immunoblot assays were performed on parallel cultures to verify that the WT and mutant proteins were expressed to comparable levels (data not shown). Under these conditions, the transfection efficiency was very high, and ∼90% of the cells transfected with the plasmid encoding WT F18 showed the full spectrum of normal morphogenesis intermediates, as well as mature virions (Fig. 5C, top panel). In contrast, the phenotype of cells expressing the KEGR→AAGA or KAVKVCD→KAVKCQ proteins (Fig. 5C, bottom panels) was indistinguishable from those infected with vindF18-IPTG and transfected with empty vector (not shown) or left untransfected (see Fig. 1). Only empty IV, IV with unusual membranous inclusions or abnormal nucleoids, and aberrant spherical electron-dense particles were seen. Thus, mutation of these charged clusters spares the F18-F18 interaction but ablates the ability of the F18 protein to support virion morphogenesis.

Clusters of hydrophobic residues contribute to the self-association of F18 protein and are essential for the contribution of F18 to virion morphogenesis.

Since the self-association of F18 was resistant to high concentrations of NaCl (Fig. 2A), we reasoned that it might in fact be mediated by hydrophobic interactions. We therefore identified several highly conserved clusters of hydrophobic (and/or aromatic) residues within F18 and performed targeted mutagenesis of these clusters to assess their contribution to the biological function of F18. As shown in Fig. 3, we generated alleles of F18 in which the hydrophobic clusters identified as FYI (gray line), YLVL (light green line), CVL (pink line), and VPFM (purple line) were changed to alanine. Plasmids encoding these mutant alleles were tested in our transient-complementation assay in order to assess their ability to substitute for endogenous F18 (Fig. 6A). Although the CVL→AAA mutant retained significant complementation activity, the N′-terminal mutants FYI→AAA and YLVL→AAAA, and the C′-terminal mutant VPFM→AAAA, were unable to restore the production of infectious virus. Immunoblot analysis (bottom panel) indicated that each of these proteins was expressed, although the YLVL→AAA variant appeared to be reduced in its abundance.

FIG. 6.

Assessing the contribution of conserved clusters of hydrophobic and/or aromatic residues to the function of F18 in vivo. (A) Transient complementation assay. Alleles of F18 in which clusters of hydrophobic and/or aromatic residues had been changed to Ala were assessed in the transient-complementation assay. The viral yield was determined at 24 hpi, and protein expression was confirmed by immunoblot assay (bottom panel). (B to D) F18 variants containing FYI→AAA, YLVL→AAAA or VPFM→AAAA substitutions cannot support virion morphogenesis. Cells were infected with vindF18-IPTG and transfected with plasmids encoding WT F18 (see Fig. 5) or the FYI→AAA, YLVL→AAAA, or VPFM→AAAA variants. At 17 hpi, cells were processed for conventional electron microscopy. Representative images are shown.

The inability of these mutants to enhance infectious virus production might represent a block in virion morphogenesis or a deficit in the infectivity of the virions produced. We therefore performed electron microscopic analysis to visualize morphogenesis in infected cells expressing only these mutant forms of F18 (Fig. 6B to D). Whereas WT F18 was able to restore the production of normal IV and MV (see Fig. 5), the cells expressing these three mutant forms of F18 looked indistinguishable from those left untransfected and hence lacking F18 (see Fig. 1). Hence, F18 proteins with mutations in the FYI, YLVL, or VPFM clusters of hydrophobic residues cannot support virion maturation.

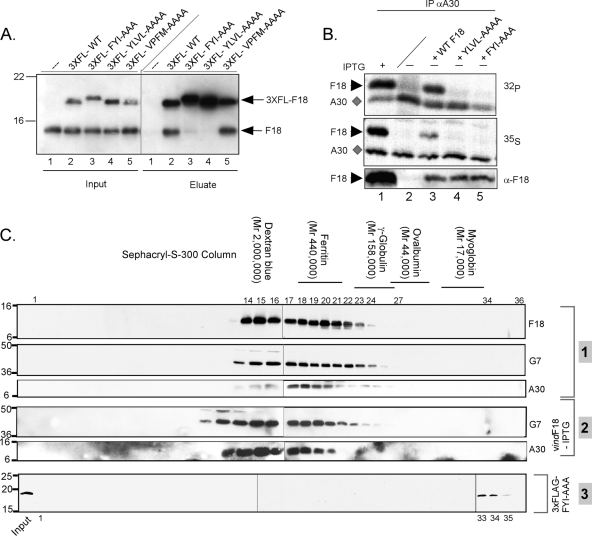

As a first assessment of the biochemical properties of these mutant forms of F18, we utilized our affinity pulldown assay to determine whether the variants retained the ability to interact with endogenous F18. As shown in Fig. 7A, when untagged WT F18 and 3×FLAG-WT F18 were coexpressed, both were retrieved by the α-FLAG resin (lane 2), a finding consistent with the association of F18 molecules into higher-order structures. However, untagged F18 was not retrieved on the α-FLAG resin when the 3×FLAG-FYI or 3×FLAG-YLVL forms of F18 were expressed (lanes 3 and 4, respectively). Interestingly, these two alleles contain mutations in the N′ terminus of F18. In contrast, the VPFM→AAAA mutant, which is altered in the C′ terminus of the protein, retained the ability to interact with the untagged F18 protein. Thus, these data suggest that the ability of the F18 protein to interact with itself is necessary, but not sufficient, for its ability to support virion morphogenesis. They are also consistent with this interaction being mediated by hydrophobic interactions.

FIG. 7.

Hydrophobic/aromatic motifs within the F18 protein mediate its self-association and interaction with other proteins. (A) The FYI→AAA and YLVL→AAAA forms of F18 lack the ability to interact with endogenous F18. Cells were infected with vindF18+IPTG and transfected with empty vector (lanes 1) or plasmids encoding 3×FLAG-tagged WT or mutant forms of F18 (lanes 2 to 5). α-FLAG beads were used to retrieve the 3×FLAG-tagged F18 and any interacting proteins. Both the input and the eluate fractions were subjected to immunoblot analysis with α-F18. (B) Mutations in hydrophobic clusters prevent the interaction of F18 and A30. Cells were infected with vindF18+IPTG or vindF18-IPTG as shown and left untransfected or transfected with plasmids encoding WT F18 or the YLVL→AAAA or FYI→AAAA forms of F18. Cells were metabolically labeled with 32PPi or [35S]Met from 6 to 24 hpi prior to being harvested and analyzed by immunoprecipitation with α-A30 serum. The A30 protein (⧫) and any coprecipitating F18 protein (▸) were visualized by autoradiography. The bottom panel represents an immunoblot analysis of the lysates, confirming the expression of F18 proteins (▸). (C) Utilization of gel filtration chromatography to assess the native molecular weight of protein complexes containing the A30, G7, or F18 proteins. Cells were infected with WT virus (group 1) in the presence of RIF. Lysates were prepared at 24 hpi and resolved on a Sephacryl S-300 column. A similar protocol was used to monitor the native molecular weight of G7 and A30 during vindF18-IPTG infections (also performed +RIF) (group 2). A third experiment was performed to monitor the elution profile of the 3×FL-FYI→AAA of F18 that was expressed in cells infected with vindF18-IPTG (+RIF); this protein was detected by immunoblot analysis with an α-FLAG antibody (group 3). The elution of molecular-weight standards and relevant fraction numbers are shown above the immunoblots.

F18 associates with the A30 protein, and this association is lost when the FYI or YLVL motifs are altered.

In addition to the apparent ability of F18 to interact with itself, we have previously shown (17) that the F18 protein coprecipitates with the A30 protein. A30 is a small phosphoprotein that is also essential for virion morphogenesis. Cells infected with vindF18 with or without IPTG and transfected with plasmids expressing WT F18 or the FYI→AAA or YLVL→AAAA mutants were metabolically labeled with either [35S]Met or 32PPi. Lysates were analyzed by immunoprecipitation with the α-A30 antibody (Fig. 7B). WT F18 was retrieved with A30 whether it was expressed from the viral genome or the transfected plasmid (lanes 1 and 3); confirmation that the coprecipitating protein was indeed F18 was obtained by immunoblot analysis of the resolved immunoprecipitates (data not shown). Coprecipitation of F18 was specific and not due to the aggregation of F18 into large protein complexes, since F18 was not retrieved when the immunoprecipitation was performed with preimmune serum (not shown). In contrast to the behavior of the WT F18 protein, neither the YLVL→AAAA (lane 4) or FYI→AAA (lane 5) forms of F18 were coprecipitated with the A30 protein, despite being stably expressed (bottom panel).

The A30 protein has been shown to stably associate with 5 other vaccinia virus proteins that are also required for the enclosure of virosomal proteins by crescent membranes to form immature virions (17, 27, 31). This complex of proteins also associates with the F10 protein kinase (28, 30). The F18 protein was not identified as a component of this complex, which is somewhat surprising given our findings. To further probe the interaction of F18 with A30 and the other members of the A30-containing complex, infected cell lysates were resolved on a Sephacryl S-300 gel filtration column, which can resolve proteins and complexes ranging from 10 to 1,500 kDa. These lysates were prepared from WT infections performed in the presence of RIF so as to analyze cytoplasmic protein complexes rather than the contents of mature virions. The F18 protein was distributed into two peaks: one eluted in the void volume (identified by the elution of dextran blue [Mr = 2,000,000]), while the other corresponded to a native molecular mass of 158 to 440 kDa (Fig. 7C, section 1). No monomeric F18 was detected. These same fractions were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antisera specific for both A30 and G7. G7 is a member of the six-protein complex described above and is known to bind directly to A30 (17, 27, 28). As shown in Fig. 7C, section 1, we observed that the G7 and A30 proteins exhibited the same elution profile as F18. This result is consistent with F18, A30, and G7 being present in a large complex that forms within the cytoplasm of infected cells. To determine whether F18 is required for the assembly of this complex, we monitored the elution profile of A30 and G7 in lysates prepared from cells infected with vindF18-IPTG (i.e., when no F18 is expressed) (Fig. 7C, section 2). The absence of F18 had no significant impact on the elution of A30 and G7, suggesting that F18 may be associated with an A30- and G7-containing complex, but is not required for its formation. We also resolved extracts prepared from cells infected with vindF18-IPTG and transfected with the plasmid expressing the 3×FLAG-FYI→AAA variant of F18 (Fig. 7C - 3). The elution profile of this form of F18 is consistent with its remaining as a monomer within infected cells, which is consistent with our earlier observations that it does not interact with WT F18 or A30 (Fig. 7A and B) in immunoprecipitation assays.

F18 is a substrate for cellular proline-directed kinases; phosphorylation occurs at Ser-53 and Ser-62 in vitro and in vivo.

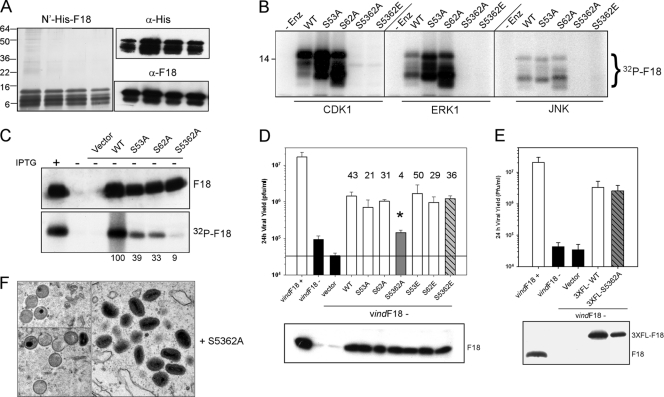

One of the earliest properties ascribed to F18 was its phosphorylation on serine residues within virus-infected cells (9). We have confirmed that F18 is highly phosphorylated and that this phosphorylation is largely independent of the viral F10 kinase (data not shown). The primary sequence of the F18 protein contains two conserved motifs that are perfect recognition sites for cellular proline-directed kinases (Fig. 3, PSS53P and PSS62P). We generated alleles of F18 in which the PSSP motifs were altered to PSAP, either individually or together, to prevent phosphorylation; both motifs were also changed to PSEP to introduce negative charges that would mimic constitutive phosphorylation. First, pET16b plasmids encoding either WT F18 or the PSAP or PSEP mutants were introduced into E. coli and expression of N′his-F18 was induced. The tagged protein was purified by Ni2+-affinity chromatography. The purified protein contained a cluster of protein species with electrophoretic mobilities ranging from ∼8 to 15 kDa, all of which were recognized both by α-His and α-F18 reagents (Fig. 8A). Presumably, the distinct electrophoretic mobilities reflect conformational differences. These peak fractions were incubated with commercially available preparations of the proline-directed kinases CdK1/cyclin B, ERK1, or JNK1 in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. F18 was phosphorylated by all three kinases (Fig. 8B). Purified preparations of the viral F10 kinase were unable to phosphorylate F18 (data not shown). Mutation of either Ser-53 or Ser-62 (PSA53P or PSA62P) did not compromise the ability of the F18 protein to serve as a substrate for any of these enzymes. However, phosphorylation was essentially blocked when both Ser-53 and Ser-62 were changed to Ala simultaneously (or Glu). These data indicate that the Ser residues within PSSP motifs are indeed the targets of phosphorylation by these cellular proline-directed kinases in vitro.

FIG. 8.

Characterization of the role of the PSSP motifs in the phosphorylation of F18 in vitro and the phosphorylation and biological activity of F18 in vivo. (A) Purification of recombinant F18. Recombinant N′-His-F18 was expressed in E. coli and purified by metal ion chromatography; the peak of purified protein was examined by silver staining (left panel) and immunoblot analysis with α-His and α-F18 probes (right panels). (B) The phosphorylation of F18 in vitro by proline-directed kinases depends upon the two PSSP motifs. N′-His-tagged preparation of WT F18 or the S53A, S62A, S5362A, and S5362E mutants were used as substrates for in vitro kinase assays performed with CDK1, ERK1, or JNK in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. Phosphorylation was assessed by autoradiography; only the relevant portion of the film is shown. (C) The phosphorylation of F18 in vivo depends on the PSSP motifs. Cells were infected with vindF18+IPTG (lane 1) or vindF18-IPTG (lanes 2 to 7) and left untransfected (lanes 1 and 2) or transfected with empty vector (lane 3) or plasmids encoding WT F18 (lane 4) or the S53A, S62A, and S5362A variants of F18 (lanes 5 to 7, respectively). Cells were metabolically labeled with 32PPi. The expression of each form of F18 was confirmed by immunoblot analysis (top panel), and the F18 was retrieved by immunoprecipitation and visualized by autoradiography (bottom panel). 32P incorporation was normalized to that seen for WT F18; the values are shown beneath the lanes. (D) The S5362A allele of F18 shows a loss of biological activity. Plasmids encoding WT F18 or the S53A, S62A, S5362A, S53E, S62E, and S5362E variants of F18 were assessed for their transient-complementation activity. The fold increase in viral yield relative to what was seen after transfection with empty vector is shown above the relevant bar. For the S5362A variant, the value obtained for viral yield (*, 4-fold) was statistically different from that seen after expression of the other forms of F18. The protein was confirmed by immunoblot (bottom panel). (E) Incorporation of a 3×FLAG epitope restores the biological activity of the S5362A variant of F18. The same transient-complementation protocol was used to compare the biological activity of 3×FL-WT F18 and 3×FL-S5362A F18. Expression of the proteins was confirmed by immunoblot (bottom panel). (F) The nonphosphorylatable S5362A variant of F18 can support virion morphogenesis. Cells were infected with vindF18-IPTG and transfected with plasmids encoding WT F18 (see Fig. 5) or the S5362A variant. At 17 hpi, cells were processed for conventional electron microscopy; representative images are shown.

To determine whether the same motifs were the targets of phosphorylation in vivo, cells were infected with vindF18-IPTG and transfected with plasmids encoding the same alleles of F18. Cells were metabolically labeled with 32PPi, and the F18 proteins were retrieved by immunoprecipitation. Protein accumulation was visualized by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 8C, top panel), and phosphorylation of F18 was assessed by autoradiography (bottom panel). All of the proteins were expressed to similar levels. However, the extent of phosphorylation decreased to 39 or 33% when either Ser-53 or Ser-62 was mutated to Ala, respectively, and to 9% of WT levels when both Ser residues were removed. These data indicate that both Ser-53 and Ser-62 are phosphorylated in vivo and that these residues are the predominant sites on which F18 undergoes phosphorylation.

Phosphorylation of F18 is important for its biological role.

Having identified the two major, if not only, sites on which F18 undergoes phosphorylation in vivo, we wanted to assess the contribution of phosphorylation to F18's biological role. Therefore, the phosphorylation site mutants were compared to WT F18 in our transient-complementation assay (Fig. 8D). When the WT, S53A, or S62A proteins were expressed, the 24-h yield of infectious virus was increased by ∼40-, 20-, or 30-fold relative to cells transfected with empty vector. These increases were statistically significant (P < 0.05). In contrast, only a 4-fold increase was seen when the S5362A mutant was expressed. This value represented a statistically significant increase, but the difference between 4-fold (S5362A) and 40-fold (WT) was also statistically significant (P < 0.05). This loss of function was reversed when the ser residues were changed to Glu instead of Ala; expression of S5362E led to a 36-fold increase in viral yield above that seen with empty vector. Glu residues are often considered phosphomimetic because of their negative charge, and in this case introduction of the negative charge was sufficient to restore biological function.

Further confirmation that it was the negative charges introduced by phosphorylation or by the Ser→Glu substitutions that were important for biological function came from transient complementation assays in which we expressed 3×FLAG-tagged versions of F18 rather than untagged proteins. The 3×FLAG epitope introduces a net charge of −9. As shown in Fig. 8E, the 3×FLAG-S5362A allele retained full transient-complementation activity. Apparently, the loss of phosphorylation of F18 can be compensated for by the presence of the net negative charge of the 3×FLAG epitope.

In the presence of the F18 S5362A protein, morphogenesis is completed, but the mature virions have a reduced specific infectivity.

To assess how phosphorylation might affect the function of F18, we first determined whether the untagged S5362A protein retained the ability to support F18-F18 and F18-A30 interactions, using the assays described above. Indeed, the protein was indistinguishable from the WT protein in these assays (data not shown). To distinguish whether phosphorylation was required for virion morphogenesis or for virion infectivity, we performed electron microscopic analysis of cells infected with vindF18-IPTG and transfected with the plasmid encoding the S5362A variant of F18. As shown in Fig. 8F, the S5362A form of F18 was clearly able to support virion morphogenesis. When it was the sole source of F18, the full array of assembly intermediates was seen, as were numerous mature virions.

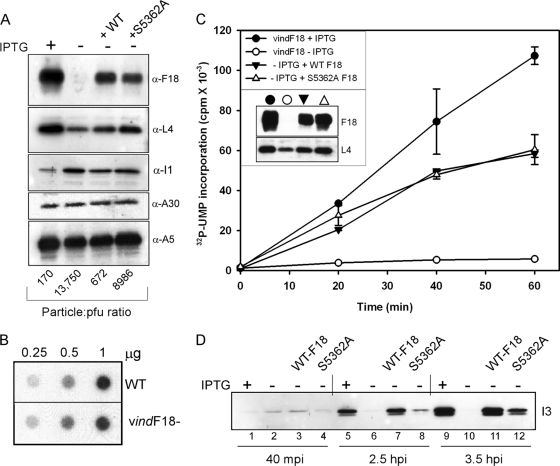

The MV produced during infections with vindF18+IPTG, vindF18-IPTG, or vindF18-IPTG in the presence of plasmids expressing WT F18 or S5362A F18 were purified by ultracentrifugation through a 36% sucrose cushion followed by banding on a 25 to 40% sucrose gradient. The ultrastructure of the virions was investigated after embedding and thin sectioning (data not shown). The particles purified from the vindF18-IPTG infection consisted solely of the round, spherical, aberrant MV, whereas brick-shaped MV with the typical internal core structure were seen in the other preparations. The protein content of the purified virions was assessed by immunoblot analysis after resolving 1 μg of each preparation by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 9A). Whenever the F18 protein had been expressed during the infection, it was incorporated into the virions (top blot). We also confirmed that several other core proteins, including L4, I1, A30, and A5, were encapsidated at grossly similar levels in the four preparations. The specific infectivity of each preparation was also determined. Representative results are shown underneath the relevant lanes in Fig. 9A. The particle/PFU ratio of the vindF18-IPTG particles was 13,750, ∼80-fold higher than the ratio of 170 obtained for the vindF18+IPTG virions. When WT F18 was transiently expressed during vindF18-IPTG infections, the particle/PFU ratio was 672. This value is only ∼4-fold higher than that obtained for the vindF18+IPTG infections, suggesting that the utilization of F18 expressed from the transfected plasmid was quite efficient. In contrast, the particle/PFU ratio of the vindF18-IPTG infections in which the sole source of F18 was the S5362A protein was 8986, which was ∼50-fold higher than that seen for the vindF18+IPTG virions, ∼14-fold higher than that seen for the virions produced when WT F18 was expressed from the transfected plasmid and only 1.5-fold less than that seen for the vindF18-IPTG virions. Thus, virions encapsidating the S5362A form of F18 have a clear and reproducible loss of specific infectivity despite having an apparently normal ultrastructure.

FIG. 9.

Characterization of the protein content, DNA content, and transcriptional competence of virions that lack F18 or encapsidate WT or phosphorylation-deficient F18. (A) Protein content of purified virions. Cells were infected with vindF18 virus in the presence or absence of IPTG and left untransfected or transfected with plasmids encoding WT F18 or S5362A F18. At 24 hpi, the cells were harvested, and virions were purified by sucrose gradient centrifugation and quantitated by measuring the optical density at 260 nm. Then, 1-μg portions of the different preparations of purified virions were resolved electrophoretically and subjected to immunoblot analysis with sera directed against the F18, L4, I1, A30, or A5 core proteins. The infectivity of the preparations was also quantitated by plaque assay; the particle/PFU ratio of each preparation is shown at the bottom of the appropriate lane. (B) Purified vindF18-IPTG virions contain viral DNA. Different amounts (0.25, 0.5, and 1 μg) of purified wt and vindF18-IPTG particles were subjected to Southern dot blot analysis to quantitate the levels of encapsidated viral DNA. The levels of hybridized probe were visualized and quantitated by autoradiography. (C) In situ transcription assays of purified virions. Portions (4 μg) of purified virions were permeabilized and incubated with [32P]UTP in order to activate the in situ transcription of early genes. The incorporation of [32P]UTP into RNA was quantitated for aliquots removed after 0, 20, 40, and 60 min of incubation. The immunoblot shown in the inset confirms that the virion preparations contain comparable levels of the L4 protein and do or do not contain F18 as expected. (D) Virions containing only the S5362A form of F18 are delayed and diminished in their ability to induce early gene expression in vivo. Cells were inoculated on ice with equivalent numbers of virions (300/cell) purified from cells infected with vindF18+IPTG (lanes 1, 5, and 9), vindF18-IPTG (lanes 2, 6, and 10), or vindF18-IPTG and transfected with plasmids encoding WT F18 (lanes 3, 7, and 11) or the S5362A form of F18 (lanes 4, 8, and 12). After 1 h, the inocula were removed, and the cultures were shifted to 37°C. At 40 min postinfection, 2.5 hpi, and 3.5 hpi, the cells were harvested, and the expression of the early protein I3 was monitored by immunoblot analysis.

As a first step toward understanding the poor infectivity of the vindF18-IPTG and vindF18-IPTG+S5362A virions, we wanted to perform in situ transcription assays. In this assay, virions are permeabilized with nonionic detergent and monitored for their ability to utilize the encapsidated transcriptional machinery to transcribe early genes present on the encapsidated genome. To make this analysis meaningful, we first had to determine whether or not the DNA genome was in fact encapsidated when F18 was repressed. The lack of DNA crystalloids in the cytoplasm of vindF18-IPTG infections implied that it would be packaged, but early reports in the literature suggested that F18 might serve as a component of the nucleoprotein complex and might therefore enter virions on the genome. We therefore performed dot blot hybridization analyses of 0.25, 0.5, and 1 μg of WT and vindF18-IPTG virions (Fig. 9B). The DNA content of these preparations was equivalent. We therefore proceeded to assess the competence of these virion preparations for transcription in situ (Fig. 9C) (11, 13, 15, 22). Clearly, the vindF18-IPTG virions were essentially inert for transcription activity (Fig. 9C) compared to the vindF18+IPTG virions. The virions purified from vindF18-IPTG infections transfected with plasmids encoding WT F18 or S5362A virions were equally competent in this assay; both were reduced in activity compared to the virions purified from vindF18+IPTG infections. These data indicate that a lack of F18 phosphorylation does not cause a gross structural defect in the virion core or severely alter the accessibility of the genome to the encapsidated transcriptional machinery.

Finally, we compared the early events of an infectious cycle initiated with these purified virion preparations. Parallel dishes of cells were infected with 300 particles of the various virion preparations, which corresponds to an MOI of 5 for the vindF18+IPTG preparation; the adsorption was carried out on ice for 1 h to synchronize infection. The inocula were then removed and replaced with prewarmed medium. At 40 min, 2.5 h, or 3.5 h postinfection, the cytopathic effect was assessed microscopically (results not shown), and lysates were prepared for immunoblot analysis. The vindF18-IPTG virions did not induce a cytopathic effect, suggesting that they are either unable to enter target cells or unable to direct early gene expression. In contrast, obvious cytopathic effects were seen with equivalent kinetics after infection with the vindF18+IPTG virions or the virions encapsidating plasmid-expressed WT or S5362A F18, arguing against any gross difference in the binding or entry of these three virion preparations. When we monitored the accumulation of the I3 single-stranded DNA-binding protein (23), which is expressed at both early and intermediate times postinfection, we did observe differences between the virion preparations. The F18-deficient virions were unable to induce any I3 expression, even after 3.5 h of infection (lanes 6 and 10), a finding consistent with the lack of cytopathic effect seen after inoculation with these virions. The vindF18+IPTG virions induced strong expression of I3 by 2.5 hpi (lane 5), and the virions containing plasmid-expressed WT F18 were nearly as efficient (compare lanes 5 and 7 and lanes 9 and 11). After infection with the S5362A F18-containing virions, there was a noted diminution in the expression of I3. At 2.5 hpi, ∼7.5-fold less I3 had accumulated than after infection with the virions containing WT F18 (compare lanes 7 and 8); at 3.5 hpi, the difference was ∼3.5-fold (compare lanes 11 and 12). Thus, the absence of F18 phosphorylation appears to diminish some aspect of early gene expression in vivo. These data suggest that the decreased specific infectivity of virions encapsidating the S5362A F18 protein is due, at least in part, to delayed and diminished early gene expression.

DISCUSSION

The 11-kDa F18 protein, also known as p11, VP11, and F17, is a major component of vaccinia virions, having been estimated as comprising ∼11% of the virion mass (25). Initial reports indicated that it was a DNA-binding protein, exhibiting a preference for supercoiled DNA and demonstrating maximum binding at 30 mM NaCl (10). When interacting with DNA, the protein was suggested to reach half-saturation at a molar ratio of 100 (protein/DNA), suggesting that F18 might coat the viral genome within virions. However, our earlier studies (32) indicated that F18 was distributed throughout the interior of immature virions and did not localize to nucleoids, thought to represent the newly encapsidated genome, when they were present. Within mature virions, F18 appeared to localize to a ring corresponding to the outer boundary of the core. Although we do not yet have an accurate picture of where the DNA is found within the core, it is presumed to be in the interior of the core in a tubelike structure rather than at the periphery (4). In addition, we have shown that normal levels of F18 are found within virions that lack encapsidated DNA due to a defect in the telomere-binding protein I6 (6). Taken together, these data suggest that F18 certainly does not enter cores with the viral genome and, although it may interact with the DNA once it is packaged, its position at the periphery of the core makes this contact unlikely. Whether or not the putative DNA-binding activity of the F18 protein is physiologically relevant remains to be revisited; F18 has also been shown to bind actin in vivo and in vitro, but this interaction is not physiologically relevant (20). The highly basic nature of the F18 protein may be responsible for nonspecific interactions with both actin and DNA.

The only genetic analysis of F18 prior to the present study demonstrated that repression of F18 causes an arrest in virion morphogenesis and hence a dramatic reduction in the production of infectious progeny (37). The structure/function analysis of F18 reported here was undertaken to further dissect the roles played by F18 in virion morphogenesis, to identify motifs within F18 that are important for its biological function, and to localize the sites of F18 phosphorylation and the importance of this modification in vivo.

Our data support the earlier observation (10) that F18 can interact with itself to form high-molecular-weight complexes, and we have now shown conclusively that this self-association is not mediated by intermolecular disulfide bonds. In addition to interacting with itself, we have confirmed our own observation (17) that F18 can be coimmunoprecipitated with the A30 protein. A30 is one component of a six-protein complex (A30, G7, D2, D3, J1, and A15) involved in virion morphogenesis (17, 27, 28, 31). We show here that, when cytoplasmic extracts of infected cells are resolved by gel filtration chromatography, the elution of F18 mirrors that of both A30 and G7. These data support an association of F18 not only with A30, but with the six-protein complex. F18 is not required for the formation of the complex; however, because the elution profile of A30 and G7 is not disturbed when F18 is absent. This finding is in contrast to the previous observation that many of the members of this complex depend on one another for their stability (5, 27). Thus, the aberrant immature virions that we see in the absence of F18 reflect a role for F18 itself in IV formation rather than reflecting an absence of the six-protein complex. Furthermore, the phenotype seen upon repression of F18 does not precisely phenocopy that seen upon disruption of the six-protein complex. First, the aggregated virosomes seen upon repression of A30 or G7 (27, 31) are not seen upon repression of F18. Second, although empty and aberrant IV accumulate in each case, F18-deficient infections also lead to the formation of spherical, electron-dense, aberrant MV. These noninfectious, aberrant MV can be purified by sucrose gradient sedimentation and contain the majority of virion proteins as well as the viral genome. However, they are inert in the in situ transcription assay and do not induce any cytopathic effect, suggesting that they are probably incapable of entering target cells.

We have shown in this report that the interaction of F18 with itself, as well as the F18-A30 interaction, depends on several clusters of hydrophobic/aromatic amino acids found in the N′ terminus of the F18 protein (FYI, YLVL). Whether these are independent events or whether only mutimerized F18 can interact with the A30-containing complex has not been determined. Both of the mutants which show defective protein-protein interactions fail to support virion morphogenesis or the production of infectious virus, despite being stably expressed. Thus, there is a correlation between the biological competency of F18 and its ability to participate in protein-protein interactions. A third mutant containing substitutions in a C′-terminal hydrophobic/aromatic motif (VPFM) is unable to support virion assembly despite its competence for protein-protein interactions. Several clusters of charged amino acids are also essential for the biological function of F18, although mutations within these motifs do not disrupt F18-F18 or F18-A30 interactions. Here, too, the mutant F18 protein cannot support virion morphogenesis, suggesting that F18 may participate in additional protein-protein interactions that remain to be discovered.

Previous reports indicated that the majority of the F18 molecules within cells and virions was phosphorylated on two serine residues (9). The fact that this phosphorylation was only moderately reduced when the viral F10 kinase was defective (data not shown) suggested that F18 might be modified by cellular kinases. The primary sequence of F18 contains two motifs that represent canonical target sites for cellular proline-directed kinases (PSSP), and we show here that the WT F18 protein, but not a variant lacking both motifs (PSA53P and PSA62P), can be phosphorylated in vitro by CDK1, ERK, and JNK. The same motifs are required for the phosphorylation of F18 in vivo. The concurrent loss of both of these motifs significantly compromises the biological activity of F18; the yield of infectious virus obtained after transient expression of the unphosphorylatable variant of F18 is 10-fold less than that obtained after transient expression of WT F18. If either one of the sites is altered, the biological competence of the protein is not reduced significantly, suggesting that phosphorylation of the remaining site is sufficient for protein activity. This possibility is supported by the observation that the upstream site (PSS53P), in particular, is poorly conserved in the F18 orthologs encoded by diverse poxviruses.

The primary impact of phosphorylation in this case appears to be the introduction of negative charges, since the addition of an acidic 3×FLAG-epitope to the unphosphorylatable variant of F18 restores its biological activity. Likewise, an allele in which both PSSP motifs had been changed to PSEP was as active as the WT allele in the transient-complementation assay. These latter findings were somewhat surprising, since our earlier analysis of a viral recombinant in which the H1 phosphatase had been repressed (15) indicated that a significant number of the F18 molecules within mature virions have been subjected to dephosphorylation. H1-deficient virions have a somewhat unstable core structure and show a defect in transcriptional activity. Hence, a more detailed analysis of the structure, stability, and specific infectivity of purified virions containing the PSE53P, PSE62P form of F18 may well reveal a biological role for the H1-mediated dephosphorylation of F18.

Perhaps unexpectedly, our electron microscopic analyses indicated that the nonphosphorylatable S5362A allele of F18 retained the ability to support virion morphogenesis. The full spectrum of viral intermediates and mature virions was observed upon plasmid-mediated expression of this protein. However, the purified virions had a significant reduction in their specific infectivity. Their activity in an in situ transcription assay was comparable to virions containing plasmid-expressed WT F18, as was the timing and extent of the cytopathic effect that they induced in target cells. However, their ability to induce early viral gene expression was delayed and reduced relative to virions containing WT F18. Thus, the phosphorylation of F18 may have an impact on the entry or trafficking of viral cores or on their ability to synthesize and extrude nascent mRNAs within the cytoplasm of target cells. Further study of how the F18 protein contributes to core assembly and virion maturation, and moreover how the dynamic phosphorylation of F18 contributes to virion infectivity, will certainly be of significant interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant awarded to P.T. by the National Institutes of Health (9R01 A1063620).

We thank Clive Wells and Beth Unger for their expertise and assistance in preparing the samples for electron microscopy, and we thank Matthew Greseth and Kathy Boyle for helpful discussions throughout the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 14 April 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cassetti, M. C., M. Merchlinsky, E. J. Wolffe, A. S. Weisberg, and B. Moss. 1998. DNA packaging mutant: repression of the vaccinia virus A32 gene results in noninfectious, DNA-deficient, spherical, enveloped particles. J. Virol. 72:5769-5780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chakrabarti, S., J. R. Sisler, and B. Moss. 1997. Compact, synthetic, vaccinia virus early/late promoter for protein expression. Biotechniques 23:1094-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung, C. S., C. H. Chen, M. Y. Ho, C. Y. Huang, C. L. Liao, and W. Chang. 2006. Vaccinia virus proteome: identification of proteins in vaccinia virus intracellular mature virion particles. J. Virol. 80:2127-2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Condit, R. C., N. Moussatche, and P. Traktman. 2006. In a nutshell: structure and assembly of the vaccinia virion. Adv. Virus Res. 66:31-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dyster, L. M., and E. G. Niles. 1991. Genetic and biochemical characterization of vaccinia virus genes D2L and D3R which encode virion structural proteins. Virology 182:455-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grubisha, O., and P. Traktman. 2003. Genetic analysis of the vaccinia virus I6 telomere-binding protein uncovers a key role in genome encapsidation. J. Virol. 77:10929-10942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heuser, J. 2005. Deep-etch EM reveals that the early poxvirus envelope is a single membrane bilayer stabilized by a geodetic “honeycomb” surface coat. J. Cell Biol. 169:269-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hiller, G., and K. Weber. 1982. A phosphorylated basic vaccinia virion polypeptide of molecular weight 11,000 is exposed on the surface of mature particles and interacts with actin-containing cytoskeletal elements. J. Virol. 44:647-657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kao, S. Y., and W. R. Bauer. 1987. Biosynthesis and phosphorylation of vaccinia virus structural protein VP11. Virology 159:399-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kao, S. Y., E. Ressner, J. Kates, and W. R. Bauer. 1981. Purification and characterization of a superhelix binding protein from vaccinia virus. Virology 111:500-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kato, S. E., R. C. Condit, and N. Moussatche. 2007. The vaccinia virus E8R gene product is required for formation of transcriptionally active virions. Virology 367:398-412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kato, S. E., N. Moussatche, S. M. D'Costa, T. W. Bainbridge, C. Prins, A. L. Strahl, A. N. Shatzer, A. J. Brinker, N. E. Kay, and R. C. Condit. 2008. Marker rescue mapping of the combined Condit/Dales collection of temperature-sensitive vaccinia virus mutants. Virology 375:213-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato, S. E., A. L. Strahl, N. Moussatche, and R. C. Condit. 2004. Temperature-sensitive mutants in the vaccinia virus 4b virion structural protein assemble malformed, transcriptionally inactive intracellular mature virions. Virology 330:127-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klemperer, N., J. Ward, E. Evans, and P. Traktman. 1997. The vaccinia virus I1 protein is essential for the assembly of mature virions. J. Virol. 71:9285-9294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]