Abstract

Purpose

Breast cancer chemotherapy decisions in patients ≥ 65 years old (older) are complex because of comorbidity, toxicity, and limited data on patient preference. We examined relationships between preferences and chemotherapy use.

Methods

Older women (n = 934) diagnosed with invasive (≥ 1 cm), nonmetastatic breast cancer from 2004 to 2008 were recruited from 53 cooperative group sites. Data were collected from patient interviews (87% complete), physician survey (93% complete), and charts. Logistic regression and multiple imputation methods were used to assess associations between chemotherapy and independent variables. Chemotherapy use was also evaluated according to the following two groups: indicated (estrogen receptor [ER] negative and/or node positive) and possibly indicated (ER positive and node negative).

Results

Mean patient age was 73 years (range, 65 to 100 years). Unadjusted chemotherapy rates were 69% in the indicated group and 16% in the possibly indicated group. Women who would choose chemotherapy for an increase in survival of ≤ 12 months had 3.9 times (95% CI, 2.4 to 6.3 times; P < .001) higher odds of receiving chemotherapy than women with lower preferences, controlling for covariates. Stronger preferences were seen when chemotherapy could be indicated (odds ratio [OR] = 7.7; 95% CI, 3.8 to 16; P < .001) than when treatment might be possibly indicated (OR = 1.9; 95% CI, 1.0 to 3.8; P = .06). Higher patient rating of provider communication was also related to chemotherapy use in the possibly indicated group (OR = 1.9 per 5-point increase in communication score; 95% CI, 1.4 to 2.8; P < .001) but not in the indicated group (P = .15).

Conclusion

Older women's preferences and communication with providers are important correlates of chemotherapy use, especially when benefits are more equivocal.

INTRODUCTION

Systemic adjuvant chemotherapy is currently recommended for many patients with breast cancer,1 but women age ≥ 65 years (referred to as older here) are less likely to receive chemotherapy than younger women.2–7 This pattern likely reflects the complexity of chemotherapy decision making in older women as the result of a paucity of clinical trial data on efficacy, perceptions of increased toxicity risk,8–14 more favorable tumor characteristics,15 high rates of comorbidities that can interact with treatment,16,17 and decreases in ability to tolerate treatment related to aging processes.18

In situations where the risks and benefits of chemotherapy are equivocal, patient preferences,19–22 physician attitudes,23,24 age biases,6,25 and patient-physician communication26,27 are important in decision making. In this article, we use data from a prospective cohort of older women treated for their breast cancer outside of treatment trials but in a cooperative group setting to examine the associations between patient, clinical, and physician factors in chemotherapy use. We hypothesized that the odds of receiving chemotherapy would be higher for older women with stronger preferences for chemotherapy than for women with lower preferences, controlling for other factors. We also hypothesized that women who reported greater patient-physician communication about treatment would be more likely to receive chemotherapy than women reporting less communication.

METHODS

The study was conducted at 53 Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) sites. The protocol met Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act standards and was approved by the CALGB, the National Cancer Institute, and all institutional review boards.

Setting and Population

We report on older women who were newly diagnosed with breast cancer between January 1, 2004 and March 31, 2008; accrual is ongoing for investigation of follow-up care. Eligible participants were ≥ 65 years old, were diagnosed with invasive nonmetastatic breast cancer (tumors ≥ 1 cm), spoke English or Spanish, had sufficient cognitive function to complete interviews, and were within 20 weeks of their last definitive surgery. In some sites, a treatment trial targeting older women was open for enrollment28; women who enrolled onto that trial were not eligible.

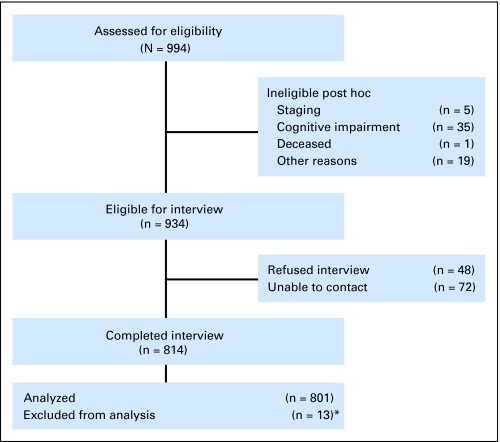

Clinical research associates ascertained patients, confirmed eligibility, approached physicians for permission to contact patients (obtained for 95% of women), and obtained consent. Patient registration was managed by the CALGB Statistical Center. Among consenting patients registered to the study (n = 994), 6.0% (n = 60) were ineligible as a result of cognitive impairment (based on scores of ≥ 11 on the Blessed Orientation-Memory-Concentration test)29,30 or other reasons (Fig 1). Among the remaining 934 eligible women, 87% (n = 814) completed baseline interviews; the final data set includes 801 women. Women who completed interviews were not significantly different from those who did not regarding age, tumor size, and receptor status, except that women who could not be contacted or refused were more likely to be nonwhite than women who completed interviews (19% v 11%, respectively).

Fig 1.

Sampling frame for older women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Flow chart of patient status. Women were registered to the study. Registered women completed interviews, refused, could not be contacted, were found to be ineligible (eg, as a result of cognitive screen failures or being outside of stage criteria), or were lost for administrative reasons. (*) Among the 814 women interviewed, nine had missing data as a result of a computer failure, and four had missing information on chemotherapy status, so that 801 women are included in the final data set. Other reasons for ineligibility included having recurrent cancer or another primary cancer or being beyond 20 weeks of last definitive surgery.

Data Collection

Patient interviews were completed on the telephone by centralized staff and lasted 45 minutes; 0.1% of interviews were in Spanish. Ten percent of interviews were observed for quality assurance purposes. Women were interviewed within an average of 4 weeks of registration and 17 weeks from diagnosis.

Physicians were mailed a brief 15-minute survey of their background and practice styles. If a woman saw a medical oncologist, this provider was selected to receive the survey; if not, we surveyed the surgeon. The 801 patients had 194 physicians, and 180 physicians (93%) completed a survey. Records were abstracted by clinical research associates.

Outcome Variables

The primary outcome was chemotherapy receipt (yes v no), including use of neoadjuvant treatment. Use of chemotherapy was ascertained via patient self-report and records (97.5% concordance κ = .95); final assignment for the few discordant results was based on records.

We defined the following clinical subgroups of women based on practice guidelines1: chemotherapy indicated (any positive nodes and/or estrogen receptor [ER] negative) and chemotherapy possibly indicated (node negative and ER positive). We also examined results using a more stringent definition of indicated as requiring ≥ four positive nodes. We did not have data on human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 status or results of gene expression profiling because these were not used until the end of the study period.31,32

Independent Variables

The key independent variables were patient preference and patient-physician communication. To measure preferences, we used a modified time trade-off approach33,34 to evaluate the amount of benefit women would require to choose chemotherapy in a hypothetical situation. Using a ping-pong response pattern, women were asked the following question: “If you were this…patient, would you agree to chemotherapy if it has a 50/50 chance of adding (5 years…down to one week) to your life?” Choosing chemotherapy for the shortest period of gain (ie, 1 week) indicates the highest preference for chemotherapy, whereas not choosing chemotherapy for even a 5-year gain represents the lowest preference. Because 45% of women indicated that they would choose chemotherapy if it provided ≤ 12 months of life extension, we dichotomized preferences at this threshold.

Perceptions of patient-physician communication were measured using items developed by Makoul et al.35 The seven-item scale includes statements such as, “The doctor fully explained the risks of the treatment recommended” and “The doctor gave me all the information I needed for decisions about my health problem” (α = .79). To evaluate attitudes toward chemotherapy, we used 4-point Likert-scale responses to the following two questions: “You are less likely to have the cancer come back if you have chemotherapy” and “The adverse effects are worse than the disease.”

Among the subset of women who saw a medical or surgical oncologist and reported that chemotherapy was discussed with them, we ascertained whether they were accompanied by another person when chemotherapy was discussed. We included physicians' attitudes toward patient participation in chemotherapy decisions using a previously validated 11-item instrument (α = .84).36,37 In addition, we evaluated decision-making preferences.35

Clinical Variables

Pathologic staging was used to classify tumor size and nodal status. Chemotherapy rates were 24% in women who were node negative and increased to 68%, 56%, 71%, 75%, and more than 88% for women who had one, two, three, four, and ≥ five positive nodes, respectively. Thus, we dichotomized nodal status into positive versus negative for primary analysis. Surgery included mastectomy or breast conservation. Hormone status was measured using ER status. The Older Americans Resources and Services Multidimensional Functional Assessment 16-item physical health scale was used to assess comorbidity.38 Women were dichotomized into the following two groups: those having ≤ two versus those with more than two diseases. Activities of daily living were measured using the Older Americans Resources and Services Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scale39 and categorized into no limitations versus ≥ one limitation. Functional status was based on the physical components score from the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-12.39 Cognition was dichotomized as no impairment (score of 0) versus very mild impairment (score of 1 to 10) based on score distribution; patients with scores ≥11 were excluded.

Controlling Variables

We considered several patient sociodemographic and other factors as potential confounders of the relationships between preferences and/or communication and chemotherapy use. Race/ethnicity was based on self-report and categorized as white and nonwhite. Other demographic variables included age, education (< or ≥ high school), and insurance.

We used two subscales of the Medical Outcomes Study social support instrument to measure perceived availability of emotional/informational support and tangible support.40 Marital status (currently v not married) was another indicator of social support.

Because the timing of the interview could have affected responses, we controlled for the time from diagnosis to the interview. We also controlled for health maintenance organization versus non–health maintenance organization care, National Cancer Institute–designated cancer center versus other, and geographic region. Physician sex and time since medical school graduation were included. Finally, we controlled for the year of diagnosis.

Statistical Analysis

We evaluated the associations between chemotherapy use and study variables using t tests and χ2 tests. Next, we used multiple imputation methods to impute values for missing data; most variables were missing up to 5% of values, and only two variables had 17% missing values (Table 1). IVEware (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI) was used to generate 10 imputed data sets using variables from the data set.41

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Older Patients With Breast Cancer by Chemotherapy Use and Provider Factors

| Characteristic | Total |

Missing Data |

Chemotherapy Use* |

P | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 332) |

No (n = 469) |

||||||||

| No. of Patients | % | No. of Patients | % | No. of Patients | % | No. of Patients | % | ||

| Patient factors | |||||||||

| Age, years | 0 | 0 | < .001 | ||||||

| Mean | 73 | 71 | 75 | ||||||

| Standard deviation | 6.1 | 5.1 | 6.2 | ||||||

| 65-74 | 518 | 65 | 265 | 51 | 253 | 49 | < .001 | ||

| 75-79 | 164 | 20 | 48 | 29 | 116 | 71 | |||

| 80+ | 119 | 15 | 19 | 16 | 100 | 84 | |||

| Race | 0 | 0 | .05 | ||||||

| White | 698 | 87 | 280 | 40 | 418 | 60 | |||

| Nonwhite | 103 | 13 | 52 | 51 | 51 | 49 | |||

| Current marital status | 7 | 1 | .02 | ||||||

| Married or living as married | 417 | 53 | 189 | 45 | 228 | 55 | |||

| Other | 377 | 47 | 141 | 37 | 236 | 63 | |||

| Highest level of education | 32 | 4 | .40 | ||||||

| Less than HS (≤ 12 years) | 345 | 45 | 147 | 43 | 198 | 57 | |||

| HS graduate or higher (> 12 years) | 424 | 55 | 168 | 40 | 256 | 60 | |||

| Insurance | 0 | 0 | .15 | ||||||

| Medicaid | 61 | 8 | 32 | 53 | 29 | 47 | |||

| Private | 616 | 77 | 246 | 40 | 370 | 60 | |||

| Medicare Only | 124 | 15 | 54 | 44 | 70 | 56 | |||

| Preference | 39 | 5 | < .001 | ||||||

| Low (> 12-month gain) | 417 | 55 | 116 | 28 | 301 | 72 | |||

| High (≤ 12-month gain) | 345 | 45 | 211 | 61 | 134 | 39 | |||

| Attitude: less likely to have the cancer come back if you have chemotherapy | 140 | 17 | < .001 | ||||||

| Very much | 243 | 37 | 174 | 72 | 69 | 28 | |||

| Somewhat | 245 | 37 | 100 | 41 | 145 | 59 | |||

| Very little | 59 | 9 | 12 | 22 | 47 | 80 | |||

| Not at all | 114 | 17 | 27 | 24 | 87 | 76 | |||

| Attitude: adverse effects of chemotherapy are worse than the disease | 137 | 17 | < .001 | ||||||

| Not at all | 203 | 30 | 128 | 63 | 75 | 37 | |||

| Very little | 134 | 20 | 79 | 59 | 55 | 41 | |||

| Somewhat | 223 | 34 | 72 | 32 | 151 | 68 | |||

| Very much | 104 | 16 | 27 | 26 | 77 | 74 | |||

| Provider factors | |||||||||

| Years since medical school graduation (to 2007) | 21 | 8.1 | 31 | 4 | 20 | 8.1 | 21 | 8.0 | .02 |

| Provider sex | 0 | 0 | .14 | ||||||

| Female | 371 | 46 | 164 | 44 | 207 | 56 | |||

| Male | 430 | 54 | 168 | 39 | 262 | 61 | |||

| Patient-provider interactions | |||||||||

| Perceptions of patient-provider communication, score† | 95 | 12 | < .001 | ||||||

| Mean | 30 | 31 | 28 | ||||||

| Standard deviation | 5.0 | 4.9 | 4.8 | ||||||

| Saw a medical oncologist | 15 | 2 | .09 | ||||||

| Yes | 747 | 95 | 314 | 42 | 433 | 58 | |||

| No | 39 | 5 | 11 | 28 | 28 | 72 | |||

| Clinical factors | |||||||||

| Tumor size, cm | 1 | 0.1 | < .001 | ||||||

| < 2 cm (T1) | 460 | 58 | 145 | 32 | 315 | 69 | |||

| 2 to < 3 cm (T2) | 195 | 24 | 92 | 47 | 103 | 53 | |||

| ≥ 3 cm (T3) | 145 | 18 | 94 | 64 | 51 | 35 | |||

| Nodal status | 0 | 0 | < .001 | ||||||

| Positive | 300 | 37 | 214 | 71 | 86 | 29 | |||

| Negative | 501 | 63 | 118 | 24 | 383 | 76 | |||

| Estrogen receptor status | 2 | 0.2 | < .001 | ||||||

| Negative | 141 | 18 | 108 | 79 | 33 | 29 | |||

| Positive | 658 | 82 | 223 | 34 | 383 | 76 | |||

| Clinical indications | 2 | 0.2 | < .001 | ||||||

| Indicated | 379 | 47 | 263 | 69 | 116 | 31 | |||

| Possibly indicated | 420 | 53 | 68 | 16 | 352 | 84 | |||

| Most extensive primary surgery | 3 | 0.4 | < .001 | ||||||

| Mastectomy | 248 | 31 | 135 | 54 | 113 | 46 | |||

| Breast conservation | 550 | 69 | 196 | 36 | 354 | 64 | |||

| Comorbidity score (OARS) | 1 | 0.1 | < .001 | ||||||

| 0-2 | 348 | 43 | 170 | 49 | 178 | 51 | |||

| > 2 | 452 | 57 | 161 | 36 | 291 | 64 | |||

| Cognitive function score (Blessed test) | 0 | 0 | .12 | ||||||

| Perfect score | 389 | 49 | 172 | 44 | 217 | 56 | |||

| ≥ 1 error | 412 | 51 | 160 | 39 | 252 | 61 | |||

| Physical function (PCS)‡ | 59 | 7 | .01 | ||||||

| Mean | 52 | 52 | 51 | ||||||

| Standard deviation | 7.1 | 6.8 | 7.3 | ||||||

| Setting of care | |||||||||

| HMO | 53 | 7 | .24 | ||||||

| Yes | 130 | 17 | 59 | 45 | 71 | 55 | |||

| No | 618 | 83 | 246 | 40 | 372 | 60 | |||

| NCI-designated cancer center | 0 | 0 | .07 | ||||||

| Yes | 254 | 32 | 117 | 46 | 137 | 54 | |||

| No | 547 | 68 | 215 | 39 | 332 | 61 | |||

| No. of patients per site | 0 | 0 | .001 | ||||||

| Mean | 57 | 65 | 51 | ||||||

| Standard deviation | 56 | 64 | 50 | ||||||

NOTE. All variables were used in multiple imputations together with living situation, caretaker, home ownership, religious/spiritual help, decision-making style, Medical Outcomes Study emotional and tangible support, physician attitude toward patient participation, axillary dissection, impairment in activities of daily living function, months from diagnosis to interview, year of diagnosis, region, and chemotherapy use.

Abbreviations: HS, high school; OARS, Older Americans Resources and Services; PCS, physical component score; HMO, health maintenance organization; NCI, National Cancer Institute.

Chemotherapy was defined as any systemic regimen, including neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapies, based on responses to baseline and 6-month interview. Indicated chemotherapy includes women with any positive nodes and/or those with estrogen receptor–negative tumors; possibly indicated chemotherapy includes all other women. Only 11 women (1.4%) were enrolled onto a clinical treatment trial.

Perceptions of communication score ranges from 7 to 42, with higher scores representing perceptions of best communication.

PCS ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing better physical function.

We used logistic regression to model chemotherapy use. Variable selection was based on the significance (P = .05 level) of univariate associations with chemotherapy; variables that were not significant in the final model were removed. However, factors included in a priori hypotheses or having face validity (eg, race, region) were retained even if not significant. The estimates from the logistic regression models corresponding to the 10 imputed data sets were combined according to the method of Rubin.42 We also used logistic regression models with generalized estimating equations to account for the potential clustering of chemotherapy use by accrual site or by physician. Because the results were similar, we report only the results from the logistic regression models. We also constructed regression models among the subset of women with complete data for all variables. The results were similar, so we report the imputation-based results. Last, we tested for possible interactions between the main predictors and strength of indications for chemotherapy. Because interactions were present, we conducted stratified analyses by whether chemotherapy was indicated or possibly indicated. We report C statistics for the logistic regression models; pseudo-R2 values were also calculated to estimate the percentage of variance in chemotherapy use explained by the models.

RESULTS

Use of chemotherapy was significantly associated with several patient, clinical, and provider factors in univariate analyses (Table 1). On the basis of hormone receptor and nodal status, chemotherapy was indicated for 47% and was possibly indicated for 53% of the cohort. Unadjusted chemotherapy rates were 69% (95% CI, 65% to 74%) in the indicated group and 16% (95% CI, 13% to 20%) in the possibly indicated group, for an overall rate of 42% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Rates of Chemotherapy Use in Older Women by Clinical Subgroup

| Chemotherapy Use | Chemotherapy Possibly Indicated (n = 420) ER Positive, Node Negative | Chemotherapy Indicated (n = 379)* |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER Positive, Node Positive | ER Negative |

|||

| Node Negative | Node Positive | |||

| No. of patients | 420 | 238 | 79 | 62 |

| Received chemotherapy, % | 16 | 65 | 63 | 94 |

| 95% CI | 13 to 20 | 59 to 71 | 52 to 72 | 91 to 97 |

NOTE. Chemotherapy was defined as any systemic regimen, including neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapies, based on medical record audits at registration and the 6-month follow-up. Two women are excluded as a result of missing hormonal receptor status. Among the 318 women who received chemotherapy and had available chemotherapy dates, 16 (5%) received this modality as neoadjuvant treatment. The unadjusted overall rate of chemotherapy was 42% (95% CI, 38% to 45%).

Abbreviation: ER, estrogen receptor.

The unadjusted overall rate of chemotherapy for the three subgroups of the indicated group was 69% (95% CI, 65% to 74%).

In the regression model, tumor factors (ie, tumor size, nodal status, and ER status) were strongly associated with chemotherapy use. Preferences were also significantly associated with chemotherapy (Table 3). Women who would choose chemotherapy for an increase in survival of ≤ 12 months (high preference) were 3.9 times (95% CI, 2.4 to 6.3 times; P < .001) more likely to receive chemotherapy than women who would only choose chemotherapy if it added more than 12 months (low preference), controlling for covariates. Ratings of patient-physician communication were also related to chemotherapy, with women who rated communication most highly having higher odds of receiving chemotherapy than women who rated communication less favorably (odds ratio [OR] = 1.6 per 5-point increase in communication score; 95% CI, 1.2 to 2.0; P < .001). Younger patient age was also significantly associated with chemotherapy use. Overall, the variables included explained 68% of the variance in chemotherapy use; the majority of explained variance was accounted for by tumor factors (41%); 12% was explained by age, and 4% was explained by communication and preferences. When we considered women separately by clinical indications for chemotherapy, the effects of age and other variables were similar across the two groups. However, we saw higher associations between high (v low) preferences and chemotherapy among women with indications for chemotherapy (OR = 7.7; 95% CI, 3.8 to 16; P < .001) than among women in whom it was possibly indicated (OR = 1.9; 95% CI, 1.0 to 3.8; P = .06; Table 3; P for interaction = .004). Also, higher patient rating of communication was related to chemotherapy use among the possibly indicated group (OR = 1.9; 95% CI, 1.4 to 2.8; P < .001) but not among the indicated group (OR = 1.3; 95% CI, 0.9 to 1.9; P = .15), although this was not statistically significant (P for interaction = .12). These relationships were qualitatively similar when we defined indicated as having four or more nodes among ER-positive women. However, the OR for preferences was of greater magnitude in the possibly indicated group of women (< four nodes or node negative) than before (node negative), suggesting that as the choice became more equivocal, utilities played more of a role in chemotherapy use (data not shown).

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds of Receiving Chemotherapy in Older Women With Breast Cancer

| Factor | Overall (N = 799) |

Chemotherapy Indicated (n = 379) |

Chemotherapy Possibly Indicated (n = 420) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | |

| Preference: ≤ v > 12 months | 3.9 | 2.4 to 6.3 | < .001 | 7.7 | 3.8 to 16 | < .001 | 1.9 | 0.97 to 3.8 | .06 |

| Communication score: 5-point increase | 1.6 | 1.2 to 2.0 | < .001 | 1.3 | 0.9 to 1.9 | .15 | 1.9 | 1.4 to 2.8 | < .001 |

| You are less likely to have the cancer come back if you have chemotherapy: agree v disagree | 5.4 | 2.9 to 10 | < .001 | 5.7 | 2.5 to 13 | < .001 | 4.8 | 1.8 to 13 | .002 |

| The adverse effects are worse than the disease: agree v disagree | 0.3 | 0.2 to 0.5 | < .001 | 0.2 | 0.1 to 0.5 | < .001 | 0.3 | 0.2 to 0.7 | .003 |

| Tumor size | |||||||||

| 2-2.9 v < 2 cm | 2.4 | 1.4 to 4.1 | .002 | 1.8 | 0.8 to 4.0 | .13 | 3.2 | 1.5 to 6.9 | .003 |

| ≥ 3 v < 2 cm | 3.5 | 1.8 to 6.7 | < .001 | 4.5 | 1.9 to 11 | .001 | 2.5 | 0.9 to 7.2 | .09 |

| Nodal status: positive v negative | 17 | 9.7 to 28 | < .001 | ||||||

| ER status: positive v negative | 0.1 | 0.1 to 0.3 | < .001 | ||||||

| OARS: > 2 v 0-2 | 0.7 | 0.5 to 1.1 | .16 | 0.8 | 0.4 to 1.6 | .61 | 0.7 | 0.4 to 1.3 | .27 |

| Surgery: mastectomy v conservation | 1.9 | 1.1 to 3.2 | .01 | 3.7 | 1.7 to 8.0 | .001 | 0.9 | 0.4 to 2.0 | .84 |

| Cognitive function: ≥ 1 error v perfect score | 0.9 | 0.6 to 1.4 | .64 | 0.9 | 0.5 to 1.8 | .80 | 0.9 | 0.5 to 1.8 | .80 |

| Age: 5-year increase | 0.5 | 0.4 to 0.6 | < .001 | 0.4 | 0.3 to 0.6 | < .001 | 0.5 | 0.4 to 0.7 | < .001 |

NOTE. Controlling for race, time from diagnosis to interview, diagnosis year, region, and years from provider medical school graduation in the table was performed using logistic regression models. Results are based on 10 multiple imputed data sets. Chemotherapy was defined as any systemic regimen, including neoadjuvant therapy, based on medical records. Indicated includes women with any positive nodes and/or those with ER-negative tumors; possibly indicated includes all other women. Two women missing ER status are excluded. Women (n = 40, 4.9%) who gave “unsure” as a response for preferences were coded as missing. Results including these women and imputing their results or excluding them were similar, so they were included in final models.

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; ER, estrogen receptor; OARS, Older Americans Resources and Services.

Among the subset of 509 women who stated that they saw an oncologist and discussed chemotherapy, 67% who had a companion accompany them received chemotherapy compared with 45% who were not accompanied. In multivariable analysis, the odds of chemotherapy were 2.1 times higher (95% CI, 1.2 to 3.7 times; P = .01) among women who were accompanied (v not) after adjusting for age, clinical factors, comorbidity, and cognition.

DISCUSSION

In this cohort of older breast cancer patients, we demonstrate that chemotherapy use varies by clinical indications and confirmed that age is associated with decreasing chemotherapy use.2,3,5 We also find that having a stronger preference for chemotherapy is associated with greater odds of receiving chemotherapy. Furthermore, we observe that when chemotherapy indications are less strong, higher ratings of physician-patient communication are an important determinant of use. Of interest, we also found that patients who were accompanied to visits were more likely to receive chemotherapy than those attending alone.

In this study, 42% of women received chemotherapy, a rate that is higher than what is observed in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results–Medicare data set; Du and Goodwin2 reported rates of chemotherapy in older patients with breast cancer of approximately 11% in the early 1990s, and rates have been increasing over time in this age group.43–45 However, within clinical subgroups, our rates are more similar to prior reports. For instance, we found a 16% rate among women with node-negative, ER-positive tumors, which is greater than the 5% rate reported by Du Du and Goodwin2 for similar patients diagnosed a decade earlier. Higher chemotherapy rates were found by us and others in women with nodal involvement or negative hormone receptors.2,43

The observation that patient preferences are more strongly associated with chemotherapy among older women with the greatest indications also suggests that older women are appropriately judging the benefit-to-risk ratio of chemotherapy. This is similar to the findings of Zimmermann et al,46 who found that chemotherapy preferences increase as the benefits presented increase. The preference cut point of ≤ 12 months of gain from chemotherapy in our sample corresponds to the expected benefit based on extrapolation of clinical trials.8 In a review conducted by Duric and Stockler,47 this same cut point was considered sufficient to undergo chemotherapy by 74% of women. In several other studies, older breast cancer patients are willing to select chemotherapy with major toxicity for similar increases in life expectancy.34,48–51 The strength of the physician recommendation has been found to be a determinant of the strength of patients' preferences for chemotherapy.19 Taken together, these results suggest that women's preferences reflect a good understanding of their disease as conveyed by their physicians.

In situations where chemotherapy could be possibly indicated, women reporting greater communication are more likely to undergo chemotherapy than women reporting less communication. However, we do not know the content of actual communication about treatment. Follow-up research using transcripts of encounters could be used to understand this result more fully. In other settings, good communication is associated with higher satisfaction with care and treatment choices and better quality of life.27,52

In our study, it appears that women who had a companion present during consultations were more likely to receive chemotherapy. This result was unexpected and may be related to several factors, including the influence of family on decisions, the presence of social support, help in recording and processing information, greater need for concrete support related to disease severity, or the influence of a third person on the interaction. Several investigators have noted that companions affect the dynamic of medical encounters by facilitating communication, asking clarifying questions, and bridging barriers.53–55 In other research, Wolff and Roter56 found that older individuals who were accompanied to visits were older and sicker than those attending alone. In an Italian study with older patients receiving chemotherapy, 79% indicated that they desired having a family member present during consultations.57 Thus, there are several alternative explanations for our result. This will be an important area for additional research. In the interim, our results suggest that there may be several routes for improving communication, including the presence of a third person or providing a written or audiotape summary of the visit.

There are several caveats that should be considered in evaluating our results. Although the study was designed to measure preferences before oncology consultations, this was not always feasible given the large number of sites and variable staffing. Our results suggest that preferences were based on realistic appraisals of risks and benefits. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that actual treatment affected ratings of preference.58,59

We analyzed results by level of clinical indication for chemotherapy based on the data we had available. We recognize that more refined measures of recurrence risk have recently come into practice (eg, Oncotype DX, Genomic Health, Redwood City, CA; MammaPrint, Agendia, Huntington Beach, CA)31,60 and that we did not have data on tumor grade or human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 status. We also did not have data on actual treatment recommendation by clinicians, including whether physicians judged chemotherapy to be indicated or possibly indicated for a particular patient.

This cohort includes women treated for their cancer in settings that participate in cooperative trial research. Our sample had a greater proportion of poor prognosis tumors than older women in the general population, suggesting referral bias. Also, nearly all women in the study reported seeing an oncologist, reflecting either the institutional culture or how patients were ascertained. Seeing an oncologist is a strong predictor of treatment.61 These factors limit the external generalizability of our results, although internal comparisons are valid. Finally, although the racial/ethnic breakdown of the sample is representative of older patients seen at participating sites and their proportions in the older US breast cancer population,62 the absolute number of minorities is too small for separate analysis. It will be important to enhance minority recruitment in our ongoing accrual efforts.

This is one of the largest primary observational data sets of older women to examine determinants of chemotherapy use in the United States.63 The detailed data available may help explain some of the patterns of care observed in secondary data sets such as the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results–Medicare data set. This study indicates that older women's preferences and communication with providers are important correlates of chemotherapy use, especially when benefits are more equivocal. These results suggest that physicians can enhance the care of the growing population of older patients with breast cancer through assessment of and communication about chemotherapy risks and benefits and consideration of women's preferences.17,26,64–66

Acknowledgment

We gratefully acknowledge the women who participated in the OPTIONS study and shared so generously of their time and experiences. In addition, we acknowledge the clinical research associates at the study sites who enrolled patients and submitted clinical data; without them, the study would not have been possible.

We acknowledge Kayla Landers and Trina McClendon for their work interviewing the patients for this study and Bin Yi for database support. We also appreciate the physicians who took the time to complete a survey for this project.

We also acknowledge Edie Fitts, advocate, the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) Statistical Center (John Postiglione, Peggy Edwards, and Lydia Hodgson) and CALGB Central Office staff who supported this protocol (Kathy Karas, Sara Hoffman, Mary Sherrell, Avis Rodgers, and Donna Johnson).

We acknowledge Bercedes Peterson for review of earlier versions of the statistical plan.

We acknowledge Jackie Ford for assistance with manuscript preparation.

We are grateful to the following principal investigators for protocol #369901 at the CALGB sites for facilitating patient recruitment: Rafat Ansari: Elkhart General Hospital, Lakeland Hospital, Memorial Hospital of South Bend, Northern Indiana Cancer Research Consortium, St Joseph Regional Medical Center; Blair Ardman: Lowell General Hospital; Kamal M. Bakri: Cape Fear Valley Health System; Bharat Barai: Premier Oncology Hematology Associates; Clara D. Bloomfield: The Ohio State University Medical Center; Harold J. Burstein: Dana-Farber Cancer Institute; Martin Bury: Hackley Hospital, Saint Mary's Health Care, Spectrum Health; Donald Busiek: St Luke's Hospital; Charles Catcher: Lakes Region General Healthcare; Michael Constantine: Milford Regional Medical Center; Mehmet S. Copur: Saint Francis Medical Center; Jeffrey Crawford: Duke University Health System; Konstantin Dragnev: Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center; Stephen Edge: Roswell Park Cancer Institute; John A. Ellerton: Nevada Cancer Research Foundation; Gini Fleming: University of Chicago; Rolph Freter: South Shore Hospital; Steven M. Grunberg: University of Vermont; James Hannigan: Adventist La Grange Memorial Hospital; Tamara Hopkins: Capital Region Medical Center; Clifford A. Hudis: Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center; David Hurd: Wake Forest University Health Sciences; Arti Hurria: Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center; Renee Jacobs: Adventist La Grange Memorial Hospital; Peter Kaufman: Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center; Anne Kessinger: University of Nebraska Medical Center; Gerrit Kimmey: St Mary's Medical Center; Gretchen Kimmick: Wake Forest Health Sciences; Hedy L. Kindler: University of Chicago; Jeffrey Kirshner: Hematology Oncology Associates of Central New York; Alice Kornblith: Dana-Farber Cancer Institute; Diana Lake: Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Ralph Lauren Center for Cancer Care and Prevention; Marianne Lange: Grand Rapids Clinical Oncology Program; Ellis Levine: Roswell Park Cancer Institute; David Lovett: Cape Cod Hospital; Angus McIntyre: Northeast Hospital Corporation–Addison Gilbert Hospital; R. William Morris: St Anthony's Medical Center; Hyman Muss: University of Vermont; Michael Naughton: Washington University in St Louis; Yvonne Ottaviano: Franklin Square Hospital Center; David Palchak: University of California San Diego Medical Center/Arroyo Grande Community Hospital; Barbara A. Parker: University of California San Diego Medical Center/Arroyo Grande Community Hospital; Leroy Parker: Norwood Hospital; Electra Paskett: The Ohio State University Medical Center; Michael Perry: University of Missouri/Ellis Fischel Cancer Center; John Posner: St Joseph Hospital; Elizabeth Reed: University of Nebraska Medical Center; Thomas Reid: Walter Reed Army Medical Center; Keith Shulman: Louis A. Weiss Memorial Hospital; Danny Sims: Exeter Hospital; Sankaravadivu Sivasailam: Upper Chesapeake Medical Center; Karen Smith: Washington Cancer Institute at Washington Hospital; Carol A. Vasconcellos: Sturdy Memorial Hospital; Irfan Vaziri: Great Plains Regional Medical Center; Mary Voltz: St Joseph Hospital; Douglas Weckstein: Elliot Hospital; Douglas Weinstein: New Hampshire Oncology-Hematology PA; Brendan Weiss: Walter Reed Army Medical Center; Tracey Weisberg: Maine Center for Cancer Medicine & Blood Disorders; Ellen Willard: FirstHealth of the Carolinas Moore Regional Hospital; Eric Winer: Dana-Farber Cancer Institute; Marie Wood: University of Vermont; and Robin Zon: Elkhart General Hospital, Lakeland Hospital, Memorial Hospital of South Bend, Northern Indiana Cancer Research Consortium, St Joseph Regional Medical Center.

Supported in part by National Cancer Institute (NCI) Grants No. CA31946 (Cancer and Leukemia Group B [CALGB]), CA33601 (CALGB Statistical Center), U10 CA84131 (J.S.M. and V.B.S.), RO1 CA124924 (J.S.M.), RO1 CA 127617 (J.S.M.), and KO5 CA96940 (J.S.M.); American Cancer Society Grant No. MRSGT-06-132-01-CPPB (V.B.S.); and CALGB Cooperative Group Grant No. U10 CA31946. Also supported by the Clinical and Molecular Epidemiology and Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Shared Resources at Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center under NCI Grant No. P30CA51008, a grant from Amgen Pharmaceuticals to the CALGB Foundation, and Grant No. P30AG028716 from the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Centers, National Institute on Aging (H.J.C.).

Appendix

The following institutions participated in this study: Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA–Eric P. Winer, MD, supported by CA32291; Dartmouth Medical School, Norris Cotton Cancer Center, Lebanon, NH–Marc S. Ernstoff, MD, supported by CA04326; Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC–Jeffrey Crawford, MD, supported by CA47577; Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, DC–Minetta C. Liu, MD, supported by CA77597; Grand Rapids Clinical Oncology Program, Grand Rapids, MI–Marianne Lange, MD, supported by CA035178; Hematology-Oncology Associates of Central New York Community Clinical Oncology Program (CCOP), Syracuse, NY–Jeffrey Kirshner, MD, supported by CA45389; Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY–Clifford A. Hudis, MD, supported by CA77651; Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY–Lewis R. Silverman, MD, supported by CA04457; Nevada Cancer Research Foundation CCOP, Las Vegas, NV–John A. Ellerton, MD, supported by CA35421; New Hampshire Oncology-Hematology PA, Concord, NH–Douglas J. Weckstein; Northern Indiana Cancer Research Consortium CCOP, South Bend, IN–Rafat Ansari, MD, supported by CA86726; Rhode Island Hospital, Providence, RI–William Sikov, MD, supported by CA08025; Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY–Ellis Levine, MD, supported by CA02599; The Ohio State University Medical Center, Columbus, OH–Clara D Bloomfield, MD, supported by CA77658; University of California at San Diego, San Diego, CA–Barbara A. Parker, MD, supported by CA11789; University of Chicago, Chicago, IL–Gini Fleming, MD, supported by CA41287; University of Maryland Greenebaum Cancer Center, Baltimore, MD–Martin Edelman, MD, supported by CA31983; University of Missouri/Ellis Fischel Cancer Center, Columbia, MO–Michael C. Perry, MD, supported by CA12046; University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE–Anne Kessinger, MD, supported by CA77298; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC–Thomas C. Shea, MD, supported by CA47559; University of Vermont, Burlington, VT–Hyman B. Muss, MD, supported by CA77406; Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC–David D. Hurd, MD, supported by CA03927; Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Washington, DC–Thomas Reid, MD, supported by CA26806; and Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, MO–Nancy Bartlett, MD, supported by CA77440.

Footnotes

Written on behalf of the Cancer Leukemia Group B.

Information regarding funding for this study can be found in the full-text version of this article, at www.jco.org.

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: Arti Hurria, Amgen (C); Gretchen Kimmick, AstraZeneca (C), Pfizer (C), Novartis (C) Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: Gretchen Kimmick, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Novartis; Claudine Isaacs, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Genentech Research Funding: Arti Hurria, Abraxis BioScience, Pfizer; Gretchen Kimmick, AstraZeneca; Claudine Isaacs, Bayer Pharmaceuticals Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Jeanne S. Mandelblatt, Claudine Isaacs, Kathryn L. Taylor, Alice B. Kornblith, Michelle Tallarico, Harvey Jay Cohen, Hyman Muss

Administrative support: Jeanne S. Mandelblatt, Michelle Tallarico, Lisa Hunegs, Eric Winer, Clifford Hudis, Harvey Jay Cohen, Hyman Muss

Provision of study materials or patients: Arti Hurria, Gretchen Kimmick, Alice B. Kornblith, Robin Zon, Michael Naughton, Eric Winer, Clifford Hudis, Stephen B. Edge, Hyman Muss

Collection and assembly of data: Jeanne S. Mandelblatt, Vanessa B. Sheppard, Alice B. Kornblith, Anne-Michelle Noone, Gheorghe Luta, Michelle Tallarico, William T. Barry, Lisa Hunegs

Data analysis and interpretation: Jeanne S. Mandelblatt, Vanessa B. Sheppard, Claudine Isaacs, Kathryn L. Taylor, Anne-Michelle Noone, Gheorghe Luta, William T. Barry

Manuscript writing: Jeanne S. Mandelblatt, Arti Hurria, Gretchen Kimmick, Claudine Isaacs, Kathryn L. Taylor, Alice B. Kornblith, Anne-Michelle Noone, Gheorghe Luta, Lisa Hunegs, Eric Winer, Clifford Hudis, Stephen B. Edge, Harvey Jay Cohen, Hyman Muss

Final approval of manuscript: Jeanne S. Mandelblatt, Vanessa B. Sheppard, Arti Hurria, Gretchen Kimmick, Claudine Isaacs, Kathryn L. Taylor, Alice B. Kornblith, Anne-Michelle Noone, Gheorghe Luta, Michelle Tallarico, William T. Barry, Lisa Hunegs, Robin Zon, Michael Naughton, Eric Winer, Clifford Hudis, Stephen B. Edge, Harvey Jay Cohen, Hyman Muss

REFERENCES

- 1.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology v. 2.2008. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Du X, Goodwin JS. Patterns of use of chemotherapy for breast cancer in older women: Findings from Medicare claims data. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1455–1461. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.5.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Du XL, Key CR, Osborne C, et al. Discrepancy between consensus recommendations and actual community use of adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:90–97. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-2-200301210-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giordano SH, Hortobagyi GN, Kau SW, et al. Breast cancer treatment guidelines in older women. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:783–791. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeMichele A, Putt M, Zhang Y, et al. Older age predicts a decline in adjuvant chemotherapy recommendations for patients with breast carcinoma: Evidence from a tertiary care cohort of chemotherapy-eligible patients. Cancer. 2003;97:2150–2159. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woodard S, Nadella PC, Kotur L, et al. Older women with breast carcinoma are less likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy: Evidence of possible age bias? Cancer. 2003;98:1141–1149. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Owusu C, Lash TL, Silliman RA. Effect of undertreatment on the disparity in age-related breast cancer-specific survival among older women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;102:227–236. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9321-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: An overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;365:1687–1717. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66544-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muss HB, Woolf S, Berry D, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy in older and younger women with lymph node-positive breast cancer. JAMA. 2005;293:1073–1081. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.9.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crivellari D, Bonetti M, Castiglione-Gertsch M, et al. Burdens and benefits of adjuvant cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil and tamoxifen for elderly patients with breast cancer: The International Breast Cancer Study Group Trial VII. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1412–1422. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.7.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitka M. Too few older patients in cancer trials: Experts say disparity affects research results and care. JAMA. 2003;290:27–28. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kemeny MM, Peterson BL, Kornblith AB, et al. Barriers to clinical trial participation by older women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2268–2275. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis JH, Kilgore ML, Goldman DP, et al. Participation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1383–1389. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hutchins LF, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, et al. Under-representation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:2061–2067. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912303412706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gennari R, Curigliano G, Rotmensz N, et al. Breast carcinoma in elderly women: Features of disease presentation, choice of local and systemic treatments compared with younger postmenopasual patients. Cancer. 2004;101:1302–1310. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yancik R, Wesley MN, Ries LA, et al. Effect of age and comorbidity in postmenopausal breast cancer patients aged 55 years and older. JAMA. 2001;285:885–892. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.7.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Extermann M, Balducci L, Lyman GH. What threshold for adjuvant therapy in older breast cancer patients? J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1709–1717. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.8.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carlson RW, Moench S, Hurria A, et al. NCCN Task Force Report: Breast cancer in the older woman. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2008;6(suppl 4):S1–S25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yellen SB, Cella DF, Leslie WT. Age and clinical decision making in oncology patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:1766–1770. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.23.1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jansen SJ, Otten W, van de Velde CJ, et al. The impact of the perception of treatment choice on satisfaction with treatment, experienced chemotherapy burden and current quality of life. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:56–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duric VM, Stockler MR, Heritier S, et al. Patients' preferences for adjuvant chemotherapy in early breast cancer: What makes AC and CMF worthwhile now? Ann Oncol. 2005;16:1786–1794. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duric VM, Butow PN, Sharpe L, et al. Psychosocial factors and patients' preferences for adjuvant chemotherapy in early breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2007;16:48–59. doi: 10.1002/pon.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burns RB, Freund KM, Moskowitz MA, et al. Physician characteristics: Do they influence the evaluation and treatment of breast cancer in older women? Am J Med. 1997;103:263–269. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mandelblatt JS, Berg CD, Meropol NJ, et al. Measuring and predicting surgeons' practice styles for breast cancer treatment in older women. Med Care. 2001;39:228–242. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200103000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kornblith AB, Kemeny M, Peterson BL, et al. Survey of oncologists' perceptions of barriers to accrual of older patients with breast carcinoma to clinical trials. Cancer. 2002;95:989–996. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leighl N, Gattellari M, Butow P, et al. Discussing adjuvant cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1768–1778. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.6.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang W, Burnett CB, Rowland JH, et al. Communication between physicians and older women with localized breast cancer: Implications for treatment and patient satisfaction. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1008–1016. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.4.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muss HB, Berry DA, Cirrincione CT, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2055–2065. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis PB, Morris JC, Grant E. Briefing screening tests versus clinical staging in senile dementias of the Alzheimer type. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38:129–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb03473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawas C, Karagiozis H, Resau L, et al. Reliability of the Blessed Telephone Information-Memory-Concentration test. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1995;8:238–242. doi: 10.1177/089198879500800408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paik S, Shak S, Tang G, et al. A multigene assay to predict recurrence of tamoxifen-treated, node-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2817–2826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves new genetic test for patients with breast cancer. http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2008/NEW01857.html.

- 33.Froberg DG, Kane RL. Methodology for measuring health-state preferences: II. Scaling methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 1989;42:459–471. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(89)90136-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McQuellon RP, Muss HB, Hoffman SL, et al. Patient preferences for treatment of metastatic breast cancer: A study of women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:858–868. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.4.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Makoul G, Arntson P, Schofield T. Health promotion in primary care: Physician-patient communication and decision making about prescription medications. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41:1241–1254. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00061-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liberati A, Patterson WB, Biener L, et al. Determinants of physicians preferences for alternative treatments in women with early breast cancer. Tumori. 1987;73:601–609. doi: 10.1177/030089168707300609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liberati A, Apolone G, Nicolucci A, et al. The role of attitudes, beliefs, and personal characteristics of Italian physicians in the surgical treatment of early breast cancer. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:38–42. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fillenbaum GG, Smyer MA. The development, validity, and reliability of the OARS multidimensional functional assessment questionnaire. J Gerontol. 1981;36:428–434. doi: 10.1093/geronj/36.4.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raghunathan T, Lepkowski JM, Van Hoewyk J, et al. A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Stat Can. 2001;27:85–95. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rubin D. Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elkin EB, Hurria A, Mitra N, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy and survival in older women with hormone receptor-negative breast cancer: Assessing outcome in a population-based, observational cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2757–2764. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Giordano SH, Duan Z, Kuo YF, et al. Use and outcomes of adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2750–2756. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harlan LC, Clegg LX, Abrams J, et al. Community-based use of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early-stage breast cancer: 1987-2000. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:872–877. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.5840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zimmermann C, Baldo C, Molino A. Framing of outcome and probability of recurrence: Breast cancer patients' choice of adjuvant chemotherapy (ACT) in hypothetical patient scenarios. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2000;60:9–14. doi: 10.1023/a:1006342316373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duric V, Stockler M. Patients' preferences for adjuvant chemotherapy in early breast cancer: A review of what makes it worthwhile. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:691–697. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00559-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yellen SB, Cella DF. Someone to live for: Social well-being, parenthood status, and decision-making in oncology. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1255–1264. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.5.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goldhirsch A, Gelber RD, Simes RJ, et al. Costs and benefits of adjuvant therapy in breast cancer: A quality-adjusted survival analysis. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:36–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1989.7.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Slevin ML, Stubbs L, Plant HJ, et al. Attitudes to chemotherapy: Comparing views of patients with cancer with those of doctors, nurses, and the general public. BMJ. 1990;300:1458–1460. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6737.1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ravdin PM, Siminoff IA, Harvey JA. Survey of breast cancer patients concerning their knowledge and expectations of adjuvant therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:515–521. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clough-Gorr KM, Ganz PA, Silliman RA. Older breast cancer survivors: Factors associated with change in emotional well-being. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1334–1340. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.8665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clayman ML, Roter D, Wissow LS, et al. Autonomy-related behaviors of patient companions and their effect on decision-making activity in geriatric primary care visits. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:1583–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ishikawa H, Roter DL, Yamazaki Y, et al. Physician-elderly patient-companion communication and roles of companions in Japanese geriatric encounters. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:2307–2320. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Street RL, Jr, Gordon H, Haidet P. Physicians' communication and perceptions of patients: Is it how they look, how they talk, or is it just the doctor? Soc Sci Med. 2007;65:586–598. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wolff JL, Roter DL. Hidden in plain sight: Medical visit companions as a resource for vulnerable older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1409–1415. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.13.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Repetto L, Piselli P, Raffaele M, et al. Communicating cancer diagnosis and prognosis: When the target is the elderly patient—A GIOGer study. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:374–383. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jansen SJ, Otten W, Baas-Thijssen MC, et al. Explaining differences in attitude toward adjuvant chemotherapy between experienced and inexperienced breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6623–6630. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jansen SJ, Stiggelbout AM, Nooij MA, et al. Response shift in quality of life measurement in early-stage breast cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Qual Life Res. 2000;9:603–615. doi: 10.1023/a:1008928617014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Straver ME, Glas AM, Hannemann J, et al. The 70-gene signature as a response predictor for neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;119:551–558. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Ayanian JZ, et al. Consultation with a medical oncologist before surgery and type of surgery among elderly women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4532–4539. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smigal C, Jemal A, Ward E, et al. Trends in breast cancer by race and ethnicity: Update 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:168–183. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.3.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mustacchi G, Cazzaniga ME, Pronzato P, et al. Breast cancer in elderly women: A different reality? Results from the NORA study. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:991–996. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Girre V, Falcou MC, Gisselbrecht M, et al. Does a geriatric oncology consultation modify the cancer treatment plan for elderly patients? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:724–730. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.7.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hurria A, Lichtman SM, Gardes J, et al. Identifying vulnerable older adults with cancer: Integrating geriatric assessment into oncology practice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1604–1608. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.National Comprehensive Cancer Center Network. Senior adult oncology. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/senior.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]