Abstract

Purpose

A phase II study of bevacizumab (BVZ) plus irinotecan (CPT-11) was conducted in children with recurrent malignant glioma (MG) and intrinsic brainstem glioma (BSG).

Patients and Methods

Eligible patients received two doses of BVZ intravenously (10 mg/kg) 2 weeks apart and then BVZ plus CPT-11 every 2 weeks until progressive disease, unacceptable toxicity, or a maximum of 2 years of therapy. Correlative studies included diffusion weighted and T1 dynamic contrast–enhanced permeability imaging, BVZ pharmacokinetics, and estimation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR-2) phosphorylation in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) after single-agent BVZ.

Results

Thirty-one evaluable patients received a median of two courses of BVZ plus CPT-11 (range, 1 to 19). No sustained responses were observed in either stratum. Median time to progression for all 34 eligible patients enrolled was 127 days for MG and 71 days for BSG. Progression-free survival rates at 6 months were 41.8% and 9.7% for MG and BSG, respectively. Toxicities related to BVZ included grade 1 to 3 fatigue in seven patients, grade 1 to 2 hypertension in seven patients, grade 1 CNS hemorrhage in four patients, and grade 4 CNS ischemia in two patients. The mean diffusion ratio decreased after two doses of BVZ in patients with MG only. Vascular permeability parameters did not change significantly after therapy in either stratum. Inhibition of VEGFR-2 phosphorylation in PBMC was detected in eight of 11 patients after BVZ exposure.

Conclusion

BVZ plus CPT-11 was well-tolerated but had minimal efficacy in children with recurrent malignant glioma and brainstem glioma.

INTRODUCTION

Despite modern aggressive multimodality therapy, the outcome for children with malignant glioma and diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma remains quite poor, and new therapeutic interventions are required to improve disease control. Significant advances have been reported in understanding the role of angiogenesis in tumor growth, progression, and metastasis.1–4 Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a powerful endothelial mitogen and one of the most potent stimulators of angiogenesis.3 The protein exerts its effects via two receptor tyrosine kinases: VEGF receptor 1 (VEGFR-1; flt-1) and receptor 2 (VEGFR-2; KDR). VEGF overexpression has been demonstrated in pediatric brain tumors, including malignant gliomas.5–7 Due to its central role in tumor angiogenesis, VEGF inhibition has been proposed as a strategy for tumor control. In a phase II study in adults with recurrent glioblastoma (GBM), the use of the humanized monoclonal anti-VEGF antibody bevacizumab (BVZ; Avastin, GenenTech Corporation, San Francisco, CA), with irinotecan (CPT-11; Camptosar, Pfizer Corporation, New York, NY) resulted in an objective response rate of 63% and 6-month progression-free survival of 41%.8 Based on these encouraging results, the Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium initiated a phase II study in children with recurrent malignant glioma and diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma to assess the efficacy and toxicity of this regimen.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Objectives

The primary objective of the study was to estimate the rate of sustained (≥ 8 weeks) objective response to BVZ plus CPT-11 in children with recurrent malignant glioma (stratum A) or diffuse infiltrating pontine glioma (stratum B) over four courses of therapy.

Secondary objectives included estimating treatment-related toxicities and progression-free survival; pharmacokinetics of BVZ; changes in vascular permeability and VEGFR-2 phosphorylation in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) after two doses of single-agent BVZ (given 2 weeks apart); and changes in perfusion/diffusion on magnetic resonance imaging and [18F] fluordeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake by positron emission tomography (PET) during treatment.

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria.

Patients younger than 21 years with recurrent or progressive histologically confirmed malignant glioma or diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (by clinical and imaging criteria) and measurable disease were eligible for this study. Subjects were required to have a Karnofsky/Lansky score of at least 50, ≤ two recurrences before enrollment, ≥ 3 weeks from prior myelosuppressive chemotherapy or biologic therapy, ≥ 6 weeks from prior major surgical resection, and ≥ 3 months from local radiotherapy. Required evidence of adequate organ function included an absolute neutrophil count of ≥ 1,500/μL (unsupported), platelets ≥ 100,000/μL (unsupported), hemoglobin more than 8 gm/dL, serum creatinine ≤ upper limit of institutional normal (ULN), blood urea nitrogen lower than 25 mg/dL, bilirubin ≤ 1.5 × ULN, and AST and ALT ≤ 3 × ULN. Eligibility required no active systemic illness, stable neurologic function and corticosteroid dose (if any), and patient's agreement to use a medically acceptable form of birth control (in those of child-bearing or fathering potential).

Exclusion criteria.

Patients were excluded from the study if presenting with gliomatosis cerebri and no measurable enhancing tumor or imaging evidence of recent hemorrhage, prior exposure to BVZ or CPT-11, current anticoagulation or other investigational agents, or lack of availability for follow-up. Patients were also excluded if they had uncontrolled hypertension, bleeding diathesis, severe proteinuria, history of stroke, major surgical procedures within 6 weeks, gastrointestinal perforation within 6 months before registration, nonhealing wounds or bone fractures.

The institutional review boards of each Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium institution approved the protocol before initial patient enrollment; continuing approval was maintained throughout the study. Patients or their legal guardians gave written informed consent, and assent was obtained as appropriate at the time of enrollment.

Treatment Plan and Dose Modifications

Patients first received two doses of BVZ at 10 mg/kg intravenously 2 weeks apart. The first dose of CPT-11 was given within 3 days after the second dose of BVZ. The starting dose of CPT-11 was 125 mg/m2 intravenously for patients not on enzyme-inducing anticonvulsant drugs, increased in subsequent courses to 150 mg/m2, as tolerated; for patients on enzyme-inducing anticonvulsant drugs, a starting dose of 250 mg/m2 was increased in 25 mg/m2 increments every 2 weeks to a maximum of 350 mg/m2, as tolerated. The dose of CPT-11 was adjusted as previously reported based on hematologic and nonhematologic toxicities in subsequent courses.9 Patients who could not receive CPT-11 due to toxicity could continue treatment with BVZ in the absence of severe thrombocytopenia. BVZ was held for related ≥ grade 3 toxicities and restarted when toxicity had resolved to less than grade 2 without dose modification; CPT-11 was to be held in such instances. Patients who went off treatment and could not restart BVZ within 4 weeks were taken off study. Patients could receive therapy for a maximum period of 2 years in the absence of unacceptable toxicity or progressive disease.

Required Observations Before, During, and Off Study

Clinical examination (including neurologic function and blood pressure) was performed at baseline and every 2 weeks. Laboratory tests (CBC with differential, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, liver function, and urine for protein) were obtained at baseline and every 2 to 4 weeks during therapy. Magnetic resonance imaging brain scan (with or without spine) was obtained every 8 weeks during the first 6 months and every 12 weeks thereafter. Magnetic resonance perfusion and diffusion scans were done at baseline, within 24 to 48 hours of the second dose of BVZ (week 3, before the first dose of CPT-11), then every 8 weeks for the first 6 months and every 12 weeks through the first year of therapy, and at disease progression or cessation of therapy. FDG-PET scan of the brain was obtained before therapy and at week 8. Pharmacokinetic studies were obtained with patient consent and will be reported separately.

BVZ Pharmacodynamic Studies

Blood samples were also collected in consenting patients for VEGFR-2 phosphorylation by Western blot analysis on PBMC. Samples were obtained before the first dose of BVZ, just before the second dose, and 24 to 48 hours after the second dose of BVZ. Protein lysates were prepared from pellets of separated PBMC, and VEGFR-2 Tyr1175 expression was estimated relative to total VEGFR-2 levels using standard Western blotting techniques.

Evaluation of Response

Patients were evaluable for response assessment if they had received the first course of treatment unless there was clear evidence of progression during the first course. Responses were categorized as complete response, partial response, stable disease (SD), or progressive disease (PD) using MacDonald criteria.10 Patients with PD of up to 50% were allowed to remain on study as long as there were no clinical symptoms or signs or evidence of new site(s) of disease.

Study Design and Statistical Analysis

The primary objective of the study was to determine the true objective response (complete response plus partial response) to BVZ plus CPT-11 in children with recurrent malignant glioma and diffuse brainstem glioma as observed during the first four courses of treatment. Using Simon's minimax two-stage design with ≤ 10% objective response rate as unacceptable versus ≥ 30% objective response rate as acceptable and 10% type I and II error rates, a sample size of 25 patients was required for each stratum; 16 patients were enrolled during the first stage and at least two objective responses were required to enroll an additional nine patients in the second stage. The treatment regimen was deemed ineffective if fewer than five responses were observed in 25 patients. The study plan also specified models exploring correlations between MR perfusion/diffusion imaging, and FDG-PET uptake and responses in the same tumor site. Since no responses were observed, Cox proportional hazards models were used to explore relationships between progression-free survival (PFS) and functional changes in tumor measured by MR perfusion/diffusion imaging (diffusion ratio, maximum cerebral blood volume [CBV 3DMax], maximum permeability [Kps 3D Max]). Kaplan-Meier estimates of distributions of PFS were obtained based on all eligible patients who received at least one dose of BVZ in each stratum. PFS were measured from the date of initial treatment to the earliest date of disease progression, second malignancy or death for patients who failed, and to the date of last contact for patients who remained at risk for failure.

RESULTS

Between October 2006 and September 2008, 35 patients (18 stratum A, 17 stratum B) were enrolled. One patient was found to be ineligible in stratum B based on interval since prior myelosuppressive therapy. Three patients in stratum A were nonevaluable: inability to complete the first course of therapy (n = 2) or inadvertent dosing calculation error (received dose was > 10% below the specified dose; n = 1).

Patient Characteristics

Patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. The median age at enrollment was 15.7 years for stratum A (range, 5.6 to 20.1 years) and 8.7 years for stratum B (range, 2.9 to 14.6 years). Eight (45%) of 18 in stratum A had GBM. The median number of prior recurrences was one in both strata (range, 1 to 2 prior reccurances); all patients had received radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy before entry. The median performance status was 90 in both strata (range, 60 to 100). The median number of courses received by patients in stratum A was 3 (range, 1 to 18 courses) and was 2 in stratum B (range, 1 to 12 courses).

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Patients Treated on Stratum A and B

| Characteristic | Recurrent Malignant Glioma (stratum A) | Recurrent Diffuse Pontine Glioma (stratum B) |

|---|---|---|

| Patient | ||

| Total No. of patients | 18 | 17 |

| No. eligible | 18 | 16 |

| No. evaluable | 15 | 16 |

| Median age at enrollment, years | 15.7 | 8.7 |

| Histology | ||

| GBM | 8 | — |

| AA | 9 | |

| AO | 1 | |

| No. of patients on EIACD | 2 | 0 |

| No. of courses | 3 | 2 |

| Range | 1 to 18 | 1 to 12 |

| Objective responses (CR + PR) | 0 | 0 |

| No. of patients with stable disease for ≥ 12 weeks | 8 | 5 |

| No. of patients with progressive disease | 13 | 13 |

| Median PFS, months | 4.2 | 2.3 |

| 6-month PFS, % | 41.8 | 9.7 |

| Neuroimaging | ||

| CBV 3d Max | ||

| Median percentage change from baseline, % | +12.2 | +217 |

| Range | −54 to 196 | −81 to 1,028 |

| No. of patients | 7 | 8 |

| KPS 3d Max | ||

| Median percentage change from baseline, % | +29.8 | −10.6 |

| Range | −36 to 146 | −74 to 272 |

| No. of patients | 7 | 8 |

| Diffusion ratio | ||

| Median percentage change from baseline, % | −18.2 | +6.9 |

| Range | −49 to 45 | −39 to 53 |

| No. of patients | 16 | 13 |

Abbreviations: GBM, glioblastoma multiforme; AA, anaplastic astrocytoma; AO, anaplastic oligodendroglioma; EIACD, enzyme-inducing anticonvulsant drug; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; PFS, progression-free survival; CBV 3d Max, maximum cerebral blood volume; KPS 3d Max, maximum permeability.

Toxicity

The common grade 1 to 4 toxicities related to BVZ and CPT-11 are listed in Table 2. The most common toxicities related to BVZ in both strata were grade 1 to 3 fatigue and hypertension. Asymptomatic punctate intratumoral hemorrhage occurred in four patients on stratum B; each later came off treatment for tumor progression. Two patients (one in each stratum) suffered grade 4 CNS ischemia manifest by acute neurologic deficits and confirmatory neuroimaging and were taken off treatment. Grade 1 to 3 myelosuppression (n = 10), elevated transaminases (n = 9), and diarrhea (n = 6) were associated with CPT-11 (Table 2). Three patients in stratum A and 4 in stratum B came off therapy due to toxicity.

Table 2.

Toxicities Related to Bevacizumab or Irinotecan

| Toxicity | Grade | Bevacizumab |

Irinotecan |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stratum A (n = 18) | Stratum B (n = 15) | Stratum A (n = 18) | Stratum B (n = 15) | ||

| Fatigue | I-III | 6 | 1 | — | — |

| Epistaxis | I | 3 | 0 | — | — |

| Hypertension | I-III | 5 | 2 | — | — |

| Cerebral ischemia | IV | 1 | 1 | — | — |

| CNS hemorrhage | III | 0 | 4 | — | — |

| Proteinuria | I-II | 2 | 1 | — | — |

| Neutropenia | II-III | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | I-II | — | — | 5 | 2 |

| Diarrhea | I-III | — | — | 6 | 0 |

| Elevated transaminases | I-III | — | — | 7 | 2 |

| Pancreatitis | III | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Responses and PFS

No sustained objective responses were observed in 15 evaluable patients in stratum A and 16 in stratum B (Table 1). Eight patients in stratum A had sustained SD (duration ≥ 12 weeks) for a median of 176 days (range, 86 to 548 days; Tables 1 and 3). The median PFS was 4.2 months, and the 6-month PFS was 41.8% (95% CI, 22.8% to 76.6%; Table 1). Sustained SD was similarly observed in five patients in stratum B for a median of 126 days (range, 98 to 271 days). The median PFS was 2.3 months and 6-month PFS was 9.7% (95% CI, 1.6% to 60.4%). Disease progression was documented in 11 evaluable patients on stratum A (local, 6; local + metastatic, 2; metastatic, 2; clinical, 1) and 12 patients in stratum B (local, 12). In addition, two of the three inevaluable patients treated in stratum A also experienced PD (local, 2).

Table 3.

Clinical Characteristics of Eight Patients Who Experienced Stable Disease After Treatment With Bevacizumab Plus Irinotecan

| Patient No. | Age (years) | Location | Histology | No. of Courses | Site of Recurrence | Progression-Free Survival (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | Thalamus | Malignant glioma | 18 | Metastatic | 548 |

| 2 | 5 | Thalamus | GBM | 9 | Metastatic | 225 |

| 3 | 4 | Temporal lobe | GBM | 9 | None* | 273 |

| 4 | 7 | Temporal lobe | AA | 3 | None* | 87 |

| 5 | 3 | Thalamus | Malignant glioma | 5 | Local | 127 |

| 6 | 8 | Temporal lobe | AA | 3 | None* | 86 |

| 7 | 9 | Spinal cord with brain metastasis | AA | 5 | None* | 112 |

| 8 | 6 | Parietal lobe | AA | 10 | Local | 287 |

Abbreviations: GBM, glioblastoma multiforme; AA, anaplastic astrocytoma.

Patient taken off study for toxicity or withdrawal of consent without suffering progressive disease.

BVZ Pharmacodynamic Studies on PMBCs

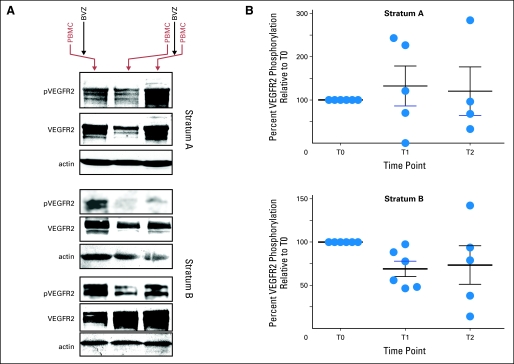

Baseline and one or more post-BVZ PBMC samples were available from six patients each in stratum A and B. Eleven of these twelve patients also provided samples approximately 14 days after the first dose of BVZ, whereas nine of the 12 had samples collected at baseline and immediately after the second dose of BVZ. PhosphoVEGFR-2 levels were reduced relative to baseline in eight of 11 patients approximately 14 days after the first dose of BVZ (Figs 1A and 2). While inhibition was observed in only two of five patients in stratum A, PBMC from all six patients in stratum B displayed inhibition at this time (Fig 1B; exact Wilcoxon signed rank test, P < .05). Immediately after the second dose of BVZ, PBMC from three of four patients in stratum A and four of five in stratum B displayed a relative decrease in phosphoVEGFR-2 levels (Fig 1B). No association was detected between phoshoVEGFR-2 levels and changes in vascular permeability (Kps 3D Max) or other imaging measures of vascular function.

Fig 1.

(A) Western blot analysis showing decrease in phosphorylated vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (pVEGFR2) 14 days after first dose of bevacizumab (BVZ) in one patient in stratum A (upper panel, lane 2) and two patients in stratum B (lower panels, lane 2). pVEGFR2 appears stable to increased after the second dose of BVZ in the same patient in stratum A (upper panel, lane 3) and decreased in two patients in stratum B (lower panels, lane 3). (B) Percentage change in pVEGFR-2 relative to baseline (T0) 14 days after first dose of BVZ (T1) and 48 hours after second dose of BVZ (T2). PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

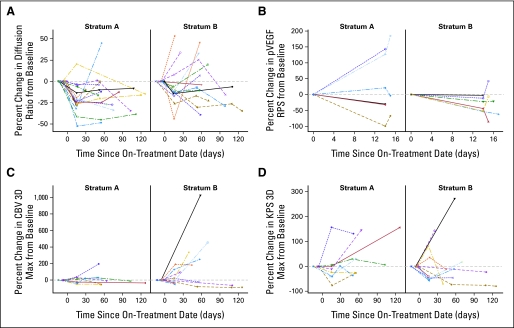

Fig 2.

Percent change in (A) diffusion, (B) phosphorylated vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (pVEGFR2), (C) maximum cerebral blood volume (CBV 3D Max), and (D) maximum permeability (Kps 3D Max) parameters as compared with baseline by stratum during the first four courses of treatment. RPS, receptor phosphorylation status.

Changes in Diffusion Ratio, CBV-3Dmax, and Kps3Dmax, and Volume Fluid Attenuated Inversion Recovery After Two Doses of BVZ and During Treatment With BVZ + CPT-11: Correlation With PFS

Perfusion and diffusion-weighted imaging were obtained at baseline and after two doses of BVZ in nine and 17 patients, respectively, in stratum A and 10 and five patients, respectively, in stratum B. The median diffusion ratio decreased between pretreatment and day 15 scans (P = .001) in stratum A but not in stratum B (P = .083). Eight patients in stratum A and seven in stratum B had permeability imaging at both baseline and after the second BVZ dose. However, changes in CBV 3D Max and Kps 3D Max were neither significant nor associated with PFS in either stratum.

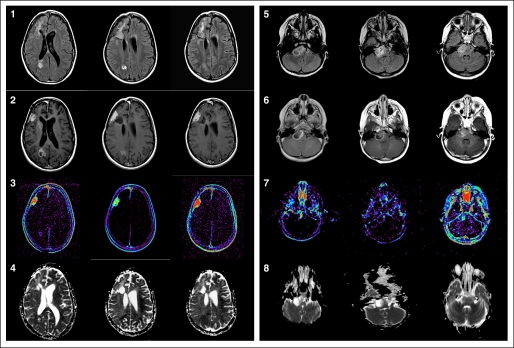

Change in diffusion ratio was separately assessed in each stratum and was measured over the first four courses of therapy. The slope estimate based on the diffusion ratios up to the first four courses of treatment was −0.0027 (P < .001) for patients on stratum A and −0.00072 (P = .6) for those on stratum B (Fig 2). Hence, it appears that diffusion ratio may decrease during the first four courses on therapy for the stratum A patients but did not correlate with PFS. A similar analysis for volume fluid attenuated inversion recovery, CBV, and Kps parameters did not show any significant change over time or correlation with PFS (Fig 2). Changes from baseline for CBV 3DMax, Kps3DMax, and diffusion ratio are listed in Table 1. Representative scans from one patient each from stratum A and B are shown in Figure A1 (Appendix, online only).

DISCUSSION

BVZ, a humanized monoclonal antibody, was developed as a specific inhibitor of all VEGF-A isoforms and has been US Food and Drug Administration approved in combination with chemotherapy for certain adult cancers including recurrent GBM.11,12 Inhibition of VEGF results in decreased vascular permeability, interstitial fluid pressure, more orderly blood flow due to pruning of unnecessary blood vessels, decrease in the number of tumor initiating cells due to disruption of their perivascular niche, and increase in chemotherapy drug delivery into the tumor.13,14

The clinical trial reported here is the first efficacy study in children with brain tumors. Our results indicate that this combination was not effective in producing sustained objective responses, with most patients coming off study for progressive disease. This is despite evidence from our pharmacodynamic studies that phosphoVEGFR-2 appears to be inhibited in vivo after treatment with BVZ. The observed rate of disease stabilization (27% at ≥ 12 weeks) does not appear different than that reported with standard chemotherapeutic agents (0% to 50%).15–19 This is in contrast to studies of single agent BVZ or BVZ + CPT-11 in adult recurrent malignant gliomas that have consistently shown evidence of sustained tumor shrinkage and improvement in OS.8,20,21 The reasons for treatment failure in our patients are unclear. It is possible that VEGF is not the sole mediator of angiogenesis in pediatric malignant gliomas and other angiogenic pathways (eg, fibroblast growth factor and/or placenta growth factor) sustain tumor growth in these patients.22 Alternatively, resistance mechanisms including activation of delta-like ligand-4 and increase in the proportion of mature tumor blood vessels robustly supported by pericytes and sustained by platelet-derived growth factor isoform BB stimulation might be operative and cannot be overcome by VEGF inhibition alone.22

The pattern of recurrence was predominantly local as expected for these tumors and we did not observe the diffuse, nonenhancing, infiltrative pattern of disease progression at relapse as has been noted in approximately 30% of adult patients with GBM who receive BVZ.23

Mild to moderate fatigue and hypertension were the most commonly reported toxicities in our study, but were manageable. As a typical antiangiogenic agent that disrupts tumor vasculature, BVZ is also associated with a risk of intratumoral hemorrhage (ITH),24,25 although recent evidence in adults with recurrent malignant gliomas indicates that the risk of severe ITH is lower than 1%.20,21 Four patients (12%) in our study suffered asymptomatic punctate intratumoral hemorrhage and none required intervention. This rate of asymptomatic hemorrhage is well within the baseline risk of ITH for brainstem gliomas reported in the literature in the absence of antiangiogenic therapy.26 The incidence of clotting and thromboembolic events is increased in patients treated with BVZ.27 Approximately 8% to 25% of adult patients with recurrent malignant glioma treated with BVZ experience thromboembolic events (arterial or venous).24 The incidence of this complication was low in our study, with only two (7%) of 32 of evaluable patients suffering from stroke after treatment.

Since BVZ-induced VEGF inhibition will result in decreased blood flow, CBV and Kps were used in this study to measure these parameters before and after treatment.28 As seen in adult patients after anti-VEGF therapy, individual patients in either stratum seemed to have decreased perfusion and permeability over time after treatment (Fig 3). Neither CBV nor Kps values changed significantly during treatment suggesting that angiogenic pathways other than VEGF might have contributed to maintenance of tumor blood flow.29,30 Diffusion imaging has been used in other studies as a measure of change in cellular content of the tumor after chemotherapy or anti-VEGF treatment and is a sensitive predictor of tumor response.29,31 The apparent diffusion coefficient values as measured by diffusion weighted imaging appeared to decrease over time in stratum A patients only, indicating a possible reduction in edema after BVZ.

We explored the pharmacodynamic effect of BVZ by measuring changes in VEGFR-2 phosphorylation in PBMC using western blot analysis, based on robust VEGFR-2 expression on a small proportion of PBMC.32 VEGFR-2 was readily detected in all PBMC by Western blotting. Further, we were able to detect decreases in phosphoVEGFR-2 after BVZ in the majority of patients, and in particular those with pontine glioma. Our data indicate that this approach is useful for detecting inhibition of phosphoVEGFR2 in vivo.

In summary, BVZ + CPT-11 did not demonstrate efficacy in children with recurrent malignant glioma or diffuse intrinsic brainstem gliomas. Since antiangiogenic therapy is likely to work better in the setting of minimal tumor burden and earlier in the disease course of such patients, it might be worthwhile using this combination at the time of initial diagnosis. This question is being addressed in an upcoming phase III Children's Oncology Group study for newly diagnosed malignant glioma that will use BVZ +CPT-11 as maintenance therapy after radiotherapy. Other strategies also need to be explored based on identification of unique signaling pathways that drive the relentless progression of these tumors.

Supplementary Material

Appendix

Fig A1.

Supratentorial glioblastoma multiforme in an 8-year-old girl (rows 1-4) and brainstem glioma in a 4-year-old girl (rows 5 to 8) at three time points: day 0, day 14, and 2 months later. Row 1: axial fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images demonstrate T2 hyperintensity within the right frontal lobe and right parietal lobe white matter at baseline that appears to decrease over time. Row 2: axial T1 images with gadolinium at baseline demonstrate enhancing foci of tumor in the right frontal lobe and right parietal lobe. There is decrease in enhancement in the right frontal lobe and parietal lobe lesions at day 14. Increased enhancement is noted in the right frontal lesion 2 months later. Row 3: axial T1 permeability maps demonstrate marked increased permeability in the right frontal and mild increased permeability in the right parietal lobe. At day 14, there is decrease in permeability in both lesions. With tumor progression at 2 months, there is increase in permeability within the right frontal lesion. Row 4: Axial apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps demonstrate mild restricted diffusion at day 14 within the tumor which then increased 2 months later. Row 5: axial FLAIR images demonstrate T2 hyperintensity in the pons with predominance on the right. Row 6: axial T1 images with gadolinium demonstrate ring enhancement in the right pons at baseline with central necrosis. There is decreased enhancement and necrosis at day 14 and increased solid enhancement 2 months later. Row 7: axial T1 permeability image demonstrates increased permeability in the medial component of the brainstem glioma at baseline that diminishes by day 14 and then increases at 2 months. Row 8: axial ADC maps demonstrate increased diffusion in the central portion of the tumor with restricted diffusion around the margins at baseline and day 14 scans. There is more restricted diffusion within the tumor at 2 months.

Footnotes

Supported by Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium Grant No. U01CA81457, National Center for Research Resources Grant No. M01RR00188, and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities.

Presented in part at the Society for Neuro-Oncology, Las Vegas, NV, November 20-23, 2008, and New Orleans, LA, October 22-24, 2009.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

Clinical trial information can be found for the following: NCT00381797.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: Henry S. Friedman, Genentech (C) Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: Henry S. Friedman, Genentech Research Funding: Henry S. Friedman, Genentech; James M. Boyett, Hoffman-LaRoche, Merck Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Sridharan Gururangan, Susan N. Chi, Arzu Onar-Thomas, Richard J. Gilbertson, Henry S. Friedman, Roger J. Packer, James M. Boyett, Larry E. Kun

Administrative support: James M. Boyett, Larry E. Kun

Provision of study materials or patients: Sridharan Gururangan, Roger J. Packer, Brian N. Rood, Larry E. Kun

Collection and assembly of data: Sridharan Gururangan, Tina Young Poussaint, Arzu Onar-Thomas, Roger J. Packer, Brian N. Rood, James M. Boyett

Data analysis and interpretation: Sridharan Gururangan, Tina Young Poussaint, Arzu Onar-Thomas, Richard J. Gilbertson, Sridhar Vajapeyam, Henry S. Friedman, Roger J. Packer, Larry E. Kun

Manuscript writing: Sridharan Gururangan, Tina Young Poussaint, Arzu Onar-Thomas, Richard J. Gilbertson, Roger J. Packer, Brian N. Rood, Larry E. Kun

Final approval of manuscript: Sridharan Gururangan, Susan N. Chi, Tina Young Poussaint, Arzu Onar-Thomas, Richard J. Gilbertson, Sridhar Vajapeyam, Henry S. Friedman, Roger J. Packer, Brian N. Rood, James M. Boyett, Larry E. Kun

REFERENCES

- 1.Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis: Therapeutic implications. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:1182–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197111182852108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Browder T, Butterfield CE, Kraling BM, et al. Antiangiogenic scheduling of chemotherapy improves efficacy against experimental drug-resistant cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1878–1886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karkkainen MJ, Petrova TV. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptors in the regulation of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Oncogene. 2000;19:5598–5605. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Folkman J. What is the evidence that tumors are angiogenesis dependent? J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990;82:4–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang H, Held-Feindt J, Buhl R, et al. Expression of VEGF and its receptors in different brain tumors. Neurol Res. 2005;27:371–377. doi: 10.1179/016164105X39833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huber H, Eggert A, Janss AJ, et al. Angiogenic profile of childhood primitive neuroectodermal brain tumours/medulloblastomas. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:2064–2072. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00225-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korshunov A, Golanov A, Sycheva R. Immunohistochemical markers for prognosis of oligodendroglial neoplasms. J Neurooncol. 2002;58:237–253. doi: 10.1023/a:1016270101321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vredenburgh JJ, Desjardins A, Herndon JE, Jr, et al. Phase II trial of bevacizumab and irinotecan in recurrent malignant glioma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1253–1259. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman HS, Petros WP, Friedman AH, et al. Irinotecan therapy in adults with recurrent or progressive malignant glioma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1516–1525. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.5.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macdonald DR, Cascino TL, Schold SC, Jr, et al. Response criteria for phase II studies of supratentorial malignant glioma. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:1277–1280. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.7.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pazdur R. FDA Approval of Bevacizumab, Drug Information, National Cancer Institute. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/druginfo/fda-bevacizumab.

- 12.Ignoffo RJ. Overview of bevacizumab: A new cancer therapeutic strategy targeting vascular endothelial growth factor. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61:S21–S26. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/61.suppl_5.S21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calabrese C, Poppleton H, Kocak M, et al. A perivascular niche for brain tumor stem cells. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jain RK. Lessons from multidisciplinary translational trials on anti-angiogenic therapy of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:309–316. doi: 10.1038/nrc2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lashford LS, Thiesse P, Jouvet A, et al. Temozolomide in malignant gliomas of childhood: A United Kingdom Children's Cancer Study Group and French Society for Pediatric Oncology Intergroup Study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4684–4691. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicholson HS, Kretschmar CS, Krailo M, et al. Phase 2 study of temozolomide in children and adolescents with recurrent central nervous system tumors: A report from the Children's Oncology Group. Cancer. 2007;110:1542–1550. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finlay JL, Dhall G, Boyett JM, et al. Myeloablative chemotherapy with autologous bone marrow rescue in children and adolescents with recurrent malignant astrocytoma: Outcome compared with conventional chemotherapy: A report from the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:806–811. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heideman RL, Packer RJ, Reaman GH, et al. A phase II evaluation of thiotepa in pediatric central nervous system malignancies. Cancer. 1993;72:271–275. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930701)72:1<271::aid-cncr2820720147>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kadota RP, Stewart CF, Horn M, et al. Topotecan for the treatment of recurrent or progressive central nervous system tumors: A pediatric oncology group phase II study. J Neurooncol. 1999;43:43–47. doi: 10.1023/a:1006294102611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kreisl TN, Kim L, Moore K, et al. Phase II trial of single-agent bevacizumab followed by bevacizumab plus irinotecan at tumor progression in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:740–745. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedman HS, Prados MD, Wen PY, et al. Bevacizumab alone and in combination with irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4733–4740. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellis LM, Hicklin DJ. Pathways mediating resistance to vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6371–6375. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zuniga RM, Torcuator R, Jain R, et al. Efficacy, safety and patterns of response and recurrence in patients with recurrent high-grade gliomas treated with bevacizumab plus irinotecan. J Neurooncol. 2009;91:329–336. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9718-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon MS, Cunningham D. Managing patients treated with bevacizumab combination therapy. Oncology. 2005;69(suppl 3):25–33. doi: 10.1159/000088481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carden CP, Larkin JM, Rosenthal MA. What is the risk of intracranial bleeding during anti-VEGF therapy? Neuro Oncol. 2008;10:624–630. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Broniscer A, Laningham FH, Kocak M, et al. Intratumoral hemorrhage among children with newly diagnosed, diffuse brainstem glioma. Cancer. 2006;106:1364–1371. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kilickap S, Abali H, Celik I. Bevacizumab, bleeding, thrombosis, and warfarin. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3542. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.99.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller JC, Pien HH, Sahani D, et al. Imaging angiogenesis: Applications and potential for drug development. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:172–187. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Batchelor TT, Sorensen AG, di Tomaso E, et al. AZD2171, a pan-VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, normalizes tumor vasculature and alleviates edema in glioblastoma patients. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:83–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Narayana A, Golfinos JG, Fischer I, et al. Feasibility of using bevacizumab with radiation therapy and temozolomide in newly diagnosed high-grade glioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72:383–389. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kauppinen RA. Monitoring cytotoxic tumour treatment response by diffusion magnetic resonance imaging and proton spectroscopy. NMR Biomed. 2002;15:6–17. doi: 10.1002/nbm.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elsheikh E, Uzunel M, He Z, et al. Only a specific subset of human peripheral-blood monocytes has endothelial-like functional capacity. Blood. 2005;106:2347–2355. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.