Abstract

The SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex plays pivotal roles in mammalian transcriptional regulation. In this study, we identify the human requiem protein (REQ/DPF2) as an adaptor molecule that links the NF-κB and SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling factor. Through in vitro binding experiments, REQ was found to bind to several SWI/SNF complex subunits and also to the p52 NF-κB subunit through its nuclear localization signal containing the N-terminal region. REQ, together with Brm, a catalytic subunit of the SWI/SNF complex, enhances the NF-κB-dependent transcriptional activation that principally involves the RelB/p52 dimer. Both REQ and Brm were further found to be required for the induction of the endogenous BLC (CXCL13) gene in response to lymphotoxin stimulation, an inducer of the noncanonical NF-κB pathway. Upon lymphotoxin treatment, REQ and Brm form a larger complex with RelB/p52 and are recruited to the BLC promoter in a ligand-dependent manner. Moreover, a REQ knockdown efficiently suppresses anchorage-independent growth in several cell lines in which the noncanonical NF-κB pathway was constitutively activated. From these results, we conclude that REQ functions as an efficient adaptor protein between the SWI/SNF complex and RelB/p52 and plays important roles in noncanonical NF-κB transcriptional activation and its associated oncogenic activity.

Keywords: Chromatin Remodeling, Epigenetics, NF-κB Transcription Factor, Oncogene, Protein-Protein Interactions, Requiem Protein, Noncanonical Pathway

Introduction

The SWI/SNF (switch/sucrose-nonfermentable) chromatin remodeling complex has important functional roles in the epigenetic regulation of many organisms and regulates a wide variety of genes (1, 2). In mammals, this complex is an assembly of about nine polypeptides and contains a single molecule of either Brm or BRG1 but not both (3). These two proteins are the catalytic subunits that together with noncatalytic subunits, such as BAF170, BAF155, Ini1, BAF60a, and β-actin, drive the remodeling of nucleosomes via their ATP-dependent helicase activity (4). Evidence has now accumulated that the Brm-type and BRG1-type SWI/SNF complexes regulate a set of target promoters that do not fully overlap. Indeed, Brm and BRG1 show clear differences in their biological activities. For example, Brm-type, but not BRG1-type, SWI/SNF complexes are essential for the maintenance of gene expression driven by the long terminal repeats of murine leukemia virus (5, 6) and human immunodeficiency virus (7). Moreover, in gastrointestinal cells, Brm but not BRG1 can transactivate Cdx2-dependent villin expression, even though both proteins can interact with Cdx2 (8). Overall, the SWI/SNF complexes interact with various proteins, including transcriptional regulators, through the many specific and varied associations with their subunits. We previously demonstrated that among all of the dimers formed between Fos and Jun family proteins, which compose the representative transcription factor AP-1, the c-Fos/c-Jun heterodimer most efficiently recruits SWI/SNF complexes to AP-1-binding sites through its specific binding activity to the BAF60a SWI/SNF subunit (9).

Like AP-1, the NF-κB3 is an important transcription factor, which plays crucial roles in key physiological processes, including development, cell proliferation, apoptosis, and innate and adaptive immune functions (10, 11). The NF-κB family is composed of five different proteins as follows: RelA (p65), RelB, c-Rel, p50 (which is processed from its precursor p105), and p52 (which is processed from its precursor p100). These proteins form active transcription factors in either homodimeric or heterodimeric forms. Among the various NF-κB-activating signals, two different NF-κB pathways have been well studied to date. One is the canonical NF-κB pathway, which is activated by TNF-α and interleukin-1 stimulation, that leads to the proteosomal degradation of cytosolic IκBα. This facilitates the nuclear translocation of the RelA/p50 dimer, which induces the expression of IL8 and IκBα (12). The other pathway is the noncanonical NF-κB pathway, which is activated by lymphotoxin and CD40 ligand. Upon this activation, activated NF-κB-inducing kinase and IκB kinase α induce the processing of p100 to p52, which triggers the expression of the BLC (B lymphocyte chemokine) and ELC (EBV-induced molecule 1 ligand chemokine) genes by the RelB/p52 dimer (13). Importantly, some NF-κB target genes stimulated by these cytokines or growth factors have often been suggested to require SWI/SNF complexes for their optimum induction (14, 15). However, the underlying molecular mechanisms and factors involved in this process remain largely unknown.

We previously identified p54nrb as a SWI/SNF complex binding protein by direct nanoflow LC-MS analysis of FLAG-tagged BRG1 immunoprecipitates (16). SWI/SNF complex in concert with p54nrb initiates the efficient transcription of the TERT gene in human tumor cell lines and is also involved in the subsequent splicing of TERT transcripts by accelerating exon inclusion, which partly contributes to the maintenance of active telomerase. In our current analyses, we have identified that the human requiem protein (REQ/DPF2) associates with both FLAG-Brm SWI/SNF and FLAG-BRG1 SWI/SNF complexes, and we thus selected it for further evaluation. REQ was originally identified as an apoptosis-inducing protein in mouse myeloid cells and belongs to the d4 family of proteins. The members of this family typically show distinct domain organization, including an N-terminal nuclear localization signal, a Krüppel-type zinc finger in the central region of the protein, and two adjacent PHD fingers at the C terminus (17, 18). Recently, the d4 family proteins DPF1, DPF3, and REQ (DPF2), as well as a distantly related protein, PHF10, which contains tandem C-terminal PHD fingers, have been shown to be subunits of SWI/SNF complexes (19). Indeed, subunit switching from PHF10 to DPF1/DPF3 plays pivotal roles in neuronal development. It has also been reported that DPF3 and its splicing variant CERD4 regulate muscle development (20). However, the biological and biochemical functions of REQ remain largely unknown.

In this study, we present evidence that REQ is a specific adaptor protein that links RelB/p52 with Brm-type SWI/SNF complexes and thereby plays pivotal roles at the most downstream stages of the noncanonical NF-κB pathway. We further show that REQ is required for oncogenesis in several human tumor cell lines in which the noncanonical NF-κB pathway is aberrantly regulated.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

The human embryonic kidney cell lines, HEK-293T, HEK-293FT (Invitrogen), and PLAT, and the human tumor cell lines, HeLaS3 (human cervical adenocarcinoma), NCI-H1299 (non-small cell lung carcinoma), Panc-1 (pancreatic cancer), and HT-29 (human colon cancer), were grown at 37 °C in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum.

Purification and Analysis of FLAG-Brm- and FLAG-BRG1-containing Complexes

Proteome analysis was performed essentially as described previously (16). Briefly, ∼2 × 108 293T cells were transfected with either FLAG-Brm or FLAG-BRG1 plasmid, harvested, and first extracted for 10 min at 4 °C in buffer AS (10 mm HEPES (pH 7.9), 1.5 mm MgCl2, 10 mm KCl, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, and protease inhibitors (1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 100 μg/ml antipain, 100 μg/ml leupeptin, 100 units/ml aprotinin)). The nuclei were then pelleted rapidly and extracted in buffer CS (20 mm HEPES (pH 7.9), 1.5 mm MgCl2, 0.5 m NaCl, 25% glycerol, protease inhibitors) for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were then diluted with an equal volume of buffer containing 25 mm HEPES (pH 7.9), 2.5 mm EDTA (pH 8.0), 0.1% Nonidet P-40, and protease inhibitors and ultracentrifuged at 100,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. This nuclear extracts prepared by a modified Dignam's method (21) were incubated with anti-FLAG affinity gel (Sigma) at 4 °C overnight, and the gel was then washed five times with wash buffer (25 mm HEPES (pH 7.9), 250 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA (pH 8.0), 0.1% Nonidet P-40). The immunoprecipitates were eluted twice with a buffer containing 250 μg/ml FLAG peptide in wash buffer. The eluates were then either silver-stained, Western-blotted, or subjected to direct nanoflow LC-MS analysis as described previously (22).

Nuclear Extraction and Immunoprecipitation

Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were prepared from HT-29 cells essentially as described previously (23) and incubated with either normal rabbit IgG or with anti-Brm, anti-BRG1, anti-REQ, and anti-RelB antibodies in a reaction containing buffer D (20 mm HEPES (pH 7.9), 100 mm KCl, 20% glycerol, 0.2 mm EDTA, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) at 4 °C overnight. Protein G Plus-agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) were then added, and the samples were further incubated at 4 °C for 1 h. The beads were then collected and washed three times with buffer D, and bound protein complexes were analyzed by Western blotting using the antibodies listed under “Protein Analysis.”

Protein Analysis

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting analyses were performed using antibodies against FLAG (Sigma), Brm (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), BRG1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), BAF155 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), BAF60a (BD Transduction Laboratories, San Jose, CA), Ini1 (BD Transduction Laboratories), RelB (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), p100/p52 (Millipore, Billerica, MA), and actin (BD Transduction Laboratories) as described previously (16). Anti-REQ antibody was prepared as follows: GST-CT3 prepared from Escherichia coli was digested with thrombin (GE Healthcare) to separate the N-terminal GST region. The CT3 protein band was then isolated and used to raise antibody in rabbits.

Luciferase Reporter Assays

HEK-293FT cells were transfected with pGL-HIVκB-MLCB using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), and stable transfectants were obtained by selection in 5 μg/ml blasticidin for 1 week. These stable cells were then seeded into 24-well plates (1 × 105 cells/well) and 24 h later transfected with pRK5-RelA/pRK5-p50, pRK5-RelB/pRK5-p52, or pRK5-c-Rel/pRK5-p50 (10 ng each) and expression vectors for pCAGF-Brm, pCAGF-BRG1, and pCAGF-REQ as well as empty vector (400 ng) together with pRK5 (total DNA amount was adjusted to 500 ng) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). 48 h after transfection, luciferase activity was determined using a luciferase assay system and Glo-max (Promega, Madison, WI).

In Vitro Transcription and in Vitro Translation

In vitro transcription was performed using Megascript (Ambion, Austin, TX) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Brm and BRG1 transcripts were translated in vitro for 1 h at 30 °C using rabbit reticulocyte lysates (Promega) in the presence of [35S]methionine as described previously. Transcripts of BAF60a, Ini1, RelA, RelB, p50, and p52 were translated in vitro for 1 h at 25 °C in wheat germ lysates (Promega) also in the presence of [35S]methionine.

GST Pulldown Assay

GST, GST-REQ, and its truncation mutants (1 μg each) were prepared from E. coli (Rosetta2) harboring the corresponding expression plasmids as described previously (16). These bacterially expressed proteins were mixed with proteins synthesized in vitro and incubated with glutathione beads with agitation for 2 h at 4 °C. The beads were then washed six times with TNE buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, and protease inhibitors) and boiled in SDS sample buffer. Eluted protein samples were separated by SDS-PAGE, treated with Enhance, and detected using an Image analyzer FLA-5100 (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan).

RT-PCR

293FT cells were seeded into 24-well plates (1 × 105 cells/well) and 24 h later were transfected with pRK5-RelA/pRK5-p50, pRK5-RelB/pRK5-p52, or pRK5-c-Rel/pRK5-p50 constructs (10 ng each) and short hairpin RNA (shRNA) vectors against GFP (control), Brm, BRG-1, and REQ (400 ng) together with empty vector, pRK5 (the total DNA amount was adjusted to 500 ng) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). At 3 days after transfection, total RNAs were extracted from cell culture using Isogen (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan). For HT-29 cells, total RNA extracts were isolated in the same way from cell culture cells stably transduced with shRNA expression vectors against Brm, BRG-1, REQ, or GFP (control) with or without lymphotoxin treatment. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the ELC, BLC, and GAPDH genes was performed using Superscript one-step RT-PCR with a platinum Taq kit (Invitrogen). The primer sets used are listed in supplemental Table S1.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays were performed using a commercial kit from Millipore in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The HT-29 cell line was used for these analyses (1 × 107 cells). The antibodies (10 μg each) used are listed under “Protein Analysis.” After the immunoprecipitates were digested with proteinase K, DNA was phenol-extracted and precipitated with isopropyl alcohol. Using this prepared DNA as the template, semi-quantitative PCR analysis of the BLC, CD44, and GAPDH promoters was performed using the primer pairs listed in supplemental Table S1.

Retrovirus Vectors

VSV-G pseudotyped replication defective retrovirus vectors were prepared and transduced into cells as described previously (24). Viral vectors carrying shBrm, shBRG1, and shGFP expression units have also been described previously (25). FLAG-REQ, shREQ#1, shREQ#2, or shRelB expressing viruses were produced by transfecting cells with pMXs-FLAGREQ-IN, pSSSP-shREQ#1, pSSSP-shREQ#2, or pSSSP-shRelB, respectively. shREQ#1 and shREQ#2 were designed to target 1800–1820 nucleotides (in the 3′-untranslated region) and 918–938 nucleotides (in the coding sequence) of the human REQ mRNA (GenBankTM accession number NM_006268), respectively, and have the completely complementary sequences to them.

Cellular Growth Assays and Anchorage-independent Cell Growth Assays

Cellular growth assays were performed using monolayer cultures and Cell-Titer Glo (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Anchorage-independent cell growth assays were performed as described previously (26).

Other Procedures

Details of the materials and methods used in this study can be found in the supplemental material.

RESULTS

REQ Binds to Subunits of the SWI/SNF Complex in Vitro and in Vivo

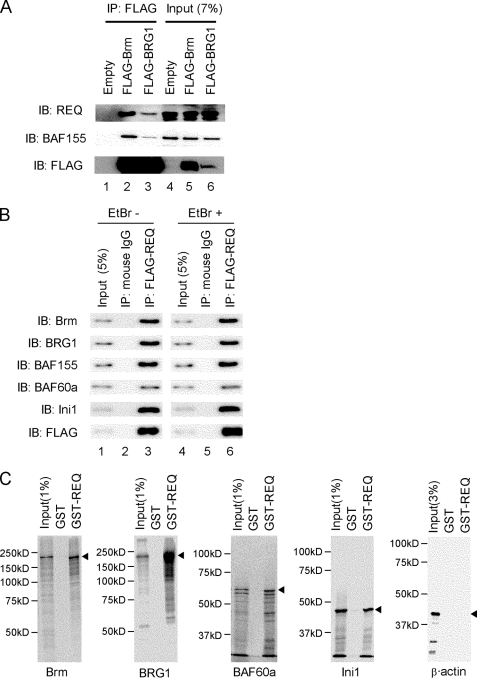

Nuclear extracts from 293T cells transiently transfected with either FLAG-Brm- or FLAG-BRG1-expressing plasmids were isolated, and SWI/SNF complexes were purified using anti-FLAG affinity resin (supplemental Fig. S1A) as reported previously (16). The whole eluates were then analyzed by direct nanoflow LC-MS, and the resulting mass spectra identified p54nrb and several other proteins, in addition to almost all of the known components of SWI/ SNF complexes (supplemental Fig. S1B). Among the other proteins, we detected three peptides corresponding to REQ (supplemental Fig. S1C) and confirmed the presence of this protein from the isolated complexes by immunoblotting with anti-REQ antibody (Fig. 1A). REQ was found to copurify with either FLAG-Brm or FLAG-BRG1 (Fig. 1A, lanes 2 and 3) in a similar manner to BAF155, an essential component of the SWI/SNF complex. Moreover, when nuclear fractions from HT-29 cells stably expressing FLAG-REQ were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody, several SWI/SNF components were detected in the immunoprecipitates by immunoblotting with antibodies against Brm, BRG1, BAF155, BAF60a, and Ini1 (Fig. 1B, lane 3). To exclude the possibility that these observed protein-protein interactions were due to their colocalization on DNA, immunoprecipitations were carried out in the presence of ethidium bromide (EtBr) (27), which was found not to affect the REQ-containing complex (Fig. 1B, lane 6).

FIGURE 1.

Interactions between REQ and the SWI/SNF complexes in vivo and in vitro. A, Brm and BRG1 interact with REQ in vivo. Nuclear extracts from 293FT cells transiently expressing FLAG-Brm or FLAG-BRG1 were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-FLAG antibody and immunoblotted (IB) using anti-REQ, anti-BAF155, and anti-FLAG antibodies, respectively. B, REQ interacts with Brm and BRG-1 in vivo. Nuclear extracts of HT-29 cells stably transduced with the pMXs-FLAG-REQ retroviral vector were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody and analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-Brm, anti-BRG1, anti-BAF60a, anti-BAF155, anti-Ini1, and anti-FLAG antibodies, respectively. The immunoprecipitation assay was performed in the absence (EtBr−) or presence (EtBr+) of 50 μg/ml ethidium bromide. C, REQ interacts with SWI/SNF components in vitro. GST and GST-REQ proteins were mixed with the in vitro synthesized 35S-proteins indicated. Binding proteins were eluted by boiling in SDS sample buffer, resolved by PAGE, and detected by autoradiography. Molecular mass markers (left) and the predicted position of each in vitro synthesized protein (arrowheads) are shown.

To examine the interactions between the SWI/SNF complexes and REQ in greater detail in vitro, we generated a GST-REQ fusion protein for use in pulldown assays. The SWI/SNF complex subunits Brm, BRG1, BAF60a, Ini1, and β-actin were synthesized in vitro using wheat germ or rabbit reticulocyte extracts and charged on a GST-REQ column. We clearly observed in vitro binding of Brm, BRG1, BAF60a, and Ini1 but not β-actin to GST-REQ (Fig. 1C).

Transactivation by RelB/p52 Requires Both REQ and SWI/ SNF

Because SWI/SNF complexes often exert transactivation activity via their direct binding to specific transcription factors, the possibility that REQ may mediate this function was considered. However, REQ does not contain sufficient DNA-binding motifs to enable it to perform such a role. We have previously shown in this regard that SWI/SNF complexes forms larger structures with a transcriptional repressor known as neuron-restrictive silencer factor (NRSF/REST), through the direct binding of its cofactors, mSin3A and CoREST, which function as adaptor proteins linking SWI/SNF and NRSF (25). Hence, we speculated that REQ may also function as an adaptor protein. We subsequently generated several luciferase gene reporter plasmids containing enhancer elements that included either tumor promoter responsive element (AP-1-binding site) from the collagenase gene promoter, a minimal promoter inserted with a single tumor promoter responsive element, or a promoter with three tandem NF-κB-binding sites. These constructs were then transiently cotransfected into HEK-293FT cells with Brm, BRG1 or REQ expression vectors and with shRNA vectors that target these three genes. However, no significant effects could be observed as a result of any of these transfections (data not shown).

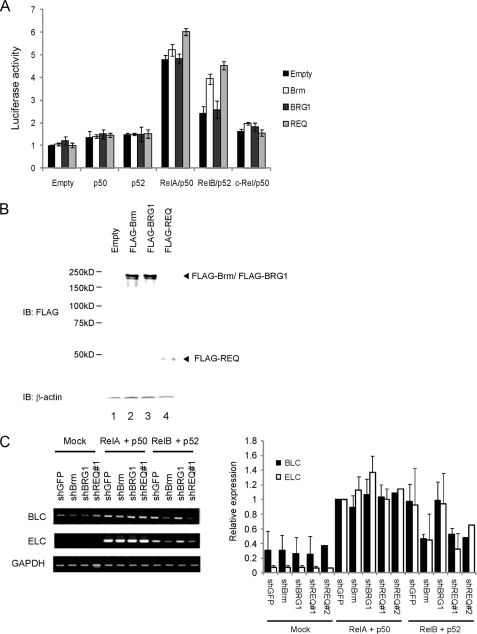

Given that stringent chromatin structures are possibly required to assay any transcriptional activation generated by the interaction between SWI/SNF complexes and REQ (28), we designed several cellular assay systems in which luciferase reporter genes were stably integrated into cellular chromatin. Among the several reporters tested in 293FT cells, we found that a stably integrated luciferase construct driven by two tandem repeats of an NF-κB-binding site derived from human immunodeficiency virus, type 1, long terminal repeat was specifically activated by exogenously introduced REQ under certain conditions. As shown in Fig. 2A, the exogenous introduction of RelA/p50 or RelB/p52 enhances the basal expression levels of luciferase by 4.8- and 2.4-fold, respectively, whereas c-Rel/p50 showed only a marginal induction. Neither p50 nor p52 alone activated NF-κB, probably because of the lack of a transactivating domain. Importantly, the transactivation activity of exogenously introduced RelB/p52 was significantly activated by the additional introduction of either REQ or Brm but not BRG1. The expression levels of these exogenous genes were then analyzed by Western blotting using anti-FLAG antibody and were found to be similar (Fig. 2B, lanes 2–4). Transactivation by RelA/p50 was also found to be enhanced by the additional expression of REQ, although to a lesser extent. These observations suggest that REQ and Brm play important roles in the transactivation functions of RelB/p52.

FIGURE 2.

REQ and Brm specifically promote RelB/p52-dependent transcriptional activity. A, REQ and Brm activate RelB/p52-dependent luciferase activity. 293FT cells harboring the NF-κB reporter gene were transfected with NF-κB expression vectors (p50, p52, RelA/p50, RelB/p52, and c-Rel/p50) or the corresponding empty vector (pRK5) and cotransfected with expression vectors for Brm, BRG1, REQ, or the empty vector (pCAGF). 48 h after transfection, luciferase activity was determined. Values were defined as a ratio in comparison with the results from pRK5- and pCAGF-transfected cells. The columns represent the average values from triplicate experiments, and the bars indicate the standard deviation. B, protein levels generated from exogenous FLAG-protein expression vectors in the 293 FT cells used in A. The total protein was analyzed by Western blotting using anti-FLAG antibody. IB, immunoblot. C, effects of the knockdown of Brm, BRG-1, or REQ upon the expression of the endogenous ELC, BLC, and GAPDH genes in 293FT cells transiently transfected with RelA/p50 or RelB/p52. 293FT cells were transfected with expression vectors for RelA/p50, RelB/p52, or empty vector and with vectors expressing shBrm, shBRG1, shREQ#1, or shGFP (control). 3 days after transfection, the endogenous gene levels were analyzed by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. Similar transfection experiments were repeated two more times, and results of their expression levels are shown in supplemental Fig. S3. Densitometric analysis of these three gels was summarized in the right panel after the expression levels were normalized relative to those of “RelA/p50 and shGFP-expressing cells,” which were given a value of 1. The columns represent the average of triplicate, and the bars indicate the standard deviation (except for shREQ#2).

We next tested whether the activation of the target genes of endogenous RelB/p52 requires REQ, Brm, or BRG1. We selected the BLC and ELC genes for this analysis as they are highly responsive to the RelB/p52 pathway (29). HEK-293FT cells that had been transiently transfected with expression vectors for RelB/p52 or RelA/p50 were cotransfected with shRNA expression vectors against REQ, Brm, or BRG1. Total RNA was then isolated, and expression levels of the BLC and ELC genes were analyzed by semi-quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 2C, left panel). Protein analysis of the parallel cultures confirmed that the knockdowns by shBrm, shBRG1, and shREQ#1 were effective (supplemental Fig. S2A). This transient experiment was repeated three times (Fig. 2C and supplemental Fig. S3), and the average of the expression levels was summarized after densitometry analysis (Fig. 2C, right panel). Both BLC and ELC genes were found to be induced not only by RelB/p52 but also by RelA/p50. Importantly, a clear suppression of the induction of both BLC and ELC by RelB/p52 was observed upon the expression of shBrm or two species of shREQ, shREQ#1 (targeting a 3′-untranslated region sequence) and shREQ#2 (targeting a coding sequence). Neither shBrm nor shREQ#1 and shREQ#2 affected the stimulation of BLC or ELC by RelA/p50. These observations are in good overall agreement with the results of our luciferase reporter assay and indicate that both REQ and Brm are required for efficient transactivation by RelB/p52. On the other hand, the BRG1 knockdown did not strongly affect the induction of either of these genes under any condition tested.

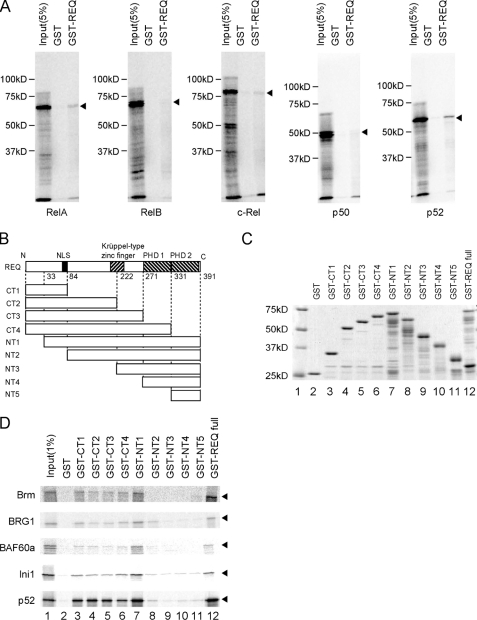

Using in vitro synthesized human RelA, RelB, c-Rel, p50, and p52 proteins, we performed GST pulldown assays using GST-REQ columns (Fig. 3A). A moderate association (more than 0.4% of the input on average in three independent experiments) was detected for p52, whereas only marginal binding of RelA, RelB, or c-Rel (about 0.1% of the input) was observed for GST-REQ. No significant interaction was detected for p50. REQ contains several functional domains shared by the d4 family of proteins, including a nuclear localization signal, a single Krüppel-type zinc finger domain, and two plant homeobox domains, PHD1 and PHD2 (Fig. 3B). To examine the regions of REQ responsible for the binding to SWI/SNF subunits and p52, we constructed a series of truncation mutants of GST-REQ, in which we took the functional domains of REQ into account (Fig. 3, B and C, lanes 3–12). NT1 (Fig. 3D, lane 7) retained significant binding capacities for Brm, BRG1, BAF60a, Ini1, and p52. CT1–4 (Fig. 3D, lanes 3–6) also retained these binding activities, although to a lesser extent. These results indicate that an N-terminal domain of REQ encompassing amino acids 33–84, which is shared by the CT1 and NT1 deletion mutants, is crucial for binding of SWI/SNF subunits and p52.

FIGURE 3.

N-terminal region of REQ interacts with either SWI/SNF components or NF-κB p52 in vitro. A, REQ interacts with NF-κB p52 in vitro. RelA, RelB, c-Rel, p50, and p52 were each synthesized in vitro in the presence of [35S]methionine, and GST pulldown assays were performed as described in Fig. 1C. B, structure of GST-REQ and GST fused to C-terminally truncated (CT1653744) and N-terminally truncated (NT1653745) REQ products. NLS, nuclear localization signal. C, Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining of the GST fusion proteins analyzed in D. D, an N-terminal region of REQ interacts with Brm, BRG-1, BAF60a, Ini1, and p52 in vitro. GST fusion proteins (B and C) were mixed with Brm, BRG-1, BAF60a, Ini1, or p52 synthesized in the presence of [35S]methionine. Bound proteins were analyzed as described in Figs. 1C and 3A. Arrowheads indicate the predicted position of each protein synthesized in vitro.

BLC Induction by Lymphotoxin Requires Both REQ and Brm

We examined whether REQ and the Brm-type SWI/SNF complex play important roles in inducing RelB/p52 transactivation when a natural NF-κB pathway is stimulated in cells. We employed lymphotoxin, which is a well known canonical activator of RelA/p50 and noncanonical stimulator of RelB/p52, and the HT-29 human colon adenocarcinoma cell line for these analyses. HT-29 cells have been reported to efficiently express lymphotoxin receptors as well as Brm and BRG1 proteins (supplemental Fig. S2B) (30). The cells were transduced with shRNA retrovirus vectors targeting GFP, Brm, BRG1, and REQ and selected using puromycin. Following lymphotoxin treatment of these stable transductants, BLC expression levels were determined by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. This lymphotoxin treatment experiment was performed three times (Fig. 4A, left, and supplemental Fig. S4), and the average of BLC expression levels was summarized after densitometric analysis (Fig. 4A, right panel). BLC expression was clearly induced in cells expressing the shGFP control (Fig. 4A, lane 5). In contrast, HT-29 cells stably expressing shREQ#1, shREQ#2, or shBrm marginally induced BLC after lymphotoxin treatment, whereas the introduction of shBRG1 had no effects upon the BLC expression levels (Fig. 4A, lanes 6–8). Importantly, lymphotoxin clearly induced the processing of p100 to p52 at a similar efficiency in all transductants (supplemental Fig. S5). Furthermore, lymphotoxin failed to induce BLC in HT-29 cells stably expressing shRelB (supplemental Fig. S6). These results indicate that the noncanonical NF-κB pathway is almost fully abolished at the transcriptional level by the loss of either REQ or Brm.

FIGURE 4.

REQ and the Brm-type SWI/SNF complex transactivate the BLC gene after lymphotoxin treatment by forming a larger complex with RelB/p52 in a ligand-dependent manner. A, BLC activation after lymphotoxin treatment requires either REQ or Brm in HT-29 cells. HT-29 cells were stably transduced with shBrm, shBRG1, shREQ, or shGFP (control) expressing retroviral vectors. After a 6-h treatment with LT (100 ng/ml) or no LT (+LT and −LT, respectively), total RNAs were extracted to determine the expression levels of the endogenous BLC and GAPDH genes by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. Similar LT treatment experiments were repeated two times, and the results of expression levels are shown in supplemental Fig. S4. Densitometric analysis of these three gels was summarized in the right panel after the expression levels were normalized relative to those of LT-treated shGFP-expressing cells, which were given a value of 1. The columns represent the average of triplicate experiments, and the bars indicate the standard deviation (except for shREQ#2). B, Brm, BRG1 and REQ do not affect IL8 activation by TNF-α. HeLaS3 cells stably transduced with vectors expressing shBrm, shBrg1, shREQ#1, and shGFP (control) were treated with or without 10 ng/ml TNF-α (+TNF-α and −TNF-α, respectively). After 3 h, total RNAs were extracted to determine expression levels of the endogenous IL8, Brm, BRG1, REQ, and GAPDH genes by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. C, chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis of HT-29 cells treated with lymphotoxin (100 ng/ml) for 6 h or untreated. Fragmented genomic DNA was immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-Brm, anti-BRG1, anti-REQ, or anti-RelB antibodies or normal rabbit IgG. After removal of the cross-links, DNA immunoprecipitates were used as PCR templates to detect the endogenous BLC, CD44, or GAPDH promoters. D, REQ and Brm interact with RelB/p52 in HT-29 cells. HT-29 cells stably transduced with a retrovirus vector expressing FLAG-REQ or nontransduced HT-29 cells were stimulated with 100 ng/ml lymphotoxin for 6 h or untreated. Nuclear fractions were then isolated and immunoprecipitated with anti-Brm, anti-BRG1, anti-REQ, and anti-RelB antibodies or normal rabbit IgG. Each immunoprecipitate was analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) using antibodies against FLAG, Brm, BRG1, BAF155, Ini1, RelB, or p100/p52.

We next evaluated the association of REQ and Brm with the natural canonical NF-κB activator TNF-α. HeLaS3 cells transduced with the same series of shRNA expression vectors described above were treated with TNF-α. A representative target gene of the NF-κB canonical pathway, IL8, was found to be induced by this treatment, but the IL8 mRNA levels were unaffected by the knockdown of either REQ or Brm, indicating that REQ does not significantly contribute to the NF-κB canonical pathway, at least in this cell system (Fig. 4B, lane 8). To next examine how lymphotoxin treatments may have altered the protein repertoire present at the BLC promoter in HT-29 cells, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments using antibodies against Brm, BRG1, RelB, and REQ. In the absence of lymphotoxin, none of these antibodies precipitated DNA fragments containing the BLC promoter above the levels of normal IgG. However, after lymphotoxin treatment, the anti-Brm, anti-BRG1, anti-REQ, and anti-RelB antibodies all precipitated BLC promoter fragments at significant levels (Fig. 4C), supporting our hypothesis that it is the Brm-type SWI/SNF complex that is linked with RelA/p52 via the recruitment of the REQ protein to this promoter upon LT treatment. To our surprise, however, the BRG-1 type SWI/SNF complex, which showed marginal transactivating activity toward this promoter (Fig. 4A), also seemed to be recruited in a similar manner to the CD44 promoter, which is known to be maintained by either Brm or BRG1 (31).

We next performed coimmunoprecipitation assays using HT-29 cells to further elucidate the interactions between both types of REQ-containing SWI/SNF complex and RelB/p52. Nuclear proteins were extracted from the cellular nuclear fraction HT-29 cells stably transduced with a FLAG-REQ retroviral vector using high salt buffers and then immunoprecipitated with normal rabbit IgG and with anti-Brm, anti-BRG1, anti-REQ and anti-RelB antibodies, respectively. Each immunoprecipitate was then analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-FLAG antibody (Fig. 4D). FLAG-REQ was found to be coimmunoprecipitated with Brm and BRG1 independently of lymphotoxin treatment (Fig. 4D, lanes 3, 4, 9, and 10). This is consistent with our initial observation that both Brm and BRG1 are immunoprecipitated by anti-REQ antibody from nontransduced HT29 cells without lymphotoxin treatment (Fig. 1B). FLAG-REQ was efficiently coimmunoprecipitated with RelB in lymphotoxin-treated HT-29 cells transduced with FLAG-REQ (Fig. 4D, lane 12). RelB was also immunoprecipitated by anti-Brm (Fig. 4D, lane 9) and anti-REQ (Fig. 4D, lane 11) antibodies but not by the anti-BRG1 antibody (Fig. 4D, lane 10) after nontransduced HT29 cells were treated with lymphotoxin. P52 was immunoprecipitated by anti-Brm antibody (Fig. 4D, lane 9) but not by anti-BRG1 antibody (Fig. 4D, lane 10) after lymphotoxin treatment. However, p52 detection using anti-p100/p52 mouse monoclonal antibody was hampered by cross-reactivity between the rabbit IgG (mouse) and anti-REQ (rabbit) antibody (Fig. 4D, lane 11). From these results, we speculate that both REQ and the Brm-type SWI/SNF complex stably bind to RelB/p52 in cellular nuclei after activation of the noncanonical NF-κB pathway. Our observation that the REQ activity linking the BRG1-type SWI/SNF complex with RelB/p52 is not stable, at least after nuclear protein extraction with high salt, might partly explain why the BRG1-type SWI/SNF complex does not have significant transactivating activity toward this promoter even though it is recruited.

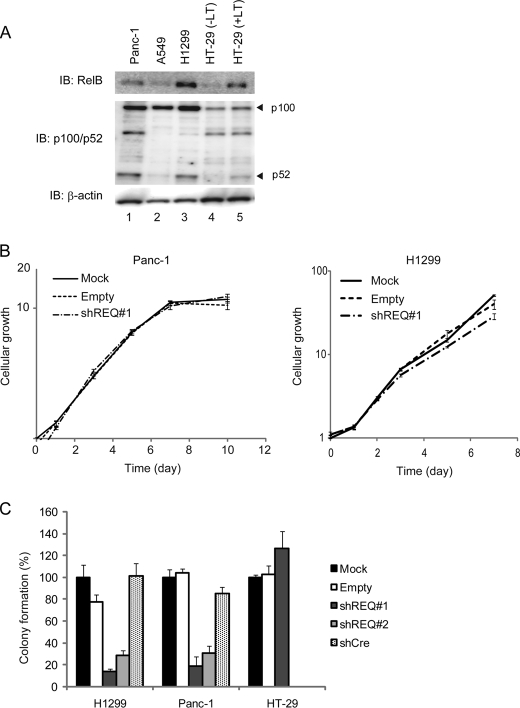

Suppression of Tumorigenicity by REQ Knockdown

Although a key role of the canonical NF-κB pathway in cancer has been well documented, the involvement of the noncanonical NF-κB pathway in tumor development and progression has only recently been revealed. In 2005, high constitutive nuclear levels of RelB were reported in prostate cancer (32). Furthermore, inhibition of RelB in an aggressive prostate cancer cell line significantly reduced the incidence and growth rate of the corresponding tumor xenografts (33). In pancreatic cancer cell lines such as Panc-1, a mediator of the noncanonical pathway, NF-κB-inducing kinase is significantly expressed and induces constitutive activation of this pathway (34). It has also been reported that pancreatic cancer cell lines display dramatically elevated levels of noncanonical NF-κB target genes, including ECL and BCL (35). Consistent with these observations, p52 and RelB were previously shown to be colocalized in pancreatic tumor tissues (35).

To evaluate whether REQ plays crucial roles in tumor cells in which the noncanonical NF-κB pathway is aberrantly regulated, we screened the levels of p52 and RelB in several human tumor cell lines by immunoblotting using Panc-1 cells as a positive control (Fig. 5A). Among the tumor lines tested, a human non-small cell carcinoma cell line H1299 showed high expression of p52 and RelB, which was comparable with that in the Panc-1 cells. HT-29 cells, however, only marginally expressed RelB and p52. We next introduced the shREQ#1 expression retrovirus vector into H1299 and Panc-1 cells and obtained stable transductants. Stable shREQ#1 expression did not affect cellular growth in either of the monolayer cultures (Fig. 5B). However, when the anchorage-independent growth of these transductants was tested in soft agar, a clear reduction in colony formation was observed upon expression of shREQ#1 as well as shREQ#2 (Fig. 5C). In addition, there were differences in the sizes of the colonies between shREQ#1- or shREQ#2-transduced cells and mock- or empty vector-transduced cells; the colonies formed by shREQ-expressing cells were smaller (data not shown). In HT-29 cells, which express marginal levels of RelB and p52, shREQ#1-transduced cells formed colonies that were very similar in number to the mock- and empty vector-transduced cells. These results indicate that the anti-oncogenic effects of shREQ are RelB/p52-dependent.

FIGURE 5.

REQ is required for the oncogenic activity induced by RelB/p52. A, immunoblotting (IB) analysis by anti-RelB, anti-p52/p100, and anti-actin (control) antibodies using whole cell extracts of several human tumor cell lines. HT-29 cells were treated without (−LT) or with (+LT) lymphotoxin for 6 h. B, REQ-knockdown in Panc-1 and H1299 cells does not affect their growth in monolayer cultures. Panc-1 and H1299 cells were stably transduced with shREQ#1-expressing retrovirus or empty control vectors. Each transduced population of cells was seeded into 96-well plates (1 × 103 cells/well), and cellular growth was assayed using a Cell-Titer Glo assay kit. Cellular growth was measured as a ratio of the corresponding mock-infected cells at day 0. The values shown are the average of triplicate experiments, and the bars indicate the standard deviations. C, REQ is required for the anchorage-independent growth of Panc-1 and H1299 cells. Panc-1, H1299, and HT-29 cells stably transduced with shREQ#1 and shREQ#2 retroviral vectors as well as an empty vector were transferred into soft agar plates. After 3 weeks, the numbers of colonies were counted using at least three plates. The values were shown as a percentage of the colony numbers in the corresponding mock-infected cells. The columns represent the average values of two independent experiments, and the bars indicate the standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

Our current findings indicate that REQ is a novel adaptor protein that links the Brm-type SWI/SNF complex and RelB/p52 and operates at the most downstream stages of the noncanonical NF-κB pathway. In addition, the Brm-type SWI/SNF complex and REQ form a larger complex with RelB/p52 in a lymphotoxin-dependent manner (Fig. 4D), and the knockdown of either Brm or REQ results in the loss of induction of a noncanonical NF-κB target gene, BLC, in lymphotoxin-treated HT-29 cells (Fig. 4A). The preferential binding of REQ to the RelB/p52 dimer is supported by its direct binding to p52 in our in vitro pulldown assay (Fig. 3A). REQ also shows a weak affinity for RelA, RelB, and c-Rel synthesized in vitro and slight transactivation activity in a RelA/p50-dependent luciferase activity (Fig. 2A). It is possible therefore that REQ interacts with these proteins more strongly when they are specifically modified at the post-translational level and function also in some other NF-κB pathways in some cell types.

REQ was found in an in vitro pulldown assay to bind to either Brm or BRG1 with a similar affinity (Fig. 1C). In addition, both the Brm-type and BRG1-type SWI/SNF complexes isolated in vivo contain REQ (Fig. 1B). In HT-29 cells, either type of SWI/SNF complex seems to be recruited to the BLC promoter region upon lymphotoxin treatment in a similar manner to RelB/p52 and REQ, possibly via the REQ binding activity toward the p52 protein that we observed in vitro. Importantly, however, only the Brm-type SWI/SNF complex can effectively transactivate genes through RelB/p52 (Fig. 2A), and this complex is required for noncanonical NF-κB activation by lymphotoxin (Fig. 4A). Our observation in lymphotoxin-treated HT-29 cells that the Brm-type but not the BRG1-type SWI/SNF complex forms a stable complex with RelB/p52 (Fig. 4D) when extracted from cellular nuclei with high salts might partly explain why BRG1-type SWI/SNF complex has only marginal BLC transactivating activity (Fig. 4A) even though it is recruited to the promoter (Fig. 4C). The molecular mechanisms underlying the selectivity of these two alternative catalytic subunits of SWI/SNF complex in NF-κB transactivation will require further analysis from the standpoint of chromatin dynamics. In this regard, however, it is worth pointing out that we previously observed similar phenomena, i.e. Brm but not BRG1 is required for Cdx2-dependent villin activation in gastrointestinal cells, whereas Cdx2 can bind either Brm or BRG1 in vitro (8). It remains possible that BRG1 play some roles in NF-κB transactivation, because previous studies using a mouse macrophage cell line treated with lipopolysaccharide have shown that the BRG1-type SWI/SNF complex is involved in the transactivation of specific promoters containing NF-κB-binding sites (14, 15).

The REQ regions that bind to several SWI/SNF subunits and the NF-κB p52 protein reside within its N-terminal region (Fig. 3D). This suggests that the C-terminal region of REQ, which contains two tandem PHD repeats, is responsible for other biochemical functions. As the PHD domains in DPF3 and NURF301 proteins have been reported to bind to acetylated and methylated histones, respectively (20, 36), the REQ PHDs may exert a transactivation function by linking the large complex composed of SWI/SNF, REQ, and RelB/p52 to nucleosomes that contain specifically modified histone tails. Importantly, the core components of the SWI/SNF complexes have no PHD finger domains, whereas many other chromatin remodeling complexes, for example ISWI (37, 38) and Mi-2β (36, 39), do contain subunits with PHD domains. In our current experiments, REQ-dependent luciferase reporter gene expression was detectable only when the gene was stably integrated but transiently introduced. This may reflect the fact that REQ is sensitive to natural chromatin structures for recognition and subsequent activation of genes in a relatively inactive context for chromatin.

We finally show a critical function of REQ in oncogenesis by the constitutive activation of a noncanonical NF-κB pathway (Fig. 5C). It is also interesting that a significant but not complete suppression of REQ expression by shRNA (supplemental Fig. S2B) efficiently blocked anchorage-independent growth without affecting cellular growth in monolayer cultures. We conclude from this that the REQ levels necessary for oncogenic activity are much higher than those sufficient to support normal growth, as we previously observed for AP-1 (40). This is an advantageous aspect of the targeting of REQ in future therapeutic applications as it is possible that such an approach would produce low side effects in normal cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Kitamura for providing the PLAT packaging cell line and S. Kawaura and A. Kato for their assistance in preparing this manuscript. The Panc-1, A-549, and HeLa-S3 and 293 cell lines were obtained from the Cell Resource Center for Biomedical Research, Institute of Development, Aging, and Cancer, Tohoku University, Japan.

This work was supported in part by Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas 17016015 from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan and in part by the strategic cooperation to control emerging and reemerging infections funded by the Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology of the Ministry of Education, Cultures, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental “Experimental Procedures,” Figs. S1–S6, Table S1, and an additional reference.

- NF-κB

- nuclear factor κB

- DPF

- D4 zinc and double PHD finger family

- PHD

- plant homeodomain

- TNF

- tumor necrosis factor

- IκB

- inhibitor of κB

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- LC-MS

- liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

- LT

- lymphotoxin

- shRNA

- short hairpin RNA

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- RT

- reverse transcription.

REFERENCES

- 1.Muchardt C., Yaniv M. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 293, 187–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martens J. A., Winston F. (2003) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 13, 136–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang W., Côté J., Xue Y., Zhou S., Khavari P. A., Biggar S. R., Muchardt C., Kalpana G. V., Goff S. P., Yaniv M., Workman J. L., Crabtree G. R. (1996) EMBO J. 15, 5370–5382 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laurent B. C., Treich I., Carlson M. (1993) Genes Dev. 7, 583–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mizutani T., Ito T., Nishina M., Yamamichi N., Watanabe A., Iba H. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 15859–15864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iba H., Mizutani T., Ito T. (2003) Rev. Med. Virol. 13, 99–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mizutani T., Ishizaka A., Tomizawa M., Okazaki T., Yamamichi N., Kawana-Tachikawa A., Iwamoto A., Iba H. (2009) J. Virol. 83, 11569–11580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamamichi N., Inada K. I., Furukawa C., Sakurai K., Tando T., Ishizaka A., Haraguchi T., Mizutani T., Fujishiro M., Shimomura R., Oka M., Ichinose M., Tsutsumi Y., Omata M., Iba H. (2009) Exp. Cell Res. 315, 1779–1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ito T., Yamauchi M., Nishina M., Yamamichi N., Mizutani T., Ui M., Murakami M., Iba H. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 2852–2857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonizzi G., Karin M. (2004) Trends Immunol. 25, 280–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen L. F., Greene W. C. (2004) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 392–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vallabhapurapu S., Karin M. (2009) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27, 693–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dejardin E., Droin N. M., Delhase M., Haas E., Cao Y., Makris C., Li Z. W., Karin M., Ware C. F., Green D. R. (2002) Immunity 17, 525–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kayama H., Ramirez-Carrozzi V. R., Yamamoto M., Mizutani T., Kuwata H., Iba H., Matsumoto M., Honda K., Smale S. T., Takeda K. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 12468–12477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramirez-Carrozzi V. R., Nazarian A. A., Li C. C., Gore S. L., Sridharan R., Imbalzano A. N., Smale S. T. (2006) Genes Dev. 20, 282–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ito T., Watanabe H., Yamamichi N., Kondo S., Tando T., Haraguchi T., Mizutani T., Sakurai K., Fujita S., Izumi T., Isobe T., Iba H. (2008) Biochem. J. 411, 201–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gabig T. G., Mantel P. L., Rosli R., Crean C. D. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 29515–29519 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chestkov A. V., Baka I. D., Kost M. V., Georgiev G. P., Buchman V. L. (1996) Genomics 36, 174–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lessard J., Wu J. I., Ranish J. A., Wan M., Winslow M. M., Staahl B. T., Wu H., Aebersold R., Graef I. A., Crabtree G. R. (2007) Neuron 55, 201–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lange M., Kaynak B., Forster U. B., Tönjes M., Fischer J. J., Grimm C., Schlesinger J., Just S., Dunkel I., Krueger T., Mebus S., Lehrach H., Lurz R., Gobom J., Rottbauer W., Abdelilah-Seyfried S., Sperling S. (2008) Genes Dev. 22, 2370–2384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dignam J. D., Lebovitz R. M., Roeder R. G. (1983) Nucleic Acids Res. 11, 1475–1489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Natsume T., Yamauchi Y., Nakayama H., Shinkawa T., Yanagida M., Takahashi N., Isobe T. (2002) Anal. Chem. 74, 4725–4733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujita S., Ito T., Mizutani T., Minoguchi S., Yamamichi N., Sakurai K., Iba H. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 378, 492–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arai T., Matsumoto K., Saitoh K., Ui M., Ito T., Murakami M., Kanegae Y., Saito I., Cosset F. L., Takeuchi Y., Iba H. (1998) J. Virol. 72, 1115–1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watanabe H., Mizutani T., Haraguchi T., Yamamichi N., Minoguchi S., Yamamichi-Nishina M., Mori N., Kameda T., Sugiyama T., Iba H. (2006) Oncogene 25, 470–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamamichi N., Inada K., Ichinose M., Yamamichi-Nishina M., Mizutani T., Watanabe H., Shiogama K., Fujishiro M., Okazaki T., Yahagi N., Haraguchi T., Fujita S., Tsutsumi Y., Omata M., Iba H. (2007) Cancer Res. 67, 10727–10735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacKay C., Toth R., Rouse J. (2009) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 390, 187–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tréand C., du Chéné I., Brès V., Kiernan R., Benarous R., Benkirane M., Emiliani S. (2006) EMBO J. 25, 1690–1699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonizzi G., Bebien M., Otero D. C., Johnson-Vroom K. E., Cao Y., Vu D., Jegga A. G., Aronow B. J., Ghosh G., Rickert R. C., Karin M. (2004) EMBO J. 23, 4202–4210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mackay F., Majeau G. R., Hochman P. S., Browning J. L. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 24934–24938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reisman D. N., Strobeck M. W., Betz B. L., Sciariotta J., Funkhouser W., Jr., Murchardt C., Yaniv M., Sherman L. S., Knudsen E. S., Weissman B. E. (2002) Oncogene 21, 1196–1207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lessard L., Bégin L. R., Gleave M. E., Mes-Masson A. M., Saad F. (2005) Br. J. Cancer 93, 1019–1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu Y., Josson S., Fang F., Oberley T. D., St Clair D. K., Wan X. S., Sun Y., Bakthavatchalu V., Muthuswamy A., St Clair W. H. (2009) Cancer Res. 69, 3267–3271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishina T., Yamaguchi N., Gohda J., Semba K., Inoue J. (2009) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 388, 96–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wharry C. E., Haines K. M., Carroll R. G., May M. J. (2009) Cancer Biol. Ther. 8, 1567–1576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wysocka J., Swigut T., Xiao H., Milne T. A., Kwon S. Y., Landry J., Kauer M., Tackett A. J., Chait B. T., Badenhorst P., Wu C., Allis C. D. (2006) Nature 442, 86–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Badenhorst P., Voas M., Rebay I., Wu C. (2002) Genes Dev. 16, 3186–3198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eberharter A., Vetter I., Ferreira R., Becker P. B. (2004) EMBO J. 23, 4029–4039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Musselman C. A., Mansfield R. E., Garske A. L., Davrazou F., Kwan A. H., Oliver S. S., O'Leary H., Denu J. M., Mackay J. P., Kutateladze T. G. (2009) Biochem. J. 423, 179–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ui M., Mizutani T., Takada M., Arai T., Ito T., Murakami M., Koike C., Watanabe T., Yoshimatsu K., Iba H. (2000) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 278, 97–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.