Abstract

Heme is a vital molecule for all life forms with heme being capable of assisting in catalysis, binding ligands, and undergoing redox changes. Heme-related dysfunction can lead to cardiovascular diseases with the oxidation of the heme of soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) critically implicated in some of these cardiovascular diseases. sGC, the main nitric oxide (NO) receptor, stimulates second messenger cGMP production, whereas reactive oxygen species are known to scavenge NO and oxidize/inactivate the heme leading to sGC degradation. This vulnerability of NO-heme signaling to oxidative stress led to the discovery of an NO-independent activator of sGC, cinaciguat (BAY 58–2667), which is a candidate drug in clinical trials to treat acute decompensated heart failure. Here, we present crystallographic and mutagenesis data that reveal the mode of action of BAY 58–2667. The 2.3-Å resolution structure of BAY 58–2667 bound to a heme NO and oxygen binding domain (H-NOX) from Nostoc homologous to that of sGC reveals that the trifurcated BAY 58–2667 molecule has displaced the heme and acts as a heme mimetic. Carboxylate groups of BAY 58–2667 make interactions similar to the heme-propionate groups, whereas its hydrophobic phenyl ring linker folds up within the heme cavity in a planar-like fashion. BAY 58–2667 binding causes a rotation of the αF helix away from the heme pocket, as this helix is normally held in place via the inhibitory His105–heme covalent bond. The structure provides insights into how BAY 58–2667 binds and activates sGC to rescue heme-NO dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases.

Keywords: Crystal Structure, Cyclic GMP (cGMP), Guanylate Cyclase (Guanylyl Cyclase), Heme, Nitric Oxide

Introduction

Heme is a key evolutionarily conserved cofactor involved in many processes ranging from signal transduction, gas transport, circadian rhythm, microRNA processing, and drug metabolism (1–3). Heme, as part of NO signaling through sGC,2 is critical for regulation of cardiovascular processes via cGMP-dependent pathways, making sGC a prime drug target in cardiovascular diseases (4). sGC is a heterodimeric protein, mostly in the α1β1 isoform, that stimulates the production of cGMP upon NO activation (5). Under normal physiological conditions, NO-activated sGC stimulates vasodilation and is required for platelet disaggregation as well as neurotransmission (6). During the pathophysiological conditions of oxidative stress common to vascular disease, the NO-sGC signaling pathway is disrupted due to sGC desensitization and degradation of sGC upon heme loss, thus limiting the extent to which traditional treatment methods such as nitroglycerin can increase sGC activity (7). BAY 58–2667 can overcome these defects by activating sGC and protecting heme-oxidized sGC from proteasomal degradation (4, 8). These beneficial characteristics contributed to the pharmaceutical potential of BAY 58–2667, and this compound is in clinical trials to treat acute decompensated heart failure (9–11). The initial steps of BAY 58–2667 activation of sGC are fundamentally distinct from activation by NO (Fig. 1). NO binds a 5-coordinated His105-liganded heme, forming a brief 6-coordinated intermediate and subsequently causing breakage of the Fe–His105 bond to yield a 5-coordinated NO-bound heme in the activated state (Fig. 1B). In contrast, BAY 58–2667 activation of sGC is heme-independent yet takes place in the NO sensory H-NOX domain of sGC when it is heme-depleted (Fig. 1C) (12). This crucial H-NOX domain is the N-terminal domain of the sGCβ1 subunit, which is adjacent to a Per-Armt-Sim (PAS-like) H-NOXA domain, followed by a coiled-coil domain, and the C-terminal catalytic guanylyl cyclase domain. The sGCα1 subunit has a similar domain arrangement, except that its N-terminal domain does not bind heme. sGC has not been amendable to crystallization, and structural studies of sGC have therefore been limited to individual domains of homologous proteins (13–16). The H-NOX domain used in these studies that is most homologous to the H-NOX domain of sGC is Nostoc sp. H-NOX (Ns H-NOX), which shares 35% sequence identity with sGC, having similar properties including its ability to bind CO and NO (supplemental Fig. 1) (13). We present here the 2.3-Å crystal structure of the Ns H-NOX·BAY 58–2667 complex and mutational results revealing insights into the molecular mechanisms of sGC activation by a heme mimetic.

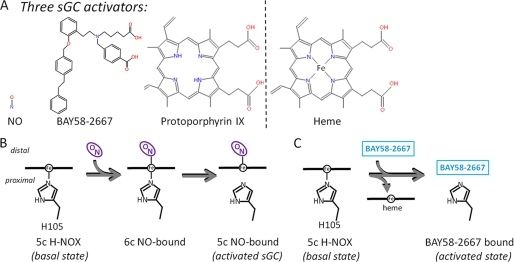

FIGURE 1.

sGC activators and their mechanism of activation. A, chemical structures of three sGC activators: nitric oxide (NO), BAY 58–2667, and protoporphyrin IX. For comparison, the molecular structure of heme, which is not an activator because it can form a covalent inhibitory bond with His105 via its iron atom, is also shown. B, NO activation of sGC via binding of NO to the distal face of the 5-coordinated (5c) heme leads to breakage of the proximal Fe–His105 bond, a critical step in NO activation. C, activation of sGC by BAY 58–2667 requires displacement of the heme such that BAY 58–2667 can now occupy the heme pocket. This heme removal is facilitated by weakening of the Fe–His105 bond by heme oxidation. 6c, 6-coordinated.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Preparation of the BAY 58–2667·H-NOX Complex

We expressed and purified a C-terminally truncated version of Nostoc sp. H-NOX comprising residues 1–183 similarly as described previously for the full-length 1–187 protein (13). The heme was replaced by BAY 58–2667 by adding a 10-fold molar excess of the heme oxidizer NS-2028 (Alexis Biochemicals) and 5-fold molar excess of BAY 58–2667 (obtained from Dr J. P. Stasch, Bayer Schering Pharma AG) at 37 °C prior to Superdex 75 chromatography to remove the displaced heme and unbound BAY 58–2667.

Crystallization and Structure Determination

Colorless crystals of the Ns HNOX domain bound to BAY 58–2667 were obtained using sitting drop crystallization at room temperature with a protein concentration of ∼10 mg/ml and a well solution of 1.8 m sodium malonate at pH 7.3. Crystals were cryoprotected in 3.0 m sodium malonate, pH 7.3, prior to dunking the crystal in liquid nitrogen. Data were collected at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource beamline 11-1 to 2.3-Å resolution and processed using HKL2000 (17). Crystals of BAY 58–2667 bound HNOX were in the same space group as for the heme-bound protein with two molecules in the asymmetric unit. Twinning analysis revealed a twinning fraction of close to 0.5 (18), which was refined in REFMAC (19) using the amplitude-based twin refinement with the H-NOX coordinates, without the heme, as the starting model (Protein Data Bank code 2O09; 13). The structure was subsequently refined using alternating cycles of fitting using COOT (20) and REFMAC. Heme density was absent, yet strong density for the two copies of BAY 58–2667 was present after the initial refinement. Subsequently, two BAY 58–2667 molecules were added in refinement using a stereochemistry library file that was generated with PRODRG (21). The structure was refined to a final R-factor of 0.150 with an Rfree of 0.193 and validated using PROCHECK (22). Data collection and refinement statistics are listed in Table 1. Figures are generated using PyMOL.

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics for Ns H-NOX complexed with BAY 58–2667

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Data collection | |

| Wavelength | 0.97945 |

| Space group | P213 |

| Cell dimensions (Å) | 123.27, 123.27, 123.27, 90, 90, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50–2.3 (2.36–2.30) |

| Total observations | 177,581 |

| Unique observations | 27,835 |

| I/σI | 25.0 (1.9) |

| Redundancy | 6.4 (4.6) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.5 (97.0) |

| Rsym (%) | 5.8 (75.8) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 50–2.3 |

| No. of protein atoms | 2866 |

| No. of solvent | 82 |

| No. of ligand atoms | 84 |

| R-factor (%) | 15.0 |

| Rfree (%) | 19.3 |

| r.m.s.d. | |

| For bond lengths (Å) | 0.008 |

| For bond angles | 1.13° |

| Ramachandran plot statistics (%) | |

| Residues in most favored regions | 94 |

| Residues in additional allowed regions | 5.1 |

| Residues in generously allowed regions | 0 |

| Residues in disallowed regions | 0 |

| Average B-factors (Å2) | |

| Protein | 54.3 |

| Ligand | 57.8 |

| Solvent | 53.9 |

Site-directed Mutagenesis

cDNAs encoding the α1 and β1 subunits of rat guanylyl cyclase, cloned into the mammalian expression vector pCMV5, served as the templates for site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange, Stratagene) to generate sGCβ1 R40A, β I111A, and β R116A mutations.

Expression in COS-7 Cells of WT and Mutant sGC

COS-7 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, penicillin, and streptomycin (100 units/ml). Cells were transfected with SuperFectTM reagent using the protocol of the supplier (Qiagen). Cells (100-mm dish) were transfected with 10 μg of plasmid encoding each wild-type or mutated subunit. After 40 h, cells were washed twice with 5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline.

Cytosolic Preparation

After washes, cells are scraped off the plate in cold lysis buffer: phosphate-buffered saline buffer contained protease inhibitors, 50 mm HEPES (pH 8.0), 1 mm EDTA, and 150 mm NaCl. Cells were broken by sonication (three pulses of 3 s). The resulting lysate was centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to collect the cytosol.

sGC Activity Assay

sGC activity was determined by formation of [α-32P]cGMP from [α-32P]GTP, as described previously (23). Reactions were performed for 5 min at 33 °C in a final volume of 100 μl, in a 50 mm HEPES, pH 8.0, reaction buffer containing 500 μm GTP, 1 mm dithiothreitol, and 5 mm MgCl2. Typically, 40 μg of cell cytosol was used in each assay reaction. Enzymatic activity was stimulated with the NO donor S-nitroso-N-acetyl-penicillamine (SNAP) (Calbiochem) at 100 μm. sGC activity is expressed in pmol/min mg.

RESULTS

To obtain the BAY 58–2667·Ns H-NOX complex, the heme of Ns H-NOX was first oxidized with the sGC-specific heme oxidizer NS-2028 (4H-8-bromo-1,2,4-oxadiazolo(3,4-d) benz(b)(1,4)oxazin-1-one); the heme was replaced by adding excess of BAY 58–2667 (cinaciguat; 4-((4-carboxybutyl)(2-((4-phenethylbenzol)oxy) phenethyl) amino)methyl(benzoic) acid). Subsequent crystallization and structure determination yielded the 2.3-Å resolution crystal structure of Ns H-NOX bound to BAY 58–2667 with two copies in the asymmetric unit (Table 1 and Fig. 2).

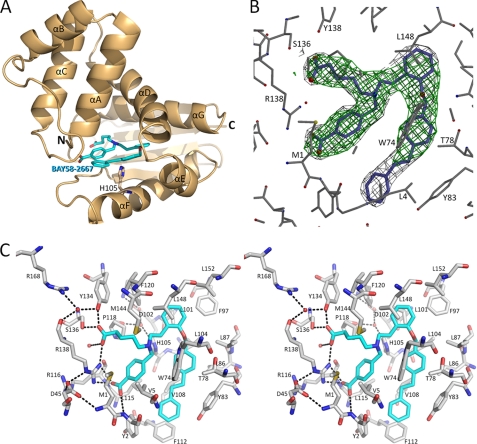

FIGURE 2.

Structure of BAY 58–2667 bound to H-NOX. A, Ns H-NOX (gold ribbon diagram) bound to BAY 58–2667 (blue stick structure). Also shown is the side chain of His105 (stick) that is part of the αF helix. B, electron density of BAY 58–2667. Unbiased 2.3-Å resolution | Fo| − |Fc| omit density (green, contoured at 3σ) and the final refined 2|Fo| − |Fc| density (dark gray, contoured at 1.25σ) are shown. C, stereo figure showing interactions of BAY 58–2667 with nearby H-NOX residues. Hydrogen bonds are shown as dashed lines.

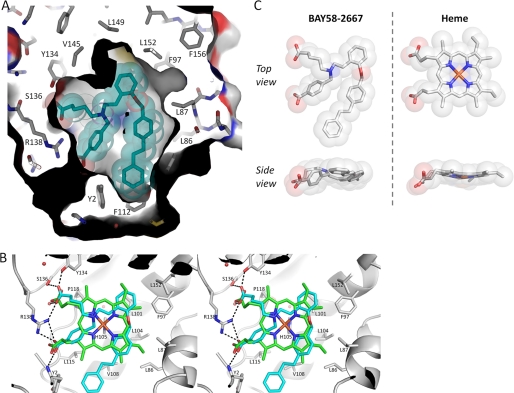

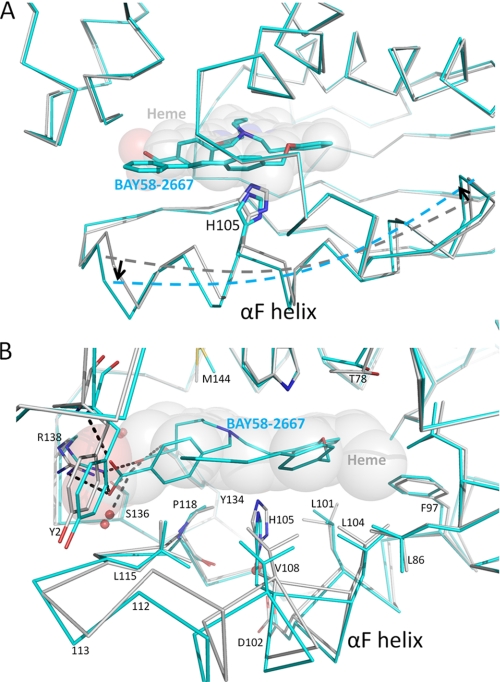

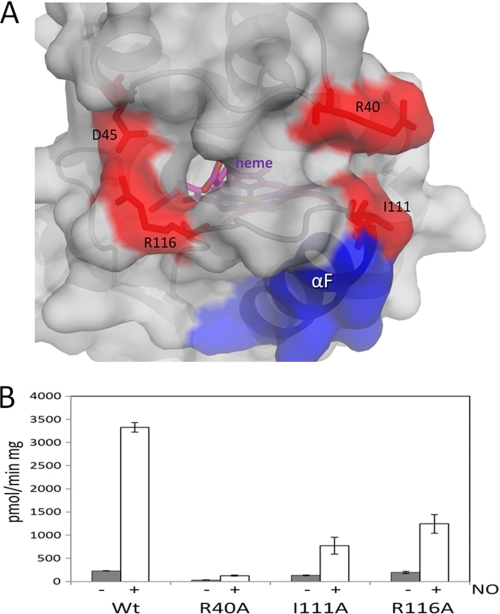

Electron difference density in the heme-binding pockets of each copy clearly revealed the trifurcated BAY 58–2667 ligand density (Fig. 2B). The two carboxylate groups of BAY 58–2667 make extensive interactions: the carboxy-butyl moiety interacts with the side chains of Tyr134, Ser136, and Arg138, whereas the carboxylate moiety of the benzoic acid interacts with Arg138 and the main chain nitrogen of Tyr2 (Fig. 2C). Both copies of BAY 58–2667 in the asymmetric unit have a similar binding mode, although one of the carboxylates is slightly rotated (supplemental Fig. 2). Electron density for the third moiety of BAY 58–2667 extending from the tertiary amine, the extended tri-benzyl ring containing moiety, is well defined except for the terminal benzyl ring (Fig. 2B); the orientations for this terminal benzyl ring also vary slightly between the two crystallographic copies (supplemental Fig. 2). This hydrophobic third branch of BAY 58–2667 makes extensive hydrophobic interactions with residues forming the rest of the heme cavity including Leu4, Trp74, Thr78, Lys83, Phe97, Leu101, Leu104, Val108, Leu148, and Leu152 (Fig. 2C). Finally, the trifurcated tertiary amine is 4.1 Å from Trp71, apparently forming a cation/pi interaction of the positively charged amine and the pi clouds of the tryptophan. Despite having a shape dissimilar to heme, the trifurcated BAY 58–2667 folds up and occupies the heme cavity with its carboxylate groups superimposing on those of the heme propionate groups in the apo-Ns H-NOX structure (Fig. 3) published previously (13). BAY 58–2667, therefore, mimics heme in that it contains two hydrophilic charged carboxylates that interact with the YxSxR motif found to be crucial for heme and BAY 58–2667 binding (12, 24), yet, on the other hand, it is mostly hydrophobic and can “fold” in a somewhat planar heme-like fashion (Fig. 3C). A key functional difference between the two molecules is that BAY 58–2667 is a sGC activator, whereas heme is an inhibitor as the latter forms the covalent inhibitory bond with His105 (that normally is broken via NO binding). The Ns H-NOX structure with BAY 58–2667 in the activated state reveals a 3° rotation of the αF helix, normally tethered by the heme via His105, as analyzed by the program ESCET (Fig. 4 and supplemental movie) (25). This rotation culminates in a ∼1-Å shift of the carboxyl terminus of αF comprising residues 110–111 (see supplemental movie). NO activation of sGC would likely induce a similar conformational change of αF as NO-heme binding causes the breakage of the αF-His105–Fe bond (26) and would allow this helix to shift to alleviate the steric clashes between the heme and His105 due to van der Waals repulsion interactions. This conformational change distorts the surface region comprising residues 110–116 and nearby flanking residues 40–46 (Fig. 4, A and B) and highlights a region that is likely to be used by H-NOX to transmit its activation signal to the rest of sGC upon NO or BAY 58–2667 activation. We therefore probed the importance of this region for sGC activation via alanine-scanning mutagenesis of surface-exposed H-NOX residues Arg40, Ile111, and Arg116. WT and mutant versions of sGC were expressed in COS-7 cells, and their guanylyl cyclase activity was assayed (Fig. 5B), revealing that these residues affect NO-stimulated activity. Mutation of residues Ile111 and Arg116 have an ∼4- and 3-fold, respectively, effect on maximal sGC activation, whereas mutation of residue Arg40 has the largest effect on NO-stimulated and basal sGC activity (Fig. 5B). These results suggests that sGC residues Arg40, Ile111, and Arg116 play a role in communicating H-NOX conformational changes to the rest of sGC and that there are likely some similarities between BAY 58–2667 and NO activation of sGC.

FIGURE 3.

BAY 58–2667 binds to H-NOX heme cavity and mimics heme/protein interactions. A, binding of BAY 58–2667 (cyan sticks and transparent spheres) to heme cavity. B, stereo figure showing superposition of BAY 58–2667 (cyan) and heme (green) as bound to H-NOX structures. (Only the protein for the BAY 58–2667 complex structure is depicted for clarity.) Hydrogen bond interactions by the carboxylates of BAY 58–2667 with the YxSxR motif residues are shown as dashed lines. C, structural comparison of BAY 58–2667 and heme (in their conformation when bound to H-NOX).

FIGURE 4.

H-NOX conformational changes upon BAY 58–2667 activation. A, superposition of BAY 58–2667 H-NOX structure (cyan) onto the heme H-NOX structure (gray). (Heme is depicted as transparent spheres.) Proteins are shown as Cα traces revealing the rotation of the αF helix as illustrated by the broken lines along the helix axes and the black arrows pointing in the direction of the rotation. B, close-up view of the H-NOX shifts upon BAY 58–2667 activation. Most prominent are the ∼0.7-Å downward shift of His105 in the middle of the αF helix and the ∼1.0-Å shift of Phe112 at the C-terminal end of αF.

FIGURE 5.

Mutagenesis of the postulated communicating activation region of the H-NOX domain in sGC. A, close-up surface view of sGC H-NOX domain homology model showing relative orientation of residues 40–45 and 111–116 (pink). The observed activation shift of helix αF (blue), including residues Ile111 (red), would cause subsequent shifts in this region hypothesized to be sensed by the rest of sGC. Surface residues targeted for mutagenesis are shown in red, and the heme is shown in magenta sticks. B, basal (gray) and NO-stimulated (white) WT and sGC mutants expressed in COS-7 cells. Basal activities were similar between WT and mutants but not for R40A (for which basal activity was close to background values). NO-stimulated activity of cytosols showed that mutants have a reduced response to NO stimulation compared with WT. The NO donor SNAP was used at 100 μm. Experiments were repeated three times, from two independent transfections, with each measurement done in duplicate and expressed in pmol/min·mg ± S.E.

DISCUSSION

Our results regarding the 2.3-Å resolution structure of BAY 58–2667 bound to Ns H-NOX reveals the molecular details of the remarkable ability of BAY 58–2667 to activate heme-depleted sGC. By being able to mimic the heme yet avoid forming a covalent inhibitory bond with His105, BAY 58–2667 is able to bind to the heme pocket and yet allow the conformational activation change involving helix αF and its His105 residue. The largest shifts of the BAY 58–2667-bound Ns H-NOX structure compared with the heme-bound structure are in the C-terminal part of helix αF (Fig. 4). We postulate that this region, near residue 111, and the flanking region comprising residues 40–46 are therefore likely involved in communicating the activation conformational changes of the H-NOX domain to the rest of sGC. The importance of this region for sGC activation was probed by mutagenesis and indicated that the β1 H-NOX mutations R40A, I111A, and R116A negatively affect NO-stimulated cyclase activity (Fig. 5). Because these residues are mostly solvent exposed and not involved in direct heme binding or domain folding, these residues are likely involved in direct H-NOX/GC interactions (such a direct H-NOX/GC interdomain interaction had been previously observed (27)). In earlier work, residue Asp45 also was found to be important in sGC activation (28); this residue also falls within this surface region providing additional support for the proposed activation relevance of this region near residues 110–116 and 40–46. Future structural studies are needed to indeed confirm such a direct interaction between these sGC domain and also what the differences and similarities of the NO-bound 5-coordinated sGC structure is compared with BAY 58–2667.

Structure-Activity Relationship of BAY 58–2667

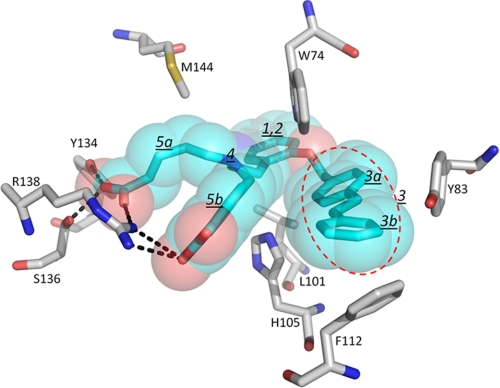

BAY 58–2667 is the result of substantial structure-activity relationship optimization (9), and its critical features agree well with its H-NOX binding mode and induced conformational activation changes (Fig. 6). A large number of BAY 58–2668 derivatives have been generated and their likely structural consequence within the H-NOX binding pocket, and their effects on rabbit saphenous arteries, will be correlated next. First, the pivot point of the BAY 58–2667 induced helix rotation of αF is near residue Leu101, a well conserved residue in sGCβ1. Leu101 interacts with the phenyl ring of the phenethylamino moiety of BAY 58–2667 (ring labeled 1 in Fig. 6), a group found to be key for BAY 58–2267 activity (9). Second, this phenyl moiety is in a hydrophobic internal H-NOX region, which explains why ring nitrogens introduced to convert the phenyl (labeled 2 in Fig. 6) to a heterocycle cannot be accommodated without negatively impacting the IC50 (9). Third, there is considerable variability possible with respect to the linker length of the terminal hydrophobic group being 4-phenethylbenzol in BAY 58–2667 (red oval labeled 3 in Fig. 6). Having just one phenyl ring at this position yields a potent sGC activator, although filling up the H-NOX cavity via longer linkers and having a second linearly connected phenyl ring (labeled 3b in Fig. 6) improve the IC50 values. In contrast, widening this linker at the nonterminal phenyl ring (labeled 3a in Fig. 6) or adding polar atoms to this linker moiety have negative effects likely due to the only narrow and hydrophobic space available to this moiety, which is flanked by Tyr83 and its own benzoic acid moiety (labeled 5b in Fig. 6) (9). These observations are in accord with our structure, which shows flexibility in the terminal BAY 58–2667 phenyl moiety and partial displacement of Phe112, suggesting that variations there can be accommodated with even longer variants such as BAY 60–2770 (9). Fourth, being released from the covalent bond with the heme, the His105 residue is pushed down ∼0.6–0.7 Å by the ethylamino moiety (labeled 4 in Fig. 6; Fig. 4). This latter group contains the trifurcated chiral branch atom of BAY 58–2667, the correct chirality at this position, and therefore likely also how far His105 is pushed away, has a major impact on its IC50 (9). Finally, the BAY 58–2667 structure also explains why the butyl-carboxylate (Fig. 6, 5a) is more important compared with the methyl-benzoic acid (Fig. 6, 5b) because replacing the latter with a hydrogen leads to only a 63-fold IC50 increase, whereas replacing the former leads to a drastic 4800-fold increase (9). The BAY 58–2667 H-NOX structure shows that the butyl-carboxylate makes key interactions with all three of the pivotal YxSxR motif residues known to be crucial for BAY 58–2667 activation (24, 28) holding this H-NOX region in place, whereas the benzoic acid carboxylate only interacts with Arg138 and the backbone nitrogen of Tyr2 (Fig. 2C). The dominance and importance of one of the carboxylates explains the potency of recently developed sGC activators with only one carboxylate, as described in a recent U.S. patent application (29). In summary, this analysis shows that two of the most critical features of BAY 58–2667 are its butyl-carboxylate moiety, which interacts with the YxSxR motif, and a long hydrophobic tail that can bend and occupy the mostly hydrophobic heme pocket. This analysis suggests that our BAY 58–2667 complex structure is a great tool for analyzing current analogs and likely also future analogs of BAY 58–2667.

FIGURE 6.

Structure-function analysis of BAY 58–2667 derivatives. Close-up view of BAY 58–2667 bound to heme pocket of Ns H-NOX. Hydrogen bonds are depicted as black dashed lines. Heme pocket residues important for explaining the SAR relationships of BAY 58–2667 analogs are also depicted. Individual chemical moieties of BAY 58–2667 are labeled 1–5 and are described under “Discussion.”

In summary, the Ns H-NOX protein continues to be a great tool for understanding sGC. In addition to being the closest bacterial homolog to the H-NOX domain of sGC in terms of sequence and ligand binding (13), we show here that Ns H-NOX is, like sGC, capable of having its heme displaced by the sGC activator BAY 58–2667 and that the observed binding mode of BAY 58–2667 strongly correlates with the published sGC structure activity relationships (SAR) data on BAY 58–2667 analogs (Fig. 6). In addition, the BAY 58–2667 binding mode is in agreement and structurally explains previous mutagenesis results that pointed to the strong role for the YxSxR motif present in both sGC and Ns H-NOX (12, 24). And finally, the BAY 58–2667 induced shift of the His105-containing αF helix and adjacent loop point to the importance of the surface patch comprised of regions 110–116 (and flanking residues 40–46), which we subsequently probed with sGC mutagenesis experiments (Fig. 5). These combined results point to the importance of this surface region for sGC activation by BAY 58–2667, which possibly shares some mechanistic similarities with NO activation of sGC. These cohesive results therefore aid in our understanding of sGC activation by a heme-mimetic and how BAY 58–2667 protects sGC from degradation by stabilizing the heme cavity and offer new structure-based design strategies to pharmaceutically further target the sGC protein to treat certain cardiovascular diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Rebecca Alviani for technical assistance with the early stages of the project.

This work was financially supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 HL075329 (to F. v. d. A.) and R01 GM067640 (to A. B.). The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research and by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program and the NIGMS, National Institutes of Health. The projects described were partially supported by Grant 5 P41 RR001209 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), National Institutes of Health.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 3L6J) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1 and 2, a movie, and additional references.

- sGC

- soluble guanylyl cyclase

- WT

- wild-type

- Ns

- Nostoc sp.

REFERENCES

- 1.Faller M., Matsunaga M., Yin S., Loo J. A., Guo F. (2007) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 23–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krishnamurthy P., Xie T., Schuetz J. D. (2007) Pharmacol. Ther. 114, 345–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilles-Gonzalez M. A., Gonzalez G. (2005) J. Inorg. Biochem. 99, 1–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evgenov O. V., Pacher P., Schmidt P. M., Haskó G., Schmidt H. H., Stasch J. P. (2006) Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 5, 755–768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bryan N. S., Bian K., Murad F. (2009) Front Biosci. 14, 1–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murad F. (2006) N. Engl. J. Med. 355, 2003–2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stasch J. P., Schmidt P., Alonso-Alija C., Apeler H., Dembowsky K., Haerter M., Heil M., Minuth T., Perzborn E., Pleiss U., Schramm M., Schroeder W., Schröder H., Stahl E., Steinke W., Wunder F. (2002) Br. J. Pharmacol. 136, 773–783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meurer S., Pioch S., Pabst T., Opitz N., Schmidt P. M., Beckhaus T., Wagner K., Matt S., Gegenbauer K., Geschka S., Karas M., Stasch J. P., Schmidt H. H., Muller-Esterl W. (2009) Circ. Res. 105, 33–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidt H. H., Schmidt P. M., Stasch J. P. (2009) Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 191, 309–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boerrigter G., Lapp H., Burnett J. C. (2009) Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 191, 485–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Behrends S. (2003) Curr. Med. Chem. 10, 291–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt P. M., Schramm M., Schröder H., Wunder F., Stasch J. P. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 3025–3032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma X., Sayed N., Beuve A., van den Akker F. (2007) EMBO J. 26, 578–588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pellicena P., Karow D. S., Boon E. M., Marletta M. A., Kuriyan J. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 12854–12859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erbil W. K., Price M. S., Wemmer D. E., Marletta M. A. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 19753–19760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nioche P., Berka V., Vipond J., Minton N., Tsai A. L., Raman C. S. (2004) Science 306, 1550–1553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yeates T. O. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 276, 344–358 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winn M. D., Murshudov G. N., Papiz M. Z. (2003) Methods Enzymol. 374, 300–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Aalten D. M., Bywater R., Findlay J. B., Hendlich M., Hooft R. W., Vriend G. (1996) J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 10, 255–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laskowski R. A., MacArthur M. W., Moss D. S., Thornton J. M. (2001) J. Appl. Cryst. 26, 283–291 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lamothe M., Chang F. J., Balashova N., Shirokov R., Beuve A. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 3039–3048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt P. M., Rothkegel C., Wunder F., Schröder H., Stasch J. P. (2005) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 513, 67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneider T. R. (2000) Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 56, 714–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stone J. R., Marletta M. A. (1996) Biochemistry 35, 1093–1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winger J. A., Marletta M. A. (2005) Biochemistry 44, 4083–4090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rothkegel C., Schmidt P. M., Stoll F., Schröder H., Schmidt H. H., Stasch J. P. (2006) FEBS Lett. 580, 4205–4213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bittner A. R., Sinz C. J., Chang J, Kim R. M., Mirc J. W., Parmee E. R., Tan Q. (August20, 2009) U. S. Patent 20090209556

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.