Abstract

Background

Inhibin is a tumor-suppressor and activin antagonist. Inhibin-deficient mice develop gonadal tumors and a cachexia wasting syndrome due to enhanced activin signaling. Because activins signal through SMAD2 and SMAD3 in vitro and loss of SMAD3 attenuates ovarian tumor development in inhibin-deficient females, we sought to determine the role of SMAD2 in the development of ovarian tumors originating from the granulosa cell lineage.

Methods

Using an inhibin α null mouse model and a conditional knockout strategy, double conditional knockout mice of Smad2 and inhibin alpha were generated in the current study. The survival rate and development of gonadal tumors and the accompanying cachexia wasting syndrome were monitored.

Results

Nearly identical to the controls, the Smad2 and inhibin alpha double knockout mice succumbed to weight loss, aggressive tumor progression, and death. Furthermore, elevated activin levels and activin-induced pathologies in the liver and stomach characteristic of inhibin deficiency were also observed in these mice. Our results indicate that SMAD2 ablation does not protect inhibin-deficient females from the development of ovarian tumors or the cachexia wasting syndrome.

Conclusions

SMAD2 is not required for mediating tumorigenic signals of activin in ovarian tumor development caused by loss of inhibin.

Background

The transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) superfamily ligands including activins and inhibins play integral roles in a wide variety of developmental processes [1-3]. Inhibins are α and β subunit heterodimers (inhibin A: α, βA; inhibin B: α, βB) that oppose activin signaling by antagonizing activin receptors (ACVRs), whereas activins are homodimers (activin A, βA: βA; activin B, βB: βB) or heterodimers (activin AB, βA: βB) of the β subunits [4-6]. Activin signal transduction is initiated when the ligand binds to its type 2 serine/threonine kinase receptor which in turn phosphorylates the type 1 receptor [7-11]. The type 1 receptor then phosphorylates and activates receptor-regulated SMADs (R-SMADs; SMAD2 and SMAD3), which subsequently form complexes with the common SMAD, SMAD4. The R-SMADs/SMAD4 can translocate into the nucleus to regulate gene expression via recruitment of specific transcription factors, activators, and repressors [12-15].

Activins and inhibins are expressed in ovarian granulosa cells and were first described for their roles in FSH regulation [16,17]. However, subsequent studies demonstrated the involvement of these ligands in multiple developmental and pathological events including carcinogenesis [18-20]. Inhibin is a tumor suppressor [21], as inhibin α (Inha) null mice develop gonadal sex cord-stromal tumors originating from the granulosa/Sertoli cell lineages [21], presumably due to the loss of activin antagonism. The tumors secrete an excessive amount of activins that signal through activin receptor type 2 (ACVR2) in the stomach and liver, leading to a cachexia wasting syndrome and pathological changes in these organs (depletion of parietal cells in the glandular stomach and hepatocellular death in the liver) [22,23]. Lethality in Inha null mice is primarily caused by the cachexia wasting syndrome characterized by weight loss, lethargy, and anemia [24]. Although the mechanisms of tumorigenesis in Inha null mice are not fully understood, activin, FSH, and estradiol may play pivotal roles in the development of gonadal tumors [25-28]. As absence of an α subunit precludes α:β dimer assembly, activin is highly elevated in Inha null mice due to the ability of the β subunits to only form β:β activin dimers [24]. While activin-deficient mice die after birth due to craniofacial defects [9], accumulating evidence suggest that activins play important roles in gonadal tumor development in inhibin-deficient mice. Expression of the activin βA subunit is elevated in the gonads of inhibin-deficient mice [29]. Moreover, tumorigenesis is attenuated in inhibin-deficient mice that transgenically express follistatin, an activin antagonist [30,31]. More recently, we demonstrated that administration of a chimeric ACVR2 ectodomain (ActRII-mFc), a known activin antagonist, delayed gonadal tumorigenesis in inhibin-deficient mice [32].

To dissect the activin downstream signaling components during ovarian tumorigenesis, we previously generated Inha/Smad3 double knockout mice in which females are substantially, but not completely, protected from the development of ovarian tumors and the accompanying cachexia syndrome [28]. Since SMAD2 and SMAD3 are activin signal-transducers in vitro and the gonadal somatic cells (granulosa cells and Sertoli cells) from which inhibin-deficient tumors are derived express both SMADs, we hypothesized that SMAD2 may partially compensate for the loss of SMAD3 in mediating ovarian activin signals in the Inha/Smad3 double knockout females. To circumvent the embryonic lethality of Smad2 ubiquitous knockout [33-35], we conditionally deleted Smad2 in ovarian granulosa cells null for Inha to determine the role of SMAD2 in gonadal tumor development.

Methods

Generation of Inha/Smad2 conditional knockout mice

Mice used in this study were maintained on a mixed C57BL/6/129S6/SvEv background and manipulated according to the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Generation of the Inha null mice and the Smad2 null allele was described previously [21,36]. The Smad2 conditional allele was constructed by flanking exons 9 and 10 with two loxP sites using the Cre-LoxP system as previously documented [37,38]. The Amhr2cre/+ mice were produced via insertion of a Cre-Neo cassette into the fifth exon of the anti-Mullerian hormone receptor type 2 (Amhr2) locus [39]. Generation of the Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2cre/+ mice (experimental group) and Smad2flox/-; Inha-/- mice (control group) is depicted in Figure 1.

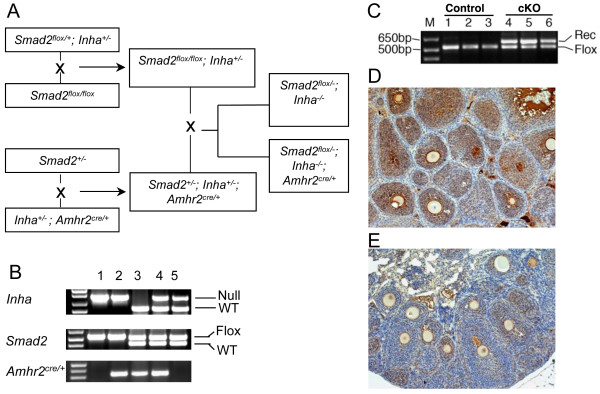

Figure 1.

Generation of Inha/Smad2 cKO mice. (A) Smad2flox/+; Inha+/- mice were mated with Smad2flox/flox mice to produce Smad2flox/flox; Inha+/- mice, and Smad2+/- mice were mated with Inha+/-; Amhr2cre/+ mice to generate Smad2+/-; Inha+/-; Amhr2cre/+ mice. These mice were then crossed to produce Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2cre/+ mice (experimental group) and Smad2flox/-; Inha-/- mice (control group). The generation of the Inha null, Smad2 null and Smad2 floxed alleles is described in the Materials and Methods. (B) Genotyping of mice using PCR analysis. Representative PCR images are shown with corresponding genotypes listed below: 1. Inhα-/-; Smad2flox/-; Amhr2+/+ ; 2. Inhα-/-; Smad2flox/-; Amhr2cre/+ ; 3. Inhα+/+; Smad2flox/+; Amhr2cre/+ ; 4. Inhα+/-; Smad2flox/+; Amhr2cre/+; 5. Inhα+/-; Smad2flox/+; Amhr2+/+. (C) Recombination of Smad2 floxed allele in Inhα-/-; Smad2flox/-; Amhr2cre/+ tumors. Note that the recombined (Rec) allele of Smad2 can be detected only in the tumor tissues of the Inha/Smad2 cKO mice but not in the controls where the Cre recombinase is not expressed. (D and E) Immunohistochemical analysis of SMAD2 protein expression in Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2+/+ (D) and Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2Cre/+(E) mice. Both panels are representative images. Note the dramatic reduction of SMAD2 protein expression in the conditional knockout mice vs. controls (100 × magnification).

Genotyping analysis

Genotyping of the mice was performed by PCR using genomic tail DNA. Table 1 lists the primer sequences utilized in the PCR assays. The annealing temperatures for Inha, Amhr2cre/+, and Smad2 were 61°C, 62°C, and 60°C, respectively. The resultant PCR products were separated and visualized on 1% agarose gels.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for genotyping PCR

| Gene | Primer sequence (5'-3') | |

|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | |

| Inha WT | cct ggg tgg cgc agg ata tgg | ggt ctc ctg cgg ctt tgc gc |

| Inha null | cct ggg tgg cgc agg ata tgg | gga tat gcc ctt gac tat aat g |

| Amhr2cre | cgc att gtc tga gta ggt gt | gaa acg cag ctc ggc cag c |

| Smad2 flox | tac ttg ggg caa tct ttt cg | gtc act ccc tga acc tga ag |

| Smad2 null | gct gag tgc cta agt gat agt gca | tct tct ttt tcc ccg ctg g |

| Smad2 Rec | gag ctg cgc aga cct tgt tac | gtc act ccc tga acc tga ag |

Rec, recombined floxed allele

Measurement of body weight and generation of survival curve

Body weights of animals were measured and recorded weekly from ages 4-26 weeks, and the mice were closely monitored for the development of the cachexia wasting syndrome (i.e., weight loss, kyphoscoliosis, and lethargy) [24]. Mice were sacrificed when their body weights fell below 15 grams or when other severe cachexia symptoms developed as described elsewhere [24,40]. All mice were sacrificed at the end of 26 weeks for a final analysis. To determine the potential effect of conditional deletion of Smad2 on ovarian tumor development at early stages, the Inha/Smad2 cKO mice were also examined at 4 to 9 weeks of age.

Histological analysis

Mice were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation at the time of sacrifice. A small portion of the tails were cut and stored at -70 °C for subsequent genotype verification. Ovaries, stomachs, and livers were removed from the mice and fixed in 10% (vol/vol) neutral buffered formalin overnight. The fixed samples were washed with 70% ethanol prior to paraffin embedding. Ovaries were sectioned and stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-hematoxylin, whereas livers and stomachs were processed for hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining. All staining procedures were conducted in the Pathology Core Services Facility at Baylor College of Medicine using standard protocols.

Immunohistochemistry

Expression of SMAD2 in Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2cre/+ and Smad2flox/-; Inha-/- mice was determined by immunohistochemistry. Briefly, ovaries from 4-week-old mice were fixed in formalin and serially sectioned (5 μm). Antigen retrieval was performed by boiling the sections in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0). The sections were then blocked using 3% BSA/10% serum in PBS, and incubated with SMAD2 primary antibody (1:100 dilution; Cell Signaling). Subsequent procedures were performed using ABC and DAB kits (Vector Lab). The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and mounted with Permount.

Activin A analysis

Blood samples were collected from anesthetized mice by cardiac puncture upon sacrifice, placed in serum separator tubes (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), and allowed to clot at room temperature. Serum was then isolated from the blood samples by centrifugation and stored at -20°C until assayed. Total serum activin A levels were measured using a specific ELISA [41] according to the manufacturer's instructions (Oxford Bio-Innovations, Oxfordshire, UK) with modifications [42]. The average intraplate coefficient of variation (CV) was 7.4% and the interplate CV was 10.8% (n = 2 plates). The limit of detection was 0.01 ng/ml.

Statistical analyses

Differences among groups (average ovary weight, liver weight, and serum activin A levels) were assessed using one-way ANOVA followed by a Kruskal-Wallis post-hoc test. The survival curve was analyzed using a logrank test. For all analyses, significance was defined at P < 0.05. Data are reported as mean standard error of the mean (SEM).

Results

Generation of Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2cre/+ mice

To understand the roles of SMAD2 in ovarian tumor development in inhibin-deficient mice, we took advantage of a conditional knockout strategy to disrupt the Smad2 gene in mouse ovarian granulosa cells. To overcome the embryonic lethality phenotype resulting from Smad2 ubiquitous deletion, a Smad2 floxed allele was generated by flanking exons 9 and 10 of the Smad2 gene with 2 loxP sites [37]. The Amhr2cre/+ knock-in mouse line validated in our previous studies to delete genes expressed in ovarian granulosa cells [38,43-47] was utilized. Figure 1A depicts the breeding scheme used to generate the control (Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-) and experimental Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2cre/+ (Inha/Smad2 cKO) female mice. Representative genotype analyses are presented in Figure 1B. We previously demonstrated that the Smad2 floxed allele can be recombined and deleted in mouse granulosa cells in Smad2 cKO mice [38]. As a further support that inhibin-deficient tumors originate from granulosa cells, the Smad2 recombined allele was readily detectable in the tumor tissues of Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2cre/+ mice, but not in the controls lacking the Cre-recombinase (Figure 1C). Moreover, immunostaining revealed a dramatic reduction of SMAD2 protein levels in the granulosa cells of Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2cre/+ mice vs. controls (Figure 1D and 1E).

Conditional knockout of Smad2 in inhibin-deficient mice does not alter lethality

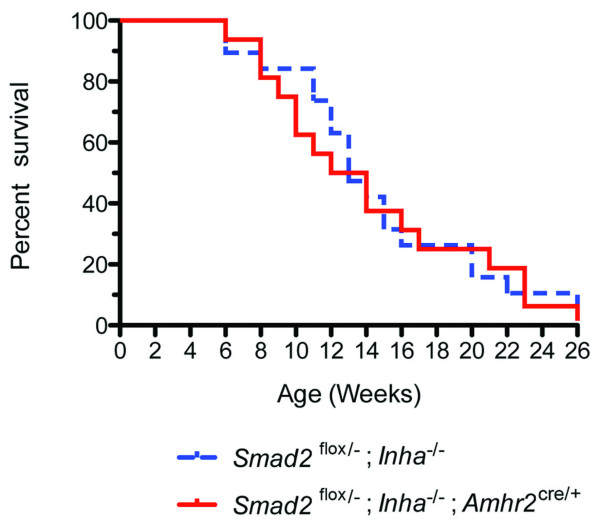

To evaluate the overall effects of Smad2 conditional deletion on the life span of inhibin-deficient mice, we generated and analyzed the survival curves of the Smad2flox/-; Inha-/- controls (n = 19) and the Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2cre/+ (n = 16) experimental mice (Figure 2). The median survival was 13 weeks for both Smad2flox/-; Inha-/- and Smad2flox/-;Inha -/-; Amhr2cre/+ females. Statistical analysis indicated that Smad2 deficiency did not alter the lifespan of Inha null mice (P > 0.05).

Figure 2.

Survival curve of Smad2flox/-; Inha-/- and Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2Cre/+ mice. The survival of the Smad2flox/-; Inha-/- (n = 19; control group) and Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2Cre/+ (n = 16; experimental group) mice were recorded weekly during 4 to 26 weeks. The survival curve was generated and analyzed using a Mantel-Cox test (GraphPad Software, GraphPad Prism version 5.0 b for MacOS X). Statistical significance was not found between the two groups [χ2 (1, N = 35) = 0.051, P = 0.82].

Development of ovarian tumors and cachexia wasting syndrome in Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2cre/+ mice

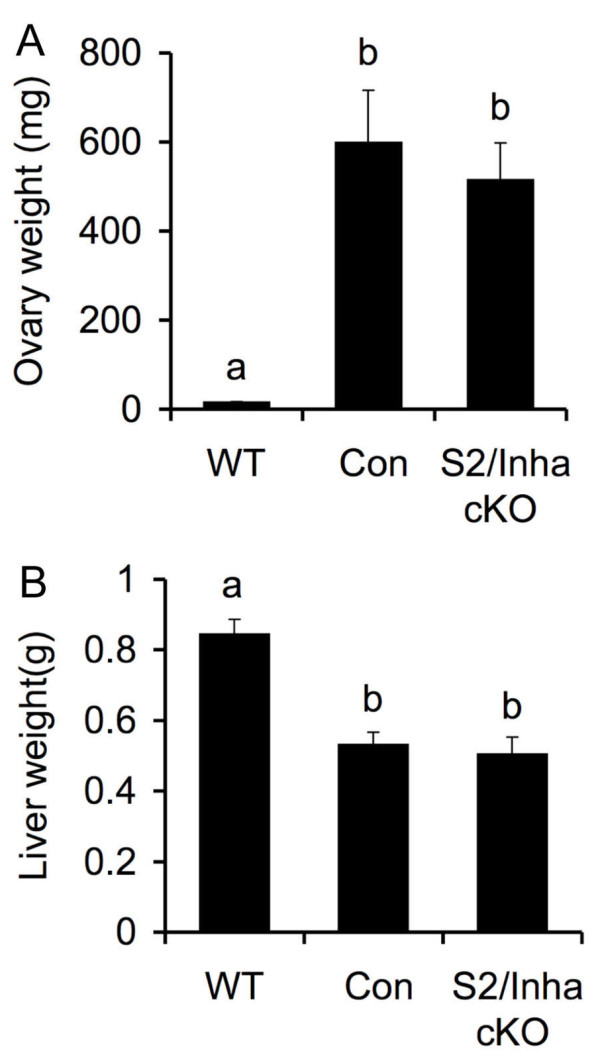

An early sign of tumor development in Inha null mice is severe body weight loss, a prominent feature of the cachexia wasting syndrome. To determine if Smad2 deficiency affects the development and progression of the cachexia syndrome, the body weights of Smad2flox/-; Inha-/- and Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2cre/+ mice were measured weekly. The results showed that Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2cre/+ mice suffered from weight loss similar to that observed in Smad2flox/-; Inha-/- mice (data not shown). Because the cachexia syndrome is also characterized by distinct activin-induced pathological changes in the stomach and liver [22,23], these organs were collected and examined along with the gonads. The ovary and liver weights of the wild type (WT), Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-, and Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2cre/+ mice were measured. Despite the marked changes of the weights of ovary and liver in both Smad2flox/-; Inha -/- (n = 11) and Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2cre/+ mice (n = 5) compared to WT mice (n = 5; P < 0.01), no significant differences in these parameters were found between the Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2cre/+ mice and the Smad2flox/-; Inha-/- controls at a similar stage of tumor progression (P > 0.05; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Ovary and liver weights of WT, Smad2flox/-; Inha-/- control (Con) and Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2cre/+(S2/Inha cKO) experimental mice. Note the dramatic alteration of the weights of the ovary and liver of the Smad2flox/-; Inha-/- (6-26 wk; n = 11) and Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhrcre/+(6-23 wk; n = 5) mice compared to adult WT mice (12 wk; n = 5) due to tumor development. However, no differences in the ovary and liver weights were observed between the control and S2/Inha cKO mice. All data are shown as mean ± SEM, and bars without a common letter are significantly different at P < 0.01.

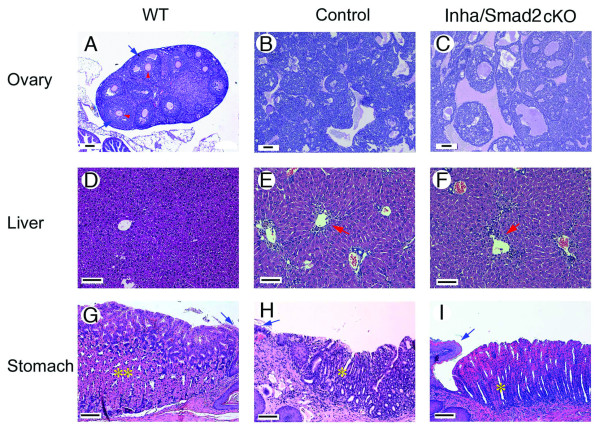

Histological analyses were performed on the ovaries and livers of WT, Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-, and Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2cre/+mice. We first examined the histology of ovaries and livers of the Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2cre/+mice and the Smad2flox/-; Inha-/- mice at the same advanced tumor stage when severe cachexia was observed. In the absence of inhibins, ovarian tumors were grossly hemorrhagic and contained blood-filled cysts irrespective of the status of SMAD2 (Figure 4B and 4C). Microscopic analysis of the livers demonstrated hepatocellular death and lymphocyte infiltration around the central vein (Figure 4E and 4F), another activin-induced pathological effect [22,24]. Furthermore, glandular stomachs of both the control and experimental groups were characterized by depletion of eosinophilic parietal cells and glandular atrophy (Figure 4H and 4I). The observed liver and stomach pathologies are consistent with those of cachectic inhibin-deficient mice [24].

Figure 4.

Histological analyses of ovary, liver, and stomach from WT, control, and experimental female mice. (A) Ovarian histology of an 8 wk old WT mouse. The ovary contains follicles at various developmental stages. Arrows indicate granulosa cells and arrowheads denote oocytes surrounded by a magenta-colored zona pellucida. (B and C) Ovarian histology of a 26 wk old Smad2flox/-; Inha-/- mouse (B) and a 23 wk old Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2cre/+mouse (C), respectively. Tumors from both genotypes were bilateral, large, hemorrhagic, and histologically indistinguishable. (D-F) Histology of livers from a 12 wk old WT mouse (D), a 15 wk old Smad2flox/-; Inha-/- mouse (E), and an 8 wk old Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2cre/+mouse (F). Hepatocellular death around the central vein and lymphocyte infiltration are present in the livers of both the Smad2flox/-; Inha-/- control and Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2cre/+mice (arrows). (G-I) Glandular stomachs from a 12 wk old WT mouse (G), a 26 wk old Smad2flox/-; Inha-/- mouse (H), and a 14 wk old Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2cre/+mouse (I). Note the depletion of parietal cells in both the control and experimental mice (single asterisk) in comparison with the WT mouse (the large and eosinophilic cells; double asterisks). The junction ridge between the squamous epithelium of the forestomach and the glandular stomach is indicated by blue arrows. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Next, to uncover potential effect of Smad2 deletion on ovarian tumor development at an early stage, we examined the tumor status in the Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2cre/+ mice at various time points between 4 and 9 weeks of age, since inhibin-deficient mice can develop tumors as early as 4 weeks. At 4 weeks of age, significant differences were not found in either the cachexia syndrome associated parameters (ovary and liver weights) or tumor histology between the controls (n = 3) and the Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2cre/+ (n = 3) mice (P > 0.05). Similar results were obtained when comparisons were performed at both 6 weeks (n = 3 for each group) and 8-9 weeks of age (n = 3 for each group) (data not shown). Thus, conditional deletion of Smad2 does not delay ovarian tumor development and the progression of the cachexia wasting syndrome in inhibin-deficient mice.

Activin levels

Serum activins are elevated in the inhibin-deficient mice due to the excessive production of the β subunits from gonadal tumors [24]. Thus, activin levels correlate with the tumor status in mice lacking inhibin. The superphysiological level of activins is the primary cause of the cachexia syndrome [22,24]. Since both Smad2flox/-; Inha-/- and Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2cre/+ mice displayed the severe cachexia syndrome, and ovarian tumors in these mice were histologically indistinguishable, we proposed that conditional deletion of Smad2 does not alter the production of activins, an indicator of tumor status in mice lacking inhibins. To test this hypothesis, we measured activin A levels in Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2cre/+ mice and the corresponding control mice at the advanced tumor stage, and found that levels of activin A were similarly elevated in both Smad2flox/-; Inha-/- control (n = 11; 54.1 ± 8.2 ng/ml) and Smad2flox/-; Inha-/-; Amhr2cre/+ experimental females (n = 5; 47.0 ± 6.7 ng/ml) (P > 0.05) in comparison to WT females (n = 7; 0.1 ± 0.0 ng/ml).

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to define the role of SMAD2 in the development of ovarian tumors and activin-induced cancer cachexia syndrome. We demonstrated that conditional deletion of SMAD2 did not prevent the inhibin-deficient females from ovarian tumorigenesis and death; all Inha/Smad2 cKO mice developed sex cord-stromal tumors resembling those observed in Inha null mice. Furthermore, Inha/Smad2 cKO mice suffered from the cancer cachexia syndrome, as evidenced by the severe weight loss and pathological lesions in the stomach and liver (i.e., mucosal atrophy with depletion of parietal cells in the glandular stomach and hepatocellular necrosis around the central vein) [24]. These results indicate that SMAD2 is not required for transducing superphysiological activin signals in the context of gonadal tumor development due to loss of inhibin.

Activins play complex roles in carcinogenesis. In several extragonadal tissues, activin A has been reported to be an anti-tumorigenic factor. For example, activin prevents cell proliferation in breast cancer through SMAD2/3-dependent regulation of cell cycle arrest genes [48]. Similarly, activin A acts as a tumor suppressor in neuroblastoma cells via inhibition of angiogenesis, a key feature of tumorigenesis. Inhibition of endothelial cell proliferation can be achieved by active forms of SMAD2 and SMAD3, suggesting this inhibitory effect is SMAD2/3 dependent [49]. Moreover, activin A has also been reported to prevent the proliferation of tumor cells derived from the prostate and gall bladder [50,51].

Despite the above anti-tumorigenic effects of activins in extragonadal tissues, activins promote tumor development in the gonads [28,52]. The tumorigenic roles of activins have been suggested by the Inha knockout mouse model [21], and the inhibin-deficient mouse model has been exploited to gain a deep understanding of the activin signaling pathway in gonadal tumor development. The Inha/Smad3 double knockout mice generated in our previous study highlights the importance of activins in gonadal tumorigenesis [28]. Since deletion of SMAD3 only delays ovarian tumor development in the Inha null mice [28], we were interested in determining the potential involvement of SMAD2 in mediating the potentiated activin signaling in ovarian tumors lacking inhibins.

SMAD2 and SMAD3 are functionally distinct proteins. Structural differences at the MH1 domain exist between SMAD2 and SMAD3. The extra amino acids (encoded by exon 3) in the SMAD2 MH1 domain prevents its direct binding to DNA, and specific transcription factors are required for SMAD2-DNA binding [53-55]. In contrast, SMAD3 has direct DNA-binding ability [56,57]. Additionally, SMAD3-SMAD4 signaling-dependent genes outnumber SMAD2-SMAD4 dependent genes by more than 4-fold, as identified in Hep3B cells in a recent microarray experiment [58]. Finally, distinct signaling outcomes have been identified in developing mouse Sertoli cells linked with developmentally regulated, differential use of SMAD2 and SMAD3 [59]. Despite these distinctive aspects, SMAD2 and SMAD3 share more than 90% identity in their amino acid sequences [60], and functional redundancy between these two proteins has been demonstrated in the ovary [58,38].

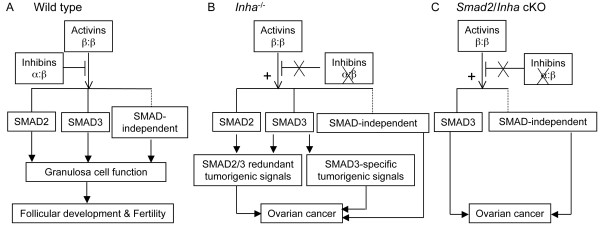

Our current findings, in combination with our previous results, indicate that SMAD2 and SMAD3 may function redundantly to mediate gonadal tumorigenesis in inhibin-deficient mice. In the case of conditional deletion of Smad2, SMAD3 compensates for the deficiency of SMAD2 and transduces essential signals contributing to ovarian tumor development; consequently, tumorigenesis is not altered. On the other hand, loss of SMAD3 in the Inha null mice attenuates but does not prevent ovarian tumor development, suggesting that SMAD2 may partially compensate for the loss of SMAD3. However, our model does not rule out the potential involvement of SMAD-independent signaling in inhibin-deficient ovarian tumor development or the possibility that SMAD2 may not be involved in gonadal tumor development (See Figure 5 for details). It will be interesting to further explore if the contrasting role of activins in gonadal versus extragonadal tissues is linked to the differential impingement of downstream SMAD2 and/or SMAD3 transducers. Furthermore, the potential crosstalk between SMAD-dependent and SMAD-independent signaling pathways in inhibin-deficient tumor development awaits further investigation.

Figure 5.

Hypothetical working model for SMAD2/3 signaling in mediating gonadal tumorigenesis in inhibin-deficient female mice. (A) In the WT ovary, the signaling of activins is finely tuned by inhibins, which is important in the maintenance of normal granulosa cell function, follicular development, and fertility. (B) In the absence of inhibins, activin signaling is potentiated with increased production of activins by the gonads and tumors due to the loss of antagonism by inhibins. Superphysiological levels of activins can signal through both SMAD2 and SMAD3 in the ovary. As demonstrated by the Inha/Smad3 double knockout mouse model [28], ovarian tumor development is attenuated in Inha null mice lacking SMAD3, implying that the function of SMAD3 is not fully compensated by SMAD2. Complementarily, the Inha/Smad2 cKO mouse model generated in the current study suggests that SMAD3 can potentially mediate essential tumorigenic signals of activins in the Inha null mice (C). However, our model does not rule out the potential involvement of SMAD-independent signaling (dotted lines) in inhibin-deficient ovarian tumor development or the possibility that SMAD2 may not be involved in gonadal tumor development.

Conclusions

SMAD2 is not required for mediating tumorigenic signals of activin in ovarian tumor development caused by loss of inhibin.

Abbreviations

Inha: inhibin α; cKO: conditional knockout; TGFβ: transforming growth factor β; ACVR: activin receptor; WT: wild type.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

SR performed the experiments and drafted the manuscript. JEA and RLN helped SR to perform genotyping and immunohistochemistry analyses. MBW generated Smad2 mutant mice. KLL performed activin assays and revised manuscript. MMM and QL designed and supervised this study and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Saneal Rajanahally, Email: rajanaha@bcm.tmc.edu.

Julio E Agno, Email: jagno@bcm.tmc.edu.

Roopa L Nalam, Email: rn140107@bcm.tmc.edu.

Michael B Weinstein, Email: weinstein.41@osu.edu.

Kate L Loveland, Email: kate.loveland@med.monash.edu.au.

Martin M Matzuk, Email: mmatzuk@bcm.edu.

Qinglei Li, Email: qingleil@bcm.tmc.edu.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Richard Behringer for kindly providing the Amhr2cre/+mice. This project was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants CA60651 and HD32067 (to MMM) and by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (545916 and 545917 to KLL). SR was supported by a National Cancer Institute administrative supplement from funds provided by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 providing summer research experiences for students. RLN was supported by the Edward J and Josephine G Hudson Fund.

References

- Attisano L, Wrana JL. Signal transduction by the TGF-beta superfamily. Science. 2002;296:1646–1647. doi: 10.1126/science.1071809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H, Brown CW, Matzuk MM. Genetic analysis of the mammalian transforming growth factor-beta superfamily. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:787–823. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan BL. Bone morphogenetic proteins in development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1996;6:432–438. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(96)80064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling N, Ying SY, Ueno N, Shimasaki S, Esch F, Hotta M, Guillemin R. A homodimer of the beta-subunits of inhibin A stimulates the secretion of pituitary follicle stimulating hormone. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986;138:1129–1137. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(86)80400-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vale W, Rivier J, Vaughan J, McClintock R, Corrigan A, Woo W, Karr D, Spiess J. Purification and characterization of an FSH releasing protein from porcine ovarian follicular fluid. Nature. 1986;321:776–779. doi: 10.1038/321776a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, McKeehan K, Matsuzaki K, McKeehan WL. Inhibin antagonizes inhibition of liver cell growth by activin by a dominant-negative mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6308–6313. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.11.6308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attisano L, Carcamo J, Ventura F, Weis FM, Massague J, Wrana JL. Identification of human activin and TGF beta type I receptors that form heteromeric kinase complexes with type II receptors. Cell. 1993;75:671–680. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90488-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massague J. Receptors for the TGF-beta family. Cell. 1992;69:1067–1070. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90627-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzuk MM, Kumar TR, Vassalli A, Bickenbach JR, Roop DR, Jaenisch R, Bradley A. Functional analysis of activins during mammalian development. Nature. 1995;374:354–356. doi: 10.1038/374354a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massague J. TGF-beta signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:753–791. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y, Schneyer AL. The biology of activin: recent advances in structure, regulation and function. J Endocrinol. 2009;202:1–12. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaivo-oja N, Jeffery LA, Ritvos O, Mottershead DG. Smad signalling in the ovary. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2006;4:21. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-4-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight PG, Glister C. TGF-beta superfamily members and ovarian follicle development. Reproduction. 2006;132:191–206. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.01074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehra A, Wrana JL. TGF-beta and the Smad signal transduction pathway. Biochem Cell Biol. 2002;80:605–622. doi: 10.1139/o02-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas A, Souchelnytskyi S, Heldin CH. Smad regulation in TGF-beta signal transduction. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:4359–4369. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.24.4359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying SY. Inhibins, activins, and follistatins: gonadal proteins modulating the secretion of follicle-stimulating hormone. Endocr Rev. 1988;9:267–293. doi: 10.1210/edrv-9-2-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong FH. Inhibin. Physiol Rev. 1988;68:555–607. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1988.68.2.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora DS, Cooke IE, Ganesan TS, Ramsdale J, Manek S, Charnock FM, Groome NP, Wells M. Immunohistochemical expression of inhibin/activin subunits in epithelial and granulosa cell tumours of the ovary. J Pathol. 1997;181:413–418. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199704)181:4<413::AID-PATH789>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Simone N, Crowley WF Jr, Wang QF, Sluss PM, Schneyer AL. Characterization of inhibin/activin subunit, follistatin, and activin type II receptors in human ovarian cancer cell lines: a potential role in autocrine growth regulation. Endocrinology. 1996;137:486–494. doi: 10.1210/en.137.2.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steller MD, Shaw TJ, Vanderhyden BC, Ethier JF. Inhibin resistance is associated with aggressive tumorigenicity of ovarian cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2005;3:50–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzuk MM, Finegold MJ, Su JG, Hsueh AJ, Bradley A. Alpha-inhibin is a tumour-suppressor gene with gonadal specificity in mice. Nature. 1992;360:313–319. doi: 10.1038/360313a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coerver KA, Woodruff TK, Finegold MJ, Mather J, Bradley A, Matzuk MM. Activin signaling through activin receptor type II causes the cachexia-like symptoms in inhibin-deficient mice. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:534–543. doi: 10.1210/me.10.5.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Karam SM, Coerver KA, Matzuk MM, Gordon JI. Stimulation of activin receptor II signaling pathways inhibits differentiation of multiple gastric epithelial lineages. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:181–192. doi: 10.1210/me.12.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzuk MM, Finegold MJ, Mather JP, Krummen L, Lu H, Bradley A. Development of cancer cachexia-like syndrome and adrenal tumors in inhibin-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8817–8821. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns KH, Agno JE, Chen L, Haupt B, Ogbonna SC, Korach KS, Matzuk MM. Sexually dimorphic roles of steroid hormone receptor signaling in gonadal tumorigenesis. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:2039–2052. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzuk MM, Kumar TR, Shou W, Coerver KA, Lau AL, Behringer RR, Finegold MJ. Transgenic models to study the roles of inhibins and activins in reproduction, oncogenesis, and development. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1996;51:123–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shikone T, Matzuk MM, Perlas E, Finegold MJ, Lewis KA, Vale W, Bradley A, Hsueh AJ. Characterization of gonadal sex cord-stromal tumor cell lines from inhibin-alpha and p53-deficient mice: the role of activin as an autocrine growth factor. Mol Endocrinol. 1994;8:983–995. doi: 10.1210/me.8.8.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Graff JM, O'Connor AE, Loveland KL, Matzuk MM. SMAD3 regulates gonadal tumorigenesis. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:2472–2486. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trudeau VL, Matzuk MM, Hache RJ, Renaud LP. Overexpression of activin-beta A subunit mRNA is associated with decreased activin type II receptor mRNA levels in the testes of alpha-inhibin deficient mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;203:105–112. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipriano SC, Chen L, Kumar TR, Matzuk MM. Follistatin is a modulator of gonadal tumor progression and the activin-induced wasting syndrome in inhibin-deficient mice. Endocrinology. 2000;141:2319–2327. doi: 10.1210/en.141.7.2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Takio K, Eto Y, Shibai H, Titani K, Sugino H. Activin-binding protein from rat ovary is follistatin. Science. 1990;247:836–838. doi: 10.1126/science.2106159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Kumar R, Underwood K, O'Connor AE, Loveland KL, Seehra JS, Matzuk MM. Prevention of cachexia-like syndrome development and reduction of tumor progression in inhibin-deficient mice following administration of a chimeric activin receptor type II-murine Fc protein. Mol Hum Reprod. 2007;13:675–683. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gam055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura M, Li E. Smad2 role in mesoderm formation, left-right patterning and craniofacial development. Nature. 1998;393:786–790. doi: 10.1038/31693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyer J, Escalante-Alcalde D, Lia M, Boettinger E, Edelmann W, Stewart CL, Kucherlapati R. Postgastrulation Smad2-deficient embryos show defects in embryo turning and anterior morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12595–12600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein M, Yang X, Li C, Xu X, Gotay J, Deng CX. Failure of egg cylinder elongation and mesoderm induction in mouse embryos lacking the tumor suppressor Smad2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9378–9383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Festing M, Thompson JC, Hester M, Rankin S, El-Hodiri HM, Zorn AM, Weinstein M. Smad2 and Smad3 coordinately regulate craniofacial and endodermal development. Dev Biol. 2004;270:411–426. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Festing MH, Hester M, Thompson JC, Weinstein M. Generation of novel conditional and hypomorphic alleles of the Smad2 gene. Genesis. 2004;40:118–123. doi: 10.1002/gene.20072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Pangas SA, Jorgez CJ, Graff JM, Weinstein M, Matzuk MM. Redundant roles of SMAD2 and SMAD3 in ovarian granulosa cells in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:7001–7011. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00732-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamin SP, Arango NA, Mishina Y, Hanks MC, Behringer RR. Requirement of Bmpr1a for Mullerian duct regression during male sexual development. Nat Genet. 2002;32:408–410. doi: 10.1038/ng1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar TR, Wang Y, Matzuk MM. Gonadotropins are essential modifier factors for gonadal tumor development in inhibin-deficient mice. Endocrinology. 1996;137:4210–4216. doi: 10.1210/en.137.10.4210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight PG, Muttukrishna S, Groome NP. Development and application of a two-site enzyme immunoassay for the determination of 'total' activin-A concentrations in serum and follicular fluid. J Endocrinol. 1996;148:267–279. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1480267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor AE, McFarlane JR, Hayward S, Yohkaichiya T, Groome NP, de Kretser DM. Serum activin A and follistatin concentrations during human pregnancy: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:827–832. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.3.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgez CJ, Klysik M, Jamin SP, Behringer RR, Matzuk MM. Granulosa cell-specific inactivation of follistatin causes female fertility defects. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:953–967. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pangas SA, Jorgez CJ, Tran M, Agno J, Li X, Brown CW, Kumar TR, Matzuk MM. Intraovarian activins are required for female fertility. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:2458–2471. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreu-Vieyra C, Chen R, Matzuk MM. Effects of granulosa cell-specific deletion of Rb in Inha-{alpha} null female mice. Endocrinology. 2007;148:3837–3849. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreu-Vieyra C, Chen R, Matzuk MM. Conditional deletion of the retinoblastoma (Rb) gene in ovarian granulosa cells leads to premature ovarian failure. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:2141–2161. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pangas SA, Li X, Umans L, Zwijsen A, Huylebroeck D, Gutierrez C, Wang D, Martin JF, Jamin SP, Behringer RR, Robertson EJ, Matzuk MM. Conditional deletion of Smad1 and Smad5 in somatic cells of male and female gonads leads to metastatic tumor development in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:248–257. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01404-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdette JE, Jeruss JS, Kurley SJ, Lee EJ, Woodruff TK. Activin A mediates growth inhibition and cell cycle arrest through Smads in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7968–7975. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panopoulou E, Murphy C, Rasmussen H, Bagli E, Rofstad EK, Fotsis T. Activin A suppresses neuroblastoma xenograft tumor growth via antimitotic and antiangiogenic mechanisms. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1877–1886. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson SJ, Thomas TZ, Wang H, Gurusinghe CJ, Risbridger GP. Growth inhibitory response to activin A and B by human prostate tumour cell lines, LNCaP and DU145. J Endocrinol. 1997;154:535–545. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1540535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokomuro S, Tsuji H, Lunz JG, Sakamoto T, Ezure T, Murase N, Demetris AJ. Growth control of human biliary epithelial cells by interleukin 6, hepatocyte growth factor, transforming growth factor beta1, and activin A: comparison of a cholangiocarcinoma cell line with primary cultures of non-neoplastic biliary epithelial cells. Hepatology. 2000;32:26–35. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.8535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Looyenga BD, Hammer GD. Genetic removal of Smad3 from inhibin-null mice attenuates tumor progression by uncoupling extracellular mitogenic signals from the cell cycle machinery. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:2440–2457. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Wang YF, Jayaraman L, Yang H, Massague J, Pavletich NP. Crystal structure of a Smad MH1 domain bound to DNA: insights on DNA binding in TGF-beta signaling. Cell. 1998;94:585–594. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81600-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennler S, Huet S, Gauthier JM. A short amino-acid sequence in MH1 domain is responsible for functional differences between Smad2 and Smad3. Oncogene. 1999;18:1643–1648. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massague J, Wotton D. Transcriptional control by the TGF-beta/Smad signaling system. EMBO J. 2000;19:1745–1754. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.8.1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennler S, Itoh S, Vivien D, ten Dijke P, Huet S, Gauthier JM. Direct binding of Smad3 and Smad4 to critical TGF beta-inducible elements in the promoter of human plasminogen activator inhibitor-type 1 gene. Embo J. 1998;17:3091–3100. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zawel L, Dai JL, Buckhaults P, Zhou S, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Kern SE. Human Smad3 and Smad4 are sequence-specific transcription activators. Mol Cell. 1998;1:611–617. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Zhang L, Chen A, Xiang G, Wang Y, Wu J, Mitchelson K, Cheng J, Zhou Y. Identification of the gene transcription and apoptosis mediated by TGF-beta-Smad2/3-Smad4 signaling. J Cell Physiol. 2008;215:422–433. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itman C, Small C, Griswold M, Nagaraja AK, Matzuk MM, Brown CW, Jans DA, Loveland KL. Developmentally regulated SMAD2 and SMAD3 utilization directs activin signaling outcomes. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:1688–1700. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KA, Pietenpol JA, Moses HL. A tale of two proteins: differential roles and regulation of Smad2 and Smad3 in TGF-beta signaling. J Cell Biochem. 2007;101:9–33. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]