Abstract

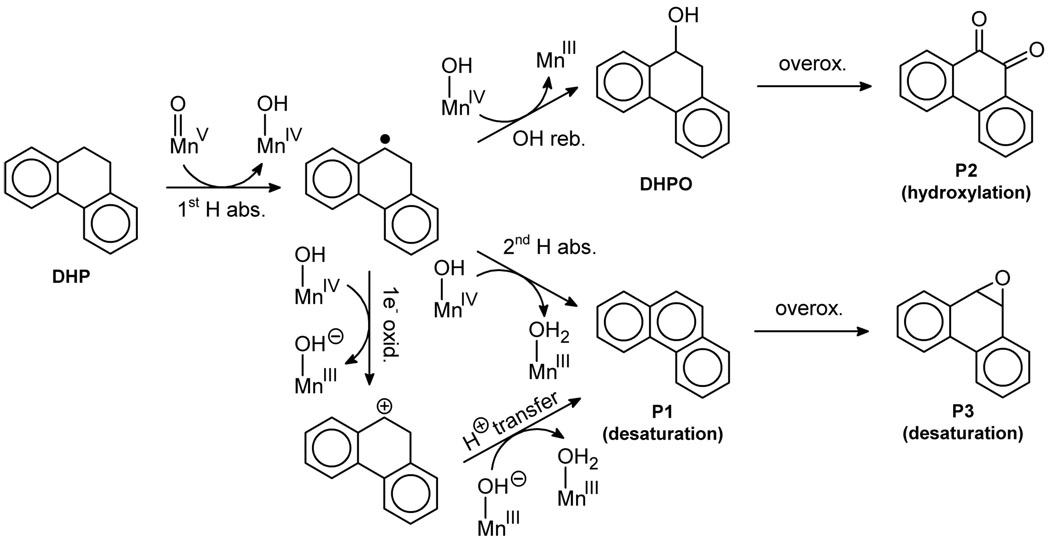

We describe competitive C–H activation chemistry of two types, desaturation and hydroxylation, using synthetic manganese catalysts with several substrates. 9,10-dihydrophenanthrene (DHP) gives the highest desaturation activity, the final products being phenanthrene (P1) and phenanthrene-9,10-oxide (P3), the latter being thought to arise from epoxidation of some of the phenanthrene. The hydroxylase pathway also occurs as suggested by the presence of the dione product, phenanthrene-9,10-dione (P2), thought to arise from further oxidation of hydroxylation intermediate 9-hydroxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene. The experimental work together with the DFT calculations shows that the postulated Mn oxo active species, [Mn(O)(tpp)(Cl)] (tpp = tetraphenyl porphyrin), can promote the oxidation of dihydrophenanthrene by either desaturation or hydroxylation pathways. The calculations show that these two competing reactions have a common initial step – radical H abstraction from one of the DHP sp3 C–H bonds. The resulting Mn hydroxo intermediate is capable of promoting not only OH rebound (hydroxylation) but also a second H abstraction adjacent to the first (desaturation). Like the active MnV=O species, this MnIV-OH species also has radical character on oxygen and can thus give H abstraction. Both steps have very low and therefore very similar energy barriers, leading to a product mixture. Since the radical character of the catalyst is located on the oxygen p orbital perpendicular to the MnIV-OH plane, the orientation of the organic radical with respect to this plane determines which reaction, desaturation or hydroxylation, will occur. Stereoelectronic factors such as the rotational orientation of the OH in the enzyme active site is thus likely to constitute the switch between hydroxylation and desaturation behavior.

Keywords: Desaturase, Manganese, Biomimetics

Introduction

Iron is the workhorse transition metal element of biology, commonly employed in metalloenzymes whenever it is applicable.1 Iron is the typical active site element in oxidoreductases, and, more specifically relevant for this paper, the hydroxylase2 and desaturase3 classes of oxidoreductases. Hydroxylases and desaturases reduce dioxygen so that one oxygen atom is converted to water and the other is transferred to iron to form a highly oxidizing oxo intermediate.

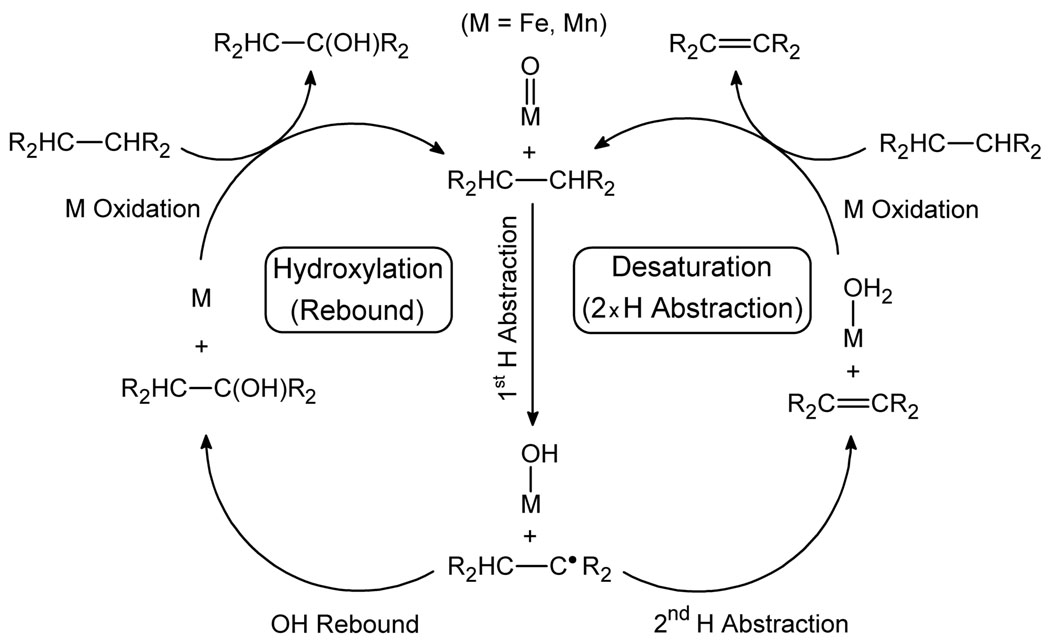

Hydroxylases bring about the conversion of C–H bonds to C-OH functional groups by incorporating the O atom of the iron oxo intermediate via a rebound pathway (Scheme 1).4 In this reaction mechanism, the iron oxo complex first abstracts an H atom from the R2CH-CHR2 substrate to give an Fe(OH) intermediate and a substrate-derived R2CH-C•R2 radical. This radical then abstracts OH from the Fe(OH) intermediate to give the R2CH-C(OH)R2 product in the rebound step.

Scheme 1.

Reaction mechanisms postulated for hydroxylation and desaturation.

Desaturases convert a R2CH-CHR2 alkyl chain to R2C=CR2 by introducing a double bond via a double H abstraction mechanism (Scheme 1).3 In this case, the iron oxo species again abstracts an H atom from R2CH-CHR2 to give an Fe(OH) intermediate and a substrate-derived R2CH-C•R2 radical. The desaturation pathway differs from the hydroxylation pathway in that the Fe(OH) intermediate abstracts a second H atom from the adjacent C–H bond to give R2C=CR2 and Fe(OH2). In both pathways the iron oxo active species is recovered by reoxidation of the metal center.

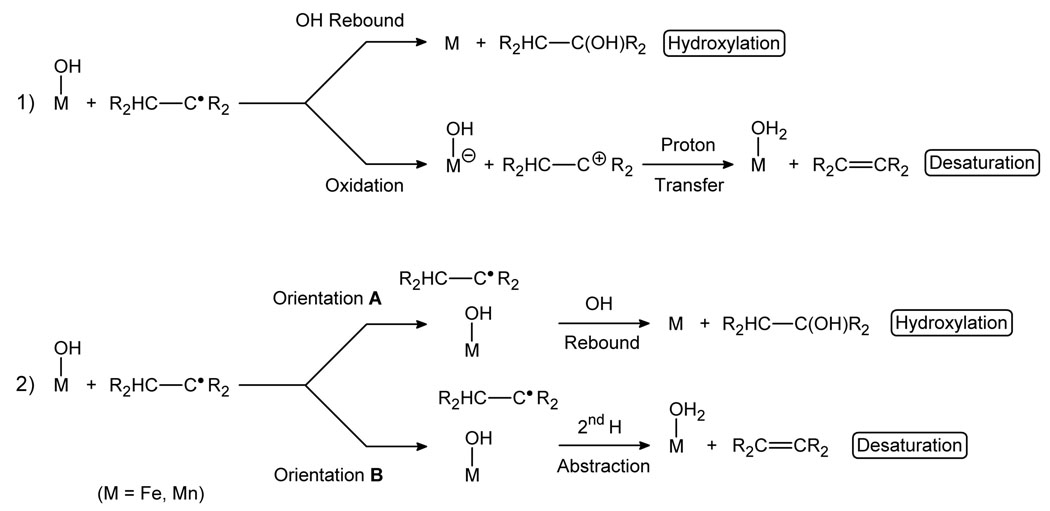

This mechanistic scenario involves hydroxylation and desaturation reactions that are connected by a common initial step.5 There are indeed some examples in which desaturase activity has been reported for hydroxylases6 and the opposite case has been observed as well.7 The switch between the two reaction channels is thus critical, but its exact nature remains elusive. Two different hypotheses have been proposed (Scheme 2).3d In the first one, the reaction outcome depends on the properties of the R2CH-C•R2 radical: if the radical is rapidly oxidized by the metal center, the resulting carbocation yields the desaturation product by deprotonation, otherwise, the radical undergoes OH rebound, yielding the hydroxylation product.8 The participation of a carbocation in the reaction mechanism has been proposed by Shaik in a DFT study.9 In the second hypothesis, the orientation of the radical with respect to the active site plays the key role.10 Depending on which carbon of the R2CH-C•R2 radical approaches the Fe(OH) center, the C• (orientation A) or the CH (orientation B), the major product is either the alcohol or the alkene, respectively.11 In this case, no carbocation is formed in the desaturation pathway and both the first and second H abstractions involve the transfer of an H• radical in a single-step process.

Scheme 2.

Postulated hydroxylation-desaturation switches: 1) formation of a carbocation and 2) orientation of the radical.

Numerous model compounds have been developed to mimic the activity of hydroxylases,12 but very few are known for desaturases.13 In spite of iron being the active site element in these enzymes, manganese compounds are often more reactive in synthetic model catalysts.14 However, no manganese model catalysts for desaturase chemistry are known. As a result of our interest in the water oxidizing center of Photosystem II,15 a manganese enzyme, we have concentrated our efforts on this metal.

Like iron, manganese forms a high-valent oxo intermediate16 which can promote not only hydroxylation, but also desaturation. Manganese complexes are often preferred in biomimetic work because of their higher activity; prior work suggests manganese complexes can mimic the functional properties of iron oxidoreductases. Given that the isolation and characterization of high-valent oxo species is extremely difficult due to their high reactivity, computational chemistry is a powerful tool for their characterization.2e,17 The reactivity of [Mn(O)(por)(X)]+, X = H2O, Cl−, OH−, O2−, in C–H hydroxylation has been theoretically studied by several of us.18 These studies showed that the reaction follows the rebound mechanism.18a The singlet is the ground state of the system but both the triplet and the quintet states may also be accessible in energy, depending on the nature of X.18b,19 The calculations suggest that the singlet, which lacks radical character on oxygen, also referred to as oxyl character, is unreactive. In contrast, the spin states with oxyl character, the triplet and the quintet, promote C–H hydroxylation. Interestingly, the reactive Mn(O) group is not deactivated by H atom abstraction, since the calculations showed that the Mn(OH) product is also a potent H abstractor.18c These studies thus suggest that the Mn(OH) intermediate (Scheme 1) may promote either OH rebound, yielding the hydroxylation product, or a second H abstraction, yielding the desaturation product.

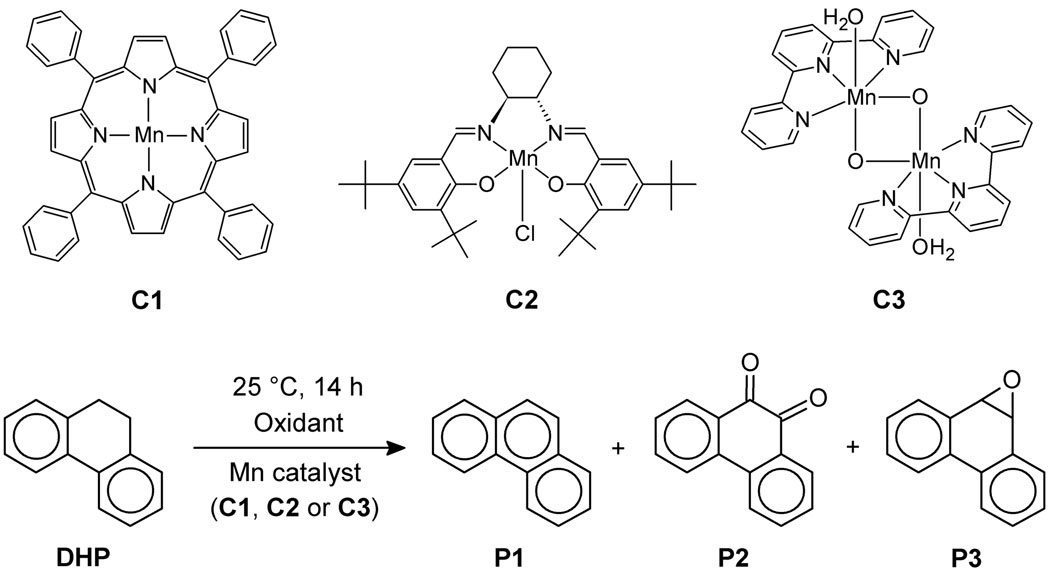

In this paper, we report desaturase activity with three manganese model catalysts (Scheme 3). Our choice of catalysts includes [Mn(tpp)(Cl)] (C1), known to have hydroxylase activity,16 the Jacobsen’s catalyst (C2), for which the only previously recognized reaction was epoxidation,20 and our terpyridine dimanganese catalyst (C3), capable of oxidizing water.21 We now find that all three promote desaturation on suitable substrates, which were chosen to have two adjacent C–H bonds that are particularly weak, either by being benzylic, tertiary or close to an heteroatom. A number of these compounds undergo desaturation, with 9,10-dihydrophenanthrene (DHP) being the best. In this case, not only both activated C–H bonds are benzylic, but also the formation of the C=C bond generates an aromatic system, thus providing extra stability. For such a substrate, analogy with aromatase rather than desaturase is more appropriate, but it is likely that both reactions proceed by analogous mechanisms. The oxidation of DHP yields a mixture of three compounds: the desaturation product, phenanthrene (P1), which is partially overoxidized to phenanthrene-9,10-oxide (P3), and the hydroxylation product, phenanthrene-9,10-dione (P2), given by the overoxidation of the corresponding diol.

Scheme 3.

Catalytic oxidation of DHP.

We also combine experimental studies and DFT calculations to elucidate the reaction mechanism with the main goal to understand why these reactions are competitive. The calculations show that the reaction outcome depends on the orientation of the organic radical relative to the OH group, thus supporting the orientation hydroxylation-desaturation switch (Scheme 2). This is consistent with literature reports that high levels of control over the orientation and position of the substrate in the enzyme active site are required to achieve high selectivity.10 Lack of such control in our model catalysts may explain why literature examples are rare and why our catalysts have a limited substrate scope and yield hydroxylation/desaturation product mixtures.

Experimental results

Oxidation of DHP and other substrates

To develop a simple model system for the desaturase enzyme family, three catalysts, C1, C2 and C3 (Scheme 3) were tested for the oxidation of a series of substrates with a variety of primary oxidants. The 9,10-dihydrophenanthrene (DHP) substrate gave the highest yield and was chosen as the primary substrate for our investigation. The results for the oxidation of DHP under various reaction conditions are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Oxidation of DHP catalyzed by C1, C2 and C3 under various reaction conditions.

| Entry | Catalyst | Atmosphere | Solvent | % Hydrox.a,b | % Desat.a,c | Desat./Hydrox. d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C1e | N2 | CD2Cl2 | 11 | 46 | 4.2 |

| 2 | C1e | Air | CD2Cl2 | 11 | 2 | 0.2 |

| 3 | C1e | N2 | CD3CN | 26 | 67 | 2.6 |

| 4 | C1e | Air | CD3CN | 9 | 31 | 3.4 |

| 5 | C2f | N2 | CD2Cl2 | 3 | 18 | 6.0 |

| 6 | C2f | Air | CD2Cl2 | 0 | 17 | Desat. only |

| 7 | C2f | N2 | CD3CN | 6 | 22 | 3.7 |

| 8 | C2f | Air | CD3CN | 19 | 0 | Hydrox. only |

| 9 | C3g | N2 | CD3CN/D2O | 0 | 20 | Desat. only |

All reactions are run with 1% catalyst vs. substrate for 14 hours.

Estimated from the NMR spectra with a trimethoxybenzene internal standard relative to substrate as limiting reagent.

P2 yield.

P1+P3 yield; epoxide P3 absent for catalysts C2 and C3.

(P1+P3)/P2 product ratio; the P1:P3 ratios are given in the Supporting Information.

2 equiv. of PhIO used as primary oxidant, with no additives.

2 equiv. of Oxone® (KHSO5) used as primary oxidant, and 1 equiv. of N-methylmorpholine-N-oxide (NMO) as additive.

2 equiv. of Oxone® (KHSO5) used as primary oxidant, with no additives.

Three products are observed, phenanthrene (P1), phenantrene-9,10-dione (P2) and phenanthrene-9,10-oxide (P3), as illustrated in Scheme 3. P1 and P2 are the desaturation and hydroxylation products, respectively. In a separate experiment, P1 was epoxidized to P3 using catalyst C1, indicating that P3 is an overoxidized product of P1. Therefore, we regard the “% Desat.” of Table 1 as the sum of the P1 and P3 yields. In all cases but two (entries 2 and 8), the majority of the reaction products result from the desaturation of DHP. Surprisingly, catalyst C1 is the best for desaturation. We expected the dinuclear catalyst C3 to be better since it has been reported to be a more potent oxidation catalyst,22 and it is dinuclear like the desaturase active site.3 The yields of the reaction with the different catalysts are highly dependent on the solvent and the presence of oxygen. For both C1 and C2, the reaction in CD3CN under a nitrogen atmosphere has the highest yield. For all reactions, only the starting material and the expected products were observed.

Changing the reaction conditions not only affected the reaction yields, but also the product ratios. Reactions run in air give lower yields. Under nitrogen, changing the solvent from CD2Cl2 to CD3CN for catalysts C1 and C2 favors hydroxylation over desaturation, as shown by the decrease of the Desat./Hydrox. ratio (Table 1, entries 1 and 3 and 5 and 7). However, the trend is not the same under air because the Desat./Hydrox. ratio increases for C1 but decreases for C2, when CD2Cl2 is replaced by CD3CN as solvent. To determine if the observed change in selectivity is due to changes in the solvent polarity, reactions were run in a series of solvents with different dielectric constants, ε (Table 2). Catalyst C3 is only soluble when water is present, and was not used in this set of experiments.

Table 2.

Influence of the solvent polarity on the oxidation of DHP catalyzed by C1 and C2

| Entry | Catalys t |

Solvent | ε | %Hydrox.a,b | %Desat.a,c | Desat./Hydrox. d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C1e | o-dichlorobenzene- d4 | 2.8 | < 1 | 27 | > 27 |

| 2 | C1e | Dichloromethane-d2 | 9.1 | 11 | 46 | 4.2 |

| 3 | C1e | Nitrobenzene-d5 | 35.7 | 6 | 26 | 4.3 |

| 4 | C1e | Acetonitrile-d3 | 37.5 | 26 | 67 | 2.6 |

| 5 | C1e | Nitromethane-d3 | 39.4 | < 1 | 20 | > 20 |

| 6 | C2f | o-dichlorobenzene- d4 | 2.8 | 0 | 2 | Desat. only |

| 7 | C2f | Dichloromethane-d2 | 9.1 | 3 | 18 | 6.0 |

| 8 | C2f | Nitrobenzene-d5 | 35.7 | 7 | 0 | Hydrox. only |

| 9 | C2f | Acetonitrile-d3 | 37.5 | 0 | 17 | Desat. only |

| 10 | C2f | Nitromethane-d3 | 39.4 | 0 | 19 | Desat. only |

All reactions are run with 1% catalyst for 14 hours under N2 atmosphere.

Estimated from the NMR spectra with a trimethoxybenzene internal standard.

P2.

P1+P3.

(P1+P3)/P2 product ratio.

2 equiv. of PhIO are used as primary oxidant, with no additives.

2 equiv. of Oxone® (KHSO5) are used as primary oxidant, and 1 equiv. of NMO as additive.

As shown in Table 2, with porphyrin C1 as catalyst, both yield and selectivity are significantly affected by the polarity of the solvent. The highest yields (entries 2–4) are associated with the lowest selectivities, whereas the lowest yields (entries 1 and 5) are associated with the highest selectivities. There is no consistent relationship between ε and the yield and Desat./Hydrox. ratio. For instance, the two highest selectivities are observed with both the least, dichlorobenzene, and the most, nitromethane, polar solvents. Interestingly, acetonitrile, which has the strongest ability to coordinate to the metal, leads to the highest yields. This may be associated with the replacement of the axial ligand by acetonitrile, which would yield [Mn(O)(tpp)(CH3CN)]+. This complex is likely to be highly reactive due to a small energy difference between the low spin and high spin states.18b The C2 catalyst is less sensitive to the polarity of the solvent. For the same set of solvents tested for C2, yields are low, being below 20% in all cases, and desaturation dominates over hydroxylation. As for C1, there is no consistent trend relating ε with yield and selectivity.

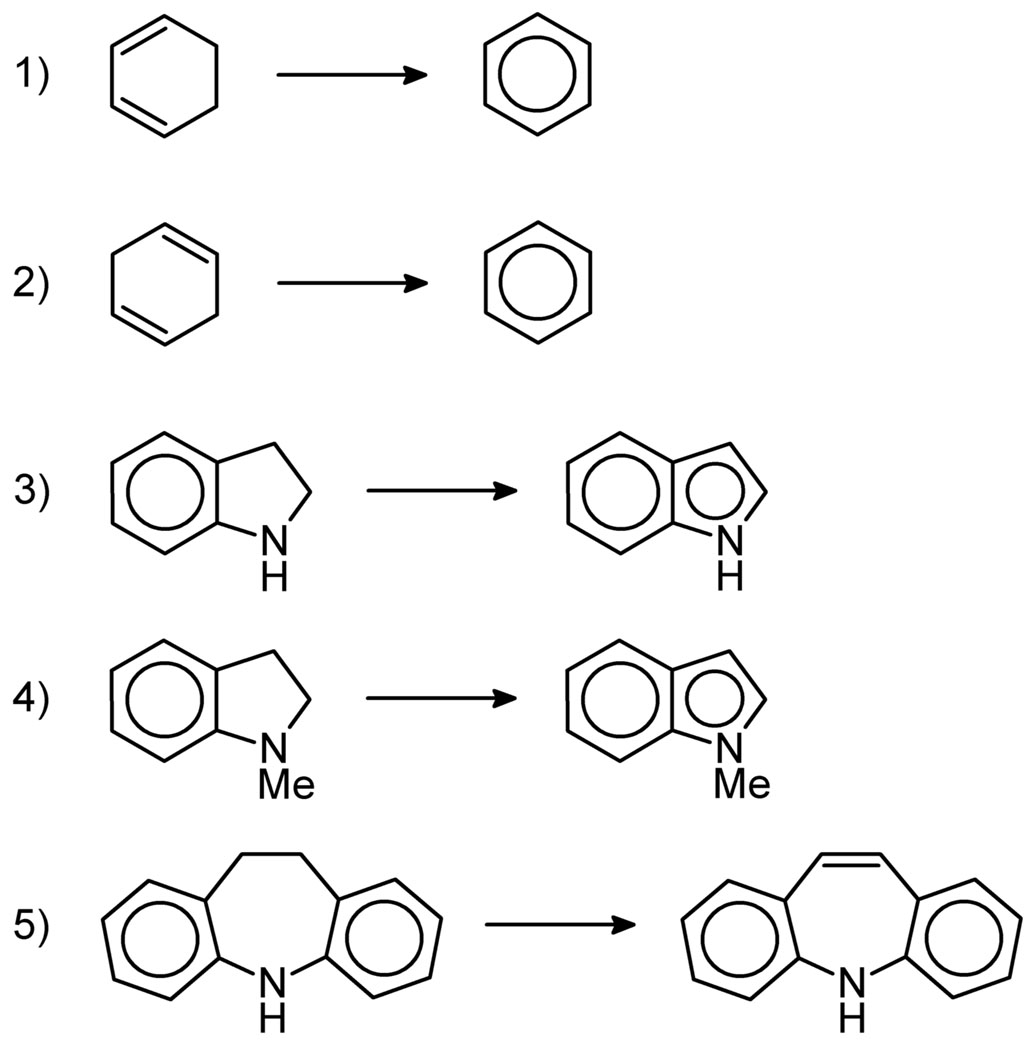

A variety of small molecules containing secondary vinylic and benzylic C–H bonds were screened for desaturase and hydroxylase activity (Scheme 4, Table 3). 1,3-Cyclohexadiene was weakly active for desaturation while 1,4-cyclohexadiene was essentially inactive (entries 1–6). The observed differences between these substrates could be attributed to the adjacent pair of sp3 C–H bonds only being present in 1,3-cyclohexadiene. N-methyl indoline showed the highest levels of desaturase activity for this series of substrates (entries 10–12). Again, this result could be because, like 1,3-cyclohexadiene, it has an adjacent pair of sp3 C–H bonds and gives an aromatic product. In contrast, indoline itself showed essentially no activity, perhaps because the substrate binds to the catalysts and deactivates them (entries 7–9). This does not happen in the case of N-methyl indoline perhaps due to the steric effects introduced by the methyl group. In addition, indoline, unlike acetonitrile, may undergo deprotonation and act as an anionic ligand. Lastly, [a,e]-dibenzohexamethyleneimine showed mixed results (entries 13–15): with C2, a small amount of desaturase product was observed; however, C1 showed no activity at all. C3 gave consumption of the starting material, although the result was a complicated mixture of products which could not be identified. It is noteworthy that for all five of these substrates, hydroxylation products were not observed. This is in stark contrast to the reactions of DHP which gave a mixture of both hydroxylation and desaturation products. All reactions may yield side products, like CO2, due to the oxidation of the solvent. This could perhaps explain the lack of hydroxylation and the overall low yields obtained with some of the substrates.

Scheme 4.

Desaturation reaction with various substrates: 1) 1,3-cyclohexadiene, 2) 1,4-cyclohexadiene, 3) indoline, 4) N-methyl indoline and 5) [a,e]-dibenzohexamethyleneimine.

Table 3.

Oxidation of various substrates catalyzed by C1, C2 and C3 with a variety of oxidants.

| Entry | Catalys t |

Substrate | %Hydrox.a | %Desat.a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C1b,c | 1,3-cyclohexadiene | < 1 | 8 |

| 2 | C2c,d | 1,3-cyclohexadiene | < 1 | 12 |

| 3 | C3e | 1,3-cyclohexadiene | < 1 | 11 |

| 4 | C1f | 1,4-cyclohexadiene | < 1 | < 1 |

| 5 | C2g | 1,4-cyclohexadiene | < 1 | < 1 |

| 6 | C3e | 1,4-cyclohexadiene | < 1 | < 1 |

| 7 | C1f | indoline | < 1 | <1 |

| 8 | C2g | indoline | < 1 | < 1 |

| 9 | C3e | indoline | <1 | < 1 |

| 10 | C1f | N-methyl indoline | < 1 | 20 |

| 11 | C2g | N-methyl indoline | n/dh | n/dh |

| 12 | C3e | N-methyl indoline | < 1 | 16 |

| 13 | C1f | [a,e]-dibenzohexamethyleneimine | < 1 | < 1 |

| 14 | C2g | [a,e]-dibenzohexamethyleneimine | < 1 | 6 |

| 15 | C3e | [a,e]-dibenzohexamethyleneimine | n/dh | n/dh |

Reactions were run in CD3CN to allow direct NMR analysis of products. Yields are reported relative to starting hydrocarbon and were determined by using 1,3,5-trimethylbenzene as internal standard added after the reaction. Control experiments with PhIO alone give no detectable products.

2 equiv. of tetrabutylammonium periodate used as primary oxidant, with no additives.

Periodate was used to oxidize this substrate, as the product of reaction with iodosylbenzene, iodobenzene, interfered with the interpretation of the NMR spectrum of the product.

2 equiv. of tetrabutylammonium periodate used as primary oxidant, with 1 equiv. of NMO as additive.

2 equiv. of Oxone® (KHSO5) used as primary oxidant, with no additives.

2 equiv. of PhIO used as primary oxidant, with no additives.

2 equiv. of Oxone® (KHSO5) used as primary oxidant, with 1 equiv. of NMO as additive.

n/d indicates an unidentifiable product mixture.

The above results show that all three catalysts are broadly similar in their activity. This is especially remarkable for Jacobsen’s salen catalyst, C2, which is best known for the epoxidation of olefins, and not C–H bond oxidation.20

Mechanistic studies

It is generally accepted that high-valent MnIV or MnV oxo porphyrin and salen complexes, when PhIO is used as the primary oxidant, oxidize olefins through a concerted mechanism, and not via a free radical capable of diffusion.16 To test this hypothesis, N-bromosuccinimide (NBS) and CBrCl3 were used as scavengers to test for radicals or a radical chain mechanism in our reaction. Oxidation of DHP in the presence of CBrCl3 or NBS (1/3:100:200:500 of C1/C2/C3:DHP:PhIO:CBrCl3/NBS) under atmospheric oxygen yielded no halogenated products, and no large changes in yield were observed. These results suggest that no radicals escape the solvent cage, or have a lifetime long enough to generate significant amounts of desaturated products or ketones via a freely diffusing radical chain mechanism. Similar evidence is obtained by radical tests with C3 using cis-stilbene, where only the cis-epoxide is observed.23

These data are consistent with a classical rebound pathway for hydroxylation, with fast OH rebound, and with a double H abstraction pathway for desaturation, with fast second H abstraction. In either case, this prevents formation of a freely diffusing radical that can be intercepted by the traps employed. A mechanistic probe was also synthesized to detect the possible participation of a carbocation in the mechanism, but the results were inconclusive (see the Supporting Information).

Computational results

First H abstraction

The oxidation of DHP by C1 (Scheme 3) was studied as model reaction since it yields both the hydroxylation, P2, and desaturation, P1 and P3, products with the highest yields. Our study focuses on the H abstraction and OH rebound steps. The oxidation of C1, which yields the active oxo species, [Mn(O)(tpp)(Cl)], is not studied. The full substrate is included in the calculations, whereas the real tpp ligand of the catalyst is simplified to porphine (por), by replacing the four phenyl rings by hydrogens. We believe that this simplification of the catalyst, which saves a large amount of computational time, does not imply any major change in either the reaction mechanism or in the electronic and steric properties of the system. Only the oxidation of DHP by C1 is considered because the theoretical study focuses on the hydroxylation-desaturation connection, rather than on the influence of the nature of the catalyst and the substrate on the outcome of the reaction.

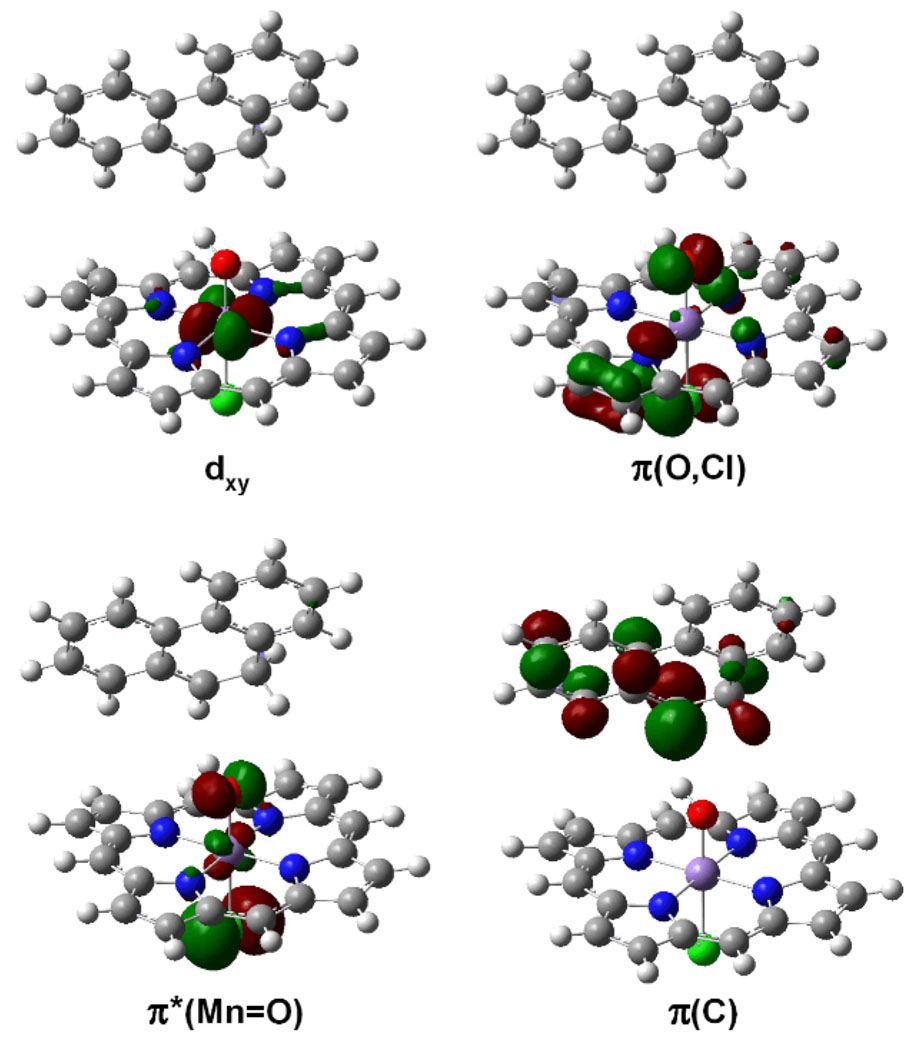

The hydroxylation of DHP by the singlet, S, triplet, T, and quintet, Q, states of [Mn(O)(por)(Cl)], was explored. In a previous study, we showed that Q is less stable than the ground spin state, S, by 11.1 kcal mol−1.18a The main differences between S and Q are associated with the Mn=O distance (1.57 Å in S and 1.70 Å in Q) and the local spin densities on oxygen (0.00 in S and 0.82 in Q), which indicate that Q has radical oxyl character. Q is generated from S by promoting two electrons to the antibonding π*(Mn=O) orbitals, one from the Mn dxy orbital and the other from the porphyrin a2u orbital. The presence of the singly occupied π*(Mn=O) orbitals in Q, accounts for its long Mn=O distance and high oxyl character (vide infra). In T, only one electron is promoted to an antibonding π*(Mn=O) orbital and the oxyl character is therefore significant, but lower than that of Q.

When S was considered as a plausible active species, all attempts to optimize a transition state for H abstraction from DHP were unsuccessful. In contrast, both the triplet and quintet states, T and Q, which have oxyl character, undergo exothermic H abstraction through a low energy barrier (Figure 1). This suggests that in the absence of oxyl character, the Mn=O moiety is not capable of promoting C–H oxidation. A similar result was previously found for the oxidation of toluene by the same reagent.18a

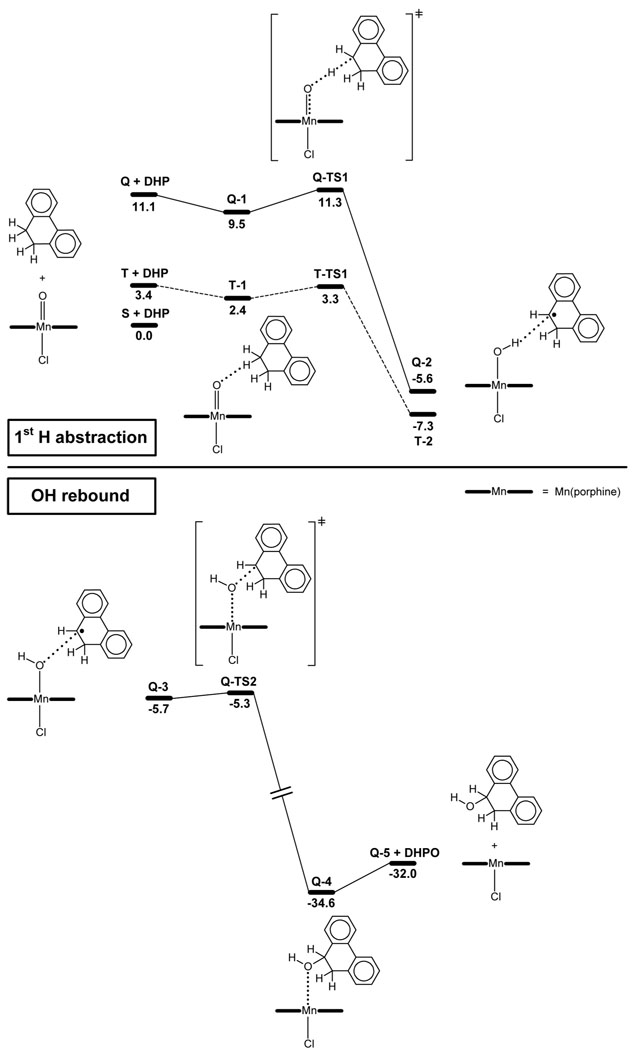

Figure 1.

Potential energy profiles, in kcal mol−1, for the first H abstraction (above) and OH rebound (below) steps. The dashed and solid lines stand for the triplet and quintet pathways, respectively.

The triplet promotes H abstraction from DHP as shown in Figure 1. The transition state, T-TS1, is only 3.3 kcal mol−1 above the ground state reactants, S + DHP, and the reaction is exothermic by 7.3 kcal mol−1. These calculations suggest that the triplet is able to promote the C–H oxidation of the substrate. As it will appear later, the OH rebound (hydroxylation) and second H abstraction (desaturation) steps could not be characterized for this spin state.24 Previous studies on toluene hydroxylation by Mn oxo species have shown that the reaction pathways associated with the triplet and quintet states are very similar.18a,b Therefore, the quintet state is now used to model the reactivity of the high spin oxyl states. We start by calculating the H abstraction step for the quintet even though this spin state is higher in energy than the triplet.

As in the case of the triplet state, the quintet also has radical oxyl character and promotes H abstraction from DHP (Figure 1). The reaction starts by the formation of a pre-reaction complex, Q-1 (Figure 1), in which one of the sp3 C–H bonds of DHP interacts with the oxo group of Q through a H-bond with an H⋯O distance of 2.06 Å. Due to the weakness of this interaction, Q-1 is more stable than Q + DHP by only 1.6 kcal mol−1. The hydrogen interacting with the oxo group undergoes H abstraction leading to intermediate Q-2, which consists of a Mn hydroxo complex interacting with the monohydrophenanthrene radical, MHP•. At the transition state, Q-TS1, the hydrogen involved in the weak interaction with the oxo group is transferred from the C of DHP (d(C⋯H) = 1.20 Å) to the oxygen of Q (d(O⋯H) = 1.48 Å). The H abstraction step, Q-1 → Q-TS1 → Q-2, is exothermic by −15.1 kcal mol−1 and has a low energy barrier of 1.8 kcal mol−1. In agreement with previous studies,18a,b the energies and geometries associated with quintet reaction pathway are similar to those found along the triplet pathway.

For completion to the calculation on the triplet, the reactivity of the associated open-shell singlet has been also explored by using the wave functions and geometries of the triplet stationary points, T-TS1 and T-2, as initial guess. The geometry optimization attempts to locate the analogous of T-TS1 for the open-shell singlet were unsuccessful. Single point calculation of the open shell singlet at the T-TS1 geometry gives an energy of 14.1 kcal mol−1 above the triplet and, more importantly, no imaginary frequency associated with the activation of the C–H bond was observed. Starting now from the product side, a single point calculation using the geometry of T-2 for the open shell singlet MnOH intermediate gives an energy of 31.5 kcal mol−1 above the triplet. Furthermore, the full optimization of the T-2 geometry in the open-shell singlet state converged into a species similar to T-1 and Q-1, which has thus no O–H bond. This stationary point is 2.3 kcal mol−1 below T-1 and 0.1 kcal mol−1 above S + DHP. These calculations suggest that the open-shell singlet state, even if energetically accessible on the reactants side, is unable to promote H abstraction.

All these calculations show that the singlet cannot initiate the reaction by H abstraction and that high spin states with oxyl character are required. The reaction thus necessitates spin crossover whose barrier has been evaluated by localization of the MECP (Minimum Energy Crossing Point; see Computational Details). The singlet to triplet transition involves one MECP, S → T, whereas the singlet to quintet transition involves two MECPs, S → T and T → Q, and is therefore likely to be associated with a low quantum yield. The S → T MECP was characterized, whereas the T → Q MECP could not be located.24 The S → T MECP has a product-like geometry with a Mn=O distance of 1.63 Å, quite close to that of T (1.66 Å). This MECP is only 0.5 kcal mol−1 above T and is 3.9 kcal mol−1 above S. The proximity in energy between the singlet to triplet MECP and the triplet state itself suggests that spin crossover does not involve a significant energy barrier.

Desaturation vs. hydroxylation

After the initial H abstraction, the system may undergo OH rebound thus following the classical oxygen rebound mechanism (Figure 1). The oxygen rebound transition state, Q-TS2, involves the concerted cleavage of the Mn-OH bond (d(Mn⋯O) = 1.90 Å) and formation of a new C-OH bond (d(C⋯OH) = 2.54 Å). The relaxation of Q-TS2 towards reactants and products yields the intermediates Q-3 and Q-4, respectively. In Q-4, the final hydroxylation product, DHPO, is fully formed and coordinated to Mn through oxygen. The OH rebound pathway, Q-3 → Q-TS2 → Q-4, is exothermic by 28.9 kcal mol−1 and has a very low energy barrier of 0.4 kcal mol−1. The final dissociation of Q-4 releases the DHPO product and recovers the catalyst in its quintet state, Q-5. This step is endothermic by only 2.6 kcal mol−1. The overall hydroxylation process is exothermic by 32.0 kcal mol−1. Overoxidation of DHPO, which is not studied, will lead to the formation of the dione product observed experimentally, P2 (Scheme 3).

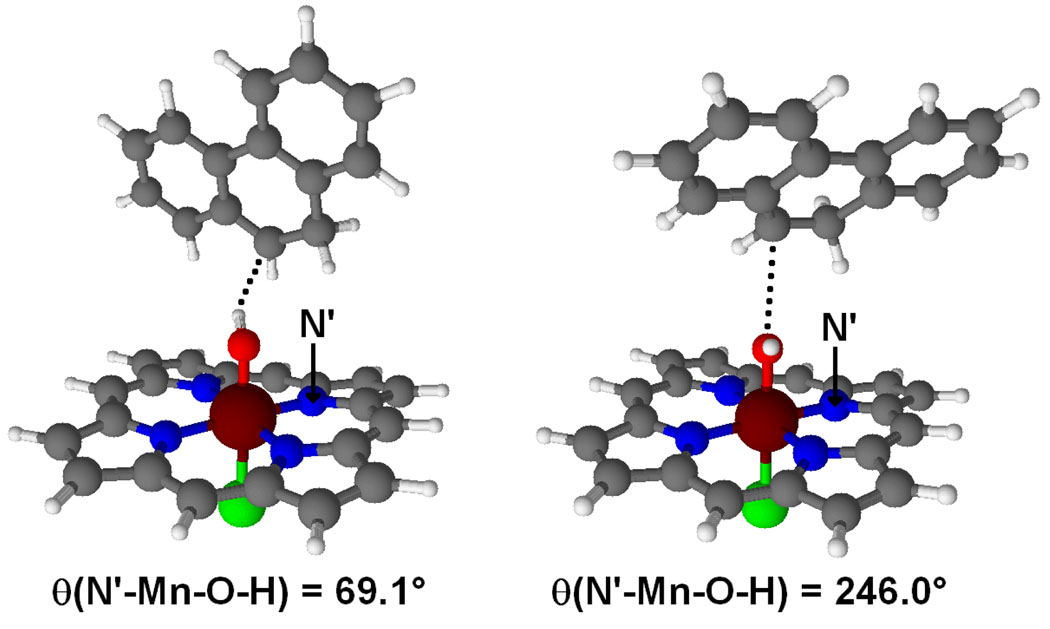

Interestingly, the MnOH intermediate resulting from first H abstraction, Q-2, and the one leading to OH rebound, Q-3, have different orientations of the OH group as expressed by the θ(N’-Mn-O-H) dihedral angle (Figure 2). In Q-2, θ = 69.1°, the OH group points towards the carbon that has undergone H abstraction, whereas in Q-3, θ = 246.0°, points towards the opposite direction.

Figure 2.

Optimized geometries of the Q-2 (left) and Q-3 (right) intermediates.

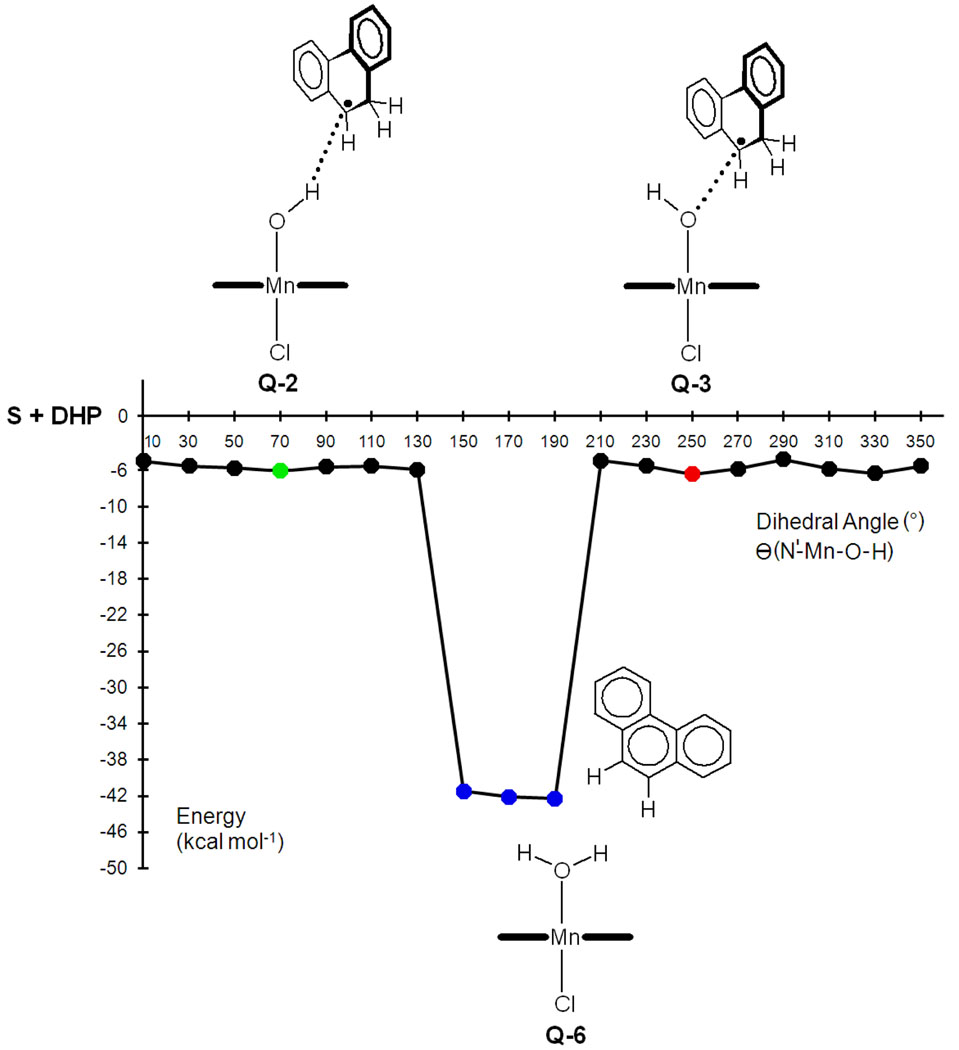

Since Q-2 does not lead to OH rebound, a rotation of the Mn-OH bond is required to reach the reactive Q-3 conformation and force the reaction to proceed.25 This rotation is explored by performing a relaxed energy scan, in which the dihedral angle θ is frozen at different values, whereas all other geometrical parameters are optimized (Figure 3). The scan confirms that the optimal orientations of the OH group correspond to Q-2 and Q-3, which are associated with the θ = 70° and θ = 250° minima, respectively. The potential energy surface is very flat and, therefore, Q-2 and Q-3 are separated by very low energy barriers, < 1 kcal mol−1.

Figure 3.

Rotation of the Mn-OH bond in the presence of the MHP• radical. For each θ orientation of the OH group all other structural parameters are optimized. Q-2, Q-3 and Q-6 are the first H abstraction product, OH rebound reactant and desaturation product, respectively.

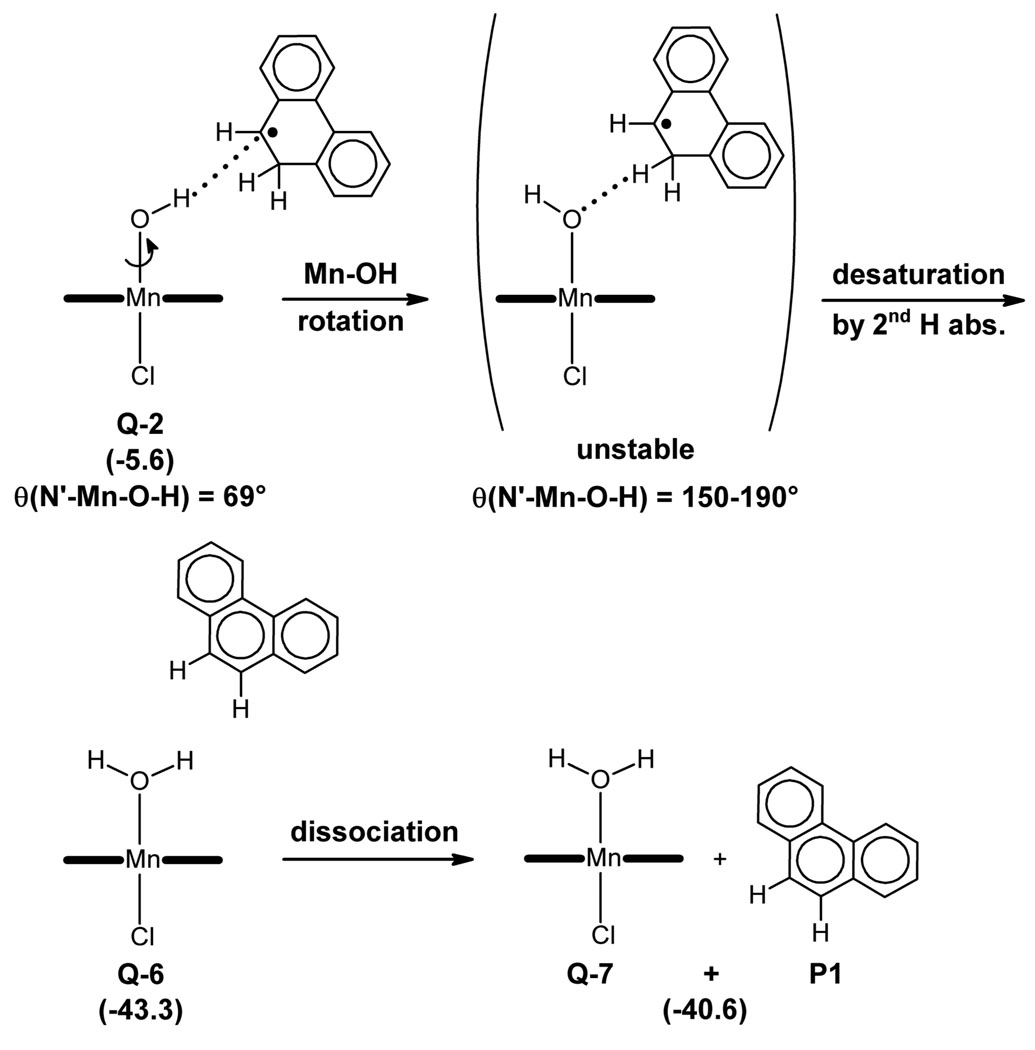

Interestingly, the scan reveals a set of θ values in which the MnOH complex is not stable in the presence of the MHP• radical. For these θ values, θ = 150–190°, the geometry optimization yields a Mn aqua complex weakly bound to the desaturation product, phenanthrene (P1). This clearly identifies a window of OH orientations where the second H abstraction is achieved.

The desaturation reaction is likely to involve two consecutive energy barriers associated with the following processes: 1) Mn-OH bond rotation and 2) C–H bond cleavage in the reactive θ = 150–190° window. We could not locate the transition states of these processes due to the complexity and flatness of the potential energy surface. Nevertheless, the energy maxima found at θ = 110° and 210°, which are less than 1 kcal mol−1 above Q-2, suggest the presence of a very flat and low energy barrier for Mn-OH rotation.26 The C–H cleavage is further investigated by means of a relaxed energy scan in which the d(C-H) distance is kept frozen at different values, whereas all other geometrical parameters are optimized (see Supporting Information). As expected, C–H cleavage prompts O–H bond formation and yields the desaturation product, Q-6. Nevertheless, no energy maximum suggesting the presence of a transition state is observed in this scan. All these results show that second H abstraction involves one or more very low energy barriers, similar to that found for OH rebound.

Further optimization of the θ = 150°, 170° and 190° structures, in which all geometrical parameters, including θ, are optimized, converges into the same complex, Q-6 (Figure 4). This species, which is a van der Waals complex of the aqua complex [Mn(OH2)(por)(Cl)], Q-7, with the desaturation product, P1, dissociates with an energy cost of only 2.7 kcal mol−1. Partial oxidation of P1, which is not studied, will yield the oxide observed experimentally, P3 (Scheme 3).

Figure 4.

Desaturation pathway. The potential energies, in parentheses, are given in kcal mol−1.

The triplet state pathway has been also explored.27 The hydroxylation and desaturation products are optimized by using the geometries and wave functions of the corresponding quintet products, Q-4 and Q-6, as initial guess. These calculations yield the T-4 (hydroxylation) and T-6 (desaturation) triplet products, whose structures are very similar to Q-4 and Q-6, respectively. The energy difference between the triplet and quintet products is less than 3 kcal mol−1. These results suggest that the triplet and quintet pathways are close in terms of structure and energy and, therefore, both states can promote the reaction.

From the thermodynamic point of view, desaturation, ΔE = −40.6 kcal mol−1, is clearly favored over hydroxylation, ΔE = −32.0 kcal mol−1 (Figures 1 and 4). Nevertheless, the high energy barriers associated with the reverse reactions, > 25.0 kcal mol−1, indicate that both desaturation and hydroxylation are not reversible. The selectivity of the overall reaction is, thus, not under thermodynamic control.

Once the first H abstraction is completed, the rotation of the Mn-OH bond of Q-2 generates unstable conformations, which either yield the desaturation product by second H abstraction, or the hydroxylation product by OH rebound. The extremely low and similar energy barriers associated with these reactions have two consequences: 1) once the MHP• radical is generated, it reacts immediately so it does not have time to diffuse away and initiate radical chain reactions and 2) the reaction gives a mixture of the hydroxylation and desaturation products. Both predictions are in good agreement with our experiments (vide supra). Furthermore, both hydroxylation and desaturation start from a common radical intermediate and, therefore, selectivity is not determined by the initial H abstraction step.

The calculations suggest that the catalytic oxidation of DHP by C1 is straightforward because all steps involved in the reaction mechanism are exothermic and have very low energy barriers. Nevertheless, our experiments show that under mild conditions the yield of this reaction is low (Tables 1, 2 and 3). This suggests that the critical step is neither H abstraction nor OH rebound. In line with this, experimental studies by Newcomb showed that the overall rate of the process may be controlled by the generation and stability of the active Mn oxo species.16e A detailed study of kinetic isotope effects (KIE) may clarify this point. However, the determination of KIE in our system is challenging both at the experimental and theoretical levels and it is beyond the scope of this paper. Eyring KIE plots are therefore not provided.

Discussion

The oxidation of DHP starts with H abstraction by the manganese oxo active species derived from C1 (Figure 5). The resulting radical undergoes either OH rebound, yielding an alcohol, or a second H abstraction, yielding phenanthrene (P1). The alcohol is quantitatively overoxidized to the dione P2, whereas P1 is overoxidized to a small extent to the oxide P3 (see the Supporting Information). Therefore, P2 is the hydroxylation product and P1 and P3 are the desaturation products. Our experiments show that the oxidation of DHP catalyzed by C1 leads to mixtures of these three products (Table 1), which demonstrates that the reaction involves both hydroxylation and desaturation pathways, as previously observed with some hydroxylase and desaturase enzymes.6,7 Catalysts C2 and C3 give similar results, except that no epoxide P3 is formed, and the three catalysts can be thus regarded as models for desaturase activity.

Figure 5.

Possible reaction pathways in the catalytic oxidation of DHP.

The mechanistic picture of Figure 5 indicates that desaturation and hydroxylation diverge from a common radical intermediate. Therefore, some sort of switch has to control the final outcome of the reaction. The nature of this switch has been debated.3d One proposal is that the switch consists of the formation of a carbocation8,9,28 which, depending on the nature of the substrate, is yielded by the oxidation of the radical intermediate. This carbocation leads to desaturation by loss of a proton.

Previous reports of the dehydrogenation of saturated carbo- and heterocycles use heterogeneous catalysts that form a carbocation on the substrate directly.29 However, in explaining the mechanism, the prior authors propose a single reaction path with a carbocation intermediate that does not resemble the biological transformation of interest here. Our experimental and theoretical studies do not provide evidence supporting the formation of a carbocation intermediate in the oxidation of DHP. In contrast, the lower yield and altered product ratios of reactions run in the presence of atmospheric oxygen suggest that a radical may be involved in the mechanism (Table 1 Entries 2, 4, 6, 8). However, tests using NBS and CBrCl3 indicate that such a radical is not long-lived, preventing radical trapping. These observations are in good agreement with the calculations, which show that both OH rebound and H abstraction in the radical intermediate involve extremely low energy barriers, < 1 kcal mol−1 (Figures 1 and 3).

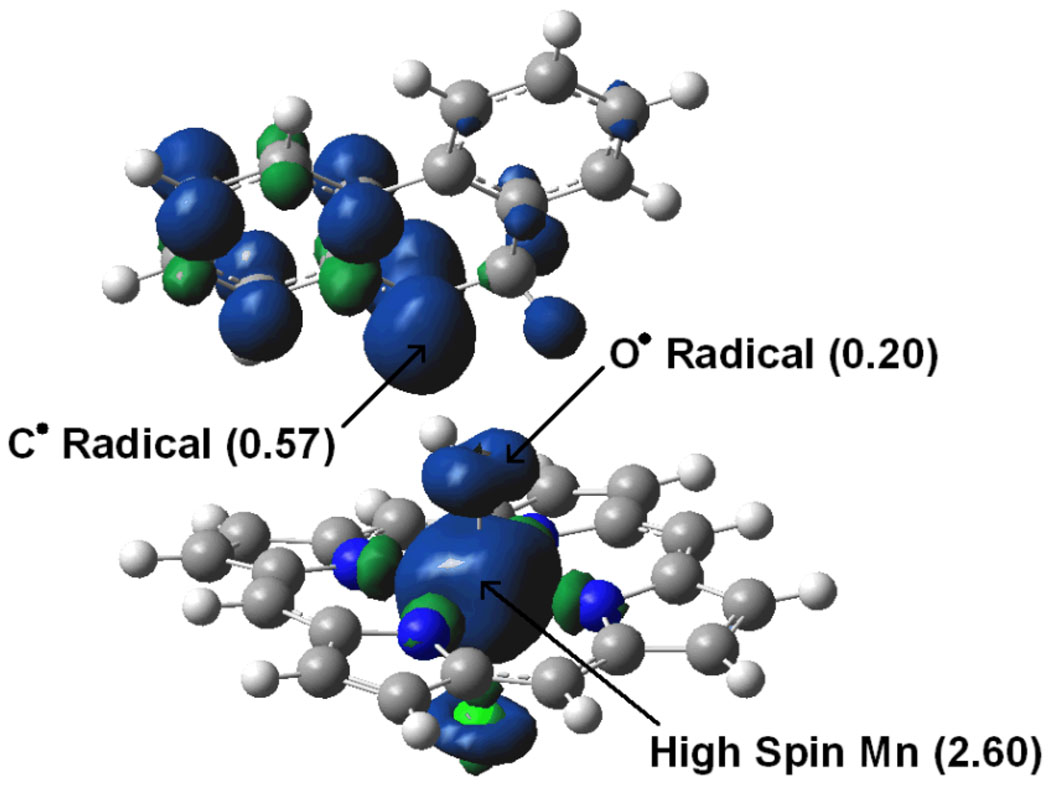

As the experiments, the calculations do not indicate the participation of a carbocation in the mechanism. The initial H abstraction step yields intermediate Q-2, in which the organic fragment generated from DHP interacts with a Mn hydroxo complex (Figure 2). The local spin densities and charges of Q-2 indicate that the organic monohydrophenanthrene fragment, with a total charge of 0.01 and a total spin density of 0.97, is a neutral radical, MHP•. A large part of this spin density, 0.57, is located on the carbon which has undergone H abstraction. These data show that the radical is not spontaneously transformed into a carbocation by reduction of the metal center to Mn(III). The organometallic part of Q-2, [Mn(OH)(por)(Cl)], with a total charge of −0.01, is neutral and has a total spin density of 3.03, mostly located on the metal (2.60). This local spin density suggests that the metal center has been reduced to Mn(IV) in the hydroxo intermediate. All these results point to the radical nature of the initial H abstraction step. In addition, the radical product of this reaction undergoes a second H abstraction induced by the rotation of the Mn-OH bond (Figures 3 and 4), yielding the desaturation product without the participation of a carbocation.

The dissociation of Q-2 may yield the MHP• radical and the hydroxo complex, [Mn(OH)(Cl)(por)]. Single electron transfer between both species would lead to the formation of the monohydrophenanthrene cation, MHP+, and the anionic hydroxo complex, [Mn(OH)(Cl)(por)]− (eq. 1).

| (1) |

The spin states are doublet, quartet, singlet and quintet for MHP•, [Mn(OH)(Cl)(por)], MHP+ and [Mn(OH)(Cl)(por)]−, respectively. The energy change associated with this reaction, ΔGCPCM(1), was computed by considering acetonitrile as solvent with the continuum CPCM method, to account for the presence of charged species. The value of ΔGCPCM(1), 18.1 kcal mol−1, shows that the radical intermediate is clearly favored over the cationic one for the system under study. Nevertheless, both the radical and cationic mechanisms may be relevant and the preference for one or the other is likely to depend strongly on the specific nature of the substrate, catalyst and solvent in each case.

The calculations support the hypothesis in which the orientation of the substrate with respect to the reactive center constitutes the hydroxylation-desaturation switch. The electronic structure of Q-2 was further explored by analyzing its four singly occupied molecular orbitals. The highest energy SOMO, π(C), which lies at the HOMO level, is a non-bonding π orbital located on the aromatic rings of the organic fragment (Figure 6). π(C) accounts for the radical character of the organic fragment and the most relevant contribution to this orbital comes, indeed, from the carbon with the strongest radical character. Deeper in energy, we found two other SOMOs: an anti-bonding π orbital of the Mn=O bond, π*(Mn=O), and the non-bonding dxy Mn orbital. These two orbitals contribute to the local Mn spin density. The fourth SOMO, π(O,Cl), is a non-bonding combination of the oxygen and chloride lone pairs. The π*(Mn=O) and π(O,Cl) orbitals contribute to the significant local spin density on the O atom (0.20). This spin density implies that Q-2 has radical character on oxygen and it is, therefore, capable of promoting not only OH rebound but also the second H abstraction leading to the desaturation product.18c However, not only the presence but also the orientation of the spin density on oxygen are crucial.

Figure 6.

SOMO orbitals of intermediate Q-2. Spin density is plotted in Figure 7.

The shape of the π*(Mn=O) and π(O,Cl) orbitals suggests that the spin density on oxygen is located along an axis perpendicular to the MnOH plane. This is confirmed by the plot of the total spin surface of Q-2 (Figure 7). Right after the first H abstraction, in Q-2, this axis points neither to the radical carbon nor to the vicinal sp3 C–H bonds and, therefore, this species does not react. Nevertheless, the free rotation of the Mn-OH bond yields the Q-3 conformation, in which the spin vector on oxygen points towards the radical C of the organic fragment. This orientation promotes the hydroxylation of the radical by OH rebound. In contrast, when the Mn-OH bond rotates in the opposite sense, the spin vector on oxygen points towards one of the sp3 C–H bonds. This induces a second H abstraction from the organic radical, which yields the desaturation product.

Figure 7.

Spin density of Q-2. The excess of alpha and beta spin densities are represented in blue and green, respectively. Local spin densities are given in parenthesis.

These results show that the Mn hydroxo intermediate will promote either desaturation or hydroxylation, depending on how the organic radical is orientated with respect to the OH group. In our computational model, these reactive orientations are achieved by rotating the Mn-OH bond. In the real system, these orientations may be controlled by more complex mechanisms. For instance, the organic radical can move around the MnOH group. The orientation of the substrate in its initial approach to the catalyst,30 the dynamics of the system31 and the weak interactions between the catalyst, substrate and solvent32 may also have a critical influence on the final outcome of the reaction. Therefore, the accurate prediction of the final desaturation/hydroxylation ratio, which is not the goal of this paper, will require extremely computationally demanding calculations. In addition, there will be no general rules to predict the selectivity of the reaction, which will depend on the nature of each species participating in the reaction.

In summary, the mechanistic picture of the reaction reveals that the relative orientations of both the metal catalyst and the organic radical need to be precisely defined, in order to favor only one of the two possible reactions and obtain high selectivity. In agreement with this scenario, high desaturation/ hydroxylation selectivity ratios are only achieved by enzymes, in which the position of the reactive center is fixed and the orientation of the substrate is precisely set by the protein environment.

Conclusions

We have shown the first model study of desaturase chemistry using synthetic manganese catalysts and several substrates. DHP gives the highest desaturase activity and the presence of the dione product P2 indicates the close relationship between hydroxylation and desaturation. Other reactive substrates for desaturation included N-methyl indoline and 1,3-hexadiene, both of which contain two adjacent sp3 CH bonds and both also give aromatic species on desaturation. The experimental work is supported by the calculations and shows that the postulated Mn oxo active species, [Mn(O)(por)(Cl)], promotes the oxidation of dihydrophenanthrene by either hydroxylation or desaturation. These two competing reactions have a common initial step, which is radical H abstraction from one of the sp3 C–H bonds. The resulting Mn hydroxo intermediate is capable of promoting not only OH rebound (hydroxylation) but also a second H abstraction (desaturation) because, in parallel with the active oxo species, it has radical character on oxygen. Both steps have very low and similar energy barriers, leading to a product mixture. Since the radical character of the catalyst is located on the oxygen p orbital perpendicular to the MnOH plane, the orientation of the organic radical with respect to this plane determines which reaction will occur. Substrate orientation in the enzyme active site is, thus, likely to constitute the switch between hydroxylation and desaturation.

Experimental Section

General

All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, unless otherwise noted. The epoxide standard for P3 was prepared by stirring 1 equivalent of phenanthrene (P1) with 1.5 equivalents of 4-chloroperoxybenzoic acid (m-CPBA) for 3–20 hours, and purified using column chromatography (230–400 mesh silica gel, gradient of 30/70 – 60/40 EtOAc/Hexanes). Solvents were degassed using standard Schlenk techniques. All yields for manganese-catalyzed reactions were measured by NMR using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as an internal standard on a Bruker spectrometer running at 400 or 500 MHz, and GC-MS on a Hewlett-Packard 5971A spectrometer.

The following typical reaction conditions were used for each catalyst, unless otherwise noted in the footnotes to the tables. Representative duplicate experiments were performed in the key cases with consistent results.

Oxidation by catalyst C1

A suspension of substrate (0.10 mmol), and C1 (0.005 mmol) in 1 mL of solvent were degassed with three freeze-pump-thaw cycles. Before thawing in the final cycle, iodosobenzene (0.20 mmol) was added under a flow of nitrogen and the flask was sealed, evacuated, and refilled with nitrogen. Upon warming to room temperature, the reaction was stirred at ambient temperature for the time indicated (12–16 hours), at which point 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene was added as an internal standard. The reaction was then filtered over a pad of celite and the crude mixture was immediately analyzed by 1H NMR.

Oxidation by catalyst C2

A suspension of substrate (0.10 mmol), tetrabutylammonium oxone (0.20 mmol) and N-methylmorpholine-N-oxide (0.11 mmol) in 1 mL of solvent was degassed with three freeze-pump-thaw cycles. After the last cycle, Jacobsen’s catalyst (0.005 mmol) was added under a flow of nitrogen and the flask was sealed. The reaction was stirred at ambient temperature for the time indicated (12–16 hours) at which point 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene was added as an internal standard. The reaction was then filtered over a pad of celite and the crude mixture was immediately analyzed by 1H NMR. Only catalyst C1 showed a modest degree of overoxidation of P1 to P3 (see the Supporting Information).

Oxidation by catalyst C3

A mixture of substrate (0.10 mmol) and tetrabutylammonium oxone (0.20 mmol) in 1 mL of solvent was degassed with three freeze-pump-thaw cycles. After the last cycle, catalyst C3 (0.001 mmol) was added under a flow of nitrogen and the flask was sealed. The reaction was stirred at ambient temperature for the time indicated (12–16 hours) after which time 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene was added as an internal standard, the reaction was filtered over a pad of celite and the crude reaction mixture was immediately analyzed by 1H NMR.

Computational Details

Unrestricted DFT calculations were performed by using the BP86 functional.33 All geometries were fully optimized for each spin state, without any symmetry or geometry constraints. The nature of all stationary points was confirmed by the analytical calculation of their frequencies. The vibrational data were used to relax the geometry of each transition state towards reactants and products, in order to confirm its nature. The geometries were optimized with basis set I (Stuttgart-Bonn scalar relativistic ECP with associated basis set34 for Mn and the 6–31G basis set35 for O, N, C and H). The energies given in the text were computed by single-point calculations with basis set II (basis set I plus polarization functions36 on all atoms), on the stationary points obtained with basis set I. The effect of the solvent, acetonitrile, was modeled by single-point calculations with the CPCM method37 with basis set II. Free energies were obtained from the vibrational calculations with basis set I. The solvent, entropy and zero-point energy corrections did not alter in a great extent the energy profiles. All these corrections are given in the Supporting Information. The molecular orbitals and the spin densities were obtained from NPA38 (Natural Population Analysis) calculations. All calculations were carried out with Gaussian03.39 The optimization of MECP (Minimum Energy Crossing Point) between different spin surfaces was carried out by using the code developed by J. N. Harvey.40

The pure BP86 functional has been successfully used by us in previous studies on C–H oxidation by manganese oxo species.18 The DFT calculations on these catalytic systems should be taken with precaution, since some results may depend on the nature of the functional chosen. Test calculations at the DFT(B3LYP) level have shown that this hybrid functional predicts a different energy ordering of the spin states, in which the quintet is the ground state. In contrast, the BP86 calculations indicate that the ground state is the singlet. This result is in better agreement with several experimental studies on manganese oxo complexes, which suggest that the ground state is a diamagnetic singlet species.16 In a previous study, we have also shown that the electronic structure of the manganese oxo species may depend on the nature of the functional.18c Nevertheless, both the BP86 and B3LYP functional give the same qualitative picture in which, regardless of the stability ordering, all the spin states are close in energy and therefore accessible.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank the NSF (Grant Number 0614403) for financial support. E.L.O.S. thanks the NSERC. D.B. thanks Sanofi-Aventis for a post-doctoral fellowship. O.E., C.R. and D.B. thank the CNRS and the French Ministry of National High Education and Research for funding. We also thank Siddhartha Das for initial observations in this area.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. A table of all substrates that were screened for activity. Details of the mechanistic experiments, including the synthesis of a substrate to probe the proposed mechanistic pathways. The P1:P3 ratios for entries 1–4 of Table 1. Optimized geometries of all stationary points together with their potential, zero-point, entropy and CPCM energies. Relaxed energy scan for C–H cleavage in the second H abtraction step. Reaction pathway for the rotation of the Mn-OH bond in the isolated [Mn(OH)(por)(Cl)] complex. Complete list of authors for reference 39. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Hill HAO, Sadler PJ, Thomson AJ, editors. Metal Sites in Proteins and Models: Iron Centres (Structure and Bonding, Vol. 88) Emeryville: Springer-Verlag Telos; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Ozaki SI, Roach MP, Matsui T, Watanabe Y. Acc. Chem. Res. 2001;34:818–825. doi: 10.1021/ar9502590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Poulos TL, Li HY, Raman CS, Schuller DJ. Adv. Inorg. Chem. 2001;51:243–293. [Google Scholar]; (c) Groves JT. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:3569–3574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0830019100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Matsunaga I, Shir Y. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2004;8:127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Meunier B, de Visser SP, Shaik S. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:3947–3980. doi: 10.1021/cr020443g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Ortiz de Montellano PR. Cytochrome P450: Structure, Mechanism, and Biochemistry. 3rd ed. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2005. [Google Scholar]; (e) Denisov IG, Makris TM, Sligar SG, Schlichting I. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:2253–2278. doi: 10.1021/cr0307143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Solomon EI, Sundaram UM, Machonkin TE. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:2563–2605. doi: 10.1021/cr950046o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Que L, Dong YH. Acc. Chem. Res. 1996;29:190–196. [Google Scholar]; (j) Sazinsky MH, Lippard SJ. Acc. Chem. Res. 2006;39:558–566. doi: 10.1021/ar030204v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Shu LJ, Nesheim JC, Kauffmann K, Munck E, Lipscomb JD, Que L. Science. 1997;275:515–518. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5299.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Bloch K. Acc. Chem. Res. 1969;2:193–202. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fox BG, Lyle KS, Rogge CE. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004;37:421–429. doi: 10.1021/ar030186h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Behrouzian B, Buist PH. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2002;6:577–582. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(02)00365-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Buist PH. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2004;21:249–262. doi: 10.1039/b302094k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Abad JL, Camps F, Fabriàs G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000;39:3279–3281. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20000915)39:18<3279::aid-anie3279>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Abad JL, Camps F, Fabriàs G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:15007–15012. doi: 10.1021/ja0751936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Shanklin J, Guy JE, Mishra G, Lindqvist Y. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:18559–18563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R900009200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Johansson AJ, Blomberg MRA, Siegbahn PEM. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2007;111:12397–12406. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Groves JT, McClusky GA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976;98:859–861. [Google Scholar]; (b) Groves JT. J. Chem. Educ. 1985;62:928–931. [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Buist PH, Marecak DM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:5073–5080. [Google Scholar]; (b) Akhtar M, Wright JN. Nat. Prod. Rep. 1991;8:527–551. doi: 10.1039/np9910800527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Cook GK, Mayer JM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:1855–1868. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Rettie AE, Rettenmeier AW, Howald WN, Baillie TA. Science. 1987;235:890–893. doi: 10.1126/science.3101178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ortiz de Montellano PR. Trends Pharm. Sci. 1989;10:354–359. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(89)90007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Jin Y, Lipscomb JD. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2001;6:717–725. doi: 10.1007/s007750100250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a Broadwater JA, Whittle E, Shanklin J. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:15613–15620. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200231200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Behrouzian B, Savile CK, Dawson B, Buist PH, Shanklin J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:3277–3283. doi: 10.1021/ja012252l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Collins JR, Camper DL, Loew GH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:2736–2743. [Google Scholar]; (b) Buist PH, Marecak DM. Can. J. Chem. 1994;72:176–181. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar D, de Visser SP, Shaik S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:5072–5073. doi: 10.1021/ja0318737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Broun P, Shanklin J, Whittle E, Somerville C. Science. 1998;282:1315–1317. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5392.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Guy JE, Abreu IA, Moche M, Lindqvist Y, Whittle E, Shanklin J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:17220–17224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607165103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Retey J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1990;29:355–361. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Lange SJ, Que L. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 1998;2:159–172. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(98)80057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Groves JT, Nemo TE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:6243–6248. [Google Scholar]; (c) Meunier B, Robert A, Genevieve P, Bernadou J. Chapter 31. In: Kadish KM, Smith KM, Guilard R, editors. The Porphyrin Handbook. Vol. 4. San Diego: Academic Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]; (d) Costas M, Mehn MP, Jensen MP, Que L. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:939–986. doi: 10.1021/cr020628n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Que L. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:493–500. doi: 10.1021/ar700024g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Nam W. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:522–531. doi: 10.1021/ar700027f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Feiters MC, Rowan AE, Nolte RJM. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2000;29:375–384. [Google Scholar]; (h) Murahashi SI, Zhang D. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008;37:1490–1501. doi: 10.1039/b706709g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Bell CB, Wong SD, Xiao YM, Klinker EJ, Tenderholt AL, Smith MC, Rohde JU, Que L, Cramer SP, Solomon EI. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:9071–9074. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Hirao H, Kumar D, Que L, Shaik S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:8590–8606. doi: 10.1021/ja061609o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Bell SR, Groves JT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:9640–9641. doi: 10.1021/ja903394s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Pan Z, Wang Q, Sheng X, Horner JH, Newcomb M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:2621–2628. doi: 10.1021/ja807847q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Martinho M, Xue G, Fiedler AT, Que L, Bominaar EL, Münck E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:5823–5830. doi: 10.1021/ja8098917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim C, Dong Y, Que L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:3635–3636. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wada T, Tsuge K, Tanaka K. Chem. Lett. 2000:910–911. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu AJ, Penner-Hahn JE, Pecoraro VL. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:903–938. doi: 10.1021/cr020627v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Wydrzynski TJ, Satoh K, editors. Photosystem II: The Light-Driven Water-Plastoquinone Oxidoreductase (Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration. Vol. 22. Dordrecht: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]; (b) Brudvig GW, Thorp HH, Crabtree RH. Acc. Chem. Res. 1991;24:311–316. [Google Scholar]; (c) Mukhopadhyay S, Mandal SK, Bhaduri S, Armstrong WH. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:3981–4026. doi: 10.1021/cr0206014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) McEvoy JP, Brudvig GW. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:4455–4483. doi: 10.1021/cr0204294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Dau H, Haumann M. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2008;252:273–295. [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Groves JT, Lee J, Marla SS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:6269–6273. [Google Scholar]; (b) Jin N, Groves JT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:2923–2924. [Google Scholar]; (c) Nam W, Kim I, Lim MH, Choi HJ, Lee JS, Jang HG. Chem. Eur. J. 2002;8:2067–2071. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20020503)8:9<2067::AID-CHEM2067>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Zhang R, Newcomb M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:12418–12419. doi: 10.1021/ja0377448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Zhang R, Horner JH, Newcomb M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:6573–6582. doi: 10.1021/ja045042s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Gross Z, Golubkov G, Simkhovich L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000;39:4045–4047. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20001117)39:22<4045::aid-anie4045>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Song WJ, Seo MS, George SD, Ohta T, Song R, Kang M-J, Tosha T, Kitagawa T, Solomon EI, Nam W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:1268–1277. doi: 10.1021/ja066460v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Jin N, Ibrahim M, Spiro TG, Groves JT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12416–12417. doi: 10.1021/ja0761737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Arunkumar C, Lee Y-M, Lee JY, Fukuzumi S, Nam W. Chem. Eur. J. 2009;15:11482–11489. doi: 10.1002/chem.200901362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Fukuzumi S, Fujioka N, Kotani H, Ohkubo K, Lee Y-M, Nam W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:17127–17134. doi: 10.1021/ja9045235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Noodleman L, Lovell T, Han W-G, Li J, Himo F. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:459–508. doi: 10.1021/cr020625a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Siegbahn PEM, Blomberg MRA. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:421–438. doi: 10.1021/cr980390w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Balcells D, Raynaud C, Crabtree RH, Eisenstein O. Chem. Commun. 2008:744–746. doi: 10.1039/b715939k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Balcells D, Raynaud C, Crabtree RH, Eisenstein O. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:10090–10099. doi: 10.1021/ic8013706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Balcells D, Raynaud C, Crabtree RH, Eisenstein O. Chem. Commun. 2009:1772–1774. doi: 10.1039/b821029b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Angelis F, Jin N, Car R, Groves JT. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:4268–4276. doi: 10.1021/ic060306s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Zhang W, Loebach JL, Wilson SR, Jacobsen EN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:2801–2803. [Google Scholar]; (b) Deubel DV, Frenking G, Gisdakis P, Herrmann WA, Rösch N, Sundermeyer J. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004;37:645–652. doi: 10.1021/ar0400140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Xia Q-H, Ge H-Q, Ye C-P, Liu Z-M, Su K-X. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:1603–1662. doi: 10.1021/cr0406458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) McGarrigle EM, Gilheany DG. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:1563–1602. doi: 10.1021/cr0306945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Limburg J, Vrettos JS, Liable-Sands LM, Rheingold AL, Crabtree RH, Brudvig GW. Science. 1999;283:1524–1527. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5407.1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Limburg J, Vrettos JS, Chen H, de Paula JC, Crabtree RH, Brudvig GW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:423–430. doi: 10.1021/ja001090a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Tagore R, Crabtree RH, Brudvig GW. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:1815–1823. doi: 10.1021/ic062218d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hull JF, Sauer ELO, Incarvito CD, Faller JW, Brudvig GW, Crabtree RH. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:488–495. doi: 10.1021/ic8013464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Das S, Incarvito CD, Crabtree RH, Brudvig GW. Science. 2006;312:1941–1943. doi: 10.1126/science.1127899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Both geometry scans and direct TS search calculations could not be completed because we were unable to converge the wave function, which may be due to the multireference character of the triplet.

- 25.(a) Ogliaro F, Harris N, Cohen S, Filatov M, de Visser SP, Shaik S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:8977–8989. [Google Scholar]; (b) Schöneboom JC, Cohen S, Lin H, Shaik S, Thiel W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:4017–4034. doi: 10.1021/ja039847w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.We find a transition state for the rotation of the Mn-OH bond in the isolated [Mn(OH)(por)(Cl)] complex, which results from removing the MHP• radical. The values of θ for the reactant, transition state and product are 51.0°, 89.7° and 123.2°, respectively. The energies associated with this reaction, ΔE = 0.0 kcal mol−1 and ΔE‡ = 0.5 kcal mol−1, confirm that this process is essentially isotherm and barrier-free, as suggested by the relaxed energy scan of Figure 3. These three stationary points are fully optimized on the high spin quartet surface. See the Supporting Information for further details.

- 27.The OH rebound transition state could not be optimized, due to convergence problems associated with the multireference character of the triplet. Nevertheless, when the O⋯C distance is shortened to 2.00 Å, subsequent full optimization yields the hydroxylation product, T-4. For desaturation, the transition state could not be located either. However, the optimization of the θ = 150° conformation yields the desaturation product, T-6. These results suggest that the triplet state promotes either hydroxylation or desaturation depending on the orientation of the OH group, in the same manner described for the quintet.

- 28.Bassan A, Blomberg MRA, Siegbahn PEM. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2004;9:439–452. doi: 10.1007/s00775-004-0537-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.(a) Khenkin AM, Neumann R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:4198–4199. doi: 10.1021/ja0178721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kamata K, Kasai J, Yamaguchi K, Mizuno N. Org. Lett. 2004;6:3577–3580. doi: 10.1021/ol0485363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Neumann R, Lissel M. J. Org. Chem. 1989;54:4607–4610. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sameera WMC, McGrady JE. Dalton Trans. 2008:6141–6149. doi: 10.1039/b809868a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guallar V, Gherman BF, Miller WH, Lippard SJ, Friesner RA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:3377–3384. doi: 10.1021/ja0167248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar D, Tahsini L, de Visser SP, Kang HY, Kim SJ, Nam W. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2009;113:11713–11722. doi: 10.1021/jp9028694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.(a) Perdew JP. Phys. Rev. B. 1986;33:8822–8824. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.33.8822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Perdew JP. Phys. Rev. B. 1986;34:7406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Becke A. Phys. Rev. A. 1988;38:3098–3100. doi: 10.1103/physreva.38.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.(a) Andrae D, Haüssermann U, Dolg M, Stoll H, Preuss H. Theor. Chim. Acta. 1990;77:123–141. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bergner A, Dolg M, Küchle W, Stoll H, Preuss H. Mol. Phys. 1993;30:1431–1441. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hehre WJ, Ditchfield R, Pople JA. J. Phys. Chem. 1972;56:2257–2261. [Google Scholar]

- 36.(a) Ehlers AW, Böhme M, Dapprich S, Gobbi A, Hollwarth A, Jonas V, Köhler KF, Stegmann R, Veldkamp A, Frenking G. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1993;208:111–114. [Google Scholar]; (b) Höllwarth A, Böhme H, Dapprich S, Ehlers AW, Gobbi A, Jonas V, Köhler KF, Stegmann R, Veldkamp A, Frenking G. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1993;203:237–240. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hariharan PC, Pople JA. Theor. Chim. Acta. 1973;28:213–222. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barone V, Cossi M. J. Phys. Chem. A. 1998;102:1995–2001. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reed AE, Curtiss LA, Weinhold F. Chem. Rev. 1988;88:899–926. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frisch MJ, et al. GAUSSIAN 03, revision D.01. Wallingford, CT: Gaussian, Inc; 2004. (the full reference is given in the Supporting Information) [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harvey JN, Aschi M, Schwarz H, Koch W. Theor. Chem. Acc. 1998;99:95–99. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.