Abstract

In vitro studies show that docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) can be released from membrane phospholipid by Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2 (iPLA2), Ca2+-independent plasmalogen PLA2 or secretory PLA2 (sPLA2), but not by Ca2+-dependent cytosolic PLA2 (cPLA2), which selectively releases arachidonic acid (AA). Since glutamatergic NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) receptor activation allows extracellular Ca2+ into cells, we hypothesized that brain DHA signaling would not be altered in rats given NMDA, to the extent that in vivo signaling was mediated by Ca2+-independent mechanisms. Isotonic saline, a subconvulsive dose of NMDA (25 mg/kg), MK-801, or MK-801 followed by NMDA was administered i.p. to unanesthetized rats. Radiolabeled DHA or AA was infused intravenously and their brain incorporation coefficients k*, measures of signaling, were imaged with quantitative autoradiography. NMDA or MK-801 compared with saline did not alter k* for DHA in any of 81 brain regions examined, whereas NMDA produced widespread and significant increments in k* for AA. In conclusion, in vivo brain DHA but not AA signaling via NMDA receptors is independent of extracellular Ca2+ and of cPLA2. DHA signaling may be mediated by iPLA2, plasmalogen PLA2, or other enzymes insensitive to low concentrations of Ca2+. Greater AA than DHA release during glutamate-induced excitotoxicity could cause brain cell damage.

Keywords: arachidonic, calcium, cPLA2, iPLA2, NMDA, MK-801, imaging

Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3) and arachidonic acid (AA, 20:4n-6) are abundant polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) in brain, where they and their metabolites influence neurotransmission, membrane remodeling, gene transcription, blood flow, neuroinflammation, and other parameters (1–3). These PUFAs are concentrated in the stereospecifically numbered-2 position of synaptic membrane phospholipids, from which they can be hydrolyzed by phospholipases A2 enzymes (PLA2, EC 3.1.1.4) (3–5).

Four major PLA2 subclasses are described in mammalian brain based on in vitro studies: Ca2+-dependent cytosolic cPLA2 type IV [cPLA2α (type IVA) and β are Ca2+-dependent, cPLA2γ is not], Ca2+-dependent secretory sPLA2, Ca2+-independent iPLA2 (β and γ), and Ca2+-independent plasmalogen PLA2 (6, 7). cPLA2 (α and β) requires a low concentration of Ca2+ for its translocation to the membrane and activation (0.3–1 μM) and is selective for AA during acute stimulation of cells by diverse agents in vitro (8, 9). iPLA2 does not require Ca2+ for activation (10–12) and is selective for DHA in isolated glial cells and in the test tube (13). Plasmalogen PLA2 releases DHA from plasmalogen ethanolamine (7, 14). sPLA2 requires millimolar Ca2+ concentrations for activation and releases AA and DHA in vitro (6, 7).

cPLA2 and iPLA2 have been identified at postsynaptic sites and glia in the vertebrate brain, sPLA2 at presynaptic sites, and plasmalogen PLA2 in neurons and glia (7, 15–17). Despite their different brain distributions and varying Ca2+ dependencies shown by in vitro studies, little information is available about the in vivo roles of the different PLA2 enzymes to brain signaling involving AA and DHA. We therefore thought it of interest to examine and compare how in vivo signaling involving the two PUFAs depends on entry of extracellular Ca2+ in cells.

In this regard, binding of glutamate or N-methyl-D- aspartic acid (NMDA) to ionotropic NMDA receptors that are highly expressed in brain (18) is known to cause extracellular Ca2+ entry into the cell and stimulate Ca2+-sensitive cPLA2 to release AA from membrane phospholipid (19–21). Increments in intracellular Ca2+ following NMDA are ≤1 μM (22, 23). Using our imaging method involving the intravenous infusion of [1-14C]AA (24, 25), we reported that administration of a subconvulsive dose of NMDA (25 mg/kg i.p.) to unanesthetized rats increased AA signaling, measured as increased AA incorporation coefficients k*, in wide areas of brain (26–28). The increases could be blocked by pretreatment with the NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801, which by itself reduced baseline values of k* by 16–49% (26).

In the present study, we employed our in vivo imaging method to determine the dependence of in vivo brain DHA signaling on extracellular Ca2+, compared to AA signaling. We hypothesized that the DHA signal would not be altered following NMDA, to the extent that it is mediated by iPLA2, plasmalogen PLA2, or another Ca2+-independent enzyme (see above). We administered (i.p.) isotonic saline, a subconvulsive dose of NMDA (25 mg/kg), MK-801, or MK-801 followed by NMDA, to unanesthetized male adult rats. Radiolabeled DHA (or AA as a control) was infused intravenously for 5 min, and brain incorporation coefficients k* were imaged using quantitative autoradiography at 20 min. We confirmed that NMDA widely increased AA incorporation coefficients k* in brain, whereas it had no significant effect on DHA incorporation coefficients in any of 81 measured brain regions. Thus, extracellular-derived Ca2+ and cPLA2 are not involved in brain DHA signaling in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Experiments were conducted following the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” (National Institutes of Health Publication No. 86-23) and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Three-month-old male Fischer F344 rats (Taconic Farms, Rockville, MD) were acclimated for 1 week in an animal facility having regulated temperature, humidity, and a light-dark cycle. The rats had ad libitum access to water and food (Rodent NIH-31 auto 18-4 diet, Zeigler Bros, Gardners, PA). The diet contained (as percent of total fatty acids) 20.0% saturated, 22.5% monounsaturated, 47.9% linoleic, 5.1% α-linolenic, 0.2% AA, 2.0% eicosapentaenoic, and 2.3% DHA acids (29).

Drugs

NMDA and MK-801 ((5R,10S)-(+)-5-methyl-10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[a,d]cyclohepten-5,10-imine hydrogen maleate) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO) and 0.9% NaCl (saline USP) was purchased from Hospira (Lake Forest, IL). [1-14C]AA in ethanol (53 mCi/mmol, >98% pure (Moravek Biochemicals, Brea, CA) or [1-14C]DHA in ethanol (56 mCi/mmol, >98% pure, Moravek) was evaporated and resuspended in HEPES buffer, pH 7.4, containing 50 mg/ml BSA, as described (30). To confirm tracer purity, thin-layer chromatography was performed and radioactivity of each band was measured by scintillation counter. 98% of radioactivity was detected in the fatty acid band. Gas chromatography was performed to confirm the identity of the fatty acid (31).

Surgical procedures and tracer infusion

In the morning of an experiment, a rat was anesthetized with 2–3% halothane in O2. Polyethylene catheters were inserted into the right femoral artery and vein, as described (26). The rat was allowed to recover from anesthesia for 3 h in a sound-dampened, temperature-controlled box with its hindquarters loosely wrapped and taped to a wooden block. Arterial blood pressure and heart rate were measured with a blood pressure recorder (CyQ 103/302; Cybersense, Inc., Nicholasville, KY). Arterial blood pH, partial pressure of oxygen (pO2), and partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2) were measured with a blood gas analyzer (Model 248, Bayer Health Care, Norwood, MA).

Ten min after i.p. saline or i.p. NMDA (25 mg/kg), or 30 min after MK-801 (0.3 mg/kg i.p.), [1-14C]DHA (170 µCi/kg) was infused into the femoral vein for 5 min at a rate of 400 µl/min using an infusion pump (Harvard Apparatus Model 22, Natick, MA) (26). For studies with both drugs, MK-801 was administered 30 min prior to NMDA, which was given 10 min before the radioisotope. For the AA study, saline or NMDA (25 mg/kg) was injected 10 min before [1-14C]AA (170 µCi/kg) infusion. Twenty min after beginning tracer infusion in either case, the rat was euthanized with Nembutal® (80 mg/kg, i.v.). The brain was removed within 30 s, frozen in 2-methylbutane maintained at −40°C with dry ice, and stored at −80°C.

Chemical analysis

Thirteen arterial blood samples, collected before, during, and after [1-14C]AA or [1-14C]DHA infusion, were centrifuged immediately (30 s at 18,000 g) to determine unesterified plasma DHA or AA radioactivity. Total lipids were extracted from 30 µl plasma with 3 ml chloroform:methanol (2:1, v/v) and 1.5 ml KCl (0.1 M) (32). Radioactivity was determined in 100 µl of the organic phase by liquid scintillation counting. As reported, after a 5 min [1-14C]AA or [1-14C]DHA infusion, >97% of plasma radioactivity was the infused radiolabeled PUFA (33, 34).

Quantitative autoradiography

Frozen brains were cut in serial 20-μm thick coronal sections on a cryostat at −20°C, then placed for 4–5 weeks with calibrated [14C]methylmethacrylate standards (Amersham Life Science, Arlington Heights, IL) on Ektascan C/RA film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). Radioactivity (nCi/g wet weight brain) in 81 identified regions (35) was measured bilaterally six times by quantitative densitometry, using the public domain NIH Image program 1.62. Regional incorporation coefficients k* (ml/s/g brain) of AA or DHA were calculated as follows (equation 1):

| (Eq. 1) |

(nCi/g wet brain wt) is brain radioactivity 20 min after beginning infusion, (nCi/ml plasma) is arterial labeled unesterified fatty acid as determined by scintillation counting, and t (min) is time after beginning [1-14C]fatty acid infusion. Integrated plasma radioactivity (input function in denominator) was determined in each experiment by trapezoidal integration and used to calculate k* for each experiment.

Statistical analyses

Physiological parameters were analyzed by paired t-tests in the same animal before and after drug injection (GraphPad Prism Software, San Diego, CA). Statistical significance of drug on arterial plasma radioactivity and on k* for each brain region was determined by one-way ANOVA (ANOVA) with Dunnett's post-test for DHA infusion or an unpaired t-test for AA infusion. Corrections for multiple comparisons across regions were not made because this was an exploratory study to identify regions that are involved in individual drug effects. Data are reported as mean ± SD, with statistical significance set at P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Physiology and arterial plasma radioactivity

For the DHA infusion study, NMDA (25 mg/kg, i.p.) compared with saline significantly decreased heart rate by 11% (387 ± 46 versus 442 ± 25 beats/min, P < 0.05) but did not have a significant effect on arterial blood pressure, whereas MK-801 alone or before NMDA increased systolic arterial blood pressure by 9–13% in the unanesthetized rats (P < 0.05; n = 7–8). Arterial blood pressure (mmHg) was as follows: before MK-801 (169 ± 10); after MK-801 (184 ± 9); before MK-801 and NMDA (176 ± 10); after MK-801 and NMDA (199 ± 22). Such changes, reported previously, have been ascribed to a centrally mediated increase in sympathetic nerve activity by MK-801 (26). MK-801 given before NMDA abolished NMDA's significant effect on heart rate and decreased plasma pH (data not shown).

A one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's test showed that MK-801 significantly (P < 0.01) increased mean integrated radioactivity by 42% in the plasma organic fraction, the input function for determining k* in equation 1 during [1-14C]DHA infusion. Mean integrated radioactivity (nCi/s)/ml) was as follows: saline (144,723 ± 34,385); NMDA (141,659 ± 34,451); MK-801 (205,895 ± 33,515); MK-801 + NMDA (181,283 ± 40,200).

For the reference AA infusion study, NMDA significantly decreased heart rate by 16% (data not shown). Unpaired t-tests showed that NMDA significantly increased integrated plasma radioactivity during [1-14C]AA infusion by 21% (P = 0.04) [NMDA (114,173 ± 20,236) versus saline (94,118 ± 15,356) nCi/s/ml].

Regional brain DHA and AA incorporation coefficients, k*

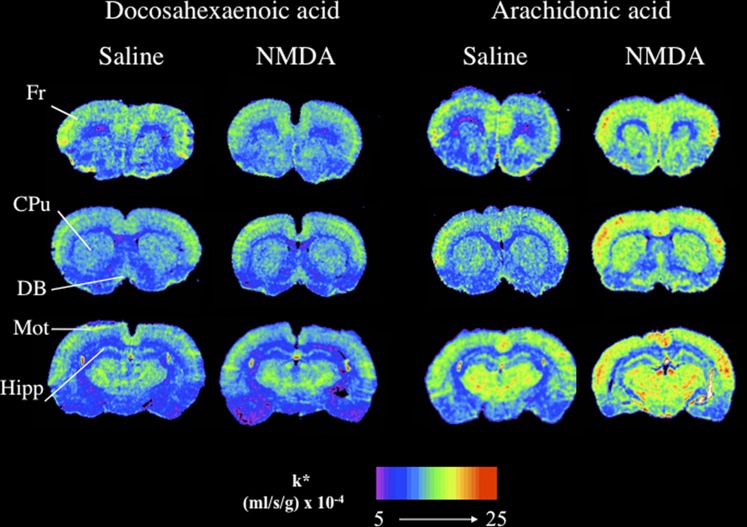

As shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1, NMDA compared with saline did not increase k* for DHA significantly in any of the 81 regions examined. Also, MK-801 given alone or 30 min prior NMDA had no effect on k* for DHA in any region (data not shown). In contrast, NMDA compared with saline significantly increased k* for AA by 20–86% in 54 of 81 regions. Affected regions included prefrontal cortex (38–46%), frontal cortex (23–30%), piriform cortex (32%), motor cortex (40–58%), somatosensory cortex (32–41%), auditory cortex (25–39%), hippocampus (40–86%), nucleus accumbens (26%), caudate putamen (39–48%), septal nuclei (44–70%), some regions of the thalamus (20–38%), hypothalamus (24–72%), two white matter regions (58–77%), and two nonblood brain barrier regions (51–69%).

TABLE 1.

Docosahexaenoic and arachidonic acid incorporation coefficients k* in rats in response to saline and NMDA

| DHA |

AA |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain Region | Saline(n = 8) | NMDA(n = 7) | Saline(n = 8) | NMDA(n = 8) |

| Prefrontal cortex layer I | 8.68 ± 2.28 | 8.09 ± 2.59 | 8.45 ± 0.87 | 12.33 ± 2.83a |

| Prefrontal cortex layer IV | 9.56 ± 2.77 | 9.42 ± 4.03 | 10.09 ± 1.39 | 13.90 ± 3.30a |

| Primary olfactory cortex | 8.45 ± 1.25 | 8.80 ± 1.53 | 10.06 ± 2.15 | 12.36 ± 2.60 |

| Frontal cortex (10) | ||||

| Layer I | 8.43 ± 2.25 | 7.73 ± 2.39 | 9.02 ± 1.49 | 11.10 ± 3.42a |

| Layer IV | 9.51 ± 2.71 | 9.43 ± 4.60 | 10.85 ± 1.54 | 13.87 ± 3.11b |

| Frontal cortex (8) | ||||

| Layer I | 9.04 ± 2.06 | 7.39 ± 1.40 | 10.84 ± 2.06 | 14.05 ± 2.88b |

| Layer IV | 9.18 ± 1.98 | 9.60 ± 1.10 | 12.70 ± 1.99 | 15.78 ± 2.80b |

| Piriform cortex | 6.52 ± 1.27 | 5.74 ± 2.37 | 6.92 ± 3.90 | 9.13 ± 2.10a |

| Anterior cingulate cortex | 8.65 ± 2.27 | 9.16 ± 1.56 | 12.50 ± 2.29 | 14.64 ± 2.75 |

| Motor cortex | ||||

| Layer I | 8.43 ± 2.36 | 8.53 ± 3.66 | 7.30 ± 2.06 | 11.50 ± 2.32a |

| Layer II – III | 8.53 ± 2.65 | 8.81 ± 3.75 | 8.39 ± 1.66 | 12.35 ± 2.28a |

| Layer IV | 9.76 ± 2.33 | 10.45 ± 4.10 | 9.74 ± 1.43 | 13.59 ± 2.23a |

| Layer V | 7.41 ± 2.32 | 8.19 ± 3.19 | 9.18 ± 2.12 | 12.92 ± 2.70a |

| Layer VI | 7.82 ± 2.47 | 8.80 ± 3.30 | 8.62 ± 1.84 | 12.36 ± 2.17a |

| Somatosensory cortex | ||||

| Layer I | 9.57 ± 2.53 | 9.64 ± 3.57 | 8.12 ± 2.25 | 11.21 ± 5.14 |

| Layer II–III | 9.53 ± 2.65 | 10.42 ± 4.86 | 9.02 ± 2.07 | 12.72 ± 2.89b |

| Layer IV | 9.21 ± 1.69 | 10.69 ± 1.09 | 11.01 ± 1.62 | 14.49 ± 2.60a |

| Layer V | 8.69 ± 2.18 | 9.01 ± 1.68 | 9.95 ± 1.27 | 13.31 ± 2.71a |

| Layer VI | 8.28 ± 1.92 | 8.35 ± 1.45 | 9.31 ± 1.86 | 13.00 ± 2.65a |

| Auditory cortex | ||||

| Layer I | 8.66 ± 2.41 | 8.24 ± 2.59 | 10.32 ± 2.92 | 13.45 ± 1.97b |

| Layer IV | 8.17 ± 2.52 | 6.91 ± 1.81 | 13.02 ± 2.76 | 16.34 ± 1.94b |

| Layer VI | 6.77 ± 1.28 | 6.62 ± 1.68 | 10.45 ± 2.96 | 14.54 ± 1.70a |

| Visual cortex | ||||

| Layer I | 8.93 ± 2.37 | 7.04 ± 1.45 | 8.46 ± 3.29 | 11.99 ± 3.97 |

| Layer IV | 9.33 ± 2.40 | 7.91 ± 1.99 | 11.23 ± 2.96 | 14.27 ± 3.88 |

| Layer VI | 8.91 ± 1.68 | 7.04 ± 1.45 | 9.52 ± 3.25 | 12.90 ± 3.42 |

| Preoptic area (LPO/MPO) | 6.04 ± 1.05 | 6.08 ± 1.56 | 6.66 ± 1.70 | 10.46 ± 1.84a |

| Suprachiasmatic nu | 7.06 ± 1.33 | 6.90 ± 1.05 | 7.87 ± 1.43 | 10.78 ± 2.34a |

| Globus pallidus | 6.89 ± 1.41 | 5.91 ± 1.54 | 6.97 ± 1.69 | 10.20 ± 1.93a |

| Bed nu stria terminalis | 6.72 ± 1.54 | 6.37 ± 2.01 | 6.19 ± 2.06 | 8.59 ± 1.51b |

| Olfactory tubercle | 7.58 ± 1.06 | 7.38 ± 1.37 | 8.73 ± 2.51 | 11.86 ± 1.85b |

| Diagonal band dorsal | 7.76 ± 1.44 | 6.94 ± 1.79 | 8.62 ± 1.50 | 12.15 ± 3.73b |

| Diagonal band ventral | 7.52 ± 1.95 | 6.46 ± 1.37 | 8.16 ± 1.79 | 12.29 ± 2.87a |

| Amygdala basolat/med | 6.28 ± 1.17 | 6.00 ± 1.43 | 5.03 ± 2.58 | 8.99 ± 1.95a |

| Hippocampus CA1 | 5.90 ± 0.99 | 5.85 ± 1.65 | 4.49 ± 2.59 | 7.49 ± 1.79b |

| Hippocampus CA2 | 5.87 ± 0.72 | 5.23 ± 1.16 | 4.66 ± 2.32 | 8.04 ± 1.98a |

| Hippocampus CA3 | 5.77 ± 1.15 | 5.58 ± 1.73 | 4.58 ± 2.32 | 8.51 ± 1.77a |

| Hippocampus dentate gyrus | 7.47 ± 1.61 | 7.18 ± 1.32 | 5.74 ± 2.76 | 9.49 ± 1.54a |

| Hippocampus SLM | 7.69 ± 2.05 | 7.88 ± 2.00 | 9.28 ± 1.25 | 13.01 ± 2.43a |

| Nucleus accumbens | 8.94 ± 2.18 | 7.74 ± 1.88 | 10.16 ± 1.28 | 12.83 ± 3.16b |

| Caudate putamen | ||||

| Dorsal | 7.17 ± 1.52 | 7.34 ± 2.84 | 8.32 ± 1.67 | 11.75 ± 3.26b |

| Ventral | 8.12 ± 1.94 | 8.13 ± 3.23 | 8.18 ± 2.14 | 12.08 ± 3.12b |

| Lateral | 8.80 ± 2.58 | 7.46 ± 1.96 | 8.42 ± 1.96 | 11.99 ± 2.85b |

| Medial | 8.22 ± 2.08 | 7.81 ± 3.34 | 8.26 ± 1.93 | 11.49 ± 2.86b |

| Septal nu lateral | 7.33 ± 1.76 | 6.08 ± 1.94 | 5.63 ± 2.29 | 9.57 ± 2.65a |

| Septal nu medial | 7.64 ± 2.24 | 8.68 ± 3.92 | 8.59 ± 1.34 | 12.35 ± 3.68b |

| Habenular nu lateral | 10.11 ± 2.72 | 11.12 ± 3.78 | 14.00 ± 2.65 | 15.58 ± 2.96 |

| Habenular nu medial | 9.46 ± 2.45 | 7.63 ± 1.85 | 10.81 ± 2.08 | 13.43 ± 3.29 |

| Lat geniculate nu dorsal | 9.91 ± 2.70 | 9.50 ± 4.41 | 12.77 ± 2.22 | 15.05 ± 2.43 |

| Geniculate medial | 9.19 ± 1.94 | 8.90 ± 2.41 | 14.45 ± 3.24 | 16.56 ± 2.49 |

| Thalamus | ||||

| Ventroposterior lateral nu | 8.42 ± 1.59 | 7.75 ± 1.82 | 12.18 ± 1.82 | 14.33 ± 3.07 |

| Ventroposterior medial nu | 7.82 ± 1.52 | 8.66 ± 1.88 | 12.13 ± 1.57 | 14.38 ± 2.76 |

| Paratenial nu | 7.41 ± 1.48 | 6.60 ± 2.08 | 9.10 ± 1.73 | 11.76 ± 3.21 |

| Anteroventral nu | 10.34 ± 2.00 | 11.06 ± 3.03 | 14.34 ± 2.15 | 15.62 ± 2.87 |

| Anteromedial nu | 7.90 ± 1.81 | 9.74 ± 4.89 | 12.39 ± 1.52 | 15.15 ± 2.69b |

| Reticular nu | 7.92 ± 2.62 | 7.97 ± 2.41 | 11.40 ± 1.36 | 13.68 ± 2.54b |

| Paraventricular nu | 7.67 ± 2.09 | 7.72 ± 2.64 | 8.29 ± 2.14 | 11.45 ± 2.64b |

| Parafascicular nu | 8.82 ± 2.18 | 7.77 ± 2.43 | 11.87 ± 2.19 | 14.37 ± 2.92 |

| Subthalamic nu | 9.08 ± 1.41 | 8.58 ± 1.54 | 10.45 ± 1.03 | 12.91 ± 3.55 |

| Hypothalamus | ||||

| Supraoptic nu | 7.87 ± 2.00 | 6.46 ± 3.32 | 9.05 ± 1.10 | 11.21 ± 1.62a |

| Lateral | 7.09 ± 1.43 | 6.06 ± 1.54 | 6.65 ± 2.04 | 10.38 ± 2.62a |

| Anterior | 7.44 ± 1.84 | 6.26 ± 1.97 | 6.55 ± 2.52 | 10.40 ± 2.27a |

| Periventricular | 5.84 ± 1.38 | 4.70 ± 1.45 | 6.34 ± 2.61 | 9.70 ± 2.46b |

| Arcuate | 7.01 ± 1.58 | 6.23 ± 2.27 | 6.01 ± 2.40 | 10.11 ± 2.96a |

| Ventromedial | 6.84 ± 1.38 | 6.19 ± 2.31 | 6.22 ± 2.05 | 10.69 ± 2.81a |

| Posterior | 7.44 ± 1.81 | 6.73 ± 1.69 | 6.56 ± 1.93 | 10.12 ± 2.69a |

| Mammillary nu | 8.47 ± 2.79 | 8.81 ± 4.85 | 6.09 ± 1.74 | 9.55 ± 1.80a |

| Interpeduncular nu | 9.29 ± 3.13 | 10.53 ± 5.22 | 17.88 ± 2.30 | 18.81 ± 3.45 |

| Substantia nigra | 7.89 ± 1.72 | 6.09 ± 1.87 | 9.62 ± 2.94 | 11.81 ± 3.76 |

| Pretectal area | 7.82 ± 2.61 | 7.38 ± 1.62 | 13.10 ± 2.85 | 14.61 ± 3.38 |

| Superior colliculus | 8.87 ± 1.70 | 8.91 ± 2.58 | 14.12 ± 2.32 | 14.51 ± 2.73 |

| Deep layers | 7.71 ± 1.15 | 7.92 ± 1.91 | 11.93 ± 3.02 | 14.89 ± 2.52 |

| Inferior colliculus | 15.22 ± 4.26 | 15.27 ± 3.11 | 19.90 ± 3.11 | 22.75 ± 4.39 |

| Flocculus | 9.60 ± 2.61 | 9.58 ± 3.16 | 18.34 ± 2.88 | 19.01 ± 2.65 |

| Cerebellar gray matter | 11.51 ± 2.32 | 11.48 ± 3.46 | 14.64 ± 2.49 | 15.48 ± 2.71 |

| Molecular layer cerebellar gray matter | 12.92 ± 2.28 | 14.48 ± 2.22 | 17.88 ± 2.49 | 17.80 ± 2.98 |

| White matter | ||||

| Corpus callosum | 6.18 ± 0.96 | 5.10 ± 1.11 | 4.94 ± 1.78 | 8.73 ± 3.42b |

| Zone incerta | 7.37 ± 1.26 | 8.00 ± 1.56 | 11.04 ± 2.00 | 13.00 ± 3.32 |

| Internal capsule | 4.76 ± 0.85 | 4.29 ± 1.78 | 4.01 ± 2.30 | 6.34 ± 1.84b |

| Cerebellar white matter | 10.83 ± 3.60 | 7.77 ± 2.58 | 5.72 ± 3.00 | 7.76 ± 1.39 |

| Non-blood brain barrier regions | ||||

| Subfornical organ | 7.37 ± 2.14 | 6.91 ± 1.73 | 6.56 ± 2.31 | 9.89 ± 1.90a |

| Median eminence | 7.14 ± 2.20 | 6.85 ± 3.61 | 5.93 ± 1.64 | 10.01 ± 3.26b |

k* = (ml/s/g) × 1024. Each value is mean ± SD. NMDA administration: 25 mg/kg i.p. 10 min. Abbreviations: AA, arachidonic acid; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; lat, lateral; LPO, lateral preoptic area; med, medial; MPO, medial preoptic area; nu, nucleus; NMDA, N-methyl-D-aspartic acid; SLM, stratum lacunosum-moleculae of hippocampus.

P < 0.01; unpaired t-test.

P < 0.05; unpaired t-test.

Fig. 1.

Coronal autoradiographs showing effects of NMDA on regional brain docosahexaenoic and arachidonic acid incorporation coefficients k* in rats. Values of k* (ml/s/g brain × 10−4) are given on a color scale. CPu, caudate-putamen; DB, diagonal band; Fr, frontal cortex; Hipp, hippocampus; Mot, motor cortex; NMDA, N-methyl-D-aspartic acid.

DISCUSSION

An acutely administered subconvulsive dose of NMDA (25 mg/kg i.p.) in unanesthetized rats, compared with i.p. saline control, failed to induce a significant change in the brain DHA incorporation coefficient k* in any of 81 regions imaged using quantitative autoradiography. MK-801 also had no effect on baseline k* for DHA. In contrast, we confirmed the report that this dose of NMDA significantly increased k* for AA in wide areas of the brain (26–28).

The baseline values of k* for DHA and AA in this study agree with published data (26–28, 30). k* for each PUFA largely reflects its metabolic loss following its release from membrane phospholipid, as DHA and AA cannot be synthesized de novo in vertebrate tissue and only negligible amounts (< 1%) can be elongated in brain from their circulating precursors α-linolenic (18:3n-3) and linoleic acid (18:2n-6), respectively. Loss is replaced entirely by unesterified PUFA from plasma (2, 29, 36).

The statistically significant increments in k* for AA following NMDA are thought to arise from entry of extracellular Ca2+ into the cell through ionic NMDA receptors to activate cPLA2 and selectively hydrolyze AA from synaptic membrane phospholipid (4, 6, 8, 9, 20, 21). NMDA receptor activation results in intracellular Ca2+ increments of ≤ 1 μM (22, 23), sufficient for displacement of cPLA2 to the membrane, which requires 0.3–1 μM Ca2+. In contrast, the absence of DHA responses to NMDA indicates that the DHA signal is independent of extracellular-derived Ca2+ and cPLA2, and thus likely mediated by a PLA2 whose activation is independent of entry of increments in intracellular Ca2+ of about 1 μM. As discussed above, potential Ca2+-independent candidates are iPLA2 (β and γ) and plasmalogen PLA2, and cPLA2γ (6, 7, 10–13, 37, 38). sPLA2 is an unlikely candidate because of its presynaptic location and its mM requirement for Ca2+ (6, 39). Supporting a role for iPLA2β in DHA signaling in vivo, k* for DHA at rest or in response to stimulation of G-protein-coupled cholinergic muscarinic M1,3,5 receptors by arecoline is decreased in unanesthetized heterozygous and homozygous iPLA2β (VIA)-deficient mice (40). Additionally, in rats whose diets are deficient in n-3 PUFAs, mRNA, protein, and activity levels of iPLA2β are reduced in relation to reduced DHA turnover in brain phospholipid (41, 42).

The absence of significant reductions in k* for DHA following MK-801, in contrast to 16–49% reductions reported for k* for AA following MK-801(26), further indicates that endogenous glutamate is not involved in baseline DHA release. In agreement, exposure of eosinophilic leukemia cells or platelets to a Ca2+-ionophore did not release DHA while releasing AA through cPLA2 activation (9), and chronic NMDA administration to rats increased cPLA2-IVA but not iPLA2-VI expression in brain (43). Under some in vitro conditions, acute NMDA receptor activation may release Ca2+ from intracellular stores by Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) (44, 45), which may indirectly stimulate iPLA2 (46–48). However, our in vivo data do not support this signaling pathway with the dose of NMDA administered.

Our observations may be relevant to excitotoxicity, which involves high brain glutamate concentrations. In rodent models, excitotoxicity is associated with increased brain concentrations of AA and of its proinflammatory metabolites and with increased cPLA2-IVA expression, without a significant change in DHA concentration or iPLA2-VI expression (43, 49, 50). High concentrations of AA and its metabolites can be neurotoxic (51), whereas DHA and its metabolites are considered neuroprotective (1). Thus, increased release of AA but not of DHA due to excessive NMDA receptor activation by glutamate may interfere with brain function and structure (2, 52).

In summary, stimulating brain NMDA receptors in unanesthetized rats by a subconvulsive dose of NMDA does not produce a significant DHA signal, but it produces a robust AA signal. As such stimulation allows extracellular Ca2+ into the cell, these in vivo results are consistent with in vitro evidence that AA is preferentially hydrolyzed from phospholipid by Ca2+-dependent cPLA2 and that the in vivo AA signal following NMDA is a surrogate marker of Ca2+ entry into cells. The absence of a DHA signal in rat brain following NMDA is consistent with in vitro evidence that DHA hydrolysis can be mediated by iPLA2, plasmalogen PLA2, and cPLA2γ, none of which requires Ca2+.

Several human diseases, including Alzheimer disease and bipolar disorder, show upregulated cPLA2-IVA but not iPLA2β expression, with high glutamatergic function and other evidence of excitotoxicity (53–56). Excess release of AA compared with DHA from membrane phospholipid would be expected to disturb the normally balanced interactions between the two PUFAs (52) and disrupt brain function in these diseases.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- AA

- arachidonic acid

- COX

- cyclooxygenase

- DHA

- docosahexaenoic acid

- NMDA

- N-methyl-D-aspartic acid

- PLA2

- phospholipase A2

- cPLA2

- Ca2+-dependent cytosolic PLA2

- iPLA2

- Ca2+-independent PLA2

- sPLA2

- secretory PLA2

- PUFA

- polyunsaturated fatty acid

This work was supported entirely by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging. None of the authors has a financial or other conflict of interest related to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Serhan C. N. 2006. Novel chemical mediators in the resolution of inflammation: resolvins and protectins. Anesthesiol. Clin. 24: 341–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rapoport S. I. 2008. Arachidonic acid and the brain. J. Nutr. 138: 2515–2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uauy R., Dangour A. D. 2006. Nutrition in brain development and aging: role of essential fatty acids. Nutr. Rev. 64: S24–33; discussion S72–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones C. R., Arai T., Bell J. M., Rapoport S. I. 1996. Preferential in vivo incorporation of [3H]arachidonic acid from blood into rat brain synaptosomal fractions before and after cholinergic stimulation. J. Neurochem. 67: 822–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones C. R., Arai T., Rapoport S. I. 1997. Evidence for the involvement of docosahexaenoic acid in cholinergic stimulated signal transduction at the synapse. Neurochem. Res. 22: 663–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burke J. E., Dennis E. A. 2009. Phospholipase A2 structure/function, mechanism and signaling. J. Lipid Res. 50(Suppl): S237–S242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farooqui A. A., Ong W. Y., Horrocks L. A. 2006. Inhibitors of brain phospholipase A2 activity: their neuropharmacological effects and therapeutic importance for the treatment of neurologic disorders. Pharmacol. Rev. 58: 591–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark J. D., Lin L. L., Kriz R. W., Ramesha C. S., Sultzman L. A., Lin A. Y., Milona N., Knopf J. L. 1991. A novel arachidonic acid-selective cytosolic PLA2 contains a Ca2+-dependent translocation domain with homology to PKC and GAP. Cell. 65: 1043–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shikano M., Masuzawa Y., Yazawa K., Takayama K., Kudo I., Inoue K. 1994. Complete discrimination of docosahexaenoate from arachidonate by 85 kDa cytosolic phospholipase A2 during the hydrolysis of diacyl- and alkenylacylglycerophosphoethanolamine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1212: 211–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ackermann E. J., Kempner E. S., Dennis E. A. 1994. Ca2+-independent cytosolic phospholipase A2 from macrophage-like P388D1 cells. Isolation and characterization. J. Biol. Chem. 269: 9227–9233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirashima Y., Farooqui A. A., Mills J. S., Horrocks L. A. 1992. Identification and purification of calcium-independent phospholipase A2 from bovine brain cytosol. J. Neurochem. 59: 708–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang H. C., Mosior M., Johnson C. A., Chen Y., Dennis E. A. 1999. Group-specific assays that distinguish between the four major types of mammalian phospholipase A2. Anal. Biochem. 269: 278–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strokin M., Sergeeva M., Reiser G. 2003. Docosahexaenoic acid and arachidonic acid release in rat brain astrocytes is mediated by two separate isoforms of phospholipase A2 and is differently regulated by cyclic AMP and Ca2+. Br. J. Pharmacol. 139: 1014–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farooqu A. A., Horrocks L. A. 2001. Plasmalogens, phospholipase A2, and docosahexaenoic acid turnover in brain tissue. J. Mol. Neurosci. 16: 263–272, discussion 279–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ong W. Y., Sandhya T. L., Horrocks L. A., Farooqui A. A. 1999. Distribution of cytoplasmic phospholipase A2 in the normal rat brain. J. Hirnforsch. 39: 391–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ong W. Y., Yeo J. F., Ling S. F., Farooqui A. A. 2005. Distribution of calcium-independent phospholipase A2 (iPLA2) in monkey brain. J. Neurocytol. 34: 447–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pardue S., Rapoport S. I., Bosetti F. 2003. Co-localization of cytosolic phospholipase A2 and cyclooxygenase-2 in Rhesus monkey cerebellum. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 116: 106–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Attwell D., Laughlin S. B. 2001. An energy budget for signaling in the grey matter of the brain. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 21: 1133–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weichel O., Hilgert M., Chatterjee S. S., Lehr M., Klein J. 1999. Bilobalide, a constituent of Ginkgo biloba, inhibits NMDA-induced phospholipase A2 activation and phospholipid breakdown in rat hippocampus. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 360: 609–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dumuis A., Sebben M., Haynes L., Pin J. P., Bockaert J. 1988. NMDA receptors activate the arachidonic acid cascade system in striatal neurons. Nature. 336: 68–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lazarewicz J. W., Wroblewski J. T., Palmer M. E., Costa E. 1988. Activation of N-methyl-D-aspartate-sensitive glutamate receptors stimulates arachidonic acid release in primary cultures of cerebellar granule cells. Neuropharmacology. 27: 765–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hough C. J., Irwin R. P., Gao X. M., Rogawski M. A., Chuang D. M. 1996. Carbamazepine inhibition of N-methyl-D-aspartate-evoked calcium influx in rat cerebellar granule cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 276: 143–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dayanithi G., Rage F., Richard P., Tapia-Arancibia L. 1995. Characterization of spontaneous and N-methyl-D-aspartate-induced calcium rise in rat cultured hypothalamic neurons. Neuroendocrinology. 61: 243–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rapoport S. I. 2001. In vivo fatty acid incorporation into brain phospholipids in relation to plasma availability, signal transduction and membrane remodeling. J. Mol. Neurosci. 16: 243–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robinson P. J., Noronha J., DeGeorge J. J., Freed L. M., Nariai T., Rapoport S. I. 1992. A quantitative method for measuring regional in vivo fatty-acid incorporation into and turnover within brain phospholipids: review and critical analysis. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 17: 187–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Basselin M., Chang L., Bell J. M., Rapoport S. I. 2006. Chronic lithium chloride administration attenuates brain NMDA receptor-initiated signaling via arachidonic acid in unanesthetized rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 31: 1659–1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Basselin M., Chang L., Chen M., Bell J. M., Rapoport S. I. 2008. Chronic administration of valproic acid reduces brain NMDA signaling via arachidonic acid in unanesthetized rats. Neurochem. Res. 33: 1373–1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basselin M., Villacreses N. E., Chen M., Bell J. M., Rapoport S. I. 2007. Chronic carbamazepine administration reduces NMDA receptor-initiated signaling via arachidonic acid in rat brain. Biol. Psychiatry. 62: 934–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Demar J. C., Jr., Ma K., Chang L., Bell J. M., Rapoport S. I. 2005. α-Linolenic acid does not contribute appreciably to docosahexaenoic acid within brain phospholipids of adult rats fed a diet enriched in docosahexaenoic acid. J. Neurochem. 94: 1063–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeGeorge J. J., Nariai T., Yamazaki S., Williams W. M., Rapoport S. I. 1991. Arecoline-stimulated brain incorporation of intravenously administered fatty acids in unanesthetized rats. J. Neurochem. 56: 352–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Makrides M., Neumann M. A., Byard R. W., Simmer K., Gibson R. A. 1994. Fatty acid composition of brain, retina, and erythrocytes in breast- and formula-fed infants. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 60: 189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Folch J., Lees M., Sloane Stanley G. H. 1957. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 226: 497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeGeorge J. J., Noronha J. G., Bell J. M., Robinson P., Rapoport S. I. 1989. Intravenous injection of [1-14C]arachidonate to examine regional brain lipid metabolism in unanesthetized rats. J. Neurosci. Res. 24: 413–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bazinet R. P., Rao J. S., Chang L., Rapoport S. I., Lee H-J. 2005. Chronic valproate does not alter the kinetics of docosahexaenoic acid within brain phospholipids of the unanesthetized rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl.). 182: 180–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paxinos G., Watson C. 1987. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Third ed Academic Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeMar J. C. J., Lee H. J., Ma K., Chang L., Bell J. M., Rapoport S. I., Bazinet R. P. 2006. Brain elongation of linoleic acid is a negligible source of the arachidonate in brain phospholipids of adult rats. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1761: 1050–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strokin M., Sergeeva M., Reiser G. 2007. Prostaglandin synthesis in rat brain astrocytes is under the control of the n-3 docosahexaenoic acid, released by group VIB calcium-independent phospholipase A2. J. Neurochem. 102: 1771–1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bao S., Miller D. J., Ma Z., Wohltmann M., Eng G., Ramanadham S., Moley K., Turk J. 2004. Male mice that do not express group VIA phospholipase A2 produce spermatozoa with impaired motility and have greatly reduced fertility. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 38194–38200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matsuzawa A., Murakami M., Atsumi G., Imai K., Prados P., Inoue K., Kudo I. 1996. Release of secretory phospholipase A2 from rat neuronal cells and its possible function in the regulation of catecholamine secretion. Biochem. J. 318: 701–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rapoport S. I., Ramadan E., Kim H. W., Turk J., Basselin M. 2010. Brain docosahexaenoic acid signaling is decreased in unanesthetized iPLA2-VIA(β)-deficient mice (Abstract PSM04–13 in Transactions of the American Society for Neurochemistry, 41st Annual Meeting, Santa Fe, New Mexico, March 6–10, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 41.DeMar J. C., Jr., Ma K., Bell J. M., Rapoport S. I. 2004. Half-lives of docosahexaenoic acid in rat brain phospholipids are prolonged by 15 weeks of nutritional deprivation of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. J. Neurochem. 91: 1125–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rao J. S., Ertley R. N., DeMar J. C., Jr., Rapoport S. I., Bazinet R. P., Lee H-J. 2007. Dietary n-3 PUFA deprivation alters expression of enzymes of the arachidonic and docosahexaenoic acid cascades in rat frontal cortex. Mol. Psychiatry. 12: 151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rao J. S., Ertley R. N., Rapoport S. I., Bazinet R. P., Lee H. J. 2007. Chronic NMDA administration to rats up-regulates frontal cortex cytosolic phospholipase A2 and its transcription factor, activator protein-2. J. Neurochem. 102: 1918–1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hayashi T., Kagaya A., Takebayashi M., Oyamada T., Inagaki M., Tawara Y., Yokota N., Horiguchi J., Su T. P., Yamawaki S. 1997. Effect of dantrolene on KCl- or NMDA-induced intracellular Ca2+ changes and spontaneous Ca2+ oscillation in cultured rat frontal cortical neurons. J. Neural Transm. 104: 811–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Emptage N., Bliss T. V., Fine A. 1999. Single synaptic events evoke NMDA receptor-mediated release of calcium from internal stores in hippocampal dendritic spines. Neuron. 22: 115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolf M. J., Wang J., Turk J., Gross R. W. 1997. Depletion of intracellular calcium stores activates smooth muscle cell calcium-independent phospholipase A2. A novel mechanism underlying arachidonic acid mobilization. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 1522–1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park K. M., Trucillo M., Serban N., Cohen R. A., Bolotina V. M. 2008. Role of iPLA2 and store-operated channels in agonist-induced Ca2+ influx and constriction in cerebral, mesenteric, and carotid arteries. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 294: H1183–H1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singaravelu K., Lohr C., Deitmer J. W. 2006. Regulation of store-operated calcium entry by calcium-independent phospholipase A2 in rat cerebellar astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 26: 9579–9592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chang Y. C., Kim H. W., Rapoport S. I., Rao J. S. 2008. Chronic NMDA administration increases neuroinflammatory markers in rat frontal cortex: cross-talk between excitotoxicity and neuroinflammation. Neurochem. Res. 33: 2318–2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee H. J., Rao J. S., Chang L., Rapoport S. I., Bazinet R. P. 2008. Chronic N-methyl-D-aspartate administration increases the turnover of arachidonic acid within brain phospholipids of the unanesthetized rat. J. Lipid Res. 49: 162–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bosetti F. 2007. Arachidonic acid metabolism in brain physiology and pathology: lessons from genetically altered mouse models. J. Neurochem. 102: 577–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Contreras M. A., Rapoport S. I. 2002. Recent studies on interactions between n-3 and n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids in brain and other tissues. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 13: 267–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rao J. S., Harry G. J., Rapoport S. I., Kim H. W. 2010. Increased excitotoxicity and neuroinflammatory markers in postmortem frontal cortex from bipolar disorder patients. Mol. Psychiatry. 15: 384–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun G. Y., Xu J., Jensen M. D., Simonyi A. 2004. Phospholipase A2 in the central nervous system: implications for neurodegenerative diseases. J. Lipid Res. 45: 205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Greenamyre J. T., Maragos W. F., Albin R. L., Penney J. B., Young A. B. 1988. Glutamate transmission and toxicity in Alzheimer's disease. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 12: 421–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim H. Y., Rapoport S. I., Rao J. S. Altered arachidonic acid cascade enzymes in postmortem brain from bipolar disorder patients. Mol. Psychiatry. Epub ahead of print. December 29, 2009; doi:10.1038/mp.2009.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]