Abstract

This study was undertaken with several specific objectives: to evaluate the role of preformed heterospecific antibodies in causing hyperacute rejection of whole organs transplanted from dogs to pigs or pigs to dogs; to see how much this abrupt rejection could be mitigated by the antibody depletion that occurs with the use of successive organs; to establish the contribution of coagulation changes to the pathogenesis of this kind of hyperacute rejection; and to determine if there were similarities between abrupt heterograft rejection and hyperacute rejection of homografts in presensitized recipients.

Methods

All procedures were performed under sodium pentobarbital anesthesia. In each experiment, a series of control observations were made on one of the kidneys of the donor after its transplantation to the neck of an unmodified recipient, anastomosing the renal artery to the proximal carotid artery end-to-end and the end of the renal vein to the side of the external jugular vein. Kidney rejection was judged by the gross appearance, the cessation of urine excretion from the transplant and the loss of the blood supply of the heterograft as manifested by failure of its cut surface to bleed.

The other kidney from the same donor was also transplanted to the neck under conditions which were variable but which had in common the fact that the recipient was always modified by a preceding heterotransplantation. Examples included placement of the second kidney in the same animal that had been given the first one, and transplantation of the second kidney to another animal that had received a preliminary “conditioning” spleen or liver. The spleens were transplanted to the neck by a technique similar to that described above for the kidney. In about half the cases of initial hepatic transplantation, the livers were placed in the cervical region using only an arterial inflow and with the outflow passing through the suprahepatic vena cava into the external jugular system.1 In the other half, the auxiliary livers were placed intra-abdominally by the method of Welch.2 With the latter technique, the hetero-grafts received a double blood supply, the portal fraction being derived from the systemic venous blood returning from the recipient hind quarters.

Immunologic studies were performed on many of the recipient sera. Using the appropriate donor target cells, preformed antidonor hemagglutinins, leukoagglutinins,3 and lymphocytotoxins4 were measured. In addition antirenal and antihepatic activity was tested with a passive hemagglutination method5 in which sonicated liver or kidney extract was used to first coat type O human red cells to form a complex antigen. Whole complement was also quantitated in many experiments.6 The described tests often were performed on venous blood leaving the heterografts as well as on arterial blood, making it possible to establish A-V gradients.

Studies of formed blood elements, clotting tests, and assays of graft arterial and venous blood were performed by methods previously reported from our laboratories:7,8 (1) euglobulin lysis time, (2) thrombin time, (3) prothrombin time. (4) partial thromboplastin time with kaolin, (5) fibrinogen, (6) prothrombin (II), (7) Ac-globulin (V), (8) antihemophilic globulin (VIII) (9), (9) plasma thromboplastin component (IX), and (10) fibrin split products. Whole blood clotting times were measured at 37°C in new uncoated and also in silicone coated glass tubes. The experiments were divided as follows:

Group 1: Pig-to-Dog Heterotransplantation

-

(a)

Renal-renal (seven experiments). Kidneys from the same donor were successfully placed, leaving the first organ attached for an average of 171 minutes (range 77 to 198) before revascularization of the second one.

-

(b)

Renal-renal with heparinization (two experiments). One pig kidney was transplanted to an unmodified dog and the contralateral organ was given to another recipient 5 to 10 minutes after the intravenous injection of 5 mg./Kg. heparin.

-

(c)

Splenic-renal (six experiments). One donor kidney was transplanted to an unmodified recipient. The second kidney was revascularized in another dog 64 to 160 minutes after the spleen from the same donor had been transplanted.

-

(d)

Hepatic-renal (six experiments). Same as 1c except that the liver was the screening organ for 97 to 139 minutes.

-

(e)

Special studies. Arteriovenous gradients of antibodies, formed blood elements and coagulation parameters were obtained across six renal heterografts that were revascularized in unmodified recipients, and across nine more kidneys that were placed after prior exposure of the recipient to donor kidney (three examples), spleen (two examples), and liver (four examples). When the spleen and liver were used as the screening organs in six of the foregoing experiments, the same arteriovenous determinations were obtained across them as in the control or test kidneys.

Group 2: Dog-to-Pig Heterotransplantation

-

(a)

Renal-renal (six experiments). Analogous to Group 1a with first kidney left on for 150 minutes average (93–219).

-

(b)

Renal-renal with heparinization (two experiments). Analogous to Group 1b.

-

(c)

Renal-renal (five experiments). Same as Group 2a except that the screening kidney was taken from a third dog and left in for 60 to 237 minutes (average 181). The donor of the second renal heterograft also provided a kidney for control transplantation to unmodified recipient.

-

(d)

Splenic-renal (six experiments). Analogous to Group 1c.

-

(e)

Hepatic-renal (four experiments). Analogous to Group Id.

-

(f)

Special studies. Analogous to Group 1e. Arteriovenous gradients were obtained across three renal heterografts that were revascularized in unmodified recipients and across three more kidneys that were placed after first screening with a kidney, a spleen, or a liver. The same A-V gradients were also obtained across the spleen and liver when these organs were used for conditioning.

At cessation of heterograft function in almost all reported animals, routine histologic examinations from formalin fixed tissue were done on hematoxylin and eosin and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stained sections. In addition serial biopsies were obtained from one to 70 minutes after revascularization in selected experiments. A portion of the specimens was examined as described above. The rest was snap frozen and studied by direct immunofluorescence.10 Following absorption to eliminate cross reacting antibodies, fluorescin conjugated rabbit antidog or pig IgG, C3 or fibrin antisera were used with appropriate controls as has been previously described.11 Included for special study were eight pig-to-dog renal hetero-grafts (five primary organs and three secondary ones) and 10 dog-to-pig heterografts (five primary and five secondary). The same observations were made in a single spleen and liver heterograft from each species combination.

Results

Organ Survival and Function

Pig-to-dog transplantation

All 19 pig kidneys transplanted to unmodified canine recipients were destroyed in 2 to 20 minutes (mean 9.8 ± 1.1 SE). The severity of this hyperacute rejection was often mitigated by the prior transplantation of another organ from the same donor. For example, when two consecutive kidneys were given (Group 1a), the second kidney outlasted the first one in all six experiments (Fig. 1). The protected organs in two of these experiments remained viable for 32 and 68 minutes and in one instance the kidney produced more than 90 ml. of urine. The average urine output for these six second kidneys was 27 ± 12.8 (SE) ml. compared to 3 ± 0.6 (SE) ml. for the first renal grafts.

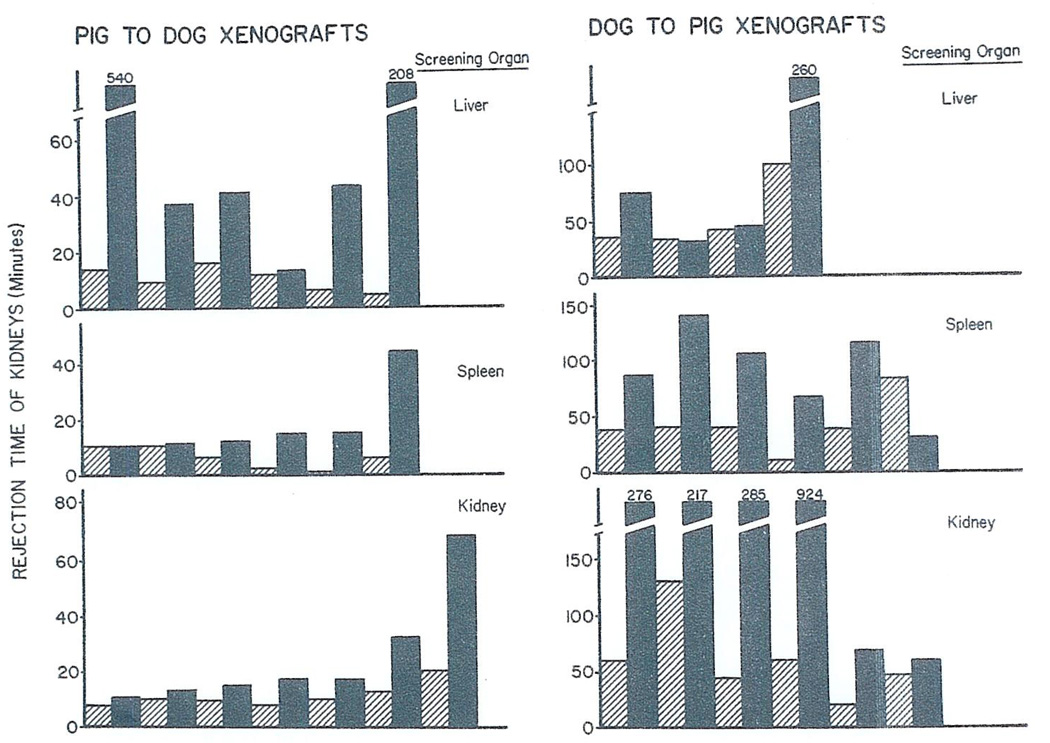

Fig. 1.

Rejection times of renal heterografts after transplantation to unmodified recipients (light shading) or after transplantation to animals that had already received a prior kidney, liver or spleen from same donor (black shading). For each experiment, result of control is just to left of that with definitive experiment.

In nine of the other 12 experiments in which the test recipients were conditioned by the initial revascularization of six spleens (Group 1c) or six livers (Group 1d) the subsequently transplanted kidneys remained alive for at least twice as long as the contralateral kidneys which were inserted into unmodified animals (Fig. 1). The control kidney did not survive longer than the protected organ in any instance. The best screening organ appeared to be the liver with survival and function of two of the subsequently transplanted kidneys for 3 and 9 hours, respectively. These two protected renal heterografts elaborated total urine volumes of 208 and 600 ml, respectively.

In the two experiments of Group 1b, total body heparinization afforded no protection from hyperacute rejection.

Dog-to-pig heterotransplantation

The 16 dog kidneys transplanted to unmodified pigs (light shading, Fig. 1) were rejected after 10 to 130 minutes (mean 50.6 ± 7.6 SE). The urine output of the organs was only 1.3 ± 0.4 (SE) ml. Both the urine output and time of viability (Fig. 1) were usually prolonged if the definitive kidney-transplant was preceded by one of the screening organs from the same donor. The best conditioning organ was the kidney (Group 2a) inasmuch as it prolonged survival and urine excretion by more than five and 20 times, respectively. There appeared to be individual specificity of the protective effect of a conditioning kidney. Thus, in five experiments in which the screening organ was a kidney from a third (or indifferent) dog (Group 2c) there was very little prolongation of the viability of the subsequent test renal graft and only a small increase in the amount of urine excreted (Table 1).

Table 1.

Dog-to-Pig Renal Heterotransplantation☼

| SCREENING KIDNEY | PROTECTED KIDNEY | CONTROL KIDNEY | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment Number | Rejection (Min.) | Urine Output (ml.) | Urine Flow Time (Min.) | Rejection (Min.) | Urine Output (ml.) | Urine Flow Time (Min.) | Rejection (Min.) | Urine Output (ml.) | Urine Flow Time (Min.) |

| 1 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 60 | 1.0 | 35 | 55 | 0.5 | 30 |

| 2 | 150 | 2 | 120 | 70 | 1.5 | 42 | 60 | 0.5 | 22 |

| 3 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0.5 | 10 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 44 | 1.5 | 36 | 46 | 9 | 40 | 33 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 97 | 3.5 | 84 | 60 | 0.5 | 55 | 53 | 1.0 | 50 |

Use of preliminary kidney from third-party donor (Group 2c). Note that this kind of screening organ offered essentially no protection for a subsequent renal heterograft in contrast to the results shown in Fig. 1.

There was also prolongation of kidney heterografts by prior transplantation of the spleen (Group 2d) or liver (Group 2e) from the renal donor but this was a less striking finding than described above for the kidney-kidney combination (Fig. 1). With the spleen as a conditioner (Fig. 1) the test kidneys lived longer than in the controls in five of six experiments with a maximum survival of 141 minutes. It proved to be difficult to use the liver as a screening organ. Revascularization of the canine hepatic graft caused the pigs to go into shock and die within 30 minutes in about half the cases. Because of this difficulty only four of the hepatic experiments could be completed. In three of the four, the protected kidneys functioned for longer (maximum 260 minutes) than in the controls (maximum 100 minutes).

The administration of systemic heparin (Group 2b) was without effect upon the rapidity of rejection in unmodified recipients

Immunologic Studies

Pig-to-dog heterotransplantation

Sera prepared from arterial blood were available from 31 dogs before and after heterotransplantation. All preoperative sera contained activity against donor red and white cells and against homogenates of pig kidney and liver. The titers of these preformed hetero-specific antibodies varied from dog to dog by as much as eight tubes. After revascularization of the kidney, spleen, or liver there were reductions of the antibodies in 70 per cent of experiments (Fig. 2). However, only the leukoagglutinins were ever completely cleared from the circulation and then only on four occasions. Although hemagglutinin and lymphocytotoxicity titers fell in 23 and 19, respectively, of the 31 series of determinations, these never completely disappeared. The reductions in lymphocytotoxins were usually temporary with the titers often promptly rising again within an hour or so to exceed the starting values. It was of interest that the antirenal and antihepatic antibodies demonstrated by the passive hemagglutination tests were not preferentially absorbed by the kidney or liver. Instead, these antibodies were about equally well depleted by all three kinds of conditioning organs (Fig. 2).

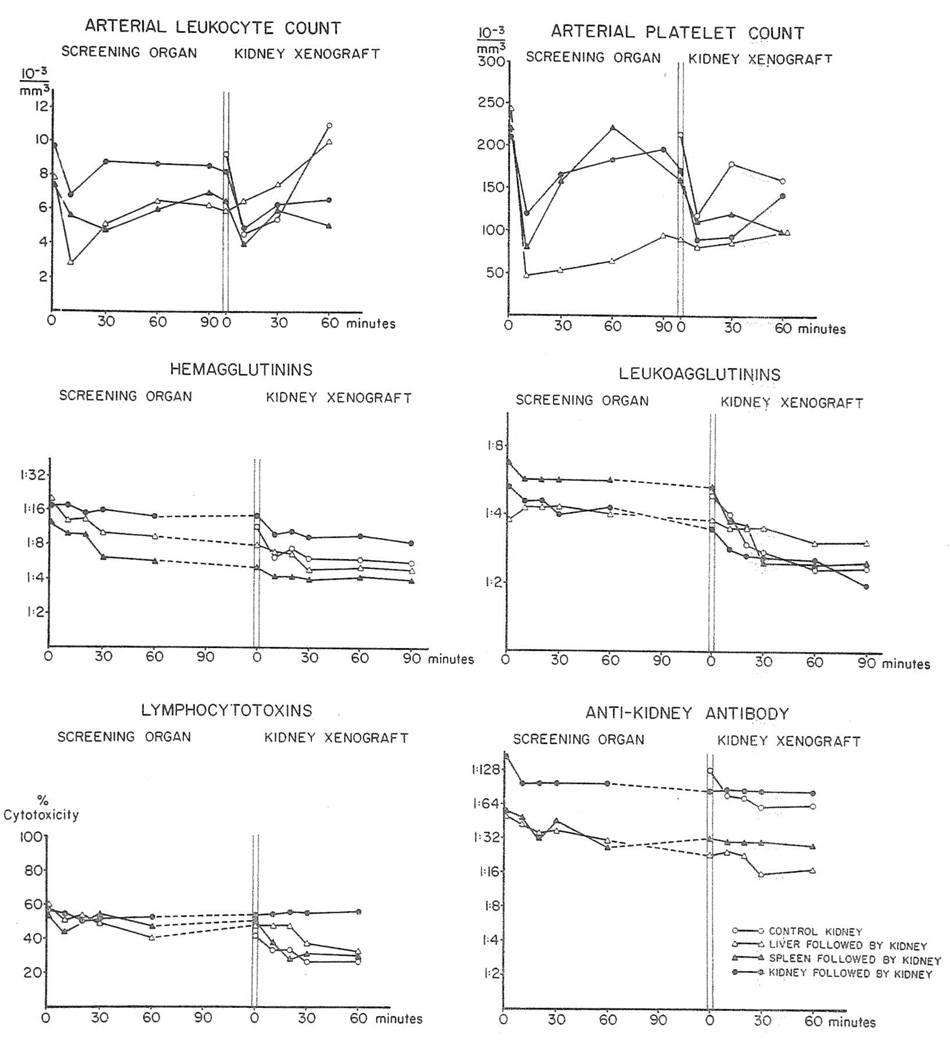

Fig. 2.

Pig-to-dog heterotransplantation. Average concentrations of white cells, platelets and antibodies in arterial blood of 31 dogs before and after heterotransplantation of one or more porcine organs.

When a renal heterograft was transplanted after rejection of a screening kidney, spleen, or liver, further decreases in antibodies occurred (Fig. 2) although as with the first exposure to a donor organ, the declines were modest.

Evidence that the systemic falls in antibodies were due to absorption by the heterografts was provided by the determination of arteriovenous gradients. In experiments in which nine kidneys, four livers, and two spleens were placed as the primary organ, there were falls across these organs in all the measured antibodies as well as whole complement (Table 2); the most complete removal seemed to be of the leukoagglutinins. In every experiment the largest gradients were within one to 3 minutes after the revascularization of the organ and these maximum changes are the ones shown in Table 2. By the time nine kidneys were then placed as second organs, there had usually been some restoration of antibody titers and complement toward the preexisting levels. With revascularization of these “protected” kidneys there were secondary falls similar to those initially observed. The rejection time of either a first or second kidney was not related to any of the antibody titers present at the time of the organ arrival.

Table 2.

Average Titers of Antibodies and Complements in Blood Entering and Leaving Porcine and Canine Heterografts

| Hemagglutinins | Leukoagglutinins | Lymphocytotoxins | Antikidney Antibod | Whole Complement | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organ☼ | Artery | Vein | Artery | Vein | Artery | vein | Artery | Vein | Artery | Vein |

| (% Dead Cells) | H50 units/ml. | |||||||||

| Pig-to-Dog | ||||||||||

| Primary | ||||||||||

| kidney (6) | 1:64 | 1:32 | 1:8 | 0 | 72 | 20 | 1:64 | 1:32 | 30 | 10 |

| Liver (4) | 1:8 | 1:4 | 1:8 | 1:2 | 55 | 31 | 1:64 | 1:32 | 35 | 18 |

| Spleen (2) | 1:8 | 1:4 | 1:4 | 0 | 51 | 30 | 1:128 | 1:64 | 28 | 16 |

| Secondary | ||||||||||

| kidney (9) | 1:16 | 1:8 | 1:4 | 1:4 | 60 | 26 | 1:64 | 1:32 | 25 | 11 |

| Dog-to-Pig | ||||||||||

| Primary | ||||||||||

| kidney (3) | 1:8 | 1:4 | 0 | 0 | – | – | 1:32 | 1:16 | 23 | 17 |

| Liver (1) | 1:8 | 1:4 | 1:4 | 0 | – | – | 1:8 | 1:4 | 20 | 10 |

| Spleen (1) | 1:16 | 1:8 | 1:16 | 1:4 | – | – | 1:64 | 1:64 | 17 | 5 |

| Secondary | ||||||||||

| kidney (3) | 1:8 | 1:4 | 1:2 | 0 | – | – | 1:16 | 1:16 | 17 | 12 |

Numbers in parentheses indicate number of grafts.

Dog-to-pig heterotransplantation

Satisfactory examinations of systemic blood were made in 29 experiments. All of the porcine sera had hemagglutinins against donor red cells and also reacted against the canine kidney homogenate. Fourteen of the 29 pigs had preformed antidonor leukoag-glutinins but none of the 29 recipients had preformed antidonor lymphocytotoxins.

After revascularization of the conditioning organs or of the “protected” renal heterografts, the various preformed antibodies in arterial blood fell in essentially the same way (Fig. 3) as was described earlier for the pig to dog heterotransplantations. The rapidity of rejection was not correlated with the presence or absence of preformed leuko-agglutinins. In five special experiments (Table 2) arteriovenous gradients of the antibodies as well as the whole complement were demonstrated across the heterografts although the declines were very small and not always present.

Fig. 3.

Dog-to-pig heterotransplantation. Average concentrations of white cells, platelets, and antibodies in arterial blood of 29 pigs before and after heterotransplantation of one or more canine organs.

Hematologic Studies

Pig-to-dog heterotransplantation

There were 19 kidneys, six spleens, and six livers that were placed as primary heterografts. All three organs caused pronounced leukopenia and thrombocytopenia which were usually most severe within the first 10 minutes (Fig. 2). Subsequently, as the organs underwent hyperacute rejection the white blood cell and platelet counts slowly rose. This recovery was least with the liver and most complete with the kidney. With the latter organ the platelet and white cell counts often rose to above the starting levels by the end of 90 minutes. There were no major coincident changes in the red blood cell counts.

The transplantation of the test kidney after 90 minutes tended to arrest the recovery phase of the white cells and thrombocytes or to cause a significant although transient secondary depression (Fig. 2). Again the red blood cell counts were essentially unchanged. Arteriovenous gradients of formed blood elements which were measured across heterografts in the special group of nine experiments (Group 1e) will be described under a later section on coagulation.

Dog-to-pig heterotransplantation

Sixteen kidneys, six spleens, and four livers were transplanted as first organs. The consequences upon the formed elements in arterial blood were similar to, though somewhat more slowly developing and less drastic (Fig. 3), than with pig-to-dog transfers. The platelet and white blood cell depressions had partly returned toward normal by the time of the 16 test renal heterografts but then declined again with the second organ (Fig. 3).

Coagulation Studies and Hematologic Corrections

Pig-to-dog heterotransplantation (Group 1e)

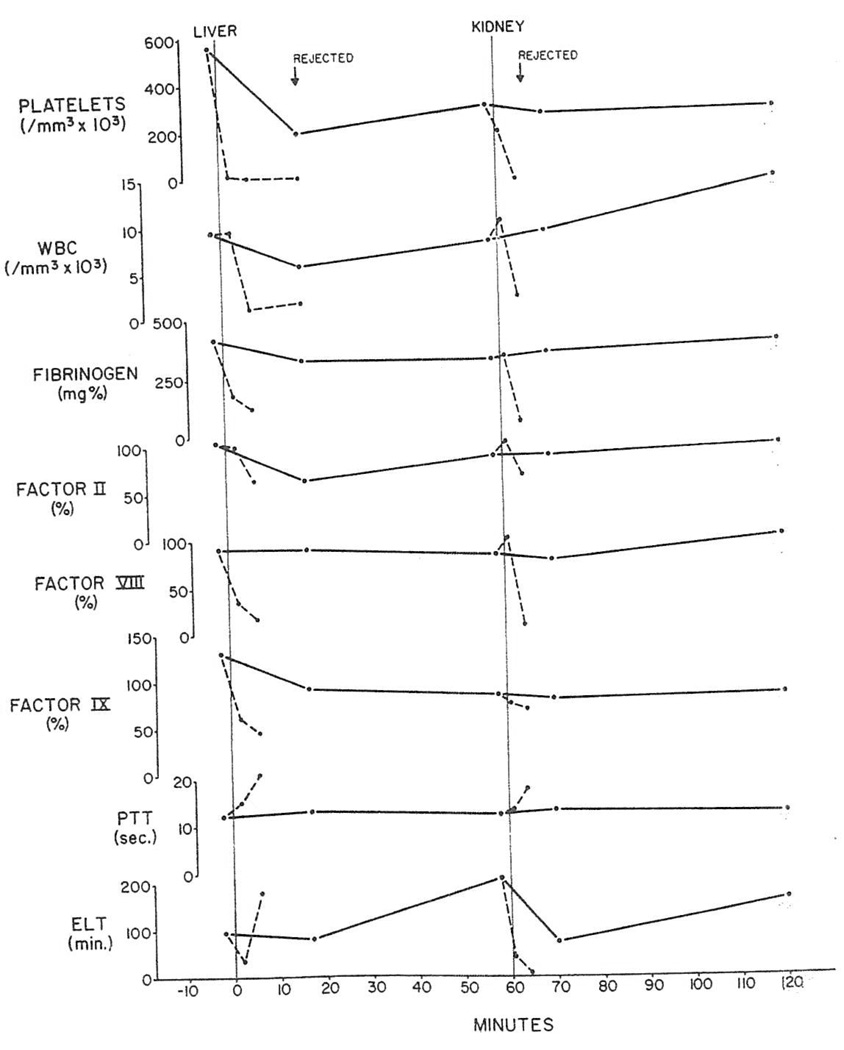

Arteriovenous gradients were measured across six primary renal heterografts. Within 30 seconds after revascularization, the hematocrit between the arterial and venous sides rose from 39 to 49 per cent indicating hemoconcentration. In the same brief interval, striking entrappment of the platelets occurred so that 60 per cent of the thrombocytes that entered the kidney failed to leave it. There was an abrupt A-V decline in euglobulin lysis time (ELT) connoting intrarenal activation of fibrinolysis. Later the sequestration of platelets increased until 95 per cent or more of the thrombocytes were estimated to be removed in a single passage after 2 or 3 minutes. The hemato-crit fell to an average of 31 per cent as if hemodilution had occurred or alternatively as if the red cells had been removed. These data are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Average Values of Leukocytes, Platelets, Clotting Factors and Euglobulin Lysis Times in Blood Entering and Leaving Porcine and Canine Heterografts, Demonstrating Maximum Arteriovenous Gradients

| Organ☼ | Platelets 103/mm.3 |

Leukocytes 103/mm.3 |

Fibrinogen mg. Per Cent |

Factor II Per Cent |

Factor V Per Cent |

Factor VIII Per Cent |

Factor IX Per Cent |

Euglobulin Lysis Time (Min.) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artery | Vein | Artery | Vein | Artery | Vein | Artery | Vein | Artery | Vein | Artery | Vein | Artery | Vein | Artery | Vein | |

| Pig-to-Dog | ||||||||||||||||

| Primary kidney (6) | 262 | 32 | 5.2 | 3.6 | 330 | 212 | 90 | 60 | 105 | 76 | 79 | 22 | 83 | 57 | 61 | 26 |

| Liver (4) | 373 | 12 | 8.0 | 1.7 | 391 | 144 | 81 | 44 | 113 | 57 | 81 | 24 | 132 | 46 | 94 | 36 |

| Spleen (2) | 195 | 2 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 481 | 389 | 90 | 78 | 103 | 86 | – | – | 127 | 100 | – | – |

| Secondary kidney (9) | 233 | 20 | 7.5 | 2.0 | 284 | 157 | 70 | 46 | 74 | 45 | 64 | 32 | 74 | 53 | 130 | 30 |

| Dog-to-Pig | ||||||||||||||||

| Primary kidney (3) | 518 | 418 | 12.0 | 6.2 | 533 | 371 | 36 | 35 | 89 | 86 | 120 | 96 | 43 | 64 | 747 | 312 |

| Liver (1) | 415 | 35 | 12.6 | 1.7 | 306 | 249 | 50 | 38 | 84 | 46 | 68 | 44 | 64 | 34 | 855 | 27 |

| Spleen (1) | 605 | 130 | 13.3 | 5.6 | 340 | 296 | 70 | 50 | 100 | 76 | 116 | 96 | 62 | 72 | 1080 | 1140 |

| Secondary kidney (3) | 371 | 279 | 20.8 | 11.2 | 389 | 290 | 45 | 39 | 76 | 73 | 74 | 62 | 55 | 77 | 431 | 389 |

Numbers in parentheses indicate number of grafts.

Within a minute after revascularization of the kidneys, and following the first changes in platelets and ELT by about 30 seconds, other evidence of consumption became measurable. The white cells in the renal venous effluent dropped to a third or less of the concentration in the renal artery. About 1 minute after the white cell entrappment became detectable, clotting factors I, II, V, VIII, and IX all developed significant arteriovenous gradients which were usually maximal at 3 to 6 minutes (Table 3). There were also concomittant increases in the thrombin, prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times. This evidence of coagulation within the transplants correlated well with the grossly visible evidence of rejection.

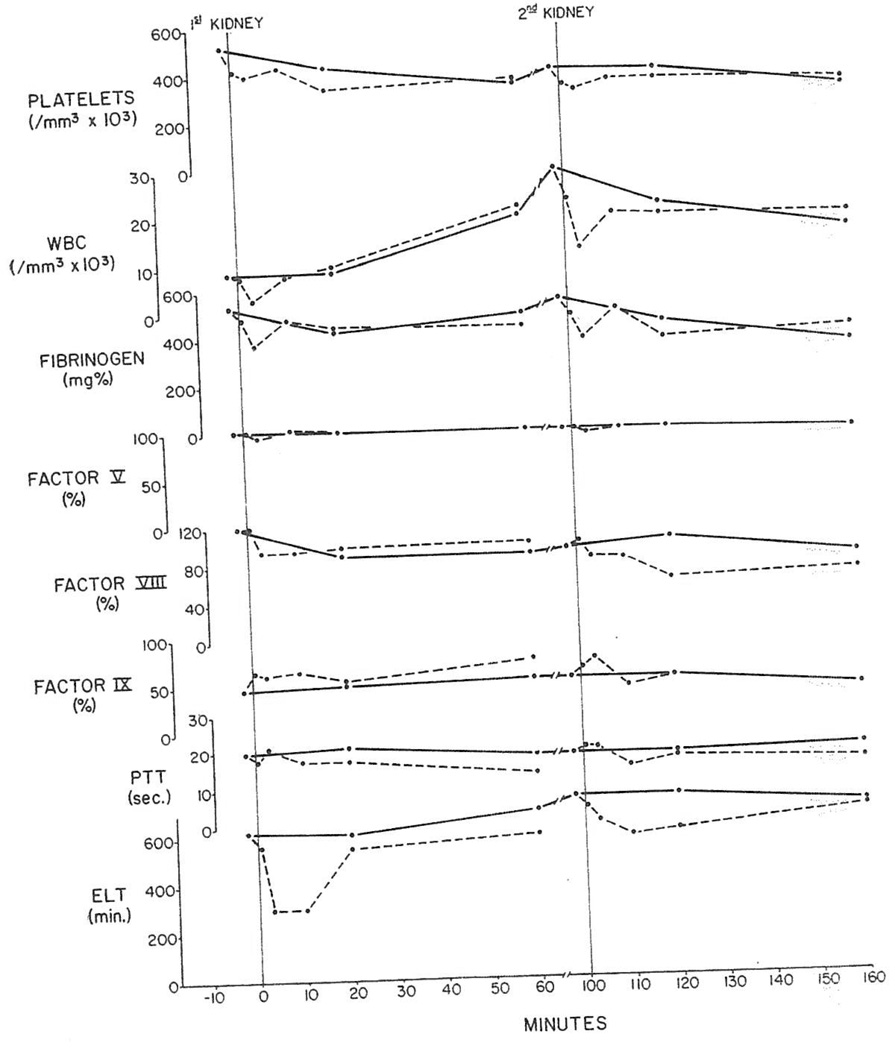

In principle, the findings were the same after revascularization of livers (Fig. 4) although the degree of consumption was greater (Table 3). Two spleens that were used as conditioning organs had the same kind of clearance of platelets and white cells (Table 3) but were rejected so rapidly that studies of the clotting factors were not feasible.

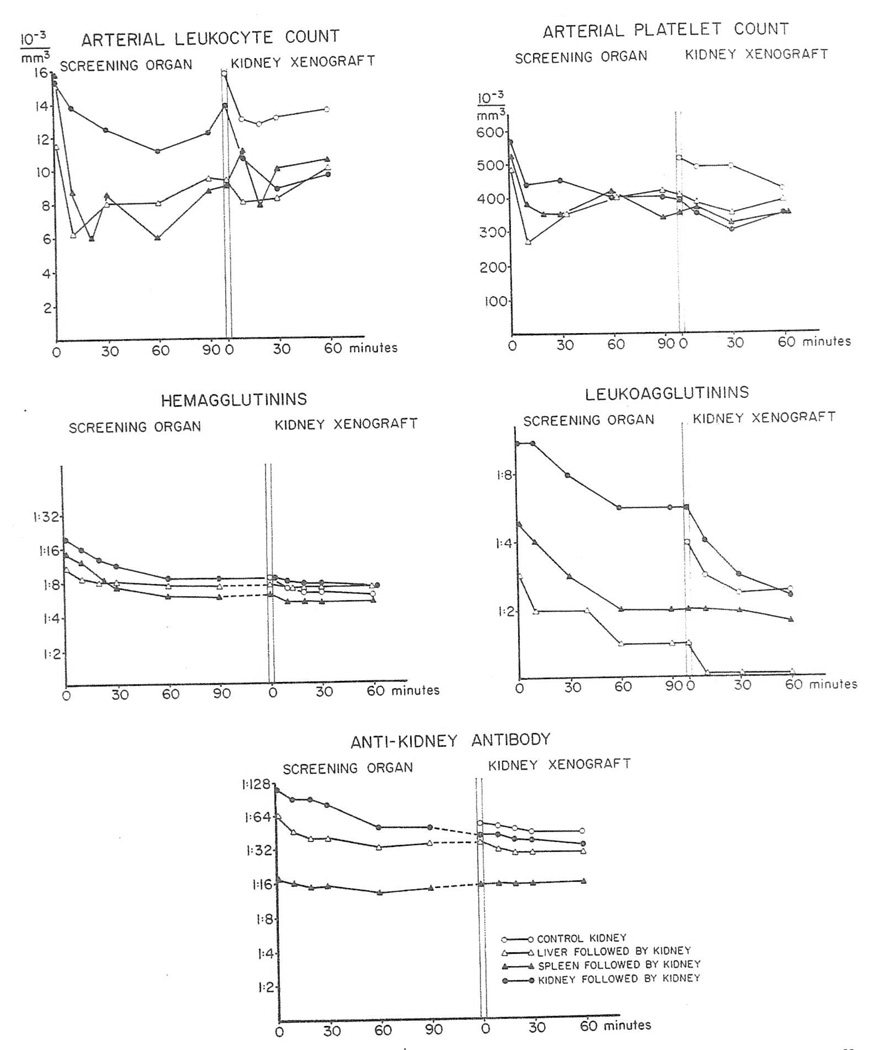

Fig. 4.

Pig-to-dog heterotransplantation. Arteriovenous gradients of platelets, white cells and clotting parameters across liver and subsequently transplanted kidney from same donor. PTT: partial thromboplastin time; ELT: euglobulin lysis time; solid lines: arterial values; broken lines: results in heterograft venous blood.

The changes in nine renal heterografts placed secondarily after prior transplantation of a kidney, liver, or spleen were not strikingly different from those seen with first kidneys (Fig. 4 and Table 3).

With both the first and second hetero-transplantations, changes in the arterial blood reflected in a general way the degree to which clotting factors, platelets, and white cells were entrapped. When significant systemic alterations occurred, they were usually maximal after 10 to 15 minutes and except when the liver was used the changes returned to normal or above within 60 minutes.

Dog-to-pig heterotransplantation

The arteriovenous gradients of formed blood elements and clotting factors described above for pig-to-dog renal heterotransplantation were also observed after dog-to-pig transfers but to a lesser degree (Table 3) for both primary and “protected” kidneys. In particular, the platelet entrappment, which was the most prominent feature after pig-to-dog renal transplantation, was barely identifiable when the grafting was in the other direction (Fig. 5). Arteriovenous gradients were also significant of the white cells, ELT and the clotting factors I (fibrinogen) and VIII (Fig. 5). However, clotting factors II and V were not altered and there was actually an enhanced factor IX activity in the renal venous effluent (Fig. 5). Partial thromboplastin time (PPT) in the renal venous blood was often shortened (Fig. 5). Small amounts of fibrin split products (5–10 mg.%) were found in some venous samples.

Fig. 5.

Dog-to-pig heterotransplantation. Arteriovenous gradients of platelets, white cells and clotting parameters across two kidneys sequentially transplanted from same donor. Solid and broken lines indicate arterial and venous blood, respectively. Abbreviations same as Fig. 4.

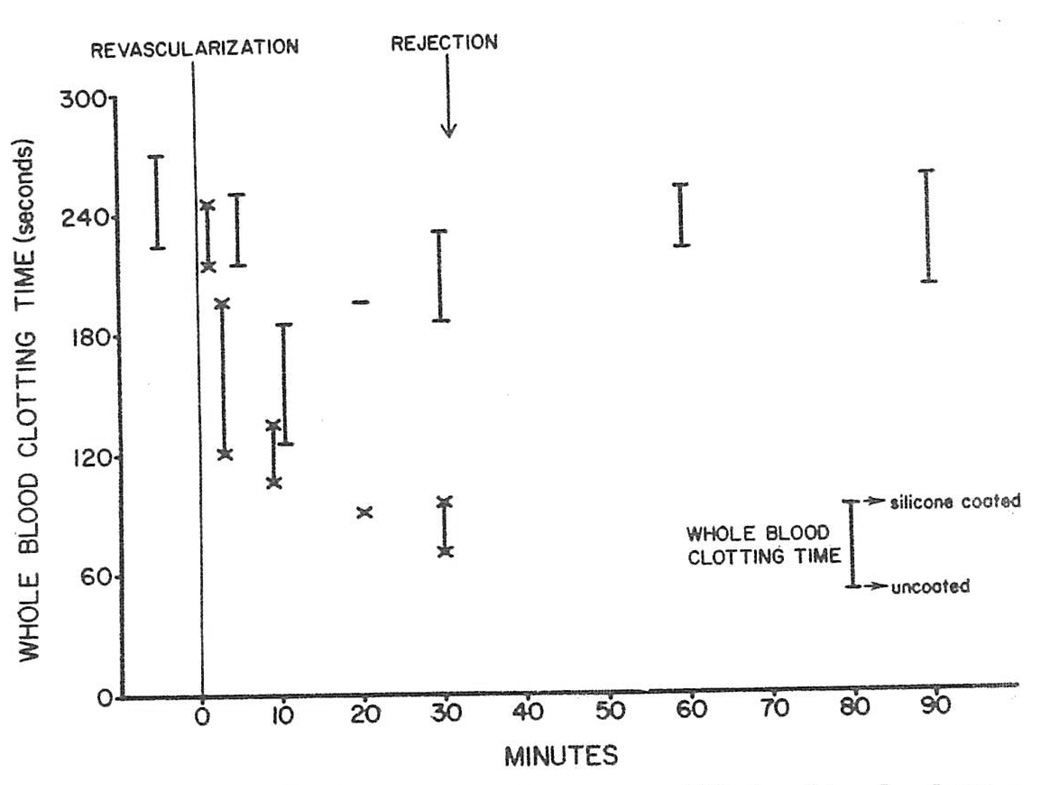

Because of the positive gradient of factor IX, clotting times of the heterograft arterial and venous blood were compared when determined in siliconized and non-siliconized test tubes to see if contact activation had occurred within the transplant as the initial event of the coagulation process. Within a few minutes of revascularization, the clotting times of the renal venous blood shortened 50 per cent but the reduction was proportionate in the two kinds of test tubes (Fig. 6). The latter observation indicated that the shortening of the clotting times was triggered by some means other than contact activation intrarenally.

Fig. 6.

Dog-to-pig renal heterotransplantation. Whole blood clotting times in heterotransplantation experiment. At each interval, clotting time in siliconized test tube (upper extent of bar) is compared to that in nonsiliconized test tube (lower extent of bar). For arterial determinations, cross bars are straight: for venous, crossed. Clotting times changed in course of experiment, particularly in venous blood, but alterations tended to be proportionate using siliconized versus nonsiliconized test tubes. Findings were interpreted as evidence against intrarenal contact activation.

With both the liver and spleen (Table 3) the sequestration of platelets and white cells was more marked than with the kidney. Clotting factors I, II, V, and VIII were all consumed. After hepatic transplantation even the activity of factor IX in the heterograft venous blood was reduced although with splenic transplantation a positive gradient of factor IX was noted as was described above for kidneys.

Pathologic Studies

Pig-to-dog heterotransplantation

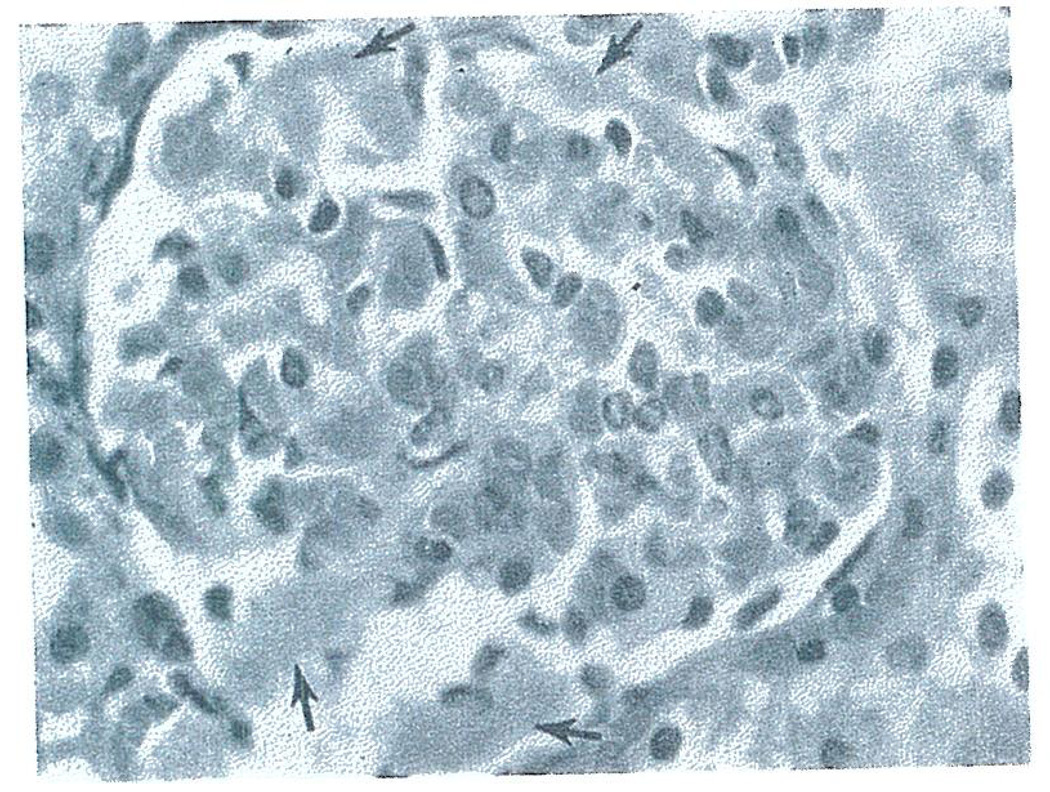

Histo-logic studies of the rejecting primary renal heterografts revealed moderate to severe engorgement of glomerular (Fig. 7) and peritubular capillaries with circulating blood elements and small amounts of eosinophilic material suggesting early thrombus formation. Similar engorgement of hepatic sinusoids and splenic pulp was also seen in the liver and spleen grafts.

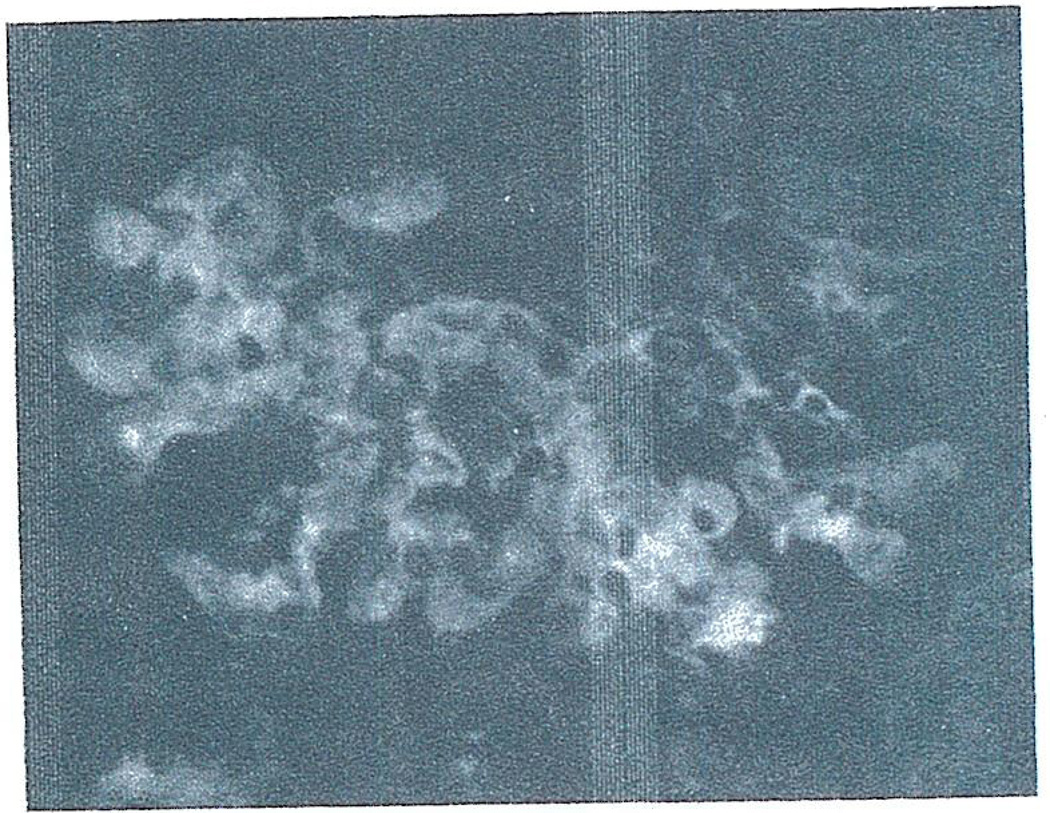

Fig. 7.

Glomerulus from pig-to-dog renal heterograft at 20 minutes showing engorgement of glomerular capillaries and areas of eosinophilic material (arrows) suggesting thrombus formation. Hematoxylin and eosin. × 400.

Immunofluorescence examination of the serial kidney biopsies showed fibrin accumulation beginning at 3 minutes and becoming maximum (3–4+ on a 4+ scale) at 10 to 20 minutes. The fibrin filled the lumens of glomeruli and peritubular capillaries (Fig. 8). Dog IgG and C 3 were found in a similar pattern (Fig. 9) reaching a 1+ concentration by 20 minutes. The presence of albumin by immunofluorescence in the glomerular deposits in a pattern similar to IgG and C3 suggested that serum proteins were being trapped in the developing thrombi. Therefore, the immunologic specificity of the IgG and C3 deposits could not be assessed. No or minimal diffuse deposits of IgG, C3 and fibrin were present in the conditioning spleen and liver.

Fig. 8.

Fibrin deposits in capillaries of glomerulus and peritubular area of biopsy taken from pig-to-dog heterograft at 20 minutes. Stained with fluoresceinated rabbit anti-dog fibrin. × 400.

Fig. 9.

Dog IgG deposits in glomerular capillaries from same biopsy shown in Fig. 8. Pattern is same as for fibrin and probably represents entrappment of IgG in thrombus. Stained with fluoresceinated rabbit antidog IgG. × 400.

The various immunopathologic changes appear to evolve more rapidly in the primary as compared to the secondary renal heterografts, but the ultimate histologic picture was identical under both circumstances.

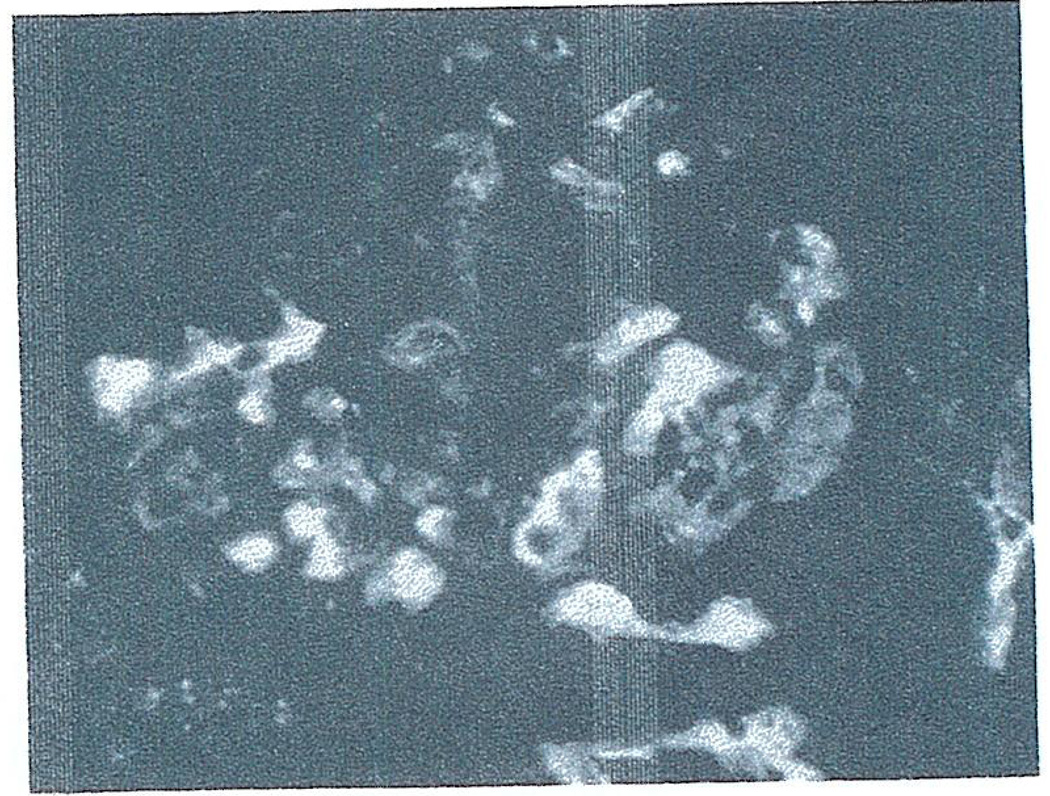

Dog-to-pig heterotransplantation

By light microscopy the kidney had less capillary congestion and engorgement than after pig-to-dog heterotransplantation. Within the first hour, a striking accumulation of poly-morphonuclear (PMN) leukocytes was seen in glomeruli (maximum 25–30 PMN/glomerulus) (Fig. 10). The sinusoids of hepatic heterografts had similar but somewhat less extensive findings.

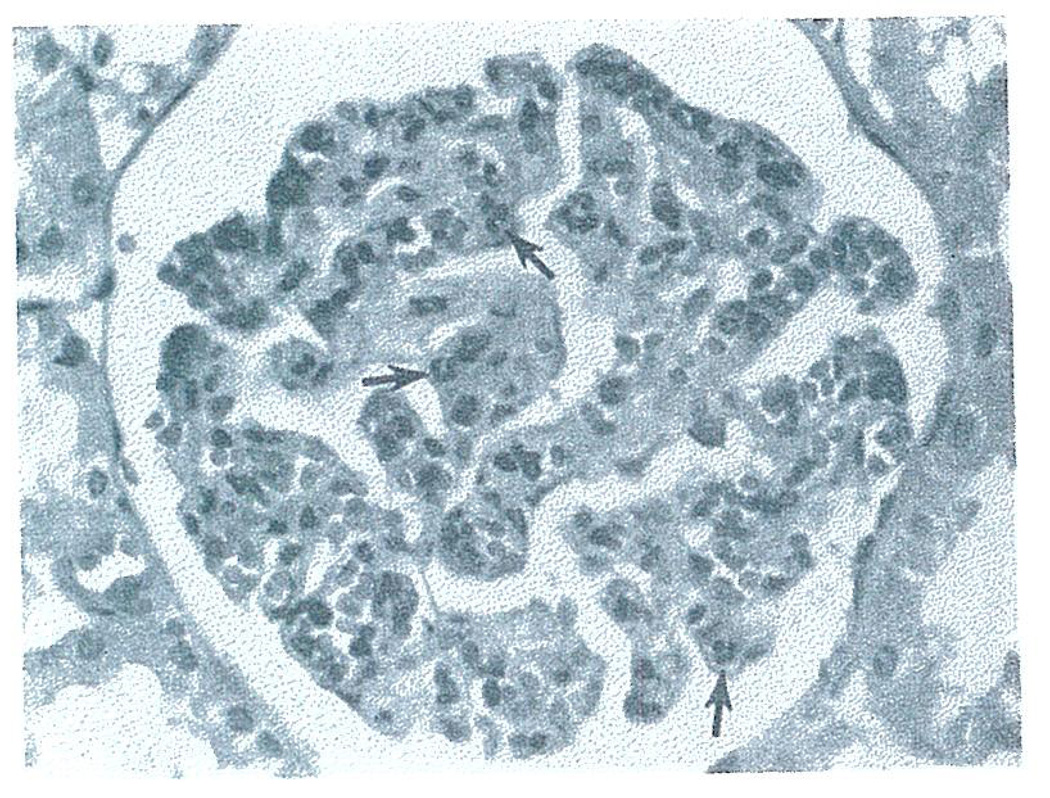

Fig. 10.

Glomerulus from dog-to-pig heterograft at 60 minutes showing polymorpho-nuclear (PMN) leukocyte infiltration (arrows) with no evidence of thrombus formation. Hematoxylin and eosin. × 400.

By immunofluorescence, the fibrin accumulation in the serial biopsies was less (2+ maximum) than after pig-to-dog heterotransplantation. The pattern was different in that the fibrin in large part appeared to surround the glomerular capillary loops being in Bowman’s space rather than confined to the glomerular capillary lumens. Fibrin deposits were also present in peritubular capillaries. Finely granular deposits of pig IgG and C3 were seen in the mesangial stalk region of the glomeruli reaching a maximum intensity of 1+ at 55–70 minutes following transplantation. The presence of these immunoreactants in the area of the peritubular capillaries was also noted. No specific deposits of pig IgG, C3 or fibrin were identified in the conditioning spleen or liver or in two native pig kidneys.

The findings were not perceptibly different in the primary as opposed to the secondarily transplanted renal heterografts.

Discussion

In recent years, it has been thought on the basis of indirect evidence that the violent rejection occurring after heterotransplantation between divergent species was due to the action of preformed heterospecific antibodies. Support for the hypothesis included the fact that antidonor antibodies of several kinds were often demonstrable by preoperative in vitro testing of the recipient animal’s serum,12,13 that such antibodies were cleared by organs transplanted from this donor,13,17 that the vascularization of successive kidneys from the same donor (or donors of the same species) usually prolonged the function of the last organ presumably by antibody depletion,15,17 and that physicochemical removal of immuno-globulins18 or the inactivation of complement16,19 in the recipient sometimes increased heterograft survival.

The concept of humoral antibody participation in hyperacute heterograft rejection has been further strengthened in the present study, although again by inference. First, most of the lines of evidence alluded to in the preceding paragraph were confirmed and extended in both the pig to dog and dog to pig models. Second, because of other studies in our laboratories7,8 it became possible to compare the events of hyperacute heterograft rejection to those which abruptly lead by unquestionably immunologic mechanisms to the destruction of homografts that are placed into recipients deliberately sensitized to donor tissue. The observations have been so similar in each circumstance that progress in ameliorating hyperacute rejection would be expected to be applicable to both situations.

Although it can be considered virtually established that hyperacutely rejecting homografts and heterografts are the site of an almost instantaneous antigen-antibody reaction, the actual quantities of immuno-globulins picked up by the new organs can be so small that antibody localization by immunofluorescence may be difficult or impossible. This was noted in the pig to dog heterotransplantations and it also has been seen in hyperacutely rejecting homografts.7,8,20 It has become clear7,8,20,21 that the final steps of hyperacute rejection are not necessarily due to the direct toxic action of the antibodies but that they are at least partly dependent upon an immunologically triggered intravascular coagulation and in turn upon plugging of the blood vessels with platelets and fibrin and by resulting devascularization of the foreign organ.

In both the heterotransplantation and presensitized homotransplantation preparations, a whole family of heterogenous anti-donor antibodies have been identified in the recipients and these lists are undoubtedly incomplete. There is still much to be learned about the interrelation between the immune reaction served by such antibodies and the subsequent clotting. For example, it is not known if there is a single special antibody in transplant models that is uniquely capable of altering coagulation. This does not seem likely since many antibodies can provoke clotting in a variety of nontransplantation experiments.22–25 It is also unlikely as has been discussed else-where7,8 that the sequence from an antigen-antibody union to intravascular coagulation is a simple or easily controlled one. It is worth noting that heparin had no easily detectable beneficial effects in terms of organ survival in our heterotransplantation experiments, although this kind of treatment has been reported to ameliorate hyperacute renal homograft rejection in specifically sensitized dogs.26

The coagulation changes seen in the two species combinations of the present study appeared to be different but the variations were probably largely quantitative. With the transfer of pig organs to the dog, there was always almost immediate sequestration of platelets within the graft, and “primary” fibrinolysis as indicated by shortened ELT of the renal venous blood. Then within a few minutes, white and red cells and ultimately clotting factors were cleared by the transplants. The fibrin in the heterografts examined by immunofluorescence was present within the lumens of capillaries in the glomeruli and peritubular areas.

In contrast, the consumption of platelets within kidney heterografts was not so great with the “easier” dog-to-pig combination. Intrarenal consumption of some clotting factors occurred along with evidence of fibrinolysis but the arteriovenous gradients of several other factors were not altered. Factor IX in the renal vein was actually increased presumably due to its activation within the organ. By immunofluorescence, the fibrin deposits were distinctly less. Much of the fibrin was outside the glomerular capillary lumens in Bowman’s space suggesting that the glomerular basement membrane had been promptly damaged.

In hyperacutely rejecting heterografts as well as in homografts undergoing a comparable kind of destruction, the most important and consistent coagulation changes appear to occur locally, this is within the vessels of the transplant, and probably by mechanisms that have been speculated upon elsewhere.7,8 In the heterograft experiments of the present study, a disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) was not encountered of the kind recently described in some presensitized canine8 and human7 recipients of renal homografts. The initiating event of the local clotting at least in the dog-to-pig heterotransplantations, did not appear to be contact activation in view of the results with the clotting times in siliconized versus nonsiliconized test tubes.27

In considering the mitigation of hyper-acute rejection that has been demonstrated by the successive revascularization of organs in homotransplantation8 and hetero-transplantation experiments, it is not yet possible to unequivocally subscribe to any special explanation. The sequestration of preformed antibodies by the first graft is one possibility. That immunoglobulins are in fact removed was suggested by the arteriovenous gradient data herein reported as well as by the immunofluorescence studies. However, the development of these antibody gradients was a far less reliable and striking finding than the gradients of clotting factors, platelets, and white cells. It could be argued that removal of the latter resources was responsible for the protective effect.

On the other hand, the immunologic specificity of the short term protection provided by an initial screening heterograft was supported by an unexpected observation in the present study. In dog-to-pig heterotransplantations, it was found necessary to use an initial organ from the eventual donor of the definitive kidney to achieve maximum prolongation of graft survival. Third-party organs were relatively ineffective suggesting the importance of antigenic differences between individuals of the canine species in determining the specificity and/or completeness of absorption of relevant preformed antibodies.

Summary

Immunologic, coagulation, hematologic, and immunopathologic studies were obtained before, during, and after whole organ transplantation from dogs to pigs or from pigs to dogs. The events and factors of the hyperacute rejection seen with this difficult species combination appeared to be similar to those after organ homotransplantation to presensitized recipients.

Acknowledgments

Supported by USPHS Grants AI-04152, AI-07007, AI-AM-08898, AM-12148, AM-06344, AM-07772, RR-00051, HE-09110, and RR-00069-and by USPHS Contract PH-43-68-621.

REFERENCES

- 1.Starzl TE, Marchioro TL, Faris TD, McCardle RJ, Iwasaki Y. Avenues of future research in homotransplantation of the liver: With particular reference to hepatic supportive procedures, antilymphocyte serum and tissue typing. Amer. J. Surg. 1966;112:391. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(66)90209-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Welch CS. A note on transplantation of the whole liver in dogs. Transplantation Bull. 1955;2:54. [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Rood JJ, van Leuwen A. Leucocyte grouping. A method and its application. J. Clin. Invest. 1963;42:1382. doi: 10.1172/JCI104822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Terasaki PI, McClelland JD. Micro-droplet assay of human serum cytotoxins. Nature. 1964;204:998. doi: 10.1038/204998b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gold ER, Fudenberg HH. Chromic chloride: A coupling reagent for passive hemag-glutination reactions. J. Immun. 1967;99:859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kabat GA, Mayer MM. Experimental Immunochemistry. ed. 2. Springfield, Ill: Charles C Thomas; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Starzl TE, Boehmig HJ, Amemiya H, Wilson CB, Dixon FJ, Giles GR, Simpson KM, Halgrimson CG. Clotting changes including disseminated intravascular coagulation during rapid renal homograft rejection. New Eng. J. Med. 1970;283:383. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197008202830801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simpson K, Bunch DL, Amemiya H, Boehmig HJ, Wilson CB, Dixon FJ, Coburg AJ, Hathaway WE, Giles GR, Starzl TE. Humoral antibodies and coagulation mechanisms in the accelerated or hyperacute rejection of renal homografts in sensitized canine recipients. Surgery. 1970;68:77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simone JV, Vanderheiden J, Abild-gaard CF. A semiautomatic one stage Factor VIII assay with a commercially prepared standard. J. Clin. Lab. Med. 1967;69:706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coons AH, Kaplan MH. Localization of antigen in tissue cells. II. Improvements in a method for the detection of antigen by means of fluorescent antibody. J. Exp. Med. 1950;91:1. doi: 10.1084/jem.91.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson CB, Dixon FJ. Antigen quantitation in experimental immune complex glomerulonephritis I. Acute serum sickness. J. Immun. (in press) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark DS, Gewurz H, Good RA, Varco RL. Complement fixation during homograft rejection. Surg. Forum. 1964;15:144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perper RJ, Najarian JS. Experimental renal heterotransplantation. Transplantation. 1966;4:377. doi: 10.1097/00007890-196607000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark DS, Gewurz H, Varco RL. Serologic studies on accelerated graft rejection. Fed. Proc. 1965;24:621. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark DS, Foker JE, Pickering R, Good RA, Varco RL. Evidence of two platelet populations in xenograft rejection. Surg. Forum. 1966;17:264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gewurz H, Clark DS, Finstad J, Kelley WD, Varco RL, Good RA, Gabrielson AG. Role of the complement system in graft rejections in experimental animals and man. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1966;129:673. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linn BS, Jensen JA, Portal P, Snyder GB. Renal xenograft prolongation by suppression of natural antibody. J. Surg. Res. 1968;8:211. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(68)90088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bier M, Beavers CD, Merriman WG, Merkel FK, Eiseman B, Starzl TE. Selective plasmaphoresis in dogs for delay of heterograft response. Trans. Amer. Soc. Artif. Intern. Organs. 1970;16:325. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snyder GB, Ballesteros E, Zarco RM, Linn BS. Prolongation of renal xenografts by complement suppression. Surg. Forum. 1966;17:478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Starzl TE, Lerner RA, Dixon FJ, Groth CG, Brettschneider L, Terasaki PI. The Shwartzman reaction after human renal transplantation. New Eng. J. Med. 1968;278:642. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196803212781202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenberg JC, Broersma RJ, Bullemer G, Mammen EF, Lenaghan R, Rosenberg BF. Relationship of platelets, blood coagulation and fibrinolysis to hyperacute rejection of renal xenografts. Transplantation. 1969;8:152. doi: 10.1097/00007890-196908000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robbins J, Stetson CA. An effect of antigen-antibody interaction on blood coagulation. J. Exp. Med. 1959;109:1. doi: 10.1084/jem.109.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robbins J, Stetson CA. Mechanisms of antigen-antibody reactions upon blood coagulation. Fed. Proc. 1959;18:594. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee L. Antigen-antibody reaction in the pathogenesis of bilateral renal cortical necrosis. J. Exp. Med. 1962;117:365. doi: 10.1084/jem.117.3.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bettex-Gallard M, Luescher EF, Simon G, Vasalli P. Induction of viscous metamorphosis in human blood platelets by means other than by thrombin. Nature (London) 1963;200:1109. doi: 10.1038/2001109a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDonald A, Busch GJ, Alexander JL, Phetepluce EA, Menzoian J, Murray JE. Heparin and aspirin in the treatment of hyperacute rejection of renal allografts in presensitized dogs. Transplantation. 1970;9:1. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197001000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas DP, Wessler S, Reimer SM. The reaction of factors XII, XI, and IX to hypercoagulable states. Thromb. Diath. Haemorrh. 1963;9:90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]