Abstract

Background

Patients with thyroid disease frequently complain of dysphagia. To date, there have been no prospective studies evaluating swallowing function before and after thyroid surgery. We used the swallowing quality of life (SWAL-QOL) validated outcomes assessment tool to measure changes in swallowing-related quality-of-life in patients undergoing thyroid surgery.

Methods

Patients undergoing thyroid surgery from May 2002 to December 2004 completed the SWAL-QOL questionnaire before and one year after surgery. Data were collected on demographic and clinicopathologic variables, and comparisons were made to determine the effect of surgery on patients’ perceptions of swallowing function.

Results

Of 146 eligible patients, 116 (79%) completed the study. The mean patient age was 49 years, and 81% were female. Sixty-four patients (55%) underwent total thyroidectomy and the remainder received thyroid lobectomy. Thirty patients (26%) had thyroid cancer. The most frequent benign thyroid conditions were multinodular goiter (28%) and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (27%). Mean pre-operative SWAL-QOL scores were below 90 for nine of the eleven domains, indicating the perception of impaired swallowing and imperfect quality of life. After surgery, significant improvements were seen in eight SWAL-QOL domains. Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury was associated with dramatic score decreases in multiple domains.

Conclusions

In patients with thyroid disease, uncomplicated thyroidectomy leads to significant improvements in many aspects of patient-reported swallowing-related quality-of-life measured by the SWAL-QOL instrument.

Keywords: SWAL-QOL, Quality-of-life, Dysphagia, Swallowing, Deglutition, Deglutition disorders, Thyroid Cancer, Goiter, Thyroid Surgery, Perioperative Complications, Recurrent Layngeal Nerve Injury, Patient-Reported Outcomes

Dysphagia, or difficulty in swallowing, is a common complaint, especially in older adults. Approximately seven to ten percent of people over the age of 50 have dysphagia, although this estimate may be low because not all symptomatic individuals seek medical care.(1–3) As eating is an important social activity, dysphagia can adversely impact self-esteem, social role functioning, and overall quality-of-life.(4)

Patients with thyroid disease may develop dysphagia as a result of direct compression of the swallowing organs by an enlarged thyroid gland, invasion or nerve involvement by thyroid carcinoma, or as an unintended consequence of treatments such as surgery or radiation therapy.(5) Dysphagia due to thyrotoxic myopathy is a rare primary manifestation of hyperthyroidism.(6–8) There have also been case reports of ectopic lingual thyroid presenting as dysphagia.(9–12) Diagnostic studies such as videofluoroscopy, modified barium swallow, manometry, and endoscopy may be used to evaluate mechanical abnormalities underlying dysphagia. However, until recently, no condition-specific instrument has been available to measure the effect of dysphagia on quality-of-life. In the present study we used the swallowing quality of life (SWAL-QOL) outcomes assessment tool to determine the impact of thyroid surgery on swallowing-related quality-of-life in patients with thyroid disease.

Materials & Methods

SWAL-QOL Instrument

The SWAL-QOL is a 44-item condition-specific instrument that assesses swallowing-related quality-of-life in eleven domains: Burden, Physical, Mental, Fear, Eating Desire, Eating Duration, Food Selection, Sleep, Fatigue, Social, and Communication (Table 1). The questionnaire is self-administered and takes less than fifteen minutes to complete. The instrument has been validated and has favorable psychometric properties, including high internal-consistency reliability and reproducibility. The scales of the instrument differentiate patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia from normal swallowers and are sensitive to clinically-relevant differences in dysphagia severity in patients with medically and surgically treated conditions.(13–16)

Table 1.

Domains and abbreviated items of the SWAL-QOL questionnaire, adapted from adapted from McHorney, et al. (12).

| Burden |

| Dealing with my SP is very difficult |

| My SP is a major distraction in my life |

| Physical |

| Coughing |

| Choking when eating |

| Choking when drinking |

| Thick saliva phlegm |

| Gagging |

| Too much saliva or phlegm |

| Having to clear throat |

| Drooling |

| Problems chewing |

| Food sticking in throat |

| Food sticking in mouth |

| Food or liquid dribbling out of mouth |

| Food or liquid dribbling out of nose |

| Coughing food or liquid out of mouth |

| Mental |

| My SP depresses me |

| I get impatient dealing with my SP |

| Being so careful when I eat or drink annoys me |

| My SP frustrates me |

| I’ve been discouraged by my SP |

| Fear |

| I fear I may start choking when I eat food |

| I worry about getting pneumonia |

| I am afraid of choking when I drink liquids |

| I never know when I am going to choke |

| Eating Desire |

| Most days, I don’t care if I eat or not |

| I don’t enjoy eating anymore |

| I’m rarely hungry anymore |

| Eating Duration |

| It takes me longer to eat than other people |

| It takes me forever to eat a meal |

| Food Selection |

| Figuring out what I can eat is a problem for me |

| It is difficult to find foods that I like and can eat |

| Sleep |

| I have trouble falling asleep |

| I have trouble staying asleep |

| Fatigue |

| I feel exhausted |

| I feel week |

| I feel tired |

| Social |

| I don’t go out to eat because of my SP |

| My SP makes is hard to have a social life |

| My usual activities have changed BOM SP |

| Social gatherings are not enjoyable BOM SP |

| My role with family/friends has changed BOM SP |

| Communication |

| People have a hard time understanding me |

| It’s been difficult for me to speak clearly |

Abbreviations: SP, swallowing problem; BOM, because of my.

Patient Selection & Data Collection

After institutional review board approval of the study protocol, patients were enrolled at the University of Wisconsin Hospital & Clinics (Madison, Wisconsin, USA) for this prospective longitudinal study. All patients evaluated for initial thyroid surgery between May 2002 and December 2002 were invited to participate in the study. Patients were provided with a description of the study, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. The sample included patients undergoing primary thyroid surgery; patients undergoing repeat thyroid surgery were excluded. Likewise, individuals unable to complete the self-administered questionnaire because of cognitive impairment or lack of English language fluency were ineligible to participate in the study.

Data were prospectively collected on patient demographic and clinicopathologic variables, including age, sex, use of thyroid hormone replacement therapy, surgical procedure (total thyroidectomy or thyroid lobectomy), mass of resected thyroid specimen, final histopathologic diagnosis, and perioperative complications. Post-operative hypoparathyroidism was defined as symptomatic hypocalcemia (serum calcium level below 8.4 mg/dL). Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury was diagnosed by means of laryngoscopic examination. Complications resulting in symptoms or signs that resolved within six months of surgery were considered transient; those that did not resolve in six months were classified as permanent.

In this longitudinal study, participants were asked to complete the self-administered SWAL-QOL questionnaire before thyroid surgery and one year after surgery. In cases of non-response, reminders were given by telephone and mail. Based on the answers to the items, scores were calculated for each SWAL-QOL domain on a scale of 0 to 100, with a score of 100 representing no impairment, the most favorable state.(15) Patients who did not return both questionnaires were excluded from the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and clinicopathologic characteristics of the 116 patients who received thyroid surgery and completed both surveys. Mean pre-operative and post-operative scores were calculated for each of the eleven SWAL-QOL domains. The statistical significance of the difference between pre-and post-operative scores for each domain was tested with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Associations between the various demographic and clinicopathologic independent variables and changes in SWAL-QOL scores were assessed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) based on the ranks of the data. Variables that were significant in a univariate model were also assessed in a multivariable model. All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software version 9.1, SAS Institute, Inc. (Cary, NC). All tests of significance were at the p < 0.05 level, and p-values were two-tailed.

Results

Completion of SWAL-QOL Questionnaires

Of 146 eligible patients, 116 (79%) completed both SWAL-QOL questionnaires. Thirty patients did not return the post-operative survey and were excluded. The excluded patients did not differ significantly from the 116 included patients in terms of age, sex, proportion with cancer, or mass of resected thyroid. In the 232 questionnaires completed by the 116 study patients, there were no unanswered questions.

Demographic, Disease, and Treatment Variables

Demographic-, disease-, and treatment-related variables for the study cohort are summarized in Table 2. The mean patient age was 49 years (SD=13), and 81% were female. Sixty-four patients (55%) underwent total thyroidectomy, with the remainder receiving thyroid lobectomy. Thirty (26%) had thyroid cancer. The most frequent benign thyroid conditions diagnoses were multinodular goiter (28%), Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (27%), and follicular adenoma (25%). The mean mass of the resected thyroid specimens was 36 grams (SD=34).

Table 2.

Characteristics of 116 patients with thyroid disease who underwent thyroid surgery and were evaluated with the SWAL-QOL instrument.

| Demographics | Percent |

|---|---|

| Patient age, years, mean ± SD | 49 ± 13 |

| Female gender | 81 |

| Diagnoses* | |

| Thyroid Cancer | 26 |

| Papillary carcinoma | 22 |

| Medullary carcinoma | 2 |

| Follicular carcinoma | 1 |

| Hurthle cell carcinoma | 1 |

| Benign Disease | |

| Multinodular goiter | 28 |

| Hashimoto’s thyroiditis | 27 |

| Follicular adenoma | 25 |

| Hurthle cell adenoma | 8 |

| Graves’ disease | 3 |

| Other benign lesion | 21 |

| Operation | |

| Total thyroidectomy | 55 |

| Thyroid lobectomy | 45 |

| Thyroid Hormone Replacement Therapy | |

| Prior to surgery | 15 |

| After surgery | 67 |

| Complications | |

| Transient hypoparathyroidism | 2 |

| Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury | 1 |

| Chyle leak requiring reoperation | 1 |

| Hematoma requiring reoperation | 1 |

Note: some patients received more than one diagnosis, e.g., mulitnodular goiter and follicular adenoma.

Before undergoing thyroid surgery, 17 patients (6%) were taking thyroid hormone replacement therapy (HRT) for hypothyroidism. After thyroid surgery, this number increased to 78 (67%).

Five patients (4%) had perioperative complications. Two patients had transient hypoparathyroidism requiring calcium supplementation which resolved within six months after surgery. One patient had a recurrent laryngeal nerve injury resulting in unilateral vocal cord paralysis. One patient developed a chyle leak and another patient developed a hematoma; both of these patients required reoperation.

Baseline Swallowing-Related Quality-of-Life in Patients with Thyroid Disease

Before surgery, the mean pre-operative SWAL-QOL scores were below 90 for all but two of the eleven SWAL-QOL domains (Table 3), indicating imperfect swallowing-related quality of life. The lowest mean scores were observed for the domains of Fatigue (63.4), Sleep (65.0), Physical (81.2), and Burden (84.6). The mean pre-operative scores were lower than those reported by McHorney and colleagues for a sample of 40 healthy male and female control subjects with normal oropharyngeal swallowing function in all SWAL-QOL domains except Food Selection and Communication (Table 3).(15)

Table 3.

Mean SWAL-QOL scores in 116 patients with thyroid disease and symptoms of dysphagia compared to mean scores of 40 individuals with normal swallowing function previously reported in the literature(15). A score of 0 represents the least favorable state, and 100 the most favorable.

| Domain | Thyroid Disease | Normal |

|---|---|---|

| Burden | 84.6 | n/a |

| Physical | 81.2 | n/a |

| Mental | 87.0 | n/a |

| Fear | 87.0 | 96.0 |

| Eating Desire | 92.5 | 93.2 |

| Eating Duration | 86.2 | n/a |

| Food Selection | 88.5 | 76.6 |

| Sleep | 65.0 | 76.3 |

| Fatigue | 63.4 | 73.0 |

| Social | 94.4 | n/a |

| Communication | 88.9 | 87.8 |

Changes in Swallowing-Related Quality-of-Life after Thyroid Surgery

After surgery, score improvements were seen in all of the SWAL-QOL domains (Table 4). The score change was statistically significant for eight of the eleven domains: Burden (increase of 7.8 points, p=0.0007), Physical (+5.8, p<0.0001), Mental (+6.1, p-value=0.0002), Fear (+5.9, p<0.0001), Food Selection (+5.3, p=0.0062), Sleep (+8.6, p<0.0001), Fatigue (+8.0, 0.0002), and Communication (+3.0, 0.0332).

Table 4.

Mean pre- and post-operative SWAL-QOL scores in 116 patients with symptoms of dysphagia who underwent thyroid surgery. A score of 0 represents the least favorable state, and 100 the most favorable. P-values correspond to the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

| Domain | Score Before Surgery | Score After Surgery | Score Change | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burden | 84.6 | 92.3 | + 7.8 | 0.0007 |

| Physical | 81.2 | 87.1 | + 5.8 | <0.0001 |

| Mental | 87.0 | 93.1 | + 6.1 | 0.0002 |

| Fear | 87.0 | 92.9 | + 5.9 | <0.0001 |

| Eating Desire | 92.5 | 94.5 | + 2.0 | 0.0973 |

| Eating Duration | 86.2 | 88.4 | + 2.2 | 0.1772 |

| Food Selection | 88.5 | 93.8 | + 5.3 | 0.0062 |

| Sleep | 65.0 | 73.6 | + 8.6 | <0.0001 |

| Fatigue | 63.4 | 71.5 | + 8.0 | 0.0002 |

| Social | 94.4 | 95.6 | + 1.3 | 0.2125 |

| Communication | 88.9 | 91.9 | + 3.0 | 0.0332 |

We measured the association between several patient-, disease-, and treatment-related factors and change in SWAL-QOL score. Resected thyroid specimen mass greater than 60 grams was associated with improvement in the domain of Eating Duration (p=0.0266). Perioperative complication predicted score decrease in the Social domain (p=0.0304). Age (p=0.007), female gender (p=0.0111), and lack of initiation of thyroid hormone replacement therapy (p=0.0066) were associated with improvement in Sleep. However, in a multivariate model, only age and hormone replacement therapy status were significant predictors. Female gender (p=0.0032) and thyroiditis (p=0.0202) were significantly associated with improvement in the domain of Fatigue; both factors were significant in a multivariate model.

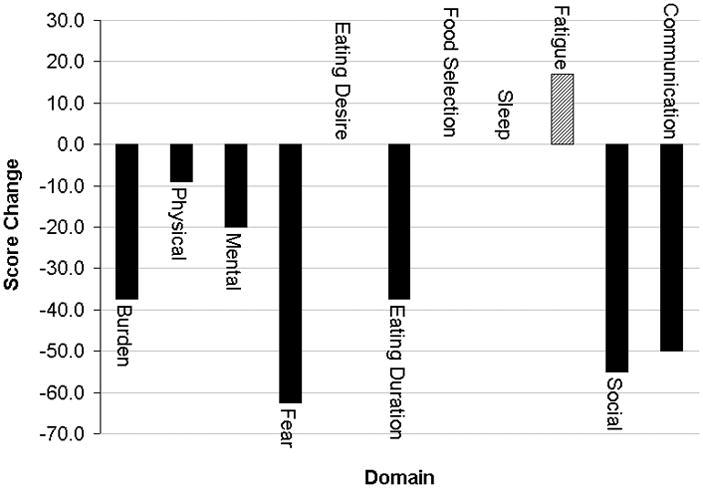

Impact of Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve Injury on SWAL-QOL Scores

One patient who underwent thyroid resection in this series suffered the complication of unilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve injury. In this patient, SWAL-QOL scores one year after surgery were lower than baseline for seven of the eleven domains (Figure 1). The largest score drops occurred in the domains of Fear (−62.5), Social (−55.0), and Communication (−50.0). These score changes were statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Change in SWAL-QOL scores in a patient who had the perioperative complication of unilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve injury.

Discussion

Patients with thyroid disease frequently complain of difficulty in swallowing. However, dysphagia in this population has not previously been studied in a prospective manner. Little is known about the prevalence of swallowing problems in patients with thyroid disease or whether dysphagia-related symptoms improve after surgical treatment. In this study, we used the SWAL-QOL instrument to assess swallowing-related quality-of-life in a series of patients who underwent initial thyroid surgery for a variety of benign and malignant thyroid conditions. We found that the mean scores were below 90, indicating imperfect swallowing-related quality-of-life, for all but two of the eleven domains of the SWAL-QOL instrument. Statistically significant score increases were seen in eight domains one year after surgery. Several patient-, disease-, and treatment-related factors predicted score improvement for various SWAL-QOL domains. Finally, dramatic decreases in numerous SWAL-QOL domains were noted in a patient who suffered the complication of unilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve injury.

Before surgery, the mean scores in our sample of patients with thyroid disease were lower in most SWAL-QOL domains than the scores of a healthy control population previously described by McHorney and colleagues.(15) The mean age of this historical control group was 73 years, compared to 49 years for the thyroid disease group. Aging is known to affect oropharyngeal swallowing function and other aspects of quality-of-life, (17–19) and it is possible that an even greater difference in SWAL-QOL scores would be observed between the thyroid disease group and age-matched controls. However, normal SWAL-QOL scores have not been reported in the literature for younger patients and we did not enroll a control group as part of our study.

The SWAL-QOL instrument has previously been used to measure swallowing-related quality-of-life in patients undergoing surgical treatment for head-and-neck pathology. Lovell and colleagues administered the SWAL-QOL questionnaire to 59 patients with no evidence of recurrence after treatment for nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Singapore.(20) Compared to the patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma, the patients with thyroid disease in our series had higher pre- and post-operative mean scores in all SWAL-QOL domains except Sleep and Fatigue. In another study, Bandeira et al. reported SWAL-QOL scores in 29 patients one-year after treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue.(21) Compared to the patients with tongue cancer, the patients with thyroid disease in the current study had higher baseline SWAL-QOL scores in all domains except Sleep.

After thyroid surgery, mean SWAL-QOL scores improved for the 116 patients with thyroid disease. The post-operative SWAL-QOL scores were similar to those of 40 “normal swallowers” in a study conducted by the developers of the SWAL-QOL instrument.(15) The “normal swallowers” in the study by McHorney et al. were significantly older than our study population. Differences in age and other patient variables make comparisons of SWAL-QOL score profiles from different published studies problematic. However, it is reasonable to conclude that the sample of patients with thyroid disease enrolled in this study were not “normal swallowers” at baseline, but instead had significant deficits in swallowing-related quality-of-life as measured by the SWAL-QOL instrument.

An important finding of this study is that statistically-significant improvements were seen in scores for eight of the eleven SWAL-QOL domains one year after thyroid resection relative to baseline. The largest improvements occurred for the Sleep, Fatigue, and Burden domains. Improvement in swallowing-related quality-of-life may represent a potential benefit of thyroid surgery that has heretofore been underappreciated by patients and surgeons.

We were interested in examining the impact of perioperative complications on swallowing-related quality-of-life as measured by the SWAL-QOL instrument. Univariate analysis demonstrated a significant inverse association between complication and improvement in the Communication domain score. The most serious complication that occurred in this series was a case of unilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve injury. The one-year post-operative SWAL-QOL scores for this patient were considerably lower than baseline for the majority of the domains. In this patient, the magnitude of score deterioration for the domains of Fear of Choking, Social, and Communication were 62.5, 55.0, and 50.0, respectively. As recurrent laryngeal nerve injury is a serious complication of thyroid surgery, the observed marked decreases in SWAL-QOL scores suggest that the instrument is responsive to clinically-relevant changes in swallowing function and quality-of-life at the individual level.

In summary, this study represents, to our knowledge, the first use of a condition-specific instrument to assess swallowing-related quality-of-life in patients with thyroid disease before and after thyroid surgery. Many patients with thyroid disease have the perception of abnormal swallowing function. In these patients with symptoms of dysphagia, thyroid surgery leads to significant improvements in many aspects of swallowing-related quality-of-life measured by the SWAL-QOL instrument. For patients with thyroid disease, thyroid resection may improve perception of swallowing function and quality-of-life.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Association of Academic Surgery Karl Storz Endoscopy Research Fellowship Award and a training grant (T32 CA90217-07) from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Presented at the 2007 meeting of the International Association of Endocrine Surgeons, International Surgery Week, Montreal, Canada, August 2007.

References

- 1.Lindgren S, Janzon L. Prevalence of swallowing complaints and clinical findings among 50–79-year-old men and women in an urban population. Dysphagia. 1991;6(4):187–192. doi: 10.1007/BF02493524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tibbling L, Gustafsson B. Dysphagia and its consequences in the elderly. Dysphagia. 1991;6(4):200–202. doi: 10.1007/BF02493526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spieker MR. Evaluating dysphagia. Am Fam Physician. 2000 Jun 15;61(12):3639–3648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ekberg O, Hamdy S, Woisard V, et al. Social and psychological burden of dysphagia: Its impact on diagnosis and treatment. Dysphagia. 2002 Spring;17(2):139–146. doi: 10.1007/s00455-001-0113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olson S, Cheema Y, Harter J, et al. Does frozen section alter surgical management of multinodular thyroid disease? J Surg Res. 2006 Dec;136(2):179–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noto H, Mitsuhashi T, Ishibashi S, et al. Hyperthyroidism presenting as dysphagia. Intern Med. 2000 Jun;39(6):472–473. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.39.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiu WY, Yang CC, Huang IC, et al. Dysphagia as a manifestation of thyrotoxicosis: Report of three cases and literature review. Dysphagia. 2004 Spring;19(2):120–124. doi: 10.1007/s00455-003-0510-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guldiken B, Guldiken SS, Turgut N, et al. Dysphagia as a primary manifestation of hyperthyroidism: A case report. Acta Clin Belg. 2006 Jan–Feb;61(1):35–37. doi: 10.1179/acb.2006.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallo A, Leonetti F, Torri E, et al. Ectopic lingual thyroid as unusual cause of severe dysphagia. Dysphagia. 2001 Summer;16(3):220–223. doi: 10.1007/s00455-001-0067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bayram F, Kulahli I, Yuce I, et al. Functional lingual thyroid as unusual cause of progressive dysphagia. Thyroid. 2004 Apr;14(4):321–324. doi: 10.1089/105072504323030997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahbar R, Yoon MJ, Connolly LP, et al. Lingual thyroid in children: A rare clinical entity. Laryngoscope. 2008 Jul;118(7):1174–1179. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31816f6922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rocha-Ruiz A, Beltran C, Harris PR, et al. Disphagia caused by a lingual thyroid: Report of one case. Rev Med Chil. 2008 Jan;136(1):83–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McHorney CA, Bricker DE, Kramer AE, et al. The SWAL-QOL outcomes tool for oropharyngeal dysphagia in adults: I. conceptual foundation and item development. Dysphagia. 2000 Summer;15(3):115–121. doi: 10.1007/s004550010012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McHorney CA, Bricker DE, Robbins J, et al. The SWAL-QOL outcomes tool for oropharyngeal dysphagia in adults: II. item reduction and preliminary scaling. Dysphagia. 2000 Summer;15(3):122–33. doi: 10.1007/s004550010013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McHorney CA, Robbins J, Lomax K, et al. The SWAL-QOL and SWAL-CARE outcomes tool for oropharyngeal dysphagia in adults: III. documentation of reliability and validity. Dysphagia. 2002 Spring;17(2):97–114. doi: 10.1007/s00455-001-0109-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McHorney CA, Martin-Harris B, Robbins J, et al. Clinical validity of the SWAL-QOL and SWAL-CARE outcome tools with respect to bolus flow measures. Dysphagia. 2006 Jul;21(3):141–148. doi: 10.1007/s00455-005-0026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoshikawa M, Yoshida M, Nagasaki T, et al. Aspects of swallowing in healthy dentate elderly persons older than 80 years. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005 Apr;60(4):506–509. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.4.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henderson E, Echave V. Dysphagia in aging. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006 Jan;40(1):88. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000190780.88397.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen PH, Golub JS, Hapner ER, et al. Prevalence of perceived dysphagia and quality-of-life impairment in a geriatric population. Dysphagia. 2008 Mar 27; doi: 10.1007/s00455-008-9156-1. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lovell SJ, Wong HB, Loh KS, et al. Impact of dysphagia on quality-of-life in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck. 2005 Oct;27(10):864–872. doi: 10.1002/hed.20250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Costa Bandeira AK, Azevedo EH, Vartanian JG, et al. Quality of life related to swallowing after tongue cancer treatment. Dysphagia. 2008 Jun;23(2):183–192. doi: 10.1007/s00455-007-9124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]