Abstract

Intestinal HCO3− secretion and NaCl absorption are essential for counteracting dehydration in marine teleost fish. We investigated how these two processes are coordinated in toadfish. HCO3− stimulated a luminal positive short-circuit current (Isc) in intestine mounted in Ussing chamber, bathed with the same saline solution on the external and internal sides of the epithelium. The Isc increased proportionally to the [HCO3−] in the bath up to 80 mM NaHCO3, and it did not occur when NaHCO3 was replaced with Na+-gluconate or with NaHCO3 in Cl−-free saline. HCO3− (20 mM) induced a ∼2.5-fold stimulation of Isc, and this [HCO3−] was used in all subsequent experiments. The HCO3−-stimulated Isc was prevented or abolished by apical application of 10 μM bumetanide (a specific inhibitor of NKCC) and by 30 μM 4-catechol estrogen [CE; an inhibitor of soluble adenylyl cyclase (sAC)]. The inhibitory effects of bumetanide and CE were not additive. The HCO3−-stimulated Isc was prevented by apical bafilomycin (1 μM) and etoxolamide (1 mM), indicating involvement of V-H+-ATPase and carbonic anhydrases, respectively. Immunohistochemistry and Western blot analysis confirmed the presence of an NKCC2-like protein in the apical membrane and subapical area of epithelial intestinal cells, of Na+/K+-ATPase in basolateral membranes, and of an sAC-like protein in the cytoplasm. We propose that sAC regulates NKCC activity in response to luminal HCO3−, and that V-H+-ATPase and intracellular carbonic anhydrase are essential for transducing luminal HCO3− into the cell by CO2/HCO3− hydration/dehydration. This mechanism putatively coordinates HCO3− secretion with NaCl and water absorption in toadfish intestine.

Keywords: NKCC, cAMP, carbonic anhydrase, bumetanide, proton pump

the intestine of marine fish absorbs NaCl and water to compensate for dehydration in a hyperosmotic environment. This hypoosmoregulatory mechanism relies in part on HCO3− secretion, in exchange for Cl− uptake, resulting in intestinal luminal concentration of HCO3− {[HCO3−]} of > 100 mM (20, 65). The resulting alkaline conditions lead to the formation of Ca2+ and Mg2+ carbonate precipitates and a reduction of osmotic pressure (20, 65). Water is absorbed following transepithelial NaCl absorption, and the carbonate precipitates are expelled with the feces. Intestinal carbonate precipitation takes place in all marine bony fish species investigated so far, and it has been argued that the combined piscine carbonates output contributes up to 15% of total oceanic carbonate production (64).

In the intestine of marine fish, the major pathway for NaCl absorption from the lumen and into the intestinal cells is through apical Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporters (NKCC), also known as bumetanide-sensitive cotransporter. In mammalian epithelia, the apical NKCC isoform is predominantly present in the thick ascending loop of Henle, and it is termed NKCC2 (10, 19, 28, 32, 39, 48, 49, 66). Several studies have confirmed the involvement of an NKCC2-like protein in fish intestine. The evidence includes a mucosal-positive transepithelial potential difference under in vivo-like conditions, related to Cl−- dependent short-circuit current (Isc) (1), codependence of Na+ and Cl− transport (12, 15, 38), dependence on an apical K+ conductance (14, 38), and, importantly, sensitivity to the loop diuretic bumetanide (15, 38, 42, 43). The presence of intestinal NKCC2 was confirmed by RT-PCR in seawater eels (7) and by immunohistochemistry in mudskipper from brackish water (65), killifish (34), and sea bass (31). Like many epithelia, the driving force for NaCl absorption is provided by basolateral Na+/K+-ATPases.

An additional pathway for apical Cl− entry is apical anion exchange, which can, in some cases, account for as much as 70% of the overall Cl− absorption by the intestinal epithelium (20). Interestingly, elevation of luminal NaCl results in a reduction of HCO3− secretion, despite the increased concentration of luminal substrate (Cl−) for the process (23). This response (reduction in anion exchange) to elevated luminal NaCl, which would favor salt absorption by cotransport pathways, suggests that coordination of the multiple Cl− uptake pathways takes place in the marine teleost intestine.

Intestinal bicarbonate secretion and NaCl and water absorption are regulated by several factors. In the winter flounder, atrial natriuretic factor and its downstream intracellular second messenger cGMP inhibit the ion-absorbing Isc (41, 42), and they also reduce the net inward flux of Na+ and Cl− (41). These effects may be related to the inhibition of NaCl and water absorption when euryhaline fish enter freshwater (15, 37), but they also could be involved in acclimation to seawater in eel (58). At least part of the cGMP effect is attributable to inhibition of apical NKCC and K+ channels activity (51), a regulation that also takes place in the mammalian thick ascending loop of Henle (2).

Addition of 8-Br-cAMP (an exogenous, phosphodiesterase-resistant cAMP analog) also affects Isc, but the inhibition is incomplete and the underlying cellular mechanisms are poorly understood. Some studies have applied 8-Br-cAMP in combination with theophylline, and they have found robust inhibition of Isc and Na+ and Cl− absorption (13, 15). However, theophylline is a nonspecific phosphodiesterase inhibitor that prevents both cAMP and cGMP degradation. When applied alone, 8Br-cAMP increased both Cl− absorption and secretion in a manner that resulted in a reduction (although not statistically significant) of net Cl− absorption, together with inhibitions of the outside-positive Isc and net K+ secretion and an increase in transepithelial conductance (Gte) (51). Thus, it appears that regulation of ion transport across fish intestine by cAMP involves multiple, possibly opposing, pathways.

The anion bicarbonate is an overlooked factor that regulates ion absorption in fish intestine. Reducing the saline's [HCO3−] from 20 mM to 5 mM induces an ∼60% reduction of Cl− absorption and Isc, a 30% reduction of Na+ absorption, and a significant increase in Gte (12, 13). HCO3− stimulation of ion absorption has been attributed to increases in pH (12), which stimulates NaCl and water absorption on its own (44). However, it is possible that both pH and HCO3− have synergistic stimulatory effects via independent mechanisms not yet identified.

One of such potential mechanisms is the newly identified soluble adenylyl cylase (sAC). sAC is an evolutionary conserved signaling enzyme whose activity is directly modulated by HCO3− to produce cAMP (3, 6, 63). Unlike the classic, hormonal- and G protein-regulated transmembrane ACs (tmACs), sAC is present in the cell cytoplasm and in organelles (67, 68). sAC has been proposed to be a universal sensor of HCO3−, and indirectly, of pH and Pco2 (6). Furthermore, sAC has recently been shown to be present in an elasmobranch fish, the dogfish Squalus acanthias, where it is essential for activating branchial H+ absorption and HCO3− secretion to counteract blood alkalosis (63). Like mammalian and cyanobacterial sACs (6, 25, 55), dogfish sAC (dfsAC) is bicarbonate responsive and inhibited by two unrelated small molecules, 4-catechol estrogen (CE) and KH7 (63).

In the present paper, we have investigated whether sAC is involved in regulating NaCl absorption across the intestinal epithelium of a marine fish in response to elevated HCO3−, a feature that might explain previous results and may also apply to other NaCl-absorbing epithelia.

METHODS

Animals.

Gulf toadfish (Opsanus beta) 20–30 g in size, from Biscayne Bay, FL, were obtained from shrimp fishermen during the winter and spring of 2008 and 2009 and transferred to holding facilities at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences. Procedures were approved by the University of Miami Animal Care and Use Committee. On arrival, the fish received a prophylactic treatment for ectoparasites, as previously described (35). Fish were provided short lengths of polyvinylchloride tubing as shelters in 80-liter glass aquaria that received a continuous flow of filtered seawater (salinity 27–30 ppt, 22–25°C, from Bear Cut, Florida). Fish were fed frozen squid twice weekly, but food was withheld 48 h before experimentation. Only tissues from males and nonovigerous females were used for the procedures outlined below.

Isc and Gte measurements.

Toadfish were anaesthetized with MS-222 (0.5 g/l; Argent Laboratories, Redmond, WA), and the spinal chord was severed. After opening the abdominal cavity, the anterior intestine (from the pyloric sphincter to ∼1.5 cm distally) was dissected, cut open, and mounted in a tissue holder that exposed 0.7 cm−2 epithelial surface area (not considering villi and microvilli). The tissue-containing holder was inserted in an Ussing chamber (model P2300; Physiological Instruments, San Diego, CA) containing 2 ml of pregassed saline. During the experiments, gas mixes were delivered to each hemichamber through airlifts to maintain O2, CO2 and HCO3− levels constant and promote mixing in the bathing solutions. The Ussing chambers were placed in chamber holders maintained at 25 ± 1°C throughout experimentation. Current and voltage electrodes (model P2020-S; Physiological Instruments) connected to amplifiers (model VCC600; Physiological Instruments) recorded the Isc under voltage-clamp conditions (0 mV). At 60-s intervals, the Gte was calculated from an imposed 1-mV voltage pulse from the mucosal to the serosal side and the resulting current deflection. Isc measurements were logged on a personal computer using a data acquisition system (BIOPAC systems interface with AcqKnowledge software, version 3.8.1).

The bathing saline was applied symmetrically into both hemichambers, and its composition was (in mM) 151 NaCl, 3 KCl, 0.88 MgSO4, 4.6 Na2HPO4, 0.48 K2HPO4, 1 CaCl2, 11 HEPES-free acid, 11 HEPES-free salt and 4.5 urea. All saline solutions were bubbled with 100% O2 or 0.3% CO2-99.7 O2 before adjusting osmolarity to 330 mOsm and pH to 7.8. Serosal saline also contained 3 mM glucose. Mounted epithelia were initially bathed in this saline (notice the absence of HCO3−) gassed with 100% O2 until a stable Isc was reached. To elevate [HCO3−], different volumes of a 1 M NaHCO3 stock solution were pipetted into both hemichambers to avoid diffusive fluxes, and the gas was changed to 0.3% CO2-99.7 O2. Pharmacological inhibitors were injected into the luminal bath from concentrated stocks in DMSO, and the added volume of drug was 2 μl in all cases. DMSO alone had no effect on Isc or Gte. After each change of saline or addition of drug, it typically took 15–20 min for Isc and Gte to reach new stable values. The Isc and Gte after at least additional 20 min of stable readings were used for statistical analyses.

Western blot analysis and immunofluorescence.

The following antibodies were used: mouse monoclonal α5 (against α1- and β1-subunits of chicken Na+/K+-ATPase; 0.01 μg/ml in Western blot analysis, 0.05 μg/ml in immunofluorescence), mouse monoclonal T4 (against the carboxy-term of human NKCC Met-902 to Ser-1212; 0.5 μg/ml in Western blot analysis, 0.2 μg/ml in immunofluorescence), rabbit polyclonal dfsAC antibodies [against an epitope in dfsAC: INNEFRNYQGRINKC (63); 0.15 μg/m1 in Western blot analysis, 70 μg/ml in immunofluorescence], and mouse monoclonal R7 [against an epitope in mammalian sAC: EIERIPDQRAVKV (27); 0.1 μg/ml in Western blot analysis, 20 μg/ml in immunofluorescence]. The α5 and T4 antibodies developed by Douglas Fambourgh (John Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) and Christian Lytle (University of California Riverside, Riverside, CA), respectively, were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and maintained by Department of Biological Sciences, The University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA.

For Western blot analysis, the anterior intestine was dissected, flash frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C. Samples were homogenized in lysis buffer (in mM: 150 NaCl, 5 EDTA, 50 Tris, 1 PMSF, 1 DTT, and 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, pH 7.5) by using a glass Dounce homogenizer and were spun down (10 min, 16,000 g, 4°C). Approximately 10 μl of the supernatant (15 μg total protein) was combined with 2× Laemmli buffer (30), heated (70°C, 10 min), and used in PAGE-Western blot analysis. Purified recombinant rat sAC protein, produced as previously described (6) was used as control for the R7 antibody.

For immunofluorescence, the anterior intestine was dissected, cut into ∼2 mm sections, and immersed in fixative (4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PBS) overnight at 4°C. The fixative was replaced by ice-cold 15% (wt/vol) sucrose, incubated for 4 h at 4°C, then replaced by 30% (wt/vol) sucrose, and stored at 4°C. Fixed tissues were sectioned at 4–8 μm using a cryostat (−15°C) and immunostained. Sections were treated with 1% SDS in PBS, followed by 2× 5 min washes in PBS and blocking in 2% normal goat serum in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Incubation with the antibodies (in 2% normal goat serum in PBS) was performed overnight at 4°C. After 3× 5 min washes in PBS, the secondary antibodies Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG or Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG were applied for 1 h at room temperature and subsequently washed 3× 5 min in PBS. For double labeling, sections were first labeled with dfsAC (overnight) and fluorescent anti-rabbit IgG (1 h), followed by blocking and 1-h incubation at room temperature (T4) or overnight incubation at 4°C (R7) and anti-mouse fluorescent IgG (1-h room temperature) with 3× 5 min washes in PBS in between. All sections were mounted using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI)-containing medium (Vector Labs).

Statistical analyses.

All data sets were analyzed using one-way repeated-measures ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple-comparisons test using GraphPad Prism version 4.0a for Macintosh (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Differences between means were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Bicarbonate stimulates Isc and Gte.

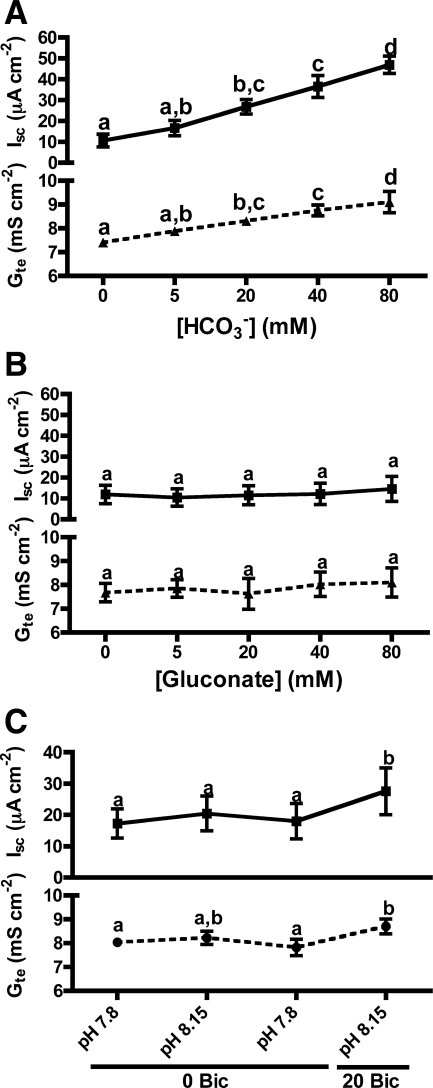

Increasing the [NaHCO3] in the bathing solutions resulted in dose-dependent increases in the outside-positive Isc and in Gte (Fig. 1A). These effects were not due to the extra Na+ or to increases in osmotic pressure, since Na+-gluconate has no effect on Isc or Gte (Fig. 1B). Therefore, the observed stimulations were due to HCO3− itself and/or to the associated increase in pH. For subsequent experiments, 20 mM NaHCO3 was used because it induced significant changes on Isc and Gte and it was within or near physiological values for both the luminal and the serosal sides. Addition of 20 mM NaHCO3 raised the saline's pH from 7.80 to 8.15. Since a pH of 8.15 did not change Isc significantly and it only produced a small increase in Gte (Fig. 1C), the HCO3− stimulation of Isc by 20 mM HCO3− is independent of pH.

Fig. 1.

HCO3− stimulation of short-circuit current (Isc) and transepithelial conductance (Gte) across toadfish anterior intestine: dose-response to NaHCO3 (A), dose-response to Na+-gluconate (B), and effect of 20 mM NaHCO3 and the equivalent change in pH (C) . Bic, bicarbonate. Letters indicate different levels of statistical significance (repeated-measures ANOVA, Tukey's multiple-comparisons test, P < 0.05, n = 4–5).

sAC in toadfish intestine.

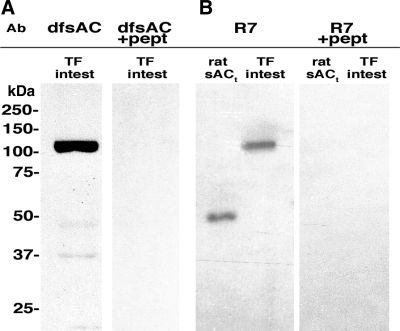

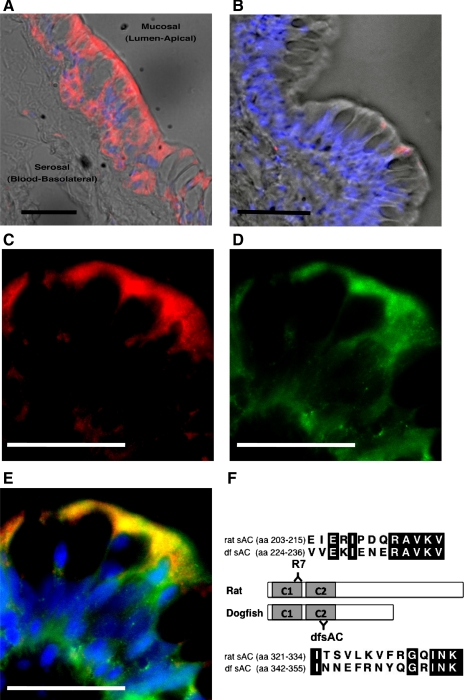

We hypothesized that sAC, a recently discovered HCO3−-responsive signaling enzyme, mediates the HCO3−-stimulation of Isc in toadfish intestine. Polyclonal antibodies against dfsAC recognized a single specific band of ∼100 kDa in anterior intestine samples from toadfish (Fig. 2A), which was absent in the peptide preabsorption and preimmune serum controls (not shown). A mouse monoclonal antibody (R7), raised against a different epitope in mammalian sAC, also recognized a specific ∼100 kDa band (Fig. 2B). sAC in the toadfish intestine was detected by immunofluorescence using dfsAC (Fig. 3, A, C, and E) and R7 (Fig. 3, D and E) antibodies. sAC immunoreactivity was present throughout the epithelial intestinal cells but not directly on the apical membrane. Incubation with preimmune serum (Fig. 3B), mouse IgG, or dfsAC antibodies preabsorbed with specific peptide (not shown) resulted in no signal.

Fig. 2.

Soluble adenylyl cyclase (sAC) in toadfish (TF) intestine. Western blot analysis using antibodies (Ab) against dogfish sAC (dfsAC; A) and mammalian sAC mouse monoclonal antibody R7 (B). A purified, 50-kDa isoform of rat sAC (sACt) was used as control for R7. The second lane in each panel shows preabsorption with peptides (pept) corresponding with the respective epitopes.

Fig. 3.

sAC in toadfish intestine. Immunofluorescence detection using antibodies against dfsAC (A and C; red) and mammalian sAC (D; R7, green). B: incubation with dfsAC preimmune serum. Brightfield and fluorescent pictures (A and B) are overlaid. E: double staining using dfsAC and R7 antibodies. Yellow indicates colocalization of signals. Nuclei are stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI; blue) (A, B, and E). Scale bars: 10 μM. F: sequences and positions of antigen peptides in rat and dfsAC. Conserved amino acid residues are shaded in black, similar residues are in grey.

Involvement of sAC in the stimulation of Isc by HCO3−.

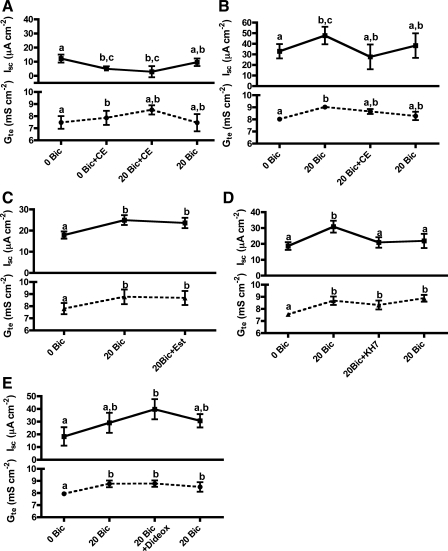

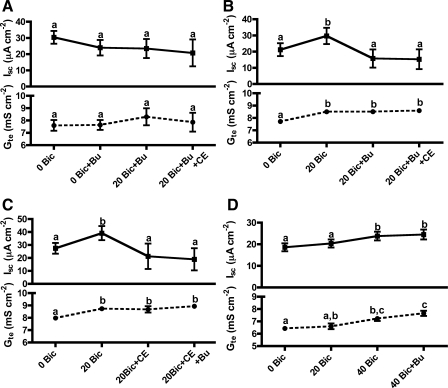

Micromolar concentrations of CE specifically inhibits all known sAC and sAC-related enzymes, including CyaC from cyanobacteria (55), dfsAC (63), and mammalian sAC (47, 55). CE (30 μM) significantly reduced the Isc in the absence of HCO3− in the bathing saline and slightly increased Gte (Fig. 4A). Subsequent addition of 20 mM HCO3− in the presence of CE failed to stimulate Isc, but Gte increased similar to controls; the CE inhibition of Isc was only partially reversible (Fig. 4A). Application of CE after Isc had been stimulated by 20 mM HCO3− completely abolished the HCO3− stimulation (Fig. 4B). 17β-estradiol (30 μM), a compound related to CE that is inert toward sAC-like cyclases (47, 55) did not significantly affect the HCO3−-stimulated Isc (Fig. 4C). Although similar concentrations of KH7, the most specific sAC inhibitor available (25), failed to affect Isc, most KH7 precipitated immediately after entering the bathing saline. Precipitation was exacerbated by the continuous gas bubbling necessary during these experiments. To increase the KH7 concentration ([KH7]) in solution, the nominal [KH7] was raised to 200 μM, which resulted in significant inhibition of the HCO3−-stimulated Isc (Fig. 4D). The real [KH7] in solution during these experiments is unknown, but based on the visible precipitate it certainly was much lower than 200 μM.

Fig. 4.

Involvement of sAC in the HCO3− stimulation (20 mM) of Isc and Gte across toadfish anterior intestine. A: sAC inhibitor 4-catechol estrogen (CE; 30 μM) prevents the HCO3− stimulation of Isc. B: CE inhibits the Isc previously stimulated by HCO3−. C: 17β-estradiol (Est) does not affect the stimulated Isc. D: KH7 (200 μM), another sAC inhibitor, also inhibits the Isc previously stimulated by HCO3−. The real KH7 concentration is not known because KH7 was only partially soluble in the bathing saline. E: 2′5′-dideoxyadenosine (Dideox, 50 μM), a specific inhibitor of transmembrane adenylyl cyclases, has the opposite effect on Isc compared with CE and KH7. Letters indicate different levels of statistical significance (repeated-measures ANOVA, Tukey's multiple-comparisons test, P < 0.05; n = 5–6).

Although the specificity of CE for sAC is much higher than for tmACs, high concentrations of CE can also inhibit tmACs (55). To test the potential involvement of tmACs, we applied 2′5′-dideoxyadenosine (50 μM), which inhibits tmAC-dependent cellular processes without affecting sAC (50). Unlike CE, 2′5′-dideoxyadenosine increased the outside-positive HCO3−-stimulated Isc (Fig. 4E). These results suggest that the CE effect is not due to cross-reaction with tmACs.

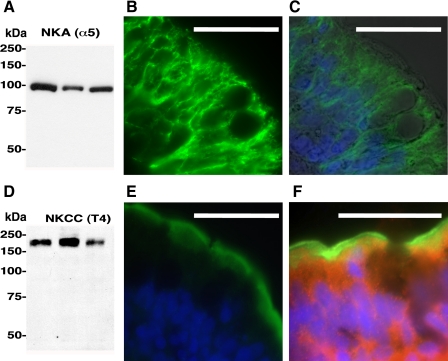

NKCC and Na+-K+-ATPase in toadfish intestine.

Two major players in fish intestinal NaCl absorption are apical NKCC and basolateral Na+/K+-ATPase. However, these transporters have never been shown to be present in toadfish intestine. T4 (against human NKCC) and α5 (against avian Na+/K+-ATPase) monoclonal antibodies recognized single bands of ∼180 and ∼100 kDa, respectively (Fig. 5, A and D), which match previously published results from fish (9, 26, 60, 61). In immunostained sections, both transporters were found in almost all epithelial cells, with the exception of larger, round cells that are presumably goblet (mucus secreting) cells. NKCC was predominantly present in the apical membrane and subapical area (Fig. 5E), indicative of an NKCC2 isoform. Weaker NKCC immunostaining was also found throughout the cell (presumably an NKCC1 isoform), but the signal was only observed after increasing the sensitivity of the detector significantly. Na+/K+-ATPase was present throughout the cells, presumably in basolateral infoldings typical of marine fish intestine (12, 40, 53); Na+/K+-ATPase immunoreactivity was absent from the apical membrane (Fig. 5, B and C). Because NKCC and sAC immunoreactivities overlapped in the subapical region (Fig. 5F), we next tested whether the HCO3− and sAC stimulation of Isc was due to activation of NKCC.

Fig. 5.

Na+/K+-ATPase (NKA), Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter (NKCC) and sAC immunoreactivity in toadfish intestine. NKA: Western blot analysis (n = 3) (A); immunofluorescence (B) and brightfield overlay (C). Nuclei have been stained with DAPI (blue). Notice that NKA is present in basolateral infoldings and absent in the apical membrane. NKCC: Western blot analysis (n = 3) (D); immunofluorescence (E). Notice that NKCC signal is strongly apical and subapical. F: overlay of NKCC signal (green) and sAC signal (red). Scale bars: 10 μM.

Involvement of NKCC in the stimulation of Isc by HCO3−.

Sensitivity to bumetanide is a hallmark of NKCC (66). Apical application of bumetanide (10 μM) completely prevented (Fig. 6A) or abolished (Fig. 6B) the HCO3−-stimulated Isc. The inhibitory effects of bumetanide and of the sAC inhibitor CE were not additive, regardless of the order of application (Fig. 6, A–C), suggesting that sAC and NKCC belong in the same pathway. To confirm that the Isc was indeed carried by Cl− ions, we conducted experiments in chloride-free bathing saline (chlorides substituted by gluconates). In this saline, 20 mM HCO3− did not stimulate Isc or Gte (Fig. 6D). Although 40 mM HCO3− did stimulate Isc in Cl−-free conditions, the stimulation was minor, and it was not inhibited by bumetanide (Fig. 6D), indicating the effect is different from that studied in normal, Cl−-containing saline.

Fig. 6.

Involvement of NKCC in the HCO3−-stimulation (20 mM) of Isc and Gte across toadfish anterior intestine. A: NKCC inhibitor bumetanide (Bum; 10 μM) prevents the HCO3− stimulation of Isc, the sAC inhibitor CE (30 μM) does not induce any further inhibition. B: bumetanide inhibits the Isc previously stimulated by HCO3−; CE does not have any further effect. C: same as in B, but the order of application of CE and bumetanide are reversed. D: in the absence of chloride ions in the bathing saline (replaced by gluconate), 20 mM NaHCO3 does not stimulate Isc or Gte. NaHCO3 (40 mM) induced a small, significant stimulation but it was not dependent on NKCC. Letters indicate different levels of statistical significance (repeated-measures ANOVA, Tukey's multiple-comparisons test, P < 0.05; n = 5–6).

Involvement of V-H+-ATPase and carbonic anhydrase in the stimulation of Isc by HCO3−.

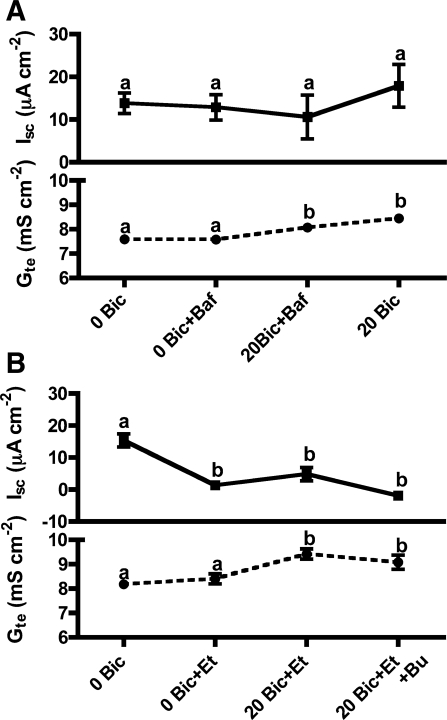

Apical addition of the V-H+-ATPase inhibitor bafilomycin (1 μM) prevented the HCO3−-stimulated Isc (Fig. 7A). Etoxolamide (1 mM), a permeable inhibitor of carbonic anhydrase, also prevented the HCO3−-stimulated Isc, and it additionally reduced the basal Isc under HCO3−-free conditions (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Involvement of V-H+-ATPase (VHA) and carbonic anhydrase (CA) in the HCO3− stimulation (20 mM) of Isc and Gte across toadfish anterior intestine. A: VHA inhibitor bafilomycin (Baf; 1 μM) prevents the HCO3− stimulation of Isc. VHA inhibition was not reversible. B: permeable CA inhibitor etoxolamide (Et; 1 mM) inhibits the basal Isc and prevents the stimulation by HCO3−. Bumetanide does not have any further effect. Letters indicate different levels of statistical significance (repeated-measures ANOVA, Tukey's multiple-comparisons test, P < 0.05; n = 5).

DISCUSSION

The intestine of marine fish is an excellent model to study epithelial NaCl absorption because of the homogeneity of cell types and its well-characterized electrophysiology. In fact, the luminal-positive Isc across fish intestine has been established to be equivalent to the asymmetrical net Na+ and Cl− absorption (reviewed in Ref. 37).

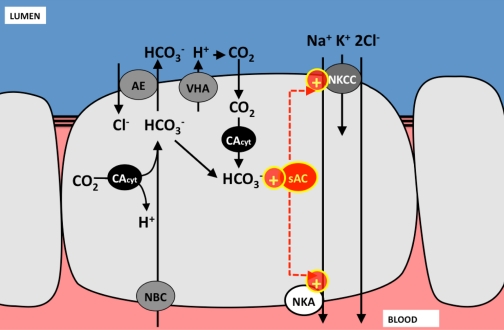

Our results demonstrate that the anion HCO3− stimulates NaCl absorption across the anterior intestine of toadfish, an effect that is independent of alkaline pH. Regulation of NaCl absorption by HCO3−/pH in the marine fish intestine is not surprising considering the processes of carbonate precipitation and NaCl-driven water absorption. While a portion of the HCO3− secreted into the intestinal lumen by apical anion exchangers of the Slc26a6 family (29) precipitates as CaCaO3 and MgCaO3, there is still significant (up to 100 mM) HCO3− dissolved in the luminal fluids (65). Our proposed model for HCO3−-stimulated NaCl absorption is depicted in Fig. 8. Part of the dissolved HCO3− combines with H+ pumped into the lumen by V+-H+-ATPases, which is known to be present in the apical membrane of toadfish intestinal cells (22). This reaction yields CO2 and H2O, and, while it might be catalyzed by extracellular carbonic anhydrase, the complete inhibition by apical bafilomycin suggests enzymatic catalysis is not necessary for the stimulation of Isc. According to our proposed model, luminal CO2 then diffuses inside the intestinal cells where it is hydrated back into H+ and HCO3− by cytoplasmic carbonic anhydrase. Interestingly, in intestinal cells of seawater-acclimated rainbow trout, cytoplasmic carbonic anhydrase is located in the subapical region (21), which is also where sAC is most abundantly present in toadfish intestinal cells. Therefore, it is likely that intracellular HCO3− generated by carbonic anhydrase activates sAC, which, in turn, activates apical NaCl absorption across NKCCs in a yet undetermined manner, but which should depend on cAMP. The driving force for NaCl absorption is provided by basolateral Na+/K+-ATPases, which we have confirmed to be at the toadfish intestinal epithelium by Western blot analysis and immunohistochemistry. The Na+/K+-ATPase is another potential target of sAC activity.

Fig. 8.

Model for the activation of Isc by HCO3− in toadfish intestinal cells. The anion exchanger secrets intracellular HCO3− [produced by cellular metabolism and imported by NBC from the blood (59)] into the intestinal lumen. Luminal HCO3− results in Ca2+ and Mg2+ precipitation (not shown), a fraction of the excess HCO3− combines with H+ pumped by the VHA to form CO2, which diffuses into the intestinal cells. CAcyt hydrates CO2 back into HCO3− and H+ (not shown). HCO3− activates sAC, which stimulates (+) the activity of apical NKCC to absorb NaCl via a cAMP-dependent mechanism yet to be determined. Putative apical K+ and basolateral Cl− channels are not shown. CAcyt, cytoplasmic carbonic anhydrase; NBC, Na+/HCO3− cotransporter.

sAC in toadfish intestine.

Based on immunodetection with two different antibodies, an sAC-like protein is present in the toadfish intestine. Unfortunately, we were unable to clone toadfish sAC by a variety of approaches, including bioinformatic methods and homology cloning using degenerate primers. Based on our experience working with mammalian (3, 11) and dfsAC (63), cloning the toadfish sAC ortholog is challenging because of the relatively low conservation of the sAC genes between species and the typically low sAC mRNA abundance. Nonetheless, immunodetection of a protein band of identical molecular size and colocalization in microscopy sections using two different antibodies, although heterologous, is good evidence for the presence of sAC in toadfish. The alternatives, that a protein unrelated to sAC contains the two different epitopes or that the antibodies recognize different proteins of identical molecular size, are highly unlikely.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to attempt selective inhibition of sAC and tmACs in an ion-transporting epithelium. Inhibition of sAC (with CE and KH7) had the opposite effect of inhibition of tmACs (with 2′5′-dideoxyadenosine). This finding has two profound implications. First, it suggests that cAMP signaling in toadfish intestinal cells occurs in defined intracellular microdomains (i.e., basolateral and apical membranes, cytoplasm, etc.) and that each of them may exert different, even opposing physiology. Second, it shows that studies using permeable cAMP analogs should be interpreted with caution, as the cAMP analogs are likely to have multiple effects on cellular physiology through at least two different cAMP signaling pathways. This situation is further complicated by the common use of nonspecific inhibitors of phosphodiesterases, which could not only prevent the degradation of cAMP from multiple sources, but also of cGMP.

Targets of the presumptive HCO3−/sAC pathway.

The two most likely mechanisms of NKCC activation are PKA-mediated insertion of NKCC from subapical vesicles into the apical membrane and PKA-phosphorylation of NKCC already present at the apical membrane. There is abundant evidence supporting these two mechanisms, which are not mutually exclusive, in other systems. cAMP has been shown to promote the insertion of mammalian NKCC2 into the cell membrane both in heterologous expression experiments in Xenopus oocytes (36) and in the native thick ascending loop of Henle (4, 46). The cAMP effect has been traditionally linked to hormones, such as vasopressin (reviewed in Ref. 16), but the potential involvement of sAC has not yet been considered, likely due to this signaling enzyme being discovered recently. Notably, sAC mRNA is present in several NaCl and water absorbing mammalian epithelia, including small intestine (17), and sAC has been immunolocalized in the thick ascending loop of Henle in the kidney (47).

Vasopressin induces NKCC2 activation in at least two ways: increased translocation into the membrane and direct NKCC2 phosphorylation (18). However, a direct link between vasopressin, cAMP, PKA, and NKCC2 has not yet been established. Our immunohistochemical pictures from toadfish intestinal fragments (which were immediately fixed after dissection) clearly show that NKCC is present both in the apical membrane and in the subapical region of intestinal epithelial cells, leaving open both trafficking and direct phosporylation as possible NKCC activating mechanisms in response to HCO3− via sAC.

Alternatively or additionally, the pathway might involve activation of Na+/K+-ATPase. Because this enzyme is the main driving force behind NaCl absorption via NKCC (20, 23), a putative modulation of Na+/K+-ATPase by sAC would explain why sAC and NKCC inhibitors did not show additive effects. Interestingly, sAC has been shown to regulate Na+/K+-ATPase catalytic activity in kidney collecting duct cells (24).

Some of our experimental conditions, inhibitors, and results require a few clarifications. First, to avoid diffusive ion movement across intestinal segments mounted in Ussing chamber, it is essential to apply symmetrical conditions in the saline at the serosal and mucosal sides. We mimicked the composition of the serosal side (blood) found in live fish, reasoning that it is best for cell function. A [HCO3−] of 80 mM, although normal for the intestinal lumen, is much higher than the normal [HCO3−], pH, and osmolarity in the serosal side. Therefore, we used 20 mM HCO3− in all subsequent experiments, which also stimulated Isc significantly. We predict the greater Isc stimulated by higher [HCO3−] to be at least partially dependent on sAC. Second, HCO3− not only stimulated the absorptive Isc, but it also increased Gte in a dose-dependent manner. None of the inhibitors affected the stimulated Gte, although 20 mM HCO3− failed to stimulate Gte in Cl−-free conditions. It is difficult to speculate about these results, but the most likely candidates are transporters in the apical membrane (which typically dominates Gte) such as secretory K+ channels and electrogenic Cl−/HCO3− exchangers (SLC26a6 and possibly SLC26a3), which might be directly or indirectly modulated by HCO3− and/or pH . Third, inhibition of sAC or carbonic anhydrase inhibited the basal Isc in HCO3−-free saline. This points to a role of endogenous metabolic CO2 as an additional modulator of NaCl transport in toadfish intestine via carbonic anhydrase and sAC.

Interaction between intestinal NaCl absorption and anion exchange.

Earlier observations demonstrate that conditions of low luminal NaCl, which are unfavorable for salt absorption via NKCC, results in elevated Cl− absorption by anion exchange as evident from elevated HCO3− secretion (23). This enhanced anion exchange appears to be, at least in part, via SLC26a6 proteins (22, 29). The present study, on the other hand, demonstrates that conditions more adverse to Cl− absorption via anion exchange (high-luminal HCO3−) stimulate NaCl absorption via NKCC. It thus appears that the pathways for Cl− absorption by the intestinal epithelium in marine fish are coordinated, depending on luminal conditions to allow for Cl− and thus water absorption. While sAC appears to be the link between luminal HCO3− and NKCC activation, it remains to be established how low NaCl stimulates anion exchange (or how high NaCl inhibits anion exchange).

HCO3− as a modulator of epithelial ion transport.

From an ion-transporting perspective, HCO3− is typically only considered as a substrate for anion exchangers and Na+/HCO3− cotransporters (57), and any additional effects are usually attributed to indirect changes in pH. However, HCO3− can also act as a signaling molecule, which can gain specificity and be amplified through HCO3−-responsive soluble adenylyl cyclase (3, 6, 45, 56, 63).

Several studies have reported modulation of transepithelial ion transport by HCO3− and alkaline pH in a variety of epithelia, including rat small intestine (52), rat colon (8), human jejunum (54), crab gills (62), fish intestine (5, 12, 13), and frog stomach (33). These unexplained effects of HCO3− could depend on sAC, similar to the toadfish intestine, or to other yet unidentified HCO3− modulation.

Perspectives and Significance

We have identified a novel regulatory pathway for epithelial NaCl absorption, which depends on HCO3−, and it may involve sAC and NKCC. Our results also suggest the existence of cAMP signaling microdomains in ion-transporting epithelia. Activation of NaCl absorption by HCO3−/sAC/NKCC may be essential for intestinal carbonate precipitation and water absorption, a process that is essential for marine fish osmoregulation and which has implications for the ocean carbon cycle. Moreover, the literature suggests this novel regulation may exist in other epithelia.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the Journal of Experimental Biology Traveling Fellowship to M. Tresguerres and National Science Foundation Grant IOS0743903 (to M. Grosell) and National Institutes of Health Grants GM-62328 and NS-55255 to L. R. Levin and J. Buck.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the members of Martin Grosell's, Lonny R. Levin's, and Jochen Buck's labs for their assistance, in particular Dr. Josi Taylor for sample fixation, Janet Genz, and Ed Mager. We are grateful to Dr. Larry Palmer for critically reading the manuscript. Dr. Danielle McDonald kindly provided us with a number of experimental fish.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ando M. Intestinal water transport and chloride pump in relation to sea-water adaptation of the eel, Anguilla japonica. Comp Biochem Physiol A 52: 229–233, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ares GR, Caceres P, Alvarez-Leefmans FJ, Ortiz PA. cGMP decreases surface NKCC2 levels in the thick ascending limb: role of phosphodiesterase 2 (PDE2). Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F877–F887, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buck J, Sinclair ML, Schapal L, Cann MJ, Levin LR. Cytosolic adenylyl cyclase defines a unique signaling molecule in mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 79–84, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caceres PS, Ares GR, Ortiz PA. cAMP stimulates apical exocytosis of the renal Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter NKCC2 in the thick ascending limb. J Biol Chem 284: 24965–24971, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charney AN, Scheide JI, Ingrassia PM, Zadunaisky JA. Effect of pH on chloride absorption in the flounder intestine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 255: G247–G252, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y, Cann MJ, Litvin TN, Iourgenko V, Sinclair ML, Levin LR, Buck J. Soluble adenylyl cyclase as an evolutionarily conserved bicarbonate sensor. Science 289: 625–628, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cutler CP, Cramb G. Differential expression of absorptive cation-chloride-cotransporters in the intestinal and renal tissues of the European eel (Anguilla anguilla). Comp Biochem Physiol B 149: 63–73, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dagher PC, Egnor RW, Charney AN. Effect of intracellular acidification on colonic NaCl absorption. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 264: G569–G575, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deigweiher K, Koschnick N, Portner HO, Lucassen M. Acclimation of ion regulatory capacities in gills of marine fish under environmental hypercapnia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R1660–R1670, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ecelbarger CA, Terris J, Hoyer JR, Nielsen S, Wade JB, Knepper MA. Localization and regulation of the rat renal Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter, BSC-1. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 271: F619–F628, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farrell J, Ramos L, Tresguerres M, Kamenetsky M, Levin LR, Buck J. Somatic “soluble” adenylyl cyclase isoforms are unaffected in Sacytm1Lex /Sacytm1Lex “knockout” mice. PLoS ONE 3: e3251, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Field M, Karnaky KJ, Smith PL, Bolton JE, Kinter WB. Ion transport across the isolated intestinal mucosa of the winter flounder, Pseudopleuronectes americanus. J Membr Biol 41: 265–293, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Field M, Smith PL, Bolton JE. Ion transport across the isolated intestinal mucosa of the winter flounder, Pseudopleuronectes americanus: II. Effects of cyclic AMP. J Membr Biol 55: 157–163, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frizzell RA, Halm DR, Musch MW, Stewart CP, Field M. Potassium transport by flounder intestinal mucosa. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 246: F946–F951, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frizzell RA, Smith PL, Vosburgh E, Field M. Coupled sodium-chloride influx across brush border of flounder intestine. J Membr Biol 46: 27–39, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gamba G, Friedman P. Thick ascending limb: the Na+-K+-2Cl− co-transporter, NKCC2, and the calcium-sensing receptor, CaSR. Pflügers Arch 458: 61–76, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geng W, Wang Z, Zhang J, Reed BY, Pak CY, Moe OW. Cloning and characterization of the human soluble adenylyl cyclase. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 288: C1305–C1316, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gimenez I, Forbush B. Short-term stimulation of the renal Na-K-Cl cotransporter (NKCC2) by vasopressin involves phosphorylation and membrane translocation of the protein. J Biol Chem 278: 26946–26951, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greger R. Ion transport mechanisms in thick ascending limb of Henle's loop of mammalian nephron. Physiol Rev 65: 760–797, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grosell M. Intestinal anion exchange in marine fish osmoregulation. J Exp Biol 209: 2813–2827, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grosell M, Genz J, Taylor JR, Perry SF, Gilmour KM. The involvement of H+-ATPase and carbonic anhydrase in intestinal HCO3− secretion in seawater-acclimated rainbow trout. J Exp Biol 212: 1940–1948, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grosell M, Mager EM, Williams C, Taylor JR. High rates of HCO3− secretion and Cl− absorption against adverse gradients in the marine teleost intestine: the involvement of an electrogenic anion exchanger and H+-pump metabolon? J Exp Biol 212: 1684–1696, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grosell M, Taylor JR. Intestinal anion exchange in teleost water balance. Comp Biochem Physiol A 148: 14–22, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hallows KR, Wang HM, Edinger RS, Butterworth MB, Oyster NM, Li H, Buck J, Levin LR, Johnson JP, Pastor-Soler NM. Regulation of epithelial Na+ transport by soluble adenylyl cyclase in kidney collecting duct cells. J Biol Chem 284: 5774–5783, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hess KC, Jones BH, Marquez B, Chen Y, Ord TS, Kamenetsky M, Miyamoto C, Zippin JH, Kopf GS, Suarez SS, Levin LR, Williams CJ, Buck J, Moss SB. The “soluble” adenylyl cyclase in sperm mediates multiple signaling events required for fertilization. Dev Cell 9: 249–259, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hiroi J, McCormick SD. Variation in salinity tolerance, gill Na+/K+-ATPase, Na+/K+/2Cl− cotransporter and mitochondria-rich cell distribution in three salmonids Salvelinus namaycush, Salvelinus fontinalis and Salmo salar. J Exp Biol 210: 1015–1024, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kamenetsky M. Mammalian Cells Possess Multiple Distinctly Regulated cAMP Signaling Cascades ( PhD thesis). New York: Weill Cornell Medical College, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaplan MR, Plotkin MD, Lee WS, Xu ZC, Lytton J, Hebert SC. Apical localization of the Na-K-Cl cotransporter, rBSC1, on rat thick ascending limbs. Kidney Int 49: 40–47, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurita Y, Nakada T, Kato A, Doi H, Mistry AC, Chang MH, Romero MF, Hirose S. Identification of intestinal bicarbonate transporters involved in formation of carbonate precipitates to stimulate water absorption in marine teleost fish. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 294: R1402–R1412, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227: 680–685, 1970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lorin-Nebel C, Boulo V, Bodinier C, Charmantier G. The Na+/K+/2Cl− cotransporter in the sea bass Dicentrarchus labrax during ontogeny: involvement in osmoregulation. J Exp Biol 209: 4908–4922, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lytle C, Xu JC, Biemesderfer D, Forbush B., III Distribution and diversity of Na-K-Cl cotransport proteins: a study with monoclonal antibodies. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 269: C1496–C1505, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manning EC, Machen TE. Effects of bicarbonate and pH on chloride transport by gastric mucosa. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 243: G60–G68, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marshall WS, Howard JA, Cozzi RRF, Lynch EM. NaCl and fluid secretion by the intestine of the teleost Fundulus heteroclitus: involvement of CFTR. J Exp Biol 205: 745–758, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McDonald MD, Grosell M, Wood CM, Walsh PJ. Branchial and renal handling of urea in the gulf toadfish, Opsanus beta: the effect of exogenous urea loading. Comp Biochem Physiol A 134: 763–776, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meade P, Hoover RS, Plata C, Vazquez N, Bobadilla NA, Gamba G, Hebert SC. cAMP-dependent activation of the renal-specific Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter is mediated by regulation of cotransporter trafficking. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284: F1145–F1154, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Musch MW, O'Grady SM, Field M, Sidney F, Becca F. Ion transport of marine teleost intestine. In: Methods in Enzymology. Orlando, FL: Academic, 1990, p. 746–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Musch MW, Orellana SA, Kimberg LS, Field M, Halm DR, Krasny EJ, Frizzell RA. Na+ -K+ -Cl− co-transport in the intestine of a marine teleost. Nature 300: 351–353, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nielsen S, Maunsbach AB, Ecelbarger CA, Knepper MA. Ultrastructural localization of Na-K-2Cl cotransporter in thick ascending limb and macula densa of rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 275: F885–F893, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nonotte L, Nonnotte G, Leray C. Morphological changes in the middle intestine of the rainbow trout, Salmo gairdneri, induced by a hyperosmotic environment. Cell Tissue Res 243: 619–628, 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Grady SM. Cyclic nucleotide-mediated effects of ANF and VIP on flounder intestinal ion transport. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 256: C142–C146, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Grady SM, Field M, Nash NT, Rao MC. Atrial natriuretic factor inhibits Na-K-Cl cotransport in teleost intestine. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 249: C531–C534, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O'Grady SM, Palfrey HC, Field M. Na-K-2Cl cotransport in winter flounder intestine and bovine kidney outer medulla: [3H] bumetanide binding and effects of furosemide analogues. J Membr Biol 96: 11–18, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oide M. Role of alkaline phosphatase in intestinal water absorption by eels adapted to sea water. Comp Biochem Physiol A 46: 639–645, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Orlov SN, Hamet P. Intracellular monovalent ions as second messengers. J Membr Biol 210: 161–172, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ortiz PA. cAMP increases surface expression of NKCC2 in rat thick ascending limbs: role of VAMP. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F608–F616, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pastor-Soler N, Beaulieu V, Litvin TN, Da Silva N, Chen YQ, Brown D, Buck J, Levin LR, Breton S. Bicarbonate-regulated adenylyl cyclase (sAC) is a sensor that regulates pH-dependent V-ATPase recycling. J Biol Chem 278: 49523–49529, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Payne JA, Forbush B. Alternatively spliced isoforms of the putative renal Na-K-Cl cotransporter are differentially distributed within the rabbit kidney. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 4544–4548, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Payne JA, Xu JC, Haas M, Lytle CY, Ward D, Forbush B., III Primary structure, functional expression, and chromosomal localization of the bumetanide-sensitive Na-K-Cl Cotransporter in human colon. J Biol Chem 270: 17977–17985, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ramos LS, Zippin JH, Kamenetsky M, Buck J, Levin LR. Glucose and GLP-1 stimulate cAMP production via distinct adenylyl cyclases in INS-1E insulinoma cells. J Gen Physiol 132: 329–338, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rao MC, Nash NT, Field M. Differing effects of cGMP and cAMP on ion transport across flounder intestine. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 246: C167–C171, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rolston DDK, Kelly MJ, Borodo MM, Dawson AM, Farthing MJG. Effect of bicarbonate, acetate, and citrate on water and sodium movement in normal and cholera toxin-treated rat small intestine. Scand J Gastroenterol 24: 1–8, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Simmonneaux V, Humbert W, Kirsch R. Structure and osmoregulatory functions of the intestinal folds in the seawater eel, Anguilla anguilla. J Comp Physiol B 158: 45–55, 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sladen GE, Dawson AM. Effect of bicarbonate on sodium absorption by the human jejunum. Nature 218: 267–268, 1968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Steegborn C, Litvin TN, Hess KC, Capper AB, Taussig R, Buck J, Levin LR, Wu H. A novel mechanism for adenylyl cyclase inhibition from the crystal structure of its complex with catechol estrogen. J Biol Chem 280: 31754–31759, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Steegborn C, Litvin TN, Levin LR, Buck J, Wu H. Bicarbonate activation of adenylyl cyclase via promotion of catalytic active site closure and metal recruitment. Nat Struct Mol Biol 12: 32–37, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sterling D, Casey JR. Bicarbonate transport proteins. Biochem Cell Biol 80: 483–497, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takei Y, Yuge S. The intestinal guanylin system and seawater adaptation in eels. Gen Comp Endocrinol 152: 339–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Taylor JR, Mager EM, Grosell M. Basolateral NBCe1 plays a rate-limiting role in transepithelial intestinal HCO3− secretion, contributing to marine fish osmoregulation. J Exp Biol 213: 459–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tresguerres M, Katoh F, Fenton H, Jasinska E, Goss GG. Regulation of branchial V-H+-ATPase Na+/K+-ATPase and NHE2 in response to acid and base infusions in the Pacific spiny dogfish (Squalus acanthias). J Exp Biol 208: 345–354, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tresguerres M, Parks SK, Goss GG. V-H+-ATPase, Na+/K+-ATPase and NHE2 immunoreactivity in the gill epithelium of the Pacific hagfish (Epatretus stoutii). Comp Biochem Physiol A 145: 312–321, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tresguerres M, Parks SK, Sabatini SE, Goss GG, Luquet CM. Regulation of ion transport by pH and [HCO3−] in isolated gills of the crab Neohelice (Chasmagnathus) granulata. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 294: R1033–R1043, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tresguerres M, Parks SK, Salazar E, Levin LR, Goss GG, Buck J. Bicarbonate-sensing soluble adenylyl cyclase is an essential sensor for acid/base homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 442–447, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wilson RW, Millero FJ, Taylor JR, Walsh PJ, Christensen V, Jennings S, Grosell M. Contribution of fish to the marine inorganic carbon cycle. Science 323: 359–362, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wilson RW, Wilson JM, Grosell M. Intestinal bicarbonate secretion by marine teleost fish–why and how? Biochim Biophys Acta 1566: 182–193, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xu JC, Lytle C, Zhu TT, Payne JA, Benz E, Forbush B. Molecular cloning and functional expression of the bumetanide-sensitive Na-K-Cl cotransporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 2201–2205, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zippin JH, Farrell J, Huron D, Kamenetsky M, Hess KC, Fischman DA, Levin LR, Buck J. Bicarbonate-responsive “soluble” adenylyl cyclase defines a nuclear cAMP microdomain. J Cell Biol 164: 527–534, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zippin JH, Levin LR, Buck JC. O2/HCO3−-responsive soluble adenylyl cyclase as a putative metabolic sensor. Trends Endocrinol Metab 12: 366–370, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]