Abstract

Diabetes is associated with significantly accelerated rates of several debilitating microvascular complications such as nephropathy, retinopathy, and neuropathy, and macrovascular complications such as atherosclerosis and stroke. While several studies have been devoted to the evaluation of genetic factors related to type 1 and type 2 diabetes and associated complications, much less is known about epigenetic changes that occur without alterations in the DNA sequence. Environmental factors and nutrition have been implicated in diabetes and can also affect epigenetic states. Exciting research has shown that epigenetic changes in chromatin can affect gene transcription in response to environmental stimuli, and changes in key chromatin histone methylation patterns have been noted under diabetic conditions. Reports also suggest that epigenetics may be involved in the phenomenon of metabolic memory observed in clinic trials and animal studies. Further exploration into epigenetic mechanisms can yield new insights into the pathogenesis of diabetes and its complications and uncover potential therapeutic targets and treatment options to prevent the continued development of diabetic complications even after glucose control has been achieved.

Keywords: diabetes, metabolic memory, hyperglycemia, diabetic kidney disease

diabetes is a chronic metabolic disease associated with both genetic and environmental factors. The worldwide epidemic of diabetes has greatly increased the cost of treating both the disease and its numerous debilitating complications. Both type 1 (T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) are associated with significantly accelerated rates of microvascular complications such as diabetic nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy, and macrovascular cardiovascular diseases such as atherosclerosis, hypertension, and stroke. Furthermore, diabetic nephropathy is associated with macrovascular diseases and can also ultimately lead to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and the need for dialysis and/or kidney transplantation. T1D is an autoimmune disease characterized by the loss of pancreatic β cells and insulin production, while T2D is associated with progressive insulin resistance and β cell dysfunction. Gestational diabetes arises from insulin resistance during pregnancy and can increase the risk for future development of T2D for both the mother and the child.

Genetic factors and key gene mutations have been implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetes. However, increasing evidence suggests that complex interactions between genes and the environment may play a major role in many common human diseases such as diabetes and its complications (88, 89, 91, 92, 142). Furthermore, the increased risk for the development of T2D with increasing age suggests the accumulation and operation of multiple factors, including the environment. Notably, chromatin is a crucial interface between the effects of genetics and environment, and the epigenetic posttranscriptional modifications (PTMs) of histone tails in chromatin have been linked to gene transcription. While several studies have identified key biochemical pathways triggered by hyperglycemia and diabetes in target cells related to diabetic complications, the role of epigenetic mechanisms are only now becoming apparent. Furthermore, although, both T1D and T2D can be controlled through medications, changes in dietary habits and increased exercise, subjects with diabetes continue to be plagued with numerous life-threatening complications. This continued development of diabetic complications even after achieving glucose control suggests a metabolic memory of prior glycemic exposure and indicates a missing link in diabetes etiology which recent studies have suggested may be attributed to epigenetic changes in target cells without alterations in gene coding sequences. Exploring a role for epigenetics in diabetic complications could allow for new insights clarifying the interplay between the environment and gene regulation and identify much needed new therapeutic targets.

Diabetic Kidney Disease

Diabetic nephropathy is one of the major complications associated with both T1D and T2D diabetes. It is associated with abnormalities in several renal cells, including mesangial and tubular cells and podocytes, and characterized by proteinuria, glomerular dysfunction, thickening of the glomerular and basement membranes, mesangial expansion and hypertrophy, and accumulation of ECM in leading to fibrosis or scarring (9, 59, 67, 117, 118, 155). Even when blood glucose levels are under control, diabetic patients may still develop chronic kidney disease, leading to renal failure. Diabetes is one of the leading causes of progressive renal failure and ESRD. Current treatment modalities include blood glucose and blood pressure control and treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) to reduce hypertension, proteinuria, and slow down the progression of renal failure. The pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy is associated with altered signaling pathways in multiple renal cell types, as well as cross talk between these pathways, resulting in a complex multifactorial disease, a better understanding of which would greatly enable the development of new prevention tactics and treatment options (18).

While diabetes is an important risk factor for ESRD, not all diabetic patients go into kidney failure, nor do they progress at the same rate. In addition, kidney disease can present itself in nondiabetic patients. High blood pressure, various glomerular diseases, polycystic kidney disease, as well as other autoimmune diseases can result in chronic kidney disease. Both diabetic and nondiabetic kidney diseases are associated with proteinuria, hypertension, and decreased glomerular filtration rates. Overall, most of the current best treatment options for renal dysfunction rely on the use of limited available medications known to delay the progression toward renal failure with hopes of avoiding the costly, time-consuming, debilitating, and life-threatening possibilities of dialysis and/or kidney transplantation. New therapeutic targets would therefore be greatly beneficial in facilitating the development of sorely needed treatments for diabetic renal diseases.

Biochemical and Cellular Signaling Mechanisms Underlying Diabetic Complications

Hyperglycemia has been shown to be the major risk factor for the development of diabetic complications due its long-term deleterious effects on various tissues and organs. Hyperglycemia can lead to the activation of several cellular pathways, including increased oxidant stress (13, 19, 30), enhanced flux into the polyol and hexosamine pathways (19), activation of PKC (63) and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β-SMAD-MAPK signaling pathways (67, 129), and increased formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) (21, 74). Studies in mesangial, endothelial, and other cells have linked hyperglycemic activation of these pathways to increased mitochondrial superoxide anion formation and associated oxidant stress (20), which can ultimately lead to increased formation of ECM proteins in the kidney, contributing to renal dysfunction (18, 67). While superoxide anions may be short-lived, the resulting activation of downstream pathways can have long-lasting effects (20). In addition, high glucose can activate the proinflammatory transcription factor NF-κB, resulting in increased inflammatory gene expression in part through oxidant stress, AGEs, PKC, and MAPKs (34, 127, 128). Inflammation can also lead to the acceleration of diabetic complications due to detrimental effects on vascular cells, β cell function in T1D, and insulin resistance in T2D. In addition, insulin resistance has been attributed to increased free fatty acids which, in conjunction with hyperinsulinemia, lead to dyslipidemia (103). Consequently, hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia can also alter the expression of inflammatory and other pathological genes and proteins related to the development of both micro- and macrovascular complications of diabetes (75) (Fig. 1). However, the exact molecular mechanisms are still not very clear.

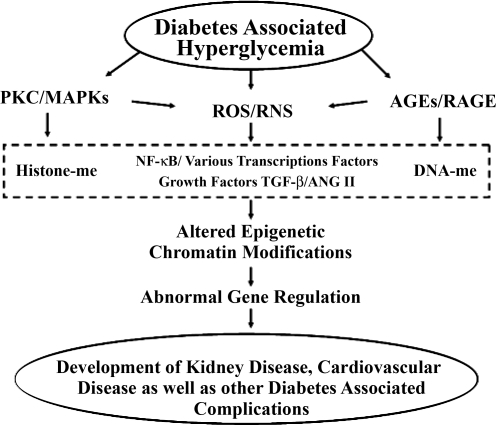

Fig. 1.

Hyperglycemia-induced activation of molecular pathways associated with diabetic complications. Diabetes and associated hyperglycemia can lead to increased activation of PKC, MAPKs, and downstream signaling, production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrative species (RNS), and formation of advanced glycation end products (AGE) and signaling through the receptor for AGE (RAGE). Each of these events can lead to production and increased action of various growth factors such as ANG II and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and activation of transcription factors such as NF-κB, changes in histone methylation (histone-me) patterns, and altered DNA methylation (DNA-me) at various genes in target cells, all of which over time can result in changes to the expression patterns of inflammatory, sclerotic, and other pathological genes and the ultimate development of diabetic complications.

Hyperglycemic or “Metabolic Memory”

The results of more than one clinical trial have suggested that the continued development of diabetic complications even after the achievement of glycemic control could be due to a metabolic memory stemming from prior hyperglycemic levels. T1D patients in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) under intensive insulin therapy were found to have delayed progression of nephropathy, retinopathy, and neuropathy compared with patients under conventional therapy (2). The profound benefits of the intensive therapy led to the premature termination of the DCCT so that all patients could be placed on intensive insulin therapy and followed long term under the subsequent Epidemiology of Diabetic Complications and Interventions Trial (EDIC). Long-term follow-up in the EDIC trial have demonstrated that patients who were originally in the intensive treatment group during the DCCT and continued on intensive therapy for the EDIC trial continue to have significantly slower progression of key diabetic microvascular complications such as nephropathy, retinopathy, and neuropathy relative to patients who were in the conventional treatment group during DCCT even though they were placed on intensive therapy and after the differences in glycosylated hemoglobin had normalized several years into the EDIC trial (1, 4, 114). More recently, patients in the continuous intensive treatment group since the beginning of the trials were found to also have better outcomes for macrovascular complications including stroke, nonfatal heart attack, or death by cardiovascular disease (107), as well as decreased progression of coronary artery calcification and intima-media thickness, both of which are associated with atherosclerosis (29, 32, 108).

Long-lasting benefits of glycemic control have also been seen in T2D patients. The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) found that lower fasting plasma glucose at the time of diagnosis correlated with decreased cardiovascular risk (31, 58), and The Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Modified Release Controlled Evaluation (ADVANCE) trial found that that intensive glycemic control could help decrease both macro- and microvascular complications mostly due to a decrease in nephropathy (113). The Steno-2 Study, also on T2D patients, found a decreased risk of cardiovascular events and death by cardiovascular disease as well as decreased ESRD following intensive multifactorial therapy including, but not limited to, tight glycemic control (43).

Overall, the findings from these major clinical trials demonstrate the importance of early metabolic control to reduce long-term complications and confirm that hyperglycemia can have long-lasting detrimental consequences. It is also possible that postprandial hyperglycemic spikes may have long-term effects (23, 47). The mechanisms responsible for these enduring effects of the prior hyperglycemic state or erratic metabolic control are not still not well understood, and this phenomenon, termed metabolic memory (107), has been a major challenge in the treatment of diabetic complications.

Models of Metabolic Memory

Experimental models can provide an opportunity to study the molecular mechanisms responsible for metabolic memory to design better therapies for diabetic patients, and exciting research in recent years has demonstrated the metabolic memory phenomenon in several animal and cell culture models. Early pioneering studies in dogs found that there was a continuation of retinal complications even after reversal of hyperglycemia (38). Similar results with diabetic rats showed that islet transplantation after 12 wk of diabetes could not reverse the progression of retinopathy compared with islet transplantation after 6 wk of diabetes (50). Several studies in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats showed that establishment of glycemic control after a short period of hyperglycemia had protective effects on nitric oxide levels, lipid peroxides, and other parameters in the retina. However, reinstitution of normal glucose after prolonged diabetes and hyperglycemia in the rats failed to reverse increases in nitrative and overall oxidative stress, NF-κB activity, as well as inflammation, and this was attributed to metabolic memory (26, 78, 80, 81), Similar results were seen in the kidneys of STZ-injected rats (79).

Early in vitro studies with endothelial cells cultured in high glucose showed continued increased expression of genes encoding fibronectin and collagen ECM proteins even after normalization of glucose levels (122). Another recent endothelial cell model of metabolic memory showed that even a short-term exposure to high glucose resulted in sustained increases in the expression of the NF-κB p65 subunit, inflammatory genes, and oxidant stress that persisted even after a return to normal glucose levels (17, 37). Other recent reports demonstrated the persistence of oxidant stress for up to 1 wk after glucose normalization and that antioxidants or NADPH oxidase inhibitors partially blocked the high glucose effects (60, 61). Additional studies in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) derived from T2D, insulin-resistant, obese db/db mice have demonstrated a preactivated phenotype and metabolic memory of the prior glycemic state even after culturing in vitro for several passages. Relative to control VSMC from nondiabetic db/+ control littermates, cultured VSMC derived from diabetic db/db mice maintained a sustained increase in inflammatory gene expression, migration, and oxidant stress as well as increased activation of NF-κB and CREB transcription factors and key signaling pathways associated with growth and migration (85). Monocyte adhesion to VSMC from db/db mice was also enhanced relative to db/+ cells likely due to the increase in inflammatory chemokine production (85). Together, these results suggest a metabolic memory of vascular dysfunction arising from acute hyperglycemic spikes or prior chronic exposure to hyperglycemic conditions.

These experimental models further confirm that strict control of glucose levels is essential to slow down the progression of diabetic complications. They also suggest that oxidant stress may play an important role in perpetuating this metabolic memory by modifying or damaging essential lipids, proteins, and/or DNA (24, 60). Hyperglycemia and oxidant stress along with increased activity in the polyol pathway and downstream signaling can also increase the accumulation of AGEs, which can further perpetuate and amplify local inflammation and oxidant stress through irreversible glycation of the various proteins and lipids to promote long-term vascular and end-organ damage. Thus AGEs, acting through receptors such as RAGE, could also contribute to hyperglycemic memory (22, 97, 147). These studies have begun to provide insights into the biochemical and signaling aspects of metabolic memory and how it may adversely affect target tissues and organs susceptible to diabetic complications. However, the subtle molecular and nuclear mechanisms responsible for the sustained memory over time through multiple cell divisions at the transcriptional and epigenetic level need to be more carefully examined and have evolved as an exciting area of research.

Epigenetics and Transcriptional Regulation

Regulation of gene expression relies on the accessibility of DNA to various transcription factors, coactivators/corepressors, and the transcriptional machinery. DNA is first wrapped around a histone octamer composed of a histone H3-H4 tetramer and two H2A-H2B dimers followed by a histone H1 linker making up a nucleosome, the basic unit of chromatin (93). Apart from the binding of transcription factors to their cognate promoter cis-acting elements, transcriptional activation or repression is also linked to the recruitment of protein complexes that alter chromatin structure via enzymatic modifications of histone tails and nucleosome remodeling. Therefore, gene transcription and activation depend on a chromatin structure that is very dynamic depending on a multitude of posttranslational modifications of histones that allow for the conversion of inaccessible, compact, or repressive heterochromatin to the accessible or active euchromatin state of DNA. Posttranslational modifications that occur on the histone tails include acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation to name a few. Along with DNA methylation at CpG islands, these epigenetic modifications make up an added layer of gene regulation or code that can be altered without altering the DNA code itself. In addition, the numerous combinations of epigenetic modifications allow for flexibility of the chromatin and can affect recruitment and binding of various DNA and histone binding complexes that recognize specific combinations of chromatin marks. Histone binding complexes often contain other chromatin-modifying proteins that can further change the chromatin landscape. Cross-talk mechanisms have also been suggested where specific histone modifications can facilitate or block additional histone marks. Nucleosome-nucleosome interactions can then be disrupted, enabling chromatin to either open and facilitate transcription or to close and form a compact, silent conformation, thereby directing chromatin accessibility and the transcriptional outcome depending on the needs of the cells/tissues (66, 77, 136).

Histone acetyltransferases (HATs) mediate histone lysine acetylation, a chromatin mark generally associated with gene activation. Histone deacetylases (HDACs), on the other hand, mediate the removal of lysine acetylation. Most HATs have low specificity, being able to modify numerous lysine residues on both histone and nonhistone protein While histone lysine acetylation enables a more open chromatin structure allowing for transcription factor and RNA polymerase II recruitment permissible for transcription, HDACs are found to be components of repressor complexes or to be involved in various signaling pathways (77, 121). Overall, histone acetylation can occur quite rapidly and is quite dynamic.

Unlike acetylation, histone methylation is considered to be more stable and long lasting. Histone methylation occurs on both lysine and arginine residues and is associated with either gene activation or repression depending on which residue is modified. Protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs) are responsible for either mono- or dimethylation of arginine residues most often associated with gene activation (84). The SET domain-containing family of HMTs, which is named for a conserved sequence motif found in three Drosophila proteins, Suppressor of position effect variegation 3–9, Enhancer of zeste, and Trithorax, and the more recently described disruptor of telomeric silencing-1 (Dot1) or the human homolog DOT1L family of HMTs, which do not contain the classical SET domain, are involved in regulating lysine methylation (41, 96, 154). Lysine methylation can be quite complex since lysine residues can be mono-, di-, or trimethylated. HMTs are generally more specific, usually methylating only one particular lysine residue (77, 96, 154). Histone H3 lysine 4 methylation (H3K4me) is typically associated with gene activation and can be mediated by several HMTs such as SET1, MLL1–4 (mixed lineage leukemia 1–4), SMYD3 (SET and MYND domain containing 3), and SET7/9 (96, 123, 134). Histone H3 lysine 9 methylation (H3K9me), on the other hand, is generally associated with gene repression and can be mediated by SUV39H1 (Suppressor of variegation 3–9 homolog 1), G9a, and SETDB1/ESET (SET domain, bifurcated 1/ERG-associated protein with SET domain) (96, 134). In addition to these, there are several other lysines, including H3K27, H3K36, and H3K79, that can be methylated to various degrees by various HMTs, leading to altered gene expression (96). As an added layer of complexity, the region of the gene being modified whether the promoter or coding region, can also affect gene regulation, either activating or repressing transcription. In addition, having more than one HMT capable of modifying a specific residue may provide an opportunity for fine tuning gene expression levels via recruitment by various chromatin binding factors or as a backup plan for another essential HMT.

The exciting recent discovery of the first histone demethylase, lysine demethylase 1 (LSD1) which specifically removes H3K4me marks (133) and later also found capable of removing H3K9me (98), demonstrated that histone lysine methylation can also undergo dynamic regulation. Numerous lysine demethylases have since been identified with varying specificities for different histone lysine residues (134, 140, 145), the nomenclature for which has recently been changed to lysine demethylases (KDMs) (7). Understanding and characterizing these demethylases and the roles they may play in various diseases are now an area of great interest (132, 139). In the context of diabetes, the recent report demonstrating that histone demethylase JHDM2A is associated with obesity and affects genes related to metabolism in rodent models (138) is noteworthy. Even though histone lysine methylation is now known to be reversible, it is still one of the most stable epigenetic modifications, with some histone lysine methylation states maintaining very low turnover rates, and hence could be key factors in metabolic memory.

Epigenetics was originally thought of as the inheritance of traits not solely based on DNA sequence and has evolved substantially since its inception roughly 50 years ago. DNA methylation, which generally occurs at CpG islands, is the best characterized epigenetic modification that regulates gene expression and is inheritable. Recently, the term epigenetics has broadened rather than focusing so much on heredity, with a more all-encompassing and unifying definition as “the structural adaptation of chromosomal regions so as to register, signal or perpetuate altered activity states” (16). Histone modifications are now widely accepted to play a role in epigenetics; however, there are questions as to what role they specifically play. Histone modifications could precede or succeed DNA methylation, and whether they initiate the transcriptional memory or simply maintain it is still debated (14). In recent years, our understanding of these epigenetic mechanisms governing gene expression patterns without changes in the basic gene coding sequence has increased dramatically. However, the relationships to pathological and disease states such as diabetes and its complications are less clear and of much current interest.

DNA Methylation Under Diabetic Conditions

DNA methylation at promoter CpG islands has been associated with gene repression and is a well-studied epigenetic mark in the context of tumor suppressor genes and cancer (130). However, much less is known about DNA methylation in diabetes. A recent report has shown that the insulin promoter DNA was methylated in mouse embryonic stem cells and only becomes demethylated as the cells differentiate into insulin-expressing cells, and both the human and mouse insulin promoters were specifically demethylated in pancreatic β cells, suggesting epigenetic regulation of insulin expression (82). In the agouti mouse, DNA methylation and expression of the agouti gene can affect the tendency to develop obesity and diabetes (104). Another interesting recent study showed that intrauterine growth retardation can lead to T2D due to epigenetic silencing of Pdx1, a key transcription factor that regulates insulin gene expression and beta cell differentiation. Both histone modifications and DNA methylation were implicated (112). In another study, it was shown that, in diabetic islets, there was increased DNA methylation of the promoter of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) coactivator 1α gene (PPARGC1A), a factor that plays a key role in regulating mitochondrial genes and in the modulation of diabetes (88). Treatment of human myotubes with TNF-α or free fatty acids led to DNA hypermethylation of PPARGC1A surprisingly at non-CpG regions. Similar DNA hypermethylation was also noted in skeletal muscle from T2D subjects relative to normal controls (10).

DNA methylation has also been shown to be affected by the toxic uremic conditions associated with kidney failure. With chronic kidney disease (CKD), there is an increase in blood homocysteine levels which affects methyl transfer reactions by inhibiting DNA methyltransferases (36, 62). Inhibition of DNA methyltransferases would suggest DNA hypomethylation in patients with CKD, which is noted in some cases. However, the relationship between homocysteine and DNA methylation in CKD is more complex (36). Another study evaluated peripheral blood leukocytes obtained from three different groups of CKD patients compared with normal controls and demonstrated that there was global DNA hypermethylation associated with inflammation and increased mortality in CKD (135). Altered DNA methylation of cell cycle genes has been implicated in homocysteine-induced inhibition of endothelial growth (65). A link between homocysteine levels and atherogenesis has also been suggested (62, 149), and elevated homocysteine levels have been associated with increased risk for CVD in some cohorts (72).

A Role for microRNAs in Epigenetic Regulation

One of the fastest recently emerging areas of research involves the posttranscriptional regulation of gene expression through a recently discovered group of small RNAs or microRNAs (miRs). miRs are short, ∼22-nucleotide noncoding RNAs that normally bind the 3′-untranslated region of target mRNAs, leading to either posttranscriptional silencing and translational repression or RNA degradation (12, 73). miRs provide a rapid but reversible means of gene regulation, which also allows the cell/tissue/organism to respond to environmental stimuli without changing the DNA sequence itself. miRs have been identified as negative regulators in various pathways targeting signaling molecules, transcription factors, and numerous other enzymes and proteins. There is also the potential for miRs to target chromatin-modifying enzymes, resulting in epigenetic modifications affecting gene expression. Additionally, histone modifications and changes in chromatin structure could also affect transcription and expression of miRs (11). Therefore, miRs may themselves be epigenetically regulated. Furthermore, miRs and other noncoding RNAs can also interact with transcriptional coregulators and thereby further influence epigenetics and transcriptional regulation (83, 105).

Recent findings have demonstrated a critical role for miRs in various diseases. They have been found to play key roles in proliferation, differentiation, development, and in cancer, where they can act as oncogenes or tumor suppressors (12, 33, 73). miRs are associated with the regulation of genes relevant to insulin secretion, cholesterol biosynthesis, fat metabolism, and adipogenesis, crucial pathways in the pathogenesis of diabetes (55, 115, 116). miRs have also been implicated in TGF-β signaling related to the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy, with key miRs such as miR-192, miR-216a, miR-217, and miR-377 being upregulated in glomerular mesangial cells treated with TGF-β, or diabetic conditions, resulting in increased collagen and fibronectin expression (68–70, 144). Glomerular podocytes are critical for the maintenance of the filtration barrier in the kidney and preventing albuminuria. Dicer is a key enzyme involved in miR biogenesis, and interesting studies showed that podocyte-specific Dicer knockout mice depict significant increases in proteinuria, glomerular, and tubular injury, suggesting that miRs could play critical roles in kidney diseases (52, 57, 68, 131). The role of miRs and potential relationships to epigenetic mechanisms in diabetic complications are currently an area of great interest both as a means for understanding the molecular pathways leading to complications and for discovering new potential therapeutic targets.

Epigenetic Histone Modifications and Diabetic Complications

Exciting recent research has demonstrated a role for epigenetic histone modifications in diabetes and its complications. HATs and HDACs have been found to play important roles in the regulation of several key genes linked to diabetes, as reviewed by Gray and De Meyts (48). Interestingly, the sirtuin (SIRT) family of deacetylases, specifically SIRT1, has been found to regulate several factors involved in metabolism, adipogenesis, and insulin secretion (87). HATs and HDACs can also modulate NF-κB transcriptional activity (8, 46), resulting in changes in downstream inflammatory gene expression levels (64, 141). Interestingly, high glucose treatment of cultured monocytes increased recruitment of the HATs CPB and p/CAF, leading to increased histone lysine acetylation at the cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and TNF-α inflammatory gene promoters, with a corresponding increase in gene expression (99). The in vivo relevance of histone acetylation in diabetes and inflammation was shown by demonstrating increased histone lysine acetylation at these inflammatory gene promoters in monocytes from both T1D and T2D patients relative to healthy control volunteers (99). Another study demonstrated that oxidized lipids can lead to increased inflammatory gene promoter histone acetylation in a CREB/p300 (HAT)-dependent manner, with a corresponding increase in gene expression (120). p300 was also found to play a role in oxidative stress-induced poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) and NF-κB signaling pathways in high glucose-treated endothelial cells and diabetic retina, kidney, and heart, leading to increases in ECM components related to diabetic complications (71, 146). Further studies demonstrated that high glucose increased p300, leading to increased histone acetylation at promoters of key ECM genes and vasoactive factors in endothelial cells (28). Interestingly, the p300 inhibitor curcumin could prevent hyperglycemia-induced changes in gene expression levels associated with diabetic vascular complications and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy (28, 40). These results further implicate a role for chromatin histone acetylation in promoting gene expression related to diabetic complications.

Reports show that histone lysine acetylation of the insulin gene promoter region was specific to islet-derived precursor cells and β cells (25, 106), and this correlated with p300 HAT recruitment (25). The insulin promoter region also exhibited increased H3K4me (25, 106) and recruitment of the HMT SET7/9 (25), while H3K9me was undetectable (106). This pattern of active epigenetic histone modifications seemed characteristic of the insulin gene promoter only in cells associated with insulin production compared with other non-insulin-producing cell types (25, 106). In vitro studies with HDAC inhibitors in rat pancreatic cells have also suggested the essential role of histone lysine acetylation in pancreatic development (54).

Further in vitro and in vivo studies in diabetic kidneys have shown an important role for HDACs in TGF-β1-mediated ECM production and kidney fibrosis. Trichostatin A (TSA), a HDAC inhibitor, blocked TGF-β1 induction of key fibrotic genes (111). TSA also blocked TGF-β1-mediated downregulation of E-cadherin and associated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in renal epithelial cells (111, 148). Knockdown of HDAC2 had the same effect as TSA treatment, which was found to be mediated by reactive oxygen species (111). Overall, these studies demonstrate a role for HDACs in the pathogenesis of renal fibrosis and TGF-β1 actions related to models of chronic renal injury, including diabetic nephropathy, by silencing key protective genes in the kidney. Since lysine acetylation is generally thought to be one of the relatively more transient histone modifications, it is not clear whether histone lysine acetylation/deacetylation plays a significant role in hyperglycemic memory.

Histone methylation, on the other hand, can be generally more stable and there has been great interest in determining the role for key histone methylation marks in diabetes, its complications, and in metabolic memory. Genome-wide location analyses with chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) coupled to a DNA microarray (ChIP-on-chip) technique was used to analyze changes in histone methylation patterns in cells under normal vs. diabetic conditions. ChIP-on-chip studies demonstrated dynamic changes in both the H3K4me2-activation mark and H3K9me2-repressive mark in cultured monocytes treated with high glucose, verifying a role for hyperglycemia in altered histone methylation patterns with relevant changes also seen in monocytes from diabetic patients (102). Cell type-specific histone methylation patterns have been identified by comparing primary human blood monocytes to lymphocytes, and these distinctive patterns have been found to be relatively stable within the cell type regardless of age or gender (101). Follow-up studies with blood cells from T1D patients and normal controls using both human cDNA and promoter tiling arrays in the ChIP-on-chip revealed a subset of genes in diabetic lymphocytes with increased H3K9me2. Pathway analysis of the methylated genes linked them to immune and inflammatory pathways often associated with the development of T1D and resulting complications (100). These epigenomic profiling studies suggest that, while a reasonably stable histone methylation pattern is maintained in healthy individuals over time in a cell type-specific setting, this pattern can be disrupted in a disease state. Moreover, they also provide a glimpse of the inflammatory cell epigenome under the diabetic state and suggest that new information about diabetes, its complications, and metabolic memory can be obtained by such profiling approaches.

Additional in vitro experiments have helped elucidate the mechanisms responsible for aberrant epigenetic histone methylation occurring under diabetic conditions. Knockdown of the H3K4 HMT SET7/9 in monocytes attenuated TNF-α induction of key inflammatory genes in an NF-κB-dependent manner. Knockdown of SET7/9 also decreased NF-κB p65 subunit and p300 HAT occupancies at monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and TNF-α promoters in monocytes, with a corresponding decrease in promoter H3K4me. These results suggest that SET7/9 might coactivate NF-κB transcriptional activity via promoter H3K4me activation in response to inflammatory stimuli prevalent in the diabetic milieu (86). Similarly, a role for SET7/9 in regulating NF-κB expression and inflammatory gene expression in response to high glucose was also shown in endothelial cells (17, 37).

Studies have also demonstrated the association of epigenetic histone modifications in models of diabetic cardiomyopathy and glomerulosclerosis (44, 126). Studies in kidney collecting ducts have demonstrated dynamic regulation of H3K79 methylation involved in fluid reabsorption essential for blood pressure control and electrolyte homeostasis (150–153). While Dot 1-mediated H3K79 hypermethylation was associated with gene repression, hypomethylation at the promoter of the epithelial sodium channel led to increased gene transcription in response to aldosterone signaling (152). SIRT1 was also found in the repressive complex responsible for H3K79 hypermethylation, although SIRT1 deacetylase activity did appear to be required for transcriptional silencing (153). The role of histone methylation in CKD is not well studied, and it would be of great interest to see whether specific gene promoter histone methylation patterns were altered in renal cells under diabetic conditions. Such changes might explain some aspects of CKD and the metabolic memory of diabetic renal disease as well as renal dysfunction that seem to persist even after treatment with drugs or glycemic control.

Potential Epigenetic Mechanisms for Metabolic Memory

A number of recent studies have provided new insights and suggested that chromatin-based epigenetic mechanisms may be responsible for metabolic memory. VSMC derived from aortas of diabetic db/db mice and cultured ex vivo for several passages continued to exhibit increased inflammatory gene expression associated with the diabetic phenotype and complications compared with VSMC from nondiabetic db/+ control mice (85, 143). This corresponded to decreased H3K9me3-repressive marks at the promoters of key inflammatory genes IL-6, macrophage colony stimulation factor (MCSF), and MCP-1 in the VSMC derived from diabetic mice relative to control cells. Interestingly, this loss of repressive H3K9me3 in db/db VSMC was associated with decreased protein levels of Suv39h1, a known HMT mediating H3K9me3 and associated with repressed states of chromatin. Overexpression of Suv39h1 in the diabetic db/db VSMC partially reversed the diabetic phenotype, thus verifying a negative role for Suv39h1 in inflammatory gene expression. VSMC from db/db mice also exhibited increased TNF-α-induced IL-6, MCSF, and MCP-1 expression, with corresponding sustained decreases in promoter H3K9me3 and Suv39h1 occupancy at these gene promoters. Normal human VSMC treated with high glucose demonstrated similar changes in chromatin lysine methylation, suggesting that the persistent alteration of these epigenetic marks could be due to the prior exposure to a hyperglycemic environment in the diabetic db/db mice (143). These results indicate a sustained loss of chromatin-repressive mechanisms in the diabetic state that might be responsible, at least in part, for metabolic memory.

Interestingly, even short-term hyperglycemic conditions were found to induce long-term changes in chromatin modifications. Endothelial cells cultured for up to 6 days in normal glucose after 16 h of short-term high glucose depicted a sustained increase in the expression of the NF-κB p65 subunit and inflammatory genes MCP-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1. The increase in p65 corresponded to increased H3K4me1 modifications on the p65 proximal promoter as well as increased Set7 (also known as SET7/9) recruitment (17, 37). Interestingly, these epigenetic changes could be prevented by reducing mitochondrial superoxide production (by overexpressing uncoupling protein-1 or manganese superoxide dismutase) or by overexpressing glyoxalase 1, an enzyme that degrades highly reactive dicarbonyls such as methylglyoxal known to accumulate under hyperglycemic conditions (37). In addition, supportive animal studies demonstrated that mice exposed to short-term hyperglycemia followed by glucose normalization displayed sustained increases in promoter H3K4me1 and p65 expression in aortic endothelial cells (37). It is likely that similar epigenetic changes also occur in cells such as retinal pericytes and endothelial cells, or renal mesangial cells, tubules, and podoctyes that are involved in common diabetic complications, retinopathy and nephropathy. Overall, these results indicate that prior exposure to hyperglycemia and even periods of transient high glucose or metabolic control can lead to epigenetic changes in target cells, altering chromatin structure and resulting in long-lasting repercussions for gene expression levels associated with the pathology of diabetic micro- and macrovascular complications (Fig. 2).

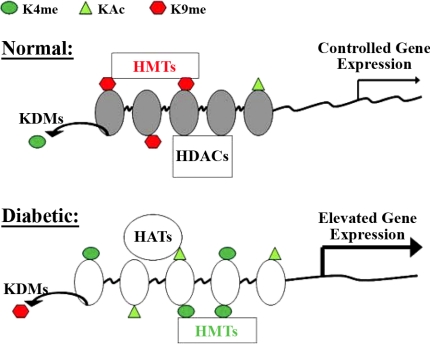

Fig. 2.

Model for epigenetic regulation of pathological gene expression in diabetes via changes in chromatin histone modifications. Posttranslational modifications on the N-terminal histone tails in chromatin play essential roles in gene regulation and are regulated by various chromatin modifiers. Histone lysine methyltransferases (HMTs) and lysine demethylases (KDMs) regulate histone lysine methylation (Kme), while histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs) control histone acetylation (Ac). In the proposed model shown, various chromatin modifiers maintain sufficient levels of repressive histone marks to maintain strict control of pathological gene expression under normal conditions; these would include methylation of H3K9 and demethylation of H3K4 in addition to deacetylation by HDACs. However, under diabetic conditions, including hyperglycemia, the negative regulators such as H3K9 methylation marks of repressed chromatin would be lost, while positive regulators or activating histone marks such as H3K4 methylation and histone acetylation may be increased, thus leading to relaxation or opening of the chromatin structure around key pathological genes to increase their transcription. Various combinations of histone modifications are likely to be involved.

Transmission of Epigenetic Modifications

Several clinical trials and animal studies have demonstrated that diabetic complications can persist despite glucose control, indicating a memory of the prior glycemic state. Active research is beginning to shed light on some of the possible cellular and molecular mechanisms responsible for this phenomenon. Hyperglycemia has been shown to increase PKC, AGEs, oxidant stress, and downstream pathological effects, including inflammation. Only recently has there been evidence linking epigenetic chromatin changes to these events. Current studies indicate a role for histone lysine methylation in metabolic memory; however, the next challenge is to understand how these histone modifications or other epigenetic marks are transmitted through multiple cell cycles. While much is known about the epigenetic inheritance of DNA methylation, the exact mechanisms responsible for the stable transmission of histone modifications are less well understood. Replication-associated transmission, histone variants, and chromatin remodeling complexes are some of the factors that have been implicated.

In some cases, methylation of histone lysine residues has been shown to be transmitted through replication where the methyl-CpG binding protein recruits H3K9 HMT SETDB1 to chromatin during replication to methylate newly deposited histones and thereby couple the transmission of histone lysine 9 methylation with DNA methylation (125). Evidence has also shown that the long-term silencing Polycomb complex also remains bound to chromatin during replication, possibly binding more than one nucleosome and allowing nucleosomes to maintain contact with chromatin even as the replication fork passes through (42). Alternatively, the Polycomb complex could interact directly with the replication machinery (42).

Another study demonstrated that the Polycomb repressive complex 2 containing the H3K27 HMT EZH2 can bind H3K27me3 modifications at sites of ongoing replication, which would then allow transmission or copying of the parental H3K27 methyl marks to the new histones deposited on the daughter strand (51). Recently, the Polycomb complex family has been found to play a role in epigenetic regulation of pancreatic β cell regeneration associated with diabetes and aging (27, 35).

Histone variant assembly into the nucleosome can alter nucleosome-nucleosome and nucleosome-protein interactions, leading to changes in chromatin structure and ultimately affecting gene transcription (5, 39, 49). Additionally, histone variants can also be posttranscriptionally modified similar to canonical histones (56) and have been proposed to play a role in establishing and maintaining epigenetic memory (49, 56, 109).

Chromatin remodeling can occur through the actions of various ATP-dependent remodeling complexes. This is thought to occur via disruption of DNA-histone interactions either by altering, relocating, or replacing the nucleosomes (76, 95). Chromatin-remodeling enzymes have been identified in complex with various histone-modifying proteins such as HATs, HDACs, HMTs, as well as DNA methyltransferases (45, 53, 95, 110). Interestingly, chromatin-remodeling enzymes have been shown to be involved in the induction of PPARγ during adipogenesis (124). Mutations in the Chd2 chromatin-remodeling enzyme significantly impaired glomerular function in mice, implicating remodeling enzymes in kidney disease (94). Together, these results highlight the need for further investigation into the mechanisms by which diabetes-induced changes in epigenetic modifications and epigenomic patterns might be stably transmitted through cell replications to establish a transcriptional or metabolic memory associated with diabetic complications.

Conclusions

Epigenetic regulation of chromatin is a dynamic process which enables another layer of control over gene expression so that genes can be turned off or on depending on the needs of the cell in response to various signaling pathways and environmental stimuli. Epigenetic modifications have also been found to play an important role in altering gene expression patterns associated with various diseases (92). Clinical as well as experimental studies with animal and cells models have clearly demonstrated the deleterious effects of hyperglycemia and the importance of maintaining good glucose control to prevent the onset or severity of diabetic complications. In addition, evidence shows that hyperglycemia can induce epigenetic changes to the chromatin structure via activation of various factors and signaling pathways. This has implicated specific key HMTs and KDMs related to active and repressed chromatin states and has demonstrated epigenetic regulation of key inflammatory genes in vascular cells. It is highly likely that other HMTs and KDMs, DNA methylation, and related chromatin factors are also involved in epigenetic changes induced by elevated glucose in multiple target organs and cells and contribute to metabolic memory of several debilitating diabetic complications (Fig. 3). However, diabetes is much more complicated than a simple state of hyperglycemia. It is associated with several risk factors and, in particular, T2D involves insulin resistance, obesity, dyslipidemia, environmental factors, nutrition, lifestyle, and genetics, in addition to hyperglycemia. Each of these risk factors could in itself induce epigenetic changes to the chromatin structure, ultimately altering gene expression patterns in conjunction with elevated glucose in various target tissues including kidney, heart, liver, retina, nervous system, muscle, blood vessels, and blood cells.

Fig. 3.

Scheme for the role of epigenetic mechanisms downstream of hyperglycemia in leading to diabetic complications. Diabetic conditions or hyperglycemia can activate several signal transduction pathways and transcription factors that can lead to sustained expression of pathological genes in the nucleus by cooperating with epigenetic factors. This can occur via a loss of repression and a corresponding gain in activation pathways, leading to long-lasting epigenetic changes through gene promoter histone lysine modifications near key transcription factor binding sites or other important chromatin regions. Depending on the specific lysine residue that is methylated, histone lysine methylation is associated with either gene activation (H3K4me) or repression (H3K9me). Modifications at other lysine residues may also be involved. These associations are further complicated by the gene location modified, either promoter or coding region, and the degree of methylation, all of which can affect accessibility of chromatin and transcriptional outcomes. These epigenetic modifications can be maintained through cell division via mechanisms that are not yet clearly understood but may include DNA methylation as well as transmission of histone lysine methylation marks. The persistence of these epigenetic changes might explain the metabolic memory phenomenon responsible for the continued development of diabetic complication even after glucose control has been achieved.

Alarming estimates indicate that the rates of diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and associated complications are rapidly increasing, and therefore additional strategies to curb these trends are needed. With respect to diabetic nephropathy, it is imperative to conduct further exploration into the epigenetic causes and related treatment options, given the widespread prevalence, and the rapid transition to ESRD despite the available therapies. Such information can complement the currently available and new genetic and molecular data to begin the development of personalized medicine for diabetic nephropathy (137) and other complications. Well-defined cell and animal models with and without treatments with standard diabetes drugs, antioxidants, and related interventions will further our understanding of diabetic complications and metabolic memory and how they might be prevented. Epigenetic drugs such as inhibitors of DNA methylation, HATs and HDACs, and some histone demethylases are already being evaluated for cancer and other diseases (6, 130, 132). Currently available drugs for diabetic complications (22) could be tested for their potential ability to alter epigenetic marks.

In recent years, there has been significant progress in the fields of epigenetics and epigenomics mainly due to increased understanding of basic molecular mechanisms and remarkable advances in powerful genome-wide technologies, instrumentation, and bioinformatics software. Thus massive, parallel next-generation sequencing and ChIP-sequencing have been used to simultaneously map several histone marks and DNA methylation in human adult and stem cells and have demonstrated associations with distinct cell and development states and gene transcription rates (90). A recent epigenomic analysis of histone methylation modifications in human pancreatic islets revealed key relationships with chromatin structure, gene expression, and epigenetic information relevant to diabetes (15). The Human Epigenome project is expected to greatly enhance our understanding of epigenetic states under normal and disease conditions (3, 119). The generally accepted idea is that the histone code is reversible, at least more so than the DNA code. Therefore, greater understanding of the epigenetic basis of disease could enable the discovery new therapeutic targets for the treatment of numerous human diseases, including diabetes and its complications.

GRANTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute) and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Writing Team DCCT/EDIC Research Group Effect of intensive therapy on the microvascular complications of type 1 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 287: 2563–2569, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DCCT Research Group The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development, and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. N Engl J Med 329: 977–986, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Human Epigenome Task Force Moving AHEAD with an international human epigenome project. Nature 454: 711–715, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.EDIC Study Sustained effect of intensive treatment of type 1 diabetes mellitus on development, and progression of diabetic nephropathy: the Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) study. JAMA 290: 2159–2167, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abbott DW, Laszczak M, Lewis JD, Su H, Moore SC, Hills M, Dimitrov S, Ausio J. Structural characterization of macroH2A containing chromatin. Biochemistry 43: 1352–1359, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aggarwal BB, Harikumar KB. Potential therapeutic effects of curcumin, the anti-inflammatory agent, against neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, pulmonary, metabolic, autoimmune and neoplastic diseases. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 41: 40–59, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allis CD, Berger SL, Cote J, Dent S, Jenuwien T, Kouzarides T, Pillus L, Reinberg D, Shi Y, Shiekhattar R, Shilatifard A, Workman J, Zhang Y. New nomenclature for chromatin-modifying enzymes. Cell 131: 633–636, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashburner BP, Westerheide SD, Baldwin AS., Jr The p65 (RelA) subunit of NF-kappaB interacts with the histone deacetylase (HDAC) corepressors HDAC1 and HDAC2 to negatively regulate gene expression. Mol Cell Biol 21: 7065–7077, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ayo SH, Radnik RA, Glass WF, 2nd, Garoni JA, Rampt ER, Appling DR, Kreisberg JI. Increased extracellular matrix synthesis and mRNA in mesangial cells grown in high-glucose medium. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 260: F185–F191, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barres R, Osler ME, Yan J, Rune A, Fritz T, Caidahl K, Krook A, Zierath JR. Non-CpG methylation of the PGC-1alpha promoter through DNMT3B controls mitochondrial density. Cell Metab 10: 189–198, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barski A, Jothi R, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Schones DE, Zhao K. Chromatin poises miRNA- and protein-coding genes for expression. Genome Res 19: 1742–1751, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136: 215–233, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baynes JW. Role of oxidative stress in development of complications in diabetes. Diabetes 40: 405–412, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berger SL, Kouzarides T, Shiekhattar R, Shilatifard A. An operational definition of epigenetics. Genes Dev 23: 781–783, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhandare R, Schug J, Le Lay J, Fox A, Smirnova O, Liu C, Naji A, Kaestner KH. Genome-wide analysis of histone modifications in human pancreatic islets. Genome Res 20: 428–433, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bird A. Perceptions of epigenetics. Nature 447: 396–398, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brasacchio D, Okabe J, Tikellis C, Balcerczyk A, George P, Baker EK, Calkin AC, Brownlee M, Cooper ME, El-Osta A. Hyperglycemia induces a dynamic cooperativity of histone methylase and demethylase enzymes associated with gene-activating epigenetic marks that coexist on the lysine tail. Diabetes 58: 1229–1236, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brosius FC, Khoury CC, Buller CL, Chen S. Abnormalities in signaling pathways in diabetic nephropathy. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab 5: 51–64, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brownlee M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature 414: 813–820, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brownlee M. The pathobiology of diabetic complications: a unifying mechanism. Diabetes 54: 1615–1625, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brownlee M, Cerami A, Vlassara H. Advanced glycosylation end products in tissue and the biochemical basis of diabetic complications. N Engl J Med 318: 1315–1321, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calcutt NA, Cooper ME, Kern TS, Schmidt AM. Therapies for hyperglycaemia-induced diabetic complications: from animal models to clinical trials. Nat Rev Drug Discov 8: 417–429, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ceriello A, Esposito K, Piconi L, Ihnat MA, Thorpe JE, Testa R, Boemi M, Giugliano D. Oscillating glucose is more deleterious to endothelial function and oxidative stress than mean glucose in normal and type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes 57: 1349–1354, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ceriello A, Ihnat MA, Thorpe JE. Clinical review 2: the “metabolic memory”: is more than just tight glucose control necessary to prevent diabetic complications? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94: 410–415, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chakrabarti SK, Francis J, Ziesmann SM, Garmey JC, Mirmira RG. Covalent histone modifications underlie the developmental regulation of insulin gene transcription in pancreatic beta cells. J Biol Chem 278: 23617–23623, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan PS, Kanwar M, Kowluru RA. Resistance of retinal inflammatory mediators to suppress after reinstitution of good glycemic control: novel mechanism for metabolic memory. J Diabetes Complications 24: 55–63, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen H, Gu X, Su IH, Bottino R, Contreras JL, Tarakhovsky A, Kim SK. Polycomb protein Ezh2 regulates pancreatic beta-cell Ink4a/Arf expression and regeneration in diabetes mellitus. Genes Dev 23: 975–985, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen S, Feng B, George B, Chakrabarti R, Chen M, Chakrabarti S. Transcriptional coactivator p300 regulates glucose induced gene expression in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 298: E127–E137, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cleary PA, Orchard TJ, Genuth S, Wong ND, Detrano R, Backlund JY, Zinman B, Jacobson A, Sun W, Lachin JM, Nathan DM. The effect of intensive glycemic treatment on coronary artery calcification in type 1 diabetic participants of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (DCCT/EDIC) Study. Diabetes 55: 3556–3565, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clempus RE, Griendling KK. Reactive oxygen species signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells. Cardiovasc Res 71: 216–225, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colagiuri S, Cull CA, Holman RR. Are lower fasting plasma glucose levels at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes associated with improved outcomes? UK prospective diabetes study 61. Diabetes Care 25: 1410–1417, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cooper ME. Metabolic memory: implications for diabetic vascular complications. Pediatr Diabetes 10: 343–346, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Croce CM, Calin GA. miRNAs, cancer, and stem cell division. Cell 122: 6–7, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Devaraj S, Glaser N, Griffen S, Wang-Polagruto J, Miguelino E, Jialal I. Increased monocytic activity and biomarkers of inflammation in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 55: 774–779, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dhawan S, Tschen SI, Bhushan A. Bmi-1 regulates the Ink4a/Arf locus to control pancreatic beta-cell proliferation. Genes Dev 23: 906–911, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ekstrom TJ, Stenvinkel P. The epigenetic conductor: a genomic orchestrator in chronic kidney disease complications? J Nephrol 22: 442–449, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.El-Osta A, Brasacchio D, Yao D, Pocai A, Jones PL, Roeder RG, Cooper ME, Brownlee M. Transient high glucose causes persistent epigenetic changes and altered gene expression during subsequent normoglycemia. J Exp Med 205: 2409–2417, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Engerman RL, Kern TS. Progression of incipient diabetic retinopathy during good glycemic control. Diabetes 36: 808–812, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fan JY, Rangasamy D, Luger K, Tremethick DJ. H2A.Z alters the nucleosome surface to promote HP1alpha-mediated chromatin fiber folding. Mol Cell 16: 655–661, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feng B, Chen S, Chiu J, George B, Chakrabarti S. Regulation of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in diabetes at the transcriptional level. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 294: E1119–E1126, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feng Q, Wang H, Ng HH, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Struhl K, Zhang Y. Methylation of H3-lysine 79 is mediated by a new family of HMTases without a SET domain. Curr Biol 12: 1052–1058, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Francis NJ, Follmer NE, Simon MD, Aghia G, Butler JD. Polycomb proteins remain bound to chromatin and DNA during DNA replication in vitro. Cell 137: 110–122, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gaede P, Lund-Andersen H, Parving HH, Pedersen O. Effect of a multifactorial intervention on mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 358: 580–591, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gaikwad AB, Sayyed SG, Lichtnekert J, Tikoo K, Anders HJ. Renal failure increases cardiac histone H3 acetylation, dimethylation, and phosphorylation and the induction of cardiomyopathy-related genes in type 2 diabetes. Am J Pathol 176: 1079–1083, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Geiman TM, Sankpal UT, Robertson AK, Zhao Y, Zhao Y, Robertson KD. DNMT3B interacts with hSNF2H chromatin remodeling enzyme, HDACs 1 and 2, and components of the histone methylation system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 318: 544–555, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gerritsen ME, Williams AJ, Neish AS, Moore S, Shi Y, Collins T. CREB-binding protein/p300 are transcriptional coactivators of p65. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 2927–2932, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Giugliano D, Ceriello A, Esposito K. Glucose metabolism and hyperglycemia. Am J Clin Nutr 87: 217S-–222S., 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gray SG, De Meyts P. Role of histone and transcription factor acetylation in diabetes pathogenesis. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 21: 416–433, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hake SB, Allis CD. Histone H3 variants and their potential role in indexing mammalian genomes: the “H3 barcode hypothesis”. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 6428–6435, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hammes HP, Klinzing I, Wiegand S, Bretzel RG, Cohen AM, Federlin K. Islet transplantation inhibits diabetic retinopathy in the sucrose-fed diabetic Cohen rat. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 34: 2092–2096, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hansen KH, Bracken AP, Pasini D, Dietrich N, Gehani SS, Monrad A, Rappsilber J, Lerdrup M, Helin K. A model for transmission of the H3K27me3 epigenetic mark. Nat Cell Biol 10: 1291–1300, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harvey SJ, Jarad G, Cunningham J, Goldberg S, Schermer B, Harfe BD, McManus MT, Benzing T, Miner JH. Podocyte-specific deletion of dicer alters cytoskeletal dynamics and causes glomerular disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 2150–2158, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hassan AH, Neely KE, Workman JL. Histone acetyltransferase complexes stabilize swi/snf binding to promoter nucleosomes. Cell 104: 817–827, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haumaitre C, Lenoir O, Scharfmann R. Histone deacetylase inhibitors modify pancreatic cell fate determination and amplify endocrine progenitors. Mol Cell Biol 28: 6373–6383, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heneghan HM, Miller N, Kerin MJ. Role of microRNAs in obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Obes Rev, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Henikoff S, Furuyama T, Ahmad K. Histone variants, nucleosome assembly and epigenetic inheritance. Trends Genet 20: 320–326, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ho J, Ng KH, Rosen S, Dostal A, Gregory RI, Kreidberg JA. Podocyte-specific loss of functional microRNAs leads to rapid glomerular and tubular injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 2069–2075, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 359: 1577–1589, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ihm CG, Lee GS, Nast CC, Artishevsky A, Guillermo R, Levin PS, Glassock RJ, Adler SG. Early increased renal procollagen alpha 1(IV) mRNA levels in streptozotocin induced diabetes. Kidney Int 41: 768–777, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ihnat MA, Thorpe JE, Ceriello A. Hypothesis: the ‘metabolic memory’, the new challenge of diabetes. Diabet Med 24: 582–586, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ihnat MA, Thorpe JE, Kamat CD, Szabo C, Green DE, Warnke LA, Lacza Z, Cselenyak A, Ross K, Shakir S, Piconi L, Kaltreider RC, Ceriello A. Reactive oxygen species mediate a cellular ‘memory’ of high glucose stress signalling. Diabetologia 50: 1523–1531, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ingrosso D, Perna AF. Epigenetics in hyperhomocysteinemic states. A special focus on uremia. Biochim Biophys Acta 1790: 892–899, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ishii H, Koya D, King GL. Protein kinase C activation and its role in the development of vascular complications in diabetes mellitus. J Mol Med 76: 21–31, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ito K, Hanazawa T, Tomita K, Barnes PJ, Adcock IM. Oxidative stress reduces histone deacetylase 2 activity and enhances IL-8 gene expression: role of tyrosine nitration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 315: 240–245, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jamaluddin MS, Yang X, Wang H. Hyperhomocysteinemia, DNA methylation and vascular disease. Clin Chem Lab Med 45: 1660–1666, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Translating the histone code. Science 293: 1074–1080, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kanwar YS, Wada J, Sun L, Xie P, Wallner EI, Chen S, Chugh S, Danesh FR. Diabetic nephropathy: mechanisms of renal disease progression. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 233: 4–11, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kato M, Arce L, Natarajan R. MicroRNAs and their role in progressive kidney diseases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1255–1266, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kato M, Putta S, Wang M, Yuan H, Lanting L, Nair I, Gunn A, Nakagawa Y, Shimano H, Todorov I, Rossi JJ, Natarajan R. TGF-beta activates Akt kinase through a microRNA-dependent amplifying circuit targeting PTEN. Nat Cell Biol 11: 881–889, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kato M, Zhang J, Wang M, Lanting L, Yuan H, Rossi J, Natarajan R. MicroRNA-192 in diabetic kidney glomeruli and its function in TGF-beta-induced collagen expression via inhibition of E-box repressors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 3432–3437, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kaur H, Chen S, Xin X, Chiu J, Khan ZA, Chakrabarti S. Diabetes-induced extracellular matrix protein expression is mediated by transcription coactivator p300. Diabetes 55: 3104–3111, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim M, Long TI, Arakawa K, Wang R, Yu MC, Laird PW. DNA methylation as a biomarker for cardiovascular disease risk. PloS one 5: e9692, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim VN, Han J, Siomi MC. Biogenesis of small RNAs in animals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10: 126–139, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim W, Hudson BI, Moser B, Guo J, Rong LL, Lu Y, Qu W, Lalla E, Lerner S, Chen Y, Yan SS, D'Agati V, Naka Y, Ramasamy R, Herold K, Yan SF, Schmidt AM. Receptor for advanced glycation end products and its ligands: a journey from the complications of diabetes to its pathogenesis. Ann NY Acad Sci 1043: 553–561, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.King GL. The role of inflammatory cytokines in diabetes and its complications. J Periodontol 79: 1527–1534, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Korber P, Horz W. SWRred not shaken; mixing the histones. Cell 117: 5–7, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell 128: 693–705, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kowluru RA. Effect of reinstitution of good glycemic control on retinal oxidative stress and nitrative stress in diabetic rats. Diabetes 52: 818–823, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kowluru RA, Abbas SN, Odenbach S. Reversal of hyperglycemia and diabetic nephropathy: effect of reinstitution of good metabolic control on oxidative stress in the kidney of diabetic rats. J Diabetes Complications 18: 282–288, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kowluru RA, Chakrabarti S, Chen S. Re-institution of good metabolic control in diabetic rats and activation of caspase-3 and nuclear transcriptional factor (NF-kappaB) in the retina. Acta Diabetol 41: 194–199, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kowluru RA, Kanwar M, Kennedy A. Metabolic memory phenomenon and accumulation of peroxynitrite in retinal capillaries. Exp Diabetes Res 2007: 21976, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kuroda A, Rauch TA, Todorov I, Ku HT, Al-Abdullah IH, Kandeel F, Mullen Y, Pfeifer GP, Ferreri K. Insulin gene expression is regulated by DNA methylation. PloS one 4: e6953, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kurokawa R, Rosenfeld MG, Glass CK. Transcriptional regulation through noncoding RNAs and epigenetic modifications. RNA Biol 6: 233–236, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee DY, Teyssier C, Strahl BD, Stallcup MR. Role of protein methylation in regulation of transcription. Endocr Rev 26: 147–170, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Li SL, Reddy MA, Cai Q, Meng L, Yuan H, Lanting L, Natarajan R. Enhanced proatherogenic responses in macrophages and vascular smooth muscle cells derived from diabetic db/db mice. Diabetes 55: 2611–2619, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Li Y, Reddy MA, Miao F, Shanmugam N, Yee JK, Hawkins D, Ren B, Natarajan R. Role of the histone H3 lysine 4 methyltransferase, SET7/9, in the regulation of NF-kappaB-dependent inflammatory genes. Relevance to diabetes and inflammation. J Biol Chem 283: 26771–26781, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Liang F, Kume S, Koya D. SIRT1 and insulin resistance. Nat Rev 5: 367–373, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ling C, Del Guerra S, Lupi R, Ronn T, Granhall C, Luthman H, Masiello P, Marchetti P, Groop L, Del Prato S. Epigenetic regulation of PPARGC1A in human type 2 diabetic islets and effect on insulin secretion. Diabetologia 51: 615–622, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ling C, Groop L. Epigenetics: a molecular link between environmental factors and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 58: 2718–2725, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lister R, Pelizzola M, Dowen RH, Hawkins RD, Hon G, Tonti-Filippini J, Nery JR, Lee L, Ye Z, Ngo QM, Edsall L, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Stewart R, Ruotti V, Millar AH, Thomson JA, Ren B, Ecker JR. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature 462: 315–322, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Litherland SA. Immunopathogenic interaction of environmental triggers and genetic susceptibility in diabetes: is epigenetics the missing link? Diabetes 57: 3184–3186, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Liu L, Li Y, Tollefsbol TO. Gene-environment interactions and epigenetic basis of human diseases. Curr Issues Mol Biol 10: 25–36, 2008 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Luger K, Mader AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature 389: 251–260, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Marfella CG, Henninger N, LeBlanc SE, Krishnan N, Garlick DS, Holzman LB, Imbalzano AN. A mutation in the mouse Chd2 chromatin remodeling enzyme results in a complex renal phenotype. Kidney Blood Press Res 31: 421–432, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Martens JA, Winston F. Recent advances in understanding chromatin remodeling by Swi/Snf complexes. Curr Opin Genet Dev 13: 136–142, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Martin C, Zhang Y. The diverse functions of histone lysine methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6: 838–849, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Meerwaldt R, Links T, Zeebregts C, Tio R, Hillebrands JL, Smit A. The clinical relevance of assessing advanced glycation endproducts accumulation in diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol 7: 29, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Metzger E, Wissmann M, Yin N, Muller JM, Schneider R, Peters AH, Gunther T, Buettner R, Schule R. LSD1 demethylates repressive histone marks to promote androgen-receptor-dependent transcription. Nature 437: 436–439, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Miao F, Gonzalo IG, Lanting L, Natarajan R. In vivo chromatin remodeling events leading to inflammatory gene transcription under diabetic conditions. J Biol Chem 279: 18091–18097, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Miao F, Smith DD, Zhang L, Min A, Feng W, Natarajan R. Lymphocytes from patients with type 1 diabetes display a distinct profile of chromatin histone H3 lysine 9 dimethylation: an epigenetic study in diabetes. Diabetes 57: 3189–3198, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Miao F, Wu X, Zhang L, Riggs AD, Natarajan R. Histone methylation patterns are cell-type specific in human monocytes and lymphocytes and well maintained at core genes. J Immunol 180: 2264–2269, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Miao F, Wu X, Zhang L, Yuan YC, Riggs AD, Natarajan R. Genome-wide analysis of histone lysine methylation variations caused by diabetic conditions in human monocytes. J Biol Chem 282: 13854–13863, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mooradian AD. Dyslipidemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 5: 150–159, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Morgan HD, Sutherland HG, Martin DI, Whitelaw E. Epigenetic inheritance at the agouti locus in the mouse. Nat Genet 23: 314–318, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Muhonen P, Holthofer H. Epigenetic and microRNA-mediated regulation in diabetes. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 1088–1096, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mutskov V, Raaka BM, Felsenfeld G, Gershengorn MC. The human insulin gene displays transcriptionally active epigenetic marks in islet-derived mesenchymal precursor cells in the absence of insulin expression. Stem Cells 25: 3223–3233, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nathan DM, Cleary PA, Backlund JY, Genuth SM, Lachin JM, Orchard TJ, Raskin P, Zinman B. Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 353: 2643–2653, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Nathan DM, Lachin J, Cleary P, Orchard T, Brillon DJ, Backlund JY, O'Leary DH, Genuth S. Intensive diabetes therapy and carotid intima-media thickness in type 1 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 348: 2294–2303, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ng RK, Gurdon JB. Epigenetic inheritance of cell differentiation status. Cell Cycle 7: 1173–1177, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Nielsen AL, Sanchez C, Ichinose H, Cervino M, Lerouge T, Chambon P, Losson R. Selective interaction between the chromatin-remodeling factor BRG1 and the heterochromatin-associated protein HP1alpha. EMBO J 21: 5797–5806, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Noh H, Oh EY, Seo JY, Yu MR, Kim YO, Ha H, Lee HB. Histone deacetylase-2 is a key regulator of diabetes- and transforming growth factor-β1-induced renal injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F729–F739, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Park JH, Stoffers DA, Nicholls RD, Simmons RA. Development of type 2 diabetes following intrauterine growth retardation in rats is associated with progressive epigenetic silencing of Pdx1. J Clin Invest 118: 2316–2324, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, Neal B, Billot L, Woodward M, Marre M, Cooper M, Glasziou P, Grobbee D, Hamet P, Harrap S, Heller S, Liu L, Mancia G, Mogensen CE, Pan C, Poulter N, Rodgers A, Williams B, Bompoint S, de Galan BE, Joshi R, Travert F. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 358: 2560–2572, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Pop-Busui R, Low PA, Waberski BH, Martin CL, Albers JW, Feldman EL, Sommer C, Cleary PA, Lachin JM, Herman WH. Effects of prior intensive insulin therapy on cardiac autonomic nervous system function in type 1 diabetes mellitus: the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications study (DCCT/EDIC). Circulation 119: 2886–2893, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Poy MN, Eliasson L, Krutzfeldt J, Kuwajima S, Ma X, Macdonald PE, Pfeffer S, Tuschl T, Rajewsky N, Rorsman P, Stoffel M. A pancreatic islet-specific microRNA regulates insulin secretion. Nature 432: 226–230, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Poy MN, Spranger M, Stoffel M. microRNAs and the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Diabetes Obes Metab 9, Suppl 2: 67–73, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Pugliese G, Pricci F, Pugliese F, Mene P, Lenti L, Andreani D, Galli G, Casini A, Bianchi S, Rotella CM. Mechanisms of glucose-enhanced extracellular matrix accumulation in rat glomerular mesangial cells. Diabetes 43: 478–490, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Qian Y, Feldman E, Pennathur S, Kretzler M, Brosius FC., 3rd From fibrosis to sclerosis: mechanisms of glomerulosclerosis in diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes 57: 1439–1445, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Qiu J. Epigenetics: unfinished symphony. Nature 441: 143–145, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Reddy MA, Sahar S, Villeneuve LM, Lanting L, Natarajan R. Role of Src tyrosine kinase in the atherogenic effects of the 12/15-lipoxygenase pathway in vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 29: 387–393, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Roth SY, Denu JM, Allis CD. Histone acetyltransferases. Annu Rev Biochem 70: 81–120, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]