Abstract

Cisplatin cytotoxicity is dependent on cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (Cdk2) activity in vivo and in vitro. A Cdk2 mutant (Cdk2-F80G) was designed in which the ATP-binding pocket was altered. When expressed in mouse kidney cells, this protein was kinase inactive, did not inhibit endogenous Cdk2, but protected from cisplatin. The mutant was localized in the cytoplasm, but when coexpressed with cyclin A, it was activated, localized to the nucleus, and no longer protected from cisplatin cytotoxicity. Cells exposed to cisplatin in the presence of the activated mutant had an apoptotic phenotype, and endonuclease G was released from mitochondria similar to that mediated by endogenous Cdk2. But unlike apoptosis mediated by wild-type Cdk2, cisplatin exposure of cells expressing the activated mutant did not cause cytochrome c release or significant caspase-3 activation. We conclude that cisplatin likely activates both caspase-dependent and -independent cell death, and Cdk2 is required for both pathways. The mutant-inactive Cdk2 protected from both death pathways, but after activation by excess cyclin A, caspase-independent cell death predominated.

Keywords: cyclin A, caspase-3, cell death

cisplatin [cis-diamminedichloroplatinum (II)] is a common anti-cancer agent used to treat solid tumors, such as head and neck, testicular, breast, and ovarian cancers (8), but it displays dose-limiting toxicity to several organs. It causes tubular kidney damage by apoptosis and necrosis leading to acute kidney injury (10, 16, 28). Previous studies from our laboratory showed that cell cycle inhibitory drugs protect both cultured kidney cells in vitro and mouse kidneys in vivo from cisplatin toxicity (30, 31), and this protection was later shown to be dependent on cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (Cdk2) inhibition (31). The mechanism of the dependency of cisplatin cytotoxicity on Cdk2 is still not understood.

Cdk2, a Ser/Thr protein kinase, is active during the G1/S transition of the eukaryotic cell cycle and throughout S phase. Apart from its role in proliferation, several studies suggest that Cdk2 plays an important role in cell death. Data showed increased Cdk2 activity in cells undergoing apoptosis (13, 29), and cell death was accelerated in cells with induced Cdk2 activity (9, 21). Adachi et al. (1) found that inhibiting Cdk2 activity prevented cell death of cardiomyocytes induced by hypoxia. Similarly, it was shown that Cdk2 regulated apoptosis during ischemic heart injury in vivo and in cultured cardiac myocytes (23). Other studies suggested a role for Cdk2 during DNA damage-induced apoptosis (7). These results indicate that Cdk2 has a role in cell death besides proliferation; however, it is still unclear how Cdk2, which regulates cell cycle progression, contributes to apoptosis.

Cisplatin toxicity was initially suggested to be due to nuclear events; however, recent studies showed that both nuclear and cytoplasmic causes played a role in cisplatin-induced cell death (24, 26, 44). Many pathways leading to apoptosis are activated by cisplatin (18, 24, 26, 34, 35). After initiation, most pathways lead to disruption of the outer membrane of mitochondria and to release of mitochondrial proteins, such as cytochrome c (25). In the cytosol, cytochrome c induces conformational change in apoptosis protease-activating factor 1 leading to activation of caspase-9 and downstream executioner proteases, caspase-3 and -7, causing caspase-dependent apoptosis. Other proteins such as apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) (38) and endonuclease G (Endo G) (22) can also be released from mitochondria and could mediate caspase-independent apoptosis. It is still unclear which cell death pathways initiate cascades resulting in cisplatin cytotoxicity and which amplify these cascades.

In the present study, we examined the role of Cdk2 in cisplatin-induced cell death in mouse kidney proximal tubule (TKPTS) cells using a mutant Cdk2 (Cdk2-F80G) that protected from cytotoxicity. When expressed in TKPTS cells, the Cdk2-F80G protein was kinase inactive, with cytoplasmic localization, and protected from cisplatin cytotoxicity. When coexpressed with excess cyclin A, it was kinase active, localized to the nucleus, and no longer protected from cisplatin. Cisplatin-induced cell death is caused by both caspase-dependent and -independent events. However, in the presence of Cdk2-F80G/cyclin A, cell death by cisplatin was only by the caspase-independent pathway. We conclude that cisplatin activates both caspase-dependent and -independent cell death. Both pathways require Cdk2 and both are inhibited by Cdk2-F80G. Activation of Cdk2-F80G continues to inhibit the caspase-dependent pathway, but cell death is still caused by a caspase-independent pathway.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell culture and treatments.

Experiments were done on mouse kidney proximal tubule cells (TKPTS) (6) grown at 37°C with 5% CO2 in DMEM + Ham's F-12 medium supplemented with 50 μU/ml insulin and 7% FBS. After being split, cells were maintained for 30 h before adenovirus addition. Cisplatin was added to cultures, where indicated, to a final concentration of 25 μM when cells were ∼75% confluent, and the cells were grown for an additional 24 h. Cdk2-F80G, Cdk2-GFP, and cyclin A adenoviruses were added where indicated to a final multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100. For colocalization of Cdk2-F80G and Cdk2-GFP, the high intensity of the mCherry fluorescence necessitated lowering the MOI to 10 so that the protein expression levels, as well as transduction efficiency, were significantly lowered. The change of expression levels from those transductions using 100 MOI did not influence protein localizations.

Adenoviruses.

Cyclin A adenovirus was a gift from Dr. G. Denis (Boston Medical School, Boston, MA). Human wild-type Cdk2 cDNA plasmid was obtained from Dr. S. van den Heuvel (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA) (40). Cdk2-F80G was created by site-directed mutagenesis using the Stratagene Quickchange kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) to change the codon for Phenylalanine 80 (TTT) to a Glycine codon (GGG). The primers (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) used were 5′-CTC TAC CTG GTT GGG GAA TTT CTG CAC C-3′, 5′-GGT GCA GAA ATT CCC CAA CCA GGT AGA G-3′. The Cdk2-F80G adenovirus was constructed by insertion of a BamHI fragment that contained Cdk2 cDNA into the BglII site of the pAdTrack-CMV plasmid. Adenovirus was constructed in our lab according to protocols from Dr. B. Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins, Baltimore, MD) (14). The Cdk2-F80G adenovirus used in these studies was constructed as a mCherry (37) fusion protein to assist in localization. No functional differences were noted to be caused by the presence of the mCherry epitope (data not presented). Cdk2-F80G-mCherry fusion expression adenovirus was constructed by inserting BamHI-HindIII cut cDNA encoding mCherry into the HindIII/BamHI window of pAd-Track-CMV-Cdk2-F80G plasmid. The pAd-Track-CMV-Cdk2-F80G-mCherry plasmid was linearized by digestion with PmeI and subsequently cotransformed into Escherichia coli BJ5183 cells (Stratagene) with pAdEasy-1 adenoviral backbone plasmid. The recombinant plasmid was digested with PacI and transfected into Ad-293 cells. Amplification of recombinant adenoviruses was done in HEK-293 cells, purified by CsCl gradients, and stored at −20°C.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis.

Cells were prepared as previously described (45) and the samples were analyzed using FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson). Both floating and attached cells were combined for analyses. The cells were grouped into sub-G1/G0, G1/G0, S, and G2/M phases using a cell cycle analysis program (WinMDI 2.8). For each culture condition, >1 × 105 cells were analyzed and the experiment was repeated three times. Cells in sub-G1/G0 were considered apoptotic (5).

Kinase assay for measuring Cdk2 activity.

TKPTS cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and collected in cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40) with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. After lysis on ice for 30 min, samples were centrifuged for 20 min at 10,000 g. Protein extracts (200 μg) were immunoprecipitated by agarose-immobilized Cdk2 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or by dsred (anti-mCherry) antibody (CLONTECH, Mountain View, CA) overnight at 4°C with constant rocking, and then washed four times with lysis buffer and once with kinase reaction buffer (20 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol). Washed agarose beads were resuspended in 20-μl kinase reaction buffer containing 1 μg of histone H1 (Upstate Biotechnology, Billerica, MA) as a substrate, 20 μM ATP, and 10 μCi of [γ-32P] ATP (Amersham Biosciences, Pittsburgh, PA) and incubated for 30 min at 30°C. The reaction was stopped by addition of Laemmli buffer (20), samples were boiled for 5 min, and then loaded on 12% SDS-PAGE. Separated proteins were visualized by autoradiography.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting.

Protein extracts used for cyclin A immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting were obtained from TKPTS cells lysed in 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.6, 100 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM EDTA for 20 min and then sonicated for 2 min. Samples for Cdk2 immunoprecipiation were obtained from TKPTS cells by lysing cells as previously described. Protein extracts (200 μg) were immunoprecipitated with agarose-immobilized antibodies against Cdk2 and cyclin A (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), dsred (anti-mCherry; CLONTECH). Precipitated agarose beads were washed three times with lysis buffer and loaded on 12% SDS-PAGE. Western blot was done as described previously (30, 46). Briefly, TKPTS cells were lysed in cold lysis buffer. Protein concentrations were determined using a Bio-Rad protein assay (Hercules, CA). Equal amounts of proteins were loaded on 12% SDS-PAGE. Electrophoresed samples were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane and blocked with 5% milk in Tris-buffered saline Tween 20, and the membrane was incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibody with constant shaking. After being washed, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody was applied. Bound proteins to the secondary antibody were visualized using ECL (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). The primary antibodies used were Cdk2 (M2) polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and caspase-3 polyclonal antibody (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA).

Light microscopy and immunofluorescence confocal microscopy.

TKPTS cells were photographed using an inverted microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE200, Melville, NY) with Hoffman optics before harvesting (30). For confocal studies, immunostaining was done on TKPTS cells grown on coverslips and infected with adenoviruses expressing Cdk2-F80G, Cdk2-GFP, and cyclin A, as indicated. Twenty-four hours later, cells were fixed in 4% neutral buffered formaldehyde for 10 min followed by incubation with blocking serum for 10 min. Cells were then incubated with primary antibody for Golgi apparatus (GM-130, BD Transduction Laboratories, San Diego, CA), cytochrome c (BD Transduction Laboratories), or Endo G (ABCAM, Cambridge, MA). Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse, anti-mouse IgG-Alexa 594 (1:100; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), or anti-rabbit IgG-Alexa 594 (1:200; Invitrogen) secondary antibodies were used for detection of immunofluorescent staining, respectively. DAPI (Vector, Burlingame, CA) staining was performed at the final step for 10 min to visualize nuclei. Fluorescent images were taken using a confocal fluorescence microscope (Zeiss LSM510). To obtain three-dimensional (3-D) images, Z-series taken by confocal microscopy were reconstituted by Huygens Professional software (Scientific Volume Imaging, The Netherlands software). The images presented in Figs. 4, 5, 6, 8 and supplemental movies were selected based on the quality of cell morphology, protein expression, and staining intensity (the online version of this article contains supplemental data). However, the protein localizations represented were typical of those found in almost all of similarly treated cells.

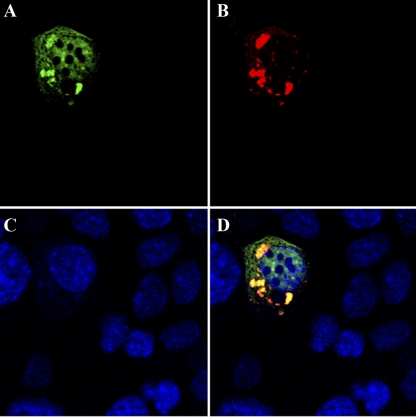

Fig. 4.

Colocalization of Cdk2-F80GmCherry and wild-type Cdk2. TKPTS cells transduced with Cdk2-GFP and Cdk2-F80GmCherry expression adenoviruses. After fixation, cells were stained with DAPI. Fluorescent images were taken by using a confocal microscope (LSM510) with ×63 oil objective. Localization of wild-type Cdk2 (green; A), Cdk2-F80G (red; B), nucleus (blue; C), or merged image (colocalized wild-type and Cdk2-F80G's appear yellow/orange; D).

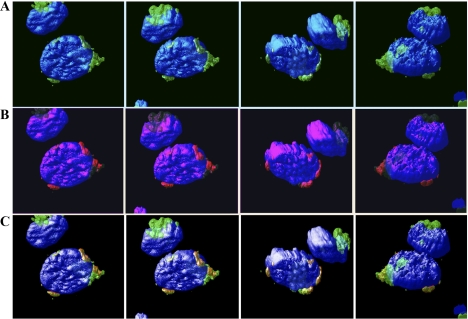

Fig. 5.

Cdk2-F80GmCherry localization with Golgi. TKPTS cells were transduced with Cdk2-F80GmCherry expression adenovirus. After 18–24 h, cells were fixed and stained for Golgi using anti-GM130 antibody and anti-mouse IgG-Alexa 488 secondary antibody. Cells were then stained with DAPI. Cells were scanned with LSM510 confocal fluorescence microscopy with a ×63 oil objective. To obtain the 3-dimensional (3D) images, Z-stack images taken by the confocal (0.5-μm slices) were used in Huygens Professional software (Scientific Volume Imaging). Localization of Golgi (green; A), Cdk2-F80GmCherry (red; B), and nuclei (blue). Colocalizations of Golgi and Cdk2 appear yellow/orange (C).

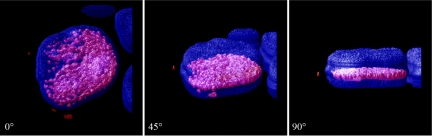

Fig. 6.

Cdk2-F80GmCherry localizes to the nucleus when it is coexpressed with cyclin A. TKPTS cells were transduced with Cdk2-F80GmCherry and cyclin A expression adenoviruses. After 18–24 h, cells were fixed and stained with DAPI. Cells were scanned with LSM510 confocal fluorescence microscopy with a ×63 oil objective. To obtain the 3D images, Z-stack images taken by the confocal (0.5-μm slices) were used in Huygen software (Scientific Volume Imaging). Localization of nuclei (blue) and Cdk2-F80GmCherry (red). The angle of rotation is indicated.

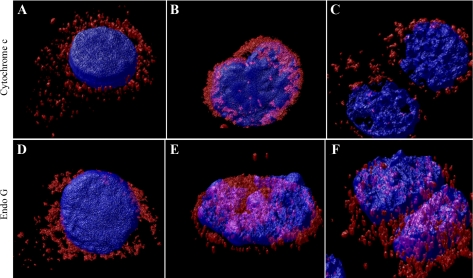

Fig. 8.

Activation of Cdk2-F80G by excess cyclin A allowed caspase-independent cell death to predominate. Cells grown on coverslips were untreated (A, D), exposed to cisplatin (B, E) for 24 h, or treated with both Cdk2-F80G and cyclin A adenoviruses for 24 h and then cisplatin for 24 h (C, F). After 18–24 h, cells were fixed and stained with anti-cytochrome c antibody (BD), or anti-Endo G (ABCAM) and anti-mouse IgG-Alexa 594 (1:100, Invitrogen), or anti-rabbit IgG-Alexa 594 (1:200, Invitrogen) secondary antibodies, respectively. Cells were then stained with DAPI. Cells were scanned with LSM510 confocal fluorescence microscopy with a ×63 oil objective. To obtain the 3D images, Z-stack images taken by the confocal (0.5-μm slices) were used in Huygen software (Scientific Volume Imaging). Images are presented from rotation of 3D rendering of cells. Localization of nuclei (blue), cytochrome c (top, red), and endonuclease G (bottom, red).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical significance between treated and nontreated cultures was done using Student's t-test with two-tailed distribution.

RESULTS

Inactive Cdk2 mutant (Cdk2-F80G) protects TKPTS cells against cisplatin-induced apoptosis.

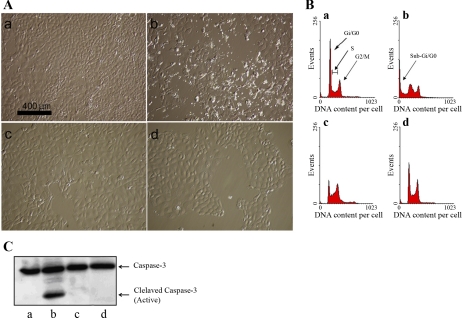

Previous results from our laboratory showed that cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity is dependent on Cdk2 in vivo and in vitro (31). The mechanism by which Cdk2 mediates cell death is not yet known. We constructed several mutants of Cdk2 to investigate their effects on cisplatin cytotoxicity. One mutant, where phenylalanine at position 80 was replaced by glycine (Cdk2-F80G), protected cells from cisplatin-induced cell death (Fig. 1). Cell death in the presence or absence of 25 μM cisplatin was determined by light microscopy (Fig. 1A), FACS analysis of propidium iodide-stained cells (Fig. 1B), and Western blot for caspase-3 activation (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

A: light microscopy of TKPTS cells before harvest. TKPTS cells were untreated (a) or exposed to 25 μM cisplatin for 24 h (b, d). Similar cells were transduced with adenovirus expressing Cdk2-F80GmCherry for 48 h (c, d). For cells exposed to both adenovirus and cisplatin (d), cells were treated with Cdk2-F80GmCherry adenovirus for 24 h and then for 24 h with cisplatin. Cells were photographed with an inverted microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE200) using Hoffman optics before harvesting (scale indicated). B: fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis of propidium iodide (PI)-stained, ethanol-fixed TKPTS cells. Source of cells was the same as A. After treatment, cells were harvested by trypsinization, fixed in ethanol, and then stained with PI and analyzed using FACSCalibur. Apoptosis is shown as percentage of cells in sub-G1/G0 determined using cell cycle analysis program (WinMDI 2.8). C: Cdk2-F80GmCherry inhibits caspase-3 activation induced by cisplatin. Sources of protein extracts as in A. After treatment, cells were lysed with lysis buffer (experimental procedures) and protein samples (100 μg) were separated on 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. After being blocked with 5% milk in Tris-buffered saline Tween 20 (TBST), the membrane was incubated with primary antibody recognizing both cleaved and full-length caspase-3 (cell signaling). Then, the membrane was washed with 1× TBST and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. After being washed, the membrane was developed using enhanced chemiluminescence. Both full-length and cleaved (active) caspases-3 are indicated.

Cdk2-F80G adenovirus infection of TKPTS cells had no effect on cell death (1.3% apoptosis vs. 3% apoptosis with untreated cells) or caspase-3 activation. A slight effect on the cell cycle was noted in which more percentage of cells were in the G2 phase (30% in G2 vs. 18% of control cells in G2). Cisplatin exposure resulted in 20.6% of cells being apoptotic and showed significant caspase-3 cleavage. Transduction of cells with Cdk2-F80G adenovirus protected TKPTS cells from cisplatin toxicity, which lowered apoptosis to background levels (2%), and also prevented caspase-3 activation. Thus, our results show that Cdk2-F80G protects against cisplatin-induced apoptosis.

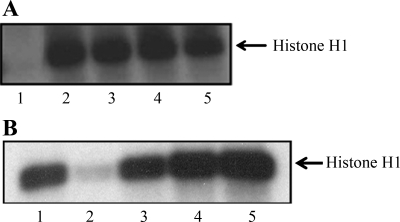

Cdk2-F80G is catalytically inactive, does not inhibit endogenous Cdk2 activity, and its activity is regained with the coexpression of cyclin A.

We previously showed that Cdk2 inhibition by Cdk2 inhibitory drugs by p21 or by DN-Cdk2 protected against cisplatin-induced cell death in vitro as well as in vivo (30). These protective agents inhibited endogenous Cdk2 activity. However, Cdk2 was not inhibited by the Cdk2-F80G mutant (Fig. 2A), although the mutant was kinase inactive (Fig. 2B, lane 2). Cdk2-F80G activity was regained with the coexpression of increasing amounts of cyclin A adenovirus (Fig. 2B, lanes 3–5).

Fig. 2.

A: Cdk2-F80GmCherry mutant does not inhibit endogenous Cdk2 actvity. Cells were either untreated (lanes 1, 2) or transduced with Cdk2-F80GmCherry expression adenovirus (lanes 3–5). Protein extracts were immunoprecipitated with agarose-conjugated Cdk2 antibody (ABCAM; lanes 2–5). As a negative control, we used nonspecific IgG for IP (lane 1). Increasing amounts of Cdk2-F80GmCherry were added to immunoprecipitated (IP'ed) Cdk2 (lanes 4 and 5). Kinase activity was determined using histone H1 as a substrate. B: Cdk2-F80GmCherry mutant is catalytically inactive and regains activity when coexpressed with cyclin A. The activity of the mutant was determined by histone H1 kinase assay. Cells were either untreated (lane 1) or transduced with Cdk2-F80GmCherry expression adenovirus (lanes 2–5). Some cells were also transduced with increasing amounts of cyclin A expression adenovirus (lanes 3–5). Protein extracts were immunoprecipitated with agarose-conjugated Cdk2 antibody (ABCAM; lane 1) or agarose-conjugated mCherry antibody (CLONTECH; lanes 2–5) followed by kinase assay with histone H1. For kinase assay, IP'ed pellets were incubated in 40 μl of kinase buffer containing 1 μg histone H1, 20 μM ATP, and 5 μCi of [γ-32P] ATP at 30°C for 30 min. The reaction was stopped by additon of Laemmli buffer. Proteins were resolved using 12% SDS-PAGE. The gel was dried and exposed to X-ray film.

Protection of TKPTS cells by Cdk2-F80G is lost when it is coexpressed with cyclin A.

Apoptosis of cultured TKPTS cells was determined by light microscopy using Nomarski optics (Fig. 3A), and nuclear fragmentation of DNA was confirmed by DAPI staining (Fig. 3B). Morphology was detected 24 h after cisplatin addition. TKPTS cells were transduced with Cdk2-F80G (Fig. 3A, b, d, f, h and B, b, c, e, f) and cyclin A (Fig. 3A, c, d, g, h and B, c, f). Cells were either untreated Fig. 3A, a-d and B, a–c, or exposed to 25 μM cisplatin (Fig. 3A, e–h and B, d–f). Cells exposed to cisplatin showed apoptotic characteristics of cell death (Fig. 3A, e and B, d) and the same features could be observed in cells transduced with cyclin A and then exposed to cisplatin (Fig. 3A, g). Cells transduced with Cdk2-F80G adenovirus and then exposed to cisplatin were protected from cell death (Fig. 3A, f and B, e). When cyclin A was coexpressed with Cdk2-F80G, cells were no longer protected against cisplatin-induced cell death (Fig. 3A, h and B, f). In the absence of cisplatin, cells cotransduced with both viruses showed only background apoptosis (Fig. 3A, d and B, c).

Fig. 3.

A: light microscopy of cultured mouse proximal tubule kidney cells (TKPTS). Cells were untreated (a-d) or exposed to 25 μM cisplatin for 24 h (e–h). Cells were also transduced with adenovirus expressing Cdk2-F80GmCherry (b, d, f, h) and cyclin A (c, d, g, h) 24 h before cisplatin exposure. B: fluorescence microscopy of TKPTS cells after DAPI staining. Cells were untreated (a–c) or exposed to 25 μM cisplatin for 24 h (d–f). Cells were also transduced with adenovirus expressing Cdk2-F80GmCherry (b, c, e, f) and cyclin A (c, f) 24 h before cisplatin exposure. All cells were grown on coverslips, fixed with neutral-buffered formaldehyde, and stained with DAPI. Apoptosis was studied with a fluorescence microscope with DAPI filter and ×40 oil objective.

Cdk2-F80G is mainly cytosolic and colocalizes with endogenous Cdk2 in the cytoplasm.

To localize Cdk2-F80G and wild-type Cdk2, TKPTS cells were cotransduced with adenoviruses encoding Cdk2-GFP and Cdk2-F80G. The Cdk2 mutant was created as a fusion protein with a mCherry protein. No differences were observed comparing any results using Cdk2-F80G or Cdk2-F80GmCherry (data not shown). Twenty-four hours after transduction, cells were fixed and the nuclei were stained with DAPI. Cells were scanned using confocal fluorescence microscopy (Zeiss LSM510) with a ×63 oil objective. Wild-type Cdk2 is found in both nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments (Fig. 4A). We found that Cdk2-F80G is mainly cytosolic (Fig. 4B; also see supplemental data movie 1) and colocalizes with endogenous Cdk2 (Fig. 4D). To determine the specific subcellular cytoplasmic localization of Cdk2-F80G, we performed immunostaining with specific organelle marker proteins. The colocalization of Cdk2-F80G with the Golgi apparatus was confirmed with immunostaining with GM-130 as a Golgi marker (Fig. 5; also see supplemental data movie 2). To obtain 3-D images, we used confocal Z-sections (0.5 μm) reconstituted with Huygen software (Scientific Volume Imaging). These findings suggested that substrates of Cdk2 involved in the initiation of cisplatin cytotoxicity localize to the cytosol, specifically to endoplasmic reticulum/Golgi compartments.

Cdk2-F80G localizes to the nucleus when it is coexpressed with cyclin A.

Cdk2-F80G is catalytically inactive but it regains its activity when coexpressed with cyclin A (Fig. 2B). Without cyclin A, it is mainly cytosolic, unlike wild-type Cdk2 which is both nuclear and cytosolic (Figs. 4 and 5). We studied Cdk2-F80G localization when cyclin A is abundant and Cdk2-F80G is active. We transduced TKPTS cells with adenoviruses expressing Cdk2-F80G and cyclin A. After 24 h, cells were fixed and nuclei were stained with DAPI. Cells were scanned with confocal fluorescence microscopy (Zeiss LSM510) using a ×63 oil objective. Z-stack images (0.5-μm slices) were reconstituted in Huygens Professional software (Scientific Volume Imaging) to obtain 3-D images. The observations showed that Cdk2-F80G is primarily translocated to the nucleus when it is coexpressed with cyclin A (Fig. 6; also see supplemental data movie 3), a similar pattern to that of endogenous Cdk2.

Cdk2 is required for both caspase-dependent and -independent cisplatin-induced cell death.

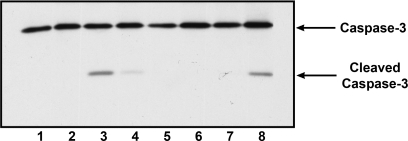

Cells exposed to cisplatin in the presence of activated mutant Cdk2 (Cdk2-F80G/cyclin A) had an apoptotic phenotype characterized by shrinkage and blebbing (Fig. 3A, h) and nuclear staining showed nuclear fragmentation and chromatin condensation (Fig. 3B, f). However, caspase-3 activation was not significant (Fig. 7, lane 7). To elucidate the possible mechanism how the activated mutant Cdk2 participates in apoptosis, we studied the release of mitochondrial proteins that are important in caspase-dependent apoptosis (cytochrome c), and proteins that could play a role in caspase-independent apoptosis (Endo G; Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

Cisplatin-induced apoptosis in the presence of activated Cdk2-F80G mutant is independent of caspase-3 activation. Cells were untreated (lane 1) and transduced with Cdk2-F80G adenovirus (lanes 2, 4, 6, 7) and cyclin A adenovirus (lanes 5–8) for 48 h. Cells were exposed to 25 μM cisplatin for 24 h without adenoviruses (lane 3) or treated with adenovirus for 24 h and then with cisplatin for 24 h (lanes 4, 7, 8). After treatment, cells were lysed and 100 μg protein were separated on 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane. After being blocked with 5% milk in TBST, the membrane was incubated with primary antibody recognizing both cleaved and full-length caspases-3 (cell signaling).

TKPTS cells grown on coverslips were transduced with both Cdk2-F80G and cyclin A adenoviruses (Fig. 8, C and F). Twenty-four hours after virus transduction, cells were either left untreated (Fig. 8, A and D) or exposed to 25 μM cisplatin (Fig. 8, B, C, E, F). Forty-eight hours after transduction, cells were fixed and cytochrome c and Endo G were detected by immunostaining. Finally, nuclei were stained with DAPI. Cells were scanned under confocal fluorescence microscope (Zeiss LSM510) using a ×63 oil objective. The 3-D images were obtained using Huygen software as described previously. Untreated cells show punctate staining of cytochrome c and Endo G corresponding to mitochondrial localization (Fig. 8, A and D; also see supplemental data movies 4 and 5). Cells transduced with Cdk2-F80G, cyclin A, or both adenoviruses showed similar localization (data not shown). In contrast, cells exposed to cisplatin had diffuse staining of cytochrome c indicating its release from mitochondria (Fig. 8B; see supplemental data movie 6); Endo G was also released from mitochondria and localized to both nucleus and cytoplasm (Fig. 8E; also see supplemental data movie 7). Cisplatin exposure of cells expressing activated mutant Cdk2 did not cause cytochrome c release from mitochondria (Fig. 8C; see also supplemental data movie 8), but Endo G was localized in the cytoplasm and the nucleus (Fig. 8F; see also supplemental data movie 9).

DISCUSSION

We previously published that cisplatin cytotoxicity is dependent on Cdk2 (32). We also showed that cisplatin can induce nuclear-independent apoptosis in TKPTS cells and that cytoplasmic Cdk2 plays an important role in apoptosis signaling (44). This predicts either a unique Cdk2-dependent pathway of cell death or that Cdk2 activity is integral for one or more of the known death pathways. Expression of DN-Cdk2 by adenoviral transduction eliminated endogenous Cdk2 kinase activity and protected from cisplatin cytotoxicity (46). This reagent confirmed the dependence of cisplatin-induced cell death on Cdk2 but was not useful to probe the pathway involved. Cdk2 belongs to a family of Ser/Thr kinases that are critically important in the progression of eukaryotic cell cycle. To study the dependence of cell death on Cdk2, we created several mutants, one of which, Cdk2-F80G, had an effect on cell death without inhibiting endogenous Cdk2 activity.

When expressed by adenoviral transduction in mouse kidney proximal tubule (TKPTS) cells, Cdk2-F80G protein was inactive unless excess cyclin A was expressed in the cells (Fig. 2B). Inactive Cdk2-F80G conferred protection against cisplatin-induced apoptosis similar to that obtained when inhibiting Cdk2 by drugs, p21 adenovirus, and DN-Cdk2. Cdk2-inhibitory drugs, p21, and DN-Cdk2 all inhibit endogenous Cdk2 activity but Cdk2-F80G did not inhibit endogenous wild-type Cdk2 activity (Fig. 2A), showing that the mechanism of protection was more likely to be from either competition with endogenous Cdk2 for a substrate critical for cell death, or displacement of Cdk2 from access to a critical substrate.

Since we showed that cisplatin-induced cell death could have cytoplasmic origins, we studied the subcellular localization of Cdk2-F80G. Confocal imaging showed cytoplasmic localization of Cdk2-F80G, primarily in the Golgi and endoplasmic reticulum (Figs. 4 and 5). It also showed that Cdk2-F80G colocalized with endogenous Cdk2 in these compartments and did not displace Cdk2 from these locations (Fig. 4). Endogenous Cdk2 appeared to be both nuclear and cytoplasmic as previously reported (3, 4, 11, 15, 17, 19, 27, 33, 42). Immunoprecipitation experiments showed that Cdk2-F80G had a low affinity for cyclins (data not shown) and was activated by coexpression with excess cyclin A (Fig. 2B). When Cdk2-F80G was activated by cyclin A, it no longer protected against cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity and it was primarily relocated to the nucleus (Fig. 6), similar to endogenous Cdk2. Neither cyclin A nor Cdk2 has a consensus nuclear localization signal and the signal to import this heterodimer into the nucleus has not yet been identified. However, Maridor et al. (27) observed that the nuclear localization of cyclin A correlated with its ability to bind Cdk and Jackman et al. (17) found that Cdk2/cyclin A shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm, but that its nuclear import was not determined by its binding to another protein containing a nuclear localization signal.

Cell death induced by cisplatin in the presence of the active mutant showed an apoptotic phenotype (Fig. 3). However, caspase-3 activation was not significant (Fig. 7). We concluded that cells exposed to cisplatin in the presence of activated Cdk2-F80G proceeded by a caspase-independent mode of cell death.

Most apoptotic cell death originates from permeabilization of the mitochondrial outer membrane causing the release of apoptogenic proteins such as cytochrome c, leading to caspase-dependent cell death. However, without release of cytochrome c, release of other mitochondrial proteins, such as Endo G or AIF, is thought to result in a caspase-independent cell death (39). Cells exposed to cisplatin showed a diffuse staining for cytochrome c, indicating that it is released into the cytosol, and Western blotting showed that caspase-3 was significantly activated. In contrast, cytochrome c was not released into the cytosol of cisplatin-exposed cells expressing active Cdk2-F80G, and caspase-3 activation was not significant in these cells. However, Endo G was released from mitochondria and translocated to the nucleus, similar to its localization in cisplatin-exposed cells expressing only endogenous Cdk2. A similar observation was previously reported during galectin-1-induced cell death (12). The exact mechanisms controlling the release of mitochondrial proteins are not completely understood. It was proposed that these mechanisms are protein specific and mediated by different changes in the mitochondria (2, 36, 41, 43, 47). Our studies suggest that cisplatin does not cause the same mitochondrial changes in cells expressing active Cdk2-F80G as in cells expressing only endogenous Cdk2.

Our data suggest that Cdk2 activity is required for both caspase-dependent and -independent cell death induced by cisplatin. Activation of Cdk2-F80G by excess cyclin A allowed caspase-independent apoptosis to predominate. We propose that the mutant Cdk2 competed with endogenous Cdk2 for a specific substrate that is localized in the cytoplasm and is important in cisplatin-induced cell death.

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by research grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01-DK-54471) and a VA Merit Review and with resources and the use of facilities at the John L. McClellan Memorial Veterans' Hospital (Little Rock, AR).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are thankful for Dr. G. Denis (Boston Medical School) for providing the adenovirus encoding cyclin A. We also appreciate the gift of human wild-type Cdk2 cDNA plasmid obtained from Dr. S. van den Heuvel (Massachusetts General Hospital). We deeply thank J. A. Kamykowski and Dr. B. Storrie (University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, AR) for help in the 3-D images.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi S, Ito H, Tamamori-Adachi M, Ono Y, Nozato T, Abe S, Ikeda M, Marumo F, Hiroe M. Cyclin A/cdk2 activation is involved in hypoxia-induced apoptosis in cardiomyocytes. Circ Res 88: 408–414, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnoult D, Gaume B, Karbowski M, Sharpe JC, Cecconi F, Youle RJ. Mitochondrial release of AIF and EndoG requires caspase activation downstream of Bax/Bak-mediated permeabilization. EMBO J 22: 4385–4399, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castro A, Jaumot M, Verges M, Agell N, Bachs O. Microsomal localization of cyclin A and Cdk2 in proliferating rat liver cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 201: 1072–1078, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coqueret O. New roles for p21 and p27 cell-cycle inhibitors: a function for each cell compartment? Trends Cell Biol 13: 65–70, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Deiry WS, Tokino T, Velculescu VE, Levy DB, Parsons R, Trent JM, Lin D, Mercer WE, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell 75: 817–825, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ernest S, Bello-Reuss E. Expression and function of P-glycoprotein in a mouse kidney cell line. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 269: C323–C333, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finkielstein CV, Chen LG, Maller JL. A role for G1/S cyclin-dependent protein kinases in the apoptotic response to ionizing radiation. J Biol Chem 277: 38476–38485, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giaccone G. Clinical perspectives on platinum resistance. Drugs 59: 9–17, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gil-Gómez G, Berns A, Brady HJ. A link between cell cycle and cell death: Bax and Bcl-2 modulate Cdk2 activation during thymocyte apoptosis. EMBO J 17: 7209–7218, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gobe GC, Endre ZH. Cell death in toxic nephropathies. Semin Nephrol 23: 460–464, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golsteyn RM. Cdk1 and Cdk2 complexes (cyclin dependent kinases) in apoptosis: a role beyond the cell cycle. Cancer Lett 217: 129–138, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hahn HH, Pang M, He J, Hernandez JD, Yang RY, Li LY, Wang X, Liu FT, Baum LG. Galectin-1 induces nuclear translocation of endonuclease G in caspase- and cytochrome c-independent T cell death. Cell Death Differ 11: 1277–1286, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hakem A, Sasaki T, Kozieradzki I, Penninger JM. The cyclin-dependent kinase Cdk2 regulates thymocyte apoptosis. J Exp Med 189: 957–968, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He TC, Zhou S, da Costa LT, Yu J, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. A simplified system for generating recombinant adenoviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 2509–2514, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiromura K, Pippin JW, Blonski MJ, Roberts JM, Shankland S. The subcellular localization of cyclin dependent kinase 2 determines the fate of mesangial cells: role in apoptosis and proliferation. Oncogene 21: 1750–1758, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang Q, Dunn RT, Jayadev S, DiSorbo O, Pack FD, Farr SB, Stoll RE, Blanchard KT. Assessment of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity by microarray technology. Toxicol Sci 63: 196–207, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackman M, Kubota Y, den Elzen N, Hagting A, Pines J. Cyclin A- and cyclin E-Cdk complexes shuttle between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Mol Biol Cell 13: 1030–1045, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang M, Wei Q, Wang J, Du Q, Yu J, Zhang L, Dong Z. Regulation of PUMA-alpha by p53 in cisplatin-induced renal cell apoptosis. Oncogene 25: 4056–4066, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keenan SM, Bellone C, Baldassare JJ. Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 nucleocytoplasmic translocation is regulated by extracellular regulated kinase. J Biol Chem 276: 22404–22409, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227: 680–685, 1970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levkau B, Koyama H, Raines EW, Clurman BE, Herren B, Orth K, Roberts JM, Ross R. Cleavage of p21Cip1/Waf1 and p27Kip1 mediates apoptosis in endothelial cells through activation of Cdk2: role of a caspase cascade. Mol Cell 1: 553–563, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li LY, Luo X, Wang X. Endonuclease G is an apoptotic DNase when released from mitochondria. Nature 412: 95–99, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liem DA, Zhao P, Angelis E, Chan SS, Zhang J, Wang G, Berthet C, Kaldis P, Ping P, MacLellan WR. Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 signaling regulates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol 45: 610–616, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu H, Baliga R. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-associated caspase 12 mediates cisplatin-induced LLC-PK1 cell apoptosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 1985–1992, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu X, Kim CN, Yang J, Jemmerson R, Wang X. Induction of apoptotic program in cell-free extracts: requirement for dATP and cytochrome c. Cell 86: 147–157, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mandic A, Hansson J, Linder S, Shoshan MC. Cisplatin induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and nucleus-independent apoptotic signaling. J Biol Chem 278: 9100–9106, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maridor G, Gallant P, Golsteyn R, Nigg E. Nuclear localization of vertebrate cyclin A correlates with its ability to form complexes with CDK catalytic subunits. J Cell Sci 106: 535–544, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Megyesi J, Safirstein RL, Price PM. Induction of p21WAF1/CIP1/SDI1 in kidney tubule cells affects the course of cisplatin-induced acute renal failure. J Clin Invest 101: 777–782, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meikrantz W, Gisselbrecht S, Tam SW, Schlegel R. Activation of cyclin A-dependent protein kinases during apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 3754–3758, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Price PM, Safirstein RL, Megyesi J. Protection of renal cells from cisplatin toxicity by cell cycle inhibitors. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F378–F384, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Price PM, Yu F, Kaldis P, Aleem E, Nowak G, Safirstein RL, Megyesi J. Dependence of cisplatin-induced cell death in vitro and in vivo on cyclin-dependent kinase 2. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2434–2442, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Price PM, Safirstein RL, Megyesi J. The cell cycle and acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 76: 604–613, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pujol MJ, Jaime M, Serratosa J, Jaumot M, Agell N, Bachs O. Differential association of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 with cyclin E-CDK2 during rat liver regeneration. J Hepatol 33: 266–274, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramesh G, Reeves WB. TNF-alpha mediates chemokine and cytokine expression and renal injury in cisplatin nephrotoxicity. J Clin Invest 110: 835–842, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Razzaque MS, Koji T, Kumatori A, Taguchi T. Cisplatin-induced apoptosis in human proximal tubular epithelial cells is associated with the activation of the Fas/Fas ligand system. Histochem Cell Biol 111: 359–365, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ren J, Agata N, Chen D, Li Y, Yu WH, Huang L, Raina D, Chen W, Kharbanda S, Kufe D. Human MUC1 carcinoma-associated protein confers resistance to genotoxic anticancer agents. Cancer Cell 5: 163–175, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shaner NC, Campbell RE, Steinbach PA, Giepmans BN, Palmer AE, Tsien RY. Improved monomeric red, orange and yellow fluorescent proteins derived from Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein. Nat Biotechnol 22: 1567–1572, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Susin SA, Lorenzo HK, Zamzami N, Marzo I, Snow BE, Brothers GM, Mangion J, Jacotot E, Costantini P, Loeffler M, Larochette N, Goodlett DR, Aebersold R, Siderovski DP, Penninger JM, Kroemer G. Molecular characterization of mitochondrial apoptosis-inducing factor. Nature 397: 441–446, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tait SW, Green DR. Caspase-independent cell death: leaving the set without the final cut. Oncogene 27: 6452–6461, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van den Heuvel S, Harlow E. Distinct roles for cyclin-dependent kinases in cell cycle control. Science 262: 2050–2054, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Loo G, Saelens X, van Gurp M, MacFarlane M, Martin SJ, Vandenabeele P. The role of mitochondrial factors in apoptosis: a Russian roulette with more than one bullet. Cell Death Differ 9: 1031–1104, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verges M, Castro A, Jaumot M, Bachs O, Enrich C. Cyclin A is present in the endocytic compartment of rat liver cells and increases during liver regeneration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 230: 49–53, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang X, Yang C, Chai J, Shi Y, Due X. Mechanisms of AIF-mediated apoptotic DNA degradation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 298: 1587–1592, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu F, Megyesi J, Price PM. Cytoplasmic initiation of cisplatin cytotoxicity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F44–F52, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu F, Megyesi J, Safirstein R, Price PM. Involvement of the CDK2-E2F1 pathway in cisplatin cytotoxicity in vitro and in vivo. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F52–F59, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu F, Megyesi J, Safirstein RL, Price PM. Identification of the functional domain of p21(WAF1/CIP1) that protects cells from cisplatin cytotoxicity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F514–F520, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zamzami N, Kroemer G. Apoptosis: mitochondrial membrane permeabilization–the (w)hole story? Curr Biol 13: R71–R73, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.