Abstract

Familial hemiplegic migraine type-1 FHM-1 is caused by missense mutations in the CACNA1A gene that encodes the α1A pore-forming subunit of CaV2.1 Ca2+ channels. We used knock-in (KI) transgenic mice harboring the pathogenic FHM-1 mutation R192Q to study neurotransmission at the calyx of Held synapse and cortical layer 2/3 pyramidal cells (PCs). Using whole cell patch-clamp recordings in brain stem slices, we confirmed that KI CaV2.1 Ca2+ channels activated at more hyperpolarizing potentials. However, calyceal presynaptic calcium currents (IpCa) evoked by presynaptic action potentials (APs) were similar in amplitude, kinetic parameters, and neurotransmitter release. CaV2.1 Ca2+ channels in cortical layer 2/3 PCs from KI mice also showed a negative shift in their activation voltage. PCs had APs with longer durations and smaller amplitudes than the calyx of Held. AP-evoked Ca2+ currents (ICa) from PCs were larger in KI compared with wild-type (WT) mice. In contrast, when ICawas evoked in PCs by calyx of Held AP waveforms, we observed no amplitude differences between WT and KI mice. In the same way, Ca2+ currents evoked at the presynaptic terminals (IpCa)of the calyx of Held by the AP waveforms of the PCs had larger amplitudes in R192Q KI mice that in WT. These results suggest that longer time courses of pyramidal APs were a key factor for the expression of a synaptic gain of function in the KI mice. In addition, our results indicate that consequences of FHM-1 mutations might vary according to the shape of APs in charge of triggering synaptic transmission (neurons in the calyx of Held vs. excitatory/inhibitory neurons in the cortex), adding to the complexity of the pathophysiology of migraine.

INTRODUCTION

Transmitter release at central synapses is triggered by Ca2+ influx through multiple voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) subtypes but increasingly relies on CaV2.1 (P/Q-type) Ca2+ channels with maturation (Iwasaki and Takahashi 1998; Iwasaki et al. 2000). Familial hemiplegic migraine type-1 (FHM-1) is caused by missense mutations in the CACNA1A gene that encodes the α1A subunit of CaV2.1 Ca2+ channels. Typical migraine attacks in FHM patients are associated with transient hemiparesis and are a useful model to study pathogenic mechanisms of the common forms of migraine (Ferrari et al. 2008). Biophysical analysis of FHM-1 Ca2+ channel dysfunction in heterologus systems is controversial because both loss-of-function and gain-of-function phenotypes have been reported (Barrett et al. 2005; Cao and Tsien 2005; Hans et al. 1999; Kraus et al. 1998, 2000; Tottene et al. 2002). However, analysis of single-channel properties of human CaV2.1 channels carrying FHM-1 mutations showed a consistent increase in channel open probability and Ca2+ influx at negative voltages, mainly caused by a negative shift in channel activation (Tottene et al. 2002, 2005). A knock-in (KI) migraine mouse model carrying the human FHM-1 R192Q mutation was generated and exhibits several gain-of-function effects, including a negative shift in CaV2.1 channel activation in cerebellar granule cells, increased synaptic transmission at the neuromuscular junction, and increased susceptibility to cortical spreading depression (CSD) (van den Maagdenberg et al. 2004), a likely mechanism of the migraine aura (Lauritzen 1994). Using microcultures and brain slices from FHM-1 mice, Tottene et al. (2009) have recently shown increased probability of glutamate release at cortical layer 2/3 pyramidal cells. Intriguingly, neurotransmission from inhibitory fast-spiking interneurons appeared unaltered, despite being mediated by P/Q-type channels (i.e., carrying the FHM-1 mutation). This abnormal balance of cortical excitation-inhibition was associated with the increased susceptibility for CSD in the KI mice, but the underlying mechanism changing synaptic strength by the R192Q mutation is not fully understood. We used KI R192Q mice to study neurotransmission at the giant synapse known as the calyx of Held. This is a glutamatergic afferent forming on neurons of the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB) (Forsythe 1994), where both presynaptic calcium currents (IpCa) and excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) can be recorded. Because migraine is associated with cortical circuits (Aurora and Wilkinson 2007), we extended our studies to cortical layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons, comparing Ca2+ currents elicited by different AP waveforms. We observed that KI presynaptic CaV2.1 channels activate at more hyperpolarized membrane potentials than wild-type (WT) channels. However, only a wide action potential can account for an increment in the evoked Ca2+ currents in KI mice compared with WT. Our observations may shed light on differential effects of FHM-1 mutations on different cortical synapses and thereby provide a better basis to understand the contribution of migraine mutations to pathology.

METHODS

Generation of the R192Q KI mouse strain has been described previously (van den Maagdenberg et al. 2004). Both homozygous R192Q KI and WT mice from a similar genetic mixed background of 129 and C57BL6J were used for the experiments. All experiments were carried out according to national guidelines and approved by local Ethical Committees.

Preparation of brain stem and cortical slices

Mice of P11–15 days were killed by decapitation, and the brain was removed rapidly and placed into an ice-cold low-sodium artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF). The brain stem or cortical hemispheres containing motor cortex were mounted in the Peltier chamber of an Integraslice 7550PSDS microslicer (Campden Instruments). Transverse slices containing MNTB were cut sequentially and transferred to an incubation chamber containing low-calcium, normal-sodium ACSF at 37°C for 1 h and returned at room temperature. Slices of either 200 or 300 μm thickness were used for presynaptic Ca2+ current recordings and for EPSC recordings, respectively. Normal ACSF contained (mM) 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 26 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 10 glucose, 0.5 ascorbic acid, 3 myo inositol, 2 sodium pyruvate, 1 MgCl2, and 2 CaCl2. Low sodium ACSF was as above but NaCl was replaced by 250 mM sucrose and MgCl2 and CaCl2 concentrations were 2.9 and 0.1 mM, respectively. The pH was 7.4 when gassed with 95% O2-5% CO2. Similarly, coronal slices including the motor cortex (180–250 μm) were obtained from P7–P8 mice.

Electrophysiology

Slices were transferred to an experimental chamber perfused with normal ACSF at 25°C. Neurons were visualized using Nomarski optics on a BX50WI microscope (Olympus) and a 60×/0.90 NA water immersion objective lens (LUMPlane FI, Olympus). Whole cell voltage-clamp recordings were made with patch pipettes pulled from thin-walled borosilicate glass (GC150F-15, Harvard Apparatus). Electrodes had resistances of 3.2–3.6 MΩ for presynaptic recordings and 3.0–3.4 MΩ for postsynaptic recordings when filled with internal solution. Patch solutions for voltage-clamp recordings contained (mM) 110 CsCl, 40 HEPES, 10 TEA-Cl, 12 Na2phosphocreatine, 0.5 EGTA, 2 MgATP, 0.5 LiGTP, 5 QX-314, and 1 MgCl2; pH was adjusted to 7.3 with CsOH. Lucifer yellow was also included to visually confirm presynaptic recordings location.

Currents were recorded using a Multiclamp 700A amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA), a Digidata 1322A (Axon Instruments), and pClamp 9.0 software (Axon Instruments). Data were sampled at 50 kHz and filtered at 6 kHz (low-pass Bessel). Series resistance was compensated to be in the range 4–8 MΩ. Whole cell membrane capacitances ranged 15–25 pF for calyx of Held terminals and 28–36 pF for layer 2/3 pyramidal cells. Leak currents were subtracted on-line with a P/5 protocol. Ca2+ currents were recorded in the presence of extracellular TTX (1 μM) and TEA-Cl (10 mM). EPSCs were evoked by stimulating the globular bushy cell axons in the trapezoid body at the midline using a bipolar platinum electrode attached to an isolated stimulator (stimuli of 0.1 ms, 4–10 V). Strychnine (1 μM) was added to the external solution to block inhibitory glycinergic synaptic responses.

Action potentials (APs) were measured in whole cell configuration under current-clamp mode. Patch solutions for current-clamp recordings contained (mM) 110 K−gluconate, 30 KCl, 10 HEPES, 10 Na-phosphocreatine, 0.2 EGTA, 2 MgATP, 0.5 LiGTP, and 1 MgCl2. Only cells that had membrane resting potential between −60 and −75 mV were selected for recording. APs were elicited by injecting depolarizing step current pulses of 1–2 nA during 0.25 ms.

Average data are expressed and plotted as mean ± SE. Statistical significance was determined using either Student's t-test or repeated-measures one-way ANOVA plus Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test.

RESULTS

Presynaptic calcium currents (IpCa) and EPSCs from FHM-1 R192Q mice at the calyx of Held

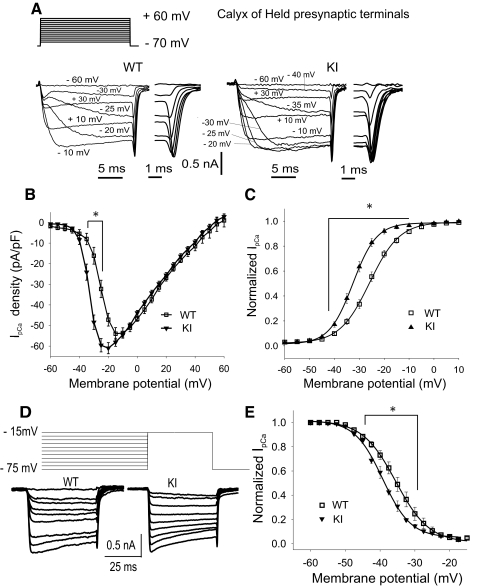

We initially studied the effect of the FHM-1 R192Q mutation on the biophysical properties of presynaptic Ca2+ currents, which at the calyx of Held are almost exclusively mediated by P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. We examined the current-voltage (I-V) relationship of the presynaptic Ca2+ currents (IpCa) at calyx of Held terminals after voltage-step depolarizations. Representative recordings are shown in Fig. 1A. In WT mice (n = 17), IpCa activated around −45 mV, with a peak at −15 mV, and showed an apparent reversal potential of around 55–60 mV. IpCa activates at more hyperpolarizing potentials in R192Q KI calyx (n = 26), peaking at −20 mV, with similar reversal potential. In Fig. 1B, mean IpCa amplitudes were normalized to the membrane capacitance of each presynaptic terminal. Maximum current amplitudes (measured at the potential corresponding to the peak of the I-V relationship) were not significantly different: 1,150 ± 100 (current density 61 ± 3 pA/pF, n = 26) and 1,050 ± 150 pA (current density 54 ± 3 pA/pF, n = 17) for KI and WT, respectively (Student′s t-test, P > 0.05). Activation curves obtained from the peak amplitudes of tail currents showed a −6.5 mV shift toward hyperpolarized potentials in KI compared with WT mice (Fig. 1C). Therefore both IV and activation curves from R192Q KI presynaptic terminals were significantly different compared with WT (1-way ANOVA RM, Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc, P < 0.001). Steady-state inactivation was measured using 2.5 s conditioning step potentials applied to presynaptic terminals, followed by a 50 ms test step to the potential at the peak of the I-V curve. Representative recordings are shown in Fig. 1D. Currents evoked by test voltage steps were normalized, plotted against voltage, and fitted by the Boltzmann's function (Fig. 1E). Half-inactivation voltages V1/2 were significantly more negative for R192Q KI compared with WT (Student's t-test, P = 0.017).

Fig. 1.

Properties of presynaptic Ca2+ currents at the calyx of Held from wild-type (WT) and R192Q knock-in (KI) mice. A: IpCa evoked (bottom) by 20 ms depolarizing voltage steps (top) from −75 mV to potentials ranging −60 to 60 mV (5 mV steps). Right insets: tail currents elicited after repolarization to −75 mV. B: I/V relationship for IpCa from WT (n = 17) and R192Q KI (n = 26). C: IpCa activation curves: normalized amplitudes of tail currents plotted against voltage and fitted by the Boltzmann's function: I(V) = {1/[(1 + exp [(V − V1/2)/k]}. Half-activation voltages (V1/2) were −32.4 ± 0.3 mV for R192Q KI (n = 26) and −25.9 ± 0.2 mV for WT (Student's t-test, P = 6 × 10−6, n = 17) and slope factors (k) 4.75 ± 0.25 and 6.0 ± 0.2 mV (P = 0.035, Student's t-test) for R192Q KI and WT, respectively. D: IpCa evoked by a 50 ms voltage step to the peak of the I-V curve after applying conditioning prepulses for 2.5 s to different voltages from −75 to −15 mV (2.5 mV steps). E: steady-state inactivation of IpCa from R192Q KI and WT terminals. Data are normalized to the maximum peak amplitude, plotted against the conditioning voltage and fitted by the Boltzmann's function. Half-inactivation voltages V1/2 were significantly more negative (−39.2 ± 0.2 mV, n = 12) for R192Q KI compared with WT (−35.5 ± 0.1 mV, n = 6; Student's t-test, P = 0.017). Slopes were −4.0 ± 0.2 and −4.8 ± 0.1 mV (Student's t-test, P = 0.06) for R192Q KI and WT, respectively. *Significant differences between WT and R192Q KI mice (P < 0.001, 1-way ANOVA RM, Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc).

In conclusion, R192Q KI mutation does affect biophysical properties of presynaptic Ca2+ currents: IpCa is opened at more hyperpolarizing membrane potentials.

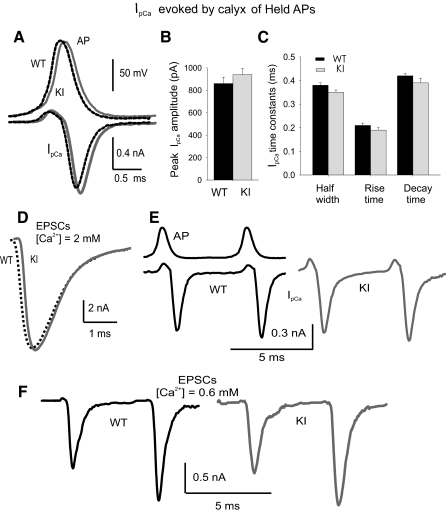

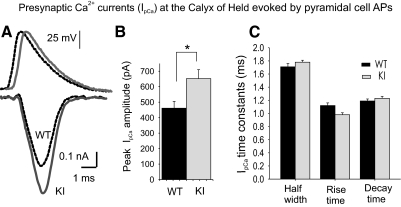

IpCa elicited by AP waveforms from Calyx of Held terminals

Assuming that the kinetics of IpCa can be modeled by Hodgkin/Huxley equations, a shift to more negative activation voltages should generate a larger Ca2+ current during an AP (Borst and Sakmann 1999). IpCa was evoked by real AP waveforms previously recorded from the same preparation (see methods). No differences in AP waveforms were observed between WT and R192Q KI synapses (Fig. 2A, top traces). Because the duration of calyx of Held APs is shorter than 1 ms, it was important to have a good clamp of the membrane potential that assured effective voltage control during APs depolarization and repolarization. Membrane capacity and series resistance were well compensated, and IpCa recordings were accepted for analysis only if the presynaptic terminals were patch clamped under the following conditions: uncompensated series resistance <12 MΩ and leak currents <80 pA. Under these conditions, IpCa had kinetics that were in agreement with those previously described (Fedchyshyn and Wang 2005; Takahashi 2005; Yang and Wang 2006). Mean traces of IpCa evoked by the calyx of Held APs for both R192Q KI (n = 48) and WT mice (n = 30) are shown in Fig. 2A (bottom traces). There were no significant differences in mean IpCa amplitudes between KI and WT calyx of Held presynaptic terminals (Fig. 2B; P = 0.16, Student's t-test). Mean half widths, decay times, and rise times were also similar between WT and R192Q KI mice (Fig. 2C; P > 0.05, Student's t-test). We concluded that the negative shift in activation of presynaptic Ca2+ channels in R192Q KI mice had little impact on Ca2+ currents when APs from calyx of Held were used as waveforms.

Fig. 2.

Action potential (AP)-evoked presynaptic calcium currents (IpCa) and excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) at calyx of Held from WT and R192Q KI mice. A: Top traces: average APs waveforms at the calyx of Held from WT (dotted black, n = 4) and R192Q KI (gray, n = 3) mice. Mean potential amplitude was 110 ± 2 and 112 ± 2 mV, half-width was 0.44 ± 0.02 and 0.44 ± 0.03 ms, rise time (10–90%) was 0.33 ± 0.02 and 0.31 ± 0.04 ms, and decay time was 0.40 ± 0.02 and 0.44 ± 0.04 ms for WT and R192Q KI mice, respectively. Bottom traces: mean IpCa elicited by APs (dotted black and gray traces for WT and R192Q KI, respectively). B: mean IpCa amplitudes evoked by APs at the calyx of Held presynaptic terminals are not significantly different between WT and R192Q KI mice. C: kinetic parameters of presynaptic Ca2+ currents at the calyx of Held synapses generated by their own APs (n = 30 for WT and n = 48 for R192Q KI mice). D: representative EPSCs evoked in medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB) neurons from WT (dotted black) and R192Q KI (gray) mice at a holding potential of −70 mV in 2 mM [Ca2+]o artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF). E: presynaptic Ca2+ current facilitation. Pairs of AP waveforms evoked IpCa, showing activity-dependent facilitation in WT and R192Q KI. Mean pair pulse facilitation was 12 ± 2% in R192Q KI (n = 12) and 10 ± 1% in WT mice (n = 10). F: facilitation of EPSCs. A pair of stimuli was applied with a short interval (10 ms). In low external Ca2+ concentration (0.6 mM) and high external Mg2+ concentration (2 mM), the EPSC evoked by the second stimulus is facilitated with respect to the first EPSC in synapses from both WT (45 ± 3%, n = 5) and R192Q KI mice (44 ± 2%, n = 7).

Evoked EPSCs

We analyzed transmitter release triggered by R192Q-mutated Cav2.1 channels. EPSCs evoked in both WT and R192Q KI mice showed synchronous release, displaying an all or nothing behavior and having amplitudes (above threshold) that were independent of the stimulus intensity. EPSCs were abolished by ω-agatoxin IVA (200 nM), indicating that only P/Q-type channels are mediating Ca2+ influx responsible for transmitter release (data not shown). Figure 2D shows EPSCs recorded from the soma of an MNTB neuron under voltage-clamp conditions at a holding potential of −70 mV. Mean EPSC amplitudes were identical: 10.6 ± 0.6 nA (n = 46) for WT and 10.7 ± 0.5 nA (n = 65) for KI (Student's t-test, P = 0.42).

Activity-dependent facilitation of presynaptic Ca2+ currents and transmitter release

Presynaptic calcium currents at the calyx of Held display Ca2+-dependent facilitation that accounts for part of the facilitation of transmitter release, particularly under low depletion conditions (i.e., low Ca2+- high Mg2+; Felmy et al. 2003; Inchauspe et al. 2004; Muller et al. 2008). Pairs of AP waveforms with short interpulse intervals (5–10 ms) were applied under voltage clamp to the presynaptic terminals. With 2 mM [Ca2+]in the external solution, the second IpCa showed 12 ± 2% facilitation in R192Q KI (n = 12) and 10 ± 1% in WT mice (n = 10; Fig. 2E). In 0.6 mM [Ca2+] and 2 mM [Mg2+], no difference was observed in EPSC paired-pulse facilitation: 44 ± 2% (n = 7) at R192Q KI and 45 ± 3% (n = 5) in WT calyx of Held synapses (Fig. 2F).

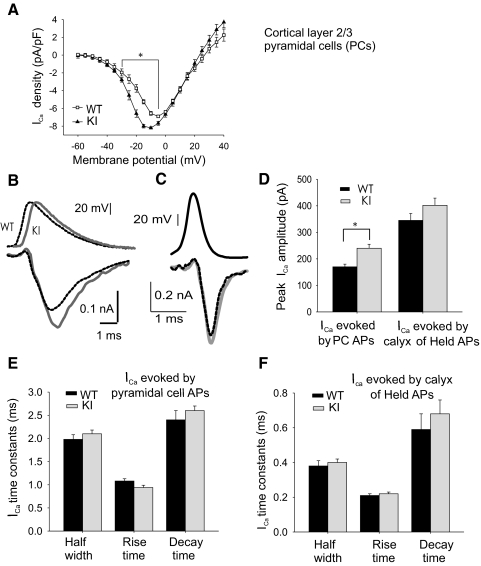

Ca2+ currents (ICa) in cortical layer 2/3 pyramidal cells

Because migraine has been suggested to be closely related to altered properties in cortical circuits (Aurora and Wilkinson 2007), P/Q-type Ca2+ currents (Ica) were recorded from layer 2/3 motor cortex PCs in brain slices from P10–P11 WT and R192Q KI mice. To isolate P/Q type Ca2+ channels, N- and L-type blockers (ω-CgTxGVIA 1 μM and nitrendipine 10 μM, respectively) were added to the ACSF solution. Current-voltage curves (Fig. 3A) showed a 6 mV hyperpolarizing shift in R192Q KI neurons, similar to data presented above from the calyx of Held and that published by Tottene et al. (2009) in pyramidal cells. P/Q-type Ca2+ currents were also evoked by AP waveforms previously recorded under current clamp from the same layer 2/3 PCs under the same experimental conditions mentioned above. Longer duration and lower amplitude APs were observed in pyramidal cells compared with the calyx of Held (Fig. 3B, top traces). The R192Q mutation significantly increased AP-evoked Ca2+ currents (Fig. 3, B, bottom traces, and D, left bars). In contrast, when P/Q-type ICa in layer 2/3 PCs was evoked by AP templates recorded at the calyx of Held, no difference in amplitude was observed between WT and R192Q KI mice (Fig. 3, C, bottom traces, and D, right bars). ICa kinetic parameters present no significant differences between WT and KI (Fig. 3E for PC AP-evoked ICa and Fig. 3F for calyx of Held AP-evoked ICa).

Fig. 3.

AP-evoked P/Q-type Ca2+ currents (ICa) in layer 2/3 pyramidal cells (PC) from WT and KI cortical slices. A: P/Q-type current density as a function of voltage in WT and R192Q KI layer 2/3 pyramidal cells (PCs). Normalized I-V curves were multiplied by the average maximal current density (6.9 ± 0.3 pA/pF, n = 7 for WT and 8.2 ± 0.2 pA/pF, n = 7 for KI). *Significant differences between WT and R192Q KI mice (P < 0.001, 1-way ANOVA RM, Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc). B: top traces: AP waveforms recorded in PCs (dotted black for WT and gray for R192Q KI mice, offset for better visualization). WT PCs had APs with a mean rise time of 0.53 ± 0.05 ms; half-width of 1.97 ± 0.08 ms; decay time of 3.1 ± 0.2 ms; and potential amplitude of 90 ± 2 mV (n = 5). Similar values were measured from KI mice (rise time: 0.52 ± 0.07 ms; half-width: 1.72 ± 0.12 ms; decay time: 2.9 ± 0.4 ms; potential amplitude: 92 ± 2 mV; n = 6). Bottom traces: ICa elicited by the above APs in the same cells (black for WT and gray for R192Q KI mice). C: ICa in PC (bottom traces, dotted black for WT, gray for KI mice) evoked by the AP waveforms (top traces) recorded at the calyx of Held presynaptic terminals. D: mean ICa amplitude evoked in PCs by either AP waveforms showed in B and C. ICa amplitudes from KI PCs (240 ± 15 pA, n = 25) are 41% larger than those from WT PCs (170 ± 10 pA, n = 18, P = 0.01) when evoked by PC APs. ICa was not statistically different when evoked by calyx of Held APs. Mean amplitudes were 402 ± 27 pA for R192Q KI mice (n = 25) and 345 ± 26 pA for WT mice (n = 18; Student's t-test, P = 0.07). E: kinetic parameters of Ca2+ currents generated in PCs by AP waveforms corresponding to the same cells (n = 18 for WT and n = 25 for R192Q KI mice). F: kinetic parameters of Ca2+ currents generated in PCs by AP waveforms of the calyx of Held (n = 18 for WT and n = 25 for R192Q KI mice).

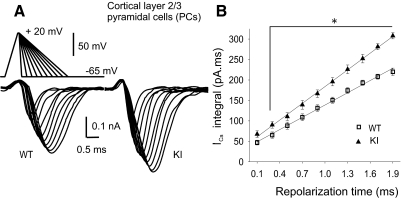

To systematically analyze the influence of AP time courses on ICa, we applied pseudo-APs with increasing repolarization times (from 0.1 to 1.9 ms) without changing the amplitude and depolarization time (0.5 ms), as shown in Fig. 4A. The ICa integral was plotted against the repolarization time (Fig. 4B). The slope of the linear regression was larger for R192Q KI PCs compared with WT, confirming that ICa influx in R192Q KI PCs is larger when the waveform repolarization is prolonged.

Fig. 4.

Dependence of calcium influx with the AP repolarization rate. A: recordings of ICa in response to AP-like voltage ramps (from −65 to +20 mV, rise time of 0.5 ms, plateau duration of 0.05 ms, and increasing decay times from 0.1 to 1.9 ms with 0.2 ms increments) in WT and R192Q KI pyramidal cells. B: ICa-mediated charge (ICa integral) is plotted as a function of the AP repolarization time. Solid lines show the linear regression of the data. Slope value is larger for R192Q KI mice (136 ± 3 pA, n = 12) than for WT mice (99 ± 3 pA, n = 13, Student's t-test, P = 0.002). *Significant differences between WT and R192Q KI mice (P < 0.006, 1-way ANOVA RM, Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc).

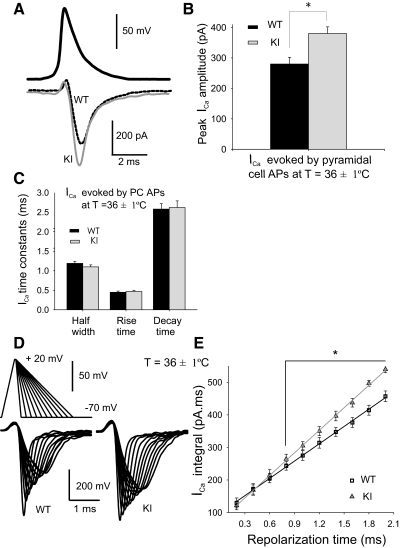

Ca2+ currents (ICa) in cortical layer 2/3 pyramidal cells at physiological temperature

Temperature is well known to affect APs kinetics and voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. We tested whether the alterations described above at room temperature were reproduced at physiological temperature by recording APs from cortical layer 2/3 PCs at a temperature of 36 ± 1°C (Fig. 5A, top trace) and used these AP waveforms to generate ICa in PCs from both WT and R192Q KI mice (Fig. 5A, bottom traces). ICa recorded from R192Q KI PCs had bigger amplitudes compared with those recorded from WT (P = 0.001 Student's t-test; Fig. 5B). There were no significant differences in the kinetics of the Ca2+ currents between WT and R192Q KI mice (Fig. 5C). We then evoked ICa using ramp-shaped waveforms with a rise time of 0.5 ms and different repolarization times to study the dependence of ICa-mediated charge with the duration of the APs at a temperature of 36 ± 1°C (Fig. 5D). We found a linear dependence of the calcium influx (i.e., time integral of the ICa) with repolarization time. The slope of the linear regression was significantly bigger in KI mice compared with WT mice (P = 0.008 Student's t-test; Fig. 6E). These results confirm that, at physiological temperature, the FHM-1 mutation also induce an increase in Ca2+ currents when these are evoked by cortical PC-like APs.

Fig. 5.

AP-evoked P/Q-type Ca2+ currents (ICa) in layer 2/3 pyramidal cells (PCs) from WT and KI cortical slices at physiological temperature. A: top traces: AP waveforms recorded in PCs at physiological temperature (36 ± 1°C). Mean rise time was 0.41 ± 0.03 ms; half-width was 0.93 ± 0.04 ms; decay time was 1.9 ± 0.3 ms; and potential amplitude was 85 ± 3 mV (n = 6). Bottom traces: ICa elicited by the above APs in PC at physiologival temperature (black for WT and gray for R192Q KI mice). B: mean ICa amplitude evoked in PCs by their own APs at physiological temperature are 35% larger in R192Q KI mice (380 ± 22, n = 27, P = 0.001 Student's t-test) than in WT mice (280 ± 22 pA, n = 32). C: kinetic parameters of Ca2+ currents generated in PCs by AP waveforms corresponding to the same cells (n = 32 for WT and n = 27 for R192Q KI) at 36 ± 1°C. D: recordings of ICa in response to AP-like voltage ramps (from −65 to +20 mV, rise time of 0.5 ms, plateau duration of 0.05 ms, and increasing decay times from 0.1 to 2.1 ms with 0.2 ms increments) in WT and R192Q KI pyramidal cells at 36 ± 1°C. E: ICa-mediated charge (ICa integral) is plotted as a function of the AP repolarization time. Solid lines show the linear regression of the data. Slope value is larger for R192Q KI mice (230 ± 3 pA, n = 18) than for WT mice (177 ± 2 pA, n = 18, Student's t-test, P = 0.008). *Significant differences between WT and R192Q KI mice (P < 0.005, 1-way ANOVA RM, Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc).

Fig. 6.

IpCa at the calyx of Held evoked by long AP waveforms recorded at pyramidal cells (PCs). A: top traces: AP waveforms recorded in PCs (dotted black for WT and gray for R192Q KI mice, offset for better visualization, see parameters in Fig. 3B). Bottom traces: IpCa elicited by the above APs at the calyx of Held presynaptic terminals (dotted black for WT and gray for R192Q KI mice). B: mean IpCa amplitudes evoked at the calyx of Held presynaptic terminals by the PCs APs are 41% larger in KI mice (650 ± 58 pA, n = 24) than in WT mice (460 ± 44 pA, n = 11, P = 0.018, Student's t-test). C: kinetic parameters of presynaptic Ca2+ currents at the calyx of Held synapses generated by AP waveforms from pyramidal cells (n = 11 for WT and n = 24 for R192Q KI mice).

IpCa elicited by longer duration APs waveforms: calyx of Held versus cortical pyramidal cell APs

Tottene et al. (2009) found a gain of function of excitatory neurotransmission at pyramidal cells from R192Q KI synapses. They proposed that the increased probability of glutamate release at cortical layer 2/3 pyramidal cells results from an increased AP-evoked Ca2+ influx. Our results at the calyx of Held synapse indicated that the activation of the Ca2+ at more negative potentials did not imply an increment in AP-evoked Ca2+ currents. Therefore we decided to study IpCa at the presynaptic terminals from WT and R192Q KI mice with APs previously recorded from layer 2/3 pyramidal cells, which have longer duration and lower amplitude compared with the calyx of Held (Fig. 6A, top traces). When evoked by these PC APs, IpCa from R192Q KI presynaptic calyceal terminals were significantly bigger compared with WT (Fig. 6, A bottom traces, and B). However, kinetic parameters of the IpCa at the calyx of Held evoked by the PC APs were not different between WT and KI (Fig. 6C).

In conclusion, our results suggest that activation of Ca2+ channels at more hyperpolarizing potentials led to higher inward Ca2+ influx during long duration/small amplitude APs (i.e., PC-like APs). However, negligible differences were observed when Ca2+ currents were elicited by short-duration/large-amplitude APs (i.e., calyx of Held-like APs). This may explain the unaltered inhibitory neurotransmission observed by Tottene et al. (2009) at the fast spiking interneuron- pyramidal cell synapses. Cortical layer 5/6 fast spiking interneurons (that have inhibitory projections into the pair connected PCs, generating brief inhibitory postsynaptic potentials) have APs that are comparable in duration to those at the calyx of Held. Supplementary Fig. S1A1 shows representative repetitive AP firing from cortical layer 5/6 fast-spiking (FS) interneurons. In Supplementary Fig. S1B, we superimposed APs from the calyx of Held, the cortical layer 2/3 PCs and from the cortical layer 5/6 fast spiking interneurons recorded from WT mice. The duration of APs from interneurons is known to be reduced at physiological temperature and in older animals (Ali et al. 2007).

DISCUSSION

Using KI mice carrying the pathogenic FHM-1 mutation R192Q in the α1A subunit of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels, we evaluated the functional consequences of this mutation for Ca2+ currents from different neuronal types. At the calyx of Held synapse, the FHM-1 mutation generates a hyperpolarizing shift of both activation and inactivation of Cav2.1 currents compared with WT. These alterations had little effect during AP-evoked presynaptic Ca2+ current recordings. This is an important result because it provides direct evidence that the FHM-1 mutations seen in the activation/inactivation parameters are not sufficient to elicit and alter the physiological phenotype at the calyx of Held. Presynaptic Ca2+ currents are generated during AP repolarization (i.e., when testing a more depolarizing voltage range compared with the range where differences in activation and inactivation properties had been studied), and there are no differences in the I-V curves at potentials >0 mV (Fig. 1), so the absence of any gain of function in Ca2+ influx is not surprising.

At the calyx of Held in P11 and older mice, transmitter release is triggered exclusively by P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. Because no differences were observed in the AP-evoked IpCa, we expected no differences in neurotransmitter output. Accordingly, the FHM-1 mutated CaV2.1 Ca2+ channels in R192Q KI mice mediate functional transmission with similar EPSC amplitudes, release probability, and facilitation than WT mice. These results contrast with the increased release probability of the glutamatergic pyramidal cell synapses recently reported by Tottene et al. (2009). Nevertheless, they agree with the normal transmitter release observed at the fast spiking interneuron inhibitory synapses and at the neuromuscular junction studied in the same animal model (Kaja et al. 2005, Tottene et al. 2009).

Tottene et al. (2009) suggested that the increased probability of glutamate release at cortical layer 2/3 pyramidal cells results from an increased AP-evoked Ca2+ influx (related to the shift in the activation potential of the mutated Ca2+ channels), but experimental proof was not provided. To test the hypothesis that increased AP-evoked Ca2+ currents in the cortical pyramidal neurons was caused by changes in Ca2+ channel activation, the depolarization and hyperpolarization rates of the AP waveforms must be taken into account (Bischofberger et al. 2002; Li et al. 2007). We used APs recorded from the cortical layer 2/3 PCs and from the calyx of Held to compare the ICa elicited by both AP waveforms. Although ICa amplitudes recorded in WT or KI cortical layer 2/3 pyramidal cells showed no differences when elicited by calyx of Held AP waveforms, a significant increase in the amplitude of ICa was observed in R192Q KI compared with WT when pyramidal cell AP waveforms were used. Likewise, KI mice do show an enhancement in IpCa at the calyx of Held presynaptic terminals when elicited by PC APs. Thus our results strongly suggest that synapses driven by larger-amplitude and shorter-duration APs (e.g., Calyx of Held and interneurons APs) are affected less by the mutation-induced hyperpolarizing shift in voltage-dependence of Ca2+ channel activation than those driven by longer duration APs (e.g., pyramidal neurons APs). Moreover, we showed that ICa influx elicited using AP-like waveforms with different repolarization times became significantly larger in KI pyramidal neurons compared with WT when the waveform repolarization phase was prolonged. The driving force for Ca2+ ions develops during repolarization of the AP, reaching the highest values closer to the resting potential where the shift in the I-V curve found in the FHM-1 mutated channel is more significant. A decrease in the rate of repolarization will increase the contribution of the Ca2+ currents at hyperpolarizing potential values, allowing the difference in activation caused by the channel mutation to be expressed and thus leading to an increase in total Ca2+ current. We confirmed that our conclusions are also valid at physiological temperature (where APs and Ica have faster kinetics compared with room temperature). We also found that, after calcium channels were opened for a long period of time, their voltage dependence of inactivation was shifted toward more negative potential values (a −5 mV shift in half-inactivation voltages). Because this shift in voltage-dependence steady-state inactivation of the mutated calcium channels depends on previous activation of the channels during seconds, we believe that it would not introduce significant differences during simple AP-evoked Ca2+ currents. However, during repetitive firing at high frequencies, the inactivation at more hyperpolarizing potentials may prevent small conductance calcium-activated potassium channels (SK) from being activated during the train of APs. Therefore a twofold increment in excitability at cortical networks might be taking place: 1) because of increasing Ca2+ currents in KI during PC APs (voltage shift of activation) and 2) because of decreasing activation of SK currents during repetitive APs discharge. These alterations would facilitate induction and propagation of cortical spreading depression (CSD) in KI mice.

The differences in AP durations that trigger cortical excitatory and inhibitory synapses may explain the unaltered inhibitory neurotransmission observed at the fast spiking (FS) interneuron–pyramidal cell (PC) synapses and the gain of function observed at the PC–FS interneuron excitatory synapses. Ali et al. (2007) measured the APs of several types of interneurons (in juvenile/adult cats and rats) and found that multipolar interneurons that display fast spiking behavior with little or no spike accommodation have APs with half-widths between 0.2 and 0.3 ms in adult species and between 0.8 and 1.3 ms in juveniles, whereas interneurons with burst or adapting firing patterns (e.g., bitufted interneurons) exhibited APs with a wide range of half-widths (0.2–0.6 ms in adults and 1.2–1.8 ms in juveniles). The presynaptic basket cells are another example of neurons displaying fast spiking APs of very short-duration. Bucurenciu et al. (2010) precisely described that a small number of Ca2+ channels are necessary to trigger and evoke transmitter release with high temporal precision at the GABAergic basket cell–granule cells synapse in the dentate gyrus of rat hippocampal slices, supporting the hypothesis that, at inhibitory synapses controlled by short APs, the activation of the FHM-1 mutated channels at more negative potentials has little or no effect in transmitter release. The ideal test of our hypothesis would be to measure the presynaptic AP waveform in cortical nerve terminals, but this is not possible. However, a good correlation between the half-width of the somatic action potential and the synaptic events elicited in and by interneurons has been reported (Ali et al. 2007), indicating that at the presynaptic nerve terminal variations in AP duration are rather small compared with the difference in duration and amplitude observed between the calyx of Held or the fast spiking interneurons and the cortical APs. Simultaneous recording of axon and somatic APs in neocortical PCs have a similar time course, although the amplitudes of the former are reduced (Shu et al. 2007), favoring the expression of altered gating properties of the mutated Ca2+ channels.

Several mechanisms may contribute to the differential effect of FHM-1 mutations at different synapses, including different isoforms of the mutated α1 subunit or differences in the G protein modulation of Ca2+ channels (Weiss et al. 2008), but our data provide evidence that the AP time course is a crucial element in regulating Ca2+ influx into nerve terminals and determining synaptic gain of function.

GRANTS

This work was supported by Wellcome Trust Grants RM36 046 (UK) and UBACYT X-171 (Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina) to O. D. Uchitel, FONCYT-ANPCyT (Fondo para la investigación Científica y Tecnológica-Agencia Nacional de Promocion Científica y Tecnológica) BID 1728 OC.AR. PICT 2007-1009, PICT 2008–2019, and PIDRI-PRH 2007 to F. J. Urbano, and the Centre for Medical Systems Biology in the framework of the Netherlands Genomics Initiative to A.M.J.M van den Maagdenberg.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. E. Martin and P. Felman for invaluable technical and administrative assistance.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains supplemental data.

REFERENCES

- Ali et al., 2007.Ali AB, Bannister AP, Thomson AM. Robust correlations between action potential duration and the properties of synaptic connections in layer 4 interneurones in neocortical slices from juvenile rats and adult rat and cat. J Physiol 580: 149–169, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aurora and Wilkinson, 2007.Aurora SK, Wilkinson F. The brain is hyperexcitable in migraine. Cephalalgia 27: 1442–1453, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett et al., 2005.Barrett CF, Cao YQ, Tsien RW. Gating deficiency in a familial hemiplegic migraine type 1 mutant P/Q-type calcium channel. J Biol Chem 280: 24064–24071, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischofberger et al., 2002.Bischofberger J, Geiger JR, Jonas P. Timing and efficacy of Ca2+ channel activation in hippocampal mossy fiber boutons. J Neurosci 22: 10593–10602, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst and Sakmann, 1999.Borst JG, Sakmann B. Effect of changes in action potential shape on calcium currents and transmitter release in a calyx-type synapse of the rat auditory brainstem. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 354: 347–355, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucurenciu et al., 2010.Bucurenciu I, Bischofberger J, Jonas P. A small number of open Ca2+ channels trigger transmitter release at a central GABAergic synapse. Nat Neurosci 13: 19–21, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao and Tsien, 2005.Cao YQ, Tsien RW. Effects of familial hemiplegic migraine type 1 mutations on neuronal P/Q-type Ca2+ channel activity and inhibitory synaptic transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 2590–2595, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedchyshyn and Wang, 2005.Fedchyshyn MJ, Wang L. Developmental transformation of the release modality at the calyx of Held synapse. J Neurosci 25: 4131–4140, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felmy et al., 2003.Felmy F, Neher E, Schneggenburger R. Probing the intracellular calcium sensitivity of transmitter release during synaptic facilitation. Neuron 37: 801–811, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari et al., 2008.Ferrari MD, van den Maagdenberg AMJM, Frants RR, Goadsby PJ. Migraine as a cerebral ionopathy with impaired central sensory processing. In: Molecular Neurology, edited by Waxman SG. Oxford, UK: Elsevier, 2008, p. 439–461 [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe, 1994.Forsythe ID. Direct patch recording from identified presynaptic terminals mediating glutamatergic EPSCs in the rat CNS, in vitro. J Physiol 479: 381–387, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González Inchauspe et al., 2007.González Inchauspe C, Forsythe ID, Uchitel OD. Changes in synaptic transmission properties due to the expression of N-type calcium channels at the calyx of Held synapse of mice lacking P/Q-type calcium channels. J Physiol 584: 835–851, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hans et al., 1999.Hans M, Luvisetto S, Williams ME, Spagnolo M, Urrutia A, Tottene A, Brust PF, Johnson EC, Harpold MM, Stauderman KA, Pietrobon D. Functional consequences of mutations in the human α1A calcium channel subunit linked to familial hemiplegic migraine. J Neurosci 19: 1610–1619, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inchauspe et al., 2004.Inchauspe C, Martini FJ, Forsythe ID, Uchitel OD. Functional compensation of P/Q by N-type channels blocks short-term plasticity at the calyx of Held presynaptic terminal. J Neurosci 24: 10379–10383, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki et al., 2000.Iwasaki S, Momiyama A, Uchitel OD, Takahashi T. Developmental changes in calcium channel types mediating central synaptic transmission. J Neurosci 20: 59–65, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki and Takahashi, 1998.Iwasaki S, Takahashi T. Developmental changes in calcium channel types mediating synaptic transmission in rat auditory brainstem. J Physiol 509: 419–423, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaja et al., 2005.Kaja S, van de Ven RC, Broos LA, Veldman H, van Dijk JG, Verschuuren JJ, Frants RR, Ferrari MD, van den Maagdenberg AM, Plomp JJ. Gene dosage-dependent transmitter release changes at neuromuscular synapses of CACNA1A R192Q knockin mice are non-progressive and do not lead to morphological changes or muscle weakness. Neuroscience 135: 81–95, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus et al., 1998.Kraus RL, Sinnegger MJ, Glossmann H, Hering S, Striessnig J. Familial hemiplegic migraine mutations change α1A Ca2+ channel kinetics. J Biol Chem 273: 5586–5590, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus et al., 2000.Kraus RL, Sinnegger MJ, Koschak A, Glossmann H, Stenirri S, Carrera P, Striessnig J. Three new familial hemiplegic migraine mutants affect P/Q-type Ca(2+) channel kinetics. J Biol Chem 275: 9239–9243, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauritzen, 1994.Lauritzen M. Pathophysiology of the migraine aura: the spreading depression theory. Brain 117: 199–210, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li et al., 2007.Li L, Bischofberger J, Jonas P. Differential gating and recruitment of P/Q-,N-, and R-type Ca2+ channels in hippocampal mossy fiber boutons. J Neurosci 27: 13420–13429, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller et al., 2008.Muller M, Felmy F, Schneggenburger R. A limited contribution of Ca2+ current facilitation to paired-pulse facilitation of transmitter release at the rat calyx of Held. J Physiol 586: 5503–5520, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu et al., 2007.Shu Y, Duque A, Yu Y, Haider B, McCormick DA. Properties of action-potential initiation in neocortical pyramidal cells: evidence from whole cell axon recordings. J Neurophysiol 97: 746–760, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, 2005.Takahashi T. Dynamic aspects of presynaptic calcium currents mediating synaptic transmisión. Cell Calcium 37: 507–511, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tottene et al., 2009.Tottene A, Conti R, Fabbro A, Vecchia D, Shapovalova M, Santello M, van den Maagdenberg AM, Ferrari MD, Pietrobon D. Enhanced excitatory transmission at cortical synapses as the basis for facilitated spreading depression in Ca(v)2.1 knockin migraine mice. Neuron 61: 762–773, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tottene et al., 2002.Tottene A, Fellin T, Pagnutti S, Luvisetto S, Striessnig J, Fletcher C, Pietrobon D. Familial hemiplegic migraine mutations increase Ca2+ influx through single human CaV2.1 channels and decrease maximal CaV2.1 current density in neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 13284–13289, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tottene et al., 2005.Tottene A, Pivotto F, Fellin T, Cesetti T, van den Maagdenberg AMJM, Pietrobon D. Specific kinetic alterations of human CaV2.1 calcium channels produced by mutation S218L causing familial hemiplegic migraine and delayed cerebral edema and coma after minor head trauma. J Biol Chem 280: 17678–17686, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Maagdenberg et al., 2004.van den Maagdenberg AM, Pietrobon D, Pizzorusso T, Kaja S, Broos LA, Cesetti T, van de Ven RC, Tottene A, van der Kaa J, Plomp JJ, Frants RR, Ferrari MD. A Cacna1a knockin migraine mouse model with increased susceptibility to cortical spreading depression. Neuron 41: 701–710, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss et al., 2008.Weiss N, Sandoval A, Felix R, Van den Maagdenberg AM, De Waard M. The S218L familial hemiplegic migraine mutation promotes deinhibition of Cav2.1 calcium channels during direct G-protein regulation. Pfluegers 457: 315–326, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang and Wang, 2006.Yang YM, Wang LY. Amplitude and kinetics of action potential-evoked Ca2+ current and its efficacy in triggering transmitter release at the developing calyx of Held synapse. J Neurosci 23: 5698–5708, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.