Abstract

Introduction

Resistance to angiogenesis inhibition can occur through the up-regulation of alternative mediators of neovascularization. We used a combination of angiogenesis inhibitors with different mechanisms of action, interferon-β (IFN-β) and rapamycin, to target multiple angiogenic pathways to treat neuroblastoma xenografts.

Methods

Subcutaneous and retroperitoneal neuroblastoma xenografts (NB-1691 and SK-N-AS) were used. Continuous delivery of IFN-β was achieved with AAV-mediated, liver-targeted gene transfer. Rapamycin was delivered intraperitoneally (5 mg/kg/day). After 2 weeks of treatment, tumor size was measured, and tumor vasculature was evaluated with intravital microscopy and immunohistochemistry.

Results

Rapamycin and IFN-β, alone and in combination, had little effect on tumor cell viability in vitro. In vivo, combination therapy led to a decreased number of intratumoral vessels (69% of control), and the remaining vessels had an altered phenotype, being covered with significantly more pericytes (13X control). Final tumor size was significantly less than controls in all tumor models, with combination therapy having a greater antitumor effect than either monotherapy.

Conclusion

The combination of interferon-β and rapamycin altered the vasculature of neuroblastoma xenografts and resulted in significant tumor inhibition. The use of combinations of antiangiogenic agents should be further evaluated for the treatment of neuroblastoma and other solid tumors.

Keywords: interferon-beta, rapamycin, neuroblastoma, angiogenesis

Introduction

Neuroblastoma is the most common extracranial solid tumor of childhood. Although treatment options have increased over the past forty years and include a multi-modality approach, children with high-risk disease still have a low overall survival rate of <40%. Although localized tumors are curable with surgical resection alone, most advanced disease is ultimately resistant to adjuvant therapy. Patients with recurrent low-risk or intermediate-risk tumors can be treated with salvage chemotherapy while patients with relapsed high-risk disease invariably succumb to their disease (1).

Tumor angiogenesis is a complex process in which tumors release cytokines that stimulate host tumor vessels to branch and grow toward the tumors, allowing for their growth and metastasis. Angiogenesis begins with basement membrane degradation, endothelial cell migration and invasion into the extracellular matrix, followed by endothelial cell proliferation and capillary tube formation (2). The resulting tumor vasculature is highly abnormal with tortuous, dilated vessels that are disorganized and poorly fortified with perivascular cells (3).

The exact mechanism of action of most angiogenesis inhibitors is not completely understood, but they are thought to act on various stages of blood vessel formation. Possible targets are angiogenic cytokines secreted by tumors, attacking the endothelial cells directly, or by inhibiting secretion or action of proteins from endothelial cells necessary for new blood vessel formation (5). An increase in perivascular investment is an alternate mechanism by which changing the phenotype of tumor blood vessels may impact the ability of a tumor to grow. This increase in perivascular cells can decrease local endothelial cell proliferation and may affect the ability of endothelial cells to extravasate into tissue, thereby preventing the formation of new blood vessels required to meet the needs of an expanding tumor. This “normalization” of the tumor vasculature has been shown to increase the delivery of cytotoxic agents to tumors as well as sensitizing tumors to the effect of radiation, which requires oxygen for its effect (4).

Interferon-beta (IFN-β) is a regulatory cytokine produced by host cells in response to foreign antigens. It has multiple cellular effects including an increase in tumor cell apoptosis, modulation of angiogenesis, and immunomodulation (6). IFN-β is active against many cancers, although its clinical utility has been limited by its short half-life and systemic toxicity. We have previously shown that continuous therapy with a liver-targeted, adeno-associated viral vector expressing IFN-β decreased neuroblastoma growth through maturation of tumor blood vessels (7). The vessels, highly invested with pericytes, were unable to remodel and expand in response to the increasing needs of an enlarging tumor. However, tumor regression was not achieved. Therefore, an agent which might synergize with IFN-β for effective combination therapy was sought. Rapamycin is an anticancer agent that acts through inhibition of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway. The mTOR pathway is important in the progression of many cancers, and therefore has become the target of many anticancer therapies (8). Rapamycin has been shown to be effective against some neuroblastoma cell lines in animal models (9). In addition to its cytotoxic activity, rapamycin has an effect on angiogenesis by down regulating endothelial cell activation (9, 10). Since IFN-β and rapamycin affect tumor angiogenesis through different mechanisms, we hypothesized that the combination of IFN-β and rapamycin would decrease tumor neovascularization and, therefore, tumor growth in human neuroblastoma xenografts.

Methods

In vitro experiments

Two established neuroblastoma cell lines were utilized. NB-1691 cells provided by Peter Houghton (St Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN) and SK-N-AS cells purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Mannassas, VA). These cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 culture media (Hyclone, Logan, UT) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (Hyclone), 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin and 2 mM L-glutamine (GIBCO BRL, Grand Island, NY). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs, Lonza, Walkersville Inc, Walkersville, MD) were maintained in EGM2 media (Lonza) supplemented with growth factors (SingleQuots, Lonza).

NB-1691 cells were plated at a density of 3×105 cells per mL and SK-N-AS cells were plated at a density of 1×105 cells per mL each in a 24-well plate. Cells were allowed to adhere for 24 hours. Six wells were then treated with 100 units of recombinant human interferon-beta (rhIFN-β). After 24 hours of exposure to rhIFN-β, 3 untreated wells and 3 rhIFN-β treated wells were treated with rapamycin (100ng/mL). Twenty-four hours later, cells were trypsinized and counted using a hemocytometer.

Adeno-associated virus vector production

Adeno-associated virus vectors (AAV) were used to establish continuous, long-term delivery of human IFN-β in vivo. Construction of the pAV2 hIFN-β vector plasmid has been described previously (11). This vector plasmid includes the CMV-IE enhancer, β-actin promoter, a chicken β-actin/rabbit β-globin composite intron and a rabbit β-globin polyadenylation signal mediating the expression of the cDNA for human IFN-β. The hIFN-β cDNA was purchased from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA). Recombinant AAV vectors pseudotyped with serotype 8 capsid were generated by the method described previously using the pAAV8-2 plasmid provided by J. Wilson (Philadelphia, PA) (12). These AAV2/8 vectors were purified using ion exchange chromatography (13).

Animal experiments

All animal experiments were conducted with male, CB17 SCID mice (Charles Rivers Laboratory, Boston, MA) at 4–6 weeks of age. Heterotopic tumors were established by injecting 3×106 NB-1691 cells in 200 μL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) into the subcutaneous space of the right flank. The length and width of tumors was measured with handheld calipers, and tumor volume was calculated as length × width 2/2. Four weeks after injection, tumors averaged 440.0 ± 67.6 mm3 and were size-matched into four cohorts. One cohort served as the untreated control, one cohort received 7.5×109 vector particles of AAV-hIFN-β via tail vein injection on day 0 (day of size matching), one cohort received rapamycin (5 mg/kg) intraperitoneally once daily for 5 days per week for a total of two weeks, and the final cohort received AAV-hIFN-β (7.5×109 vector particles) via tail vein on day 0 followed by rapamycin (5mg/kg) on day 3, which was continued intraperitoneally once daily for 5 days per week for a total of two weeks.

Orthotopic tumors were established by injecting 2×106 NB-1691 or SK-N-AS cells in 100 μL of PBS into the retroperitoneal space behind the left adrenal gland. Tumor growth was monitored with ultrasonography using a Vevo 770 (Visual Sonics, Toronto, Ontario) small animal ultrasound machine using a 40 MHz linear transducer. Tumor volume was calculated using three-dimensional ultrasonography and Visual Sonics software (Toronto, Ontario). Mice were size matched two weeks after tumor cell inoculation into four cohorts with the same treatment schedule as described previously. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

Quantification of systemic AAV-mediated hIFN-β expression was performed on mouse plasma utilizing a commercially available sandwich immunoassay (ELISA, TRB INC, Fujirebio INC, Tokyo, Japan). The sensitivity range for this assay is 250 to 10,000 pg/mL.

Tumor immunohistochemistry

Formalin fixed, paraffin embedded 4μm thick tumor sections were stained with rat anti-mouse CD34 (RAM 34, PharMingen, San Diego, CA) and mouse anti-human smooth muscle actin (clone 1A4, DAKO, Carpenteria, CA) antibodies as previously described (14). Stained tumor sections were viewed and digitally photographed using an Olympus U-SPT microscope equipped with brightfield illumumination with an attached CCD camera. Three images at 400X magnification were captured for each tumor sample concentrating on well-vascularized, non-necrotic regions. These were saved as JPEG files for further processing in Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems Incorporated, San Jose, CA). Positive staining was highlighted by eliminating other colors with the magic wand tool at a tolerance of 60 pixels in Adobe Photoshop (San Jose, CA). Once only brown color was left in the picture, the picture was gray scaled and then made monochrome using a 50% threshold. The monochrome bitmap image was then analyzed for pixels using the NIH analysis software, ImageJ. Data are presented as the mean number of positive pixels/tumor section.

Intravital microscopy

A midline incision was made and the abdominal viscera were shifted to the right side of the abdomen to allow for visualization of the left-sided retroperitoneal tumors. The superficial tumor vasculature was examined using an industrial scale microscope (model MM-40, Nikon USA, Melville, NY) with a digital camera (Photometric CoolSnap FX, Roper Scientific, Trenton, NJ) and fluorescent (100 W mercury) light source. Images were acquired at 40X magnification and analyzed using MetaMorph software (Universal Imaging Co., West Chester, PA) (15).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) and were compared using an unpaired Student’s t-test. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Data were analyzed and graphed using SigmaPlot (Version 9, SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL).

Results

Effect of interferon-beta and rapamycin on neuroblastoma cells in vitro

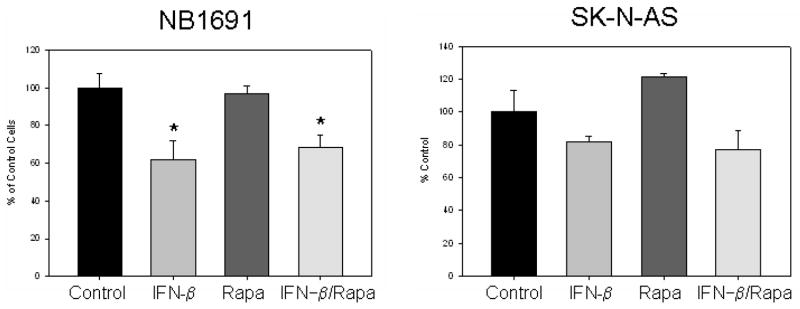

The effect of IFN-β and rapamycin was initially evaluated in vitro to determine the direct toxicity of the two drugs. IFN-β alone had a modest effect on both neuroblastoma cell Figure 1 lines, NB1691 and SK-N-AS, with cell counts 70% of control cells (Figure 1). Treatment with rapamycin had no effect on cell counts in either cell line. The combination of IFN-β followed by rapamycin did not improve the effect of IFN-β alone. Treatment with rapamycin prior to IFN-β showed similar results (data not shown).

Figure 1.

In vitro effect of interferon-beta and rapamycin on the proliferation of two human neuroblastoma cell lines. IFN-β alone had minimal effect on neuroblastoma cells in culture, while rapamycin had no effect in vitro. *p = 0.03 vs control.

Effect of rapamycin on human endothelial cells

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells were treated with rapamycin 100ng/mL for 48 hours. Rapamycin decreased endothelial cell counts by nearly fifty percent (5.73 ± 0.4 ×105 cells/mL vs 3.0 ± 0.4 ×105 cells/mL, p = 0.008).

Effect of interferon-beta and rapamycin on tumor vasculature

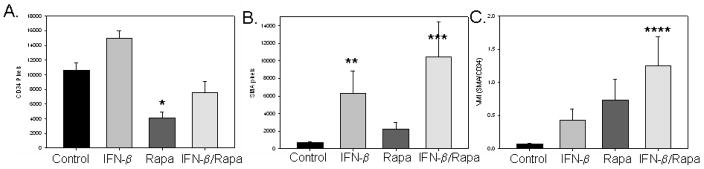

After two weeks of therapy, the effect on endothelial cells and perivascular cells within neuroblastoma xenografts was assessed with immunohistochemistry performed on samples from excised tumors. IFN-β alone actually increased the number of intratumoral endothelial cells while rapamycin greatly decreased the number of endothelial cells (Figure 2A). The combination of the two agents lead to an overall decrease in the number of endothelial cells as indicated by a lower number of CD34 stained cells. A much different effect was seen on perivascular cells. Although rapamycin had no effect on perivascular cells, IFN-β increased the amount of investing perivascular cells supporting tumor vessels (Figure 2B). The combination of IFN-β and rapamycin profoundly increased the number of perivascular cells fortifying the remaining blood vessels, leading to an increase in the vessel maturity index, the ratio of perivascular cells to endothelial cells (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Effect of interferon-beta and rapamcyin on tumor angiogenesis in neuroblastoma xenografts. IFN-β increased perivascular cells (α-SMA) while rapamycin decreased endothelial cells (CD43), leading to an overall increase in the vessel maturity index (VMI). *p = 0.00004, **p = 0.003, ***p=0.03, ****p = 0.0006

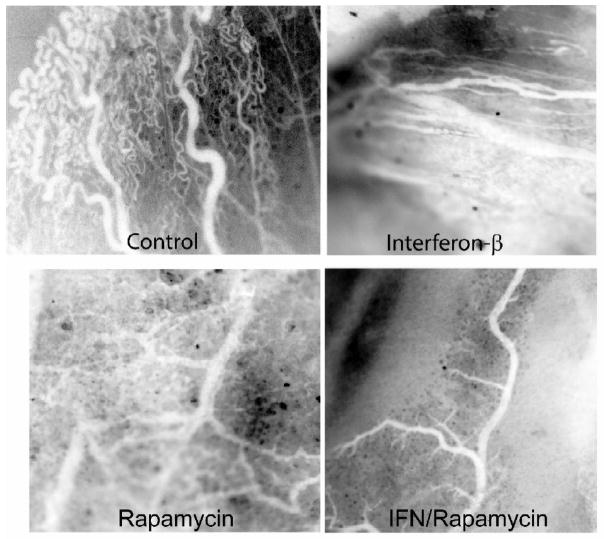

Blood vessel morphology was also examined with intravital microscopy (Figure 3). Control tumor blood vessels were tortuous and disorganized with numerous branches. Blood vessels of tumors treated with IFN-β were more organized with fewer branches and less tortuosity. Treatment with rapamycin decreased the number of blood vessels leaving a few, large tortuous blood vessels supplying the tumor. Examination of tumors treated with the combination of IFN-β and rapamycin revealed few, well-fortified blood vessels with minimal branching.

Figure 3.

Effect on tumor blood vessel structure. Intravital images of tumor blood vessels show an overall decrease in blood vessels in the combination treated tumors with less branching and tortuosity.

Effect of interferon-beta and rapamycin on tumor xenografts

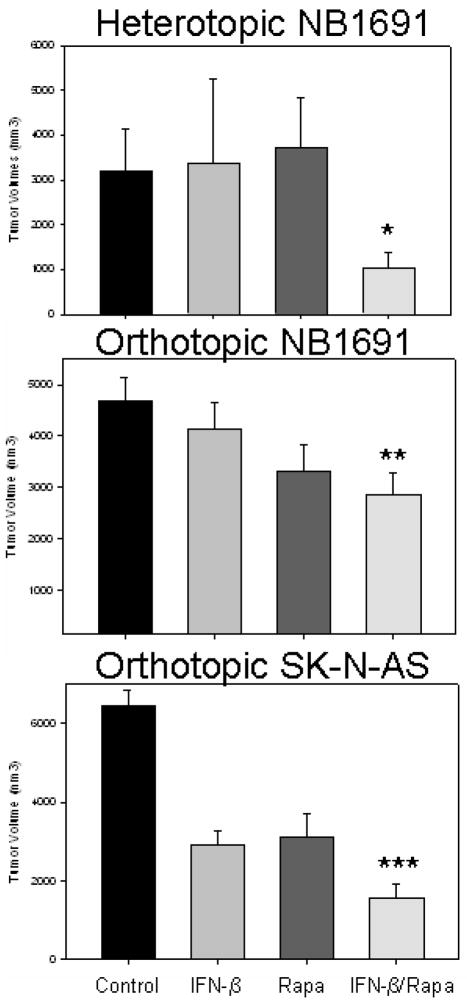

NB1691 cells were implanted in the subcutaneous space in the flanks of CB17 SCID mice and retroperitoneally behind the left adrenal gland. In the heterotopic (subcutaneous) model, treatment began when tumors averaged 440.0 ± 67.6 mm3. Two weeks after intravenous injection of AAV-hIFN-β (7.5×109 vector particles), systemic IFN levels were 2482.0 ± 495.2 pg/mL. After two weeks of treatment with IFN-β or rapamycin, no effect was seen on tumor size when compared to control tumors (3379.8 ± 1886.9 [IFN], 3710.6 ± 1137.4 [rapamycin] vs 3194.2 ± 943.0 mm3 [control], Fig 4A). However, when mice were treated with the same doses of IFN-β and rapamycin, in combination, tumor growth was restricted to 1044.0 ± 338.8 mm3, which was significantly smaller than controls (p = 0.03) and rapamycin treated tumors (p = 0.03).

Figure 4.

Interferon-beta and rapamycin restricted neuroblastoma xenograft tumor growth

The combination of IFN-β and rapamycin significantly restricted tumor growth in both a heterotopic (A) and orthopic model (B/C). *p = 0.03, **p = 0.001, ***p = 0.00004

In the orthotopic (retroperitoneal) model, treatment was started when tumors reached an average of 162.6 ± 18.7 mm3 based on three-dimensional ultrasonography. After two weeks of treatment with IFN-β, tumors were slightly smaller than control tumors (4142.6 ± 1347.0 vs 4677.1 ± 464.6 mm3, p = 0.45, Fig 4B). Two weeks of treatment with rapamycin decreased tumors to a greater degree than seen in the heterotopic model (3326.0 ± 504.1 vs 4677.1 ± 464.1 mm3, p = 0.06), which may be due to a greater dependence on the vasculature in the retroperitoneal model. Nevertheless, treatment with both IFN-β and rapamycin significantly decreased tumor size (2852.4 ± 425.7 mm3) when compared to controls (p = 0.01).

To ensure the combination effect of IFN-β and rapamycin was not cell line dependent, treatment using the orthotopic model was repeated with another cell line, SK-N-AS. Similar results were seen when this cell line was treated with IFN-β and rapamycin (Fig 4C). Treatment began when tumors averaged 169.6 ± 12.4 mm3. Treatment with IFN-β and rapamycin restricted tumor growth (1551.2 ± 378.0 mm3) when compared to control tumors (6466.8 ± 393.3 mm3, p = 0.00004), tumors treated with IFN-β (2895.6 ± 367.1 mm3, p = 0.03) and rapamycin treated tumors (3131.4 ± 582.2 mm3, p = 0.05).

Discussion

Chemotherapeutic agents that target tumor angiogenesis are the subject of extensive research because of their potential to treat various types of cancer. In addition, because endothelial cells are genetically stable compared to tumor cells, they are optimal targets for cytotoxic therapies (16). The clinical efficacy of monotherapy with angiogenic agents has been disappointing, however, so trials with combination therapy have been conducted in animal studies to identify combinations which may act synergistically to increase the clinical benefit of these medications. Rapamycin is a commonly used anti-cancer agent that decreases microvessel density in neuroblastoma tumor xenografts through the down regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and by direct cytotoxicity to endothelial cells (9, 17–19). Rapamycin has been used in combination with other anti-angiogenic agents, which act through different steps in tumor angiogenesis. Sunitinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, modulates angiogenesis via down regulation of VEGF, hypoxia-induced factor-alpha (HIF1α), and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and an upregulation of angiogenin. Rapamycin in combination with sunitinib further decreased neuroblastoma growth and angiogenesis when compared to each monotherapy (17). Rapamycin has also been used successfully in conjunction with vinblastine, which destabilizes capillary tube formation leading to endothelial cell death (18–19). Both of these agents, sunitinib and vinblastine, act on endothelial cells themselves, although though different mechanisms than rapamycin. In this study, we have used rapamycin in conjunction with an anti-angiogenic agent, IFN-β, which acts on a different pathway in tumor angiogenesis.

Continuous delivery of IFN-β appears to exert its effect by stabilizing blood vessels with an increase in perivascular cells. We have previously shown that IFN-β normalizes the tumor vasculature in animal models of neuroblastoma and glioma by maturing tumor blood vessels. Investing the tumor blood vessels with perivascular cells decreases sprouting of new blood vessels, thus limiting the growth of the tumor. We have also shown that this leads to an improvement in tumor perfusion and the effect of concomitantly administered chemotherapy (7, 20–22). By utilizing a combination of angiogenesis agents that target different steps along the complex path of tumor angiogenesis, an improved therapeutic effect was obtained in this study.

The disappointing clinical response to angiogenesis inhibitors may be attributed to endothelial cell re-growth between cycles of chemotherapy and the tumor’s ability to circumvent different steps in angiogenesis. Low dose, continuous treatment with angiogenic agents may optimize their utilization by inhibiting the endothelial cell re-growth. We have previously shown that continuous production of hIFN-β was achieved via an adeno-associated viral vector that targets the liver allowing for continuous production of IFN-β. This approach was effective in decreasing tumor growth in both an orthotopic and metastatic neuroblastoma model (20–21). Rapamycin is administered orally and can be easily dosed daily on an outpatient basis. By utilizing gene therapy to administer IFN-β at a low, continuous dose in conjunction with rapamycin, an improved therapeutic effect may be obtained.

Although the combination of IFN-β and rapamycin had minimal cytotoxic effect on neuroblastoma cells in vitro, both agents had a significant effect in vivo. This discrepant response is likely due to an alteration of the tumor microenvironment via modulation of tumor angiogenesis. IFN-β altered tumor angiogenesis in murine xenografts by increasing the investment of tumor vessels with pericytes. Although this actually led to an improvement in the function of the vessels, these mature vessels are unable to remodel to support the increasing needs of an enlarging tumor mass. Rapamycin, on the other hand, acts directly on the endothelial cells with little effect on the perivascular cells. Increasing perivascular cells with IFN-β and decreasing endothelial cells with rapamycin led to tumors with fewer and better fortified vessels, which were unable to expand to allow for tumor growth. We have shown that the combination of these two agents targets two steps in tumor angiogenesis thus decreasing tumor growth in neuroblastoma xenografts.

In conclusion, the combination of interferon-β and rapamycin matured the vasculature of neuroblastoma xenografts while decreasing the overall number of tumor endothelial cells. This effect resulted in significant tumor inhibition. The combination of angiogenic agents which target various steps in tumor angiogenesis should be further evaluated for the treatment of recurrent and resistant neuroblastoma as well as other pediatric solid tumors. With a better understanding of the angiogenic cascade, appropriate combinations can be developed which target each step in tumor angiogenesis, which could have wide spread therapeutic implications.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Assisi Foundation of Memphis, the U.S. Public Health Service Childhood Solid Tumor Program Project Grant No. CA23099 the National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant No. 21766, and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

Footnotes

Presented at the AAP National Conference & Exhibition (NCE), Surgical Section, Washington, DC, October 17–20, 2009.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Maris JM, Hogarty MD, Bagatell R, Cohn SL. Neuroblastoma. Lancet. 2007;369:2106–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60983-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Risau W. Mechanisms of angiogenesis. Nature. 1997;386:671–674. doi: 10.1038/386671a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Folkman J. Role of angiogenesis in tumor growth and metastasis. Semin Oncol. 2002;29:15–18. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.37263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jain RK. Normalization of Tumor Vasculature: An Emerging Concept in Antiangiogenic Therapy. Science. 2005;307:58–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1104819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kerbel R, Folkman J. Clinical Translation of Angiogenesis inhibitors. Nature Reviews. 2002;2:727–739. doi: 10.1038/nrc905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borden EC. Interferons and Cancer: Where from Here? J Interferon & Cytokine Research. 2005;25:511–527. doi: 10.1089/jir.2005.25.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dickson PV, Hamner JB, Streck CJ, et al. Continuous delivery of IFN-beta promotes sustained maturation of intratumoral vasculature. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5(6):531–42. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guertin DA, Sabatini DM. Defining the Role of mTOR in Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnsen JI, Segerstro L, Orrego A, Elfman L, Henriksson M, Kagedal B, Eksborg S, Sveinbjornsson B, Kogner P. Inhibitors of mammalian target of rapamycin downregulate MYCN protein expression and inhibit neuroblastoma growth in vitro and in vivo. Oncogene. 2008;27(20):2910–2922. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy JD, Spalding AC, Somnay YR, Markwart S, Ray ME, Hamstra DA. Inhibition of mTOR radiosensitizes soft tissue sarcoma and tumor vasculature. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:589–96. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Streck CJ, Zhang Y, Miyamoto R, et al. Restriction of neuroblastoma angiogenesis and growth by interferon-alpha/beta. Surgery. 2004;136:183–9. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davidoff AM, Ng CY, Zhou J, Spence Y, Nathwani AC. Sex significantly influences transduction of murine liver by recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors through an androgen-dependent pathway. Blood. 2003;102:480–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davidoff AM, Ng CY, Sleep S, et al. Purification of recombinant adeno-associated virus type 8 vectors by ion exchange chromatography generates clinical grade vector stock. J Virol Methods. 2004;121:209–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spurbeck WW, Ng CY, Strom TS, Vanin EF, Davidoff AM. Enforced expression of tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-3 affects functional capillary morphogenesis and inhibits tumor growth in a murine tumor model. Blood. 2002;100:3361–8. doi: 10.1182/blood.V100.9.3361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dickson PV, Hamner JB, Sims TL, et al. Bevacizumab-induced transient remodeling of the vasculature in neuroblastoma xenografts results in improved delivery and efficacy of systemically administered chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3942–3950. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kerbel RS. Inhibition of tumor angiogenesis as a strategy to circumvent acquired resistance to anti-cancer therapeutic agents. BioEssay. 1991;13:31–36. doi: 10.1002/bies.950130106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang L, Smith KM, Chong AL, Stempak D, Yeger H, Marrano P, Thorner PS, Irwin MS, Kaplan DR, Aruchel S. In vivo antitumor and antimetastatic activity of Sunitinib in a preclinical neuroblastoma mouse model. Neoplasia. 2009;11:426–435. doi: 10.1593/neo.09166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marimpietri D, Brignole C, Nico B, Pastorino F, Pezzolo A, Piccardi F, Cilli M, Di Paolo D, Pagnan G, Longo L, Perri P, Ribatti D, Ponzoni M. Combined Therapeutic Effects of Vinblastine and Rapamycin on Human Neuroblastoma Growth, Apoptosis, and Angiogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3977. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marimpietri D, Nico B, Vacca A, Mangieri D, Catarsi P, Ponzoni1 M, Ribatti D. Synergistic inhibition of human neuroblastoma-related angiogenesis by vinblastine and rapamycin. Oncogene. 2005;24:6785–6795. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Streck SJ, Ng CY, Zhanga Y, Zhou J, Nathwani AC, Davidoff AM. Interferon-mediated anti-angiogenic therapy for neuroblastoma. Cancer Letters. 2005;228:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Streck CJ, Zhang Y, Miyamoto R, Zhou J, Ng CY, Nathwani AC, Davidoff AM. Restriction of neuroblastoma angiogenesis and growth by interferon-alpha/beta. Surgery. 2004;136:183–9. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dickson PV, Hagedorn NL, Hamner JB, Fraga CH, Ng CY, Stewart CF, Davidoff AM. Interferon beta-mediated vessel stabilization improves delivery and efficacy of systemically administered topotecan in a murine neuroblastoma model. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:160–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]