Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Promoter hypermethylation is emerging as a promising molecular strategy for early detection of cancer. We examined promoter methylation status of 1,143 cancer-associated genes to perform a global but unbiased inspection of methylated regions in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC).

STUDY DESIGN

A laboratory-based study.

SETTING

Integrated health care system.

SUBJECTS

Five samples, 2 frozen primary HNSCC biopsies and 3 HNSCC cell lines were examined.

METHODS

Whole genomic DNA was interrogated using a combination of DNA immuno-precipitation (IP) and Affymetrix whole-genome tiling arrays.

RESULTS

Of the 1,143 unique cancer genes on the array, 265 were recorded across 5 samples. Of the 265 genes, 55 were present in all 5 samples, 36 were common to 4/5 samples, 46 to 3/5, 56 to 2/5, and 72 to 1/5 samples. Hypermethylated genes in the 5 samples were cross-examined against those in PubMeth, a cancer methylation database combining text-mining and expert annotation (http://www.pubmeth.org). Of the 441 genes in PubMeth, only 33 of 441 are referenced to HNSCC. We matched 34 genes in our samples to the 441 genes in the PubMeth database. Of the 34 genes, 8 are reported in PubMeth as HNSCC associated.

CONCLUSIONS

This pilot study examined the contribution of global DNA hypermethylation to the pathogenesis of HNSCC. The whole-genome methylation approach indicated 231 new genes with methylated promoter regions not yet reported in HNSCC. Examination of this comprehensive gene panel in a larger HNSCC cohort should advance selection of HNSCC-specific candidate genes for further validation as biomakers in HNSCC.

Introduction

The study of human disease has focused primarily on genetic mechanisms. The word “epigenetic” literally means “in addition to changes in genetic sequence.” The term has evolved to include any process that alters gene activity without changing the DNA sequence. Many types of epigenetic processes have been identified--they include methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitylation, and sumolyation. Epigenetic processes are natural and essential to many organism functions, but if they occur improperly, there can be major adverse health and behavioral effects.

Perhaps the best known epigenetic process, in part because it has been easiest to study with existing technology, is DNA methylation. This is the addition (hypermethylation) or removal (hypomethylation) of a methyl group (CH3). Hypermethylation is a well described DNA modification that has been implicated in normal mammalian development,1 imprinting,2 and X chromosome inactivation.3 However, recent studies have identified hypermethylation as a probable cause in the development of various cancers.4 Aberrant methylation by DNA-methyltransferases in the CpG islands of a gene’s promoter region can lead to transcriptional repression akin to other abnormalities such as a point mutation or deletion.5 This anomalous hypermethylation has been noted in a variety of tumor-suppressor genes (TSGs), whose inactivation can lead many cells down the tumorigenesis continuum.6 In many cancers, aberrant DNA methylation of so called “CpG islands,” CpG-rich sequences frequently associated with promoters or first exons, is associated with the inappropriate transcriptional silencing of critical genes.7 These DNA methylation events represent an important tumor-specific marker occurring early in tumor progression and one that can be easily detected by PCR based methods in a manner that is minimally invasive to the patient.

In squamous head and neck cancer (HNSCC), recent comprehensive high-throughput methods have underscored the contribution of both genetic8,9 and epigenetic events,10,11 often working together,12 in the development and progression of HNSCC. We examined global promoter methylation signatures in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) of 1,143 cancer-associated genes in a pilot study to examine the feasibility of developing a global but evidence-based HNSCC gene panel.

Material and Methods

Study Cohort

Whole genomic DNA from 5 samples, 2 frozen primary HNSCC biopsies, HFHS-3T and HFHS-4T, and 3 HNSCC cell lines, UMSCC-98, UMSCC-10A, and UMSCC-1, was analyzed using a combination of DNA immune-precipitation (IP) and Affymetrix whole-genome tiling arrays to enrich and detect globally methylated sequences. The genotypes of UMSCC-98, UMSCC-10A, and UMSCC-1 were confirmed using the AmpFℓSTR® Profiler Plus® ID (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Because genetic alterations in cultured cell lines have been shown to represent an accurate snapshot of the original tumor,13 supporting the utility of cell lines from human cancers as valuable resources for ongoing investigations, the 2 frozen primary HNSCC biopsies and the 3 HNSCC cell lines were analyzed together. Characteristics of the cohort are summarized in Table 1. Patient tissue material for this study was obtained according to the Henry Ford Health System institutional review board protocols.

Table 1.

Pilot study cohort characteristics

| HFHS-3 | HFHS-4 | UMSCC-10A | UMSCC-1 | UMSCC-98 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV status | HPV16 | HPV16 | HPV16 | Not detected | HPV16 |

| p53 mutation | NI1 | NI1 | Yes2 | Yes3 | NI1 |

| Smoking & alcohol | yes | yes | NI1 | NI1 | NI1 |

| Stage | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| Site | Larynx | Tongue | Larynx | Floor of mouth | Larynx |

| Age (years) | 58 | 58 | 57 | 73 | 75 |

| Gender | Male | Male | Male | Male | Male |

NI=no information

Yes=- (Gly-> Cys) in codon 245

Yes= AGA->AGT (Arg->Ser) in codon 280 and a 30 base pair deletion in exon 8, codons 277–287

Global Methylation Methods

DNA immune-precipitation (IP) and Affymetrix GeneChip® Human Promoter 1.0R Arrays

Genpathway (www.genpathway.com), an Affymetrix-approved service provider, has developed a DNA immunoprecipitation (IP) assay using a combination of DNA immuno-precipitation (IP) and Affymetrix GeneChip® Human Promoter 1.0R Array to enrich and detect methylated sequences, respectively. DNA from cells or tissue samples is IP’ed with an antibody against 5-methyl-cytosine using IP protocols optimized to give maximum sensitivity and minimal background. The resulting DNA is analyzed on a whole-genome basis using Genpathway’s IP-on-Chip/Tiling analysis mode or on a gene-by-gene basis using Genpathway’s Query (Q-PCR) analysis mode called Methylated DNA Query (PCR). Data is returned as zip files. After the Intervals and Active Regions are defined, their exact locations along with their proximities to gene annotations and other genomic features are determined and presented in Excel spreadsheets for data analysis.

The Human Promoter Array is a single array comprised of over 4.6 million probes tiled through over 25,500 human promoter regions. Sequences used in the design of the Human Promoter array were selected from NCBI human genome assembly (Build 34). Repetitive elements were removed and promoter regions were selected using sequence information from: 35,685 ENSEMBL genes (version 21_34d, May 14, 2004), 25,172 RefSeq mRNAs (NCBI GenBank®, February 7, 2004), 47,062 complete-CDS mRNA (NCBI GenBank, December 15, 2003). Probes are tiled at an average resolution of 35 bp, as measured from the central position of adjacent 25-mer oligos, leaving a gap of approximately 10 bp between probes. Each promoter region covers approximately 7.5 kb upstream through 2.45 kb downstream of 5′ transcription start sites. For over 1,300 cancer-associated genes (1,143 unique genes, Supplemental Table 1), coverage of promoter regions have been expanded to include additional genomic content. This more extensive coverage spans from 10 kb upstream through 2.45 kb downstream of transcriptional start sites. The array interrogates regions proximal to transcription start sites and contains probes for approximately 59 percent of CpG islands annotated by UCSC in NCBI human genome assembly (Build 34).

Results

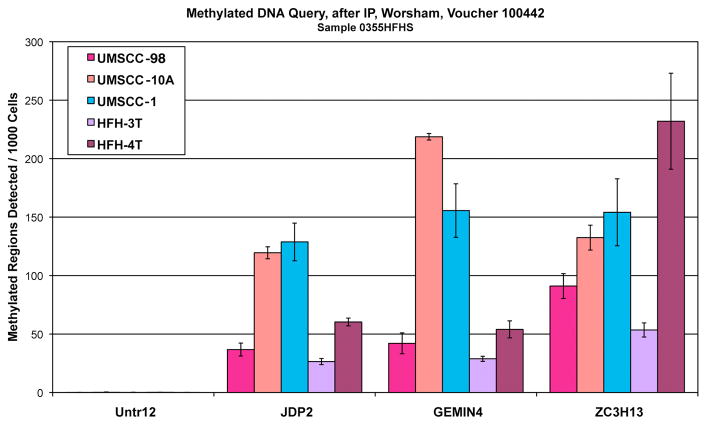

DNA enriched by the anti 5-methyl cytosine IPs (Fig 1)

Figure 1.

DNA enriched by the anti 5-methyl cytosine IPs.

Initially, quantitative PCR is performed on DNA enriched by the anti 5-methyl cytosine IPs. The primer labeled Untr12 serves as a negative control and amplifies an area of the genome that is not methylated. The other three primer sets, JDP2, FEMIN4, and ZCH13, amplify regions have been shown to be methylated in most samples. Figure 1 shows that the immunoprecipitations worked and that the samples were enriched for methylated DNA. The amount of methylation at the locations examined varies across the 5samples because the samples are derived from unrelated cell populations.

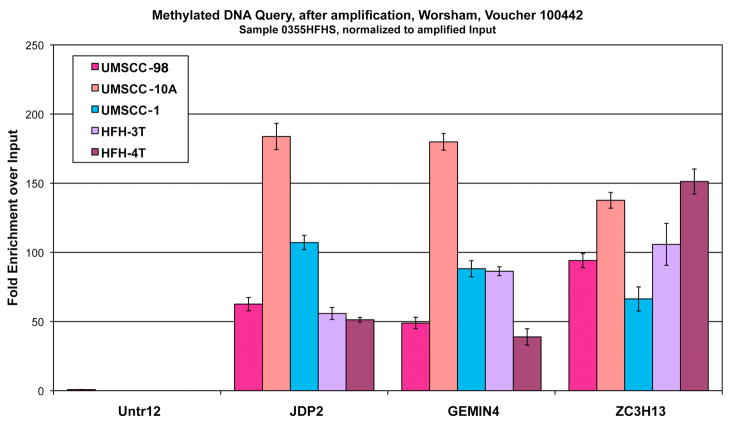

Amplification of immunoprecipitated DNA

The next step amplifies the immunoprecipitated samples to generate enough material to be labeled and hybridized to the arrays (Fig 2). Initial PCR results after amplification of the IP’ed DNAs indicates successful amplification for enrichment at the 3sites queried for labeling and array hybridization (Fig 2).

Figure 2.

Successful amplification for enrichment at the 3 sites queried for labeling and array hybridization.

DNA IP-on Chip Output Data: Summary of analysis steps

A. Affymetrix analysis

Image data from the array scans are analyzed using Affymetrix’ Tiling Analysis Software (TAS). This analysis generates BAR files (binary archive) that contain the intensities for all probes on the arrays. The intensities are expressed either as signals (estimating the fold enrichment) or as p-values (probabilities that measure the significance of the enrichment). More information on these algorithms can be found in the TAS User Guide: http://www.affymetrix.com/support/developer/downloads/TilingArrayTools/TileArray.pdf

B. Intervals (“Binding or association sites”)

Using the threshold selected (based on Affymetrix’ recommendations and known positive and negative genomic regions), Intervals with signals or p-values greater than the threshold are determined and compiled into BED files (Browser Extensible Data). Intervals represent the locations of intensity peaks.

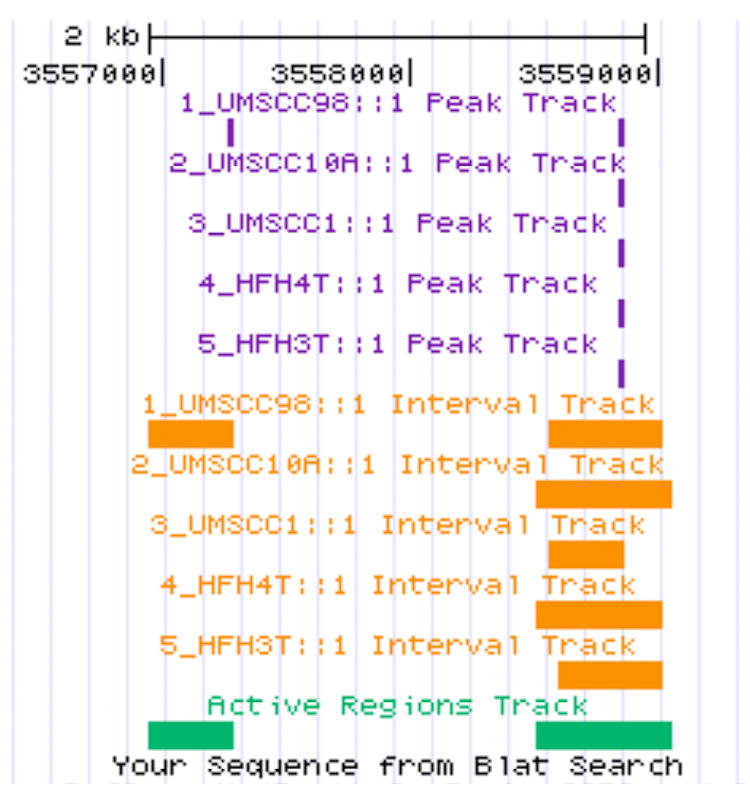

C. Active Regions

Active Regions are genomic regions that contain one or more Intervals in close proximity to each other. In Genpathway’s standard analysis, Intervals from different samples need to overlap by at least 1 bp to be added to the same Active Region. Active Regions are useful to consider because Intervals may not be exactly the same, e.g., in location or length, when comparing different samples, providing information of shared regions across samples (Fig 3).

Figure 3.

All five samples, HFHS4T, HFHS3T, UMSCC-98, UMSCC-10A, and UMSCC-1 share commonly methylated CpG islands in the promoter region of TP73 (orange color horizontal band).

D. Annotations

After the Intervals and Active Regions are defined, their exact locations along with their proximities to gene annotations and other genomic features are determined and presented in Excel spreadsheets.

Data Analysis

Of the 1,143 unique cancer genes on the array, 265 were recorded across our 5 samples (Supplemental Table 2). Of the 265, 55 were present in all 5 samples (illustrated for TP53, Fig 3), 36 were common to 4/5 samples, 46 to 3/5, 56 to 2/5, and 72 to 1/5 samples (Table 2). We also compared the methylated genes in our samples to that in PubMeth, a cancer methylation database combining text-mining and expert annotation (http://www.pubmeth.org)14. Of the 441 genes in PubMeth, only 33/441 are referenced to head and neck cancer. We matched 34 genes in our 5 samples to the PubMeth database (Table 3) 14. The whole-genome methylation approach resulted in 231 (265-34=231) new genes with hypermethylated promoter regions not previously reported in HNSCC (Supplemental Table 3). Of these, 47 were common to all 5 samples, 30 to 4/5 samples, 38 to 3/5 samples, 49 to 2/5, and 67 to 1/5 samples (Supplemental Table 3).

Table 2.

Distribution of Affymetrix Array genes across 5 Samples

| Sample Counts | Frequency | Cumulative Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 878 | 878 |

| 1 | 72 | 950 |

| 2 | 56 | 1006 |

| 3 | 46 | 1052 |

| 4 | 36 | 1088 |

| 5 | 55 | 1143 |

Table 3.

Genes in PubMeth and in samples

| Affy genes (265) in Pub Meth (441) | # of samples |

|---|---|

| ABL1 | 4 |

| BNIP3 | 5 |

| CCNA1* | 3 |

| CDH1* | 3 |

| CDKN1A | 4 |

| CDKN2A* | 3 |

| CHFR* | 2 |

| CTNNB1 | 5 |

| DAPK1* | 3 |

| DIABLO | 5 |

| ESR2 | 2 |

| FYN | 2 |

| GSK3B | 2 |

| HLTF | 2 |

| HRAS | 2 |

| HRASLS | 5 |

| HRK | 1 |

| IRS2 | 5 |

| LMNA | 1 |

| MGMT* | 1 |

| MSH2* | 4 |

| MTSS1 | 2 |

| NF2 | 3 |

| PLAU | 1 |

| RAB32 | 1 |

| RASGRF1 | 4 |

| RB1 | 3 |

| SFRP1 | 5 |

| SNAI1 | 5 |

| STK11 | 4 |

| TIMP2 | 3 |

| TP73* | 5 |

| WNT7A | 4 |

| WT1 | 3 |

present in PubMeth HNSCC data base

Discussion

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is a prevalent cancer with over 500,000 cases diagnosed annually. In the United States alone, it accounts for nearly 3.2% of all newly diagnosed cancers.15 Not only one of the most ubiquitous, HNSCC is also one of most lethal cancers responsible for 2.1% of all cancer deaths in the United States and is noted as the sixth most common malignant disease worldwide. Although the incidence of head and neck cancers has decreased slightly from 1975 to 2002 in the United States,16 approximately 35, 720 new cases of oral cavity and pharynx cancers are expected in 2009 with an estimated 7,600 deaths.15

A current shortcoming in the prognosis and treatment of HNSCC is a lack of methods and large study cohorts to adequately address the etiologic complexity and diversity of the disease. Historically, the molecular pathogenesis of cancer has been teased out one gene at a time. The development of several new high throughput analytical methods for the analysis of DNA, mRNA, and proteins within a cell has permitted a more detailed molecular characterization of the cancer genome.

Epigenetic events of promoter hypermethylation are emerging as one of the most promising molecular strategies for cancer detection and represent important tumor-specific markers occurring early in tumor progression. Numerous tumor suppressor genes have been implicated as targets for methylation in various cancers.7 Promotor hypermethylation of genes in HNSCC have been reported for p16, p14, DAP-K, RASSF1A,17 RARβ2,18 MGMT, a DNA repair gene that functions to remove mutagenic (O6-guanine) adducts from DNA,19 and E-cadherin, a Ca2+-dependent cell adhesion molecule that functions in cell-cell adhesion, cell polarity, and morphogenesis.20

For HNSCC, candidate-gene high-throughput methods support the contribution of both genetic8,9 and epigenetic events,11 often working together,12 in the development and progression of HNSCC. Promoter hypermethylation is emerging as one of the most promising molecular strategies for early detection of cancer, independent of its role in tumor development, and epigenomic biomarkers are quickly becoming far more practical than genomic biomarkers for several reasons.

Our group has shown that promoter hypermethylation is amenable to PCR-based methylation assays using whole genomic DNA from fresh/frozen tissue, cell lines, as well as formalin fixed paraffin tumor tissue DNA.12,18,21,22 The latter precludes some degree of normal tissue admixture and further underscores methylation signatures as positive signals unlike loss of heterozygosity, which requires a relatively pure amount of tumor DNA. Methylation of CpG islands may serve as a relatively simple “yes–no” signal for the presence of tumor when examined for under optimal assay conditions by sensitive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques.12,18,21,22 Additionally, aberrant promoter hypermethylation always occurs in virtually the same location within an affected gene, allowing a single PCR primer to be applicable to all patients for examination of the methylation status of a specific gene. This sharply contrasts with genomic biomarkers such as DNA mutations in genes such as TP53 or mitochondrial genes,23 which often involve myriad different base changes at many locations within the gene even in cancers of the same histologic types. Thus, classification based on promoter methylation profiling may well be a more promising approach than expression profiling since these DNA-based techniques are not subject to the problems of tissue preservation and the potential pitfalls of tissue heterogeneity. Aberrant DNA methylation represents a stable tumor-specific biomarker that occurs early in tumor progression and can be easily detected by PCR-based methods. The potential reversibility of DNA methylation patterns suggests that genes prone to promoter hypermethylation may be relevant as biomarkers in the development and evaluation of demethylating interventional strategies to block malignant progression and disease recurrence in HNSCC.

This pilot study examined the contribution of epigenetic events of global DNA hypermethylation to the pathogenesis of HNSCC in a hybrid sampling of 2 frozen primary HNSCC biopsies and 3 HNSCC cell lines. Questions are often raised about the value or relevance of cultured cell lines because selection pressures in vitro might cause the cell lines to become highly divergent from the original tumor. Concordance of genetic alterations between cells lines after prolonged passage in culture and their corresponding in vivo tumors support cell lines as accurate snapshots of the original tumor making them valuable resources for ongoing investigations.

To produce a global but unbiased inspection of aberrantly methylated promoter regions, high-throughput methylated DNA IP-on-Chip/Promoter assays (Affymetrix GeneChip® Human Promoter 1.0R Array) identified previously unreported genes for further confirmation, validation, and characterization in HNSCC.

Methods already in use to determine methylation status of individual cytosines or broader genomic regions have significant limitations. These include bisulfite conversion of cytosine to uracil followed by sequencing, methylation-specific PCR (MSP, which also requires bisulfite conversion), and enrichment or depletion of methylated sequences using methylation-specific restriction enzymes followed by analysis on microarrays. Bisulfite sequencing and MSP are not well suited for high-throughput analysis while restriction enzyme-mediated enrichment or depletion is not comprehensive due to the need for restriction sites at the thousands of regions to be analyzed. A limitation of the methylated DNA IP-on-Chip/Promoter assays is that this it requires whole genomic DNA and is not amenable to DNA from paraffin-embedded formalin fixed tissue.

Hypermethylated genes in the 5 sample cohort (265/1143) were cross-examined against those in PubMeth, a cancer methylation database combining text-mining and expert annotation (http://www.pubmeth.org). Of the 441 genes in PubMeth, only 33 of 441 are referenced to HNSCC. We matched 34 genes in our samples to the 441 genes in the PubMeth database, of which only 8 are reported in PubMeth as HNSCC associated. These 8 genes include TP73 (5/5 samples), MSH2 (4/5), CCNA1, CDH1, CDKN2A, and DAPK1 (3/3), CHFR (2/5), and MGMT (1/5).

Aberrant DNA methylation patterns in HNSCC have served as powerful diagnostic, prognostic, and risk assessment biomarkers. Promoter hypermethylation pattern of the p16, MGMT, GSTP1, and DAPK genes have been used as molecular markers for cancer cell detection in the paired serum DNA and almost half of the HNSCC patients with methylated tumors were found to display these epigenetic changes in the paired serum 24. Recently, using a multi-candidate gene assay,12 we identified nine genes, TIMP3, APC, KLK10, TP73, CDH13, IGSF4, FHIT, ESR1, and DAPK1 that were aberrantly methylated in paired HNSCC primary and recurrent or metastatic cell lines 12 The most frequently hypermethylated genes were APC and IGSF4 observed in 3/6 cell lines, and TP73 and DAPK1 observed in 2/6. Gene silencing through promoter hypermethylation was observed in 5/6 cell lines and contributed to primary and progressive events in HNSCC.12 Subsequently,18 we evaluated aberrant methylation status in 28 primary HNSCC, with CHFR as a solely late stage 4 event, occurring in 7/28 HNSCC,18 suggesting a role for CHFR in tumor progression with potential utility as a biomarker of late stage disease.

The biological significance of DNA methylation in the regulation of gene expression and its role in cancer is increasingly recognized. It is now clear that these epigenetic changes affect chromatin structure and thus regulate processes such as transcription, X-chromosome inactivation, allele-specific expression of imprinted genes, and inactivation of tumor suppresor genes (TSGs). Treatment with inhibitors of DNA methylation and histone deacetylation can reactivate epigenetically silenced genes and has been shown to restore normal gene function. In cancer cells, this results in expression of TSGs and other regulatory functions, inducing growth arrest and apoptosis. Azacitidine and decitabine are clinically active in myelodisplastic syndromes and other hematologic malignancies and may have therapeutic potential in other malignant disorders.

The whole-genome methylation approach indicated 231 potential new genes with hypermethylated promoter regions not previously reported in HNSCC and highlights the limitations of our previous candidate multi-gene approach.12,18,21,22 These studies, employing larger HNSCC study cohorts identified a mere handful of genes when compared to the global methylation strategy in this report. However, a limitation of this study remains the small number of patient samples and lack of control tissue. Examination of this comprehensive gene panel in a larger HNSCC cohort with inclusion of control samples (biopsies of normal SCC tissue) should advance selection of HNSCC-specific candidate genes for further validation as biomakers in HNSCC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Statistical support was provided by Dr. George Divine, department of Biostatistics and Research Epidemiology, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit. This study was supported by NIH R01 DE 15990.

Supported by NIH R01 DE 15990

Footnotes

Podium presentation at the 2009 AAO-HNSF Annual Meeting & OTO EXPO, San Diego, CA, October 4–7, 2009

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Costello JF, Plass C. Methylation matters. J Med Genet. 2001;38:285–303. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.5.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li E, Beard C, Jaenisch R. Role for DNA methylation in genomic imprinting. Nature. 1993;366:362–5. doi: 10.1038/366362a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfeifer GP, Tanguay RL, Steigerwald SD, et al. In vivo footprint and methylation analysis by PCR-aided genomic sequencing: comparison of active and inactive X chromosomal DNA at the CpG island and promoter of human PGK-1. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1277–87. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.8.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costello JF, Fruhwald MC, Smiraglia DJ, et al. Aberrant CpG-island methylation has non-random and tumour-type-specific patterns. Nat Genet. 2000;24:132–8. doi: 10.1038/72785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smiraglia DJ, Smith LT, Lang JC, et al. Differential targets of CpG island hypermethylation in primary and metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) J Med Genet. 2003;40:25–33. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones PA, Laird PW. Cancer epigenetics comes of age. Nat Genet. 1999;21:163–7. doi: 10.1038/5947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cairns P. Detection of promoter hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes in urine from kidney cancer patients. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1022:40–3. doi: 10.1196/annals.1318.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Worsham MJ, Pals G, Schouten JP, et al. Delineating genetic pathways of disease progression in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:702–8. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.7.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Worsham MJ, Chen KM, Tiwari N, et al. Fine-mapping loss of gene architecture at the CDKN2B (p15INK4b), CDKN2A (p14ARF, p16INK4a), and MTAP genes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:409–15. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.4.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanchez-Cespedes M, Okami K, Cairns P, et al. Molecular analysis of the candidate tumor suppressor gene ING1 in human head and neck tumors with 13q deletions. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2000;27:319–22. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2264(200003)27:3<319::aid-gcc13>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maruya S, Issa JP, Weber RS, et al. Differential methylation status of tumor-associated genes in head and neck squamous carcinoma: incidence and potential implications. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:3825–30. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Worsham MJ, Chen KM, Meduri V, et al. Epigenetic events of disease progression in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:668–77. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.6.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Worsham MJ, Wolman SR, Carey TE, et al. Chromosomal aberrations identified in culture of squamous carcinomas are confirmed by fluorescence in situ hybridisation. Mol Pathol. 1999;52:42–6. doi: 10.1136/mp.52.1.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ongenaert M, Van Neste L, De Meyer T, et al. PubMeth: a cancer methylation database combining text-mining and expert annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D842–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edwards BK, Brown ML, Wingo PA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2002, featuring population-based trends in cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1407–27. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esteller M, Corn PG, Baylin SB, et al. A gene hypermethylation profile of human cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3225–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen K, Sawhney R, Khan M, et al. Methylation of multiple genes as diagnostic and therapeutic markers in primary head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133:1131–8. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.11.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pegg AE. Mammalian O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase: regulation and importance in response to alkylating carcinogenic and therapeutic agents. Cancer Res. 1990;50:6119–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirohashi S. Inactivation of the E-cadherin-mediated cell adhesion system in human cancers. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:333–9. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65575-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stephen JK, Vaught LE, Chen KM, et al. Epigenetic events underlie the pathogenesis of sinonasal papillomas. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:1019–27. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stephen JK, Vaught LE, Chen KM, et al. An epigenetically derived monoclonal origin for recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133:684–92. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.7.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fliss MS, Usadel H, Caballero OL, et al. Facile detection of mitochondrial DNA mutations in tumors and bodily fluids. Science. 2000;287:2017–9. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanchez-Cespedes M, Esteller M, Wu L, et al. Gene promoter hypermethylation in tumors and serum of head and neck cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2000;60:892–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.