Abstract

Radioimmunotherapy (RIT) prolongs survival of mice infected with Cryptococcus neoformans (CN). To compare the efficacy of RIT and amphotericin B, we infected AJCr mice IV with either non-melanized or melanized CN cells. Infected mice were either left untreated, treated 24 hours post infection with 213Bi-18B7 antibody or amphotericin or both. Melanization before infection did not increase resistance of CN to RIT in vivo. 213Bi-18B7 treatment almost completely eliminated lung and brain CFUs while amphotericin did not decrease CFUs. We conclude that RIT is more effective than amphotericin against systemic infection with CN.

Keywords: radioimmunotherapy, C. neoformans, melanin, mouse models, systemic infection, Amphotericin B

Introduction

Cryptococcus neoformans (CN) infections cause life threatening meningoencephalitis in immunocompromised patients, causing more deaths than tuberculosis among AIDS patients in the developing world (1). Inability of immunocompromised individuals to mount an effective immune response to fungal infection reduces the efficacy of standard antifungal therapies, such as amphoterecin B or fluconazole (2). Melanization of CN occurs in the course of infections, is a virulence factor for this microbe, and reduces the effectiveness of antimicrobials including amphotericin B (3), adding to the need for novel effective treatments of CN in the setting of immunosuppression.

Radioimmunotherapy (RIT) relies on antibodies to deliver cytotoxic alpha- or beta radiation to tumor cells (4). Radiolabeled monoclonal antibodies (mAb) Zevalin® and Bexxar® are FDA approved for untreated, refractory and recurrent lymphomas. Several years ago we introduced RIT into the realm of infectious diseases, showing prolonged survival in mice systemically infected with CN and treated post-infection with radiolabeled mAb specific for CN polysaccharide capsule (5). This approach shows little acute hematological or long-term pulmonary toxicity (6), and work has begun to uncover the radiobiological and immune mechanisms of RIT of CN (7, 8). Here, as a step towards bringing RIT of fungal diseases into the clinic, we compare efficacy of RIT versus amphotericin against systemic experimental CN infection. We hypothesized that CN-specific antibody radiolabeled with alpha-particle emitting 213-Bismuth (213Bi) or the beta-particle emitting 188-Rhenium (188Re) would be able to kill both melanized and non-melanized CN cells in vivo better than standard antifungal therapy. We also investigated whether the combination of RIT and amphotericin treatment will produce different results from either therapy alone.

Methods

C. neoformans var. neoformans 24067 strain (ATCC, Manassas, VA), was grown on Sabouraud (SAB) agar. Non-melanized cells were cultured overnight in SAB broth; melanized cells were subcultured and grown for three days in minimal medium with 1 mM L-DOPA. Before infection, cells were washed in PBS and adjusted by hemocytometer to 107/mL. Plating efficiency was 55 and 70% for non-melanized and melanized cells, respectively.

Glucuronoxylomannan-binding murine mAb 18B7 (IgG1) was described in (5). Isotype-matching control mAb MOPC21 was from MP Biochemicals, Germany. 225Ac/213Bi generators were produced at the Institute for Transuranium Elements, Karlsruhe, Germany. Radiolabeling of mAbs with 213Bi and with 188Re eluted from 188Re/188W generator (Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, TN) was performed as described (5).

For in vitro RIT with 213Bi (physical half-life 46 min), 105 live melanized or non-melanized cells were incubated with radiolabeled mAbs (0.2 – 4.0 μg/mL) in the tubes with agitation for 0.5 hr at 37°C, collected by centrifugation, incubated in PBS at 37°C for 3 hr, treated with Tween 80 (0.5%), triturated 20 times, diluted and plated for CFUs. 188Re RIT method was the same except that cells were incubated for 48 hr at 4°C after the initial 37°C incubation, to allow 188Re, with a half-life of 17 hours, to deliver its radiation dose to the cells. For in vitro amphotericin experiments, 103 CN cells were incubated with 0 – 1.0 μg/mL amphotericin as deoxycholate (Bristol-Myers Squibb, New York, N.Y.) at 37°C for 2 hrs, aliquots plated and CFUs counted. Cellular dosimetry calculations were performed as in (9). The experiments were performed twice.

For animal experiments all procedures followed the Institute for Animal studies of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine guidelines. 3 × 105 melanized or non-melanized CN cells were injected into the tail vein of 6–8 week old female partially complement deficient AJCr (National Cancer Institute) mice. One day after infection mice infected with non-melanized or melanized CN were divided into groups of 5 and either were untreated; or given IP 100 μCi 213Bi-18B7; or treated at 24, 48, and 72 hours with amphotericin as deoxycholate at 1 μg/g body weight; or received both treatments. Mice were monitored for survival and their weights were measured every 3 days. At 60 days post infection, mice were sacrificed, their lungs and brains plated for CFUs and fixed for histopathology. Staining with H&E and GMS (Gomori-Grocott methenamine silver stain, ScyTek, Logan, Utah) was performed to detect inflammation and CN, respectively. Remaining lung and brain tissues were used to determine CFUs. The experiments were performed twice.

To find out the rate of sterilization of the organs of infected mice by amphotericin alone, mice were infected with melanized and non-melanized CN as above and treated with amphotericin at 1 μg/g body weight for 14 days. At 7 and 14 days post-treatment 4 mice from each group were sacrificed and their lungs and brains plated for CFUs. This experiment was performed once. Differences in CFUs and body weights were analyzed by Student’s t-test for unpaired data. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

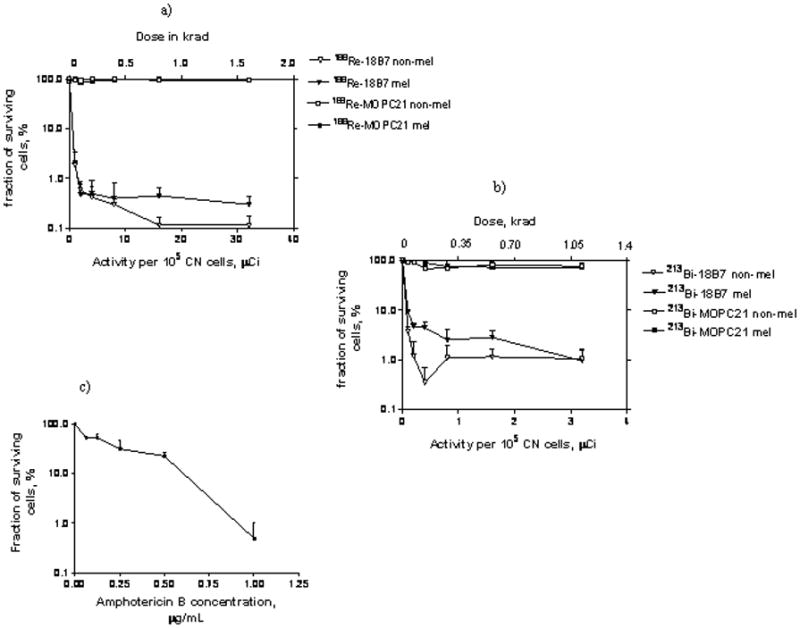

Melanized and non-melanized 24067 CN cells were incubated with increasing activities of 188Re-and 213Bi-18B7 mAb. Incubation of melanized and non-melanized cells with 1.5 μCi 188Re- or 0.2μCi 213Bi-18B7 mAb killed 90% of the cells and delivered cellular radiation doses of 0.1 krad for 188Re-18B7 and 0.04 krad for 213Bi-18B7 (Fig. 1a,b). 213Bi or 188Re conjugated to the irrelevant isotype-matching antibody MOPC killed neither type of cell (Fig. 1a, b). The difference in susceptibility of melanized and non-melanized cells to antibody-delivered radiation became obvious when we attempted to achieve 99.9% elimination of cells. Sixteen μCi (0.8 krad dose) of 188Re-18B7 mAb eliminated 99.9% of non-melanized cells while that degree of cell killing was not achieved for melanized cells in the investigated range of activity. 213Bi-18B7 mAb killed 99.7% of non-melanized cells with 0.4 μCi (0.17 krad dose) but again that level of cell killing was not observed for melanized cells. As approximately 10 times less 213Bi than 188Re radioactivity was required to eliminate the bulk of either melanized or non-melanized cells - we selected 213Bi-mAbs for in vivo comparison with amphotericin. One μg/ml amphotericin reduced CN CFUs by more than two log units (Fig. 1c). Considering published MIC for melanized 24067 CN being higher than for non-melanized (0.1875 and 0.1250 μg/mL, respectively) - we selected a dose of 1 μg/gram of mouse body weight (~17 μg/mouse), allowing a transient blood concentration of 8.5 μg/mL, for in vivo experiments.

Fig. 1.

In vitro killing and dosimetry of melanized and non-melanized CN cells treated with: a) 188Re-labeled CN polysaccharide-specific 18B7 and control isotype-matching MOPC21 mAbs; b) 213Bi-labeled CN polysaccharide-specific 18B7 and control isotype-matching MOPC21 mAbs. mel – melanized CN cells; non-mel – non-melanized CN cells; c) amphotericin B.

Changes in average weights of the different treatment groups of AJCr mice infected with non-melanized or melanized CN are shown in Fig. 2a,b. RIT-treated non-melanized CN group experienced some weight loss between days 0 and 20 and then gained weight for the rest of the observation period. RIT-treated melanized CN group gained weight faster than non-melanized CN group (p=0.04). Amphoterecin-treated non-melanized CN group lost some weight around day 30 but then recovered (Fig. 2a) while amphotericin-treated melanized CN group gained weight during the whole observation period (Fig. 2b). However, the difference in weights between amphotericin-treated and RIT mice in melanized CN group was significant (p<0.05) only till Day 20 when RIT mice were still recovering from RIT-associated weight loss and after Day 20 the difference was not statistically significant (p>0.05). The combined treatment group did best in terms of gaining weight among mice infected with non-melanized CN, while in melanized CN group combination treatment resulted in mice gaining more weight than RIT group and then equalized with RIT group later in the study.

Fig. 2.

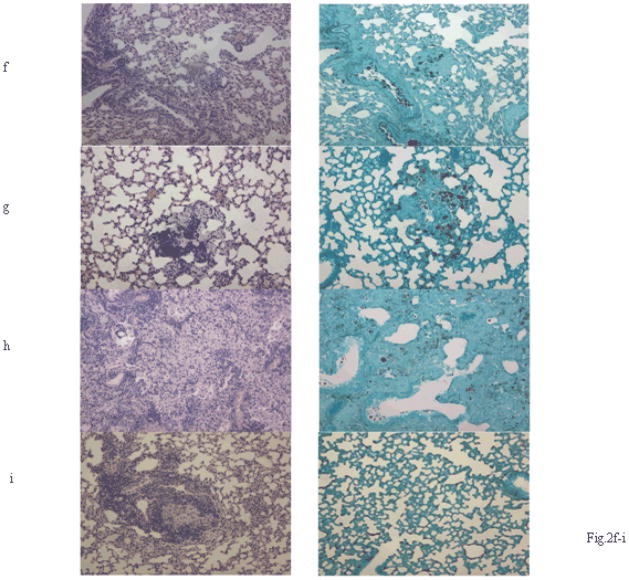

RIT of mice infected with non-melanized or melanized CN. AJ/Cr mice were infected IV with 3 × 105 CN cells and 24 hr later either given 100 μCi 213Bi-18B7 RIT or amphotericin B at 1 μg/g body weight on Days 1, 2 and 3 post-infection or combined treatment or left untreated. (a, b) body weights of mice infected with: a) non-melanized CN; b) melanized CN; (c, d) CFUs in the lungs and brains of treated and control mice: c) non-melanized CN; d) melanized CN. Detection limit of the method was 50 CFUs. No CFUs were found in the brains and lungs of mice infected with melanized CN cells and treated with RIT which are presented in the graph as 40 CFUs/organ; e) CFUs in the brain and lungs of mice infected with 3 × 105 melanized (M) or non-melanized (NM) CN cells and treated with amphotericin B at 1 μg/g body weight for 14 days. Mice were sacrificed at days 7 and 14 post-treatment (f–i) histology of consecutive slides of the lungs of the treated and control mice sacrificed on Day 60 post-infection: f) untreated mice; g) RIT; h) amphotericin B alone; i) combination of RIT and amphotericin B. Left panels are H&E staining; right panels – GMS staining. CN cells appear black on GMS-stained slides. Original magnification 200.

Analysis of lungs and brains at 60 days post infection showed that amphoterecin did not significantly decrease CFUs in the lungs and the brains in either non-melanized (Fig. 2c) or melanized CN groups (Fig. 2d) (p>0.05). RIT had significantly decreased fungal burdens compared to untreated or amphotericin-treated mice (p≪0.05). In fact, RIT-treated non-melanized CN group almost completely cleared fungus from the brain (the lower limit of detection was 50 CFUs) while RIT-treated melanized CN group almost completely cleared the infection from both brain and lungs. The combined treatment was more efficient than amphotericin alone for both brain and lungs (p<0.05) and more efficient than RIT alone in eliminating CN from the lungs (p<0.05) in non-melanized CN group (Fig. 2c). In melanized CN group combined treatment was better than amphotericin alone for both brains and lungs (p<0.05) but worse than RIT alone (p<0.05) (Fig. 2d).

Prolonged treatment of mice with amphotericin alone for 14 days showed no improvement in either brains or lungs CFUs on day 7 post-treatment in both non-melanized and melanized CN groups (p>0.05); on Day 14 there was a trend towards one log reduction in CFUs in brain and lungs in both non-melanized and melanized groups (p=0.06) (Fig. 2e).

Histopathology of lung and brain tissue demonstrated the focal nature of infection in all groups. Neutrophils and foamy macrophages infiltrated the lungs of mice from untreated and amphotericin groups (Fig. 2f, h). Interestingly, several mice from RIT (Fig. 2g) or combined treatment groups (Fig. 2i) had some CN cells in their organs visualized by GMS staining but did not have CFUs in either brain or the lungs, indicating that fungal cells identified by GMS staining may have lost their ability to replicate.

Discussion

We compared the efficacy of RIT of infection with melanized or non-melanized CN to that of the standard anti-fungal agent amphotericin as deoxycholate as well as their combination. Melanin is a known virulence factor for CN (3) and melanization protects CN from external gamma radiation (reviewed in 10). We observed that melanization of CN before infection did not increase resistance of CN to RIT in vivo. Possible explanations for this may include the delicate balance existing in vivo between daughter cells which are not melanized right after budding (11) and their acquisition of melanin once they establish themselves in organs containing melanin precursors; as the well as the contribution of host immune defenses towards RIT efficacy (7) which is obviously absent in vitro. It has been demonstrated that mice mount an intense Ab response to fungal melanin that includes Abs of IgM and IgG isotypes which points to the stimulation of the immune system by melanin (12). Given that antibodies to melanin can have a direct antifungal activity on cryptococcal cells it is possible that such stimulation of immune system contributes to efficacy of RIT against melanized cells.

Our most important observation is that RIT was more effective in reducing fungal burden in lungs and brains than amphotericin at a high dose of 1 μg/g, with most RIT-treated mice almost completely clearing the infection. The inability of amphotericin to reduce the fungal burden in the organs of partially complement deficient AJCr mice after 3 days of treatment was explained by the follow-up study with a trend towards reduction of CFUs in brains and lungs manifesting itself only on the 14th day of treatment. These observations are in concert with literature showing that even in intact robust mice as CD-1 or Balb/c amphotericin as deoxycholate was also only able to produce 1–1.5 log reduction in CFUs and all mice died around day 24 (13, 14). It is also in concert with the data from clinical studies showing that a short course of amphotericin does not sterilize cerebrospinal fluid or blood and that the rate of sterilization correlates with survival (15). Our observation underlines the advantages of RIT which produces microbicidal effects in vivo just after one injection when compared to prolonged treatment with amphotericin. When combined RIT and amphotericin treatment was used – a complex picture emerged depending on the melanization status of infection. Combination treatment was more effective than amphotericin alone for both non-melanized and melanized CN groups. In melanized CN group the combination treatment was less effective than RIT which could be due to inflammation and renal toxicities associated with amphotericin at this dose in mice. Interestingly, for non-melanized CN the combination treatment did produce some synergy in reducing CFUs in the lungs. It is possible to suggest that if RIT is administered much later during the course of treatment with amphotericin – some synergistic effects could be observed.

It is noteworthy that remaining fungal cells retain sensitivity to radiation and would be amenable to further RIT treatments (8). In conclusion, RIT with alpha-emitter-armed antibodies is more effective than amphotericin against experimental systemic infections with both melanized and non-melanized CN, presenting an attractive option for development of clinical treatment.

Acknowledgments

Sources of financial support: E. Dadachova is a Sylvia and Robert S. Olnick Faculty Scholar in Cancer Research and is supported by the NIH grant AI60507 and Fighting Children’s Cancers Foundation. A. Casadevall is supported by the following NIH grants: AI33774-11, HL59842-07, AI33142-11, AI52733-02, and GM 07142-01. A. Morgenstern and F. Bruchertseifer are supported by European Commission;

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors either have or do not have a commercial or other association that might pose a conflict of interest;

Part of the results was presented at the 109th ASM General Meeting, May 2009, Philadelphia, PA;

References

- 1.Park BJ, Wannemuehler KA, Marston BJ, Govender N, Pappas PG, Chiller TM. Estimation of the current global burden of cryptococcal meningitis among persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS. 2009;23:525–530. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328322ffac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ben-Ami R, Lewis RE, Kontoyiannis DP. Immunopharmacology of modern antifungals. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:226–235. doi: 10.1086/589290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nosanchuk JD, Casadevall A. The contribution of melanin to microbial pathogenesis. Cell Microbiol. 2003;5:203–223. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5814.2003.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharkey RM, Goldenberg DM. Perspectives on cancer therapy with radiolabeled monoclonal antibodies. J Nucl Med. 2005;46(Suppl 1):115S–127S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dadachova E, Nakouzi A, Bryan RA, Casadevall A. Ionizing radiation delivered by specific antibody is therapeutic against a fungal infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10942–10947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1731272100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dadachova E, Bryan RA, Frenkel A, et al. Evaluation of acute hematological and long-term pulmonary toxicity of radioimmunotherapy of Cryptococcus neoformans infection in murine models. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1004–1006. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.3.1004-1006.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dadachova E, Bryan RA, Apostolidis C, et al. Interaction of radiolabeled antibodies with fungal cells and components of the immune system in vitro and during radioimmunotherapy for experimental fungal infection. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:1427–1436. doi: 10.1086/503369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryan RA, Jiang Z, Huang X, et al. Radioimmunotherapy is effective against a high infection burden of Cryptococcus neoformans in mice and does not select for radiation-resistant phenotypes in cryptococcal cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:1679–1682. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01334-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dadachova E, Howell RW, Bryan RA, Frenkel A, Nosanchuk JD, Casadevall A. Susceptibility of human pathogens Cryptococcus neoformans and Histoplasma capsulatum to gamma radiation versus radioimmunotherapy with alpha- and beta-emitting radioisotopes. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:313–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dadachova E, Casadevall A. Ionizing radiation: how fungi cope, adapt and exploit with the help of melanin. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11:525–531. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nosanchuk JD, Casadevall A. Budding of melanized Cryptococcus neoformans in the presence or absence of L-dopa. Microbiology. 2003;149:1945–1951. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26333-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nosanchuk JD, Rosas AL, Casadevall A. The antibody response to fungal melanin in mice. J Immunol. 1998;160:6026–6031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clemons KV, Stevens DA. Comparison of fungizone, Amphotec, AmBisome, and Abelcet for treatment of systemic murine cryptococcosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:899–902. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.4.899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kakeya H, Miyazaki Y, Senda H, et al. Efficacy of SPK-843, a novel polyene antifungal, in a murine model of systemic cryptococcosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:1871–1872. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01370-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bicanic T, Muzoora C, Brouwer AE, et al. Independent association between rate of clearance of infection and clinical outcome of HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: analysis of a combined cohort of 262 patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:702–709. doi: 10.1086/604716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]