Abstract

The present study examined the contribution of myofilament contractile proteins to regional function in guinea pig myocardium. We investigated the effect of stretch on myofilament contractile proteins, Ca2+ sensitivity, and cross-bridge cycling kinetics (Ktr) of force in single skinned cardiomyocytes isolated from the sub-endocardial (ENDO) or sub-epicardial (EPI) layer. As observed in other species, ENDO cells were stiffer, and Ca2+ sensitivity of force at long sarcomere length was higher compared with EPI cells. Maximal Ktr was unchanged by stretch, but was higher in EPI cells possibly due to a higher α-MHC content. Submaximal Ca2+-activated Ktr increased only in ENDO cells with stretch. Stretch of skinned ENDO muscle strips induced increased phosphorylation in both myosin-binding protein C and myosin light chain 2. We concluded that transmural MHC isoform expression and differential regulatory protein phosphorylation by stretch contributes to regional differences in stretch modulation of activation in guinea pig left ventricle.

Keywords: Frank-Starling, Myocyte, Contractility, Kinetics, Heart, Signaling, Sarcomere length

Introduction

The contractile strength of the heart is modulated, on a beat to beat basis, by both the amount of Ca2+ released from the sarcoplasmic reticulum and the responsiveness of the myofilaments to Ca2+. Apart from the hormonal regulation of both these processes, myofilament Ca2+ responsiveness is also modulated by sarcomere length (SL), and this forms the cellular basis of the Frank–Starling law of the heart. The molecular mechanisms that underlie myofilament length-dependent-activation (LDA), however, are incompletely understood.

Cell lengthening within the physiological working range significantly increases the Ca2+ sensitivity of force [1, 25]. Part of this effect may be due to reduced interfilament lattice spacing with stretch, which may increase the probability of myosin binding to actin to yield more force-generating cross-bridges that activate the thin filament [31, 39]. A recent study has shown that interfilament spacing alone cannot explain changes in Ca2+ sensitivity [17]. It now seems more likely that Ca2+ sensitivity is determined by changes in the structure of myosin filaments [17, 36].

Phosphorylation of myofilament proteins has been suggested to affect cardiac contractility independently of the alterations in the dynamics of Ca2+ handling [29]. In skinned myocardium, protein kinase A (PKA)-induced phosphorylation of cardiac troponin I (cTnI) and cardiac-myosin-binding protein C (cMyBP-C) is associated with decreased Ca2+ sensitivity of force, increased rates of cross-bridge cycling, and increased LDA. The underlying mechanism include altered thin and thick filament properties, respectively (reviewed in [30, 32]). Despite its physiological importance, the impact of stretch on the phosphorylation status of regulatory proteins in correlation with contractile parameters remains to be investigated.

We previously showed that passive and active mechanical properties are not uniform across the left ventricular free wall. Intact and skinned cardiac myocytes isolated from sub-endocardial (ENDO) layers in several species are significantly stiffer than sub-epicardial (EPI) myocytes [7–9]. Moreover, in the physiological sarcomere length range, auxotonic contraction of the stiffer intact ENDO myocytes is higher than EPI at similar diastolic SL in the absence of significant changes in the intracellular calcium transient [7, 8]. The higher-length sensitivity of contraction in intact ENDO cells is due to a higher LDA of the myofilaments when compared with EPI cells [9]. This higher LDA has been correlated with a stretch-induced phosphorylation of the myosin light chain-2 (MLC-2) in ENDO cells [9].

Small rodents such as mice and rats express in the heart almost exclusively the α-myosin isoform, unlike larger mammals such as the human, which expresses >90% β-myosin. Whether regional differences in myofilament length-dependent-activation also occur in hearts composed of predominantly β-MHC is not known. Accordingly, the purpose of this study was to examine regional myofilament length dependence of contraction in guinea pig myocardium expressing ~80% β-MHC. In addition, we examined the effect of stretch on sarcomeric proteins (titin, cTnI, cMyBP-C, and MLC-2) that are potentially involved in LDA. Here, two contractile parameters, myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity and cross-bridge cycling kinetics were studied in guinea pig skinned cardiomyocytes. Myocytes were obtained from either the sub-endocardial or the sub-epicardial layer so as to study within the same heart, myocytes with a high (ENDO) and low (EPI) LDA. Our results show a positive correlation between the stretch-induced passive tension and myofilament contractile properties. Furthermore, we found that a high level of passive tension development was associated with increased phosphorylation of MLC-2 and MyBP-C. As these proteins are known to affect myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity of force and the kinetics of force redevelopment, our data suggest that stretch-induced phosphorylation of myofibrillar proteins in living myocardium may contribute to the Frank–Starling relationship.

Materials and methods

All experiments were performed according to institutional guidelines concerning the care and use of experimental animals and the NIH guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Isolated myocytes

Single ventricular myocytes were enzymatically isolated as previously described [8]. Briefly, guinea pigs (250–300 g) were killed by cervical dislocation. Hearts were quickly removed and fixed on a Langendorff apparatus. The heart was perfused for a few minutes with a Ca2+-free physiological saline solution and perfused for 7–10 min with a solution containing 0.6 mg ml−1 collagenase (Boehringer type B) and 0.14 mg ml−1 protease (Sigma type XIV). Next, the ventricles were separated from the atria and opened. Small pieces of ventricular muscle were dissected from the inner free wall (ENDO) and outer free wall (EPI), and cells were isolated by gentle suction. External Ca2+ was progressively raised to 1 mM. Single myocytes were skinned for 6 min at 21°C in relaxing solution (pCa 9) containing 0.3% v/v Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors (see below). Skinned myocytes were maintained at 4°C and used within 1 day.

Skinned myocyte sarcomere length and force measurements

The Ca2+-activated force of single skinned myocyte was measured as described previously [9]. Skinned myocytes were attached to a strain gauge and a stepper motor driven micromanipulator with thin needles and UV-polymerized optical glue (NOA63, Norland products, North Brunswick, NJ, USA). Myocyte SL was recorded at 60 Hz and analyzed in real time using IonOptix equipment and software (IonOptix, Milton, MA, USA). Force was normalized to cross-sectional area measured from the imaged cross-section as described previously [6]. Slack SL was measured before attachment and did not differ significantly between myocytes from EPI (1.85±0.01 μm) and ENDO (1.85±0.01 μm). The pCa (=−log[Ca2+])–force relationships were established at two SL: 1.9 and then at 2.3 μm, at 22°C (Fig. 1). Cells that did not maintain 80% of the first maximal tension, a visible striation pattern, or excessive SL shortening during activation (>0.1 μm) were discarded. When required, cell length was varied during the contraction to maintain SL. Active tension at submaximal activations was normalized to maximal isometric tension at the same SL. Maximal active tension decreased slightly with the number of imposed contractions; the mean reduction was 7±3% (n=14) and 7±5% (n=14) for ENDO and EPI myocytes, respectively. For each cell, the relation between force and pCa was fit to the following equation:

where nH is the Hill coefficient and pCa50 the pCa for half-maximal activation, equals −(log K)/nH. The ΔpCa50 was calculated as the difference in pCa50 at 1.9 and 2.3 μm SL for each experiment.

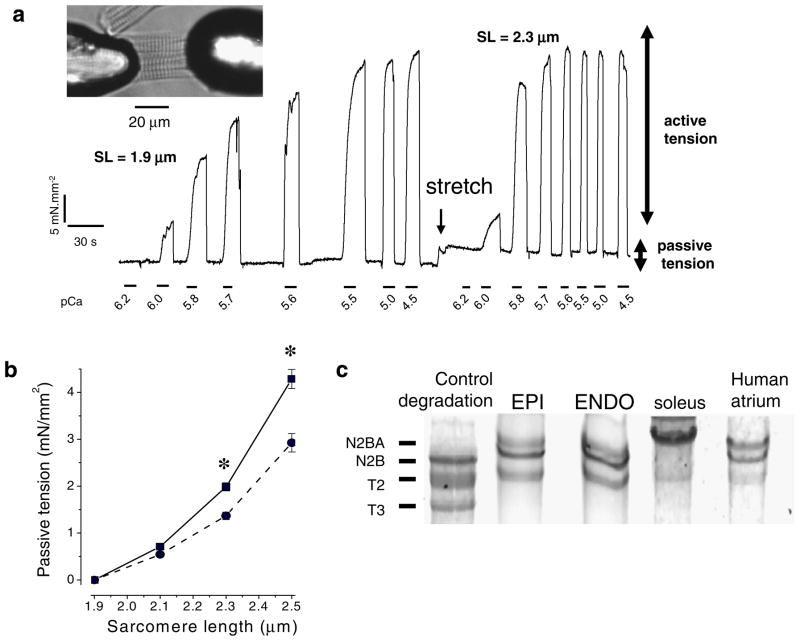

Fig. 1.

Passive and active properties of permeabilized guinea pig ventricular myocyte isolated in sub-epicardium (EPI) and sub-endocardium (ENDO). a Original recording of force during myocyte activation. b Passive properties of the cells were determined by sequentially stretching the cell to various SL in relaxing solution. EPI cells (filled circles) are significantly more compliant than ENDO cells (filled squares; n=14 cells per region). c Titin isoform content was investigated on a gradient SDS gel (2.7–7%); rat cardiac tissue incubated with trypsin was used as a control of titin degradation, rat soleus for the N2A isoform and human atrium for the N2BA and N2B titin isoforms; guinea pig cardiac tissue expressed both N2B and N2BA isoforms (n=5 animals, in duplicate). *P<0.05

Rate of tension redevelopment

Release–restretch experiments were performed according to a procedure modified from [4] and similar to [48]. Briefly, attached cross-bridges were mechanically disrupted by applying a release within 1 ms to 20% of original active length using a piezoelectric translator (P-244.27, Physik Instruments). Tension declined to zero and was maintained over a brief period (20 ms) of unloaded shortening followed by rapid restretch to the starting muscle length. Tension redevelopment was characterized by an apparent mono-exponential rise in force with a rate constant Ktr. For each pCa, the protocol was applied three times, and Ktr was determined by monoexponential fit to the average signal (Fig. 3a) using commercial software (Axon Instruments).

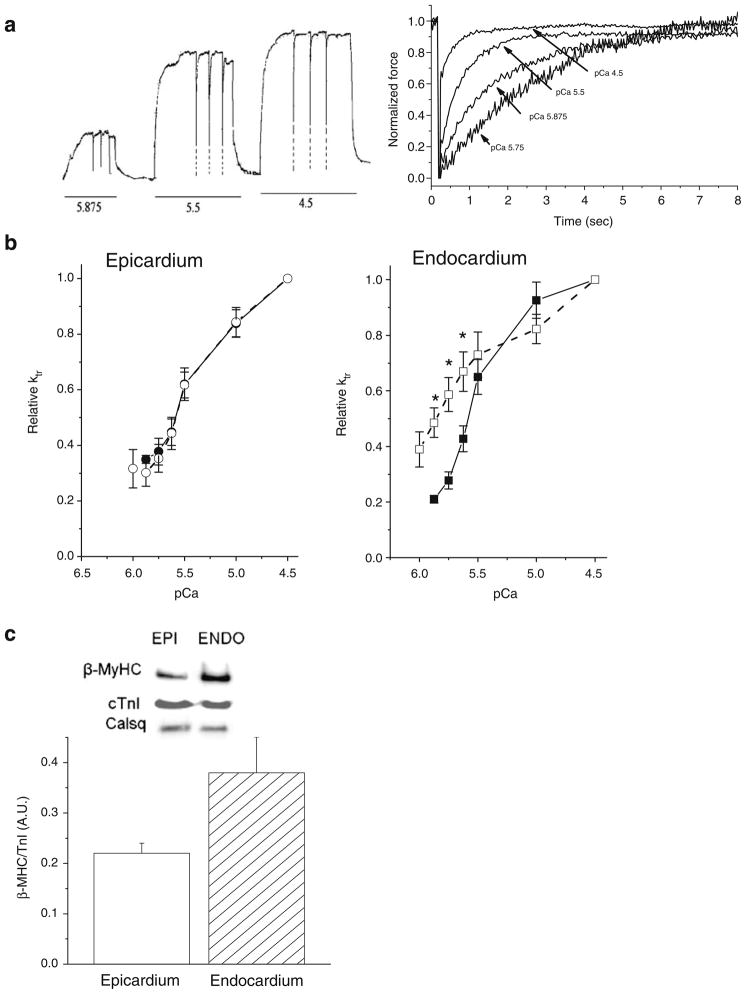

Fig. 3.

Release/restretch experiments on a single skinned cardiac myocyte. a Original tracing of the tension showing the application of three successive large (20%) release/restretch maneuvers of cell length elicited at three pCas (5.875, 5.5, and 4.5). Tension reached zero level after this procedure; however, the frequency response of the chart recorder was not sufficient to allow this to be recorded before the cell was rapidly restretched; for clarity the fast initial tension releases have been retouched (dotted lines). Right: averaged records of tension for determination of Ktr at four calcium concentrations. For each Ca2+ concentration, force before applying the slack release–restretch maneuver was used for normalization to emphasize the changes in the rate of tension redevelopment with Ca2+. b Relationship between relative Ktr and pCa in EPI (n=8 cells, circle) and ENDO (n=8 cells, square) cells at SL=1.9 μm (closed symbols, line) and SL=2.3 μm (open symbols, dashed line). c Left: β-Myosin heavy chain expression in cardiomyocytes isolated from sub-epicardium (open bar) or sub-endocardium (grey bar) as determined by Western Blot was expressed relative to the total TnI content in each group (n=5 hearts per group analyzed in triplicate). Calsequestrin (Cals) was used as an additional internal control of loading. *P<0.05

Solutions

Solutions were similar to those used previously [9]. For cell dissociation, the Ca2+-free Hanks–4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES)-buffered solution contained (in mM): NaCl 117, KCl 5.7, NaHCO3 4.4, KH2PO4 1.5, MgCl2 1.7, HEPES 21, glucose 11.7, taurine 20, 2,3-butanedione monoxime 15, pH 7.15 adjusted with NaOH, and was bubbled with 100% O2.

For myocyte force measurements, activating solutions were prepared daily by mixing relaxing and maximal activating solutions containing (in mM): Na-acetate 10, phosphocreatine 12, imidazole 30, free Mg2+ 1, ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid 10, Na2ATP 3.3 and dithiothreitol 0.3 with either pCa=9.0 (relaxing solution) or pCa=4.5 (maximal activating solution), protease inhibitors (PMSF 0.5; leupeptin 0.04 and E64 [trans-epoxysuccinyl-1-leucine-guanidobutylamide] 0.01), pH 7.1 adjusted with acetic acid. Ionic strength was adjusted to 180 mM with K-acetate.

Biochemical analysis

Titin content and isoform distribution in EPI and ENDO tissues were analyzed on 2.5–7% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) according to [6] with slight modifications. Cells were pulverized in liquid nitrogen and solubilized for 3 min at 60°C in a Laemmli buffer supplemented with 8 M urea and 2 M Thiourea. After electrophoretic separation, gels were stained with 0.1% Coomasie Blue G250, imaged (Kodak Image Station 2000R) and analyzed using Kodak 1D image analysis software. The integrated optical density of myosin heavy chain (MyHC) and titin (N2B and N2BA isoforms) were determined to calculate the total amount of titin relative to MyHC and titin isoform expression ratio (N2B to N2BA ratio). The titin/MyHC ratio and N2BA/N2B ratio were obtained from the slopes of a range of loading determined for each band.

β-MyHC, cTnI, MLC2, and cMyBP-C analyses were performed on freshly dissected skinned strips as previously described [9]. Briefly, heart was perfused for 10 min with a pCa9 solution containing 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors. Muscle strips from the inner and outer layers of the left ventricle were dissected in this solution under a microscope to follow the fiber orientation, and strips were kept in the skinning solution at room temperature for an additional 10 min and washed in relaxing solution. Strips were quickly frozen at slack length or after stretching by ~20–30% of initial slack length to 2.30±0.05 μm SL. The tissue was homogenized in ice cold trichloroacetic acid (TCA; 10%) so as to maintain contractile protein phosphorylation statues. Samples were then washed three times in acetone/10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). The pellet was mixed with urea buffer (in M: urea 8, DTT 0.5, Tris 0.22, Glycine 0.25, saturated glucose, EDTA 0.4, PMSF 5×10−4, NaF 0.35). Protein concentration was determined with RCDC kit (Bio-Rad). Proteins (20 μg) were separated either on 10% urea gel for MLC2 isoforms or on 2–20% SDS-PAGE for the other proteins. For analysis of phosphorylation levels, all samples from one animal were always loaded in duplicate on the same gel. The first lanes were used to measure the phosphorylated proteins and were normalized with the last lanes used to determine the total protein content. After transfer onto nitrocellulose membrane (1 h, 0.08 A), immunoblotting analysis was performed with corresponding primary antibodies: cardiac MLC-2 antibody (Coger SA Paris, 1:200 dilution), β-MyHC (Sigma, 1:2.500 dilution), cTnI (clone 6F9, 1:2.000 dilution), and the PKA phosphorylated form of cTnI (clone 5E6, 1:200 dilution) from Hytest (Finland); cMyBP-C (1:1.000 dilution), and the phosphorylated Ser282-cMyBP-C (1:1.000 dilution), generous gifts from Drs. Christian Witt and Lucie Carrier, respectively. Visualization was achieved with the ECL system (Amersham). Quantification of signals was performed by densitometry. Results are expressed relative to the total amount of the studied protein.

Statistical analysis

One-way or two-way analysis of variance was applied for comparison between groups. When significant interactions were found, a Holm–Sidak t test was applied with P<0.05 (Sigmastat 3.5). Data are presented as mean± SEM.

Results

Passive properties of sub-epicardial and sub-endocardial myocytes

Passive tension was measured by gradually stretching each cell in relaxing solution (pCa 9) from slack length (measured before attachment) to 1.9, 2.1, 2.3, and 2.5 μm SL before the determination of the tension-pCa curves. Measurements were made at steady state when the rapid phase of stress relaxation was completed. ENDO cells developed significantly higher passive tension when stretched above 2.3 μm SL than EPI cells (Fig. 1b; 4.3± 0.2 vs. 2.9±0.2 mN/mm at SL=2.5 μm). As shown previously in rat myocytes [9], the difference of passive tension between EPI and ENDO cells was not due to residual cross-bridges in the relaxed state because passive tension was unaffected when cells were incubated with 2,3-butanedione monoxime, an agent that removes weak binding cross-bridges (data not shown). Over the physiological operating range of SL, titin is the principal cytoskeletal protein responsible for cellular passive properties [20]. The myocardium co-expresses two titin isoforms, the short N2B and the long N2BA isoform. As described previously, guinea pig myocardium expresses mostly the short N2B titin isoform [34]. To establish whether a regional variation in titin was responsible for the difference in stiffness between ENDO and EPI cells, we measured titin content and isoform distribution in both cell types. A typical example is shown in Fig. 1c. The migration of titin revealed a major T1 band corresponding to full-length titin and a lower band, T2, which results from degradation [20]. No change in titin isoform composition was observed across the wall of the guinea pig ventricle (ENDO, 63±2.7; EPI, 58.4±5.2; %N2B/total titin). Furthermore, the total amount of titin present in the sarcomere was not different between ENDO and EPI cells (ENDO, 0.78±0.16; EPI 0.79±0.05; titin/myosin). Hence, the difference in cellular passive tension between the endocardial and epicardial layers of the heart appeared not to be due to a difference in the intrinsic stiffness of titin.

Sensitivity to SL stretch of sub-epicardial and sub-endocardial myocytes

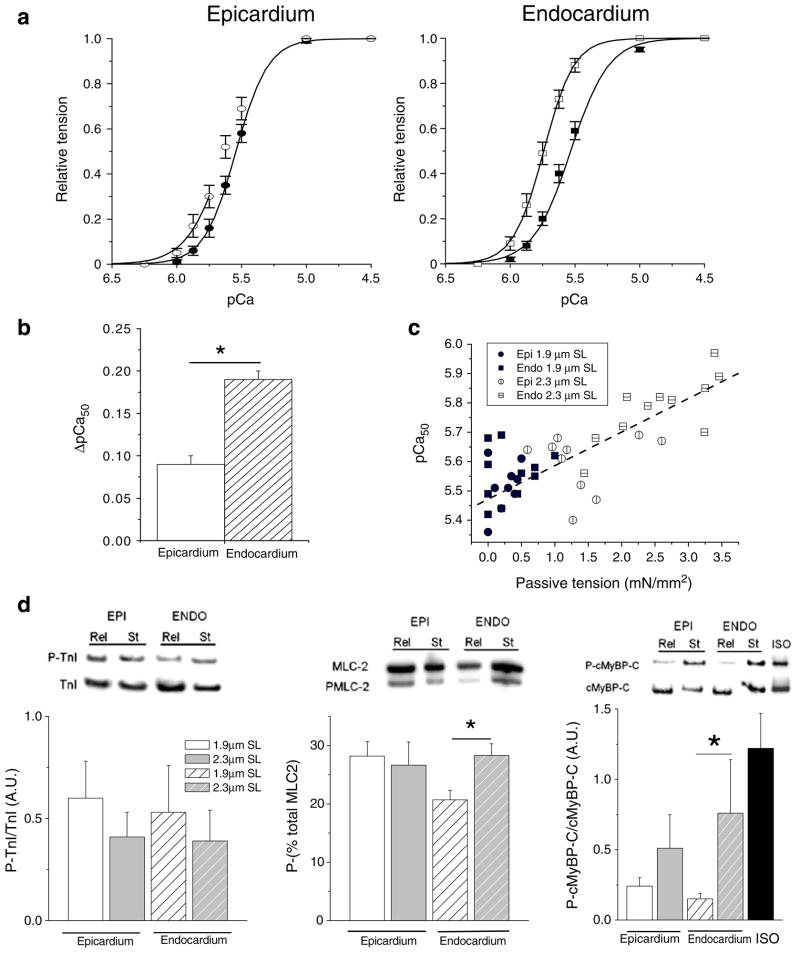

Skinned cells were maintained in isometric conditions throughout the experiments at either SL=1.9 or 2.3 μm measured by video microscopy. An active force–[Ca2+] relationship was determined at each SL by sequentially perfusing the cell with solutions containing various Ca2+ concentrations. Figure 1 further illustrates the increase in resting force upon stretch to SL=2.3 μm and the concomitant increase in myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity. That is, at equivalent intermediate [Ca2+], more force is developed at the high SL compared to the low SL. The average relationships between active tension development and [Ca2+] at SL=1.9 and 2.3 μm are shown in Fig. 2. The data were fit to a modified Hill equation, and the average parameters are summarized in Table 1. As previously observed in rat heart in similar conditions [9], the myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity was similar between EPI and ENDO cells at short SL. Stretching the cells from 1.9 to 2.3 μm SL induced a significant leftward shift of the force–Ca2+ relationship and, thus, an increase in the pCa50 parameters (Table 1). However, the impact of stretch was significantly higher in the ENDO cells compared to the EPI cells. The Hill coefficient increased significantly with stretch in ENDO cells (from 3.5±0.1 to 4.3±0.3), while it decreased in EPI cells (from 4.3±0.1 to 3.6±0.2). Maximal active tension did not differ between the groups. The difference between pCa50 at the long and short SL (ΔpCa50) is an index of LDA; it was significantly smaller in EPI cells compared to the stiffer ENDO cells (Fig. 2b, Table 1). Consistent with this notion, Fig. 2c shows a scatter plot of pCa50 measured at 1.9 and 2.3 μm SL as function of passive tension measured in relaxing solution at 1.9 and 2.3 μm SL, respectively. These data clearly indicate a strong positive correlation between myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity and strain-induced passive force development of the guinea pig cardiac myocyte.

Fig. 2.

Relationship between the relative tension and calcium in ENDO and EPI cells at two sarcomere lengths. a Changes of calcium sensitivity of the contractile machinery are indicated by the leftward shift of the tension–pCa curve when cells were stretched from 1.9 μm SL (closed symbols) to 2.3 μm SL (open symbols; n=14 cells per region). b Stretch-induced calcium sensitization (ΔpCa50) was more prominent in ENDO cells. c Relationship between calcium sensitivity and passive tension for all data from ENDO and EPI at two sarcomere lengths. Passive tension was measured in relaxing solution prior each activation procedure from slack length to 1.9 or 2.3 μm SL (y=5.47+ 0.011x, r=−0.82, P<0.001). d Skinned muscle strips dissected from the sub-epicardial layer (full bar) or the sub-endocardial layer (hatched bar) were quick-frozen either at slack length (open bar) or after stretch to 20–30% of the slack length (grey bar). Left: immunoblots with anti-cardiac TnI and anti-cTnI phosphorylated by PKA showed that TnI phosphorylation was not affected by stretch (n= 6 animals/group). Middle: for MLC-2 phosphorylation quantification, each isoform was separated and expressed as a percentage of the total amount (phosphorylated + non-phosphorylated forms). Right: Immunoblots with anti-cardiac MyBP-C and anti-phospho Ser282 cMyBP-C showed that cMyBP-C phosphorylation level was increased by stretch (n=6 animals/group). Isoprenaline stimulation (Iso) of intact myocytes was used as control for full phosphorylation of MyBP-C. *P<0.05

Table 1.

Sub-epicardial and sub-endocardial myocytes mechanical properties

| Parameter | n | SL 1.9 μm |

SL 2.3 μm |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tpass mN/mm2 | Tmax mN/mm2 | pCa50 | nH | Tpass mN/mm2 | Tmax mN/mm2 | pCa50 | nH | ΔpCa50 | ||

| EPI | 14 | 0.5±0.1 | 25±4 | 5.52±0.02 | 4.3±0.1 | 1.5±0.2* | 23±3 | 5.61±0.02* | 3.6±0.2* | 0.09±0.01 |

| ENDO | 14 | 0.6±0.1 | 22±2 | 5.56±0.02 | 3.5±0.1** | 2.4±0.2*,** | 20±1 | 5.75±0.03*,** | 4.3±0.3*,** | 0.19±0.01** |

Values are means±SEM. Passive (Tpass) and maximal active (Tmax) tensions in mN/mm2 were measured at pCa 9 and 4.5, respectively and at short and long sarcomere length (SL), on sub-epicardial (EPI), and sub-endocardial (ENDO). pCa50, pCa for half-maximal activation and nH, Hill coefficient were obtained by fitting the force–pCa relations. n is the number of cells

Significant difference from short SL (P<0.05).

Significant difference from sub-epicardial cells (P<0.05).

TnI and MLC-2 phosphorylation is known to induce a shift in the tension–pCa curves in cardiac muscle. Western blot analysis was performed on skinned muscle strips dissected from either sub-endocardial layer or sub-epicardial layer, and quick-frozen either at slack length or after a 20–30% stretch (approximately equivalent to a SL stretch from 1.9 to 2.3 μm). As shown in Fig. 2d, phosphorylation of TnI on the PKA sites was not significantly different between regions, before or after stretch. Basal phosphorylation of MLC-2 was higher in EPI cells compared with ENDO confirming previous results [9, 15]. Of note, stretch of ENDO skinned muscles, but not EPI, induced significant additional phosphorylation of MLC-2. MyBP-C phosphorylation has been proposed to affect contractile properties. The level of phosphorylation of cMyBP-C on Ser282 (PKA and Cam-Kinase sites) relative to the total cMyBP-C was similar between EPI and ENDO at slack length (Fig. 2d). Stretch increased phosphorylation of cMyBP-C in both cell types, but this increase was larger and significant only in the ENDO samples.

Rate constant of tension redevelopment of sub-epicardial and sub-endocardial cells

It has been reported that stretch induces an increase in molecular cooperativity, a mechanism that could be, in part, responsible for the increase in Ca2+ sensitivity of tension [2, 27]. Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that cross-bridge cycling kinetics are differentially affected by stretch in skinned EPI and ENDO cells. Measurement of Ktr provides an estimate of the cross-bridge transition kinetics between weak-binding, non-force-generating states and strong-binding, force generating states; the method is illustrated in Fig. 3a. As was the case for the force–[Ca2+] relationships, Ktr at intermediate pCa was more sensitive to SL in ENDO myocytes compared to EPI myocytes (Fig. 3b). Indeed, there was a leftward shift of the relative Ktr–pCa relationship in ENDO cells stretched from 1.9 to 2.3 μm SL (pCa50 5.59±0.01 and 5.86±0.03, respectively). Stretch of the EPI cells, on the other hand, had no effect on this relationship (pCa50 5.77±0.03 and 5.75±0.07 for SL=1.9 and 2.3 μm). Furthermore, SL did not affect the relationship between relative Ktr and active force development in either cell type (data not shown). Finally, maximum Ca2+ saturated Ktr was significantly higher in EPI cells compared to ENDO cells at both short (+23%) and long SL (+30%), while SL by itself did not affect maximum Ktr (Table 2).

Table 2.

Kinetic of force redevelopment of sub-epicardial and sub-endocardial cardiomyocytes

| Parameter | n | SL (μm) | pCa 5.8 | 5.7 | 5.6 | 5.5 | 5 | 4.5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPI | 8 | 1.9 | 0.87±0.17 | 1.01±0.07 | 1.24±0.14 | 1.72±0.14 | 2.53±0.22 | 2.90±0.18 |

| 2.3 | 0.93±0.13 | 1.20±0.18 | 1.48±0.24 | 1.95±0.18 | 2.57±0.22 | 3.16±0.26 | ||

| ENDO | 8 | 1.9 | 0.67±0.03 | 0.62±0.07** | 0.89±0.11** | 1.48±0.17 | 2.12±0.19 | 2.35±0.23** |

| 2.3 | 1.07±0.14* | 1.17±0.14* | 1.33±0.16* | 1.41±0.17 | 1.76±0.21 | 2.45±0.28** |

Values are means±SEM. Ktr, rate constant of force development was expressed in s−1. n is the number of cells

Significant difference from short SL (P<0.05)

Significant difference from sub-epicardial cells (P<0.05)

Regional variation in myosin isoform expression has been reported previously in rat myocardium and that could explain the differences in Ktr observed between ENDO and EPI myocytes. β-MyHC content was measured by Western blot analysis. There was a tendency for EPI cells to express more α-MyHC than ENDO cells (p=0.06), consistent with the higher maximum Ktr parameter observed in EPI cells (Fig. 3; Table 2).

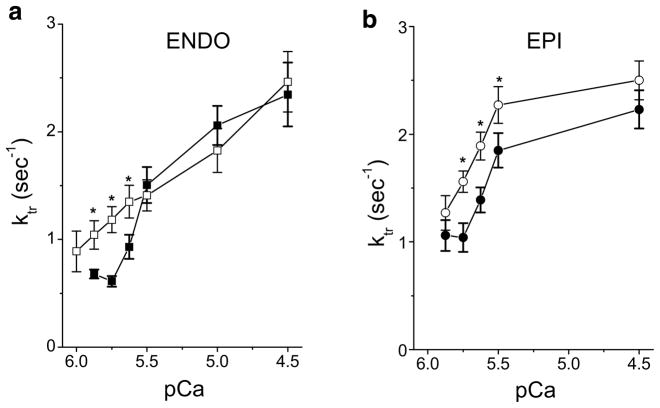

Passive tension dependency of the rate constant of tension redevelopment

Considering the implication of passive tension in the LDA mechanism, the lack of effect of stretch on Ktr in EPI cells could be due also to the difference of passive tension development. To test this hypothesis, EPI cells were stretched to higher SL (≈2.45 μm) to match the level of passive tension of ENDO cells (≈2.4 mN/mm2). In these conditions, we observed a significant increase of Ktr for submaximal Ca2+ activation in EPI cells as observed for ENDO cells (Fig. 4). This result further confirms the importance of stretch-induced passive stress on myofilament function.

Fig. 4.

Passive tension dependency of the rate constant of tension redevelopment in ENDO (a) and EPI (b) myocytes. Ktr was measured in myocytes at short sarcomere length (closed symbols) and at a long sarcomere length developing a passive tension of about 2.4 mN/mm2 (open symbols) corresponding to a stretch of 2.3 μm SL for ENDO cells (n=14) and about 2.45 μm SL for EPI cells (n=10). *P<0.05

Discussion

The goal of this study was to examine the contribution of myofilament contractile proteins (MyHC, titin, cMyBP-C, cTnI, and MLC-2) to regional contractile function in guinea pig myocardium at various sarcomere lengths. We took advantage of existing heterogeneity of the LDA mechanism within the same heart across the left ventricle to investigate the relationship between stretch, phosphorylation of sarcomeric proteins, and two parameters of force, myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity, and kinetics of force development, in skinned myocardium of guinea pig. Guinea pig heart presents the advantage of having a contractile machinery composition closer to human than neither do rat or mouse hearts (e.g., for MyHC and titin isoforms compositions). Our results demonstrate a transmural MyHC isoform distribution that may be responsible for the regional differences in cross-bridge cycling kinetics. We also observed that passive force induced by stretch correlates with myofilament contractile properties. In addition, high level of passive tension development was associated with increased phosphorylation of MLC-2 and MyBP-C. We conclude that transmural MyHC isoform expression and differential regulatory protein phosphorylation after stretch contributes to regional differences in stretch modulation of activation in guinea pig left ventricle.

Passive tension-based modulation

We found a close relationship between Ca2+ sensitivity of force and the level of passive tension. The current results are consistent with previous observations in rat and bovine myocardium [9, 11, 12, 18]. In general, high LDA is correlated with a high level of passive tension. This is true within the same cardiac tissue in which passive tension has been modified either by changing the pre-history of stretch before activation [12], by phosphorylation of titin with PKA [3, 19], high and low passive tension between atrium and ventricle [19], or between myocytes isolated from various places of the ventricle with various cellular passive stiffness ([9], present study). Differential titin isoform expression across the LV wall have been found in pig [6] but not in goat [37] and rat [9]. In the present study, we found no difference in either titin content or titin isoform distribution between ENDO and EPI cells indicating that other mechanisms must participate in the passive tension difference across the wall. Possible mechanisms include titin phosphorylation, titin–actin interaction, Ca2+ binding to titin modulating titin mechanics, or intermediate filament contribution [21]. We previously observed a difference in passive tension between intact EPI and ENDO myocytes isolated from rat, ferret, and guinea pig hearts, which was shown to be titin-isoform-independent [7, 8]. Such transmural heterogeneity of passive tension and the possible titin-isoform contribution remains to be determined in large animals. The mechanism whereby passive force modulates myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity is not known. It has been suggested that a passive tension-based mechanism directly influences cross-bridge interaction with actin. One proposed mechanism is that titin strain imposes a radial force on the sarcomere lattice to modulate inter-filament spacing thus leading to altered myosin–actin interaction and myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity [12, 19]. However, X-ray diffraction studies on skinned myocardium have questioned the role of interfilament spacing in directly modulating myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity and proposed that the disposition of myosin heads was a more predictive index [17]. Several other factors, such as phosphorylation of MLC-2 or cMyBP-C are also known to affect the arrangement of myosin heads.

Myosin light chain-2 modulation

Under physiological conditions, the level of MLC-2 phosphorylation is maintained relatively constant by a balance between the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase (MLCK) and a MLC phosphatase. In the present study, we observed a significant increase in the phosphorylation of the regulatory protein MLC-2 upon stretch, particularly in myocytes with high LDA. Similar results have been observed in rat myocardium [9]. It is now accepted that MLC2-phosphorylation increases myofibrillar Ca2+ sensitivity [9, 38, 40], possibly by increasing the population of myosin heads that can interact with actin [35]. The amount of phosphorylated MLC-2 increases in Endo cells by ≈8% after stretch. This represents about 40% increase upon stretch of the myocardium. Eight percent increase is rather small compared to ≈40% increase in phosphorylated MLC-2 observed in studies in which the skinned preparations were first dephosphorylated by BDM application and then phosphorylated with exogenous MLCK [38]. However, the 8% increase in MLC-2 phosphorylation observed here may be sufficient to explain the difference in myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity observed between EPI and ENDO cells at long SL. A similar change in MLC-2 phosphorylation between control and failing human cardiomyocytes has been found to correlate with a similar decrease in myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity [47]. MLC-2 phosphorylation by MLCK has been shown to increase the rate constant of force redevelopment of skinned cardiac muscle fibers at both low and high Ca2+ activation [35] and thus may have participated in the Ktr increase observed in ENDO cells at submaximal Ca2+ activation after stretch. The change in phosphorylation after stretch suggests that the enzyme system leading to MLC-2 phosphorylation is still present despite the skinning procedure, possibly being bound to the endo- and/or exocytoskeleton. This is consistent with immunofluorescent staining of cardiac tissues showing colocalisation of MLCK and MLC-2 [15]. A recent study identified a new cardiac-specific MLCK, which occasionally showed a striated pattern not overlapping with MLC-2 in A bands but overlapping with actin in I bands [13]. Interestingly its catalytic activity does not appear to be regulated by Ca2+/calmodulin in vitro that may suggest a Ca2+-independent specific function in the heart. This is in accordance with the lack of consistent increase in MLC-2 phosphorylation seen with elevation of cytoplasmic [Ca2+] [13, 24, 26]. Whether the stretch-induced phosphorylation of MLC-2 is fast enough to participate in the beat-to-beat regulation of Frank–Starling is still unresolved. MLC-2 phosphorylation levels do not change during systole and diastole due to continuous activation of MLCK and low MLC-phosphatase activity [35]. The half-time of inactivation of skeletal MLCK is 1.3 s in situ; however, this value is not known for cardiac tissue and for MLCK activation. Finally, MLCK activity is modulated by both PKA and PKC activities, and by Ca2+/calmodulin interaction, thus offering a wide spectrum of potential regulators under acute stretch [14, 22].

Myosin-binding protein-C modulation

It has been suggested that phosphorylation of MyBP-C performs a permissive role in contraction of the heart [49]. Phosphorylation of MyBP-C may decrease the restriction of myosin and would thereby facilitate changes in actin–myosin interaction upon (de)phosphorylation of MLC-2. In our experiments, stretch induced a significant increase of cMyBP-C phosphorylation on Ser282 (Ca2+-calmodulin kinase and PKA dependent site) in myocytes with high LDA (ENDO). The cMyBP-C dependence of myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity is controversial, which is possibly due to differences in models and experimental conditions. At short SL (1.8–2.1 μm), Ca2+ sensitivity is increased after partial extraction of cMyBP-C [28], replacement by a truncated form [50], and in cMyBP-C Knockout mouse model [10, 41]. As have other groups, we recently observed that at long SL (>2.2 μm) Ca2+ sensitivity is not affected by ablation of cMyBP-C [10, 23, 46]. These results suggest that cMyBP-C phosphorylation at long SL is not directly responsible for the increase in Ca2+ sensitivity but may render MLC-2 phosphorylation more efficient. In addition, cMyBP-C phosphorylation may affect other contractile parameters such as cross-bridge cycling kinetics. Indeed, ablation of cMyBP-C [44] and PKA-induced phosphorylation of cMyBP-C [46] both induce accelerated cross-bridge cycling kinetics by eliminating or accelerating cooperative cross-bridge recruitment. It has been proposed that during PKA stimulation, the primary effect of TnI phosphorylation is to reduce Ca2+ sensitivity of force, whereas phosphorylation of cMyBP-C accelerates the kinetics of force development [46]. This is consistent with the increase in Ktr observed here after stretch in myocytes with high LDA concomitant with a higher cMyBP-C phosphorylation.

Myosin heavy chain composition

MyHC has been shown to be a key determinant of the rate of tension redevelopment. That is, α-MyHC is associated with faster cross-bridge cycling kinetics and Ktr compared with β-MyHC [43]. Regional variation in the myosin isoform has been reported previously in both rabbit [16] and rat myocardium [5] with higher β-MyHC content in the sub-endocardium. A similar trend was observed in our study. The SL dependence of Ktr has previously been addressed by others [33, 45] showing a similar Ktr at maximal Ca2+ activation, but faster Ktr at force-matched submaximal Ca2+ activation in rat skinned trabeculae. This finding is consistent with our study in which maximal Ktr was not affected by length change in ENDO and EPI myocytes, but increased at intermediate levels of contractile activation with stretch in ENDO cells compared to EPI cells (cf. Fig. 3). This result may be explained, at least in part, by the higher β-MyHC content observed in Endo cells. A recent study showed that the Ktr parameter was length-sensitive in rat myocytes expressing β-MyHC after 6-propyl-2-thiouracil treatment, but not in α-MyHC myocytes [33]. The lack of stretch effect on Ktr in EPI cells that express a larger amount of α-MyHC could be due also to the difference of passive tension development. Indeed, when EPI cells were stretched to a higher SL (≈2.45 μm), so as to match the level of passive tension of ENDO cells, we observed a significant increase of Ktr for submaximal Ca2+ activation (Fig. 4). This result further confirms the importance of passive stress developed after stretch on the myofilaments.

Summary

Our results are consistent with a molecular model in which passive force induced by stretch affects myofilament contractile properties both via a direct mechanical coupling mechanism (through interfilament lattice spacing for example) and via modification of protein kinase and/or protein phosphate activity upon stretch that affects regulatory proteins such as MLC-2 and MyBP-C. A stiffer sarcomere would be expected to provide a higher level of strain on such a mechanical kinase/phosphatase stress transduction system. Likewise, modulation of sarcomere stiffness, by whatever means, would also modulate this transduction pathway, contractile protein phosphorylation and, as a result, myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity. Although the location of this mechanical transduction system cannot be determined from the present study, recent results suggest that it may well be located in the z-disk, a structure now known to be the locus of many kinases and phosphates and ideally situated mechanically within sarcomeres to sense cellular strain [42].

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the “Association Française contre les Myopathies”, and “Région Languedoc-Roussillon”. OC is an established investigator of CNRS. PPT was supported by INSERM and NIH grants HL-62426; HL-75494; HL-77195. Thanks are due to Guillermo Salazar for technical assistance.

Contributor Information

Younss Ait mou, INSERM, U 637, Université MONTPELLIER I, UFR de Médecine, F-34295 Montpellier, France.

Jean-Yves le Guennec, INSERM E0211, F-37032 Tours, France.

Emilio Mosca, INSERM E0211, F-37032 Tours, France.

Pieter P. de Tombe, INSERM, U 637, Université MONTPELLIER I, UFR de Médecine, F-34295 Montpellier, France, Center for Cardiovascular Research, University of Illinois, Chicago, IL 60612, USA

Olivier Cazorla, Email: cazorla@montp.inserm.fr, INSERM, U 637, Université MONTPELLIER I, UFR de Médecine, F-34295 Montpellier, France, Physiopathologie Cardiovasculaire, INSERM U637, CHU Arnaud de Villeneuve, 34295 Montpellier Cedex 5, France.

References

- 1.Allen DG, Kentish JC. Calcium concentration in the myoplasm of skinned ferret ventricular muscle following changes in muscle length. J Physiol. 1988;407:489–503. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balnave CD, Allen DG. The effect of muscle length on intracellular calcium and force in single fibres from mouse skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 1996;492:705–713. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borbely A, van der Velden J, Papp Z, Bronzwaer JG, Edes I, Stienen GJ, Paulus WJ. Cardiomyocyte stiffness in diastolic heart failure. Circulation. 2005;111:774–781. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000155257.33485.6D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenner B, Eisenberg E. Rate of force generation in muscle: correlation with actomyosin ATPase activity in solution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:3542–3546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.10.3542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bugaisky LB, Anderson PG, Hall RS, Bishop SP. Differences in myosin isoform expression in the subepicardial and subendocardial myocardium during cardiac hypertrophy in the rat. Circ Res. 1990;66:1127–1132. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.4.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cazorla O, Freiburg A, Helmes M, Centner T, Mcnabb M, Wu Y, Trombitas K, Labeit S, Granzier H. Differential expression of cardiac titin isoforms and modulation of cellular stiffness. Circ Res. 2000;86:59–67. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cazorla O, Le Guennec JY, White E. Length–tension relationships of sub-epicardial and sub-endocardial single ventricular myocytes from rat and ferret hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:735–744. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cazorla O, Pascarel C, Garnier D, Le Guennec JY. Resting tension participates in the modulation of active tension in isolated guinea pig ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:1629–1637. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cazorla O, Szilagyi S, Le Guennec JY, Vassort G, Lacampagne A. Transmural stretch-dependent regulation of contractile properties in rat heart and its alteration after myocardial infarction. Faseb J. 2005;19:88–90. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2066fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cazorla O, Szilagyi S, Vignier N, Salazar G, Kramer E, Vassort G, Carrier L, Lacampagne A. Length and protein kinase A modulations of myocytes in cardiac myosin binding protein C-deficient mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;69:370–380. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cazorla O, Vassort G, Garnier D, Le Guennec JY. Length modulation of active force in rat cardiac myocytes: is titin the sensor. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1999;31:1215–1227. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1999.0954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cazorla O, Wu Y, Irving TC, Granzier H. Titin-based modulation of calcium sensitivity of active tension in mouse skinned cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2001;88:1028–1035. doi: 10.1161/hh1001.090876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan JY, Takeda M, Briggs LE, Graham ML, Lu JT, Horikoshi N, Weinberg EO, Aoki H, Sato N, Chien KR, Kasahara H. Identification of cardiac-specific myosin light chain kinase. Circ Res. 2008;102:571–580. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.161687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clement O, Puceat M, Walsh MP, Vassort G. Protein kinase C enhances myosin light-chain kinase effects on force development and ATPase activity in rat single skinned cardiac cells. Biochem J. 1992;285:311–317. doi: 10.1042/bj2850311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis JS, Hassanzadeh S, Winitsky S, Lin H, Satorius C, Vemuri R, Aletras AH, Wen H, Epstein ND. The overall pattern of cardiac contraction depends on a spatial gradient of myosin regulatory light chain phosphorylation. Cell. 2001;107:631–641. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00586-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisenberg BR, Edwards JA, Zak R. Transmural distribution of isomyosin in rabbit ventricle during maturation examined by immunofluorescence and staining for calcium-activated adenosine triphosphatase. Circ Res. 1985;56:548–555. doi: 10.1161/01.res.56.4.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farman GP, Walker JS, de Tombe PP, Irving TC. Impact of osmotic compression on sarcomere structure and myofilament calcium sensitivity of isolated rat myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H1847–1855. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01237.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukuda N, Sasaki D, Ishiwata S, Kurihara S. Length dependence of tension generation in rat skinned cardiac muscle: role of titin in the Frank–Starling mechanism of the heart. Circulation. 2001;104:1639–1645. doi: 10.1161/hc3901.095898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukuda N, Wu Y, Farman G, Irving TC, Granzier H. Titin isoform variance and length dependence of activation in skinned bovine cardiac muscle. J Physiol (Lond) 2003;553:147–154. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.049759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Granzier HL, Irving TC. Passive tension in cardiac muscle: contribution of collagen, titin, microtubules, and intermediate filaments. Biophys J. 1995;68:1027–1044. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80278-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Granzier HL, Labeit S. The giant protein titin: a major player in myocardial mechanics, signaling, and disease. Circ Res. 2004;94:284–295. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000117769.88862.F8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grimm M, Mahnecke N, Soja F, El-Armouche A, Haas P, Treede H, Reichenspurner H, Eschenhagen T. The MLCK-mediated alpha1-adrenergic inotropic effect in atrial myocardium is negatively modulated by PKCepsilon signaling. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148:991–1000. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris SP, Rostkova E, Gautel M, Moss RL. Binding of myosin binding protein-C to myosin subfragment S2 affects contractility independent of a tether mechanism. Circ Res. 2004;95:930–936. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000147312.02673.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herring BP, England PJ. The turnover of phosphate bound to myosin light chain-2 in perfused rat heart. Biochem J. 1986;240:205–214. doi: 10.1042/bj2400205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hibberd MG, Jewell BR. Calcium-and length-dependent force production in rat ventricular muscle. J Physiol. 1982;329:527–540. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.High CW, Stull JT. Phosphorylation of myosin in perfused rabbit and rat hearts. Am J Physiol. 1980;239:H756–H764. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1980.239.6.H756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hofmann PA, Fuchs F. Effect of length and cross-bridge attachment on Ca2+ binding to cardiac troponin C. Am J Physiol. 1987;253:C90–C96. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1987.253.1.C90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hofmann PA, Hartzell HC, Moss RL. Alterations in CA2+ sensitive tension due to partial extraction of c-protein from rat skinned cardiac myocytes and rabbit skeletal muscle fibers. J Gen Physiol. 1991;97:1141–1163. doi: 10.1085/jgp.97.6.1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kentish JC, Mccloskey DT, Layland J, Palmer S, Leiden JM, Martin AF, Solaro RJ. Phosphorylation of troponin I by protein kinase A accelerates relaxation and crossbridge cycle kinetics in mouse ventricular muscle. Circ Res. 2001;88:1059–1065. doi: 10.1161/hh1001.091640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kobayashi T, Solaro RJ. Calcium, thin filaments, and the integrative biology of cardiac contractility. Annu Rev Physiol. 2005;67:39–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.040403.114025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Konhilas JP, Irving TC, de Tombe PP. Myofilament calcium sensitivity in skinned rat cardiac trabeculae: role of interfilament spacing. Circ Res. 2002;90:59–65. doi: 10.1161/hh0102.102269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Konhilas JP, Irving TC, Wolska BM, Jweied EE, Martin AF, Solaro RJ, Tombe PPD. Troponin I in the murine myocardium: influence on length-dependent activation and inter-filament spacing. J Physiol (Lond) 2003;547:951–961. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.038117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Korte FS, McDonald KS. Sarcomere length dependence of rat skinned cardiac myocyte mechanical properties: dependence on myosin heavy chain. J Physiol. 2007;581:725–739. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.128199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kruger M, Kohl T, Linke WA. Developmental changes in passive stiffness and myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity due to titin and troponin-I isoform switching are not critically triggered by birth. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H496–H506. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00114.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morano I. Tuning the human heart molecular motors by myosin light chains. J Mol Med. 1999;77:544–555. doi: 10.1007/s001099900031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moss RL, Fitzsimons DP. Frank-starling relationship: long on importance, short on mechanism. Circ Res. 2002;90:11–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neagoe C, Opitz CA, Makarenko I, Linke WA. Gigantic variety: expression patterns of titin isoforms in striated muscles and consequences for myofibrillar passive stiffness. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2003;24:175–189. doi: 10.1023/a:1026053530766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olsson MC, Patel JR, Fitzsimons DP, Walker JW, Moss RL. Basal myosin light chain phosphorylation is a determinant of Ca2+ sensitivity of force and activation dependence of the kinetics of myocardial force development. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H2712–2718. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01067.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pearson JT, Shirai M, Tsuchimochi H, Schwenke DO, Ishida T, Kangawa K, Suga H, Yagi N. Effects of sustained length-dependent activation on in situ cross-bridge dynamics in rat hearts. Biophys J. 2007;24:4319–4329. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.111740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pi Y, Zhang D, Kemnitz KR, Wang H, Walker JW. Protein kinase C and A sites on troponin I regulate myofilament CA2+ sensitivity and ATPase activity in the mouse myocardium. J Physiol. 2003;552:845–857. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.045260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pohlmann L, Kroger I, Vignier N, Schlossarek S, Kramer E, Coirault C, Sultan KR, El-Armouche A, Winegrad S, Eschenhagen T, Carrier L. Cardiac myosin-binding protein C is required for complete relaxation in intact myocytes. Circ Res. 2007;101:928–938. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.158774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pyle WG, Solaro RJ. At the crossroads of myocardial signaling: the role of Z-discs in intracellular signaling and cardiac function. Circ Res. 2004;94:296–305. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000116143.74830.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rundell VLM, Manaves V, Martin AF, de tombe PP. Impact of {beta}-myosin heavy chain isoform expression on cross-bridge cycling kinetics. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H896–H903. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00407.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stelzer JE, Fitzsimons DP, Moss RL. Ablation of myosin-binding protein-C accelerates force development in mouse myocardium. Biophys J. 2006;90:4119–4127. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.078147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stelzer JE, Moss RL. Contributions of stretch activation to length-dependent contraction in murine myocardium. J Gen Physiol. 2006;128:461–471. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stelzer JE, Patel JR, Walker JW, Moss RL. Differential roles of cardiac myosin-binding protein C and cardiac troponin I in the myofibrillar force responses to protein kinase A phosphorylation. Circ Res. 2007;101:503–511. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.153650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van der Velden J, Papp Z, Boontje NM, Zaremba R, de jong JW, Janssen PML, Hasenfuss G, Stienen GJM. The effect of myosin light chain 2 dephosphorylation on Ca2+-sensitivity of force is enhanced in failing human hearts. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57:505–514. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00662-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vannier C, Chevassus H, Vassort G. Ca-dependence of isometric force kinetics in single skinned ventricular cardiomyocytes from rats. Cardiovasc Res. 1996;32:580–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Winegrad S. Cardiac myosin binding protein C. Circ Res. 1999;84:1117–1126. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.10.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Witt CC, Gerull B, Davies MJ, Centner T, Linke WA, Thierfelder L. Hypercontractile properties of cardiac muscle fibers in a knock-in mouse model of cardiac myosin-binding protein-C. J Biol Chem. 2000;84:10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008691200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]