Abstract

Sports related injuries such as impact and stress fractures often require a rehabilitation program to stimulate bone formation and accelerate fracture healing. This review introduces a recently developed joint loading modality and evaluates its potential applications to bone formation and fracture healing in post-injury rehabilitation. Bone is a dynamic tissue whose structure is constantly altered in response to its mechanical environments. Indeed, many loading modalities can influence the bone remodeling process. The joint loading modality is, however, able to enhance anabolic responses and accelerate wound healing without inducing significant in situ strain at the site of bone formation or fracture healing. This review highlights the unique features of this loading modality and discusses its potential underlying mechanisms as well as possible clinical applications.

Keywords: joint loading, bone formation, fracture healing, strain, intramedullary pressure

INTRODUCTION

Bone is a metabolically active tissue capable of adapting its structure to varying biophysical stimuli as well as repairing structural damage through remodeling. Daily activities enhance its mechanical strength,1–3 and physical exercises such as swimming,4, 5 climbing,6, 7 jumping,8, 9 and running10, 11 can increase bone mass, density, and strength. Those activities or exercises are, however, mostly performed by healthy individuals12–15 and their efficacy depends on an individual’s weight, muscle strength, and fitness level. For sports-related stress fractures caused by continuous overuse and fractures caused by a blow or a fall, athletes are often required to participate in a rehabilitation program. Those programs typically enhance bone remodeling in a manner which depends on the needs of the individual. Thus, various loading modalities have been developed to extend the loading effects to sports-injured athletes as well as elders and also astronauts.

The results of many load-driven bone adaptation studies16–18 have focused on in situ strain at the site of bone formation.19–21 Not only loading experiments but also exposures to unloading by disuse or spaceflight22 support the role of in situ strain in preventing bone loss. However, recent animal studies using non-habitual loads administered by joint loading indicate that in situ strain is not an absolute requirement for load-driven anabolic responses. This review explains this novel joint loading modality. Herein is described its potential applications for enhancing bone formation and accelerating fracture healing as well as increasing bone length. Two proposed mechanisms underlying joint loading-induced responses are presented and future research directions are suggested.

LOADING MODALITIES

Functional loading modalities

Representative loading modalities, which have been extensively studied in the last 10 or more years, include whole-body vibration,23, 24 axial loading 25, 26, and bending.19, 27 Whole-body vibration applies oscillatory loads under 1 X G earth’s gravity, and dynamically disturbs the mechanical equilibrium state of bone. The strain magnitude induced by whole-body vibration depends on both the size of the applied load as well as the loading frequency. Whole-body vibration can induce anabolic responses mostly in trabecular bone with, for instance, ~ 200 µstrain at 90 Hz loading frequency.28 Axial loading and bending are generally applied to long bones such as ulnae and tibiae. Axial loading exerts principally longitudinal compression, while bending generates lateral compression and tension. Since ulnae and tibiae are naturally curved, axial loading induces not only longitudinal stress but also a bending effect. In tibiae, for instance, axial loading29 and four-point bending30, 31 have been reported to induce a significant increase in bone formation mostly in load-bearing cortical bone.

Role of dynamic strain

Based on previous animal studies with various loading modalities, it is generally accepted that bone adaptation occurs in response to dynamic (rather than static) loading. The effect of loading represents a composite of critical determinants including strain magnitude, strain rate, and number of loading cycles and bouts.20 In mouse ulna axial loading, for instance, dynamic strain above a certain threshold value (1000 – 2000 µstrain) is considered necessary to induce detectable bone formation. Furthermore, the optimal range of loading frequencies is 5 – 10 Hz.26 In whole-body vibration, in contrast, a significantly higher loading frequency (above 1 kHz) is considered to be effective with smaller strain (< 100 µstrain).

JOINT LOADING MODALITY AND BONE FORMATION

Elbow, knee and ankle loading

Joint loading is the most recently developed loading modality. It employs non-habitual loads applied to a synovial joint such as the elbow, the knee, and the ankle. Unlike other loading modalities, it does not appear to depend on load-induced strain at a site of bone formation. Instead, loads are applied laterally to the epiphysis of the synovial joint and induction of bone formation is observed in the metaphysis and diaphysis of long bone.

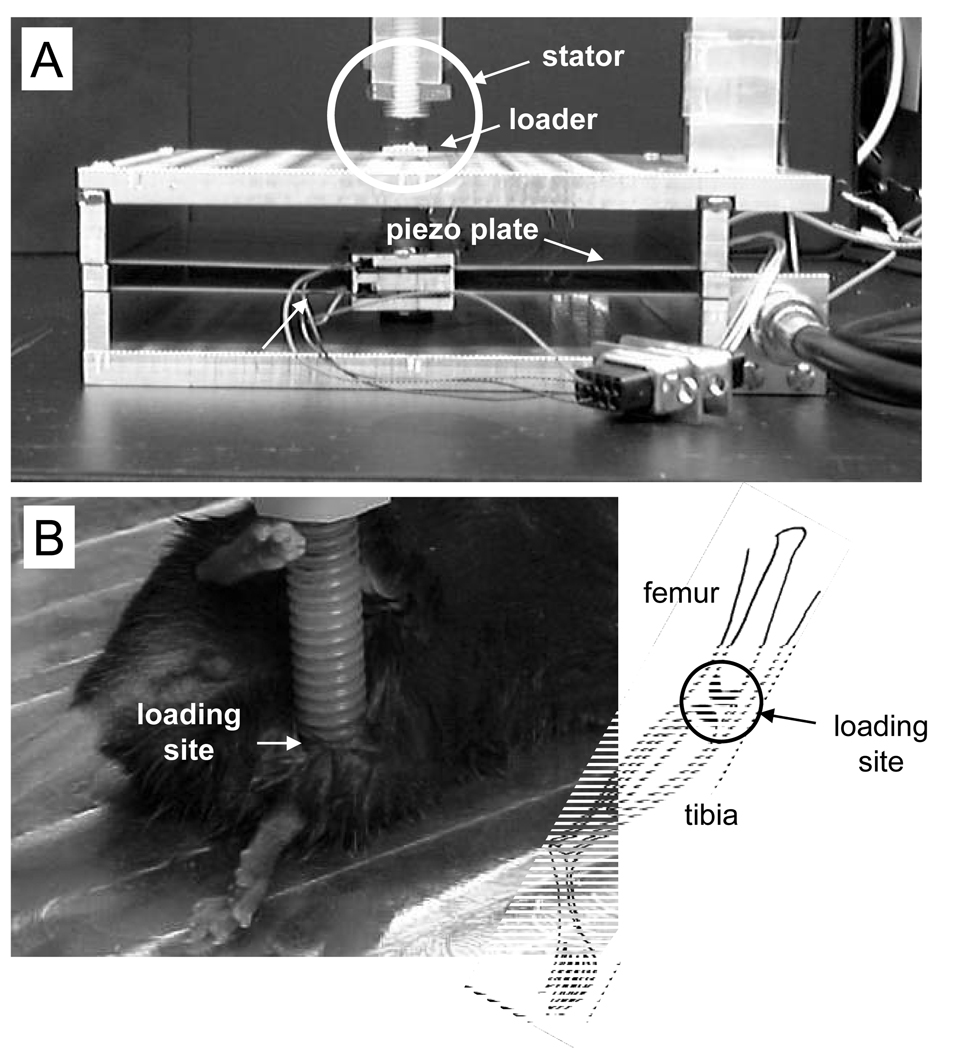

Three forms of joint loading have so far been devised. Using a piezoelectric mechanical loader that can apply well-controlled loads at various waveforms, it has been shown in mouse studies that elbow loading,32, 33 knee loading,34–39 and ankle loading40 are able to induce bone formation in the ulna, tibia and femur, and femur (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Knee loading apparatus used for the mouse model. (A) Piezoelectric mechanical loader showing location of mouse leg during joint loading session. Circled area is shown in (B). (B) Mouse leg during knee loading.

Five noteworthy characteristics of joint loading

Joint loading offers several unique features for mouse studies. First, it requires smaller loads to induce bone formation than most of the other loading modalities. In mouse studies, for instance, axial loading needs ~ 2 N force for elevating bone formation in ulnae, while 0.5 N force is sufficient with elbow loading.

Second, joint loading is effective for inducing bone formation along the length of the entire long bone regardless of the longitudinal distance from the loading site. It has been shown that knee loading is able to induce bone formation not only in the distal diaphysis near the knee but also in the proximal diaphysis near the hip. Likewise, ankle loading is effective on the tibia along its length.40

Third, compared to other loading modalities such as whole-body vibration, the number of required loading bouts is small. For instance, 1000 to 2000 bouts per day for 3 days are sufficient in mouse studies) with in situ strain of ~ 10 µstrain. According to the predicted relationship between strain and the number of daily loading cycles, whole-body vibration requires approximately 200,000 bouts for loading with 10 µstrain.

Fourth, although the periosteal cortical surface is more sensitive than the endosteal surface, both surfaces are responsive to joint loading.37 It is, however, not well understood why the periosteal surface is more sensitive in most of the loading modalities (including joint loading) than the endosteal surface.

Fifth, a loading frequency of 2 – 15 Hz is effective, but existing data suggest that the optimal frequency differs among ulnae, tibiae, and femora.34, 35, 38 Geometry and dimension of each bone appear to affect frequency responses.

FRACTURE HEALING

Requirements for load-driven fracture healing

Although mechanical loading can non-invasively accelerate a process of fracture healing, a seemingly biphasic outcome with high sensitivity to loading intensity (stimulatory in low strain, and destructive in high strain) makes clinical applications somewhat restricted.41, 42 The loading effects apparently depend on stress types (compressive, tensile, and shear) and strain magnitudes.43–49 The results of various animal studies support the notion that relatively low stress or strain promotes callus formation and increases bone strength.50–56 However, application of higher loads appears to result in a deleterious outcome.50

Deformation and induced strain at the site of fractured bone are heavily affected by the method employed for fracture fixation, and healing phases.43, 57 The appropriate loading modality and its magnitude should be closely linked to the type of fracture.43, 58, 59 Furthermore, many loading modalities are often ineffective when fractures are immobilized by a cast.60 Thus, a loading modality that does not require direct contact to the fracture site and induces small mechanical strain would appear to be well suited for accelerating fracture healing.

Healing of surgical wounds with knee loading

Because of its low-strain character, joint loading apparently satisfies the above requirements for fracture healing of long bones. As a preliminary trial, a healing process of surgically generated circular wounds was examined in the mouse tibia with and without knee loading. The results (based on µCT imaging) were promising. Knee loading was able to accelerate closure of the surgical wounds and fasten the remodeling process.61 It would be interesting to know whether knee loading would be effective in fracture healing of a femoral neck, since the femoral neck fracture represents a serious healthcare problem, especially in an aging population.

BONE LENGTHENING

Controversial loading effects

Longitudinal bone growth is the result of chondrocyte proliferation and its subsequent differentiation in the epiphyseal growth plates.62, 63 Although mechanical loading enhances bone formation and adaptation, its effect on bone length, more specifically, stimulatory or inhibitory influences on the growth plate, has been controversial. Some studies on physical exercises or mechanical loading report an increase in height of the growth plate,64 while others show its reduction. Using axial loading of the ulna for rats, it has been demonstrated that longitudinal growth was suppressed in a dosage dependent manner.65

Effects of unloading and knee loading

Lengthening of legs due to unloading during spaceflight has been documented. An important question is whether joint loading, which applies mechanical loads laterally and thereby stretches long bones longitudinally, can mimic the unloading effects of bone lengthening.34, 39 Preliminary data from a recent study using mouse long bones suggest that knee and elbow loading can lengthen the tibia and the femur, and the ulna and the humerus, respectively.

Differences in leg length above a normal variation of 5 – 15 mm potentially cause varying medical symptoms including hip and lower back pain, arthritis, and overuse injuries such as tendonitis.66 In order to reduce lateral ground reaction forces acting predominantly on the short limb, a non-surgical treatment is of course wearing a shoe lift. In severe discrepancy cases, surgical treatments such as shortening the long leg and lengthening the short leg are conducted.67 However, it is controversial how and when either of these invasive procedures should be performed. It has been proposed that insulin growth factor-1 (IGF-1) is effective to lengthen the tibia,68 but clinical data suggest complexity of the effects of IGF-1. It was not yet been examined whether there is a linkage between the mechanical effects of joint loading and hormonal regulation through IGF-1.

POTENTIAL MECHANISMS

Strain gradient and intramedullary pressure

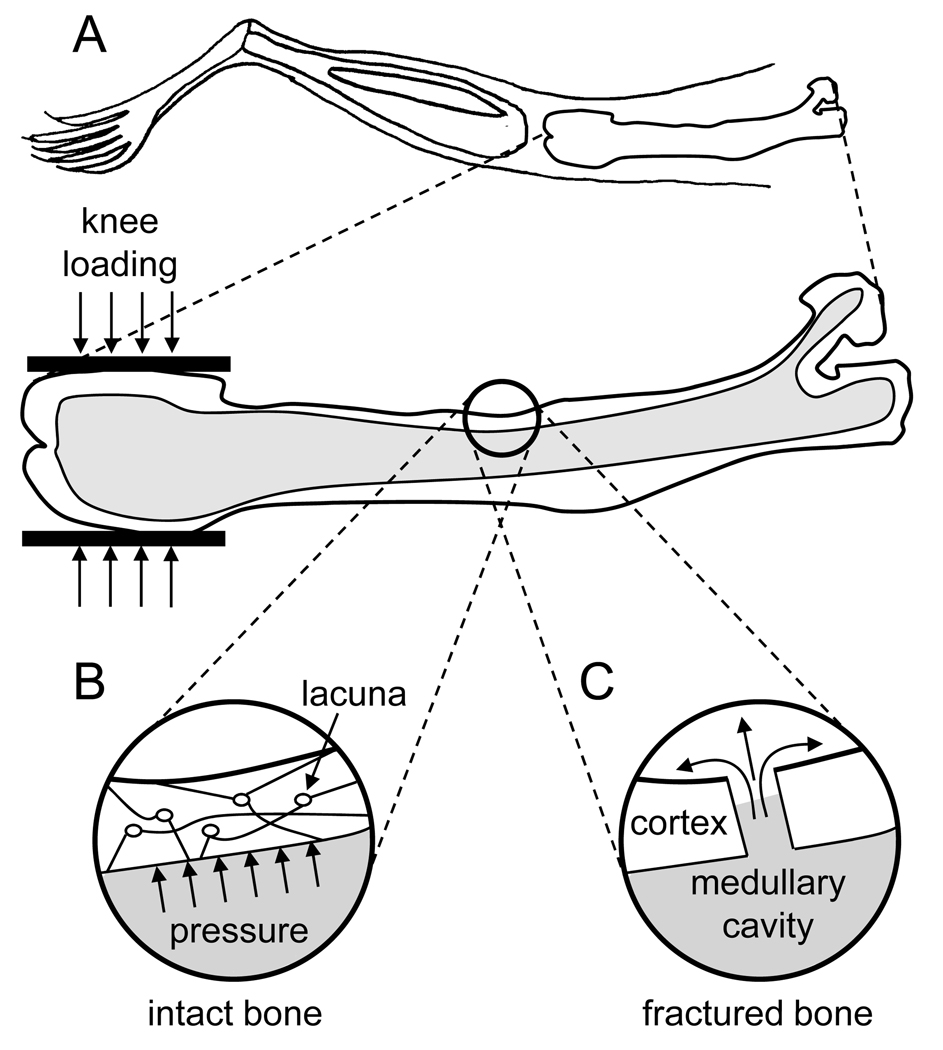

The most likely explanation for the effects of joint loading on bone formation is based on the following biomechanical considerations. Trabecular bone in the epiphysis is less stiff than cortical bone in the diaphysis,69, 70 and Young’s modulus in the lateral direction is smaller than that in the axial direction.71 Therefore, lateral loads to the distal femoral epiphysis can be more effective than any axial loads to any other site in mobilizing interstitial fluid flow from the epiphysis towards metaphysis and the diaphysis. Since the epiphysis and the diaphysis are physically connected, the displaced fluid in the epiphysis could be transferred toward the metaphysis and the diaphysis. The following hypothesis is proposed: joint loading generates a steep strain gradient along the length of long bone and induces oscillatory alterations in intramedullary pressure. The pressure alterations in turn drive fluid flow in the lacunocanalicular network, which might cause shear stress to osteocytes (Fig. 2).36, 39

Figure 2.

Potential mechanisms to account for the effects of joint loading. (A) Schematic illustration of a mouse femur under knee loading using the apparatus shown in Fig. 1. (B) Potential pressure increase in an intact bone cortex. (C) Potential fluid flow in a fracture bone cortex.

Flow in a medullary cavity

The mechanism underlying acceleration of fracture healing with joint loading could be different from that for anabolic responses in intact bone. In intact bone, joint loading may cause cyclic alterations of intramedullary pressure,36, 37 which may affect interstitial molecular transport driven by pressure gradients.39, 72 In fractured bone, in contrast, pressure alterations would be smaller since the damaged medullary cavity may not allow efficient build up of intramedullary pressure. One speculation is that molecular transports in the medullary cavity are activated in the fractured bone along with migration of bone marrow-derived cells. It has been reported that knee loading generates an oscillatory motion of micro particles in a glass tube connected to the surgical hole.36 Further mechanical and cellular examinations are necessary to understand the interplay between the loaded epiphysis and the fractured diaphysis.

CONCLUSIONS

This review has explained that for sports related bone injuries joint loading is potentially an effective rehabilitation method for enhancing bone formation and accelerating wound healing in long bones. Besides the mechanisms underlying the observed load-driven responses, many basic and clinical questions remain to be answered: (a) Can anabolic responses be induced with absolutely no in situ strain in the diaphysis? (b) Does joint loading simulate migration and differentiation of bone marrow-derived cells in fractured bone? (c) Does joint loading reduce bone resorption in addition to inducing bone formation? (d) Can a similar loading modality be developed for strengthening the spine? And (e) Does joint loading provide a therapeutic effect on a jumper’s knee or a runner’s knee? Understanding the mechanisms of bone remodeling and fracture healing promoted by joint loading would likely answer the above questions and contribute to future treatments and therapies in sports medicine for promoting athletes’ bone quality, and for accelerating healing of injured bones in an aging population.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study was in part supported by NIH AR52144.

Footnotes

The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive licence (or non-exclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and its Licensees to permit this article to be published on British Journal of Sports Medicine editions and any other BMJPGL products to exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our license http://bjsm.bmjjournals.com/ifora/licence.pdf”.

There are no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Taylor AH, Cable NT, Faulkner G, et al. Physical activity and older adults: a review of health benefits and the effectiveness of interventions. J Sports Sci. 2004;22:703–725. doi: 10.1080/02640410410001712421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuchs RK, Shea M, Durski SL, et al. Individual and combined effects of exercise and alendronate on bone mass and strength in ovariectomized rats. Bone. 2007;41:290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.04.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turner CH, Robling AG. Mechanisms by which exercise improves bone strength. J Bone Miner Metab. 2005;23:16–22. doi: 10.1007/BF03026318. [review] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang TH, Lin SC, Chang FL, et al. Effects of different exercise modes on mineralization, structure, and biomechanical properties of growing bone. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:300–307. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01076.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hart KJ, Shaw JM, Vajda E, et al. Swim-trained rats have greater bone mass, density, strength, and dynamics. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:1663–1668. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.4.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Notomi T, Okimoto N, Okazaki Y, et al. Effects of tower climbing exercise on bone mass, strength, and turnover in growing rats. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:166–174. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mori T, Okimoto N, Sakai A, et al. Climbing exercise increases bone mass and trabecular bone turnover through transient regulation of marrow osteogenic and osteoclastogenic potentials in mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:2002–2009. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.11.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Honda A, Sogo N, Nagasawa S, et al. High-impact exercise strengthens bone in osteopenic ovariectomized rats with the same outcome as Sham rats. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:1032–1037. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00781.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kodama Y, Umemura Y, Nagasawa S, et al. Exercise and mechanical loading increase periosteal bone formation and whole bone strength in C57BL/6J mice but not in C3H/Hej mice. Calcif Tissue Int. 2000;66:298–306. doi: 10.1007/s002230010060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wallace JM, Rajachar RM, Allen MR, et al. Exercise-induced changes in the cortical bone of growing mice are bone-and gender-specific. Bone. 2007;40:1120–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu J, Wang XX, Higuchi M, et al. High bone mass gained by exercise in growing male mice is increased by subsequent reduced exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:806–810. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01169.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang JY, Nam JH, Park H, et al. Effects of resistance exercise and growth hormone administration at low doses on lipid metabolism in middle-aged female rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;539:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.03.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mosley JR. Osteoporosis and bone functional adaptation: mechanobiological regulation of bone architecture in growing and adult bone, a review. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2000;37:189–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chestnut CH. Bone mass and exercise. Am J Med. 1993;95:34S–36S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90379-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rittweger J. Can exercise prevent osteoporosis? J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2006;6:162–166. [review] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubin J, Rubin C, Jacobs CR. Molecular pathways mediating mechanical signaling in bone. Gene. 2006;367:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.10.028. [review] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burr DB, Robling AG, Turner CH. Effects of biomechanical stress on bones in animals. Bone. 2002;30:781–786. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00707-x. [review] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubin C, Turner AS, Muller R, et al. Quantity and quality of trabecular bone in the femur are enhanced by a strongly anabolic, noninvasive mechanical intervention. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:349–357. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.2.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LaMothe JM, Hamilton NH, Zernicke RF. Strain rate influences periosteal adaptation in mature bone. Med Eng Phys. 2005;27:277–284. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turner CH. Three rules for bone adaptation to mechanical stimuli. Bone. 1998;23:399–407. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cullen DM, Smith RT, Akhter MP. Bone-loading response varies with strain magnitude and cycle number. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:1971–1976. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.5.1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shackelford LC, LeBlanc AD, Driscoll TB, et al. Resistance exercise as a countermeasure to disuse-induced bone loss. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:119–129. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00741.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubin C, Turner AS, Bain S, et al. Anabolism. Low Mechanical signals strengthen long bones. Nature. 2001;412:603–604. doi: 10.1038/35088122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flieger J, Karachalios T, Khaldi L, et al. Mechanical stimulation in the form of vibration prevents postmenopausal bone loss in ovariectomized rats. Calcif Tissue Int. 1998;63:510–514. doi: 10.1007/s002239900566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Souza RL, Matsuura M, Eckstein F, et al. Non-invasive axial loading of mouse tibiae increases cortical bone formation and modifies trabecular organization: a new model to study cortical and cancellous compartments in a single loaded element. Bone. 2005;37:810–818. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warden SJ, Turner CH. Mechanotransduction in cortical bone is most efficient at loading frequencies of 5–10 Hz. Bone. 2004;34:261–270. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kesavan C, Mohan S, Srivastava AK, et al. Identification of genetic loci that regulate bone adaptive response to mechanical loading in C57BL/6J and C3H/HeJ mice intercross. Bone. 2006;39:634–643. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Judex S, Lei X, Han D, et al. Low-magnitude mechanical signals that stimulate bone formation in the ovariectomized rat are dependent on the applied frequency but not on the strain magnitude. J Biomech. 2007;40:1333–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Souza RL, Matsuura M, Eckstein F, et al. Non-invasive axial loading of mouse tibiae increases cortical bone formation and modifies trabecular organization: a new model to study cortical and cancellous compartments in a single loaded element. Bone. 2005;37:810–818. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hagino H, Kuraoka M, Kameyama Y, et al. Effect of a selective agonist for prostaglandin E receptor subtype EP4 (ONO-4819) on the cortical bone response to mechanical loading. Bone. 2005;36:444–453. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kameyama Y, Hagino H, Okano T, et al. Bone response to mechanical loading in adult rats with collagen-induced arthritis. Bone. 2004;35:948–956. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanaka SM, Sun HB, Yokota H. Bone formation induced by a novel form of mechanical loading on joint tissue. Biol Sci Space. 2004;18:41–44. doi: 10.2187/bss.18.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yokota H, Tanaka SM. Osteogenic potentials with joint-loading modality. J Bone Miner Metab. 2005;23:302–308. doi: 10.1007/s00774-005-0603-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang P, Tanaka SM, Jiang H, et al. Diaphyseal bone formation in murine tibiae in response to knee loading. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100:1452–1459. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00997.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang P, Su M, Tanaka SM, et al. Knee loading causes diaphyseal cortical bone formation in murine femurs. BMC Musculoskel Dis. 2006;73:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-7-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang P, Su M, Liu Y, et al. Knee loading dynamically alters intramedullary pressure in mouse femora. Bone. 2007;40:538–543. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang P, Yokota H. Effects of surgical holes in mouse tibiae on bone formation induced by knee loading. Bone. 2007;40:1320–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang P, Tanaka S, Sun Q, et al. Frequency-dependent enhancement of bone formation in murine tibiae and femora with knee loading. J Bone Miner Metab. 2007;25 doi: 10.1007/s00774-007-0774-8. [in press] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Warden SJ. Breaking the rules for bone adaptation to mechanical loading. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100:1441–1442. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00038.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang P, Cui M, Yang D, et al. Tibial bone formation with novel ankle loading. Proc 53rd Annual ORS Meeting. 2007:1400. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Augat P, Burger J, Schorlemmer S, et al. Shear movement at the fracture site delays healing in a diaphyseal fracture model. J Orthop Res. 2003;21:1011–1017. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(03)00098-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolf S, Augat P, Eckert-Hubner K, et al. Effects of high-frequency, low-magnitude mechanical stimulus on bone healing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;385:192–198. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200104000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Augat P, Simon U, Liedert A, et al. Mechanics and mechano-biology of fracture healing in normal and osteoporotic bone. Osteoporos Int. 2004;16:S36–S43. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1728-9. [review] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gardner MJ, van der Meulen MCH, Demetrakopoulos D, et al. In vivo cyclic axial compression affects bone healing in the mouse tibia. J Orthop Res. 2006;24:1679–1686. doi: 10.1002/jor.20230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith-Adaline EA, Volkman SK, Ignelzi MA, Jr, et al. Mechanical environment alters tissue formation patterns during fracture repair. J Orthop Res. 2004;22:1079–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park SH, Silva M. Effect of intermittent pneumatic soft-tissue compression on fracture-healing in an animal model. Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:1446–1453. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200308000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schell H, Epari DR, Kassi JP, et al. The course of bone healing is influenced by the initial shear fixation stability. J Orthop Res. 2005:1022–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gardner TN, Mishra S, Marks L. The role of osteogenic index, octahedral shear stress and dilatational stress in the ossification of a fracture callus. Med Eng Phys. 2004;26:493–501. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park SH, O'Connor K, McKellop H, et al. The influence of active shear or compressive motion on fracture-healing. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:868–878. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199806000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hannouche D, Petite H, Sedel L. Current trends in the enhancement of fracture healing. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:157–164. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.83b2.12106. [review] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamaji T, Ando K, Wolf S, et al. The effect of micromovement on callus formation. J Orthop Sci. 2001;6:571–575. doi: 10.1007/s007760100014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Claes LE, Heigele CA, Neidlinger-Wilke C, et al. Effects of mechanical factors on the fracture healing process. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;355:S132–S147. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199810001-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sarmiento A, McKellop HA, Llinas A, et al. Effect of loading and fracture motions on diaphyseal tibial fractures. J Orthop Res. 1996;14:80–84. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100140114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kenwright J, Richardson JB, Cunningham JL, et al. Axial movement and tibial fractures: A controlled randomized trial of treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73:654–659. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B4.2071654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kenwright J, Goodship AE. Controlled mechanical stimulation in the treatment of tibial fractures. Clin Orthop. 1989;241:36–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Molster AO, Gjerdet NR, Langeland N, et al. Controlled bending instability in the healing of diaphyseal osteotomies in the rat femur. J Orthop Res. 1987;5:29–35. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100050106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goodship AE, Cunningham JL, Kenwright J. Strain rate and timing of stimulation in mechanical modulation of fracture healing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;355:S105–S115. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199810001-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Woo SL, Lothringer KS, Akeson WH, et al. Less rigid internal fixation plates: historical perspectives and new concepts. J Orthop Res. 1984;1:431–449. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100010412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chao EY, Inoue N, Elias JJ, et al. Enhancement of fracture healing by mechanical and surgical intervention. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;355:S163–S178. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199810001-00018. [review] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Augat P, Merk J, Wilf S, et al. Mechanical stimulation by external application of cyclic tensile strains does not effectively enhance bone healing. J Orthop Trauma. 2001;15:54–60. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200101000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang P, Sun Q, Turner CH, et al. Knee loading accelerates closure of surgical wounds in mouse tibia. J Bone Miner Res. 2007 doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070803. [in press] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van der Eerden BC, Karperien M, Wit JM. Systemic and local regulation of the growth plate. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:782–801. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0033. [review] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kronenberg HM. Developmental regulation of the growth plate. Nature. 2003;423:332–336. doi: 10.1038/nature01657. [review] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stokes IA, Mente PL, Iatridis JC, et al. Enlargement of growth plate chondrocytes modulated by sustained mechanical loading. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:1842–1848. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200210000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ohashi N, Robling AG, Burr DB, et al. The effects of dynamic axial loading on the rat growth plate. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:284–292. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Parvizi J, Sharkey PF, Bissett GA, et al. Surgical treatment of limb-length discrepancy following total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:2310–2317. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200312000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stanitski DF. Limb-length inequality: assessment and treatment options. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1999;7:143–153. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199905000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Abbaspour A, Takata S, Matsui Y, et al. Continuous infusion of insulin-like growth factor-I into the epiphysis of the tibia. Int Orthop. 2007;13 doi: 10.1007/s00264-007-0336-7. [in press] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chestnut CH. Bone mass and exercise (review) Am J Med. 1993;95:34S–36S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90379-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Besier TF, Lloyd DG, Ackland TR, et al. Anticipatory effects on knee joint loading during running and cutting maneuvers. Med Sci Sports Exercise. 2001;33:1176–1181. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200107000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kerin AJ, Wisnom MR, Adams MA. The compressive strength of articular cartilage. Proc Inst Mech Eng (H) 1998;212:273–280. doi: 10.1243/0954411981534051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Su M, Jiang H, Zhang P, et al. Load-driven molecular transport in mouse femur with knee-loading modality. Ann Biomed Eng. 2006;34:1600–1606. doi: 10.1007/s10439-006-9171-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.