Abstract

Bacterial pathogenesis often depends on regulatory networks, two-component systems and small RNAs (sRNAs). In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the RetS sensor pathway downregulates expression of two sRNAs, rsmY and rsmZ. Consequently, biofilm and the Type Six Secretion System (T6SS) are repressed, whereas the Type III Secretion System (T3SS) is activated. We show that the HptB signalling pathway controls biofilm and T3SS, and fine-tunes P. aeruginosa pathogenesis. We demonstrate that RetS and HptB intersect at the GacA response regulator, which directly controls sRNAs production. Importantly, RetS controls both sRNAs, whereas HptB exclusively regulates rsmY expression. We reveal that HptB signalling is a complex regulatory cascade. This cascade involves a response regulator, with an output domain belonging to the phosphatase 2C family, and likely an anti-anti-σ factor. This reveals that the initial input in the Gac system comes from several signalling pathways, and the final output is adjusted by a differential control on rsmY and rsmZ. This is exemplified by the RetS-dependent but HptB-independent control on T6SS. We also demonstrate a redundant action of the two sRNAs on T3SS gene expression, while the impact on pel gene expression is additive. These features underpin a novel mechanism in the fine-tuned regulation of gene expression.

Introduction

In the course of infection, bacterial pathogens are subjected to changing conditions and stress to which they should respond by inducing or repressing virulence genes. Bacteria have evolved sensory systems, including two-component regulatory systems (TCSs). These systems involve a histidine kinase sensor protein, which detects environmental stimuli. Perception of an environmental cue by the sensor results in autophosphorylation and transfer of the phosphoryl group onto a cognate response regulator (RR), which most frequently binds DNA to control gene expression. In many cases, the activation of the RR by the sensor may transit through a Histidine phosphotransfer (Hpt) protein, which is acting as a phosphorylation relay. This is the case with LuxU, a Vibrio cholerae Hpt, which is targeted by three different kinases, CqsS, LuxN and LuxQ (Tu and Bassler, 2007). After transiting through LuxU, the phosphate is transferred onto a single RR, LuxO.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a Gram-negative bacterium that is responsible for numerous nosocomial infections. Genome mining revealed about 120 genes encoding histidine kinase sensors or RRs (Rodrigue et al., 2000). Moreover, only three genes encoding Hpt modules, namely hptA, hptB and hptC, were identified. In P. aeruginosa, some TCS pathways are involved in virulence or biofilm formation. The hybrid sensors RetS and LadS have been shown to be involved in the transition between chronic and acute infections by antagonistically controlling expression of genes involved in virulence, such as the type III secretion system (T3SS), or genes that are required for biofilm formation, such as those involved in polysaccharide synthesis (Goodman et al., 2004; Laskowski et al., 2004; Ventre et al., 2006). The two sensors appeared to intersect with another TCS formed by the GacS/GacA pair, in which GacS is an unorthodox sensor and GacA an RR. The GacS/GacA system was shown to be important for P. aeruginosa virulence and under defined conditions to regulate expression of the quorum sensing signal homoserine lactone C4-HSL (Reimmann et al., 1997; Rahme et al., 2000).

Recent progress in the understanding of regulatory mechanisms revealed that a quick and tight mode of regulation to modulate gene expression may involve small RNAs (sRNAs) (Romby et al., 2006; Toledo-Arana et al., 2007; Valverde and Haas, 2008). It was shown that RRs influence expression of sRNAs, which in turn promote or inhibit the translation of target mRNAs. Most sRNAs act using an antisense mechanism; however, some other sRNAs, such as CsrB and CsrC, display multiple GGA motifs, which are targets for a translational repressor, CsrA, in Escherichia coli and V. cholerae (Weilbacher et al., 2003; Lenz et al., 2005). The out-titration of CsrA by the sRNAs results in the expression of genes that are otherwise negatively controlled by this translational repressor and are required for virulence, biofilm formation and host interaction.

Two P. aeruginosa sRNAs are extremely well described, namely RsmY and RsmZ. These sRNAs act by titrating the RNA binding protein RsmA, which is a close homologue of the E. coli and V. cholerae CsrA. Just like CsrA, RsmA specifically binds to GGA motifs located in target mRNAs. RsmA negatively controls the expression of quorum sensing and several virulence factors (Pessi et al., 2001; Heurlier et al., 2004; Burrowes et al., 2006; Kay et al., 2006; Brencic and Lory, 2009). In particular, it was found to bind directly on transcripts encoding hydrogen cyanide synthesis components (Pessi et al., 2001) and more recently on transcripts encoding type VI secretion system (T6SS) components (Brencic and Lory, 2009). Importantly, in P. aeruginosa the production of RsmY and RsmZ is controlled by GacA (Kay et al., 2006; Brencic and Lory, 2009). We have previously shown that expression of rsmZ is positively controlled by the LadS pathway and negatively by the RetS pathway (Ventre et al., 2006). Overall, upregulation of rsmZ appears to promote bacterial biofilm formation and to prevent cytotoxicity.

LadS and RetS are hybrid sensors, and may require an Hpt module to transfer their phosphate onto a cognate RR. However, it was recently shown that RetS acts in a fairly unusual manner, by forming heterodimers with GacS and preventing the activation of the GacS/GacA pathway (Goodman et al., 2009). In this study, we observed that an hptB mutant displayed very similar phenotypes to a retS mutant. However, we present detailed evidence showing that despite these similarities, the HptB and RetS pathways are distinct. Although both pathways terminate on the GacA RR, HptB signalling controls expression of rsmY only, whereas RetS signalling modulates both rsmY and rsmZ gene expression. This subtle difference results in a significant difference in the control of target genes in the Gac/Rsm pathway.

Results

The hyperbiofilm phenotype of an hptB mutant is linked with the expression of pel genes

Preliminary studies by Hsu and colleagues suggested that an hptB mutant synthesizes and disintegrates biofilm at a higher rate as compared with the PAO1 wild-type strain (Lin et al., 2006; Hsu et al., 2008). Here, we engineered a deletion of the hptB gene (PA3345 at http://www.pseudomonas.com) in the P. aeruginosa PAK strain, yielding PAKΔhptB (Experimental procedures; Table S1). The biofilm phenotype was tested in microtitre dishes or glass tubes as previously described (Ventre et al., 2006). The hptB mutant has a hyperbiofilm phenotype compared with PAK (Fig. 1A), which was very similar to one previously reported for the PAKΔretS mutant (Goodman et al., 2004) (Fig. 1A). The hyperbiofilm phenotype in the retS mutant is linked to overproduction of exopolysaccharides, therefore we determined whether this was also the case with the hptB mutant. The retS and hptB mutants grown on plates containing Congo-Red dye displayed a strong staining, thus revealing polysaccharide production (Fig. 1B). The staining was stronger with the retS mutant when compared with the hptB mutant. Introduction of the hptB gene cloned in the pUCP18 plasmid (pUCPhptB), into the hptB mutant (PAKΔhptB), resulted in restoration of biofilm and polysaccharide production (Fig. 2), confirming that the phenotype is due to the hptB deletion.

Fig. 1.

Comparison between PAKΔhptB and PAKΔretS mutants for biofilm formation and exopolysaccharide production. A. Glass tube assay showing biofilm formation (upper part). Quantification of the crystal violet-stained adherence ring formed in the glass tube (lower part). Each experiment was repeated three times. The error bars indicate standard deviations. The name of the tested strain is indicated above each panel. B. Bacterial colony staining on Congo red-containing agar plates. The name of strains used is indicated under each panel.

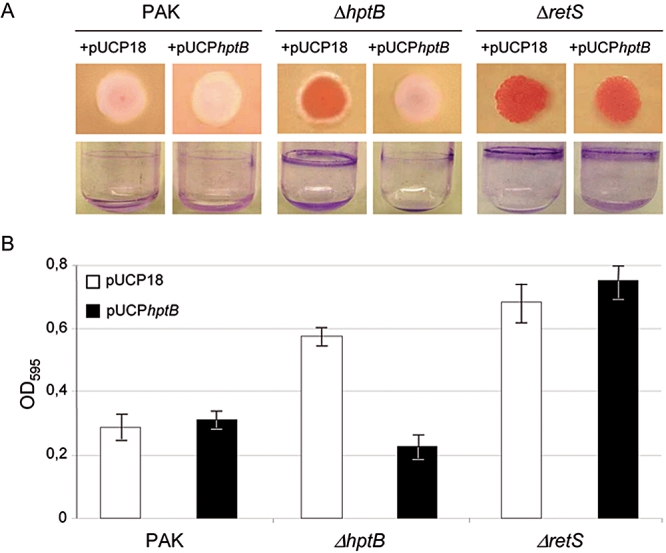

Fig. 2.

Influence of hptB overexpression in PAK, PAKΔhptB or PAKΔretS strains, on biofilm formation and exopolysaccharide production. A. Bacterial colony staining on Congo red-containing agar plates (upper row) and glass tube assay showing biofilm formation (lower row). The name of the tested strains is indicated above each panel. B. Quantification of the adherence ring formed in the glass tube. Each experiment was repeated three times. The error bars indicate standard deviations. The name of the strains used is indicated under each bar. Filled bars correspond to strains carrying pUCPhptB whereas open bars correspond to strains carrying pUCP18. The pUCPhptB allowed overexpression of the hptB gene cloned into the pUCP18 vector.

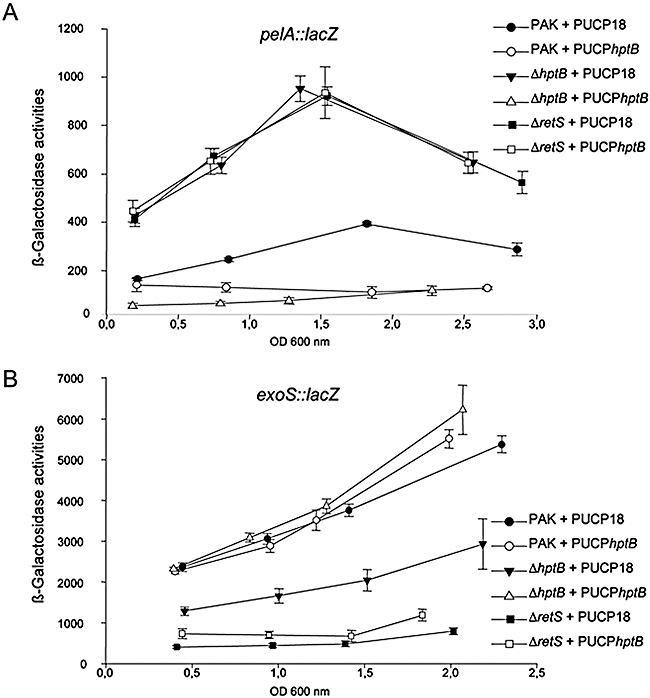

Congo red staining has previously been reported as being linked to overexpression of the pel genes (Friedman and Kolter, 2004; Vasseur et al., 2005). We introduced a pelA–lacZ transcriptional fusion carried on pMP220 into the PAK and PAKΔhptB strains (Ventre et al., 2006). The strains were grown in Luria broth (LB) at 37°C. The level of β-galactosidase activity measured at different growth stages revealed a higher activity of the pelA promoter in the hptB mutant in comparison to the parental PAK strain (Fig. 3A). The maximal induction of the pelA promoter was reached at an OD600 of 1.4. Expression level was increased by 2.9-fold in the hptB mutant as compared with PAK (Fig. 3A). Upon introduction of a plasmid carrying the hptB gene (pUCPhptB), expression of the pelA transcriptional fusion was strongly inhibited both in the parental and the hptB mutant (Fig. 3A). These observations clearly suggest that HptB signalling negatively controls pel gene expression. Finally, the causal link between the biofilm phenotype of the hptB mutant and the increased level in pel gene expression was established. Indeed, introduction of a pelB mutation in the hptB mutant abolished the hyperbiofilm phenotype and congo-red staining (Fig. S1; Experimental procedures; Table S1).

Fig. 3.

Expression of lacZ transcriptional fusion in PAK, PAKΔhptB or PAKΔretS strains. Activity was recorded at different growth stages. A. Activity of the pelA–lacZ transcriptional fusion. B. Activity of the exoS–lacZ transcriptional fusion (carried on pBS307). Open signs correspond to strains carrying pUCPhptB whereas filled signs correspond to strain carrying pUCP18. β-Galactosidase activities are expressed in Miller units. Values are averages of at least three independent experiments.

Overlap between the hptB and retS mutant transcriptomes

The phenotypic similarities observed between hptB and retS mutants led us to compare the transcriptome of these strains to reveal whether they have more target genes in common. We used P. aeruginosa microarrays that we engineered by spotting PCR products from around 4600 annotated orfs on the P. aeruginosa genome (Experimental procedures). The mRNAs were extracted from the PAK, PAKΔretS and PAKΔhptB strains grown in LB at 37°C in conditions that induce expression of the T3SS genes as previously described (Goodman et al., 2004; Experimental procedures). The cDNAs were synthesized and labelled using Cy3 or Cy5 (Experimental procedures). Gene expression levels in either PAKΔretS or PAKΔhptB mutants were directly compared with expression levels observed in the PAK strain (Table S2). Our data confirmed that the pel genes (pelA and pelB) were upregulated by about threefold in the PAKΔhptB mutant and by about fourfold in the PAKΔretS mutant (Table S2). One noticeable observation is that genes involved in T3SS are downregulated in the hptB mutant. The fold variation is from 2.3 (PA1697/pscN) to 7.4 (exoY). This is similar to that seen in the retS mutant, in which these genes have been previously shown to be downregulated (Goodman et al., 2004).

Our microarray analysis thus suggested that HptB positively controls expression of the T3SS genes. We confirmed this observation by introducing the plasmid pSB307, containing a transcriptional exoS–lacZ fusion (Bleves et al., 2005) into the PAK strain and the PAKΔhptB mutant. Strains were grown in conditions that induce T3SS gene expression and β-galactosidase activity was measured at different growth stages. At all time points tested we observed downregulation of the reporter gene fusion by twofold in the hptB mutant as compared with PAK (Fig. 3B). It should be noticed that in the retS mutant the downregulation of the exoS–lacZ fusion is more pronounced (sevenfold) (Fig. 3B). By introducing the hptB gene in trans (pUCPhptB), wild-type expression levels could be readily restored in the hptB mutant (Fig. 3B). Our data confirmed that HptB, like RetS, positively regulates most of the T3SS genes.

Overall, we identified 19 genes whose expression varies significantly in the hptB mutant (Table S2) and all of them appeared to be also affected in the retS mutant (Table S2). It should be noted that the identity of the 127 genes whose expression varies in the retS mutant is consistent with previously published data (Goodman et al., 2004; Table S2). However, the transcription profiles of the retS and hptB mutants are not identical. Indeed, the entire HptB regulon is part of the RetS regulon, whereas the RetS regulon includes many genes that are not controlled by the HptB pathway. In particular, expression of the type VI secretion (T6SS) genes (Mougous et al., 2006; Filloux et al., 2008), which is significantly upregulated in the retS mutant (PA0078, PA0083-PA0087 and PA0089; Table S2), is not affected in the hptB mutant. We further checked that the T6SS-associated protein VgrG1 (PA0091) was not overproduced in the hptB mutant. Western blot analysis using antibodies directed against VgrG1 revealed that whereas it is produced in the retS mutant, it is hardly detectable either in the PAK strain or in the hptB mutant (Fig. S2). In conclusion, our analysis revealed that the HptB and RetS signalling pathways influence expression of a subset of common genes but are not fully overlapping.

HptB overproduction does not compensate for the retS mutation

By using phenotypic assays, transcriptional fusions and transcriptome profiling, we have shown that at least two targets were common to RetS and HptB signalling pathways, the pel and T3SS genes. Because RetS is a hybrid sensor, HptB could have been the phosphorylation relay allowing activation of the RetS cognate RR. We investigated whether overproduction of HptB could restore a wild-type expression level for pel and exoS genes in a retS mutant. We tested the expression of the pelA–lacZ (Fig. 3A) and exoS–lacZ (Fig. 3B) transcriptional fusions as described earlier and noticed no variation in the level of β-galactosidase activity when comparing the retS mutant with the retS mutant overexpressing hptB (pUCPhptB). Failure of HptB overproduction to restore expression of pel and exoS genes in the retS strain was further confirmed using biofilm and Congo red assays (Fig. 2). However, overexpression of the hptB gene in an hptB mutant readily restored wild-type activity of the transcriptional fusions (Fig. 3A and B). Overall, these observations are not in favour of HptB being a cognate partner for RetS.

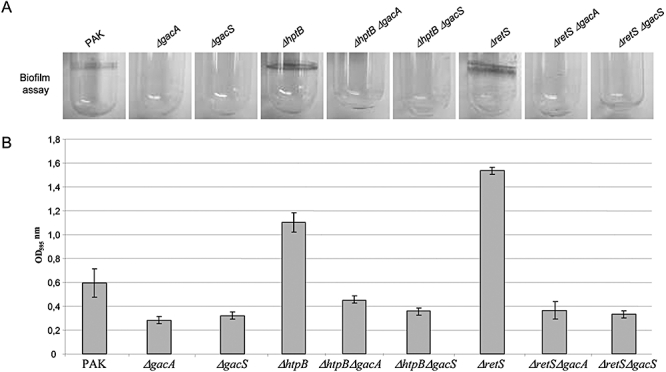

HptB control is GacS/GacA-dependent

Our microarray analysis shows that all HptB target genes are also controlled by the RetS pathway. In a previous study (Goodman et al., 2004), it was shown that suppressor mutations of the retS phenotype could be found in genes involved in the GacS/GacA signalling pathway, suggesting that this pathway is required for the action of RetS on downstream target genes. We tested whether the HptB signalling pathway, like the RetS pathway, converges onto the GacS/GacA system. We speculated that if the HptB pathway was dependent on the Gac system, a gacS or gacA mutation should suppress the phenotype of an hptB mutant. Therefore, we engineered a gacS or gacA deletion into the PAKΔhptB and PAKΔretS strains (Experimental procedures). We compared the biofilm phenotypes of these strains with the PAK strain and the single hptB or retS mutant (Fig. 4). Whereas the hptB and retS mutants displayed a thicker crystal violet-stained ring in the microtitre plate assay compared with the wild-type (Fig. 4), the phenotype was abolished upon introduction of the gacS or gacA mutation in both the hptB and the retS mutants. We performed similar phenotypic observation using the Congo red staining assay (data not shown). Thus, the hptB mutation is suppressed by a secondary mutation in gacS or gacA, suggesting that HptB acts upstream of the Gac pathway or at the same level.

Fig. 4.

Effect of the gacS and gacA mutations on biofilm formation. The gacS or gacA mutation was introduced in PAK, PAKΔhptB and PAKΔretS. A. Glass tube assay showing biofilm formation. The name of the strain is indicated above each panel. B. Quantification of the crystal violet-stained adherence ring formed in the glass tube. Each experiment was repeated three times. The error bars indicate standard deviations. The name of strains used is indicated under each bar.

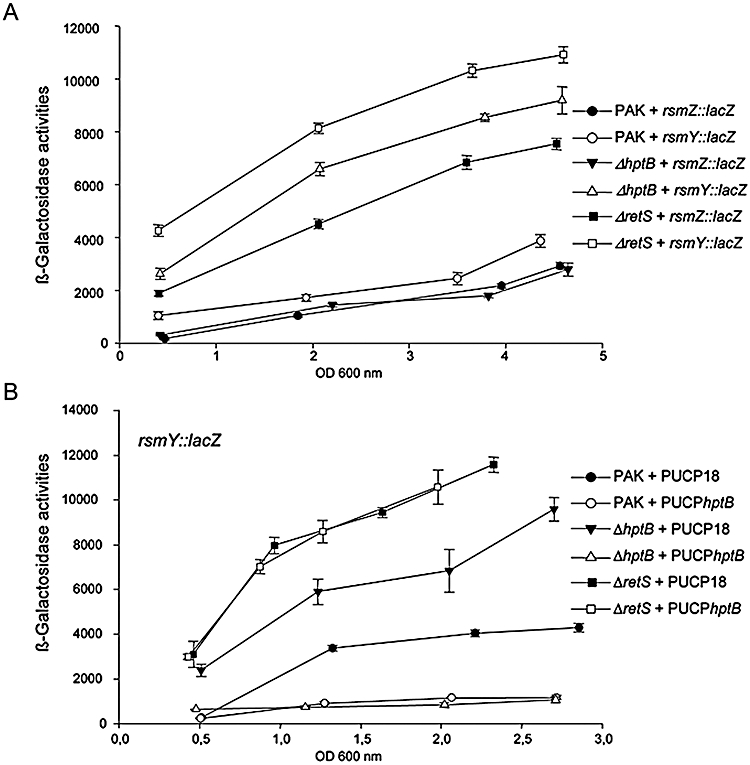

HptB controls rsmY but not rsmZ gene expression

In previous studies, it was shown that the Gac pathway acts mainly through the modulation of sRNAs levels, namely RsmY and RsmZ (Kay et al., 2006; Brencic et al., 2009). We investigated the impact of HptB on rsmY and rsmZ regulation, and compared these results with the impact of RetS. We engineered rsmY–lacZ and rsmZ–lacZ transcriptional fusions (Experimental procedures), and in both cases we observed higher levels of β-galactosidase activities in the PAKΔretS mutant as compared with PAK (3.8- to 4-fold) (Fig. 5A). The rsmY–lacZ fusion was also upregulated in the hptB mutant (Fig. 5A), but we could observe no effect of the hptB mutation on the expression of the rsmZ–lacZ transcriptional fusion (Fig. 5A). Importantly, introduction of hptB in trans in the hptB mutant abolished rsmY expression, whereas it had no effect when introduced into the retS mutant (Fig. 5B). We thus showed that RetS and HptB are independent signalling pathways, which act differently on the expression of the two small RNA-encoding genes, rsmZ and rsmY. This is a crucial observation, which reveals that the regulation of these sRNAs is partly different. We also observed that introduction of a rsmY mutation in the hptB mutant (Experimental procedures) suppresses the hyperbiofilm phenotype (Fig. 6) and confirmed that in this background the phenotype relies exclusively on RsmY but not on RsmZ. This is also clearly visible when looking at the phenotype of the hptB/rsmY mutant on Congo red-containing plates (Fig. 6). Instead, when the rsmY mutation is introduced in the retS mutant (Fig. 6), the hyperbiofilm phenotype is unaltered, suggesting that RsmZ could substitute for RsmY. Finally, only the simultaneous deletion of both sRNA genes is able to suppress retS phenotypes.

Fig. 5.

Expression of the rsmY and rsmZ genes in various P. aeruginosa strains. A. Activity of the rsmY–lacZ (open signs) and rsmZ–lacZ (filled signs) transcriptional fusion in PAK, PAKΔhptB or PAKΔretS strains was recorded at different growth stages. B. Activity of the rsmY–lacZ transcriptional fusions in PAK, PAKΔhptB or PAKΔretS strains, carrying pUCP18 (filled signs) or pUCPhptB (open signs), was recorded at different growth stages. β-Galactosidase activities are expressed in Miller units. Values are averages of at least three independent experiments.

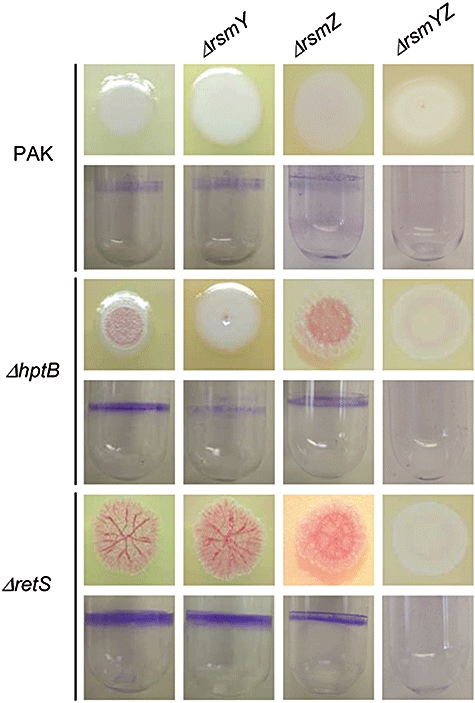

Fig. 6.

Influence of the rsmY and rsmZ mutations in PAK, PAKΔhptB and PAKΔretS strains for biofilm formation and exopolysaccharide production. For each row the name of the corresponding strain is indicated on the left. For each strain the upper row corresponds to the bacterial colony staining on Congo red-containing agar plates and the lower row to the glass tube assay showing biofilm formation. In each strain additional mutations in rsmY, rsmZ or rsmY/rsmZ have been introduced as indicated at the top of each column.

RsmY and RsmZ contribution to the HptB or RetS signalling pathway

We have shown that RsmY is essential in the HptB signalling pathway, whereas in the RetS pathway either RsmY or RsmZ could be sufficient for proper signalling. In order to investigate this in more detail, we systematically engineered rsmY, rsmZ and rsmY/rsmZ deletion mutants in the PAK parental strain and the hptB and retS background. As expected the rsmZ mutation has no impact on Congo-Red staining or hyperbiofilm phenotypes when introduced in the hptB mutant (Fig. 6). Interestingly, when the rsmZ mutation was introduced in the retS genetic background, the Congo-Red and hyperbiofilm phenotypes were only slightly affected and were resembling the phenotypes of an hptB mutant. This observation makes sense, knowing that an hptB mutant overproduces RsmY but not RsmZ (Fig. 5). Finally, when a double mutation rsmY/rsmZ was introduced in hptB or the retS mutants the phenotypes observed for Congo-Red staining and biofilm were similar to the phenotype of strains, which do not overproduce any of the sRNAs (gacA mutant for example).

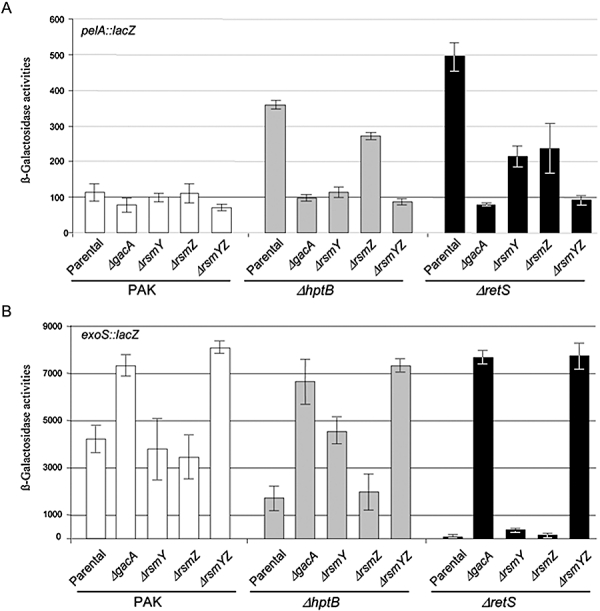

We looked in more detail at the impact of these different mutations by analysing the expression of two transcriptional fusions, pelA–lacZ and exoS–lacZ, which are upregulated or downregulated, respectively, in an hptB or retS genetic background (Fig. 7A). Regarding the pelA–lacZ fusion, it is important to point out first that the influence of HptB on the expression of the transcriptional fusion is mostly RsmY-dependent. Indeed, introduction of the rsmY mutation in the hptB mutant drastically affects pelA–lacZ expression, whereas introduction of the rsmZ mutation has only little effect (Fig. 7A). In contrast, upon introduction of the rsmY or rsmZ mutation in the retS genetic background, the expression of the fusion is reduced by about twofold (Fig. 7A). Only when both mutations were introduced simultaneously was the level of pelA–lacZ transcription abolished and returned to the level observed in the PAK wild-type strain (Fig. 7A). This observation suggests that the control exerted by RsmY and RsmZ on pelA gene transcription is somehow additive. When analysing the fate of the exoS–lacZ transcriptional fusion in a retS background, we observed that either an rsmY or rsmZ mutation was not sufficient to allow expression of the fusion (Fig. 7B). Only introduction of both rsmY and rsmZ mutations into the retS background resulted in induction of the exoS–lacZ transcriptional fusion (Fig. 7B). This observation suggests that the control exerted by RsmY and RsmZ on exoS gene transcription is redundant and that deletion of either one of them in the retS background is sufficient to repress exoS expression. It is also important to note that the effect of the double mutation rsmY/rsmZ in the retS or hptB genetic background resulted in transcriptional levels of pel–lacZ and exoS–lacZ fusions similar to those observed in a gacA mutant (Fig. 7). This is good in agreement with the fact that GacA is the only known positive regulator for the expression of the sRNAs in P. aeruginosa (Brencic et al., 2009).

Fig. 7.

Expression of lacZ transcriptional fusion in PAK, PAKΔhptB or PAKΔretS strains. Activity was recorded after 4 h growth. A. Activity of the pelA–lacZ transcriptional fusion. B. Activity of the exoS–lacZ transcriptional fusion (carried on pSB307). White bars correspond to PAK, grey bars to PAKΔhptB and black bars to PAKΔretS. Each additional mutation, i.e. gacA, rsmY, rsmZ or rsmYZ, which was introduced in each of these strains, is indicated under the corresponding bar. β-Galactosidase activities are expressed in Miller units. Values are averages of at least three independent experiments.

We also analysed, in these various genetic backgrounds, the level of production of the T6SS component VgrG1. We observed, using immunobloting and anti VgrG1, that, as expected from our microarray data, there is no induction of VgrG1 in the hptB mutant whereas high levels of VgrG1 are seen in the retS mutant. Upon introduction of the rsmY mutation in the retS mutant, the level of VgrG1 is slightly decreased (Fig. S2). However, when the rsmZ mutation is introduced in the retS mutant the level of VgrG1 is much more severely decreased. This observation makes sense since a retS/rsmZ mutant is likely to have a phenotype that is similar to the phenotype of an hptB mutant, which is what we observed (Fig. S2). Finally, when both rsmY and rsmZ are deleted in the retS mutant, the production of VgrG1 is abolished (Fig. S2).

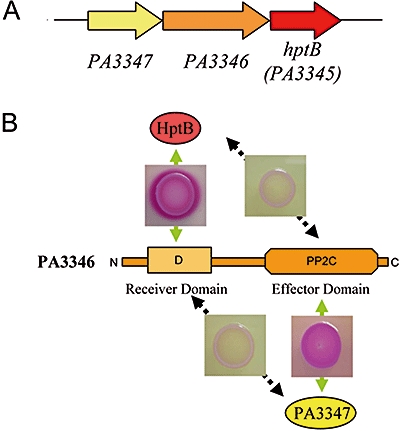

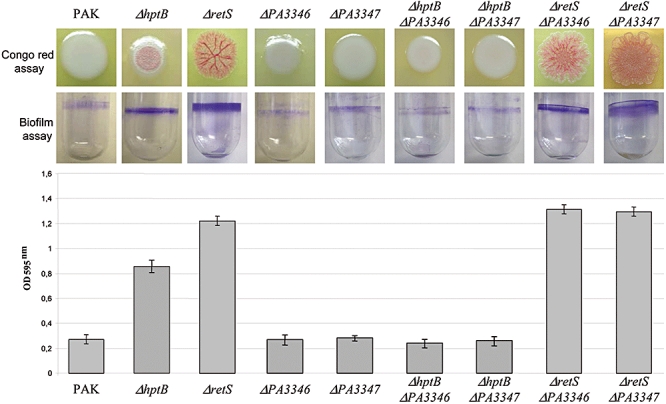

HptB acts through the PA3346/PA3347 regulatory components

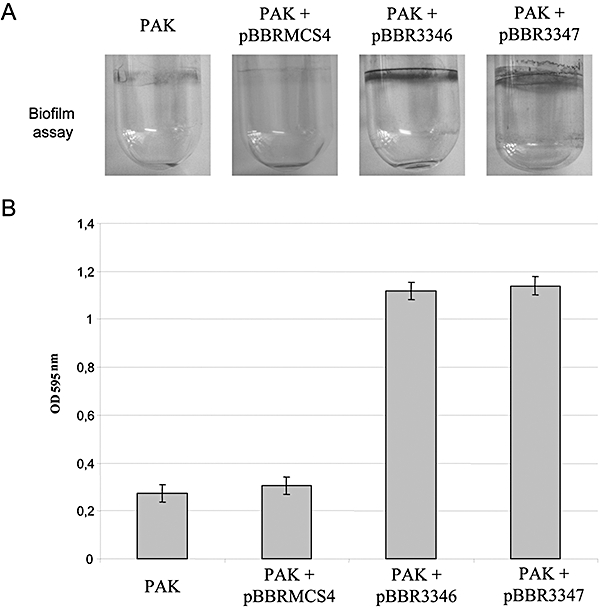

The hptB gene is annotated as PA3345, and was shown to be organized as an operon together with the PA3346 and PA3347 genes (Hsu et al. 2008 and Fig. 8A). It was previously suggested that HptB interacts with the PA3346 gene product (Hsu et al., 2008). This gene encodes an RR with an N-terminal phosphoryl-receiver domain and a C-terminal output domain belonging to the phosphatase 2C (PP2C) family (Delumeau et al., 2004). By using a two-hybrid system (Experimental procedures), we demonstrated that HptB directly interacts with the receiver domain of the PA3346 RR, but not with the PP2C domain (Fig. 8B). Furthermore, we showed by using the two-hybrid technique that the PP2C domain of the PA3346 gene product, and not the receiver domain, interacts with the PA3347 gene product, which encodes a putative anti-anti-σ factor (Fig. 8B). Since HptB, PA3346 and PA3347 appeared to belong to the same regulatory cascade, we analysed whether PA3346 and PA3347 deletion mutants (Experimental procedures and Table S1) displayed an hptB mutant phenotypes. Interestingly, neither the PA3346 nor the PA3347 mutant showed a hyper biofilm phenotype or increased staining on Congo red plates (Fig. 9). However, when a PA3346 or PA3347 mutation was introduced in the hptB mutant background, the hptB mutant phenotype readily disappeared (Fig. 9). In particular, these strains did not display the hyperbiofilm phenotype of the hptB mutant and behave like the PAK wild-type strain (Fig. 9). This is strongly suggesting that PA3346 and PA3347 are located downstream of HptB in the HptB signalling pathway. Moreover, when a PA3346 or PA3347 mutation was introduced in the retS mutant background, no changes in the retS phenotype were observed, suggesting that PA3346 and PA3347 are part of the HptB signalling pathway but do not intersect with the RetS signalling pathway (Fig. 9). We then tested the impact of PA3346 and PA3347 overexpression. Both genes were cloned in the pBBRMCS4 vector (Experimental procedures and Table S1) and the resulting recombinant plasmids (pBBR3346 and pBBR3347) were introduced in the parental PAK strain. Overexpression of either PA3346 or PA3347 (Fig. 10) readily increased the level of biofilm formed by the PAK strain. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the gene targets whose expression is affected in the hptB mutant are similarly affected upon overexpression of PA3346 or PA3347. Indeed, the pelA–lacZ transcriptional fusion is upregulated (Fig. S3A) in the PAK strain containing either pBBR3346 and pBBR3347, while the exoS–lacZ fusion is downregulated in these same strains (Fig. S3B). This observation suggested that HptB antagonizes the activity of the couple PA3346/PA3347.

Fig. 8.

Interaction between HptB, PA3346 andPA3347. A. PA3345 encodes Hpt and is clustered with PA3346 and PA3347 genes. B. Two-hybrid experiment showing interaction between HptB and the receiver domain of PA3346 and between the PP2C domain of PA3346 and PA3347 (shown with the insert and the red-stained colonies on Mc Conkey agar plates). Interaction between HptB and the PP2C domain of PA3346 or between the receiver domain of PA3346 and PA3347 are negative (shown with the insert and the white colonies on Mc Conkey agar plates). The N- and C-termini for PA3346 have been indicated.

Fig. 9.

Influence of the PA3346 and PA3347 mutations in PAK, PAKΔhptB and PAKΔretS strains for biofilm formation and exopolysaccharide production (Congo red assay). For each column the name of the corresponding strain is indicated. For each strain the upper row corresponds to the bacterial colony staining on Congo red-containing agar plates, the middle row to the glass tube assay showing biofilm formation and the bottom row to the quantification of crystal violet staining as seen in the middle row.

Fig. 10.

Effect of the overexpression of PA3346 (pBBR3346) and PA3347 (pBBR3347) on biofilm formation. The cloning vextor (pBBRMCS4) and the appropriate recombinant plasmids were introduced in PAK. A. Glass tube assay showing biofilm formation. The name of the strain is indicated above each panel. B. Quantification of the crystal violet-stained adherence ring formed in the glass tube. Each experiment was repeated three times. The error bars indicate standard deviations. The name of strains used is indicated under each bar.

PA3346/PA3347 control is GacS/GacA-dependent

We have shown previously that the HptB control is Gac-dependent. We thus checked whether PA3346/PA3347 activity is also dependent on a fully functional Gac system. The PA3346- and PA3347-containing plasmids were introduced in the gacS and gacA mutants and phenotypes were analysed. These two strains completely lost their ability to form hyperbiofilm (Fig. S4 and data not shown). Furthermore, the impact on pelA–lacZ or exoS–lacZ expression was totally abolished (Fig. S3A and B). Finally, since we have shown that the HptB signalling influences rsmY but not rsmZ gene expression, we assessed the impact of PA3346 and PA337 overproduction on RsmY and RsmZ levels. Whereas introduction of the pBBR3346 or pBBR3347 recombinant plasmids in the rsmY–lacZ-containing PAK strain resulted in high level of β-galactosidase activity (Fig. S5 and data not shown), no effect was observed when using the rsmZ–lacZ-containing strain (Fig. S5 and data not shown). These observations confirmed that PA3346 and PA3347 belong to the HptB signalling pathway.

Discussion

The regulatory networks resulting in the production of virulence determinants by bacterial pathogens are increasingly complex. In P. aeruginosa, several regulatory devices including quorum sensing (Smith and Iglewski, 2003; Bleves et al., 2005), TCSs (Rodrigue et al., 2000) and chemotaxis (Garvis et al., 2009) have been involved in the chain of command determining the bacterial pathogenesis strategy.

Previous studies have depicted one such network involving the two-hybrid sensors, LadS and RetS, which antagonistically control biofilm formation and T3SS (Goodman et al., 2004; Ventre et al., 2006). Another study by Hsu and colleagues suggested that the HptB phosphorelay might be associated with RetS (Hsu et al., 2008). In the present study, we showed that the hptB and the retS mutants are hyperbiofilm formers and that in both cases the hyperbiofilm phenotype is linked to overexpression of the pel genes. We also showed that, as for a retS mutant, T3SS genes are downregulated in the hptB mutant. From this perspective, it seems that RetS and HptB signalling pathways share target genes and may be part of the same signalling pathway.

However, we collected information that suggests that RetS and HptB are not cognate partners. One observation is that the biofilm formed by the hptB mutant, even though thicker as compared with the parental PAK strain, is not as thick as the retS mutant biofilm (Fig. 1B and Fig. 6). Furthermore, microarray analysis revealed that only a subset of the RetS target genes are HptB targets. For example, the T6SS genes (Mougous et al., 2006; Filloux et al., 2008) are upregulated in the retS mutant, but remained unaffected in the hptB mutant. Finally, RetS forms heterodimers with GacS, inhibits GacS autophoshorylation and prevents activation of the GacA RR (Goodman et al., 2009). It was also shown that RetS phosphorelay domains are not required for its function, suggesting that RetS is not likely to act through a phosphorelay such as HptB, but rather exclusively through GacS heterodimerization (Goodman et al., 2009).

In response to GacS, GacA controls levels of sRNA, which in turn relieve translational repression by the RsmA protein on several mRNAs (Pessi et al., 2001; Brencic and Lory, 2009). In P. aeruginosa, RsmA could be out-titrated by high levels of the sRNAs, RsmY and RsmZ (Kay et al., 2006; Brencic et al., 2009). The GacS/GacA regulation is most exclusively exerted through the transcriptional control of rsmY and rsmZ genes expression (Brencic et al., 2009), although sRNAs may exist that are regulated by GacA in an indirect manner (Livny et al., 2006; González et al., 2008).

In our study we confirmed that RetS negatively controls rsmY and rsmZ gene expression, in a GacA-dependent manner. We analysed whether HptB constitutes another branch of the Gac/Rsm signalling pathway. We hypothesized that if GacA is located downstream of HptB in the signalling cascade, the lack of GacA in the hptB mutant should abolish the hyperbiofilm phenotype induced by the hptB mutation, which is what we observed (Fig. 4). We also showed that the hptB phenotype could be suppressed by a mutation in gacS, suggesting that as for RetS the control by HptB on the target genes is likely to be indirect and should at some stage go through GacS/GacA or at least required this system as co-activator.

As part of the Gac signalling pathway it should be expected that HptB controls expression of the rsmZ and rsmY genes, since GacA is known to bind directly to the promoter regions of rsmY and rsmZ. However, in the hptB mutant, we found that in contrast to the retS mutant, only the rsmY–lacZ fusion is upregulated. These are clear evidence that regulation of rsmZ and rsmY is different with rsmY expression controlled by both RetS and HptB, whereas rsmZ is exclusively controlled by RetS. One possible explanation for this original observation is that additional regulatory components are involved in rsmY and rsmZ gene expression. It is reported that both regions upstream of the rsmY and rsmZ promoters contain a GacA binding site (Kay et al., 2006; Brencic et al., 2009). However, these regions also display clear differences in length and structure. For example, it was recently shown that two members of the H-NS family of global regulators, MvaT and MvaU, could bind the rsmZ but not the rsmY promoter (Brencic et al., 2009).

In addition to the observation that sRNAs control is significantly different depending on whether it is operated from the RetS or HptB signalling pathway, we also observed that RsmY and RsmZ exert their effect on target genes either in an additive or redundant/compensatory manner. This was quite surprising since in the case of the P. aeruginosa RsmY and RsmZ, it was admitted that, as with the RsmY/RsmZ/RsmX of P. fluorescens (Kay et al., 2005), the sRNAs are functionally redundant.

The functional redundancy of sRNAs may, however, be a matter of debate. For example, in V. cholerae the four sRNAs, Qrr1–4, are functionally redundant and all four sRNAs must be deleted to see an effect on hapR mRNA stability (Lenz et al., 2004). This phenomenon was described as a gene dosage compensation mechanism, since a deletion in one of the qrr genes could be compensated for by an increase in the levels of remaining Qrrs (Svenningsen et al., 2009). By contrast, in Vibrio harveyi the five homologous Qrrs are not redundant, but act additively to translate signal into a precise gradient of LuxR (HapR homologue) (Tu and Bassler, 2007). In conclusion, in V. cholerae, expression of only one of the four sRNAs will be sufficient to target all hapR mRNA present within the cell, whereas in V. harveyi, in order to reach sufficient concentration of sRNAs and destabilize all luxR mRNA, all Qrrs should be expressed.

In the present study, we observed that the additive and redundant mechanisms seen in V. harveyi and V. cholerae, respectively, are combined in P. aeruginosa. In the case of pel gene expression, whose expression is high in a retS background, we noticed an obvious reduction in expression if an additional gacA mutation or a double rsmY/rsmZ mutation is introduced (Fig. 7). However, if only the rsmY or rsmZ mutation is introduced, in both cases the level of expression is only decreased by half. The impact of the rsm mutations is additive since only the double rsmY/rsmZ mutant mimics the phenotype of a gacA mutant. In the case of the exoS gene (representative for T3SS genes), we observed that expression is quasi null in the retS background, but dramatically relieved when the gacA mutation or the double rsmY/rsmZ mutation was further introduced. However, in this case, a single mutation in either rsmY or rsmZ had no impact on exoS, whose expression remains totally repressed as it is in the retS mutant (Fig. 7). Thus for exoS gene expression, in contrast to pel genes, the impact of sRNAs is redundant.

In summary, we have shown in this work that the phosphorelay involving HptB plays a specific role in exclusively controlling expression of the rsmY gene, providing further knowledge on the regulatory and signalling networks that control P. aeruginosa virulence and biofilm formation. This control is dependent on GacS/GacA, which normally acts both on rsmY and rsmZ expression. GacA is located at the end of a complex network of signalling pathways, which involve GacS, LadS, RetS and HptB. We suggest that HptB and RetS are two distinct signalling pathways both intersecting with the GacS/GacA system but through different mechanisms. Whereas RetS interferes directly with GacS autophosphorylation (Goodman et al., 2009), the pathway leading from HptB to the regulation of rsmY via the Gac pathway is still not clearly established.

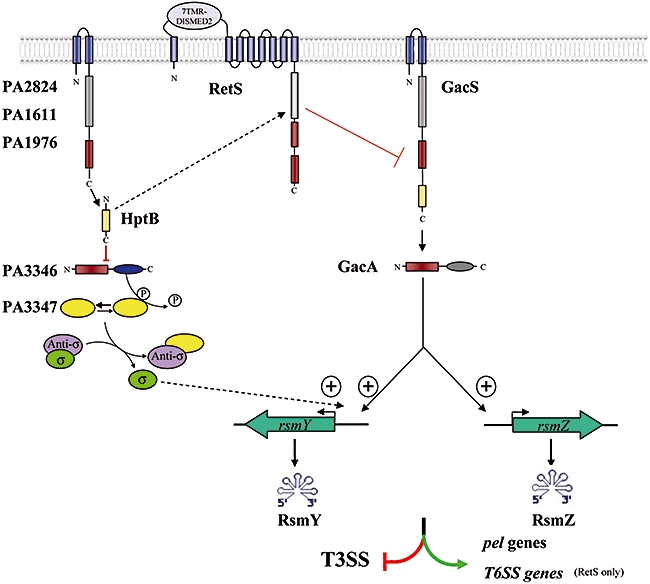

The novel HptB pathway might involve intermediate components such as the PA3346/PA3347 proteins (Hsu et al., 2008). In this study, we confirmed that HptB interacts with PA3346 using the two-hybrid system. PA3346 was proposed to encode an RR with a phosphatase 2C domain (PP2C) as output domain (Hsu et al., 2008). Hsu and collaborators showed that PA3346 could dephosphorylate PA3347, which encodes a protein with similarity to anti-anti-σ factor (Hsu et al., 2008). We showed that the PP2C domain of PA3346 is able to interact with PA3347 using the two-hybrid system. The PA3346/PA3347 cascade could resemble the RsbU/RsbV cascade in Bacillus subtilis (Delumeau et al., 2004), in which dephosphorylation of the anti-anti-σ factor RsbV by the phosphatase RsbU resulted in the capture of the anti-σ factor RsbW by RsbV and the release of the σB factor. Finally, we showed that, as for HptB, the activity of PA3346/PA3347 impacts rsmY but not rsmZ gene expression (Fig. S5). A putative model summarizing these features is presented in Fig. 11.

Fig. 11.

Model for the HptB regulatory network. HptB has a negative impact on PA3346 activity. In the absence of HptB, PA3346 dephosphorylates the putative anti-anti-σ factor PA3347 (yellow) through the activity of its PP2C domain (in blue). Dephosphorylated PA3347 could bind a putative anti-σ factor (purple), which allows the release of a yet uncharacterized σ factor (green). This σ factor may have a specific impact on rsmY gene expression, but not on rsmZ gene expression. The controlled expression of rsmY through the HptB/PA3346/PA3347 cascade is still GacA-dependent, suggesting GacA synergistically acts on the rsmY promoter together with the unknown σ factor. Overproduction of RsmY alone (through the PA3346/PA3347 pathway) results in overexpression of pel genes and repression of T3SS genes but not in overexpression of the T6SS genes, which are specifically controlled through the RetS pathway. The rest of the model integrates previous published data. The activity of RsmY and RsmZ is through RsmA titration, which is not represented in the figure. The RetS control through interference with the GacS activity was previously published (Goodman et al., 2009). The potential role of three hybrid sensors, PA2824, PA1611 or PA1976 on HptB activation and the retro-transfer of phosphate from HptB onto RetS comes also from previously published data (Hsu et al., 2008).

The way HptB influences differentially the activity of the rsmY and rsmZ promoters is a first level of complexity that still needs to be understood. The most likely explanation is that the rsmY promoter may contain a putative binding site for the unknown σ factor, which is released when the HptB pathway is activated, whereas the rsmZ promoter does not contain this alternative σ factor-binding site. Another level of complexity is given by a non-uniform control (additive or redundant) of the sRNAs, RsmY and RsmZ, on different target genes, although both sRNAs function by titrating RsmA. Here, the subtle relative stoichiometry between sRNAs, RsmA and target mRNAs is likely to be a key to understand this mechanism and might involve complex regulatory loops, as those proposed in the case of V. cholerae and V. harveyi sRNAs control (Svenningsen et al., 2008; Tu et al., 2008).

It seems clear now that the role of sRNAs is central to allowing for a quick and subtle bacterial response and adaptation to fast and tiny changes in environmental conditions. The complexity and connectivity of the regulatory circuits involved are yet far to be understood and we are pursuing the reconstruction of these networks by using systematic genetic screens, two-hybrid and in vitro phosphorylation assays to identify cognate partners and cross-talk between these different signalling pathways. We are currently working on the HptB signalling pathway and aim to identify all the components lying between HptB and the rsmY gene. In particular, we will try to identify the putative σ factor within the cascade involving the PA3347 anti-anti-σ factor.

Experimental procedures

Bacterial strains, plasmids and growth conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids are described in Table S1. The nucleotide sequence of oligonucleotides used is given in Table S3. For engineering the hptB deletion mutant, the upstream and downstream sequences (approximately 500 bp) were amplified from PAK genomic DNA using the pair of primers BupA/BloA and BupB/BloB respectively. The PCR products were digested with EcoRI and cloned in tandem into pCR2.1. The linked DNA fragment was digested with XbaI and SpeI and cloned in suicide vector pKNG101, yielding pKNGΔhptB. The suicide plasmid was introduced in PAK and deletion on the chromosome selected as previously described (Kaniga et al., 1991). For engineering the gacS, gacA, rsmY, rsmZ, PA3346 and PA3347 deletion mutants, the upstream and downstream regions (650 bp) of each gene were amplified from PAK genomic DNA using a specific couple of primers. PCR products were digested by BamHI and EcoRI for the upstream fragment and EcoRI and SpeI for the downstream fragment. Construction of suicide vector and allelic replacement is as above. The hptB/gacA, hptB/gacS, hptB/rsmY, hptB/rsmZ, retS/gacA, retS/gacS, retS/rsmY and retS/rsmZ double mutants were constructed by introducing the gacS, gacA, rsmY and rsmZ gene deletion in the PAKΔhptB and PAKΔretS strains. The hptB/rsmYZ and retS/rsmYZ triple mutants were constructed by introducing the rsmZ gene deletion in the PAKΔhptB/ΔrsmY and PAKΔretS/ΔrsmY strains. The hptB/pelB double mutant was constructed by using the pKNGmamb3063 suicide vector (Vasseur et al., 2005) in order to delete the pelB gene in the PAKΔhptB strain.

The hptB gene was amplified by PCR from PAK genomic DNA using the primers Bup and Bdown. The PCR product was modified using a DNA blunting kit (Takara) and cloned into pUCP18, yielding pUCPhptB.

The PA3346 and PA3347 genes were amplified by PCR from PAK genomic DNA using the primers. The PCR products were digested by EcoRI and BamHI and cloned into pBBRMCS4, yielding, respectively, to pBBR3346 and pBBR3347. The hptB/PA3346, hptB/PA3347, retS/PA3346 and retS/PA3347 double mutants were constructed by introducing the PA3346 and PA3347 gene deletion in the PAKΔhptB and PAKΔretS strains.

The rsmZ and rsmY promoter regions were amplified from the PAK genome by using the oligonucleotides couple PrsmZ1/PrsmZ2 and PrsmY1/PrsmY2 respectively. The upstream primers PrsmZ1 and PrsmY1 contain an EcoRI site whereas the PrsmZ2 and PrsmY2 primers contain a KpnI site. The EcoRI/KpnI digested PCR products were cloned into pMP220 to yield rsmZ– and rsmY–lacZ transcriptional fusions.

Plasmids were introduced into P. aeruginosa by electroporation (Smith and Iglewski, 1989) or triparental mating using the conjugative properties of pRK2013 (Figurski and Helinski, 1979). The transformants were selected on Pseudomonas isolation agar. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations for E. coli: 50 µg ml−1 ampicillin, 50 µg ml−1 streptomycin, 15 µg ml−1 tetracycline. For P. aeruginosa, 500 µg ml−1 carbenicillin, 200 µg ml−1 tetracycline and 2000 µg ml−1 streptomycin were used. Bacteria were grown in LB or M63 minimal medium supplemented with 0.2% glucose, 1 mM MgCl2 and 0.5% casamino acids.

Adherence assays on inert surface

The P. aeruginosa adherence assay was performed in 24-wells polystyrene microtitre dishes (Vallet et al., 2001), or by inoculating glass tubes containing 1 ml of medium. Biofilm formation was visualized by using the crystal violet staining procedure and quantified after 5 h of incubation at 30°C (Vallet et al., 2001).

Pseudomonas aeruginosa microarrays

A total of 4620 PCR products corresponding to 83% of the P. aeruginosa PAO1 genome have been spotted on glass slides. Most of the PCR products were obtained by using the PAO1 gene collection (Labaer et al., 2004), which allows amplification of all genes by using a single couple of primers (L1R1/L2R2, Table S3), flanking each orf cloned in the Gateway vector used for constructing this library. The amplification of the different orfs was done on bacterial colonies or on plasmidic DNA purified using a NucleoSpinR Multi-96 Plus Plasmid kit (Macherey-Nagel). For some genes longer than 3700 bp or not available in the library, amplicons were obtained by using P. aeruginosa genomic DNA as matrix and using specific primers yielding DNA fragments of about 500 bp. That was the case for the genes annotated PA0041, PA0690, PA0994, PA0844, PA1868, PA2462, PA3724, PA4084 and PA4541. All PCR products were purified using a QIAquickTM 96-well PCR purification kit (QIAgen). Microarrays were printed at the DNA microarray production platform at Sophia-Antipolis (IPMC-CNRS) using a ChipWriter Proarrayer (Bio-Rad). Each PCR product was spotted 4 times on commercial UltraGAPSTM slides of 24 × 60 mm (Corning Incorporated, MA, USA). DNA binding to the GAPS-coated surface was enhanced by UV cross-linking. Before performing the hybridization, microarrays were pre-hybridized with a BSA solution in order to block the empty surface of the slide, which helps to decrease non-specific hybridization.

RNA isolation procedure

Overnight bacterial cultures were diluted in LB, containing 5 mM EGTA and 20 mM MgCl2, to 0.1 unit of OD600. The bacteria were grown under agitation at 37°C and were harvested during exponential phase (0.6 unit of OD600), by centrifugation at 4°C. The samples were quickly processed to prepare RNA using the ‘SV Total RNA Isolation System’ from Promega. The DNase I digestion step was carried out twice in order to diminish the quantity of contaminating DNA. The integrity of the RNA preparations was checked after electrophoresis on agarose gel. The absence of DNA contamination was verified by performing PCR reaction. The RNA was further used to prepare cDNA.

cDNA synthesis and hybridization

Probes were generated by using the ChipShot Direct Labeling and Clean-Up System kits (Promega). Briefly, 10 µg of RNA was first hybridized with hexameric primers. Then dNTPs (330 nM each) were added together with 1 mM of Cy3 or Cy5 (Amersham) and 200 units of ChipShot Reverse transcriptase. The mixture was incubated 2 h at 42°C and the reaction stopped by a 15 min incubation at 37°C with RNAse. Unincorporated nucleotides were removed by using the ChipShot Direct Labeling and Clean-Up System (Promega). Labelled Cy3 or Cy5 cDNA were dried by using a speedVac and resuspended in 50 µl of ‘Dig Easy’ solution (Roche). The labelled cDNA was denatured upon a 5 min incubation at 95°C and used for microarray hybridization, 16 h at 42°C in a hybridization oven. The arrays were washed as follows: 2 times with 2× SSPE buffer, 0.1% SDS warmed at 62°C, 1 time with 0.5× SSPE buffer and 1 time with 0.1× SSPE buffer. The arrays were dried and scanned for data acquisition.

Quantification and analysis of the microarrays

Data from scanned microarrays were acquired by using Genepix Pro 6 software (Molecular Devices). The data were subsequently processed by using Acuity software (Molecular Devices). All data were normalized by performing a Lowess regression and filtered to remove genes, which presented a weak expression in both conditions (signal noise ratio > 2). Two criteria (> threefold change and Student's t-test, P ≤ 0.05) were used to determine significant changes. Each microarray experiment was performed in triplicate with independent bacterial cultures.

Measurements of β-galactosidase activity

Strains carrying the lacZ transcriptional fusions were grown in LB with agitation at 37°C. The bacterial cells were collected by centrifugation at different growth times. The β-galactosidase activity was measured using the method of Miller (Sambrook et al., 1989). Experiments with strains carrying the exoS–lacZ fusion carried on pSB307 were performed similarly except that EGTA (5 mM) and MgCl2 (20 mM) were added in the growth medium in order to induce T3SS genes expression.

Congo red assay

Tryptone (10 g l−1) agar (1%) plates were supplemented with Congo red (40 µg ml−1) and Coomassie brilliant blue dyes (20 µg ml−1). Bacteria were inoculated on the surface of the plates with a toothpick and grown at 30°C. The colony morphology and staining were recorded after 2 days.

Production of polyclonal VgrG1 antibodies

A V5-hexahistidine (V5H6) tag was added to the C-terminus of VgrG1 according to the Gateway® technology and using the original entry clone from the PAO1 orf collection (Labaer et al., 2004) and the pET-Dest42 destination vector, to give the recombinant vector pETvgrG1. The resulting construct was transferred into E. coli BL21 (DE3). The recombinant protein was overproduced in 100 ml of LB broth supplemented with 1 mM IPTG during 3 h at 37°C. Bacteria collected by centrifugation were sonicated in 5 ml of cold 10 mM Tris/HCl pH 8.0 containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and disrupted by sonication. Lysed bacteria were centrifuged at 4000 g and insoluble fraction enriched in inclusion bodies containing VgrG1 were washed twice in the sonication buffer and solubilized in Urea 8 M. Lysates were centrifuged at 40 000 g, and soluble fraction containing recombinant VgrG1 was applied on His Trap Hp column for purification (GE healthcare). About 1.5 mg of protein was purified and immunization protocols were performed at Eurogentec. Two rabbits were inoculated with 200 mg of VgrG1 protein, followed by three boosters spaced by 15 days, 1 month and 2 months. After that period, rabbits were sacrificed, and sera were verified for their specificity to VgrG1.

Sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting

Bacterial cell pellets were resuspended in loading buffer (Laemmli, 1970). The samples were boiled and separated on SDS gels containing 10% acrylamide and blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. After 30 min of saturation in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) (0.1 M Tris, 0.1 M NaCl, pH 7.5), 0.05% Tween 20 and 5% skim milk, the membrane was incubated for 1 h with anti-VgrG1 diluted 1:500; washed three times with TBS-0.05% Tween 20; incubated for 45 min with anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies (Sigma) diluted 1:5000; washed three times with TBS-0.05% Tween 20; and then revealed with a Super Signal Chemiluminescence system (Pierce).

The bacterial two-hybrid assay

DNA fragments encoding protein domains of interest were cloned at the 3′ end of genes encoding the two fragments of adenylate cycles carried on the pKT25 and pUT18c as described by Karimova and colleagues (2000). The DNA regions encoding the HptB protein, the receiver domain or PCR of the PP2C domain of PA3346 and the PA3347 protein were amplified by using PAK genomic DNA. PCR product on HptB and of the PP2C domain of PA3346 were digested by XbaI and KpnI and cloned into pKT25, yielding, respectively, to pKT25-hptB and pKT25-PP2. PCR product on PA3347 and of the receiver domain of PA3346 domain were digested by XbaI and EcoRI and cloned into pUT18C, yielding, respectively, to pUT18C-3347 and pUT18C-3346D. An adenylate cyclase deficient E. coli strain, DHM1, was used to screen for positive interactions. DHM1 competent cells were transformed simultaneously with pKT25 and pUT18c derivatives and transformants were selected on agar plates supplemented with ampicillin (100 µg ml−1) and kanamycin (50 µg ml−1). Single colonies were patched on MacConkey medium (Difco) supplemented with IPTG (1 mM) and maltose (1%). Positive interactions were identified as red colonies after 24 h incubation at 30°C.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Lory and L. Brizuela for providing the PAO1 orf collection; P. Barbry, V. Magnone and G. Rios for support in spotting microarray; Y. Denis for support on microarray analysis; and H. Combe for careful reading of the manuscript. I.V. was supported by a Philipp Morris foundation grant, M.C.L by ANR grant 05-MIIM-040-01 and A.H. by the European network of excellence EuroPathoGenomics. C.B. is supported by CNRS funding, the French Cystic Fibrosis foundation (VLM) and ANR grant 05-MIIM-040-01. A.F. is supported by the Royal Society, the EST Marie Curie Grant No. MEST-CT-2005-020278 and MRC Grant No. G0800171/ID86344.

Supporting information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- Bleves S, Soscia C, Nogueira-Orlandi P, Lazdunski A, Filloux A. Quorum sensing negatively controls type III secretion regulon expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:3898–3902. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.11.3898-3902.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brencic A, Lory S. Determination of the regulon and identification of novel mRNA targets of Pseudomonas aeruginosa RsmA. Mol Microbiol. 2009;72:612–632. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06670.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brencic A, McFarland KA, McManus HR, Castang S, Mogno I, Dove SL, Lory S. The GacS/GacA signal transduction system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa acts exclusively through its control over the transcription of the RsmY and RsmZ regulatory small RNAs. Mol Microbiol. 2009;73:434–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06782.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrowes E, Baysse C, Adams C, O'Gara F. Influence of the regulatory protein RsmA on cellular functions in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, as revealed by transcriptome analysis. Microbiology. 2006;152:405–418. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delumeau O, Dutta S, Brigulla M, Kuhnke G, Hardwick SW, Völker U, et al. Functional and structural characterization of RsbU, a stress signaling protein phosphatase 2C. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:40927–40937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405464200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figurski DH, Helinski DR. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:1648–1652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.4.1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filloux A, Hachani A, Bleves S. The bacterial type VI secretion machine: yet another player for protein transport across membranes. Microbiology. 2008;154:1570–1583. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/016840-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman L, Kolter R. Genes involved in matrix formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 biofilms. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:675–690. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvis S, Munder A, Ball G, de Bentzmann S, Wiehlmann L, Ewbank JJ, et al. Caenorhabditis elegans semi-automated liquid screen reveals a specialized role for the chemotaxis gene cheB2 in Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000540. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González N, Heeb S, Valverde C, Kay E, Reimmann C, Junier T, Haas D. Genome-wide search reveals a novel GacA-regulated small RNA in Pseudomonas species. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:167. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman AL, Kulasekara B, Rietsch A, Boyd D, Smith RS, Lory S. A signaling network reciprocally regulates genes associated with acute infection and chronic persistence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Dev Cell. 2004;7:745–754. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman AL, Merighi M, Hyodo M, Ventre I, Filloux A, Lory S. Direct interaction between sensor kinase proteins mediates acute and chronic disease phenotypes in a bacterial pathogen. Genes Dev. 2009;23:249–259. doi: 10.1101/gad.1739009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heurlier K, Williams F, Heeb S, Dormond C, Pessi G, Singer D, et al. Positive control of swarming, rhamnolipid synthesis, and lipase production by the posttranscriptional RsmA/RsmZ system in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:2936–2945. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.10.2936-2945.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu JL, Chen HC, Peng HL, Chang HY. Characterization of the histidine-containing phosphotransfer protein B-mediated multistep phosphorelay system in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:9933–9944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708836200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaniga K, Delor I, Cornelis GR. A wide-host-range suicide vector for improving reverse genetics in gram-negative bacteria: inactivation of the blaA gene of Yersinia enterocolitica. Gene. 1991;109:137–141. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90599-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimova G, Ullmann A, Ladant D. Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin as a tool to analyze molecular interaction in a bacterial two-hybrid system. Int J Med Microbiol. 2000;290:441–445. doi: 10.1016/S1438-4221(00)80060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay E, Dubuis C, Haas D. Three small RNAs jointly ensure secondary metabolism and biocontrol in Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17136–17141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505673102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay E, Humair B, Denervaud V, Riedel K, Spahr S, Eberl L, et al. Two GacA-dependent small RNAs modulate the quorum-sensing response in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:6026–6033. doi: 10.1128/JB.00409-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labaer J, Qiu Q, Anumanthan A, Mar W, Zuo D, Murthy TV, et al. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01 gene collection. Genome Res. 2004;14:2190–2200. doi: 10.1101/gr.2482804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski MA, Osborn E, Kazmierczak BI. A novel sensor kinase-response regulator hybrid regulates type III secretion and is required for virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 2004;54:1090–1103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04331.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz DH, Mok KC, Lilley BN, Kulkarni RV, Wingreen NS, Bassler BL. The small RNA chaperone Hfq and multiple small RNAs control quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi and Vibrio cholerae. Cell. 2004;118:69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz DH, Miller MB, Zhu J, Kulkarni RV, Bassler BL. CsrA and three redundant small RNAs regulate quorum sensing in Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol. 2005;58:1186–1202. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CT, Huang YJ, Chu PH, Hsu JL, Huang CH, Peng HL. Identification of an HptB-mediated multi-step phosphorelay in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Res Microbiol. 2006;157:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livny J, Brencic A, Lory S, Waldor MK. Identification of 17 Pseudomonas aeruginosa sRNAs and prediction of sRNA-encoding genes in 10 diverse pathogens using the bioinformatic tool sRNAPredict2. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:3484–3493. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mougous JD, Cuff ME, Raunser S, Shen A, Zhou M, Gifford CA, et al. A virulence locus of Pseudomonas aeruginosa encodes a protein secretion apparatus. Science. 2006;312:1526–1530. doi: 10.1126/science.1128393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessi G, Williams F, Hindle Z, Heurlier K, Holden MT, Camara M, et al. The global posttranscriptional regulator RsmA modulates production of virulence determinants and N-acylhomoserine lactones in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:6676–6683. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.22.6676-6683.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahme LG, Ausubel FM, Cao H, Drenkard E, Goumnerov BC, Lau GW, et al. Plants and animals share functionally common bacterial virulence factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8815–8821. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimmann C, Beyeler M, Latifi A, Winteler H, Foglino M, Lazdunski A, Haas D. The global activator GacA of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO positively controls the production of the autoinducer N-butyryl-homoserine lactone and the formation of the virulence factors pyocyanin, cyanide, and lipase. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:309–319. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3291701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigue A, Quentin Y, Lazdunski A, Méjean V, Foglino M. Two-component systems in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: why so many? Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:498–504. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01833-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romby P, Vandenesch F, Wagner EG. The role of RNAs in the regulation of virulence-gene expression. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2006;9:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T, editors. Molecular Cloning. Woodbury, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Smith AW, Iglewski BH. Transformation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by electroporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:10509. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.24.10509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RS, Iglewski BH. P. aeruginosa quorum-sensing systems and virulence. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2003;6:56–60. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(03)00008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svenningsen SL, Waters CM, Bassler BL. A negative feedback loop involving small RNAs accelerates Vibrio cholerae's transition out of quorum-sensing mode. Genes Dev. 2008;22:226–238. doi: 10.1101/gad.1629908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svenningsen SL, Tu KC, Bassler BL. Gene dosage compensation calibrates four regulatory RNAs to control Vibrio cholerae quorum sensing. EMBO J. 2009;28:429–439. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo-Arana A, Repoila F, Cossart P. Small noncoding RNAs controlling pathogenesis. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2007;10:182–188. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu KC, Bassler BL. Multiple small RNAs act additively to integrate sensory information and control quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi. Genes Dev. 2007;21:221–233. doi: 10.1101/gad.1502407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu KC, Waters CM, Svenningsen SL, Bassler BL. A small-RNA-mediated negative feedback loop controls quorum-sensing dynamics in Vibrio harveyi. Mol Microbiol. 2008;70:896–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06452.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallet I, Olson JW, Lory S, Lazdunski A, Filloux A. The chaperone/usher pathways of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: identification of fimbrial gene clusters (cup) and their involvement in biofilm formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6911–6916. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111551898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valverde C, Haas D. Small RNAs controlled by two-component systems. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;631:54–79. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-78885-2_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasseur P, Vallet-Gely I, Soscia C, Genin S, Filloux A. The pel genes of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAK strain are involved at early and late stages of biofilm formation. Microbiology. 2005;151:985–997. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27410-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventre I, Goodman AL, Vallet-Gely I, Vasseur P, Soscia C, Molin S, et al. Multiple sensors control reciprocal expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa regulatory RNA and virulence genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:171–176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507407103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weilbacher T, Suzuki K, Dubey AK, Wang X, Gudapaty S, Morozov I, et al. A novel sRNA component of the carbon storage regulatory system of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:657–670. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.