Abstract

Acute diarrheal disease is a leading cause of childhood morbidity and mortality in the developing world and Escherichia coli intestinal pathogens are important causative agents. Information on the epidemiology of E. coli intestinal pathogens and their association with diarrheal disease is limited because no diagnostic testing is available in countries with limited resources. To evaluate the prevalence of E. coli intestinal pathogens in a Caribbean–Colombian region, E. coli clinical isolates from children with diarrhea were analyzed by a recently reported two-reaction multiplex polymerase chain reaction (Gomez-Duarte et al., Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2009;63:1–9). The phylogenetic group from all E. coli isolates was also typed by a single-reaction multiplex polymerase chain reaction. We found that among 139 E. coli strains analyzed, 20 (14.4%) corresponded to E. coli diarrheagenic pathotypes. Enterotoxigenic, shiga-toxin–producing, enteroaggregative, diffuse adherent, and enteropathogenic E. coli pathotypes were detected, and most of them belonged to the phylogenetic groups A and B1, known to be associated with intestinal pathogens. This is the first report on the molecular characterization of E. coli diarrheogenic isolates in Colombia and the first report on the potential role of E. coli in childhood diarrhea in this geographic area.

Introduction

Diarrheal disease is a leading cause of mortality and morbidity in children living in underserved countries. Close to 2 millions of children below 5 years of age are estimated to die every year because of diarrheal diseases (Bryce et al., 2005; Boschi-Pinto et al., 2008). In Colombia, South America, several studies report the importance of rotavirus as a cause of infectious diarrhea (Correa et al., 1999; Urbina et al., 2003, 2004; Caceres et al., 2006; Gutierrez et al., 2006), and to a lesser extent, there are studies describing the role of bacterial infections in diarrheal disease, such as Shigella, Salmonella, and Vibrio cholerae infections (Mattar, 1992; Hidalgo et al., 2002; Manrique-Abril et al., 2006; Muñoz et al., 2006). Stool samples from children with diarrhea in the cities of Sincelejo and Cartagena, Colombia, tested positive for rotavirus (36.6%), Salmonella spp. (9.0%), Shigella spp. (8.0%), and pathogenic Escherichia coli (2.8%) (Urbina et al., 2003). In our study, the definition of pathogenic E. coli was based on detection of serotypes associated to enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) and the shiga-toxin–producing E. coli (STEC). No other E. coli pathotypes were evaluated.

Cartagena, Colombia, is a tourist destination and an important industrial city with a highly dynamic population. In contrast, Sincelejo is a city with an agricultural-based economy and minimal population movement. Of interest, rotavirus serotypes from children with diarrhea were significantly diverse in Cartagena, whereas only two serotypes were recognized in all samples tested from Sincelejo (Urbina et al., 2004). No information is available on the role of E. coli pathotypes in childhood diarrhea in these locations or whether pathotypes vary from city to city. Information on the role of E. coli in childhood diarrhea in Colombia is limited to reports describing the identification of the E. coli O157:H7 (Mattar and Vasquez, 1998) and non-O157:H7 STEC (Martinez et al., 2007) associated with cases of gastroenteritis. Information on enteropathogens associated with infectious diarrhea and the role of E. coli pathotypes is essential to understand the prevalence of these infections in the population at risk, to evaluate potential sources of transmission, and most importantly, to implement medical care and prevention strategies directed to decrease childhood morbidity and mortality due to diarrhea.

There are six E. coli intestinal pathotypes described in the literature, associated with acute diarrheal disease based on the array of virulence factors they express (Levine, 1987; Gomez-Duarte et al., 2009). These include STEC, EPEC, enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC), enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC), diffuse adherent E. coli (DAEC), and enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC). Extraintestinal E. coli pathotypes are also known to express a distinct set of virulence genes; however, because they are not associated with acute diarrhea they will not be analyzed in our study.

Identification of E. coli pathotypes in association with diarrhea is limited in many developing countries because conventional microbiological testing is unable to distinguish between normal flora and pathogenic strains of E. coli. Although molecular diagnostic systems may detect intestinal E. coli pathogens, countries with limited resources may not afford their implementation. Despite multiple assays have been developed for typing E. coli intestinal pathotypes (Stacy-Phipps et al., 1995; Nguyen et al., 2005; Aranda et al., 2007; Brandal et al., 2007), most assays rely on technologies not available in most clinical laboratories. A recently reported three-sample multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was developed for use in any clinical laboratory, including those with limited resources (Gomez-Duarte et al., 2009). It is capable of identifying diarrheagenic E. coli strains as well as other non-E. coli pathogens. This method uses plasmid DNA as control DNA templates instead of prototype wild-type strains. This factor obviates the need for −70°C freezers for strain storage. Further, the assay uses master mix Taq polymerase (this mix contains polymerase, polymerase buffer, nucleotides, and magnesium chloride) to eliminate the need to prepare multiple reagents.

Phylogenetic analysis of E. coli clinical isolates classifies E. coli strains into four phylogenetic or clonal groups, namely, A, B1, B2, and D (Herzer et al., 1990). Each clonal group is believed to be associated with specific pathogenesis determinants. Intestinal E. coli pathotypes tend to associate with phylogenetic groups A and B1, but extraintestinal E. coli pathotypes generally associate with phylogenetic groups B2 and D (Boyd and Hartl, 1998; Johnson et al., 2002). This type of analysis is believed to be superior to serotyping because lipopolysaccharide (O) and flagellar (F) antigens undergo significant variation independently of virulence. Several E. coli phylogenetic typing methods exist, including multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (Ochman and Selander, 1984), multilocus sequencing typing (Maiden et al., 1998), and PCR (Clermont, 2000). Although multilocus sequencing typing is more discriminatory and suitable for analysis of strains from infection outbreaks, PCR phylogenetic testing provides information on the main phylogenetic groups in relation to intestinal versus extraintestinal E. coli strains, as previously described (Boyd and Hartl, 1998; Johnson et al., 2002). PCR phylogenetic testing, however, is simple, reproducible, and accessible to most laboratories in countries with limited resources.

The goal of our study was to evaluate the prevalence of E. coli pathotypes among children with diarrhea in Colombia using a two-sample multiplex PCR. E. coli clinical isolates were obtained from children below 5 years of age and living in two Caribbean–Colombian cities. We evaluated the differences in E. coli pathotypes as well as in phylogenetic groups, cities of origin, and children's age. Phylogenetic grouping will be assessed by a second multiplex PCR, with the goal of determining the degree of E. coli diversity among all clinical isolates and specifically among E. coli intestinal pathotypes.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This is a prevalence study for evaluating the number of E. coli pathotypes circulating in children with diarrhea in two Northern Colombian cities. Stool samples were collected from children less than 5 years of age with diarrhea and living in Sincelejo and Cartagena, Colombia, after informed consent was obtained from their parents. All children evaluated at health clinics fulfilled the World Health Organization criteria for acute diarrheal disease (WHO, 2005). Subjects were identified by age, date, and location. A total of 267 stool samples were collected and processed during a 1-year period from January to November 2007. Among them, 139 E. coli isolates were recovered, 28 from Cartagena and 111 from Sincelejo.

Sample processing

All stool samples used in our study had been previously collected by healthcare personnel at each medical center in Cartagena or Sincelejo for diagnosis purposes. A cotton swab was used to obtain a stool sample from the original specimen. The samples were placed in Stuart transport media (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) and taken to the Microbiology Laboratory, University of Cartagena, for further processing. The samples that could no be processed immediately were transported and stored at 4°C. E. coli isolates were obtained by culturing stool samples on McConkey or eosin methylene blue agar. Lactose-fermenting Gram-negative coccobacilli were tested with conventional biochemical assay for identification of E. coli. E. coli isolates were further confirmed by PCR amplification of the β-d-glucuronidase (uigA) gene using E. coli specific primers (Table 1) (McDaniels et al., 1996).

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide Primers for Multiplex and Single Polymerase Chain Reaction Assays

| Primer mix | Primer sequence | Primer name | Gene target | PCR Size (bp) | Pathotype | Plasmid controla |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1b | 5′-GAGCGAAATAATTTATATGTG-3′ | VT.F | VT | 518 | STEC | pOG401 |

| 5′-TGATGATGGCAATTCAGTAT-3′ | VT.R | |||||

| 5′-CTGAACGGCGATTACGCGAA-3′ | eae.F | eae | 917 | STEC, EPEC | pOG390 | |

| 5′-CGAGACGATACGATCCAG-3′ | eae.R | |||||

| 5′-AATGGTGCTTGCGCTTGCTGC-3′ | bfpA.F | bfpA | 326 | EPEC | pOG394 | |

| 5′-GCCGCTTTATCCAACCTGGTA-3′ | bfpA.R | |||||

| 5′-GTATACACAAAAGAAGGAAGC-3′ | aggR.F | aggR | 254 | EAEC | pOG395 | |

| 5′-ACAGAATCGTCAGCATCAGC-3′ | aggR.F | |||||

| M2b | 5′-GCACACGGAGCTCCTCAGTC-3′ | LT.F | LT | 218 | ETEC | pWD299 |

| 5′-TCCTTCATCCTTTCAATGGCTTT-3′ | LT.R | |||||

| 5′-GCTAAACCAGTAGAG(C)TCTTCAAAA-3′ | ST.F | ST | 147 | ETEC | pSLm004 | |

| 5′-CCCGGTACAG(A)GCAGGATTACAACA-3′ | ST.R | |||||

| 5′-GAACGTTGGTTAATGTGGGGTAA-3′ | daaE.F | daaE | 542 | DAEC | pOG391 | |

| 5′-TATTCACCGGTCGGTTATCAGT-3′ | daaE.R | |||||

| 5′-AGCTCAGGCAATGAAACTTTGAC-3′ | virF.F | virF | 618 | EIEC | pOG392 | |

| 5′-TGGGCTTGATATTCCGATAAGTC-3′ | virF.R | |||||

| 5′-CTCGGCACGTTTTAATAGTCTGG-3′ | ipaH.F | ipaH | 933 | EIEC | pOG393 | |

| 5′-GTGGAGAGCTGAAGTTTCTCTGC-3′ | ipaH.R | |||||

| Pc | 5′-GACGAACCAACGGTCAGGAT-3′ | chuA.F | chuA | 279 | NA | – |

| 5′-TGCCGCCAGTACCAAAGACA-3′ | chuA.R | |||||

| 5′-TGAAGTGTCAGGAGACGCTG-3′ | yiaA.F | yiaA | 211 | NA | – | |

| 5′-ATGGAGAATGCGTTCCTCAAC-3′ | yiaA.R | |||||

| 5′-GAGTAATGTCGGGGCATTCA-3′ | TspE4C2.F | TspE4C2 | 152 | NA | – | |

| 5′-CGCGCCAACAAAGTATTACG-3′ | TspE4C2.R | |||||

| VT1 | 5′-CAGTTAATGTGGTGGCGAAGG-3 | VT1.F | VT1 | 348 | STEC | – |

| 5′-CACCAGACAATGTAACCGCTG-3′ | VT1.R | |||||

| VT2 | 5′-ACCGTTTTTCAGATTTT(G/A)CACATA-3′ | VT2.F | VT2 | 298 | STEC | – |

| 5′-TACACAGGAGCAGTTTCAGACAGT-3′ | VT2.R | |||||

| uigA | 5′-GCGTCTGTTGACTGGCAGGTGGTGG-3′ | uidA.F | uidA | 503 | NA | – |

| 5′- GTTGCCCGCTTCGAAACCAATGCCT-3′ | uidA.R |

M1 and M2 are primer mixes to be used for the two-sample multiplex PCR assay for detection of Escherichia coli pathotypes.

Plasmids carrying each one of the E. coli pathotype gene targets. Plasmids are used as template DNA control for the two-sample multiplex PCR assay as previously described (Gomez-Duarte et al., 2009).

P is the primer mix to be used for a single-multiplex PCR for identification of phylogenetic group (Clermont et al., 2000).

PCR, polymerase chain reaction; EPEC, enteropathogenic Escherichia coli; STEC, shiga-toxin producing E. coli; EAEC, enteroaggregative E. coli; ETEC, enterotoxigenic E. coli; DAEC, diffuse adherent E. coli; EIEC, enteroinvasive E. coli; NA, not applicable.

DNA techniques

Unless otherwise specified, standard methods were used for plasmid isolation, genomic DNA isolation, and agarose electrophoresis DNA separation (Sambrook and Russell, 2001).

E. coli pathotype identification by multiplex PCR

E. coli clinical isolates were processed for isolation of genomic DNA as previously described (Gomez-Duarte et al., 2009). In brief, overnight liquid cultures were centrifuged, and the pellet was resuspended in water, boiled for 10 min, and centrifuged again. The supernatant containing a crude DNA extract was used as a DNA template on a multiplex PCR for identification of E. coli pathotypes, namely, EPEC, STEC, EAEC, ETEC, DAEC, and EIEC. The E. coli pathotype two-sample multiplex PCR was carried out using plasmid DNA with cloned targets as positive controls and plasmid DNA vectors as negative clones, as previously described (Gomez-Duarte et al., 2009). In brief, there was one plasmid clone for each gene target, while plasmid vectors pCR2.1 and pSC-A and E. coli flora genomic DNA were used as negative controls. The PCR 1 contained M1 primers for amplification of eae, bfpA, VT, and aggR genes for identification of STEC, EPEC, and EAEC pathotypes (Table 1). The PCR 2 contained M2 primers for amplification of LT, ST, daaE, ipaH, and virF gene targets for identification of ETEC, DAEC, and EIEC pathotypes. One microliter of genomic DNA was mixed with 24 μL of a premade mix containing primers at a 0.2 μM final concentration and Platinum Blue PCR SuperMix polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The PCR program used for amplification consisted of 2 min at 94°C denaturing temperature, followed by 40 cycles of 30 sec at 92°C denaturing temperature, 30 sec at 59°C annealing temperature, and 30 sec at 72°C extension temperature. At the end of 40 cycles and a 5-min extension at 72°C, samples were separated onto a 2% agarose ethidium bromide-stained gel, and DNA bands were visualized and recorded under ultraviolet light for further analysis.

Those E. coli isolates identified as STEC were further analyzed for determination of the type of verotoxin they carry. This was done by a standard single PCR using specific shiga-like toxin 1 (VT1) (Vidal et al., 2005) and shiga-like toxin 2 (VT2) (Nguyen et al., 2005) oligonucleotide primers (Table 1).

E. coli phylogenetic grouping

Identification of the phylogenetic group for each E. coli strain was determined by the amplification of a set of DNA targets using a single multiplex PCR as previously described (Clermont et al., 2000). In brief, genomic DNA from each strain was used for multiplex PCR DNA amplification of genes chuA, yjaA and of DNA region TSPE4.C2. The reaction contained three primer pairs, including ChuA.F and ChuAR, YjaAF and YjaAR, and TspE4C2F and TspE4C2R (Table 1). Amplified DNA from each strain was separated onto a 2.0% agarose and analyzed as described earlier. Based on the number and type of target amplified the isolate was assigned a phylogenetic group. Phylogenetic group A was assigned to isolates chuA negative and TspE4.C2 negative; group B1 was assigned to isolates chuA negative and TspE4.C2 positive; group B2 was assigned to isolates chuA positive and yjaA positive; and group D was assigned to isolates chuA positive and yjaA negative. All PCRs were performed more than once to confirm the results. Previously reported E. coli strains (Boyd and Hartl, 1998) were used as phylogenetic group controls: E. coli ECOR1 for group A, ECOR29 for group B1, ECOR53 for group B2, and ECOR47 for group D. Strains were kindly provided by Dr. Weismann at the University of Washington.

Serologic testing for E. coli O157:H7

E. coli strains positive for VT by PCR were tested for the presence of O157 antigen and H7 flagellar antigen. Anti-O157 antiserum (Difco, Sparks, MD) and anti-H7 antiserum (Difco) were added to bacterial suspension to evaluate for agglutination. A clinically isolated O157:H7 STEC strain was used as positive control and the O8:H9 E9034A ETEC strain (Gomez-Duarte et al., 2007) was used as negative control. The agglutination protocol was carried out as recommended by the antiserum suppliers.

Statistical analysis

Fisher's exact test or one-way analysis of variance was conducted to determine the differences and associations between E. coli isolates and pathotypes, phylogenetic groups, city of origin, and patient age. All statistical calculations used the GraphPad InStat version 3.06 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA; www.graphpad.com). For all calculations the p-value for statistical significance was set at <0.05.

Results

E. coli pathotypes identified among clinical isolates

Twenty (14.4%) E. coli strains out of 139 clinical isolates were positive for any of the six known E. coli pathotypes associated with diarrhea. This indicates that 14.4% of all E. coli isolates were E. coli intestinal pathotypes, and that 7.5% of all stool samples collected contained an E. coli intestinal pathotype. The most frequent pathotype was ETEC (Table 2), which corresponded to 5% of the total number of E. coli isolates studied. Other E. coli pathotypes identified included STEC, EPEC, EAEC, and DAEC. There was a group made up of E. coli strains that were either positive for virulence factors from more that one pathotype, or were positive for a single virulence factor not sufficient to identify that strain as a typical pathotype. This group corresponded to 4% of the total E. coli isolates analyzed, and it was made of E. coli strains carrying any combination of VT, LT, ST, eae, or bfpA genes.

Table 2.

Distribution of Escherichia coli Clinical Isolates According to Pathotypes, Host's Age, and City of Origin

| |

Children's age |

City of origin |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

≤2 years |

>2 years |

|

Cartagena |

Sincelejo |

|

||||

| Pathotypes | No. | % | No. | % | p-Value | No. | % | No. | % | p-Value |

| STEC | 3 | 3.5 | 2 | 3.8 | >0.99 | 1 | 3.6 | 4 | 3.6 | >0.99 |

| EPEC | 1 | 1.2 | 0 | 0 | >0.99 | 1 | 3.6 | 0 | 0 | 0.201 |

| EAEC | 2 | 2.3 | 0 | 0 | 0.524 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.8 | >0.99 |

| ETEC | 6 | 6.9 | 1 | 1.9 | 0.251 | 2 | 7.1 | 5 | 4.5 | 0.628 |

| DAEC | 1 | 1.2 | 0 | 0 | >0.99 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.9 | >0.99 |

| Mix | 3 | 3.5 | 1 | 1.9 | >0.99 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3.6 | 0.582 |

| Negative | 70 | 81.4 | 49 | 92.5 | 0.084 | 24 | 85.7 | 95 | 85.6 | >0.99 |

| Total | 86 | 100 | 53 | 100 | 28 | 100 | 111 | 100 | ||

Low rates of STEC, EPEC, EAEC, and DAEC were identified, and these accounted for less than 7% of the isolates. Further, EPEC and STEC isolates were all atypical as EPEC isolates were only positive for eae and negative for bfpA, and all STEC isolates were positive for VT and negative for eae. STEC strains were positive for either VT1 or VT2, or both. None of the STEC strains identified were positive for serotype O157:H7 according to agglutination testing with anti-O157 or anti-H7 antisera.

These data indicate that E. coli pathotypes are circulating in the pediatric population of two Northern Colombian cities and that these isolates may be associated to children with diarrhea. While ETEC was the predominant pathotype, this difference was not statistically significant with respect to children's age, city of origin, or E. coli pathotypes.

Proportion of E. coli pathotypes based on children's age

All E. coli isolates from children with diarrhea were analyzed according to children age and E. coli pathotype. The proportion of E. coli positive for any intestinal pathotype was 18.6% in children less than 2 years of age and only 7.5% in children above 2 years this difference; however, it is not statistically significant. EAEC, EPEC, and DAEC isolates were identified in children less than 2 years of age only, whereas ETEC and STEC pathotypes were identified in both age groups, above 2 years and below 2 years. The number of enteric E. coli pathotypes was similar with respect to city of origin, and the difference in E. coli pathotypes between Cartagena and Sincelejo was not statistically significant (Table 2).

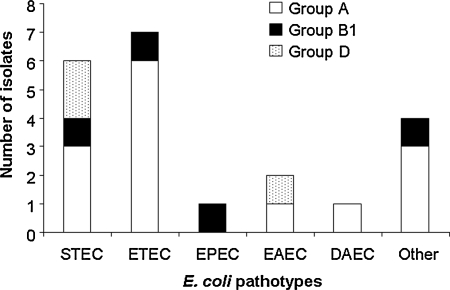

Phylogenetic groups A and B1 were the most common among E. coli pathotypes

One hundred eight E. coli isolates (77.1%) of all E. coli isolates belong to the phylogenetic groups A and B1, which are known to be associated with the gastrointestinal tract. The remaining isolates were distributed between phylogenetic groups B2 and D. B2 was the phylogenetic group least represented, with only 10 strains (Table 3). Among all enteric E. coli pathotypes, 85.0% belong to the phylogenetic groups A and B1 and the remaining to phylogenetic group D. There were no representatives from phylogenetic group B2 among the E. coli intestinal pathotypes. Among the 20 E. coli pathotypes identified, ETEC, EPEC, DAEC, and mixed pathotypes were members of the phylogenetic groups A and B1. Only STEC and EAEC had representatives from phylogenetic group D in addition to phylogenetic groups A and/or B (Fig. 1). No significant difference in phylogenetic groups was observed when E. coli isolated from children less than 2 years of age was compared with children above 2 years of age (Table 3). When phylogenetic group means were compared from the two age group populations, the difference between phylogenetic group A and the remaining groups was statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Distribution of Escherichia coli Clinical Isolates According to Phylogenetic Groups, Host's age, and City of Origin

| |

Children's age |

City of origin |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

≤2 years |

>2 years |

|

Cartagena |

Sincelejo |

|

||||

| Phylogenetic group | No. | % | No. | % | p-Value | No. | % | No. | % | p-Value |

| Group A | 49 | 56.32 | 36 | 67.92 | 0.212 | 15 | 53.57 | 71 | 63.96 | 0.384 |

| Group B1 | 15 | 17.24 | 8 | 15.09 | 0.817 | 3 | 10.71 | 19 | 17.12 | 0.056 |

| Group B2 | 7 | 8.05 | 3 | 5.66 | 0742 | 2 | 7.14 | 8 | 7.21 | >0.99 |

| Group D | 16 | 18.39 | 6 | 11.32 | 0.341 | 8 | 28.57 | 13 | 11.71 | 0.037a |

| Total | 87 | 100.00 | 53 | 100.00 | 28 | 100.00 | 111 | 100.00 | ||

Statistically significant p-value of <0.005.

FIG. 1.

Distribution of phylogenetic groups according to Escherichia coli pathotypes. E. coli pathotypes were individually analyzed with respect to their phylogenetic group. Only three phylogenetic groups (A, B1, and D) were represented because no E. coli pathotype strain from phylogenetic group B2 was identified.

The proportion of E. coli from two Colombian cities differs with respect to pathotypes and phylogenetic groups

To determine the distribution of E. coli pathotypes between the two cities, we compared the number of intestinal E. coli pathotypes and negative E. coli pathotypes between the two cities. In both cities the proportion of positive pathotypes was close to 14%. Similarly, the proportion of E. coli isolates from phylogenetic groups A, B1, and B2 was similar in Sincelejo and Cartagena, with the exception of group D isolates, which were twofold more common in Cartagena than in Sincelejo, a result that is statistically significant (Table 3). Further, the proportion of ETEC and STEC pathotypes was similar in both cities; however, the proportion of EAEC and DAEC was different because these pathotypes were not detected in Cartagena. This is likely related to the smaller number of E. coli clinical isolates analyzed in Cartagena; the difference was not statistically significant.

Discussion

Acute dehydrating diarrhea remains a leading cause of mortality in the developing world, and oral hydration is not sufficient to alter the disproportionate number of deaths due to the condition, especially in low-income nations (Forsberg et al., 2007). Surveillance for diarrheal etiologic agents in developing nations is necessary to understand the local epidemiology of infectious diarrhea and to measure the burden of disease in children (Gomez-Duarte, 2009; Gomez-Duarte et al., 2009). Based on this information it may be possible to implement public health measures directed to control and prevent specific causes of infectious diarrhea. In our study we have analyzed the presence of intestinal enteric E. coli pathotypes among children with infectious diarrhea in Colombia. To our knowledge, this is the first report describing the molecular characterization of E. coli enteropathogens in this country and the potential role of ETEC in childhood diarrhea in this part of the country.

Representatives of five E. coli pathotypes were isolated from stool samples from children with diarrhea in two coastal cities in Colombia, and ETEC was the most common pathotype. The calculated prevalence of 7.5% of enteric E. coli pathotypes among all stools tested corroborates previous results reporting 6% pathogenic E. coli in Colombia (Urbina et al., 2003). The predominance of the ETEC pathotype in our study is comparable with data reported in Tunisia (Al-Gallas et al., 2007), Bangladesh (Qadri et al., 2007), and Egypt (Shaheen et al., 2009). This is in contrast to the EAEC pathotype which was found to be the predominant pathotype in Brazil (Bueris et al., 2007), Tanzania (Moyo et al., 2007), and the United States (Cohen et al., 2005).

Our study also reveals that children less than 5 years of age are at risk of diarrheagenic E. coli. We speculate that children at this age are immunologically naive and may not possess specific immune response to new pathogens. Our study cannot answer the specific role of diarrheagenic E. coli in diarrhea, as no other pathogens were investigated, including non-E. coli bacterial pathogens or viral agents. One limitation of our study was the small number of strains isolated, mainly from Cartagena, to be analyzed for city of origin, children's age, pathotypes, and phylogenetic groups. A larger study comparing children with diarrhea with healthy controls, from both Sincelejo and Cartagena, will be necessary to determine the proportion of children of different ages who, after initial infection with diarrheagenic E. coli, remain colonized with these strains and become normal carriers. These studies may also calculate the proportion of children who, after recovery from infectious diarrhea, eradicate the infection and become immune to new infections.

Our study used a two-sample PCR assay to detect a specific set of virulence genes and clearly identified most E. coli pathotypes. The presence of LT or ST identified ETEC, VT identified STEC, eae (alone or in combination with bfpA) identified EPEC, and virF identified EIEC. Scientific debate continues regarding the virulence gene-based definition of EAEC and DAEC pathotypes, because not all virulence genes associated with these strains are present in 100% of them or are associated with human disease. Until these debates are settled, we believe that the EAEC global virulence regulatory aggR gene and the DAEC fimbrial daaE gene are appropriate for detection.

Regarding phylogeny, most E. coli isolates including intestinal E. coli pathotypes belong to the phylogenetic groups A and B1. These data indicate that the majority of E. coli isolates analyzed are representatives of intestinal flora as well as intestinal pathogens. Most E. coli pathotypes in our study belong to the phylogenetic group A and B1, and some STEC and EAEC isolates were representatives of the phylogenetic group D. Because the virulence factors that define E. coli intestinal pathotypes are present in phages (VT toxin genes), pathogenicity islands (eae), or virulence plasmids (aggR), it is likely that horizontal transfer of these genes has occurred from group A or B1 E. coli ancestors to new group D and even group B2 E. coli permissive recipients, as recently reported (Escobar-Paramo et al., 2004). More studies are necessary to clarify the role of E. coli pathotypes from phylogenetic groups B2 and D to determine what proportion of theses strains are true intestinal pathogens.

Our study also recognized the diversity of E. coli pathotypes in these Colombian cities by detecting clinical isolates carrying virulence genes from different pathotypes. The identification of this group of isolates indicates that E. coli pathotypes in this geographic region is highly diverse and it suggests that horizontal transfer of virulence genes is occurring among E. coli intestinal pathotypes. The successful colonization of these strains may suggest that these strains are well adapted to the human intestinal environment and may potentially be more virulent. Reports indicate that this phenomenon is not uncommon as EAEC was reported to acquire virulence markers from DAEC (Czeczulin et al., 1999). A small number of EPEC and STEC strains were also identified; all of them were atypical as EPEC were only positive for eae and negative for bfpA and STEC were positive for VT and negative for eae.

All STEC strains identified were negative for the O157:H7 serotype. These data correlate with recent findings indicating that the prevalence of O157:H7 STEC in Colombia is low (Martinez et al., 2007). Non-O157:H7 STEC strains have been described in other Latin American countries such as Brazil (Bueris et al., 2007) and Mexico (Estrada-Garcia et al., 2009). While O157:H7 is the predominant STEC associated with hemolytic–uremic syndrome outbreaks in the United States, Europe, Argentina, and Australia, non-O157:H7 STEC-associated outbreaks are increasingly recognized worldwide (Johnson et al., 2006). In Iran, non-O157:H7 STEC strains are the predominant agents associated with severe diarrheal infections; in this country the most common STEC serotypes were O25:H3, O85:H32, and O162:H21 (Aslani and Bouzari, 2009). Similarly, all STEC isolates evaluated in Poland were non-O157:H7 (Sobieszczanska et al., 2004), indicating that the prevalence of STEC O157:H7 and non-O157:H7 serotypes may widely vary according to geographic location. More studies in Colombia will be necessary to assess whether non-O157:H7 STEC strains predominate in all Colombian regions and neighbor countries, and also to evaluate the association of these strains with cases of bloody diarrhea and hemolytic–uremic syndrome in children and adults.

Although Cartagena is a tourist city, with highly dynamic population and significantly better infrastructure than Sincelejo, no statistically significant differences were noticed in the number and type of E. coli identified, except for the increased number of E. coli isolates from phylogenetic group D in Cartagena. We speculate that the increased number of group D E. coli strains may be the result of transmission from colonized travelers to the native population. More studies are needed to identify the most common diarrheagenic E. coli reservoirs and the transmission patterns within the children population. Studies in Colombia are currently testing meats and vegetables from retails stores for bacterial contamination. Preliminary results indicate the presence of diarrheogenic E. coli contaminants in these food products (our unpublished results).

Living conditions in the Colombian Caribbean region may differ from other cities in Colombia. It is likely that the proportion of E. coli pathotypes vary according to the geographic region. Epidemiological studies using similar technology may provide clues to whether E. coli is widely spread or limited to temperate climates. PCR technology can facilitate the identification of possible sources of diarrheagenic E. coli contamination. These sources may include water for human consumption, food products, caregivers (healthcare and nonhealthcare workers), and even city air. Epidemiological information obtained by these means may contribute to the control of infectious diarrhea at different levels. First, it will increase the understanding of the impact of E. coli on childhood diarrhea in Colombia. It may help implement mechanisms of disease control and prevention, including vaccines. Also, it may facilitate the implementation of strategies to manage diarrhea secondary to each one of the E. coli pathotypes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by awards to O.G.G.-D. and include an NIH K12 mentored research award, Children's Miracle Network grant 1892 (2007 University of Iowa Children's Hospital), and an NIH K08 mentored research award. The authors thank Dr. Scott Weismann at the University of Washington for providing E. coli control strains for phylogenetic testing and helpful advice. They express their gratitude to bacteriologist Erika Mendoza Bitar at the Hospital Pediátrico San Francisco de Asís, Sincelejo, for technical assistance with sample collection. They also thank Paul Casella for critically reading the manuscript and providing invaluable advice.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Al-Gallas N. Bahri O. Bouratbeen A. Ben Haasen A. Ben Aissa R. Etiology of acute diarrhea in children and adults in Tunis, Tunisia, with emphasis on diarrheagenic Escherichia coli: prevalence, phenotyping, and molecular epidemiology. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:571–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aranda KR. Fabbricotti SH. Fagundes-Neto U. Scaletsky IC. Single multiplex assay to identify simultaneously enteropathogenic, enteroaggregative, enterotoxigenic, enteroinvasive and Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains in Brazilian children. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;267:145–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslani MM. Bouzari S. Characterization of virulence genes of non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolates from two provinces of Iran. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2009;62:16–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boschi-Pinto C. Velebit L. Shibuya K. Estimating child mortality due to diarrhoea in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:710–717. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.050054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd EF. Hartl DL. Chromosomal regions specific to pathogenic isolates of Escherichia coli have a phylogenetically clustered distribution. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1159–1165. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.5.1159-1165.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandal LT. Lindstedt BA. Aas L. Stavnes TL. Lassen J. Kapperud G. Octaplex PCR and fluorescence-based capillary electrophoresis for identification of human diarrheagenic Escherichia coli and Shigella spp. J Microbiol Methods. 2007;68:331–341. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryce J. Boschi-Pinto C. Shibuya K. Black RE WHO Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group. WHO estimates of the causes of death in children. Lancet. 2005;365:1147–1152. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71877-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bueris V. Sircili MP. Taddei CR, et al. Detection of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli from children with and without diarrhea in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2007;102:839–844. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762007005000116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caceres DC. Pelaez D. Sierra N. Estrada E. Sanchez L. Burden of rotavirus-related disease among children under five, Colombia, 2004. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2006;20:9–21. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892006000700002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clermont O. Bonacorsi S. Bingen E. Rapid and simple determination of the Escherichia coli phylogenetic group. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:4555–4558. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.10.4555-4558.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MB. Nataro JP. Bernstein DI. Hawkins J. Roberts N. Staat MA. Prevalence of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in acute childhood enteritis: a prospective controlled study. J Pediatr. 2005;146:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correa A. Solarte Y. Barrera J. Mogollon D. Gutierrez MF. Molecular characterization of rotavirus in the city of Santafe de Bogota, Colombia. Determination of the electrophenotypes and typing of a strain by RT-PCR. Rev Latinoam Microbiol. 1999;41:167–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeczulin JR. Whittam TS. Henderson IR. Navarro-Garcia F. Nataro JP. Phylogenetic analysis of enteroaggregative and diffusely adherent Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2692–2699. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2692-2699.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar-Paramo P. Clermont O. Blanc-Potard AB. Bui H. Le Bouguenec C. Denamur E. A specific genetic background is required for acquisition and expression of virulence factors in Escherichia coli. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21:1085–1094. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada-Garcia T. Lopez-Saucedo C. Thompson-Bonilla R, et al. Association of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli Pathotypes with infection and diarrhea among Mexican children and association of atypical Enteropathogenic E. coli with acute diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:93–98. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01166-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg BC. Petzold MG. Tomson G. Allebeck P. Diarrhoea case management in low- and middle-income countries—an unfinished agenda. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:42–48. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06.030866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Duarte OG. Rapid diagnostics for diarrhoeal disease surveillance in less developed countries. Clin Lab Int. 2009;33:7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Duarte OG. Bai J. Newell E. Detection of Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Yersinia enterocolitica, Vibrio cholerae, and Campylobacter spp. enteropathogens by 3-reaction multiplex polymerase chain reaction. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;63:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Duarte OG. Chattopadhyay S. Weissman SJ. Giron JA. Kaper JB. Sokurenko EV. Genetic diversity of the gene cluster encoding longus, a type IV pilus of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:9145–9149. doi: 10.1128/JB.00722-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez MF. Matiz A. Trespalacios AA. Parra M. Riano M. Mercado M. Virus diversity of acute diarrhea in tropical highlands. Rev Latinoam Microbiol. 2006;48:17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzer PJ. Inouye S. Inouye M. Whittam TS. Phylogenetic distribution of branched RNA-linked multicopy single-stranded DNA among natural isolates of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6175–6181. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6175-6181.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo M. Realpe ME. Munoz N, et al. Acute diarrhea outbreak caused by Shigella flexneri at a school in Madrid, Cundinamarca: phenotypic and genotypic characterization of the isolates. Biomedica. 2002;22:272–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JR. Kuskowski MA. O'Bryan TT. Maslow JN. Epidemiological correlates of virulence genotype and phylogenetic background among Escherichia coli blood isolates from adults with diverse-source bacteremia. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:1439–1447. doi: 10.1086/340506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KE. Thorpe CM. Sears CL. The emerging clinical importance of non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1587–1595. doi: 10.1086/509573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine MM. Escherichia coli that cause diarrhea: enterotoxigenic, enteropathogenic, enteroinvasive, enterohemorrhagic, and enteroadherent. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:377–389. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.3.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiden MC. Bygraves JA. Feil E, et al. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3140–3145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manrique-Abril FG. Tigne y Diane B. Bello SE. Ospina JM. Diarrhoea-causing agents in children aged less than five in Tunja, Colombia. Rev Salud Publica (Bogota) 2006;8:88–97. doi: 10.1590/s0124-00642006000100008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez AJ. Bossio CP. Durango AC. Vanegas MC. Characterization of Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli isolated from foods. J Food Prot. 2007;70:2843–2846. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-70.12.2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattar S. Mora A. Bernal N. Prevalence of E. coli O157:H7 in a pediatric population in Bogota, D.C. with acute gastroenteritis. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 1992;15:364–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattar S. Vasquez E. Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection in Colombia. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:126–127. doi: 10.3201/eid0401.980120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniels AE. Rice EW. Reyes AL. Johnson CH. Haugland RA. Stelma GN., Jr Confirmational identification of Escherichia coli, a comparison of genotypic and phenotypic assays for glutamate decarboxylase and beta-d-glucuronidase. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3350–3354. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.9.3350-3354.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyo SJ. Maselle SY. Matee MI. Langeland N. Mylvaganam H. Identification of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli isolated from infants and children in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:92. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-7-92. (Online.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz N. Realpe ME. Castaneda E. Agudelo CI. Characterization by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of Salmonella typhimurium isolates recovered in the acute diarrheal disease surveillance program in Colombia, 1997–2004. Biomedica. 2006;26:397–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TV. Le Van P. Le Huy C. Gia KN. Weintraub A. Detection and characterization of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli from young children in Hanoi, Vietnam. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:755–760. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.2.755-760.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochman H. Selander RK. Evidence for clonal population structure in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:198–201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.1.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qadri F. Saha A. Ahmed T. Al Tarique A. Begum YA. Svennerholm AM. Disease burden due to enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in the first 2 years of life in an urban community in Bangladesh. Infect Immun. 2007;75:3961–3968. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00459-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J. Russell DW. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen HI. Abdel Messih IA. Klena JD, et al. Phenotypic and genotypic analysis of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in samples obtained from Egyptian children presenting to referral hospitals. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:189–197. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01282-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobieszczanska B. Gryko R. Kuzko K. Dworniczek E. Prevalence of non-O157 Escherichia coli strains among shiga-like toxin-producing (SLTEC) isolates in the region of Lower Silesia, Poland. Scand J Infect Dis. 2004;36:219–221. doi: 10.1080/00365540410019363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy-Phipps S. Mecca JJ. Weiss JB. Multiplex PCR assay and simple preparation method for stool specimens detect enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli DNA during course of infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1054–1059. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1054-1059.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbina D. Arzuza O. Young G. Parra E. Castro R. Puello M. Rotavirus type A and other enteric pathogens in stool samples from children with acute diarrhea on the Colombian northern coast. Int Microbiol. 2003;6:27–32. doi: 10.1007/s10123-003-0104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbina D. Rodriguez JG. Arzuza O, et al. G and P genotypes of rotavirus circulating among children with diarrhea in the Colombian northern coast. Int Microbiol. 2004;7:113–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal M. Kruger E. Duran C. Lagos R. Levine M. Prado V. Toro C. Vidal R. Single multiplex PCR assay to identify simultaneously the six categories of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli associated with enteric infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:5362–5365. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.10.5362-5365.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [WHO] World Health Organization. The Treatment of Diarrhea: A Manual for Physicians and Other Senior Health Workers. Geneva: WHO; 2005. [Google Scholar]