Abstract

An important attribute of the adaptive immune system is the ability to remember a prior encounter with a pathogen; an ability termed immunological memory. Bigger, better and stronger responses are mounted upon a secondary encounter with the pathogen potentially resulting in clearance of the infection before the development of disease. We will review recent advances in the field of memory CD8+ T cell differentiation focusing on both intrinsic and extrinsic factors that govern the development of T cell memory.

Where it all begins

T cell development begins within the thymus from bone marrow derived progenitor cells and involves the acquisition of a T cell receptor (TCR) that fits with the allelic forms of the MHC molecules expressed in the individual. TCR diversity is vast arising from the imprecise random rearrangement of inherited gene segments for each chain. Prior to egress from the thymus the majority of cells that bear either self reactive or non-functional TCR rearrangements are purged from the repertoire. Positive selection results in the survival of cells that express a TCR capable of interacting weakly with self MHC plus self peptide while negative selection deletes cells that express TCRs that recognize self peptide/MHC ligands with too high affinity. Thus, naïve T cells that exit the thymus and enter the blood stream are self tolerant and self MHC restricted.

Naïve T cells are long-lived resting cells and their rate of attrition is matched by the output of new thymus emigrants [1]. Their survival and slow rate of division is dependent on the recognition of MHC-self peptides and exposure to homeostatic cytokines, such as IL-7 [2]. Fibroblastic reticular cells, a component of lymph node stroma located within the T cell zone, were recently demonstrated to be a major source of peripheral IL-7 [3]. Infection generally results in the massive expansion of naïve T cells bearing a TCR capable of recognizing pathogen-encoded peptide ligands. Many factors influence the magnitude of the developing T cell response, including antigen dose, [4] the duration of antigen presentation [5] and the affinity of the TCR-ligand interaction. Using a panel of Listeria recombinants expressing peptide variants with varying affinity to the OT-I TCR, it was demonstrated that T cells with low avidity for antigen are activated during a primary response. However, they are expelled from lymphoid organs earlier than T cells with higher avidities and thus generate smaller cohorts of effector T cells and subsequently contract into smaller fractions of the memory pool [6]. T cells, unlike B cells do not undergo classical affinity maturation by mutation of their antigen receptors. Nonetheless during the course of the immune response there does appear to be a preferential expansion of T cells bearing the highest affinity TCR which ultimately results in an increase in the overall affinity of the T cell response [7–9].

Following clearance of the pathogen, generally 90–95% of the effector T cell population undergoes Bim dependent apoptosis during the contraction phase. The remaining 5–10% of cells that survive enter the memory pool [10]. What determines if a cell lives or dies? Actively dividing cells are dependent on cytokines such as IL-4, IL-2, IL-7 and IL-15 for survival. During a primary T cell response, as antigen is cleared there is a reduction in the levels of cytokines that support T cell survival. This famine in pro-survival cytokines is thought to drive the death of large numbers of effectors. Indeed, the exogenous introduction of pro-survival cytokines (IL-15 and IL-2) during the contraction phase can increase the size of the developing memory T cell population [11,12]. Conversely, removal of IL-15 receptor from the surface of macrophages results in a more profound loss of effectors [13]. Nonetheless, it has been demonstrated that the fate of effector T cells is predetermined prior to contraction suggesting that competition for limited resources is not the major factor dictating survival. The effector population is heterogeneous, and subsets of effectors that are fated to die can be distinguished from others that contribute to memory [14]. When the number of effector cells competing for survival is artificially increased, this has no effect on the rate or extent of contraction, again arguing that competition for survival factors is not the cause of effector cell death [15].

New flavors of memory

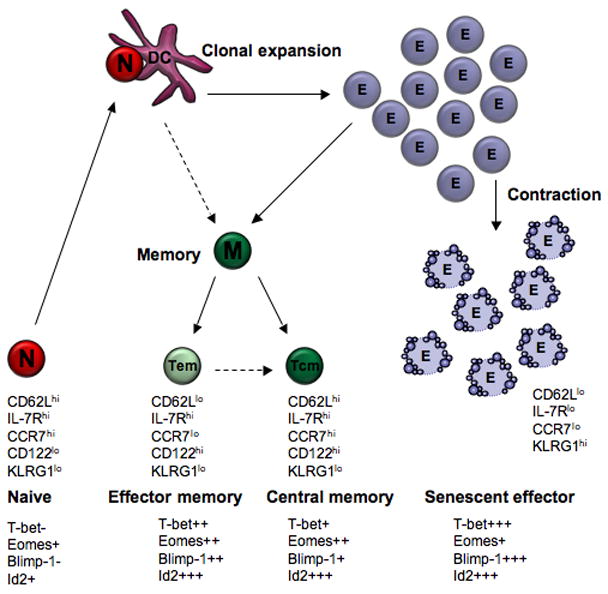

Seminal work by Sallusto and Lanzavecchia introduced the concept that memory T cells are heterogeneous [16]. This was first observed in human blood, although the murine counterparts were discovered soon after. Central memory T cells circulate between secondary lymphoid organs, express the LN homing molecules CCR7 and CD62L, do not exhibit immediate effector functions but can undergo significant recall proliferation upon antigen re-encounter. Effector memory T cells classically lack LN homing molecules and are thus generally deposited in and circulate through peripheral tissues. They exhibit immediate effector function upon antigen recognition (Figure 1) [17]. With time following an infection, the memory pool gradually changes converting from an effector memory dominated pool to a more stable and long lived central memory population. It has been more than a decade since it was first shown that memory T cells come in different flavors, but the past year has seen the characterization of two new memory CD8+ T cell subsets which fall outside the effector and central memory dichotomy.

Figure 1. The changing faces of a T cell as it progresses through various life stages.

Naïve (N) T cells upon interaction with an antigen bearing DCs undergo activation and clonal expansion, forming a large effector (E) T cell pool. The vast majority of effector cells (senescent effector) undergo apoptosis during the contraction phase. Memory (M) T cells are antigen experienced cells that survive the contraction phase and are classically divided into effector (Tem) or central (Tcm) memory. Cell transitions that are still contentious are depicted with a dotted line.

Resident memory T cell (Trm)

It is well appreciated that peripheral tissues house a large proportion of the memory T cell pool [18] although it was thought that these were simply effector memory T cells trafficking through the tissue as part of their immunological surveillance. Carbone and colleagues defined a population of peripherally deposited memory T cells that are both phenotypically and functionally distinct from memory T cells within the circulation - they were coined resident memory T cells (Trm) [19]. Memory CD8+ T cells can persist long term in sensory ganglia harboring latent herpes simplex virus (HSV) [20] as well as in healed HSV skin lesions [19,21]. These cells were shown to be permanently resident within the skin and sensory ganglia. In general, Trm cannot leave the tissue in which they reside and thus have a limited role in protecting a local site from either secondary infection or reactivation of a local latent infection. Their retention appears linked to the up-regulation of certain adhesion molecules which fasten them to the extracellular matrix [22]. Upon secondary encounter with their pathogen Trm rapidly acquire effector function [23] and in certain situations can undergo extensive proliferation in situ in response to antigen presented by inflammatory dendritic cells [24]. The factors maintaining these T cells within the tissue for long periods have yet to be elucidated.

The T memory stem cell (Tscm)

In many ways all memory cells are stem cells. At least, when they are labeled with CFSE, transferred and challenged with antigen they all proliferate. Whether every proliferating memory cell produces effector and memory progeny is not known. The cardinal feature of a stem cell is the ability to self renew. Gattinoni et al [25] demonstrate that CD8+ T cells can acquire stem cell like properties if they receive signaling through the Wnt-β-catenin pathway during activation. Activation of the Wnt signaling pathway in naïve T cells during stimulation impeded T cell proliferation and the acquisition of effector function but the memory population that did form could self-renew and differentiate into various effector and memory CD8+ T cell subsets- this population was termed T memory stem cells (Tscm). Patients receiving repeated bouts of lympho-ablative chemotherapy retain protective T cell memory against EBV and CMV. This finding led Turtle et al [26] to identify a phenotypically and functionally distinct subset of memory T cells, CD161hi, IL-18R+, with high expression of ABC-transporters that conferred resistance to chemotherapuetic drugs. The defined subset exists in the central and effector memory pool. Whether they form a stable subset of memory and have a memory maintenance role outside reconstitution following immune ablation awaits analysis.

Intrinsic factors that govern memory development

Two key transcription factors, T-bet and Eomesodermin (Eomes), greatly influence memory CD8+ T cell development [27,28]. How these transcription factors influence the T cells fate appears linked to their control of the expression of IL-7R and IL-15R [29, 28]. Signaling through these receptors is known to promote memory T cell survival and homoeostasis. Expression of these transcription factors is regulated by inflammatory cytokines, particularly IL-12. Elevated levels of IL-12 promote T-bet expression and suppress eomes expression favoring the development of short lived effector cells. Low levels of IL-12 result in repression of T-bet and expression of eomes this combination of gene expression favors the generation of memory T cells [29,30].

Inhibitor of DNA binding 2 (Id2), was identified as another transcription factor important in memory T cell development. An antagonist of E protein transcription factors, Id2 is upregulated in CD8+ T cells during infection and remains elevated in memory CD8+ T cells. Although Id2-deficient naive CD8+ T cells undergo normal proliferation following pathogen encounter, effector CD8+ T cells exhibited elevated expression levels of Bim and CTLA-4 and reduced levels of Bcl-2 which made these cells more prone to apoptosis [31]. More recently Blimp-1, a transcription repressor, initially identified as a critical regulator of plasma cell differentiation has been linked to T cell homoeostasis and memory development [32, 33]. Blimp-1 promotes the formation of short lived effector cells and promotes the trafficking of these cells into peripheral tissues [34,35].

Where do memory T cells come from?

A study by Stemberger and colleagues demonstrated that the fate of a naïve T cell is not pre-determined prior to activation. Specifically they showed that daughters of a single cell could develop into both effector cells and memory T cells [36]. Whether memory T cells arise directly from naïve T cells or transition through an effector phase prior to adopting their memory status remains controversial. Currently there are two models to describe memory T cell development. The asymmetrical division model proposes that following activation the T cell asymmetrically divides resulting in the unequal distribution of proteins and mRNAs that are important in skewing cell fate [37]. Specifically one daughter, resembles an effector cell which gains cytolytic effector function, loses replicative potential and is doomed to die, while the other daughter displays an opposing phenotype resembling a more quiescent long lived memory cell. Further support for this model comes from Teixeiro and colleagues [38] who introduced point mutations within the TCRβ chain of the OT-I TCR. These mutations had no effect on the development of effector cells during primary challenge although there was severe impairment to the memory T cell pool. The defect was attributed to poor localization of the TCR to the immunological synapse which in turn lead to less downstream NF-κB induction. This work favors a model where effector and memory T cell development represent disparate pathways.

The second model, termed the ‘linear differentiation’ model proposes that memory T cells develop from effector T cells [39]. Support for this linear model of development has surfaced recently with a study by Bennard et al [40] who endeavor to ascertain whether cells expressing the effector molecule granzyme B (or their progeny) can develop into memory cells. Using a transgenic mouse where granzyme B expressing cells are indelibly marked they show that cells expressing an effector phenotype during the primary infection could form functional memory. Furthermore, Harrington et al show that CD4+ T cells expressing IFNγ during the primary response can also progress into the memory phase [41]. Although it seems apparent that cells exhibiting effector function during the primary infection can form memory, whether acquisition of effector function is a prerequisite for a cell to transition into memory is still unclear. The fact that the slow naïve T cell division that occurs under lymphopenic conditions in the absence of pathogen infection results in the differentiation of memory cells might suggest that effector development is not a prerequisite [42,43].

Fading memories?

Every infection severe enough to engage an adaptive immune response alters the composition of the memory T cell pool. Pioneering work by Selin and Welsh demonstrated that subsequent heterologous infections induced the non-specific decay or attrition of pre-existing memory CD8+ T cells [44,45]. It was proposed that over time, following infection by a plethora of pathogens, memory T cells specific for past infections are progressively diluted out by memory T cell populations directed against more recently encountered pathogens. A recent study questioned this paradigm [46]. Using a prime-boost immunization strategy it showed that the size of the memory T cell compartment is not fixed and can indeed increase to accommodate newly established memory populations at no numerical expense to any other T cell subset, naïve or memory. Huster et al [47] corroborated these findings demonstrating very little numerical attrition of a pre-existing Listeria memory CD8+ T cell population following prime-boost vaccination with modified vaccinia Ankara virus. However, the pre-existing memory that persisted was unable to provide immediate protection against high dose Listeria challenge. The defect was attributed to an impairment in killing and cytokine production by effector memory cells. Thus, although subsequent infection may not greatly alter the magnitude of the pre-existing memory pool it may alter its functionality. Although further investigations are clearly warranted to decipher if attrition, either numerical or functional is occurring following repeated bouts of infection, cumulatively these studies highlight an important issue, that is, an individuals immunological history will affect how they combat subsequent infections.

Conclusion

Following activation a naïve T cell has two fates become a senescent effector and die or differentiate into a memory T cell and live. When does this fate decision happen during an immune response and what are the extrinsic and intrinsic factors that govern this decision remain important issues.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hale JS, Boursalian TE, Turk GL, Fink PJ. Thymic output in aged mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8447–8452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601040103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyman O, Purton JF, Surh CD, Sprent J. Cytokines and T-cell homeostasis. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:320–326. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Link A, Vogt TK, Favre S, Britschgi MR, Acha-Orbea H, Hinz B, Cyster JG, Luther SA. Fibroblastic reticular cells in lymph nodes regulate the homeostasis of naive T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1255–1265. doi: 10.1038/ni1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wherry EJ, Puorro KA, Porgador A, Eisenlohr LC. The induction of virus-specific CTL as a function of increasing epitope expression: responses rise steadily until excessively high levels of epitope are attained. J Immunol. 1999;163:3735–3745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prlic M, Hernandez-Hoyos G, Bevan MJ. Duration of the initial TCR stimulus controls the magnitude but not functionality of the CD8+ T cell response. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2135–2143. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6••.Zehn D, Lee SY, Bevan MJ. Complete but curtailed T-cell response to very low-affinity antigen. Nature. 2009;458:211–214. doi: 10.1038/nature07657. This study demonstrates that low af nity antigens can induce effector and memory CD8+ T cell differentiation although due to the more prolonged expansion of high-affinity T-cell clones the pool of T cells progressively matures in affinity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malherbe L, Mark L, Fazilleau N, McHeyzer-Williams LJ, McHeyzer-Williams MG. Vaccine adjuvants alter TCR-based selection thresholds. Immunity. 2008;28:698–709. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner SJ, La Gruta NL, Kedzierska K, Thomas PG, Doherty PC. Functional implications of T cell receptor diversity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:286–290. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kedzierska K, La Gruta NL, Stambas J, Turner SJ, Doherty PC. Tracking phenotypically and functionally distinct T cell subsets via T cell repertoire diversity. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:607–618. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Badovinac VP, Porter BB, Harty JT. Programmed contraction of CD8(+) T cells after infection. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:619–626. doi: 10.1038/ni804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blattman JN, Grayson JM, Wherry EJ, Kaech SM, Smith KA, Ahmed R. Therapeutic use of IL-2 to enhance antiviral T-cell responses in vivo. Nat Med. 2003;9:540–547. doi: 10.1038/nm866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yajima T, Yoshihara K, Nakazato K, Kumabe S, Koyasu S, Sad S, Shen H, Kuwano H, Yoshikai Y. IL-15 regulates CD8+ T cell contraction during primary infection. J Immunol. 2006;176:507–515. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mortier E, Advincula R, Kim L, Chmura S, Barrera J, Reizis B, Malynn BA, Ma A. Macrophage- and dendritic-cell-derived interleukin-15 receptor alpha supports homeostasis of distinct CD8+ T cell subsets. Immunity. 2009;31:811–822. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaech SM, Wherry EJ. Heterogeneity and cell-fate decisions in effector and memory CD8+ T cell differentiation during viral infection. Immunity. 2007;27:393–405. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prlic M, Bevan MJ. Exploring regulatory mechanisms of CD8+ T cell contraction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:16689–16694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808997105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sallusto F, Lenig D, Forster R, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A. Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature. 1999;401:708–712. doi: 10.1038/44385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masopust D, Vezys V, Marzo AL, Lefrancois L. Preferential localization of effector memory cells in nonlymphoid tissue. Science. 2001;291:2413–2417. doi: 10.1126/science.1058867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marshall DR, Turner SJ, Belz GT, Wingo S, Andreansky S, Sangster MY, Riberdy JM, Liu T, Tan M, Doherty PC. Measuring the diaspora for virus-specific CD8+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6313–6318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101132698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19••.Gebhardt T, Wakim LM, Eidsmo L, Reading PC, Heath WR, Carbone FR. Memory T cells in nonlymphoid tissue that provide enhanced local immunity during infection with herpes simplex virus. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:524–530. doi: 10.1038/ni.1718. A study identifying a population of memory CD8+ T cells that reside long term within the skin that is phenotypically and functionally distinct from circulating memory T cells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khanna KM, Bonneau RH, Kinchington PR, Hendricks RL. Herpes simplex virus-specific memory CD8+ T cells are selectively activated and retained in latently infected sensory ganglia. Immunity. 2003;18:593–603. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00112-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu J, Koelle DM, Cao J, Vazquez J, Huang ML, Hladik F, Wald A, Corey L. Virus-specific CD8+ T cells accumulate near sensory nerve endings in genital skin during subclinical HSV-2 reactivation. J Exp Med. 2007;204:595–603. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ray SJ, Franki SN, Pierce RH, Dimitrova S, Koteliansky V, Sprague AG, Doherty PC, de Fougerolles AR, Topham DJ. The collagen binding alpha1beta1 integrin VLA-1 regulates CD8 T cell-mediated immune protection against heterologous influenza infection. Immunity. 2004;20:167–179. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hikono H, Kohlmeier JE, Ely KH, Scott I, Roberts AD, Blackman MA, Woodland DL. T-cell memory and recall responses to respiratory virus infections. Immunol Rev. 2006;211:119–132. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wakim LM, Waithman J, van Rooijen N, Heath WR, Carbone FR. Dendritic cell-induced memory T cell activation in nonlymphoid tissues. Science. 2008;319:198–202. doi: 10.1126/science.1151869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25••.Gattinoni L, Zhong XS, Palmer DC, Ji Y, Hinrichs CS, Yu Z, Wrzesinski C, Boni A, Cassard L, Garvin LM, et al. Wnt signaling arrests effector T cell differentiation and generates CD8+ memory stem cells. Nat Med. 2009;15:808–813. doi: 10.1038/nm.1982. This study demonstrates that signaling through the Wnt-b-catenin pathway may be important for maintaining the 'stemness' of mature memory CD8+ T cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26••.Turtle CJ, Swanson HM, Fujii N, Estey EH, Riddell SR. A distinct subset of self- renewing human memory CD8+ T cells survives cytotoxic chemotherapy. Immunity. 2009;31:834–844. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.015. The authors identify a distinct subpopulation of memory CD8+ T cells with the ability to rapidly efflux and survive exposure to chemotherapy drugs. This population of cells is likely to have an important role in reconstituting an ablated immune system. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pearce EL, Mullen AC, Martins GA, Krawczyk CM, Hutchins AS, Zediak VP, Banica M, DiCioccio CB, Gross DA, Mao CA, et al. Control of effector CD8+ T cell function by the transcription factor Eomesodermin. Science. 2003;302:1041–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1090148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Intlekofer AM, Takemoto N, Wherry EJ, Longworth SA, Northrup JT, Palanivel VR, Mullen AC, Gasink CR, Kaech SM, Miller JD, et al. Effector and memory CD8+ T cell fate coupled by T-bet and eomesodermin. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1236–1244. doi: 10.1038/ni1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joshi NS, Cui W, Chandele A, Lee HK, Urso DR, Hagman J, Gapin L, Kaech SM. Inflammation directs memory precursor and short-lived effector CD8(+) T cell fates via the graded expression of T-bet transcription factor. Immunity. 2007;27:281–295. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takemoto N, Intlekofer AM, Northrup JT, Wherry EJ, Reiner SL. Cutting Edge: IL-12 inversely regulates T-bet and eomesodermin expression during pathogen-induced CD8+ T cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2006;177:7515–7519. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cannarile MA, Lind NA, Rivera R, Sheridan AD, Camfield KA, Wu BB, Cheung KP, Ding Z, Goldrath AW. Transcriptional regulator Id2 mediates CD8+ T cell immunity. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1317–1325. doi: 10.1038/ni1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kallies A, Hawkins ED, Belz GT, Metcalf D, Hommel M, Corcoran LM, Hodgkin PD, Nutt SL. Transcriptional repressor Blimp-1 is essential for T cell homeostasis and self-tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:466–474. doi: 10.1038/ni1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martins GA, Cimmino L, Shapiro-Shelef M, Szabolcs M, Herron A, Magnusdottir E, Calame K. Transcriptional repressor Blimp-1 regulates T cell homeostasis and function. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:457–465. doi: 10.1038/ni1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rutishauser RL, Martins GA, Kalachikov S, Chandele A, Parish IA, Meffre E, Jacob J, Calame K, Kaech SM. Transcriptional repressor Blimp-1 promotes CD8(+) T cell terminal differentiation and represses the acquisition of central memory T cell properties. Immunity. 2009;31:296–308. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kallies A, Xin A, Belz GT, Nutt SL. Blimp-1 transcription factor is required for the differentiation of effector CD8(+) T cells and memory responses. Immunity. 2009;31:283–295. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stemberger C, Huster KM, Koffler M, Anderl F, Schiemann M, Wagner H, Busch DH. A single naive CD8+ T cell precursor can develop into diverse effector and memory subsets. Immunity. 2007;27:985–997. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang JT, Palanivel VR, Kinjyo I, Schambach F, Intlekofer AM, Banerjee A, Longworth SA, Vinup KE, Mrass P, Oliaro J, et al. Asymmetric T lymphocyte division in the initiation of adaptive immune responses. Science. 2007;315:1687–1691. doi: 10.1126/science.1139393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teixeiro E, Daniels MA, Hamilton SE, Schrum AG, Bragado R, Jameson SC, Palmer E. Different T cell receptor signals determine CD8+ memory versus effector development. Science. 2009;323:502–505. doi: 10.1126/science.1163612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wherry EJ, Teichgraber V, Becker TC, Masopust D, Kaech SM, Antia R, von Andrian UH, Ahmed R. Lineage relationship and protective immunity of memory CD8 T cell subsets. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:225–234. doi: 10.1038/ni889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40••.Bannard O, Kraman M, Fearon DT. Secondary replicative function of CD8+ T cells that had developed an effector phenotype. Science. 2009;323:505–509. doi: 10.1126/science.1166831. This paper demonstrates that CD8+ T cells that express granzyme B during the primary response can develop into long lived memory cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41••.Harrington LE, Janowski KM, Oliver JR, Zajac AJ, Weaver CT. Memory CD4 T cells emerge from effector T-cell progenitors. Nature. 2008;452:356–360. doi: 10.1038/nature06672. This paper demonstrates that CD4+ T cells that acquire effector function during a primary response can develop into long lived memory cells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hamilton SE, Jameson SC. The nature of the lymphopenic environment dictates protective function of homeostatic-memory CD8+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:18484–18489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806487105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheung KP, Yang E, Goldrath AW. Memory-like CD8+ T cells generated during homeostatic proliferation defer to antigen-experienced memory cells. J Immunol. 2009;183:3364–3372. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Selin LK, Vergilis K, Welsh RM, Nahill SR. Reduction of otherwise remarkably stable virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte memory by heterologous viral infections. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2489–2499. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Selin LK, Lin MY, Kraemer KA, Pardoll DM, Schneck JP, Varga SM, Santolucito PA, Pinto AK, Welsh RM. Attrition of T cell memory: selective loss of LCMV epitope-specific memory CD8 T cells following infections with heterologous viruses. Immunity. 1999;11:733–742. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46••.Vezys V, Yates A, Casey KA, Lanier G, Ahmed R, Antia R, Masopust D. Memory CD8 T-cell compartment grows in size with immunological experience. Nature. 2009;457:196–199. doi: 10.1038/nature07486. A study demonstrating that heterologous infection does not result in the numerical attrition of pre- existing memory T cells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huster KM, Stemberger C, Gasteiger G, Kastenmuller W, Drexler I, Busch DH. Cutting edge: memory CD8 T cell compartment grows in size with immunological experience but nevertheless can lose function. J Immunol. 2009;183:6898–6902. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]