Abstract

Purpose: To explore dimensions of stigma experienced by older adults with hearing loss and those with whom they frequently communicate to target interventions promoting engagement and positive aging. Design and Methods: This longitudinal qualitative study conducted interviews over 1 year with dyads where one partner had hearing loss. Participants were naive to or had not worn hearing aids in the past year. Data were analyzed using grounded theory, constant comparative methodology. Results: Perceived stigma emerged as influencing decision-making processes at multiple points along the experiential continuum of hearing loss, such as initial acceptance of hearing loss, whether to be tested, type of hearing aid selected, and when and where hearing aids were worn. Stigma was related to 3 interrelated experiences, alterations in self-perception, ageism, and vanity and was influenced by dyadic relationships and external societal forces, such as health and hearing professionals and media. Implications: Findings are discussed in relation to theoretical perspectives regarding stigma and ageism and suggest the need to destigmatize hearing loss by promoting its assessment and treatment as well as emphasizing the importance of remaining actively engaged to support positive physical and cognitive functioning.

Keywords: Grounded theory, Hearing aids, Dyads, Ageism

The ability to relate to others, share ideas, participate in activities, and experience one’s surroundings depends greatly on the capacity to hear. Hearing provides essential information about the environment, including the presence of danger. Sirens, smoke alarms, and warning shouts require hearing. Hearing loss significantly influences this ability to communicate and participate in activities and data document the multiple negative effects it has on the person with hearing loss as well as his or her partner (Arlinger, 2003; Carmen, 2004; Dalton et al., 2003; Morgan-Jones, 2001; Wallhagen, Strawbridge, Shema, & Kaplan, 2004).

At the same time, hearing loss is one of the most common chronic conditions experienced by older adults, with its prevalence reaching almost 50% in those older than 75 years (National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders [NIDCD], 2009). Recent data also suggest that hearing loss may be more prevalent than previously reported, is increasing at younger ages, and that 77% of persons aged 60–69 years may have high-frequency hearing loss (Agrawal, Platz, & Niparko, 2008; Wallhagen, Strawbridge, Cohen, & Kaplan, 1997).

With individuals living longer, the importance of treating hearing loss to facilitate continued social engagement is increasingly important. Furthermore, the functional and psychosocial importance of hearing would seem to provide a strong basis for a desire to correct or ameliorate any loss. Yet only approximately 20% of persons who could benefit from amplification wear a hearing aid (NIDCD, 2009) and few take advantage of other forms of assistive listening devices. Factors suggested as reasons for lack of hearing aid use include cost, perceived lack of benefit, and denial of hearing loss (Carmen, 2004; Clark & English, 2004). But one of the most difficult disincentives to counteract is the perceived stigma associated with hearing loss and use of hearing aids (Carmen; Johnson et al., 2005; Simmons, 2005).

The concept of stigma has a long history originating with the Greeks who used the word to refer to bodily signs that exposed something negative about a person’s moral status (Goffman, 1963). Most current literature, however, refers to Goffman’s own work and his use of the term to mean “an attribute that is deeply discrediting . . .” (p. 3) that can lead to overt or experienced rejection, isolation, judgment, or discrimination (Dobbs et al., 2008; Sandelowski, Lambe, & Barroso, 2004). Even Goffman’s subtitle, “notes on the management of spoiled identity,” connotes the pejorative meaning of the term.

If stigma is an important underlying factor in the denial of hearing loss and rejection of hearing assessment and treatment, a solid understanding of this concept is necessary for developing programs to help older adults and their families better manage hearing loss and promote maximum functioning and quality of life. Yet, although articles regarding stigma’s association with other chronic conditions, such as HIV/AIDS (Holzemer et al., 2007) and mental illness (Peris, Teachman, & Nosek, 2008), can be found in the nursing and medical literature, few data are available on how and why hearing loss and the use of hearing aids are perceived as stigmatizing. The purpose of this article was to explore the dimensions of stigma as experienced and expressed by older adults and those with whom they most frequently communicate. Findings are discussed in relation to theoretical perspectives regarding stigma and ageism and their implications for clinical practice and future research are presented.

Methods

Data are from a longitudinal study using quantitative and grounded theory qualitative methods to explore and understand the experience of hearing loss from the perspectives of both an older adult with hearing loss and his or her communication partner, a designated person with whom the older adult frequently communicated, usually a spouse or partner but sometimes an adult child or close friend.

Participants

Older adults (≥60) who had never worn hearing aids or had not worn them in the past year and who were seeking a hearing assessment were recruited from 32 sites providing hearing services within the San Francisco Bay Area. Four additional participants were obtained through individual referrals. Communication partners were identified by the person with hearing loss. Ninety-one dyads were interviewed at baseline, 87 dyads at 3 months (T2), and 84 dyads at 12 months (T3). Seven dyads were dropped because they could not be recontacted, experienced scheduling problems, moved, or declined further interviews. The mean age of the person with hearing loss was 73 (range 60–93) and the mean age of the communication partner was 64.2 (range including one grandchild, 19–92). Most of the participants with hearing loss were male (57%), Caucasian (90%), and married or partnered (72.5%).

The study was approved by the University Committee on Human Research. After informed consent, both the person with hearing loss and the communication partner were interviewed separately three times: baseline, 3 months (T2), and 12 months (T3). Interviews were audiotape recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Participants were asked to describe their experience with hearing loss, when they recognized the loss, why they decided to obtain a hearing assessment, the meaning of hearing loss to them, how it was affecting their communication with the communication partner or person with hearing loss, whether they were thinking of getting a hearing aid, and how “society” views persons with hearing loss. At follow-up, reasons for getting or not getting and wearing or not wearing a hearing aid were explored along with changes in communication and activities

Data Analysis

Qualitative interviews followed grounded theory, constant comparative methodology with guided interviews that evolved as the ongoing analyses identified emergent themes and concepts that led to additional probes for further refinement and clarification (Charmaz, 2000; Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Throughout the study, field notes and memos were used to capture methodological and theoretical perspectives and identify areas that needed further exploration, the research team met to discuss emerging themes and concepts, and data were compared within and across interviews. Follow-up interviews were used to validate, clarify, and refine emerging concepts. Negative cases were specifically identified to challenge and refine the analyses. Identified concepts and themes were used to code data using NVIVO qualitative software (QSR International, 2008). As data suggested the potential importance of media to the experience of stigma, available marketing materials and commentaries on hearing aids were collected and incorporated into the analytic process. Finally, to further support the credibility and generalizability of the emerging concept of stigma, findings were discussed with colleagues and individuals who worked with persons with hearing loss.

Results

Perceived Stigma—“The Label”

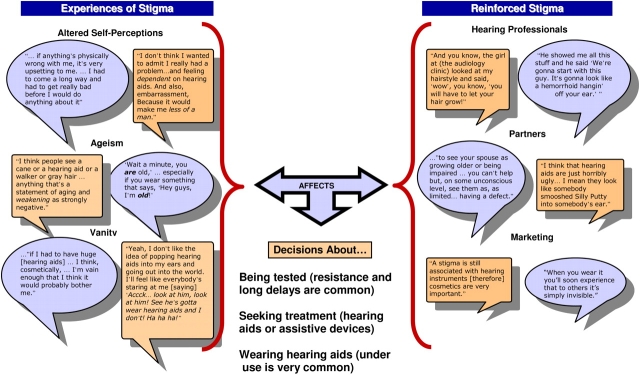

Persons with hearing loss and their communication partners talked about hearing loss from within their larger social contexts and in relation to their self-image or their image of their partner. It was from within this context that perceived stigma emerged as an important theme influencing decision-making processes at multiple points along the experiential continuum of hearing loss. For example, stigma affected the initial acceptance of hearing loss, whether to be tested or seek treatment, the type of hearing aid selected, and when and where hearing aids were worn. Further analyses revealed that stigma was related to three interrelated experiences: alterations in self-perception, ageism, and vanity.

Figure 1 presents a model of the interrelationships among these concepts that are explicated subsequently. Contrasting cases are presented in the context of the important role of supportive relationships and being around similar others.

Figure 1.

The interrelationships among the experience of stigma, reinforced stigma, and its affects.

Alterations in Self-perception.—

Participants discussed how the meaning of hearing loss and hearing aids influenced how they perceived themselves and their partners as well as how they perceived they would be viewed by others. These generally fell into perceptions contrasting being whole versus not whole, able versus disabled, and smart versus cognitively impaired. For example, one participant noted,

Well when you see people that have glasses, and hearing aids, and a cane, you know decrepit is not far from one's vocabulary . . . . And having to admit it by something that's visible externally . . . that's what I mean by a stigma, “Oh, he can’t hear either.” . . . I mean if you had a hearing aid . . . it was hanging right out there . . . that, I’ve got a handicap . . . and I don’t think anyone likes to come right out and say “ . . . I’m handicapped” . . . .

This same participant talked about “faking” hearing so he did not have to admit he did not hear. Another noted when asked to clarify her perspective about the relationship of hearing loss and disability,

Yes I do. I think it is. I don’t like to acknowledge it, you know, and I don’t acknowledge it to a lot of people. I’m acknowledging it to you because of the position you’re in . . . . Cause it's really an ego thing, I guess, you know. You have to admit that you’re deteriorating, and that's not easy to do.

This participant decided not to obtain hearing aids. To support her decision, she rationalized that her hearing was not that bad and that her husband’s voice was really the issue.

These feelings influenced the type of hearing aids considered acceptable, or as another participant noted,

Well, you know . . . one doesn’t like to advertise any kind of physical deficiencies that they have. If they can be disguised in any way, it would be preferable . . . . (interviewer: Well if they could have only fit you with like the over-the-ear or something that was more visible, do you think you would have . . .) I don’t know. If that would have been the only possible choice, whether I would’ve accepted them, I’m not sure . . . . I would probably have thought I’m gonna wait until it's more severe before I get them. If I have to get hearing aids. I don’t think I need them if they’re gonna be ugly, obvious hearing aids.

The stigma experienced by this older cohort may reflect their experiences growing up. One gentleman noted,

. . . you have to remember, my age . . . when I was a youngster certain things were considered to be, you know, stigmas of sort . . . loss of hearing was not as openly accepted.

However, he went on to note that although he thought society in general had gotten more open to physical disabilities, still,

I think even today there are some things that many people in society just recoil to some physical or mental disability. Human nature I guess. And . . . in my case, you know, if I have, in addition to weak eyes, if I have weak ears, oh my gosh! You know, it's another little bit of a handicap that, you know, that you don’t like to talk about.

Another noted how she felt hearing loss “diminishes one's authority” and that authority mattered to her in her work role. She went on to note that she was actually more comfortable telling someone she did not hear them, noting, “I have said ‘I can’t hear you.’ And, which, for some reason, is more comfortable for me to say and it seems to relate to the moment, rather than to a general life condition.” This reflects the way in which compartmentalizing the hearing loss, not allowing it to be considered a true aspect of the self, can influence how individuals manage or cope (Goffman, 1963).

The impact on self led to delay in acknowledging the loss or dealing with it, or as one participant expressed it,

I know I was in denial for a certain period of time. I didn’t want to admit that, I mean, oh my God, I mean, it was, you know, it was just sort of falling apart all of a sudden? . . . . I mean, just like a lot of us in a lot of other situations, you know, go ‘Ah well, don’t have to deal with it today.’

The association of hearing loss and hearing aids with stigma was not confined to the person experiencing the loss. The communication partner’s expressed concerns about how hearing loss and hearing aids were perceived, how they influenced whether the individual was willing to explore treatment options, and what it meant to them in terms of their relationship with the person with hearing loss. Such comments often again reflected the association of hearing loss with a disability or handicap and the desire not to accept “the label.”

She doesn’t wanna draw attention to that aspect of things unless she means to . . . . I think that then becomes a sign “I’m defective” or “I’m hearing impaired,” or, you know, the label.

Another communication partner emphasized similarly that because the person with hearing loss did not want to be part of those labeled as handicapped “their discomfort level has to go high enough so they can overcome those things, whether they want to or not” before they would seek assistance or wear hearing aids.

These perceptions influenced how the communication partner viewed their partner as exemplified by the following self-reflective comment:

. . . you begin to see your spouse as growing older or being impaired in some way, and you know, you can’t help but on some unconscious level, see them as limited, having a limit that they didn’t have before, having a defect in some way . . . we like to believe we don’t think these things, but we do and so that has a subtle influence on how you feel about one another and our relationships . . . my pictures of people who have [hearing aids] are either pictures of very old people ‘Aaey?’ or mentally retarded people, also that have hearing problems. It’s not a pretty social image, the loss of hearing.

These expressions of the perceived stigmatizing effects of hearing loss and its overt recognition through the use of hearing aids highlight the dilemma these participants felt they faced regarding decisions to disclose or not disclose their hearing loss (Goffman, 1963; Sandelowski et al., 2004). Self-disclosure was done to certain individuals and not to others. To cover, persons with hearing loss would “fake it,” “fill in,” or otherwise cover the fact that they did not hear. Although this may often have gone unnoticed, it could lead to embarrassment when the context was misinterpreted:

Sometimes I’ll do it and it’s inappropriate. (interviewer, . . . have you been caught?) Oh, uh . . . funny looks a few times . . . . Like if you’re talking and all of a sudden the person says “Yeah, I love . . . lost my mother and father,” “uh . . . Hey! That’s great! That’s great!” you know, “Oooh!” that’s not good; that happens sometimes. Usually not that bad, but to that degree. They say some negative thing, you say “oh it’s great” because you’re so used to agreeing with that.

How often other instances occurred that were unknown to the individual cannot be ascertained fully, but communication partners occasionally commented on frequent misinterpretations that did occur in conversations. Thus, the stigma of hearing loss may result in alternative labeling when individuals are perceived as not involved or confused.

Ageism.—

Closely related to an altered sense of self was the association of hearing loss with aging and how others viewed older adults. As one participant noted,

It’s not that I’m trying to look or act or be younger than I am, I’m very proud of my years and my experience, but there’s um . . . [pause] there’s a kind of labeling as an old person that I think this appearance causes . . . having the hearing aid is another thing, like my gray hair, that will identify me as an old person.

Another reiterated this feeling, stating, “I guess, don’t want to let on that I’m getting on in years as it were . . . the association of hearing aids with aging . . . . But the stigma is associated with the aging rather than anything else.”

Feeling that hearing aids made them look old influenced how they felt they related to younger individuals.

I guess it’s silly that you don’t wanna admit that you’re any older than you are . . . . Especially with younger friends. I have a lot of younger friends too . . . . It makes you feel like you’re getting old or you’re old. I don’t wanna be old.

Hearing loss was not only viewed as an overall indicator of getting older but also a specific reminder of an aging self. One gentleman who valued his appearance and health noted,

I guess young people have near-sightedness. But hearing loss seems to be affiliated with aging . . . the fact of having a big hearing aid says, I don’t care how you look otherwise, but you’re old . . . . So I like to think that I’m not old. But then the hearing part says “Wait a minute, you are old.” I mean, especially if you wear something that says, “Hey guys, you know, I’m old! I’m an old man,” . . . .

Again, the partners often expressed similar feelings, reinforcing the perception that the person with the hearing loss would be perceived as “an old fogie” within a youth-oriented society. These feelings often were expressed using very strong negative descriptions.

I think people are still . . . remember the old ear trumpets and things, you know, it’s just sort of the image of these doddering old fogies wandering around with a horn sticking out of their ear, that projects the image of age, and, let’s face it, we’re in a youthful society . . . I think hearing aids make you look old.

. . . but hearing aids, people don’t wear hearing aids, generally, unless they’re older, so hearing aids are a sign of age . . . . I don’t think that he would even be considering wearing hearing aids if, if he didn’t think that [he was] a candidate for the in-canal styles. And so I’ve been talking a lot about the invisibility issue . . . . I’ll be very honest with you, I might think twice about wearing a hearing aid if I had short hair and couldn’t cover up my ears with my hair . . . but I think too, this is just my own personal prejudice, I think that hearing aids are just horribly ugly . . . I mean they look like somebody smooshed Silly Putty into somebody’s ear.

Because the decision to obtain a hearing assessment and a hearing aid is embedded in the dyadic relationship, persons with partners who viewed hearing aids as diminishing the hearing loss and making their partner look “old, feeble, or unattractive” may be less likely to be supportive or to encourage follow-through on treatment recommendations. This may be because individuals feel stigmatized by association when they believe they, themselves, will be devalued through their association with a stigmatized individual (Dobbs et al., 2008; Goffman, 1963).

Vanity.—

Related to an altered sense of self was the perception that hearing aids would make them appear unattractive. This is suggested by several of the quotes previously emphasizing the negative views of what hearing aids looked like, but appearance had important implications for the types of hearing aids that might be accepted.

I can’t say that I would like it if I had to have huge ones in, and they showed . . . . I’m vain enough that I think it would probably bother me. I don’t know if the result would be worth it . . . . I think you would probably think people were looking at them or that would be the first thing they notice . . . .

The importance of hiding the aid and not drawing attention to ones ears was emphasized by another woman when she noted.

Well I’m going to be having a hair style that they won’t show . . . . I like long earrings and so I’m thinking to myself, well boy, I don’t know if you want to be calling attention to like your ears, but earrings hang down long, so maybe get them really long and then it will draw attention to my shoulders and not my ears.

Vanity contributed to putting things off.

But somehow hearing aid is associated with aging or maybe it's my vanity that I’m saying no . . . surely there's gotta be something that's gonna be better, that's invisible, and comfortable and all those kinds of things, you know. So I’m waiting for the next solution, but so far we haven’t done anything about it. I do promise her that I will get it . . . .

Denying Stigma—“Get Over It”

Not all participants were influenced by perceptions of stigma, either discounting its importance or noting that it was irrelevant. Yet, even in these situations, the actual presence of stigma was often acknowledged but then put into perspective, rebelled against, or viewed as not relevant within their social circles where so many others also wore hearing aids.

One participant, whose hearing loss significantly affected her ability to participate in activities that were extremely important to her, discussed how she rejected the idea that hearing aids might be stigmatizing while also suggesting they affected her ego.

It’s life. Get over it . . . . I’m irritated by it, and I suppose there’s a little bit of ego thing, “Oh my God, she’s reached a certain point,” . . . [but] that’s somebody else’s problem. It’s their image problem . . . if I was taking insulin, is that a stigma because I’m insulin deficient? . . . . I don’t care, you know. It’s like if it makes me hear better . . . .

Another noted,

I have short hair in the first place and um . . . yeah, I like them small. But if that wouldn’t have been able to be given to me, then I would have bigger ones . . . .

This participant went on to discuss why she believed men were more concerned about stigma but that hearing aids allowed her to hear more, which she wanted. Then, when asked if wearing aids made her feel any different about herself she noted, “I think when you get older you get easier on that. You know, if I would be 30, 40, I think I would be more image oriented than I am at my age now.”

This quote evidences several issues related to stigma. Although denying stigma is an issue for her, she acknowledges its existence and raises an interesting contrast that occurs with aging. It can be freeing—a time of release from the expectations of others—as well as stigmatizing. However, it also suggests the importance of valuing communication and staying engaged. One reason these participants did not care about what the hearing aid looked like is that it helped them hear better. In contrast, often in efforts to minimize the impact of hearing loss, hearing was frequently discounted; conversations, unless specifically informational, were relegated to the categories of “gossip,” “bull shit,” or “chit chat.”

. . . I may just, depends on the nature of the conversation, whether it’s just chit chat or, you know, small talk, or if we’re really having a talk about something significant, whatever I don’t hear, I ask for clarification . . . but most of the conversations, that where I do think I miss something are not what I would consider, you know, they’re just small talk or . . . there’re no major issues being discussed . . . .

Furthermore, rather than promoting hearing aids as an indicator of the desire to stay engaged, stigma and visibility sometimes influenced how hearing aids were introduced.

And she said “Do you mind if the device that you finally choose shows,” and I says “Not at all,” I says “I’m beyond that,” and she says “Oh no,” she says “I have patients who are over 90 and they really don’t want that device to show.” And I thought that was very amusing. We all have vanity, but it expresses in different areas, you know.

This quote provides beginning insights into how society, the media, and health professionals, including hearing specialists, influence the perception and maintenance of stigma.

Media and Professionals—“It’s Simply Invisible”

The concept of stigma is not an individual experience; it is only relevant within the framework of relationships and the ways in which society reacts to and treats those who are stigmatized because it is only within this context that we can experience rejection, isolation, judgment, or discrimination (Major & O’Brien, 2005). Even in his early work, Goffman (1963) emphasized that “a language of relationships, not attributes, is really needed” (p. 3) to understand stigma, emphasizing the socially constructed meaning of the term and the importance of the stigmatized individual accepting or identifying with the label. And as the quotes above document, the perception of stigma was bound up in how these individuals thought others would react to them. They tried to avoid assuming the stigmatizing label, a concept called “stigma consciousness” by Pinel (1999). Hearing aids became “stigma symbols” (Goffman, p. 43) that drew attention to a negative identity.

As Blumer (1969) emphasized, individuals derive meaning from their interactions with others and their environment and react in relationship to this meaning. This is an active dialectic. Thus, it was relevant that participants reported that primary care providers almost never assessed their hearing (Wallhagen & Pettengill, 2008) and sometimes dismissed the importance of hearing loss or related it to “just aging,” although hearing care professionals sometimes would assume that they wanted the smallest least visible aid.

One communication partner put this in perspective when he responded to the follow-up question about whether he thought there was a stigma related to hearing aids:

I think there is, still, yeah. I think they’ll be a time. That’s why the big trend is to get the hearing aids shoved up inside your canal . . . . I don’t think they’d go to so much trouble and expense unless there was a stigma to it.

Another emphasized, “I think loss of hearing is portrayed that way in movies, you know media . . . it’s a common ailment, it just gets associated with aging and loss of function and, you know, death [laughs], eventually. It starts to look like you’re slipping . . . .”

Hearing aid advertisements emphasize their small nature, minimal visibility, and cosmetic appearance, often using pictures depicting attractive models wearing aids that are not noticeable while emphasizing, “when you wear it you’ll soon experience that to others it’s simply invisible.” The perceived association of hearing aids with stigma was often actively acknowledged. For example, professional trade journals referred to stigma as a factor influencing purchasing decisions. One editorial discussing the issue of hearing aid use in a difficult economic environment noted that persons who might not have considered hearing aids before because of the stigma associated with their use might now be candidates for “discreet modern fittings” to remain competitive in the workforce (Kirkwood, 2008). Although such advertisements and acknowledgments address a perceived reality and may enhance the chances of individuals deciding to seek treatment, they also reinforce the idea that hearing loss and use of hearing aids are stigmatizing and should be hidden.

Supportive or Nonsupportive Others

As the quotes from communication partners noted earlier suggest, partners are often complicit in the perception of stigma. The fact that individuals are situated in their environments and affected by the subtle behaviors of those with whom they are close, having a spouse or partner who perceives hearing aids in a negative way can influence decisions in subtle ways, including not providing active support for obtaining aids.

In one instance, a wife spoke compellingly about how her husband’s hearing loss was affecting her and their relationship but then went on to express her negative views about aids and their appearance and what they meant to her. Her husband also perceived them negatively and did not get aids. His wife, at the second interview, rationalized about why this was okay, how she was adapting, and that, really, the loss and problems were not that significant.

The impact of stigma influenced what was considered “supportive” behaviors. Few dyads seemed to discuss the hearing loss and its treatment as a couple. When asked, communication partners would note that they did not know what the person with hearing loss thought about the hearing aid but rather speculated from what they could observe. The sensitivities experienced by the person with hearing loss also made the communication partner realize that this subject was “taboo” and that they “could not push too hard.” As one communication partner noted,

He’d get angry and there’s no reason to make him angry too. One of us being angry is enough. He doesn’t wanna be reminded . . . that he’s not hearing something. Nobody wants to be reminded of that kind of thing.

Another noted how she was careful about what she said to protect their relationship,

. . . you can make them aware of something, but then it is . . . the ball is in their court. And so what they want to do with it, that’s up to them, right? Well that’s my feeling about it . . . you can’t be pushy about it, it’s just not the right thing for a relationship.

Similarly, one gentleman noted that when he and his spouse had issues related to communication, he was the one who would generally apologize, noting that he did not want to “add insult to injury,” as if this would force an acknowledgment of a stigmatizing condition.

In addition, whereas another suggested the potential importance of having someone talk about the hearing loss by noting, “Like it’s realistic and it’s a good idea,” she then went on to acknowledge the potential reason others might not bring the issue up; “you know, only your best friend will tell you have bad breath or bad hearing . . . .”

In contrast, a supportive environment could facilitate a decision to move forward and explore options. One gentleman noted that he was not going to get hearing aids because he was too old—it was not worth it. But his children commented about how important it was to be able to speak with him. Seeing the decision as important to his family, including his wife, he got and used hearing aids. Another women noted,

Well, I’m in a unique situation . . . my whole life is in a circle of women who are close to my age and who are extremely supportive and extremely not-at-all ageist . . . it’s really just sort of out in the public, where I’m anonymous, . . . . I see people . . . condescending to old people and ignoring old people, so that labeling makes me vulnerable to those kinds of reactions in the public where people don’t know who I am. But, most of my life is spent in a community in which aging is honored, so, I’m lucky.

Being surrounded by supportive others allowed individuals to feel comfortable in wearing hearing aids and not feel they would be judged or ignored.

Discussion

These data support the pervasiveness of perceived stigma associated with hearing loss and use of hearing aids and their close association with ageism and perceptions of disability. They also identify the potential influence of media and advertisements on maintaining hearing loss and hearing aids as stigmatizing. At the same time, they raise several issues that need further study and suggest possible ways to minimize stigma and promote hearing health.

Because only adults aged 60 years and older were included, it could be argued that the younger generation will be less adverse to using advanced technology. Nemes (2007) suggests that with the new designs and functionality of hearing aids, “. . . a convergence of technology centering on the mobile phone may lead to a blurring of the lines between ear-level hearing devices that make communication more convenient and those that provide either a little boost or full-fledged assistance for the hearing-impaired consumer” (p. 17). However, this statement still assumes the hearing assistive technology is not visible, not that it is more acceptable to acknowledge hearing loss. Furthermore, there is currently minimal data suggesting that hearing loss is less stigmatizing for younger individuals. Young adults with hearing loss continue to report its impact on their relationship with peers, self-concept, and willingness to self-disclose (Holkins, 2008; Kelley, 2008). Recent data also suggest that hiring discrimination continues to be directed at persons with hearing impairment (McMahon et al., 2008). Furthermore, Amlani (2009) noted that “if hearing aids were given away by the government at no cost to the user, then 65% of the hearing impaired population would decline the offer” (p. 12). These data thus have ongoing relevance to understanding stigma in hearing loss.

In discussions of stigma, however, current literature usually focuses on the issues of labeling, stereotyping, and types of stigma. Few deal with the actual basis for the social construction of the stigma itself. The reasons for perceived stigma in many health-related situations are multifactorial, but with hearing loss, it is tightly related to the interactive effects of ageism, the negative connotations given to being disabled, and a youth- and appearance-focused society.

The term “ageism” was coined by Butler (1975) who defined it as, “a process of systematic stereotyping of and discrimination against people because they are old” (p. 894). Although frequently acknowledged, ageism still remains an ongoing concern (Butler, 2008). A recent reevaluation of Palmore’s Facts on Aging Quiz suggested that, at least within first year medical students, negative perceptions of aging persist and that some attitudes actually may have worsened (Unwin et al., 2008). Because all are destined to become old if they live long enough, it may be important to consider why individuals reflect negatively on what could be their future selves and why ageism and a focus on youth are difficult to eliminate.

One perspective that integrates the concepts of ageism and a focus on a capable and youth appearing self is Terror Management Theory (Martens, Goldenberg, & Greenberg, 2005; Martens, Greenberg, Schimel, & Landau, 2004; Rosenblatt, Greenberg, Solomon, Pyszczynski, & Lyon, 1989). Terror Management Theory is based on the existential dilemma posed by being mortal but also being consciously aware of this ultimate outcome. To deal with the feelings generated by this awareness, humans strive to give the world and themselves meaning by both investing in a cultural worldview and establishing and maintaining a sense of self-esteem. Thus, Martens and colleagues (2004, 2005) argue that because aging and older individuals raise our awareness of our mortality, we attempt to distance ourselves from them. The relevance of this perspective was alluded to by Butler (1975) when he noted that “ageism is a thinly disguised attempt to avoid the personal reality of human aging and death” (p. 894). Reminders of our own mortality promote attempts to live up to cultural standards, such as appearing young and vital.

If ageism and a focus on youth are partly determined by concerns about death that are dealt with by distancing oneself from reminders, strategies to minimize the concerns may need to focus on building more positive cultural norms and stereotypes of older adults and enhancing the self-esteem relevance of health behaviors (Goldenberg & Arndt, 2008), such as the use of technology to enhance communication to stay active and engaged. Because social categorizations that produce stigmatized groups are socially embedded and constructed, they are amenable to change through enhanced understanding (Giles & Reid, 2005; Kite, Stockdale, Whitley, & Johnson, 2005). Approaches would include supporting a positive image of hearing aid use and the importance of maintaining communication and connection to others to facilitate engagement in activities that promote positive aging. For example, currently few health care practitioners assess hearing loss. By building in routine screening and referral, the value of hearing loss as a component of overall health and well-being would be emphasized. Advertisements for hearing loss could further emphasize the value of communication, whereas media in general could use a greater number of persons with hearing loss across the life span, emphasizing that hearing loss affects a wide range of individuals across all age groups and occupations. The latter would also provide an opportunity to present the range of adaptive assistive listening devices available to facilitate communication, thus increasing awareness.

At the same time, additional research is needed regarding the influence of the dyadic relationship. There are few data on the experience of stigma by the partners of persons with hearing loss, on the impact of stigma contagion or stigma by association in this context, or on the impact of a partner’s perceived stigma related to hearing loss and hearing aids on the behavior of the individual with hearing loss. An understanding of these dynamics would support programs and interventions for dyads. Research is also needed on cultural issues influencing the experience of hearing loss and the use of hearing aids. Although recruitment for the current study involved a wide range of hearing centers, few minorities were in the final sample. This may reflect the lower prevalence of hearing loss among African Americans (Agrawal et al., 2008) but may also reflect cultural views and financial limitations.

In summary, data from the current study document the pervasive nature of stigma in relationship to hearing loss and hearing aids and the close association of this stigma to ageism. Strategies to minimize stigma, including valuing hearing loss by enhancing its assessment and treatment as well as emphasizing the importance of remaining actively engaged, are needed to help older adults and their families maintain positive physical and cognitive functioning.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institute on Nursing Research, R01NR8246.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges Dr. William Strawbridge for his significant feedback and assistance on the manuscript. I acknowledge Dr. Elaine Pettengill and both Karin Luikart and Kay Bolla for their individual thoughts on the concept and to David Geller for his assistance in transcription.

References

- Agrawal Y, Platz EA, Niparko JK. Prevalence of hearing loss and differences by demographic characteristics among US adults. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008;168:1522–1530. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.14.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amlani AM. It's not immoral to increase hearing aid prices in an inelastic market. Hearing Review. 2009;16(1):12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Arlinger S. Negative consequences of uncorrected hearing loss—A review. International Journal of Audiology. 2003;42(Suppl. 2):S17–S20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumer H. Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Butler RN. Psychiatry and the elderly: An overview. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1975;132:893–900. doi: 10.1176/ajp.132.9.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler RN. Combating ageism. International Psychogeriatrics. 2008;1:1. doi: 10.1017/S104161020800731X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmen R. Hearing loss and hearing aids: A bridge to healing. 2nd ed. Sedona, AZ: Auricle Ink; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructivist methods. In: Denzin N, Lincoln Y, editors. Handbook of qualitative research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. pp. 505–535. [Google Scholar]

- Clark JG, English KM. Counseling in audiologic practice: Helping patients and families adjust to hearing loss. Boston: Pearson Education; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton DS, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein BE, Klein R, Wiley TL, Nondahl DM. The impact of hearing loss on quality of life in older adults. The Gerontologist. 2003;43:661–668. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.5.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs D, Eckert JK, Rubinstein B, Keimig L, Clark L, Frankowski AC, et al. An ethnographic study of stigma and ageism in residential care or assisted living. The Gerontologist. 2008;48:517–526. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.4.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles H, Reid SA. Ageism across the lifespan: Towards a self-categorization model of ageing. Journal of Social Issues. 2005;61:389–404. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory. Chicago: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg JL, Arndt J. The implications of death for health: A terror management health model for behavioral health promotion. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;115:1032–1053. doi: 10.1037/a0013326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holkins P. The road to acceptance. Hearing Loss Magazine. 2008;29(5):10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Holzemer WL, Uys L, Makoae L, Stewart A, Phetlhu R, Dlamini PS, et al. A conceptual model of HIV/AIDS stigma from five African countries. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;58:541–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CE, Danhauer JL, Gavin RB, Karns SR, Reith AC, Lopez IP. The “Hearing Aid Effect”: A rigorous test of the visibility of new hearing aid styles. American Journal of Audiology. 2005;14:169–175. doi: 10.1044/1059-0889(2005/019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley B. This kid is intense. Hearing Loss Magazine. 2008;29(6):10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood DH. Thinking positively about ’09. Hearing Journal. 2008;61(12):4. [Google Scholar]

- Kite ME, Stockdale GD, Whitley BE, Jr, Johnson BT. Attitudes toward younger and older adults: An updated meta-analytic review. Journal of Social Issues. 2005;61:241–266. [Google Scholar]

- Major B, O’Brien LR. The social psychology of stigma. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56:393–424. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens A, Goldenberg JL, Greenberg J. A terror management perspective on ageism. Journal of Social Issues. 2005;61:223–239. [Google Scholar]

- Martens A, Greenberg J, Schimel J, Landau MJ. Ageism and death: Effects of mortality salience and perceived similarity to elders on reactions to elderly people. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004;30:1524–1536. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon BT, Roessler R, Rumrill PD, Jr, Hurley JE, West SL, Chan F, et al. Hiring discrimination against people with disabilities under the ADA: Characteristics of charging parties. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2008;18:122–132. doi: 10.1007/s10926-008-9133-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan-Jones RA. Hearing differently: The impact of hearing impairment on family life. London: Whurr; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Quick statistics. 2009. Retrieved March 6, 2009, from http://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/statistics/hearing.asp. [Google Scholar]

- Nemes J. As communication technologies converge, dispensers have new opportunities. Hearing Journal. 2007;60(2):17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Peris TS, Teachman BA, Nosek BA. Implicit and explicit stigma of mental illness links to clinical care. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2008;196:752–760. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181879dfd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinel EC. Stigma consciousness: The psychological legacy of social stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76:114–128. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International. NVIVO 8. Melbourne, Australia: Author; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt A, Greenberg J, Solomon S, Pyszczynski T, Lyon D. Evidence for terror management theory: I. The effects of mortality salience on reactions to those who violate or uphold cultural values. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57:681–690. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.57.4.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M, Lambe C, Barroso J. Stigma in HIV-positive women. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2004;36:122–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons M. Hearing loss: From stigma to strategy. London: Peter Owen; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded Theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Unwin BK, Unwin CG, Olsen C, Wilson C. A new look at an old quiz: Palmore's Facts on Aging Quiz turns 30. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56:2162–2164. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallhagen MI, Pettengill E. Hearing impairment: Significant but underassessed in primary care. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2008;34(2):36–42. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20080201-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallhagen MI, Strawbridge WJ, Cohen RD, Kaplan GA. An increasing prevalence of hearing impairment and associated risk factors over three decades of the Alameda County Study. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87:440–442. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.3.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallhagen MI, Strawbridge WJ, Shema SJ, Kaplan GA. Impact of self-assessed hearing loss on a spouse: A longitudinal analysis of couples. Journals of Gerontology: B Psychological Science Social Science. 2004;59:S190–S196. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.3.s190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]