Abstract

Objective

To determine whether community populations in Community Popular Opinion Leader (C-POL) intervention venues showed greater reductions in sexual risk practices and lower HIV/STD incidence than those in comparison venues.

Methods

A 5-country group-randomized trial, conducted from 2002 to 2007, enrolled cohorts from 20 to 40 venues in each country. Venues, matched within country on sexual risk and other factors, were randomly assigned within matched pairs to the C-POL community intervention or an AIDS education comparison. All participants had access to condoms and were assessed with repeated in-depth sexual behavior interviews, STD/HIV testing and treatment, and HIV/STD risk reduction counseling. Sexual behavior change and HIV/STD incidence were measured over two years.

Results

Both intervention and comparison conditions showed declines of approximately 33% in risk behavior prevalence and had comparable disease incidence within and across countries, target populations, and types of venues.

Conclusions

The community-level intervention did not produce greater behavioral risk and disease incidence reduction than the comparison condition, perhaps due to the intensive prevention services received by all participants during the assessment. Repeated, detailed self-review of risk behavior practices coupled with HIV/STD testing, treatment, HIV risk reduction counseling, and condom access can themselves substantially change behavior and disease acquisition.

Keywords: group-randomized clinical trial, HIV, behavioral intervention, community norms, sexually transmitted disease

Introduction

Over 33 million persons worldwide are living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection or acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS).1 The vast majority live in developing, resource-poor countries or in regions undergoing difficult social transitions, and most of the world’s HIV infections are contracted through unprotected sex. Interventions that reduce levels of high-risk behavior in vulnerable community populations are essential for primary public health HIV prevention efforts.

Behavioral interventions to reduce transmission of HIV and sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) have often taken the form of individual counseling. However, a program of research based on diffusion of innovation theory2 has also shown that training and engaging the “popular opinion leaders” of high-risk populations to personally endorse HIV-risk prevention through messages to others can change norms for HIV-related risk behavior in a population. This intervention approach has been found successful with community populations of gay men,3 African American men who have sex with men (MSM),4 and women5 in the United States, but has not been systematically tested in developing countries with high HIV and STD incidence.

Between 2002 and 2007, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial Group conducted the first large, international, multisite study designed to evaluate rigorously the outcomes of a community-level HIV prevention intervention in five countries with different populations vulnerable to the disease. Twenty to 40 venues, social congregating points for high-risk populations, in each country were selected using data from an ethnographic study. This paper presents the Trial’s primary outcomes.

Methods

Trial Methodological Overview

Study sites in China, India, Peru, Russia, and Zimbabwe each implemented a common intervention trial protocol with an at-risk community population for which high behavioral risk or HIV/STD prevalence had been verified through epidemiological studies. Each country site conducted in-depth risk behavior assessment interviews at baseline and 12-month and 24-month follow-up points with longitudinal cohorts of 40 to 188 participants recruited in each of the 20 to 40 community venues per country. HIV and STD testing, manual-based counseling, and treatment of incident cases took place at each assessment point, and condoms were available to all study participants. Following baseline data collection, pairs of venues in each country were matched and randomized to either receive an AIDS education comparison condition or an experimental intervention consisting of the AIDS education activities and the community popular opinion leader (C-POL) intervention. The Trial was designed to determine whether the community populations in venues that received the C-POL intervention showed greater reductions in their sexual risk practices and had lower HIV/STD incidence than community populations in comparison condition venues between baseline and final follow-up. The study was approved by the institutional review boards (IRBs) at each participating U.S. and host country institution.

Although the trial’s design and methods are briefly described here, a more thorough description was published in a special issue of AIDS. That issue provides an extensive overview of the trial’s methods,6 followed by nine articles describing specific aspects of the study in detail.7-15

Study Venues

The Trial was conducted in community venues that were social congregating points for a high-risk population in each country because this intervention requires informal opportunities for conversations during which the trained C-POLs can deliver messages endorsing HIV/STD prevention. A preliminary ethnographic study identified social gathering points at each country site, and an epidemiological study established that initial levels of STDs or high-risk sexual behavior were sufficiently high to be able to detect meaningful change over time, as well as to determine sample size requirements for the main Trial.6,11 Venues were also selected based on presence of population members from the local area, nontransience, geographic separation from another study venue, opportunities for C-POLs to informally talk with others, and community support for the study.

In three countries, a venue was a physical structure in which population members lived (trade school dormitories in St. Petersburg, Russia), drank alcohol and socialized (wine shops in Chennai, India), or worked (vendor markets in Fuzhou, China). In the other two countries, a venue was defined as a neighborhood setting such as barrios in Peru and growth point neighborhoods in rural Zimbabwe. Study venues and populations in each of the five trial countries are described in a previously published paper.7

Study Populations and Recruitment

To be eligible for study participation, individuals recruited in a study venue needed to report that they: (1) were regularly present in that venue and (2) planned to remain in the area for at least two years. China excluded participants who reported having no sex in the six months prior to baseline unless an STD was present at baseline. Peru excluded participants who reported having no sex during the six months prior to baseline. Participants were excluded in all countries if they could not give informed consent or if they had a serious cognitive or communication disability that would preclude study participation. The core age of the participants in the five countries was 18 to 30 years. Because populations were selected based on risk behavior and STD prevalence rather than age, site-to-site age variation was planned. The average number of participants per venue ranged from 92 in Russia to 185 in Zimbabwe.

Each participant provided written, signed, voluntary informed consent and completed all baseline assessment study procedures including the behavioral interview; provision of blood specimens, urine specimens and vaginal swabs for STD/HIV testing; and counseling in HIV risk-reduction.

Intervention

For ethical reasons, participants in both the intervention and comparison conditions received substantial and similar access to prevention services throughout the study.

Comparison condition procedures

In comparison condition venues, HIV/STD prevention brochures and pamphlets, educational materials, and information about HIV/STD counseling, testing, and treatment were visibly placed and maintained. Free or inexpensive condoms were also available in or near each venue. Three times during the study (baseline, 12 and 24 months), research participants were tested for HIV and five other STDs, and, if positive, were treated or referred for treatment. As part of this process, research participants received extensive HIV/STD pre- and post-test counseling according to a detailed interview protocol. They also were interviewed at each of the three assessment times for approximately 45 minutes about their sexual risk behavior, alcohol and drug use, symptoms of illness, and health seeking behaviors.

Intervention condition procedures

Participants in C-POL intervention venues received all of the same services and also the community-level intervention. This intervention is grounded in principles from the theory of the diffusion of innovation which posits that innovations and changes often originate with a subset of the population who are its opinion leaders and whose views are adopted by others in the community.2 Through this process, social norms about HIV/STD risk reduction behaviors could change.

In this study, C-POLs, were identified as natural leaders in each intervention venue based on study staff ethnographic observations, nominations by venue gatekeepers and other key informants, nominations by other population members, or self-nomination. Approximately 15% to 20% of the total target population in the venue was selected as potential C-POLs and invited to attend a series of 4 to 5 small group training sessions led by two study staff facilitators. Skills training-based sessions taught C-POLs basic information about HIV and STDs and how to deliver theory-based HIV/STD prevention messages to others. The sessions used facilitator instruction, modeling, and role play practice to help C-POLs refine their skills for educating friends about risk, recommending risk reduction behavior changes, and personally endorsing the benefits of taking such risk reduction steps. C-POLs also wore logos on t-shirts, hats, or other apparel to stimulate conversations with friends and neighbors.

Because the intervention was implemented across multiple, varied cultures and differing HIV/AIDS risk circumstances, the specific content of C-POL prevention messages were tailored by country and by population. However, training always taught C-POLs to convey messages to others that provided AIDS-related knowledge and information on risk reduction steps; suggested skills or strategies that the message recipient could use to reduce risk; instilled positive attitudes and confidence for using condoms or avoiding unprotected sex; and personally endorsed the benefits and importance of making or attempting to make risk reduction behavior change. Although these message content areas were emphasized in C-POL training across all sites, C-POLs were encouraged to formulate and deliver risk reduction measures using language and vernacular comfortable to them and in styles congruent with their culture. Core elements of the intervention, C-POL training modules, and procedures used to tailor the intervention across cultures and populations are more fully described elsewhere. 8,9,13

C-POLs agreed to deliver HIV/STD prevention endorsement messages during everyday conversations with friends and acquaintances following these group training sessions, which were usually held weekly. Outcomes of conversations were reviewed in subsequent meetings with C-POLs, and any problems encountered were discussed. Reunion sessions were held after the main training phase to encourage C-POLs to continue these conversations to diffuse HIV/STD prevention messages and to instill a sense of being part of a social movement.

Assessment

Study outcomes were measured with assessments of sexual risk behaviors and the testing of biologic specimens for six STDs including HIV infection.

Sexual risk behavior assessment

Demographic characteristics and sexual risk practices during the past 3 months were assessed at baseline and at 12- and 24-month follow-up points in private, individual, computer-assisted personal interviews (CAPI) administered by a trained interviewer and lasting about 45 minutes. At each interview, participants were asked to report on their total number of vaginal and anal intercourse acts, as well as the number of times when a condom was used during intercourse acts during the 3-month recall period. Additionally, specific information of this type was requested for up to five of the participant’s most recent sexual partners during the 3-month recall period. Participants also labeled the type of relationship with each partner (i.e., spouse, cohabiting, casual, new, commercial) to distinguish between spousal or live-in partners and partners of other types. Follow-up interviews measured participant exposure to the community-level intervention. All interviews were conducted in the language of the site’s target population (Mandarin, Tamil, Spanish, Russian, Shona, or Ndebele), refined through processes of translation and back translation, and certified as culturally appropriate by local experts.

Biological assessment

Participants provided blood and urine specimens at each assessment point, and females additionally were asked for vaginal swab specimens. Testing in a study-certified local laboratory was performed to assess HIV, herpes simplex virus-type 2 (HSV-2), syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and trichomonas (women only) using standard laboratory procedures. A complete discussion of these procedures is presented elsewhere.6,12

All non-viral STDs were treated following guidelines of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the World Health Organization, or were referred for treatment based on national best practice guidelines. People found to be HIV-infected were referred for follow-up care at existing local treatment centers. STD treatment was also offered for primary sexual partners of infected individuals. According to protocol, participants were to be informed of their HIV and STD test results within four weeks. Counseling concerning HIV/STD risk reduction was provided for approximately 15 to 20 minutes to each participant at the time specimens were collected and when test results were returned. Persons found to have an STD or HIV infection often received further personalized risk reduction counseling when they received treatment.

Randomization

Venues were matched within each country based on rates of STD prevalence observed in epidemiological studies that preceded the main trial. In addition, city was used to stratify venues before matching in Peru, and area of country and language were used to stratify venues before matching in Zimbabwe. Following administration of the baseline assessment to all participants within each matched pair of venues, the DCC randomized one venue of the pair to the intervention condition and the other to the comparison condition.

Statistical Power

General considerations

The data from the epidemiological studies were used to determine sample size and to estimate power for detecting effects within and across countries using the primary biological and behavioral endpoints. Specific power calculations provided by Murray16 for group-randomized cohort designs were used to compute the sample sizes (e.g., number of venues and number of participants per venue) for each country.

Within-site sample sizes

The study was designed so that each country would have at least 80% power to detect the relevant effect for either the primary biological or the primary behavioral endpoint (based on site-specific risk data from the epidemiological studies) and operating with a Type I error rate (2-sided) of 5%. Sample sizes were computed to detect a 33% lower STD incidence in the intervention (I) versus the comparison (C) venues for the biological endpoint and a 10% absolute difference in the change in high-risk sexual behavior between I and C venues for the behavioral endpoint. The calculations assumed that 20% of the study participants in the cohort were C-POLs and would be excluded from the primary analysis. A detailed description of the number of venues in each site (country) and the power calculations for within site and across sites was published previously.6

Primary Endpoints

Two primary outcomes were used to determine efficacy in the Trial, one behavioral and one biological. The primary behavioral outcome was defined as the change between the 24-month follow-up assessment and baseline in the proportion of participants reporting unprotected acts with non-spousal/non live-in partners in the past 3 months. The 24-month time period was chosen to measure long-term change, while the 3-month recall interval at each assessment was brief enough to minimize recall bias.

The primary biological outcome was the incidence of any new STD, including chlamydia, gonorrhea, HIV, HSV-2, syphilis, and—for women—trichomonas observed across the 12-month and 24-month follow-up points. The pathogenesis, treatment, and transmission dynamics of each of these STDs varies, as well as the sensitivity and specificity of each of the assays. For each participant, a composite binary variable was constructed to indicate whether or not a new case of at least one of the 6 STDs was detected at either follow-up visit. Individuals with Chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and trichomonas were to be treated following positive test results at their baseline, 12-, and 24-month follow-up assessments as specified in the protocol. HIV and HSV-2 cannot be eliminated. Thus, an individual was classified as having a new case of any of the six infections during follow-up if there was a positive test for Chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, or trichomonas (and evidence of treatment for prior positive cases), HSV-2 (if negative at baseline), or HIV (if negative at baseline). Otherwise, an individual was classified as negative for the composite if at least two-thirds of the tests used in the individual’s assessment were available (i.e., negative, but not missing). If there was no new positive test and more than a third of the individual’s tests were missing (not done or indeterminate), the composite variable was set to missing. The primary biologic outcome was unable to be determined for approximately 12% of participants, most of whom were not tested at either follow-up assessment. Less than one percent of participants were missing the outcome because they had some, but fewer than two-thirds, of the required test results.

Quality Control/Quality Assurance (QC/QA) Procedures

The Trial established and implemented well-defined quality control (QC) procedures to ensure consistency over time, and it employed careful cross-site QA monitoring procedures to ensure fidelity to the protocol in the areas of ethnography, assessment, intervention delivery, laboratory test procedures, and STD treatment. QC procedures entailed development of protocols and procedural manuals for all cross-site activities, central training of key site personnel, certification of field and laboratory personnel upon completion of training, and detailed procedures to maintain fidelity of intervention delivery .QA assurance procedures included external QA monitors from the DCC that documented implementation of the ethnographic assessment, intervention, laboratory and data maintenance activities at all study sites.6

Statistical Analysis

Analysis of the primary endpoints was conducted within each of the five countries separately and across all countries. Data from participants in the intervention venues who had been C-POLs were excluded from the primary analysis but included in a secondary data analysis. Because an intent-to-treat analysis was used, any venue assigned to the intervention was considered treated. Data collected between 10 and 18 months after the baseline interview were used as the 12-month assessment, and data collected between 19 and 31 months after baseline were used as the 24-month assessment. The test statistic within a country was taken as the average difference, I minus C, across venue pairs with equal weight to each pair. For the biologic outcome, differences between I and C venues were computed as the percent of participants with a new STD detected at either the 12- or 24-month follow-up visit. For the behavioral outcome, differences between I and C venues were calculated as the change in the percent of participants who reported unprotected sex with a non-spousal/non live-in partner between the 24-month follow-up and baseline. The across-country statistic was the average of these country-specific average differences with equal weight to each country. Hypotheses regarding the study endpoints within each country and across countries were evaluated using permutation tests. Thus, tests were based simply on the randomization of venues within venue pairs to the I or C condition. Statistical significance was computed by considering all possible values each test statistic could have taken by permuting the random assignment of venues within venue pairs. Under the null hypothesis of no difference between I and C, the statistical significance of the observed result was taken as the rank of the observed statistic among the possible permutations. P-values reported are 2-sided. Permutation test-based 95% confidence intervals within each country are also given for the test statistics using a method described by Gail.17 Additional detail is available on request.

In secondary analyses, the C-POLs were included in the data, and hypothesis testing was repeated for both endpoints based on test statistics as defined above. For both the primary biologic and behavioral endpoints, comparisons between I and C venues were made with adjustment for baseline differences. Variables used for adjustment were chosen by examining associations between baseline characteristics and each outcome at the level of the individual using logistic regression models for each country separately. Indicator variables for the venue pairs and the baseline value of the dependent variable were included in all models and a backward elimination procedure was used to select baseline variables associated with the outcome with a significance level of p=0.05 for remaining in the model. A table describing the variables evaluated and selected is available on request. The final country-specific models were used to compute a predicted probability of the behavioral outcome and the biologic outcome for each individual in the country without regard to study condition. The residuals were then used as adjusted outcomes for permutation test-based analysis of study condition differences.17

Additional secondary behavioral and biologic outcomes were defined, and differences between I and C venues were evaluated using test statistics and hypothesis testing based on permutation tests as for the primary outcomes. First, the distribution of the number of episodes of unprotected sex with a non-spousal partner reported at baseline was examined in each country, and an upper percentile of the distribution was chosen in each country. (The median number of episodes was 0 in most countries.) The hypothesis of no difference between I and C venues in each country on the change between baseline and 24 months in the percentile value was tested. Another secondary biologic outcome was defined as any new STD during the second follow-up period only (between 12 and 24 months). Further, hypothesis testing was conducted for individual biologic outcomes in countries where incidence rates during the follow-up period were large enough for each disease. Finally, model-based analyses were also conducted using longitudinal models that utilize a generalized estimating equation (GEE) approach for variance estimates.

Descriptive statistics at baseline and follow-up by condition were computed to give equal weighting to each venue within country and to each country for summarization across countries. The associated standard errors take into account random effects for the individual participant and the venue.

Results

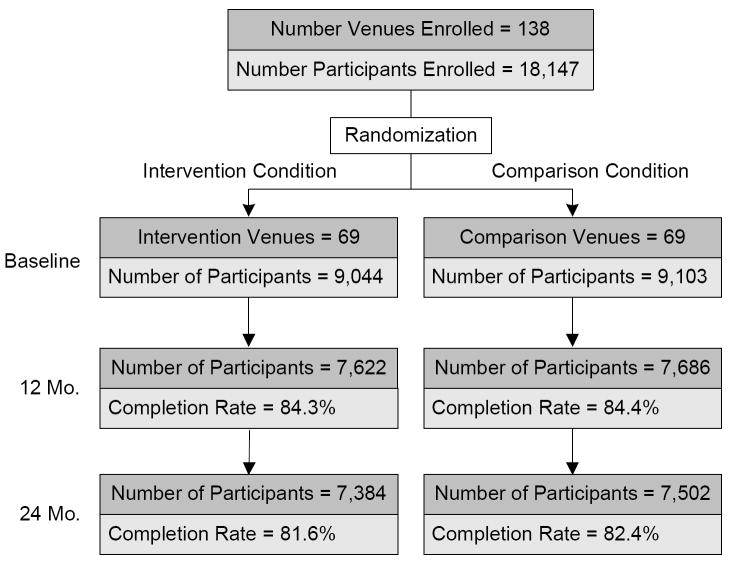

A total of 18,147 participants from 138 venues across China, India, Peru, Russia, and Zimbabwe were enrolled, with pairs of venues within a country matched and randomized to I or C conditions (Figure 1). The majority of participants were enrolled between 2002 and 2004. After initial randomization, 10 venues in China and 4 venues in India were replaced due to closing of food markets in China and the 2004 tsunami that destroyed 4 venues in India. These new venues were also matched and randomized to I or C conditions. Included among enrolled participants were 1,127 of the trained C-POLs in the intervention venues who completed study assessments.

Figure 1.

Eligible Participant Flow

Participant cohorts ranging in size from 2,212 to 5,543 participants at baseline were recruited from 20 to 40 venues in each of the five countries. The percentage of eligible individuals selected for assessment who participated were 89.4% in China, 97.6% in India, 94.9% in Peru, 93.7% in Russia, and 71.6% in Zimbabwe. The overall response rate for the interview at the 12-month follow-up was 84.4% (range 79% to 95% across countries) with 15,309 participants interviewed, and, at 24-months the response rate was 82.0% (range 80% to 92% across countries) with 14,888 participants interviewed. Among the 18,147 participants enrolled, 74% had HIV/STD testing at all three assessment points. This figure is lower than the overall participation rate because some individuals agreed to be interviewed but declined repeated biospecimen collection.

Participant characteristics at baseline

Characteristics of participants in the I and C venues (excluding C-POLs who participated in assessments) were similar at baseline with respect to demographic characteristics, the percent of people reporting unprotected sex with non-spousal/non live-in partners in the last 3 months, and the prevalence of any positive test for the six STDs being studied (Table 1). The baseline prevalence of any positive test among the six STDs ranged from approximately 8% in Russia to 38% in Zimbabwe. The percent of participants reporting unprotected sex with a non-spousal/non live-in partner in the 3 months prior to baseline ranged from 7% in China to 56% in Peru. Baseline prevalences of each of the 6 STDs separately for each country are available on request.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics for Individuals in Intervention versus Comparison Venues by Country1

| Characteristic, value (s.e.)2 | Country |

Total NI =7917 NC =9103 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China NI =1447 NC =1933 |

India NI =1651 NC =1766 |

Peru NI =1176 NC =1561 |

Russia NI =1036 NC =1071 |

Zimbabwe NI =2607 NC =2772 |

|||

| % Male | Intervention | 44.8 (2.1) | 83.6 (0.4) | 88.3 (2.8) | 52.3 (6.1) | 51.6 (1.3) | 64.2 (1.4) |

| Comparison | 45.0 (1.4) | 82.8 (0.5) | 91.5 (2.3) | 49.8 (3.9) | 53.8 (1.7) | 64.5 (1.0) | |

| Mean Age | Intervention | 36 (0.46) | 29 (0.31) | 24 (0.48) | 20 (0.20) | 22 (0.15) | 26 (0.15) |

| Comparison | 35 (0.40) | 31 (0.53) | 24 (0.44) | 20 (0.34) | 22 (0.18) | 26 (0.18) | |

| % with 7-12 Years of Education | Intervention | 52.0 (1.8) | 50.3 (2.1) | 84.4 (2.8) | 41.8 (3.2) | 90.7 (0.6) | 63.9 (1.0) |

| Comparison | 49.7 (1.4) | 46.8 (3.0) | 87.5 (1.9) | 45.6 (6.1) | 91.6 (0.5) | 64.2 (1.4) | |

| % Married or Living with Partner | Intervention | 91.7 (1.4) | 54.6 (2.0) | 28.7 (3.5) | 5.6 (1.1) | 23.6 (1.8) | 40.8 (1.0) |

| Comparison | 92.1 (0.9) | 63.4 (3.1) | 26.3 (3.4) | 7.3 (1.5) | 27.4 (2.1) | 43.3 (1.1) | |

| % Reporting Unprotected Sex last 3 months w/ non-spousal partner | Intervention | 7.3 (0.8) | 44.8 (3.9) | 55.2 (3.0) | 36.0 (2.2) | 22.2 (2.2) | 33.1 (1.2) |

| Comparison | 6.6 (0.6) | 43.5 (3.8) | 56.9 (3.8) | 36.2 (1.7) | 21.9 (1.7) | 33.0 (1.2) | |

| % with Any Positive STD | Intervention | 20.0 (1.3) | 19.8 (1.4) | 32.8 (2.9) | 7.9 (1.1) | 36.6 (1.4) | 23.4 (0.8) |

| Comparison | 20.5 (1.5) | 23.9 (1.4) | 32.0 (2.6) | 8.6 (1.2) | 39.0 (2.4) | 24.8 (0.9) | |

Overall, 17020 non-C-POL participants were included. C-POLs were excluded. NI = number of participants in the Intervention condition; NC = number of participants in the Comparison condition.

Percent/mean (standard error) shown. Percents and mean age were estimated as the average of the percents/mean across venues in each study condition within country. Information was missing for marital status: 1 participant, education: 4, unprotected sex with a non-spousal partner: 23, and prevalence of any STD: 47.

Changes in primary endpoints

Table 2 displays results for the behavioral outcome, the change between baseline and 24-months in the percent of participants reporting unprotected sex with non-spousal/non live-in partners, by country and overall. A negative value on the average difference (I-C) indicates a more favorable change in the intervention group than in the comparison group. The proportion of participants reporting unprotected sex with non-spousal/non live-in partners was reduced more between baseline and 24-months on average in the intervention venues than in the comparison venues in China, Russia, and Zimbabwe while in India and Peru the reduction was greater in the comparison venues. No statistically significant differences were found between I and C venues on the behavioral outcome in China, Peru, Russia or Zimbabwe. In India, the difference between I and C venues was marginally significant (mean = +2.85, p = 0.053); however, this positive difference represents a less favorable change in the intervention venues. Across countries, the difference between I and C venues was not significant (mean = -0.36, p = 0.71).

Table 2.

Summary of the Behavioral Outcome Data – Change from Baseline to 24 Months in Proportion of People Reporting Unprotected Sex

| Country | No. Venue Pairs | Intervention (I) |

Comparison (C) |

Difference in Change I-C 3 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. Participants 1 | People Reporting Unprotected Sex (%) 2 |

No. Participants 1 | People Reporting Unprotected Sex (%) 2 |

||||||||

| Baseline | 24 Months | Change | Baseline | 24 Months | Change | Point Estimate [95% CI] | p-value | ||||

| China | 20 | 1130 | 6.59 | 4.59 | -1.99 | 1587 | 5.01 | 4.32 | -0.68 | -1.31 [-2.96-0.34] | 0.11 |

| India | 12 | 1340 | 43.46 | 19.15 | -24.32 | 1474 | 43.16 | 16.00 | -27.16 | 2.85 [-0.03-5.85] | 0.05 |

| Peru | 10 | 922 | 54.37 | 43.95 | -10.42 | 1279 | 56.79 | 45.53 | -11.26 | 0.85 [-5.40-6.69] | 0.74 |

| Russia4 | 10 | 690 | 35.61 | 28.02 | -7.60 | 730 | 36.06 | 32.11 | -3.95 | -3.65 [-10.40-2.93] | 0.23 |

| Zimbabwe | 15 | 2056 | 21.29 | 11.86 | -9.43 | 2218 | 21.30 | 12.38 | -8.92 | -0.51 [-5.09-3.48] | 0.86 |

| Overall | 67 | 6138 | 32.27 | 21.51 | -10.75 | 7288 | 32.46 | 22.07 | -10.39 | -0.36 | 0.71 |

Analysis is based on 13426 participants, excluding CPOLs, with non-missing baseline and 24 month information.

Within country and condition, the statistics reported for Baseline, 24 Months and Change are averages over venues with equal weighting for each venue. Across country within condition, the statistics reported are averages over the 5 country averages with equal weighting for each country.

Within country, the point estimate is the average of the difference in venue pair change with equal weighting for each pair. Across country, the point estimate is the average over the 5 country averages with equal weighting for each country. The 95% confidence intervals and the p-values are based on permutation tests.

Two venue pairs are excluded in Russia due to limited sample sizes at 24 months.

Table 3 presents results based on the biological outcome, incidence of any of the 6 STDs during the study, by country and overall, unadjusted for baseline differences. A negative value on the average difference (I-C) across venues indicates a result in favor of the intervention (lower incidence of the combined STD biological endpoint). In general, the differences favored the intervention condition (not significant) for China, India, Russia, and Zimbabwe. In Peru, the incidence rate was lower overall in the comparison venues. No statistically significant differences were found between the I and C venues on the percent of participants with any new STD over the 24 months in any country or across countries (mean = -0.71, p = 0.29).

Table 3.

Summary of the Composite Biologic Outcome Data—Proportion of People Diagnosed with Any of 5 (for men) or 6 (for women) STDs Including HIV Between Baseline and 24 Months

| Country | No. Venue Pairs | Intervention (I) |

Comparison (C) |

Difference in Incidence I-C 3 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. Participants 1 | Incidence2 | No. Participants 1 | Incidence2 | Point Estimate [95% CI] | p-value | ||

| China | 20 | 1241 | 10.62 | 1669 | 10.99 | -0.37 [-2.96-2.22] | 0.77 |

| India | 12 | 1445 | 7.07 | 1577 | 8.38 | -1.31 [-4.48-1.38] | 0.42 |

| Peru | 10 | 1038 | 14.07 | 1443 | 12.26 | +1.80 [-1.47-4.95] | 0.24 |

| Russia4 | 11 | 805 | 9.07 | 867 | 11.15 | -2.08 [-5.90-1.25] | 0.26 |

| Zimbabwe | 15 | 2261 | 19.63 | 2415 | 21.22 | -1.59 [-4.86-1.66] | 0.31 |

| Overall | 68 | 6790 | 12.09 | 7971 | 12.80 | -0.71 | 0.29 |

Analysis is based on 14761 participants, excluding CPOLs, with non-missing baseline and follow-up information. No adjustment is made for baseline variables.

Within country and condition, the statistic reported is average incidence of any of the six STDs over venues with equal weighting for each venue. Across country within condition, the statistic reported is the average over the 5 country averages with equal weighting for each country.

Within country, the point estimate is the average of the differences in incidences across venue pairs with equal weighting for each pair. Across country, the point estimate is the average over the 5 country averages with equal weighting for each country. The 95% confidence intervals and the p-values are based on permutation tests.

One venue pair is excluded in Russia due to limited biologic follow-up.

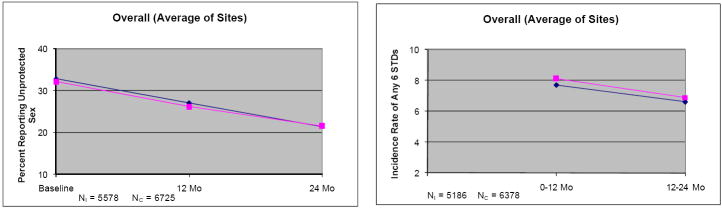

Generally, in every country, the percent of participants reporting unprotected sex with non-spousal/non live-in partners at each study visit decreased over time, and the incidence of any of the 6 STDs decreased between the first follow-up period (0-12 months) and the second follow-up period (12-24 months) in both I and C conditions (Figure 2; note the vertical scales vary by country). The absolute decrease in percent of people reporting unprotected acts between baseline and 24 months was similar in each treatment condition (I vs. C participants with all three measures, China: 2% vs. 0.6%; India: 24.7% vs. 27.7%; Peru: 10.7% vs. 11.3%; Russia: 9.1% vs. 4%; Zimbabwe: 10.7% vs. 9.5%; Overall: 11.5% vs. 10.6%). These decreases were fairly substantial relative to the baseline percents (33% over countries; 11-64% depending on country and treatment condition), but they occurred in both study conditions. In general, incidence rates showed modest declines between the first and second follow-up periods in both groups or remained flat (absolute change I and C, China: -1.0%, -1.1%; India: -2.1%, -3.9%; Peru: -2.3%, +0.2%; Russia: +0.1%, -0.5%; Zimbabwe: -0.2%, -0.7%; Overall: -1.1%, -1.2%).

Figure 2.

Behavioral and biologic outcomes over time among the subset of participants with all measurements: percent of people reporting unprotected sex with non-spousal/non live-in partners during the 3 months prior to baseline, 12 and 24 month visits, and incidence of any of the six STDs between baseline and 12 months and between 12 and 24 months. NI = number of Intervention participants; NC = number of Comparison participants. ◆ = Intervention group; ■ = Comparison group. Ranges of standard errors over time and study condition for the percent of people reporting unprotected sex were: China, 0.47-0.86; India, 1.3-3.9; Peru, 2.6-3.6; Russia, 1.8-4.3; Zimbabwe, 1.4-1.9; overall, 1.0-1.3. Ranges of standard errors for incidence of any STD were: China, 0.7-1.0; India, 0.6-1.5; Peru, 0.8-1.3; Russia, 1.1-1.5; Zimbabwe, 0.9-1.4; Overall, 0.4-0.5. Note: At baseline, incidence of any of the six STDs was not available; baseline prevalences were available but are not shown.

Secondary analyses

The analyses in Tables 2 and 3 were repeated with adjustment made for baseline characteristics. After adjusting for baseline variables, results for both endpoints were similar to unadjusted results within and across countries (behavioral outcome adjusted mean across countries = -0.57, p = 0.53; composite biological outcome adjusted mean across countries = -0.64, p = 0.33; variables used for adjustments available on request). Next, the primary unadjusted analyses were repeated with data from the C-POLs included. No statistically significant differences were found on either outcome when C-POLs were included.

Changes in additional endpoints were examined using permutation tests as for the primary outcomes. The change in the number of episodes of unprotected sex with a non-spousal partner reported at baseline and the 24 month assessment was not significantly different between I and C venues in any country. Differences were estimated between I and C venues based on incidence in the 12 to 24 month period to determine whether the intervention had a larger effect after the first year. Again, significant differences were not found between I and C venues by country or overall.

Where incidence rates allowed, individual STDs were examined separately. Specifically, we examined differences between I and C groups on incidence of HSV-2 (in all countries), HIV (in Zimbabwe), Chlamydia (in China, Peru, Russia, and Zimbabwe), and trichomonas (in women in China, India, and Zimbabwe). Comparisons could not be made for gonorrhea or syphilis due to small incidence rates in all countries. No statistically significant differences were found between I and C venues on incidence of HIV in Zimbabwe, on incidence of Chlamydia in any of the 4 countries examined or overall in those countries, or on incidence of trichomonas in women in any of the 3 countries studied or across the 3 countries. Statistically significant differences were found between I and C groups on incidence of HSV-2 in China (average difference on incidence across venues: -1.26, p=0.012) and Russia (average difference: -1.50, p=0.016), but not in India, Peru, or Zimbabwe. Except in Zimbabwe, there were fewer than 100 incident cases of HSV-2 per country. Therefore, this result should be interpreted with caution due to potential volatility caused by the low incidence rates. Model-based analysis using longitudinal models provided results similar to those found for the permutation test analyses.

The proportion of cohort participants who reported having conversations in the three months before the baseline and 24-month follow-ups was examined by experimental condition separately for AIDS/STDs and condoms. Over countries at 24-monthe, the proportion in the intervention group reporting conversations about AIDS/STDs was 63.1%, with 56.7% reporting conversations about condoms. These proportions were higher than in the control group at 24-months (51.0% and 45.8%, respectively) and the intervention group at baseline (50.1% and 46.1%, respectively).

Discussion

Contrary to expectations, the C-POL intervention and its comparison condition produced similar, significant, and clinically relevant reductions in both STD incidence and self-reported unprotected extramarital sexual acts. These significant reductions represent approximately a 30% reduction in self-reported unprotected acts and a 20% reduction in incidence of STDs. It is important to recall that the comparison condition was a community-wide AIDS educational intervention with three repeated individual assessments of about two hours each that included repeated HIV and STD counseling and testing, extensive manual-based risk reduction counseling, and an interview during which participants reflected on their HIV/STD-related risky behaviors. Access to condoms and efficacious treatment were guaranteed in both conditions. For example, in China, in which almost all STD treatments are typically provided by pharmacists giving Chinese herbs, educational workshops regarding antibiotics were conducted for pharmacists in both conditions. The RCT was designed to examine the added community-level benefit of the shift in community norms addressed by the C-POL intervention. Under these conditions, the overall impact on outcomes in the intervention and comparison conditions was not significantly different. Several factors may account for the strong overall risk behavior reductions over time and the absence of differential outcomes between the two experimental conditions.

First, historically, HIV prevention research has compared the effect of an experimental intervention against the “standard of care” or an attention control condition. In this study, the effects of the C-POL intervention were compared to a condition that directly focuses a person’s attention on the risks of recent sexual practices which often reduces subsequent risk behaviors, such as occurs with motivational interviewing.18,19 In fact, almost every large HIV prevention RCT, whether examining biomedical or behavioral interventions, has demonstrated a significant reduction in sexual risk when coupled with repeated HIV/STD testing, counseling, condom access, and STD treatment.20-22 Behavioral reactivity may have been especially strong in this trial, because the participants in the comparison group received a substantial and sustained AIDS education intervention.23

Although HIV testing and treatment for STDs are available to population members who seek out these services in the sites where this trial took place, intensive prevention and treatment care of the kind provided to study participants in both conditions greatly exceeded usual local standards and is not currently sustainable. In fact, since the Trial was completed, the major components of the AIDS education comparison condition have disappeared. At the recent ISSTDR meeting, the point was made that it may not be ethical to offer a comparison condition which is not sustainable when the treatment condition may be.24 While there are no cost effectiveness or implementation data on the C-POL intervention in these sites, Pinkerton and colleagues25 conducted a cost-utility analysis of the intervention with gay men in the U.S., which indicated that in addition to being highly efficacious, it is highly cost effective. The overall cost of the intervention (about $40 per affected individual in the U.S.) is likely to fall within the budgetary constraints of many community-based AIDS prevention organizations in developing countries. Because the intervention is delivered by community members (not professional counselors) who can be inexpensively trained, it is more likely to be feasible for a resource-poor community to sustain the C-POL intervention than the intensive AIDS education comparison condition.26

Second, the long duration of the Trial, including its lengthy follow-up period, increased the likelihood that other public health AIDS prevention service programs and research were being carried out in the same communities and concurrently affecting the study’s populations. The significant increases in media attention, public health awareness, and diffusion of prevention messages in each country during this trial were likely to have reached populations in all study venues. For example, in India, the Gates-supported Avahan outreach to female sex workers reached virtually all of the women in the Chennai cohort.

Third, there has been emerging recognition that STDs, especially Chlamydia and trichomoniasis, spontaneously remit over the period of 3-6 months. These data have only emerged in the last five years. There are individual differences in the rate of spontaneous remission: for example, older persons and those with a greater number of lifetime partners are more likely to clear infections without treatment.27 This information was not known at the beginning of this trial. If the intervention was efficacious and individuals in that condition did not contract HIV/STDs, and the individuals in the comparison condition contracted Chlamydia and trichomoniasis, but it spontaneously cleared prior to the assessment, then, the effect size that we observed would be smaller than it really was.

Fourth, while community-level preventive interventions have been repeatedly called for by public health officials, changes in rates of STD and behavioral risk can only be empirically demonstrated among those with initial risk at the baseline assessment. The constraints of a longitudinal RCT require many more conditions be met, rather than only the presence of risk. The population must be stable over time (e.g., not characteristic of migrants in many countries); the local providers must have capacity to implement an RCT; the site must be close to a certified laboratory; the officials must be cooperative. Also, successful mobilization of a community is different when the majority of community participants demonstrate risk as indicated in multiple ways here. In China for example, those with previous STDs, those persons at highest risk of future infections, demonstrated greater reductions over two years than those in the comparison condition. Additionally, incident viral HSV infections were significantly lower in the intervention condition in China and Russia compared to the comparison conditions. These data suggest benefits of the C-POL intervention for those within the communities that were most likely to transmit STDs.

Different outcomes might have been found if the community-level intervention had been compared to usual and standard community services which are invariably less than the comparison condition participants received. Our findings illustrate issues that will be confronted in future HIV prevention research that compares the effects of newly-developed interventions against comparison interventions already known to be efficacious. This stance sets an ethical bar higher than often employed in the past. In some cases, new models may produce stronger effects than the best presently-available approaches. In other cases—such as in the present and other trials20—they may not. Regardless, the HIV prevention field has advanced to the point of requiring that comparison conditions use interventions of known, established efficacy against which new approaches can be compared. The current trial reinforces the challenges of requiring this heightened standard for an ethical, but possibly not sustainable comparison condition.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge all of those who participated in and staffed the NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial.

Sources of support: This study was supported by National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health (NIH), through the Cooperative Agreement mechanism (U10MH061499, U10MH061513, U10MH061536, U10MH061537, U10MH061543, U10MH061544).

Appendix

Research Steering Committee/Site Principal Investigators and NIMH Senior Scientist

Carlos F. Caceres, M.D., Ph.D. (Cayetano Heredia University [UPCH], Lima, Peru); David D. Celentano, Sc.D. (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland); Thomas J. Coates, Ph.D. (David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles [UCLA]); Tyler D. Hartwell, Ph.D. (RTI International [RTI], Durham, NC); Danuta Kasprzyk, Ph.D. (Battelle Memorial Institute [Battelle], Seattle, WA); Jeffrey A. Kelly, Ph.D. (Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI); Andrei P. Kozlov, Ph.D. (Biomedical Center, St. Petersburg State University, St. Petersburg, Russia); Willo Pequegnat, Ph.D. (National Institute of Mental Health, Rockville, MD); Mary Jane Rotheram-Borus, Ph.D. (UCLA); Suniti Solomon, M.D. (YRG Centre for AIDS Research and Education [YRG CARE], Chennai, India); Godfrey Woelk, Ph.D. (University of Zimbabwe Medical School, Harare, Zimbabwe); Zunyou Wu, Ph.D. (Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing, China)

Collaborating Scientists/Co-Investigators

Roman Dyatlov, Ph.D. (St. Petersburg State University; The Biomedical Center, St. Petersburg, Russia); A.K. Ganesh, A.C.A., B.Com. (YRG CARE); Li Li, Ph.D. (UCLA); Sudha Sivaram, Ph.D., M.P.H. (Johns Hopkins University); Anton M. Somlai, Ed.D. (Medical College of Wisconsin)

Assessment Workgroup

Eric G. Benotsch, Ph.D. (Medical College of Wisconsin); Juliana Granskaya, Ph.D. (St. Petersburg State University; The Biomedical Center); Jihui Guan, M.D. (Fujian Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Fuzhou, China); Martha Lee, Ph.D. (UCLA); Daniel E. MontaZo, Ph.D. (Battelle)

Biologic Outcomes Workgroup

Nadia Abdala, Ph.D. (Yale University, New Haven, CT); Roger Detels, M.D., M.S. (UCLA); David Katzenstein, M.D. (Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA); Jeffrey Klausner, M.D., M.P.H. (San Francisco Department of Public Health, University of California at San Francisco [UCSF], San Francisco, CA); Kenneth H. Mayer, M.D. (Brown University/Miriam Hospital, Providence, RI); Michael Merson, M.D. (Yale University)

Ethnography Workgroup

Margaret E. Bentley, Ph.D. (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC); Olga I. Borodkina, Ph.D. (St. Petersburg State University; The Biomedical Center); Maria Rosa Garate, M.Sc. (UPCH); Vivian F. Go, Ph.D. (Johns Hopkins University); Barbara Reed Hartmann, Ph.D. (Medical College of Wisconsin); Sethulakshmi Johnson, M.S.W. (YRG CARE); Eli Lieber, Ph.D. (UCLA); Andre Maiorana, M.A., M.P.H. (UCSF); Ximena Salazar, M.Sc. (UPCH); David W. Seal, Ph.D. (Medical College of Wisconsin); Nikolai Sokolov, Ph.D. (St. Petersburg State University; The Biomedical Center); Cynthia Woodsong, Ph.D. (RTI)

Intervention Workgroup

Walter Chikanya, B.S. (University of Zimbabwe, Harare, Zimbabwe); Nancy H. Corby, Ph.D. (UCLA); Cheryl Gore-Felton, Ph.D. (Medical College of Wisconsin); Susan M. Kegeles, Ph.D. (UCSF); Suresh Kumar, M.D. (SAHAI Trust, Chennai, India); Carl Latkin, Ph.D. (Johns Hopkins University); Letitia Reason, Ph.D., M.P.H. (Battelle); Ana Maria Rosasco, B.A. (UPCH); Alla Shaboltas, Ph.D. (St. Petersburg State University; The Biomedical Center); Janet St. Lawrence, Ph.D. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA)

Workgroup on Protecting Human Participants and Ethical Responsibility

Alejandro Llanos-Cuentas, M.D., Ph.D., (UPCH); Stephen F. Morin, Ph.D. (UCSF)

Laboratory Managers

Pachamuthu Balakrishnan, Ph.D., M.Sc. (YRG CARE); Segundo Leon, M.Sc. (UPCH); Patrick Mateta, Spec.Dip.MLSc., M.B.A. (University of Zimbabwe); Stephanie Sun, M.P.H. (UCLA); Sergei Verevochkin, Ph.D. (The Biomedical Center); Yueping Yin, Ph.D. (National Center for STD and Leprosy Control, Nanjing, China)

Site Coordinators/Managers

Sherla Greenland, B.S. (University of Zimbabwe); Olga Kozlova, (The Biomedical Center); Reggie Mutsindiri, B.S., R.N. (University of Zimbabwe); Jose Pajuelo, M.D., MPH, (UPCH); Keming Rou (Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention); A.K. Srikrishnan, B.A. (YRG CARE); Sheng Wu, M.P.P. (UCLA)

Site Data Managers

S. Anand (YRG CARE); Julio Cuadros Bejar (Lima, Peru); Patricia T. Gundidza, B.S. (University of Zimbabwe); Andrei Kozlov, Jr. (St. Petersburg, Russia); Wei Luo (Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention)

Data Coordinating Center (RTI unless otherwise noted)

Gordon Cressman, M.S.; Martha DeCain, B.S.; Laxminarayana Ganapathi, Ph.D.; Annette M. Green, M.P.H.; Sylvan B. Green, M.D. (Deceased, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ); Nellie I. Hansen, M.P.H.; Sheping Li, Ph.D.; Cindy O. McClintock, B.A.; Deborah W. McFadden, M.B.A.; David L. Myers, Ph.D.; Corette B. Parker, Dr.P.H.; Pauline M. Robinson, M.S.; Donald G. Smith, M.A.; Lisa C. Strader, M.P.H.; Vanessa R. Thorsten, M.P.H.; Pablo Torres, B.S.; Carol L. Woodell, B.S.P.H.

Reference Laboratory (Johns Hopkins University)

Charlotte A. Gaydos, Dr.P.H.; Tom Quinn, M.D.; Patricia A. Rizzo-Price, M.T., M.S.

Cross-site Quality Control and Quality Assurance

L. Yvonne Stevenson, M.S. (Medical College of Wisconsin)

Footnotes

Partial Data Presented: Poster at XVII International AIDS Conference, Mexico City, August 3-8, 2008

References

- 1.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) AIDS epidemic update—December 2007. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 4. New York: Free Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly JA, Murphy DA, Sikkema KJ, et al. Community HIV Prevention Research Collaborative. Randomized, controlled, community-level HIV prevention intervention for sexual risk behaviour among homosexual men in U.S. cities. Lancet. 1997;350:1500–1505. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)07439-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones KT, Gray P, Whiteside YO, et al. Evaluation of an HIV prevention intervention adapted for Black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(6):1043–1050. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.120337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sikkema KJ, Kelly JA, Winett RA, et al. Outcomes of a randomized community-level HIV prevention intervention for women living in 18 low-income housing developments. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:57–63. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial Group. Methodological overview of a five-country community-level HIV/STD prevention trial. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 2):S3–S18. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000266453.18644.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial Group. Selection of populations represented in the NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 2):S19–S28. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000266454.26268.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial Group. Design and integration of ethnography within an international behavior change HIV/sexually transmitted disease prevention trial. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 2):S37–S48. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000266456.03397.d3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial Group. Formative study conducted in five-countries to adapt the community popular opinion leader intervention. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 2):S91–S98. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000266461.33891.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial Group. The feasibility of audio computer-assisted self-interviewing in international settings. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 2):S49–S58. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000266457.11020.f0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial Group. Sexually transmitted disease and HIV prevalence and risk factors in concentrated and generalized HIV epidemic setting. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 2):S81–S90. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000266460.56762.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial Group. Challenges and process of selecting outcome measures for the NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 2):S29–S36. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000266455.03397.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial Group. The community popular opinion leader HIV prevention programme: conceptual basis and intervention procedures. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 2):S59–S68. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000266458.49138.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial Group. Ethical issues in the NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 2):S69–S80. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000266459.49138.b3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial Group. Role of the data safety and monitoring board in an international trial. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 2):S99–S102. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000266462.33891.0b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray DM, Hannan PJ. Planning for the appropriate analysis in school-based drug-use prevention studies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1990;58:458–468. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.4.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gail MH, Carroll RJ, Green SB, et al. On Design Considerations and Randomization-Based Inference for Community Intervention Trials. Statistics in Medicine. 1996;15:1069–1092. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960615)15:11<1069::AID-SIM220>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller WR. Motivational interviewing with problem drinkers. Behavioural Psychotherapy. 1983;11:147–172. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing, Second Edition: Preparing people for change. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamb ML, Fishbein M, Douglas JM, et al. Efficacy of risk-reduction counseling to prevent human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted diseases: A randomized controlled trial. Project RESPECT Study Group. JAMA. 1998;280(13):1161–1167. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.13.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The National Insitute of Mental Health (NIMH) Multisite HIV Prevention Trial Group. The NIMH Multisite HIV Prevneiton Trial: reducing HIV sexual risk behavior. Science. 1998;280:1889–1894. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kobin B, Chesney M, Coates T EXPLORE Study Team. Effects of a behavioural intervention to reduce acquisition of HIV infection among men who have sex with men: the EXPLORE randomized controlled study. Lancet. 2004;364:41–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16588-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalichman SC, Kelly JA, Stevenson LY. Priming effects of HIV risk assessments on related perceptions and behavior: An experimental field study. AIDS and Behavior. 1997;1:3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wasserheit J. STI/HIV prevention research: the agony, the ecstasy and the future. Presented at: 18th ISSTDR; 2009; London. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pinkerton SD, Holtgrave DR, DiFranceisco WJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a community-level HIV risk reduction intervention. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1239–1242. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.8.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelly JA, Somlai AM, Benotsch EG, et al. Distance communication transfer of HIV prevention interventions to service providers. Science. 2004;305:1953–1955. doi: 10.1126/science.1100733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sheffield JS, Andrews WW, Klebanoff MA, et al. National Institute for Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Spontaneous resolution of asymptomatic Chlamydia trachomatis in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:557–562. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000153533.13658.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gregson S, Adamson S, Papaya S, et al. Impact and process evaluation of integrated community and clinic-based HIV-1 control: A cluster-randomised trial in eastern Zimbabwe. PLoS Med. 2007;4(3):e102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]