Abstract

Varicosities immunoreactive for nitric oxide synthase (NOS) make synaptic connections with submucosal neurons in the guinea-pig small intestine, but the effects of nitric oxide (NO) on these neurons are unknown. We used intracellular recording to characterize effects of sodium nitroprusside (SNP, NO donor) and nitro-l-arginine (NOLA, NOS inhibitor), on inhibitory synaptic potentials (IPSPs), slow excitatory synaptic potentials (EPSPs) and action potential firing in submucosal neurons of guinea-pig ileum in vitro. Recordings were made from neurons with the characteristic IPSPs of non-cholinergic secretomotor neurons. SNP (100 μM) markedly enhanced IPSPs evoked by single stimuli applied to intermodal strands and IPSPs evoked by trains of 2–10 pulses (30 Hz). Both noradrenergic (idazoxan-sensitive) and non-adrenergic (idazoxan-insensitive) IPSPs were affected. SNP enhanced hyperpolarizations evoked by locally applied noradrenaline or somatostatin. SNP did not affect slow EPSPs evoked by single stimuli, but depressed slow EPSPs evoked by stimulus trains. NOLA (100 μM) depressed IPSPs evoked by one to three stimulus pulses and enhanced slow EPSPs evoked by trains of two to three stimuli (30 Hz). SNP also increased the number of action potentials and the duration of firing evoked by prolonged (500 or 1000 ms) depolarizing current pulses, but NOLA had no consistent effect on action potential firing. We conclude that neurally released NO acts post-synaptically to enhance IPSPs and depress slow EPSPs, but may enhance the intrinsic excitability of these neurons. Thus, NOS neurons may locally regulate several secretomotor pathways ending on common neurons.

Keywords: nitric oxide, secretomotor neurons, IPSPs, slow EPSPs, somatostatin, noradrenaline, neuronal excitability

Introduction

Neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) is widely distributed in the central and peripheral nervous systems. Its product nitric oxide (NO) is a well established mediator of vasodilatation and gastrointestinal relaxation. Despite intense interest in actions of NO at central synapses (see Garthwaite, 2008), there have been very few studies of its role at enteric synapses.

In the gastrointestinal tract, nNOS is expressed by descending interneurons and inhibitory motor neurons supplying the intestinal smooth muscle. NO is well recognized as a inhibitory transmitter to the intestinal muscle (Lecci et al., 2002), but may also contribute to generation of complex motor patterns mediated by the enteric neural circuitry (Lyster et al., 1995; Spencer et al., 1998; Roberts et al., 2007, 2008). However, determining sites of action of the NO is complicated by the presence of nNOS in both myenteric nerve terminals and myenteric cell bodies (Costa et al., 1996) and evidence that NO can act as a retrograde messenger from post-synaptic neurons to their synaptic inputs (Yuan et al., 1995). This observation was consistent with a report by Tamura et al. (1993) that the NO donor sodium nitroprusside (SNP) depresses slow EPSPs in some myenteric neurons. However, it contrasts with a later report from Dickson et al. (2007) suggesting that NO is the transmitter mediating inhibitory synaptic potentials (IPSPs) in some myenteric neurons in the guinea-pig colon. There is also significant evidence that neurally released NO regulates secretion of water and electrolyte across the intestinal mucosa by acting on the secretomotor neurons of the submucosal plexus (Mourad et al., 2003). In the guinea-pig, nNOS neurons are widespread in the myenteric plexus, but there are few, if any, nNOS neurons in the submucosal plexus (Furness et al., 1994). Thus, the submucosal plexus is ideal for analysis of the role of NO released from synaptic terminals as there is a clear innervation by nNOS-immunoreactive nerve terminals arising from myenteric interneurons (Li et al., 1995).

There are no previous studies of the effects of NO on either synaptic transmission or the excitability of submucosal neurons. However, the NO donor, SNP, produces a marked increase in cyclic GMP levels within the 45% of submucosal neurons immunoreactive for vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) (Young et al., 1993). These neurons are non-cholinergic secretomotor neurons (Bornstein and Furness, 1988) and receive a large variety of converging synaptic inputs (Gwynne and Bornstein, 2007). They exhibit fast excitatory synaptic potentials (EPSPs) lasting up to 50 ms; at least two pharmacologically distinct classes of inhibitory synaptic potentials and three classes of slower EPSPs. We examined the effects of NO on the IPSPs and slow EPSPs in the VIP neurons, to determine whether NO modifies their excitability and whether inhibition of NOS reveals similar effects of endogenous NO.

Materials and Methods

Tissue preparation

Guinea-pigs (160–310 g) were stunned by a blow to the back of the head and killed by severing the spinal cord and carotid arteries. The experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) guidelines, and approved by the University of Melbourne Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee. Preparations of submucous plexus were dissected from the small intestine using methods previously described (Hirst and McKirdy, 1975; Bornstein et al., 1986) and pinned mucosal surface down in a recording chamber continuously superfused with physiological saline (composition in mM): NaCl 118, KCl 4.8, NaHCO3 25, NaH2PO4 1.0, MgSO4 1.2, CaCl2 2.5, D-glucose 11, bubbled with 95% O2, 5% CO2 at 34–36°C (4–6 mL/min).

Electrophysiology

Conventional intracellular recording methods were used as previously described to record from submucosal neurons (Bornstein et al., 1986; Monro et al., 2004). Microelectrodes usually contained 1 M KCl (tip resistance 100–200 MΩ), but in a small number of experiments 1% biocytin was added to the electrode solution to allow impaled neurons to be reidentified histologically after fixation. Impalement durations ranged from 0.5 to 3.5 h with neuronal characterization starting at least 5–10 min after impalement.

Synaptic potentials were evoked by electrical stimulation of interganglionic fiber tracts with a monopolar tungsten stimulating electrode (tip diameter 50–80 μm). Stimuli were delivered as either single pulses or trains of 2, 3, 5, 10 or 15 pulses at 30 Hz. These parameters have been previously shown to evoke the full range of different synaptic potentials that can be seen in submucosal neurons including fast EPSPs (single pulses), intermediate EPSPs (single pulses), IPSPs (1–15 pulses), slow EPSPs mediated by P2Y1 receptors (single pulses) and non-purinergic slow EPSPs (3–15 pulses). Stimulus parameters were typically 1.5 mA (range 0.3–2 mA) and 0.5 ms duration (Master-8 stimulator, ISO-Flex stimulus isolation unit; both from AMPI, Jerusalem, Israel). Stimulus currents were adjusted to reliably evoke the synaptic responses (this varied between preparations); duration was restricted to 0.5 ms to prevent stimulation of residual muscle on the preparation. These settings were retained for later stimulus trains.

Action potentials were evoked by depolarizing current pulses (500 or 1000 ms duration, 5 s apart) injected via the recording electrode. The magnitude of the current pulse was increased in steps over the range 10–200 pA to identify whether the firing changed with increases in stimulus amplitude.

Input resistance was taken as the gradient of a plot of the membrane voltage change (steady-state) against the magnitude of hyperpolarizing and depolarizing current pulses (±10 to 100 pA, 500 or 1000 ms duration, 5 s apart).

Identification of neuronal subtype

Impaled neurons that exhibited an IPSP in response to a train of three pulses at 30 Hz were assumed to be VIP secretomotor neurons, because IPSPs are seen in all these neurons and are absent from other submucosal neurons (Bornstein et al., 1986; Evans et al., 1994). Neurons lacking IPSPs were not studied further. In a few cases, electrophysiological identification of neurons with IPSPs was confirmed via intracellular injection of biocytin and subsequent immunohistochemistry (for details of Methods see Monro et al., 2004). All neurons with IPSPs were found to be immunoreactive for VIP.

Pharmacology

In most cases, pharmacological agents were applied to the recording bath via the saline perfusate. Agents included sodium nitroprusside (SNP, 100 μM; Merck, Victoria, Australia), idazoxan (2 μM;) and N-nitro-l-arginine (NOLA, 100 μM) (both from Sigma-Aldrich, Sydney, Australia). These agents were made up to working concentrations in physiological saline from stock solutions kept at 4°C. Drugs were allowed to equilibrate for 5–15 min and washed out for 20–60 min before washout responses were sought.

In some experiments, noradrenaline (1 mM) and somatostatin-14 (SOM, 100 μM, both from Sigma-Aldrich, Sydney, Australia) were applied to the cell body by pressure ejection (15 p.s.i, 50–250 ms) from a micropipette (tip approximately 10 μm) positioned just above the impaled neuron (Picospritzer III, Parker Instrumentation, Hadland Photonics, Victoria, Australia) (Foong and Bornstein, 2009a).

Statistics

Recordings were measured using AxoScope 9, and statistical data were analyzed with Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, USA), Origin 7.5 (OriginLab, MA, USA) and Minitab 14 (Minitab Inc, PA, USA). Parameters measured: amplitude (slow EPSPs and IPSPs), duration (IPSPs), number of action potentials and duration of firing. Amplitudes of synaptic potentials were measured from resting membrane potential to peak, and duration was measured from the first change in membrane potential to the point at which the voltage returned to resting potential.

Replicate measurements within individual cells were averaged for comparisons between neurons. n refers to the number of neurons recorded. Numbers given are mean ± S.E.M. unless otherwise stated. Student's t test (paired, two-tailed) or two-factor ANOVA were used to compare synaptic potential data. Two-factor ANOVA was also used to assess the effect of current intensity and drug treatment on the number of action potentials and firing duration. In experiments with NOLA, a single-tailed test was used as the results could be predicted from the SNP experiments. In all cases, P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The washouts were performed to confirm that the responses were reversible and not time-dependent.

Results

A total of 179 neurons from 88 preparations responded to focal stimulation of an internodal strand (3 pulses 30 Hz) with an IPSP and were considered for further analysis. Of these, impalements in 51 were stable for long enough (45–150 min) to allow pharmacological studies and the data from these is set out below. All these neurons exhibited fast EPSPs in response to single pulses and several also exhibited intermediate EPSPs (Bornstein et al., 1986; Monro et al., 2004), although no systematic search was made for the latter. Most neurons with IPSPs also exhibited slow EPSPs in response to a single stimulus and/or trains of up to 10 stimuli (30 Hz). Membrane properties of these neurons were similar to those reported previously (e.g. input resistance ranged from 43 to 650 MΩ, with a mean of 224 MΩ, n = 40; Bornstein et al., 1986).

SNP enhances IPSPs

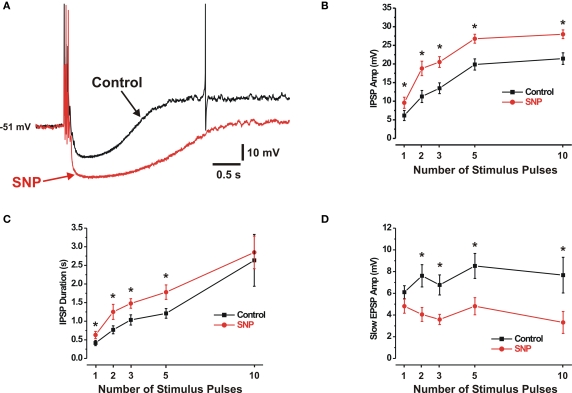

The amplitudes of IPSPs increased monotonically with the number of stimulus pulses applied, up to 10 pulses (Figure 1B), mean amplitudes of 1- and 10-pulse IPSPs were 6.1 ± 1.4 mV and 21.4 ± 1.6 mV respectively. In the same neurons, the NO donor SNP (100 μM) enhanced the amplitudes of electrically evoked IPSPs (Figure 1A); this was statistically significant for all stimulus trains. One-pulse IPSPs increased 56% (to 9.6 ± 1.5 mV, n = 24), while 10-pulse IPSPs increased 31% (to 28.0 ± 1.2 mV, n = 22).

Figure 1.

SNP enhances IPSPs but suppresses some SEPSPs. (A) IPSPs evoked by a 3-pulse stimulus in control (black) and SNP (100 μM) (red). (B,C) Quantitative data for the effects of SNP on amplitudes and durations respectively of 1-, 2-, 3-, 5- and 10-pulse evoked IPSPs (control solid black line, SNP solid red line). (D) SNP reduced the amplitudes of 2-, 3-, 5- and 10-pulse slow EPSPs, but had no effect on single stimulus evoked SEPSPs. *P < 0.05.

The duration of IPSPs similarly increased with the number of stimulus pulses applied, up to 10 pulses (Figure 1C). The mean durations of the 1- and 10-pulse IPSPs were 0.42 ± 0.07 s and 2.6 ± 0.70 s respectively. As seen in Figure 1C, SNP increased the mean durations of IPSPs evoked by shorter stimulus trains (1, 2, 3 and 5 pulses). One-pulse IPSPs increased 52% (to 0.63 ± 0.09 s; P < 0.01, n = 22) and 5-pulse IPSPs increased 47% (to 1.8 ± 0.20 s; P < 0.001, n = 25). A similar trend applied to the 10-pulse IPSPs, but the effect was not statistically significant.

These experiments required prolonged recordings and washout data were not always obtained. However, the effect of SNP generally reversed upon washout.

Sodium nitroprusside had no significant effect on membrane potential, (control 49 ± 2 mV, SNP 49 ± 3 mV, n = 14, P > 0.2) but produced a significant increase in input resistance (control 154 ± 29 MΩ, SNP 357 ± 43 MΩ; P < 0.01, n = 9).

SNP suppresses some slow EPSPs

Of the 43 neurons exposed to SNP, 36 exhibited slow EPSPs evoked by focal electrical stimulation. The amplitudes of slow EPSPs measured at their peaks after IPSPs had returned to resting membrane potential did not vary noticeably with the number of stimulus pulses applied (Figure 1D). The mean amplitudes of the 1-, 3- and 10-pulse slow EPSPs were 6.1 ± 0.6 mV, 6.8 ± 0.9 mV and 7.7 ± 1.6 mV respectively. SNP did not affect slow EPSPs evoked by single stimuli, responses known to be mediated by P2Y1 receptors (Hu et al., 2003; Foong and Bornstein, 2009b), but decreased the amplitudes of slow EPSPs evoked by trains of stimuli at 30 Hz (Figure 1D). Three-pulse and 10-pulse slow EPSPs were decreased by 47% (to 3.6 ± 0.5mV; P < 0.001, n = 28) and 57% (to 3.3 ± 1.0mV; P < 0.01, n = 15) respectively. Slow EPSPs evoked by such trains do not appear to be mediated by P2Y1 receptors (Foong and Bornstein, 2009b). Amplitudes returned to (or exceeded) control values in cells where washout of SNP was achieved.

Slow EPSP durations were highly variable, both within and between neurons. This made it difficult to assess pharmacological effects; for this reason these data are not presented.

Inhibition of endogenous NOS depresses IPSPs

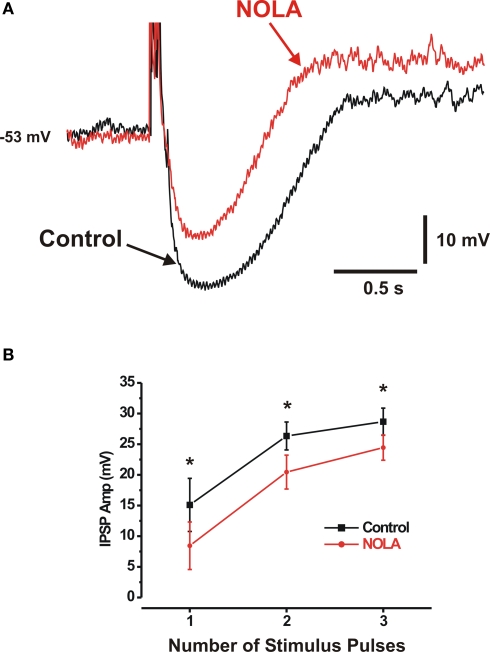

In other experiments, the effects of a NOS inhibitor NOLA (100 μM) were tested on synaptic potentials evoked by 1, 2 and 3 pulse stimuli (2, 3 pulses at 30 Hz) in neurons selected for study because they had large IPSPs, thereby increasing the likelihood of detecting small decreases. Short trains were used because longer trains at 30 Hz may cause unphysiological release of NO and hence produce misleading results. NOLA, and hence blockade of endogenous NO synthesis, depressed IPSPs evoked by each of these stimuli (Figure 2) (one pulse IPSP control 15.1 ± 4.3 mV, NOLA 8.4 ± 3.9 mV, 44%, P < 0.02; three pulse IPSP control 28.7 ± 2.2 mV, NOLA 24.5 ± 2.1 mV, 15%, P < 0.01; n = 8; single-tailed tests). This was accompanied by a reduction in the duration of IPSPs, but this was only significant for responses to single stimuli (one pulse control 0.34 ± 0.06 s, NOLA 0.22 ± 0.07 s, P < 0.02, n = 7; 2 pulse control 0.61 ± 0.11 s, NOLA 0.49 ± 0.08 s, P > 0.1, n = 8; 3 pulse control 0.77 ± 0.12 s, NOLA 0.66 ± 0.11 s, P > 0.05, n = 8; single-tailed tests), possibly because of a large variability in IPSP durations between different preparations.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of endogenous NOS depresses IPSPs. (A) Three-pulse IPSP in control (black) and in the presence of NOLA (100 μM) (red) (B) Quantitative data; NOLA significantly reduced the amplitudes of 1-, 2- and 3-pulse IPSPs. *P < 0.05 (single-tailed t test).

Inhibition of endogenous NOS enhances slow EPSPs

Nitro-l-arginine produced small, but significant, increases in the amplitudes of the slow EPSPs evoked by 2 and 3 pulse trains (30 Hz, Figure 2A) (control 9.7 ± 0.6 mV, NOLA 11.7 ± 0.8 mV (P < 0.05, n = 7, single-tailed test) and control 9.8 ± 0.4 mV, NOLA 12.6 ± 0.6 mV (P < 0.05, n = 8, single-tailed test), respectively). NOLA did not affect slow EPSPs evoked by single pulses (control 9.1 ± 0.6 mV in control, NOLA 10.3 ± 0.9 mV (P > 0.5, n = 7, two-tailed test).

SNP enhances noradrenaline evoked hyperpolarizations

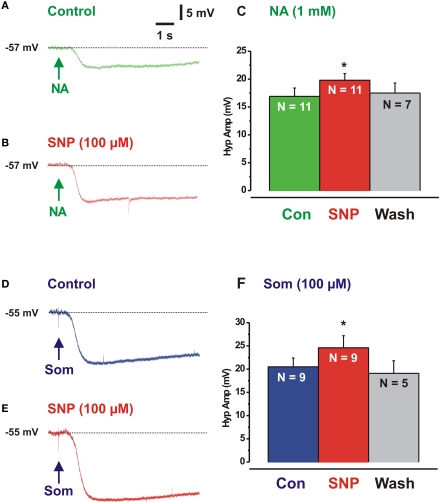

Noradrenaline-evoked hyperpolarizations (1 μM in pressure pipette) were measured in the presence of SNP to test whether the effects of the NO donor were pre- or post-synaptic. SNP markedly enhanced the hyperpolarizations evoked when noradrenaline was applied to the cell bodies of neurons with IPSPs (Figures 3A,B,C) indicating that at least part of the action of NO is post-synaptic (control NA 16.9 ± 1.5 mV, SNP 19.8 ± 1.2, P = 0.02).

Figure 3.

Sodium nitroprusside enhances responses evoked by noradrenaline and somatostatin. (A) Hyperpolarization evoked by local application of noradrenaline (NA, at arrow, green), (B) response evoked by NA in presence of SNP (red). (C) Quantitative data (n – number of neurons). (D,E) Hyperpolarizations evoked by SOM in control (blue) and SNP (red). (F) Quantitative data. *P < 0.05.

SNP enhances non-adrenergic IPSPs

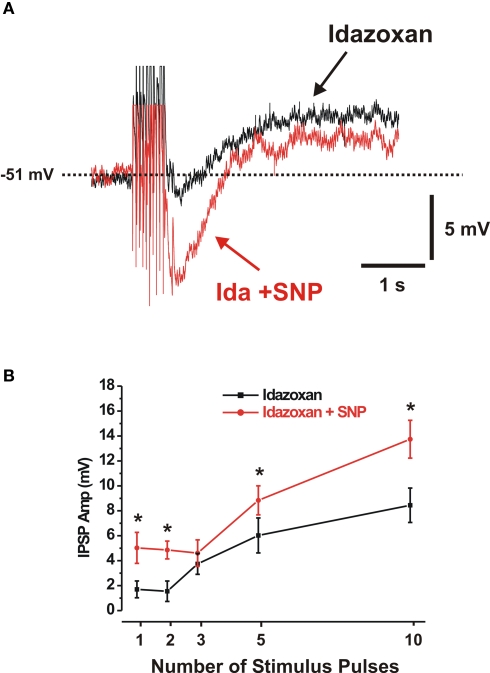

The IPSPs in these neurons are largely mediated by noradrenaline acting at α2-adrenoceptors, but a non-adrenergic component has also been reported (Mihara et al., 1987; Bornstein et al., 1988; Shen and Surprenant, 1993). To test whether the NO donor acted only on noradrenergic IPSPs, or if its effect was more general, the noradrenergic component was blocked using the α2-receptor antagonist idazoxan and the effects of SNP on the residual IPSPs was examined. Idazoxan (2 μM) depressed IPSPs evoked by 1–10 pulse trains (Figure 4) and abolished responses to local noradrenaline (not illustrated).

Figure 4.

Sodium nitroprusside enhances non-adrenergic IPSPs. (A) Ten-pulse non-adrenergic IPSP (idazoxan present, black control, red in SNP and idazoxan). (B) Quantitative data showing the effects of SNP (red line) on the amplitudes of 1-, 2-, 3-, 5- and 10-pulse non-adrenergic IPSPs. *P < 0.05.

The residual IPSPs in idazoxan were enhanced by SNP (Figure 4, n > 7), although this effect was not statistically significant for 3-pulse (n = 9) trains of stimuli.

The non-adrenergic IPSPs are partly mediated by SOM via at SSTR1 and SSTR2 receptors (Shen and Surprenant, 1993; Foong et al., 2010). SNP significantly enhanced hyperpolarizations evoked by locally applied SOM (Figures 3D–F, control SOM 20.5 ± 1.9, SNP 24.6 ± 2.2 mV; P = 0.02) indicating that its effects on the non-adrenergic IPSPs were post-synaptic.

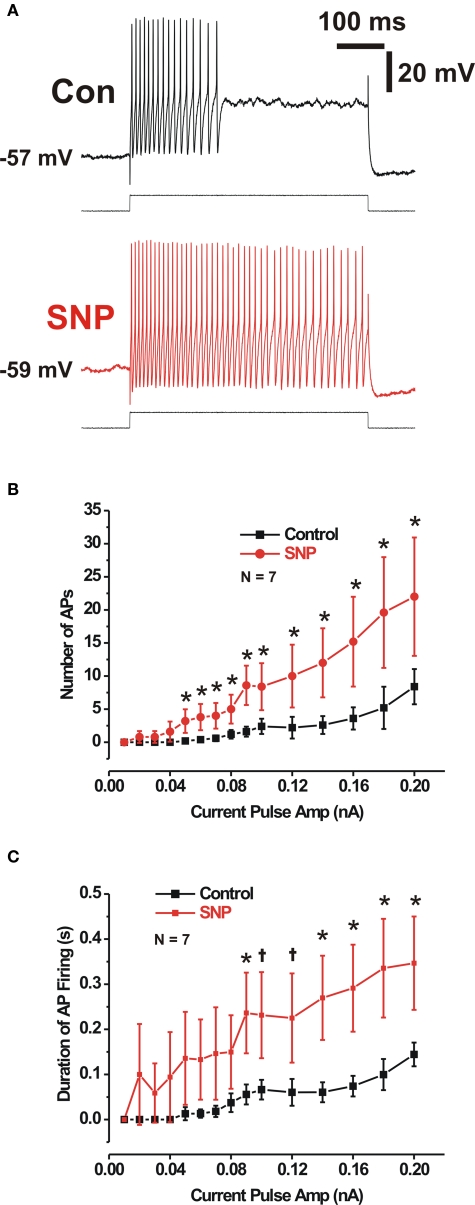

No modulates the excitability of submucosal neurons

In control preparations, long depolarizing current pulses initiate action potentials in VIP neurons, but only at the start of the depolarization (Figure 5, Gwynne et al., 2009). This firing pattern was markedly altered by SNP (100 μM), which greatly prolonged the firing of action potentials and increased the number fired by any given current pulse (500 or 1000 ms, Figure 5). Firing in SNP often continued throughout the depolarization (two of five cells tested with 500 ms pulses and five of seven cells tested with 1000 ms pulses), so values shown in Figure 5 for responses in SNP are underestimates. The increased firing produced by SNP was not due to an increase in the maximum firing frequency of these neurons, because maximum frequency was unaffected by SNP (control 46 ± 10 Hz, SNP 56 ± 7 Hz, P > 0.35, n = 7, two-tailed paired t test).

Figure 5.

Sodium nitroprusside increased the excitability of submucosal neurons displaying IPSPs. (A) Action potentials (APs) evoked by a 500-ms duration depolarizing current pulse in control (black), and in SNP (red). Quantitative data over a range of current amplitudes for AP number and firing duration (B,C). *P < 0.05 (two-tailed t test).

While SNP and NOLA had opposite effects on synaptic potentials, the same was not observed for neuronal excitability. NOLA did not consistently reduce the number of action potentials or duration of firing evoked by prolonged depolarization (P > 0.05, single-tailed paired t test, n = 6).

Discussion

Although NOS is found in nerve terminals and neuronal cell bodies throughout the enteric nervous system, there have been surprisingly few studies of the effects of either endogenous or exogenous NO on synaptic transmission at any site. The results of this present study indicate that NO enhances inhibitory synaptic transmission in the submucosal plexus via a post-synaptic mechanism, but paradoxically enhances excitability of the same neurons. The enhanced inhibitory transmission involved both the noradrenergic IPSPs evoked by sympathetic stimulation and the non-adrenergic IPSPs that apparently arise from enteric inhibitory interneurons with cell bodies in the myenteric plexus (Mihara et al., 1987; Bornstein et al., 1988; Foong et al., 2010). These changes are accompanied by a reduction in slow EPSP amplitudes, an effect confined to the non-purinergic component of these synaptic potentials (Foong and Bornstein, 2009b).

NO enhances IPSPs via a post-synaptic mechanism

This study clearly shows that the NO donor SNP enhances IPSPs, while blockade of endogenous production of NO depresses them. This is probably due increased post-synaptic efficacy of the transmitters involved, as the NO donor markedly enhanced hyperpolarizations evoked by both noradrenaline and SOM. This suggests that NO acts downstream of the α2-, SSTR1- and SSTR2-receptors, which mediate responses to noradrenaline and SOM in these neurons (North and Surprenant, 1985; Foong et al., 2010). Further, the changes in neural excitability also produced by NO were due to a post-synaptic effect and SNP substantially increases intracellular cGMP specifically in the VIP neurons (Young et al., 1993).

NO selectively depresses non-purinergic slow EPSPs in VIP neurons

The conclusion that NO acts post-synaptically to enhance IPSPs contrasts with earlier findings on the effects of SNP on myenteric neurons; i.e., that NO acted pre-synaptically to inhibit slow EPSPs (Tamura et al., 1993). In the present study, SNP did not alter slow EPSPs evoked by single stimuli, responses mediated by P2Y1 receptors (Hu et al., 2003; Monro et al., 2004; Foong and Bornstein, 2009b), but depressed slow EPSPs evoked by trains of stimuli, which are mediated by a non-purinergic mechanism (Foong and Bornstein, 2009b). Several transmitters that contribute to these non-purinergic slow EPSPs including glutamate acting at mGluR1 receptors (Foong and Bornstein, 2009b), but not 5-HT acting on 5-HT7 receptors (Foong and Bornstein, 2009a) or tachykinins acting on NK1 or NK3 receptors (Foong and Bornstein, 2009b). Thus, determining a site of action of NO released by SNP would be difficult. However, the selectivity for non-purinergic slow EPSPs and the apparent post-synaptic site of action for effects on IPSPs suggests a post-synaptic site of action for the suppression of the slow EPSPs.

While there are clear pharmacological differences between the two types of slow EPSPs, the underlying conductance changes are more controversial. There is little doubt that the non-purinergic slow EPSPs are mediated via a decrease in K+ conductance (Surprenant, 1984; Bornstein et al., 1986; Foong and Bornstein, 2009b), because they are associated with increased input resistance and reverse at about the K+ equilibrium potential. By contrast, there are conflicting reports about the P2Y1 mediated slow EPSPs with several studies indicating that they are associated with increased input resistance (Surprenant, 1984; Bornstein et al., 1986; Foong and Bornstein, 2009b), but a more detailed study has reported that they result from an increase in a non-specific cation conductance (Hu et al., 2003). Identification of the purinergic slow EPSP mechanism will aid in understanding the molecular site or sites of action of NO in the VIP neurons (see below).

NO enhances excitability of submucosal VIP neurons

A striking finding of this study was that, although synaptic inhibition was enhanced by the NO donor and slow synaptic excitation was partially suppressed, the overall excitability of the VIP neurons was greatly enhanced. This effect was seen as a reduction in the threshold depolarization needed to initiate action potentials and a greatly prolonged period of firing during depolarizing current pulses, but was not due to an increased the maximum rate of firing during such current pulses. The enhanced firing was similar to that seen in the same class of neurons after preincubation of preparations with cholera toxin in the intestinal lumen (Gwynne et al., 2009). It is also similar to the enhanced firing seen in some myenteric neurons after TNBS-induced inflammation (Nurgali et al., 2007), although increased firing is not seen in submucosal neurons after inflammation (Lomax et al., 2005).

Sodium nitroprusside induced increased duration of firing suggests that NO acts to suppress a slowly activating ion channel that reduces neuronal excitability and prevents a firing during long depolarizations. It is likely that this is a voltage-dependent K+ channel, but the literature is curiously silent about the expression of specific channels by submucosal neurons. Substantially more work is needed to reveal the membrane mechanisms via which NO enhances excitability. What can be said, however, is that it is unlikely that the effects of cholera toxin are mediated by NO, because they are not accompanied by increased IPSPs.

Endogenous NO has effects on synaptic transmission similar to the NO donor

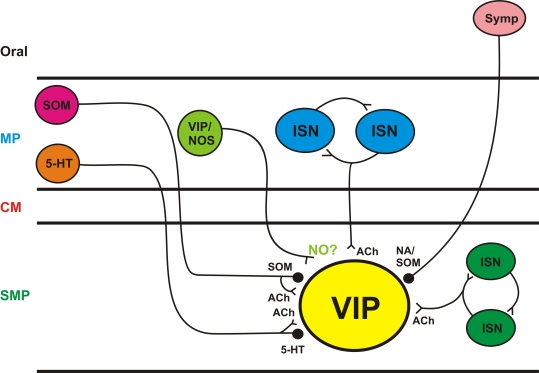

The synaptic effects of NO synthesis suppression – decreased IPSPs and increased slow EPSPs – were opposite to those of SNP. This indicates that there was an endogenous source of NO within the isolated preparations. This may have been residual mucosal tissue left behind in the dissection or mast cells. However, the failure of NOS inhibition to consistently modulate action potential firing suggests that release of endogenous NO was not tonic as expected if NO was coming from non-neural tissue. There are varicosities immunoreactive for NOS within the submucosal ganglia (Furness et al., 1994; Li et al., 1995) that would be excited to release NO by the focal stimulation used in this study. These NOS terminals are probably the source of the endogenous NO that modulates synaptic transmission. These terminals come from myenteric interneurons immunoreactive for both VIP and NOS and form ultrastructurally identifiable synapses with both VIP and NPY neurons (Li et al., 1995). The stimuli used in this study would be expected to excite these terminals along with the others ending on the VIP neurons (Figure 6) and so may well have produced NO release.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of inputs to submucosal VIP neurons VIP neurons receive synaptic inputs from many sources; sympathetic neurons (Symp) are responsible for noradrenergic IPSPs; myenteric and submucosal intrinsic sensory neurons (ISN) are excitatory; myenteric interneurons immunoreactive for serotonin (5-HT) or SOM are likely to mediate the non-noradrenergic IPSPs and myenteric neurons immunoreactive for VIP/nNOS are the probably source of endogenous NO released by electrical stimuli. SMP submucosal plexus, CM circular muscle, MP myenteric plexus, ACh acetylcholine, < denotes an excitatory synapse,  denotes an inhibitory synapse.

denotes an inhibitory synapse.

Functions of endogenous NO

At first glance it seems paradoxical that NO enhances inhibitory transmission and depresses some slow EPSPs, while simultaneously enhancing neural responses to depolarization. However, at least part of the paradox may be resolved when one considers that the stimuli used in this study would have simultaneously excited all the inputs to the VIP neurons. These neurons receive input from many sources (summarized in Figure 6) in different neural pathways. Thus, electrical stimulation cannot mimic the physiological drive going to these neurons.

Vasoactive intestinal peptide neurons receive excitatory inputs from the myenteric plexus and from other submucosal neurons (Bornstein et al., 1987; Moore and Vanner, 1998, 2000; Reed and Vanner, 2001). Submucosal intrinsic sensory neurons are the most likely source of excitatory input from within the submucosa, as these are the only submucosal neurons with significant numbers of terminals within submucosal ganglia (Evans et al., 1994; Reed and Vanner, 2001). There appears to be a sparse circuit of terminals arising from the submucosal VIP neurons (Costa and Furness, 1983, Reed and Vanner, 2001), but the great majority of VIP terminals come from myenteric neurons (Costa and Furness, 1983) and are also immunoreactive for nNOS (Li et al., 1995). Axons of the myenteric VIP/NOS neurons project anally within the myenteric plexus and then penetrate the circular muscle to supply submucosal ganglia with little or no projection within the submucosa itself (Costa and Furness, 1983). The transmitter from these neurons has not been identified. Submucosal ganglia are innervated by myenteric intrinsic sensory neurons that project only a short distance from their cell bodies before penetrating the circular muscle and have short projections in the submucosa (Furness et al., 1990). VIP neurons also receive inputs from SOM-and serotonin-immunoreactive interneurons (Foong et al., 2010) with cell bodies in the myenteric plexus (Costa et al., 1980; Furness and Costa, 1982). These neurons may be responsible for non-adrenergic IPSPs in the VIP neurons and run anally within the myenteric plexus before projecting to the submucosa and then running anally for several millimeters before forming synapses. This route is followed by the only identified physiological reflex pathway, which is excitatory (Reed and Vanner, 2007), and may be mediated by these neurons as each is immunoreactive for choline acetyltransferase as well as their inhibitory transmitters (Costa et al., 1996). VIP neurons also receive input from sympathetic axons that contain both noradrenaline and SOM (Costa and Furness, 1984). The complex inputs to VIP neurons suggest that one role for NO released by intermediate length VIP/nNOS interneurons is to tune the response to specific physiological stimuli. E.g., activity in these neurons would enhance firing due to local inputs from intrinsic sensory neurons, while increasing the inhibitory effect of the long anally projecting inhibitory interneurons or the sympathetic inputs. Thus, the VIP/nNOS interneurons may be “gatekeepers” that determine the balance between secretion and absorption locally within the mucosa.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by a grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council Australia (NHMRC Grant No. 40053) and Australian Postgraduate Awards (Kathryn A. Marks, Jaime Pei Pei Foong).

References

- Bornstein J. C., Costa M., Furness J. B. (1986). Synaptic inputs to immunohistochemically identified neurones in the submucous plexus of the guinea-pig small intestine. J. Physiol. 381, 465–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein J. C., Costa M., Furness J. B. (1988). Intrinsic and extrinsic inhibitory synaptic inputs to submucous neurones of the guinea-pig small intestine. J. Physiol. 398, 371–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein J. C., Furness J. B. (1988). Correlated electrophysiological and histochemical studies of submucous neurons and their contribution to understanding enteric neural circuits. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 25, 1–13 10.1016/0165-1838(88)90002-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein J. C., Furness J. B., Costa M. (1987). Sources of excitatory synaptic inputs to neurochemically identified submucous neurons of the guinea-pig small intestine. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 18, 83–91 10.1016/0165-1838(87)90137-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa M., Brookes S. J. H., Steele P. A., Gibbins I. L., Burcher E., Kandiah C. J. (1996). Neurochemical classification of myenteric neurons in the guinea-pig ileum. Neuroscience 75, 949–967 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00275-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa M., Furness J. B. (1983). The origins, pathways and terminations of neurons with VIP-like immunoreactivity in the guinea-pig small intestine. Neuroscience 8, 665–676 10.1016/0306-4522(83)90002-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa M., Furness J. B. (1984). Somatostatin is present in a subpopulation of noradrenergic nerve fibres supplying the intestine. Neuroscience 13, 911–920 10.1016/0306-4522(84)90105-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa M., Furness J. B., Llewellyn-Smith I. J., Davies B., Oliver J. (1980). An immunohistochemical study of the projections of somatostatin-containing neurons in the guinea-pig intestine. Neuroscience 5, 841–852 10.1016/0306-4522(80)90153-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson E. J., Spencer N. J., Hennig G. W., Bayguinov P. O., Ren J., Heredia D. J., Smith T. K. (2007). An enteric occult reflex underlies accommodation and slow transit in distal large intestine. Gastroenterology 132, 1912–1924 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.02.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans R. J., Jiang M. -M., Surprenant A. (1994). Morphological properties and projections of electrophysiologically characterized neurons in the guinea-pig submucosal plexus. Neuroscience 59, 1093–1100 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90308-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foong J. P. P., Bornstein J. C. (2009a). 5-HT antagonists NAN-190 and SB 269970 block a2-adrenoceptors in the guinea pig. Neuroreport 20, 325–330 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3283232caa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foong J. P. P., Bornstein J. C. (2009b). mGluR1 receptors contribute to non-purinergic slow excitatory transmission to submucosal VIP neurons of guinea-pig ileum. Front. Enteric Neurosci. 1:0. 10.3389/neuri.21.001.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foong J. P. P., Parry L. J., Gwynne R. M., Bornstein J. C. (2010). 5-HT1A, SST1 and SST2 receptors mediate inhibitory postsynaptic potentials in the submucous plexus of the guinea-pig ileum. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 298, G384–G394 10.1152/ajpgi.00438.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furness J. B., Costa M. (1982). Neurons with 5-hydroxytryptamine-like immunoreactivity in the enteric nervous system: their projections in the guinea-pig small intestine. Neuroscience 7, 341–349 10.1016/0306-4522(82)90271-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furness J. B., Li Z. S., Young H. M., Forstermann U. (1994). Nitric oxide synthase in the enteric nervous system of the guinea-pig – a quantitative description. Cell Tissue Res. 277, 139–149 10.1007/BF00303090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furness J. B., Trussell D. C., Pompolo S., Bornstein J. C., Smith T. K. (1990). Calbindin neurons of the guinea-pig small intestine: quantitative analysis of their numbers and projections. Cell Tissue Res. 260, 261–272 10.1007/BF00318629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garthwaite J. (2008). Concepts of neural nitric oxide-mediated transmission. Eur. J. Neurosci. 27, 2783–2802 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06285.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwynne R. M., Bornstein J. C. (2007). Synaptic transmission at functionally identified synapses in the enteric nervous system: roles for both ionotropic and metabotropic receptors. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 5, 1–17 10.2174/157015907780077141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwynne R. M., Ellis M., Sjovall H., Bornstein J. C. (2009). Cholera toxin induces sustained hyperexcitability in submucosal secretomotor neurons in guinea pig jejunum. Gastroenterology 136, 299–308 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst G. D. S., McKirdy H. C. (1975). Synaptic potentials recorded from neurones of the submucous plexus of guinea-pig small intestine. J. Physiol. 249, 369–385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H. -Z., Gao N., Zhu M. X., Liu S., Ren J., Gao C., Xia Y., Wood J. D. (2003). Slow excitatory synaptic transmission mediated by P2Y1 receptors in the guinea-pig enteric nervous system. J. Physiol. 550, 493–504 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.041731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecci A., Santicioli P., Maggi C. A. (2002). Pharmacology of transmission to gastrointestinal muscle. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2, 630–641 10.1016/S1471-4892(02)00225-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. S., Young H. M., Furness J. B. (1995). Do vasoactive intestinal peptide (vip)- and nitric oxide synthase-immunoreactive terminals synapse exclusively with vip cell bodies in the submucous plexus of the guinea-pig ileum? Cell Tissue Res. 281, 485–491 10.1007/BF00417865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomax A. E. G., Mawe G. M., Sharkey K. A. (2005). Synaptic facilitation and enhanced neuronal excitability in the submucosal plexus during experimental colitis in guinea-pig. J. Physiol. 564, 863–875 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.084285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyster D. J. K., Bywater R. A. R., Taylor G. S. (1995). Neurogenic control of myoelectric complexes in the mouse isolated colon. Gastroenterology 108, 1371–1378 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90684-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihara S., Nishi S., North R. A., Surprenant A. (1987). A non-adrenergic, non-cholinergic slow inhibitory post-synaptic potential in neurones of the guinea-pig submucous plexus. J. Physiol. 390, 357–365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monro R. L., Bertrand P. P., Bornstein J. C. (2004). ATP participates in three excitatory post-synaptic potentials in the submucous plexus of the guinea pig ileum. J. Physiol. 556, 571–584 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.060848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore B. A., Vanner S. (1998). Organization of intrinsic cholinergic neurons projecting within submucosal plexus of guinea pig ileum. Am. J. Physiol. 275, G490–G497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore B. A., Vanner S. (2000). Properties of synaptic inputs from myenteric neurons innervating submucosal S neurons in guinea pig ileum. Am. J. Physiol. 278, G273–G280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourad F. H., Barada K. A., Abdel-Malak N., Bou Rached N. A., Khoury C. I., Saade N. E., Nassar C. F. (2003). Interplay between nitric oxide and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide in inducing fluid secretion in rat jejunum. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 550, 863–871 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.043737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North R. A., Surprenant A. (1985). Inhibitory synaptic potentials resulting from a2-adrenoceptor activation in guinea-pig submucous plexus neurones. J. Physiol. 358, 17–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurgali K., Nguyen T. V., Matsuyama H., Thacker M., Robbins H. L., Furness J. B. (2007). Phenotypic changes of morphologically identified guinea-pig myenteric neurons following intestinal inflammation. J. Physiol. 583, 593–609 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.135947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed D. E., Vanner S. (2007). Mucosal stimulation activates secretomotor neurons via long myenteric pathways in guinea pig ileum. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 292, G608–G614 10.1152/ajpgi.00364.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed D. E., Vanner S. J. (2001). Converging and diverging cholinergic inputs from submucosal neurons amplify activity of secretomotor neurons in guinea-pig ileal submucosa. Neuroscience 107, 685–696 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00392-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts R. R., Bornstein J. C., Bergner A. J., Young H. M. (2008). Disturbances of colonic motility in mouse models of hirschprung's disease. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 294, G996–G1008 10.1152/ajpgi.00558.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts R. R., Murphy J. L., Young H. M., Bornstein J. C. (2007). Development of colonic motility in the neonatal mouse – studies using spatiotemporal maps. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 292, G930–G938 10.1152/ajpgi.00444.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen K. Z., Surprenant A. (1993). Somatostatin-mediated inhibitory postsynaptic potential in sympathetically denervated guinea-pig submucosal neurones. J. Physiol. 470, 619–635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer N. J., Bywater R. A. R., Taylor G. S. (1998). Disinhibition during myoelectric complexes in the mouse colon. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 71, 37–47 10.1016/S0165-1838(98)00063-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surprenant A. (1984). Slow excitatory synaptic potentials recorded from neurones of guinea-pig submucous plexus. J. Physiol. 351, 343–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Schemann M., Wood J. D. (1993). Actions of nitric oxide-generating sodium nitroprusside in myenteric plexus of guinea pig small intestine. Am. J. Physiol. 265, G887–G893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young H. M., McConalogue K., Furness J. B., Devente J. (1993). Nitric oxide targets in the guinea-pig intestine identified by induction of cyclic GMP immunoreactivity. Neuroscience 55, 583–596 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90526-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S. Y., Bornstein J. C., Furness J. B. (1995). Pharmacological evidence that nitric oxide may be a retrograde messenger in the enteric nervous system. Br. J. Pharmacol. 114, 428–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]