Abstract

The terpene synthase encoded by the sav76 gene of Streptomyces avermtilis was expressed in Escherichia coli as an N-terminal-His6-tag protein, using a codon-optimized synthetic gene. Incubation of the recombinant protein, SAV_76, with farnesyl diphosphate (1, FPP) in the presence of Mg2+ gave a new sesquiterpene alcohol avermitilol (2), whose structure and stereochemistry were determined by a combination of 1H, 13C, COSY, HMQC, HMBC, and NOESY NMR, along with minor amounts of germacrene A (3), germacrene B (4), and viridiflorol (5). The absolute configuration of 2 was assigned by 1H NMR analysis of the corresponding (R) and (S)-Mosher esters. The steady state kinetic parameters were kcat 0.040 ± 0.001 s−1 and Km 1.06 ± 0.11 μM. Individual incubations of recombinant avermitilol synthase with [1,1-2H2]FPP (1a), (1S)-[1-2H]-FPP (1b), and (1R)-[1-2H]-FPP (1c) and NMR analysis of the resulting avermitilols supported a cyclization mechanism involving the loss of H-1re to generate the intermediate bicyclogermacrene (7), which then undergoes proton-initiated anti-Markovnikov cyclization and capture of water to generate 2. A copy of the sav76 gene was reintroduced into S. avermitilis SUKA17, a large deletion mutant from which the genes for the major endogenous secondary metabolites had been removed, and expressed under control of the of the native S. avermitilis promoter rpsJp (sav4925). The resultant transformants generated avermitilol (2) as well as the derived ketone, avermitilone (8), along with small amounts of 3, 4, and 5. The biochemical function of all four terpene synthases found in the S. avermtilis genome have now been determined.

Streptomyces are gram-positive bacteria known for their production of an enormous variety of biologically active secondary metabolites.1 The growing number of completed Streptomyces genome sequences has revealed that only a fraction of the biosynthetic potential of these versatile bacteria has been uncovered.1–3 Genome mining has thus provided a powerful new tool for the discovery of both known and previously unknown natural products and the elucidation of new biochemical transformations and biosynthetic pathways.3

Streptomyces avermitilis, a well-studied member of this genus, is used for the industrial production of the important anthelminthic macrolide avermectin.2,4,5 Sequencing of the S. avermitilis genome has revealed four presumptive terpene synthase genes.4 One of these, ptlA (sav2998), encodes a pentalenene synthase,6 a second, geoA (sco6073), is a germacradienol/geosmin synthase,7 and a third, sav3032, encodes an epi-isozizaene synthase.8 The function of the remaining putative terpene synthase gene, sav76, has not previously been established. Two highly conserved Mg2+-binding motifs, characteristic of essentially all terpene cyclases, are evident in the predicted SAV_76 protein as an aspartate-rich 80DDQFD motif and the “NSE” triad motif, 239NDVYSLEKE.9 We now report that SAV_76 catalyzes the cyclization of farnesyl diphosphate (1, FPP) to a previously unknown tricyclic sequiterpene alcohol, which we have named avermitilol (2) (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Cyclization of FPP (1) to avermitilol (2)

A synthetic sav76 gene, with codons optimized for expression in E. coli, was cloned into the pET28a(+) expression vector. The resultant plasmid was transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) and used for high-level expression of recombinant SAV_76 protein carrying an N-terminal His6-tag, which was affinity-purified using Ni-NTA chromatography.

Incubation of purified recombinant SAV_76 with FPP in the presence of MgCl2 gave a sesquiterpene alcohol (2) (m/z 222) as the major enzymatic reaction product (85 %,), accompanied by germacrene A (3) (1 %), germacrene B (4) (5 %) and the known tricyclic sesquiterpene alcohol, viridiflorol (5) (3 %), as well as several unidentified minor sesquiterpene products, as determined by capillary GC-MS analysis. The steady-state kinetic parameters for the SAV_76-catalyzed reaction, measured by monitoring the formation of 2 using [1-3H]FPP were kcat 0.040 ± 0.001 s−1 and Km 1.06 ± 0.11 μM, comparable to those for typical terpene synthases.6–9

The structure of sesquiterpene alcohol 2 was assigned by a combination of 1-D and 2-D NMR spectroscopy. Key resonances observed in the 1H NMR and HMQC spectra were the two upfield methine proton signals corresponding to H-6 (δ 0.47; C-6 22.2 ppm) and H-7 (δ 0.53; C-7 19.3 ppm) attached to a cyclopropane ring, as well as the H-5 (δ 0.94; C-5 40.5 ppm) and H-9ax (δ 0.63; C-9 36.8 ppm) protons shielded by the cyclopropyl ring. Four methyl signals were also observed, corresponding to H-12 (δ 0.99, s; C-12 29.8 ppm), H-13 (δ 0.91, s; C-13 15.6 ppm), H-14 (δ 0.87, s; C-14 14.6 ppm), and H-15 (δ 1.00, d, J=7.5 Hz; C-15 15.4 ppm), in addition to the alcohol (δ 1.24) and carbinyl protons, H-1 (δ 3.13; C-1 79.7 ppm). The absence of any olefinic protons or allylic methyl groups indicated that 2 was a tricyclic, cyclopropane-containing, secondary alcohol.

The 1H-13C connectivity in 2 was established by a combination of HMQC and HMBC spectroscopy. Long-range 1H-13C correlations defining the cyclopropane ring were observed between the methyl H-13 protons and C-6, C-7, and C-11 of the cyclopropane ring, in addition to the reciprocal crosspeaks between the protons and carbons of the geminal methyl pair. Pairwise 2- and 3-bond correlations between H-5 and C-1, C-4, C-6, C-9, C-10, C-11, C-14, and C-15 established the central position of the bridgehead H-5 proton. Additional crosspeaks between H-1 and C-2, C-3, C-9, C-10, and C-14 as well as between H-9ax and C-1, C-5, C-8, C-10, and C-14 established the remaining connectivity.

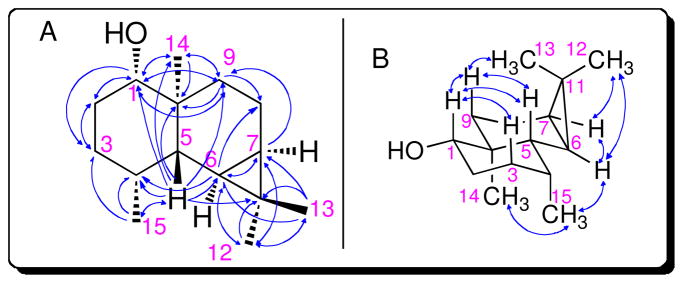

The relative stereochemistry of sesquiterpene 2 was readily deduced from the NOESY NMR spectrum. Major NOESY correlations established the presence of a trans-decalin ring system with a cis-fused dimethylcyclopropane ring as deduced from NOESY crosspeaks among the H-6 and H-7 methine protons and the H-12 methyl signals. The H-6 proton also displayed a cross peak to the H-15 secondary methyl, which itself had a crosspeak to the H-14 methyl at the ring junction. Additional NOESY correlations were also observed between H-1 and each of its 1,3-diaxial partners H-3ax, H-5 and H-9ax. This H-9ax proton signal also displayed crosspeaks with both H-5 and the H-13 methyl.

The absolute configuration of 2 was assigned by 1H NMR analysis of the derived (R) and (S)-Mosher esters of the C-1 secondary alcohol,10 leading to the assignment of the absolute configuration of 2 as 1S, 4R, 5S, 6R, 7R, 10S. Avermitilol (2) is a new tricyclic sesquiterpene alcohol whose isolation has not been previously reported.11

To probe the stereochemical course of the SAV_76-catalyzed reaction, recombinant SAV_76 was incubated in separate experiments with [1,1-2H2]FPP (1a), (1S)-[1-2H]FPP (1b) and (1R)-[1-2H]FPP (1c) (Scheme 1). Unlabeled 2 resulted from the incubation with (1R)-[1-2H]FPP, while [6-2H]-2a was formed in incubations with [1,1-2H2]FPP and with (1S)-[1-2H]FPP. The GC-mass spectra of 2a and 2b had parent peaks m/z 223, corresponding to [M+1]+, indicating that the H-1si proton of FPP is retained while the H-1re of FPP is lost during formation of the cycloproprane ring of avermitilol (2). The position of the deuterium label in [6-2H]-2a was established by the absence of the normal H-6 proton signal at δ 0.47. The concomitant loss of the vicinal couplings between H-6 and both H-5 and H-7 in [6-2H]-2a also supported the assigned position of the deuterium label.

These labeling experiments are consistent with a mechanism for the formation of avermitilol (2) in which FPP undergoes initial ionization with electrophilic attack on the si-face of the distal double bond to form a germacradienyl cation (6) (Scheme 1). Insertion of the 2-propyl cation into the C-H bond with loss of the original H-1re proton of FPP would result in formation of the enzyme-bound bicyclogermacrene (7). Proton-initiated anti-Markovnikov cyclization of 7 and quenching of the tricyclic secondary carbocation by water would yield avermitilol (2). Consistent with this proposed mechanism is the observed formation of the minor products germacrene A (3) and B (4) by alternative deprotonation of the germacradienyl cation. The coproduction of the isomeric viridiflorol (5) can be explained by competing proton-initiated Markovnikov cyclization of bicyclogermacrene to form the cis-fused 5,7-ring system followed by capture of water.

Although, avermitilol (2) was not detected in extracts of wild-type S. avermitilis, the in vivo activity of the sav76 gene could be directly demonstrated using a genome-minimized mutant, S. avermitilis SUKA17, from which >1-Mb of DNA had been deleted, including the genes for the major endogenous secondary metabolites produced by the parent strain.12 GC-MS analysis of hexane extracts of cultures of S. avermitilis SUKA17 harboring sav76 under control of the native S. avermitilis promoter rpsJp (sav4925) showed the presence of avermitilol (2, 15%,), accompanied by small quantities of germacrene A (3, 10%), germacrene B (4, 5%), and viridiflorol (5, 2%) (Figure 1). The major component of the mixture was ketone avermitilone (8, 67 %, m/z 220), whose structure was confirmed by 1H and 13C NMR and direct comparison with a reference sample prepared by oxidation of 2 with pyridinium chlorochromate. Cointroduction of the ptlB gene (sav2997), encoding the native S. avermitilis FPP synthase, along with sav76 increased the titers of both 2 and 8. The formation of avermitilone (8) may result from adventitious oxidation of 2 by an endogeneous dehydrogenase, since no dehydrogenase gene is evident in the genome of S. avermitilis immediately upstream or downstream of the native sav76 cyclase gene.

Figure 1.

A. HMBC and B. NOESY correlations for 2.

We have now assigned the biochemical functions of all four terpene synthases originally revealed by the sequencing of the S. avermitilis genome.6–8 Avermitilol (2) is a new sequiterpene whose isolation has not previously been reported. The sav76 gene product has one close ortholog, SSAG_00457 (Uniprot ID B4UXV1) which is found in Streptomyces sp. Mg1, with 78% identity and 85% positive matches over 334 amino acids.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

GC-MS analysis of production of avermitilol (2) and avermitilone (8) along with viridiflorol (5), germacrene B (4) and germacrene A (3) by transformed S. avermitilis SUKA17. A. Control with plasmid pKU460. B. pKU460-rpsJP::sav76. C. pKU460-rpsJP:: sav76-ptlB.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant GM30301 (D.E.C.), and by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan (MEXT) and from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) 20310122 (H.I.). We thank Tun-Li Shen for assistance with mass spectrometry and Russell Hopson for assistance with NMR.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Sequence comparisons, experimental methods, and NMR and GC-MS data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References and Notes

- 1.Bentley SD, et al. Nature. 2002;417:141–147. doi: 10.1038/417141a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Omura SM, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:12215–12220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211433198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Walsh CT, Fischbach MA. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:2469–2493. doi: 10.1021/ja909118a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Corre C, Challis GL. Nat Prod Rep. 2009;26:977–986. doi: 10.1039/b713024b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ikeda H, Ishikawa J, Hanamoto A, Shinose M, Kikuchi H, Shiba T, Sakaki Y, Hattori M, Omura S. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:526–531. doi: 10.1038/nbt820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamb DC, Ikeda H, Nelson DR, Ishikawa J, Skaug T, Jackson C, Omura S, Waterman MR, Kelly SL. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;307:610–619. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01231-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tetzlaff CN, You Z, Cane DE, Takamatsu S, Omura S, Ikeda H. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6179–6186. doi: 10.1021/bi060419n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cane DE, He X, Kobayashi S, Omura S, Ikeda H. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2006;59:471–479. doi: 10.1038/ja.2006.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takamatsu S, Lin X, Nara A, Komatsu M, Cane DE, Ikeda H. Microb Biotech. 2010;3:0000. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2010.00209.x. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christianson DW. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3412–3442. doi: 10.1021/cr050286w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoye TR, Jeffrey CS, Shao F. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2451–2458. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.A commercially available stereoisomer of 2, of unspecified stereochemistry and origin, is listed in CAS (Registry No 1008931-42-7) but with no literature references. We have determined the full relative stereochemistry of this stereoisomer (Supporting Information) and shown that it is distinct from 2 by direct NMR and GC-MS comparison.

- 12.Komatsu M, Uchiyama T, Omura S, Cane DE, Ikeda H. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:2646–2651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914833107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.