Abstract

This manuscript reviews the controversial relationship between hypertension and initiation of kidney disease. We focus on ethnic differences in renal histopathology and associated gene variants comprising the spectrum of MYH9-nephropathy.

Purpose of review

Treating mild to moderate essential hypertension in non-diabetic African Americans fails to halt nephropathy progression; while hypertension control slows nephropathy progression in European Americans. The pathogenesis of these disparate renal syndromes is reviewed.

Recent findings

The non-muscle myosin heavy chain 9 gene (MYH9) is associated with a spectrum of kidney diseases in African Americans, including idiopathic focal global glomerulosclerosis historically attributed to hypertension, idiopathic focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, and the collapsing variant of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (HIV-associated nephropathy). Risk variants in MYH9 likely contribute to the failure of hypertension control to slow progressive kidney disease in non-diabetic African Americans.

Summary

Early and intensive hypertension control fails to halt progression of “hypertensive nephropathy” in African Americans. Genetic analyses in patients with essential hypertension and nephropathy attributed to hypertension, FSGS and HIVAN reveal that MYH9 gene polymorphisms are associated with a spectrum of kidney diseases in this ethnic group. Mild to moderate hypertension may cause nephropathy in European Americans with intra-renal vascular disease improved by the treatment of hypertension, hyperlipidemia and smoking cessation.

Keywords: African Americans, CHGA, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, genetics, hypertensive nephrosclerosis, MYH9

Introduction

The causes of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in the USRDS database are provided by thousands of nephrologists without standardized diagnostic criteria and frequently without kidney biopsies. These diagnoses may not be accurate and physician bias plays a major role in disease classification1–5 When nephrologists were provided with identical clinical histories in non-diabetic patients having low level proteinuria and hypertension, they were twice as likely to diagnose hypertensive kidney disease in AA and more likely to diagnose chronic glomerulonephritis in EA6. Nonetheless, nephropathy classified as secondary to hypertension is consistently reported as the second most common cause of ESRD in the U.S.7. Nearly one-third of AA initiating dialysis in the U.S. are labeled with hypertension-associated ESRD, in contrast to 25% of European Americans7.

Many attribute the excess frequency of hypertensive nephropathy in AA to the higher prevalence and greater severity of high blood pressure, as well as lower socioeconomic status and poorer access to medical care. However, McClellan et al. reported that ethnic differences in the relative risk of hypertensive renal failure persisted after adjustment for age, sex, and differences in prevalence and severity of hypertension between races8. In addition, Rostand et al. reported that hypertensive AA had twice the incidence of declining renal function compared to EA, despite similar initial serum creatinine concentration, initial and treated blood pressures, number of missed office visits and antihypertensive medications prescribed9. The Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT) also detected a significant decline in kidney function in hypertensive AA compared with non-AA, despite equivalent hypertension control in both ethnic groups10. Pharmacologic treatment of mild-moderate hypertension in AA has little impact on the incidence of chronic renal failure, whereas it significantly reduces the progression of CKD in EA, along with treatment of hyperlipidemia and smoking cessation10–12.

If mild to moderate hypertension commonly caused kidney failure in AA, early and successful blood pressure control would be expected to reduce the incidence of renal functional decline13. However, the Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program (HDFP), MRFIT, and African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK) trials uniformly revealed that strict blood pressure control in hypertensive African Americans led to similar declines in renal function compared to standard blood pressure control, even using angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors10;14;15

When histopathology was available, AA clinically labeled with “hypertensive nephrosclerosis” typically had focal global and/or focal segmental glomerulosclerosis16;17. An important finding from AASK study was that individuals who underwent kidney biopsy had fairly uniform histology with focal global glomerulosclerosis, interstitial fibrosis and renal microvascular changes, although only 39 patients were evaluated. The vascular changes historically ascribed to hypertension (intimal hyperplasia, luminal narrowing and thickening of the media in small intra-renal blood vessels) did not correlate with systemic blood pressure, suggesting that high blood pressure was not causative. These findings raised the possibility that a primary kidney disease was present and caused secondarily elevated blood pressure17.

Marcantoni et al. compared the presence of renal histologic changes in EA and AA given the clinical diagnosis “hypertensive nephrosclerosis”18. Marked ethnic variation was observed, African Americans more often had solidified glomerulosclerosis and EA had obsolescent and collagen-rich glomerulosclerosis. African Americans with non-diabetic nephropathy were generally younger than EA, had similar mean arterial blood pressures, and more prominent arteriolosclerotic changes. The presence of ethnic differences in renal histology, coupled with the relentless renal functional decline in AA with treated hypertension, underscore that the primary lesion in AA with “hypertensive” nephropathy resides in the kidney. In contrast, treating small vessel disease in hypertensive EA by blood pressure lowering and reducing other cardiovascular disease risk factors suggests that hypertension truly initiates kidney disease in these patients.

It is also interesting that AA with hypertension and CKD more often progress to dialysis, whereas EA are more likely to die from cardiovascular causes. This pattern suggests the presence of disparate disease processes between ethnic groups, with renal-limited diseases in AA accounting for less severe systemic atherosclerosis with improved survival19.

Genetic determinants of non-diabetic kidney disease

The major breakthrough in our understanding of common complex kidney disease came with identification of the association between the non-muscle myosin heavy chain 9 gene (MYH9) and idiopathic and secondary forms of FSGS. Marked familial aggregation of kidney disease is observed in AA, often with different causes of kidney disease in family members20. Familial aggregation occurs independently from socioeconomic factors21;22 suggesting the presence of a generalized renal failure susceptibility gene. A major gene was recently discovered using Mapping by Admixture Linkage Disequilibrium, a technique valuable in admixed populations displaying ethnic differences in disease frequency. African Americans are an admixed population consisting of approximately 80% African and 20% European genetic make-up. African Americans have a four fold or greater excess risk of all-cause ESRD compared to EA23–25 and have particularly high rates of HIVAN and idiopathic FSGS26–29.

Kopp et al. initially identified excess African ancestry on chromosome 22p in AA with idiopathic FSGS and HIV-associated collapsing FSGS, compared to AA30. Fine mapping under the admixture peak identified MYH9 as the associated gene. MYH9 was associated with clinically diagnosed “hypertensive ESRD” in AA as well30;31. The Family Investigation in Nephropathy and Diabetes (FIND) Study rapidly replicated association in several non-diabetic forms of ESRD in AA, including idiopathic FSGS, HIVAN and clinically diagnosed “hypertensive-ESRD”32. FIND reported that the population-attributable risk from MYH9 in AA with non-diabetic ESRD was 70% (70% of non-diabetic cases of ESRD in AA would disappear if MYH9 risk variants were replaced with the neutral/protective variants more often found in European-derived populations). These studies demonstrated that ethnic differences in susceptibility to non-diabetic ESRD were largely due to heredity, not socio-economic factors or ethnic differences in access to care. Risk variants in MYH9 are present in 60% of all AA, in contrast to 4% of EA. Ethnic disparities in gene frequency account for much of the ethnic variation in risk for non-diabetic ESRD. The importance of MYH9 in the disease historically labeled “hypertensive ESRD” was extended in 696 cases diagnosed by their nephrologists, compared with 948 non-nephropathy controls recruited at Wake Forest33. Strong evidence of association was confirmed, with single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) odds ratios (OR) as high as 3.4. Thus, the spectrum of MYH9-associated nephropathies in AA encompasses idiopathic FSGS, HIVAN, and those with the clinical diagnosis “hypertensive ESRD”. MYH9 is an overarching renal failure susceptibility gene, acting independently from high blood pressure, hyperglycemia, and HIV infection. MYH9 was recently shown to underlie approximately 16% of type 2 diabetes-associated ESRD in AA, although it remains unclear whether the disease was FSGS with coincident diabetes or classic diabetic nephropathy.34

Does hypertension “trigger” MYH9-assocciated kidney disease?

Confirmation that MYH9 was associated with ESRD in multiple AA cohorts raised the question of whether hypertension might cause ESRD in individuals inheriting two MYH9 risk variants. It was necessary to evaluate large numbers of AA and EA with essential hypertension and measures of proteinuria and kidney function to determine whether MYH9 was associated with elevated blood pressure in the absence of kidney disease. National Heart Lung and Blood Institute-sponsored Hypertension Genetics (HyperGEN) Study samples were analyzed35. HyperGEN included nearly 1,500 hypertensive AA and 1,500 hypertensive EA with preserved kidney function and measures of albuminuria36. The most striking finding from HyperGEN was that MYH9 risk allele frequencies were no different in hypertension-enriched cohorts compared to ethnically-matched general populations35. Moreover, MYH9 was weakly associated with albuminuria in hypertensive AA, but not in hypertensive EA, an effect likely related to inclusion of small numbers of individuals with pre-existing FSGS, as mild-moderate CKD was not an exclusion criterion

To convince those skeptical that high blood pressure does not frequently cause kidney disease in African Americans, it was important to test for MYH9 gene associations in cases fitting rigorous clinical criteria for hypertensive nephropathy. AASK participants were ideal, since they were uniformly hypertensive, lacked diabetes and had a maximum of 2.5 grams of urinary protein excretion per day. Four MYH9 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been evaluated in 497 AASK participants. SNP rs4821481, located in the E1 haplotype that is strongly associated with FSGS, HIVAN and “hypertensive ESRD” was strongly associated with kidney disease in AASK participants (OR 1.63; p=6.5×10−5, recessive). Increasing strength of association was detected in AASK participants with progressive nephropathy and serum creatinine concentrations exceeding 3 mg/dl (OR 2.33; p=2.4×10−6, recessive)37. Among the 161 AASK subjects with serum creatinine concentrations ≥ 3 mg/dl, MYH9 SNPs rs11912763 (OR 2.69; p=0.008, recessive) and rs1005570 (OR 1.57; p=0.027, recessive) were also strongly associated.

The spectrum of MYH9-associated kidney diseases in AA now extends from clinically diagnosed hypertensive nephropathy with focal global glomerulosclerosis and interstitial fibrosis on biopsy in AASK participants to ESRD historically attributed to hypertension. Moreover, MYH9 exhibits the strongest disease association yet detected for common complex human diseases, as seen in idiopathic FSGS and HIVAN. The magnitude of association reveals the presence of a Mendelian-like effect in non-diabetic kidney disease. MYH9 is also strongly associated with idiopathic FSGS in EA and development of CKD in Europeans30;38. However, the frequency of kidney disease related to MYH9 in European-derived populations is far lower than in AA due to the reduced frequency of risk alleles. Finally, chromogranin A gene (CHGA) polymorphisms are also associated with hypertensive ESRD in AA.39;40

Myosin and MYH9

The MYH9 gene encodes non-muscle myosin class II isoform IIA41. Myosins constitute a superfamily of proteins interacting with actin and grouped into 15 classes42. Myosin class II is subdivided into smooth- and non-smooth muscle myosin II. These myosins are structurally similar and composed of two heavy and two light chains that polymerize and interact with actin. Non-muscle myosin heavy chains (NMMHC) exist in three isoforms (NMMHC-A, NMMHC-B, NMMHC-C), each encoded by different genes (MYH9, MYH10 and MYH14, respectively, on chromosomes 22q12.3, 17p13.3, and 19p13.3)43, subdividing non-smooth muscle myosin II into 3 isoforms: IIA, IIB, and IIC42.

Non-smooth muscle myosin II isoforms are variably expressed in different tissues. Platelets express only NMMHC-A (II-A)44, while fetal and adult human kidneys express isoforms IIA and IIB43;45. Isoform IIA is expressed mainly in glomeruli of mature kidneys (podocytes and mesangial cells), arteriolar and peritubular capillaries43;45. Within podocytes, MYH9 protein localizes mainly in the foot processes as a continuous narrow layer underneath the plasma membrane45.

Myosin IIA is involved in cellular contractility, migration, phagocytosis, actin stress fiber organization, maintenance of cell shape and polarity, cell-cell contact and focal adhesion, and intracellular organelle trafficking46;47. Alterations in myosin IIA protein are clearly relevant to human disease. Heterozygous mutations in MYH9 cause the MYH9-related disease spectrum (MYH9-RD) including May-Hegglin Anomaly, Sebastian Syndrome, Fechtner Syndrome, and Epstein Syndrome (Table 1)48. Patients with MYH9-RD universally exhibit macrothombocytopenia, while other phenotypic features (leukocyte inclusion bodies, deafness, cataracts, and nephritis) are variably present. The presence of renal manifestations denotes Fechtner Syndrome (with leukocyte inclusions, sensorineural deafness and catarcts) or Epstein syndrome (absence of leukocyte inclusions)48. Renal disease in these related syndromes manifests as glomerulopathy with hematuria, proteinuria, and progressive renal failure with ESRD in the fifth decade, although it has been reported in childhood49. Histologic data are scanty and include mesangial matrix expansion, mesangial cell proliferation, podocyte foot process effacement, variable degrees of capillary wall basement membrane thickening and basket-weave splitting, leading to global glomerulosclerosis in a case report containing repeat kidney biopsies49. Wide phenotypic variability is seen, with single mutations in a family or unrelated individuals causing a spectrum of renal manifestations45. This fostered the concept that MYH9 syndromes are not distinct entities, but a single disorder with variable manifestations48.

Table 1.

MYH9 - disease associations

| Idiopathic FSGS |

| Focal global glomerulosclerosis (previously labeled “hypertensive renal disease”) |

| Collapsing FSGS (HIVAN & C1q nephropathy) |

| Fechtner syndrome; Sebastian syndrome |

| Autosomal dominant macrothrombocytopenia (May-Hegglin related disorders) |

| Schizophrenia (subgroup with preserved attention and executive function) |

| Congenital cleft lip and/or cleft palate |

MYH9 and glomerulosclerosis - potential pathogenetic mechanisms

A healthy podocyte cytoskeleton is required to maintain cellular architecture and fulfill the filtration barrier function50;51. Mutations in genes encoding podocyte proteins interacting with the actin cytoskeleton, including alpha-actinin 452, CD2-associated protein53 and synaptopodin54 are associated with FSGS. Myosin IIA is a component protein of the podocyte cytoskeleton55. Dysregulated podocyte myosin function and consequent actin cytoskeleton abnormalities might lead to inability to withstand hydraulic pressure and maintain capillary integrity, foot process retraction, quantitative diminution of glomerular basement membrane collagen IV synthesis45;56, and resultant glomerulosclerosis.

Epithelial tissues depend heavily on cell-cell adhesions, requiring correct localization of junctional components such as E-cadherin, zonula occludens and β-catenin for function. Myosin II is critical for concentrating E-cadherin at these sites57 and loss of E-cadherin may be involved in epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)58. Glomerular EMT has been proposed as important in development of glomerular disease59,60 and provide a possible link between MYH9 and glomerulosclerosis.

Platelet influx in the glomerulus has also been implicated in glomerulosclerosis and glomerular obsolescence in animal models using renal ablation61–63. As MYH9 polymorphisms are associated with syndromes characterized by abnormal platelet size and function64, glomerular platelet accumulation with resultant ischemia and release of TGF-β and PDGF could potentiate MYH9-associated nephropathy65;66.

Gene-gene and gene-environment interactions in MYH9-nephropathy

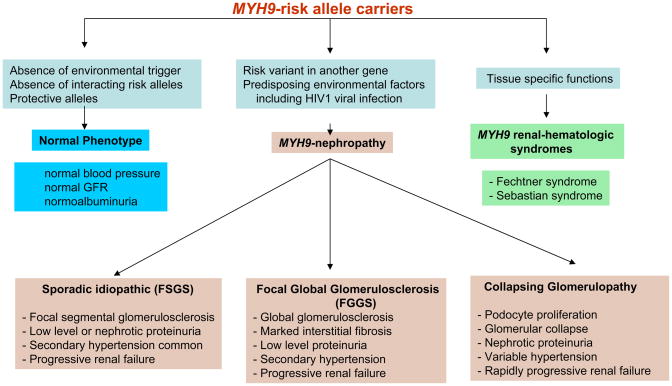

Although MYH9 demonstrates strong association with human disease, inheriting two MYH9 risk variants appears insufficient to initiate nephropathy. Approximately 4% of AA inheriting two MYH9 risk variants developed idiopathic FSGS, while approximately 20% with HIV infection and two risk variants developed collapsing FSGS or HIVAN (Jeffrey Kopp, personal communication). This demonstrates that HIV1 viral infection, an environmental factor, yields a fivefold increase in risk. Importantly, approximately 80% of genetically susceptible AA with HIV infection will not develop HIVAN and 96% of HIV-negative AA risk homozygotes will not develop FSGS. In the absence of HIV infection, C1q nephropathy can also manifest a collapsing phenotype in the presence of MYH9 risk variant homozygosity.67 This strongly implicates a “second hit” whereby individuals with genetic susceptibility to kidney disease require an additional factor(s) to initiate nephropathy. We believe that MYH9 gene-gene and MYH9 gene-environment interactions exist (Figure 1). For example, it will be important to evaluate MYH9 gene products for interaction with podocin and other proteins comprising the podocyte cytoskeleton and slit diaphragm.

Figure 1.

Classification and postulated mechanisms for the MYH9-associated nephropathies

Environmental factors such as HIV infection can clearly trigger MYH9-associated nephropathy. It will be important to evaluate the roles of nephropathic viruses including polyoma viruses and parvovirus B19. It is also possible that lymphotropic viruses related to HIV1 initiate kidney disease in susceptible AA and HTLV-1, HTLV-2, CMV, and Human Herpes 6 are prime candidates, although HIV1 directly infects podocytes.

These possibilities provide new hope for preventing kidney disease in those with genetic predisposition from MYH9. If viral infections initiate glomerulosclerosis, vaccines preventing infection could prevent renal insufficiency. As aggressive blood pressure control and use of ACE-inhibitors fail to halt progression of MYH9-associated kidney diseases, novel strategies to maintain podocyte cytoskeletal architecture have the potential to prevent glomerulosclerosis in AA with the disorder that has historically been labeled hypertensive nephrosclerosis.

CONCLUSIONS

Longstanding physician bias and misclassification have confused the classification of chronic forms of nephropathy. High blood pressure is not a common inciting factor for hypertensive nephrosclerosis in AA. In contrast, small vessel disease related to high blood pressure and other cardiovascular risk factors is often present in older EA given this diagnosis. Nonetheless, it remains critical to aggressively treat high blood pressure in those with (and at risk for) kidney disease. Hypertension accelerates nephropathy progression in all proteinuric kidney diseases68 and contributes to heart failure, myocardial infarction and stroke69–71. Seventy percent of AA with non-diabetic kidney disease fall into the spectrum of MYH9-associated nephropathy, ranging from focal global glomerulosclerosis in AASK participants, to sporadic FSGS, to collapsing glomerulopathy related to HIV infection. It is unclear why these different histologic disease patterns develop, although it is tempting to speculate that different modifier genes or environmental factors interacting with MYH9 dictate renal lesions. These recent genetic studies made major contributions toward untangling the complex relationship between high blood pressure and initiation of kidney disease. MYH9-related podocyte cytoskeleton dysregulation with progressive nephron loss likely cause secondary hypertension in African Americans labeled as having hypertensive nephropathy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants RO1 DK070941 and RO1 DK084149 (BIF).

Abbreviations

- AA

African American(s)

- EA

European American(s)

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Reference List

- 1.Freedman BI, Tuttle AB, Spray BJ. Familial predisposition to nephropathy in African-Americans with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;25(5):710–713. doi: 10.1016/0272-6386(95)90546-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsu CY. Does non-malignant hypertension cause renal insufficiency? Evidence-based perspective. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2002;11:267–272. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200205000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marin R, Gorostidi M, Fernandez-Vega F, varez-Navascues R. Systemic and glomerular hypertension and progression of chronic renal disease: the dilemma of nephrosclerosis. Kidney Int Suppl. 2005:S52–S56. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.09910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schlessinger SD, Tankersley MR, Curtis JJ. Clinical documentation of end-stage renal disease due to hypertension. Am J Kidney Dis. 1994;23:655–660. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)70275-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zarif L, Covic A, Iyengar S, Sehgal AR, Sedor JR, Schelling JR. Inaccuracy of clinical phenotyping parameters for hypertensive nephrosclerosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15:1801–1807. doi: 10.1093/ndt/15.11.1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perneger TV, Whelton PK, Klag MJ, Rossiter KA. Diagnosis of hypertensive end-stage renal disease: effect of patient’s race. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;141:10–15. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Renal Data System. Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Bethesda, MD: 2008. USRDS 2008 Annual Data Report. http://www.usrds.org. 2009. Ref Type: Generic. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McClellan W, Tuttle E, Issa A. Racial differences in the incidence of hypertensive end-stage renal disease (ESRD) are not entirely explained by differences in the prevalence of hypertension. Am J Kidney Dis. 1988;12:285–290. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(88)80221-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rostand SG, Brown G, Kirk KA, Rutsky EA, Dustan HP. Renal insufficiency in treated essential hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:684–688. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198903163201102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker WG, Neaton JD, Cutler JA, Neuwirth R, Cohen JD. Renal function change in hypertensive members of the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Racial and treatment effects. The MRFIT Research Group. JAMA. 1992;268:3085–3091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shepherd J, Kastelein JJP, Bittner V, Deedwania P, Breazna A, Dobson S, Wilson DJ, Zuckerman A, Wenger NK for the Treating to New Targets Investigators. Effect of Intensive Lipid Lowering with Atorvastatin on Renal Function in Patients with Coronary Heart Disease: The Treating to New Targets (TNT) Study. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2007;2:1131–1139. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04371206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phisitkul K, Hegazy K, Chuahirun T, Hudson C, Simoni J, Rajab H, Wesson DE. Continued smoking exacerbates but cessation ameliorates progression of early type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Am J Med Sci. 2008;335:284–291. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318156b799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopes AA. Relationships of race and ethnicity to progression of kidney dysfunction and clinical outcomes in patients with chronic kidney failure. Adv Ren Replace Ther. 2004;11:14–23. doi: 10.1053/j.arrt.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wright JT, Jr, Bakris G, Greene T, Agodoa LY, Appel LJ, Charleston J, Cheek D, Douglas-Baltimore JG, Gassman J, Glassock R, Hebert L, Jamerson K, Lewis J, Phillips RA, Toto RD, Middleton JP, Rostand SG. Effect of blood pressure lowering and antihypertensive drug class on progression of hypertensive kidney disease: results from the AASK trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2421–2431. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shulman NB, Ford CE, Hall WD, Blaufox MD, Simon D, Langford HG, Schneider KA. Prognostic value of serum creatinine and effect of treatment of hypertension on renal function. Results from the hypertension detection and follow-up program. The Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program Cooperative Group. Hypertension. 1989;13:I80–I93. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.13.5_suppl.i80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freedman BI, Iskander SS, Buckalew VM, Jr, Burkart JM, Appel RG. Renal biopsy findings in presumed hypertensive nephrosclerosis. Am J Nephrol. 1994;14:90–94. doi: 10.1159/000168695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fogo A, Breyer JA, Smith MC, Cleveland WH, Agodoa L, Kirk KA, Glassock R. Accuracy of the diagnosis of hypertensive nephrosclerosis in African Americans: a report from the African American Study of Kidney Disease (AASK) Trial. AASK Pilot Study Investigators. Kidney Int. 1997;51:244–252. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marcantoni C, Ma LJ, Federspiel C, Fogo AB. Hypertensive nephrosclerosis in African Americans versus Caucasians. Kidney Int. 2002;62:172–180. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kovesdy CP, Anderson JE, Derose SF, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Outcomes associated with race in males with nondialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:973–978. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06031108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freedman BI, Volkova NV, Satko SG, Krisher J, Jurkovitz C, Soucie JM, McClellan WM. Population-based screening for family history of end-stage renal disease among incident dialysis patients. Am J Nephrol. 2005;25:529–535. doi: 10.1159/000088491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lei HH, Perneger TV, Klag MJ, Whelton PK, Coresh J. Familial aggregation of renal disease in a population-based case-control study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:1270–1276. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V971270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song EY, McClellan WM, McClellan A, Rajyalakshmi G, Hadley AC, Krisher J, Clay M, Freedman BI. Effect of community characteristics on familial clustering of end-stage renal disease. Am J Nephrol. 2009;30:499–504. doi: 10.1159/000243716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tell GS, Hylander B, Craven TE, Burkart J. Racial differences in the incidence of end-stage renal disease. Ethn Health. 1996;1:21–31. doi: 10.1080/13557858.1996.9961767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brancati FL, Whittle JC, Whelton PK, Seidler AJ, Klag MJ. The excess incidence of diabetic end-stage renal disease among blacks. A population-based study of potential explanatory factors. JAMA. 1992;268:3079–3084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiberd BA, Clase CM. Cumulative risk for developing end-stage renal disease in the US population. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1635–1644. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000014251.87778.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kopp JB, Winkler C. HIV-associated nephropathy in African Americans. Kidney Int Suppl. 2003:S43–S49. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.63.s83.10.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eggers PW, Kimmel PL. Is there an epidemic of HIV Infection in the US ESRD program? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:2477–2485. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000138546.53152.A7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitiyakara C, Eggers P, Kopp JB. Twenty-one-year trend in ESRD due to focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44:815–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kitiyakara C, Kopp JB, Eggers P. Trends in the epidemiology of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Semin Nephrol. 2003;23:172–182. doi: 10.1053/snep.2003.50025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kopp JB, Smith MW, Nelson GW, Johnson RC, Freedman BI, Bowden DW, Oleksyk T, McKenzie LM, Kajiyama H, Ahuja TS, Berns JS, Briggs W, Cho ME, Dart RA, Kimmel PL, Korbet SM, Michel DM, Mokrzycki MH, Schelling JR, Simon E, Trachtman H, Vlahov D, Winkler CA. MYH9 is a major-effect risk gene for focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1175–1184. doi: 10.1038/ng.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freedman BI, Sedor JR. Hypertension-associated kidney disease: perhaps no more. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:2047–2051. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008060621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kao WH, Klag MJ, Meoni LA, Reich D, Berthier-Schaad Y, Li M, Coresh J, Patterson N, Tandon A, Powe NR, Fink NE, Sadler JH, Weir MR, Abboud HE, Adler SG, Divers J, Iyengar SK, Freedman BI, Kimmel PL, Knowler WC, Kohn OF, Kramp K, Leehey DJ, Nicholas SB, Pahl MV, Schelling JR, Sedor JR, Thornley-Brown D, Winkler CA, Smith MW, Parekh RS. MYH9 is associated with nondiabetic end-stage renal disease in African Americans. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1185–1192. doi: 10.1038/ng.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freedman BI, Hicks PJ, Bostrom MA, Cunningham ME, Liu Y, Divers J, Kopp JB, Winkler CA, Nelson GW, Langefeld CD, Bowden DW. Polymorphisms in the non-muscle myosin heavy chain 9 gene (MYH9) are strongly associated with end-stage renal disease historically attributed to hypertension in African Americans. Kidney Int. 2009;75:736–745. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freedman BI, Hicks PJ, Bostrom MA, Comeau ME, Divers J, Bleyer AJ, Kopp JB, Winkler CA, Nelson GW, Langefeld CD, Bowden DW. Non-muscle myosin heavy chain 9 gene MYH9 associations in African Americans with clinically diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus-associated ESRD. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009 doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freedman BI, Kopp JB, Winkler CA, Nelson GW, Rao DC, Eckfeldt JH, Leppert MF, Hicks PJ, Divers J, Langefeld CD, Hunt SC. Polymorphisms in the nonmuscle myosin heavy chain 9 gene (MYH9) are associated with albuminuria in hypertensive African Americans: the HyperGEN study. Am J Nephrol. 2009;29:626–632. doi: 10.1159/000194791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rao DC, Province MA, Leppert MF, Oberman A, Heiss G, Ellison RC, Arnett DK, Eckfeldt JH, Schwander K, Mockrin SC, Hunt SC. A genome-wide affected sibpair linkage analysis of hypertension: the HyperGEN network. Am J Hypertens. 2003;16:148–150. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(02)03247-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lipkowitz MS, Iyengar S, Molineros J, Langefeld CD, Comeau ME, Klotman PE, Bowden DW, Freeman RG, Khitrov G, Zhang W, Kao WHL, Parekh RS, Choi M, Kopp JB, Winkler CA, Nelson G, Freedman BI, Bottinger EP the AASK Investigators. Association analysis of the non-muscle myosin heavy chain 9 gene (MYH9) in hypertensive nephropathy: African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK) [Abstract] J Am Soc Nephol. 2009;20:56A. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pattaro C, Aulchenko YS, Isaacs A, Vitart V, Hayward C, Franklin CS, Polasek O, Kolcic I, Biloglav Z, Campbell S, Hastie N, Lauc G, Meitinger T, Oostra BA, Gyllensten U, Wilson JF, Pichler I, Hicks AA, Campbell H, Wright AF, Rudan I, van Duijn CM, Riegler P, Marroni F, Pramstaller PP. Genome-wide linkage analysis of serum creatinine in three isolated European populations. Kidney Int. 2009;76:297–306. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salem RM, Cadman PE, Chen Y, Rao F, Wen G, Hamilton BA, Rana BK, Smith DW, Stridsberg M, Ward HJ, Mahata M, Mahata SK, Bowden DW, Hicks PJ, Freedman BI, Schork NJ, O’Connor DT. Chromogranin A polymorphisms are associated with hypertensive renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:600–614. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007070754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen Y, Mahata M, Rao F, Khandrika S, Courel M, Fung MM, Zhang K, Stridsberg M, Ziegler MG, Hamilton BA, Lipkowitz MS, Taupenot L, Nievergelt C, Mahata SK, O’Connor DT. Chromogranin A regulates renal function by triggering Weibel-Palade body exocytosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1623–1632. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008111148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.d’Apolito M, Guarnieri V, Boncristiano M, Zelante L, Savoia A. Cloning of the murine non-muscle myosin heavy chain IIA gene ortholog of human MYH9 responsible for May-Hegglin, Sebastian, Fechtner, and Epstein syndromes. Gene. 2002;286:215–222. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00455-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sellers JR. Myosins: a diverse superfamily. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1496:3–22. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(00)00005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marini M, Bruschi M, Pecci A, Romagnoli R, Musante L, Candiano G, Ghiggeri GM, Balduini C, Seri M, Ravazzolo R. Non-muscle myosin heavy chain IIA and IIB interact and co-localize in living cells: relevance for MYH9-related disease. Int J Mol Med. 2006;17:729–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dong F, Li S, Pujol-Moix N, Luban NL, Shin SW, Seo JH, Ruiz-Saez A, Demeter J, Langdon S, Kelley MJ. Genotype-phenotype correlation in MYH9-related thrombocytopenia. Br J Haematol. 2005;130:620–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arrondel C, Vodovar N, Knebelmann B, Grunfeld JP, Gubler MC, Antignac C, Heidet L. Expression of the nonmuscle myosin heavy chain IIA in the human kidney and screening for MYH9 mutations in Epstein and Fechtner syndromes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:65–74. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V13165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berg JS, Powell BC, Cheney RE. A millennial myosin census. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:780–794. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.4.780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Even-Ram S, Doyle AD, Conti MA, Matsumoto K, Adelstein RS, Yamada KM. Myosin IIA regulates cell motility and actomyosin-microtubule crosstalk. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:299–309. doi: 10.1038/ncb1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seri M, Pecci A, Di BF, Cusano R, Savino M, Panza E, Nigro A, Noris P, Gangarossa S, Rocca B, Gresele P, Bizzaro N, Malatesta P, Koivisto PA, Longo I, Musso R, Pecoraro C, Iolascon A, Magrini U, Rodriguez SJ, Renieri A, Ghiggeri GM, Ravazzolo R, Balduini CL, Savoia A. MYH9-related disease: May-Hegglin anomaly, Sebastian syndrome, Fechtner syndrome, and Epstein syndrome are not distinct entities but represent a variable expression of a single illness. Medicine (Baltimore) 2003;82:203–215. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000076006.64510.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moxey-Mims MM, Young G, Silverman A, Selby DM, White JG, Kher KK. End-stage renal disease in two pediatric patients with Fechtner syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 1999;13:782–786. doi: 10.1007/s004670050700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oh J, Reiser J, Mundel P. Dynamic (re)organization of the podocyte actin cytoskeleton in the nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2004;19:130–137. doi: 10.1007/s00467-003-1367-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Faul C, Asanuma K, Yanagida-Asanuma E, Kim K, Mundel P. Actin up: regulation of podocyte structure and function by components of the actin cytoskeleton. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:428–437. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaplan JM, Kim SH, North KN, Rennke H, Correia LA, Tong HQ, Mathis BJ, Rodriguez-Perez JC, Allen PG, Beggs AH, Pollak MR. Mutations in ACTN4, encoding alpha-actinin-4, cause familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Genet. 2000;24(3):251–256. doi: 10.1038/73456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim JM, Wu H, Green G, Winkler CA, Kopp JB, Miner JH, Unanue ER, Shaw AS. CD2-associated protein haploinsufficiency is linked to glomerular disease susceptibility. Science. 2003;300(5623):1298–1300. doi: 10.1126/science.1081068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Asanuma K, Yanagida-Asanuma E, Faul C, Tomino Y, Kim K, Mundel P. Synaptopodin orchestrates actin organization and cell motility via regulation of RhoA signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:485–491. doi: 10.1038/ncb1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pavenstadt H, Kriz W, Kretzler M. Cell biology of the glomerular podocyte. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:253–307. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00020.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Freedman BI, Edberg JC, Kopp JB, Winkler CA, Nelson GW, Alarcon GS, Brown EE, McGwin G, Divers J, Cunningham ME, Langefeld CD, Kimberly RP. Association analysis of the non-muscle myosin heavy chain 9 (MYH9) gene in African Americans with lupus nephritis (LN) [Abstract] J Am Soc Nephol. 2008;19:134A. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shewan AM, Maddugoda M, Kraemer A, Stehbens SJ, Verma S, Kovacs EM, Yap AS. Myosin 2 is a key Rho kinase target necessary for the local concentration of E-cadherin at cell-cell contacts. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:4531–4542. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-04-0330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Choi J, Park SY, Joo CK. Transforming growth factor-beta1 represses E-cadherin production via slug expression in lens epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:2708–2718. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bariety J, Hill GS, Mandet C, Irinopoulou T, Jacquot C, Meyrier A, Bruneval P. Glomerular epithelial-mesenchymal transdifferentiation in pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:1777–1784. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Usui J, Kanemoto K, Tomari S, Shu Y, Yoh K, Mase K, Hirayama A, Hirayama K, Yamagata K, Nagase S, Kobayashi M, Nitta K, Horita S, Koyama A, Nagata M. Glomerular crescents predominantly express cadherin-catenin complex in pauci-immune-type crescentic glomerulonephritis. Histopathology. 2003;43:173–179. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2003.01660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klahr S, Schreiner G, Ichikawa I. The progression of renal disease. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:1657–1666. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198806233182505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Purkerson ML, Hoffsten PE, Klahr S. Pathogenesis of the glomerulopathy associated with renal infarction in rats. Kidney Int. 1976;9:407–417. doi: 10.1038/ki.1976.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Olson JL, Heptinstall RH. Nonimmunologic mechanisms of glomerular injury. Lab Invest. 1988;59:564–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Althaus K, Greinacher A. MYH9-related platelet disorders. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2009;35:189–203. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1220327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stouffer GA, Owens GK. TGF-beta promotes proliferation of cultured SMC via both PDGF-AA-dependent and PDGF-AA-independent mechanisms. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:2048–2055. doi: 10.1172/JCI117199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Border WA, Okuda S, Languino LR, Sporn MB, Ruoslahti E. Suppression of experimental glomerulonephritis by antiserum against transforming growth factor beta 1. Nature. 1990;346:371–374. doi: 10.1038/346371a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reeves-Daniel AM, Iskandar SS, Bowden DW, Bostrom MA, Hicks PJ, Comeau ME, Langefeld CD, Freedman BI. Collapsing C1q nephropathy: another MYH9-associated kidney disease? Am J Kidney Dis. 2009 doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.10.060. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Klahr S, Levey AS, Beck GJ, Caggiula AW, Hunsicker L, Kusek JW, Striker G. The effects of dietary protein restriction and blood-pressure control on the progression of chronic renal disease. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(13):877–884. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403313301301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stokes J, III, Kannel WB, Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, Cupples LA. Blood pressure as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. The Framingham Study--30 years of follow-up. Hypertension. 1989;13:I13–I18. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.13.5_suppl.i13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.MacMahon S, Cutler JA, Stamler J. Antihypertensive drug treatment. Potential, expected, and observed effects on stroke and on coronary heart disease. Hypertension. 1989;13:I45–I50. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.13.5_suppl.i45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Henderson JM, Alexander MP, Pollak MR. Patients with ACTN4 mutations demonstrate distinctive features of glomerular injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:961–968. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008060613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]