SUMMARY

Objective

To assess the association of emphysema and airway disease assessed by volumetric computed tomography (CT) with exercise capacity in subjects with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Methods

We studied 93 subjects with COPD (Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 s [FEV1] %predicted mean ± SD 57.1 ± 24.3%, female gender = 40) enrolled in the Lung Tissue Research Consortium. Emphysema was defined as percentage of low attenuation areas less than a threshold of −950 Hounsfield units (%LAA-950) on CT scan. The wall area percentage (WA%) of the 3rd to 6th generations of the apical bronchus of right upper lobe (RB1) were analyzed. The six-minute walk distance (6MWD) test was used as a measure of exercise capacity.

Results

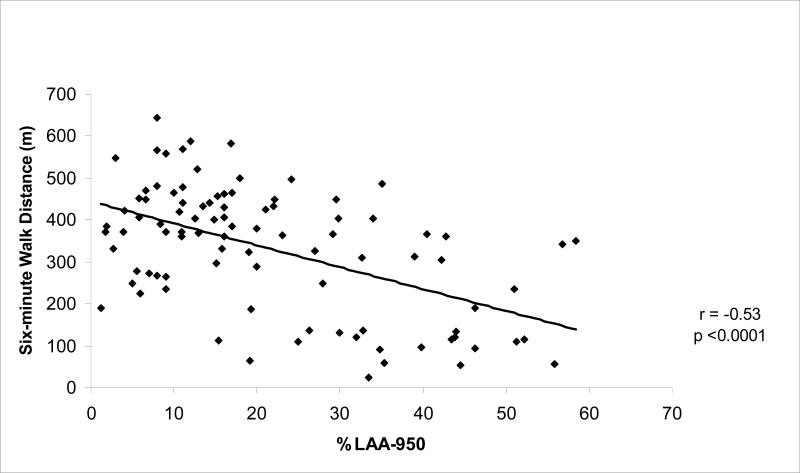

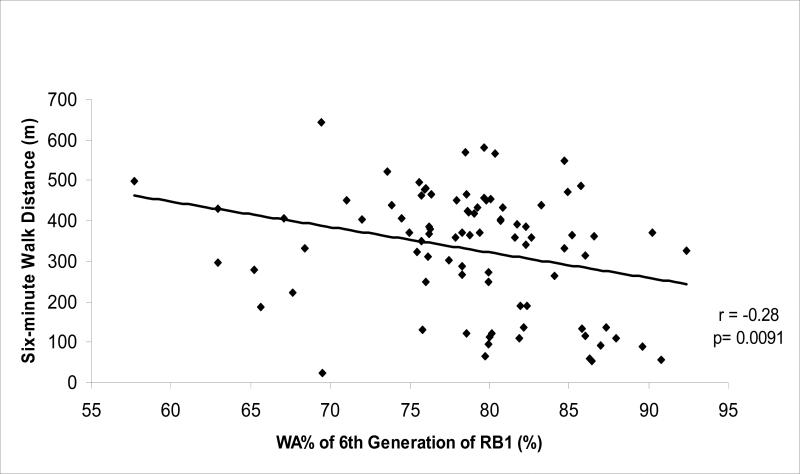

The 6MWD was inversely associated with %LAA-950 (r = −0.53, p<0.0001) and with the WA% of 6th generation of RB1 only (r = −0.28, p = 0.009). In a multivariate regression model including CT indices of emphysema and airway disease that were adjusted for demographic and physiologic variables as well as brand of CT scanner, only the %LAA-950 remained significantly associated with exercise performance. Holding other covariates fixed, this model showed that a 10% increase of CT emphysema reduced the distance walked in six minutes 28.6 meters (95% Confidence Interval = −51.2, −6.0, p = 0.01).

Conclusion

These results suggest that the extent of emphysema but not airway disease measured by volumetric CT contributes independently to exercise limitation in subjects with COPD.

Keywords: COPD, CT, emphysema, airways, 6-minute walk test

INTRODUCTION

A reduction in exercise capacity is frequent in subjects with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)1 and is traditionally associated with impaired lung function2-6. There is, however, increasing recognition that spirometric measures of lung function alone do not explain all the variance found in clinical measures of disease. As detailed by Reilly in his editorial to the UPLIFT study, COPD appears to be an aggregate of several unique subtypes7. Given this heterogeneous population, new measures of disease such as computed tomography assessment (CT) of emphysema and airway disease are of great interest in helping to understand disease pathophysiology and standard clinical measures such as exercise capacity.

The six-minute walk distance test (6MWD) is a commonly used measure of exercise capacity in subjects with COPD. It requires minimal equipment to perform and is widely available8. While computed tomography (CT) is increasingly used to quantitatively assess both the emphysema and airway disease in COPD9-18, studies of their contribution to exercise capacity are more limited19-21. Gould et al20 and Lee et al21 reported an association between emphysema assessed by CT and exercise capacity assessed by walking tests, but the relation of airway disease to exercise capacity, however, has not been demonstrated.

Based on prior studies revealing the inverse correlation between CT airway disease and lung function12, 14, we hypothesize that CT measures of airway disease would provide complimentary information to CT measures of emphysema in predicting exercise capacity measured by 6MWD independent of lung function. We undertook this study using data from Lung Tissue Research Consortium (LTRC), a National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute initiative to characterize subjects with chronic pulmonary diseases such as COPD.

METHODS

Subjects Selection

The data used in this study were collected as part of the LTRC and included measures of lung function, exercise testing, and volumetric CT scanning of the chest performed prior to lung volume reduction surgery, transplantation, and resection for suspected malignancy (www.ltrcpublic.com). Subjects were evaluated for inclusion in our study if they had a diagnosis of COPD (postbronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 s to forced expiratory vital capacity ratio [FEV1/FVC] <0.7) and a high resolution volumetric CT scan available for quantitative analysis. Five out of the 99 patients that met the two above criteria were eliminated because of a history of chronic heart failure which has been demonstrated to influence exercise performance 22. A sixth subject was excluded because of a giant bulla in the right lung which resulted in mediastinal displacement. The final study cohort consisted of 93 subjects and informed consent was obtained from each participant. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH).

Physiologic assessment

All subjects underwent standardized spirometric measures of lung function according to American Thoracic Society (ATS) guidelines 23. The postbronchodilator FEV1 and FVC were recorded in liters and expressed as percentages of predictive values (FEV1%P and FVC%P) using standardized prediction equations 24. Lung volume measurements were performed by body plethysmography. The residual volume, total lung capacity, and the residual volume to total lung capacity ratio were expressed as percentages of predicted values (RV%P, TLC%P and RV/TLC%P, respectively)25. The 6MWD was performed in a standardized manner following ATS recommendations26 . This test was typically performed once prior to a subject undergoing surgery. In four patients more than one walk test was taken while they were awaiting transplantation. In these cases, the walk test in closest proximity to the surgery was evaluated. Oxygen saturation (SO2) was measured before and at the end of the walk test. Oxygen supplementation was titrated to achieve a resting SO2 level of at least 88% prior to starting the test. The walking distance was recorded in meters.

Imaging Assessment

The radiology core laboratory defined CT protocols for LTRC 27. CT scanners follow the American College of Radiology guidelines for accreditation (www.acr.org/accreditation/computed/). Computed tomographic images were acquired in the supine position at full inflation using both General Electric (GE) and Siemens scanners. GE Protocol: 55 subjects underwent CT scanning using a GE CT scanner. Images were acquired using a 30cm field of view (FOV) in a GE LightSpeed 16 multislice scanner using a tube voltage of 140 kVp, a tube current of 300 or 375 mA for most subjects (n=48) and variable doses for the remaining subjects. Images were reconstructed using the bone algorithm at 1.25mm slice thickness and 0.625mm interval. Siemens Protocol: 38 subjects underwent CT scanning by using Siemens Sensation 10 or 64 multislice scanners. Images were similarly acquired using a 30cm FOV at 140 kVp with an automated dose modulation. Images were reconstructed using the b46f algorithm at 1mm slice thickness and 0.5mm interval.

Emphysema and airway analysis

Quantitative measures of emphysema for the whole lung and for airway disease were calculated using open-source software (www.airwayinspector.org). Emphysema was defined as low attenuation areas using a Hounsfield Unit (HU) threshold of −950 (%LAA-950) 10. Single-slice airway measurements were collected in the apical bronchus of the right upper lobe (RB1). RB1 was chosen because its long axis is generally perpendicular to axial imaging plane and prior studies have shown measures taken at this site correlate with lung function and predict small airway dimensions assessed by histological means12,13. Analysis was performed in the 3rd (segmental bronchus), 4th, 5th, and 6th generation. In each generation, one measurement was taken at what was judged to be the central portion of the segment of interest in an image reformatted orthogonally to the long axis of the lumen airway. The Phase Congruency method 28, 29 for airway segmentation was used to define the lumen-wall and wall-parenchymal boundaries and total airway area (Ao), airway lumen (Ai), and wall area percentage (WA%) defined as (Ao-Ai)/Ao × 100% were measured at each point of interest 30.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics are expressed as mean and SD or median and interquantile range when appropriate. Pearson's correlation coefficients were used to assess univariate relationships between CT-based measures of airway disease and emphysema, lung function, and 6MWD. Multivariate linear regression models were created using 6MWD as the response variable and %LAA-950 and WA% of 6th generation of RB1 together as explanatory variables. WA% of 6th generation was chosen because it correlated significantly with 6MWD in univariate analysis. Adjustment was done for the following known factors that influence a subject's exercise capacity: age, gender, body mass index (BMI)31, 32, and RV/TLC%P. RV/TLC ratio is an estimate of hyperinflation that has been shown that influences subject's exercise performance3. Model adjustment was also done for scanner brand and cancer status (presence or absence of malignancy on surgical pathology). The analysis was performed with SAS version 9.1 (Cary, NC). A P value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of the study subjects. The mean FEV1 was 1.6 ±0.7 L (range: 0.5-3.3 L). Fifteen out of 93 (16%) subjects used supplemental oxygen for the walk test. These 15 subjects had significant lower FEV1%P (mean ± SD 37.1 ±24.7% vs 60.1 ±22.2%), higher RV/TLC%P (209.2 ±80.7% vs 151.1 ±49.1%), shorter distance walked (193.2 ±106.1m vs 357.7 ±142.1m), and higher %LAA-950 (median 42.2 [interquantile range 25-51%]) than the 78 non-oxygen users. Fifty eight of the 93 subjects received a diagnosis of cancer. Data by cancer status is shown in table 2.

Table 1.

Anthropometric, lung function, exercise capacity, CT assessment, and procedure data for the 93 subjects

| Variable** | Mean ± (SD)* |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 66.7 ± 8.8 |

| Female Gender (n, %) | 40 (43) |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 26.2 ± 4.7 |

| Smoking History (pack years) | 54.2 ± 31.7 |

| FEV1 (%predicted) | 57.1 ± 24.3 |

| FVC (%predicted) | 81.6 ± 19.3 |

| FEV1/FVC ratio | 0.5 ± 0.2 |

| RV (%predicted) | 159.4 ± 57.9 |

| TLC (%predicted) | 111.9 ± 18.9 |

| RV/TLC ratio (%predicted) | 131.6 ± 32.3 |

| PaO2 (mm Hg) | 80.3 ± 31.8 |

| PaCO2 (mm Hg) | 39.9 ± 6.5 |

| Six-Minute Walk Distance (m) | 331.2 ± 149.4 |

| SpO2 at the end of 6MWD (%) | 91.7 ± 6.5 |

| %LAA-950 (%) | 16. 8 (9.0-32.6) |

| WA% of 3rd generation of RB1 (%) | 60.5 ± 6.2 |

| WA% of 4th generation of RB1 (%) | 66.4± 7.7 |

| WA% of 5th generation of RB1 (%) | 72. 3 ± 7.5 |

| WA% of 6th generation of RB1 (%) | 78.8 ± 6.5 |

| Type of procedure (n, %) | |

| Wedge resection or Lobectomy | 57 (61) |

| Lung Volume Reduction Surgery | 11 (12) |

| Lung Transplant | 10 (11) |

| Surgical Lung Biopsy | 5 (5) |

| No Tissue Obtained | 10 (11) |

Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, except for female gender and type of procedure n (%), and %LAA-950 median (interquantile range).

Missing values: smoking history 4 subjects; volume and total lung capacity 4 subjects; wall area percent of 3rd to 6th generation airways 5, 4, 4, and 6 subjects, respectively. PaO2, Partial Pressure of Oxygen in Arterial Blood; PaCO2, Partial Pressure of Carbon Dioxide in Arterial Blood; SpO2, Oxygen Saturation Measured by Pulse Oximetry at the immediate termination of the 6MWD, %LAA-950, Percentage of Low Attenuation Areas Below -950 Hounsfield Units; WA%, Wall Area Percentage; RB1, Apical Bronchus of the Right Upper Lobe.

Table 2.

Anthropometric, lung function, exercise capacity, and CT assessment data for the 93 subjects by cancer status

| Variable | Subjects with cancer (n=58) Mean ± SD* | Subjects without cancer (n=35) Mean ± SD* |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 69.8 ± 6.8 | 61.5 ± 9.4** |

| Female Gender (n, %) | 26 (44.8) | 14 (40.0) |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 26.0 ± 4.6 | 26.5 ± 4.9 |

| Smoking History (pack years ) | 55.5 ± 34.6 | 52.1 ± 26.5 |

| FEV1 (% predicted) | 68.5 ±18.2 | 36.3 ± 18.6** |

| FVC (% predicted) | 88.4 ±16.4 | 70.3 ± 18.6** |

| FEV1/FVC ratio | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.2** |

| RV (%predicted) | 137.0 ± 37.7 | 195.3 ± 67.9** |

| TLC (%predicted) | 107.9 ± 15.9 | 118.5 ± 21.6** |

| RV/TLC ratio (%predicted) | 119.4 ± 23.2 | 152.0 ± 35.2** |

| Six-Minute Walk Distance (m) | 402.7 ± 102.5 | 212.6 ± 139.8** |

| %LAA-950 % | 12.9 (8.0-19.2) | 34.8 (25-44.5)** |

| WA% of 3rd generation of RB1 (%) | 61.1 ± 6.0 | 59.7 ± 6.6 |

| WA% of 4th generation of RB1 (%) | 65.5 ± 7.1 | 67.9 ± 8.4 |

| WA% of 5th generation of RB1 (%) | 71.8 ± 6.9 | 73.1 ± 8.5 |

| WA% of 6th generation of RB1 (%) | 77.1 ± 6.5 | 81.6 ± 5.7** |

Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, except for female gender n (%) and %LAA-950 median (interquantile range).

P value <0.05.

%LAA-950, Percentage of Low Attenuation Areas Below -950 Hounsfield; WA%, Wall Area Percentage; RB1, Apical Bronchus of the Right Upper Lobe.

Association between CT emphysema, WA%, lung function, and exercise capacity

CT indices of both emphysema and airway disease were inversely associated with exercise capacity. Subjects with higher CT emphysema (r= −0.53, p<0.0001, Figure 1) or WA% of the 6th generation of RB1 (r= −0.28, p=0.009, Figure 2) walked significantly less in 6 minutes. There was not a significant correlation between 6-MWD and WA% of the 3rd to the 5th generation airways (Table 3). Subjects with higher CT emphysema had lower BMI (r= −0.25, p=0.015) and FEV1%P (r= −0.68, p<0.0001), and higher degree of hyperinflation estimated by RV/TLC%P (r= 0.56, p<0.0001). Subjects with greater WA% of the 4th (r= −0.23, p=0.03), 5th (r= −0.22, p=0.04), and 6th generation (r= −0.39, p=0.0002) of RB1 also had lower FEV1%P.

Figure 1.

Scatter plot of six-minute walk distance to emphysema assessed by CT defined as percentage of low attenuation areas below −950 Hounsfield units (%LAA-950) in subjects with COPD

Figure 2.

Scatter plot of six-minute walk distance to wall area percentage (WA%) of the 6th generation of the apical bronchus of the right upper lobe (RB1) assessed by CT in subjects with COPD.

Table 3.

Pearson's correlation coefficients (r) between 6-minute walk distance, lung function, emphysema and airway disease assessed by CT for the 93 subjects

| Variable | Six-minute walk distance (m) | |

|---|---|---|

| r Value | P Value | |

| FEV1 (%predicted) | 0.48 | <0.0001 |

| FVC (%predicted) | 0.32 | 0.002 |

| FEV/FVC ratio | 0.47 | <0.0001 |

| RV (%predicted) | -0.40 | <0.0001 |

| TLC (%predicted) | -0.22 | 0.04 |

| RV/TLC ratio (%predicted) | -0.39 | 0.0002 |

| %LAA-950 (%) | -0.53 | <0.0001 |

| WA% of 3rd generation of RB1 (%) | 0.12 | 0.35 |

| WA% of 4th generation of RB1 (%) | -0.18 | 0.09 |

| WA% of 5th generation of RB1 (%) | -0.10 | 0.37 |

| WA% of 6th generation of RB1 (%) | -0.28 | 0.009 |

%LAA-950, Percentage of Low Attenuation Areas Below -950 Hounsfield; WA%, Wall Area Percentage; RB1, Apical Bronchus of the Right Upper Lobe.

CT emphysema but not airway disease remained significantly associated with exercise capacity in the multivariate analysis adjusted for age, gender, BMI, RV/TLC%P, scanner brand, and cancer status (Table 4). Holding other covariates fixed, the adjusted effect estimate of %LAA-950 on exercise capacity shows that a 10% increase of emphysema on CT scan decreases the 6-minute walking distance 28.6 meters (95% Confidence Interval −51.2, −6.0, p = 0.014). The unadjusted model for predicting 6MWD containing LAA%-950 and WA% explained more variability in the 6MWD (R2= 0.29) than a single-variable model containing lung volume measures as predictors (for RV/TLC%P, R2= 0.15; for RV%P, R2= 0.13; and for TLC%P, R2= 0.05).

Table 4.

Multivariate linear regression models for the association between six-minute walk distance (m) and CT indices.

| CT indices | Unadjusted | Adjusted* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter Estimate (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value | Parameter Estimate (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value | |

| %LAA-950 (%) | -4.76 (-6.71, -2.81) | <0.0001 | -2.86 (-5.12, -0.60) | 0.014 |

| WA% of 6th generation of RB1 (%) | -2.49 (-6.94, 1.94) | 0.27 | -1.18 (-5.39, 3.02) | 0.57 |

The model was adjusted for age, gender (female=1), BMI, RVTLC%P, scanner brand (GE scanner =1) and cancer status. R2 values for unadjusted and adjusted models were 0.29 and 0.54, respectively.

%LAA-950, Percentage of Low Attenuation Areas Below -950 Hounsfield; WA%, Wall Area Percentage; RB1, Apical Bronchus of the Right Upper Lobe.

DISCUSSION

In this study we observed that in univariate analysis whole lung emphysema percentage assessed by volumetric CT and airway wall thickening of only the 6th generation airway of right upper lobe apical segment correlated with the distance walked in six minutes in subjects with COPD. Multivariate analysis showed that in this cohort emphysema but not airway disease contributed independently to exercise capacity as assessed by 6MWD.

The %LAA-950 is inversely associated with 6MWD suggesting that emphysema has a deleterious impact on exercise capacity. Previous studies examining the relationship between objective and semi-objective measures of emphysema and exercise capacity have yielded conflicting results. An early study found that CT emphysema correlated with 12-minute walk distance 20 and Lee et al 21 found that %LAA-950 obtained from volumetric CT scans is inversely correlated with 6MWD (r= −0.53). In contrast to these, Taguchi et al 33 found that using a subjective visual assessment of emphysema in 32 subjects with COPD there was no relationship between their measures of emphysema and 6MWD. Technique differences and their smaller sample size may explain the disparity with our results. In another recent study, Mair et al 34 did not find a correlation between %LAA-950 and 6MWD. A lower median (5.5%) and a narrower interquantile range of CT emphysema percentage (1.6-17.5%) of their subjects may partly explain the disparity with the present result.

Airway wall thickening of the most distal airway assessed in this study was inversely related to 6MWD in univariate analysis. A previous cited study failed to find such a relation 21. One reason for this discrepancy is that in the Lee study only segmental bronchi were assessed. Our finding suggests that airway wall thickening of a more distal airway assessed by CT scanning is associated with changes in 6MWD. A partial explanation for the relationship between WA% and 6MWD is that the airway wall thickening in COPD leads to an increased airflow resistance, which reduces ventilatory capacity and contributes to an increased sense of effort in breathing during exercise 22. In COPD, the small airways (2 mm or less in diameter) are the site of major airflow resistance35 and it has been shown that WA% of the 3rd generation of RB1 measured by CT is a surrogate for the dimensions of those small airways measured by histological means13. When the airway thickening was included with CT emphysema in an adjusted multivariate model, however, only emphysema remained associated with 6MWD. Thus, our CT assessment of COPD suggests that emphysematous destruction of the lung more than airway remodeling of the disease may be responsible for the effect on the reduction of 6MWD. There may be several reasons for this observed association.

First, elastic recoil loss of emphysema with subsequent airway collapse lead to airflow limitation and gas trapping could in turn lead to a reduction of the subject's exercise performance 22. Severe emphysema is also associated with changes in the configuration of the bony chest and diaphragm that lead to a mechanical disadvantage of the respiratory system. Butler 36 showed an inverse correlation between the area of the whole diaphragm and percentage of the whole lung occupied by emphysematous lesions. In addition, Lando et al 37 showed that a change in diaphragm length is correlated with better exercise performance after lung volume reduction surgery in patients with severe emphysema. Finally, Matsuoka et al recently showed an inverse association between the cross sectional area of small pulmonary vessels and emphysema38. It has been suggested that loss of pulmonary vasculature may lead to an increase in pulmonary vascular resistance and a decrease in pulmonary vascular compliance even in patients with mild emphysema39. The changes can cause an increased load on the right ventricle39 that may lead to decreased left heart filling40 and compromised oxygen delivery to muscles. Thus, these changes may also explain the decrease in exercise capacity seen in our subjects.

This study shows that objective analysis of volumetric CT scans may provide additional information to phenotype COPD. It can not only define the presence and extent of emphysema and airway thickening, but may also predict exercise impairment in subjects with COPD. This complementary information may be of utility for further understanding the relationship of lung structure and the clinical manifestations of disease.

There are several limitations of this study. While a wide range of lung function and a detailed physiologic and imaging assessment of the LTRC subjects are obvious strengths of this cohort, there is a subject selection bias inherent to the population enrolled in the LTRC as they were undergoing evaluation for surgical resection of potentially cancerous lesions apparent on preoperative CT images. Subjects with COPD and cancer had better lung function and exercise performance, less emphysema, and thinner 6th generation airway on CT scans than their counterparts without cancer. Furthermore, in multivariate analysis, the presence of cancer was a confounder in the association between CT measures of COPD and 6MWD because it remained as a significant predictor in the model and decreased significantly the effect estimate associated with emphysema. Thus, our study cohort does not likely represent the “general” population of smokers with COPD. Despite of this, the expected direction of the association between %LAA and 6MWD found in this study is supported by previous studies.20, 21

Second, the LTRC is a multicenter initiative employing different brands and generations of CT scanners. Despite efforts to standardize image acquisition and reconstruction, there were likely systematic differences in CT scans introducing bias in our results. However, present results on the correlations of %LAA-950 with FEV1%P and BMI and of 4th to 6th airway generations of RB1 with FEV1%P are consistent with previous studies12, 14, 17, 18, 20, 21, 30, 34, 41 and are supportive of our findings regarding the relation of CT indexes to 6MWD.

Finally, we assumed that WA% of 3rd to 6th generations of RB1 may represent the airway dimensions of the rest of the lungs. This may not be appropriate as it has been shown that there are variations in airway dimensions and in correlations between WA% and FEV1%P in the right upper and right lower lobes14. Further studies are needed to assess whether or not there is variability in correlations between WA% and exercise capacity through the lungs.

In summary, the present study suggests that airway wall thickening of a distal airway generation and emphysema assessed by CT correlates with six-minute walk distance in subjects with COPD, but only emphysema seems to contribute independently to exercise capacity. As this was a retrospective analysis and the population study may not be representative of the normal COPD population, further prospective studies involving large study cohort are needed to assess the observed relationship between CT indexes and exercise capacity.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health [Grants 5U10HL074428-3, K23HL089353-01A1], and an award from The Parker B. Francis Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rennard S, Decramer M, Calverley PM, et al. Impact of COPD in North America and Europe in 2000: subjects’ perspective of Confronting COPD International Survey. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:799–805. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.03242002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauerle O, Chrusch CA, Younes M. Mechanisms by which COPD affects exercise tolerance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:57–68. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.1.9609126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foglio K, Carone M, Pagani M, Bianchi L, Jones PW, Ambrosino N. Physiological and symptom determinants of exercise performance in patients with chronic airway obstruction. Respir Med. 2000;94:256–63. doi: 10.1053/rmed.1999.0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wijkstra PJ, TenVergert EM, van der Mark TW, et al. Relation of lung function, maximal inspiratory pressure, dyspnoea, and quality of life with exercise capacity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1994;49:468–72. doi: 10.1136/thx.49.5.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown CD, Benditt JO, Sciurba FC, et al. Exercise testing in severe emphysema: association with quality of life and lung function. COPD. 2008;5:117–24. doi: 10.1080/15412550801941265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Gascon M, Sanchez A, Gallego B, Celli BR. Inspiratory capacity, dynamic hyperinflation, breathlessness, and exercise performance during the 6-minute-walk test in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1395–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.6.2003172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reilly JJ. COPD and declining FEV1--time to divide and conquer? N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1616–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0807387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cote CG, Casanova C, Marin JM, et al. Validation and comparison of reference equations for the 6-min walk distance test. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:571–8. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00104507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muller NL, Staples CA, Miller RR, Abboud RT. “Density mask”. An objective method to quantitate emphysema using computed tomography. Chest. 1988;94:782–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.94.4.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gevenois PA, de Maertelaer V, De Vuyst P, Zanen J, Yernault JC. Comparison of computed density and macroscopic morphometry in pulmonary emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:653–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.2.7633722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kinsella M, Muller NL, Abboud RT, Morrison NJ, DyBuncio A. Quantitation of emphysema by computed tomography using a “density mask” program and correlation with pulmonary function tests. Chest. 1990;97:315–21. doi: 10.1378/chest.97.2.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakano Y, Muro S, Sakai H, et al. Computed tomographic measurements of airway dimensions and emphysema in smokers. Correlation with lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:1102–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.9907120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakano Y, Wong JC, de Jong PA, et al. The prediction of small airway dimensions using computed tomography. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:142–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200407-874OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasegawa M, Nasuhara Y, Onodera Y, et al. Airflow limitation and airway dimensions in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:1309–15. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200601-037OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orlandi I, Moroni C, Camiciottoli G, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: thin-section CT measurement of airway wall thickness and lung attenuation. Radiology. 2005;234:604–10. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2342040013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berger P, Perot V, Desbarats P, Tunon-de-Lara JM, Marthan R, Laurent F. Airway wall thickness in cigarette smokers: quantitative thin-section CT assessment. Radiology. 2005;235:1055–64. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2353040121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deveci F, Murat A, Turgut T, Altuntas E, Muz MH. Airway wall thickness in patients with COPD and healthy current smokers and healthy non-smokers: assessment with high resolution computed tomographic scanning. Respiration. 2004;71:602–10. doi: 10.1159/000081761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aziz ZA, Wells AU, Desai SR, et al. Functional impairment in emphysema: contribution of airway abnormalities and distribution of parenchymal disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:1509–15. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wakayama K, Kurihara N, Fujimoto S, Hata M, Takeda T. Relationship between exercise capacity and the severity of emphysema as determined by high resolution CT. Eur Respir J. 1993;6:1362–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gould GA, Redpath AT, Ryan M, et al. Lung CT density correlates with measurements of airflow limitation and the diffusing capacity. Eur Respir J. 1991;4:141–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee YK, Oh YM, Lee JH, et al. Quantitative assessment of emphysema, air trapping, and airway thickening on computed tomography. Lung. 2008;186:157–65. doi: 10.1007/s00408-008-9071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones NL, Killian KJ. Exercise limitation in health and disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:632–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008313430907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Thoracic Society Standardization of Spirometry, 1994 Update. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1107–36. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.3.7663792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crapo RO, Morris AH, Gardner RM. Reference spirometric values using techniques and equipment that meet ATS recommendations. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1981;123:659–64. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1981.123.6.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stocks J, Quanjer PH. Reference values for residual volume, functional residual capacity and total lung capacity. ATS Workshop on Lung Volume Measurements. Official Statement of The European Respiratory Society. Eur Respir J. 1995;8:492–506. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08030492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:111–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang J, Bruesewitz MR, Bartholmai BJ, McCollough CH. Selection of appropriate computed tomographic image reconstruction algorithms for a quantitative multicenter trial of diffuse lung disease. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2008;32:233–7. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e3180690d89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Estepar RS, Washko GG, Silverman EK, Reilly JJ, Kikinis R, Westin CF. Accurate airway wall estimation using phase congruency. Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv Int Conf. 2006;9:125–34. doi: 10.1007/11866763_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.San Jose Estepar R, Reilly JJ, Silverman EK, Washko GR. Three-dimensional airway measurements and algorithms. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:905–9. doi: 10.1513/pats.200809-104QC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coxson HO, Quiney B, Sin DD, et al. Airway wall thickness assessed using computed tomography and optical coherence tomography. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:1201–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200712-1776OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Enright PL, Sherrill DL. Reference equations for the six-minute walk in healthy adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:1384–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.5.9710086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wasserman K, Hansen J, Sue D, Whipp B, Casaburi R. Principles of Exercise Testing and Interpretation. Second ed. PA Lea & Febiger; Philadelphia: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taguchi O, Gabazza EC, Yoshida M, et al. CT scores of emphysema and oxygen desaturation during low-grade exercise in patients with emphysema. Acta Radiol. 2000;41:196–7. doi: 10.1080/028418500127345046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mair G, Miller JJ, McAllister D, et al. Computed tomographic emphysema distribution: relationship to clinical features in a cohort of smokers. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:536–42. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00111808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hogg JC, Timens W. The pathology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009;4:435–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Butler C. Diaphragmatic changes in emphysema. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1976;114:155–9. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1976.114.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lando Y, Boiselle PM, Shade D, et al. Effect of lung volume reduction surgery on diaphragm length in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:796–805. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.3.9804055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsuoka S, Washko GR, Dransfield MT, et al. Quantitative CT measurement of cross-sectional area of small pulmonary vessel in COPD: correlations with emphysema and airflow limitation. Acad Radiol. 2010;17:93–9. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2009.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vonk-Noordegraaf A. The shrinking heart in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:267–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0906251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barr RG, Bluemke DA, Ahmed FS, et al. Percent emphysema, airflow obstruction, and impaired left ventricular filling. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:217–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ogawa E, Nakano Y, Ohara T, et al. Body mass index in male patients with COPD: correlation with low attenuation areas on CT. Thorax. 2009;64:20–5. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.097543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]