Abstract

Background

Mutations in the KCNQ1 and HERG genes cause the Long QT Syndromes, LQTS1 and LQTS2, due to reductions in the cardiac repolarizing IKs and IKr currents, respectively. It was previously reported that KCNQ1 co-expression modulates HERG function by enhancing membrane expression of HERG, and that the two proteins co-immunoprecipitate, and co-localize in myocytes. In vivo studies in genetically modified rabbits also support a HERG-KCNQ1 interaction.

Objective

We sought to determine whether KCNQ1 influences the current characteristics of HERG genetic variants.

Methods

Expression of HERG and KCNQ1 wild type (WT) and mutant channels in heterologous systems, combined with whole cell patch clamp analysis and biochemistry.

Results

Supporting the notion that KCNQ1 needs to be trafficking competent to influence HERG function, we found that although the tail current density of HERG expressed in CHO cells was approximately doubled by WT KCNQ1 co-expression, it was not altered in the presence of the trafficking-defective KCNQ1T587M variant. Activation and deactivation kinetics of HERG variants were not altered. The HERGM124T variant, previously shown to be mildly impaired functionally, was restored to WT levels by KCNQ1-WT but not KCNQ1T587M co-expression. The tail current densities of the severely trafficking-impaired HERGG601S and HERGF805C variants were only slightly improved by KCNQ1 co-expression. The trafficking competent, but incompletely processed HERGN598Q, and a mutation in the selectivity filter, HERGG628S, were not improved by KCNQ1 co-expression.

Conclusions

These findings suggest a functional co-dependence of HERG on KCNQ1 during channel biogenesis. Moreover, KCNQ1 variably modulates LQTS2 mutations with distinct underlying pathologies.

Keywords: arrhythmia, Long QT Syndrome, potassium channel, genetic variants, electrophysiology, trafficking

Introduction

The delayed rectifier K+ current, IK, plays a critical role in action potential repolarization in cardiac myocytes and consists of two components, IKr and IKs.1 The HERG protein, encoded by the KCNH2 gene, constitutes the pore-forming subunit of IKr,2;3 whereas KCNQ1, and its β subunit KCNE1, form IKs.4;5 All three genes are targets for genetic mutations in LQTS. Mutations in KCNQ1 and HERG cause the congenital LQTS16 and LQTS2,7 respectively.

KCNQ1 co-expression with HERG in cultured cells results in increased IHERG density and HERG and KCNQ1 interact biochemically and co-localize in myocytes.8;9 Expression of dominant-negative KCNQ1 or HERG transgenes in genetically modified rabbits resulted in the downregulation of the remaining reciprocal current, indicating that the two proteins interact in vivo.10

We speculated that KCNQ1 enhances IHERG because of a codependency during biogenesis/trafficking and compared the effects of WT and the trafficking-deficient KCNQ1T587M variant11 on HERG genetic variants. Our findings indicate that there is a functional interdependence of LQTS2 and LQTS1 mutants, and that the impact of KCNQ1 will depend on the underlying patho-physiology of any given HERG variant, as well as on trafficking functions associated with KCNQ1.

Methods

Plasmids

The HERG cDNA was subcloned as described.12 Mutations were introduced into the HERG cDNA in the same vector backbone (pSI, Promega) using recombinant PCR and verified by sequencing. The triple FLAG-tagged KCNQ1 was as described.13 The KCNA5 cDNA was contained in pBKCMV. HA-HERG on vector pSI contains two HA epitopes fused in frame upstream of the HERG initiator ATG.

Electrophysiology

CHO-K1 cells were transfected with cDNA concentrations listed in the figure legends and sufficient GFP-Ire carrier DNA to bring the total DNA concentration to a constant amount using FuGENE 6 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN).

Cells exhibiting green fluorescence associated with KCNQ1-IRES-GFP or the GFP-Ire vector were chosen for whole cell patch clamp as described.14 Drug effects were recorded in cells following a pre-drug period where control data were obtained (during pulsing) and a 2 minute drug wash-in period throughout which the cell was held at −80 mV. For all drug applications, we used a small bath volume (~1 ml), and fully exchanged the external solution at least 4 times within a 2-minute time period.

Data were acquired, using pCLAMP software (v 8.2; Axon Instruments, Inc., Foster City, CA) as described.14 Pooled data were expressed as means and standard errors, and statistical comparisons were made (Origin, Microcal Software, Northampton, MA) with P<0.05 considered significant.

Immunoprecipitations and Western blotting

Whole cell protein extracts were prepared as described.14 700 μgs of each extract were immunoprecipitated with EZview Red Anti-FLAG M2 or anti-HA Affinity Gel (Sigma). Immunoprecipitates were washed three times with 1xTBS (0.9% NaCl, 20 mM Tris, pH 7.4), followed by resuspension in SDS sample buffer, and prepared for Western blotting with a rabbit anti-HERG antibody (1:400 dilution, Alomone), goat anti-KCNQ1 antibody (1:200 dilution, Santa Cruz), or anti-KCNA5 (1:400, Alomone) in combination with an HRP-linked anti-goat secondary antibody (1:5,000 Jackson ImmunoResearch) or anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:10,000 dilution, GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corp.) using ECL (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corp.).

Results

Coexpression of WT KCNQ1 increases IHERG without affecting gating

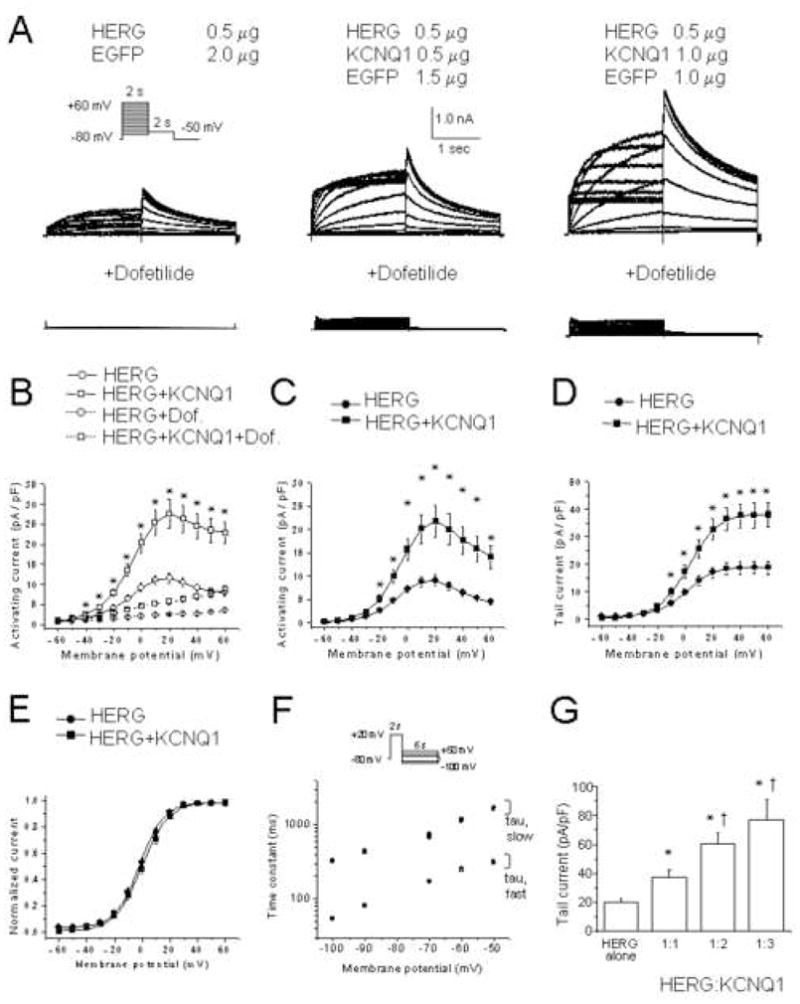

To assess the effects of KCNQ1 on HERG, we transfected CHO cells with both cDNAs. To separate KCNQ1 and HERG currents, we used the specific IKr blocker, dofetilide and subtracted the dofetilide insensitive component (IKCNQ1) from the composite current measured in the absence of drugs. Only the dofetilide-sensitive (IHERG) component was increased after KCNQ1 expression (Figure 1B–D). The current–voltage relationship of the activating current after subtracting the dofetilide insensitive component shows enhanced IHERG when KCNQ1 is present (Figure 1C, D). The mean amplitude (± SEM) of the tail currents at −50 mV after a depolarizing test pulse to + 40 mV was 37.5 ± 4.9 pA/pF (n=29) for HERG plus KCNQ1 at a cDNA ratio of 1:1, versus 19.4 ± 2.6 pA/pF (n=30) for HERG alone (P<0.05). With increasing amounts of KCNQ1 cDNA, we observed increasing IHERG, suggesting dose-dependency (Figure 1G): At a 1:2 ratio of HERG:KCNQ1 cDNAs, the mean amplitude of the tail currents was 60.1 ± 7.3 pA/pF (n=19, P<0.05 compared to the 1:1 ratio). At a 1:3 ratio, the mean amplitude was 77.3 ± 13.9 pA/pF (n=12, P=n.s. versus the 1:2 ratio).

Figure 1. KCNQ1 co-expression increases HERG current amplitude but does not affect voltage-dependence or kinetics.

(A) Representative current traces with and without 1 μM dofetilide. Amounts of cDNAs transfected are indicated. Inset, voltage protocol. (B) Current-voltage relationship measured at the end of the activating pulse for 0.5 μg HERG (n=29) and 0.5 μg HERG + 0.5 μg KCNQ1 (n=25). *, P≤ 0.05 by one-way ANOVA versus HERG alone. Current-voltage relationship of activating (C) and tail currents (D) for HERG (n=29) and HERG +KCNQ1 (n=25). (E) Mean amplitudes of normalized tail currents for HERG (n = 24) and HERG+KCNQ1 (n=25). (F) Deactivation time constants of HERG (n=23) and HERG+KCNQ1 (n=20). Current was activated by 2 s pulses to +20 mV, followed by a return to test potentials between −50 mV and −100 mV. (G) Summary data of the tail current density measured at −50 mV after a depolarizing test pulse to +20 mV of 0.5 μg HERG (n=30), 0.5 μg HERG + 0.5 μg KCNQ1 (n = 29), 0.5 μg HERG + 1.0 μg KCNQ1 (n = 19), and 0.5 μg HERG + 1.5 μg KCNQ1 (n = 12). *, P≤ 0.05 versus 0.5 μg HERG alone. †, P≤ 0.05 versus 0.5 μg HERG + 0.5 μg KCNQ1 (one-way ANOVA).

The amplitude of the tail currents observed with a 1:1 ratio was plotted as a function of the test potential and the curve was fitted to a Boltzmann function (Figure 1E). The V1/2 of activation was 1.7 ± 1.4 mV (n=22, slope factor 8.5 ± 0.2 mV) for HERG alone, which was comparable to 0.0 ± 1.4 mV (n=25, slope factor 9.2 ± 0.3 mV) for HERG plus KCNQ1.

IHERG fast and slow deactivation time constants were comparable for HERG alone and HERG plus KCNQ1 (Figure 1F). Since HERG kinetics are known to be influenced by temperature,15 we also assessed the effects of KCNQ1 co-expression on IHERG at 36° C, but found no change in activation, deactivation, and inactivation kinetics.

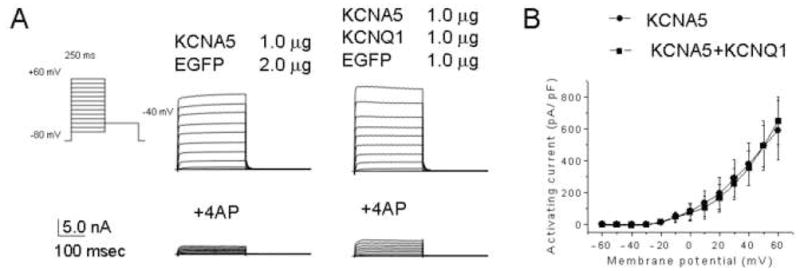

To determine whether the effects of KCNQ1 show specificity for HERG, we co-expressed KCNQ1 with KCNA5. We first demonstrated that IKCNQ1 was insensitive to concentrations of 4-AP known to inhibit IKCNA516 (Figure 2A). Following co-expression, we then subtracted the component of the current that is insensitive to 2 mM 4-AP (IKCNQ1) from the composite current, to derive values for IKCNA5 activating currents. As Figure 2B shows, IKCNA5 was not altered following KCNQ1 co-expression.

Figure 2. KCNQ1 co-expression does not influence KCNA5 current amplitude.

(A) Representative current traces from cells transfected with (bottom) and without (top) 2 mM 4-AP. Inset, voltage protocol. (B) Current-voltage relationship of KCNQ1 activating currents without (n = 6) and with 4-AP (n = 6), and those of KCNA5 (n = 7) and KCNA5 + KCNQ1 (n = 7) after subtracting the 4-AP insensitive component.

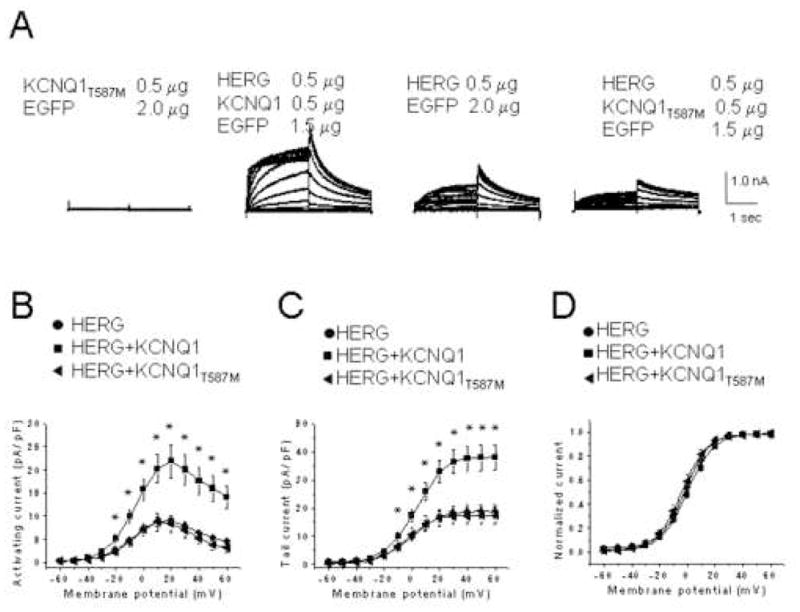

A trafficking defective LQTS1 mutant does not affect IHERG

Since KCNQ1 increases IHERG without influencing its kinetic properties, and because Ehrlich et al8 previously suggested that KCNQ1 improves HERG membrane localization, we assessed the effect of a trafficking defective KCNQ1 mutation (T587M17) on IHERG. No current was observed upon KCNQ1T587M expression alone, and KCNQ1T587M co-expression did not alter IHERG levels (Figure 3A-C). The mean amplitude of the tail currents measured at -50 mV after a depolarizing test pulse to +40 mV was 17.2 ± 2.9 pA/pF (n=11) for HERG plus KCNQ1T587M, significantly smaller than 37.5 ± 4.9 pA/pF (n=29) for HERG plus WT KCNQ1 (P<0.05) (Figure 3C). These results agree with observations made recently by Biliczki et al.9 The current-voltage relationship of normalized tail currents showed that both the V1/2 and slope factors were comparable (Figure 3D), indicating no effect on kinetic properties of IHERG.

Figure 3. The trafficking-deficient KCNQ1 T587M variant has no effect on HERG current amplitude.

(A) Representative currents recorded from CHO cells expressing KCNQ1T587M, HERG + KCNQ1, HERG, or HERG + KCNQ1T587M channels. Current-voltage relationships of activating (B) and tail currents (C) for HERG alone (n=9), HERG + KCNQ1 (n = 10), and HERG + KCNQ1T587M (n = 8), following subtraction of dofetilide insensitive currents. *, P ≤ 0.05 by one-way ANOVA versus HERG alone. (D) Mean amplitudes of normalized tail currents for HERG (n=9), HERG + KCNQ1 (n=10), and HERG + KCNQ1T587M (n=8).

HERG mutants are variably rescued by co-expression with WT KCNQ1

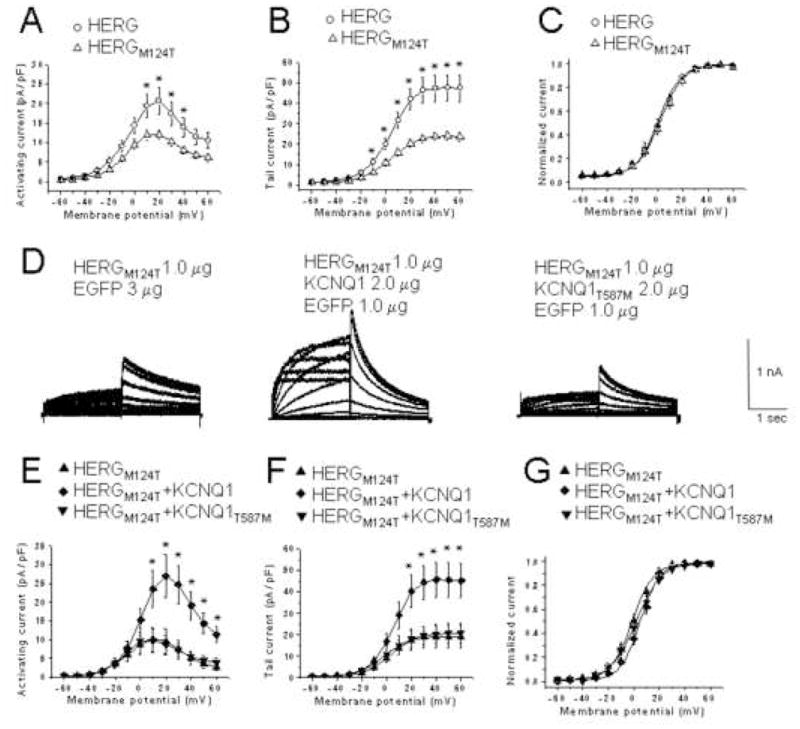

We next determined whether co-expression of KCNQ1 affects selected HERG mutants. In Xenopus oocytes, the acquired LQTS-associated variant HERGM124T showed reduced current amplitude, although kinetics were not significantly altered.18 Expressed in CHO cells, HERGM124T current was decreased 2 fold compared to WT (Figures 4A and B). The mean peak tail currents at −50 mV following a test pulse to + 40 mV for 1 μg of HERG and 1 μg of HERGM124T were 47.3 ± 6.5 pA/pF (n=12) and 23.8 ± 2.1 pA/pF (n=11), respectively. The current-voltage relationship of normalized tail currents revealed comparable V1/2 and slope factors (Figure 4C). Co-transfection with WT KCNQ1 boosted HERGM124T current levels to those observed with WT HERG (compare Figures 4A and 4E, or 4B and 4F).

Figure 4. KCNQ1 co-expression restores HERGM124T current to WT levels.

Peak activating (A) and tail (B) current-voltage relationships for WT HERG (1 μg, n = 12) and HERGM124T (1 μg, n = 11). *, P ≤ 0.05 versus WT HERG. (C), Normalized peak tail currents for HERG (n = 12) and HERGM124T (n = 11). (D), Representative currents from cells expressing HERGM124T, HERGM124T+KCNQ1 or HERGM124T +KCNQ1T587M. Current-voltage relationship of activating (E) and tail currents (F) for HERGM124T (n=8), HERGM124T + WT KCNQ1 (n = 9), and HERGM124T + KCNQ1T587M (n=8). Dofetilide insensitive component subtracted. *, P ≤ 0.05 versus HERG M124T. (G), Normalized I-V relationships of peak tail currents for HERGM124T (n= 8), HERGM124T + KCNQ1 (n=9), and HERGM124T + KCNQ1T587M (n=8).

When we substituted KCNQ1T587M for WT KCNQ1, this effect was no longer achieved (Figures 4E and F). The mean amplitude of the tail currents was 45.6 ± 8.1 pA/pF (n=9) for HERGM124T plus KCNQ1, which was significantly bigger than 19.0 ± 5.2 pA/pF (n=8) for HERGM124T or 20.2 ± 4.5 pA/pF (n = 8) for HERGM124T plus KCNQ1T587M (Figure 4F). Mean V1/2 values for HERGM124T, HERGM124T plus KCNQ1, and HERGM124T plus KCNQ1T587M were − 0.4 ± 5.5 mV (n=8, slope factor 8.3 ± 0.9), 5.5 ± 5.9 mV (n=9, slope factor 7.8 ± 1.1) and 2.2 ± 9.4 mV (n=8, slope factor 9.0 ± 2.2), respectively (Figure 4G).

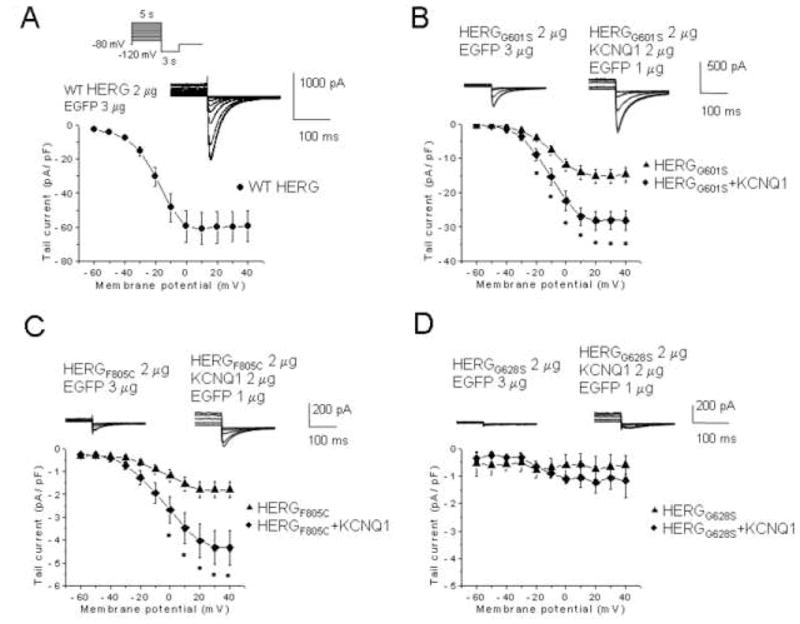

We next considered whether KCNQ1 selectively improves the defects of trafficking-deficient LQTS2 mutants. HERG variants G601S and F805C are defective in intracellular trafficking.19–21 In contrast, HERGG628S affects the pore region; the mutant is fully glycosylated and reaches the cell surface.21 The amplitudes of the activating currents produced by G601S, F805C and G628S mutants are too small to evaluate with the pulse protocol shown in Figure 1. For this reason, we monitored recovery from inactivation (inset, Figure 5A).22;23 KCNQ1 co-expression with the trafficking defective HERGG601S19 increased current density from −14.8 ± 2.2 pA/pF (n=12) to −28.1 ± 2.8 pA/pF (n=12) (P<0.05) (Figure 5B). Similarly, F805C20 produced tiny currents when expressed by itself (−1.8 ± 0.3 pA/pF, n=15), but was partially rescued after KCNQ1 co-expression (−4.3 ± 0.7 pA/pF, n=15, P<0.05) (Figure 5C). Co-expression of KCNQ1 with the pore-mutant HERGG628S did not improve the phenotype (Figure 5D).

Figure 5. Effects of KCNQ1 co-expression on current amplitudes of LQT2 mutant channels.

Currents were elicited by 5 s depolarizing pulses ranging from −60 mV to +40 mV, peak tail currents were measured during a 3 s pulse to −120 mV, and plotted as a function of the prepulse potential; the holding potential was − 80mV. Inset, voltage protocol. Dofetilide sensitive currents are represented. (A) WT HERG, (B) HERGG601S, (C) F805C, or (D) G628S co-expressed with either carrier cDNA (EGFP) or with KCNQ1. G601S, n = 12; G601S + KCNQ1, n = 12; F805C, n = 15, F805C + KCNQ1, n = 15; G628S, n = 5, G628S + KCNQ1, n = 4. *, P ≤ 0.05 by one-way ANOVA versus HERGG601S or HERGF805C.

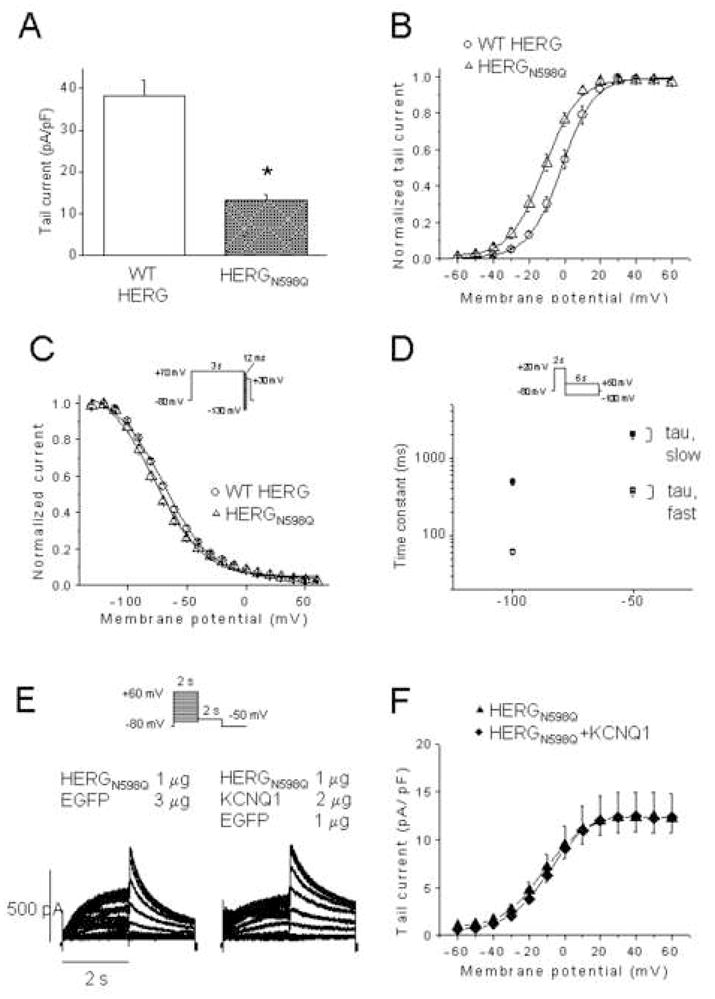

The HERGN598Q mutation is glycosylation deficient and causes a decrease in IHERG due to decreased stability at the plasma membrane.24 To determine whether KCNQ1 co-expression improves the stability of HERG at the membrane, we assessed KCNQ1 effects on HERGN598Q. Initially, we examined the properties of N598Q channels alone. Mean tail currents measured at −50 mV for 1 μg of HERG and 1 μg of HERGN598Q were 38.2 ± 3.9 pA/pF (n=17) and 13.1 ± 1.5 pA/pF (n=19), respectively (Figure 6A, P<0.01). When tail currents were plotted as a function of test potential fitted to a Boltzmann function, the V1/2 for HERG and HERGN598Q were −1.9 ± 1.9 mV (n=12, slope factors of 7.9 ± 0.2) and −11.4 ± 2.1 mV (n=9, slope factor 8.6 ± 0.5) respectively, a significant shift to negative potentials (P<0.01, Figure 6B). Similarly, when the inactivation process was analyzed with the voltage clamp protocol shown in figure 5A, the V1/2 of inactivation yielded −70.4 ± 0.7 mV for HERG (n=8, slope factor 19.5 ± 0.7) and −77.2 ± 1.6 mV for N598Q (n=9, slope factor 20.2 ± 0.7) (Figure 6C). Thus, steady-state inactivation was shifted to negative potentials (P<0.01, Figure 6C). The fast and slow deactivation time constants at −100 and −50 mV showed no difference (Figure 6D). When HERGN598Q was coexpressed with KCNQ1, the tail currents measured at −50 mV after a depolarizing test pulse to + 40 mV were −12.3 ± 2.6 pA/pF (n=15) for HERGN598Q and −12.4 ± 1.6 pA/pF (n=15) for HERGN598Q plus KCNQ1 (P = n.s.; Figure 6F). Thus, co-expression of KCNQ1 does not appear to stabilize HERGN598Q at the plasma membrane.

Figure 6. HERGN598Q with reduced membrane residence time, not rescued by KCNQ1.

(A) Tail current density measured at -50 mV after a test pulse to + 20 mV of WT HERG (n = 17) and HERGN598Q (n=19). (B), Normalized I-V relationships for tail currents of WT HERG (n = 12) and HERGN598Q (n=9). (C), Normalized steady-state inactivation curves of WT HERG (n = 8) and HERGN598Q (n=9). (D), Deactivation time constants of WT HERG (open and closed circles, n=11) and HERGN598Q (n=9). (E), Representative traces from CHO cells expressing HERGN598Q, and HERGN598Q+KCNQ1. Inset, voltage protocol. Current-voltage relationship of tail currents of HERGN598Q (n=15) and HERGN598Q + KCNQ1 (n=15). Dofetilide sensitive currents only are represented.

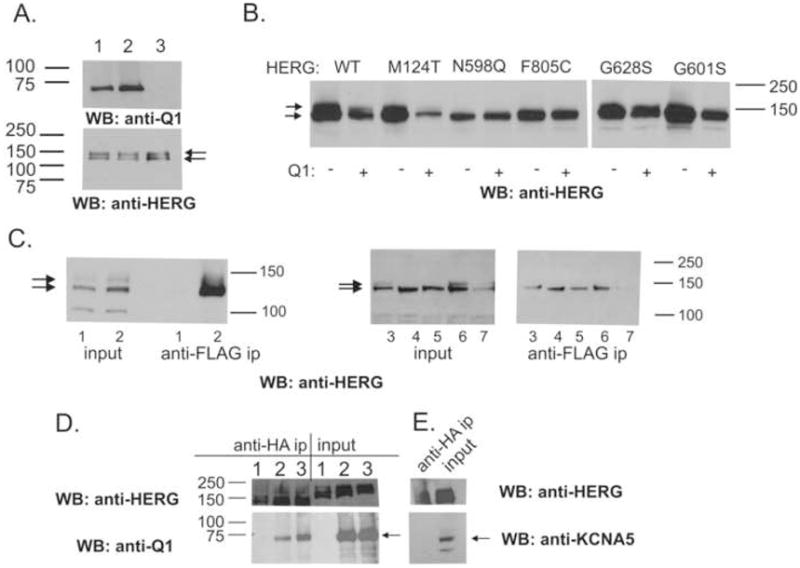

Effects of KCNQ1 on HERG processing

The glycosylation status of HERG is a frequently used measure of the intracellular processing of HERG.21;24–28 Multiple HERG-related bands are observed on Western blots of HERG-expressing cells. The lower Mr bands (100–135 kDa) represent incompletely/core glycosylated forms, while the higher band (155 kDa) represents the fully-glycosylated, mature form at the plasma membrane. Western blot analysis (Figure 7A) indicated that co-expression of WT KCNQ1 or KCNQ1T587M (upper panel) resulted in the identical glycosylation pattern of HERG (lower panel). Figure 7B addresses the processing of HERG variants in response to KCNQ1 co-transfection. Again, there was no discernible difference: The processing of incompletely processed variants like F805C, G601S and N598Q does not improve upon co-transfection with KCNQ1.

Figure 7. Effects of KCNQ1 co-expression on intracellular processing of HERG and KCNQ1-HERG-variant interactions.

(A) Western blot analysis of whole cell extracts prepared from stable, HERG-expressing CHO cells transfected with either 4 μgs of EGFP or KCNQ1 (Q1) cDNA. 10 μgs protein loaded. Cells transfected with KCNQ1 (lane 1), KCNQ1T587M (lane 2), or EGFP (lane 3). Probe: anti-KCNQ1 (top panel), anti-HERG (bottom panel). (B) 10 μgs of whole cell extracts from transiently transfected CHO cells, prepared for Western blot. WT, M124T, F805C and G628S present incompletely- (bottom arrow), as well as fully-glycosylated bands (top arrow). N598Q, F805C, and G601S show incompletely-glycosylated bands only. (C) Transfected cell extracts analyzed by Western blots (input) or following immunoprecipitation with antibody (anti-FLAG) specific for KCNQ1 and probed with anti-HERG. Lanes 1, 3xFLAG-ARHGAP6,29 plus HERG as a negative control. Lanes 2, 3xFLAG-KCNQ1 plus HERG WT; lanes 3, plus HERGM124T, lanes 4, plus HERGN598Q; lanes 5, plus HERGF805C; lanes 6, plus HERGG628S, lanes 7, plus HERGG601S. (D) Reciprocal reaction using an anti-HA immunoprecipitating antibody directed against HA-tagged HERG. Lanes 1, HA-HERG alone; lanes 2, HA-HERG plus WT KCNQ1; lanes 3, HA-HERG plus KCNQ1T587M; Western antibody directed against the FLAG epitope of KCNQ1 (anti-FLAG HRP-linked, 1:500, Sigma). (E) Cells transfected with HA-HERG plus KCNA5 cDNA immunoprecipitated with anti-HA linked beads. KCNA5 does not immunoprecipitate with HA-HERG. Panels D and E were parallel-processed.

Co-immunoprecipitation experiments indicate that KCNQ1 associates with all of the co-expressed HERG variants, regardless of effects on current levels (Figure 7C). Similar findings were recently reported by Biliczki et al.9 To control for unspecific association of HERG protein to the anti-FLAG linked immunoprecipitating beads, we performed parallel immunoprecipitations with a 3xFLAG-tagged protein (ARHGAP6) that does not associate with HERG (lanes 1, Figure 7C).29 Reciprocal immunoprecipitations directed against HA-tagged HERG similarly show co-precipitation of KCNQ1 (Figure 7D, lanes 1 and 2) and KCNQ1T587M. Co-immunoprecipitation of HA-HERG plus KCNA5, followed by and Western blot analysis did not show evidence of interaction (Figure 7E, left lane).

Discussion

The cardiac myocyte current IK, is composed of two pharmacologically distinguishable components, IKr and IKs, which are co-expressed.30 Considering the prior observation made by Ehrlich et al.8 that HERG increases membrane localization of KCNQ1 in transfected CHO cells, we hypothesized that the “IHERG booster” effect mediated by KCNQ1 may be linked to an event during the biogenesis of the channel, rather than through regulation of HERG biophysical properties at the membrane. In support of this idea, we demonstrated that KCNQ1 needs to be trafficking-competent before effects on HERG can be observed.

Co-expression of WT KCNQ1 with HERG mutants in mammalian cells can rescue some of the mutants. HERGM124T18 produced current levels comparable to WT HERG after co-expression with WT KCNQ1 but was not improved in the presence of the trafficking-defective KCNQ1T589M. This suggests that a simultaneous diminution of KCNQ1 trafficking function would aggravate the HERGM124T defect in patients with the acquired LQTS.

The G601S HERG LQT2 mutation results in a trafficking-deficient protein retained within the ER.19;25 The SERCA inhibitor thapsigargin, as well as IKr blocking drugs and culture at decreased temperature can partially rescue G601S.31;32 Our study shows that HERGG601S tail currents are increased 1.9 fold upon KCNQ1 co-expression. F805C is another trafficking-deficient mutation20 that can be rescued by culture at decreased temperature and thapsigargin.31 In our experiments, KCNQ1 increases HERGF805C currents 2.4 fold. At the other end of the spectrum, G628S mutates a strictly conserved glycine within the HERG selectivity filter and generates no current although it is inserted into the plasma membrane.21 Not surprisingly, KCNQ1 co-expression did not alleviate the phenotype of this mutant.

HERGN598Q represents a third class of variants that is glycosylation deficient but known to still traffic to the membrane although its stability at the plasma membrane is impaired.24 The N598Q phenotype was not altered after KCNQ1 co-expression (Figure 6), suggesting that KCNQ1 co-expression does not simply stabilize HERG at the plasma membrane.

Relation to previous studies

Ehrlich et al8 initially described the interaction between HERG and KCNQ1 proteins and currents in heterologous systems. Although they reported a change in the fast phase of deactivation of IHERG upon co-transfection with KCNQ1, we did not observe this (Figure 1F), either at RT or at 36°C. Indeed, KCNQ1 effects on HERG trafficking alone would not be expected to result in a change in HERG kinetics.

While our study was being reviewed, Biliczki et al 9 reported the effects of KCNQ1T587M on HERG current and membrane localization. In agreement with our studies, they found that unlike WT KCNQ1, KCNQ1T587M was not able to increase HERG current, that KCNQ1T587M and HERG could be co-immunoprecipitated, and that the glycosylation pattern of HERG was unaltered. However, these authors determined that the amount of HERG at the plasma membrane increases with KCNQ1 co-expression.

Another study investigated the combined effects of mutations in HERG and KCNQ1 on total cell currents33 in Xenopus oocytes where co-expression of HERG and KCNQ1 did not result in an enhancement of the HERG current and the two mutated channel proteins under investigation, KCNQ1R591H and HERGR328C, showed no functional interaction. Divergent intracellular processing pathways between Xenopus oocytes and the mammalian CHO cell expression systems may well account for the observed discrepancies.

Clinical implications

Compound heterozygosity in HERG and KCNQ1 has been observed in multiple LQTS patients.34;35 We find that KCNQ1 differentially affects LQT2 variants with varying underlying pathologies. Conversely, only trafficking competent KCNQ1 is able to influence HERG and variants, indicating that the clinical phenotypes produced by HERG mutations would be influenced by stimuli, either genetic or environmental, that control KCNQ1 trafficking. The results from our study emphasize the need for attention to KCNQ1/KCNH2 interactions in the course of studies of potential arrhythmia mechanisms and anti-arrhythmia therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

Funding: NIH RO1 HL69914 and RO1 HL090790 (to SK) and by NIH PO1 HL46681 (Project 4, to Dr. Jeffrey R. Balser, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine).

Stable HERG-expressing CHO cells were a kind gift from Drs. Carlos Vanoye and Al George at Vanderbilt University. The KCNA5 cDNA was a kind gift of Dr. Mike Tamkun (Colorado State University). We thank Dr. Jeff Balser for support throughout the study and Dr. Prakash Viswanathan for critical reading of the manuscript. The study was supported by NIH RO1 HL69914 and RO1 HL090790 (to SK) and by NIH PO1 HL46681 (Project 4, to Dr. Jeffrey R. Balser).

Abbreviations

- I

Current

- ECG

Electrocardiogram

- GFP

Green fluorescent protein

- hrs

Hours

- HERG

Human ether-a-go-go-related gene

- LQTS

Long QT Syndrome

- n.s

Not significant

- WT

Wild-type

- 4-AP

4-aminopyridine

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none for all authors

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Sanguinetti MC, Jurkiewicz NK. Two components of cardiac delayed rectifier K+ current. Differential sensitivity to block by class III antiarrhythmic agents. J Gen Physiol. 1990;96:195–215. doi: 10.1085/jgp.96.1.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanguinetti MC, Jiang C, Curran ME, Keating MT. A mechanistic link between an inherited and an acquired cardiac arrhythmia: HERG encodes the IKr potassium channel. Cell. 1995;81:299–307. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warmke JW, Ganetzky B. A family of potassium channel genes related to eag in Drosophila and mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:3438–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanguinetti MC, Curran ME, Zou A, Shen J, Spector PS, Atkinson DL, et al. Coassembly of K(V)LQT1 and minK (IsK) proteins to form cardiac I(Ks) potassium channel. Nature. 1996;384:80–3. doi: 10.1038/384080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barhanin J, Lesage F, Guillemare E, Fink M, Lazdunski M, Romey G. K(V)LQT1 and lsK (minK) proteins associate to form the I(Ks) cardiac potassium current. Nature. 1996;384:78–80. doi: 10.1038/384078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Q, Curran ME, Splawski I, et al. Positional cloning of a novel potassium channel gene. KVLQT1 mutations cause cardiac arrhythmias. Nat Genet. 1996;12:17–23. doi: 10.1038/ng0196-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curran ME, Splawski I, Timothy KW, Vincent GM, Green ED, Keating MT. A molecular basis for cardiac arrhythmia: HERG mutations cause long QT syndrome. Cell. 1995;80:795–803. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehrlich JR, Pourrier M, Weerapura M, et al. KvLQT1 modulates the distribution and biophysical properties of HERG. A novel alpha-subunit interaction between delayed rectifier currents. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1233–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309087200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biliczki P, Girmatsion Z, Brandes RP, et al. Trafficking-deficient long QT syndrome mutation KCNQ1-T587M confers severe clinical phenotype by impairment of KCNH2 membrane localization: Evidence for clinically significant IKr-IKs [alpha]-subunit interaction. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:1792–801. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brunner M, Peng X, Liu GX, et al. Mechanisms of cardiac arrhythmias and sudden death in transgenic rabbits with long QT syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2246–59. doi: 10.1172/JCI33578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamashita F, Horie M, Kubota T, et al. Characterization and Subcellular Localization of KCNQ1 with a Heterozygous Mutation in the C Terminus. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:197–207. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kupershmidt S, Snyders DJ, Raes A, Roden DM. A K+ Channel Splice Variant Common in Human Heart Lacks a C-terminal Domain Required for Expression of Rapidly Activating Delayed Rectifier Current. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27231–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanki H, Kupershmidt S, Yang T, Wells S, Roden DM. A Structural Requirement for Processing the Cardiac K+ Channel KCNQ1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:33976–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404539200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kupershmidt S, Yang IC, Hayashi K, et al. IKr drug response is modulated by KCR1 in transfected cardiac and noncardiac cell lines. FASEB J. 2003;17:2263–5. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1057fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vandenberg JI, Varghese A, Lu Y, Bursill JA, Mahaut-Smith MP, Huang CLH. Temperature dependence of human ether-a-go-go-related gene K+ currents. Am J Physiol. 2006;291:C165–C175. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00596.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nerbonne JM. Molecular basis of functional voltage-gated K+ channel diversity in the mammalian myocardium. J Physiol. 2000;525(Pt 2):285–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00285.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamashita F, Horie M, Kubota T, et al. Characterization and subcellular localization of kcnq1 with a heterozygous mutation in the C terminus. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:197–207. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayashi K, Shimizu M, Ino H, et al. Probucol aggravates long QT syndrome associated with a novel missense mutation M124T in the N-terminus of HERG. Clin Sci. 2004;107:175–82. doi: 10.1042/CS20030351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furutani M, Trudeau MC, Hagiwara N, et al. Novel mechanism associated with an inherited cardiac arrhythmia - Defective protein trafficking by the mutant HERG (G601S) potassium channel. Circulation. 1999;99:2290–4. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.17.2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ficker E, Obejero-Paz CA, Zhao S, Brown AM. The binding site for channel blockers that rescue misprocessed human long QT syndrome type 2 ether-a-gogo-related gene (HERG) mutations. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:4989–98. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107345200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou Z, Gong Q, Epstein ML, January CT. HERG channel dysfunction in human long QT syndrome. Intracellular transport and functional defects. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21061–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith PL, Baukrowitz T, Yellen G. The inward rectification mechanism of the HERG cardiac potassium channel. Nature. 1996;379:833–6. doi: 10.1038/379833a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spector PS, Curran ME, Zou A, Keating MT, Sanguinetti MC. Fast inactivation causes rectification of the IKr channel. J Gen Phys. 1996;107:611–9. doi: 10.1085/jgp.107.5.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gong Q, Anderson CL, January CT, Zhou Z. Role of glycosylation in cell surface expression and stability of HERG potassium channels. Am J Physiol. 2002;283:H77–H84. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00008.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petrecca K, Atanasiu R, Akhavan A, Shrier A. N-linked glycosylation sites determine HERG channel surface membrane expression. J Phys - London. 1999;515:41–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.041ad.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou Z, Gong Q, January CT. Correction of defective protein trafficking of a mutant HERG potassium channel in human long QT syndrome. Pharmacological and temperature effects. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31123–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.44.31123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakajima T, Hayashi K, Viswanathan PC, et al. HERG Is Protected from Pharmacological Block by {alpha}-1,2-Glucosyltransferase Function. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:5506–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605976200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang L, Dennis AT, Trieu P, et al. Intracellular Potassium Stabilizes hERG Channels for Export from Endoplasmic Reticulum. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:927–37. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.053793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Potet F, Petersen CI, Boutaud O, et al. Genetic screening in C. elegans identifies rho-GTPase activating protein 6 as novel HERG regulator. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;46:257–67. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanguinetti MC, Jurkiewicz NK. Delayed rectifier outward K+ current is composed of two currents in guinea pig atrial cells. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:H393–H399. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.260.2.H393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delisle BP, Anderson CL, Balijepalli RC, Anson BD, Kamp TJ, January CT. Thapsigargin selectively rescues the trafficking defective LQT2 channels G601S and F805C. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:35749–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305787200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rajamani S, Anderson C, Anson BD, January CT. Pharmacological rescue of human K+ channel long-QT2 mutations - Human ether-a-go-go-related gene rescue without block. Circulation. 2002;105:2830–5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000019513.50928.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grunnet M, Behr ER, Calloe K, et al. Functional assessment of compound mutations in the KCNQ1 and KCNH2 genes associated with long QT syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:1238–49. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamaguchi M, Shimizu M, Ino H, et al. Compound heterozygosity for mutations Asp611-->Tyr in KCNQ1 and Asp609-->Gly in KCNH2 associated with severe long QT syndrome. Clin Sci. 2005;108:143–50. doi: 10.1042/CS20040220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berthet M, Denjoy I, Donger C, et al. C-terminal HERG mutations - The role of hypokalemia and a KCNQ1-associated mutation in cardiac event occurrence. Circulation. 1999;99:1464–70. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.11.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]