Abstract

Objective To evaluate whether including a test for faecal calprotectin, a sensitive marker of intestinal inflammation, in the investigation of suspected inflammatory bowel disease reduces the number of unnecessary endoscopic procedures.

Design Meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy studies.

Data sources Studies published in Medline and Embase up to October 2009.

Interventions reviewed Measurement of faecal calprotectin level (index test) compared with endoscopy and histopathology of segmental biopsy samples (reference standard).

Inclusion criteria Studies that had collected data prospectively in patients with suspected inflammatory bowel disease and allowed for construction of a two by two table. For each study, sensitivity and specificity of faecal calprotectin were analysed as bivariate data to account for a possible negative correlation within studies.

Results 13 studies were included: six in adults (n=670), seven in children and teenagers (n=371). Inflammatory bowel disease was confirmed by endoscopy in 32% (n=215) of the adults and 61% (n=226) of the children and teenagers. In the studies of adults, the pooled sensitivity and pooled specificity of calprotectin was 0.93 (95% confidence interval 0.85 to 0.97) and 0.96 (0.79 to 0.99) and in the studies of children and teenagers was 0.92 (0.84 to 0.96) and 0.76 (0.62 to 0.86). The lower specificity in the studies of children and teenagers was significantly different from that in the studies of adults (P=0.048). Screening by measuring faecal calprotectin levels would result in a 67% reduction in the number of adults requiring endoscopy. Three of 33 adults who undergo endoscopy will not have inflammatory bowel disease but may have a different condition for which endoscopy is inevitable. The downside of this screening strategy is delayed diagnosis in 6% of adults because of a false negative test result. In the population of children and teenagers, 65 instead of 100 would undergo endoscopy. Nine of them will not have inflammatory bowel disease, and diagnosis will be delayed in 8% of the affected children.

Conclusion Testing for faecal calprotectin is a useful screening tool for identifying patients who are most likely to need endoscopy for suspected inflammatory bowel disease. The discriminative power to safely exclude inflammatory bowel disease was significantly better in studies of adults than in studies of children.

Introduction

The incidence of inflammatory bowel disease is on the increase in both adults and children.1 2 The disorder includes two major forms of chronic intestinal inflammation: Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Suspicion is raised in patients with persistent (≥4 weeks) or recurrent (≥2 episodes in six months) abdominal pain and diarrhoea. Additionally, rectal bleeding, weight loss, or anaemia increase the probability of the condition.3 4 Pathognomonic signs or symptoms do not exist. Endoscopic evaluation with histopathological sampling are generally considered indispensable in the investigation of patients with suspected inflammatory bowel disease.3 4 Many patients consider endoscopy and the required bowel preparation to be uncomfortable.5 In a relatively large proportion of people with suspected inflammatory bowel disease the results of endoscopy will be negative.6 A third of adults with bleeding related symptoms have no abnormalities on endoscopy, and this proportion increases to half with non-bleeding symptoms such as diarrhoea, abdominal pain, and weight loss. Identification of low risk patients would reduce the number of unnecessary invasive endoscopic procedures. Conversely, doctors would like to be able to identify those with a sufficiently high likelihood of inflammatory bowel disease to justify urgency for endoscopy.

Use of a simple, non-invasive, and cheap screening test to make a presumptive diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease would help to reach these goals. Determination of calprotectin levels in stools could be a good screening method. Calprotectin is a major protein found in the cytosol of inflammatory cells.7 The protein is stable in stool samples for up to seven days at room temperature and one sample of less than 5 g is sufficient for a reliable measurement.8 These qualities allow for stool sample collection at home and potential delays in transport to the laboratory.

Since 2000, faecal calprotectin has been evaluated in numerous diagnostic studies in both adult and paediatric populations. Many of these studies included healthy people on one side of the patient spectrum and patients with known inflammatory bowel disease on the other. Both extremes give cause to overestimation of diagnostic accuracy relative to the practical situation, where screening is necessary because it is difficult to clinically distinguish between those who do and those who do not need urgent endoscopy. The doctor is then left with little guidance about the usefulness of faecal calprotectin as a screening test. We carried out a meta-analysis to evaluate whether adding faecal calprotectin testing to the investigation of patients with suspected inflammatory bowel disease reduced the number of unnecessary endoscopies.

Methods

Eligible studies were those that assessed the diagnostic accuracy of faecal calprotectin testing in patients with inflammatory bowel disease suspected on clinical grounds. Data collection had to be done prospectively with stool sampling (index test) before endoscopic evaluation including histopathological verification of segmental biopsies (reference standard).

Identification of studies

We searched for diagnostic studies published in Medline and Embase up to October 2009. The search strategy for Medline was (“Leukocyte L1 Antigen Complex”[Mesh] OR “calprotectin”[tw]) AND (“Inflammatory Bowel Diseases”[Mesh] OR “inflammatory bowel disease”[tw] OR “inflammatory bowel diseases”[tw] OR “IBD”[tw] OR “Crohn”[tw] OR “Colitis”[tw]). For Embase we used (“calgranulin”/exp OR “calprotectin”/exp) AND (“enteritis”/exp OR “inflammatory bowel disease”/exp OR “inflammatory bowel diseases”/exp OR “ibd” OR “crohn” OR “colitis”/exp) AND [embase]/lim.

We restricted our search to studies published in English only. Duplicate articles identified in both Medline and Embase were manually deleted using Reference Manager, version 11 (Thomson Reuters, Philadelphia, PA). For further relevant studies we checked the reference lists of identified trials.

Study selection and data extraction

The first selection was carried out by one reviewer (PFvR), on the basis of the title and abstract. The full paper of each potentially eligible study was then obtained. Two reviewers (PFvR, EVdV) independently assessed eligible studies for inclusion. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. The following characteristics were extracted from each selected study: age range, prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the study population (pretest probability); percentage of patients with Crohn’s disease and percentage with ulcerative colitis in the group of confirmed cases with inflammatory bowel disease; reference standard; faecal calprotectin assay; cut-off value for faecal calprotectin; and data for construction of a two by two table. Authors were contacted in cases where information was missing to construct a two by two table.

Assessment of methodological quality

Study quality was assessed using the QUADAS (QUality Assessment of studies of Diagnostic Accuracy included in Systematic reviews) checklist.9 Each item is scored as “yes,” “no,” or “unclear.” We did not calculate summary scores because their interpretation is problematic and potentially misleading.10 From the QUADAS checklist we chose seven of the best differentiating items (box).

Items chosen to score from QUADAS checklist9

Was the spectrum of patients representative of those who will receive the test in practice?

Was the reference standard likely to correctly classify patients with inflammatory bowel disease?

Was the time period between reference standard and index test short enough to be reasonably sure that the target condition did not change between the two tests?

Did the whole sample or a random selection of the sample receive verification using a reference standard?

Did patients receive the same reference standard regardless of the index test result?

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test?

Were withdrawals from the study explained?

Patients representative of those to receive the test in practice

If patients had suspected inflammatory bowel disease on the basis of their clinical presentation, we scored the studies as “yes.” We scored studies as “no” that excluded patients with “other somatic bowel disorders than inflammatory bowel disease or irritable bowel syndrome.” Studies that recruited a group of healthy controls and a group known to have inflammatory bowel disease were also scored as “no,” because diagnostic test accuracy is likely to be overestimated in such a design. If information was insufficient to make a judgment we scored the study as “unclear.”

Accuracy of reference standard

No reference standard in the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease is 100% sensitive or 100% specific. However, the Porto criteria that have been formulated by the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition approach an optimal diagnostic strategy for patients with suspected inflammatory bowel disease.3 The investigation involves endoscopy of both the upper and the lower gastrointestinal tract, with biopsies from each segment of the gastrointestinal tract. To obtain a score of “yes,” the studies had to have a reference standard that consisted of at least ileocolonoscopy including histology. When the ileum was not intubated or no biopsies were taken, we coded the study as “no.” If colonoscopy and histology were done but information on ileal intubation was insufficient we scored the study as “unclear.”

Suitable time between reference standard and index test

Ideally, faecal sampling is done shortly before endoscopy, before preparation of the bowel. A delay of up to one month was not considered problematic as it is unlikely that mucosal inflammation spontaneously disappears within this period. We therefore scored studies with a delay of less than one month as “yes” and those with a delay of more than one month as “no.” If insufficient information was provided we scored the study as “unclear.”

Sample type verified using reference standard

Partial verification bias occurs when not all of the study group receives confirmation of the diagnosis by endoscopy. When it was clear from the study that all patients who collected faeces for measurement of calprotectin level had their disease status verified by endoscopy, we scored this item as “yes.” Studies scored “no” if some of the patients did not undergo the reference standard and the selection of patients to receive the reference standard was not random.

Consistency of reference standard

Differential verification bias occurs when the performance of the faecal calprotectin test is verified by a different reference standard. If patients had inflammatory bowel disease verified by the same type of endoscopy we scored this item as “yes.” If some patients received verification by sigmoidoscopy instead of another procedure, such as colonoscopy, we scored this item as “no,” as there is a risk of missing right sided colitis.

Interpretation of results

Faecal sampling for measurement of calprotectin level was carried out before endoscopy, and analysis was mostly done by laboratory technicians who had no information on the endoscopy results. However, this design precluded that faecal calprotectin results were sometimes known to the endoscopist before endoscopic evaluation. This could influence the interpretation of macroscopic abnormalities seen during endoscopy. In that case we scored this item as “no.” If insufficient information was provided we scored the study as “unclear.”

Explanation of withdrawals

When it was clear what happened to all patients who entered the study, we scored this item as “yes.” When withdrawals were not explained, we scored this item as “no.”

Data synthesis and analysis

We calculated sensitivity and specificity for each study and analysed these as bivariate data by methods for diagnostic meta-analysis.11 This approach accounts for possible within study negative correlation between sensitivity and specificity. We present the data as forest plots and receiver operating characteristic curves. Forest plots display the diagnostic probabilities of individual studies, the corresponding 95% confidence intervals, and squares with area proportional to study weight in the meta-analysis. The receiver operating characteristic curves show individual study data points as circles, with size proportional to study weight, the 95% confidence and 95% prediction regions around the pooled estimate, and the hierarchical summary curve resulting from the hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic model. We carried out predefined subgroup analyses for adults and for children. The z test (two sided at 5% level of significance) was used to separately compare the pooled estimates of sensitivity and specificity of the two groups. Finally, we calculated the average likelihood ratio of the positive and negative test result for both subgroups. Computations were carried out with the library DiagMeta of the R-package (www.r-project.org/),12 and with STATA (version 11), in particular the metandi commands.

Results

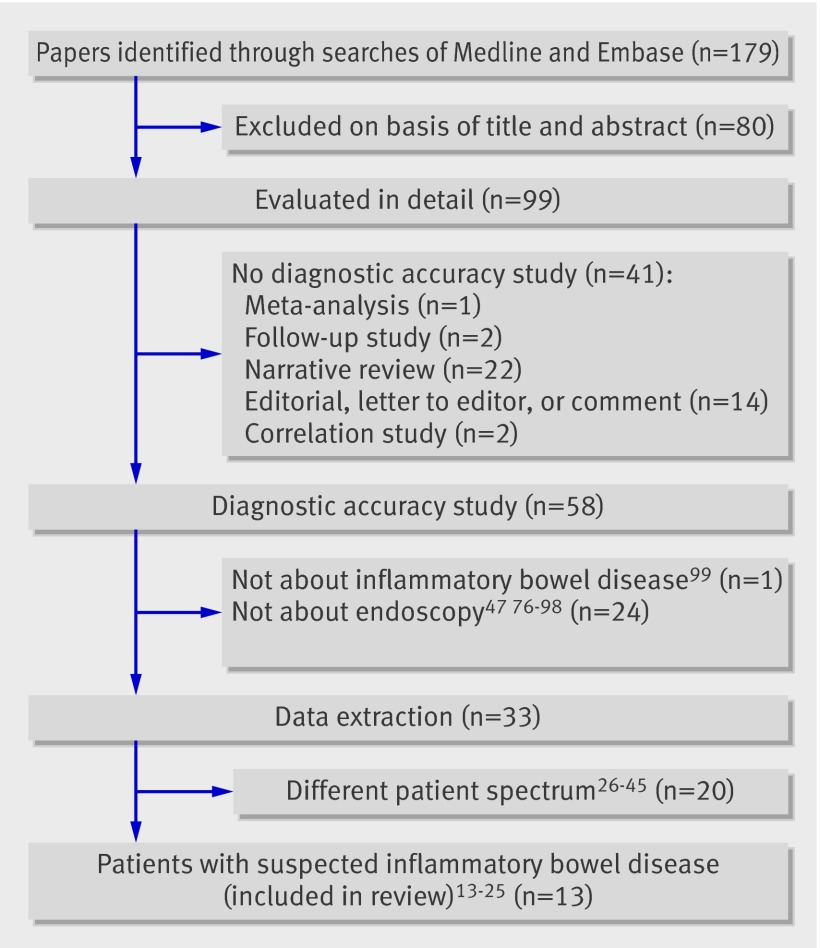

The study includes results of electronic searches up to 14 October 2009. A total of 179 papers were identified, of which 99 were retrieved for full text review. Of these, 66 were excluded as they were unrelated to diagnostic accuracy studies or did not use endoscopy as the reference standard. Of 33 diagnostic accuracy studies that compared faecal calprotectin testing with endoscopy as the reference test, 13 focused on the desired patient spectrum and were included in the final analysis (fig 1). Table 1 lists the characteristics of the 33 studies in which endoscopy was used as the reference standard and explains why 20 were unsuitable for inclusion.

Fig 1 Study selection

Table 1.

Overview of 13 included and 20 excluded diagnostic accuracy studies comparing faecal calprotectin with endoscopy

| Study | Patient spectrum | Age group | Target disease |

|---|---|---|---|

| Included studies: | |||

| Limburg 200018 | Chronic diarrhoea | Adults | Inflammatory bowel disease* |

| Tibble 200025 | Suspected inflammatory bowel disease | Adults | Inflammatory bowel disease† |

| Schroder 200723 | Chronic diarrhoea | Adults | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| Schoepfer 200721 | Suspected inflammatory bowel disease | Adults | Inflammatory bowel disease* |

| Otten 200819 | Suspected inflammatory bowel disease | Adults | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| Schoepfer 200822 | Suspected inflammatory bowel disease | Adults | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| Bunn 200114 | Suspected inflammatory bowel disease | Children and teenagers | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| Fagerberg 200516 | Suspected inflammatory bowel disease | Children and teenagers | Inflammatory bowel disease* |

| Canani 200615 | Suspected inflammatory bowel disease | Children and teenagers | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| Kolho 200617 | Suspected inflammatory bowel disease | Children and teenagers | Inflammatory bowel disease‡ |

| Sidler 200824 | Suspected inflammatory bowel disease | Children and teenagers | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| Ashorn 200913 | Suspected inflammatory bowel disease | Children and teenagers | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| Perminow 200920 | Suspected inflammatory bowel disease | Children and teenagers | Inflammatory bowel disease§ |

| Excluded studies: | |||

| Summerton 200244 | Miscellaneous gastrointestinal tract symptoms | Adults | Intestinal inflammation |

| Costa 200328 | Out patient clinic | Adults | Organic disorder |

| Silberer 200540 | Known inflammatory bowel disease | Adults | Organic disorder |

| Kaiser 200735 | Known inflammatory bowel disease | Adults | Active disease |

| D’Inca 200729 | Known inflammatory bowel disease | Adults | Intestinal inflammation |

| Shitrit 200739 | Miscellaneous gastrointestinal tract symptoms | Adults | Abnormal histology |

| Langhorst 200836 | Known inflammatory bowel disease | Adults | Active disease |

| Sipponen 200841 | Known Crohn’s disease | Adults | Active disease |

| Sipponen 200842 | Known Crohn’s disease | Adults | Mucosal healing |

| Sipponen 200843 | Known Crohn’s disease | Adults | Active disease |

| Jones 200834 | Known Crohn’s disease | Adults | Active disease |

| Wagner 200845 | Known inflammatory bowel disease | Adults | Active disease |

| Damms 200830 | Miscellaneous gastrointestinal tract symptoms | Adults | Intestinal inflammation |

| Schoepfer 200938 | Known ulcerative colitis | Adults | Active disease |

| Jeffery 200933 | Miscellaneous gastrointestinal tract symptoms | Adults | Organic disorder |

| Carroccio 200327 | Chronic diarrhoea | Adults and children | Organic disorder |

| Fagerberg 200732 | Known and suspected inflammatory bowel disease | Children | Active disease |

| Diamanti 200831 | Known inflammatory bowel disease | Children | Active disease |

| Canani 200826 | Known inflammatory bowel disease | Children | Active disease |

| Quail 200937 | Known inflammatory bowel disease | Children | Inflammatory bowel disease¶ |

*2×2 table for target condition inflammatory bowel disease is constructed from data presented in original paper.

†Post hoc exclusion of patients with ulcerative colitis, as they “do not normally pose a diagnostic problem and a screening test is therefore unlikely to be required or helpful.”

‡Over 50% of faeces samples were taken up to three months after endoscopy.

§2×2 table based on published and unpublished data.

¶Review bias (study design not according to prototype flow diagram diagnostic accuracy study).

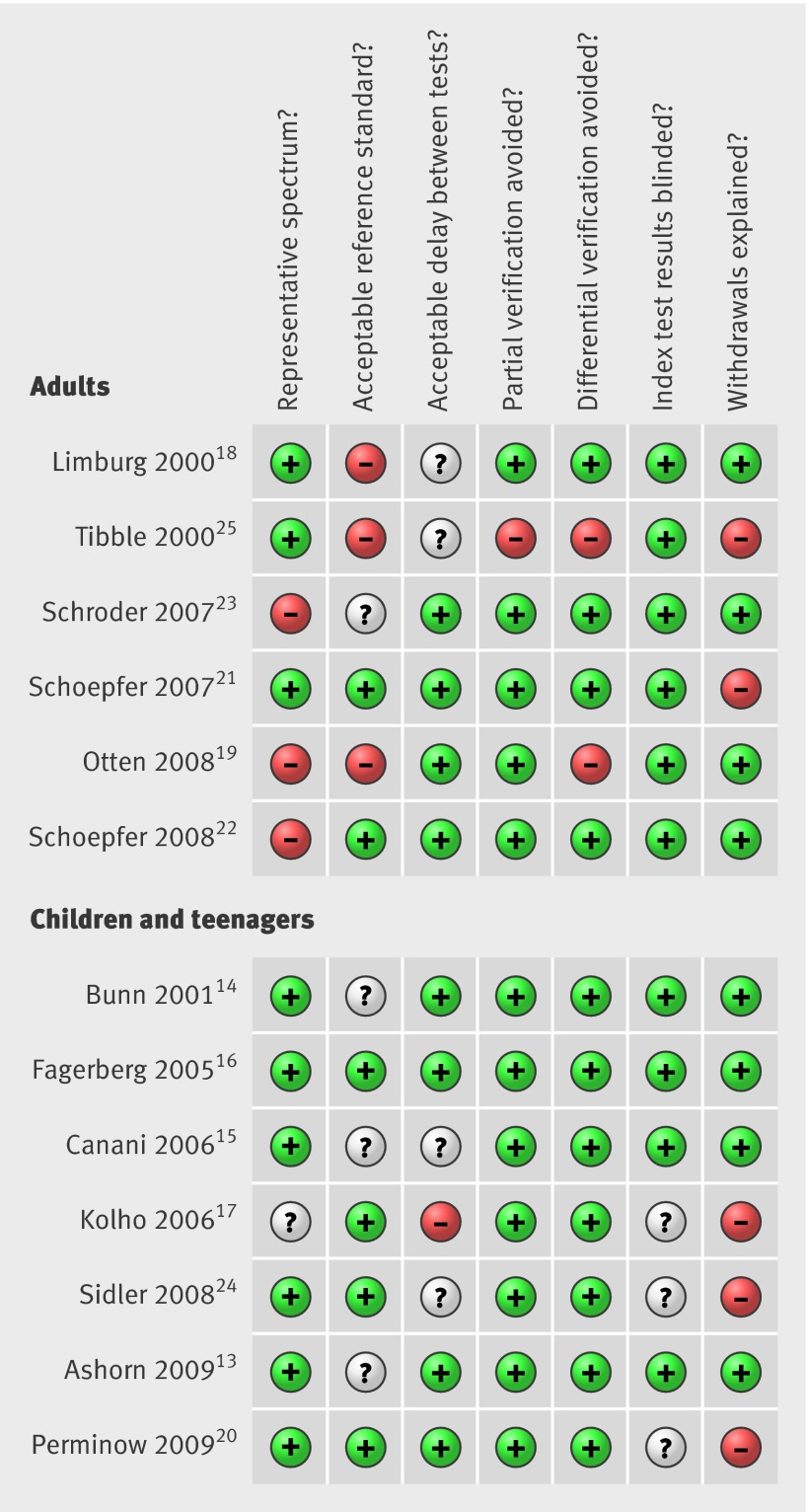

The final analysis included six studies in adults and seven in children and teenagers (age range 10 months to 19.9 years). The faecal calprotectin test was used in a total of 670 patients in the adult studies and 371 in the remainder. Inflammatory bowel disease was confirmed in 32% (n=215) of the adults and in 61% (n=226) of the children and teenagers (table 2). The methodological quality of the studies in children and teenagers was better than that of the studies in adults (fig 2). All studies used a prospective study design and enrolled consecutive outpatients with suspected inflammatory bowel disease. Selection bias in three adult studies was caused by the post hoc exclusion of patients.19 22 23 In four adult studies endoscopy was suboptimal as the ileum was not intubated or histology was not done.18 19 23 25 In three studies in children and teenagers withdrawals were not explained.17 20 24 Three studies excluded patients with gross rectal bleeding, as this symptom would usually prompt endoscopic evaluation without preliminary stool testing.15 18 23 Partial and differential verification was appropriately reported and bias was prevented in all but two adult studies.19 25 Blinding of index test results was reported in all but three studies in children and teenagers.17 20 24

Table 2.

Population and study characteristics of included studies

| Study | No of patients included in meta-analysis | Age range (years) | Prevalence (%) | Patients with rectal bleeding included | Faecal calprotectin assay | Reference standard | Ileal intubation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Crohn’s disease: ulcerative colitis* | Assay type | Cut-off value (μg/g) | ||||||

| Adults | |||||||||

| Limburg 200018 | 110 | 21-85 | 15 | NK | No | PhiCal | 100 | Colonoscopy | No |

| Tibble 200025 | 210 | 16-85 | 14 | 100:0 | Yes | Roseth | 150 | Colonoscopy (67%) | NK |

| Schroder 200723 | 76 | 20-75 | 59 | 56:44 | No | PhiCal | 24 | Colonoscopy and histology | NK |

| Schoepfer 200721 | 56 | 19-88 | 64 | 67:33 | Yes | PhiCal | 50 | Colonoscopy and histology | Yes |

| Otten 200819 | 114 | NK | 20 | NK | Yes | PhiCal | 50 | Colonoscopy†, histology (50%) | NK |

| Schoepfer 200822 | 94 | 20-79 | 68 | 56:44 | Yes | PhiCal | 50 | Colonoscopy and histology | Yes |

| Total | 670 | — | 32 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Children and teenagers | |||||||||

| Bunn 200114 | 22 | 2.3-15.0 | 59 | 15:69 | Yes | Roseth | 32 | Colonoscopy and histology | NK |

| Fagerberg 200516 | 36 | 6.5-17.8 | 56 | 50:35 | Yes | PhiCal | 50 | Colonoscopy and histology | Yes |

| Canani 200615 | 45 | NK | 60 | 63:37 | No | PhiCal | 95 | Colonoscopy and histology | NK |

| Kolho 200617 | 57 | 0.9-18.0 | 54 | 29:52 | Yes | PhiCal | 50 | Colonoscopy and histology | Yes |

| Sidler 200824 | 61 | 2.2-16.0 | 51 | 97:3 | Yes | PhiCal | 50 | Upper GI endoscopy, colonoscopy, and histology | Yes |

| Ashorn 200913 | 55 | 5.8-19.9 | 80 | 34:57 | Yes | PhiCal | 100 | Upper GI endoscopy, colonoscopy, and histology | NK |

| Perminow 200920 | 95 | 0.8-18.0 | 63 | 63:31 | Yes | PhiCal | 50 | Upper GI endoscopy, colonoscopy, and histology | Yes |

| Total | 371 | — | 61 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

NK=not known; GI=gastrointestinal. PhiCal (Calprest) is a commercial enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (CALPRO AS, Oslo, Norway). Roseth is an in house enzyme linked immunosorbent assay8 (results obtained with Roseth can be compared with those obtained with Phical by multiplying former by a factor of 5.74

*In children and teenagers remainder of inflammatory bowel disease cases was classified as indeterminate colitis.

†4% sigmoidoscopy.

Fig 2 Summary of methodological quality of included studies on basis of review authors’ judgments on seven best differentiating items from QUADAS checklist for each study

Diagnostic accuracy indices

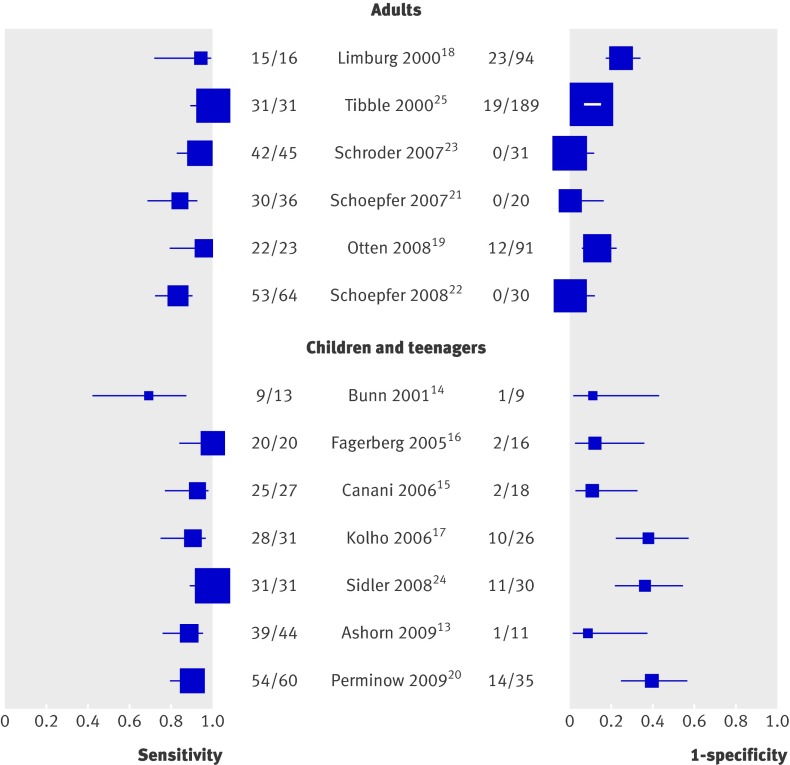

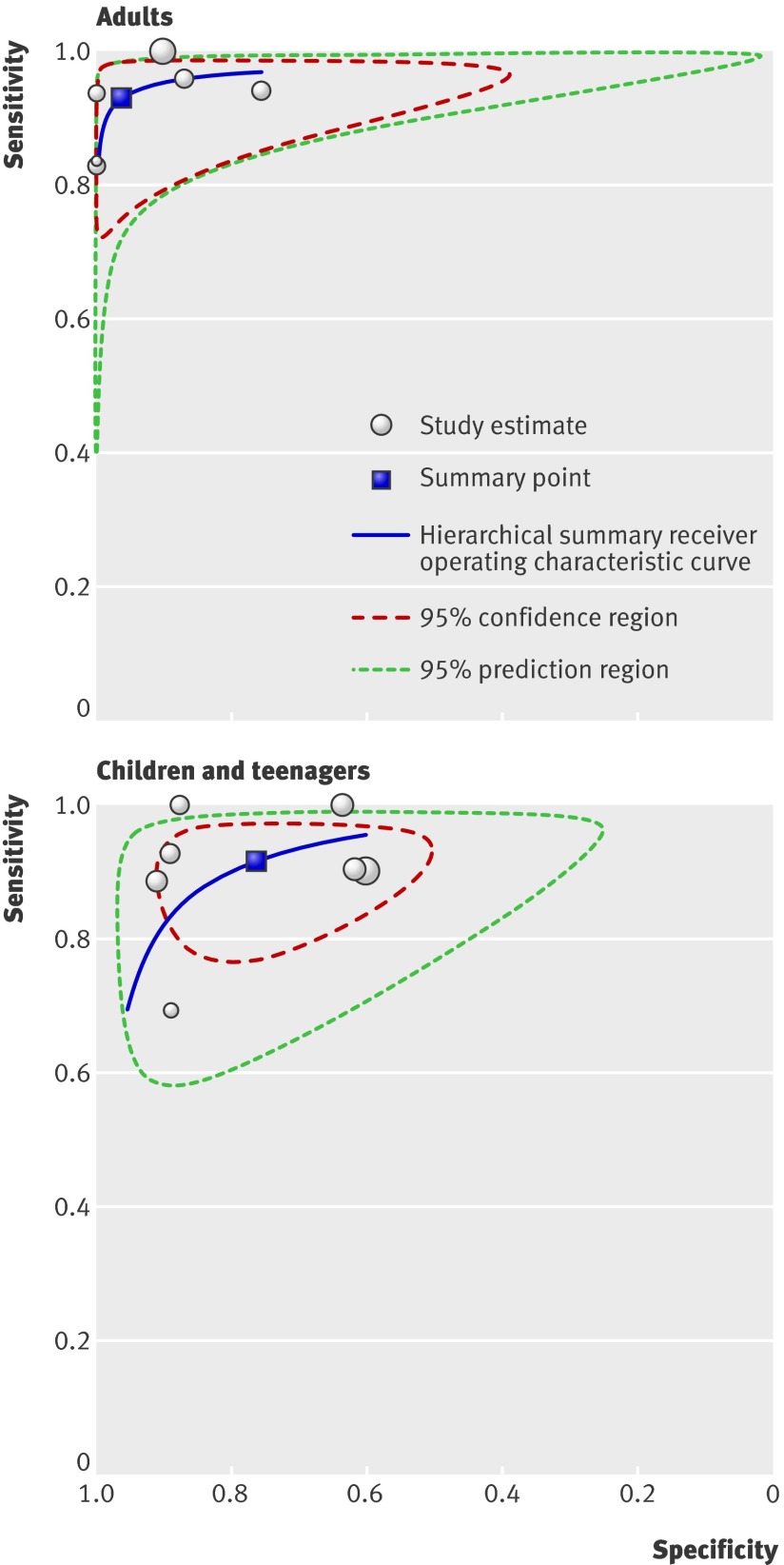

Per age group analyses—Figure 3 presents the forest plots of sensitivity (true positive rate) and 1−specificity (false positive rate) for the 13 studies. Figure 4 presents the diagnostic values of the studies in a hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic graph for adults and for children and teenagers. For adults the sensitivity was 0.93 (0.85 to 0.97) and specificity 0.96 (0.79 to 0.99), and the corresponding values for children and teenagers were 0.92 (0.84 to 0.96) and 0.76 (0.62 to 0.86). The difference between specificities of the two groups was significant (P=0.048).

Fig 3 Forest plots of sensitivity and 1−specificity of faecal calprotectin test in distinguishing inflammatory bowel disease from non-inflammatory bowel disease. Plots display diagnostic probabilities of included studies, corresponding 95% confidence intervals, and squares with area proportional to study weight in meta-analysis

Fig 4 Receiver operating characteristic graph of faecal calprotectin test in distinguishing inflammatory bowel disease from non-inflammatory bowel disease, with 95% confidence region and 95% prediction regions for studies in adults and in children and teenagers. The confidence region consists of the most likely values of true summary sensitivity and specificity. It indicates the precision with which the summary points are estimated. The prediction region predicts the true sensitivity and specificity of a future study. The size of this region reflects the variation between studies. Individual study estimates are represented as circles, with size proportional to study weight

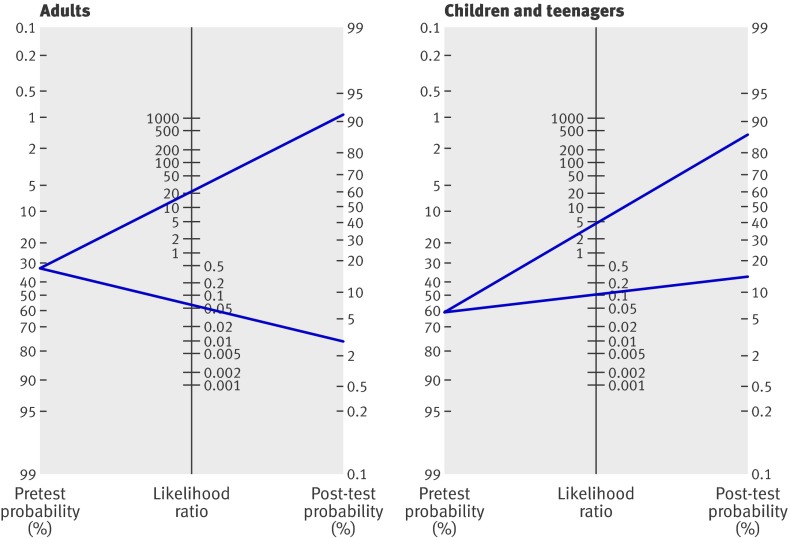

Post-test probability of inflammatory bowel disease—On the basis of the pooled estimates of sensitivity and specificity, the average likelihood ratio of the positive and negative test result was calculated for adults and for children and teenagers. The use of faecal calprotectin testing changed the post-test probability of inflammatory bowel disease in both subgroups (fig 5). In adults with suspected inflammatory bowel disease and a pretest probability of 32% an abnormal test result for calprotectin concentration increases the probability of inflammatory bowel disease to 91% (95% confidence interval 77% to 97%), whereas a normal test result for calprotectin concentration reduces the probability to 3% (1% to 11%). In children and teenagers with suspected inflammatory bowel disease the pretest probability is 61%. An abnormal test result for calprotectin increases the probability to 86% (78% to 92%), whereas a normal test result for calprotectin reduces the probability to 15% (7% to 28%).

Fig 5 Fagan’s nomogram for faecal calprotectin showing post-test probability of inflammatory bowel disease after abnormal test result (upper line) and normal test result (lower line) in adults and in children and teenagers

Discussion

In our meta-analysis we included six studies in adults and seven in children and teenagers, which were selected for their methodological robustness. In these studies data collection was done prospectively in a consecutive series of patients with suspected inflammatory bowel disease. All included studies used the fully paired design where patients first undergo faecal calprotectin testing and then endoscopy. In the adult studies the pooled sensitivity of faecal calprotectin testing was 0.93 (95% confidence interval 0.85 to 0.97) and the pooled specificity was 0.96 (0.79 to 0.99). The corresponding values in the studies in children and teenagers were 0.92 (0.84 to 0.96) and 0.76 (0.62 to 0.86).

The lower specificity in the studies of children and teenagers was significantly different from that in the adult studies. Five adult studies that included a relatively large proportion of patients with irritable bowel syndrome had significantly higher specificity.19 21 22 23 25 This gastrointestinal syndrome, characterised by chronic abdominal pain and altered bowel habits in the absence of any organic cause, was hardly diagnosed (7%, 27/371) in the study population of children and teenagers. According to British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines, patients with irritable bowel syndrome without alarm features (including anaemia, weight loss, and age >50 years) do not need endoscopic evaluation, because of a low likelihood of identifying organic disease.46 The five adult studies that included a large proportion of patients with irritable bowel disease did not report the presence of alarm features. Absence of alarm symptoms is likely to overestimate the specificity of faecal calprotectin. In theory, the inclusion of infants and young children (under 5 years) in four of the studies could be a reason for lower specificity.14 17 20 24 At this age stool samples are usually collected from a nappy. This sampling technique could increase the level of faecal calprotectin because water is absorbed by the nappy.47 As most young patients with newly diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease are teenagers, we do not think that this mechanism played an important role. The choice of the faecal calprotectin cut point could be another reason for the higher specificity in adults. However, we found no difference between the groups in a subgroup analysis comparing studies using a cut point of ≤50 μg/g and of >50 μg/g. Prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease had no effect on specificity, just as with the exclusion of patients with rectal bleeding. Quality items also had no significant influence on diagnostic characteristics.

Implications of key findings

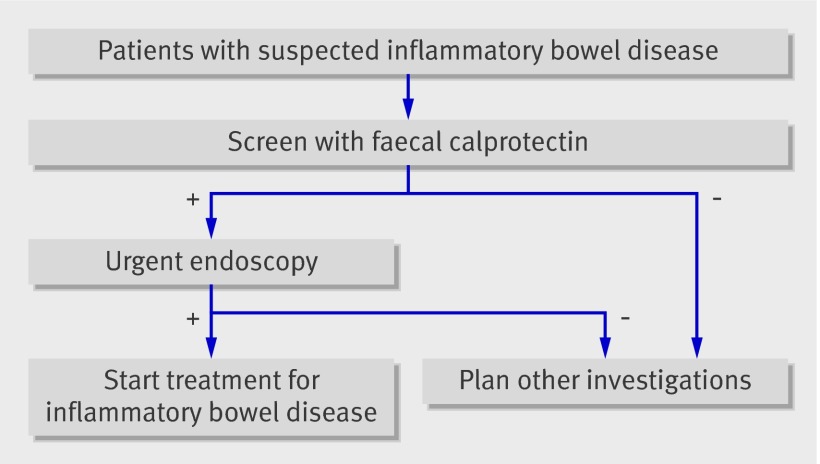

We aimed to determine whether faecal calprotectin can serve as a screening test to reduce the number of people undergoing invasive endoscopy. To move from the evidence gathered in this meta-analysis to a recommendation for a screening strategy we used the comprehensive and transparent GRADE approach.48 Recognising that the diagnostic accuracy of faecal calprotectin is a surrogate for outcomes important to patients is central to this approach. Screening patients by measuring faecal calprotectin levels is of value only if it results in improved outcomes for patients. For this reason we infer the effect of faecal calprotectin screening on patient outcome from the pooled sensitivity and specificity. Key questions are whether the numbers of false negatives (missed cases) and false positives (cases without inflammatory bowel disease who go on to have endoscopy) are acceptable when faecal calprotectin is introduced as a screening test. In the “new” diagnostic pathway patients only with suspected inflammatory bowel disease and an abnormal faecal calprotectin result will be sent urgently for endoscopy (fig 6). Table 3 shows the implications of the testing scenarios. In a hypothetical population of 100 adults with suspected inflammatory bowel disease (and an overall mean prevalence of 32%) three patients without the disease would go on to have endoscopy and two patients with the disease would be missed. Faecal calprotectin screening would reduce the number of adults requiring endoscopy by 67%. In a hypothetical population of 100 children and teenagers with suspected inflammatory bowel disease (and an overall mean prevalence of 61%) nine without the disease would go on to have endoscopy, five with the disease would be missed, and faecal calprotectin screening would reduce the number requiring endoscopy by 35%.

Fig 6 Recommended position of faecal calprotectin in diagnostic pathway

Table 3.

Consequences of pooled sensitivity and specificity of faecal calprotectin for patient outcome

| Test result | No per 100 patients (prevalence of IBD) | Presumed influence on patient outcome | Importance* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults (32%) | Children and teenagers (61%) | |||

| True positive | 30 | 56 | Benefit from shorter delay and early treatment | 8 |

| True negative | 65 | 30 | Benefit from reassurance and avoidance of unnecessary invasive procedure | 8 |

| False positive | 3 | 9 | Detriment from exposure to invasive procedure; may benefit from endoscopy for correct diagnosis | 7 |

| False negative | 2 | 5 | Detriment from delayed diagnosis | 9 |

| Complications | — | — | Not reliably reported | 5 |

| Cost | — | — | No data available | 3 |

IBD=inflammatory bowel disease.

*GRADE recommends classifying patient important outcomes on a 9 point scale: 7-9: critical for decision making; 4-6: important but not critical for decision making; and 1-3: of lower importance to patients.109

The clinical consequences of missing patients with inflammatory bowel disease should be balanced against patients without the disease who go on to have endoscopy. A false negative faecal calprotectin test result would lead to a failure to introduce effective treatment in a timely manner, with the resultant continuation of symptoms. A false positive test result means that people endure an invasive procedure. A considerable proportion of the patients with a false positive test result will, however, prove to have a gastrointestinal condition different from inflammatory bowel disease (table 4) for which endoscopy is inevitable. Complications of endoscopy, related to the invasiveness of the procedure itself (colonic perforation or tear) or to anaesthesia, are also important considerations, although they are rare. Several retrospective studies have reported the incidence of a small perforation after colonoscopy to be in the range 0.032% (1 in 3115 patients) to 0.9% (1 in 111).49 50 51

Table 4.

Causes of abnormal results for faecal calprotectin other than inflammatory bowel disease

| Condition | References |

|---|---|

| Infections: | |

| Giardia lamblia | 100 |

| Bacterial dysentery | 15;30;35;76;78;87;93;100 |

| Viral gastroenteritis | 35;101 |

| Helicobacter pylori gastritis | 24 |

| Malignancies: | |

| Colorectal cancer | 8;25;28-30;44;82;102 |

| Gastric carcinoma | 44 |

| Intestinal lymphoma | 28 |

| Drugs: | |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | 76;82;100;103 |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 104 |

| Food allergy (untreated) | 14;18;27;76 |

| Other gastrointestinal diseases: | |

| Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease | 24;78 |

| Cystic fibrosis | 87;105 |

| Coeliac disease (untreated) | 27;76;78;82;100 |

| Diverticular disease | 18;25;27;29;44;100 |

| Protein losing enteropathy | 76 |

| Colorectal adenoma | 18;25;29;30 |

| Juvenile polyp | 16;17;87 |

| Autoimmune enteropathy | 99 |

| Microscopic colitis | 18;25;106 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 107 |

| Young age (<5 years) | 47;91;108 |

We consider faecal calprotectin a useful screening tool for identifying those patients who are most likely to need endoscopy for inflammatory bowel disease. Adding calprotectin testing to the diagnostic pathway, however, also resulted in delayed diagnosis in 6% (2 in 32 patients) of the adults and 8% (5 in 61) of the children and teenagers. Health professionals may be interested in finding ways to ease the pressure on overstretched endoscopy centres with long waiting lists. Increased faecal calprotectin levels may indicate a need for urgent endoscopy, whereas normal calprotectin levels are less likely to be associated with intestinal inflammation and further investigations can be tailored appropriately. The only exception to this rule is the presence of persistent rectal bleeding, which would justify urgency for endoscopy comparable to that for increased levels of faecal calprotectin.

Comparison with other reviews

A total of 22 narrative reviews have been published in recent years on the use of testing for faecal calprotectin levels in the diagnosis of intestinal inflammation or flare-up of inflammatory bowel disease (fig 1), but all were based on non-systematic methods.52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 One systematic approach summarised the findings of all available studies to 2006.74 The reviewers found higher sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease than we did. The meta-analysis of that review, however, had several methodological limitations. Sensitivity and specificity were pooled separately contrary to general recommendations and the reviewers included studies that featured a control group with healthy people, which leads to overestimation of diagnostic accuracy.75

Methodological limitations of the review

We reviewed the diagnostic accuracy of faecal calprotectin levels according to the most recent insights and methods for diagnostic meta-analyses. The results can, however, be biased by the use of the reference standard. Although we included studies that used endoscopy with histopathological verification of segmental biopsies, we included two studies in adults that did not sample intestinal mucosa.18 25 It is possible that some patients were misclassified because of a normal macroscopic appearance of the mucosa, whereas microscopic evaluation would have shown abnormalities typical of the disease. However, even ileocolonoscopy combined with histology is not an ideal method. The gastrointestinal tract can only be partly visualised with conventional endoscopy. The reported pooled sensitivity of faecal calprotectin could thus be slightly overestimated.

We tried to reduce spectrum bias by including only studies with a patient population representative of patients seen in usual clinical care. None of the studies used a well defined set of clinical findings (clinical prediction rules) or flow chart that identifies patients with a high probability of inflammatory bowel disease.

Because of the limited number of studies included in this meta-analysis we were not able to assess the diagnostic accuracy of faecal calprotectin at different cut-off values. Most of the included studies used the cut-off as advised by the manufacturer (50 μg/g).16 17 19 20 21 22 24 Others based the cut-off on their own receiver operating characteristic curves,23 25 or on the 95th centile of the normal range in children and teenagers.14 15

We could not control for time between calprotectin testing and the reference standard. Ideally faecal sampling was done shortly before endoscopy, but a delay of up to one month was not considered problematic. One study in children and teenagers did not meet this requirement, with over 50% of the faeces samples being collected up to three months after endoscopy.17

We suspected a possible overlap of two patient cohorts described by one research group,21 22 and therefore contacted the authors by email. They replied that there was no overlap of the two patient cohorts as these were different study protocols. Each of them had been approved by the local institutional review board.

Finally, we restricted our search to studies published in English only. This could have been a potential source of bias.

Applicability of findings to primary care practice

The value of faecal calprotectin for screening of patients with suspected inflammatory bowel disease was evaluated in tertiary care facilities, with the exception of one secondary level hospital.19 The Fagan plot (fig 5) presents the predictive values corresponding to the prevalences in this tertiary level context. The plot readily facilitates reading off predictive values corresponding to a lower prevalence in primary care. For example, on decreasing the prevalence (pretest probability) in adults from 32% to 5%, the positive predictive value of the faecal calprotectin test decreases to about 55% whereas the negative predictive value increases above 99.8%. (This assumes that likelihood ratios remain constant across the spectrum of care.) The emphasis in tertiary care is usually on “ruling in”: increasing the probability of inflammatory bowel disease to carry out more expensive, time consuming, and invasive procedures; establish a firm diagnosis; and start appropriate treatment. At tertiary care level a diagnostic test with a high positive likelihood ratio is preferred. In primary care, where the prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease is low, the emphasis is on “ruling out”: lowering the probability of the target disease to provide reassurance, or to adopt a “watchful waiting” strategy. In these instances tests with a low negative likelihood ratio are preferred. In view of the above we are reserved about the utility of faecal calprotectin in primary care practice, and we certainly discourage its use to screen asymptomatic patients.

Conclusions

Measuring faecal calprotectin levels is a useful screening tool for identifying patients who are most likely to need endoscopy for suspected inflammatory bowel disease. The discriminative power to safely exclude the disease (specificity) is significantly better in studies of adults than in studies of children and teenagers. At a tertiary care level faecal calprotectin levels can contribute important information and guide patient management. The pooled sensitivity and specificity, however, should be interpreted with caution. Despite a strict selection of studies based on proper patient recruitment and study design, heterogeneity was considerable.

What is already known on this topic

Diagnosing inflammatory bowel disease requires invasive and time consuming endoscopy

In a relatively large proportion of patients with suspected inflammatory bowel disease the results of endoscopy are negative

Faecal calprotectin is a sensitive marker of intestinal inflammation yet its diagnostic accuracy in a group of patients with suspected inflammatory bowel disease is largely unknown

What this study adds

An increased faecal calprotectin level identifies patients who are most likely to have inflammatory bowel disease and justifies urgency for endoscopy

Use of faecal calprotectin as screening test reduces the number of endoscopies with negative results in both adults and young with suspected inflammatory bowel disease

The test delays diagnosis in a small proportion of patients

We thank S van der Werf (medical librarian, University Medical Center, Groningen) for help with the design of the optimal search strategy for Medline and Embase.

Contributors: PFvR and EVdV conceived and designed the study; acquired, analysed, and interpreted the data; and drafted the manuscript. VF analysed and interpreted the data, provided statistical expertise, and critically revised the manuscript. All authors had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: This review received no funding.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that: (1) they did not receive financial support for the submitted work; (2) they have no relationships with companies that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; (3) their spouses, partners, or children have no financial relationships that may be relevant to the submitted work; and (4) they have no non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2010;341:c3369

References

- 1.Benchimol EI, Guttmann A, Griffiths AM, Rabeneck L, Mack DR, Brill H, et al. Increasing incidence of paediatric inflammatory bowel disease in Ontario, Canada: evidence from health administrative data. Gut 2009;58:1490-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gismera CS, Aladren BS. Inflammatory bowel diseases: a disease(s) of modern times? Is incidence still increasing? World J Gastroenterol 2008;14:5491-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.IBD Working Group of the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. Inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents: recommendations for diagnosis—the Porto criteria. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2005;41:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stange EF, Travis SP, Vermeire S, Beglinger C, Kupcinkas L, Geboes K, et al. European evidence based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: definitions and diagnosis. Gut 2006;55(suppl 1):i1-15S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ristvedt SL, McFarland EG, Weinstock LB, Thyssen EP. Patient preferences for CT colonography, conventional colonoscopy, and bowel preparation. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:578-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lasson A, Kilander A, Stotzer PO. Diagnostic yield of colonoscopy based on symptoms. Scand J Gastroenterol 2008;43:356-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roseth AG, Schmidt PN, Fagerhol MK. Correlation between faecal excretion of indium-111-labelled granulocytes and calprotectin, a granulocyte marker protein, in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 1999;34:50-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roseth AG, Fagerhol MK, Aadland E, Schjonsby H. Assessment of the neutrophil dominating protein calprotectin in feces. A methodologic study. Scand J Gastroenterol 1992;27:793-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whiting P, Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, Bossuyt PM, Kleijnen J. The development of QUADAS: a tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2003;3:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whiting P, Harbord R, Kleijnen J. No role for quality scores in systematic reviews of diagnostic accuracy studies. BMC Med Res Methodol 2005;5:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harbord RM, Deeks JJ, Egger M, Whiting P, Sterne JA. A unification of models for meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy studies. Biostatistics 2007;8:239-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chappell FM, Raab GM, Wardlaw JM. When are summary ROC curves appropriate for diagnostic meta-analyses? Stat Med 2009;28:2653-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashorn S, Honkanen T, Kolho KL, Ashorn M, Valineva T, Wei B, et al. Fecal calprotectin levels and serological responses to microbial antigens among children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009;15:199-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bunn SK, Bisset WM, Main MJ, Gray ES, Olson S, Golden BE. Fecal calprotectin: validation as a noninvasive measure of bowel inflammation in childhood inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2001;33:14-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canani RB, de Horatio LT, Terrin G, Romano MT, Miele E, Staiano A, et al. Combined use of noninvasive tests is useful in the initial diagnostic approach to a child with suspected inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2006;42:9-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fagerberg UL, Loof L, Myrdal U, Hansson LO, Finkel Y. Colorectal inflammation is well predicted by fecal calprotectin in children with gastrointestinal symptoms. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2005;40:450-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kolho KL, Raivio T, Lindahl H, Savilahti E. Fecal calprotectin remains high during glucocorticoid therapy in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 2006;41:720-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Limburg PJ, Ahlquist DA, Sandborn WJ, Mahoney DW, Devens ME, Harrington JJ, et al. Fecal calprotectin levels predict colorectal inflammation among patients with chronic diarrhea referred for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:2831-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Otten CM, Kok L, Witteman BJ, Baumgarten R, Kampman E, Moons KG, et al. Diagnostic performance of rapid tests for detection of fecal calprotectin and lactoferrin and their ability to discriminate inflammatory from irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Chem Lab Med 2008;46:1275-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perminow G, Brackmann S, Lyckander LG, Franke A, Borthne A, Rydning A, et al. A characterization in childhood inflammatory bowel disease, a new population-based inception cohort from south-eastern Norway, 2005-07, showing increased incidence in Crohn’s disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 2009;44:446-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schoepfer AM, Trummler M, Seeholzer P, Criblez DH, Seibold F. Accuracy of four fecal assays in the diagnosis of colitis. Dis Colon Rectum 2007;50:1697-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schoepfer AM, Trummler M, Seeholzer P, Seibold-Schmid B, Seibold F. Discriminating IBD from IBS: comparison of the test performance of fecal markers, blood leukocytes, CRP, and IBD antibodies. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008;14:32-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schroder O, Naumann M, Shastri Y, Povse N, Stein J. Prospective evaluation of faecal neutrophil-derived proteins in identifying intestinal inflammation: combination of parameters does not improve diagnostic accuracy of calprotectin. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007;26:1035-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sidler MA, Leach ST, Day AS. Fecal S100A12 and fecal calprotectin as noninvasive markers for inflammatory bowel disease in children. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008;14:359-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tibble J, Teahon K, Thjodleifsson B, Roseth A, Sigthorsson G, Bridger S, et al. A simple method for assessing intestinal inflammation in Crohn’s disease. Gut 2000;47:506-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Canani RB, Terrin G, Rapacciuolo L, Miele E, Siani MC, Puzone C, et al. Faecal calprotectin as reliable non-invasive marker to assess the severity of mucosal inflammation in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis 2008;40:547-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carroccio A, Iacono G, Cottone M, Di Prima L, Cartabellotta F, Cavataio F, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of fecal calprotectin assay in distinguishing organic causes of chronic diarrhea from irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective study in adults and children. Clin Chem 2003;49:861-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Costa F, Mumolo MG, Bellini M, Romano MR, Ceccarelli L, Arpe P, et al. Role of faecal calprotectin as non-invasive marker of intestinal inflammation. Dig Liver Dis 2003;35:642-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.D’Inca R, Dal Pont E, Di Leo V, Ferronato A, Fries W, Vettorato MG, et al. Calprotectin and lactoferrin in the assessment of intestinal inflammation and organic disease. Int J Colorectal Dis 2007;22:429-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Damms A, Bischoff SC. Validation and clinical significance of a new calprotectin rapid test for the diagnosis of gastrointestinal diseases. Int J Colorectal Dis 2008;23:985-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diamanti A, Colistro F, Basso MS, Papadatou B, Francalanci P, Bracci F, et al. Clinical role of calprotectin assay in determining histological relapses in children affected by inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008;14:1229-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fagerberg UL, Loof L, Lindholm J, Hansson LO, Finkel Y. Fecal calprotectin: a quantitative marker of colonic inflammation in children with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2007;45:414-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jeffery J, Lewis SJ, Ayling RM. Fecal dimeric M2-pyruvate kinase (tumor M2-PK) in the differential diagnosis of functional and organic bowel disorders. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009;15:1630-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones J, Loftus EV Jr, Panaccione R, Chen LS, Peterson S, McConnell J, et al. Relationships between disease activity and serum and fecal biomarkers in patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;6:1218-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaiser T, Langhorst J, Wittkowski H, Becker K, Friedrich AW, Rueffer A, et al. Faecal S100A12 as a non-invasive marker distinguishing inflammatory bowel disease from irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 2007;56:1706-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langhorst J, Elsenbruch S, Koelzer J, Rueffer A, Michalsen A, Dobos GJ. Noninvasive markers in the assessment of intestinal inflammation in inflammatory bowel diseases: performance of fecal lactoferrin, calprotectin, and PMN-elastase, CRP, and clinical indices. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:162-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quail MA, Russell RK, Van Limbergen JE, Rogers P, Drummond HE, Wilson DC, et al. Fecal calprotectin complements routine laboratory investigations in diagnosing childhood inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009;15:756-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schoepfer AM, Beglinger C, Straumann A, Trummler M, Renzulli P, Seibold F. Ulcerative colitis: correlation of the Rachmilewitz endoscopic activity index with fecal calprotectin, clinical activity, c-reactive protein, and blood leukocytes. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009;15:1851-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shitrit AB, Braverman D, Stankiewics H, Shitrit D, Peled N, Paz K. Fecal calprotectin as a predictor of abnormal colonic histology. Dis Colon Rectum 2007;50:2188-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silberer H, Kuppers B, Mickisch O, Baniewicz W, Drescher M, Traber L, et al. Fecal leukocyte proteins in inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Lab 2005;51:117-26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sipponen T, Karkkainen P, Savilahti E, Kolho KL, Nuutinen H, Turunen U, et al. Correlation of faecal calprotectin and lactoferrin with an endoscopic score for Crohn’s disease and histological findings. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008;28:1221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sipponen T, Savilahti E, Karkkainen P, Kolho KL, Nuutinen H, Turunen U, et al. Fecal calprotectin, lactoferrin, and endoscopic disease activity in monitoring anti-TNF-alpha therapy for Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008;14:1392-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sipponen T, Savilahti E, Kolho KL, Nuutinen H, Turunen U, Farkkila M. Crohn’s disease activity assessed by fecal calprotectin and lactoferrin: correlation with Crohn’s disease activity index and endoscopic findings. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008;14:40-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Summerton CB, Longlands MG, Wiener K, Shreeve DR. Faecal calprotectin: a marker of inflammation throughout the intestinal tract. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002;14:841-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wagner M, Peterson CG, Ridefelt P, Sangfelt P, Carlson M. Fecal markers of inflammation used as surrogate markers for treatment outcome in relapsing inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2008;14:5584-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spiller R, Aziz Q, Creed F, Emmanuel A, Houghton L, Hungin P, et al. Guidelines on the irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms and practical management. Gut 2007;56:1770-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Olafsdottir E, Aksnes L, Fluge G, Berstad A. Faecal calprotectin levels in infants with infantile colic, healthy infants, children with inflammatory bowel disease, children with recurrent abdominal pain and healthy children. Acta Paediatr 2002;91:45-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schunemann HJ, Oxman AD, Brozek J, Glasziou P, Jaeschke R, Vist GE, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ 2008;336:1106-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Araghizadeh FY, Timmcke AE, Opelka FG, Hicks TC, Beck DE. Colonoscopic perforations. Dis Colon Rectum 2001;44:713-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cobb WS, Heniford BT, Sigmon LB, Hasan R, Simms C, Kercher KW, et al. Colonoscopic perforations: incidence, management, and outcomes. Am Surg 2004;70:750-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Damore LJ, Rantis PC, Vernava AM III, Longo WE. Colonoscopic perforations. Etiology, diagnosis, and management. Dis Colon Rectum 1996;39:1308-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ali S, Tamboli CP. Advances in epidemiology and diagnosis of inflammatory bowel diseases. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2008;10:576-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Angriman I, Scarpa M, D’Inca R, Basso D, Ruffolo C, Polese L, et al. Enzymes in feces: useful markers of chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Chim Acta 2007;381:63-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arnott ID, Watts D, Ghosh S. Review article: is clinical remission the optimum therapeutic goal in the treatment of Crohn’s disease? Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002;16:857-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Desai D, Faubion WA, Sandborn WJ. Review article: biological activity markers in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007;25:247-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Foell D, Wittkowski H, Roth J. Monitoring disease activity by stool analyses: from occult blood to molecular markers of intestinal inflammation and damage. Gut 2009;58:859-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gearry R, Barclay M, Florkowski C, George P, Walmsley T. Faecal calprotectin: the case for a novel non-invasive way of assessing intestinal inflammation. NZ Med J 2005;118:U1444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gisbert JP, McNicholl AG. Questions and answers on the role of faecal calprotectin as a biological marker in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis 2009;41:56-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gisbert JP, McNicholl AG, Gomollon F. Questions and answers on the role of fecal lactoferrin as a biological marker in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009;15:1746-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hanauer SB, Present DH, Rubin DT. Emerging issues in ulcerative colitis and ulcerative proctitis: individualizing treatment to maximize outcomes. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;5:1-16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kerkhoff C. The S100A8 and S100A9 proteins are attractive targets to modulate inflammation. Antiinflamm Anti-Allergy Agents 2007;6:244-51. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Konikoff MR, Denson LA. Role of fecal calprotectin as a biomarker of intestinal inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2006;12:524-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Loftus EV Jr. Clinical perspectives in Crohn’s disease. Objective measures of disease activity: alternatives to symptom indices. Rev Gastroenterol Disord 2007;7(suppl 2):8-16S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lundberg JO, Hellstrom PM, Fagerhol MK, Weitzberg E, Roseth AG. Technology insight: calprotectin, lactoferrin and nitric oxide as novel markers of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;2:96-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marteau P, Daniel F, Seksik P, Jian R. Inflammatory bowel disease: what is new? Endoscopy 2004;36:130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Minderhoud IM, Samsom M, Oldenburg B. What predicts mucosal inflammation in Crohn’s disease patients? Inflammatory Bowel Dis 2007;13:1567-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pallone F. Updates on diagnosis: new tools? How can we measure activity? Dig Liver Dis Suppl 2008;2:5-6. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pardi DS, Sandborn WJ. Predicting relapse in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: what is the role of biomarkers? Gut 2005;54:321-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sostegni R, Daperno M, Scaglione N, Lavagna A, Rocca R, Pera A. Review article: Crohn’s disease: monitoring disease activity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003;17(suppl 2):11-7S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sutherland AD, Gearry RB, Frizelle FA. Review of fecal biomarkers in inflammatory bowel disease. Dis Colon Rectum 2008;51:1283-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tibble JA, Bjarnason I. Non-invasive investigation of inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2001;7:460-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tibble JA, Bjarnason I. Fecal calprotectin as an index of intestinal inflammation. Drugs Today 2001;37:85-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vermeire S, Van Assche G, Rutgeerts P. Laboratory markers in IBD: useful, magic, or unnecessary toys? Gut 2006;55:426-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Von Roon AC, Karamountzos L, Purkayastha S, Reese GE, Darzi AW, Teare JP, et al. Diagnostic precision of fecal calprotectin for inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal malignancy. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:803-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Knottnerus JA, Buntinx FE. The evidence base of clinical diagnosis. 2nd ed. Blackwell, 2009.

- 76.Bremner A, Roked S, Robinson R, Phillips I, Beattie M. Faecal calprotectin in children with chronic gastrointestinal symptoms. Acta Paediatr 2005;94:1855-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bunn SK, Bisset WM, Main MJ, Golden BE. Fecal calprotectin as a measure of disease activity in childhood inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2001;32:171-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Canani RB, Rapacciuolo L, Romano MT, Tanturri de Horatio L, Terrin G, Manguso F, et al. Diagnostic value of faecal calprotectin in paediatric gastroenterology clinical practice. Dig Liver Dis 2004;36:467-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Casellas F, Borruel N, Torrejon A, Varela E, Antolin M, Guarner F, et al. Oral oligofructose-enriched inulin supplementation in acute ulcerative colitis is well tolerated and associated with lowered faecal calprotectin. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007;25:1061-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Costa F, Mumolo MG, Ceccarelli L, Bellini M, Romano MR, Sterpi C, et al. Calprotectin is a stronger predictive marker of relapse in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn’s disease. Gut 2005;54:364-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.D’Inca R, Dal Pont E, Di Leo V, Benazzato L, Martinato M, Lamboglia F, et al. Can calprotectin predict relapse risk in inflammatory bowel disease? Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:2007-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dolwani S, Metzner M, Wassell JJ, Yong A, Hawthorne AB. Diagnostic accuracy of faecal calprotectin estimation in prediction of abnormal small bowel radiology. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;20:615-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Eder P, Stawczyk-Eder K, Krela-Kazmierczak I, Linke K. Clinical utility of the assessment of fecal calprotectin in Lesniowski-Crohn’s disease. Pol Arch Med Wewn 2008;118:622-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gaya DR, Lyon TD, Duncan A, Neilly JB, Han S, Howell J, et al. Faecal calprotectin in the assessment of Crohn’s disease activity. Q J Med 2005;98:435-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gisbert JP, Bermejo F, Perez-Calle JL, Taxonera C, Vera I, McNicholl AG, et al. Fecal calprotectin and lactoferrin for the prediction of inflammatory bowel disease relapse. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009;15:1190-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ho GT, Lee HM, Brydon G, Ting T, Hare N, Drummond H, et al. Fecal calprotectin predicts the clinical course of acute severe ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:673-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Joishy M, Davies I, Ahmed M, Wassel J, Davies K, Sayers A, et al. Fecal calprotectin and lactoferrin as noninvasive markers of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2009;48:48-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kallel L, Ayadi I, Matri S, Fekih M, Mahmoud NB, Feki M, et al. Fecal calprotectin is a predictive marker of relapse in Crohn’s disease involving the colon: a prospective study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;22:340-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Langhorst J, Elsenbruch S, Mueller T, Rueffer A, Spahn G, Michalsen A, et al. Comparison of 4 neutrophil-derived proteins in feces as indicators of disease activity in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2005;11:1085-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Reinders CA, Jonkers D, Janson EA, Stockbrugger RW, Stobberingh EE, Hellstrom PM, et al. Rectal nitric oxide and fecal calprotectin in inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 2007;42:1151-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rugtveit J, Fagerhol MK. Age-dependent variations in fecal calprotectin concentrations in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2002;34:323-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Scarpa M, D’Inca R, Basso D, Ruffolo C, Polese L, Bertin E, et al. Fecal lactoferrin and calprotectin after ileocolonic resection for Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum 2007;50:861-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shastri YM, Bergis D, Povse N, Schafer V, Shastri S, Weindel M, et al. Prospective multicenter study evaluating fecal calprotectin in adult acute bacterial diarrhea. Am J Med 2008;121:1099-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shastri YM, Povse N, Stein J. A prospective comparative study for new rapid bedside fecal calprotectin test with an established ELISA to assess intestinal inflammation. Clin Lab 2009;55:53-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tibble JA, Sigthorsson G, Bridger S, Fagerhol MK, Bjarnason I. Surrogate markers of intestinal inflammation are predictive of relapse in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2000;119:15-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Walkiewicz D, Werlin SL, Fish D, Scanlon M, Hanaway P, Kugathasan S. Fecal calprotectin is useful in predicting disease relapse in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008;14:669-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wassell J, Dolwani S, Metzner M, Losty H, Hawthorne A. Faecal calprotectin: a new marker for Crohn’s disease? Ann Clin Biochem 2004;41:230-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Xiang JY, Ouyang Q, Li GD, Xiao NP. Clinical value of fecal calprotectin in determining disease activity of ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol 2008;14:53-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kapel N, Roman C, Caldari D, Sieprath F, Canioni D, Khalfoun Y, et al. Fecal tumor necrosis factor-alpha and calprotectin as differential diagnostic markers for severe diarrhea of small infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2005;41:396-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tibble JA, Sigthorsson G, Foster R, Forgacs I, Bjarnason I. Use of surrogate markers of inflammation and Rome criteria to distinguish organic from nonorganic intestinal disease. Gastroenterology 2002;123:450-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Canani RB, Passaro M, Puzone C. Diagnostic value of faecal calprotectin in paediatric age. Medico e Bambino 2009;28:239-42. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Aadland E, Fagerhol MK. Faecal calprotectin: a marker of inflammation throughout the intestinal tract. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002;14:823-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tibble JA, Sigthorsson G, Foster R, Scott D, Fagerhol MK, Roseth A, et al. High prevalence of NSAID enteropathy as shown by a simple faecal test. Gut 1999;45:362-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Poullis A, Foster R, Mendall MA, Shreeve D, Wiener K. Proton pump inhibitors are associated with elevation of faecal calprotectin and may affect specificity. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003;15:573-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bruzzese E, Raia V, Gaudiello G, Polito G, Buccigrossi V, Formicola V, et al. Intestinal inflammation is a frequent feature of cystic fibrosis and is reduced by probiotic administration. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;20:813-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wildt S, Nordgaard-Lassen I, Bendtsen F, Rumessen JJ. Metabolic and inflammatory faecal markers in collagenous colitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;19:567-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yagmur E, Schnyder B, Scholten D, Schirin-Sokhan R, Koch A, Winograd R, et al. [Elevated concentrations of fecal calprotectin in patients with liver cirrhosis.] Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2006;131:1930-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Nissen AC, van Gils CE, Menheere PP, Van den Neucker AM, van der Hoeven MA, Forget PP. Fecal calprotectin in healthy term and preterm infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2004;38:107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Vist GE, Falck-Ytter Y, Schunemann HJ, et al. What is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ 2008;336:995-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]