Abstract

Objective

To describe the state of the literature on stigma associated with children’s mental disorders and highlight gaps in empirical work.

Method

We reviewed child mental illness stigma articles in (English only) peer-reviewed journals available through Medline and PsychInfo. We augmented these with adult-oriented stigma articles that focus on theory and measurement. 145 articles in PsychInfo and 77 articles in MEDLINE met search criteria. The review process involved identifying and appraising literature convergence on the definition of critical dimensions of stigma, antecedents, and outcomes reported in empirical studies.

Results

We found concurrence on three dimensions of stigma (negative stereotypes, devaluation and discrimination), two contexts of stigma (self, general public), and two targets of stigma (self/individual, family). Theory and empirics on institutional and self stigma in child populations were sparse. Literature reports few theoretic frameworks and conceptualizations of child mental illness stigma. One model of help-seeking (the FINIS) explicitly acknowledges the role of stigma in children’s access and utilization of mental health services.

Conclusions

Compared to adults, children are subject to unique stigmatizing contexts that have not been adequately studied. The field needs conceptual frameworks that get closer to stigma experiences that are causally linked to how parents/caregivers cope with children’s emotional and behavioral problems such as seeking professional help. To further research in child mental illness, we suggest an approach to adapting current theoretical frameworks and operationalizing stigma highlighting three dimensions of stigma, three contexts of stigma (including institutions), and three targets of stigma (self/child, family and services).

Keywords: Stigma, Child mental disorders, Conceptual framework, Caregiver help-seeking

Introduction

Stigma has been identified as a likely key factor in mental health services access and utilization, particularly under-utilization of existing services by some segments of society, most notably minority racial/ethnic children.1–3 In child mental health services research, the role of stigma has not been well-conceptualized though it is presumed to be significant. Literature on caregiver strain and burden of care has explored processes and implications of coping with children’s emotional and behavioral disorders.4 Although considering perceptions (including concerns about public attitudes) and acknowledging the social implications of childhood mental disorders, caregiver strain and burden of care literature has not adequately considered the implications of public stigma. Few stigma researchers address child mental illness.5, 6 Therefore, the field lacks suitable and empirically tested theoretic frameworks and conceptualizations. Particularly, lacking are conceptual frameworks addressing help-seeking that adequately account for the role of stigma among barriers to care7 or caregiver strain variables.4 Our premise is that the field needs conceptual frameworks that link stigma to how parents/family caregivers cope with children’s emotional and behavioral problems such as seeking professional help.

One way parents/family caregivers cope with children’s mental health problems is to seek mental health services.8 Hence, stigma likely compounds the burden of care and affects caregiver’s help-seeking behavior. For example, caregiver strain literature indicates an association between caregiver depression and child symptomatology.9 Depression has been shown to be related to the under-use of mental health service.10

In this paper we first review the state of the literature on stigma and child mental disorders and highlight gaps in empirical work. Next, we describe a suggested framework for operationalizing the stigma experience in the area of child mental disorders highlighting three constructs: a) dimensions of stigma, b) context of stigma, and c) targets of stigma. This approach is needed for developing measures and increasing the relevance of theoretical models for assessing the relationship between stigma associated with children’s emotional and behavioral problems and caregivers’ help seeking for the child. The framework helps to conceptually link the public and private spheres of child mental disorders – how negative public attitudes might have an impact on parents’ personal responses, strain and care-giving decisions.

Method

We reviewed child mental illness stigma literature in peer-reviewed journals available through MEDLINE and PsychInfo from the earliest through 2008. The search for “mental illness stigma” or “attitudes towards mental illness” and “children” or “adolescents” yielded 145 articles in PsychInfo and 77 articles in MEDLINE (the latter overlapped with those identified through PsychInfo). From these we selected articles that primarily described (1) the theory and empirics of stigma by association with mental disorders in children and adolescents, and (2) children’s and/or family perceptions and experiences of stigma. There were few such articles. Therefore, we augmented these with adult mental illness stigma articles that focus on theory and measurement. We also drew on insights from prejudice literature relevant to this population, particularly the stigmas of race/ethnicity, non-heterosexual sexual orientation, HIV/AIDS, neighborhood identification and socio-economic status. We searched for empirics on interactions between mental disorders and some of these stigmas.

Results

The review process involved identifying and appraising literature convergence on the definition of critical dimensions of stigma, antecedents, and outcomes reported in empirical studies.

The Dimensions of Stigma

Though diverse, literature converges on Erving Goffman’s11 definition, in which stigma is an actual/inferred attribute that damages the bearer’s reputation and degrades him/her to a socially discredited status.12–14 Social devaluation and rejection are customary experiences of the stigmatized. Affiliation with the stigmatized confers a secondary stigma – courtesy stigma.11

Extensive literature reviews on the stigma construct and how it is operationalized in adult mental illness research are provided elsewhere.13–18 The stigma construct is generally attributed to Erving Goffman11 and Thomas Scheff.19 These early frameworks have been criticized for presuming that stigma is located entirely in the person,20 a view attributed to focusing research on stigmatizers’ viewpoints and less on the perspective of the stigmatized.13 Modified labeling theory,16 a variant of Scheff’s labeling theory, however, recognizes the socio-cultural context of stigma,13 a social construct that reflects relations of power operating at societal levels.20 Within modified labeling theory, powerful groups in society impose stereotypically negative labels on those they deem undesirable, whom they subsequently devalue and discriminate.20 This conceptualization of stigma corresponds with a social psychology grounded perspective that stigmatization is linked to human cognition via stereotyping and prejudice.14, 15, 21 For example, some studies have observed that clinicians demonstrate ‘unintentional biases’ in their judgment and reactions to patients and their families, despite genuine commitments to providing patient-centered and culturally sensitive care.22 More detailed discussion of the relationship between stigma and prejudice are given elsewhere.18 It suffices, however, to note that literature converges on negative stereotypes (or attitudes), behavioral predispositions such as discrimination and devaluation behavior17 as critical dimensions of stigma.

Stereotypes

Most public stigma studies assess variance in stereotype awareness, in particular, dangerousness, incompetence and disruptiveness stereotypes.23–26 Even though these constructs are of concern to the field of child mental health, few child-focused stigma studies explicitly assess negative stereotypes. For example, dangerousness has been reported in child focused studies. 5, 27 Therefore, we do not know the extent to which there exist other more or less salient stereotypes of child mental disorders than dangerousness, such as those acknowledged in a recent conceptual framework by Pescosolido and her colleagues.17 The dangerousness stereotype might not apply to all stigmatized childhood mental disorders, as observed in adult studies that have compared stereotypes typically applied to schizophrenia vs. depression.28 Identifying negative stereotypes that are particularly salient to these conditions is advantageous for a comprehensive understanding of stigma experiences of children and their caregivers, particularly within widely acknowledged stigma frameworks.16, 17 Literature on adult mental illness and racial/ethnic prejudice provides a broad array of relatable stereotypes and misconceptions, e.g., associating mental illness with minority racial/ethnic status, poverty, unpredictability, character defect or mental retardation.29–32 Therefore, the focus on dangerousness might skew stigma research towards certain mental disorders, particularly those characterized by externalizing problems.33 However, youth in the study reported by Walker and colleagues34 considered other youth with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and depression to be potentially violent and likely to engage in antisocial behavior. Therefore, the salience of the dangerousness stereotype in the stigmatization of mental disorders should not be underrated.

Discrimination and devaluation

According to labeling theory, stigmatization is largely a sequential process that begins with labeling and (negative) stereotyping by others, which leads to separation and status loss (or devaluation) of the labeled entity, and subsequently discrimination.20 Self-stigma theory further postulates that some among the socially devalued and discriminated internalize public stigma by devaluing themselves and deleteriously altering their behavior and attitudes. For example, one might convince her/himself that s/he is unable to work or live independently as a result of the stigma.15 However, not all persons with potentially stigmatized conditions are concerned and negatively impacted by public stigma. A study among a sample of Somali immigrants in Canada raises the counterintuitive possibility of ‘reverse stigmatization’ and ‘counter devaluation’ of stigmatizers by the stigmatized.35 Furthermore, not all people who are concerned about public stigma self-stigmatize. The risk factors for self-stigmatization, in particular, are not adequately explored in adult literature. Although not yet extended to courtesy stigma, it is plausible to presume that while a primary caregiver might agree with generalized negative stereotypes of child mental illness 5 s/he might not apply those stereotypes to her/his child, let alone discriminate against the child. However, negative parental responses to children and their deleterious outcomes are well known. What is missing from the literature, though, are explorations of the relationship between public stigmatization of children and/or parents and parental coping strategies, such as self-stigmatization.

Antecedents of Stigma

Type of condition that elicits stigma

The role of the construct “condition” is included in most of the prominent conceptual frameworks guiding stigma research as a factor that influences public stigma.17, 36 Condition in this case refers to diagnostic labels such as those derived from Diagnostic Statistical Manuals or related diagnostic protocols. Most mental health stigma research explores the extent to which an identification with a diagnostic label (real or imagined) triggers and/or compounds public stigma. Hence the research focus on major mental disorders such as schizophrenia, depression and bipolar disorders associated with adult populations.28, 37, 38 It has been observed, for example, that discriminatory attitudes (‘unintentional biases’ included) among mental health professionals likely vary by patients’ psychiatric conditions; people with drug and substance use disorders and those with schizophrenia being most likely to be regarded as less deserving of interventions than others.39 The hierarchy of worthiness-for-intervention often reflects the degree to which the condition (i.e., its current status or method of contagion) is socially perceived as attributable to personal conduct, e.g., irresponsibility that reflects an underlying character weakness, moral defect, or compromised hygiene standards.

In child-focused stigma research, we know that public stigma is condition specific--i.e., the general public reacts and responds differently according to the mental disorder (label) that the person/child is presumed to have, e.g., depression vs. ADHD in children,34, 40 similar to the distinction in adults between mental illness vs. substance abuse 27 and Bipolar I vs. Bipolar II.37 However, stigmatization tends to persist even when the condition is known to be under control, and/or treatments are known to be effective or unnecessary.40, 41 This partially explains anticipatory aspects of stigma that are signaled by the often reported burden of managing information (or strategic disclosure), particularly about inconspicuous disorders.42

The media has been shown to influence public stigma, particularly reinforcing negative stereotypes and promoting unfounded fear and precautionary responses. Extensive literature reviews on media portrayal of mental illness are available elsewhere.43–45 Although media research is focused largely on adult mental illness, two studies are particularly relevant to children. Slopen and colleagues46 found media coverage of mental illness in adults to be more stigmatizing than that describing children. They observed that media reports on children were more likely to meet criteria for ‘responsible journalism” than reports on adults. Morgan & Jorm47 found an association between what youth in an Australian sample recalled from news stories about mental illness and their attitudes towards mental illness. For example, recall of stories depicting crime and violence was associated with reluctance to disclose one’s mental illness. Youth who recalled news stories about celebrities with mental illness were more likely to view people with mental illness as sick rather than weak. However, both studies note the importance of the media in de-stigmatizing mental illness and influencing constructive public policy.

The Outcomes of Stigma

The outcomes or effects of stigma also form a substantial portion of the research literature. In adult mental health, social withdrawal and secrecy are typically considered outcomes of public stigma awareness.41 However, not all who experience public stigma exhibit these outcomes. The area of self-esteem decrement has begun to be the focus of fruitful and informative modeling and empirical work in recent times.48, 49 One major product of self-stigma research is a social psychology framework, advanced by Corrigan and colleagues,15 describing the internalization of public stigma through stereotype awareness, agreement and concurrence, and how that process might result in self-esteem decrement, and ultimately social withdrawal and secrecy.15, 49, 50 Empirical testing of that framework is ongoing, and partial support for the framework has been reported among adult samples.51, 52 However, the utility of the Corrigan et al. framework for understanding public stigma effects among children with emotion and behavior problems and their caregivers is undetermined.

Outside of a handful of studies 5, 7, 34, 53 little is documented about the stigma related to child mental disorders and the consequences of this stigmatization process. Emerging literature has confirmed negative public attitudes towards mental disorders in children.5, 40 This literature also suggests that the public stigma of child mental illness might be just about as unforgiving as that of adult mental illness.26, 38, 49, 54 For example, we know from this literature that when adults are presented with vignettes of children with emotions and behaviors that the respondents regard as dangerous (or identify as indicating mental illness), they are likely to respond negatively and punitively to the hypothetical child and condition.40 Pescosolido and colleagues40 have found that negative public responses include preference for social distance from the child/family, the distancing of the child from other children, blaming the child’s family for the child’s problems, and preference for severe treatment modalities for the child including treatment in restrictive settings. However, the study found more public support for the coercion of parents of children with asthma than mental health conditions considered.

Applicability of Adult Stigma Research to Children

The dearth of child mental health stigma research34, 40 suggests, among others, a prevailing view that findings from, and conceptual frameworks developed for, adult mental health stigma are transferable to and informative about the stigma of children’s emotional and behavioral health problems. That is, the deleterious effects of stigma observed among actual or potential consumers of adult mental health services-- such as socio-economic exclusion, social withdrawal and secrecy, and reluctance to seek needed help41 –are thought to apply equally to children with emotional and behavioral problems. For example, older adolescents, particularly males, have been found to have similar concerns about stigma consequences on social role expectations as do adult males.55, 56

On the other hand, there is an expressed view that findings from stigma research conducted among adults might not be generalizable to children and adolescents and their families.23, 40, 53 Hinshaw has noted that, unlike adults, children have far less power and are accorded far less social status in most societies and their behavior is more likely to be less tolerated by adults than adult behavior.23 Furthermore, although it is thought that children suffer many of the consequences of stigma directly,34, 55 they rarely seek professional help on their own--parents or other family caregivers act as their agents and, thus, play a unique role that must also be acknowledged and examined. Therefore, the traditional tendency to blame child misconduct on poor parenting,57, 58 compounded by vulnerability of children (including insufficient legal protections) 23 and the role of family caregivers in help-seeking,25, 55, 59 places children and their families under unique stigmatizing contexts, most of which have not been adequately studied.

Major Gaps in the Current Literature

Vignette-based public stigma studies are informative about the cultural context in which people respond to mental health problems.5 These need to be augmented with studies of behavior towards children with mental disorders and their caregivers. We also lack clarity on what makes some people (adults/children/parents) more susceptible to public and self-stigma than others. Furthermore, we do not know the extent to which parents/caregivers stigmatize their own children, particularly young children. Some children/caregivers might be subject to multiple stigmas or hold several socially devalued identities/statuses aside from the mental illness label. For example, an increasing number of children, particularly among racial/ethnic minorities, are cared for by kin foster parents. Regardless of mental health status, being cared for by a biological parent might confer a different social status on a child than being cared for by other types of caregivers. The notion of ‘master’ and ‘secondary’ status is well developed in relation to racial prejudice, disability discrimination and gender inequality. Sex stigma literature has explored potential interactions between internalized homophobia and mental health problems.60, 61 However, it has been noted that literature on mental illness stigma often does not incorporate insight from the prejudice or disparities literature.18, 62 Therefore, we do not know from the literature about the interaction effects of mental illness labels and other socially devalued statuses or which status exerts the gravest stigma on the individual and his/her associates.

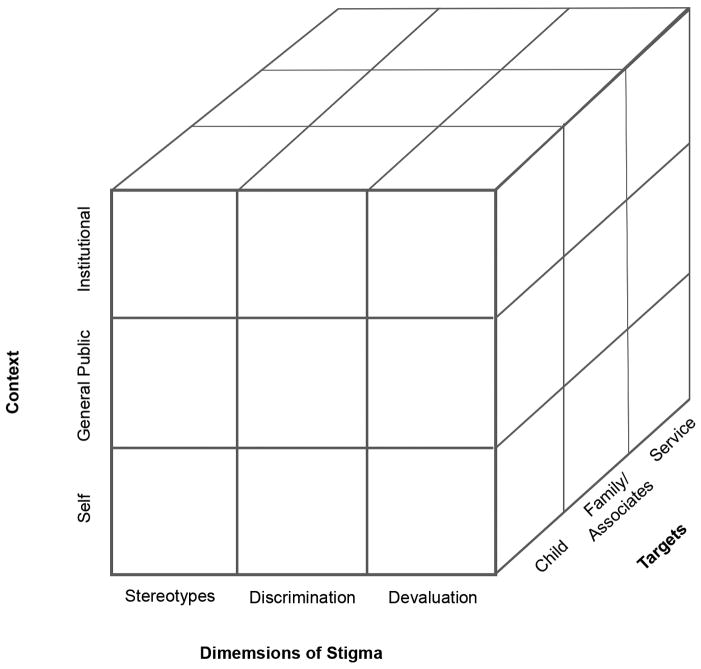

Consequently, the arenas for stigmatization remain unclearly defined, though we have multi-level models for understanding how children and parents cope with child mental disorders by seeking professional healthcare.63–66 From the findings we are concerned that current research and theoretical models are not adequate to address some of the pressing issues regarding stigma in children’s mental health. That, in order to define the “what” (stigma), we need to know “who” does “what” to “whom” - this translates into “context” “dimensions” and “targets” of stigma (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Relationship among child mental disorder stigma dimensions, contexts and targets

A Framework for Operationalizing the Stigma Experience in Child Mental Disorders

Three inter-related constructs kept coming to our attention in their relevance to understanding stigma and its relationship to child mental disorders: a) the dimensions of stigma, described above, b) the context of stigma, or where is the stigmatizing event taking place, and c), the targets or victims of stigma. We noted the dynamic effects of the relationship among the context in which stigma is perceived and experienced (self, institutional, and general public), the different dimensions of stigma acknowledged in stigma literature (negative stereotypes, devaluation, and discrimination), and victims of the stigma (i.e., the child, family associates, and services). We generated a matrix that potentially accounts for twenty seven unique combinations of dimensions and domains of stigma of child mental disorders (see Figure 1). Here we focus on the constructs of stigma context and targets as they could enhance current theory, practice, and research related to stigma in children’s mental health services.

Context of Stigma

Our literature review suggests that most research on stigma has concentrated on the general public as stigmatizers and the child/direct consumer (or their condition) as the target.5, 16, 36 Within the general public context for stigmatization, the focus tends to be on adults’ negative attitudes and behavior towards children and their families. However, some research has also focused on children as stigmatizers,27, 34, 67–69 albeit with mixed findings. The generalizability of findings from these studies is limited, as was noted in an earlier review of youth studies.70

The public as stigmitizers

Some emerging findings about public attitudes towards mental disorders in children suggest the probability for greater stigmatization of younger than older children,40 which seems to contradict conventional attitudes towards children. However, the relationship between child age and attitudes towards child mental disorders might be related more to the stigmatizer than the target of stigma. For example, Taylor and Dean 71 found public attitudes towards mental illness to vary by the life-cycle stage of respondents, i.e., older families (persons with children aged between 6 and 18) had more sympathetic attitudes on each of Taylor & Dean’s four scales (i.e., authoritarianism, benevolence, social restrictiveness and community based mental health ideology) than younger families (persons with children under 6 years). They conclude that this might be due to older families having less concern about people with mental illness and the likelihood of their children coming into contact with them than younger families.

The self as stigmatizer

Self-stigmatization by the person with the disorder has also been the subject of recent research and publications in adult mental health,15, 49, 50, 72, 73 but few such studies have involved children/young adolescents. Similarly, self-stigmatization by the parent/family caregiver of the child/adult with the condition has not been adequately conceptualized and/or empirically demonstrated. Some emerging research explores potential self-stigmatization by children and their primary caregivers.34

The intersection of the ‘self’ arena of stigmatization and ‘child’ as target for stigmatization in Figure 1 raises both conceptual and methodological questions that have not been adequately explored. We know that young school-age children can have negative perceptions of mental illness 34, 70 and that older adolescents might not differ from adults in their responses to their own or others’ mental illness.27, 67–69 What we do not know, and we need to investigate, is the stage in children’s development when self-stigmatization might begin to occur. Stigma frameworks need to cater for the probability that children will be stigmatized although not mature enough to pick-up such cues from their environment or interpret them as such. On the other hand, a parent/caregiver might perceive the stigma being directed at the child and respond to it in ways that have implications on the child’s access and use of services.

Theoretically, mental disorder is separate (or separable) from the child/self.72 Some anti-stigma interventions endeavor to ensure that the general public appreciates the distinction.25, 39 Therefore, it is plausible to anticipate a situation in which the disorder but not the child or his/her parent/family is stigmatized. The disorder reflects deviance from some normal state. Separating the disorder from the disordered is premised on the view that the disorder blemishes the child; as in biomedical literature, the disorder is an assault on the otherwise normal body. This also augers with lay views of the young child as an angel, pure and without blemish but vulnerable to external forces. Young children are, therefore, assumed to be less responsible for their way of being and its related outcomes than older children and adults.65 However, somewhere along the developmental trajectory from childhood into adolescence and adulthood the distinction of ‘person/self’ from ‘condition’ becomes blurred in the public mind. The condition might then assume a central place in the definition (or characterization) of the person/self. Thus the stigma towards the condition likely becomes synonymous with the stigma towards the child. This also might affect the stigma directed at the child’s parent/family, to the extent that the assignment of blame might be linked to the developmental stage of the child.

The distinction between ‘self’ and ‘condition’ might also have implications on parents’ (and children’s) beliefs about the legitimacy of public stigma, a key factor in the self-stigma model. Variance in the perceived legitimacy of public stigma has been hypothesized to explain variance in the tendency to internalize public stigma and in self-esteem/efficacy decrement among adult mental health consumers.52 Emerging findings by Watson and colleagues52 support the view that adults with mental illness who view public stigma as legitimate are at risk of internalizing public stigma and experiencing decrement in self-esteem/efficacy. Strong views that public stigma is illegitimate predict involvement in anti-stigma initiatives and seeking professional mental health services. The likelihood of such outcomes occurring among young children and/or their parents has implications for those who rely on behavioral models of service access and utilization64, 66 to examine patterns in child mental health services use.

Institutions and service providers as stigmatizers

The institutional context for the stigmatization of the direct consumer has also been explored in a number of reported studies.74, 75 Most institutional stigma research has focused on individual service providers, i.e., psychiatric and primary physicians, psychologists, other healthcare professionals--as stigmatizers rather than the institutions themselves (and decision processes therein) as stigmatizers.76 Among child focused studies, the stigmatizing attitudes of primary health care providers such as pediatricians are not widely explored, though utilization of primary care services is extensively reported in child mental health literature.77, 78 The school setting as a context for stigmatization is also explored, in particular family views of teachers’ attitudes.34, 67 It has been acknowledged, though not empirically verified, that the institutional context for stigmatization goes far beyond attitudes of professionals in direct contact with consumers and their associates but is reflected also in policies and practices of public institutions that result in the devaluation and discrimination of participants in the mental health sector.13, 75, 79 Examples might include policies and practices that result in lack of parity between physical and mental health, and the critical shortage of mental health professionals (perhaps linked to disparities in the attractiveness of careers in mental vs. physical healthcare).80

Targets of Stigma

The stigma literature available for both adult and child populations have concentrated almost exclusively on stigma towards the person with the condition (i.e., the child with the mental disorder). However, we also highlight two other targets that appear to be relevant and critical to understanding the experience of stigma, particularly in the area of child mental disorders: stigma by association towards family members, and stigma related to the use of mental health services.

Stigma by association with child mental disorders

Literature on caregivers’ perspectives on stigma focuses on family caregivers of adults with mental disorders, both parents of adult children with mental disorders37, 81, 82 and adult children of parents with mental disorders.38 Stigma by association with children with autism has been reported. Gray53 observed that mothers perceived more stigma than fathers and that parents with younger children (< 12 years old) perceived especially high levels of stigma by association. Although studying an adult population, Gonzalez and colleagues37 also noted the influence of child age, primarily by extrapolating from their observations regarding associations with early age of onset of a patient’s disorder. Apart from studies of other stigmatized childhood conditions, e.g., mental retardation83 or epilepsy,12 stigma by association for parents of children with mental disorders is under-researched. Some have encouraged focus on generalized mental health conditions such as emotional and behavioral problems rather than specific disorders, particularly for school age children or school-based mental health support programs.84

Among caregivers of adults with bipolar disorders, awareness of stigma by association has been shown to be linked to reports of depression.38 Previous research in caregiver strain has shown an association between child symptomatology and caregiver depression.4 This is attributed to the strain of coping with not only the family member’s condition but also with others’ response to the condition and the family. Birenbaum’s83 qualitative studies detailed parents’ daily struggles with negative public reactions to their children’s autism and the negative psychological impact of these experiences. Brannan and Heflinger4 included items about stigma (fear that the child would be labeled, fear of what family and friends would think) in their family perceptions subscale; greater endorsement of these perceptions was associated with higher reports of caregiver strain among parents of children with serious emotional disorders. Casting a broader net into the child health literature, we know from some studies of physical health conditions such as epilepsy that young children and their families are at risk of being stigmatized and that they might respond to both anticipated and experienced stigma in ways that compromise their own quality of life, such as social withdrawal and/or reluctance to seek help.12 Delineating the process by which these effects occur, such as the Corrigan et al self-stigmatization model,15 might be a fruitful area of research.

A key premise of our interest in explicating this framework of the stigma experience is to develop a better understanding of the link between stigma and the use (or barriers to use) of mental health services. Among families of children with serious emotional disorders, stigma has been documented as a potential barrier to receiving mental health services primarily because of the influence of stigma on parents.4 Stigma was demonstrated to be a significant issue among a rural group of parents and the most often endorsed barrier to services in that study (McMurry, Heflinger & VanHooser, in review). Half of the participants were concerned that people in their community would likely find out if a child received professional help and thought that people would blame parents for their children’s problems. Apprehension that the community would marginalize them if they knew that their children had been officially diagnosed with emotional or behavior problems was also a barrier to seeking mental health services for their children. Mothers whose children had more severe problems were more sensitive to stigma as a barrier to care, which may have reflected their personal experiences with community members’ responses.

Stigma towards mental health services

In addition, and consistent with emerging conceptual literature,17 our framework begins to acknowledge that mental health services can also be the target of stigma. In adult mental health, Taylor and Dear 71 have revised and tested scales for assessing public attitudes towards community based mental health services for adults. They found, from the responses of a sample of adults in Toronto, Canada, that attitudes towards people with mental illness (clustered under subscales of authoritarianism, benevolence, social restrictiveness and community mental health ideology) predicted the acceptability of mental health facilities within a block of homes.71 In the area of child mental health, for example, the stigmatization of mental healthcare providers85 and services by the general public has been proposed as a significant barrier to the utilization of mental health services. Some studies on the stigmatization of specialist mental health vs. primary health services are underway, e.g. Polaha and Williams at East Tennessee State University. However, healthcare professionals’ experiences of stigma have not been documented, though this is not difficult to conceptualize and some of its likely effects are not that difficult to imagine and even appreciate--e.g., reported reluctance among medical students to disclose help-seeking for mental health problems80 and/or specialize in psychiatry as a direct result of the stigma of psychiatry within the professions85 and the widely acknowledged lack of parity between mental and physical health care providers.74, 79

Relationship of this Framework to Other Theoretical Models

Arguably our framework is limited by the three dimensional space in which it is currently described. As we explained, our work on this framework was to explicate the stigma experience itself so that we and the field could develop better measures and develop more comprehensive theoretical and practical understanding of stigma in child mental disorders. However, a comprehensive stigma theory needs to also address the factors that influence stigma as well as the consequences of stigma. Here we place our framework into several recently published theoretical models as an example of the type of theory adaptation that is needed.

Conceptual frameworks from social and cognitive psychology are useful for analyzing predictors of public attitudes, particularly frameworks related to social perception, how individuals acquire and maintain knowledge of the public mind and how the public mind might interact with and influence the private mind. In this regard the self-stigma framework is particularly helpful. Equally insightful are behavioral health models that recognize the social-ecological context of individuals, precisely that individuals are nested within social units which are structured hierarchically, from small social units like the family to larger units like administrative communities and/or society at large.66

While a number of healthcare access and use models (e.g., Network Episode Model63 and the Gateway Provider Model64) are advantageous for studying pathways to formal mental healthcare, the Framework Integrating Normative Influences on Stigma (FINIS)17 specifically notes the salience of stigma in the help seeking process. FINIS facilitates research on multi-level factors that likely influence stigma and their consequences. As noted by Pescosolido et al, “the FINIS framework focuses on the central theorem that several different levels of social life – micro or psychological and socio-cultural level or individual factors; meso or social network or organizational level factors; and macro or societal-wide factors – set the normative expectations that play out in the process of stigmatization” (Pescosolido, Martin, Lang & Olafsdottir, 2008, p. 433).17

Reminiscent of predecessor models, the FINIS incorporates the ecology of public attitudes towards mental illness and delineates linkages among antecedent factors and their consequences on service access and use. The framework is congruent with social psychology theories of child development and behavioral models of service use. The FINIS allows for developing structural models delineating processes by which public stigma likely influences mental health outcomes among direct consumers. FINIS helps to understand how an adult or adolescent might deal with or be impacted by multiple forces that engender and sustain stigma. However, Pescosolido’s framework omits what we believe are crucial constructs/domains that are necessary to better understand stigma and its consequences for children with mental disorders and their families.

The overarching implications from this literature review and our proposed framework for understanding the stigma experience using dimensions of stigma, context of stigma, and targets of stigma is that recognition of these is critical for practice and research. Focusing on our own behavior and attitudes towards the children we work with and their families – and paying attention to the policies and procedures in our offices and agencies, including the use of person first language – will help not only identify potential institutional stigmatization, but help sensitize us to the everyday experiences of stereotypes, devaluation, and discrimination experienced by children and their families. Helping them identify these stressors could improve treatment planning and their goals for improved community functioning. Furthermore, understanding that family members are targets of stigma by association and exploring the resulting barriers may improve treatment compliance and follow up with referrals. Stigma researchers should consider insights from literature exploring cultural, racial and ethnic portrayals and understandings of mental illness. In culturally diverse contexts, the framework has to account for socio-culturally defined idiosyncrasies of mental disorders as well as potential interactions between mental illness and other socially devalued statuses such as AIDS-orphanhood,86 skin color, ethnicity, gender, disability, non-heterosexual sexual orientation,60 social economic status or neighborhood affiliation.1, 29–32

Theoretical models and associated plans for research also need to include these constructs. We propose specifically that existing models be adapted by: (a) adding family members and services as potential targets of stigma; and (b) acknowledging courtesy stigma, as reviewed in our framework above. Furthermore, we propose that the models also recognize delay or avoidance of help-seeking as a potential response to stigma. These adaptations allow the examination of the two consequences we mentioned earlier that are of particular relevance in child mental disorders, (a) caregiver strain as a response to stigma, and (b) the effects of stigma on help-seeking. Ultimately, we want to generate more knowledge about this phenomenon in order to design and test effective anti-stigma interventions primarily targeting caregivers of children and young adolescents with mental disorders. While we promote the development of measures of stigma dimensions, context, and targets suitable for child mental health services research, we also want to acknowledge the important role that qualitative methods can play in explicating these constructs and better understanding the experience of stigma for children with mental disorders and their families.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH70680) and an internal grant from the authors’ institution. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

Portions of this paper were presented at the 4th International Stigma Conference, Royal College of Surgeons, London, Jan, 21–23, 2009.

Disclosure: Drs. Mukolo, Heflinger, and Wallston report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Abraham Mukolo, Institute for Global Health, Vanderbilt University Medical Center

Craig Anne Heflinger, Department of Human & Organizational Development, Vanderbilt University

Kenneth A. Wallston, School of Nursing, Vanderbilt University

References

- 1.Oetzel J, Duran B, Lucero J, Jiang Y. Rural American Indians’ perspectives of obstacles in the mental health treatment process in three treatment sectors. Psychological Services. 2006;3(2):117–128. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson VLS, Noel JG, Campbell J. Stigmatization, discrimination, and mental health: The impact of multiple identity status. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2004 Oct;74(4):529–544. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.74.4.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeh M, McCabe K, Hough RL, Dupuis D, Hazen A. Racial/ethnic differences in parent endorsement of barriers to mental health services for youth. Mental Health Services Research. 2003;5(2):65–77. doi: 10.1023/a:1023286210205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brannan AM, Heflinger CA. Caregiver, child, family and service system contributors to caregiver strain in two child mental health service systems. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2006;33(4):408–422. doi: 10.1007/s11414-006-9035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pescosolido BA, Jensen PS, Martin JK, Perry BL, Olafsdottir S, Fettes D. Public knowledge and assessment of child mental health problems: Findings from the National Stigma Study-Children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47(3):339–349. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318160e3a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schachter HM, Girardi A, Ly M, et al. Effects of school-based interventions on mental health stigmatization: a systematic review. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. 2008;2(1):18. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandra A, Minkovitz CS. Factors that influence mental health stigma among 8th grade adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007;36:763–774. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heflinger CA, Simpkins CG, Foster EM. Modeling child and adolescent psychiatric hospital utilization: A framework for examining predictors of service use. Children’s Services. 2002;5(3):151–171. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brannan AM, Heflinger CA. Distinguishing caregiver strain from psychological distress: Modeling the relationships among child, family, and caregiver variables. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2001;10(4):405–418. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nadeem E, Lange JM, Edge D, Fongwa M, Belin T, Miranda J. Does stigma keep poor young immigrant and U.S.-born Black and Latina women from seeking mental health care? Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:1547–1554. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.12.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Austin JK, MacLeod J, Dunn DW, Shen J, Perkins SM. Measuring stigma in children with epilepsy and their parents: instrument development and testing. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2004;5:472–482. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang LH, Kleinman A, Link BG, Phelan JC, Leed S, Good B. Culture and stigma: Adding moral experience to stigma theory. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64:1524–1535. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hinshaw SP, Stier A. Stigma as related to mental disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:367–393. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Barr L. The self-stigma of mental illness: Implications for self-esteem and self-efficacy. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2006;25(9):875–884. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Link BG, Cullen FT, Struening EL, Shrout PE, Dohrenwend BP. A Modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: an empirical assessment. American Sociological Review. 1989;54:400–423. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pescosolido BA, Martin JK, Lang A, Olafsdottir S. Rethinking theoretical approaches to stigma: A framework integrating normative influences on stigma (FINIS) Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(3):431–440. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phelan JC, Link BG, Dovidio JF. Stigma and prejudice: One animal or two? Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(3):358–367. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scheff TJ. The labelling theory of mental illness. American Sociological Review. 1974;39(3):444–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:363–385. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heatherton TF, Kleck RE, Hebl MR, Hull JG, editors. The social psychology of stigma. New York: Guilford Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Snowden LR, Pingitore D. Frequency and scope of mental health service delivery to African Americans in primary care. Mental Health Services Research. 2002 Sep;4(3):123–130. doi: 10.1023/a:1019709728333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hinshaw SP. The stigmatization of mental illness in children and parents: developmental issues, family concerns, and research needs. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46(7):714–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLaughlin ME, Bell MP, Stringer DY. Stigma and acceptance of persons with disabilities: Understudied aspects of workforce diversity. Group Organization Management. 2004;29:302–334. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corrigan PW, River LP, Lundin RK, et al. Three strategies for changing attributions about severe mental illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2001;27(2):187–195. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin J, Pescosolido BA, Tuch S. Of fear and loathing: a role of “disturbing behavior,” labels, and causal attributions in shaping public attitudes toward people with mental illness. Journal Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41:208–223. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corrigan PW, Lurie BD, Goldman HH, Slopen N, Medasani K, Phelan S. How adolescents perceive the stigma of mental illness and alcohol abuse. Psychiatric Services. 2005 May;56(5):544–550. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.5.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H. Public beliefs about schizophrenia and depression: similarities and differences. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2003;38:526–534. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0676-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whaley AL. Paranoia in African-American men receiving inpatient psychiatric treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and Law. 2004;32:282–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams DR, Earl TR. Commentary: Race and mental health--more questions than answers. Internatinal Journal of Epidemiology. 2007 June 11;36(4):758–760. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen L, Huang LN, Arganza GF, Liao Q. The influence of race and ethnicity on psychiatric diagnoses and clinical characteristics of children and adolescents in children’s services. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13(1):18–25. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schnittker J, Pescosolido BA, Croghan TW. Are African Americans really less willing to use health care? Social Problems. 2005;52(2):255–271. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lauber C, Sartorius N. At issue: Anti-stigma-endeavours. International Review of Psychiatry. 2007;19(2):103–106. doi: 10.1080/09540260701278705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walker JS, Coleman D, Lee J, Squire PN, Friesen BJ. Children’s stigmatization of childhood depression and ADHD: magnitude and demographic variation in a national sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008 Aug;47(8):912–920. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318179961a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kusow AM. Contesting stigma: On Goffman’s assumptions of normative order. Symbolic Interaction. 2004;27(2):179–197. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Link BG, Yang LH, Phelan JC, Collins PY. Measuring mental illness stigma. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2004;30(3):511–554. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gonzalez JM, Rosenheck RA, Perlick DA, et al. Factors associated with stigma among caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder in the STEP-BD study. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(1):41–48. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perlick DA, Miklowitz DJ, Link BG, et al. Perceived stigma and depression among caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;190:535–536. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.020826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luty J, Umoh O, Sessay M, Sarkhel A. Effectiveness of Changing Minds campaign factsheets in reducing stigmatised attitudes towards mental illness. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2007;31(10):377–381. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pescosolido BA, Fettes DL, Martin JK, Monahan J, McLeod JD. Perceived dangerousness of children with mental health problems and support for coerced treatment. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:619–625. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.5.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Link BG, Cullen FT, Frank J, Wozniak JF. The social rejection of former mental patients: Understanding why labels matter. The American Journal of Sociology. 1987 May;92(6):1461–1500. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beatty JE, Kirby SL. Beyond the legal environment: How stigma influences invisible identity groups in the workplace. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal. 2006;18 (1):29–44. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klin A, Lemish D. Mental disorders stigma in the media: review of studies on production, content, and influences. J Health Commun. 2008 Jul–Aug;13(5):434–449. doi: 10.1080/10810730802198813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stout PA, Villegas J, Jennings NA. Images of mental illness in the media: identifying gaps in the research. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30(3):543–561. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stuart H. Media portrayal of mental illness and its treatments: what effect does it have on people with mental illness? CNS Drugs. 2006;20(2):99–106. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200620020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Slopen NB, Watson AC, Gracia G, Corrigan PW. Age analysis of newspaper coverage of mental illness. J Health Commun. 2007 Jan–Feb;12(1):3–15. doi: 10.1080/10810730601091292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morgan AJ, Jorm AF. Recall of news stories about mental illness by Australian youth: associations with help-seeking attitudes and stigma. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009 Sep;43(9):866–872. doi: 10.1080/00048670903107567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheng-Fang Y, Cheng-Chun C, Yu L, Tze-Chun T, Ju-Yu Y, Chih-Hung K. Self-stigma and its correlates among outpatients with depressive disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56:599–601. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.5.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ritsher JB, Phelan JC. Internalized stigma predicts erosion of morale among psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatry Research. 2004;129(3):257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vauth R, Kleim B, Wirtz M, Corrigan PW. Self-efficacy and empowerment as outcomes of self-stigmatizing and coping with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research. 2007;150:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rsch N, Lieb K, Bohus M, Corrigan PW. Self -stigma, empowerment, and perceived legitimacy of discrimination among women with mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57(3):399–402. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Watson AC, Corrigan P, Larson JE, Sells M. Self-stigma in people with mental illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2007 January;33(6):1312–1318. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gray DE. Perceptions of stigma: The parents of autistic children. Sociology of Health & Illness. 1993;15(1):102–120. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Link BG, Struening EL, Rahav M, Phelan JC, Nuttbrock L. On stigma and its consequences: Evidence from a longitudinal study of men with dual diagnoses of mental illness and substance abuse. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997 Jun;38(2):177–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sirey J, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, et al. Perceived stigma as a predictor of treatment discontinuation in young and older outpatients with depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:479–481. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Timlin-Scalera RM, Ponterreto JG, Blumberg FC, et al. A grounded theory study of help-seeking behaviors among White male high school students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2003;50:339–350. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huh D, Tristan J, Wade E, Stice E. Does problem behavior elicit poor parenting? A prospective study of adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2006 March;21(2):185–204. doi: 10.1177/0743558405285462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mohr WK. Rethinking professional attitudes in mental health settings. Qualitative Health Research. 2000 Sept;10(5):595–611. doi: 10.1177/104973200129118679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brannan AM, Heflinger CA, Foster EM. The role of caregiver strain and other family variables in determining children’s use of mental health services. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2003;11(2):78–92. [Google Scholar]

- 60.APA Task Force on Appropriate Therapeutic Responses to Sexual Orientation. Report of the Task Force on Appropriate Therapeutic Responses to Sexual Orientation. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; Aug, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Herek GM. Sexual stigma and sexual prejudice in the United States: a conceptual framework. Nebr Symp Motiv. 2009;54:65–111. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-09556-1_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thornicroft G, Rose D, Kassam A, Sartorius N. Stigma: ignorance, prejudice or discrimination? The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2007 March 1;190(3):192–193. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.025791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pescosolido BA, Wright ER, Alegria M, Vera M. Social networks and patterns of use among the poor with mental health problems in Puerto Rico. Med Care. 1998 Jul;36(7):1057–1072. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199807000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stiffman AR, Pescosolido B, Cabassa LJ. Building a model to understand youth service access: the gateway provider model. Ment Health Serv Res. 2004 Dec;6(4):189–198. doi: 10.1023/b:mhsr.0000044745.09952.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zwaanswijk M, Van der Ende J, Verhaak PF, Bensing JM, Verhulst FC. The different stages and actors involved in the process leading to the use of adolescent mental health services. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007 Oct;12(4):567–582. doi: 10.1177/1359104507080985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Andersen RM. Revisiting the Behavioral Model and access to medical care: Does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36(March):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Watson AC, Otey E, Westbrook AL, et al. Changing middle schoolers’ attitudes about mental illness through education. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2004;30(3):563–572. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fox C, Buchanan-Barrow E, Barrett M. Children’s understanding of mental illness: An exploratory study. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2008 Jan;34(1):10–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2007.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jorm AF, Wright A. Influences on young people’s stigmatising attitudes towards peers with mental disorders: national survey of young Australians and their parents. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2008 Feb;192(2):144–149. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.039404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wahl OF. Children’s views of mental illness: a review of the literature. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Skills. 2002;6:134–158. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Taylor SM, Dear MJ. Scaling community attitudes towards the mentally ill. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1981;7(2):225–240. doi: 10.1093/schbul/7.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rosenfield S, Lennon MC, White H. Mental health and the self: Self-salience and the emergence of internalizing and externalizing problems. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005;46:326–340. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vogel DL, Wade NG, Haake S. Measuring the self-stigma associated with seeking psychological help. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2006 July;53(3):325–338. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lauber C. Recommendations of mental health professionals and the general population on how to treat mental disorders. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2005;40(10):835–843. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0953-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Muroff JR, Hoerauf SL, Kim SYH. Is psychiatric research stigmatized?: An experimental survey of the public. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32(1):129–136. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vibha P, Saddichha S, Kumar R. Attitudes of ward attendants towards mental illness: Comparisons and predictors. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2008 Sept;54(5):469–478. doi: 10.1177/0020764008092190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.dosReis S, Mychailyszyn MP, Myers M, Riley AW. Coming to terms with ADHD: How urban African-American families come to seek care for their children. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:636–641. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.5.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Komiti A, Judd F, Jackson H. The influence of stigma and attitudes on seeking help from a GP for mental health problems: A rural context. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2006;41:738–745. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kjorstad MC. The current and future state of mental health service parity. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2003;27:34–42. doi: 10.2975/27.2003.34.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chew-Graham CA, Rogers A, Yassin N. ‘I wouldn’t want it on my CV or their records’: medical students’ experiences of help-seeking for mental health problems. Medical Education. 2003;37(10):873–880. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wahl OF, Harman CR. Family views of stigma. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1989;15(1):131–139. doi: 10.1093/schbul/15.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Larson JE, Corrigan PW. The stigma of families with mental illness. Academic Psychiatry. 2008 Apr;32:87–91. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.32.2.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Birenbaum A. On managing a courtesy stigma. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1970;11(3):196–206. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Richardson LA. Seeking and obtaining mental health services: what do parents expect? Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2001;15(5):223–231. doi: 10.1053/apnu.2001.27019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Smith MJ. Public psychiatry’: a neglected professional role? Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2008;14:339–346. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cluver L, Orkin M. Cumulative risk and AIDS–orphanhood: Interactions of stigma, bullying and poverty on child mental health in South Africa. Social Science and Medicine. 2009 Aug 25; doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]