Abstract

This research evaluates the properties of a measure of culturally linked values of Mexican Americans in early adolescence and adulthood. The items measure were derived from qualitative data provided by focus groups in which Mexican Americans’ (adolescents, mothers and fathers) perceptions of key values were discussed. The focus groups and a preliminary item refinement resulted in the fifty-item Mexican American Cultural Values Scales (identical for adolescents and adults) that includes nine value subscales. Analyses of data from two large previously published studies sampling Mexican American adolescents, mothers, and fathers provided evidence of the expected two correlated higher order factor structures, reliability, and construct validity of the subscales of the Mexican American Cultural Values Scales as indicators of values that are frequently associated with Mexican/Mexican American culture. The utility of this measure for use in longitudinal research, and in resolving some important theoretical questions regarding dual cultural adaptation, are discussed.

The Latino population in the United States is rapidly growing, young, relative to other ethnic groups, and includes a large number of immigrants (U.S. Census Bureau, 2002a; 2002b). Mexican Americans (Mexican heritage persons living in the U.S.) are the largest and fastest growing Latino subgroup representing 59.3% of the Latino population and 7.4% of the U.S. population (U.S. Bureau of Census, 2001, 2004). Mexican origin youth face the challenge of adapting to the mainstream1 culture while also maintaining ties to, and adapting to the Mexican American culture. That is, they often experience socialization pressures to conform to ethnic standards at home while also experiencing socialization pressures to conform to mainstream standards in the broader community and at school (see Padilla, 2006). Several authors suggest that challenges created by this dual cultural adaptation process represent a substantial risk for Mexican American (and other minority) youths and may lead to negative mental health outcomes, low self-esteem, conduct problems, school failure, drug and alcohol abuse, and financial instability (e. g., Gonzales & Kim, 1997; Gonzales, Knight, Morgan-Lopez, Saenz, & Sirolli, 2002; Phinney, 1992; Szapocznik, & Kurtines, 1980, 1993). Thus, a better understanding of the dual cultural adaptation process is critical, particularly among Mexican Americans, to better address their mental health and social service needs (Gonzales, Knight, Birman & Sirolli, 2004). This article presents an initial validation of a new measure of culturally related values to advance research on the dual cultural adaptation of Mexican Americans during adolescence and adulthood.

Recent theoretical perspectives have highlighted a wide array of psychosocial dimensions that are expected to change with dual cultural adaptation, including cultural knowledge, behaviors, beliefs, attitudes, values, and self-concept broadly conceived (e.g., Berry, 2003; Birman, 1998; Cuellar, Arnold, & Maldonado, 1995; Gonzales et al, 2002; Rudmin, 2003; Tsai, Chentsova-Dutton, & Wong, 2002). These changes occur through developmental and socialization processes that unfold throughout the lifespan of ethnic minorities that have been in the U.S. for several generations as well as those who have recently immigrated. Further, theory suggests that the changes produced by these processes may be dependent upon the developmental state of the individual (e.g., Knight, Jacobson, Gonzales, Roosa, & Saenz, 2009). For example, during early childhood, dual cultural adaptation may be manifested in relatively simple shifts in behavior (e.g., English/Spanish fluency, participation in parent-directed ethnic/mainstream social interactions) and knowledge (e.g., familiarity with ethnic/ mainstream customs and traditions). However, for most Mexican American youths this dual cultural adaptation is likely to manifest in more complex volitional behaviors (e.g., preference to speak English/Spanish, selection of ethnic/mainstream social contexts and peers, identity exploration), and culturally-linked values (e.g., traditional/mainstream family values) as they move through adolescence and into adulthood.

Values internalized during adolescence may be particularly important for understanding Mexican American youths’ adaptation because these values become the guiding force for future behavior and decisions about the appropriate cultural norms to follow in diverse settings. Theoretical frameworks suggest that many Mexican American adolescents develop a bicultural identity (e.g., Rudmin, 2008; Schwartz, et al., 2006) and adopt a value system and behavioral styles approved by members of the ethnic and mainstream cultures. Emerging evidence has linked Latino youths’ cultural values to a number of critical outcomes, including academic motivation (Fuligni, 2001), substance use (Brook et al., 1998), and externalizing behavior problems, (Gonzales et al., 2008). Theory also suggests that immigrants and other minority youth may have more positive adaptation in the U.S. when they adopt a combination of mainstream and traditional ethnic cultural values (i.e., biculturalism; e.g., Gonzales, et al. 2002). Further, youths who develop a relatively bicultural identity may more successfully navigate these dual sets of demands (e.g., Rudmin, 2008; Schwartz, Montgomery, & Briones, 2006). On the other hand, the demands of dual cultural adaptation may lead to the internalization of values that are sometimes difficult to reconcile (i.e., familism vs. independence), leading some youth to experience conflict internally (e.g., identity difficulties) and with significant others (i.e., intergenerational value discrepancies). Though frequently discussed in the theoretical literature, these hypotheses are seldom tested empirically because studies typically do not assess a broad range of value domains that can capture the dual cultural adaptation process.

Values are a primary mechanism by which culture is transmitted (Roosa et al., 2002) and the internalization of values is likely among the most important developmental achievements during adolescence (Knight, Jacobson, et al., 2009). Thus, we chose to develop a multidimensional measure of culturally-salient values for Mexican American adolescents that could be used across a broad range of ages, spanning from early adolescence to adulthood. The transitions of this period include moving from neighborhood schools to middle schools to high schools and then to the workplace and other adult roles, such as parenthood, that increase contact with members of the mainstream society and create opportunities/pressures for culturally related changes. A measure that can be used in longitudinal research to examine underlying processes of culture change across these transitions is critically needed to advance the current literature on cultural adaptation. A measure that can be used with both adolescents and adults also has an added benefit because it allows simultaneous assessment of adolescents and their parents to examine intergenerational discrepancies that have long been linked in the theoretical literature to Mexican American youth development and mental health.

Although there is an abundance of measures designed to assess dual cultural adaptations among adults and children (e.g., the Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans - II, Cuellar et al., 1995; and the Abbreviated Multidimensional Acculturation Scale, Zea, Asner-Self, Birman, & Buki, 2003), perhaps with the exception of the Multi-Group Ethnic Identity Measure (Phinney, 1992) and the Ethnic Identity Scale (Umaña-Taylor, Yazedjian, & Bamaca-Gomez, 2004), there is a paucity of measures developed for use with adolescents (see Knight, Jacobson, et al., 2009 for a review of thirty-seven measures). Even the applicability of these two exceptions for longitudinal studies that include significant developmental transitions has not been carefully examined (Knight, Jacobson, et al., 2009). Furthermore, there are relatively few measures available to assess changes in culturally related values associated with the dual cultural adaptation demands experienced by any specific cultural groups (Knight, Jacobson, et al., 2009). This is important because, given the tremendous diversity in cultural histories, reasons for immigration, economic status, and social embeddedness both before and after immigration, it is quite possible that the development of culturally related values is likely not “pan-ethnic” and that these values may differ somewhat, even across specific Latino groups.

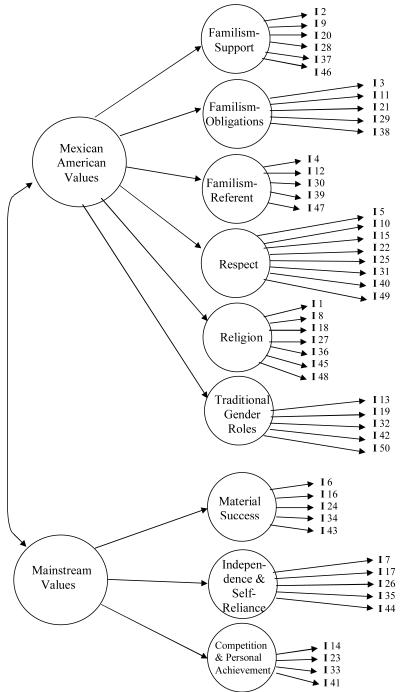

The purpose of this research was to examine the psychometric properties of a measure of culturally related values in samples of Mexican American adolescents and adults from initial assessments conducted in two large studies of Mexican American families (Puentes; Gonzales, Dumka, Mauricio, & Germán, 2007; La Familia; Roosa et al., 2008). The Mexican American Cultural Values Scales (MACVS) items were generated from focus groups of Mexican Americans (adolescents, mothers, and fathers) from a major metropolitan area, a suburban area, a rural mining town, and a Mexican border town in the southwest. The site selections and focus group procedures were designed to provide the broadest possible representation of Mexican Americans’ perceptions of culturally related values. Preliminary scale refinement (i.e., item elimination based upon very little variability in responses and vagueness of content) was based on the administration of the original 63 items in a Mexican American sample (Roosa et al., 2005). The trimmed MACVS is a 50-item scale that is identical for adolescents and adults (see Appendix A). The focus group participants identified a total of 9 values themes. Six of these themes reflect values associated with Mexican and Mexican American beliefs, behaviors, and traditions (i.e., Familism Support, Familism Obligations, Familism Referents, Respect, Religion, and Traditional Gender Roles), and 3 of these themes reflect contemporary mainstream American values (i.e., Material Success, Independence & Self-Reliance, Competition & Personal Achievement). These 9 specific values, and the items for each value subscale, came largely from direct comments of focus group members and are based on the perceptions of our Mexican American focus group participants rather than culturally linked values identified in earlier research (e.g., Peck & Diaz-Guerrero, 1967; Triandis, Marin, Lisansky, & Betancourt, 1984).

Some of the subscales overlap considerably with measures developed in previous research on Latino populations. Familism, for example, was perceived by the focus group participants as an important cultural value, and reflected on the different emphases within this broad construct such as the desirability to maintain close relationships (emotional support), the importance of tangible care-giving (obligation to family), and the reliance on communal interpersonal reflection to define the self (family as referent). The Respect subscale focused on intergenerational behaviors and the importance for children to defer to parents both in their demeanor and in yielding to parents’ wisdom on decisions. Spiritual beliefs and faith in a higher power were included in the Religion subscale. Items reflecting Traditional gender roles focused on differential expectations for males (bread-winner, independence, head of household) and females (child-rearing, protection of girls). The mainstream values emphasized the importance, respectively, of achieving material success (reflected in the prioritizing of earning money over other activities), gaining independence and self-reliance (self-sufficiency), and in seeking to separate oneself from others by competition and personal achievement.

For the present report, the psychometric properties of the MACVS were examined by using confirmatory factor analysis to examine the factor structure. Because the focus group participants linked some of these values to the Mexican American culture and others to the mainstream culture, a two higher order correlated factor model was expected (see Figure 1). Given the likelihood that the proportion of Mexican Americans that are bicultural, and socialized into the traditions and practices of both cultures, is substantial (see Padilla, 2006) the Mexican American values factor and the mainstream values factor were expected to be positively related. We also compared the MACVS subscale scores of immigrant and U.S. born Mexican Americans. An assimilation perspective suggests that the greater exposure to the mainstream of the U.S. born Mexican Americans in the Unites States would promote adoption of mainstream values and perhaps undermine their beliefs in the ethnic cultural values relative to their immigrant counterparts. In contrast, the anticipatory acculturation or ethnic-resilience perspective (e.g., Portes & Bach, 1985) suggests that immigrants in search of a more desirable life are drawn to this country because they perceive a compatibility with the values and opportunities available in the U.S., thus leading to the expectation that immigrants would score relatively high on the mainstream cultural values as well as the ethnic cultural values.

Figure 1.

The two higher order correlated factor model.

In addition, we used correlation and structural equation modeling analyses to examine construct validity relations of the subscales to theoretically related constructs available in the La Familia data set. The ethnic oriented values were expected to relate to ethnic pride and ethnic socialization because they should be elevated in families that actively promote traditional values and maintain a sense of pride in their ethnic heritage. Social support and parental acceptance should also be related to the ethnically oriented value domains, particularly with the familism values, because they are behavioral manifestations of the strong affective ties and family bonds specifically promoted by these familism values. Research also has shown that parental monitoring is higher in families that are more traditionally oriented because parents in these families are more hierarchical and parents are more actively involved in supervising and structuring adolescent activities (Fridrich & Flannery, 1995; Samaniego & Gonzales, 1999). Finally, we expected positive role models, a measure of the degree to which extended family members provide positive role models, should also show relations with the more traditional cultural values. Again, because a substantial proportion of the parents in this sample were immigrants, expectations regarding the relations of these construct validity variables to the mainstream values of Competition & Personal Achievement, Material Success, and Independence & Self-Reliance were less clear. However, two additional variables were included to assess construct validity of these three values. First, we hypothesized that adolescents who more strongly endorsed the Independence and Self-Reliance subscales would score higher on a measure of defiance, the extent to which they challenged their parent’s decisions. Second, we hypothesized that mothers and fathers who more strongly endorsed the Material Success subscale would have higher economic expectations and perceived necessities that were unmet.

METHOD

Puentes Study

Participants

The sample consisted of 598 seventh-grade adolescents and their Mexican American parents from 5 junior high schools that served primarily low-income populations (80% of students were eligible for free lunches) in a large southwestern metropolitan area with a substantial proportion of Mexican American and European American families and a relatively smaller proportion of families from other ethnic/racial groups. Family incomes ranged from $1,000 per year to $150,000 per year, with a mean of $36,310 per year. The original study aimed to recruit Mexican-origin families into a program designed to prevent high school dropout and mental and behavioral health disorders in youth. Sixty-two percent of the 955 eligible families enrolled and completed the first wave of assessments. In addition, the project required that both parents and youth be able to participate in the assessments and the intervention sessions in the same language; 6% of the families were ineligible because of this requirement. The current investigation uses data from the assessments that occurred prior to exposure to the intervention.

Of the 598 adolescents, 303 (50.6%) were female, 295 (49.2%) were male, 112 (18.7%) were born in Mexico, and 447 (74.7%) were born in the United States. Adolescents ranged in age from 11 to 14 years, with a mean age of 12.3 years. Three hundred and nineteen adolescents (53.4%) were interviewed in Spanish and 278 in English (46.6%). Of the parents, 573 mothers and 331 fathers participated in the interviews. Among the mothers, 347 (60.6%) were born in Mexico, 222 (38.7%) were born in the United States (4 mothers did not report their birthplace), 314 (54.8%) were interviewed in Spanish and 259 (45.2%) were interviewed in English. Among the fathers, 227 (68.6%) were born in Mexico, 104 (31.4%) were born in the United States, 200 (60.4%) were interviewed in Spanish and 131 (39.6%) were interviewed in English.

In-home interviews were conducted by trained interviewers using laptop computers. Interviewers were trained to conduct the parent and child surveys in separate rooms and/or out of hearing of other family members. Interviewers read each survey question and possible responses aloud in either Spanish or English to reduce problems associated with variations in literacy. All measures were translated and back-translated to ensure equivalence of all content (Behling & Law, 2000). Family members received $30 for participating, for a total of $60 for one-parent and $90 for two-parent families.

Measures

All participants completed the MACVS (see Appendix A).2 The MACVS was translated to Spanish by one bilingual translator and back-translated into English by a second bilingual translator, and discrepancies were resolved by conference between members of the research team and the translators. In addition, mothers reported the country in which their child was born and mothers and fathers reported their own country of birth.

Analysis Strategy

First, preliminary confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) were computed for each subscale of the MACVS to examine the degree to which the individual items on each subscale formed a factor. Second, several CFAs were conducted to compare alternative factor structures for the MACVS. These models included a one factor model, a nine independent factors model, a nine correlated factors model, a two independent higher order factors model, and the expected two higher order correlated factor model (see Figure 1) that conforms to the dual cultural adaptation framework. Third, multiple group CFAs were conducted to allow for a comparison of a model that constrained factor loadings to be equivalent across adolescents, mothers, and fathers to a model that allows the factor loadings to differ across these groups. To evaluate model fit in all of these CFAs we relied upon the joint criteria suggested by Hu and Bentler (1999), in which an acceptable fit is indicated by a SRMR ≤ .09 and either a CFI ≥ .95 or a RMSEA ≤ .06, because simulation studies revealed that using this combination rule resulted in low Type I and Type II error rates. In the present analyses, the CFI index was considered less crucial because it is vulnerable to influences arising from the general correlation level among subscales and items on the different subscales (Rigdon, 1996). In addition, we expected the standardized factor loadings to be .30 or higher (e.g., Brown, 2006). The AIC and BIC were used to compare the one factor, nine factor, and two higher order factor models because these models were not nested. Lower AIC and BIC values indicate a better fitting model (Kuha, 2004). The difference in chi-square was used to compare the nested models, such as the uncorrelated and correlated two higher order factor models.

Because the items for each value subscale, and the value subscales themselves, were derived primarily from the specific comments of focus group participants, only modification indices regarding correlated errors were considered during the evaluation of model fit. All of these maximum-likelihood CFAs were conducted using Mplus 4.1 using listwise deletion to handle missing data. Fourth, the MACVS subscale scores were compared for participants born in Mexico and those born in the U.S. using independent samples multivariate analysis of variance and Bonferroni corrected univariate F-tests. Finally, the relations between the MACVS subscales and several variables included in the La Familia data set were examined to provide limited evidence of the construct validity of the MACVS.

RESULTS

Preliminary analyses

The fit of the single latent factor model for each individual subscale was examined using a series of CFAs for each reporter (adolescents, mothers and fathers). Tables of these fits are available upon request. In these 27 individual subscale CFAs the father’s report of respect did not form an acceptable subscale structure based upon the Hu and Bentler (1999) criteria. The individual subscale internal consistency coefficients (i.e., Cronbach’s) alphas for adolescent, mother, and father reports are: Familism Support (.67, .58, and .60, respectively); Familism Obligations (.65, .55, .46); Familism Referents (.61, .63, .53); Religion (.78, .78, .84); Respect (.75, .52, .45); Traditional Gender Roles (.73, .66, .67); Material Success (.74, .78, .78); Independence & Self Reliance (.48, .35, .40); and Competition & Personal Achievement (.57, .65, .62). The internal consistence coefficients for a composite of the items from the three familism subscales are .84 for adolescents, .79 for mothers, and .75 for fathers. The internal consistency coefficients for a composite of the items from the overall Mexican American values subscales are .89 for adolescents, .87 for mothers, and .84 for fathers. The internal consistency coefficients for a composite of the items from the overall Mainstream values subscales are .77 for adolescents, .79 for mothers, and .79 for fathers.

Higher order latent factor models

To determine the best fitting higher order latent factor model, we tested several alternative models. First, we examined a single latent factor with the 50-items as individual indicators. Second, we tested a model with nine uncorrelated independent factors representing the nine cultural values subscales. Third, we tested a model with nine correlated individual factors. Fourth, we tested a higher order factor model with two uncorrelated factors. Finally, we tested the anticipated higher order factor model with two correlated factors.

Initial analyses of the higher order factor models produced disturbance terms that were negative for two Familism subscales (Familism - Referents and Familism - Obligations). Given that these disturbance terms were not statistically significant, these disturbances were set to zero (Roger Millsap, personal communication, February 2006) and proper solutions emerged. Table 1 displays the fit indices for the higher order latent factor models. Three models fit the data well according to the cutoffs for the RMSEA and SRMR, including the nine correlated factors model, the two uncorrelated higher order factors model, and the two higher order correlated factors. As expected, compared to the alternative models, the proposed two higher order correlated factor model had the lowest AIC and BIC values and thus provided the best fit to the data for adolescents, mothers, and fathers. The chi-square difference indicated that compared to the two uncorrelated higher order factors, the two higher order correlated factor model fit significantly better for adolescents [χ2 difference (1) = 70.334], mothers [χ2 difference (1) = 156.122], and fathers [χ2 difference (1) = 70.486]. The two higher order factors correlated between 0.59 and 0.63 across the three reporters. In addition, the proposed two higher order correlated factor model provided an adequate fit to the data when the factor loadings were constrained to be identical for adolescents, mothers, and fathers when accounting for the dependencies between scores within families (χ2 = 5200.11, p < .001, RMSEA = .048; SRMR = .072) The factor loading for each item from the model constraining these loadings to be equal for adolescents, mothers, and fathers are reported in Appendix 1.3

Table 1.

Fit indices for the latent measurement models in the Puentes study

| Latent Models | Fit Indices | Adolescents | Mothers | Fathers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Latent Factor | χ 2 | (1175) = 4945.994* | (1175) = 4975.483* | (1175) = 3694.185* |

| CFI | .540 | .484 | .428 | |

| RMSEA | .073 | .075 | .080 | |

| SRMR | .091 | .088 | .099 | |

| AIC | 74378.951 | 72678.232 | 40003.227 | |

| BIC | 74817.975 | 73113.320 | 40383.439 | |

| Adjusted BIC | 74500.505 | 72795.863 | 40066.236 | |

|

| ||||

| 9 Independent Factors | χ 2 | (1175) = 4841.350* | (1175) = 4473.621* | (1175) = 3035.507* |

| CFI | .553 | .552 | .577 | |

| RMSEA | .072 | .070 | .069 | |

| SRMR | .170 | .150 | .144 | |

| AIC | 74274.307 | 72176.369 | 39344.549 | |

| BIC | 74713.331 | 72611.458 | 39724.761 | |

| Adjusted BIC | 74395.861 | 72294.001 | 39407.558 | |

|

| ||||

| 9 Correlated Factors | χ 2 | (1141) = 3093.264* | (1141) = 3188.288* | (1141) = 2322.516* |

| CFI | .762 | .722 | .732 | |

| RMSEA | .054 | .056 | .056 | |

| SRMR | .108 | .098 | .096 | |

| AIC | 72594.221 | 70959.036 | 38699.557 | |

| BIC | 73182.513 | 71542.055 | 39209.041 | |

| Adjusted BIC | 72757.103 | 71116.663 | 38783.989 | |

|

| ||||

| 2 Independent Higher Order Factors | χ 2 | (1168) = 3109.151* | (1168) = 3221.372* | (1168) = 2387.368* |

| CFI | .763 | .721 | .723 | |

| RMSEA | .053 | .055 | .056 | |

| SRMR | .098 | .099 | .099 | |

| AIC | 72556.108 | 70938.120 | 38710.410 | |

| BIC | 73025.864 | 71403.665 | 39117.236 | |

| Adjusted BIC | 72686.17 | 71063.986 | 38777.829 | |

|

| ||||

| 2 Correlated Higher Order Factors | χ 2 | (1167) = 3038.817* | (1167) = 3065.250* | (1167) = 2316.882* |

| CFI | .772 | .742 | .739 | |

| RMSEA | .052 | .053 | .055 | |

| SRMR | .080 | .072 | .080 | |

| AIC | 72487.774 | 70783.998 | 38641.924 | |

| BIC | 72961.920 | 71253.894 | 39052.552 | |

| Adjusted BIC | 72619.052 | 70911.040 | 38709.973 | |

p < .001

Differences between immigrants and non-immigrants

To examine differences separately on the two sets of values subscales, two multivariate analyses of variance were conducted for each reporter with immigrant status (born in Mexico vs. born in the U.S.) as the independent variable (Table 2). Among adolescents, immigrant status was significantly associated with ethnic cultural values (Familism Support, Familism Obligations, Familism Referents, Respect, Religion, and Traditional Gender Roles: Wilks’ Lambda = .977, Multivariate F = 2.16, p < .05, Partial Eta Squared = .023) but not mainstream cultural values (Material Success, Independence & Self-Reliance, and Competition & Personal Achievement: Wilks’ Lambda = .991, Multivariate F = 1.62, p = ns, Partial Eta Squared = .009). Adolescents born in Mexico scored significantly higher (using univariate F-test) on Familism Obligations, Familism Referent, Traditional Gender Roles and the overall Mexican American values compared to adolescents born in the U.S.

Table 2.

Means (Standard Deviations) for each Mexican American Cultural Values Scale subscale for immigrants and non-immigrants in the Puentes study

| Adolescents | Mothers | Fathers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mexican American Values Subscales | Born in Mexico N=112 | Born in U.S. N=447 | Born in Mexico N=347 | Born in U.S. N=222 | Born in Mexico N=227 | Born in U.S. N=98 |

| Familism - Support | 4.56 (.43) | 4.50 (.47) | 4.75 (.36) | 4.64 (.39)** | 4.71 (.36) | 4.69 (.31) |

| Familism - Obligations | 4.55 (.44) | 4.40 (.52)** | 4.38 (.52) | 4.10 (.53) *** | 4.47 (.45) | 4.35 (.45)* |

| Familism - Referent | 4.50 (.43) | 4.38 (.49)* | 4.47 (.52) | 4.04 (.58)*** | 4.58 (.40) | 4.28 (.47)*** |

| Respect | 4.54 (.41) | 4.47 (.47) | 4.41 (.49) | 4.45 (.43) | 4.46 (.43) | 4.61 (.32)** |

| Religion | 4.33 (.57) | 4.22 (.62) | 4.54 (.52) | 4.40 (.62)** | 4.48 (.53) | 4.31 (.82)* |

| Traditional Gender Roles | 3.27 (.97) | 3.05 (.85)* | 3.04 (.94) | 2.57 (.81)*** | 3.24 (.91) | 2.78 (.84)*** |

| Overall Mexican American Values | 4.29 (.39) | 4.16 (.41)** | 4.23 (.43) | 3.97 (.39)*** | 4.31 (.37) | 4.13 (.35)*** |

|

Mainstream Values Subscales Material Success |

2.56 (.93) | 2.56 (.81) | 2.45 (.93) | 2.00 (.71)*** | 2.73 (.93) | 2.14 (.82)*** |

| Independence & Self-Reliance | 3.78 (.72) | 3.72 (.62) | 3.98 (.63) | 3.84 (.56)** | 3.98 (.62) | 3.93 (.60) |

| Competition & Personal Achievement | ||||||

| 3.77 (.84) | 3.62 (.69) | 4.08 (.84) | 3.43 (.80)*** | 4.25 (.71) | 3.70 (.76)*** | |

| Overall Mainstream Values | 3.37 (.67) | 3.30 (.54) | 3.51 (.65) | 3.09 (.52)*** | 3.65 (.60) | 3.26 (.55)*** |

Significant differences between participants born in Mexico and those born in the U .S. :

p <. 05

p < .01

p < .001.

Among mothers, immigrant status was significantly associated with ethnic cultural values (Wilks’ Lambda = .773, Multivariate F = 27.54, p < .001, Partial Eta Squared = .227) and mainstream cultural values (Wilks’ Lambda = .857, Multivariate F = 31.46, p < .001, Partial Eta Squared = .143). Mothers born in Mexico scored significantly higher (using a univariate F-test) on Familism Support, Familism Obligations, Familism Referent, Religion, Traditional Gender Roles, and the overall Mexican American values (see Table 2) compared to mothers born in the U.S.. Mothers born in Mexico also scored significantly higher on Material Success, Independence & Self-Reliance, Competition & Personal Achievement, and overall mainstream values.

Among fathers, immigrant status was significantly associated with ethnic cultural values (Wilks’ Lambda = .765, Multivariate F = 16.25, p < .001, Partial Eta Squared = .235) and mainstream cultural values (Wilks’ Lambda = .858, Multivariate F = 17.70, p = .001, Partial Eta Squared = .142). Fathers born in Mexico scored significantly higher (using a univariate F-test) on Familism Obligations, Familism Referent, Religion, Traditional Gender Roles, and overall Mexican American values (see Table 2); and significantly lower on the Respect subscale, compared to fathers born in the U.S.. Fathers born in Mexico also scored significantly higher on Material Success, Competition & Personal Achievement and overall mainstream values.

La Familia Study

METHOD

Participants

The sample consisted of 750 fifth-grade Mexican American early adolescents and their parents from 47 public, religious, and charter schools in the same southwestern metropolitan area as the Puentes study. Family incomes ranged from less than $5,000 per year to more than $95,000 per year, with a mean between $30,001 and $40,000 per year. The project’s aims were to study the role of cultural processes in Mexican American families with adolescents (Roosa et al., 2008). Recruitment materials were sent home with all children in 5th grade in selected schools. Over 85% of those who returned recruitment materials were eligible for screening (e.g., Hispanic) and 1,028 met eligibility criteria (i.e., child lived with her/his biological mother, both of the child’s biological parents were of Mexican heritage, child attended participating school, no step-father or mother’s boyfriend present in the home, and the child was not severely learning disabled). Mothers (required), fathers (optional), and children (required) participated in in-home interviews lasting an average of about 2 ½ hours in English or Spanish.

Of the 750 adolescents, 365 (48.7%) were female, 385 (51.3%) were male, 223 (29.7%) were born in Mexico, and 527 (70.3%) were born in the United States. The mean age was 10.4 years. The vast majority of these adolescents were interviewed in English (82.4%). Among the mothers, 555 (74.0%) were born in Mexico, 193 (25.7%) were born in the United States (2 mothers did not report their birthplace), 523 (69.7%) were interviewed in Spanish and 227 (30.3%) were interviewed in English. Among the fathers, 373 (80.0%) were born in Mexico, 93 (20.0%) were born in the United States, 358 (76.8%) were interviewed in Spanish, and 108 (23.2%) were interviewed in English. The in-home interviewing procedure was identical to that in Puentes except that parents and adolescents could choose to complete the measures in different languages if they wished and each participating family member was paid $45.

Measures

Along with the MACVS, participants completed several measures that allowed for the assessment of construct validity of this measure. Six measures selected were expected to show positive relations with those values more associated with ethnic culture (Familism Support, Familism Obligations, Familism Referents, Respect, and Religion). These included Mexican American ethnic pride, ethnic socialization, social support, acceptance, parental monitoring, and positive role models in the family. For these measures, when translated versions were not already available, measures were translated to Spanish by one bilingual translator and back-translated into English by a second bilingual translator, and discrepancies were resolved by conference between members of the research team and the translators.

Mexican American Ethnic Pride

This 4-item scale assesses ethnic pride for Mexican Americans and is intended for adults and children (Thayer, Valiente, Hageman, Delgado, and Updegraff, 2002). Thayer et al. (2000) reported relying upon focus groups with Mexican American families as well as the existing research literature on ethnic pride to identify these items. Participants were asked to rate how much they agreed with each item on a Likert-type scale ranging from “not at all true (1)” to “very true (5)” for the following statements, (1) You have a lot of pride in being Mexican, (2) You feel good about your Mexican background, (3) You like people to know that your family is Mexican or Mexican American, and (4) You feel proud to see Latino or Mexican actors, musicians and artists being successful. Thayer et al. (2002) reported that factor analyses confirmed that this measure consists of one dimension with a Cronbach’s alpha of .81. In La Familia the Cronbach’s alpha was .63 for adolescents, .78 for mothers, and .77 for fathers.

Ethnic Socialization

The 10-item ethnic socialization scale was adopted from the Ethnic Identity Questionnaire (Bernal and Knight, 1993). The scale assesses the extent to which parents socialize children into Mexican culture. A sample item asks how often parents “tell their child that the color of a person’s skin does not mean that person is better or worse than anyone else?” Responses range from “1=almost never or never” to “4=a lot of the time (frequently)”. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha was .74 for mothers and .75 for fathers.

Social Support

The Multidimensional scale of Perceived Social Support (Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, & Farley, 1988) assesses perceived social support from family (e.g., “you can talk about your problems with your family”) and friends (e.g., “your friends really try to help you”). We added items to assess social support from “relatives you do not live with” (e.g., “you can count on your relatives when things go wrong”). Respondents indicated to what degree each of 12 statements is true on a Likert-type scale ranging from “1=not true at all” to “5=very true”. Reliabilities for the scale were .84 for adolescents, .86 for mothers, and .89 for fathers.

Acceptance

The acceptance subscale is an eight item measure based upon Schaefer’s (1965) Child Report of Parental Behavior Inventory (CRPBI) and assesses warmth within the parent child relationship (e.g., “Your mother cheered you up when you were sad”). This measure has since been adapted to assess parents’ perceptions as well (Barrera et al., 2002). Respondents were asked how often the parent performed the behavior described in the item and to respond on a 5 point Likert scale from almost never to almost always. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha was .82 for adolescents’ reports on mothers, .87 for adolescents’ reports on fathers, .79 for mothers, and .74 for fathers.

Monitoring

This 10-item scale assesses adolescents’ perceptions of their parent’s knowledge of their children’s actions, whereabouts, and friends (e.g. “Your mother/father knew what you were doing after school”). The scale is an adaptation of a scale used by Small (1994). The response scale ranges from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). The target child reported separately on his/her father and mother. In the current study the Cronbach’s alpha was .75 for adolescents’ reports on mothers and .85 for adolescents’ reports on fathers.

Positive Family Role Models

The 5-item Positive Family Role Models scale was developed for La Familia to provide information about behavioral models that youths are exposed to within their extended families. Parents were asked to report the extent to which extended family members have had different types of experiences. The scale includes experiences associated with academic engagement and success as important characteristics of positive role models. Because youths may be influenced in different ways by the adults and youths in their extended family, and because there may be generational differences in the type of behaviors exhibited within a family, we asked separate questions about the behavior of adults (18 years of age or older) and children in the extended family. Responses ranged from “1=none of them” to “5=all of them” for the following questions, (1) How many of the adults in your family have graduated from high school, (2) how many of the adults in your family hold full-time jobs, (3) how many of the adults in your family have gone to college, (4) how many of the younger members of your family were recognized for outstanding school work, and (5) how many of the younger members of your family were recognized for performance in extracurricular activities like sports, music, or art. Cronbach’s alphas for positive family role models were .73 for mothers and .68 for fathers.

Not Enough Money for Necessities

This 7-item measure, derived from economic hardship measures (Conger et al., 1991; Conger & Elder, 1994), assesses the sense of not having enough money for one’s needs. For example, parents were asked to respond to the following question on a scale ranging from “1= not true at all” to “5=very true”: “your family had enough money to afford the kind of home you needed”. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha was .92 for mother’s reports and .94 for father’s reports.

Adolescent Defiance

This 6-item measure was developed for La Familia to assess what adolescents do if they have a disagreement or difference of opinion with their mother. Adolescents responded using a scale ranging from “1 = almost never or never” to “5 = almost always or always” to rate the following statements, (1) You defend your opinions when you think you are right, (2) You argue with your mother until you get your way, (3) You tell you mother when you think she is wrong, (4) You ignore your mother’s wishes and just do what you want, (5) You try to persuade your mother to change her mind, and (6) You disobey your mother. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .64.

Country of Birth

Mothers reported the country in which their child was born and mothers and fathers reported the country in which they were born (U.S. or Mexico).

RESULTS

Preliminary analyses

Twenty-three of the 27 individual subscale CFAs using the La Familia data indicated an acceptable fit based upon the Hu and Bentler (1999) criteria. The four CFAs that did not produce an acceptable fit were: adolescent’s report of Familism Support; and mother’s report of Familism Obligation, Respect, and Independence& Self-Reliance. However, these model fits were not far from acceptable. The individual subscale internal consistency coefficients (i.e., Cronbach’s) alphas for adolescent, mother, and father reports are: Familism Support (.62, .60, and .57, respectively); Familism Obligations (.54, .55, .52); Familism Referents (.61, .63, .57); Religion (.71, .86, .86); Respect (.51, .69, .66); Traditional Gender Roles (.73, .73, .75); Material Success (.82, .81, .82); Independence & Self Reliance (.50, .50, .51); and Competition & Personal Achievement (.75, .71, .71). The internal consistency coefficients for a composite of the items from the three familism subscales are .80 for adolescents, .79 for mothers, and .79 for fathers. The internal consistency coefficients for a composite of the items from the overall Mexican American values subscales are .84 for adolescents, .88 for mothers, and .88 for fathers. The internal consistency coefficients for a composite of the items from the overall Mainstream values subscales are .84 for adolescents, .81 for mothers, and .82 for fathers.

Higher order latent factor models

Initial analyses of the higher order factor models produced modification indices that indicated that the model would fit slightly better if correlated errors were allowed between the traditional gender roles subscale and the mainstream culture values subscales. Table 3 displays the fit indices for the higher order latent factor models. Three models, the nine correlated factors model, the two uncorrelated higher order factors model, and the two higher order correlated factor model, fit the data well according to the cutoffs for the RMSEA and SRMR. A comparison of the adolescent alternative models revealed that the AIC value was lowest for the nine correlated factors model, whereas the BIC was lowest for the two correlated higher order factors model. For mother and father report, the lowest AIC and BIC values were reported for the nine correlated factors models. The chi-square difference indicated that compared to the two uncorrelated higher order factors, the two correlated higher order factors model fit significantly better for adolescents [χ2 difference (1) = 21.513], mothers [χ2 difference (1) = 76.705], and fathers [χ2 difference (1) = 101.052]. The two higher order factors correlated between 0.21 and 0.51 across the three reporters. In addition, the proposed two higher order correlated factor model provided an adequate fit to the data when factor loadings were constrained to be identical for adolescents, mothers, and fathers when accounting for dependencies between scores within families (χ2 = 5384.88, p < .001, RMSEA = .043; SRMR = .061). The factor loading for each item from the model constraining these loadings to be equal for adolescents, mothers, and fathers are reported in Appendix 1 (see footnote 3).

Table 3.

Fit indices for the latent measurement models in the La Familia study

| Latent Models | Fit Indices | Adolescents | Mothers | Fathers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Latent Factor | χ 2 | (1175) = 5492.900* | (1175) = 7307.878* | (1175) = 4728.578* |

| CFI | .495 | .459 | .484 | |

| RMSEA | .070 | .083 | .081 | |

| SRMR | .100 | .100 | .096 | |

| AIC | 95068.553 | 91130.817 | 57185.054 | |

| BIC | 95530.560 | 91592.691 | 57599.473 | |

| Adjusted BIC | 95213.021 | 91275.152 | 57282.096 | |

|

| ||||

| 9 Independent Factors | χ 2 | (1175) = 4693.134* | (1175) = 5681.262* | (1175) = 3980.757* |

| CFI | .589 | .603 | .593 | |

| RMSEA | .063 | .072 | .072 | |

| SRMR | .147 | .162 | .166 | |

| AIC | 94268.786 | 89504.200 | 56437.233 | |

| BIC | 94730.793 | 89966.074 | 56851.652 | |

| Adjusted BIC | 94413.254 | 89648.535 | 56534.275 | |

|

| ||||

| 9 Correlated Factors | χ 2 | (1139) = 2262.546* | (1139) = 3218.982* | (1139) = 2473.894* |

| CFI | .869 | .817 | .806 | |

| RMSEA | .036 | .049 | .050 | |

| SRMR | .055 | .062 | .068 | |

| AIC | 91910.198 | 87113.921 | 55002.370 | |

| BIC | 92538.528 | 87742.069 | 55565.979 | |

| Adjusted BIC | 92106.675 | 87310.216 | 55134.346 | |

|

| ||||

| 2 Independent Higher Order Factors | χ 2 | (1165) = 2383.542* | (1165) = 3649.536* | (1165) = 2755.835* |

| CFI | .858 | .781 | .769 | |

| RMSEA | .037 | .053 | .054 | |

| SRMR | .069 | .090 | .102 | |

| AIC | 91979.194 | 87492.475 | 55232.311 | |

| BIC | 92487.403 | 88000.536 | 55688.172 | |

| Adjusted BIC | 92138.110 | 87651.244 | 55339.057 | |

|

| ||||

| 2 Correlated Higher Order Factors | χ 2 | (1164) = 2362.029* | (1164) = 3572.831* | (1164) = 2654.783* |

| CFI | .860 | .788 | .784 | |

| RMSEA | .037 | .053 | .052 | |

| SRMR | .060 | .070 | .073 | |

| AIC | 91959.682 | 87417.769 | 55133.259 | |

| BIC | 92472.510 | 87930.449 | 55593.264 | |

| Adjusted BIC | 92120.041 | 87577.981 | 55240.975 | |

p < .001

Differences between immigrants and non-immigrants

Among adolescents, immigrant status was not significantly associated with ethnic cultural values (Familism Support, Familism Obligations, Familism Referents, Respect, Religion and Traditional Gender Roles: Wilks’ Lambda = .965, Multivariate F = 1.45, p = ns, Partial Eta Squared = .035) nor the mainstream cultural values (Material Success, Independence & Self-Reliance, and Competition & Personal Achievement: Wilks’ Lambda = 970, Multivariate F = 2.52, p = ns, Partial Eta Squared = .030, see Table 4).

Table 4.

Means (Standard Deviations) for each Mexican American Cultural Values Scale subscale for immigrants and non-immigrants in the La Familia study

| Adolescents | Mothers | Fathers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mexican American Values Subscales | Born in Mexico N=223 | Born in U.S. N=527 | Born in Mexico N=555 | Born in U.S. N=193 | Born in Mexico N=373 | Born in U.S. N=93 |

| Familism - Support | 4.60 (.43) | 4.63 (.40) | 4.66 (.35) | 4.66 (.33) | 4.56 (.37) | 4.57 (.41) |

| Familism - Obligations | 4.52 (.46) | 4.53 (.45) | 4.23 (.53) | 4.17 (.52) | 4.21 (.55) | 4.15 (.49) |

| Familism - Referent | 4.48 (.46) | 4.43 (.48) | 4.33 (.50) | 3.95 (.59)*** | 4.38 (.49) | 4.11 (.50)** |

| Respect | 4.56 (.37) | 4.53 (.37) | 4.38 (.44) | 4.37 (.41) | 4.34 (.46) | 4.42 (.35) |

| Religion | 4.48 (.48) | 4.42 (.53) | 4.52 (.55) | 4.50 (.71) | 4.45 (.61) | 4.36 (.70) |

| Traditional Gender Roles | 3.54 (.86) | 3.12 (.96)** | 3.30 (.90) | 2.54 (.82)*** | 3.40 (.89) | 2.78 (.81)** |

| Overall Mexican American Values | 4.39 (.32) | 4.31 (.36)* | 4.27 (.38) | 4.10 (.38)*** | 4.25 (.40) | 4.12 (.38)* |

|

Mainstream Values Subscales Material Success |

2.34 (.99) | 2.11 (.93)* | 2.35 (.84) | 1.70 (.69)*** | 2.69 (.87) | 1.95 (.72)*** |

| Independence & Self-Reliance | 3.60 (.71) | 3.45 (.75)* | 3.82 (.64) | 3.63 (.64)** | 3.74 (.69) | 3.65 (.55) |

| Competition & Personal Achievement | 3.19 (1.00) | 2.84 (.94)** | 4.02 (.74) | 2.95 (.88)*** | 4.26 (.66) | 3.48 (.89)*** |

| Overall Mainstream Values | 3.08 (.73) | 2.84 (.73)** | 3.35 (.57) | 2.75 (.55)*** | 3.52 (.59) | 2.98 (.55)*** |

Significant differences between participants born in Mexico and those born in the U.S. :

p <. 05

p < .01

p < .001

Among mothers, immigrant status was significantly associated with ethnic cultural values (Wilks’ Lambda = .856, Multivariate F = 6.61, p < .001, Partial Eta Squared = .144) and mainstream cultural values (Wilks’ Lambda = .790, Multivariate F = 21.13, p < .001, Partial Eta Squared = .210). Mothers born in Mexico scored significantly higher (using a univariate F-test) on Familism Referent, Traditional Gender Roles, and overall Mexican American values (see Table 4) compared to mothers born in the U.S.. Mothers born in Mexico also scored significantly higher on Material Success, Independence & Self-Reliance, Competition & Personal Achievement, and overall mainstream values (see Table 4). In general, the overall pattern of mean differences among the mothers in La Familia was quite similar to the pattern of mean differences among the mothers in Puentes. All but three of the significant differences detected in Puentes were also significant in La Familia, and all of the three non-significant mean differences in La Familia were in the same direction as in Puentes.

Among fathers, immigrant status was significantly associated with ethnic cultural values (Wilks’ Lambda = .776, Multivariate F = 11.18, p < .001, Partial Eta Squared = .224) and mainstream cultural values (Wilks’ Lambda = .766, Multivariate F = 24.08, p = .001, Partial Eta Squared = .234). Fathers born in Mexico scored significantly higher (using a univariate F-test) on Familism Referent, Traditional Gender Roles, and overall Mexican American values (see Table 4), compared to fathers born in the U.S. Fathers born in Mexico also scored significantly higher on Material Success, Competition & Personal Achievement, and overall mainstream values. Once again, the overall pattern of mean differences for fathers in La Familia was quite similar to the pattern of mean differences for fathers in Puentes. Four of the eight significant differences detected in Puentes were similarly significant in La Familia, and all of the four non-significant mean differences in La Familia were in the same direction as in Puentes.

Construct validity analyses4

Table 5 presents construct validity relations for the individual MACVS subscales, as well as the overall Mexican American values and the mainstream values scores, in La Familia. The coefficients presented are based upon separate structural modeling analyses where each individual value subscale, and the overall Mexican American and overall mainstream values scales, were treated as latent constructs and the individual construct validity variables were treated as observed variables. Because of the number of pair-wise relations between values subscales and construct validity variables, and the large sample size, significance tests of these relations were Bonferroni corrected for the number of construct validity variables available. Generally, the pattern of construct validity relations was as expected. Ethnic pride, ethnic socialization, social support, parental acceptance, and monitoring were generally positively related to the ethnic values, with the exception of the Traditional Gender Roles subscale. Although, ethnic pride and ethnic socialization were also somewhat positively related to some of the mainstream values; social support, parental acceptance, and monitoring were either much less related or not significantly related to Material Success, Independence & Self-Reliance, Competition & Personal Achievement, and the overall mainstream values scores. Further, either the direction of the relation between positive role models in the family, not enough money for necessities, and defiance with ethnic cultural values and mainstream cultural values were different, or these construct validity variables were only significantly related to mainstream cultural values. Furthermore, tests of the moderation of these construct validity relations indicated that the magnitude of these relations was the same regardless of immigrant status or gender.

Table 5.

Construct validity relations of the Mexican American Cultural Values Scale subscales in the La Familia study

| Familism Support |

Familism Obligation |

Familism Referent |

Respect | Religion | Traditional Gender Roles |

Overall Material American Values |

Material Success |

Independence & Self Reliance |

Competition & Personal Achievement |

Overall Mainstream Values |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnic Pride: | |||||||||||

| Adolescents | .58* | .57* | .48* | .44* | .41* | .04 | .56* | -.01 | .19* | .10 | .08 |

| Mothers | .42* | .34* | .33* | .27* | .20* | .03 | .35* | .03 | .24* | .25* | .23* |

| Fathers | .40* | .35* | .35* | .28* | .19* | .06 | .35* | .04 | .26* | .23* | .24* |

|

| |||||||||||

| Ethnic Socialization: | |||||||||||

| Mothers | .30* | .35* | .51* | .26* | .19* | .31* | .40* | .25* | .24* | .39* | .39* |

| Fathers | .28* | .26* | .34* | .24* | .23* | .22* | .32* | .14 | .17 | .26* | .28* |

|

| |||||||||||

| Social Support: | |||||||||||

| Adolescents | .50* | .46* | .40* | .33* | .21* | .02 | .44* | .01 | .19* | .05 | .06 |

| Mothers | .31* | .13 | .02 | .13* | .04 | -.26* | .12 | -.18* | .02 | -.09 | -.13* |

| Fathers | .32* | .31* | .16 | .11 | .15* | -.21* | .18* | -.15* | .13 | .02 | -.02 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Parental Acceptance: | |||||||||||

| Adolescents - Mother | .44* | .44* | .42* | .39* | .25* | .08 | .45* | .01 | .21* | .10 | .09 |

| Adolescents - Father | .38* | .30* | .40* | .29* | .27* | .11 | .39* | .04 | .22* | .11 | .12 |

| Mothers | .40* | .25* | .21* | .22* | .18* | .09 | .29* | .03 | .11 | .10 | .10 |

| Fathers | .33* | .31* | .45* | .33* | .32* | .14 | .40* | .03 | .31* | .18* | .21* |

|

| |||||||||||

| Monitoring: | |||||||||||

| Adolescents - Mother | .37* | .35* | .26* | .31* | .10 | -.06 | .32* | -.14* | .05 | -.08 | -.09 |

| Adolescents - Father | .36* | .28* | .29* | .21* | .21* | -.03 | .31* | -.07 | .12 | -.02 | -.02 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Positive Role Model: | |||||||||||

| Mothers | .17* | .02 | -.11 | .14* | .04 | -.23* | .04 | -.15* | .09 | -.21* | -.20* |

| Fathers | .05 | -.04 | -.18 | -.08 | -.01 | -.23* | -.11* | -.17* | .04 | -.19* | -.19* |

|

| |||||||||||

| Delinquent Role Model: | |||||||||||

| Mothers | .08 | .08 | .21* | .00 | -.02 | .22* | .10 | .15* | .02 | .28* | .25* |

| Fathers | .04 | .09 | .21* | -.03 | .10 | .19* | .13 | .24* | .01 | .22* | .25* |

|

| |||||||||||

| Not Enough Money for Necessities: | |||||||||||

| Mothers | -.17* | -.01 | .09 | -.09 | -.05 | .33* | -.01 | .17* | -.10 | .18* | .18* |

| Fathers | -.13 | -.06 | .10 | -.03 | -.04 | .30* | .02 | .24* | -.06 | .22* | .24* |

|

| |||||||||||

| Defiance: | |||||||||||

| Adolescents | -.07 | .01 | -.01 | -.07 | .05 | .09 | -.02 | .13* | .22* | .15* | .17* |

p < .0057 Bonferroni corrected.

Discussion

Several key findings emerged from the confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs). The preliminary analyses indicated that the individual items on each subscale generally held together quite well. The fit indices for these individual subscale analyses were not good only for father’s report of respect in Puentes, for adolescent’s report of Familism Support in La Familia, and for mother’s report of Familism Obligation, Respect, and Independence& Self-Reliance in La Familia. However, none of these very few cases of relatively poor fit in the individual subscale analyses were replicated across reporters or studies. The multiple subscale CFAs indicated that the two higher order correlated factor model fit the data better than several alternative factor models in the Puentes study. In the La Familia study both the two higher order correlated factor model and the nine correlated factor model fit the data well and relative comparably. The consistency of the two higher order correlated factor model with the dual cultural adaptation theory guiding this research, and the support for this model in the Puentes findings, clearly supports the validity of the MACVS. As expected based upon the focus groups, the fit of the two higher order correlated factor model indicates that the ethnic cultural values were more highly related to one another, and the mainstream cultural values were more highly related to one another, than these sets of values were related across these higher order factors. Further, this supports the use of the overall Mexican American values and the overall mainstream values scores in future research.

However, should researchers choose to use scores on the individual subscales in their analyses they should do so with caution. While all of the confirmatory factor analyses indicated that the items within each subscale are measuring a common construct, some of the internal consistency coefficients are low, likely because of the small number of items on each subscale. Across reporters and studies the internal consistency coefficients are generally low (i.e., around .50 or lower) for the Independence & Self-Reliance subscale; reasonable (i.e., around .70 or higher) for the Religion and the Material Success subscales; and modest (i.e., around .60) for the remaining subscales. However, a recent Monte Carlo study (Yang, 2007) indicates that confirmatory factor analysis generally provides more precise estimates of reliability, compared to Cronbach’s alpha, except when sample sizes are low (i.e., N = 50). In contrast to the relatively low alphas for some individual subcales; the composite of the three familism subscales, the overall Mexican American values scale, and the Mainstream values scale, which are based upon a more substantial number of items, produced quite good (i.e., around .80 and above) internal consistency coefficients across reporters and studies. Hence, researchers interested in studying familism without differentiating elements of familism should feel free to use a composite these subscales.

The results of the cross-sectional confirmatory factor analyses constraining the item loadings among adolescents and the adults in both studies provides some limited support for the MACVS as a tool for measuring culturally related values among Mexican American adolescents and adults. These findings also provide limited support for the use of this measure in longitudinal assessments and analyses. However, assessments of the equivalence of item loadings from longitudinal assessments would be more direct evidence of longitudinal utility of the MACVS. Nevertheless, the equivalence of the item loadings across age groups within these two data sets is a useful first approximation. The confirmatory factor analysis findings and the construct validity findings also supported the use of this measure for examining static single-point in time relations of culturally related values to other culturally related phenomena.

The availability of a measure that can be used to examine changes over time in the internalization of culturally related values represents a valuable contribution to the methodological toolbox of researchers interested in studying acculturation and enculturation processes in communities largely populated by Mexican American and European American families. There has generally been an over reliance on studies that use proxies (i.e., comparisons across age, generation, or immigrant status) to estimate changes associated with the adaptation to a dual cultural context. Indeed, we know of only three longitudinal studies of individual changes in cultural orientation (French, Seidman, Allen, & Aber, 2006; Phinney & Chavira, 1992; Knight, Vargas-Chanes, Losoya, Cota-Robles, Chassin, & Lee, in press). One of these had a sample size and selection procedure insufficient for making scientific inferences and only one examined dual-axial changes. There are several ways in which these proxy studies may not adequately represent the psychological and behavioral changes associated with the dual cultural adaptation processes. First, cross-sectional comparisons across middle school to college students (e.g., Phinney & Chavira, 1992) are potentially problematic because these samples are not equally representative of the ethnic or cultural population being studied and the factors that make these samples differentially representative are likely to be associated with difficulties in dual cultural adaptation. The relatively substantial reported drop-out rates among Mexican Americans (U.S. Dept. of Education, 2000) create differential representativeness among school participants selected from diverse grade levels. This is particularly worrisome because increasing dropout rates with grade level may be associated with difficulties in dual cultural adaptation. Second, the selective and potentially time varying reasons for immigration from Mexico, the differential rates of undocumented status across generations, and frequent reliance on assessments exclusively in English in many studies (French, Seidman, Allen, & Aber, 2006; Phinney & Chavira, 1992; Knight, Vargas-Chanes et al., 2006) create the possibility that observed ethnic group, generational and age differences reflect more than the psychological and behavioral changes associated with dual cultural adaptation. We believe there is a great need for longitudinal assessments of dual cultural adaptation, and this research will require measures that are appropriate for use across a wide range of ages.

Our examination of the relation of the MACVS subscales with several other variables provides some limited evidence of construct validity. The Mexican American cultural values subscales are generally correlated with ethnic pride, ethnic socialization, social support, parental acceptance, and monitoring, as expected. The differential relations of the Mexican American and mainstream values to select construct validity variables, along with the fact that these subscales fit the expected two higher order correlated factor model indicates that the Mexican American values and mainstream values subscales are assessing distinct but related values. Furthermore, perhaps with the exception of the relations of the MACVS scores to the mother’s report of social support, the construct validity relations observed in the La Familia data are remarkably similar across reporters.

As expected, positive family role models was positively associated with two of the ethnic oriented values, specifically with family support and respect. However, what was even more noteworthy was the significant and opposite (negative) pattern of relations this variable showed with the mainstream values for adults (the family role models variables was not available for adolescents). When the adults in this sample reported more positive role models in the extended family, reflecting higher levels of academic and job success within their family, they were less likely to endorse materialistic and competitive values themselves. This finding is consistent with the positive relations of the lack of money for necessities with material success and the competition and personal achievement values. Together these findings suggest that a lack of educational / occupational success and financial stability may heighten the desire for material success and one’s willingness to adopt more competitive, self-focused values to achieve it. As expected, defiance was positively related to independence and self reliance. In fact, defiance showed positive relations with all three of the mainstream values. Unfortunately, measures of constructs even more conceptually related to material success, independence and self-reliance, and competition and personal achievement were not available in this preexisting data set.

The implication of the differences between the immigrants and non-immigrants for the validity of the MACVS is less clear because there is sound theoretical reason for at least two expected sets of relations. That the immigrant adolescents and adults scored higher than their non-immigrant peers on most of the Mexican American values is exactly what one would expect based upon their relative exposure to Mexican culture. However, at least among adults in our study, immigrants also scored higher on the mainstream values, perhaps because these values are intimately tied to their reasons for immigrating. Portes and Bach (1985) suggest that mass media in Mexico has heightened the attractiveness of modern consumerism; but underemployment and inequality in incomes deny access to goods to many in Mexico. They also suggest that the desire to immigrate and stay in the U.S. is based upon the desire for economic gains and a relatively positive assessment of their new life setting. However, with increases in education, English fluency, and information about the U.S. comes more critical attitudes and perceptions of discrimination among later generations. Similarly, Suarez-Orozco and Suarez-Orozco (1996) suggest that immigrants’ from Mexico come to the U.S. to better the lives of their family by finding a job, earning money, learning English, and getting their children educated. Despite relatively limited opportunities for them after they arrive, their dual frame of reference leads many immigrants to feel better off than they did in their country of origin. Mexican Americans born in the U.S., by comparison are more likely to have a single frame of reference and feel deprived relative to the members of the majority culture. If Mexican individuals come to the U.S. with the full awareness that valuing material success, independence & self-reliance, and competition & personal achievement are directly linked to economic prosperity in the U.S., endorsement of these values may be instrumentally linked to the decision to immigrate. The incongruence between these mainstream values and the Mexican American values may become more salient to Mexican Americans born in the U.S. and/or to those who may question whether they have fully realized the “promise” of immigration. Hence, Mexican adults who immigrate, relative to their U.S. born counterparts, may more highly endorse mainstream values. Further, while dual cultural adaptation may lead to relatively linear changes in some behavioral dimensions (e.g., language use, association with European Americans), the pattern of changes in other dimensions, particularly more significant (Marin, 1992) dimensions (e.g., culturally linked values) may not be so linear. Indeed, the consistent finding that immigrant adults in both samples reported greater endorsement of both Mexican American and mainstream values illustrates the importance of a dual axial framework and a bicultural identity (e.g., Padilla, 2006; Rudmin, 2008; Schwartz, Montgomery, & Briones, 2006). One cannot assume the adoption of a mainstream orientation necessarily means the loss of one’s traditional cultural orientation. These aspects of cultural adaptation can vary independently and one of the key contributions of the current measure is that it can allow future research to unpack key cultural value domains to better model and understand these complex patterns of adaptation.

There are a number of important limitations to the present studies. First, the selection of variables available for the examination of construct validity was limited by the variables available in the La Familia data set. Additional research will be necessary to fully identify the usefulness of the MACVS measure. Second, it was not reasonably possible to evaluate the similarity of factor loadings across either language or immigrant status. In Puentes, mothers, fathers and adolescents within each family all completed measures in the same language identified as the family’s dominant language because all three would subsequently participate in an intervention in a common language. Thus, family members did not select their strongest or preferred language which would best support tests of language invariance. In La Familia the distribution of language selection was highly confounded with reporter status because 17.6% of adolescents, and 69.7% of mothers, and 76.8% of fathers completed measures in Spanish. In addition, the computer assisted administration of the measures in both studies allowed participants to switch the language of administration of any item with which they had difficulty. Further, immigrant status was also highly confounded with reporter (adult, child) status in both studies. The comparison of factor loadings for this relatively large number of items across reporters would require us to combine all three samples within each study (while controlling for the dependency in the data within each family). The confounds between language and immigrant status with reporter status prevented us from combining data across reporters to allow for the very demanding test of the comparability of factor loadings for such a large number of items. However, given these confounds and the comparability of the factor loadings across reporters in both studies and the similarity of model fit across studies, it is reasonably unlikely to expect that the factor loadings would be greatly different across language versions and immigrant status. Finally, although immigrant status is a relatively crude indicator, these preexisting data sets were very limited in the available indicators of exposure to the Mexican American and mainstream cultures.

In conclusion, the present cross-sectional assessments clearly supported the MACVS as an indicator of the degree to which Mexican Americans endorse values more frequently associated with Mexican/Mexican American culture. Although the findings with regard to values more associated with mainstream culture are more limited, the confirmatory factor analyses and construct validity analyses did consistently indicate substantial relations among these items and of these scales to other variables. The present study provided substantial preliminary findings regarding the psychometric properties of the MACVS, and the utility of the integration of qualitative and quantitative research approaches in the development of culturally sensitive measures. However, a longitudinal examination of the changes in endorsement of these values subscales is needed to more fully explore the usefulness of this new measure.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by NIMH (grant #s 5-RO1-MH68920, 5-P30-MH39246, and 1-R01-MH64707), NICHD (grant # RO1-HD39666), and NSF (grant # BCS0132409).

Appendix A

The Mexican American Cultural Values scales

| English Version | Spanish Version |

|---|---|

| The next statements are about what people may think or believe. Remember, there are no right or wrong answers. Tell me how much you believe that... | “Las siguientes frases son acerca de lo que la gente puede pensar o creer. Recuerda, no hay respuestas correctas o incorrectas. Dime que tanto crees que. |

| Response Alternatives: | |

| 1 = Not at all. | 1 = Nada. |

| 2 = A little. | 2 = Poquito. |

| 3 = Somewhat. | 3 = Algo. |

| 4 = Very much. | 4 = Bastante. |

| 5 = Completely. | 5 = Completamente. |

| 1. One’s belief in God gives inner strength and meaning to life. (REL: .74, .72) | 1. La creencia en Dios da fuerza interna y significado a la vida. |

| 2. Parents should teach their children that the family always comes first. (FAM-SUP: .39, .28) | 2. Los padres deberían enseñarle a sus hijos que la familia siempre es primero. |

| 3. Children should be taught that it is their duty to care for their parents when their parents get old. (FAM-OB: .41, .42) | 3. Se les debería enseñar a los niños que es su obligación cuidar a sus padres cuando ellos envejezcan. |

| 4. Children should always do things to make their parents happy. (FAM-REF: .46, .39) | 4. Los niños siempre deberían hacer las cosas que hagan a sus padres felices. |

| 5. No matter what, children should always treat their parents with respect. (RESP: .46, .46) | 5. Sea lo que sea, los niños siempre deberían tratar a sus padres con respeto. |

| 6. Children should be taught that it is important to have a lot of money. (MATSUC: .52, .59) | 6. Se les debería enseñar a los niños que es importante tener mucho dinero. |

| 7. People should learn how to take care of themselves and not depend on others. (IND&SR: .37, .47) | 7. La gente debería aprender cómo cuidarse sola y no depender de otros. |

| 8. God is first; family is second. (REL: .44, .55) | 8. Dios está primero, la familia está segundo. |

| 9. Family provides a sense of security because they will always be there for you. (FAM-SUP: .51, .51) | 9. La familia provee un sentido de seguridad, porque ellos siempre estarán alli para usted. |

| 10. Children should respect adult relatives as if they were parents. (RESP: .56, .53) | 10. Los niños deberían respetar a familiares adultos como si fueran sus padres. |

| 11. If a relative is having a hard time financially, one should help them out if possible. (FAM-OB: .52, .51) | 11. Si un pariente está teniendo dificultades económicas, uno debería ayudarlo si puede. |

| 12. When it comes to important decisions, the family should ask for advice from close relatives. (FAM-REF: .47, .49) | 12. La familia debería pedir consejos a sus parientes más cercanos cuando se trata de decisiones importantes. |

| 13. Men should earn most of the money for the family so women can stay home and take care of the children and the home. (TGEN: .60, .64) | 13. Los hombres deberían ganar la mayoría del dinero para la familia para que las mujeres puedan quedarse en casa y cuidar a los hijos y el hogar. |

| 14. One must be ready to compete with others to get ahead. (COMP&PA: .52, .71) | 14. Uno tiene que estar listo para competir con otros si uno quiere salir adelante. |

| 15. Children should never question their parents’ decisions. (RESP: .42, .30) | 15. Los hijos nunca deberían cuestionar las decisions de los padres. |

| 16. Money is the key to happiness. (MATSUC: .70, .77) | 16. El dinero es la clave para la felicidad. |

| 17. The most important thing parents can teach their children is to be independent from others. (IND&SR: .46, .42) | 17. Lo más importante que los padres pueden enseñarle a sus hijos es que sean independientes de otros. |

| 18. Parents should teach their children to pray. (REL: .61, .51) | 18. Los padres deberían enseñarle a sus hijos a rezar. |

| 19. Families need to watch over and protect teenage girls more than teenage boys. (TGEN: .50, .55) | 19. Las familias necesitan vigilar y proteger más a las niñas adolescentes que a los niños adolescentes. |

| 20. It is always important to be united as a family. (FAM-SUP: .52, .38) | 20. Siempre es importante estar unidos como familia. |

| 21. A person should share their home with relatives if they need a place to stay. (FAM-OB: .44, .43) | 21. Uno debería compartir su casa con parientes si ellos necesitan donde quedarse. |

| 22. Children should be on their best behavior when visiting the homes of friends or relatives. (RESP: .52, .51) | 22. Los niños deberían portarse de la mejor manera cuando visitan las casas de amigos o familiares. |

| 23. Parents should encourage children to do everything better than others. (COMP&PA: .61, .74) | 23. Los padres deberían animar a los hijos para que hagan todo mejor que los demás. |

| 24. Owning a lot of nice things makes one very happy. (MATSUC: .50, .65) | 24. Tener muchas cosas buenas lo hace a uno muy feliz. |

| 25. Children should always honor their parents and never say bad things about them. (RESP: .57, .52) | 25. Los niños siempre deberían honrar a sus padres y nunca decir cosas malas de ellos. |

| 26. As children get older their parents should allow them to make their own decisions. (IND&SR: .26, .23) | 26. Según los niños van creciendo, los padres deberían dejar que ellos tomen sus propias decisions. |

| 27. If everything is taken away, one still has their faith in God. (REL: .69, .68) | 27. Si a uno le quitan todo, todavía le queda la fe en Dios. |

| 28. It is important to have close relationships with aunts/uncles, grandparents and cousins. (FAM-SUP: .59, .52) | 28. Es importante mantener relaciones cercanas con tíos, abuelos y primos. |

| 29. Older kids should take care of and be role models for their younger brothers and sisters. (FAM-OB: .54, .52) | 29. Los hermanos grandes deberían cuidar y darles el buen ejemplo a los hermanos y hermanas menores. |

| 30. Children should be taught to always be good because they represent the family. (FAM-REF: .57, .54) | 30. Se le debería enseñar a los niños a que siempre sean buenos porque ellos representan a la familia. |

| 31. Children should follow their parents’ rules, even if they think the rules are unfair. (RESP: .43, .41) | 31. Los niños deberían seguir las reglas de sus padres, aún cuando piensen que no son justas. |

| 32. It is important for the man to have more power in the family than the woman.(TGEN: .60, .66) | 32. En la familia es importante que el hombre tenga más poder que la mujer. |

| 33. Personal achievements are the most important things in life. (COMP&PA: .35, .40) | 33. Los logros personales son las cosas más importantes en la vida. |

| 34. The more money one has, the more respect they should get from others. (MATSUC: .71, .66) | 34. Entre más dinero uno tenga, más el respeto que uno debería recibir. |

| 35. When there are problems in life, a person can only count on him/herself. (IND&SR: .34, .47) | 35. Cuando hay problemas en la vida, uno sólo puede contar con sí mismo. |

| 36. It is important to thank God every day for all one has. (REL: .68, .68) | 36. Es importante darle gracias a Dios todos los días por todo lo que tenemos. |

| 37. Holidays and celebrations are important because the whole family comes together. (FAM-SUP: .43, .43) | 37. Los días festivos y las celebraciones son importantes porque se reúne toda la familia. |

| 38. Parents should be willing to make great sacrifices to make sure their children have a better life. (FAM-OB: .46, .35) | 38. Los padres deberían estar dispuestos a hacer grandes sacrificios para asegurarse que sus hijos tengan una vida mejor. |

| 39. A person should always think about their family when making important decisions. (FAM-REF: .48, .46) | 39. Uno siempre debería considerar a su familia cuando toma decisiones importantes. |

| 40. It is important for children to understand that their parents should have the final say when decisions are made in the family. (RESP: .46, .45) | 40. Es importante que los niños entiendan que sus padres deberían tener la última palabra cuando se toman decisiones en la familia. |

| 41. Parents should teach their children to compete to win. (COMP&PA: .72, .81) | 41. Los padres deberían enseñarle a sus hijos a competir para ganar. |