Abstract

Objective

To determine the change in parental ratings of executive function and behavior in children with primary hypertension following antihypertensive therapy.

Study design

Parents of untreated hypertensive subjects and controls completed the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) to assess behavioral correlates of executive function and the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) to assess internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Hypertensive subjects subsequently received antihypertensive therapy to achieve casual BP < 95th percentile. After 12 months, all parents again completed the BRIEF and CBCL.

Results

Twenty-two subjects with hypertension and 25 normotensive control subjects had both baseline and 12-month assessments. Hypertensive subject’s blood pressure improved (24-hr systolic BP load: mean baseline vs. 12-months, 60 vs. 25%, p < 0.001). Parent ratings of executive function improved from baseline to 12-months in the hypertensives (BRIEF Global Executive Composite T-score, Δ = −5.9, p = 0.001) but not in the normotensive controls (Δ = −0.36, p = 0.83). In contrast, T-scores on the Child Behavior Checklist Internalizing and Externalizing summary scales did not change significantly from baseline to 12-months in either hypertensive or control subjects.

Conclusions

Children with hypertension demonstrated improvement in parental ratings of executive function after 12 months of antihypertensive therapy.

Keywords: Neurocognitive function, blood pressure, treatment

Young adults with mild-to-moderate hypertension have lower performance on neurocognitive testing compared with matched normotensive controls.(1–3) Investigators have hypothesized that the performance deficits seen in adult patients with hypertension may represent an early manifestation of target organ damage to the brain(4). This would imply that such deficits might be reversible with antihypertensive treatment. Results of adult studies on the effect of antihypertensive medication on cognition have been inconsistent with respect to the existence and direction of drug effects.(1, 5) However, studies of the effects of antihypertensive medication on cognition in hypertensive adults often focused on middle-aged and older adults and were thereby limited by the potential confounding variable of advancing age. However, a study that focused on young hypertensive adults (mean age: men 33.7 years, women 29.8 years) suggested that their performance on neurocognitive testing may improve with effective antihypertensive therapy.(1, 6)

We recently reported that children with untreated, newly-diagnosed primary hypertension have worse parental ratings of executive function compared with matched normotensive controls. In addition, children with hypertension had higher parental ratings of internalizing problems (depression and anxiety) than children without hypertension.(7)

The objective of the current study was to evaluate the potential effect of antihypertensive therapy on neuropsychological processes by measuring parental assessments of executive function and internalizing and externalizing behaviors in a cohort of hypertensive subjects before and after 12 months of antihypertensive therapy, and by comparing these findings with parental assessment of a matched comparison group of children during the same time period. We hypothesized that parent ratings of executive function would improve among hypertensive children but remain unchanged among controls.

Methods

The participants in the current study were the hypertensive and control subjects from our initial report(7) who subsequently returned for reassessment after 12-months During the 12-month interval between study visits, the hypertensive subjects received standard of care antihypertensive therapy as detailed below. Control subjects were not seen between the initial assessment and the 12-month visit. Parents of the hypertensive and control study groups completed the same measures of executive function and internalizing and externalizing behavior at baseline and again at 12 months.

Our initial report compared children with primary hypertension to healthy normotensive control subjects who were proportionally matched for age, sex, race, obesity (BMI ≥ 95th percentile), mean estimated full-scale IQ, maternal education (less than high school, high school, college, above college), and annual household income (low, < $25,000; low-middle, $25,000 to $55,000; high-middle, $55,000 to $95,000; high, >$95,000).(7) The sample of newly diagnosed, previously untreated hypertensive subjects, aged 10 to 18 years, was recruited from the Pediatric Hypertension Clinic at the University of Rochester Medical Center. Each hypertensive subject had a history of office hypertension that was confirmed by the presence of mean daytime and/or nighttime BP ≥ 95th percentile on 24-hr ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM).(7, 8) The healthy normotensive control subjects did not have ABPM but were required to have 2 casual BP readings < 90th percentile in the 6 months preceding study entry.(7) Ambulatory BP index was defined as the subjects mean 24-hr BP divided by the 95th percentile. Blood pressure load was defined as the percent of BP readings ≥ 95th percentile for pediatric ABPM norms.(8)

Hypertensive subjects underwent repeat ABPM at the 12-month follow-up visit to assess the adequacy of the hypertension treatment. All hypertensive subjects underwent a complete 2-dimensional echocardiogram at the baseline visit to detect hypertensive target organ damage.(7, 9) Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) was defined as left ventricular mass index (LVMI) ≥ the 95th percentile (39.36 g/m2.7 for boys and 36.88 g/m2.7 for girls, respectively).(10) The current study protocol was approved by the Research Subjects Review Board of the University of Rochester Medical Center.

In order to confirm that the hypertension and control groups were proportion matched for mean IQ, prorated IQ was determined from the Block Design and Vocabulary subscales of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fourth Edition (for ages 10 – 15 years) or the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Third Edition (for ages ≥ 16 years) at the baseline study visit.(11)

To assess executive function, parents completed the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) at baseline and again at the 12-month follow-up study visit.(12) The BRIEF is an 86 item measure designed to assess executive functioning in 5 – 18 year old children. It reports 8 subscales which reflect different aspects of executive function including Inhibit, Shift, Emotional Control, Initiate, Working Memory, Plan/Organize, Organization of Materials, and Monitor. The BRIEF has two composite scales - the Behavior Regulation Index (BRI) and the Metacognition Index (MI), and a third summary score, the Global Executive Composite (GEC). Results are reported as sex and age-normed T-scores; higher scores indicate greater degrees of dysfunction.(12, 13) Scores ≥ 65 on the BRIEF are considered to be potentially clinically significant.(12)

To asses internalizing and externalizing behaviors, parents also completed the Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) at baseline and again at the 12-month study visit.(14) Internalizing behaviors reflect mood disturbance, including anxiety, depression, and social withdrawal. Externalizing behaviors reflect conflict with others and violation of social norms. The CBCL is a 118 item measure designed for the evaluation of children aged 6 – 18 years. The CBCL provides Internalizing and Externalizing summary scores reported as sex and age normed T-scores. Higher scores indicate greater degrees of behavioral and emotional problems. T-scores ≥ 64 on the Internalizing or Externalizing scales are considered in the clinical range, indicative of deviant behavior in the range of scores for children referred for professional mental health evaluation for behavioral or emotional problems.(14)

After the baseline assessment, hypertensive subjects were started on antihypertensive therapy according to local standard of care and national consensus guidelines.(15) All hypertensive subjects were counseled on lifestyle modification, including increased exercise, the DASH diet, salt restriction, and if needed, weight loss. For subjects with stage 1 hypertension without LVH, antihypertensive medication was started after 3 months if there was no improvement with lifestyle modification alone or initially in subjects who were felt to have already failed a concerted effort at lifestyle modification. Subjects with stage 1 hypertension without LVH who had consistent improvement with lifestyle modification alone were not prescribed antihypertensive medication. Subjects with stage 2 hypertension and/or LVH were started on antihypertensive medication at the outset.(15) When antihypertensive medication was indicated, the initial drug was lisinopril. The choice of a second agent, if needed, was at the discretion of the treating physician, except for the exclusion of the use of beta blockers or clonidine. Subjects were seen every 3 months to reassess BP control and to adjust antihypertensive therapy to achieve a target casual BP < 95th percentile.

Continuous variables are reported as mean ± SD or median and interquartile range, where appropriate. Discrete variables are reported as frequencies and percentages. Correlations were determined using Spearman rank correlation coefficients. Analysis of covariance for repeated measures implemented by SAS Proc Mixed was used to evaluate the treatment effect in parental assessments of executive function and internalizing and externalizing behaviors after 12-month of antihypertensive therapy. Group (hypertensive or control) was the between-subject factor and Time (baseline, follow-up) was the within-subject factor. Age was included as a covariate due to imbalance in this factor between subjects with and those without follow up assessments. Socioeconomic status (SES) was included as a covariate due to its potentially strong influence on neurocognitive test performance. The interaction between Group and Time was also investigated to test the difference between groups in the magnitude of change in scores. Similar analysis of covariance was used to evaluate the change in BRIEF and CBCL scores in the hypertensive group by baseline SBP load (≥ 50% vs. < 50%) and the presence of LVH, including age, race, BMI percentile, sex, and maternal education as covariates. Factors that were associated with the magnitude of improvement in BRIEF scores in hypertensive subjects were examined using linear mixed model. Missing data patterns were carefully examined. The SAS Proc Mixed procedure used for analysis provides consistent estimators under missing completely at random (MCAR) or missing at random (MAR) assumptions.(16, 17) These analyses incorporate all of the data that is present instead of listwise deleting subjects with missing values. Results are considered significant if p-value < 0.05. Analyses were performed with SAS (version 9.2, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Forty-seven of 63 (74%) subjects who were enrolled initially and who provided baseline data returned for the 12-month visit, including 22 (70%) of the hypertensive subjects and 25 (78%) of the normotensive controls (p = 0.57). The subjects who returned were younger than those who did not return (median age; 15 vs. 17 y, p = 0.015), but otherwise the subjects who returned were similar to the subjects who did not return in sex, race, percent obese, maternal education, annual household income, and baseline BRIEF summary scores (data not shown). The 22 hypertensive subjects and 25 control subjects with both baseline and 12-month follow-up data were similar in age, sex, race, maternal education, and household income. By definition, the hypertensive and control groups differed in baseline visit casual BP (Table I).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic characteristics of the control and subjects with hypertension who had both baseline and 12-month parental assessments.

| Characteristic | Control | Hypertension | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 25) | (N = 22) | ||

| Age, y* | 15 (13–16) | 15 (13–16) | 0.48 |

| Sex, % | 0.23 | ||

| Males | 52 | 73 | |

| Females | 48 | 27 | |

| Race (B/H/W), % | 0.33 | ||

| Black | 20 | 32 | |

| Hispanic | 0 | 4 | |

| White | 80 | 64 | |

| Obese, % | 56 | 55 | 0.99 |

| Prorated IQ^ | 102 ± 18 | 102 ± 11 | 0.98 |

| Maternal education, % | 0.78 | ||

| <High School | 4 | 5 | |

| High School | 52 | 54 | |

| College | 28 | 36 | |

| >College), | 16 | 5 | |

| Household Income, % | 0.51 | ||

| Low | 20 | 10 | |

| Low-Middle | 32 | 55 | |

| High-middle | 32 | 25 | |

| High | 16 | 10 | |

| Casual SBP index^ | 0.86 ± 0.06 | 1.04 ± 0.1 | < 0.001 |

| Casual DBP index^ | 0.75 ± 0.07 | 0.85 ± 0.14 | 0.004 |

median (IQR);

mean ± SD

Of the 22 hypertensive subjects, only one successfully improved BP with lifestyle modification alone. The 21 remaining hypertensive subjects required antihypertensive medication and were started on lisinopril. Five subjects required the addition of a second antihypertensive medication. Two of these subjects were prescribed amlodipine and 3 were prescribed a thiazide diuretic. One subject was switched from lisinopril to irbesartan due to fatigue and another was switched to amlodipine due to complaints of tachycardia with exercise. Comparison of ABPM variables at baseline and at 12 months confirmed successful treatment of hypertension. However, there was no change in BMI (Table II).

Table 2.

Hypertension group ABPM and BMI variables at baseline and after 12-months of antihypertensive therapy

| Characteristic^ | Baseline (N = 22) |

12-month (N = 22) |

P - value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daytime SBP, mm Hg | 138 ± 5 | 127 ± 6 | < 0.001 |

| Daytime DBP, mm Hg | 78 ± 9 | 68 ± 8 | < 0.001 |

| Nighttime SBP, mm Hg | 119 ± 7 | 103 ± 26 | 0.015 |

| Nighttime DBP, mm Hg | 61 ± 7 | 53 ± 14 | 0.008 |

| 24 hr SBP index | 1.04 ± 0.05 | 0.95 ± 0.06 | < 0.001 |

| 24 hr DBP index | 0.95 ± 0.11 | 0.84 ± 0.10 | < 0.001 |

| 24 hr SBP load, % | 60 ± 17 | 25 ± 19 | < 0.001 |

| 24 hr DBP load, % | 29 ± 25 | 10 ± 16 | < 0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 30.6 ± 8.1 | 31.0 ± 8.3 | 0.28 |

| BMI percentile | 89.1 ± 18 | 88.7 ± 18 | 0.52 |

Mean ± SD

At the baseline assessment subjects with hypertension had higher T-scores (poorer executive function) compared with control subjects with normal blood pressure on the BRIEF BRI (50.7 ± 10.6 vs. 44.1 ± 8.3, p = 0.01) and GEC (50.9 ± 12.6 vs. 44.8 ± 8.9, p = 0.01) scales, and showed a trend toward a difference on the BRIEF MI (52.3 ± 12.3 vs. 46.7 ± 11.5, p = 0.07) scale. Two subjects with hypertension had BRIEF GEC scores ≥ 65 (potentially clinically significant range) compared with none of the control subjects (p = 0.21). The hypertensive group also had higher T-scores (worse behavioral symptoms) compared with normotensive controls on the CBCL Internalizing scale (53.9 ± 13.4 vs. 46.1 ± 10.2, p = 0.01) but not the CBCL Externalizing scale (48.4 ± 9.4 vs. 44.5 ± 9.5, p = 0.11).

Within-group analyses showed subjects with hypertension significantly improved in BRIEF BRI, MI, and GEC summary scores at the 12-month reassessment compared with baseline. By contrast, BRIEF scores of control subjects with normal blood pressure did not change significantly from baseline to the 12-month assessment. In addition, the interaction between group and time was shown to be significant for both MI (p= 0.017) and GEC (p = 0.023), indicating the hypertensive group showed significantly greater change from baseline for the BRIEF MI and GEC scales compared with the change that occurred in the control group. Table III shows the summary statistics of baseline and 12-month follow-up scores of the hypertensive and control subjects and shows p-values for both within group and between group comparisons of change in scores provided by SAS Proc Mixed. In contrast to comparison of groups at baseline, there was no difference between the hypertensive and control group in T-scores of the BRI (46.2 ± 8.5 vs. 42.2 ± 3.4, p = 0.13), MI (46.3±7.7 vs. 45.0±8.6, p = 0.91), and GEC (46.1±8.3 vs. 43.4±7.1, p = 0.52) BRIEF summary scales at the 12-month assessment. The 2 subjects with hypertension and baseline BRIEF GEC scores in the clinically significant range both had improvement of their GEC scores into the normal range at the 12-month reassessment.

Table 3.

Within subject and between group comparisons of the change in T-score from baseline to the 12-month assessment.

| Parental Assessment |

Control N = 25 |

Hypertension N = 22 |

Between group comparison of change P – value* |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow up | Within group p- value* |

Baseline | Follow up | Within group p- value* |

||

| BRIEF | |||||||

| BRI | 42.1±3.3 | 42.2±3.4 | 0.55 | 50.3±9.4 | 46.2±8.5 | 0.01 | 0.11 |

| MI | 44.2±7.7 | 45.0±8.6 | 0.86 | 52.4±11.8 | 46.3±7.7 | <0.01 | 0.02 |

| GEC | 42.8±6.0 | 43.4±7.1 | 0.84 | 52.1±12.1 | 46.1±8.3 | <0.01 | 0.02 |

| CBCL | |||||||

| Internalizing | 45.2±9.5 | 43.4±10.5 | 0.24 | 54.9±12.7 | 52.2±11.9 | 0.12 | 0.72 |

| Externalizing | 42.2±8.2 | 41.8±8.5 | 0.50 | 48.1±7.8 | 45.5±9.4 | 0.08 | 0.39 |

Adjusted for age, maternal education, and household income

On post hoc analysis of BRIEF subscales, the subjects with hypertension showed decreased (improved) T-scores from baseline on Emotional Control (Δ = −6.0 ± 12.1, p = 0.03), Working Memory (Δ = −5.6 ± 8.6, p = 0.006), Plan/Organize (Δ = −4.3 ± 7.1, p = 0.009), and Monitor (Δ = −5.2 ± 9.3, p = 0.02) scales. There was no significant change between baseline and 12-month scores in Inhibit (Δ = −2.5 ± 7.6, p = 0.13), Shift (Δ = −1.9 ± 8.7, p = 0.33), Initiate (Δ = −3.8 ± 10.8, p = 0.12), or Organize Materials (Δ = −1.8 ± 7.5, p = 0.27). Control subjects did not show significant change in any of the BRIEF subscales (data not shown).

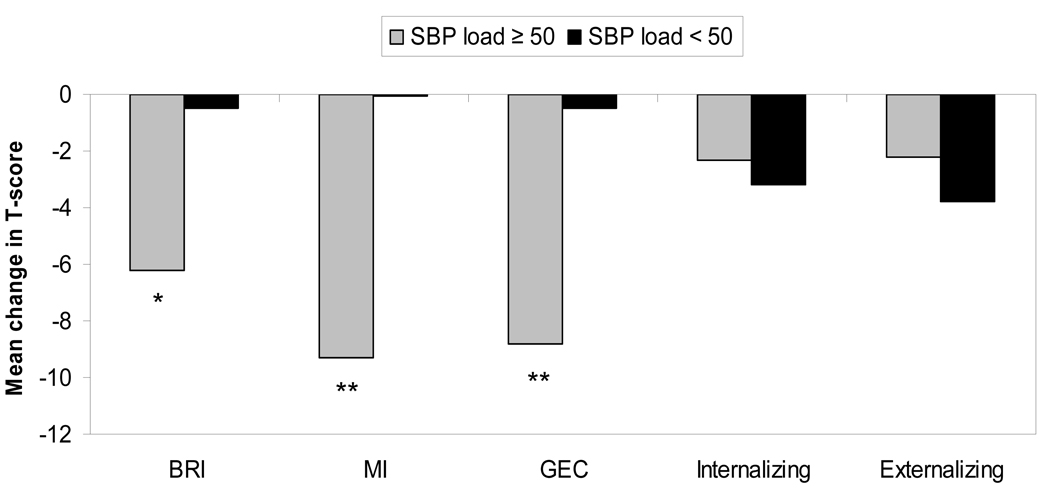

The change in BRIEF GEC scores in subjects with hypertension correlated significantly with higher baseline 24-hr SBP load (r = 0.42, p = 0.05) and higher baseline nighttime SBP (r = 0.52, p = 0.018) but not daytime SBP (r = 0.22, p = 0.33), daytime DBP (r = 0.16, p = 0.47), nighttime DBP (r = 0.33, p = 0.15), or 24-hr DBP load (r = 0.30, p = 0.17). There was no significant correlation between change in BRIEF summary scores and the magnitude of improvement in SBP load or any other ABPM variable (data not shown). The improvement in BRIEF summary scores in subjects with hypertension occurred largely in subjects with baseline SBP load ≥ 50%. By contrast, change in CBCL Internalizing or Externalizing score in subjects with hypertension did not differ by initial SBP load (Figure). LVH was present in 9 (41%) of the 22 subjects with hypertension. Of these 9 subjects with LVH, 8 (89%) had an initial SBP load of ≥ 50%. After adjustment for age, race, BMI percentile, sex, and maternal education, BRIEF GEC improved significantly from baseline in subjects with baseline LVH (Δ = −9.3, p = 0.01), whereas BRIEF GEC scores of subjects with hypertension without LVH did not change significantly from baseline (Δ = −3.3, p = 0.22). Change in CBCL Internalizing or Externalizing scores in patients with hypertension did not differ by the presence or absence of LVH (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Mean change in BRIEF and CBCL summary scores from baseline to 12-months in subjects with hypertension by initial 24-hr SBP load. Eight subjects had SBP load < 50% (black bars) and 14 had SBP load ≥ 50% (grey bars). Decrease in T-scores (negative change) represents improvement. By definition, a change in T-score of 10 equals 1 standard deviation. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005; within subject change, 12 month to baseline, adjusted for age, race, BMI percentile, sex, and maternal education.

Discussion

Our results showed that executive function improved after therapy in the subjects with hypertension, with the largest improvement occurring in the BRIEF MI index, approaching a full standard deviation change. The MI index reflects the subject’s ability to initiate, plan, organize, and sustain future-oriented problem solving in working memory.(12) Notably, the parent ratings of executive function of the control subjects did not change in the 12-month period. This finding suggests that the improvement seen in the subjects with hypertension was not due to an improvement with maturing by one year or due to a general improvement with reassessment. Furthermore, neither the subjects with hypertension nor the normotensive control subjects demonstrated significant improvement in parent ratings of Internalizing or Externalizing behaviors on the CBCL. This result suggests that the observed improvement in parent ratings of executive function on the BRIEF in the subjects with hypertension was not simply a false positive finding due to parent’s nonspecific emotional bias that their child improved with antihypertensive therapy, as an improvement in both BRIEF and CBCL scores might be expected if that were the case.

The observation that it was the subjects with hypertension most at risk for hypertensive target organ damage who had improvement in cognition with BP lowering lends support to the hypotheses that the neurocognitive deficits seen in children with primary hypertension represent hypertensive target-organ effects and that these deficits are, in part, reversible with antihypertensive therapy. In contrast to results on the BRIEF, the change in scores in the subjects with hypertension on the Internalizing and Externalizing scales of the CBCL did not differ by severity of baseline hypertension. The fact that the change in BRIEF scores differed by baseline hypertension severity and also that the CBCL results did not is further evidence that the improvement seen in parent ratings of executive function was not simply a false positive finding due to parent’s nonspecific feelings that their child improved with antihypertensive therapy.

Executive functions represent higher neurocognitive activities that involve skills needed for purposeful, goal-directed behavior, particularly during novel complex tasks. Theoretical components of executive function include problem solving, set shifting, planning, response inhibition, vigilance, and working memory.(12, 13, 19, 20) Assessment of executive functions with laboratory-based computer or paper-and-pencil tests has been challenging because such tests are typically administered in a structured, quiet, one-on-one testing environment, a setting where executive dysfunction may not manifest. As a result, standard laboratory-based tests tend to be insensitive to milder forms of executive dysfunction.(12, 13) The parent BRIEF rates behavioral correlates of executive function observed in the child’s everyday environment. Therefore, investigators suggest that the BRIEF has higher ecological validity and may be a more sensitive assessment of executive deficits in daily life compared with laboratory-based measures.(12, 21)

The current study has several limitations. The sample size was small with a relatively high drop out rate of both hypertensive and control subjects. However, except for younger age, the subjects who returned were similar in demographic characteristics and socioeconomic status to the subjects who did not return for the 12-month assessment. Age was controlled in our multivariate analyses. Furthermore, to minimize the potential selection bias due to drop outs, the intention to treat statistical analysis was performed to utilize all the available data. The mixed model used for analysis does not require data to be balanced and provides consistent estimation under MAR and MCAR. Second, the evaluation of executive function was limited to parental assessments. There were no laboratory performance-based measures of executive function to corroborate the results of the parental assessments. As noted above, however, performance-based measures are often relatively insensitive to mild executive dysfunction. Since parents were not blinded, they may have had biases that translated into results on the BRIEF that favored improvement with therapy. Even with the disparate results on the BRIEF and CBCL, both parent scales, suggests that nonspecific parent bias was not prominent, future studies using performance-based measures and using behavior ratings from non-parent observers (i.e., teachers) will serve to clarify this issue. Third, this was not a randomized controlled trial comparing treated and untreated hypertensive subjects. However, such a trial would have meant excluding subjects with stage 2 hypertension and those with LVH because national consensus guidelines recommend treating all such children with antihypertensive medication.(15) The results of the current study, however, suggest that it is those very children who should be included in studies of neurocognitive function and antihypertensive therapy. Furthermore, a randomized trial would have meant withholding antihypertensive medication from some hypertensive children for a full year, even those children who have already attempted therapeutic lifestyle modification for months or years prior to subspecialty referral. At the same time, a randomized trial with a shorter treatment period might not have allowed enough time for cognitive improvement. Last, the normotensive subjects did not have ABPM. Therefore, it is possible there may have been subjects in the normotensive control group who had masked hypertension. However, this limitation would have biased the results toward no difference between hypertensive and normotensive subjects.

The findings of improvement in executive function with antihypertensive therapy in children with primary hypertension need to be confirmed by larger studies with a more comprehensive evaluation of executive function.

Acknowledgments

We thank study coordinators, Laura Gebhardt and Tina Cabisca.

M.B.L. was supported, in part, by NIH grant 5K23HL080068-05 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. H.A. was supported, in part, by NIH grant 1K32 NS058756-02 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Waldstein SR, Snow J, Muldoon MF, Katzel LI. Neuropsychological consequences of cardiovascular disease. In: Tarter RE, Butters M, Beers SR, editors. Medical Neuropsychology. 2nd ed ed. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2001. pp. 51–83. p. 51. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waldstein SR, Jennings JR, Ryan CM, Muldoon MF, Shapiro AP, Polefrone JM, et al. Hypertension and neuropsychological performance in men: Interactive effects of age. Health Psychol. 1996;15:102–109. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.2.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waldstein SR. Hypertension and neuropsychological function: A lifespan perspective. Exp Aging Res. 1995;21:321–352. doi: 10.1080/03610739508253989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jennings JR. Autoregulation of blood pressure and thought: Preliminary results of an application of brain imaging to psychosomatic medicine. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:384–395. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000062531.75102.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muldoon MF, Waldstein SR, Jennings JR. Neuropsychological consequences of antihypertensive medication use. Exp Aging Res. 1995;21:353–368. doi: 10.1080/03610739508253990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller RE, Shapiro AP, King HE, Ginchereau EH, Hosutt JA. Effect of antihypertensive treatment on the behavioral consequences of elevated blood pressure. Hypertension. 1984;6(2 Pt 1):202–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lande MB, Adams H, Falkner B, Waldstein SR, Schwartz GJ, Szilagyi PG, et al. Parental assessments of internalizing and externalizing behavior and executive function in children with primary hypertension. J Pediatr. 2009;154:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soergel M, Kirschstein M, Busch C, Danne T, Gellermann J, Holl R, et al. Oscillometric twenty-four-hour ambulatory blood pressure values in healthy children and adolescents: A multicenter trial including 1141 subjects. J Pediatr. 1997;130:178–184. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70340-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: A report from the american society of echocardiography's guidelines and standards committee and the chamber quantification writing group, developed in conjunction with the european association of echocardiography, a branch of the european society of cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:1440–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daniels SR. Hypertension-induced cardiac damage in children and adolescents. Blood Press Monit. 1999;4:165–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wechsler D. WISC-IV administration manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gioia GA, Isquith PK, Guy SC, Kenworthy L. Behavior rating inventory of executive function. Lutz, FL: Pyschological Assessments Resources; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Straus E, Sherman EMS, Spreen O, editors. A compendium of neuropsychological tests: administration, norms, and commentary. 3rd ed ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual of the ASEBA school-aged forms and profiles. Burlington, VT: Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114:555–576. (Suppl 4th Report) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verbeke G, Molenberghs G. Linear mixed models for longitudinal data. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Urbina E, Alpert B, Flynn J, Hayman L, Harshfield GA, Jacobson M, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in children and adolescents: Recommendations for standard assessment: A scientific statement from the american heart association atherosclerosis, hypertension, and obesity in youth committee of the council on cardiovascular disease in the young and the council for high blood pressure research. Hypertension. 2008;52:433–451. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.190329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pennington BF, Ozonoff S. Executive functions and developmental psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1996;37:51–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1996.tb01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willcutt EG, Doyle AE, Nigg JT, Faraone SV, Pennington BF. Validity of the executive function theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analytic review. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1336–1346. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Denckla MB. The behavior rating inventory of executive function: Commentary. Child Neuropsychol. 2002;8:304–306. doi: 10.1076/chin.8.4.304.13512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahone EM, Koth CW, Cutting L, Singer HS, Denckla MB. Executive function in fluency and recall measures among children with tourette syndrome or ADHD. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2001;7:102–111. doi: 10.1017/s1355617701711101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waber DP, Gerber EB, Turcios VY, Wagner ER, Forbes PW. Executive functions and performance on high-stakes testing in children from urban schools. Dev Neuropsychol. 2006;29:459–477. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2903_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson VA, Anderson P, Northam E, Jacobs R, Catroppa C. Development of executive functions through late childhood and adolescence in an australian sample. Dev Neuropsychol. 2001;20:385–406. doi: 10.1207/S15326942DN2001_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Luca CR, Wood SJ, Anderson V, Buchanan JA, Proffitt TM, Mahony K, et al. Normative data from the CANTAB. I: Development of executive function over the lifespan. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2003;25:242–254. doi: 10.1076/jcen.25.2.242.13639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]