Abstract

PURPOSE

Describe total pain theory and apply it to research and practice in advanced heart failure (HF).

SOURCE OF INFORMATION

Total pain theory provides a holistic perspective for improving care, especially at the end of life. In advanced HF, multiple domains of well-being known to influence pain perception are adversely affected by declining health and increasing frailty. A conceptual framework is suggested which addresses domains of well-being identified by total pain theory.

CONCLUSION

By applying total pain theory, providers may be more effective in mitigating the suffering of individuals with progressive, life-limiting diseases.

Search terms: Conceptual framework, palliative care, psychological well-being, spirituality, symptom

Pain in Heart Failure

Heart failure (HF) is the only cardiovascular disease in the United States that is increasing in incidence and prevalence. Approximately 5.3 million Americans live with HF (American Heart Association, 2008). While incredible progress has been made to improve the care and longevity of individuals suffering with HF, many will experience decreased vitality and deterioration of their quality of life as their disease progresses (Boyd et al., 2004; Levenson, McCarthy, Lynn, Davis, & Phillips, 2000; Walke, Gallo, Tinetti, & Fried, 2004). While dyspnea and fatigue are usually considered the hallmarks of advancing HF, awareness is growing that pain may also present a significant burden (Addington-Hall, Rogers, McCoy, & Gibbs, 2003; Godfrey, Harrison, Friedberg, Medves, & Tranmer, 2007), interfere with goals of self-management (Godfrey et al., 2007), and be associated with increased mortality for individuals with HF (Ekman, Cleland, Swedberg, et al., 2005). Studies in HF populations have variously reported the pain prevalence between 18% and 75% (Godfrey et al., 2007; Goebel et al., 2009; Levenson et al.; McCarthy, Lay, & Addington-Hall, 1996; Norgren & Sorensen, 2003; Sullivan, Levy, Russo, & Spertus, 2004).

While empirical studies describing pain in advanced HF are lacking, the literature provides support that patients with this debilitating, progressive disease suffer negative physical, spiritual, psychological, and social sequelae (Boyd et al., 2004; Levenson et al., 2000; Sullivan, Levy, Russo, & Spertus, 2004). While several theories of pain are available, the most salient theory for the assessment and treatment of pain in HF patients is Saunders’ theory of total pain, which emphasizes physical, spiritual, emotional, and social dimensions of pain (Saunders & Baines, 1984). We suggest a conceptual model with which to apply the theory of total pain to clinical practice and research in advanced HF.

Pain Theories, Past and Present

Pain theories have evolved over time, but only Saunders’ theory of total pain incorporates spiritual dimensions into understanding and managing suffering (Clark, 1999). In the early part of the 20th century, a purely positivist approach on the study of pain focused on the physiological signals sent to the brain from noxious stimuli within the body. As the science of pain evolved, acute and chronic pain were differentiated and conceptualized as having different etiologies and treatments (Clark, 1999). Acute pain is usually conceptualized as “corrective” and positive because it stimulates the individual to seek treatment and draws attention to the injury. Chronic pain, in contrast, is generally viewed as without adaptive purpose or meaning (Clark, 1999; McGuire, 2006). The attributes of acute, chronic, and total pain are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of Acute, Chronic, and Total Pain

| Acute pain | Chronic pain | Total pain | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conceptualization | Predominately conceptualized as corrective and positive. Usually of short duration (<6 months), often described in sensory terms. May be associated with autonomic responses. | Generally conceptualized as dysfunctional and without adaptive purpose. Usually of long duration (>6 months) or 1 month beyond the normal end of the condition causing the pain. | The sum total of suffering including physical, spiritual, psychological, and social components. It has no comforting explanation and there is no foreseeable end. |

| Etiologies | Usually has an identifiable cause with an immediate onset. Generally considered useful, reversible, and controllable. | May or may not have an identifiable cause, is associated with depression and withdrawal. | The product of multiple sensory and affective insults, which result in severe suffering. |

| Treatments | Analgesics | Analgesics, complementary medicine | Holistic approach addressing the multiplicity of issues |

| Descriptions | May be described in sensory terms such as sharp, stabbing, or shooting. | May be described in affective terms (sickening, hateful) and as continuous, persistent, or recurrent. | “Its all pain” (Saunders & Baines, 1984). |

| Examples | Childbirth, kidney stones, bone fractures | Low back pain, diabetic neuropathy | Advanced heart failure, liver disease, COPD, terminal cancer |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Although an early understanding of pain emphasizes the contribution of physical illness, later theories recognize the influence of the psyche on pain perception. Melzack and Wall’s gate control theory (1965) conceptualized pain as primarily a physiological event with the potential for psychological factors to influence perception. Their pain model suggests that psychological factors such as past experiences and emotions influence pain perception response by acting centrally to mitigate or exacerbate pain experience (Melzack & Wall). While innovative in its recognition of the role of the psyche on pain perception, the theory lacks the holistic view of multiple domains as influencing and being influenced by pain perception. The limitations to existing pain theories support the need for new approaches to understand and manage the pain and suffering experienced during life-limiting diseases.

Theory of Total Pain

Dame Cicely Saunders first articulated the theory of total pain to describe the sum of suffering (physical, spiritual, psychological, and social) experienced by patients faced with advanced disease and terminal illness (Clark, 1999). The theory of total pain has, as its genesis, Saunders’ work with managing pain for terminally ill cancer patients. Her principles of addressing holistically the needs of patients set the stage for palliative care among patients with life-limiting diseases (Clark, 2002). Saunders’ total pain theory recognizes the interplay between the psyche and the physical sensations of pain (Saunders & Baines, 1984).

To fully appreciate the theory of total pain, it is useful to consider the background of its author. In 1967, Saunders established the first modern hospice, St. Christopher’s Hospice (Ferrell & Coyle, 2001). For most clinicians involved in palliative care, she is viewed not only as the founder of the modern hospice movement, but also as the individual who revolutionalized the care of the dying patient. Saunders was educated and practiced as a nurse, then a medical almoner (social worker), and, finally, a physician. Consequently, over the years, her work has resonated with a wide range of clinicians and researchers interested in improving the care of individuals with progressive or terminal disease.

Saunders described herself as “ … a doctor who isn’t in a hurry” (Clark, 1999). She was well known for her portable tape recorder that she used to audio-record conversations with patients about their attitudes toward their illness. As she sat at the bedside, she would play back the recording; she found the practice very revealing, both for the patient and herself. This extended discourse with her patients provided the foundation for her theory of total pain (Clark, 1999). While Saunders and other purists may be reticent to label her methodology as qualitative, these narratives provided the genesis for her subsequent papers and the development for the theory of total pain. Patient narratives are a prominent component of a current therapy by Chochinov and colleagues (2005) to diminish spiritual distress (coined “dignity therapy”) (Chochinov et al.). These researchers audio-tape and transcribe patients’ and families’ discussions of memories or topics they want their families or friends to remember most. This therapy, while in its infancy, has demonstrated promise to mitigate spiritual suffering experienced by individuals facing end-of-life issues.

Saunders’ theory developed qualitatively out of patient narratives from the ground up. Its uniqueness lies in the recognition that individuals may experience distress in multiple domains and that this distress influences and is influenced by physical pain. Physical pain may contribute to and become entangled with spiritual, psychological, and social distress. Failure to recognize the uniqueness and contribution of each domain to the overall well-being of the individual may lead to extensive suffering. Saunders identifies the contribution of the psychological domain to overall well-being when she states, “Mental distress may be perhaps the most intractable pain of all” (Saunders, 1963). The extent of psychological distress experienced by some HF patients is reflected in studies which report the incidence of anxiety and depression among HF patients and its effects on mortality (Jiang et al., 2007; Richardson, 2003). Psychological distress, which may be common in advanced HF (Artinian, 2003; Boyd et al., 2004), may contribute to the overall experience of total pain. Recent research suggests that many patients do not experience psychological distress or even consider advanced HF as a terminal condition. In a qualitative study by Willems, Hak, Visser, and Van der Wal (2004), most patients did not think about death at all or only thought about it during acute exacerbations (Willems et al.).

Assessing and understanding the patient’s total pain experience is similar to the activity of peeling an onion. Clinicians must assess each layer, looking beneath all layers to understand the genesis of the patient’s experience. In his analysis of Saunders work, Clark (1999) chronicles the evolution of the theory of total pain. Saunders grew to believe that pain in advanced illness was qualitatively different from acute pain. The experience was more complex, not simply the acute pain prolonged (Clark, 1999). She viewed the pain of advanced disease as multifactorial, as a situation, not an event (Saunders, 1967). Current research examining patients’ experiences supports these views. In a qualitative study examining the experiences of advanced HF patients and families living at home, uncertainty with prognosis and treatment aims contributed to social isolation and dependency (Boyd et al., 2004).

In a prospective study, Carels and colleagues (2004) found that psychosocial functioning (including anxiety and social conflict) was associated with HF physical symptoms including chest pain or heaviness and shortness of breath.

The theory of total pain as a situation is best understood by reflecting back on the nature of pain and suffering. When pain extends beyond physical sensations to involve the spiritual, psychological, and social domains, it threatens the integrity of the individual. Some clinicians identify this threat to integrity as suffering, and hence, conclude that total pain is a set of circumstances (i.e., a situation) and not an event (Cassell, 1982). This phenomena is more likely to occur when individuals report pain as overwhelming, out of control, without meaning (the cause is unknown), or without end (Saunders & Baines, 1984). Individuals may writhe from the pain of childbirth or kidney stones, yet this pain is distinguished from suffering in that it has an identifiable cause and identifiable end. Total pain, in contrast, poses a threat to the integrity of the individual by its potential involvement of multiple domains and the inherent difficulty in reducing total pain to discreet parts. Total pain results from injuries to the integrity of the individual; this loss of integrity may be expressed by sadness, anger, rage, withdrawal, or yearning (Cassell). The theory of total pain is especially applicable to HF because physical pain is rarely considered a critical component of advanced HF (Addington-Hall et al., 2003; Godfrey, Harrison, Medves, & Tranmer, 2006). However, the experiences of symptom burden, loss of purpose, and social isolation are well documented and almost certainly contribute to the overall sense of total pain (Boyd et al., 2004; Ekman, Cleland, Andersson, & Swedberg, 2005; Walke et al., 2004).

A Conceptual Model Applying Total Pain Theory

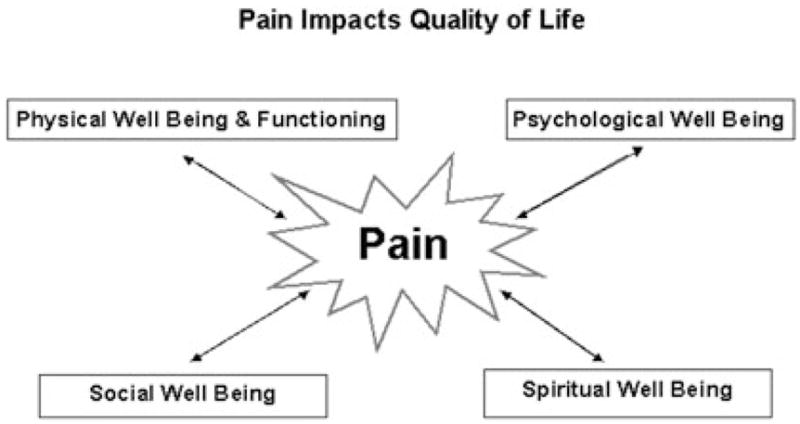

To direct future investigations and improve care, Ferrell, Grant, Padilla, Vermuri, and Rhiner (1991) developed a conceptual model which holistically reflects the salient domains of total pain theory (Ferrell et al.). Ferrell’s model, “pain impacts dimensions of quality of life,” draws from Saunders’ theory of total pain and is based on a bidirectional relationship in which domains of well-being (physical, spiritual/existential, psychological, and social) influence and are influenced by pain perception (Figure 1). This conceptual model is especially useful for the investigation and management of pain in progressive diseases such as HF because it includes multiple, separate domains consistent with both prevailing health-related quality of life (HRQOL) frameworks and current clinical practice goals in palliative care. In fact, the “pain impacts dimensions of quality of life” model is compatible with the Scopes and Standards of Holistic Nursing Practice (Mariano, 2007), the Clinical Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care developed by the National Consensus Project (2009), the Consensus Statement for Palliative and Supportive Care in Advanced Heart Failure (Goodlin et al., 2004), and the National Institutes of Health State of the Science Conference Statement [for] Improving End-of-Life Care (National Institutes of Health, 2004).

Figure 1.

Pain impacts quality of life. Adapted with permission from Haworth Press (Ferrell, Grant, Padilla, Vermuri, & Rhiner, 1991).

As with the theory of total pain, a holistic approach to the assessment and treatment of pain is foundational to Ferrell’s model. The model demonstrates that total pain domains, palliative care domains, and health-related quality of life domains are analogous concepts which complement one another to provide a consistent foundation for the inquiry and treatment of pain for individuals during declining health and function common in advanced HF. This model incorporates the following domains.

Pain

Ferrell and colleagues (1991) describe the potential for pain to overwhelm the individual and consume every aspect of life. Possibly, the most recognized definition for pain is McCaffery and Pasero’s (2002), “Whatever the experiencing person says it is, occurring whenever s/he states it does” (McCaffery & Pasero, p. 17).

The International Association for the Study of Pain and the American Pain Society define pain as: “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of that damage” (McCaffery & Pasero, 2002, p. 17). These definitions allow the conceptualization of pain to include multiple domains and recognize its subjective nature. Pain is acknowledged for its complexity and ability to affect physical and psychosocial functioning. According to these definitions, pain cannot always be determined by the extent of tissue damage. In chronic, nonmalignant pain, patients may report severe pain without evidence of tissue damage. In contrast, patients suffering from major trauma may report less severe pain than is expected for the extent of damage to tissues (McCaffery & Pasero). Ferrell and Coyne (2008) state that pain that is unrecognized or ignored creates suffering.

Physical Well-Being and Symptoms

Functional ability, strength/fatigue, sleep and rest, nausea, appetite, constipation, and symptoms are facets of physical well-being identified in Ferrell’s conceptual model (Ferrell et al., 1991). The National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care (2009) identifies pain and symptom management as critical aspects to improve the physical well-being of patients facing life-threatening illness (National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care). Advanced HF patients are known to experience a wide number of distressing physical symptoms that may influence their perception of pain, including dyspnea, fatigue, confusion, incontinence, anxiety, and nausea (Addington-Hall et al., 2003; Levenson et al., 2000; Pantilat & Steimle, 2004; Walke et al., 2004; Zambroski, Moser, Bhat, & Zeigler, 2005). Research suggests that a number of these symptoms may be poorly controlled at the end of life (Levenson et al.; Norgren & Sorensen, 2003), potentially contributing to the experience of total pain. The prevalence of pain as a symptom in HF varies considerably across studies from 5% in a prospective HF study of depression and symptoms (Sullivan et al., 2004) to 75% in a retrospective study using chart abstraction (Norgren & Sorensen). Clearly, a better understanding of the experience of pain is warranted.

Spiritual/Existential Well-Being

Spiritual/existential well-being may not necessarily refer to religious experiences, but to a range of beliefs that become more important as individuals face declining function and their own mortality (Westlake & Dracup, 2001). Spiritual/existential well-being is defined as the propensity to make meaning through a sense of relatedness to dimensions that transcend the self (Reed, 1987). In a qualitative study, Westlake and Dracup identified the development of regret, and a search for meaning and hope as recurrent themes for patients with advanced HF adjusting to their disease progress (Westlake & Dracup). Saunders proposes that a feeling of meaninglessness, that neither oneself nor the universe itself has permanence or purpose, is an indication of spiritual pain or a lack of spiritual well-being (Saunders & Baines, 1984). When life-limiting disease constricts the ability to make meaning from one’s activities, it is critical to ask patients, “What makes you happy in this part of your life?” (Goldstein & Lynn, 2006, p. 13). By clarifying personal goals, patients and families may discover meaning and purpose, and improve spiritual well-being throughout the HF trajectory.

Psychological Well-Being

Psychological well-being is a complex concept that influences and is influenced by pain perception in many patient populations (Carels et al., 2004; Carr, Nicky Thomas, & Wilson-Barnet, 2005; Roth, Geisser, Theisen-Goodvich, & Dixon, 2005). Anxiety, depression, enjoyment/leisure, pain distress, happiness, and fear are variables frequently measured to reflect this domain in patients with advanced illness. Extensive research and clinical experience support the influence of the psychological domain on physical functioning (Carels et al.; De Jong, Moser, & Chung, 2005; Sullivan et al., 2004), pain (Carels et al.), and quality of life for HF patients (Carels, 2004; De Jong et al.). Depression, with its significant prevalence in advanced HF, deters efforts to palliate symptoms in life-limiting disease (King, Heisel, & Lyness, 2005). Moreover, depression in advanced disease is strongly correlated with requests for hastened death (Breitbart et al., 2000).

The management of depression may be especially troublesome in palliative care because many of the symptoms of depression overlap with terminal disease. Traditional treatments for depression may not be tolerated in frail elderly patients (King et al., 2005). Some antidepressant medications are contraindicated in HF, while the safety of others has not been confirmed (Addington-Hall et al., 2003). Some psychological therapies, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, may help HF patients accept the multiple losses associated with disease progression and assist in identifying new sources of enjoyment (Dekker, 2008). The effectiveness of pain management is contingent on addressing and mitigating the psychological distress from the progressive nature of advanced HF in order to prevent the development of total pain.

Social Well-Being

Social well-being refers to the level of comfort an individual feels about his/her relationships with friends, family, and significant others. Caregiver burden, roles and relationships, affection/sexual function, and appearance are important aspects of social well-being (Ferrell et al., 1991). Social support, which is closely correlated with social well-being, is defined as resources (both physical and psychological) that are provided by other individuals for the benefit of the recipient (Cohen & Syme, 1985). Social support influences pain perception and symptomatology in a number of populations including HF (Carels et al., 2004; Evers, Kraaimaat, Geenen, Jacobs, & Bijlsma, 2003; Fink & Gates, 2001; Flor & Rudy, 1989; Jamison & Virst, 1990; Kimmel, Emont, Newman, Danko, & Moss, 2003). Unfortunately, some treatments for HF, such as diuretic therapy and low sodium diets, may limit social interactions and contribute to social isolation. Socially isolated HF patients are more likely to experience depression (Koenig, 1998), increase rehospitalization rates (Moser, Doering, & Chung, 2005), and increase mortality (Krumholz et al., 1998). A few studies suggest that HF patients may lack social support services, which are more available to other terminally ill patients such as cancer patients (Boyd et al., 2004; Horne & Payne, 2004; Murray, Boyd, Kendall, Worth, & Calsen, 2002).

Ferrell’s model reflects the theory of total pain and includes assessment of physical, spiritual, psychological, and social domains, and has the unique ability to serve as a foundation for both research and practice. The comprehensive nature of the model supports qualitative and quantitative approaches to the investigation of pain in advanced HF (Ferrell et al., 1991). Qualitative inquiry of total pain is closely tied to the patient’s narrative and seeks to understand the experience of pain in a multifaceted way. The theory of total pain and Ferrell’s model encourages assessment and management of pain by recognizing the need for a holistic approach to understand pain from an insider’s perspective. Several studies employing qualitative methodology have sought to describe the experiences of HF patients. They articulate patient, family, caregiver, and provider perceptions to exemplify the suffering and demonstrate the inadequacies of current medical management (Hanratty, Hibbert, & Mair, 2002; Murray et al., 2002; Willems et al., 2004). These studies suggest a need for improved support services, provider–patient communication, and pain and symptom management. Because this model identifies significant concepts for measurement, quantitative inquiry is also supported. Instruments may be chosen to measure the separate domains of total pain, providing the opportunity to measure the effectiveness of targeted interventions aimed at mitigating the suffering experienced by many HF patients as they approach the end of life.

Conclusion

The theory of total pain, as articulated by Saunders, is especially salient for the investigation and management of pain in advanced HF because of its ability to holistically assess and manage suffering. Ferrell and colleagues’ model, “pain impacts the dimensions of quality of life” (1991), operationalizes total pain theory for use in research and practice. Empirical evidence supports the importance of identifying and addressing the physical, psychological, spiritual, and social burdens of illness. Healthcare professionals are called to consistently and comprehensively address pain to improve quality of life for patients and families facing the debilitating progression of advanced HF.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Karl Lorenz is supported by an HSR&D Advanced Career Development Award of the Veterans Administration Healthcare System.

Contributor Information

Joy R. Goebel, Department of Nursing, California State University, Long Beach, CA.

Lynn V. Doering, School of Nursing, University of California, Los Angeles, CA.

Karl A. Lorenz, RAND Corporation, Assistant Professor of Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, and with the Veterans Integrated Palliative Program, Veterans Administration Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System.

Sally L. Maliski, School of Nursing, University of California, Los Angeles, CA.

Adeline M. Nyamathi, School of Nursing, University of California, Los Angeles, CA.

Lorraine S. Evangelista, School of Nursing, University of California, Los Angeles, CA.

References

- Addington-Hall J, Rogers A, McCoy A, Gibbs J. Heart disease. In: Morrison R, Meier D, Capello C, editors. Geriatric palliative care. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 110–122. [Google Scholar]

- American Heart Association. Disease and stroke statistics–2008 update. Dallas, TX: Author; 2008. [Accessed July 5, 2009]. from http://www.americanheart.org/downloadable/heart/1200078608862HS_Stats%202008.final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Artinian N. The psychosocial aspects of heart failure: Depression and anxiety can exacerbate the already devastating effects of the disease. American Journal of Nursing. 2003;103(12):32–42. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200312000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd KJ, Murray SA, Kendall M, Worth A, Frederick Benton T, Clausen H. Living with advanced heart failure: A prospective, community based study of patients and their carers. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2004;6(5):585–591. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2003.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, Kaim M, Funesti-Esch J, Galietta M, et al. Depression, hopelessness, and desire for hastened death in terminally ill patients with cancer. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284(22):2907–2911. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.22.2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carels R. The association between disease severity, functional status, depression and daily quality of life in congestive heart failure patients. Quality of Life Research. 2004;13(1):63–72. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000015301.58054.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carels RA, Musher-Eizenman D, Cacciapaglia H, Perez-Benitez CI, Christie S, O’Brien W. Psychosocial functioning and physical symptoms in heart failure patients: A within-individual approach. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2004;56(1):95–101. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr E, Nicky Thomas V, Wilson-Barnet J. Patient experiences of anxiety, depression and acute pain after surgery: A longitudinal perspective. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2005;42(5):521–530. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassell E. Suffering and medicine. New England Journal of Medicine. 1982;306(11):639–645. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198203183061104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, Kristjanson LJ, McClement S, Harlos M. Dignity therapy: A novel psychotherapeutic intervention for patients near the end of life. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(24):5520–5525. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark D. “Total pain,” disciplinary power and the body in the work of Cicely Saunders, 1958–1967. Social Science & Medicine. 1999;49(6):727–736. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark D. Between hope and acceptance: The medicalisation of dying. British Medical Journal. 2002;324(7342):905–907. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7342.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Syme S. Issues in the study of social support and health. San Francisco: Academic Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker RL. Cognitive behavioral therapy for depression in patients with heart failure: A critical review. Nursing Clinics of North America. 2008;43(1):155–170. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong M, Moser D, Chung M. Predictors of health status for heart failure patients. Progress in Cardiovascular Nursing. 2005;20(4):155–162. doi: 10.1111/j.0889-7204.2005.04649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman I, Cleland JGF, Andersson B, Swedberg K. Exploring symptoms in chronic heart failure. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2005;7(5):699–703. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman I, Cleland JGF, Swedberg K, Charlesworth A, Metra M, Poole-Wilson PA. Symptoms in patients with heart failure are prognostic predictors: Insights from COMET. Journal of Cardiac Failure. 2005;11(4):288–292. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers AWM, Kraaimaat FW, Geenen R, Jacobs JWG, Bijlsma JWJ. Pain coping and social support as predictors of long-term functional disability and pain in early rheumatoid arthritis. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2003;41(11):1295–1310. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(03)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell B, Coyle N. Textbook of palliative nursing. New York: Oxford Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell B, Coyle N. The nature of suffering and the goals of nursing. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell B, Grant M, Padilla G, Vermuri S, Rhiner M. The experience of pain and perceptions of quality of life: Validation of a conceptual model. Hospice Journal. 1991;7(3):9–23. doi: 10.1080/0742-969x.1991.11882702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink R, Gates R. Pain assessment. In: Ferrell B, Coyle N, editors. Textbook of palliative nursing. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 53–75. [Google Scholar]

- Flor HDT, Rudy T. Relationship of pain impact and significant other reinforcement of pain behaviors: The mediating role of gender, marital status, and marital satisfaction. Pain. 1989;38(1):45–50. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey C, Harrison MB, Medves J, Tranmer JE. The symptom of pain with heart failure: A systematic review. Journal of Cardiac Failure. 2006;12(4):307–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey CM, Harrison MB, Friedberg E, Medves JM, Tranmer JE. The symptom of pain in individuals recently hospitalized for heart failure. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2007;22(5):368–374. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000287035.77444.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebel JR, Doering LV, Evangelista LS, Nyamathi AM, Maliski SL, Asch SM, et al. A comparative study of pain in heart failure and non-heart failure veterans. Journal of Cardiac Failure. 2009;15(1):24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein N, Lynn J. Trajectory of end-stage heart failure: The influence of technology and implications for policy change. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 2006;49(1):10–18. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2006.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodlin S, Hauptman P, Arnold R, Grady K, Hersheberger R, Kunter J, et al. Consensus statement: Palliative and supportive care in advanced heart failure. Journal of Cardiac Failure. 2004;10(3):200–209. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanratty B, Hibbert D, Mair F. Doctors’ perception of palliative care for heart failure: Focus group. British Medical Journal. 2002;325:581–585. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7364.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne G, Payne S. Removing the boundaries: Palliative care for patients with heart failure. Palliative Medicine. 2004;18(4):291–296. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm893oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamison R, Virst K. The influence of family support on chronic pain. Behavioral Research Therapy. 1990;28:283–287. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W, Kuchibhatla M, Clary GL, Cuffe MS, Christopher EJ, Alexander JD, et al. Relationship between depressive symptoms and long-term mortality in patients with heart failure. American Heart Journal. 2007;154(1):102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel P, Emont S, Newman J, Danko H, Moss A. ESRD patient quality of life: Symptoms, spiritual beliefs, psychosocial factors, and ethnicity. American Journal of Kidney Disease. 2003;42(4):713–721. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00907-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King D, Heisel M, Lyness J. Assessment and psychological treatment of depression in older adults with terminal or life-threatening illness. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2005;12(3):339–353. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG. Depression in hospitalized older patients with congestive heart failure. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1998;20(1):29–43. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(98)80001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumholz HM, Butler J, Miller J, Vaccarino V, Williams CS, Mendes de Leon CF, et al. Prognostic importance of emotional support for elderly patients hospitalized with heart failure. Circulation. 1998;97(10):958–964. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.10.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson J, McCarthy E, Lynn J, Davis R, Phillips R. The last six months of life for patients with congestive heart failure. Journal of American Geriatric Society. 2000;48(Suppl 5):S101–S109. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariano C. Holistic nursing as a specialty: Holistic nursing–Scope and standards of practice. Nursing Clinics of North America. 2007;42(2):165–188. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaffery M, Pasero C. Pain: Clinical manual. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy M, Lay M, Addington-Hall J. Dying from heart disease. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of London. 1996;30(4):325–328. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire L. Pain, the fifth vital sign. In: Ignatavicius D, Workman M, editors. Medical surgical nursing critical thinking for collaborative care. 5. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2006. pp. 63–90. [Google Scholar]

- Melzack R, Wall P. Pain mechanisms: A new theory. Science. 1965;150:971–975. doi: 10.1126/science.150.3699.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser D, Doering L, Chung M. Vulnerabilities of patients recovering from an exacerbation of chronic heart failure. American Heart Journal. 2005;150(5):984e.8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray S, Boyd K, Kendall M, Worth ARB, Calsen H. Dying of lung cancer or cardiac failure: Prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their careers in the community. British Medical Journal. 2002;325:929–934. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7370.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care. (2) 2009 Retrieved July 5, 2009, from http://www.nationalconsensusproject.org.

- National Institutes of Health. National Institutes of Health state-of-the-science conference statement improving end-of-life care; 2004. Retrieved July 5, 2009, from http://consensus.nih.gov/2004/2004EndOfLifeCareSOS024html.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Norgren L, Sorensen S. Symptoms experienced in the last six months of life in patients with end-stage heart failure. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2003;2:213–217. doi: 10.1016/S1474-5151(03)00059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantilat SZ, Steimle AE. Palliative care for patients with heart failure. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291(20):2476–2482. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.20.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed P. Religiousness among terminally ill adults. Resource Nursing Health. 1987;9:35–41. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770090107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson L. Psychosocial issues in patients with congestive heart failure. Progress in Cardiovascular Nursing. 2003;18(1):19–27. doi: 10.1111/j.0889-7204.2003.00835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth RS, Geisser ME, Theisen-Goodvich M, Dixon PJ. Cognitive complaints are associated with depression, fatigue, female sex, and pain catastrophizing in patients with chronic pain. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2005;86(6):1147–1154. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders C. Care of the dying. Current Medical Abstracts for Practitioners. 1963;3(2):77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders C. The management of terminal illness. London: Hospital Medicine Publications; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders C, Baines M. Living with dying. 2. New York: Oxford University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan M, Levy W, Russo J, Spertus J. Depression and health status in patients with advanced heart failure: A prospective study in tertiary care. Journal of Cardiac Failure. 2004;10(5):390–396. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walke L, Gallo W, Tinetti M, Fried T. The burden of symptoms among community-dwelling older persons with advanced chronic disease. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2004;164:2321–2324. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.21.2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westlake C, Dracup K. Role of spirituality in adjustment of patients with advanced heart failure. Progress in Cardiovascular Nursing. 2001;16(3):119–125. doi: 10.1111/j.0889-7204.2001.00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willems D, Hak A, Visser F, Van der Wal G. Thoughts of patients with advanced heart failure on dying. Palliative Medicine. 2004;18:564–572. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm919oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambroski C, Moser D, Bhat G, Zeigler C. Impact of symptom prevalence and symptom burden on quality of life in patients with heart failure. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2005;4(3):198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]