Abstract

Background

A randomized trial of male circumcision (MC) was conducted among HIV-infected males to test the hypothesis that MC would reduce HIV transmission to female sexual partners.

Methods

This randomized, unblinded trial, conducted in Rakai District, Uganda, enrolled 922 uncircumcised, HIV-infected asymptomatic men aged 15–49 with CD4 counts ≥350. Men were randomly assigned to immediate circumcision (intervention) or circumcision delayed for 24 months (control). Concurrently enrolled HIV-negative female partners were followed up at 6, 12 and 24 months, to assess HIV acquisition by male MC assignment (primary outcome). An intention-to-treat analysis assessed women’s HIV acquisition using survival analysis and Cox proportional hazards modeling. The trial was registered in the Clinical Trials.gov Protocol Registration System (NCT00124878).

Findings

The trial was terminated for futility. Ninety three concurrently enrolled female partners of intervention arm men and 70 partners of control arm men provided follow up data. Cumulative probabilities of female HIV infection at 24 months were 21.7% (95% CI 12.7–33.4) in the intervention arm and 13.4% (95% CI 6.7–25.8) in the control arm (adjusted hazard ratio= 1.49, 95% CI 0.62–3.57, p = 0.368). At 6 months, intervention arm male-to-female transmission in couples who resumed intercourse ≥5 days prior to certified surgical wound healing was 27.8% (5/18), compared to 9.5% in couples who abstained longer post-surgically (6/63, p = 0.06) and 7.9% in control arm couples (5/63, p = 0.04)

Interpretation

Circumcision of HIV-infected men did not reduce HIV transmission to female partners over 24 months, and transmission risk may be increased with early post-surgical resumption of intercourse. Longer-term effects could not be assessed. Post surgical sexual abstinence and subsequent consistent condom are essential for HIV prevention.

Keywords: Male circumcision, randomized trial, HIV-infected men, female HIV acquisition, Uganda

Introduction

Three trials of male circumcision (MC) in HIV-negative men, including one conducted in Rakai, Uganda, showed that circumcision reduced male HIV acquisition by 50–60 (1–3) and MC is now recommended for HIV prevention in men.(4) As programs scale up, it is inevitable that HIV-positive men will also request MC, partly to avoid stigmatization. We previously reported that MC was safe and reduced rates of genital ulcer disease (GUD) in asymptomatic HIV-infected men with CD4 cell counts ≥350.(5,6). Given the social considerations and clinical findings, WHO/UNAIDS has recommended that surgery be provided on request to HIV-infected men unless there are medical contraindications.(4)

A prior observational study in HIV-discordant couples in Rakai suggested a lower rate of male-to-female HIV transmission from circumcised HIV-infected men, particularly if their HIV viral load below 50,000 copies/mL.(7) Two other observational studies also reported an association between MC and reduced female HIV risk.(8,9)

In parallel to the trial of MC in HIV-negative men referenced above, we conducted a randomized trial of MC in HIV-infected men and enrolled their female partners. Trial objectives were to assess MC safety and efficacy for STI prevention in HIV-infected men, (5,6) and to test the hypothesis that MC would reduce HIV and STI transmission from HIV-infected men to their HIV-uninfected female sexual partners. This paper reports trial results in the women partners of HIV-infected men, , including HIV incidence and rates of STI symptoms and vaginal infections.

Methods

The trial was conducted in Rakai District, Uganda, between 2003 and 2006.

Male participation

Trial procedures for HIV-infected men, including consent, randomization, and data and sample collection, were the same as those previously reported in the MC trial of HIV-negative men;(3) and are briefly summarized here. Men received an explanation of study goals and provided written informed consent for screening and HIV testing. Prior to screening and throughout the trial, men were offered HIV results, counseling and information on HIV prevention. They were informed that the effects of MC on HIV/STI transmission to women partners were unknown and that adherence to safe sexual practices was imperative.

In all, 1,151 HIV-positive eligible uncircumcised men were identified, of whom 922 consented and were enrolled. Eligibility criteria included being HIV-infected, uncircumcised, aged 15 to 49 years, having no medical indications or contraindications for circumcision and, because the safety of MC in HIV-infected men was unknown, no evidence of immunosuppression (WHO clinical stages III or IV, or a CD4 count below 350 cells/ml3). Men with genital infections or a hemoglobin ≤ 8 gm/dL were treated and rescreened prior to enrollment.

Participants were randomly assigned to be circumcised within approximately two weeks (intervention arm) or after 24 months (control arm). Random assignment was in blocks of 20, with replacement.(3) Prior to circumcision men were provided with detailed instructions on postoperative wound care, hygiene, abstention from intercourse until complete wound healing had been certified and safe sexual practices thereafter. They were given an information sheet with these instructions to share with their sexual partners. Circumcisions were performed using the “sleeve” procedure.(3,5) Postoperative follow up visits were scheduled at 24–48 hours, 5–9 days and 4–6 weeks, and predefined adverse events (AEs) were recorded.(3,5) Men whose wound was not fully healed at the 4–6 week visit were followed weekly until healing was certified.

At each postoperative follow up, participants were interviewed and the wound was inspected. Participants were asked about resumption of sexual intercourse; those who resumed sex were asked when intercourse first occurred following surgery and whether condoms were used. The sexual risk reduction information, including post-surgical sexual abstinence until completed wound healing, was reiterated at each postoperative visit. Male participants in both arms were then followed at 6, 12 and 24 months post-enrollment; interviewed regarding sexual behaviors, health and related issues; and examined. Venous blood samples and penile swabs were collected.

Female partner participation

Male participants in the trials of MC in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected men were asked to invite their wives or permanent consensual partners (subsequently referred to as female partners) to enroll in a study to assess the efficacy of MC for prevention of male-to-female HIV and STI transmission. Enrolment and follow up procedures were the same for female partners regardless of the male’s HIV status. Results reported in this paper are for the partners of HIV-positive men.

Female partners were informed of study goals and procedures, were told that the effects of MC on transmission of HIV or STIs were unknown, and were counseled on HIV and STI prevention (including consistent condom use) and on the need to refrain from sexual intercourse following MC until completed wound healing was certified. All women participants provided written informed consent for enrolment and follow up.

Female partners were followed at 6, 12 and 24 months post-enrolment. At baseline and each follow up visit, women were administered a detailed sociodemographic, behavioral, and health interview and provided venous blood samples and self-collected vaginal swabs. Interviews were conducted in private, by trained same-sex interviewers fluent in Luganda.

At each study visit, participating men and their female partners were provided with intensive HIV/STI prevention education including abstinence, faithfulness and consistent condom use; were offered free condoms, and voluntary HIV counseling and testing (VCT) and couples counseling and testing (cVCT). Participants could enroll even if they declined to receive their HIV results or accept cVCT. Intensive efforts were made throughout the trial to facilitate individual and couples counseling and disclosure of HIV results, including the creation of couples’ support clubs. Participants were informed of the advantages of receiving HIV results including, as of 2004, access to free antiretroviral therapy offered by the RHSP through the President’s Emergency Program for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR).

In addition to the information provided to all participants, community meetings were conducted to inform the population of the trial and of the need for safe sexual practices regardless of the male partner’s circumcision status.

The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology, and by three Institutional Review Boards (IRBs): the Science and Ethics Committee of the Uganda Virus Research Institute; the Committee for Human Research at Johns Hopkins University, Bloomberg School of Public Health; and the Western Institutional Review Board, Olympia, Washington. Trial oversight was provided by an independent Data Safety and Monitoring Board (DSMB). A Community Advisory Board (CAB) provided guidance on study design, conduct and the dissemination of results to the community. The trial was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practices and International Clinical Harmonization (GCP-ICH). Women were compensated for their time and travel costs, equivalent to $3.00 per visit, for a total of $12.00 for completion of all study visits. The CAB, DSMB and IRBs approved this compensation as appropriate.

The parallel MC trial in HIV-negative men was closed on December 12, 2006, following an interim analysis which demonstrated the efficacy of MC for HIV prevention in men.(3) Participants in both trials, as well as Rakai communities, were informed of this finding. Because continuation of the trial in HIV-infected men could result in stigmatization of participants, enrolment of HIV-positive men was paused and the investigators requested an unscheduled interim review and guidance from the DSMB. The DSMB determined that the conditional power to detect 60% efficacy, as specified in the study protocol, was only 4.9% and recommended that enrollment be closed. The investigators were unblinded, and study participants (men and women) were informed of the finding. However, the DSMB recommended continued follow up of enrolled participants. The DSMB reviewed the follow up data on Dec 17, 2007 and recommended that follow up of HIV-positive men and their partners be closed. The current analysis is based on results to that date.

Laboratory methods

HIV status was assessed by two enzyme immunoassays (EIAs): Vironostika HIV-1 (Organon Teknika, Charlotte, North Carolina, USA] and Murex Biotech [Central Road Temple Hill, Darford, UK). Discordant EIA results and seroconversions were confirmed by Western blot (Calypte Biomedical Corporation, Rockville, MD, USA). Male HIV viral load was measured by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT_PCR) assay (AMPLICOR HIV-1 MONITOR version 1.5, Roche Molecular Systems, Branchburg, N.J.). Women’s self-collected vaginal swabs were assessed for Trichomonas vaginalis by InPouch TV culture (BioMed Diagnostics, San Jose CA). Vaginal flora was quantified by the Nugent method;(10) a score of 7–10 was classified as BV.

To ascertain whether females had acquired HIV from their linked partner, viral sequence data were generated from both individuals for portions of the gag and gp41 fragments(11). The genetic distance of the viral sequences between the two partners was compared to the variation between epidemiologically unrelated individuals in the Rakai population.(12, 13).

Statistical analyses

The primary endpoint was male-to-female HIV transmission. Based on our prior observational data,(7) the study was powered to detect an incidence rate ratio of 0. 41 for HIV transmission from intervention compared to control arm HIV-positive men. We estimated that 220 couples would provide 80% power to detect this reduction over two years, adjusting for losses to follow up and crossovers. We also hypothesized reduced transmission in couples in which the circumcised HIV-infected man had a viral load <50,000 cps/mL and estimated that the study had >90% power to detect >95% efficacy in this subgroup. No interim analyses were planned.

Enrolment characteristics of males and females in concurrently enrolled couples were assessed using Chi-square tests for differences in distributions between study arms. The effect of MC on male-to-female HIV transmission was assessed in an intention-to-treat analysis using Kaplan-Meier estimation, based on the time to the follow up visit at which the female partner was first HIV-positive. An overall risk difference and risk ratios were calculated at the end of follow-up, with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) based on Greenwood variance estimates. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the adjusted hazards ratio (adj HR) of HIV detection in female partners, after adjustment for covariates which differed between study arms at enrollment at p < 0.15. We evaluated male-to-female HIV transmission by female reported characteristics and behaviors at enrollment and follow up. Female risk behaviors were also compared between arms at each follow up visit. We determined the prevalence of vaginal infections and symptoms during follow up, and estimated the prevalence risk ratios using modified Poisson regression with robust variance estimation to account for repeat observations.

After unblinding the study, the DSMB requested further analyses, including male-to-female HIV transmission in intervention arm couples by timing of resumption of intercourse relative to certification of wound healing. Given the schedule of postoperative visits, timing of healing could not be precisely determined, since healing preceded certification (i.e., there was an unknown interval between actual and observed healing). We assumed that men who resumed sex within the 5 days prior to or after certified healing had initiated intercourse when the surgical wound was likely to be intact; and were classified as “delayed resumption of sex.” Couples who resumed sex more than 5 days prior to observed healing, when scar formation were less likely to have been complete, were classified as having “early resumption of sex”. We then assessed male-to-female HIV transmission in intervention arm couples reporting early and delayed resumption of sex.

After the study was unblinded, we examined HIV viral load (VL) prior to and after MC among consenting control arm men who received circumcision as a service, in order to assess whether the stress of surgery might upregulate HIV VL. Eighty nine men not on ART and 25 men on ART provided blood immediately prior to surgery and at the one month post surgical visit. (During the trial, bloods were not collected between the time of surgery and the 6 month follow up visit.) We estimated within-individual change in log10 HIV VL copies/mL after MC, relative to the preoperative levels, using a paired t test.

Trial registration, funding, role of the funding source and study collaborators

The trial was registered in the Clinical Trials.gov Protocol Registration System (NCT00124878) and was funded by The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation as an investigator-initiated grant (Grant # 22006). Additional support for laboratory analyses and training were provided, respectively, by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health and the Fogarty International Center (grants 5D43TW001508 and D43TW00015) The study was conducted by the Rakai Health Sciences Program, a research collaboration between the Uganda Virus Research Institute, and researchers at Makerere and Johns Hopkins Universities. FM and LHM had full access to all data until trial closure. All other investigators were blinded until trial closure and had access to data thereafter. RR from the Gates Foundation maintained oversight of progress, participated in open DSMB sessions and in the interpretation of data. The research team conducted data analyses at Johns Hopkins University and at the Rakai Health Sciences Center. The corresponding author had final responsibility for preparing results for publication.

Findings

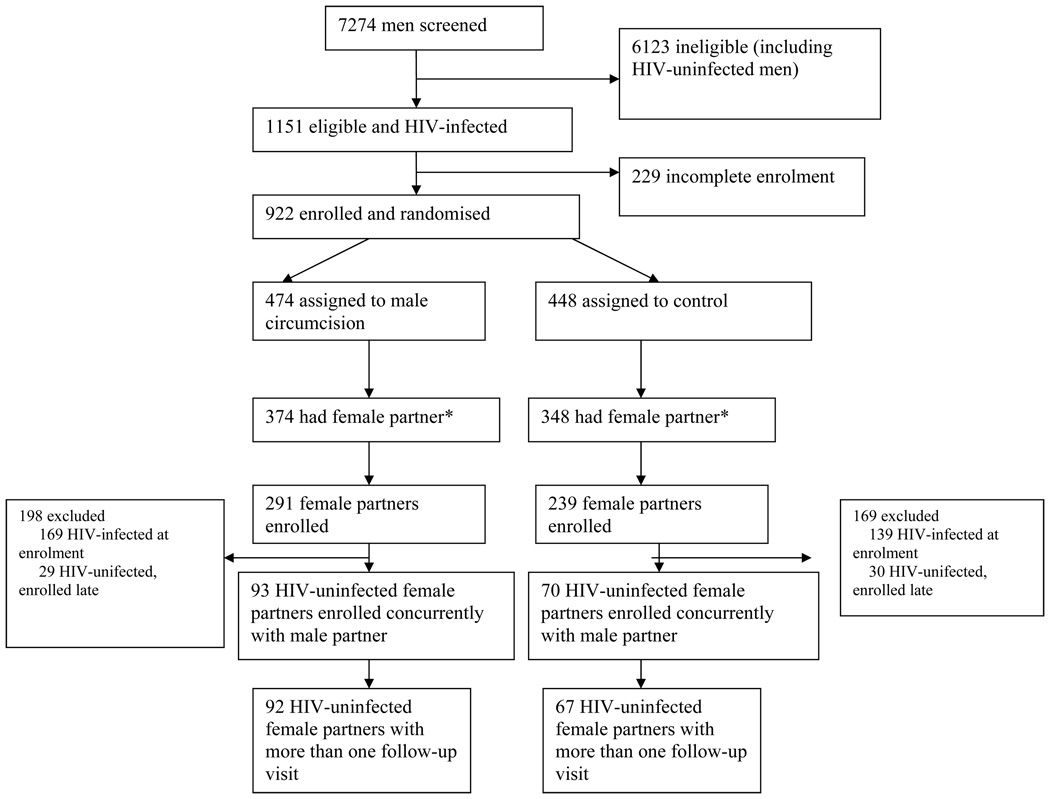

The trial profile is shown in figure 1. A total of 7,274 men were screened of whom 1,151 (15.8%) were HIV-infected and eligible; of these, 922 (80.1%) consented and enrolled. Among 474 HIV-infected men randomized to the intervention arm, 374 (78.9%) were currently married or in a consensual union: 291 (77.8%) of their female partners consented and enrolled, of whom 122 (42.0%) were HIV-negative at the time of enrolment. Of these HIV-negative women, 93 (32.0%) enrolled concurrently with their husbands and 92 had at least one follow up visit over 24 months. Among 448 HIV-positive men randomized to the control arm, 348 (77.6%) were in a current marriage/consensual union; 239 (68.7%) of these female partners consented and enrolled, of whom 100 (42.0%) were HIV-negative at the time of enrolment. Of these women, 70 (29.3%) enrolled concurrently with their husband and 67 had at least one follow up visit over 24 months. The 92 intervention arm couples and 67 control arm couples with concurrent female and male enrolment and at least one female follow up visit constitute the primary population for determining male-to-female HIV transmission.

Figure 1.

Trial Profile.

An additional 29 HIV-negative female partners of intervention arm men and 30 HIV-negative partners of control arm men entered the study six or more months after their husband's enrollment. These women were excluded from the primary male-to-female HIV transmission analysis since, unless women enrolled at the same time as their partner, we did not know their HIV status at the time of their husband’s enrolment. Thus, we could not determine which HIV-infected late-enrolling women had seroconverted since their husband’s enrolment, and this could thus result in bias if HIV transmission in the first six months differed by study arm. The couples with delayed female enrollment were assessed in secondary analyses.

Table 1 shows the enrollment characteristics of HIV infected men and concurrently enrolled HIV-uninfected partners. There were no significant differences between arms in male characteristics or behaviors at enrollment. Female partners of men in both arms were comparable with respect to numbers of sexual partners in the past year, alcohol use and STI symptoms. However, intervention arm female partners were somewhat younger (p = 0.067) and less likely to report condom use in the past year (p = 0.017). At enrollment, 97.7% of intervention arm and 94.1% of control arm men had received their HIV results and post-test counseling. Among female partners, 68.8% in the intervention arm and 74.3% in the control arm accepted HIV results and post-test counseling at time of enrolment, and an additional 16.4% of intervention arm and 16.2% of control arm women reported they had previously received their results (i.e., 85.2% intervention and 90.5% control females had received HIV results). All participants received intensive HIV prevention education. Female retention rates were comparable in both arms at the 6, 12 and 24 month follow up visits. (Table 2)

Table 1.

Enrollment characteristics of HIV-infected men and HIV-negative women in couples enrolled concurrently.

| Males | Female Partners | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | Exact P-value |

Intervention | Control | Exact P- value |

|||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

|

Total Enrolment age |

87 | 100 | 68 | 100.0 | 93* | 100.0 | 70* | 100.0 | ||

| 15–19 | 4 | 4.3 | 3 | 4.3 | ||||||

| 20–29 | 25 | 28.7 | 13 | 19.1 | 0.375 | 60 | 64.6 | 31 | 44.3 | 0.067 |

| 30–49 | 62 | 71.3 | 55 | 80.9 | 29 | 31.2 | 36 | 51.4 | ||

| Education | ||||||||||

| None | 1 | 1.1 | 4 | 5.9 | 13 | 14.0 | 11 | 15.7 | ||

| Primary | 69 | 79.3 | 50 | 73.5 | 0.174 | 74 | 79.6 | 55 | 78.6 | 0.955 |

| Secondary or higher | 17 | 19.5 | 14 | 20.6 | 6 | 6.6 | 4 | 5.7 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Never married | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.4 | ||||||

| Monogamous | 74 | 85.1 | 54 | 79.4 | 76 | 81.7 | 57 | 81.4 | ||

| Polygamous | 13 | 14.9 | 14 | 20.6 | 0.398 | 17 | 18.3 | 12 | 17.1 | 1.000 |

| Sex partners past year | ||||||||||

| None | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 2.9 | ||||||

| One | 35 | 40.2 | 26 | 38.2 | 82 | 88.2 | 63 | 90.0 | ||

| Two | 35 | 40.2 | 32 | 47.1 | 0.605 | 9 | 9.7 | 4 | 5.7 | 0.340 |

| Three or more | 17 | 19.5 | 10 | 14.7 | 2 | 2.2 | 1 | 1.4 | ||

| Condom use past year | ||||||||||

| None | 47 | 54.0 | 27 | 39.7 | 73 | 78.5 | 44 | 62.9 | ||

| Inconsistent | 36 | 41.4 | 35 | 51.5 | 0.163 | 19 | 20.4 | 22 | 31.4 | 0.017 |

| Consistent | 4 | 4.6 | 6 | 8.8 | 1 | 1.1 | 4 | 5.7 | ||

|

Alcohol at time of sex, past year |

||||||||||

| Yes | 63 | 72.4 | 54 | 79.4 | 0.351 | 35 | 38.5 | 25 | 37.3 | 1.000 |

|

Accepted HIV results at time of enrollment STI symptom past yr |

85 | 97.7 | 64 | 94.1 | 0.405 | 64 | 68.8% | 52 | 74.3% | 0.488 |

| GUD | 23 | 26.4 | 13 | 19.1 | 0.340 | 15 | 16.1 | 14 | 20.0 | 0.541 |

| Discharge/dysuria | 18 | 20.7 | 10 | 14.7 | 0.403 | 47 | 50.5 | 35 | 50.0 | 1.000 |

| STI symptom, current | ||||||||||

| GUD | 3 | 3.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.256 | 2 | 2.2 | 1 | 1.4 | 1.000 |

| Discharge/dysuria | 5 | 5.8 | 3 | 4.4 | 1.000 | 19 | 20.5 | 15 | 21.4 | 1.000 |

| Syphilis serology | ||||||||||

| RPR/TPPA neg | 74 | 91.4 | 58 | 87.9 | 77 | 89.5 | 58 | 85.3 | ||

| RPR+/TPPA neg | 4 | 4.9 | 1 | 1.5 | 5 | 5.8 | 4 | 5.9 | 0.612 | |

| RPR+/TPPA+ | 3 | 3.7 | 7 | 10.6 | 0.150 | 4 | 4.7 | 6 | 8.8 | |

|

Male partner HIV viral load |

||||||||||

| BD, <400 | 18 | 20.7 | 6 | 8.8 | ||||||

| <50,000 cps/ML | 47 | 54.0 | 42 | 58.8 | 0.109 | |||||

| ≥ 50,000 cps/mL | 22 | 25.3 | 22 | 32.4 | ||||||

The number of males is less than the number of females enrolled because 5 men in the intervention arm and 2 in the control arm were polygamous and both their co-wives were enrolled. In the analyses, correlation was accounted for by robust variance estimates.

Table 2.

Female Partner Retention Rates

| Intervention | Control | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number followed/Eligible |

Percent retention |

Number followed/Eligible |

Percent retention |

|

| 0–6 months | 88/93 | 94.6 | 63/70 | 90.0 |

| 6–12 months | 88/93 | 94.6 | 65/70 | 92.9 |

| 12–24 months | 50/61* | 82.0 | 36/42* | 85.7 |

The population at risk in the second year was diminished by losses to follow up in the first year, and by women whose follow up was truncated before completion of 24 months follow up due to early trial closure.

Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier cumulative probabilities of female HIV acquisition in couples with concurrent male and female enrolment. Over the 24 month follow up, the cumulative probability of female HIV acquisition was 21.7% (95%CI 12.7–33.4%) in the intervention arm and 13.4% (95%CI 6.7–25.8%) in the control arm (unadjusted HR=1.58, 95%CI: 0.68–3.66, p=0.287). After adjustment for differences in enrollment characteristics by Cox proportional hazards regression, the adjusted HR was 1.49, 95% CI 0.62–3.57, p = 0.368). When female partners who enrolled six months or more after their husband are included, the cumulative probability of infection was 17.4% in the intervention arm and 15.8% in the control arm (HR = 1.22, 95%CI 0.59–2.54, p = 0.65). There were no male crossovers among couples in the primary analysis. There were three crossovers among men whose female partner had delayed enrolment, but none of these crossover men transmitted to their partners.

Figure 2.

Cumulative probability of Female HIV acquisition.

In a subanalysis (not specified in the protocol), we assessed whether HIV transmission in intervention arm couples was associated with the timing of resumption of intercourse relative to wound healing (Table 3). HIV acquisition, observed at six months, occurred in 27.8% (5/18) of women in intervention arm couples who resumed sex early, compared to 9.5% (6/63) of women in couples with delayed resumption of sex (RR = 2.92, 95%CI 1.01–8.46, p = 0.06). The proportion of women acquiring HIV by 6 months in intervention arm couples who delayed sex (9.5%) was comparable to the proportion of newly HIV-infected control arm women ( 7.9%[(5/63]; p = 1.0). However, the rate of female HIV acquisition at 6 months in intervention arm couples with early post-surgical resumption of sex (27.8%) was significantly higher than in control arm women (RR = 3.50. 1.14–10.76, p = 0.038).

Table 3.

Proportions of women with observed HIV acquisition at the 6 month follow-up visit in the control arm, and in the intervention arm by timing of resumption of intercourse in relation to post surgical wound healing.

| Resumption of sex relative to wound healing |

N= women seen at 6 months* |

Female HIV incident cases at 6 month follow up |

Percent HIV acquisition (95% CI) |

Rate ratio of female incident HIV in intervention arm couples with early and delayed resumption of sex after MC, compared to control arm couples (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention arm early resumption of sex: Sex resumed 5 or more days before male partner’s wound was certified as completely healed. |

18 | 5 | 27.8 (7.10 – 57.55) |

3.50 (1.14–10.76) p = 0.038 |

| Intervention arm delayed resumption of sex: Sex resumed within 5 days or after male partner’s wound was certified as completely healed. |

63 | 6** | 9.5 (3.26 – 15.74) |

1.20 (0.39–3.73) p = 1.00 |

| Control arm | 63 | 5 | 7.9 (1.26– 14.61) |

1.0 |

The denominators includes women seen at 6 months for whom data was available on their husband’s timing of intercourse relative to wound healing. The total number of intervention arm women with information on resumption of sex relative to their husband’s wound healing (81), is less than the 88 women seen at 6 months (Table 2), because information on sexual resumption was collected from the male spouse . Men’s follow up at 6 months was 89.0%

One female participant missed the 6 months visit, was found to be HIV infected at 12 months and her husband reported delayed resumption of intercourse after surgery. It was conservatively assumed that this female infectionoccurred during the 0–6 month interval. If this infection had occurred between 6 and 12 months, the percent HIV acquisition at the 6 month follow up visit among women with delayed sexual resumption would be 7.9, rate ratio of early versus late sexual resumption = 3.44 (1.12–10.59), exact p = 0.04.

There were no significant differences in HIV transmission between study arms by enrollment covariates, nor by female-reported sexual risk behaviors during follow up (data not shown). Among women whose partner’s enrollment viral load was <50,000 cps/mL, the cumulative probability of HIV acquisition was 15.7% (11/70) in the intervention arm and 10.6% (5/47) in the control arm (HR = 1.48, 95%CI 0.55–3.98, p = 0.43). Among couples with a male enrollment viral load > 50,000 cps/mL, female cumulative HIV acquisition was 27.3% (6/22) in the intervention arm and 15.0% (3/20) in the control arm (HR = 1.82, 95%CI 0.52–6.32, p = 0.34)

There were no statistically significant differences in female-reported number of sexual partners, condom use, or use of alcohol with sex during follow up (Table 4). In the intervention arm, 75.3% (70/93) of HIV-infected men disclosed their serostatus to their female partner; and in the control arm, 77.1% (54/70) of men disclosed their serostatus (p = 0.38).

Table 4.

Women’s sexual behaviors during follow up, by study arm

| Intervention | Control | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number/Visits | % | Number/Visits | % | ||

| 6 months visit | |||||

| Number of sexual partners | N = 88 | N = 63 | 0.89 | ||

| None | 2 | 2.3 | 2 | 3.2 | |

| One | 83 | 94.3 | 58 | 92.1 | |

| Two or more | 3 | 3.4 | 3 | 4.8 | |

| Condom use among sexually active | N = 86 | N = 61 | |||

| None | 55 | 62.5 | 37 | 58.7 | 0.16 |

| Inconsistent | 8 | 9.1 | 12 | 19.0 | |

| Consistent | 23 | 26.1 | 12 | 19.0 | |

| Alcohol use with sex among sexually active | 32 | 37.2 | 24 | 39.3 | 0.86 |

| 12 month visit | |||||

| Number of sexual partners | N = 88 | N = 65 | |||

| None | 3 | 3.4 | 3 | 4.6 | 0.87 |

| One | 76 | 86.4 | 57 | 87.7 | |

| Two or more | 9 | 10.2 | 5 | 7.7 | |

| Condom use among sexually active | N = 85 | N = 62 | |||

| None | 47 | 55.3 | 32 | 51.6 | 0.36 |

| Inconsistent | 8 | 9.4 | 11 | 17.7 | |

| Consistent | 30 | 35.3 | 19 | 30.6 | |

| Alcohol use with sex among sexually active | 38 | 44.7 | 27 | 43.5 | 1.00 |

| 24 month visit | |||||

| Number of sexual partners | N = 49 | N = 33 | |||

| None | 3 | 6.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.480 |

| One | 42 | 86.0 | 31 | 93.9 | |

| Two or more | 4 | 8.0 | 2 | 6.1 | |

| Condom use among sexually active | N = 46 | N = 33 | |||

| None | 21 | 45.7 | 17 | 51.5 | 0.28 |

| Inconsistent | 2 | 4.4 | 4 | 12.1 | |

| Consistent | 23 | 50.0 | 12 | 36.4 | |

| Alcohol use with sex among sexually active | 15 | 32.6 | 12 | 36.4 | 0.81 |

The proportions of follow up visits at which female partners reported STI symptoms or had laboratory diagnosed BV in the intervention and control arms, respectively, were: GUD, 16.4% (37/225) versus 16.1% (26/161), p=0.95; vaginal discharge, 36.4% (82/225) versus 32.3% (52/161), p=0.50; dysuria, 15.5% (35/225) versus 14.9% (24/161), p=0.89; and BV, 55.8% (121/217) versus 51.9% (83/160), p=0.54. Trichomonas was detected in 6.5% (9/138) of follow up visits in intervention arm women and 15.2% (17/112) of visits in control arm women (PRR = 0.43, 95%CI 0.18–1.02), which was of borderline statistical significance (p = 0.056).

Among 25 couples in which the female partner seroconverted during the trial, sequence data for both partners were available for 13 pairs. In all 13 couples, the genetic distance of the viral sequences between partners was < 0.5% , which was less than two standard deviations below the median distance of sequences between unrelated individuals in Rakai, indicating probable HIV acquisition within the partnership.(13)

We assessed pre- and postoperative HIV VL in 89 ART naïve control arm participants receiving MC as a service. Among 80 men with detectable VL prior to surgery, the mean VL log10 cps/mL was 4.30 (SD 0.83) preoperatively, and 4.50 (SD 0.74) at the fourth postoperative week, a mean increase in intra-individual VL of 0.20 log10 cps/mL (p = 0.002). All 9 men with undetectable VL load prior to surgery remained undetectable at week four. In 25 control arm men who had initiated ART prior to circumcision, we observed no increase in VL in the 21 (84.0%) who had an undetectable VL prior to surgery, nor in the 4 men who had detectable preoperative VL.

Discussion and interpretation

Circumcision of HIV-infected men did not reduce HIV transmission to their uninfected female partners (Figure 2), and we cannot exclude the possibility of higher transmission in couples who resumed intercourse before complete healing of the surgical wound (Table 3). Since study duration was limited and not all women completed 24 months of follow, we could not assess long term benefits or risks to women. The findings indicate that strict adherence to sexual abstinence during wound healing and consistent condom use thereafter must be strongly promoted when HIV-infected men receive MC. .

These findings have important implications for MC programs. The WHO and UNAIDS recommend that HIV-positive men who request MC be provided with the service unless there are medical contraindications.(4) Despite the lack of MC efficacy for HIV prevention in women, we agree with these recommendations for the following reasons. If programs excluded HIV-infected men it could result in stigmatization, and it is likely that HIV-positive men would seek surgery from potentially unsafe sources to mask their serostatus. Conversely, circumcised HIV-negative men could use their MC status to negotiate unsafe sex. Additionally, circumcision reduces genital ulcer disease(6) and human papillomavirus infection in HIV-infected men, (pc RG) which constitute direct health benefits.

Our finding that resumption of intercourse prior to complete healing may increase the risk of HIV transmission to women makes it imperative that circumcised men and their female partners be clearly instructed to abstain from intercourse until wound is healed. We previously reported that wound healing was complete in 73.0% of HIV-positive men at 4 weeks and 92.7% at 6 weeks after MC(5) Thus, it would be prudent to recommend abstinence for a minimum of six weeks following surgery and to reexamine men to assess healing prior to advising that sexual intercourse may resume. It should be noted that the possible short-term increase in transmission to partners of circumcised HIV-positive men if sex is resumed early is unlikely to have a substantial effect on the HIV epidemic: the exposure period of possible increased risk is short and the number of HIV-positive men with uninfected female partners who resume sex early will generally represent a small proportion of MC program clients. Nonetheless, comprehensive MC programs should, wherever feasible, promote and offer condoms, VCT and cVCT, and MC-related health messages for women. Offering MC to infants and to boys prior to sexual debut would mitigate the challenges of MC in HIV-infected men, but would require careful attention to consent and assent by parents and minors.

We observed an increase in HIV viral load among ART naïve men following surgery, which could result in higher infectivity.(14 ), Our post-surgical assessment was conducted at 4 weeks, and additional research is needed to determine whether MC affects VL beyond this period.

We were disappointed that the trial did not show protection from HIV infection in women, as was expected from observational studies.(7–9). One possible explanation is that most men in the observational studies had been circumcised in childhood and did not initiate intercourse until long after completed wound healing. However, it should be noted that this trial did not show any trend towards protection at 12 and 24 months after surgery.

We previously reported that female partners of HIV-negative men randomized to MC had lower rates of GUD, trichomonas and BV.(15) In partners of HIV-positive men, MC was associated with lower rates of trichomonas (PRR = 0.42, 95% CI 0.18–1.02, p = 0.056),similar to the PRR in partners of HIV-negative men.(15) However, MC in HIV-positive men was not associated with lower rates of female partners’ STI symptoms or BV.

There are limitations to this study. The trial was underpowered, in part because the number of enrolled male HIV-positive/female HIV-negative discordant couples were lower than anticipated from prior Rakai cohort studies. Although the proportions of married men were comparable in both study arms (Figure 1), a higher proportion of intervention arm female partners enrolled (77.8%) compared to control arm partners (68.7%, p = 0.007). This suggests differential motivation to participate between arms, which may have introduced bias. However, with the exception of somewhat lower condom use reported by intervention arm women, there were no statistically significant differences in female baseline characteristics (Table 1) and adjustment did not materially affect the estimates of efficacy. The study was closed early and this limited our ability to assess longer-term effects. In addition, 29 wives in the intervention arm and 30 in the control arm were enrolled six or more months after their husbands, and were excluded from the primary analysis, however, inclusion of these late enrollees did not alter the results. Finally, for reasons of safety, we excluded HIV-positive men with CD4 cell counts less than 350 or WHO Stage III or IV disease. Thus, we cannot determine possible effects on female partners of MC in men with more advanced HIV infection.

It is important to note that this was not a classical discordant couples trial, in which participants enroll as a couple. HIV-positive males enrolled and were randomized as individuals, and were asked to invite their partners, who also enrolled as individuals. Participants were strongly encouraged to accept couples VCT at enrollment and throughout the trial, but about a quarter in each arm did not disclose their serostatus. In our prior experience, acceptance of cVCT is relatively low in this rural population and is more frequent in persons who know they are HIV-uninfected. HIV transmission rates in this study, particularly in the first six months, were high compared to studies of HIV-discordant couples enrolled after receiving cVCT. Such couples may represent a self-selected and motivated subpopulation and may be more likely to adopt preventive behaviors(16) than the individuals in this trial. For example, consistent condom use was uncommon at enrollment (Table 1), increased over time, but was still relatively low at 24 months (50.0% in the intervention arm and 36.4% in the control arm), despite repeated health education and the provision of free supplies.

It would be difficult to conduct another trial of MC effects on male-to-female HIV transmission. Given our results, such a trial would have to be powered to detect a low efficacy, requiring a very large population of male-infected HIV-discordant couples and protracted follow up. Given the potentially higher transmission rates in the post-surgical period, additional follow up visits and interim safety analyses would be needed. Thus costs, logistics and limited expectation of efficacy probably render such a trial unfeasible.

In conclusion, circumcision of HIV-infected men did not reduce HIV transmission to female partners, and the possibility of higher risk of transmission in couples who resumed intercourse before completed wound healing cannot be excluded. Wherever possible, MC should be offered in conjunction with HIV counseling services, condoms, and HIV prevention education for men and women, to optimize the health and safety of MC patients and their partners. However, the efficacy of MC for prevention of HIV in uninfected men is clear,(1–3) and reductions in male HIV acquisition attributable to circumcision are likely to reduce women’s exposure to HIV-infected men.(17,18) MC programs are thus likely to confer an overall benefit to women.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Data and Safety Monitoring Board, as well as the institutional review boards that provided oversight (the Science and Ethics Committee of the Uganda Virus Research Institute; and the Western Institutional Review Board). We are also grateful for the advice provided by the Rakai Community Advisory Board. We wish to thank Dr. Edward Mbidde, Director, Uganda Virus Research Institute for his support. Finally, we wish to express our gratitude to the study participants whose commitment and cooperation made the study possible.

Funding: The trial was funded by The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (Grant 22006). Additional support for laboratory analyses and training were provided, respectively, by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health and the Fogarty International Center (grants 5D43TW001508 and D43TW00015)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Clinical Trials.gov Protocol Registration System NCT00124878

Contributors: All authors took part in the preparation of the paper and approved the final version.

Conflict of Interest Statement: We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Auvert B, Taljaard D, Lagarde E, Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Sitta M, Puren A. Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: The ANRS 1265 trial. Plos Medicine. 2005;2(11):1112–1122. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB, Agot K, Maclean I, Krieger JN, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369(9562):643–656. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, Makumbi F, Watya S, Nalugoda F, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2007;369(9562):657–666. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO/UNAIDS. New Data on Male Circumcision and HIV Prevention: Policy and Programme Implications. 2007 Ref Type: Report.

- 5.Kigozi G, Gray RH, Wawer MJ, Serwadda D, Makumbi F, Watya S, et al. The safety of adult male circumcision in HIV-infected and uninfected men in Rakai, Uganda. PLoS.Med. 2008;5(6):e116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wawer MJ, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, Makumbi F, Nalugoda F, Watya S. Trial of male circumcision in HIV+ men and in women partners; 15th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2008. Feb, p. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray RH, Kiwanuka N, Quinn TC, Sewankambo NK, Serwadda D, Mangen FW, et al. Male circumcision and HIV acquisition and transmission: cohort studies in Rakai, Uganda. Rakai Project Team. AIDS. 2000;14(15):2371–2381. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200010200-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kapiga SH, Lyamuya EF, Lwihula GK, Hunter DJ. The incidence of HIV infection among women using family planning methods in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. AIDS. 1998;12(1):75–84. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199801000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunter DJ, Maggwa BN, Mati JK, Tukei PM, Mbugua S. Sexual behavior, sexually transmitted diseases, male circumcision and risk of HIV infection among women in Nairobi, Kenya. AIDS. 1994;8(1):93–99. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199401000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of gram stain interpretation. J.Clin.Microbiol. 1991;29(2):297–301. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.2.297-301.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang C, Dash B, Hanna SL, Frances HS, Nziambi N, Colebunders RC, St Louis M, Quinn TC, Folks TM, Lal RB. Predominance of HIV type 1 subtype G among commercial sex workers from Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2001;17(4):361–365. doi: 10.1089/08892220150503726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trask SA, Derdeyn CA, Fideli U, Chen Y, Meleth S, Kasolo F, Musonda R, Hunter E, Gao F, Allen S, Hahn BH. Molecular epidemiology of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 transmission in a heterosexual cohort of discordant couples in Zambia. J. Virol. 2002;76:397–405. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.1.397-405.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wawer MJ, Gray RH, Serwadda D, Li X, Kiwanuka N, Kigozi G, Meehan MP, Wabwire-Mangen F, Kiddugavu M, Lutalo T, Nalugoda F, Sewankambo NK. HIV transmission per coital act by stage of index partner infection in discordant couples, Rakai Uganda. JID. 2005;191:1403–1409. doi: 10.1086/429411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quinn TC, Wawer MJ, Sewankambo N, Serwadda D, Meehan M, Li C. Rakai Project Study Team, RH Gray. HIV serum viral load, risk factors and HIV transmission in discordant couples, Rakai, Uganda. NEJM. 2000;342:921–929. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003303421303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, Makumbi F, Watya S, Moulton L, et al. The effects of male circumcision on female partners' genital tract symptoms and vaginal infections in a randomized trial in Rakai, Uganda. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;200:42e1–42e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.07.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lingappa JR, Kahle E, Mugo N. Characteristics of HIV-1 discordant couples enrolled in a trial of HSV-2 suppression to reduce HIV-1 transmission: the partners study. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hallett TB, Singh K, Smith JA, White AG, Abu-Raddad LJ, Garnett GP. Understanding the impact of male circumcision interventions on the spread of HIV in southern Africa. PLos ONE. 2008;3:e2212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White RG, Orroth KK, Freeman EE, Bakker R, Weiss HA, Kumaranayake LHJ, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in sub-Saharan Africa: who, what and when? AIDS. 2008;22(14):1841–1850. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830e0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]