Abstract

Objective

Dysfunction of the hippocampus has long been suspected to be a key component of the pathophysiology of major depressive disorder. Despite evidence of hippocampal structural abnormalities in depressed patients, abnormal hippocampal functioning has not been demonstrated. We aimed to link spatial navigation deficits previously documented in depressed patients to abnormal hippocampal functioning using a virtual reality navigation task.

Method

Whole-head magnetoencephalography (MEG) recordings were collected while participants – 19 patients diagnosed with major depressive disorder and 19 healthy controls, matched by gender and age – navigated a virtual Morris water maze to find a hidden platform, and a visible one as a control condition. Behavioral measures were taken to assess navigation performance. Theta oscillatory activity (4-8 Hz) was mapped across the brain on a voxel-wise basis using a spatial-filtering MEG source analysis technique.

Results

Depressed patients performed worse than controls in navigating to the hidden platform. Robust group differences in theta activity were observed in right medial temporal cortices during navigation, with patients exhibiting less engagement of the anterior hippocampus and parahippocampal cortices compared to controls. Left posterior hippocampal theta activity was positively correlated with individual performance within each group.

Conclusions

Consistent with previous findings, depressed patients showed impaired spatial navigation. Dysfunction of right anterior hippocampus and parahippocampal cortices may underlie this deficit and stem from structural abnormalities commonly found in depressed patients.

Introduction

A pivotal role for the hippocampus in the pathophysiology of major depressive disorder (MDD) is supported by abundant evidence (1, 2). Numerous studies, for instance, have reported hippocampal structural abnormalities in depressed patients; meta-analyses support the reliability of these observations (3, 4). Chronic stress and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis hyperactivity – commonly seen in depressed patients (5), and which cause hippocampal atrophy in animals and increased vulnerability of neurons to various insults such as glutamatergic excitotoxicity (6) – may cause these structural abnormalities. Given widespread projections of the hippocampus to prefrontal cortices, amygdala and striatum, hippocampal dysfunction might underlie the array of cognitive, affective and reward-related changes associated with major depressive disorder.

Abnormal hippocampal functioning in depressed patients has been inferred from structural abnormalities, resting-state metabolic abnormalities (7) and neuropsychological tests (8) but has yet to be demonstrated in a hippocampus-dependent task. Recently, Gould and coworkers (9), using a virtual reality paradigm, found both patients with major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder to be impaired at spatial navigation. These results are noteworthy in that functional imaging research with virtual environments has shown that spatial navigation activates hippocampal and parahippocampal regions in the healthy human brain (10). Invasive electrophysiological studies in epileptic patients have also established that neuronal populations in the hippocampus and neocortex show rhythmic electrical activity during virtual navigation (11, 12). Rhythmic activity of about 4-8 cycles/second (Hz) - referred to as theta - is prominent in the animal hippocampus during exploration and may directly modulate synaptic plasticity for spatial learning (13, 14). Functional or structural brain measurements were not taken by Gould et al. (9), however, and thus a direct link between hippocampus functioning and spatial deficits in depressed patients remains to be demonstrated.

We used a virtual reality analogue of the Morris water maze task to establish this link. The goal of this task, like the actual version administered to rodents that is sensitive to hippocampal dysfunction (15, 16), is to escape from a pool of water by reaching a hidden, submerged platform. The fixed location of the hidden platform can be learned by using distal cues on the surrounding walls to guide navigation from various starting positions. Performance on the virtual water maze task is sensitive to the structural integrity of the hippocampus (17), and hippocampal and parahippocampal regions are active in healthy individuals (18, 19). Neuromagnetic data were collected noninvasively with whole-head magnetoencephalography (MEG). Theta oscillatory activity was mapped across the brain using a source analysis technique called synthetic aperture magnetometry (20). In a previous study using the same task, healthy participants showed robust anterior hippocampal theta activity during navigation to the hidden platform relative to performing aimless movements in the virtual pool; posterior hippocampal theta responses were positively correlated with navigation performance (18). Based on these findings, we hypothesized that together with impaired navigation to the hidden platform, depressed patients would exhibit reduced anterior hippocampal and parahippocampal theta activity relative to healthy controls. We also hypothesized that posterior hippocampal theta would positively correlate with navigation performance at the individual level within each group.

Method

Participants

Depressed patients were recruited from inpatient and outpatient psychiatric units at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) as part of randomized clinical medication trials for unipolar depression. The patient group comprised 19 right-handed individuals with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder (Table 1), currently depressed without psychotic features; diagnosis was confirmed by a Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV Disorders–Patient Version (21). Patients with a DSM-IV(22) diagnosis of drug or alcohol dependence or abuse within the past three months, history of head injury, unstable medical illness or uncorrected hypo- or hyperthyroidism were excluded. All subjects had been free of psychotropic drugs for at least two weeks (five weeks for fluoxetine), and medically healthy as determined by medical history, physical and neurological exams and laboratory tests. Most patients had received lifetime trials of medications (89%), the most common being selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI, 79%), venlafaxine (42%), and duloxetine (37%) and bupropion (37%). During the current major depressive episode the most common trials were SSRIs (63%), duloxetine (26%) and bupropion (26%). No patient had received electro-convulsive therapy. The severity of their current depressive episodes was assessed using the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (23) Nine of the 19 patients had a comorbid anxiety disorder, none of which included posttraumatic stress disorder.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the samples

| Characteristic | Depressed Patients (N = 19) Mean ± SD | Healthy Controls (N = 19) Mean ± SD | Test of difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (Male : Female) | 12 : 7 | 11 : 8 | χ2 (1) = .11, p > .70 |

| Age (yr) | 41.8 ± 14 | 37.4 ± 10.5 | t (36) = 1.1, p > .28 |

| MADRS | 30.5 ± 7.0 | ||

| Duration of current episode (mo) | 81.7 ± 124.8 | ||

| Age of illness onset (yr) | 19.9 ± 10.3 | ||

| Lifetime duration of illness (yr) | 21.9 ± 13.0 | ||

| WAIS (Global IQ) | 117 ± 16 |

Note: MADRS = Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale; WAIS = Weschler Adult Intelligence Scale; mean Global IQ is calculated from 15 patients that completed the instrument.

Nineteen right-handed healthy controls were recruited from the local community (Table 1). Healthy controls underwent screening at the NIMH that included a medical history and physical exam performed by a physician, and a Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (24). Exclusion criteria included current medical illness and Axis-I DSM-IV psychiatric disorder, and first-degree relatives with a history of psychiatric disorders; family history was assessed per self-report during the interview with the clinician. No subject could be currently taking psychotropic medications per self-report. The study was approved by the Combined Neuroscience Institutional Review Board of the NIH. After complete description of the study to participants, written informed consent was obtained.

virtual Morris Water Maze

Participants completed 40 trials in which they moved with a fiber-optic joystick around a virtual pool using commercial software (NeuroInvestigations, Inc., Canada). Participants began each trial at the pool's edge in one of four locations (pseudo-randomly ordered). On half of the trials, participants were instructed to quickly navigate to a hidden platform in a fixed location (Hidden condition). If the hidden platform was not found within 20 s, it became visible and participants were instructed to navigate to it to finish the trial. This condition requires the use of distal cues on the surrounding walls to learn the fixed location of the hidden platform. On the other half of the trials, participants were instructed to navigate to a visible platform in a variable location (Visible condition). As the control condition, navigating to the visible platform does not require use of distal cues. The platform had a variable location across visible trials to limit spatial learning during this condition. Different pool environments were used for the two conditions with the only difference being the distal cues (e.g., door and shelves in one environment versus abstract patterns in the other); each virtual environment was assigned to contain the hidden or visible platform in equal proportions between groups. There were 2-s breaks between trials. The order of conditions was counterbalanced across participants.

Latency to reach the platform from first movement, latency to first movement, path length and heading error or angular deviation from a direct path to the platform were recorded for each hidden and visible platform trial. Heading error is a point estimate calculated when the path length exceeds one-fourth of the pool's diameter. Each of these measures was collapsed into five blocks of four trials. All participants received exposure to the task in a previous session before the MEG session to ensure ample practice. Platform locations were different between sessions.

Data Acquisition

Neuromagnetic data were recorded with a CTF-OMEGA 275-channel whole-head magnetometer (VSM MedTech, Canada) in a magnetically-shielded room (Vacuumschmelze, Germany) using synthetic third gradient balancing for active noise cancellation. Magnetic flux density was sampled at 1200 Hz with a bandwidth of 0-300 Hz. Electrical coils attached at three fiducial sites – nasion, right and left preauricular sites – were energized during each MEG recording to track head movements in real time and for offline registration to anatomical MRIs. Radiological markers (IZI Medical Products, MD) were attached to the same fiducial sites during the MRI scan. High-resolution T1-weighted anatomical MRIs were obtained in a separate session using a 1.5 or 3 Tesla whole-body scanner (GE Signa, WI).

Synthetic Aperture Magnetometry

Synthetic aperture magnetometry is a minimum-variance beamformer algorithm that uses the signal covariance from the sensor array for constructing optimum spatial filters at each location in the brain; an optimum spatial filter suppresses all source activity except for that which originates from the location of interest (25). Regional oscillatory changes estimated by this method are highly consistent with fMRI results (26), at cortical and subcortical loci (27), and in healthy individuals and depressed patients (28). Source imaging procedures were identical to those used by Cornwell et al. (18). Signal covariance was calculated between all sensors with data filtered between 4-8 Hz for 20 unaveraged 1-s epochs during navigation for each condition. Source space was sampled in 5-mm steps with current sources estimated at each location based on a multisphere model derived from the MRI of each participant. Dual-state images were calculated by dividing integrated power over 1-s windows during navigation by integrated power over 1-s pre-trial windows (pseudo-F ratios), yielding estimates of relative increases (or decreases) in theta activity during navigation in each condition. With a constant pre-trial window, relative theta power was estimated across 17 1-s windows during navigation with 75% overlap (0.00-1.00 s, 0.25-1.25, ..., 4.00-5.00), encompassing the first 5 s of each trial before the platform had been reached.

Using Analysis of Functional NeuroImages software (29), individual source image volumes for each condition and time window were manually warped to a Talairach brain template to allow for group analysis in a standardized source space and within-volume normalized using a z-score transformation. The latter procedure was performed to limit the influence of global power that may vary across participants, or systematically between groups, on local power estimates in a particular brain region.

Performance analyses

Navigation performance was assessed as follows: (1) latency to reach the platform from the first recorded movement, (2) path length to the platform and (3) heading error to the platform. Latency to first movement was also analyzed as a control measure. Gender and Age were added as nuisance factors in our analyses given evidence of their associations with spatial navigation performance (30, 31). We performed 2 × 2 × 2 × 5 mixed factorial ANCOVAs, with Age as a continuous covariate, Group and Gender as between-groups factors and Condition (Hidden vs. Visible platform) and Block (1 to 5) as repeated-measures variables. Significant interactions between Group and Condition were followed up with simple effect analyses for each Condition. For cases in which differences emerged between patients and controls, post hoc analyses were run to determine whether there was evidence of differences within the patient group between those with and those without co-morbid anxiety disorders. Two patients’ path length and heading error data were lost to computer malfunction.

Functional imaging analyses

Group SAM analyses of 4-8 Hz theta power consisted of 2 (Patients versus Controls) x 2 (Hidden versus Visible) mixed factorial ANOVAs. We confined our subsequent simple effect analyses to functional regions of interest showing significant 2-way interactions at a nominal p-value < .05. Within these regions, we compared theta activity between groups for the hidden condition and the visible condition using Student t tests and estimated false discovery rates (32). A single correction for multiple comparisons was performed that incorporated all voxels within these regions and all time windows, such that we kept the overall false discovery rate of the source imaging results below 5%. As with the behavioral data, post hoc analyses were run that compared depressed patients with and those without co-morbid anxiety disorders specifically within clusters in medial temporal cortices showing differential activation between groups.

We determined what regional activity correlated at the individual level with navigation performance on hidden trials. Spearman correlations were calculated at each voxel for each time window for each group separately. A nonparametric approach was deemed most appropriate given the small samples. We identified only those regions with at least two contiguous voxels showing negative correlations, commonly in both groups but irrespective of the time window, surviving a statistical threshold of p < .005. Given previous results in left posterior hippocampal and parahippocampal cortices(18), we considered negative correlations only insofar as they reflect higher regional theta activity being associated with better navigation performance (e.g., shorter mean latencies).

Results

Group differences in navigation performance

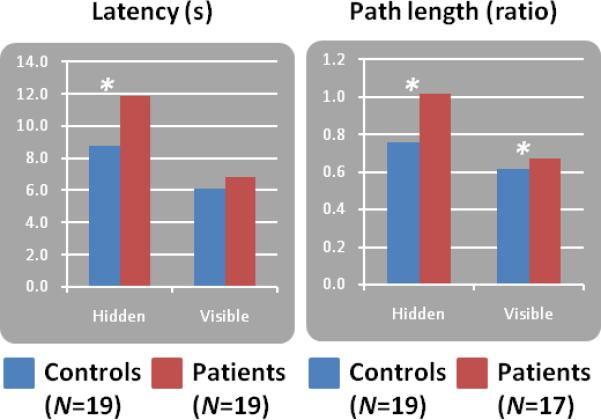

There were significant Group x Condition interactions on mean latency to reach the platform, F (1, 33) = 6.89, p < .05, and path length, F (1, 31) = 6.06, p < .05 (Figure 1), but not heading error, F < 1, nor latency to first movement, F < 1. For the hidden platform condition, patients were slower than controls to reach the platform, F (1, 33) = 10.77, p < .005, and they also took longer paths compared to controls, F (1, 31) = 13.28, p < .005. For the visible platform condition, there was no difference between patients and controls in mean latency, F (1, 33) = 2.26, p > .10, but patients did take longer paths to the platform compared to controls, F (1, 31) = 15.76, p < .001. For mean heading error, there was a significant Group difference, F (1, 31) = 8.86, p < .01, with patients performing worse than controls in both conditions. There was also a significant Group difference in latency to first movement, F (1, 33) = 4.70, p < .05, with patients initiating movements faster than controls in both conditions. Post hoc comparisons between patients with and without co-morbid anxiety disorders in the hidden platform condition revealed no differences in latency, F < 1, or path length, F (1, 12) = 3.31, p > .10. Regarding gender differences, men showed shorter path lengths and smaller heading errors than women, F (1, 31) = 16.52, p < .001 and F (1, 31) = 7.69, p < .01, respectively. There was a marginally significant difference between men and women in latency to reach the platform, F (1, 33) = 3.44, p < .10, but not latency to first movement, F < 1.

Figure 1.

Mean (unadjusted) spatial navigation performance in terms of latency and path length taken by Group and Condition (20 hidden platform trials versus 20 visible platform trials). *p < .005.

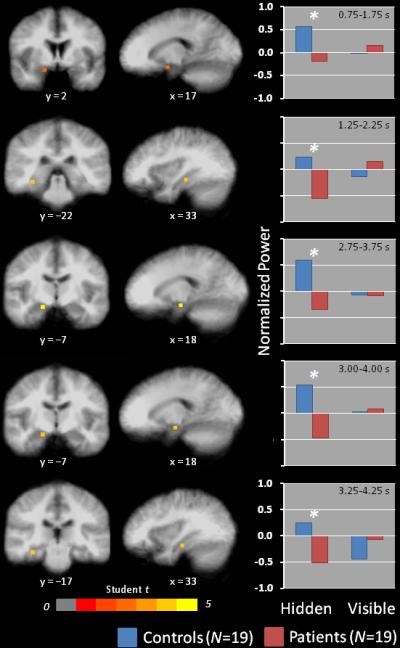

Group differences in navigation-related theta activity

Table 2 presents regions that showed significant group differences in theta activity for the hidden and visible platform conditions. Healthy controls exhibited greater theta activity than depressed patients in medial temporal cortices in five time windows during the hidden condition, all in the right anterior region (Figure 2). Peak activity differences varied between the hippocampus at 1.25-2.25 s and 3.25-4.25 s relative to trial onset, and anterior parahippocampal cortices at 0.75-1.75 s, 2.75-3.75 s, and 3.00-4.00 s. In all cases, group differences reflected a combination of greater theta activity in controls and lesser activity in patients relative to pretrial baseline activity. There were no instances in which patients exhibited greater theta activity than controls in medial temporal cortices during the hidden condition.

Table 2.

Regional theta activity showing significant group differences (Healthy controls minus Depressed patients) during navigation on hidden and visible platform trials

| Local maximum | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | BA | Time (s) | Side | Size | x | y | z | Student t |

| Hidden condition | ||||||||

| Anterior cingulate | 32 | 0.50-1.50 | L | 5 | –17 | +38 | +7 | +4.14 |

| 32 | 2.25-3.25 | L | 3 | –17 | +43 | –8 | +3.36 | |

| Cerebellum | – | 3.75-4.75 | L | 18 | –2 | –57 | –23 | –4.08 |

| Cingulate | 31 | 2.25-3.25 | L | 2 | –17 | –22 | +42 | +3.11 |

| 31 | 4.00-5.00 | L | 39 | –2 | –42 | +42 | +3.50 | |

| Hippocampus | – | 1.25-2.25 | R | 4 | +33 | –22 | –8 | +3.48 |

| – | 3.25-4.25 | R | 16 | +33 | –17 | –13 | +3.77 | |

| Inferior frontal | 47 | 1.00-2.00 | R | 5 | +43 | +28 | –18 | +3.05 |

| 46 | 1.75-2.75 | L | 2 | –42 | +43 | +7 | +2.91 | |

| 47 | 3.00-4.00 | L | 4 | –52 | +38 | –13 | +3.41 | |

| 45 | 3.25-4.25 | R | 15 | +53 | +33 | +2 | +4.67 | |

| 47 | 3.50-4.50 | R | 6 | +48 | +33 | –3 | +4.16 | |

| 47 | 3.75-4.75 | R | 2 | +48 | +28 | –3 | +2.61 | |

| 47 | 3.75-4.75 | L | 6 | –42 | +13 | –3 | –2.96 | |

| Inferior parietal | 40 | 3.25-4.25 | R | 2 | +63 | –22 | +22 | +2.73 |

| Lingual | 19 | 2.00-3.00 | R | 3 | +23 | –57 | –3 | –3.05 |

| Middle frontal | 46 | 0.50-1.50 | R | 14 | +38 | +43 | +7 | +3.65 |

| 9 | 1.50-2.50 | L | 2 | –42 | +33 | +32 | +2.52 | |

| 46 | 2.00-3.00 | R | 7 | +48 | +43 | +27 | +5.64 | |

| 10 | 2.50-3.50 | R | 7 | +33 | +63 | +2 | +4.68 | |

| 10/11 | 3.50-4.50 | L | 35 | –27 | +48 | –8 | +4.07 | |

| 10 | 3.75-4.75 | L | 5 | –32 | +53 | –3 | +3.94 | |

| 10 | 4.00-5.00 | L | 6 | –37 | +48 | +7 | +3.13 | |

| Middle occipital | 18 | 0.00-1.00 | R | 2 | +38 | -87 | +2 | –2.83 |

| Middle temporal | 21 | 0.00-1.00 | L | 2 | –67 | –32 | +2 | +3.14 |

| 21 | 2.00-3.00 | R | 5 | +53 | +8 | –33 | +3.92 | |

| 21 | 2.00-3.00 | R | 2 | +63 | +3 | –18 | +3.87 | |

| Parahippocampal | 34 | 0.75-1.75 | R | 4 | +17 | +2 | –13 | +2.79 |

| Parahippocampal | 28/34 | 2.75-3.75 | R | 3 | +18 | –7 | –13 | +4.17 |

| 28/34 | 3.00-4.00 | R | 3 | +18 | –7 | –13 | +3.97 | |

| Posterior cingulate | 31 | 0.50-1.50 | L | 3 | –7 | –62 | +17 | –3.42 |

| Precentral | 4 | 2.25-3.25 | L | 2 | –27 | –17 | +47 | +3.31 |

| Superior frontal | 10 | 1.75-2.75 | R | 11 | +3 | +68 | +22 | +5.24 |

| 11 | 1.75-2.75 | R | 7 | +13 | +48 | –13 | +3.56 | |

| 8 | 1.75-2.75 | R | 7 | +38 | +23 | +52 | +5.92 | |

| 11 | 2.00-3.00 | L | 2 | –22 | +63 | –13 | +4.51 | |

| 46 | 2.25-3.25 | R | 5 | +48 | +43 | +32 | +4.64 | |

| 10 | 2.75-3.75 | L | 3 | –27 | +58 | –3 | +3.04 | |

| 11 | 3.25-4.25 | L | 16 | –22 | +43 | –3 | +4.17 | |

| Superior parietal | 7 | 4.00-5.00 | R | 2 | +28 | –62 | +52 | –3.00 |

| Superior temporal | 38 | 4.00-5.00 | R | 13 | +53 | +13 | –28 | +4.11 |

| Supramarginal | 40 | 4.00-5.00 | R | 2 | +58 | –47 | +32 | –2.73 |

| Visible Condition | ||||||||

| Cerebellum | – | 2.75-3.75 | R | 15 | +28 | –62 | –18 | –2.86 |

| – | 3.25-4.25 | R | 2 | +33 | –52 | –18 | –2.60 | |

| Cuneus | 7 | 0.25-1.25 | L | 4 | –17 | –72 | +32 | –3.81 |

| 18/19 | 1.75-2.75 | L | 3 | –17 | –87 | +22 | –3.17 | |

| 19 | 1.75-2.75 | L | 2 | –7 | –92 | +27 | –5.06 | |

| 18/19 | 2.75-3.75 | L | 16 | –12 | –82 | +27 | –3.66 | |

| 18 | 3.00-4.00 | L | 21 | -17 | –77 | +22 | –3.80 | |

| 18 | 3.75-4.75 | L | 11 | +8 | –77 | +22 | –3.67 | |

| Medial frontal | 6 | 1.50-2.50 | L | 2 | –7 | –7 | +57 | –2.79 |

| Middle frontal | 47 | 0.25-1.25 | L | 2 | –32 | +38 | –3 | –2.96 |

| Paracentral | 6 | 0.00-1.00 | L | 3 | –12 | –27 | +52 | –3.08 |

| 3/4 | 0.25-1.25 | L | 2 | –12 | –37 | +57 | –4.12 | |

| 5 | 2.75-3.75 | L | 13 | –17 | –42 | +57 | –3.92 | |

| Parahippocampal | 35 | 1.75-2.75 | L | 3 | –17 | –32 | –8 | +3.41 |

| Postcentral | 5 | 0.25-1.25 | L | 2 | –12 | –42 | +62 | –3.81 |

| 3 | 0.50-1.50 | L | 9 | –12 | –37 | +67 | –3.77 | |

| Precuneus | 7 | 2.50-3.50 | L | 24 | –22 | –62 | +37 | –4.05 |

| Superior frontal | 6/8 | 3.25-4.25 | L | 3 | –17 | +28 | +52 | +4.08 |

| 6/8 | 3.75-4.75 | R | 4 | +13 | +33 | +52 | +3.93 | |

| Superior temporal | 22 | 2.50-3.50 | L | 2 | –62 | –52 | +12 | +3.04 |

Note: Size refers to the number of contiguous voxels (5mm3) surviving multiple comparison correction (i.e., false discovery rate < 5%). Coordinates of local maxima are in mm units and correspond to standardized Talairach space. BA = Brodmann Area.

Figure 2.

Peak differences in regional theta (4-8 Hz) activity in right medial temporal cortices between healthy controls (N = 19) and depressed patients (N = 19) on hidden platform trials. Coronal and sagittal views of differential activations are overlayed on an averaged anatomical MRI, presented in radiological orientation (left = right, right = left). Bar graphs show mean theta power by Group and Condition at the local maximum for each time window depicted in the images. *false discovery rate < 5%.

Other regions showing greater theta activity in healthy controls relative to patients included multiple loci in lateral prefrontal cortices. Conversely, greater theta activity in the cerebellum and posterior cortical regions was observed in patients relative to controls. Post hoc analyses found no significant differences in theta activity between patients with and without co-morbid anxiety disorders within regions showing patient-control group differences when corrected for multiple comparisons. Finally, few regions exhibited group differences in activity for the visible condition. Healthy controls exhibited greater activity in dorsal prefrontal cortical regions and, in one instance, left parahippocampal cortices compared to patients. Patients exhibited greater theta activity than controls in the cerebellum and posterior parietal cortices.

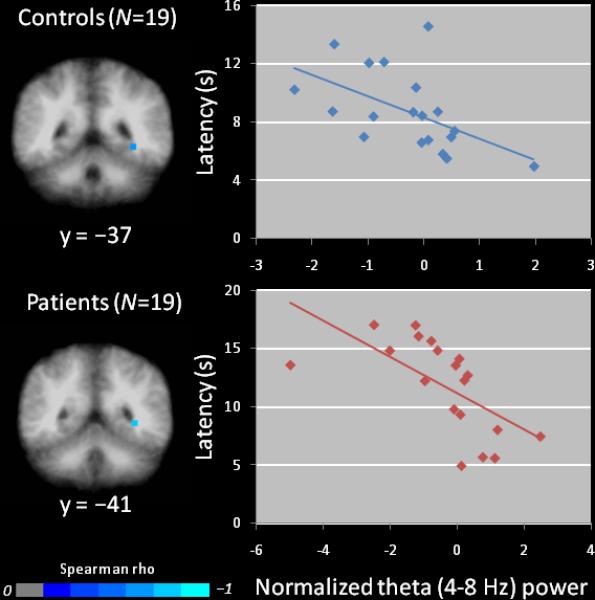

Regional theta – navigation performance correlations

Correlation analyses demonstrated that left posterior hippocampal/parahippocampal theta activity was negatively correlated with mean latency to reach the hidden platform (i.e., greater theta was associated with better performance) in both patients and controls (Figure 3). Time windows in which these correlations were observed differed between groups, with patients showing this correlation at 3.00-4.00 s and controls at 1.25-2.25 s relative to trial onset. Other regions with at least two contiguous voxels showing negative correlations of a similar magnitude commonly across groups in any time window included the following: left precuneus (Brodmann Area (BA) 7, xyz = −4, −49, 42), right precentral gyrus (BA 4, xyz = 21, −23, 59), right precuneus (BA 7, xyz = 3, −37, 45) and right middle frontal gyrus (BA 10, xyz = 36, 43, 22).

Figure 3.

Peak Spearman correlations between regional theta activity and navigation performance in healthy controls (top) and depressed patients (bottom). Coronal images are in radiological orientation (left = right, right = left). Scatterplots, with least-squares lines, depict inverse relationships between regional theta activity in left posterior hippocampus at 1.25-2.25 s in healthy controls during navigation (rs(17) = −.66, p < .005 and at 3.00-4.00 s in depressed patients (rs(17) = −.81, p < .005) and mean latency to reach the hidden platform across 20 trials (i.e., greater theta activity associated with better performance).

Discussion

We investigated neural correlates of spatial navigation deficits in depressed patients (9) using a virtual analogue of the Morris water maze task. Whole-head MEG recordings were collected as depressed patients and healthy controls navigated the water maze. For both mean latency and path length to the hidden platform (Figure 1), patients showed impaired navigation performance compared to controls, replicating results obtained from depressed patients performing a different virtual navigation task (9). Source analyses revealed group differences in regional theta (4-8 Hz) activity during navigation, including reduced oscillatory activity in right anterior hippocampus and parahippocampal cortices in patients relative to healthy controls. These findings provide evidence of abnormal hippocampal and parahippocampal cortical functioning in major depressive disorder, complementing evidence for structural abnormalities in this population.

Our data point to spatial navigation deficits in depressed patients being the result of dysfunction of right anterior medial temporal structures (Figure 2). A recent meta-analysis of morphometric studies found evidence of bilateral volumetric reductions of the hippocampus in depressed patients (4), suggesting the absence of lateralized changes; but both functional imaging (7) and post-mortem (33) evidence points to abnormalities in the right hippocampus only like the present results. Theta activity in this right anterior region, however, did not correlate with navigation performance at the individual level within groups. Instead, left posterior hippocampal theta activity was positively correlated with performance within both groups (Figure 3), replicating previous findings (18). Posterior regions are widely believed to be especially critical to spatial navigation in animals (34) and humans (35), and the within-group correlations observed here are consistent with this view. Anterior regions have also been implicated in spatial navigation, and seem to play a role limited to early encoding of novel environments, showing decreased activity as navigation performance improves (18, 35). Anterior hippocampal and parahippocampal dysfunction in patients indicates they fail to initially encode the spatial layout in a way that optimizes navigation to the hidden platform.

Reduced activity of lateral prefrontal cortices in patients (Table 2), which may be indicative of spatial working memory dysfunction (36)), supports evidence of generalized deficits in visuospatial processing and working memory in depression (37, 38). Moreover, patients performed worse than controls on visible platform trials in addition to hidden platform trials, at least in terms of path length to the visible platform, implying that inferior performance in depressed patients might be partly explained by basic sensorimotor difficulties. Potential sensorimotor coordination deficits, though, cannot account for greater group differences in navigating to the hidden platform compared to group differences in navigating to the visible platform as the sensorimotor demands were the same in both conditions. Psychomotor retardation and diminished motivation associated with depression might be other factors to consider; however, their impact seems negligible as patients were just as fast as controls in reaching the visible platform, and faster in initiating movement in both conditions, which would not be expected if patients exhibited significant psychomotor retardation or lacked motivation to perform the task. In total, inferior performance of depressed patients in navigating to the hidden platform can be attributed primarily to spatial learning deficits.

The significance of our findings linking hippocampal and parahippocampal dysfunction to major depressive disorder must be tempered by the following considerations. First, 47% (9/19) of our patients had a current anxiety disorder. Because anxious depression is associated with worse outcome and more severe impairment than non-anxious depression (39), concerns arise about whether our evidence of hippocampal and parahippocampal dysfunction applies only to these more severely ill patients or to the presence of clinical anxiety symptoms. Within the patient group, there was no evidence that the degree of behavioral impairment or level of hippocampal and parahippocampal activity differed between those with and those without an anxiety disorder. It is unlikely, therefore, that patient-control group differences were driven predominantly by patients with anxious depression. Anxiety may, nevertheless, be a mediating factor for which future research may need to consider with a larger sample of anxious and non-anxious MDD patients (40). Finally, because our patients were currently depressed with moderate-to-severe symptoms, we are unable to determine whether hippocampal and parahippocampal dysfunction is state-dependent or also present in those at risk for depression.

With mounting evidence of hippocampal structural abnormalities in major depressive disorder, we observed clear reductions of right anterior hippocampal and parahippocampal oscillatory activity in depressed individuals during a virtual reality task in which they showed impaired spatial navigation. These observations suggest that together with volumetric reductions of the hippocampus in depressed patients reported elsewhere, the right anterior hippocampus and parahippocampal cortices function abnormally in depressed patients. Whether a contributing factor or consequence, abnormal functioning of these structures is likely to have pervasive effects on cognition and affect in those who suffer from depression. Virtual navigation tasks, combined with neuroimaging, provide a tool to expand on the significance of hippocampal dysfunction for the pathophysiology of major depressive disorder.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health and a National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression Award (CZ).

Footnotes

Preliminary results of this study were presented as a poster at the 63rd Annual Meeting and Convention of the Society of Biological Psychiatry, Washington D.C., May 1-3, 2008.

Disclosures: The author(s) declare that, except for income received from our primary employer, no financial support or compensation has been received from any individual or corporate entity over the past three years for research or professional service and there are no personal financial holdings that could be perceived as constituting a potential conflict of interest. A patent application for the use of ketamine in depression has been submitted listing Drs. Manji and Zarate among the inventors. Drs. Manji and Zarate have assigned their rights on the patent to the U.S. government. Dr. Manji is now Vice President, CNS and Pain, Johnson and Johnson Pharmaceutical Research and Development.

Financial Disclosures

The author(s) declare that, except for income received from our primary employer, no financial support or compensation has been received from any individual or corporate entity over the past three years for research or professional service and there are no personal financial holdings that could be perceived as constituting a potential conflict of interest. A patent application for the use of ketamine in depression has been submitted listing Drs. Manji and Zarate among the inventors. Drs. Manji and Zarate have assigned their rights on the patent to the U.S. government. Dr. Manji is now Vice President, CNS and Pain, Johnson and Johnson Pharmaceutical Research and Development.

References

- 1.Perera TD, Park S, Nemirovskaya Y. Cognitive role of neurogenesis in depression and antidepressant treatment. Neuroscientist. 2008;14(4):326–338. doi: 10.1177/1073858408317242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sahay A, Hen R. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis in depression. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(9):1110–1115. doi: 10.1038/nn1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell S, Marriott M, Nahmias C, MacQueen GM. Lower hippocampal volume in patients suffering from depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(4):598–607. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Videbech P, Ravnkilde B. Hippocampal volume and depression: a meta-analysis of MRI studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(11):1957–1966. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McEwen BS. Glucocorticoids, depression, and mood disorders: structural remodeling in the brain. Metabolism. 2005;54(5 Suppl 1):20–23. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sapolsky RM. Glucocorticoids and hippocampal atrophy in neuropsychiatric disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(10):925–935. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.10.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Videbech P, Ravnkilde B, Pedersen AR, Egander A, Landbo B, Rasmussen NA, Andersen F, Stodkilde-Jorgensen H, Gjedde A, Rosenberg R. The Danish PET/depression project: PET findings in patients with major depression. Psychol Med. 2001;31(7):1147–1158. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sweeney JA, Kmiec JA, Kupfer DJ. Neuropsychologic impairments in bipolar and unipolar mood disorders on the CANTAB neurocognitive battery. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(7):674–684. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00910-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gould NF, Holmes MK, Fantie BD, Luckenbaugh DA, Pine DS, Gould TD, Burgess N, Manji HK, Zarate CA., Jr. Performance on a virtual reality spatial memory navigation task in depressed patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(3):516–519. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.3.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maguire EA, Burgess N, O'Keefe J. Human spatial navigation: cognitive maps, sexual dimorphism, and neural substrates. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1999;9(2):171–177. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)80023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ekstrom AD, Caplan JB, Ho E, Shattuck K, Fried I, Kahana MJ. Human hippocampal theta activity during virtual navigation. Hippocampus. 2005;15(7):881–889. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kahana MJ, Sekuler R, Caplan JB, Kirschen M, Madsen JR. Human theta oscillations exhibit task dependence during virtual maze navigation. Nature. 1999;399(6738):781–784. doi: 10.1038/21645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buzsaki G. Theta rhythm of navigation: link between path integration and landmark navigation, episodic and semantic memory. Hippocampus. 2005;15(7):827–840. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Keefe J, Recce ML. Phase relationship between hippocampal place units and the EEG theta rhythm. Hippocampus. 1993;3(3):317–330. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450030307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris RGM. Spatial localization does not require the presence of local cues. Learn Motivat. 1981;12:239–260. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris RG, Garrud P, Rawlins JN, O'Keefe J. Place navigation impaired in rats with hippocampal lesions. Nature. 1982;297(5868):681–683. doi: 10.1038/297681a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Astur RS, Taylor LB, Mamelak AN, Philpott L, Sutherland RJ. Humans with hippocampus damage display severe spatial memory impairments in a virtual Morris water task. Behav Brain Res. 2002;132(1):77–84. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00399-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cornwell BR, Johnson LL, Holroyd T, Carver FW, Grillon C. Human hippocampal and parahippocampal theta during goal-directed spatial navigation predicts performance on a virtual Morris water maze. J Neurosci. 2008;28(23):5983–5990. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5001-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shipman SL, Astur RS. Factors affecting the hippocampal BOLD response during spatial memory. Behav Brain Res. 2008;187(2):433–441. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson SE, Vrba J. Functional neuroimaging by synthetic aperture magnetometry (SAM). In: Yoshimoto T, Kotani M, Kuriki S, Karibe H, Nakasato N, editors. Recent Advances in Biomagnetism. Tohoku Univ. Press; Sendai: 1999. pp. 302–305. [Google Scholar]

- 21.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams AR. Structured Clinical Interview for DSMIV TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P) edn) New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders IV edn) American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Brit J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.First MB, Spitzer RL, Williams AL, Gibbon M. Structured Clinical Interview from DSM-IV (SCID) edn) American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hillebrand A, Singh KD, Holliday IE, Furlong PL, Barnes GR. A new approach to neuroimaging with magnetoencephalography. Hum Brain Mapp. 2005;25(2):199–211. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh KD, Barnes GR, Hillebrand A, Forde EM, Williams AL. Task-related changes in cortical synchronization are spatially coincident with the hemodynamic response. Neuroimage. 2002;16(1):103–114. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cornwell BR, Carver FW, Coppola R, Johnson L, Alvarez R, Grillon C. Evoked amygdala responses to negative faces revealed by adaptive MEG beamformers. Brain Res. 2008;1244:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.09.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salvadore G, Cornwell BR, Colon-Rosario V, Coppola R, Grillon C, Zarate CA, Jr., Manji HK. Increased anterior cingulate cortical activity in response to fearful faces: a neurophysiological biomarker that predicts rapid antidepressant response to ketamine. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(4):289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res. 1996;29(3):162–173. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Astur RS, Ortiz ML, Sutherland RJ. A characterization of performance by men and women in a virtual Morris water task: a large and reliable sex difference. Behav Brain Res. 1998;93(1-2):185–190. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(98)00019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Driscoll I, Hamilton DA, Petropoulos H, Yeo RA, Brooks WM, Baumgartner RN, Sutherland RJ. The aging hippocampus: cognitive, biochemical and structural findings. Cereb Cortex. 2003;13(12):1344–1351. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhg081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Genovese CR, Lazar NA, Nichols T. Thresholding of statistical maps in functional neuroimaging using the false discovery rate. Neuroimage. 2002;15(4):870–878. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dunham JS, Deakin JF, Miyajima F, Payton A, Toro CT. Expression of hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its receptors in Stanley consortium brains. J Psychiatr Res. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.03.008. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moser E, Moser MB, Andersen P. Spatial learning impairment parallels the magnitude of dorsal hippocampal lesions, but is hardly present following ventral lesions. J Neurosci. 1993;13(9):3916–3925. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-09-03916.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maguire EA, Woollett K, Spiers HJ. London taxi drivers and bus drivers: a structural MRI and neuropsychological analysis. Hippocampus. 2006;16(12):1091–1101. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wager TD, Smith EE. Neuroimaging studies of working memory: a meta-analysis. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2003;3(4):255–274. doi: 10.3758/cabn.3.4.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hinkelmann K, Moritz S, Botzenhardt J, Riedesel K, Wiedenmann K, Kellner M, Otte C. Cognitive impairment in major depression: association with salivary cortisol. Biol Psychiatry. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.06.023. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor-Tavares JV, Clark L, Cannon DM, Erickson K, Drevets WC, Sahakian BJ. Distinct profiles of neurocognitive function in unmedicated unipolar depression and bipolar II depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(8):917–924. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fava M, Rush AJ, Alpert JE, Balasubramani GK, Wisniewski SR, Carmin CN, Biggs MM, Zisook S, Leuchter A, Howland R, Warden D, Trivedi MH. Difference in treatment outcome in outpatients with anxious versus nonanxious depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(3):342–351. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mueller SC, Temple V, Cornwell B, Grillon C, Pine DS, Ernst M. Impaired spatial navigation in pediatric anxiety. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02112.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02112.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]