Abstract

Meiotic progression is driven by the sequential translational activation of maternal messenger RNAs stored in the cytoplasm. This activation is mainly induced by the cytoplasmic elongation of their poly(A) tails, which is mediated by the cytoplasmic polyadenylation element (CPE) present in their 3′ untranslated regions. Although polyadenylation in prophase I and metaphase I is mediated by the CPE-binding protein 1 (CPEB1), this protein is degraded during the first meiotic division. Thus, raising the question of how the cytoplasmic polyadenylation required for the second meiotic division is achieved. In this work, we show that CPEB1 generates a positive loop by activating the translation of CPEB4 mRNA, which, in turn, replaces CPEB1 and drives the transition from metaphase I to metaphase II. We further show that CPEB1 and CPEB4 are differentially regulated by phase-specific kinases, generating the need of two sequential CPEB activities to sustain cytoplasmic polyadenylation during all the meiotic phases. Altogether, this work defines a new element in the translational circuit that support an autonomous transition between the two meiotic divisions in the absence of DNA replication.

Keywords: CPEB1, CPEB4, cytoplasmic polyadenylation, meiosis, Xenopus oocytes

Introduction

Vertebrate immature oocytes are arrested at prophase of meiosis I (PI). During this growth period, the oocytes synthesize and store large quantities of dormant mRNAs, which will later drive the oocyte's re-entry into meiosis (Mendez and Richter, 2001; Radford et al, 2008). The resumption of meiosis in Xenopus is stimulated by progesterone, which carries the oocyte through two consecutive M-phases (MI and MII), without intervening S-phase (Iwabuchi et al, 2000), to a second arrest at MII. Remarkably, oocyte maturation occurs in the absence of transcription (Newport and Kirschner, 1982) and is fully dependent on the sequential translational activation of the maternal mRNAs accumulated during the PI arrest (reviewed in Belloc et al, 2008). The most extensively studied mechanism to maintain repressed maternal mRNAs in arrested oocytes and to activate translation during meiotic resumption is mediated by the cytoplasmic polyadenylation element (CPE) present in the 3′ UTRs of responding mRNAs. The CPE recruits the CPE-binding protein 1 (CPEB1), which assembles a translational repression complex in the absence of progesterone and mediates cytoplasmic polyadenylation and translational activation on progesterone stimulation. Activated CPEB1 recruits the cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor (CPSF) to the nearby polyadenylation hexanucleotide (Hex), and, together, they recruit the cytoplasmic poly(A) polymerase GLD2 (for reviews see Mendez and Richter, 2001; Richter, 2007; Radford et al, 2008). Nevertheless, the activation of CPE-containing mRNAs does not occur in masse at any one time (Belloc et al, 2008). Instead, the polyadenylation of specific mRNAs is temporarily regulated (Ballantyne et al, 1997; de Moor and Richter, 1997) by two sequential phosphorylations of CPEB1. First, the phosphorylation of CPEB1 by Aurora A kinase at PI, which is required for the first or ‘early' wave of polyadenylation and the PI–MI transition (Mendez et al, 2000a, 2000b; Pique et al, 2008); although see (Keady et al, 2007). Second, the phosphorylation by Cdc2 and Plx1 at MI, which targets CPEB1 for degradation and is necessary to activate the second or ‘late' wave of polyadenylation and the MI–MII transition (Reverte et al, 2001; Mendez et al, 2002; Setoyama et al, 2007; Pique et al, 2008). This CPEB1 degradation, however, results in very low levels of this protein for the second meiotic division, when a third or ‘late–late' wave of cytoplasmic polyadenylation is essential for MII entry and cytostatic factor (CSF) arrest (Belloc and Mendez, 2008). In addition, Aurora A kinase is inactivated during interkinesis (Ma et al, 2003; Pascreau et al, 2008) concomitantly with increased levels of PPI, which dephosphorylates CPEB1 Ser 174 (Tay et al, 2003; Belloc and Mendez, 2008).

The reduced CPEB1 activity after anaphase I (AI) raise the question of how the polyadenylation machinery is recruited to the mRNAs activated in the third wave. Recently, three additional genes encoding CPEB-like proteins have been identified in vertebrates (Mendez and Richter, 2001; Kurihara et al, 2003; Theis et al, 2003), thus opening the possibility that other members of the CPEB family could compensate for the degradation of CPEB1 in the first meiotic division. As CPEB2 and CPEB3 have been shown not to mediate cytoplasmic polyadenylation or translational activation, but rather to act only as translational repressors (Huang et al, 2006; Hagele et al, 2009; Novoa et al, 2010), we focused our study in the expression and function of CPEB4. Here, we show that CPEB4 is encoded by a maternal mRNA that is translationally activated by CPEB1 in response to progesterone, leading to the accumulation of the protein in the second meiotic division. CPEB4, in turn, recruits the cytoplasmic poly(A) polymerase GLD2 to CPE-regulated mRNAs and is required for MI–MII progression. On the basis of these findings, we propose that CPEB1 establishes a new meiotic circuit by activating the synthesis of CPEB4, which, in turn, compensates for the inactivation and degradation of CPEB1 by mediating cytoplasmic polyadenylation in the second meiotic division.

Results

CPEB4 is encoded by a maternal mRNA activated by CPEB1-mediated cytoplasmic polyadenylation

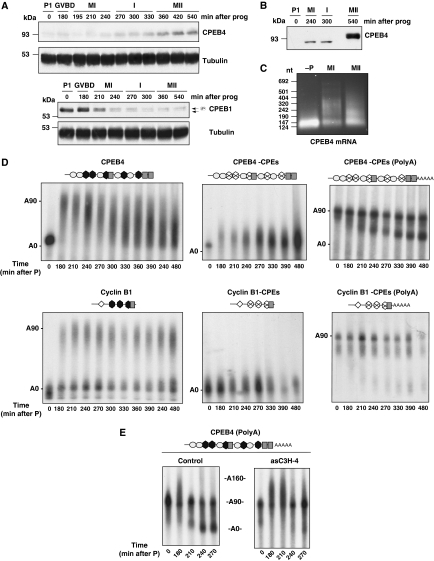

To determine whether CPEB4 was expressed in oocytes, and could therefore be a candidate to replace CPEB1 function after MI, we first cloned the previously uncharacterized Xenopus laevis CPEB4 (Supplementary Figure S1), raised antibodies against this protein and analysed its expression in a meiotic time course. CPEB4 was present at very low levels in PI and gradually accumulated in response to progesterone, reaching maximal levels in the second meiotic division (Figure 1A). Although the levels of CPEB4 in MI were much lower that in MII, we were able to detect a significant accumulation of CPEB4 in MI compared with PI-arrested oocytes (Figure 1B). In this panel, it is also readily appreciable that CPEB4 becomes hyperphosphorylated in MII, resulting in slower electrophoretic mobility. Interestingly, CPEB4 followed an expression pattern complementary to that of CPEB1, which was highly expressed in PI-arrested oocytes and also in MI, but was degraded and virtually disappeared in MII-arrested oocytes (Figure 1A). Contrary to CPEB1 (Hake and Richter, 1994), CPEB4 levels remained stable after fertilization and even after the mid-blastula transition (Supplementary Figure S2). As the expression pattern of CPEB4 was consistent with this factor being encoded by a maternal mRNA, that is silenced in PI-arrested oocytes and translationally activated by cytoplasmic polyadenylation in response to progesterone, we measured the poly(A) tail length of the endogenous CPEB4 mRNA (Figure 1C). The CPEB4 transcript, which contained a short-poly(A) tail in PI oocytes, was polyadenylated in metaphase I (MI) and partially deadenylated in the second meiotic arrest at metaphase II (MII).

Figure 1.

CPEB4 mRNA polyadenylation results in CPEB4 accumulation during the second meiotic division. (A) Xenopus oocytes stimulated with progesterone (prog) were collected at the indicated times and analysed by western blotting using anti-CPEB4, anti-CPEB1 or anti-tubulin antibodies. The meiotic phases of the oocyte are indicated (PI, prophase I; GVBD, germinal vesicle breakdown; MI, metaphase I; I, interkinesis; MII, metaphase II). GVBD was determined by the appearance of the white spot at the animal pole of the oocyte. (B) Xenopus oocytes, untreated or stimulated with progesterone (prog), were collected at the indicated times and analysed by western blotting using anti-CPEB4. The meiotic phases of the oocyte are indicated (PI, prophase I; MI, metaphase I; I, interkinesis; MII, metaphase II). (C) Total RNA extracted from oocytes untreated (−P) or incubated with progesterone and collected at metaphase I (MI) and metaphase II (MII) were analysed by RNA-ligation-coupled RT–PCR. (D) Oocytes were injected with the indicated radiolabelled 3′ UTRs. Total RNA was extracted from oocytes collected at the indicated times after progesterone stimulation and analysed by gel electrophoresis followed by autoradiography. Schematic representation of the 3′ UTRs is shown: CPEs as dark grey hexagons, Hexanucleotide as grey boxes, PBEs as rhombus, putative AREs elements as light grey ovals. CPE point mutations are indicated as a cross. (E) Oocytes were injected with C3H-4 anti-sense oligonucleotide (asC3H-4) or C3H-4 sense oligonucleotide (control). After 16 h, oocytes were injected with the indicated radiolabelled 3′ UTRs. Total RNA was extracted from oocytes collected at the indicated times after progesterone stimulation and analysed by gel electrophoresis followed by autoradiography.

To get further insight into the translational regulation of CPEB4 mRNA, the 3′ UTR of the endogenous transcript was identified and cloned (Supplementary Figure S1C). CPEB4 3′ UTR contains three potential Hexs, five potential CPEs and three long AU-rich stretches with potential AREs. To assess whether these elements mediate the polyadenylation behaviour observed for the endogenous CPEB4 mRNA, we in vitro transcribed and microinjected labelled probes corresponding to the WT or mutant variants of CPEB4 3′ UTR (Figure 1C). The WT probe (CPEB4 3′ UTR) displayed the same polyadenylation pattern than the endogenous CPEB4 mRNA, being polyadenylated in MI and then partially deadenylated during interkinesis and in MII. As control, we microinjected the 3′ UTR of cyclin B1 (cyclin B1 3′ UTR), which contained CPEs but not AREs (Belloc and Mendez, 2008), and was polyadenylated in MI remaining polyadenylated thereafter. These progesterone-induced polyadenylations were abrogated when the putative CPEs were inactivated by point mutations (CPEB4 3′ UTR-CPEs and cyclin B1 3′ UTR-CPEs; see Supplementary Figure S3 for sequence of the 3′ UTR variants). When the same UTRs were microinjected with a long poly(A) tail (CPEB4 3′ UTR-CPEs (polyA) and cyclin B1 3′ UTR-CPEs (poly(A)), the CPEB4- but not the cyclin B1-derived probe was specifically deadenylated after MI. To test whether this deadenylation was mediated by the recruitment of C3H-4, which is an ARE-binding protein that is synthesized from a maternal mRNA activated from the first wave of cytoplasmic polyadenylation and that modulates deadenylation of ARE-containing mRNAs after GVBD (Belloc and Mendez, 2008), we microinjected the CPEB4 3′ UTR probe in oocytes depleted of C3H-4. The deadenylation of CPEB4 3′ UTR was prevented in C3H-4-depleted oocytes (Figure 1D). Altogether, these results indicate that CPEB4 mRNA is a maternal transcript stored inactive in PI-arrested oocytes, polyadenylated in MI by CPEB, and partially deadenylated in the second meiotic division by C3H-4.

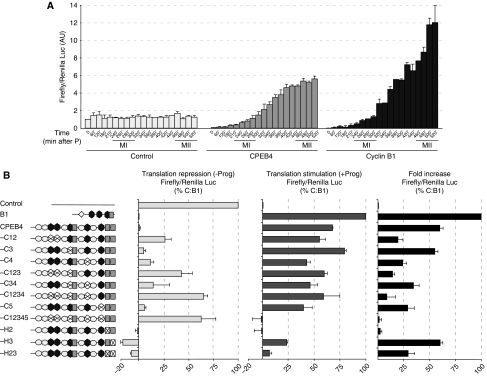

To determine whether the observed changes in poly(A) tail length were reflected at the translational level, we microinjected chimaeric mRNAs with the luciferase ORF followed by WT or mutant CPEB4 3′ UTRs (see Supplementary Figure S3 for sequences). In a meiotic time course (Figure 2A), both CPEB4 and cyclin B1 3′ UTRs repressed translation in PI-arrested oocytes, compared with a control 3′ UTR. After progesterone stimulation, both CPEB4 and cyclin B1 3′ UTRs mediated translational activation. But, even though the accumulation of luciferase followed the same kinetics at early time points (MI), the increase in luciferase generated from the CPEB4 3′ UTR chimaerical construct slowed down during the second meiotic division, whereas the accumulation of luciferase from the cyclin B1 3′ UTR chimaerical mRNA continued to increase at a similar rate during the whole length of meiosis, until the MII arrest. These translational kinetics are in agreement with the fact that cyclin B1 3′ UTR remains polyadenylated during the two meiotic divisions and CPEB4 3′ UTR is partially deadenylated in the second meiotic division. The translational repression was dependent on the CPE cluster of two consensus CPEs (CPEs 1 and 2), but the translational activation was sustained by either of the two more 3′ CPEs (CPEs 4 or 5) and required the second Hex (Figure 2B). Thus, translational repression was most likely mediated by a CPEB dimer, as shown before for cyclins B UTRs (Pique et al, 2008), whereas the activation required the Hex and the nearby CPE, in agreement with being mediated by ‘early' cytoplasmic polyadenylation (Pique et al, 2008). We conclude from these data that CPEB1 mediates the ‘early' cytoplasmic polyadenylation of CPEB4 mRNA, activating its translation on progesterone stimulation. CPEB4 mRNA is, however, partially deadenylated after C3H-4 accumulation in late MI (Belloc and Mendez, 2008), slowing down translation and leading to the gradual accumulation of CPEB4 that reach its highest levels only at the MII arrest.

Figure 2.

CPEB4 is translationally activated by CPEB1 during meiotic maturation. (A, B) The indicated in vitro transcribed Firefly luciferase chimaerical mRNAs were co-injected into oocytes together with Renilla luciferase as a normalization control. (A) Firefly luciferase ORF fused to a control 3′ UTR of 470 nucleotides (control); cyclin B1 3′ UTR wild type (cyclin B1 3′ UTR) and CPEB4 3′ UTR wild type (CPEB4). Oocytes were stimulated with progesterone, collected at the indicated times and the luciferase activities were measured. Data are mean±s.d. (n=4). (B) The indicated Firefly luciferase-3′ UTR variants were injected in oocytes. Oocytes were then incubated in the absence (repression) or presence (activation) of progesterone and the luciferase activities determined after 6 h. The percentage of translational repression in the absence of progesterone (left panel) was normalized to control (100% translation) and to the fully repressed B1 (0% translation). The percentage of translation stimulation (middle panel) was normalized to control (0% stimulation) and B1 (100% simulation). The total fold increase, as the total stimulation by progesterone for each mRNA normalized to control (0% stimulation) and B1 (100% stimulation) is shown in the further right panel. Data are mean±s.d. (n=5). A schematic representation of the 3′ UTR, as in Figure 1, is shown.

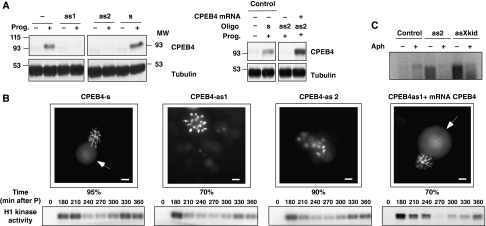

CPEB4 is required for meiotic progression between MI and MII

We then proceeded to ask whether the CPEB1-induced synthesis of CPEB4 was required for meiotic progression once CPEB1 become inactivated/degraded. To this aim, CPEB4 mRNA was ablated by independent microinjection of four different anti-sense oligonucleotides, targeting either the ORF, the 3′ or the 5′ UTRs. These anti-sense oligonucleotides efficiently knocked down CPEB4 synthesis after progesterone stimulation and caused external morphological changes consistent with abnormal meiotic progression (Figure 3A; Supplementary Figure S4). The corresponding sense oligonucleotide was injected as a control. To define the meiotic phenotype resulting from inhibiting CPEB4 synthesis, we monitorized the chromosome dynamics by direct visualization of stained DNA, and the H1 kinase (Cdc2) activity in oocyte extracts from a meiotic time course (Figure 3B). Control oocytes displayed the characteristic DNA staining with extruded polar body and oocyte chromosomes arranged in the metaphasic plate. In addition, cdc2 activity increased in response to progesterone, sharply decreased after MI and augmented again at MII. In CPEB4-depleted oocytes, the polar body was not detectable and the chromosomes were partially decondensed and not arranged in a metaphasic plate, indicating that these oocytes did not complete the first meiotic division. Cdc2 activity in depleted oocytes showed normal stimulation after progesterone and the subsequent partial inactivation, indicating correct meiotic resumption until anaphase I (Figure 3B). At later times, H1 kinase was partially reactivated, most likely as a consequence of oocyte necrosis or apoptosis, which stimulate cdc2 and cdk2 (Zhou et al, 1998). Accordingly, the reactivation of H1 kinase was more evident with the CPEB4as2, which show more apoptotic symptoms than the CPEB4as1 (Figure 3B; Supplementary Figure S4A). At longer times, all the anti-sense-treated oocytes shown DNA fragmentation, indicative of apoptosis, suggesting that oocyte death is a secondary effect of the oocytes failing to progress properly between MI and MII (Supplementary Figure S4B). This phenotype was rescued by overexpressing CPEB4 from a microinjected mRNA not targeted by the anti-sense oligonucleotides (Figures 3A and B).

Figure 3.

CPEB4 synthesis is required for the MI to MII transition. (A, B) Xenopus oocytes were injected with CPEB4 sense (s) or anti-sense (as1, as2) oligonucleotides as indicated and incubated for 16 h. Then, the oocytes were microinjected with CPEB4-enconding mRNA and incubated in the presence or absence of progesterone (prog) as indicated. All the oocytes were collected 4 h after the control, non-injected oocytes, displayed 100% GVBD and analysed as follows. (A) The oocytes were analysed for CPEB4 levels by western blot using anti-CPEB4 and anti-tubulin antibodies (two oocyte equivalents were loaded per lane). (B) Oocytes were fixed, stained with Hoechst and examined under epifluorescence microscope. Representative images and the percentage of appearance for each phenotype are shown. The arrow indicates the first polar body. Scale bar=10 μm. Oocytes collected at the indicated times after progesterone stimulation were analysed for H1 kinase activity as described in Materials and methods. (C) Oocytes injected with CPEB4 anti-sense oligonucleotide (as2), CPEB4 sense oligonucleotide (control) and Xkid anti-sense oligonucleotide (asXkid) were incubated for 16 h and then injected with 0.4 μCi [α-32P]dCTP. Then, the oocytes were stimulated with progesterone and incubated in the presence or absence of Aphydicolin (Aph) as indicated. Oocytes were collected 5 h after control oocytes displayed 100% GVBD, DNA was extracted and analysed by agarose gel electrophoresis followed by autoradiography.

To further characterize the meiotic defect originated by preventing CPEB4 synthesis, we analysed whether DNA replication was activated, denoting exit from meiosis between MI and MII (Figure 3C). Measurement of the incorporation of microinjected-labelled dCTP into DNA demonstrated that, although control oocytes did not synthesize DNA in the course of a normal meiosis, new DNA was indeed generated in CPEB4-depleted oocytes. As a positive control, we depleted Xkid mRNA, which causes meiotic exit and DNA synthesis after MI (Perez et al, 2002). The incorporation of labelled dCTP was sensitive to aphydicoline, revealing that DNA replication, rather than DNA repair, was taking place (Furuno et al, 1994). Collectively, these data illustrate that CPEB4-depleted oocytes progress from PI to MI, but failed to transition between MI and MII and, instead, exit meiosis replicating the DNA. Thus, although GBVD (MI entry) takes place normally, as detected by the formation of the characteristic white spot, chromosomes were not segregated and the first meiotic division was not completed, as shown by the lack of polar body extrusion and the absence of a properly assembled metaphasic plate. Biochemically, MPF was activated as in control oocytes (Figure 3B, lower panels), indicating normal entry into MI, and later inactivated, indicating that the APC was active even if chromosomes were not segregated. Therefore, we concluded that depletion of CPEB4 resulted in meiotic arrest/exit in the transition between MI and AI. At this point, chromosomes partially decondensed and premature DNA replication takes place. In turn, this incomplete meiotic progression results in oocyte degeneration, which has been previously reported to be associated with reactivation of histone H1 kinase, cleavage of Frodin and DNA fragmentation (Perez et al, 2002; Eliscovich et al, 2008), all indicative of apoptosis. Although at the MI–AI transition the levels of CPEB4 detected by western blot are low compared with MII levels (Figure 1B), but significantly increased over PI-arrested oocytes, it is clear that these ‘low' levels of newly synthesized CPEB4 are essential for correct meiotic progression. This phenotype contrast with the inhibition of CPEB1 activity, either by microinjecting neutralizing antibodies (Stebbins-Boaz et al, 1996) or by overexpressing a dominant-negative mutant (Mendez et al, 2000a), which results in the inhibition of oocyte maturation (MI entry), as detected by the absence of white spot formation (GVBD) and MPF activation. Thus, CPEB1 and CPEB4 have sequential functions during meiotic progression, CPEB1 being required for the PI–MI transition and CPEB4 for the MI–MII transition.

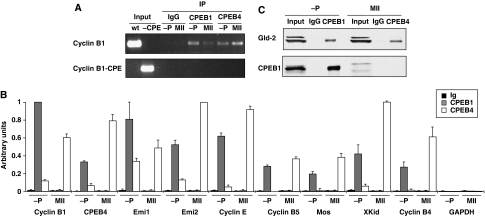

Both CPEB1 and CPEB4 recruit the polyadenylation machinery to CPE-regulated mRNAs, but at different meiotic phases

As the CPE-regulated mRNAs required for cdc2 reactivation and CSF activity in the second meiotic division are polyadenylated in the third or ‘late–late' meiotic wave (Belloc and Mendez, 2008), when CPEB1 levels are negligible, we next sought to determine whether CPEB4 could also bind to these mRNAs, thus substituting CPEB1 function. We first tested whether CPEB4 was able to bind cyclin B1 3′ UTR in a CPE-dependent manner. Oocytes were microinjected with WT cyclin B1 3′ UTR or with a variant in which the CPEs were inactivated by point mutations. Then, the association of CPEB1 and CPEB4 to these reporters was analysed by IP followed by RT–PCR (Figure 4A). Both proteins co-immunoprecipitated the WT UTR, but not the mutant UTR. Interestingly, for CPEB1, the amount of immunoprecipitated probe was larger in the first meiotic division than in the second, whereas for CPEB4, the proportion was reverted with higher binding in MII (Figure 4A). Once determined that CPEB4 recognizes the same CPEs than CPEB1, we assessed the association of both proteins to ‘early' polyadenylated (CPEB4, Emi1, mos and cyclin B5), ‘late' polyadenylated (cyclin B1) and ‘late–late' polyadenylated (Emi2 and cyclin E) endogenous mRNAs (Figure 4B). We found that CPEB4 was bound to all (‘early', ‘late', ‘late–late', weak-polyadenylated and strong-polyadenylated (Belloc and Mendez, 2008; Pique et al, 2008)) CPE-regulated mRNAs in MII. CPEB1 was bound to the same mRNAs in PI, but not in MII. As a negative control, GAPDH was not associated with CPEB1 or CPEB4. Thus, CPEB1 and CPEB4 regulate identical subpopulations of mRNAs in the first and second meiotic divisions, respectively, reflecting the relative levels of these CPEBs at different meiotic phases. Interestingly, CPEB4 was recruited to its own mRNA in MII, suggesting a positive feed back loop that may explain why CPEB4 mRNA is not completely deadenylated by C3H-4.

Figure 4.

CPEB1 and CPEB4 are sequentially associated with CPE-containing mRNAs. (A) Xenopus oocytes were microinjected with in vitro transcribed RNAs derived from WT cyclin B1 3′ UTR (cyclin B1) or the corresponding variant with the CPEs inactivated by point mutations (cyclin B1-CPE). Then, the oocytes were incubated for 8 h in the presence (MII) or absence (−P) of progesterone and subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-CPEB1, anti-CPEB4 and control IgG antibodies followed by RT–PCR for the microinjected RNAs. The PCR products derived from the microinjected (input) and co-immunoprecipitated (IP) RNAs were visualized by stained agarose gel electrophoresis. (B, C) Cytoplasmic extracts from oocytes untreated (−P) or incubated with progesterone for 8 h (MII) were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-CPEB1, anti-CPEB4 and control IgG antibodies. The co-immunoprecipitates were analysed by qRT–PCR for the presence of the indicated mRNAs (B) or by western blotting for the presence of GLD2 and CPEB1 proteins (C). Data are mean±s.d. (n=3).

To verify whether endogenous CPEB4 was able to recruit the polyadenylation machinery, we immunoprecipitated both CPEB1 and CPEB4 and analysed the co-immunoprecipitates for the presence of cytoplasmic poly(A) polymerase GLD2. Both proteins were equally able to recruit GLD2 (Figure 4C). To rule out that the co-immunoprecipitation of GLD2 by CPEB4 was through association with CPEB1, we also analysed the immunoprecipitates for the presence of CPEB1. CPEB4 did not co-immunoprecipitate CPEB1 in MII (Figure 4C), indicating that both CPEBs are not bound to the same mRNA, and that the association of GLD2 and CPEB4 is not indirectly mediated through a potential dimerization with CPEB1. Thus, both CPEB1 and CPEB4 recruit the polyadenylation machinery to CPE-regulated mRNAs, but at different meiotic phases.

Differential regulation of CPEB1 and CPEB4 underlies the requirement for two distinct CPEBs to complete meiosis

We next sought to elucidate why two different CPEBs are required to complete meiosis and why CPEB1 has to be replaced by CPEB4 to sustain the polyadenylation of the same mRNAs. Thus, we first asked whether CPEB1 and CPEB4 were functionally equivalent, by substituting CPEB4 with a non-degradable CPEB1 in the second meiotic division. For this purpose, we overexpressed a non-degradable form of CPEB1. This CPEB1 had the cdc2-phosphorylated residues substituted by alanines (CPEB1-CA), but still contains the regulatory ser 174, targeted by Aurora A kinase and required to activate CPEB1 (Mendez et al, 2000a). Phosphorylation of CPEB1 by Cdc2 is required for its degradation at anaphase I (Mendez et al, 2002; Setoyama et al, 2007). To avoid the meiotic arrest caused by overexpressing high levels of non-degradable CPEB1 in PI (Mendez et al, 2002), we microinjected a deadenylated mRNA encoding CPEB1-CA, which drove the accumulation CPEB1-CA to similar levels than WT-CPEB in PI, but predominantly after GVBD (Figure 5A), and, therefore, without interfering with meiotic progression (Figure 5B). This pattern of overexpression of CPEB1-CA had no major effects in the polyadenylation of cyclin B1 mRNA (Figure 5C). Depletion of CPEB4 caused a meiotic blockage after MI (Figures 3B and 5B) and partially prevented the polyadenylation of the ‘late–late' mRNA encoding cyclin E (Figure 5D), but did not affect the polyadenylation of cyclin B1 mRNA (Figure 5D), consistently with this transcript being polyadenylated by CPEB1 in MI, before CPEB4 accumulates. However, the non-degradable CPEB1 was not able to compensate for the lack of CPEB4 in the second meiotic division; if anything, the phenotype was even aggravated (Figure 5B). Accordingly, polyadenylation of the ‘late' cyclin E mRNA was not rescued by expressing CPEB1-CA (Figure 5D). Surprisingly, substitution of CPEB4 by CPEB1 resulted in a shortened poly(A) tail for cyclin B1 (Figure 5D). As this is an mRNA polyadenylated by CPEB1 and this polyadenylation was not affected by overexpressing CPEB1-CA (Figure 5C) in the presence of CPEB4, this result indicates that replacement of CPEB1 by CPEB4 after anaphase I is not only required to sustain the polyadenylation of the ‘late–late' mRNAs, but also to prevent the deadenylation of the previously CPEB1-polyadenylated mRNAs. Therefore, degradation of CPEB1 and new synthesis of CPEB4 in late meiosis seems to be required to prevent deadenylation during interkinesis of the mRNAs polyadenylated by CPEB1 during PI–MI, whereas maintaining the oocyte capability to generate the third wave of ‘late–late' polyadenylation. Considering that both CPEB1 and CPEB4 share multiple ‘early' and ‘late' mRNA targets (Figure 4B), the interkinesis deadenylation inhibition should not be limited to cyclin B1 mRNA, but, most likely, would be a general effect to all CPEB1/CPEB4-regulated mRNAs. Thus, we concluded that although both CPEB1 and CPEB4 were able to recruit the polyadenylation machinery to the same mRNAs, they were not functionally exchangeable.

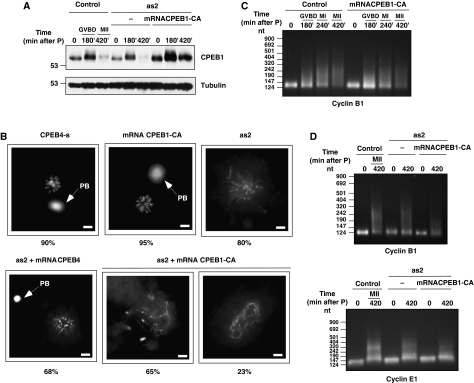

Figure 5.

A stable CPEB1 mutant cannot replace CPEB4 in the second meiotic division. Xenopus oocytes were injected with CPEB4 sense (control) or anti-sense (as2) oligonucleotides. After 16 h, oocytes were microinjected with mRNAs encoding either CPEB4 or CPEB1-CA and incubated with progesterone. (A) Oocytes were collected at the indicated times and analysed for CPEB1 levels by western blot using anti-CPEB1 and anti-tubulin antibodies (1.5 oocyte equivalents were loaded per lane) (B) Oocytes were collected 4 h after control oocytes display 100% GVBD and treated as Figure 3B. (C, D) Total RNA from oocytes collected at the indicated times was extracted and polyadenylation status of cyclin B1and cyclin E mRNAs was measured by RNA-ligation-coupled RT–PCR.

As both CPEBs were able to recruit the poly(A) polymerase to the same CPE-regulated mRNAs, we aimed to address their functional specificity by focusing in their posttranslational regulation. CPEB1 is activated by the Aurora A kinase phosphorylation of serine 174 (Mendez et al, 2000a). However, CPEB4 lacks any consensus sequence for Aurora A kinase, even if it is phosphorylated in response to progesterone (Supplementary Figure S5). Thus, the difference between CPEB1 and CPEB4 might reside in the signal transduction pathways that are active at different meiotic phases and that differentially target both CPEBs, rather than in the intrinsic differences between both proteins. Indeed, Aurora A follows a biphasic pattern of activation and has to be inactivated during interkinesis to allow for MI–MII transition (Ma et al, 2003; Pascreau et al, 2008). Moreover, PPI, which dephosphorylates Ser 174 (Tay et al, 2003), is synthesized during the first wave of cytoplasmic polyadenylation (Belloc and Mendez, 2008). Therefore, we hypothesized that, if CPEB1 would remain present after MI, it may result inactivated during interkinesis and reassemble the repression/deadenylation complexes. Thus, overexpression of non-degradable CPEB1, rather than being able to rescue for the lack of CPEB4, will cause the deadenylation of CPE-containing mRNAs polyadenylated in PI and early MI. This hypothesis would explain not only the lack of rescue, but also the observed deadenylation of cyclin B1 mRNA in oocytes depleted of CPEB4 and injected with the CPEB1 stable mutant.

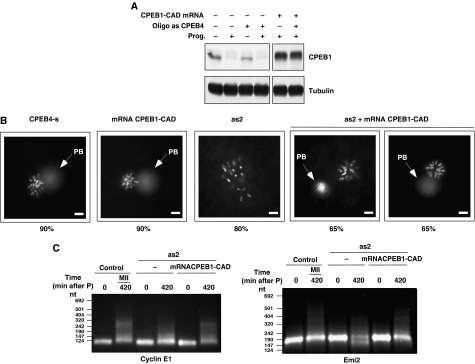

To test this hypothesis, we generated an additional CPEB1 mutant (CPEB1-CAD) that has the cdc2-phosphorylated residues substituted by Alanines (to generate a stable variant), and the regulatory Ser174 mutated to Aspartic acid (to generate a phosphomimetic constitutively activated form of the protein). CPEB1-CAD expression (Figure 6A) was indeed able to compensate for the depletion of CPEB4, both by rescuing the proper chromosome segregation (Figure 6B) and restoring the third wave of cytoplasmic polyadenylation for the ‘late–late' cyclin E and emi2 mRNAs (Figure 6C). This result argues that CPEB1 and CPEB4 perform the same function in the translational control of maternal mRNAs, but different signal transduction pathways regulate the two CPEBs. Thus, although CPEB1 is able to support cytoplasmic polyadenylation when Aurora A kinase is active, in PI and early MI, it will be inactivated in the MI–AI transition. CPEB1 inactivation would, in turn, lead to the deadenylation of mRNAs (such as cyclin B1, Figure 5D) that are required to maintain the intermediate levels of MPF activity required to block DNA replication during interkinesis, and latter to fully reactivate MPF for MII entry. To overcome this problem, CPEB1 is degraded and replaced by another CPEB that is not regulated by Aurora A. The correct coordination of this replacement is ensured by the translational control of CPEB4 by CPEB1 before the degradation of the latest by the APC.

Figure 6.

A stable and constitutively active CPEB1 mutant can compensate for CPEB4 depletion in the second meiotic division. Xenopus oocytes were injected with CPEB4 sense (control) or anti-sense (as2) oligonucleotides. After 16 h, oocytes were microinjected with mRNA encoding a stable and constitutively active CPEB1 mutant (CPEB1-CAD) and incubated with progesterone. Oocytes were collected 4 h after control oocytes display 100% GVBD and analysed for CPEB1 levels by western blot using anti-CPEB1 and anti-tubulin antibodies (one oocyte equivalents were loaded per lane) (A) or fixed, stained with Hoechst and examined under epifluorescence microscope as in Figure 3B (B). (C) Total RNA from oocytes collected at the indicated times was extracted and polyadenylation status of cyclin E and Emi2 mRNAs was measured by RNA-ligation-coupled RT–PCR.

Discussion

Progression through the two meiotic divisions requires the sequential activation of maternal mRNAs encoding factors that drive cell-cycle phase transitions. This sequential activation is achieved by a combination of successive phosphorylation events in CPEB1 with a combinatorial arrangement of CPEs and AREs in the CPEB-regulated mRNAs. First, Aurora A kinase activates CPEB1 and triggers the ‘early' wave of cytoplasmic polyadenylation required for the PI–MI transition (Mendez et al, 2000a, 2000b; Pique et al, 2008; although see Keady et al, 2007). Then, in MI, Cdc2- and Plx1-mediated phosphorylations target CPEB1 for SCF(β-TrCP)-dependent degradation, thus lowering CPEB1 levels. Low CPEB1 levels are, in turn, necessary to trigger the second or ‘late' wave of polyadenylation required for MI–MII transition (Reverte et al, 2001; Mendez et al, 2002; Setoyama et al, 2007; Pique et al, 2008). These ‘late' mRNAs, such as cyclin B1 mRNA, contain at least two CPEs being the most distal one overlapping with the Hex, which becomes accessible to CPSF only on CPEB1 degradation (Mendez et al, 2002). The drawback of the degradation of CPEB1 in MI is that the remaining levels of this factor are then very low for interkinesis and for the second meiotic division, when the third or ‘late–late' wave of cytoplasmic polyadenylation is required to mediate the MII arrest by CSF (Belloc and Mendez, 2008). During interkinesis, APC activation is combined with increased synthesis of cyclins B1 and B4 (Hochegger et al, 2001; Pique et al, 2008), resulting in only a partial inactivation of MPF at anaphase I and preventing entry into S-phase (Iwabuchi et al, 2000). Full reactivation of MPF for MII requires re-accumulation of high levels of cyclins B, as well as the inactivation of APC by newly synthesized Emi2 and other components of the CSF, such as cyclin E or high levels of Mos (Schmidt et al, 2006; Belloc and Mendez, 2008).

The recent discovery of other members of the CPEB family of proteins, together with the description of an autoregulatory loop of the CPEB-ortholog Orb (Tan et al, 2001), pointed us to explore the possibility that CPEB1 could activate the translation of other members of the CPEB family to compensate for its reduced levels after MI. All CPEB-like proteins have a similar structure with most of the carboxy-terminal regions composed of two RNA recognition motifs and two zinc fingers. On the other hand, the regulatory amino-terminal domains of the CPEB proteins show a small degree of identity. The most extensively studied member of the family, CPEB1, has dual functions as a translational repressor and activator, whereas CPEB3 and CPEB2 seem to act only as translational repressors (Schmitt and Nebreda, 2002; Huang et al, 2006; Hagele et al, 2009; Novoa et al, 2010).

In this study, we found that CPEB4 is encoded by a maternal mRNA activated by CPEB1 during the ‘early' wave of cytoplasmic polyadenylation, being then partially inactivated by C3H-4-mediated deadenylation. This translational regulation leads to the gradual accumulation of CPEB4 from MI to reach maximal levels in the MII arrest. In turn, CPEB4 is required for the MI–MII transition and recruits GLD2 to ‘late' and ‘late–late' CPE-regulated mRNAs, which are activated by cytoplasmic polyadenylation during interkinesis and encode proteins required for the second meiotic division and to prevent DNA replication after MI, such as XKid, TPX2, cyclin E, emi2, cyclins B1/B4 (Hochegger et al, 2001; Belloc and Mendez, 2008; Eliscovich et al, 2008; Pique et al, 2008). It is noteworthy that the phenotype generated by depleting CPEB4 is very similar to the one caused by XKid mRNA depletion (Perez et al, 2002). Altogether, our work shows that CPEB4 replaces CPEB1 for the second meiotic division by regulating CPE-containing mRNAs. However, reflecting their relative levels of protein, CPEB1 mediates cytoplasmic polyadenylation in the first meiotic division and CPEB4 in the second. This explains why inhibition of CPEB1 prevents meiotic resumption from the PI arrest, whereas CPEB4 depletion blocks meiotic progression between the first and the second metaphases.

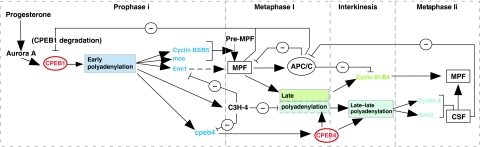

But, why are two different CPEBs required for completion of meiosis? Although CPEB1 and 4 recognize the same CPE-regulated mRNAs and recruit GLD2, they are not interchangeable as shown by the fact that stabilized CPEB1 cannot replace CPEB4 for the transition from MI to MII nor for the polyadenylation of the ‘late–late' mRNA encoding cyclin E. This may reflect the differential regulation of both proteins. Besides the fact that CPEB1 contains a PEST box that mediates its degradation on phosphorylation by Cdc2 and Plx1, CPEB1 is the only member of the family that contains Aurora A kinase phosphorylation sites (Mendez and Richter, 2001). Thus, although CPEB1 is activated by Aurora A kinase in PI and MI (Mendez et al, 2000a), it will be inactivated during interkinesis due to the inhibition of Aurora A kinase (Ma et al, 2003; Pascreau et al, 2008) and the increased levels of PPI, which dephosphorylates CPEB1 Ser 174 (Tay et al, 2003; Belloc and Mendez, 2008). In turn, if inactive CPEB1 is present during interkinesis, this would result in the deadenylation of the previously polyadenylated mRNAs (‘early' and ‘late') and the lack of polyadenylation of the ‘late–late' mRNAs (Figure 5D). Accordingly, the inhibition of Aurora A kinase can be rescued by overexpressing a constitutively active, and non-degradable, mutant of CPEB1 (Figure 6). Therefore, to overcome the need of inhibiting Aurora A kinase to exit MI, CPEB1 must be replaced by CPEB4, which is not regulated by this kinase, but rather by another one that would remain active during interkinesis. CPEB4 contains putative recognition sites for PKA, CaMKII and S6 kinase (Theis et al, 2003), suggesting differential posttranslational regulation of both factors during meiotic progression. Accordingly, overexpressed CPEB4 shows mobility changes in response to progesterone without any effect on its stability (Supplementary Figure S5). These observations suggest that CPEB4 is not constitutively active, but, rather, it has to be posttranslationally modified to become active and, not having a consensus Aurora A kinase phosphorylation site, it will most likely be activated by a different phosphorylation, taking place at later meiotic phases. Although neither the phosphorylation sites for CPEB4 in meiosis nor the kinase responsible are known, mammalian CPEB4 is phosphorylated in mitotic cells in multiple proline-directed sites (http://www.phosphosite.org), of unknown regulatory function. This observation is consistent with the timing of CPEB4 phosphorylation (Supplementary Figure S5) after GVBD, when a number of proline-directed kinases are activated (Mapk, Plk1, Cdc2, etc.). Taken these findings together, we propose a meiotic molecular circuit (Figure 7) where cytoplasmic polyadenylation is initiated by Aurora A kinase phosphorylation of CPEB1, which triggers the ‘early' wave of cytoplasmic polyadenylation required to enter the first meiotic metaphase. In MI, Cdc2 and PlK1 activate the degradation of CPEB1, which is necessary, not only to allow the polyadenylation of ‘late' mRNAs in MI, but also to prevent deadenylation of these ‘early' and ‘late' mRNAs in interkinesis (Figure 5D) when Aurora A kinase is inhibited (Ma et al, 2003; Pascreau et al, 2008). Concomitantly, CPEB1 activates the synthesis of CPEB4, which supports the third wave of ‘late–late' polyadenylation during interkinesis and in MII. Thus, CPEB1 and CPEB4 are functionally exchangeable, but regulated by different signal transduction pathways to ensure that they stay in their active forms at the appropriate meiotic phases and that the polyadenylation machinery is active during the whole meiotic progression. The coordination of events required for correct meiotic phase transitions, and the self-sustainability of the three waves of cytoplasmic polyadenylation once the initial stimulation by progesterone takes place, is accomplished by the translational control of CPEB4 by CPEB1 before the degradation of the latest by the APC.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram showing the sequential activities of CPEB1 and CPEB4 mediating the three waves of polyadenylation driving meiotic progression.

Materials and methods

Xenopus oocytes preparation

Stage VI oocytes were obtained from Xenopus females and induced to mature with progesterone (10 mM, Sigma), as described earlier (de Moor and Richter, 1999).

Plasmid constructs

CPEB4 (GQ338835) cDNA was cloned by RT–PCR from total RNA of stage VI oocytes using primers 5′-CGGGATCCATGGGGGATTACGGGTTTGGAG-3′ and 5′-TCCCCCGGGTCAGTTCCAGCGGAATGAAATATGC-3′, digested with Sma and BamHI and cloned in pGEX or pET30a expression vectors. CPEB4 3′ UTR was amplified by RT–PCR from total RNA of stage VI oocytes using primers 5′-GAAGATCTTGAGCAACCCATGGCTTAGC-3′ and 5′-TGCTTAATGCTTTTAATAGGCAACTGC-3′, digested with Bgl-II and cloned in the pLucassette downstream the Firefly luciferase ORF.

Hex mutants of CPEB4 were obtained by PCR from the original plasmid with T3 standard primer as sense oligonucleotide and the following anti-sense oligonucleotides: H2as: 5′-TGCTTAATGCTTTTAATAGGCAACTGCTGACTTTTCCTTTTCAATAAAG-3′; H3as: 5′-TGCTTAATGCTTTCCATTGGCAACTGCTGACTTTTTATTTTCAATAAAG-3′; H23as: 5′-TGCTTAATGCTTTCCATAGGCAACTGCTGACTTTTCCTTTTCAATAAAG-3′.

CPE mutants were obtained with QuikChange Multi Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) following the manufacture's instructions. The oligonucleotides used were:

C12: 5′-TATTATTTTTTTTGGTATATAATTTGGTCGGAGAGCAAAGC-3′;

C3: 5′-CGAGAAATAGAGTATTTTTTTTTGGTTAAATTATTG-3′;

C4: 5′- GGTTTGTTGAACAGATTTTTTTTTGGGATATATATATATA-3′;

C5: 5′-GTTTGTATTTGGCCAGACTTTATTGAAAATAAAAAG-3′.

Translational control and cytoplasmic polyadenylation by 3′ UTR

Translation and polyadenylation of reporter mRNAs were assayed as described earlier (Pique et al, 2006). Briefly, oocytes were injected with 0.0125 fmols of reporter mRNA (Firefly luciferase containing the indicated 3′ UTR or control 3′ UTR) together with 0.0125 fmols Renilla luciferase RNA as a normalizing RNA. Luciferase activity was measured using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assays System (Promega), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Western blot analysis

Oocyte lysates, prepared by homogenizing 6–10 oocytes in histone H1 kinase buffer containing 0.5% NP-40 and centrifuged at 12 000 g for 10 min, were resolved by 8% SDS–PAGE. Equivalents of 1–2 oocytes were loaded onto each lane. Antibodies used were rabbit anti-serum affinity purified against CPEB4, rabbit anti-serum against CPEB1, monoclonal antibody against α-tubulin (DM1A, Sigma).

RNA-ligation-coupled RT–PCR

Total oocyte RNA was isolated from 8–10 oocytes by Ultraspec RNA Isolation System (Biotecx Laboratories, Inc.), following the manufacturer's instructions. Then, RNA-ligation-coupled RT–PCR technique was performed as described earlier (Charlesworth et al, 2002) with some modifications. Briefly, 5 μg of oocyte total RNA was ligated to 0.5 μg of a 3′-amino-modified DNA anchor primer (5′-P-GGTCACCTCTGATCTGGAAGCGAC-NH2-3′) in a 10 μl reaction using T4 RNA ligase (New England Biolabs), according to the manufacturer's directions. RNA-ligation reaction was used in a 50 μl reverse transcription reaction using RevertAid M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase (Fermentas) and 0.5 μg of an oligo anti-sense to the anchor primer plus four thymidine residues on its 3′-end (5′- GTCGCTTCCAGATCAGAGGTGACCTTTTT-3′). The resulting reaction product was digested with 2 μg RNAse A (Fermentas) and 2 μl of this cDNA preparation were used as a template for gene-specific PCR reaction. The specific oligos were: 5′-GCATCTATTTATTGTTTGTATTTTTCC-3′ for CPEB4, 5′-GTCAAGGACATTTATGCTTACC-3′ for cyclin B1, 5′-GTACGCCACATGAGTACAAGC-3′ for cyclin E and 5′-GTATATACATTCATTTGTTCAATGTTGCC-3′ for Emi2. DNA products from the PCR reaction were analysed in a 2% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Cytoplasmic polyadenylation by 3′ UTR

Total RNA was isolated from 6 to 8 oocytes injected with radiolabelled 3′ UTR by Ultraspec Isolation System (Biotecx Laboratories, Inc.). RNAs were analysed by 6% polyacrimaldide/8 M urea gel electrophoresis followed by autoradiography, as described earlier in Pique et al (2006).

Histone H1 kinase assay (Cdc2 assay)

Oocyte lysates prepared by homogenizing three oocytes in histone H1 kinase buffer (80 mM Na β-glycerophosphate, 20 mM EGTA, 15 mM MgCl2, 50 mM NaVaO4) and centrifuged at 12 000 g for 10 min at 4°C were incubated with histone H1 (Sigma) and [γ-32P]ATP (3000 Ci/mmol) as described earlier (Mendez et al, 2000a). The phosphorylation reaction was analysed by 12% SDS–PAGE gel and autoradiography.

Chromosomes and polar body observation

Oocytes fixed for at least 1 h in 100% methanol were incubated overnight in the presence of 20 μg/l Hoechst dye. Chromosomes and polar body of stained oocytes were viewed from animal pole under UV epifluorescence microscope (Leica DMR microscope, × 63 magnification, Leica DFC300FX camera, Leica IM1000 Image Manager).

Anti-sense oligonucleotide and rescue experiment

To ablate the expression of CPEB4, oligonucleotides targeting either 5′ UTR or the 3′ UTR were designed; one complementary sequence was used as a control. In each oocyte, 99 ng of oligonucleotide was injected. After overnight (16 h) incubation at 18°C, progesterone was added as described. For rescue experiment, 0.06 pmol of in vitro transcribed RNA coding for the ORF of CPEB4, 0.02 pmol of the non-degradable CPEB1 mutant (CPEB1-CA) and 0.02 pmol of the non-degradable constitutively active CPEB1 mutant (CPEB1-CAD) were injected 1–2 h before progesterone incubation. Oligonucleotides used were: 19AS: 5′-GAGGAAATATATCTGGGTGAAG-3′; 20AS: 5′-GCAATGGGTTGCTCAGTTCCA-3′; 23S: 5′-CTTTGCAAGCATCCAAATAAG-3′.

Analysis of DNA synthesis

Oocytes were injected with 0.4 μCi [α-32P]dCTP and treated subsequently with progesterone to induce maturation. Mature oocytes were subjected to DNA extraction, and samples with equal number of total counts (0.5 × 106 c.p.m.) were analysed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and autoradiography, as described earlier (Newport and Kirschner, 1984).

Immunoprecipitation

CPEB4 antibody raised in rabbits against the CPEB4 71–85 peptide (DEILGSEKSKSQQQQ), and CPEB1 antibody were incubated with protein-A sepharose during 2 h at room temperature on wheel, washed with PBS and resuspended in sodium borat pH 9.0. 20 mM dimethyl pimelimidate·2HCl (DMP) was added and incubated for 30 min at room temperature on wheel. Reaction was stopped with two 5 min washes at room temperature with 0.05 M glycine, and two extra washes with PBS. Fresh oocyte lysates from stage VI and MII (25 oocytes per condition) were added to the cross-linked antibody beads and incubated for 2 h at 4°C on wheel. Immunoprecipitates were washed three times in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl) and eluted with sample buffer (200 mM Tris–HCl pH 6,8, 40% glycerol, 8% SDS, 20 mM DTT), separated by SDS–PAGE and analysed by western blotting.

IP-qRT–PCR

Immunoprecipitations followed by RT were performed as described (Aoki et al, 2003) with fresh stage VI and MII oocyte lysates (25 oocytes per condition). CPEB4 antibody raised in rabbits against the CPEB4 71–85 peptide (DEILGSEKSKSQQQQ), and CPEB1 antibody. The protein-bound RNAs were purified by proteinase K digestion followed by phenol–chloroform extraction. The RNA extracted was used for the retrotranscription, performed with the 3′ Race primer (TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCGGATCCTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTVN), with the MLuV reverse transcriptase from Fermentas following the manufacturer's instructions. Quantification of RNA immunoprecipitation was performed by real-time PCR using Roche Lightcycler (Roche). The fold enrichment of target sequences in the immunoprecipitated (IP) compared with input fractions was calculated using the comparative Ct (the number of cycles required to reach a threshold concentration) method with the equation 2Ct(IP)−Ct(Ref). Then, these values were normalized considering 1 for prophase I the value obtained for cyclin B1 immunoprecipitated with CPEB1, and considering 1 for MII the value obtained for Emi2 immunoprecipitated with CPEB4. Primers sequences are available on request.

Immunoprecipitations of cyclin B1 injected mRNA were performed as described earlier in stage VI and MII fresh oocytes injected with 0.02 pmol of cyclin B1 WT or a mutant lacking CPE elements.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mercedes Fernández, the members of the Méndez laboratory, Fátima Gebauer, Juan Valcarcel and Josep Vilardell for helpful advice and critical reading of the paper. This work was supported by grants from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, Fundación ‘La Caixa' and Fundació ‘Marató de TV3'. RM is a recipient of a contract from the ‘i3 program' (MCI). AI is recipient of a fellowship from the DURSI (Generalitat de Catalunya) i dels Fons Social Europeu.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Aoki K, Matsumoto K, Tsujimoto M (2003) Xenopus cold-inducible RNA-binding protein 2 interacts with ElrA, the Xenopus homolog of HuR, and inhibits deadenylation of specific mRNAs. J Biol Chem 278: 48491–48497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne S, Daniel DL Jr, Wickens M (1997) A dependent pathway of cytoplasmic polyadenylation reactions linked to cell cycle control by c-mos and CDK1 activation. Mol Biol Cell 8: 1633–1648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belloc E, Mendez R (2008) A deadenylation negative feedback mechanism governs meiotic metaphase arrest. Nature 452: 1017–1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belloc E, Pique M, Mendez R (2008) Sequential waves of polyadenylation and deadenylation define a translation circuit that drives meiotic progression. Biochem Soc Trans 36(Part 4): 665–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth A, Ridge JA, King LA, MacNicol MC, MacNicol AM (2002) A novel regulatory element determines the timing of Mos mRNA translation during Xenopus oocyte maturation. EMBO J 21: 2798–2806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Moor CH, Richter JD (1997) The Mos pathway regulates cytoplasmic polyadenylation in Xenopus oocytes. Mol Cell Biol 17: 6419–6426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Moor CH, Richter JD (1999) Cytoplasmic polyadenylation elements mediate masking and unmasking of cyclin B1 mRNA. EMBO J 18: 2294–2303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliscovich C, Peset I, Vernos I, Mendez R (2008) Spindle-localized CPE-mediated translation controls meiotic chromosome segregation. Nat Cell Biol 10: 858–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuno N, Nishizawa M, Okazaki K, Tanaka H, Iwashita J, Nakajo N, Ogawa Y, Sagata N (1994) Suppression of DNA replication via Mos function during meiotic divisions in Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J 13: 2399–2410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagele S, Kuhn U, Boning M, Katschinski DM (2009) Cytoplasmic polyadenylation-element-binding protein (CPEB)1 and 2 bind to the HIF-1alpha mRNA 3′-UTR and modulate HIF-1alpha protein expression. Biochem J 417: 235–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hake LE, Richter JD (1994) CPEB is a specificity factor that mediates cytoplasmic polyadenylation during Xenopus oocyte maturation. Cell 79: 617–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochegger H, Klotzbucher A, Kirk J, Howell M, le Guellec K, Fletcher K, Duncan T, Sohail M, Hunt T (2001) New B-type cyclin synthesis is required between meiosis I and II during Xenopus oocyte maturation. Development (Cambridge, England) 128: 3795–3807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YS, Kan MC, Lin CL, Richter JD (2006) CPEB3 and CPEB4 in neurons: analysis of RNA-binding specificity and translational control of AMPA receptor GluR2 mRNA. EMBO J 25: 4865–4876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwabuchi M, Ohsumi K, Yamamoto TM, Sawada W, Kishimoto T (2000) Residual Cdc2 activity remaining at meiosis I exit is essential for meiotic M-M transition in Xenopus oocyte extracts. EMBO J 19: 4513–4523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keady BT, Kuo P, Martinez SE, Yuan L, Hake LE (2007) MAPK interacts with XGef and is required for CPEB activation during meiosis in Xenopus oocytes. J Cell Sci 120 (Part 6): 1093–1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara Y, Tokuriki M, Myojin R, Hori T, Kuroiwa A, Matsuda Y, Sakurai T, Kimura M, Hecht NB, Uesugi S (2003) CPEB2, a novel putative translational regulator in mouse haploid germ cells. Biol Reprod 69: 261–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, Cummings C, Liu XJ (2003) Biphasic activation of Aurora-A kinase during the meiosis I- meiosis II transition in Xenopus oocytes. Mol Cell Biol 23: 1703–1716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez R, Barnard D, Richter JD (2002) Differential mRNA translation and meiotic progression require Cdc2-mediated CPEB destruction. EMBO J 21: 1833–1844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez R, Hake LE, Andresson T, Littlepage LE, Ruderman JV, Richter JD (2000a) Phosphorylation of CPE binding factor by Eg2 regulates translation of c-mos mRNA. Nature 404: 302–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez R, Murthy KG, Ryan K, Manley JL, Richter JD (2000b) Phosphorylation of CPEB by Eg2 mediates the recruitment of CPSF into an active cytoplasmic polyadenylation complex. Mol Cell 6: 1253–1259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez R, Richter JD (2001) Translational control by CPEB: a means to the end. Nat Rev 2: 521–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newport J, Kirschner M (1982) A major developmental transition in early Xenopus embryos: II. Control of the onset of transcription. Cell 30: 687–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newport JW, Kirschner MW (1984) Regulation of the cell cycle during early Xenopus development. Cell 37: 731–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novoa I, Gallego J, Ferreira PG, Mendez R (2010) Mitotic cell-cycle progression is regulated by CPEB1 and CPEB4-dependent translational control. Nat Cell Biol 12: 447–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascreau G, Delcros JG, Morin N, Prigent C, Arlot-Bonnemains Y (2008) Aurora-A kinase Ser349 phosphorylation is required during Xenopus laevis oocyte maturation. Dev Biol 317: 523–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez LH, Antonio C, Flament S, Vernos I, Nebreda AR (2002) Xkid chromokinesin is required for the meiosis I to meiosis II transition in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Nat Cell Biol 4: 737–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pique M, Lopez JM, Foissac S, Guigo R, Mendez R (2008) A combinatorial code for CPE-mediated translational control. Cell 132: 434–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pique M, Lopez JM, Mendez R (2006) Cytoplasmic mRNA polyadenylation and translation assays. Methods Mol Biol (Clifton, NJ) 322: 183–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radford HE, Meijer HA, de Moor CH (2008) Translational control by cytoplasmic polyadenylation in Xenopus oocytes. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta 1779: 217–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reverte CG, Ahearn MD, Hake LE (2001) CPEB degradation during Xenopus oocyte maturation requires a PEST domain and the 26S proteasome. Dev Biol 231: 447–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter JD (2007) CPEB: a life in translation. Trends Biochem Sci 32: 279–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt A, Rauh NR, Nigg EA, Mayer TU (2006) Cytostatic factor: an activity that puts the cell cycle on hold. J Cell Sci 119 (Part 7): 1213–1218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt A, Nebreda AR (2002) Signalling pathways in oocyte meiotic maturation. J Cell Sci 115(Part 12): 2457–2459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setoyama D, Yamashita M, Sagata N (2007) Mechanism of degradation of CPEB during Xenopus oocyte maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 18001–18006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stebbins-Boaz B, Hake LE, Richter JD (1996) CPEB controls the cytoplasmic polyadenylation of cyclin, Cdk2 and c-mos mRNAs and is necessary for oocyte maturation in Xenopus. EMBO J 15: 2582–2592 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan L, Chang JS, Costa A, Schedl P (2001) An autoregulatory feedback loop directs the localized expression of the Drosophila CPEB protein Orb in the developing oocyte. Development (Cambridge, England) 128: 1159–1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay J, Hodgman R, Sarkissian M, Richter JD (2003) Regulated CPEB phosphorylation during meiotic progression suggests a mechanism for temporal control of maternal mRNA translation. Genes Dev 17: 1457–1462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theis M, Si K, Kandel ER (2003) Two previously undescribed members of the mouse CPEB family of genes and their inducible expression in the principal cell layers of the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 9602–9607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou BB, Li H, Yuan J, Kirschner MW (1998) Caspase-dependent activation of cyclin-dependent kinases during Fas-induced apoptosis in Jurkat cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 6785–6790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.