Abstract

Myoglobin is one of the premature identifying cardiac markers, whose concentration increases from 90 pg∕ml or less to over 250 ng∕ml in the blood serum of human beings after minor heart attack. Separation, detection, and quantification of myoglobin play a vital role in revealing the cardiac arrest in advance, which is the challenging part of ongoing research. In the present work, one of the electrokinetic approaches, i.e., dielectrophoresis (DEP), is chosen to separate the myoglobin. A mathematical model is developed for simulating dielectrophoretic behavior of a myoglobin molecule in a microchannel to provide a theoretical basis for the above application. This model is based on the introduction of a dielectrophoretic force and a dielectric myoglobin model. A dielectric myoglobin model is developed by approximating the shape of the myoglobin molecule as sphere, oblate, and prolate spheroids. A generalized theoretical expression for the dielectrophoretic force acting on respective shapes of the molecule is derived. The microchannel considered for analysis has an array of parallel rectangular electrodes at the bottom surface. The potential and electric field distributions are calculated using Green’s theorem method and finite element method. These results also compared to the Fourier series method, closed form solutions by Morgan et al. [J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 34, 1553 (2001)] and Chang et al. [J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 36, 3073 (2003)]. It is observed that both Green’s theorem based analytical solution and finite element based numerical solution for proposed model are closely matched for electric field and square electric field gradients. The crossover frequency is obtained as 40 MHz for given properties of myoglobin and for all approximated shapes of myoglobin molecule. The effect of conductivity of medium and myoglobin on the crossover frequency is also demonstrated. Further, the effect of hydration layer on the crossover frequency of myoglobin molecules is also presented. Both positive and negative DEP effects on myoglobin molecules are obtained by switching the frequency of applied electric field. The effect of different shapes of myoglobin on DEP force is studied and no significant effect on DEP force is observed. Finally, repulsion of myoglobin molecules from the electrode plane at 1 KHz frequency and 10 V applied voltage is observed. These results provide the ability of applying DEP force for manipulating nanosized biomolecules such as myoglobin.

INTRODUCTION

Heart attack, also known as myocardial infarction or acute myocardial infarction (AMI), is the death of heart muscles. This occurs when blood supply to part of the heart is blocked.1, 2 Early assessment of heart attacks has always posed a problem to researchers. It has been found that the concentration of certain proteins and∕or enzymes increases in the blood serum after infarction.1, 3 Hence, these proteins or enzymes are considered as cardiac markers. The cardiac proteins, such as myoglobin, troponin I, troponin T, CK-MB, fatty acid-binding protein (also known as H-FABP), and isoenzymes, appear in the blood serum of human beings after AMI.2, 4 Myoglobin is one of the premature identifying cardiac protein markers whose concentration level increases from 90 pg∕ml or less to over 250 ng∕ml in the blood serum within the first 2–8 h after heart muscles start dying.1, 3 Separation, detection, and quantification of such cardiac markers from blood serum can play an important role in the early detection of heart attack.

Several separation methods, such as SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), one dimensional gel electrophoresis, isoelectrofocusing, two dimensional (2D) gel electrophoresis, anion-exchange chromatography, gel filtration chromatography, affinity chromatography, and multidimensional chromatography, are well known established methods for myoglobin separation.1, 3, 5, 6, 7 Most of these methods separate the myoglobin from tissue or blood based on molecular weight or size or ionic charge on the myoglobin molecules.5, 6, 7 The separated myoglobin can be identified or detected by one of the following methods, such as western bolting,6 Edman degradation, and mass spectrometry.1, 3 Mass spectrometry is also used to determine the concentration of myoglobin.1, 3

Qiaojia et al.8 proposed a bedside assay by sandwich dot-immunogold filtration for the diagnosis of AMI. This assay gives the qualitative measurements for increased human serum myoglobin. Radioimmunoassay1 and enzyme linked immunosorbent assay4, 9, 10 techniques are also used for qualitative determination of myoglobin concentration in blood serum or plasma. O’Regan et al.11 developed a disposable immunosensor for the rapid detection of myoglobin in whole blood. The sensor is based on one step indirect sandwich assay. This indirect approach offers a wider working ranges for detection of concentration levels of myoglobin. Wang et al.2 demonstrated the carboxylated magnetic microbead-assisted fluoroimmunoassay for the analysis of the early AMI protein markers, myoglobin, and H-FABP. They detected myoglobin and H-FABP in the ranges of 25–250 and 1–25 ng∕ml, respectively.

Commercial immunoassay instruments are also available for qualitative or quantitative measurement of myoglobin concentration in blood serum or plasma. They are Access (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA), Triage cardiac panel (Biosite Diagnostics, San Diego, CA), Dade Behring BN II Nephelometer, Dade Behring OPUS Immunoassay, Dimension RxL and Stratus CS (Dade Behring, Deerfield, IL), AxSYM (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL), immunometric VIDAS MYO (BioMerieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France), Hitachi 917, Hitachi 911, Elecsys 2010 and Integra 400 (Roche Diagnostics, Penzberg, Germany), Olympus AU640 multiparameter analyzer (Olympus Optical Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), Immulite turbo Myoglobin LSKMY (DPC France, La Garenne, Colombes, France), and AQT90 FLEX (Innotrac Diagnostics, Turku, Finland).12, 13, 14, 15

Recently, a portable rapid myoglobin test cassette from Boston Biotechnology Co., Ltd, Fujian, China is released in the market for qualitative assessment of human myoglobin in human serum, plasma, and whole blood. The test cassette is an immunochromatography based one step in vitro test. It detects the myoglobin in blood serum or plasma, if the levels are 100 ng∕ml or higher. However, these instruments∕methods provide different values of myoglobin levels.3 In addition, these equipments are expensive and take hours for detection.1, 3 Therefore, developing a cost-effective, accurate, reliable, and standard technique for separating, detecting, and quantifying the myoglobin from a whole blood sample will be a major development in the early assessment of cardiac arrest. However, there is a limited understanding of microscale behavior and transport of such biomolecule in a microfluidic device. The current theories are very limited, which cannot offer strong support for myoglobin separation and detection. Therefore, this paper focuses on the theoretical investigation of manipulation of myoglobin molecules in a microfluidic device with the help of dielectrophoresis (DEP) principle.

DEP is a manipulation of dielectric or neutral particles because of polarization effects under nonuniform electric fields.16 The net force created with DEP generates momentum in the particles. Particle movement toward regions of high electric field intensities is called positive DEP and occurs when the interior of the particle is more permissive to the field. The opposite effect is the movement toward lower electric field intensities called negative DEP, when the exterior is more permissive.16, 17, 18 The frequency at which the DEP effect changes from positive DEP to negative DEP or negative DEP to positive DEP is called crossover frequency.16, 17 The DEP force depends on both the gradient of the electric field and electrical properties, such as permittivity and conductivity of the particle and medium. It is important to note that the force due to DEP is based on the gradient of electric field and not the absolute value at any point. Analysis of movement of the particles in a nonuniform electric field needs accurate knowledge of the electric field distribution in the system. Different electrode geometries and arrangements are used to produce nonuniform electric field. They are polynomial electrodes, castellated electrodes, interdigited electrodes, and array of electrodes. Each arrangement has its own advantages and disadvantages.

DEP has significant advantages in the areas of biomedical, pharmaceutical, drug delivery, and point-of-care systems.16, 17, 18, 19 It helps in separating, trapping, concentrating, mixing, and sorting of particles with sizes varying from a few microns to nanometers, such as cells, bacteria, viruses, DNA, and proteins.16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42 In the past few decades, application of DEP principle for manipulating biomolecules has increased because of improvements in micro-∕nanofabrication facilities.33 Since DEP is based on the differences in dielectric properties of particles and suspended medium, there is no need of special sample preparation or chemical∕biological modifications of the sample.34 Availability of predefined properties of most of the important proteins has increased the use of DEP technique.18

Washizu et al.35 carried the first demonstration on dielectrophoretic manipulation of proteins. They used parallel array of corrugated microelectrodes of 1 μm width and minimum gaps of 4, 15, and 55 μm between the electrodes for creating nonuniform electric fields. The experimental results showed that the trapping of proteins, such as avidin (68 kDa), concanavalin (52 kDa), chymotrypsinogen (25 kDa), and ribonuclease A (13.7 kDa), occurred at the edges of the electrodes under DEP effects. The results also suggested the strong relation between the molecular weight and dielectrophoretic response of proteins. Their work only showed the positive DEP of proteins. Later, Bakewell et al.36 and Hughes and Morgan37 showed the positive and negative DEPs for proteins. They used polynomial electrodes with a center gap of 2 μm for manipulating the avidin protein molecules. Zheng et al.38, 39 reported manipulating bovine serum albumin (BSA) protein under positive DEP effects. They used the quadrupole gold microelectrodes with center gaps of 5, 10, 20, and 50 μm for trapping the BSA proteins. They presented the mathematical calculation of the Clausius–Mossotti (CM) factor for BSA protein. They modeled BSA protein as a sphere with 5 nm diameters and predicted the crossover frequency of 100 MHz for the protein solution with conductivity of 1 mS∕m. Clarke et al.40 demonstrated the dielectrophoretic concentration of proteins with nanopipette technique. Existing literature suggests that theoretical investigations are needed to support the experimental study. Therefore, the dielectrophoretic behavior of one of the cardiac markers, i.e., myoglobin, is investigated in this paper.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Sec. 2, DEP theory is explained briefly. Dielectric myoglobin model is introduced in Sec. 3. The mathematical model for simulating the dielectrophoretic manipulation of myoglobin molecules is developed in Sec. 4. Solution methodologies are provided as well in Sec. 4. In Sec. 5, various results to decide the dielectrophoretic behavior of the myoglobin molecules are analyzed and discussed. Comparison studies are also conducted to evaluate the proposed model.

BRIEF INTRODUCTION OF DEP THEORY

When a neutral particle placed in a nonuniform electric field, it experiences a net force due to induced dipole moment. This net force is known as DEP force, which depends on the volume of particle, electrical properties of the medium and particle, and magnitude and frequency of the applied ac electric field.16 AC electric fields are used to avoid any membrane charging or hydrolysis effect on biomolecules.19 The advantage of using microelectrodes is that large field gradient can be produced with lower voltages.19, 33

The time averaged dielectrophoretic force FDEP acts on any arbitrary shaped particle due to stationary wave nonuniform ac electric field. It is derived with slight modification of FDEP acting on spherical particles provided by Pohl,16

| (1) |

where (vol) is the volume of particle, εm is the permittivity of medium, Re[K(ω)] is real part of CM factor, and E is the applied electric field vector. CM factor for any arbitrary shaped particle is given as41

| (2) |

where Aα is the depolarization factor, subscript α relates to axis of the particle x, y, or z, and and are complex permittivities of particle (here myoglobin) and medium, respectively. They are given as

| (3) |

| (4) |

where εp and εm are permittivities of particle and medium, respectively, σp and σm are conductivities of particle and medium, respectively, ω is the angular frequency of the applied field, and . Theoretically, Re[K(ω)] varies from −0.5 to 1.16, 17 It is observed that CM factor varies with respect to axis of the particle. However, in the microchannel, the direction of DEP force acting on the particle is arbitrary. Hence, average CM factor is considered for the particle to calculate DEP force.

From Eq. 1, it is observed that DEP force becomes less effective for small particles, mainly with molecular sizes and submicron particles, where thermal effects are dominant. Most of the conventional DEP experiments demonstrated the response of particles with the change in frequency of the applied electric field to decide the crossover frequencies.42 This crossover frequencies can be calculated from complex CM factor K(ω). If Re[K(ω)]≥0, positive DEP occurs, otherwise it is negative DEP. The crossover frequency for any arbitrary shaped particle is given as

| (5) |

It is observed that fc can be calculated only when (σm−σp)∕(εp−εm)>0. If εp=εm, fc will tend to ∞, and practically, it is not possible to apply such frequency for observing two types of DEP effects.

DIELECTRIC MYOGLOBIN MODEL

In this section, the modeling of myoglobin molecule for DEP and the calculation of depolarization factors for the different shapes of molecule are discussed here. Myoglobin is a single chain globular protein of 153 amino acids containing heme (iron containing porphyrin) prosthetic group in the center, around which remaining apoprotein folds.43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49 It has molecular weight of 16.7 kDa.44, 45, 46, 48 It is the primary oxygen carrying pigment of muscle tissues. Myoglobin has isoelectric point at pH 8.5,3 where it acts as a neutral particle. Neurath50 proposed the myoglobin molecule as prolate spheroid of axial ratio 2.9:1 based on the Svedberg theory. Later, based on x-ray studies, myoglobin molecule represented as an oblate spheroid of axial ratio 2:1.44 Further, Grant et al.48 modeled the myoglobin molecule as a spheroidal shape with radius of 1.53 nm surrounded by a uniform shell of bound water with thickness of 0.35 nm. To the best of authors’ knowledge, there is no universally accepted exact shape of the myoglobin molecule due to its globular structure. Therefore, the shape of the myoglobin molecule is approximated as sphere, oblate, and prolate spheroids, as shown in Fig. 1. Depolarization factor for the CM factor varies according to the shape of the particle, which leads to a change in DEP force. Yang and Lei41 reported the calculation of depolarization factor for ellipsoidal, oblate, and prolate spheroid shapes. The sum of different axis depolarization factors for a particle should be unity. Considering a, b, and c as dimensions of the particles in the x-, y-, and z-axis directions, respectively, the depolarization factors are given as follows: For sphere (a=b=c),

| (6) |

for oblate spheroid (a=b>c),

| (7) |

| (8) |

and for prolate spheroid (a>b=c),

| (9) |

| (10) |

where eccentricity (e) is given as .

Figure 1.

Approximated shapes of myoglobin molecule: (a) Sphere; (b) oblate spheroid; and (c) prolate spheroid.

In the present study, the dimensions of different shapes of myoglobin molecule are derived based on the constant volume approach. According to Grant et al.,48 the volume of myoglobin is 15.0025 nm3. Based on this volume, the geometry of the different shapes of myoglobin is modeled as (i) a=b=c=r=1.53 nm (for sphere), (ii) a=b=1.9276 nm, c=0.9638 nm (for oblate spheroid), and (iii) a=2.4287 nm and b=c=1.2144 nm (for prolate spheroid). Three different cases are considered for each shape of the molecule based on the surface characteristics of myoglobin: (i) Isolated myoglobin molecule, (ii) myoglobin with effect of charge double layer using surface conductance method, and (iii) myoglobin with hydration layer. Isolated myoglobin molecule can be achieved by controlling the pH of the solution to 8.5 (isoelectric point of myoglobin). For pH other than 8.5, the myoglobin surface becomes charged and attracts the surrounding counter ions to form the charge double layer. Hughes et al.51 replaced this type of effect with a numerical value for surface conductance Ks (typically in the order of 0.1–3 nS). This value is used to calculate the particle conductivity given by σp=σpbulk+2Ks∕lc, where lc is the characteristic length of the particle (assumed to be cube root of volume of the particle) and σpbulk is the conductivity of bulk myoglobin solution. When myoglobin is suspended in water, it attracts one or two layers of bound water. Therefore, the third case considered here is the myoglobin with hydration layer. The permittivity and conductivity of the myoglobin molecule are different from the hydration layer. In this case, the DEP force shown in Eq. 1 is still valid if is replaced with effective complex permittivity , given by17, 41

| (11) |

where tα is the thickness of hydration layer along x-, y-, and z-axes, qα=a, b, and c for α=x, y, and z, respectively, and is the complex permittivity of hydration layer which can be written as

| (12) |

where εh and σh are permittivity and conductivity of hydration layer, respectively.

MATHEMATICAL MODELING

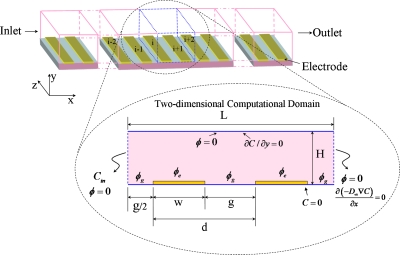

This section describes the mathematical modeling for dielectrophoretic manipulation of myoglobin molecules in aqueous solution. Figure 2 depicts the schematic view of the DEP microfluidics system considered for the manipulation of myoglobin under DEP effects. The device has infinite number of electrodes (−∞,…,−3,−2,−1,0,1,2,3,…,∞) at the bottom surface of the microchannel. The enlarged view in Fig. 2 shows the 2D computational domain considered for simulating the dielectrophoretic behavior of the myoglobin. Here L is the length of channel considered for computational purpose and H is the height. The bottom surface is embedded with array of parallel rectangular microelectrodes of width w and gap g in between the electrodes. Parameter d represents the sum of electrode width w and gap g and ϕ represents the applied electric potential. The notation i and (i+1) represent the ith and (i+1)th electrodes, respectively.

Figure 2.

Schematic view of DEP microfluidic device considered for manipulating the myoglobin molecules. Enlarged view shows the 2D computational domain considered for simulating the behavior of myoglobin molecules under DEP effects.

Governing equations

The governing equations for transporting myoglobin molecule under DEP are proposed in this section. The governing equations are Laplace and convection-diffusion-migration equations. The Laplace equation is used for calculating electric field distributions whereas convection-diffusion-migration equation is used for calculating the spatial myoglobin molecule concentration distribution in a system.

The study is based on the following assumptions: (i) The aqueous myoglobin solution flowing through the microchannel is at steady state, incompressible, and behaves like Newtonian fluids; (ii) the myoglobin molecules in aqueous solution are assumed as point size particles and hence their presence will not effect the electric field; (iii) no chemical reactions take place between the myoglobin molecules or between the molecules and walls of the channel; (iv) parabolic velocity profile across the channel is considered; (v) since the ratio of myoglobin and medium densities are approximately equal to the unity, which allows neglecting the gravitational sedimentation effect of myoglobin molecules,52, 53, 54 (vi) the range of fluid properties and applied voltages considered in this analysis, the heat dissipation, and temperature rise in the fluid, are very less.54, 55 Hence, ac electrothermal flow due to temperature gradients is neglected, (vii) for considered parameters or operating conditions, the movement of the particle due to ac electro-osmosis is very less as compared to the magnitude of DEP mobility.54, 55 Moreover, we are assuming that our suspension is neutral (myoglobin particles are maintained at isoelectric point3) so the formation of electric double layer (EDL) along the electrode can be neglected which is prior task for ac electro-osmosis; (viii) as per Docoslis et al.56 and Yang et al.,57 cell exposure to high frequency (e.g., 10 MHz to 40 MHz) electric fields does not cause any detrimental effects to cell growth and metabolism. Also the use of high frequency voltage waveforms does not induce the electrolysis and the corrosion of the electrodes.19 Therefore, the effects of high frequencies of applied voltage, i.e., exothermal effects are neglected.

Laplace equation

The electric field distribution in the system created by ac signal is described by the Laplace equation58

| (13) |

where ϕ is the applied electric potential. Solving Eq. 13 with appropriate boundary conditions will provide the potential distribution in the computational domain. This potential distribution is used to calculate the DEP force acting on the different shapes of myoglobin molecules.

Convection-diffusion-migration equation

The steady state concentration distribution of molecules in an aqueous solution with no chemical reactions can be given by convection-diffusion-migration equation as

| (14) |

where u is the medium velocity vector, C is the concentration of myoglobin molecules, D is diffusion coefficient tensor, Fmig is the migrational force vector on particles due to DEP, kB is the Boltzmann constant (1.380 650 3×10−23 m2 kg s−2 K−1), and T is the ambient temperature. The first term of Eq. 14 represents the transport due to convection, the second term is the transport due to diffusion, and the third term indicates the transport due to migration. Since the interactions between myoglobin molecules are neglected in the assumptions, diffusion tensor D can be simplified as the Stokes–Einstein diffusion coefficient D∞,

| (15) |

where f=12Apμ∕lc. Here f is the friction factor, Ap is the projected area of the particle, μ is the dynamic viscosity of medium, and lc is the characteristic length of particle. Both Ap and lc depend on the shape of the particle and the direction of flow over it. The diffusion coefficient D∞ for myoglobin is given as 1.5×10−11 m2∕s at 20 °C and 2.7×10−11 m2∕s at 37 °C.59 Particles in a microchannel can be migrated due to attractive or repulsive dielectrophoretic forces (Fmig=FDEP). The particle migration velocity for steady state problem can be given as

| (16) |

Combining and rearranging Eqs. 14, 15, 16 gives the following modified steady state convection-diffusion-migration equation:

| (17) |

where utot=u+umig. Solving Eq. 17 with appropriate boundary conditions will provide the spatial concentration distribution of myoglobin molecules in the computational domain. This concentration distribution is used to check the effectiveness of applying DEP force for manipulating myoglobin.

Nondimensional analysis

The manipulation of myoglobin molecules under DEP effects depends on the operating parameters, such as applied voltage, inlet velocity of solution, and concentration of molecules. It is observed that optimization among the operating parameters is also important to decide the effectiveness of DEP force for separating myoglobin. Therefore, a nondimensional analysis is conducted to correlate the parameters easily. The governing equations given in Eqs. 13, 17 can be nondimensionalized using the following parameters: ϕ*=ϕ∕Vo, ∇*=w∇, , and C*=C∕Cin. Here Vo is the peak electric potential applied on the electrodes, uin is the average inlet velocity of solution, and Cin is the inlet particle concentration. The governing equations after applying nondimensional parameters can be written as

| (18) |

| (19) |

where Pe is the Peclet number defined as uinw∕D∞. Appropriate boundary conditions to solve the above governing equations for manipulating myoglobin are provided in Fig. 2. ϕe and ϕg in the figure represents the electric potential at the electrodes and gap between the electrodes, respectively. The expressions for these potentials are given in Sec. 4C.

Solution methodology

The procedure for solving the model proposed in Secs. 4A, 4B is divided into two steps: (i) Evaluating the electric field distribution in the system using Eq. 18 and (ii) evaluating the particle spatial concentration distribution using Eq. 19. The solution obtained in step (i) is used to find the dielectrophoretic force and is incorporated into step (ii) to calculate the concentration distribution of particles in the system under DEP effects.

The potential distribution is solved analytically as well as numerically. The analytical expression for potential and electric field distributions, as well as DEP force in a microchannel containing parallel array of electrodes at the bottom surface have been already reported in many research papers on the basis of charge density method,33 Green’s theorem,60, 61, 62, 63 conformal mapping,64 and Fourier series.65 The closed form solutions (CFSs) are also developed for electric field and DEP forces by Morgan et al.65 and Chang et al.66 Wang et al.60 compared the analytical solution from Green’s theorem based method with charge density method, whereas Green et al.67 compared the analytical solution from the Fourier series method with numerical solution solved by finite element method. Clague and Wheeler61 and Crew et al.68 studied the effect of electrode dimensions, channel height, and applied voltage on gradient of electric field square. Molla and Bhattacharjee62, 63 compared Green’s theorem based analytical and finite element based numerical solutions, as well as studied the effect of applied voltages and frequencies on DEP force. In the present study, simple and modified analytical expressions for electric field and gradient of electric field square are derived based on Green’s theorem method. In addition, a mesh independent numerical solution using finite element method is also solved. These analytical and numerical solutions are compared to the Fourier series method65 and CFSs by Morgan et al.65 and Chang et al.66

Here, the analytical expressions for potential, electric field, and gradient of square electric field using Green’s theorem method are derived. The potential and electric field distributions along the length of the electrodes are uniform for array of parallel rectangular electrodes. Therefore, the in-plane dimension of the system is neglected here. The Laplace equation for 2D system is solved, as shown in Fig. 2. Sinusoidal voltage of phase difference 2π∕n and angular frequency ω are applied on the electrodes for producing nonuniform electric field. For myoglobin under stationary wave DEP, the value of n will be 2.60, 61, 63 The analytical solution for the Laplace equation using Green’s theorem for upper half space, y≥0, is given as

| (20) |

where x0 represents the point in the x direction on the electrode plane and ϕ represents the surface potential on the electrode plane. The potential distribution is solved by piecewise integration of Eq. 20 with surface potential boundary conditions on electrode plane. Assuming the linear variation of surface potential at gap between the electrodes,60, 61, 62, 63, 65, 66, 67, 68 the surface potential boundary conditions on electrodes and gap between electrodes are given as

| (21) |

| (22) |

where S={cos(ωt+2π(i+1)∕n)−cos(ωt+2πi∕n)}∕g, the limits of x0 for electrodes vary from id−w∕2 to id+w∕2 and the limits of x0 for gap between the electrodes vary from id+w∕2 to (i+1)d−w∕2. Here i is the ith electrode and varies from −∞ to +∞. Substituting Eqs. 21, 22 into Eq. 20 and integrating yields the potential distribution expression as

| (23) |

where pi=id−w∕2, qi=id+w∕2, and pi+1=(i+1)d−w∕2. Electric field distribution in the system can be calculated from the above potential distribution expression using E=−∇ϕ. The term ∇(E⋅E) in Eq. 1 can be expressed for a 2D computational domain as follows:

| (24) |

| (25) |

where Ex is electric field in the x direction and Ey is electric field in the y direction. Reader can refer to the Appendix0 for the detailed expressions for Ex, Ey, ∂Ex∕∂x, ∂Ey∕∂x, ∂Ex∕∂y, and ∂Ey∕∂y.

Analytical methods give exact solution to the potential and electric field distributions in the system as well as DEP force on the myoglobin molecules. This analytical method is only applicable to simplified geometries (mainly 2D), such as infinite array of parallel electrodes. However, most of the applications, electrode geometries, and layouts are different and not possible to simplify as 2D models. Solving the 2D convection-diffusion-migration equation by analytical methods is a tedious process due to elliptical nature of equation. Therefore, numerical method is implemented to obtain approximate solutions for electric field and myoglobin molecule concentration distributions in the system. The governing equations and the boundary conditions described earlier are implemented in a finite element based software COMSOL MULTIPHYSICS version 3.5a to study the dielectrophoretic behavior of myoglobin. To obtain the numerical solution, only two electrodes are used for simulations instead of array of electrodes, as it is periodic in nature (as shown in Fig. 2). The 2D computational domain is discretized with quadrilateral elements. The electrode edges are discretized with finer elements to capture the effect of high intensity electric field. The model uses Lagrange-quadratic elements for calculating parameters inside the domain, such as electric potential, electric field, etc. The structured (mapped) mesh scheme is used to discretize the computational domain. The simultaneous linear equations produced by the finite element method are solved using direct elimination solver (PARDISO). A mesh independent finite element solution is achieved with around 12 000 elements. The convection-diffusion-migration model is solved with small artificial isotropic diffusion (=0.05) to improve the convergence and to reduce the oscillations in concentration profile.69

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

Results for the dielectrophoretic behavior of the myoglobin molecules in aqueous solution are presented in this section. For the simulations, the length and height of the channels are taken as L=400 nm and H=300 nm, respectively. The length of the channel depends on the number of electrodes in that array. The electrode width and gap between the electrodes are given as w=100 nm and g=100 nm, respectively. The thickness of the electrodes is assumed to be very small as compared to the height of channel, and hence neglected in the simulations. The dielectric properties of the myoglobin and aqueous solution considered for the analysis48 are given as εp=83.5εo, εm=78.5εo, σp=0.01 S∕m, and σm=0.065 S∕m. Here ε0=8.854×10−12 C2 N−1 m−2 is the permittivity of free space. The simulations are conducted at applied voltages of 1–100 V at different frequencies. The aqueous solution of myoglobin is maintained at 20 °C and is pumped into the microchannel with concentration Cin=1 mol∕m3 and inlet average velocity uin=0.1 mm∕s. Thus, the nondimensional parameters used in the present study are given as L*=4, H*=3, w*=1, and g*=1.

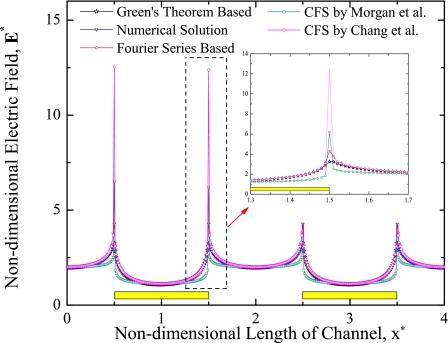

Figure 3 shows the comparison of nondimensional electric field along the length of channel near the electrodes for Green’s theorem based analytical solution, Fourier series based analytical solution,65 finite element based numerical solution, CFS by Morgan et al.,65 and CFS by Changet al.66 The horizontal axis in this figure shows the nondimensional length of the channel (x*), whereas vertical axis shows the nondimensional electric field (E*). The different symbols in the figure indicate the different solution methods. The electric field is maximum at the edges of the electrodes and minimum elsewhere. However, the magnitude of the electric field at the center of the electrode is very less than the electric field at the midpoint of the gap between the electrodes. The excellent agreement is observed between Green’s theorem based analytical solution and finite element based numerical solution. However, slight discrepancies are identified at the edge of the electrode for Green’s theorem based∕numerical solution with Fourier series based analytical solution and CFS by Chang et al. The peak magnitude for nondimensional electric field is observed for CFS by Chang et al. compared to other solution methods. CFS by Morgan et al. has slight flat profile along the electrodes∕gap between electrodes compared to semicircular curved profile of nondimensional electric field for other solution methods.

Figure 3.

Comparison of nondimensional electric field along the length of channel near the electrodes for different solution methods.

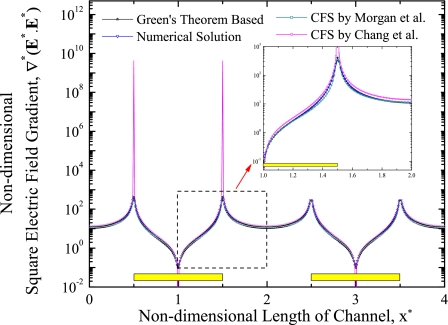

As discussed earlier, DEP force depends on the volume of myoglobin, real part of the CM factor, and the gradient of square electric field. Since the effect of presence of the myoglobin molecules on electric field is neglected, the gradient of square electric field is independent of shape, size, and properties of myoglobin. Hence, the variation of square electric field gradient along the length of channel and height of the channel is studied. Figure 4 illustrates the comparison of nondimensional square electric field gradient with respect to the length of channel near the electrode plane for Green’s theorem based analytical solution, numerical solution based on COMSOL MULTIPHYSICS, CFS by Morgan et al.,65 and CFS by Chang et al.66 The horizontal axis in this figure shows the nondimensional length of the channel (x*) and vertical axis shows the nondimensional square electric field gradient (∇*(E*⋅E)*). The different solution methods are indicated with different symbols in the figure. The results show that the square electric field gradient is maximum at the edges of the electrodes and minimum elsewhere. The magnitude of nondimensional square electric field gradient is in the range of 10−1–1010 for an applied electric potential of ϕ*=1. The attraction or repulsion of particles can be achieved significantly due to large amount of electric field at the edges of the electrodes. The variation profile of nondimensional square electric field is almost matched with Green’s theorem based solution, numerical solution, and CFSs by Morgan et al.65 and Chang et al.66 The Fourier series based solution is not compared here due to some large discrepancies with other solution methods. The excellent agreement is identified with Green’s theorem based solution and numerical solution, whereas some slight difference in nondimensional square electric field gradient is observed along the length of the channel (except the edges of electrode) with other solution methods. CFSs by Chang et al.66 and Morgan et al.65 are providing the maximum nondimensional square electric field gradient at the edges of the electrode compared to Green’s theorem method and finite element method.

Figure 4.

Comparison of nondimensional square electric field gradient along the length of channel near the electrodes for different solution methods.

Figure 5 depicts the comparison of nondimensional square electric field gradient with respect to the height of channel at electrode edge, midpoint of electrode, and midpoint of gap between the electrodes with different solution methods. The horizontal axis in this figure shows the nondimensional height of the channel (y*), whereas vertical axis shows the nondimensional square electric field gradient (∇*(E*⋅E)*). The nondimensional square electric field gradient is exponentially decayed along the height of channel at the edges of the electrodes. At midpoint of electrodes, the square electric field gradient is monotonically increased up to y*=0.32 and then linearly decreased along the height of channel. The linear decaying of square electric field is observed at the mid point of gap between the electrodes. At the height y*=1.25, the gradient of square electric field is constant throughout the channel length and magnitude is decreased along the height of channel. This decides the effectiveness of DEP force in the channel. The profiles for variation in nondimensional square electric field gradient with different solution methods are matched for all the cases. There is some discrepancy with profiles along the height of channel at midpoint of electrodes for Green’s theorem based solution or numerical solution with CFS by Morgan et al.65 and Chang et al.66

Figure 5.

Comparison of nondimensional square electric field gradient along the height of channel at edge of the electrode, midpoint of the electrode, and midpoint of gap between the electrodes for different solution methods.

Figure 6 shows the dependence of nondimensional square electric field gradient on applied voltage along the length of channel near the electrodes. The horizontal axis in this figure shows the nondimensional length of the channel (x*), whereas vertical axis represents the nondimensional gradient of the square electric field. Different symbols indicate the different voltages in the figure. It is observed that square electric field gradient is directly proportional to the applied voltage. The magnitude of peak nondimensional square electric field gradient is increased from 3×102 to 3×106 for an increase in nondimensional applied voltage (ϕ*) from 1 to 100, respectively.

Figure 6.

Comparison of nondimensional square electric field gradient along the length of channel near the electrodes for different nondimensional applied voltages.

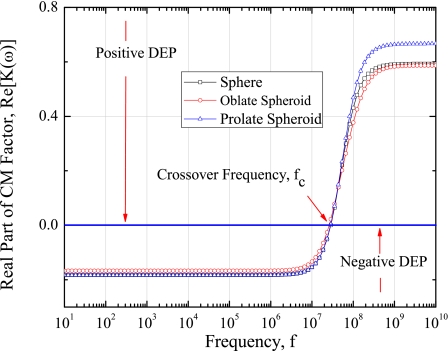

The type of DEP effect on the myoglobin molecule is determined by observing the real part of CM factor. As discussed earlier, this real part of CM factor depends on the permittivity and conductivity of myoglobin molecule and aqueous solution, respectively, and frequency of the applied electric field. Figure 7 presents the comparison of real part of CM factor for different approximated shapes of myoglobin molecule in the applied electric field frequency range of 10 Hz–10 GHz. Here horizontal axis represents the frequencies in the logarithmic scale whereas the vertical axis shows the real part of CM factor. The real part of CM factor depends on the axis of particle for arbitrary shapes, such as oblate and prolate spheroids. So, the average value for real part of CM factor is considered in the study. The real part of CM factor for all the approximated shapes is equal to zero at or around 40 MHz of applied electric field frequency. It has negative DEP for the frequency less than 40 MHz and positive DEP for the frequency more than 40 MHz. This indicates that 40 MHz is the crossover frequency (fc) of the myoglobin for given material properties. It is also found that the real part of CM factor is more for sphere compared to the prolate and oblate spheroids in the frequency range of 10 Hz–4.5 MHz. The real part of CM factor is same for all shapes at 4.5 MHz. The real part of CM factor increased in sigmoidal curve from 2 to 100 MHz. Beyond 100 MHz, the real part of CM factor for all shapes is same and constant throughout the frequency range.

Figure 7.

Comparison of real part of the CM factor with respect to frequency of the applied electric field for different shapes of the myoglobin molecule.

Figure 8 shows the comparison of crossover frequency for different shapes of myoglobin molecules with respect to conductivity of medium. Conductivity of medium was indicated on the logarithmic scale of the x-axis whereas the crossover frequency for all shapes of molecule was shown on logarithmic scale of the y-axis. Different symbols in Fig. 8 indicate the different particle conductivities. In Fig. 8, it is found that the crossover frequency for any shape of the myoglobin is same at any particle conductivity and it is increased with an increase in the medium conductivity. If the conductivity of particle is more than the conductivity of medium, the particles experienced positive DEP even though it is subjected to frequency lesser than the crossover frequency. The crossover frequency is determined for only two cases: (i) εp>εm and σp<σm and (ii) εp<εm and σp>σm. The other two cases do not have crossover frequency. They are (i) εp>εm and σp>σm and (ii) εp<εm and σp<σm. Figures 78 provide the operating frequency range to observe the response of myoglobin molecules under DEP effects. This crossover frequency analysis will be helpful in separating the myoglobin from other particles or from the whole blood sample.

Figure 8.

Comparison of crossover frequency with respect to change in conductivity of medium for different shapes of the myoglobin molecule.

The second case considered for myoglobin will increase its conductivity due to EDL formation. The effect of an increase in myoglobin conductivity on crossover frequency is same as depicted in Fig. 8. Figure 9 provides the effect of real part of CM factor with respect to frequency of applied electric field due to hydration layer on myoglobin. Here horizontal axis represents the frequencies in the logarithmic scale and the vertical axis shows the real part of CM factor. It is evident from the figure that the real part of CM factor for all approximated shapes is equal to zero at or around 28 MHz of applied electric field frequency. It has negative DEP for the frequency less than 28 MHz and positive DEP for the frequency more than 28 MHz. This indicates that 28 MHz is the crossover frequency of the myoglobin for given material properties at the time of hydration layer formation. Also, the real part of CM factor in the frequency range of 10 Hz–28 MHz is larger for oblate spheroid compared to prolate spheroid and sphere. The real part of CM factor has same value for all shapes at 28 MHz and it is the crossover frequency for myoglobin with hydration layer. The real part of CM factor increased in sigmoidal curve from 10 to 400 MHz. Beyond 28 MHz, the real part of CM factor for prolate spheroid is larger compared to sphere and oblate spheroids.

Figure 9.

Comparison of real part of the CM factor with respect to frequency of the applied electric field for different shapes of myoglobin with the hydration layer.

Figures 1011 show the positive and negative DEP effects on the myoglobin molecules. Figure 10 illustrates the comparison of DEP force along the length of channel near the electrodes for different shapes of myoglobin at 50 MHz and 10 V applied electric potential. Figure 11 exhibits the comparison of DEP force along the length of channel near the electrodes for different shapes of the myoglobin at 1 KHz and 10 V applied electric potential. The variation profiles for DEP force and gradient of square electric field are similar along the length of the channel near the electrodes. Due to the variation of CM factor with frequency of applied electric field, the values of DEP forces have been changed for different shapes of myoglobin molecule. The peak value of DEP force in case of positive DEP effect is less than that observed in negative DEP effect. The magnitude of DEP force on different approximated shapes of the myoglobin molecules is same in the positive DEP effect. The peak magnitudes of DEP force on different shapes of myoglobin are not matched in the negative DEP effect. The peak value of DEP force is more for oblate spheroid as compared to other shapes. This happens due to variation in the CM factor in negative DEP region. However, the magnitudes are not significantly changed for these shapes. The magnitude of DEP forces are in the order of 10−12–10−10 at the edges of the electrode.

Figure 10.

Comparison of DEP force on different shapes of the myoglobin molecule along the length of channel near the electrodes at 50 MHz frequency and 10 V applied voltage.

Figure 11.

Comparison of DEP force on different shapes of the myoglobin molecule along the length of channel near the electrodes at 1 KHz frequency and 10 V applied voltage.

The effectiveness of this DEP force for manipulating nanosize myoglobin molecules can be evaluated by comparing the ratio of DEP force to Brownian force. If this ratio is greater than or equal to one, the DEP force is effective in manipulating the myoglobin, otherwise it is not possible due to thermal randomization. According to Pohl16 and Washizu et al.,35 the condition for checking the ratio of DEP force to Brownian motion is given by integrating Eq. 1,

| (26) |

This condition is satisfied for the DEP forces plotted in Figs. 1011.

Figure 12 shows the variation in nondimensional concentration of the myoglobin molecules inside the microchannel. The molecules are levitated to a certain height due to repulsive DEP forces. The concentration of different shapes of the myoglobin molecule does not have a significant difference in the surface plot. Figure 13 shows the variation in concentration of the myoglobin molecules along the height of channel at different locations on the length of channel. Horizontal axis is a nondimensional distance (y*) and vertical axis is a nondimensional concentration (C*). The concentration of molecules is maximum at y*=1.25 height, beyond which there is no significant difference in the DEP force along the length of the channel. These results show that DEP force is effective to manipulate as well as to control the Brownian motion of myoglobin. The shape of the myoglobin molecule does not have significant effect on magnitude of the DEP force. The validation of results, such as crossover frequencies and levitation heights of the myoglobin with experiments, are in process.

Figure 12.

Variation of mass concentration of the myoglobin molecules inside the microchannel under DEP effects at 1 KHz and 10 V applied voltage.

Figure 13.

Variation of mass concentration of the myoglobin molecules along the height of channel under DEP effects at 1 KHz and 10 V applied voltage.

CONCLUSIONS

Mathematical modeling and numerical simulation of dielectrophoretic behavior of a myoglobin molecule in a microchannel with parallel array of electrodes at the bottom wall of the microchannel are investigated. A dielectric myoglobin model is developed by approximating the shape of the myoglobin molecule as sphere, oblate, and prolate spheroids. A generalized dielectrophoretic force acting on respective shapes of the molecule is derived. Both the nondimensional electric field and square electric field gradients are calculated with Green’s theorem method and finite element method. The results are also compared to the Fourier series method65 and CFSs by Morgan et al.65 and Chang et al.66 The excellent agreement between Green’s theorem based analytical solution and numerical solutions is observed. The crossover frequency of 40 MHz is obtained for given properties of the myoglobin molecules. This crossover frequency is increased with an increase in conductivity of medium as well as myoglobin. The hydration layer reduced the crossover frequency of myoglobin molecules to 28 MHz. Both positive and negative DEP effects on the myoglobin molecules are observed at 50 MHz and 1 kHz applied frequencies, respectively. The effect of different shapes of myoglobin on the DEP force is studied and it is observed that there is no significant effect on DEP force. The concentration of molecules is maximum at y*=1.25 height at 1 kHz frequency and 10 V applied voltage. These findings give the potential of DEP force for manipulating nanoscale biomolecules.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Alberta Ingenuity Fund in the form of the scholarship provided to NSKG.

APPENDIX: DETAILS OF DIFFERENT ANALYTICAL EXPRESSIONS

The detailed expressions for Ex, Ey, ∂Ex∕∂x, ∂Ey∕∂x, ∂Ex∕∂y, and ∂Ey∕∂y are given in this section. These components are derived by differentiating the potential distribution function given in Eq. 22. The expressions derived in this paper for potential, electric field in the x and y directions are similar to those of Wang et al.,60 Clague and Wheeler,61 and Molla and Bhattacharjee62, 63 with different notations. Here the simplified and modified expressions are provided. The following expressions can be used to calculate the DEP forces by substituting into Eq. 1:

| (A1) |

| (A2) |

| (A3) |

| (A4) |

References

- Mayr B. M., Kohlbacher O., Reinert K., Sturm M., Gropl C., Lange E., Klein C., and Huber C. G., J. Proteome Res. 5, 414 (2006). 10.1021/pr050344u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Wang Q., Ren L., Wang X., Wan Z., Liu W., Li L., Zhao H., Li M., Tong D., and Xu J., Colloids Surf., B 72, 112 (2009). 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evan J., Novel data analysis technique aids heart attack diagnosis, February 2006, see also URL Lab Informatics, separationsNOW.com.

- Darain F., Yager P., Gan K. L., and Tjin S. C., Biosens. Bioelectron. 24, 1744 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkoff G. T., Hill R. L., Brown D. M., and Tyler F. H., J. Biol. Chem. 237, 2820 (1962). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts A. M., Invest. Ophthalmol. 4, 531 (1965). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boesken W. H., Boesken S., and Mamier A., Res. Exp. Med. 171, 71 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiaojia H., Yuchai T., Weiping L., Shuxuan Y., Xiaopeng L., Bing X., Yushui W., Li L., and Zhongyong Z., Clin. Chim. Acta 273, 119 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasso J., Lee J., Bach H., and Mage R. G., J. Immunol. Methods 263, 23 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou M., Gao H., Li J., Xu F., Wang L., and Jiang J., Anal. Biochem. 374, 318 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Regan T. M., O’Riordan L. J., Pravda M., O’Sullivan C. K., and Guilbault G. G., Anal. Chim. Acta 460, 141 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Haas R. G., Anal. Chem. 65, 444 (1993). 10.1021/ac00060a614 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Panteghini M., Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 61, 95 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moigne F. L., Beauvieux M. -C., Derache P., and Darmon Y. -M., Clin. Biochem. 35, 255 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panteghini M., Linsinger T., Wu A. H. B., Dati F., Apple F. S., Christenson R. H., Mair J., and Schimmel H., Clin. Chim. Acta 341, 65 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohl H. A., Dielectrophoresis (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1978). [Google Scholar]

- Jones T. B., Electromechanics of Particles (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1995). 10.1017/CBO9780511574498 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M. P., Nanoelectromechanics in Engineering and Biology (CRC, Boca Raton, FL, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- Lin J. T. Y. and Yeow J. T. W., Biomed. Microdevices 9, 823 (2007). 10.1007/s10544-007-9095-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen N. T. and Werely S. T., Fundamentals and Applications of Microfluidics (Artech House, Boston, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- Church C., Zhu J., Wang G., Tzeng T. -R. J., and Xuan X., Biomicrofluidics 3, 044109 (2009). 10.1063/1.3267098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon Z., Mazur J., and Chang H. -C., Biomicrofluidics 3, 044108 (2009). 10.1063/1.3257857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrier G. A., Hladio A. N., Thomson D. J., Bridges G. E., Hedayatipoor M., Olson S., and Freeman M. R., Biomicrofluidics 2, 044102 (2008). 10.1063/1.2992127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikesit G. O. F., Markesteijn A. P., Piciu O. M., Bossche A., Westerweel J., Young I. T., and Garini Y., Biomicrofluidics 2, 024103 (2008). 10.1063/1.2930817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F., Yang X., Jiang H., Bulkhaults P., Wood P., Hrushesky W., and Wang G., Biomicrofluidics 4, 013204 (2010). 10.1063/1.3279786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X., Yi H., and Ni Z., Biomicrofluidics 4, 013202 (2010). 10.1063/1.3279788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang H., Lee D. -H., Choi W., and Park J. -K., Biomicrofluidics 3, 014103 (2009). 10.1063/1.3086600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei M. -T., Junio J., and Ou-Yang H. D., Biomicrofluidics 3, 012003 (2009). 10.1063/1.3058569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J. -R., Juang Y. -J., Wu J. -T., and Wei H. -H., Biomicrofluidics 2, 044103 (2008). 10.1063/1.3037326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewpiriyawong N., Yang C., and Lam Y. C., Biomicrofluidics 2, 034105 (2008). 10.1063/1.2973661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basuray S. and Chang H. -C., Biomicrofluidics 4, 013205 (2010). 10.1063/1.3294575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunthawin S., Wanichapichart P., Tuantranont A., and Coster H. G. L., Biomicrofluidics 4, 014102 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. B., Huang Y., Burt J. P. H., Markx G. H., and Pethig R., J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 26, 1278 (1993). 10.1088/0022-3727/26/8/019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lapizco-Encinas B. H. and Rito-Palomares M., Electrophoresis 28, 4521 (2007). 10.1002/elps.200700303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washizu M., Suzuki S., Kurosawa O., Nishizaka T., and Shinohara T., IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 30, 835 (1994). 10.1109/28.297897 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bakewell D. J. G., Hughes M. P., Milner J. J., and Morgan H., Proceedings of the 20th Annual International Conference on IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society1998. (unpublished), Vol. 20, p. 1079.

- Hughes M. P. and Morgan H., Anal. Chem. 71, 3441 (1999). 10.1021/ac990172i [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L., Brody J. P., and Burke P. J., Biosens. Bioelectron. 20, 606 (2004). 10.1016/j.bios.2004.03.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L., Burke P. J., and Brody J. P., Proc. SPIE 5331, 126 (2004). 10.1117/12.549026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke R. W., White S. S., Zhou D., Ying L., and Klenerman D., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 44, 3747 (2005). 10.1002/anie.200500196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C. Y. and Lei U., J. Appl. Phys. 102, 094702 (2007). 10.1063/1.2802185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castellarnau M., Errachid A., Madrid C., Juarez A., and Samitier J., Biophys. J. 91, 3937 (2006). 10.1529/biophysj.106.088534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlecht P., Mayer A., Hettner G., and Vogel H., Biopolymers 7, 963 (1969). 10.1002/bip.1969.360070611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant E. H. and South G. P., Biochem. J. 122, 765 (1971). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South G. P. and Grant E. H., Proc. R. Soc. London, Ser. A 328, 371 (1972). 10.1098/rspa.1972.0083 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grant E. H., Mitton B. G. R., and South G. P., Biochem. J. 139, 375 (1974). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough S. R., J. Solution Chem. 12, 729 (1983). 10.1007/BF00647384 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grant E. H., McClean V. E. R., Nightingale N. R. V., and Sheppard R. J., Bioelectromagnetics (N.Y.) 7, 151 (1986). 10.1002/bem.2250070206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruderman G. and Oro J. R. D. X., J. Biol. Phys. 18, 167 (1991). 10.1007/BF00417805 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neurath H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 61, 1841 (1939). 10.1021/ja01876a060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M. P., Morga H., and Flynn M. F., J. Colloid Interface Sci. 220, 454 (1999). 10.1006/jcis.1999.6542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achterhold K. and Parak F. G., J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 15, S1683 (2003) 10.1088/0953-8984/15/18/302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Green N. G., Ramos A., and Morgan H., J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 33, 632 (2000). 10.1088/0022-3727/33/6/308 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos A., Ramos A., Gonzalez A., Green N. G., and Morgan H., J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 36, 2584 (2003). 10.1088/0022-3727/36/20/023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos A., Morgan H., Green N. G., and Castellanos A., J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 31, 2338 (1998). 10.1088/0022-3727/31/18/021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Docoslis A., Kalogerakis N., and Behie L. A., Cytotechnology 30, 133 (1999). 10.1023/A:1008050809217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Banada P. P., Bhunia A. K., and Bashir R., J. Bio. Eng. 2, 25fc (2008), can be seen at http://www.jbioleng.org/content/2/1/6. 10.1186/1754-1611-2-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masliyah J. and Bhattacharjee S., Electrokinetic and Colloid Transport Phenomena (Willey Interscience, Hoboken, NJ, 2006). 10.1002/0471799742 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moll W., Pfluegers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 299, 247 (1968). 10.1007/BF00362587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Wang X. B., Becker F. F., and Gascoyne R. C. P., J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 29, 1649 (1996). 10.1088/0022-3727/29/6/035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clague D. S. and Wheeler E. K., Phys. Rev. E 64, 026605 (2001). 10.1103/PhysRevE.64.026605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molla S. H. and Bhattacharjee S., J. Membr. Sci. 255, 187 (2005). 10.1016/j.memsci.2005.01.034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Molla S. H. and Bhattacharjee S., J. Colloid Interface Sci. 287, 338 (2005). 10.1016/j.jcis.2004.06.096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia M. and Clague D., J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 33, 1747 (2000). 10.1088/0022-3727/33/14/315 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan H., Alberto G. I., David B., Green N. G., and Ramos A., J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 34, 1553 (2001). 10.1088/0022-3727/34/10/316 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang D. E., Loire S., and Mezic I., J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 36, 3073 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Green N. G., Ramos A., and Morgan H., J. Electrost. 56, 235 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Crews N., Darabi J., Voglewede P., Guo F., and Bayoumi A., Scand J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 61, 95 (2001).11347986 [Google Scholar]

- Molla S. H. and Bhattacharjee S., Langmuir 23, 10618 (2007). 10.1021/la701016p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]