Abstract

Background:

During metastasis, cancer cells migrate away from the primary tumour and invade the circulatory system and distal tissues. The stimulatory effect of growth factors has been implicated in the migration process. Placental growth factor (PlGF), expressed by 30–50% of primary breast cancers, stimulates measurable breast cancer cell motility in vitro within 3 h. This implies that PlGF activates intracellular signalling kinases and cytoskeletal remodelling necessary for cellular migration. The PlGF-mediated motility is prevented by an Flt-1-antagonising peptide, BP-1, and anti-PlGF antibody. The purpose of this study was to determine the intracellular effects of PlGF and the inhibiting peptide, BP-1.

Methods:

Anti-PlGF receptor (anti-Flt-1) antibody and inhibitors of intracellular kinases were used for analysis of PlGF-delivered intracellular signals that result in motility. The effects of PlGF and BP-1 on kinase activation, intermediate filament (IF) protein stability, and the actin cytoskeleton were determined by immunohistochemistry, cellular migration assays, and immunoblots.

Results:

Placental growth factor stimulated phosphorylation of extracellular-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2 (pERK) in breast cancer cell lines that also increased motility. In the presence of PlGF, BP-1 decreased cellular motility, reversed ERK1/2 phosphorylation, and decreased nuclear and peripheral pERK1/2. ERK1/2 kinases are associated with rearrangements of the actin and IF components of the cellular cytoskeleton. The PlGF caused rearrangements of the actin cytoskeleton, which were blocked by BP-1. The PlGF also stabilised cytokeratin 19 and vimentin expression in MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells in the absence of de novo transcription and translation.

Conclusions:

The PlGF activates ERK1/2 kinases, which are associated with cellular motility, in breast cancer cells. Several of these activating events are blocked by BP-1, which may explain its anti-tumour activity.

Keywords: PlGF, breast cancer, motility, BP-1 peptide, Flt-1, IF protein

A growing body of clinical and experimental evidence implicates placental growth factor (PlGF) in pathologies, such as abnormal blood vessel formation and cancer progression (DePrimo et al, 2007; Ho et al, 2007; Fischer et al, 2007, 2008), including breast cancer (Parr et al, 2005). The PlGF is a member of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) family first isolated from the placenta, but later found to be normally expressed during wound healing and in the thyroid (Li et al, 2006; Maes et al, 2006; Kagawa et al, 2009). In cancer cells, PlGF mediates a number of cellular activities that promote metastasis, including attraction of endothelial cells for establishment of a blood supply, enhanced invasiveness, and cellular movement (Taylor et al, 2003; Casalou et al, 2007; Taylor and Goldenberg, 2007). In all 30–50% of human breast cancers express constitutive PlGF and its expression can be induced de novo in other PlGF-negative tumour cells that survive radioimmunotherapy (Taylor et al, 2002; Taylor and Goldenberg, 2007).

Alteration of growth factor receptor type or frequency, such as HER2/neu in breast cancer, is associated with poor prognosis or metastasis. The three known PlGF receptors are the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) Flt-1 (also designated as VEGFR1), and the glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored co-receptors, neuropilin-1 and -2 (NRP-1, NRP-2). Flt-1 is ectopically expressed by breast cancer tissue, blood vessels, and breast cancer cell lines, in contrast to normal breast tissue, in which NRP-1 is present and Flt-1 is absent or near background (Starzec et al, 2006; Taylor and Goldenberg, 2007). Therefore, it is possible that Flt-1 transmits PlGF signals, including those that lead to enhanced motility, in breast cancer.

Cellular motility is essential in the metastatic process, which requires cellular migration away from the primary tumour, invasion of surrounding tissue, entrance into the circulation, and then migration into a distant organ or tissue. It is not surprising then that alterations in cytoskeletal components responsible for motility mark the progression from a normal to neoplastic and then to a metastatic phenotype (Brotherick et al, 1998). The cytoskeleton is composed of three elements, actin microfilaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments (IFs). Some pro-metastatic growth factors, such as epidermal growth factor, cause actin microfilaments to disassemble stress fibres, restructure focal adhesion complexes, and form actin-containing lamellipodia and filopodia for migration (Ronnstrand and Heldin, 2001; Harper et al, 2007). The PlGF, as it stimulates cellular migration, may also be a pro-metastatic growth factor.

The IFs, which include cytokeratins (CKs) and vimentin, are structural components that allow cells and tissue to endure stress, but IFs also participate in other cellular functions (Helfand et al, 2004; Oriolo et al, 2007). These proteins vary according to cell type and cellular differentiation stage in normal tissue, and are often dysregulated in primary cancers and cancer cell lines. The specific intracellular consequences of altered IF expression are uncertain, but it has been shown that co-expression of certain CKs and vimentin augments carcinoma cell motility (Domagala et al, 1990; Chu et al, 1996; Hendrix et al, 1997; Thomas et al, 1999), and this was demonstrated more specifically in a recent report by Schoumacher et al (2010). CK8, CK18, and CK19 are expressed by normal breast tissue, but often CK19 predominates in the progression to malignancy, and its expression with vimentin, a mesenchymal IF, which is not normally expressed by epithelium, is indicative of poor outcome (Brotherick et al, 1998). This may be due to its role in promoting cellular mechanical stability, its participation in cellular movement, and its recently established role in stabilising invadopodia of metastasising cells (Eckes et al, 1998; Schoumacher et al, 2010).

The changes in cytoskeletal microfilament and IF necessary for migration or metastasis of cancer cells can be mediated through activation of a number of intracellular pathways (Tsuganezawa et al, 2002). Common intracellular targets of activated RTKs are the extracellular-regulated kinases (ERKs) and phosphotidylinositiol-3-kinase (PI3K).

In a previous report, we investigated PlGF/Flt1 inhibition using the PlGF/Flt-1-expressing MDA-MB-231 xenograft metastatic model, and the PlGF receptor-inhibiting peptide, BP-1. Treatment with BP-1 was sufficient to inhibit the formation of pulmonary metastases in mice implanted with MDA-MB-231 (Taylor and Goldenberg, 2007). Using tissue microarrays it was also observed that 30–50% of primary breast cancers express PlGF, Flt-1, or both, whereas normal breast tissue expressed neither. Expression of Flt-1 was not confined to the blood vessels, but was also on tumour cells, and on breast tumour cell lines. This suggested that PlGF may not only serve as an angiogenic factor, which it is, but may also directly affect tumour cells expressing Flt-1. Evidence for the effect of PlGF on tumours is also offered by clinical data documenting that PlGF expression by human tumours, including breast cancers, is predictive of poor clinical outcome, which is characterised by aggressive disease, post-treatment recurrence, and metastases (Chen et al, 2004; Parr et al, 2005; Wei et al, 2005; Ho et al, 2007; Escudero et al, 2010).

This paper documents the results of in vitro analyses to determine how PlGF promotes cellular motility. To do this, the activation of several kinases by PlGF was investigated. The other goal of this study was to determine how the peptide, BP-1, which demonstrates anti-motility activity in vitro and anti-metastatic activity in breast cancer xenograft models, exerts its anti-tumour effects (Taylor and Goldenberg, 2007). The focus is on early changes in cellular motility occurring within 1–3 h of exposure to PlGF. The aggressive breast cancer cell line, MDA-MB-231, which expresses PlGF and Flt-1, was used primarily because it measurably increases migration in the presence of PlGF within 3 h of exposure.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and treatments

Cell lines were from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Treatment of cells with BP-1 (1 μM) and PlGF (1 nM) was previously reported (Taylor and Goldenberg, 2007). The concentration of inhibitors was actinomycin D (ActD, de novo transcription), 1 or 10 μg ml−1 (migration assay), 1 μg ml−1 (immunoblots); cycloheximide (CHX), 3 μg ml−1 (de novo translation); PD98059 (PD98) (MEK pathway), 50 μM; LY294002, 2 μM (PI3K pathway) (all from Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA), wortmannin (non-specific PI3K inhibitor), 5 nM (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA).

Migration assay

Spontaneous migration (wound) assays were performed as previously described (Ilic et al, 1995; Mitra et al, 2005; Wong et al, 2005; Taylor and Goldenberg, 2007) using cells treated with PlGF, BP-1, inhibitor, or with antibody (1 μg ml−1). Cells were treated with PlGF either simultaneously with, or 15 min before inhibitors, as indicated. At the indicated time points up to 3 h, coverslips were stained, mounted, and examined microscopically by two blinded researchers. Five to ten × 100 fields per slide were evaluated by counting cells separated from the wound edges and that appeared to be migrating. In two instances, results were normalised by a constant factor (e.g., two-fold) to diminish inter-experimental variation. The results are reported as the average number of cells migrating into the wound per × 100 field±s.d. from 5 to 10 fields per coverslip; one to two coverslips per treatment per experiment, from two to five experiments, depending on the treatment.

Immunoblots

Immunoblot analysis was performed using standard methods (Chu et al, 1996). In all, 10 μg of protein per lane was loaded on gels; the primary antibody concentration was 1–5 μg ml−1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA, or Cell Signaling Technology, Inc). (Beverly, MA, USA, http://www.cellsignal.com); biotinylated secondary antibody, 0.1–2 μg ml−1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. or Sigma), along with a half-standard dilution of an avidin–biotin–HRP complex (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA). Blots were developed in Supersignal West Pico Chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) and exposed on Kodak X-AR film (Sigma). Blots were then stripped (Immunopure IgG Elution Buffer, Pierce), and re-probed for actin or another marker.

Immunoblot signal was quantified by scanning densitometry (Un-Scan-It Automated Digitizing System Software, Silk Scientific Corp., Orem, UT, USA), using the total pixel density. Relative expression of each protein is presented as the densitometry units, or calculated as the ratio of signal density to actin density, or compared to untreated controls.

Immunofluorescence, immunohistochemistry, and detection of actin filament disruption

Depolymerisation of the actin cytoskeleton was determined according to the method described by several groups (Arthur and Burridge, 2001; Hirshman et al, 2001, 2005; Barros and Marshall, 2005). Cells on coverslips were treated as indicated, fixed in 3.7% methanol-free formaldehyde (in PBS) for 15 min, followed by permeabilisation in 0.5% Triton X-100 (T-X-100) in PBS for 5 min, and blocked in 1% BSA in 0.1% T-X-100/PBS for 15 min. Cells were then labelled with 1 U FITC-labeled phalloidin (1 μg ml−1) (Sigma), or labelled with both FITC-phalloidin and AlexaFluor594-DNase I (AF-DNase I) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) (10 μg ml−1) in 1% BSA/PBS for 20 min at room temperature in the dark.

Labelling of both F-actin (FITC-phalloidin) and G-actin (AF-DNase I) together corrects for differences in cell size or number per image, and thus aids in the quantification of changes in the polymerised actin fibres (Chan et al, 1998; Hirshman et al, 2001). Isoproterenol, which measurably depolymerised the actin cytoskeleton after 1 min (2 and 20 μM) (MDA-MB-231), was the depolymerisation control. Multiple views containing >20 cells per × 400 microscopic field were captured at room temperature with Microfire software (Olympus America, Center Valley, PA, USA) with the exposure time, image-intensity gain, and enhancement held constant throughout to minimise intra- and inter-experimental variation. For each actin form, the number of pixels of a given fluorescence intensity was determined using Photoshop software (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA) at intensity values for AF-DNase I, 108±11; FITC-phalloidin, 159±10; non-cellular background, 7±4 (DNase I) or 15±4 (phalloidin) (Chan et al, 1998; Hirshman et al, 2001; Papadopoulou et al, 2007).

Separate samples were permeabilised, blocked, and stained with antibodies (e.g., p-ERK1/2) at a concentration of 1 μg ml−1. Primary antibody binding was detected by HRP-, FITC-, or PE-labeled secondary antibodies. The location of phosphorylated ERK (pERK) was determined for nuclear staining by counting cells with darkly stained nuclei in six to ten × 400 microscope fields at the wound edges vs total number of cells (average number of cells per treatment: 406±11). Blue counterstained nuclei were considered negative. Nuclei with intermediate staining were counted, did not vary substantially between samples, and so are not included in the analysis. Cells were considered positive for pERK in the periphery if 40% of the cellular border was moderately to heavily positive.

For both bright field and fluorescent detection, mounted coverslips were examined at × 100 and × 400 with an Olympus BH-2 microscope (Olympus × 10 objective lens numerical aperture (NA) 0.30 or × 40 objective, NA 0.70), and captured digitally with an Olympus U-PMTVC camera using Microfire software (Olympus America).

Statistics

Values are expressed as the mean±s.d. or s.e.m. to summarise results. One-way analysis of variance or Student's t-test was used to determine the P-values. P⩽0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Immediate migration response is independent of de novo mRNA or protein synthesis

We reported previously that MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells incubated with exogenous PlGF at a concentration of 1 nM attained significantly (analysis of variance) increased invasive potential (transwell) and motility (wound). MDA-MB-231 showed consistent and significantly increased motility of 1.5- to 2-fold within 3 h after ‘wounding’ the cell monolayer. On the other hand, invasion was measurable at a later time point (20 h) for MDA-MB-231, and the two other model cell lines, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-468. Similar to MDA-MB-231, MCF-7 responded to PlGF with increased invasiveness in 24 h, but MDA-MB-468 was unresponsive at all time points (Taylor and Goldenberg, 2007). As the purpose of this study was to document the immediate effect of PlGF on kinase activation within 1–3 h of exposure, spontaneous motility assays (wound) with MDA-MB-231 were used because of the rapid and measurable kinetics of PlGF-stimulated migration, and because this cell line is tumourigenic and metastatic in mice. Similar to 30–60% of primary breast cancers, MDA-MB-231 also expresses the PlGF receptor, Flt-1. In addition, it expresses NRP-1, an alternative PlGF receptor that is expressed by normal breast (Bachelder et al, 2002; Taylor and Goldenberg, 2007).

The rapid response of MDA-MB-231 to PlGF suggested independence from de novo transcription or translation. This was tested by simultaneous addition of ActD (10 μg ml−1), or CHX (3 μg ml−1) and PlGF to MDA-MB-231 motility assays. Neither treatment significantly inhibited PlGF-stimulated migration (1.3-fold ActD and 1.4-fold CHX) when compared with treatment with ActD or CHX alone (Table 1). These results suggest that because de novo mRNA and protein synthesis has minimal effects on the PlGF-mediated motility observed within 3 h of stimulation, activated intracellular kinases may mediate motility.

Table 1. PlGF-stimulated cellular motility is independent of de novo mRNA and protein synthesis, and inhibition of MEK/ERK pathway prevents PlGF-stimulated migration.

| Treatment | Average number of migrating cells per × 100 field±s.d. |

|---|---|

| Untreated | 4.3±2.5 |

| PlGF (1 nM) | 7.4±2.8* |

| PD98059 (50 μM) | 4.0±2.3 |

| PD98059+PlGF | 3.7±3.2 |

| LY294002 (2 μM) | 7.5±3.3* |

| LY294002+PlGF | 7.6±2.6* |

| Untreated | 8.5±3.9 |

| PlGF (1 nM) | 11.2±4.5* |

| Actinomycin D (10 μg ml−1) | 7.5±4.0 |

| Actinomycin D+PlGF | 9.5±4.1* |

| Cycloheximide (3 μg ml−1) | 7.1±4.8 |

| Cycloheximide+PlGF | 9.9±5.3* |

Abbreviations: ERK=extracellular-regulated kinase; MEK=mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; PlGF=placental growth factor.

Five to ten × 100 fields on duplicate coverslips were evaluated for migrating cells by two researchers. Results were averaged and the s.d. was determined. The 3-h time point from two to five separate experiments is shown. *P<0.02 compared with control (PlGF vs untreated; actinomycin D+PlGF vs actinomycin D; cycloheximide+PlGF vs cycloheximide; LY294002 or LY294002+PlGF vs untreated).

Intracellular signalling: pERK and the PI3K pathways

Cellular movement entails changes in the cytoskeleton, which can be mediated through activation of a number of intracellular pathways, several of which may co-operate (Tsuganezawa et al, 2002). Common targets of activated RTKs, which include the PlGF receptor Flt-1, are the ERKs and PI3K.

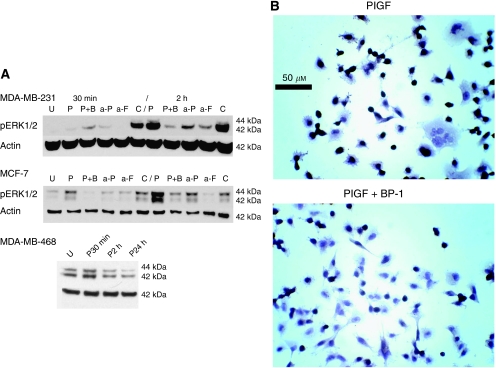

Activation (phosphorylation) of the ERK1/2 kinases was assessed by immunoblot, and it was found that PlGF mediates a 2- to 12.7-fold increase in phosphorylated ERK1/2 (pERK) (activated) in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 (Figure 1A shows representative immunoblots). On the other hand, MDA-MB-468 displayed decreased pERK after 1 h (Figure 1A). The ERK1/2 kinases are the sole substrates of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MAPKK or MEK); therefore, the MEK-specific inhibitor, PD98059 (PD98), was used to distinguish the contribution of the ERK1/2 from other ERK kinases, and the p38MAPKs, which are not substrates of MEK. PD98 (50 μM) treatment ablated ERK phosphorylation when used alone or in the presence of PlGF (not shown, MDA-MB-231). PD98 also inhibited PlGF-stimulated migration of MDA-MB-231, as shown in Table 1. These results suggest a relationship between PlGF, increased motility, and the activity of the MEK/ERK1/2 pathway.

Figure 1.

Activation of the extracellular-regulated kinases (ERKs) by PlGF, and inhibition by BP-1 and antibody treatment. (A) Representative blots of cell lines treated as shown. Placental growth factor (PlGF) (1 nM) (P); BP-1 (1 μM) (B); anti-PlGF (a-P), or anti-Flt-1 (a-F), or C (irrelevant antibody), 1 μg ml−1. MDA-MB-468: U, untreated; P30 min, PlGF treatment at 30-min time point; P2 h, PlGF treatment at 2-h time point; P24 h, PlGF at 24-h time point. MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 actin controls are from the same blot; MCF-7 actin is from a separate, identical blot. (B) BP-1 depletes nuclear phosphorylated ERK (pERK) in PlGF-treated cells. Micrographs of immunohistochemical staining of pERK in MDA-MB-231 cells. Treatments are shown. Original magnification × 400, bar 50 μm.

The PlGF cell surface receptors, Flt-1, and the glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked co-receptor, NRP-1, are differentially expressed in normal breast tissue vs breast cancer. Soluble Flt-1, anti-PlGF antibody, and the Flt-1-antagonising peptide, BP-1, inhibited PlGF-stimulated cellular movement (Taylor and Goldenberg, 2007). These findings, taken together with the ablation of cellular motility by ERK1/2 inhibition (PD98) shown in Table 1, suggest that ERK1/2 and Flt-1 participate in PlGF-driven breast cancer cell movement.

The specificity of ERK activation by PlGF was further demonstrated when lysates from anti-PlGF or anti-Flt-1 antibody-treated cells were probed for pERK by western blot analysis. Addition of either antibody inhibited ERK phosphorylation (Figure 1A), a result that further demonstrates the specificity of the PlGF-Flt-1-mediated phosphorylation of ERK.

Active ERK kinases translocate to the nucleus and to the cytoskeleton. As determined by immunohistochemistry, intranuclear pERK was abundant, even in untreated MDA-MB-231 cells, with 72–80% of nuclei staining heavily. The PlGF treatment consistently increased the percentage of positive nuclei to 85±2% (406±11 cells per treatment evaluated). Treatment of cells with the BP-1 peptide, combined with PlGF, significantly decreased the frequency of positive nuclei to 62±5% (P<0.001) (Figure 1B). The pERK was also found in a dotted pattern at the cellular periphery (see Materials and Methods) and in the perinuclear region. The frequency of cells staining for peripheral pERK differed among treatment groups with PlGF almost doubling that of untreated cells (23±4 vs 12±3%, respectively, P<0.001 PlGF vs untreated). Treatment with BP-1 prevented the PlGF-mediated increase in peripheral pERK (7±3% for PlGF+BP-1 (P<0.001 vs PlGF-only)).

PlGF did not detectably direct another ERK kinase, ERK5, which also enhances cellular motility through disruption of cellular adhesion and disassembly of the actin cytoskeleton to the cellular periphery (Barros and Marshall, 2005) (not shown).

The ERK and the PI3K pathways may co-operate or oppose each other in particular cellular responses, including motility. To investigate the participation of PI3K pathways in PlGF-mediated motility, MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with inhibitors of the PI3K pathway.

Unlike the results obtained for ERK, motility was not inhibited by the non-specific PI3K inhibitor, wortmannin (5 nM) (not shown), or with the more specific PI3K inhibitor, LY294002 (2 μM, MDA-MB-231) (Table 1). Phosphorylated Akt, a common downstream substrate of PI3K, was not increased or decreased by addition of PlGF (MCF-7, not shown). Therefore, this pathway was not detectably activated by PlGF, and most likely is not involved in PlGF-stimulated migration of breast cancer cells.

IF expression by breast cancer cell lines

As PlGF-stimulated cellular motility and ERK activation were prevented by BP-1 and anti-Flt-1 antibody, it was concluded that PlGF may exert its effect on the cytoskeleton at least partially through pERK. ERK kinases interact with both the actin and the IFs of the cytoskeleton, including vimentin. Changes in IF type and quantity are associated with breast cancer aggressiveness and invasion. Normal breast epithelium does not express the mesenchymal IF protein, vimentin. Phosphorylated ERKs1/2 bind vimentin, stabilising ERK in its phosphorylated form, which in turn leads to rearrangement of the vimentin network (Perlson et al, 2006; Henson and Vincent, 2008).

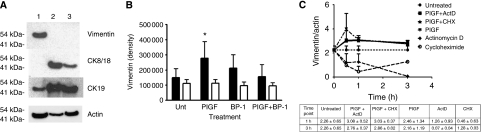

To investigate the relationship of ERK1/2, PlGF, and IF expression in cellular motility, the relative amounts of vimentin and the CKs 8/18 and 19 were first assessed for three breast cancer cell lines (MDA-MB-231, -468, and MCF-7). Results are shown in Figure 2A. MDA-MB-231 expresses abundant vimentin, but it was undetectable in MDA-MB-468 and MCF-7 even after long exposures (Figure 2A). The immunoblots showed that MDA-MB-231, MCF-7, and MDA-MB-468 breast cancer cells all express CK19, but the latter two lines are also high expressers of CK8/18 (Figure 2A). The MCF-7 CK8/18 to actin ratio was slightly increased over the CK19 ratio, but both were abundantly expressed (3.9±0.6 vs 2.9±0.32). On the other hand, MDA-MB-231, an aggressive cell line that forms metastases from subcutaneous xenograft tumours, expressed six-fold greater CK19 than CK8/18 (Figure 2A). MDA-MB-468, also tumourigenic but non-metastasising, expressed high levels of the CKs but no vimentin.

Figure 2.

Expression of cytokeratins (CKs) and vimentin by MDA-MB-231, MCF-7, and MDA-MB-468; and stabilisation of vimentin expression by PlGF. (A) Immunoblots for vimentin, CKs 8/18 and 19 in MDA-MB-231 (lane 1), MCF-7 (lane 2), and MDA-MB-468 (lane 3). Blots were loaded with 10 μg protein per lane, and probed simultaneously for each factor. Actin is from a separate, identical blot. (B) Vimentin expression at 3 h after addition of PlGF (1 nM) or peptide BP-1 (1 μM). Black bars represent vimentin±s.e.m.; white bars, actin±s.e.m. (immunoblot densitometry readings). Vimentin expression increased 1.59±0.33-fold with PlGF treatment, and by 0.97±0.09-fold for PlGF+BP-1 (vs Unt (untreated)±s.d.). Actin variation was 1.04±0.13. *P<0.02 (analysis of variance): n=3 experiments. (C) Vimentin expression following pre-treatment with PlGF before adding actinomycin D (ActD) or CHX vs single-agent treatment (n=2 experiments, each treatment). The table below shows the ratios at 1 and 3 h.

Alterations in vimentin expression vs PlGF

To assess whether PlGF would alter vimentin expression, MDA-MB-231 was stimulated with PlGF for 1–3 h, and the relative amount of vimentin was determined by immunoblot. Increased vimentin expression of 1.9- to 4-fold compared with the untreated control was detected at the 1-h time point (Figure 2B, P<0.02). Addition of the peptide BP-1 to the PlGF-containing cultures resulted in a reversal of the PlGF-stimulated increase at 3 h (1.07 of untreated control) (Figure 2B).

To investigate this early effect of PlGF on vimentin expression mediated by de novo mRNA or protein synthesis, MDA-MB-231 cells were incubated with sub-toxic doses of ActD and CHX (1 and 3 μg ml−1, respectively) to inhibit mRNA and protein synthesis, respectively. Lysates were assessed for vimentin at 30 min, 1 h, and 3 h. In these experiments incubation of MDA-MB-231 with ActD resulted in declining vimentin over 3 h. The CHX treatment, on the other hand, caused a 50% decrease in vimentin at 1 h, but after 1 h the amount of vimentin stabilised and did not decline significantly thereafter. As shown on the graph in Figure 2C, it appears that both de novo mRNA transcription and translation are involved in vimentin production, but in the absence of translation, a mechanism for stabilisation of vimentin is activated that prevents or slows its loss.

In further experiments investigating the influence of PlGF on vimentin expression, MDA-MB-231 cells were pre-incubated with PlGF for 15 min before addition of ActD or CHX. This resulted in persistence of vimentin, even in the presence of ActD or CHX (Figure 2C). Thus, it is probable that PlGF activates mechanisms that promote the stability of vimentin independently of mRNA or protein synthesis.

PlGF mediates stability of specific IF CKs

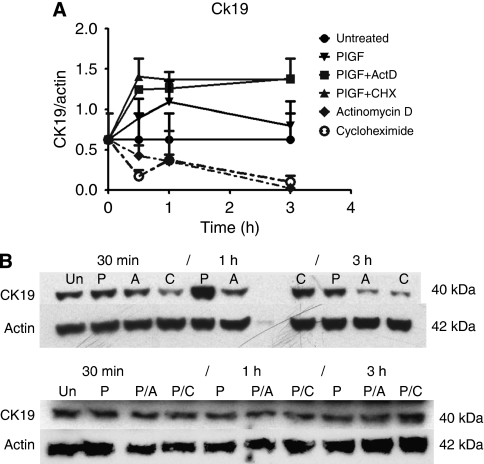

Just as expression of mesenchymal vimentin is associated with aggressive breast cancer, changes in the pattern of CK expression are also considered indicative of breast cancer aggressiveness and motility, and co-expression of CK19 and vimentin is indicative of poor clinical outcome (Brotherick et al, 1998; Buhler and Schaller, 2005). The effect of PlGF on CK expression was assayed, and it was found that PlGF did not influence the abundance of CK8/18 (not shown). However, after incubation for 1 h with PlGF, CK19 increased 1.5-fold over untreated controls (P=0.05) (MDA-MB-231, four experiments). Treatment with BP-1 measurably attenuated CK19 expression in PlGF-treated samples by 2 h (average 0.58±0.32 of PlGF-only, two experiments), suggesting that autocrine PlGF signalling, which was blocked by the peptide, may have a role in the maintenance of CK19 expression. A control peptide did not affect CK19 expression (not shown).

The antagonistic effect of BP-1 on CK19 expression could be due to interruption of PlGF-Flt-1-mediated stabilisation of CK19 protein. To further investigate the influence of PlGF on the stability of CK19, cells were treated with either ActD or CHX at the sub-toxic doses described above. Cumulative results are shown in Figure 3A and Figure 3B shows representative blots. In the CHX-treated samples, CK19 diminished to 50% of initial levels by 30 min, remained at that level at the 1-h time point, after which it declined to very low levels by 3 h (as shown in Figure 3A). The ActD treatment also brought about a steady decrease in CK19 (Figure 3A). These results suggest that CK19 expression is regulated, in part, by transcription and translation.

Figure 3.

Stabilisation of cytokeratin (CK) expression by PlGF, with disruption by BP-1. (A) CK19 expression in MDA-MB-231 pre-treated with PlGF before adding actinomycin D (ActD) or CHX vs either inhibitor alone (n=2 experiments each treatment). (B) Upper panel: representative blot showing MDA-MB-231 CK19 expression following treatment with ActD (1 μg ml−1) or CHX (3 μg ml−1) alone. (30-min, 1-, and 3-h time points are shown: Un, untreated; P, PlGF-only; A, ActD; C, CHX at each time point.) Lower panel: representative blot showing CK19 expression when cells were pre-treated with PlGF 15 min before adding ActD or CHX. (30 min, 1 or 3 h after inhibitor was added: Un, untreated; P, PlGF-only; P/A, PlGF pre-treated, followed by ActD; P/C, PlGF pre-treated, followed by CHX for the times indicated.)

In separate experiments, MDA-MB-231 was pre-treated with PlGF for 15 min before adding ActD or CHX. Pre-treatment prevented the decrease in CK19 seen with single-agent treatment, such that the CK19 levels remained higher than the untreated controls (Figure 3A). Thus, the effect of PlGF on CK19 seems to be independent of de novo transcription or translation, and may be related to the rate of degradation of CK19.

PlGF stimulates rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton

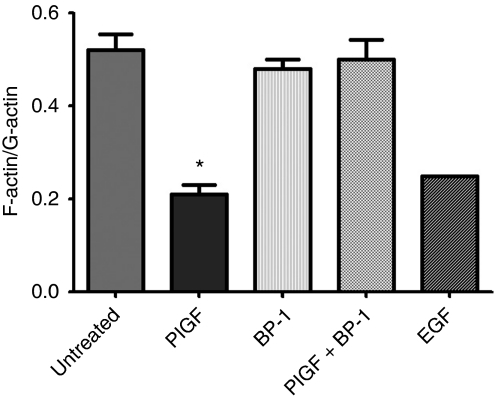

The microscopic appearance of PlGF-treated breast cancer cells stained for F-actin differed from untreated cells by the appearance of increased actin-rich punctate structures on the edges of the cells (not shown). This observation may be due to the re-organisation of the actin cytoskeleton as the cell becomes motile, and which has been documented for other growth factors and carcinomas, for example, epidermal growth factor (Chan et al, 1998; Harper et al, 2007). The state of the actin cytoskeleton was quantified by determination of the F-actin (filamentous, polymerised) to G-actin (non-polymerised) ratio using phalloidin and DNase I, which stain F-actin and G-actin, respectively, as described in Materials and methods. The ratio of F-actin to G-actin decreased to less than half of untreated controls, indicating actin cytoskeleton rearrangement on PlGF treatment (Figure 4). In contrast to the effect of PlGF alone, addition of the inhibitory peptide, BP-1, to PlGF-treated cultures prevented lowering of the F-actin to G-actin ratio associated with PlGF.

Figure 4.

Placental growth factor (PlGF) induces rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton, and reversal by BP-1. The ratio of F-actin to G-actin changes with PlGF or epidermal growth factor (EGF) treatment (1 nM). Results are shown as average of ratios±s.d. *P<0.05 (analysis of variance): n=3 experiments (epidermal growth factor (EGF), one experiment).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to analyse the early events triggered by PlGF in the responsive breast cancer cell, and elucidate how the peptide, BP-1, works in inhibiting cellular motility in vitro, and in preventing metastasis formation in xenograft models of breast cancer (Taylor and Goldenberg, 2007). To carry out this, the effect of inhibitors on cellular motility, a pro-metastatic behaviour, was analysed. The results show that PlGF-driven breast tumour cell motility include the activation of ERK1/2 kinases, stabilisation of IF proteins, and re-organisation of the actin cytoskeleton. The PlGF specificity of these results was shown by their ablation with anti-Flt-1 antibody or BP-1.

The ERKs are activated by a number of different factors, including c-Src, the G-protein-linked kinase Raf, and MEK (Barros and Marshall, 2005; Chen et al, 2006). Increased pERK stimulated by PlGF was reversed by treatment with BP-1 or a MEK-specific inhibitor. Ablation of MEK not only prevented pERK formation, but it also prevented PlGF-stimulated cellular migration. Thus, as the only known substrates of MEK are the ERK1/2 kinases, it can be concluded that PlGF-stimulated motility depends on activation of the ERKs by MEK. This does not eliminate other potential ERK activators, and preliminary data (not shown) suggest that Raf participates in PlGF effects as well.

While this study was in progress, another report investigated PlGF-mediated migration of leukaemia cells (Casalou et al, 2007). Our findings are in agreement with this report, in that we found no evidence of Akt involvement in PlGF-mediated breast cancer cell movement. However, unlike Casalou et al, little evidence of p38 MAPK involvement in PlGF-mediated breast cancer cell movement was found because movement was abrogated by inhibition of MEK, which does not activate p38 MAPK. Therefore, it is unlikely that p38 MAPK contributes substantially to the movement of breast cancer cells in the presence of PlGF. Another point of difference was the finding that VEGF had little to no effect on breast cancer cell migration (Taylor and Goldenberg, 2007). This contrasts with the results obtained by Casalou et al for leukaemia cells. These differences may be due to different effects of VEGF and PlGF on cancers of epithelial origin, such as breast cancer, in contrast to cancers of hematopoietic origin, where the function of VEGF and PlGF may be redundant.

When activated, the ERK kinases localise to the nucleus or to focal adhesions where they are associated with motility by interaction with cytoskeletal substrates, including IF proteins, the actin cytoskeleton, and myosin light chain kinase (Zheng and Guan, 1994; Schlaepfer et al, 1998; Arthur and Burridge, 2001; Pawlak and Helfman, 2002; Yin et al, 2005). This study presented evidence that PlGF promoted translocation of pERK1/2 to the cellular periphery, and so there it may function to increase motility.

Although CK18 and CK19 are expressed by normal breast epithelium, their expression is often dysregulated in breast cancers (Ferrero et al, 1990; Boecker et al, 2002). Aggressive MDA-MB-231 displays a pattern of predominant CK19 with little or no CK18, whereas this is not the case for MCF-7 or MDA-MB-468, which both produce abundant CK18 (and CK19). Human breast cancers expressing high levels of CK18 (without vimentin), similar to MCF-7 or MDA-MB-468, are less likely to recur. In addition, MDA-MB-231 transfected with CK18 obtains an epithelial phenotype, reduces aggressiveness in tumour growth, and loses vimentin expression (Buhler and Schaller, 2005). On the basis of the results of this study, in which CK19 and vimentin expression rose on PlGF stimulation, it is possible that RTK activation, such as Flt-1, stimulates co-expression of CK19 and vimentin.

Likewise, vimentin, a mesenchymal IF protein not expressed by normal breast cells, is associated with poorer clinical outcomes and resistance to apoptosis and drugs (Yuan et al, 1997; Stathopoulou et al, 2002; Willipinski-Stapelfeldt et al, 2005), as well as increased metastasis and invasion (Hartig et al, 1998; Tolstonog et al, 2001; Singh et al, 2003; Hu et al, 2004; Schoumacher et al, 2010). McInroy and Maatta (2007) showed that the aggressiveness of MDA-MB-231 depends on vimentin expression, because its ablation impaired migration and invasion. Our data show that disrupting PlGF or Flt-1 signalling with antibody or BP-1 depressed vimentin, CK19 expression, and motility in MDA-MB-231. Thus, in the case of MDA-MB-231 and perhaps other breast cancers, PlGF, or other abnormally expressed growth factors, may maintain the high CK19 and vimentin levels necessary for motility and invasion. The results also suggest that PlGF does this by stabilising the proteins independently of ongoing transcription and translation, and that, because of their concurrent increase, both factors are controlled by intersecting or common pathways, some of which are regulated by PlGF.

Flt-1 has been considered a cell surface-bound receptor (Wang et al, 2000; Liu et al, 2005); however, nuclear expression that delivered intracrine signals promoting breast cancer cell survival through VEGF was reported by Lee et al (2007). Our previous report indicated that exogenous PlGF, rather than VEGF, promoted cellular movement, and that soluble Flt-1 and anti-PlGF antibody blocked migration. In this study, we show that exogenous anti-Flt-1 attenuates PlGF-driven phosphorylation of ERK also. Except for the non-significant increase in nuclear translocation of pERK with PlGF treatment, there is no indication that the PlGF interactions leading to activation of ERK reported herein occurred in the nucleus. In almost all cases, ERKs are activated by factors associated with the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane and cell surface receptors. Therefore, it can be concluded that PlGF stimulates motility by interaction with cell surface Flt-1, rather than nuclear Flt-1. The intracrine and cell surface functions of Flt-1, one conferring survival and the other motility through PlGF, are not mutually exclusive, and both promote metastasis.

In summary, this study describes for the first time, the effect of the growth factor, PlGF, on the activation of key kinases, which participate in increased cellular motility, a behaviour associated with metastasis rather than tumour growth and tumour cell proliferation. In other human cancers, ectopically expressed growth factors may also drive metastasis by mechanisms similar to those shown here for PlGF. For the breast cancer cell lines studied, the specificity of the kinase activation and increased migration was verified with antibody against both PlGF and Flt-1. The peptide, BP-1, abrogates PlGF-driven cellular motility and several of the PlGF-mediated changes in intracellular signalling, and this may, in part, explain its anti-tumour activity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr David V Gold for helpful comments on this paper. This work was supported, in part, by the New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services Grant 07-1824-FS-N-0 (DMG).

References

- Arthur WT, Burridge K (2001) RhoA inactivation by p190RhoGAP regulates cell spreading and migration by promoting membrane protrusion and polarity. Mol Biol Cell 12: 2711–2720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachelder RE, Wendt MA, Mercurio AM (2002) Vascular endothelial growth factor promotes breast carcinoma invasion in an autocrine manner by regulating the chemokine receptor CXCR4. Cancer Res 62: 7203–7206 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros JC, Marshall CJ (2005) Activation of either ERK1/2 or ERK MAP kinase pathways can lead to disruption of the actin cytoskeleton. J Cell Sci 118: 1663–1671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boecker W, Moll R, Dervan P, Buerger H, Poremba C, Diallo RI, Herbst H, Schmidt A, Lerch MM, Buchwalow IB (2002) Usual ductal hyperplasia of the breast is a committed stem (progenitor) cell lesion distinct from atypical ductal hyperplasia and ductal carcinoma in situ. J Pathol 198: 458–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotherick I, Robson CN, Browell DA, Shenfine J, White MD, Cunliffe WJ, Shenton BK, Egan M, Webb LA, Lunt LG, Young JR, Higgs MJ (1998) Cytokeratin expression in breast cancer: phenotypic changes associated with disease progression. Cytometry 32: 301–308 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhler H, Schaller G (2005) Transfection of keratin 18 gene in human breast cancer cells causes induction of adhesion proteins and dramatic regression of malignancy in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cancer Res 3: 365–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casalou C, Fragoso R, Nunes JF, Dias S (2007) VEGF/PlGF induces leukemia cell migration via P38/ERK1/2 kinase pathway, resulting in Rho GTPases activation and caveolae formation. Leukemia 21: 590–1594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan AY, Raft S, Bailly M, Wyckoff JB, Segall JE, Condeelis JS (1998) EGF stimulates an increase in actin nucleation and filament number at the leading edge of the lamellipod in mammary adenocarcinoma cells. J Cell Sci 111: 199–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CN, Hsieh FJ, Cheng YM, Cheng WF, Su YN, Chang KJ, Lee PH (2004) The significance of placenta growth factor in angiogenesis and clinical outcome of human gastric cancer. Cancer Lett 213: 73–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Necela BM, Su W, Yanagisawa M, Anastasiadis PZ, Fields AP, Thompson EA (2006) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ promotes epithelial to mesenchymal transformation by rho GTPase-dependent activation of ERK1/2. J Biol Chem 281: 24575–24587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu YW, Seftor EA, Romer LH, Hendrix MJ (1996) Experimental coexpression of vimentin and keratin intermediate filaments in human melanoma cells augments motility. Am J Pathol 148: 63–69 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePrimo SE, Bello CL, Smeraglia J, Baum CM, Spinella D, Rini BI, Michaelson MD, Motzer RJ (2007) Circulating protein biomarkers of pharmacodynamic activity of sunitinib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: modulation of VEGF and VEGF-related proteins. J Transl Med 5: 32–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domagala W, Lasota J, Bartkowiak J, Weber K, Osborn M (1990) Vimentin is preferentially expressed in human breast carcinomas with low estrogen receptor and high Ki-67 growth fraction. Am J Pathol 136: 219–227 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckes B, Dogic D, Colucci-Guyon E, Wang N, Maniotis A, Ingber D, Merckling A, Langa F, Aumailley M, Delouvee A, Koteliansky V, Babinet C, Krieg T (1998) Impaired mechanical stability, migration and contractile capacity in vimentin- deficient fibroblasts. J Cell Sci 111: 1897–1907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escudero-Esparza A, Martin TA, Douglas-Jones A, Mansel RE, Jiang WG (2010) PGF isoforms, PlGF-1 and PGF-2, and the PGF receptor, neuropilin, in human breast cancer: prognostic significance. Oncol Rep 23: 537–544 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrero M, Spyratos F, Le Doussal V, Desplaces A, Rouesse J (1990) Flow cytometric analysis of DNA content and keratins by using CK7, CK8, CK18, CK19, and KL1 monoclonal antibodies in benign and malignant human breast tumors. Cytometry 11: 716–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer C, Jonckx B, Mazzone M, Zacchigna S, Loges S, Pattarini L, Chorianopoulos E, Liesenborghs L, Koch M, De Mol M, Autiero M, Wyns S, Plaisance S, Moons L, van Rooijen N, Giacca M, Stassen JM, Dewerchin M, Collen D, Carmeliet P (2007) Anti-PlGF inhibits growth of VEGFR-inhibitor-resistant tumors without affecting healthy vessels. Cell 131: 463–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer C, Mazzone M, Jonckx B, Carmeliet P (2008) Flt1 and its ligands VEGFB and PlGF: drug targets for anti-angiogenic therapy? Nat Rev Cancer 8: 942–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper L, Kashiwagi Y, Pusey CD, Hendry BM, Domin J (2007) Platelet-derived growth factor reorganizes the actin cytoskeleton through 3-phosphoinositide-dependent and 3-phosphoinositide-independent mechanisms in human mesangial cells. Nephron Physiol 107: 45–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartig R, Shoeman RL, Janetzko A, Tolstonog G, Traub P (1998) DNA-mediated transport of the intermediate filament protein vimentin into the nucleus of cultured cells. J Cell Sci 111: 3573–3584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfand BT, Chang L, Goldman RD (2004) Intermediate filaments are dynamic and motile elements of cellular architecture. J Cell Sci 117: 133–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix MJC, Seftor EA, Seftor REB, Trevor KT (1997) Experimental co-expression of vimentin and keratin intermediate filaments in human breast cancer cells results in phenotypic interconversion and increased invasive behavior. Am J Pathol 150: 483–495 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henson FMD, Vincent TA (2008) Alterations in the vimentin cytoskeleton in response to single impact load in an in vitro model of cartilage damage in the rat. BMC Musculoskel Disord 9: 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshman CA, Zhu D, Panettieri RA, Emala CW (2001) Actin depolymerization via the β- adrenoceptor in airway smooth muscle cells. A novel PKA-independent pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 281: C1468–C1476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshman CA, Zhu D, Pertel T, Panettieri RA, Emala CW (2005) Isoproterenol induces actin depolymerization in human airway smooth muscle cells via activation of an Src kinase and GS. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 288: L924–L931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho M-C, Chen C-N, Lee H, Hsieh F-J, Shun C-T, Chang C-L, Lai Y-T, Lee P-H (2007) Placenta growth factor not vascular endothelial growth factor A or C can predict the early recurrence after radical resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett 250: 237–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Lau SH, Tzang CH, Wen JM, Wang W, Xie D, Huang M, Wang Y, Wu MC, Huang JF, Zeng WF, Sham JS, Yang M, Guam XY (2004) Association of vimentin overexpression and hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis. Oncogene 23: 298–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilic D, Furuta Y, Kanazawa S, Takeda N, Sobue K, Nakatsuji N, Nomura S, Fujimoto J, Okada M, Yamamoto T (1995) Reduced cell motility and enhanced focal adhesion contact formation in cells from FAK-deficient mice. Nature 377: 539–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagawa S, Matsuo A, Yagi Y, Ikematsu K, Tsuda R, Nakasono I (2009) The time-course analysis of gene expression during wound healing in mouse skin. Leg Med (Tokyo) 11: 70–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T-H, Seng S, Sekine M, Hinton C, Fu Y, Avraham HK, Avraham S (2007) Vascular endothelial growth factor mediates intracrine survival in human breast carcinoma cells through internally expressed VEGFR1/FLT1. PLoS Med 4: 1101–1116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Sharpe EE, Maupin AB, Teleron AA, Pyle AL, Carmeliet P, Young PP (2006) VEGF and PlGF promote adult vasculogenesis by enhancing EPC recruitment and vessel formation at the site of tumor neovascularization. FASEB J 20: E664–E676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Poon RT, Li Q, Kok TW, Lau C, Fan ST (2005) Both antiangiogenesis- and angiogenesis-independent effects are responsible for hepatocellular carcinoma growth arrest by tyrosine kinase inhibitor PTK787/ZK222584. Cancer Res 65: 3691–3699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes C, Coenegrachts L, Stockmans I, Daci E, Luttun A, Petryk A, Gopalakrishnan R, Moermans K, Smets N, Verfaillie CM, Carmeliet P, Bouillon R, Bouillon R, Carmeliet G (2006) Placental growth factor mediates mesenchymal cell development, cartilage turnover, and bone remodeling during fracture repair. J Clin Invest 116: 1230–1242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInroy L, Maatta A (2007) Down-regulation of vimentin expression inhibits carcinoma cell migration and adhesion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 360: 109–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra SK, Hanson DA, Schlaepfer DD (2005) Focal adhesion kinase: in command and control of cell motility. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6: 56–68, (review) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oriolo AS, Wald FA, Ramsauer VP, Salas PJ (2007) Intermediate filaments: a role in epithelial polarity (review). Exp Cell Res (NIH Public Access) 313: 2255–2264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulou MV, Bloomer WD, Taylor AP, Hernandez M, Blumenthal RD, Hollingshead MG (2007) Advantage of combining NLCQ-1 (NSC 709257) with radiation in treatment of human head and neck xenografts. Radiat Res 168: 65–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr C, Watkins G, Boulton M, Cai J, Jiang WG (2005) Placenta growth factor is over-expressed and has prognostic value in human breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 41: 2819–2827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak G, Helfman DM (2002) MEK mediates v-Src-induced disruption of the actin cytoskeleton via inactivation of the Rho-ROCK-LIM kinase pathway. J Biol Chem 277: 26927–26933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlson E, Michaelevski I, Kowalsman N, Ben-Yaakov K, Shaked M, Seger R, Eisenstein M, Fainzilber M (2006) Vimentin binding to phosphorylated ERK sterically hinders enzymatic dephosphorylation of the kinase. J Mol Biol 264: 938–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronnstrand L, Heldin CH (2001) Mechanisms of platelet-derived growth factor-induced chemotaxis. Int J Cancer 91: 757–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaepfer DD, Jones KC, Hunter T (1998) Multiple Grb2-mediated integrin-stimulated signaling pathways to ERK2/Mitogen-activated kinase: summation of both c-Src- and focal adhesion kinase-initiated tyrosine phosphorylation events. Mol Cell Biol 18: 2571–2585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoumacher M, Goldman RD, Louvard D, Vignjevic DM (2010) Actin, microtubules, and vimentin intermediate filaments cooperate for elongation of invadopodia. J Cell Biol 189: 541–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Sadacharan S, Su S, Belldegrun A, Persad S, Singh G (2003) Overexpression of vimentin: role in the invasive phenotype in an androgen-independent model of prostate cancer. Cancer Res 63: 2306–2311 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starzec A, Vassy R, Martin A, Lecouvey M, Di Benedetto M, Crepin M, Perret GY (2006) Antiangiogenic and antitumor activities of peptide inhibiting the vascular endothelial growth factor binding to neuropilin-1. Life Sci 79: 2370–2381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stathopoulou A, Vlachonikolis I, Mavroudis D, Perraki M, Kouroussis C, Apostoloki S, Malamos N, Kakolyris S, Kotsakis A, Xenidis N, Reppa D, Georgoulias V (2002) Molecular detection of cytokeratin-19-positive cells in the peripheral blood of patients with operable breast cancer: evaluation of their prognostic significance. J Clin Oncol 20: 3404–3412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AP, Osorio L, Craig R, Ying Z, Goldenberg DM, Blumenthal RD (2002) Tumor- specific regulation of angiogenic growth factors and their receptors during recovery from cytotoxic therapy. Clin Cancer Res 8: 1213–1222 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AP, Rodriguez M, Adams K, Goldenberg DM, Blumenthal RD (2003) Altered tumor vessel maturation and proliferation in placenta growth factor-producing tumors: potential relationship to post-therapy tumor angiogenesis and recurrence. Int J Cancer 105: 158–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AP, Goldenberg DM (2007) Role of placenta growth factor (PlGF) in malignancy, and evidence that an antagonistic PlGF/Flt-1 peptide inhibits the growth and metastasis of human breast cancer xenografts. Mol Cancer Ther 6: 524–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas PA, Kirschmann DA, Cerhan JR, Folberg R, Seftor EA, Sellers TA, Hendrix MJC (1999) Association between keratin and vimentin expression, malignant phenotype, and survival in postmenopausal breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 5: 2698–2703 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolstonog GV, Shoeman RL, Traub U, Traub P (2001) Role of the intermediate filament protein vimentin in delaying senescence and in the spontaneous immortalization of mouse embryo fibroblasts. DNA Cell Biol 20: 509–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuganezawa H, Sato S, Yamaji Y, Preisig PA, Moe OW, Alpern RJ (2002) Role of c- SRC and ERK in acid-induced activation of NHE3. Kidney Inter 62: 41–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Donner DB, Warren RS (2000) Homeostatic modulation of cell surface KDR and Flt1 expression and expression of the vascular endothelial cell growth factor (VEGF) receptor mRNAs by VEGF. J Biol Chem 275: 15905–15911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei SC, Tsao PN, Yu SC, Shun CT, Tsai-Wu JJ, Wu CH, Su YN, Hsieh FJ, Wong JM (2005) Placenta growth factor expression is correlated with survival of patients with colorectal cancer. Gut 54: 666–672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willipinski-Stapelfeldt B, Riethdorf S, Assmann V, Woelfle U, Rau T, Sauter G, Heukeshoven J, Pantel K (2005) Changes in cytoskeletal protein composition indicative of an epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human micrometastatic and primary breast carcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res 11: 8006–8014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C-H, Xia W, Lee NPY, Mruk DD, Lee WM, Cheng CY (2005) Regulation of ectoplasmic specialization dynamics in the seminiferous epithelium by focal adhesion-associated proteins in testosterone-suppressed rat testes. Endocrinology 146: 1192–1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin G, Zheng Q, Yan C, Berk BC (2005) GIT1 is a scaffold for ERK1/2 activation in focal adhesions. J Biol Chem 280: 27705–27712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan CC, Huang HC, Tsai LC, Ng HT, Huang TS (1997) Cytokeratin-19 associated with apoptosis and chemosensitivity in human cervical cancer cells. Apoptosis 2: 101–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng C-F, Guan K-L (1994) Cytoplasmic localization of the mitogen-activated protein kinase activator MEK. J Biol Chem 269: 19947–19952 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]