Abstract

Background

The New World monkey (Platyrrhini) subfamily Pitheciinae is represented by the genera Pithecia, Chiropotes and Cacajao. In this work we studied the karyotypes of Pithecia irrorata (2n = 48) and Cacajao calvus rubicundus (2n = 45 in males and 2n = 46 in females) by G- and C-banding, NOR staining and chromosome painting using human and Saguinus oedipus whole chromosome probes. The karyotypes of both species were compared with each other and with Chiropotes utahicki (2n = 54) from the literature.

Results

Our results show that members of the Pitheciinae have conserved several chromosome forms found in the inferred ancestral Platyrrhini karyotype (associations of human homologous segments 3a/21, 5/7a, 2b/16b, 8a/18, 14/15a and 10a/16a). Further, the monophyly of this subfamily is supported by three chromosomal synapomorphies (2a/10b, an acrocentric 15/14 and an acrocentric human 19 homolog). In addition, each species presents several autapomorphies. From this data set we established a chromosomal phylogeny of Pitheciinae, resulting in a single most parsimonious tree.

Conclusions

In our chromosomal phylogeny, the genus Pithecia occurred in a more basal position close to the inferred ancestor of Platyrrhini, while C. c. rubicundus and C. utahicki are closely related and are linked by exclusive synapomorphies.

Background

The subfamily Pitheciinae includes the genera Pithecia Desmarest, 1804, Chiropotes and Cacajao Lesson, 1840. Pithecia comprises five species: Pithecia pithecia, Pithecia monachus, Pithecia irrorata (each two subspecies), Pithecia albicans and Pithecia aequatorialis (both monotypic) [1]. Chiropotes is represented by the two species Chiropotes albinasus (monotypic) and Chiropotes satanas (three subspecies) [2], and Cacajao by Cacajao calvus (four subspecies) and Cacajao melanocephalus (two subspecies) [3]. The geographic distribution of this subfamily is restricted to the Amazon region. Recent morphological, karyotypic and molecular data pointed to a new species for Chiropotes, C. israelita, and indicated that the subspecies Chiropotes satanas utahicki should be accepted as a full species [4]. The majority of the Pitheciinae species are listed as endangered (http://www.cites.org).

It is accepted that the Pitheciinae represent a monophyletic clade [4-7]. Several studies using morphological [5-7], molecular [8,9] and cytogenetic [10] traits suggest that Chiropotes and Cacajao are sister taxa and place Pithecia most basal within this clade. It was further suggested that the Pitheciinae are a sister group of Aotus and Callicebus [5], while more recent molecular phylogenetic analyses supported an association of Pitheciinae and Callicebus, but associate Aotus with Callitrichidae [8,11-14].

To date, cytogenetic studies of members from this subfamily are still rare. The karyotypes of C. albinasus, P. monachus, P. aequatorialis and P. albicans have not yet been described so far, while for others, for example for C. melanocephalus, only the diploid chromosome number was published [15]. Moura-Pensin et al. [10] were the first to present a broader comparative cytogenetic study, including Pithecia irrorata, Chiropotes satanas chiropotes, Chiropotes satanas utahicki and Cacajao calvus rubicundus. Cacajao shows the lowest diploid chromosome number among Pitheciinae with 2n = 46 in females and 45 in males [10,15-17]. Pithecia has 2n = 48 chromosomes [18], and Chiropotes has the highest diploid number with 2n = 54 [10,19]. Only Chiropotes utahicki and C. israelita were so far analyzed by chromosome painting using human whole chromosome probes [19]. Stanyon et al. [19] showed that Chiropotes retained all human homologous syntenic associations proposed for the ancestral Platyrrhini karyotype, but also include several derived chromosome forms that are exclusive to this genus.

With the aim to establish detailed chromosomal phylogenies of the three genera of Pitheciinae, we studied the karyotypes of the species Pithecia irrorata and Cacajao calvus rubicundus using both classic cytogenetics and chromosome painting with human and Saguinus oedipus whole chromosome probes.

Methods

Chromosome preparations were obtained from whole blood cultures of one female and two male Pithecia irrorata (PIR) individuals kept at the Parque Zoobotânico Gavião Real, Capitão Poço, Para, Brazil, of two females from the Centro Nacional de Primatas, Ananindeua, Para, Brazil, and of a male and a female Cacajao calvus rubicundus (CCR) individual kept at the Centro de Primatologia do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

G-banding, using Wright stain [20], C-banding [21] and NOR-staining [22], followed standard procedures. FISH experiments using human whole chromosome paint probes 1-22, X and Y, and S. oedipus paint probes (22 autosomes, X and Y) were performed as previously described [23-25]. While both human probes were hybridized for CCR and PIR, only PIR is queried with SOE paints. Paint probes were labeled by DOP-PCR [26] using Biotin-dUTP, Digoxigenin-dUTP (Roche) and TAMRA-dUTP (Biosystems/PE Applied). After classical staining, metaphases were photographed using a Zeiss III microscope with Kodak Imagelink HQ film. FISH/DAPI stained metaphase images were captured with a CCD camera (AxioCam MR monochrome, or Photometrics C250/A, equipped with a KAF1400 chip, respectively) coupled to a Zeiss Axiophot microscope. The images were analyzed using Adobe Photoshop software version CS3 and Corel Photo Paint 10. Chromosomes were identified by computer enhanced DAPI banding (Axiovision 3.0).

For phylogenetic analysis a binary data matrix was established, based on the presence or absence of discrete chromosomal characters obtained by comparative analysis of both chromosome painting patterns derived from human whole chromosome probes and by G-banding patterns in the Pitheciinae species included in our study and from the literature [19]. Brachyteles arachnoides [24] and Cebus apella [25] were used as outgroups. We attributed "0" (zero) value to the absence of a character (an association or a syntenic group that is conserved or changed by chromosome rearrangements) and "1" (one) value to the presence of the character. These data were subjected to maximum parsimony analysis (PAUP 4.0 software; Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony), using the exhaustive search option. The relative stability of nodes was assessed by bootstrap estimates.

Results

Classical cytogenetics

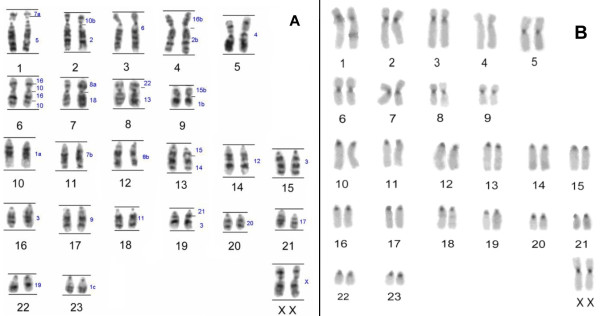

P. irrorata has 2n = 48 chromosomes, with nine metacentric or submetacentric and 14 acrocentric autosome pairs. The X chromosome is a medium sized submetacentric. The G-banded karyotype is shown in the Figure 1A. C-banding highlighted constitutive heterochromatin in the centromeres of all chromosomes and an interstitial band in the long arm of pair 18 (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

G- (A) and C-banding (B) in P. irrorata.

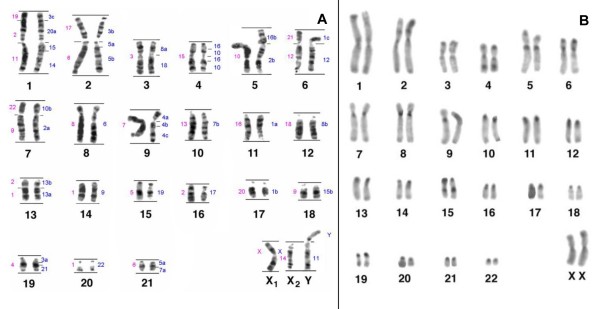

C. c. rubicundus has 2n = 45 chromosomes in males and 2n = 46 in females as a result of a Y-autosomal translocation, causing a multiple sex chromosome system X1X2Y (Figure 2A). The autosomal set is composed by nine meta- or submetacentric and 13 acrocentric pairs. The X1 chromosome is a medium sized submetacentric, homologous to the X of other primates. The X2 chromosome is a medium sized acrocentric, corresponding to the original homologue of the autosome translocated to the Y chromosome. Constitutive heterochromatin (Figure 2B) was observed in centromeric regions of all autosomes. In addition, secondary C-bands were observed on pairs 1, 2 and 3, in the distal regions of chromosome pairs 4p, 5p, 6p and 4q and proximally on chromosome pair 15q.

Figure 2.

G - (A) and C-banding (B) in C. c. rubicundus.

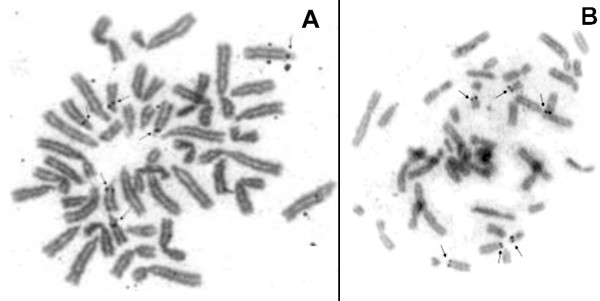

NOR-staining was found in the proximal region of the long arm of six acrocentric chromosomes both on P. irrorata (Figure 3A) and C. c. rubicundus (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

NOR-staining in P. irrorata (A) and C. c. rubicundus (B). NOR-regions are highlighted by arrows.

Molecular cytogenetics

Pithecia irrorata

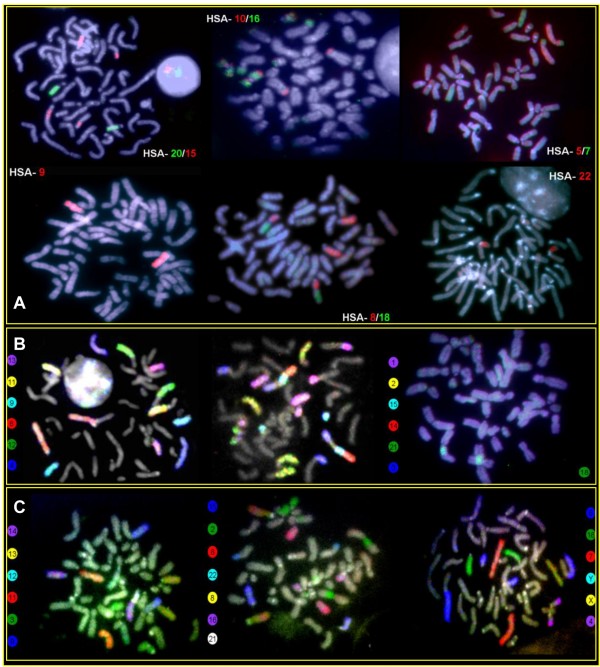

The homology map between human (HSA) and P. irrorata was established using chromosome paint probes (Figure 1A). Human probes showed 32 hybridization signals per haploid chromosome set (Figure 4A; Table 1). Fourteen autosomes and the X showed conserved synteny. From these, eight autosomes hybridized an entire P. irrorata chromosome (HSA 4, 6, 9, 11, 12, 17, 19, 20) and six were found associated with other chromosomes (HSA 5, 13, 14, 18, 21, 22). The remaining eight human autosome probes produced multiple signals in different chromosomes of P. irrorata. HSA 2, 7, 8, 10, 15, and 16 each hybridized two chromosomes, while HSA 1 and 3 each produced signals on three chromosomes per haploid set. Six chromosomes of P. irrorata correspond to the human syntenic associations 5/7, 2/16, 10/16, 8/18, 15/14 and 3/21, also previously found in the putative ancestral karyotype of Platyrrhini.

Figure 4.

Representative FISH-images from cross-species chromosome painting experiments using human probes in P. irrorata (A), human (B) and S. oedipus probes (C) in C. c. rubicundus. Beside each metaphase the respective probe composition and color assignment is given

Table 1.

Left (columns 1-3): Homology between human (HSA), P. irrorata (PIR) and C. c. rubicundus (CCR) chromosomes, Right (columns 4 and 5): Homology between S. oedipus (SOE) and C. c. rubicundus (CCR) chromosomes.

| HSA | PIR | CCR | SOE | CCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10, 9 (q) and 23 | 11, 17 and 6 (p) | 1 | 13 (distal q), 14 and 20 |

| 2 | 2 (q) and 4 (q) | 5 (q) and 7 (q) | 2 | 1 (proximal p), 13 (proximal q) and 16 |

| 3 | 15, 16 and 19 (distal q) | 19 (proximal q), 2 (p) and 1 (distal p) | 3 | 3 |

| 4 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 19 |

| 5 | 1 (proximal q + p) | 21 (proximal q) and 2 (q) | 5 | 15 |

| 6 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 2 (q) and 21 |

| 7 | 1 (distal p) and 11 | 21 (distal q) and 10 | 7 | 9 |

| 8 | 7 (p) and 12 | 3 (p) and 12 | 8 | 8 |

| 9 | 17 | 14 | 9 | 7 (q) and 18 |

| 10 | 6 (proximal p- distal q) and 2(p) | 4 (proximal p- distal q) and 7(p) | 10 | 5 |

| 11 | 18 | Y-autosome | 11 | 1 (q) |

| 12 | 14 | 6 (q) | 12 | 6 (q) |

| 13 | 8 (proximal q + p) | 13 | 13 | 10 |

| 14 | 13 (distal q) | 1 (distal q) | 14 | Y-autosome |

| 15 | 9 (p) and 13 (proximal q) | 1 (proximal q) and 18 | 15 | 4 |

| 16 | 6 (distal p- proximal q) and 4(p) | 4 (distal p- proximal q) and 5(p) | 16 | 11 |

| 17 | 21 | 16 | 17 | 2 (p) |

| 18 | 7 (q) | 3 (q) | 18 | 12 |

| 19 | 22 | 15 | 19 | 1 (distal p) |

| 20 | 20 | 1 (proximal p) | 20 | 17 |

| 21 | 19 (proximal q) | 19 (distal q) | 21 | 6 (p) |

| 22 | 8 (distal p) | 20 | 22 | 7 (p) |

| X | X | X | X | X |

Cacajao calvus rubicundus

Hybridizations of human paint probes resulted in 33 FISH-signals per haploid set of C. c. rubicundus (Figure 4B; Table 1). Thirteen human autosomes and the X showed conserved synteny. From these, HSA 4, 6, 9, 11, 13, 17, 19 and 22 probes hybridized onto a whole chromosome and HSA 12, 14, 18, 20, 21 were found in syntenic association. The remaining nine probes produced multiple signals in different chromosomes of C. c. rubicundus. HSA 2, 5, 7, 8, 10, 15, and 16 paints each hybridized two chromosomes, whereas HSA 1 and 3 probes each hybridized three chromosomes. Nine chromosomes of C. c. rubicundus presented the syntenic associations 1/12, 2/10, 2/16, 3/20/15/14, 3/5, 3/21, 5/7, 8/18 and 10/16. Human chromosome 11 was identified as the autosome involved in the Y-autosome translocation. Figure 2A summarizes the mapping of human chromosomes to the G-banded karyotype of C. c. rubicundus.

Hybridizations of S. oedipus (SOE) probes showed 28 signals per haploid chromosome set of C. c. rubicundus (Figure 4C; Table 1). SOE autosome 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, 13, 14, 15, 16, 18 and 20 probes each hybridized an entire chromosome and SOE 11, 12, 17, 19, 21 and 22 were found conserved but in association with other chromosomes. The remaining four probes each produced multiple signals in different chromosomes of C. c. rubicundus. SOE 6 and 9 hybridized onto two chromosomes and SOE 1 and 2 three chromosomes each per haploid set, respectively. Five chromosomes of C. c. rubicundus correspond to the syntenic associations 19/2/11, 17/6, 21/12, 22/9 and 2/1. The Y-autosome translocation involved the SOE 14 homologue. Figure 2A gives an overview of the mapping of the SOE chromosome probes to the G-banded karyotype of C. c. rubicundus.

Phylogenetic analysis

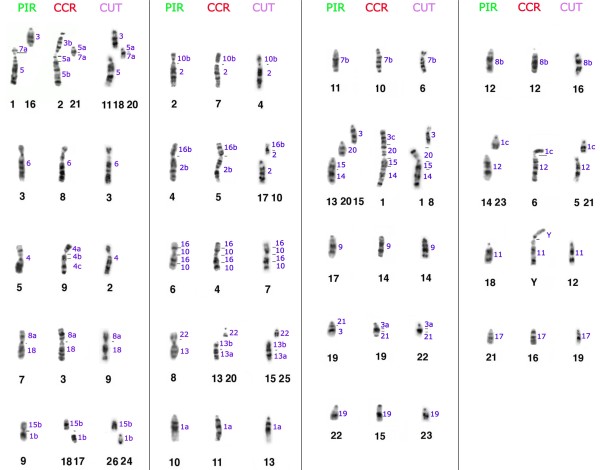

The comparative analysis of the P. irrorata, C. c. rubicundus (this study) and C. utahicki [19] karyotypes by G-banding and FISH with human whole chromosome probes is summarized in Figure 5. The results showed that the chromosomal differences found among the three taxa are consequence of centric fusions and fissions, pericentric and paracentric inversions, tandem fusions and a Y-autosome translocation (Table 2).

Figure 5.

Comparative karyotype analysis of P. irrorata, C. c. rubicundus and C. utahicki [19]by G-banding and FISH using human whole chromosome probes. The banded C. utahicki chromosomes were obtained from a previously unpublished metaphase [10].

Table 2.

Derived rearrangements that led to chromosome forms found in the three Pitheciinae taxa, taking into account data from chromosome painting with human whole chromosome probes (HSA) and from G-banding on P. irrorata (PIR), C. c. rubicundus (CCR) and C. utahicki (CUT - [19]).

| HSA | PIR | CCR | CUT | CHROMOSOME REARRANGEMENTS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10a/16a | 6 | 4 | 7 | Paracentric inversion |

| 7b | 11 | 10 | 6 | Pericentric inversion |

| 11 | 18 | Y | 12 | Y-autosome translocation |

| 3a/21 | 19 | 19 | 22 | Paracentric inversion |

| 5/7a 3b |

1 16 |

2 21 |

11 18 20 |

Inversions (pericentric and paracentric); centric fission and tandem fusion |

| 2b/16 | 4 | 5 | 10 17 |

Pericentric inversion; centric fission |

| 13 22 |

8 | 13 20 |

15 25 |

Pericentric inversion; centric fission |

| 1b 15b |

9 | 17 18 |

24 26 |

centric fission |

| 14/15a 20 3c |

13 20 15 |

1 | 1 8 |

Tandem fusion; centric fission; pericentric inversion |

| 1c 12 |

23 14 |

6 | 21 5 |

Centric fission and fusion; pericentric inversion |

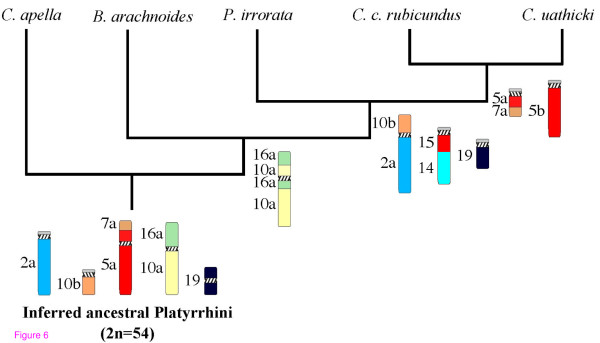

These data were translated into a binary matrix (Additional file 1) and were then subjected to parsimony analysis. A single most parsimonious three was obtained (Figure 6) comprising 45 steps with a consistency index of 0.978, a retention index 0.909 and a homoplasy index of 0.022.

Figure 6.

Most parsimonious tree based on the binary chromosome character matrix (additional file 1). The analysis was made employing the maximum parsimony method using PAUP software.

Discussion

The G-, C-banding and NOR-staining results on P. irrorata and C. c. rubicundus obtained in this study are in agreement with previously published data [10], including the difference in the diploid number for males and females in C. c. rubicundus [10,15-17].

Our results by chromosome painting in P. irrorata and C. c. rubicundus, as well as those from C. utahicki [19], demonstrated that these species conserved all human homologous syntenic associations found in the inferred ancestral New World primate karyotype (3a/21, 5/7a, 2b/16b, 8a/18, 14/15a and 10a/16a) [27]. The morphology and banding pattern of the 3a/21 homologues in C. c. rubicundus and C. utahicki is similar to the ancestral Platyrrhini type, while in P. irrorata it was modified by a paracentric inversion. The biarmed chromosome form 5/7a found in P. irrorata is also similar to the ancestral Platyrrhini type, whereas in C. c. rubicundus and C. utahicki this association is found on a presumably derived acrocentric chromosome. Cacajao further shows human chromosome 5 homologues fissioned into 5a1 and 5a2. A similar fission was previously found in Atelinae [24], however, involving different break points. Therefore, these fissions represent no synapomorphy, but rather occurred independently in the two clades. Chromosome forms 2b/16b and 8a/18 each showed similar morphology compared to homologues from other Platyrrhini and are therefore considered ancestral traits. The association 14/15a was observed in an acrocentric chromosome in P. irrorata, while in C. utahicki it has fused with chromosome 20 forming the association 20/15/14 on chromosome 1. In C. c. rubicundus it was found fused with the human 3/20 homolog, leading to the association 3/20/15/14. Finally, a pericentric inversion was observed for chromosome form 10a/16a in all species analyzed here, resulting in chromosome form 16a/10a/16a/10a. This derived inversion has also been found previously in Callicebus [28], indicating that Pithecia, Chiropotes and Cacajao are sister groups of Callicebus. This observation is in agreement with recent classifications based on molecular data, supporting the classification of subfamilies Pitheciinae and Atelinae as sister groups included in the family Atelidae [8,12].

A comparative chromosome analysis of the three Pitheciinae species shows further synapomorphies shared between C. c. rubicundus and C. utahicki (fission of 5/7, resulting in separate 5a1 and 5a2 segments, and fusion 20/15/14), shared between P. irrorata and C. c. rubicundus (acrocentric 7b, acrocentric 12) and for Pitheciinae in general (fusion 2a/10b, acrocentric 15/14 and acrocentric 19). In contrast, no derived chromosome forms shared between P. irrorata and C. utahicki were found.

Our phylogenetic analysis suggests that P. irrorata, C. c. rubicundus and C. utahicki are a monophyletic group. Further, and as expected, the chromosomal data supported by exclusive synapomorphies demonstrates that C. c. rubicundus and C. utahicki are sister taxa. Moreover, P. irrorata was placed in a more basal position, having retained a karyotype closer to that of the inferred ancestral Platyrrhini. This phylogenetic arrangement supports previously published phylogenies [5-8,12], and also the phenetic inferences [10].

Conclusions

In conclusion, this comparative chromosomal analysis clarifies some intrageneric relationships within Pitheciinae, while the position of this group in relation to Callicebus and Aotus remained undefined. Additional comparative high-resolution molecular cytogenetic studies will be necessary to precisely define the rearrangements between Aotus and Callicebus to clarify their phylogenetic relationships with Pitheciinae.

Authors' contributions

LFMF carried out the chromosome painting in P. irrorata, organized the data and wrote most of the paper. PJSA carried out the conventional chromosome analysis of P. irrorata and performed the cladistic analysis. JCP participated of the techniques development and contributed to the discussion of data. EHCO carried out the conventional chromosome analysis of C. c. rubicundus. AP collected the samples, classified the species and discussed the phylogenetic implications of the data. MN and SM carried out the chromosome painting in C. c. rubicundus and discussed the phylogenetic implications of the data. CYN conceived of the study, and coordinated the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Binary chromosome character matrix. A table listing all the characters found in this study and heir alternative states.

Contributor Information

Liane FM Finotelo, Email: lianefiuza@hotmail.com.

Paulo JS Amaral, Email: paulojsamaral@terra.com.br.

Julio C Pieczarka, Email: julio@ufpa.br.

Edivaldo HC de Oliveira, Email: ehco@ufpa.br.

Alcides Pissinati, Email: pissinatticprj@terra.com.br.

Michaela Neusser, Email: Michaela.Neusser@lrz.uni-muenchen.de.

Stephan Müller, Email: S.Mueller@lrz.uni-muenchen.de.

Cleusa Y Nagamachi, Email: cleusanagamachi@pq.cnpq.br.

Acknowledgements

Funding to the Brazilian authors was provided by CNPq, CAPES, UFPA, and FAPESPA.

References

- Hershkovitz P. A preliminary report and critical review with description of a new species and a new subspecies. American journal of Primatology. 1987;12:387–468. doi: 10.1002/ajp.1350120402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershkovitz P. A preliminary taxonomic review of south american berded saki monkeys genus Chiropotes (Cebidae, Platyrrhini), with description of a new subspecies. Fieldiana. 1985;27:1–46. doi: 10.1002/ajp.1350120102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershkovitz P. Uacaries, New World Monkeys of the genus Cacajao (Cebidae, Platyrrhini): A preliminary taxonomic review with the description of a new subspecies. American Journal of Primatology. 1987;12:1–53. doi: 10.1002/ajp.1350120102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonvicino CR, Boubli JP, Otazu IB, Almeida FC, Nascimento FF, Coura JR, Seuánez HN. Morphologic, karyotypic, and molecular evidence of a new form of Chiropotes (Primates, Pitheciinae) American Journal of Primatology. 2003;61:123–133. doi: 10.1002/ajp.10115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberger AL. In: Ecology and Behavior of Neotropical Primates. 1. Coimbra-Filho AF, Mittermeier RA, editor. Vol. 1. Academia Brasileira de Ciências; 1981. Systematics: the higher taxa; pp. 9–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ford SM. In: Comparative Primate Biology: Systematics, Evolution, and Anatomy. Swindler DR, Alan R, editor. Vol. 1. Liss Inc, New York; 1986. Systematics of the New World Monkeys; pp. 73–135. [Google Scholar]

- Kay RF. The phyletic relationships of extant and fossil Pitheciinae (Platyrrhini, Anthropoidea) Journal of Human Evolution. 1990;19:175–208. doi: 10.1016/0047-2484(90)90016-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider H, Schneider MPC, Sampaio I, Harada ML, Stanhope M, Czelusniak J, Goodman M. Molecular phylogeny of the New World Monkeys (Platyrrhini, Primates) Molecular Phylogeny Evolution. 1993;2(3):225–242. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1993.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider MPC, Schneider H, Sampaio I, Carvalho-Filho N, Encarnacion F, Montoya E, Salzano FM. Biochemical Diversity and Genetic distance in the Pitheciinae Subfamily (Primates, Platyrrhini) Primates. 1995;36(1):129–134. doi: 10.1007/BF02381920. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moura-Pensin C, Pieczarka JC, Nagamachi CY, Muniz JAPC, Brigido MCO, Pissinati A, Marinho ANR, Barros RMS. Cytogenetic relations among the genera of the subfamily Pitheciinae (Cebidae, Primates) Caryologia. 2001;54(4):385–391. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider H, Sampaio I, Harada ML, Barroso CML, Schneider MPC, Czelusniar J, Goodman M. Molecular phylogeny of the New World monkeys (Platyrrhini, Primates) based on two unliked nuclear genes: IRBP intron 1 and β-globin sequences. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 1996;100:153–179. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199606)100:2<153::AID-AJPA1>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider H. The current status of the New World Monkeys phylogeny. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 2000;72(2):165–172. doi: 10.1590/S0001-37652000000200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canavez FC, Moreira MA, Simon F, Parham P, Seuanez HN. Phylogenetic relationships of the Callitrichinae (Platyrrhini, primates) based on beta2-microglobulin DNA sequences. American Journal of Primatology. 1999;48:225–236. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2345(1999)48:3<225::AID-AJP4>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Dornum M, Ruvolo M. Phylogenetic relationships of the New World monkeys (Primates, Platyrrhini) based on nuclear G6PD DNA sequences. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 1999;11:459–476. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1998.0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koiffmann CP, Saldanha PH. The karyotype of Cacajao melanocephalus (Platyrrhini, Primates) Folia Primatologica. 1981;36:150–155. doi: 10.1159/000156015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutrillaux B, Descailleaux J, Viegas-Pequignot E, Couturier J. Y-autosome translocation in Cacajao calvus rubicundus (Platyrrhini) Annales de Génétique. 1981;24:197–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viegas-Pequignot E, Koiffmann CP, Dutrillaux B. Chromosomal phylogeny of Lagothrix, Brachyteles, and Cacajao. Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics. 1985;39:99–104. doi: 10.1159/000132115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Boer LEM. The somatic complement and the idiogram of Pithecia pithecia pithecia (Linnaeus, 1766) Folia Primatologica. 1975;23:149–157. doi: 10.1159/000155668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanyon R, Bigoni F, Slaby T, Müller S, Stone G, Bonvicino CR, Neusser M, Seuánez HN. Multi-directional chromosome painting maps homologies between species belonging to three genera of New World monkeys and human. Chromosoma. 2004;113:305–315. doi: 10.1007/s00412-004-0320-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma RS, Babu A. Human chromosomes, principles and techniques. New York, McGraw-Hill, Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sumner AT. A simple technique for demonstrating centromeric heterochromatin. Experimental Cell Research. 1972;75:304–306. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(72)90558-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell WM, Black DA. Controlled silver-staining of nucleolus organizer regions with a protective colloidal developer: a 1-step method. Experientia. 1980;36:1014–1015. doi: 10.1007/BF01953855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller S, Neusser M, O'Brien PC, Wienberg J. Molecular cytogenetic characterization of the EBV-producing cell line B95-8 (Saguinus oedipus, Platyrrhini) by chromosome sorting and painting. Chromosome Research. 2001;9:689–693. doi: 10.1023/A:1012960525326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Oliveira EHC, Neusser M, Pieczarka JC, Nagamachi CY, Sbalqueiro IJ, Müller S. Phylogenetic inferences of Atelinae (Platyrrhini) based on multi-directional chromosome painting in Brachyteles arachnoides, Ateles paniscus paniscus and Ateles b. marginatus. Cytogenetics and Genome Research. 2005;108:183–190. doi: 10.1159/000080814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral PJS, Finotelo LFM, De Oliveira EH, Pissinatti A, Nagamachi CY, Pieczarka JC. Phylogenetic studies of the genus Cebus (Cebidae-Primates) using chromosome painting and G-banding. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2008;8:169. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telenius H, Carter S, Müller S, Morescalchi A, Wienberger J. Degenerate oligonucleotide-primed PCR (DOP-PCR): general amplification of target DNA by a single degenerate primer. Genomics. 1992;13:718–725. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(92)90147-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neusser M, Stanyon R, Bigoni F, Wienberg J, Müller S. Molecular cytotaxonomy of New World Monkeys (Platyhrrini). Comparative analysis of five species by multicolor chromosome painting gives evidence for a classification of Callimico goeldii within the family of Callitrichidae. Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics. 2001;94:206–215. doi: 10.1159/000048818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros RMS, Nagamachi CY, Pieczarka JC, Rodrigues LRR, Neusser M, De Oliveira EH, Wienberg J, Muniz APC, Rissino JD, Müller S. Chromosomal studies in Callicebus donacophilus pallescens, with classic and molecular cytogenetic approaches: multicolour FISH using human and Saguinus oedipus painting probes. Chromosome Research. 2003;11:327–334. doi: 10.1023/A:1024039907101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Binary chromosome character matrix. A table listing all the characters found in this study and heir alternative states.