Abstract

Summary: Multiple sequence alignment (MSA) is an important step in comparative sequence analyses. Parallelization is a key technique for reducing the time required for large-scale sequence analyses. The three calculation stages, all-to-all comparison, progressive alignment and iterative refinement, of the MAFFT MSA program were parallelized using the POSIX Threads library. Two natural parallelization strategies (best-first and simple hill-climbing) were implemented for the iterative refinement stage. Based on comparisons of the objective scores and benchmark scores between the two approaches, we selected a simple hill-climbing approach as the default.

Availability: The parallelized version of MAFFT is available at http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/software/. This version currently supports the Linux operating system only.

Contact: kazutaka.katoh@aist.go.jp

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

Multi-core CPUs are becoming more commonplace. This type of CPU can perform various bioinformatic analyses in parallel, including database searches, in which tasks can be split into multiple parts (eg. Mathog, 2003). The parallelization of a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) calculation is a complicated problem, because the task cannot be naturally divided into independent parts. Thus, there have been several reports on the parallelization of multiple alignment calculations with various algorithms on different types of parallel computer systems (Chaichoompu et al., 2006; Date et al., 1993; Ishikawa et al., 1993; Kleinjung et al., 2002; Li, 2003). The present study targets a currently popular type of PC, which has 1–2 processor(s), each with 1–4 core(s), and shared memory space.

MAFFT (Katoh et al., 2002; Katoh and Toh, 2008) is a popular MSA program. To improve its usefulness on multi-core PCs, we have implemented a parallelized version, using the POSIX Threads (pthreads) library. The aim is to efficiently parallelize MAFFT while keeping the quality of the results. The calculation procedure of the major options of MAFFT consists of three stages: (i) all-to-all comparison, (ii) progressive alignment and (iii) iterative refinement.

There is no problem in the parallelization of the first stage, the all-to-all comparison. Multiple threads can process different pairwise alignments simultaneously and independently, with little loss of CPU time.

In the progressive alignment stage (Feng and Doolittle, 1987; Thompson et al., 1994), group-to-group alignment calculations are performed along with a guide tree. This process is not very suitable for parallelization, because the order of the alignment calculations is restricted by the guide tree. That is, an alignment at a node cannot be performed until all of the alignments in its child nodes have been completed. As long as this restriction is maintained, alignments can be performed at child nodes that are independent of each other. Thus, in our implementation, the efficiency of parallelization is inevitably low in this stage. Although it is possible to design a guide tree that is suitable for parallelization (Li, 2003), we have not adopted this approach, because in MAFFT this stage consumes less CPU time than the other two (for details see Supplementary Table, in which the percentage of execution time of this stage is below 2%).

In each step of the iterative refinement process (Barton and Sternberg, 1987; Berger and Munson, 1991; Gotoh, 1993), an alignment is divided into two sub alignments and then the two sub alignments are realigned, according to the tree-dependent iterative strategy (Gotoh, 1996; Hirosawa et al., 1995), to obtain an alignment with a higher objective score. We implemented the best-first approach and a simple hill-climbing approach for this stage.

In the best-first approach, the realignments are performed for all of the possible 2N − 3 divisions on the tree, and then the alignment with the highest objective score is selected, where N is the number of sequences. This process is repeated until no alignment with a higher score is found. Since only the alignment with the highest score contributes to the next step and the other alignments are discarded, this approach is obviously inefficient.

As an alternative, in which fewer alignments are discarded, we implemented a simple hill-climbing approach. Realignment processes are randomly assigned to the multiple threads and performed in parallel. If the score of a new alignment by a thread is better than the original alignment, then it instantly replaces the original alignment. Accordingly, there can be a case where two or more different threads in parallel produce different, better alignments. In such a case, the first (in terms of time) alignment is selected, while the other alignments are discarded. The simple hill-climbing approach is expected to be efficient when the number of threads is small. With an increase in the number of threads, the number of discarded alignments increases and thus the efficiency will decrease. The resulting alignment depends on random numbers.

The best-first approach provides a stable result independently of random numbers, while the simple hill-climbing approach generally has an advantage, in terms of the speed. Therefore, we examined which is more suitable for the multiple alignment problem. To compare their efficiencies, the simplest iterative refinement option with no sequence weighting was applied to all 218 alignments in BAliBASE version 3 (Thompson et al., 2005). The simple hill-climbing approach was run 10 times with different random numbers. For each of the 218 × 10 runs with the simple hill-climbing approach, the final objective score was compared with the final objective score obtained from the best-first approach. The former was higher than the latter in 972 cases, while the former was lower than the latter in 917 cases. In the remaining 291 cases, the two alignments were identical to each other. This result rationalizes the use of the simple hill-climbing approach.

To confirm that the accuracies of the alignments by the two approaches are indistinguishable from each other and from that generated by the serial version, the BAliBASE benchmark scores were also calculated, where the differences from the reference alignments (assumed to be correct) were evaluated as the SP and TC scores (Thompson et al., 1999). The overall average SP scores of one of the most accurate MAFFT options, L-INS-i, were 0.8728 ± 0.0003649 (simple hill-climbing; average ± SD), 0.8720 (best-first) and 0.8722 (serial version). The overall average TC scores were 0.5926 ± 0.001162 (simple hill-climbing), 0.5927 (best-first) and 0.5928 (serial version). The average and the SD of the scores of the simple hill-climbing approach were calculated from 10 runs with different random numbers.

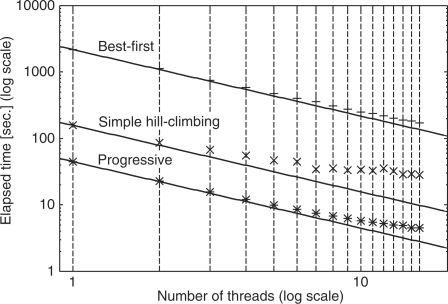

Figure 1 shows the actual time required to calculate the largest alignment (BB30003; 142 sequences × 451 sites including gaps) in BAliBASE, using different numbers (1–16) of threads on a 16 core PC (4 × Quad-Core AMD Opteron Processor 8378). When the number of threads is eight, the efficiencies of parallelization are 0.89 and 0.55 for the best-first approach and the simple hill-climbing approach, respectively. As expected, the loss of speed in the simple hill-climbing approach increases with an increase in the number of threads. This is because the number of discarded alignments increases, as mentioned above. The loss of speed for the best-first approach is relatively small. However, within the range of the target systems in the present study (common multi-core PCs), the simple hill-climbing approach is faster, and therefore was adopted as the default.

Fig. 1.

Efficiency of parallelization for an iterative refinement option (L-INS-i) with two parallelization strategies (best-first and simple hill-climbing) and a progressive option (L-INS-1). Lines correspond to the ideal situation where (Elapsed time with n threads) = (Elapsed time with single thread) / n. The command-line arguments are: Best-first, mafft-linsi --bestfirst --thread n input Simple hill-climbing, mafft-linsi --thread n input Progressive, mafft-linsi --maxiterate 0 --thread n input

We also examined the applicability of the simple hill-climbing approach to larger data. As shown in Supplementary Table, the efficiency with eight threads is 0.55–0.74 for five datasets, each with ∼1000 sequences.

MAFFT versions ≥6.8 switch to the pthread version by simply adding the --thread n argument, where n is the number of threads to use. No special configuration is required for parallel processing on a multi-core PC with the Linux operating system.

Funding: KAKENHI for Young Scientists (B) 21700326 from Monbukagakusho, Japan (to K.K.).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- Barton GJ, Sternberg MJ. A strategy for the rapid multiple alignment of protein sequences. confidence levels from tertiary structure comparisons. J. Mol. Biol. 1987;198:327–337. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90316-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger MP, Munson PJ. A novel randomized iterative strategy for aligning multiple protein sequences. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1991;7:479–484. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/7.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaichoompu K, et al. Proceedings 20th IEEE International Parallel & Distributed Processing Symposium. IEEE Computer Society Press; 2006. MT-ClustalW: multithreading multiple sequence alignment; p. 280. [Google Scholar]

- Date S, et al. Multiple alignment of sequences on parallel computers. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1993;9:397–402. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/9.4.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng DF, Doolittle RF. Progressive sequence alignment as a prerequisite to correct phylogenetic trees. J. Mol. Evol. 1987;25:351–360. doi: 10.1007/BF02603120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh O. Optimal alignment between groups of sequences and its application to multiple sequence alignment. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1993;9:361–370. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/9.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh O. Significant improvement in accuracy of multiple protein sequence alignments by iterative refinement as assessed by reference to structural alignments. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;264:823–838. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirosawa M, et al. Comprehensive study on iterative algorithms of multiple sequence alignment. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1995;11:13–18. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/11.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa M, et al. Multiple sequence alignment by parallel simulated annealing. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1993;9:267–273. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/9.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, et al. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3059–3066. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Toh H. Recent developments in the MAFFT multiple sequence alignment program. Brief Bioinform. 2008;9:286–298. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbn013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinjung J, et al. Parallelized multiple alignment. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:1270–1271. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.9.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li KB. ClustalW-MPI: ClustalW analysis using distributed and parallel computing. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1585–1586. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathog DR. Parallel BLAST on split databases. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1865–1866. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, et al. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, et al. BAliBASE 3.0: latest developments of the multiple sequence alignment benchmark. Proteins. 2005;61:127–136. doi: 10.1002/prot.20527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, et al. BAliBASE: a benchmark alignment database for the evaluation of multiple alignment programs. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:87–88. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.