Abstract

Summary: Genomes undergo large structural changes that alter their organization. The chromosomal regions affected by these rearrangements are called breakpoints, while those which have not been rearranged are called synteny blocks. Lemaitre et al. presented a new method to precisely delimit rearrangement breakpoints in a genome by comparison with the genome of a related species. Receiving as input a list of one2one orthologous genes found in the genomes of two species, the method builds a set of reliable and non-overlapping synteny blocks and refines the regions that are not contained into them. Through the alignment of each breakpoint sequence against its specific orthologous sequences in the other species, we can look for weak similarities inside the breakpoint, thus extending the synteny blocks and narrowing the breakpoints. The identification of the narrowed breakpoints relies on a segmentation algorithm and is statistically assessed. Here, we present the package Cassis that implements this method of precise detection of genomic rearrangement breakpoints.

Availability: Perl and R scripts are freely available for download at http://pbil.univ-lyon1.fr/software/Cassis/. Documentation with methodological background, technical aspects, download and setup instructions, as well as examples of applications are available together with the package. The package was tested on Linux and Mac OS environments and is distributed under the GNU GPL License.

Contact: Marie-France.Sagot@inria.fr

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Large scale modifications of the genome, such as inversions or transpositions of DNA segments, translocations between non-homologous chromosomes, fusions or fissions of chromosomes and deletions or duplications of small or large portions are called rearrangements. They are further involved in evolution, speciation and also in cancer.

One crucial step before analysing the rearrangements and their possible relation with other genomic features is to locate these events on a genome. In the case of two genomes, it is possible to identify conserved regions, also known as synteny blocks, by comparing the order and orientation of orthologous markers along their chromosome sequences. A region located between two consecutive synteny blocks on one genome, whose orthologous blocks are rearranged in the other genome (not consecutive or not in the same relative orientations), is called breakpoint.

As far as we know, current methods for detecting breakpoints [Grimm-synteny (Pevzner and Tesler, 2003) Mauve (Darling et al., 2004), for example] are in fact strategies for detecting synteny blocks: they provide the coordinates of the breakpoint regions only as a byproduct, simply by returning regions that are not found in a conserved synteny. Lemaitre et al. (2008) developed a formal method that aims to go one step further and to extend the synteny blocks by focusing on the breakpoints themselves. This method was shown to improve significantly the precision of breakpoint locations on mammalian genomes and enables to better characterize breakpoint sequences and distributions (Lemaitre et al., 2008, 2009) (see also datasets and comparisons available together with the package).

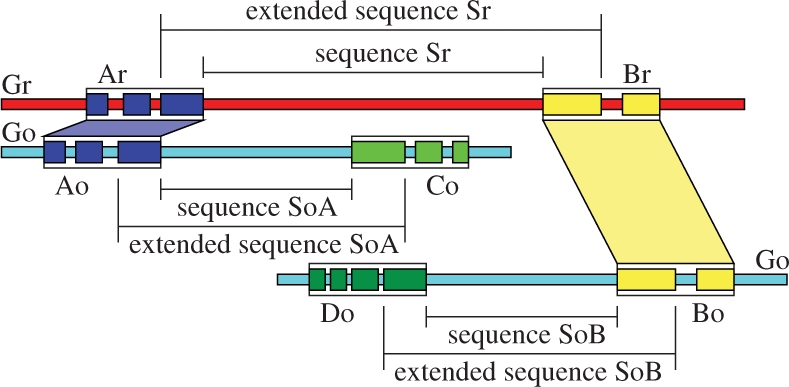

The first step of the method is to process a list of orthologous genes to identify synteny blocks between the genomes of two related species (a reference genome Gr and a second genome Go). This step outputs a list of ordered and non-intersecting synteny blocks that are used to identify the breakpoints. For each breakpoint on the genome Gr, we can define three sequences: the breakpoint sequence Sr, and its two orthologous sequences on the second genome Go, SoA and SoB (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Sequence Sr is defined by the boundaries of two consecutive synteny blocks Ar and Br on the genome Gr. SoA (SoB) is defined by the boundaries of the orthologous block Ao (Bo) and of the previous/next synteny block (according to the orientation of the blocks) in the genome Go. To perform the segmentation, the package considers the extended version of the sequences Sr, SoA and, SoB which includes the first/last genes of the synteny blocks.

In a second step, the method aligns the breakpoint sequence Sr against SoA and SoB and the information provided by the hits of the alignments is coded along Sr as a sequence of discrete values. A segmentation algorithm calculates the best segmentation of this sequence of discrete values into at most three segments: a segment related with SoA, a segment related with SoB and a central segment which will represent the refined breakpoint.

2 CASSIS

Cassis is a package which contains the implementation in Perl and R of the methods developed by Lemaitre et al. (2008).

The package receives as input data a list of pairs of one2one orthologous genes which can be found in the genomes Gr and Go.

First, all pairs of intersecting genes which have same order and direction in both genomes are merged. Overlapping genes that do not respect this criterium are discarded. After that, the list of genes is used to create synteny blocks according to the algorithm described by Lemaitre et al. using k = 2. Basically, the parameter k controls for the flexibility degree of the method. With k = 2, the algorithm enables individual isolated genes to be out of order without disrupting a synteny block, and all synteny blocks must contain at least two genes.

For each breakpoint on the genome Gr, we define the boundaries of the sequences Sr, SoA and, SoB according to the synteny blocks. We perform the alignment with LASTZ (Harris, 2007) of the sequences Sr against SoA and Sr against SoB. LASTZ was chosen because it was shown to be more sensitive in the alignment of intergenic sequences. To obtain better results in the segmentation step, we align the extended version of the sequences Sr, SoA and, SoB. This includes the genes that are on the boundaries of the blocks that define the sequence (Fig. 1).

If at least one of the alignments (Sr against SoA or Sr against SoB) leads to a hit, the breakpoint sequence can be refined. The segmentation algorithm is applied to the breakpoint and the refined coordinates can thus be obtained. During this step, we perform a statistical test that verifies if the breakpoint region is actually structured into three segments to validate the obtained results.

The package Cassis also works with lists of orthologous synteny blocks. In this case, the steps of overlapping identification and synteny blocks definition are not executed and the input data is directly submitted to the breakpoint identification step. As we do not have information about the genes that are inside of the synteny blocks that are given by the user, to build the extended sequences we add on each side of the sequence a fragment of length L. If the resulting extended sequence has length smaller than Lmin, it means that we have a considerable overlap between consecutive blocks. Thus, we cannot properly define the sequence and the corresponding breakpoint is not refined. The default values of the parameters L and Lmin are 50 kbp. This was chosen because it is close to the average size of a gene.

The package contains a main script which controls the whole process of breakpoint identification and refinement. The script is very simple to use and receives the following parameters:

Input table: tab separated values file that contains the orthology information. It can be a list of pairs of one2one ortologous genes or a list of pairs of orthologous synteny blocks, which can be found on the genomes Gr and Go;

Input type: flag that indicates the type of the given input table: G for genes and B for synteny blocks;

Directory Gr (Go): directory where the script can find the sequences of the chromosomes of the genome Gr (Go);

Output directory: directory which will receive the results; and

Other optional parameters including a stringency level for the LASTZ alignments and the values for sequences extensions (L and Lmin).

The script generates a table that contains, for each breakpoint, the chromosome of the genome Gr where the breakpoint is located, the coordinates of the breakpoint before and after the segmentation process and a flag that can have the following values: −1, 0 and 1. The value −1 denotes that it was impossible to execute the segmentation because the alignments output no hit. The values zero/one denote, respectively, that the segmentation failed/passed on the statistical test. The package also produces, for each breakpoint, a plot with the graphical representation of the segmentation.

We recommend the use of chromosome sequences whose repeats have been masked. The alignment of masked sequences results in more relevant hits and, consequently, on better segmentation results.

The package contains a main script which controls the execution of a set of scripts that performs atomic tasks. The modularization of the implementation answers to the needs of advanced users who may desire to create their own pipelines of breakpoint refinement.

Funding: Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (4676/08-4 to C.B.); Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (472504/2007-0, 479207/2007-0 and 483177/2009-1 to Z.D., partial); French project ANR (MIRI BLAN08-1335497); French-UK project ANR-BBSRC (MetNet4SysBio ANR-07-BSYS 003 02); Project ERC Advanced Grant Sisyphe.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Darling ACE, et al. Mauve: alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004;14:1394–1403. doi: 10.1101/gr.2289704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris RS. Improved pairwise alignment of genomic DNA. PhD Thesis, The Pennsylvania State Univeristy; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lemaitre C, et al. Precise detection of rearrangement breakpoints in mammalian chromosomes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:286. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaitre C, et al. Analysis of fine-scale mammalian evolutionary breakpoints provides new insight into their relation to genome organisation. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:335. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pevzner P, Tesler G. Genome rearrangements in mammalian evolution: lessons from human and mouse genomes. Genome Res. 2003;13:37–45. doi: 10.1101/gr.757503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]