Abstract

Pulmonary surfactant protein D (SP-D), a member of the collectin family, is an innate immune molecule critical for defense that can also modulate adaptive immune responses. We previously showed that SP-D deficient mice exhibit enhanced allergic responses, and that SP-D induction requires lymphocytes. Thus, we postulated that SP-D may decrease adaptive allergic responses through interaction with T cells. In this study, we used two forms of SP-D, a dodecamer (SP-D dodec) and a shorter fragment containing the trimeric neck and carbohydrate recognition domains (SP-D NCRD). Both forms decreased immune responses in vitro and in a murine model of pulmonary inflammation. SP-D NCRD increased transcription of cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA4), a negative regulator of T cell activation, in T cells. SP-D NCRD no longer decreased lymphoproliferation and IL-2 cytokine production when CTLA4 signals were abrogated. Administration of SP-D NCRD in vivo no longer decreased allergen induced responses when CTLA4 was inhibited. Our results indicate that SP-D decreases allergen responses, an effect that may be mediated by increase of CTLA4 in T cells.

Keywords: SP-D, CTLA4, allergy, inflammation

Introduction

Surfactant protein D (SP-D)4, a member of the collectin family, is primarily produced by alveolar type II cells and non-ciliated Clara cells in the lung (1). The structure of SP-D includes 4 distinct domains, including an amino terminus, collagen-like domain, a neck domain, and C-terminal carbohydrate recognition domains (CRD). SP-D was originally defined as a host defense innate immune molecule (2). Recently, SP-D has been shown to play a role in allergic inflammation by modulating adaptive immune lymphocyte responses. SP-D deficient mice exhibit enhanced allergic responses, suggesting that SP-D has immunosuppressive properties (3). In addition, allergic and other inflammatory responses are accompanied by increased bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and serum SP-D in animal models and human asthmatics (4–9). SP-D administration inhibits murine allergic airway responses (10, 11). In lymphocytes isolated from asthmatic children, treatment of SP-D can suppress lymphocyte proliferation in the late phase of bronchial inflammation (12). In lymphocyte deficient recombinase-activating gene-deficient (RAG) mice, SP-D is not increased after induction of allergen, suggesting that SP-D induction requires lymphocytes (5). While SP-D modulation of T cells has not been well defined, SP-D has been shown to suppress activated CD3+/CD4+ T cell proliferation in the absence of accessory cells (13).

Activated T cells express negative regulators including cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA4) (14). Triggering of CTLA4 signaling decreases T cell proliferation and cytokine production by recently activated T cells in inflammatory immune responses (15, 16). Since CTLA4 inhibits T cell activation and plays a central role in maintaining T cell homeostasis, we asked whether the innate molecule SP-D can also impact T cells and influence CTLA4. Our results showed that SP-D decreases allergic inflammation, an effect that may be mediated by an increase of CTLA4 gene expression in T cells, suggesting a potential pathway by which innate immunity interacts with adaptive immunity.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Six- to eight-week old BALB/c male mice were purchased from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN). The mice were maintained according to the guidelines of the Animal Welfare Program from School of Medicine, University of California, San Diego.

Recombinant human SP-D

The full length human SP-D dodecamers (dodec) and a recombinant human N-terminally His-tagged, trimeric neck and carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD) fusion protein (SP-D NCRD) was generated and purified as previously described (17). SP-D NCRD shows normal folding of the lectin domain and retain the ligand binding properties of the native protein (18). Residual endotoxin levels were quantified using an end-point chromogenic assay (QCL-1000; Cambrex Corp., E. Rutherford, NJ) and only preparations containing less than 0.2 ng endotoxin/mg of SP-D NCRD protein were used.

Antibodies

Mouse anti-CTLA4 (UC10-4F10-11) (aCTLA4) and control antibody hamster Ig were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA).

Cell lines and treatments

Murine splenocytes and EL4 cells (murine thymoma cell line) were grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat inactivated FCS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 50 U of penicillin/ml, and 50 μg of streptomycin/ml. Murine spleen cells were treated with SP-D NCRD (10 μg/ml) for 24 hour at 106 cells/ml. EL4 cells were treated with SP-D NCRD (10 μg/ml) for 24 h at 2 × 106 cells/ml. For proliferation and cytokine in vitro assays, murine spleen cells were also treated with 5 μg/ml of ConA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 5 μg/ml of aCTLA4 or remain untreated.

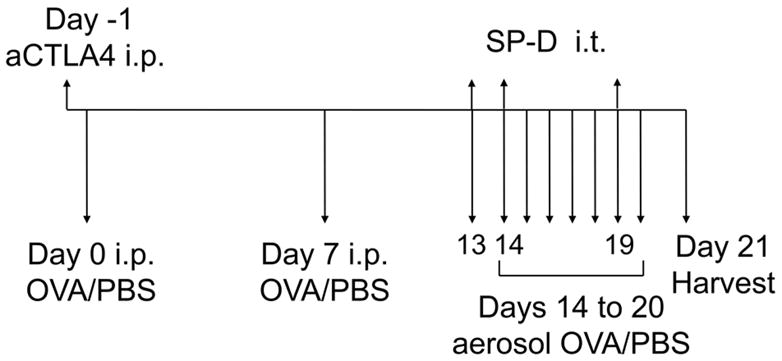

Ovalbumin sensitization and challenge

Mice were sensitized and challenged with the allergen ovalbumin (OVA) as previously described (16). OVA mice were sensitized via intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection with 10 μg of chicken OVA (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 mg of Al(OH)2 (alum; Sigma-Aldrich) in 0.2 ml of phosphate buffer saline (PBS) (Sigma-Aldrich), followed by an injection on day 7 with identical reagents. PBS mice received 1 mg of alum in 0.2 ml of PBS without OVA. On days 14–20, mice received challenges with 6% OVA or PBS, respectively, for 20 min/day via an ultrasonic nebulizer (model 5000; DeVillbiss). All groups were sacrificed at day 21 and analyzed for the allergic parameters described below.

Treatment protocols

SP-D dodec (3 μg) or SP-D NCRD (3 μg) was administered to mice intratracheally (i.t.) on days 13, 14, and 19. aCTLA4 (100 μg) was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) 1 day before sensitization (day –1).

Bronchoalveolar lavage analysis

Each mouse underwent bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) as previously described (16). BAL cells were pelleted and the supernatant was stored at −80°C. Cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640 (5 × 105 cells/ml). Slides for differential cell counts were prepared with Cytospin (Shandon) and fixed and stained with Diff-Quik (Dade Behringm). For each sample, an investigator blinded to the treatment groups performed two counts of 100 cells.

ELISA

IL-13 was measured by ELISA according to the manufacturer’s specifications (R&D Systems). Briefly, samples of BAL fluid were aliquoted in duplicate into 96-well plates (50 μl/well) precoated with Ab to specific cytokines and assayed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. OD was measured at 450 nm. Cytokine concentrations were determined by comparison with known standards.

Cytokine Assays

IL-5 and IL-2 from supernatant was assayed with LINCOplex mouse cytokine assays following manufacturer’s instructions (LINCO Research, St Charles, MO). The assay is based on conventional sandwich assay technology. The antibody specific to each cytokine is covalently coupled to Luminex microspheres, with each antibody coupled to a different microsphere uniquely labeled with a fluorescent dye. The microspheres are incubated with standards, controls, and samples (25 μl) in a 96-well microtiter filter plate for 1 h at room temperature. After incubation, the plate is washed to remove excess reagents. Detection antibody is then added in the form of a mixture containing each of the eight antibodies. After 30 min incubation at room temperature, streptavidin-phycoerythrin is added for an additional 30 min. After a final wash step, the beads are resuspended in buffer and read on the Luminex100 instrument to determine the concentration of the cytokines of interest. All specimens received were tested in replicate wells. Results were reported as the mean of the replicates.

Serum IgE

Total serum IgE levels were determined by ELISA as previously described (16). Total serum IgE concentrations were calculated by using standard curve generated with commercial IgE standard (BD Biosciences Pharmingen).

Lymphocyte proliferation

The proliferation of murine spleen cells (2 × 105 cells/well) was determined using a colorimetric immunoassay for the quantification of cell proliferation, based on the measurement of BrdU incorporation during DNA synthesis (Roche, USA). The BrdU ELISA was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cells were pulsed with 10 μl/well of 100 μM BrdU solution during the last 18 h of Con A-stimulation. Seventy-two hours after the initial stimulation, plates were centrifuged and cells denatured with FixDenat solution then incubated for 120 min with 1:100 diluted mouse anti-BrdU mAbs conjugated to peroxidase. After removing antibody conjugate, substrate solution was added for 20 min and the reaction stopped by adding 1 M H2SO4 solution. The absorbance was measured within 30 min at 370 nm with a reference wavelength at 690 nm using an ELISA plate reader.

Binding assay

Murine spleen cells (BALB/c) were incubated with or without His-tagged SP-D NCRD (2 μg/ml) for 1 hour at 37 °C. The cells were then stained with anti-CD3 (PECy7), anti-CD4 (APC), anti-His (FITC) antibodies or their isotype antibodies (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). The binding of His-tagged SP-D NCRD to spleen cells is assessed by flow cytometry in the CD3+CD4+ T cells, and is analyzed by FlowJo v8 software (Tree Star, Ashland, Oregon).

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated with TRI reagent (Sigma-Aldrich). Isolated RNA was reverse transcribed with SuperScript II RNase reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen Life Technologies). Specific primer pairs for GAPDH (housekeeping gene) and CTLA4 were designed with Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems). Direct detection of the PCR product was monitored by measuring the increase in fluorescence caused by the binding of SYBR Green to dsDNA. Using 5 μl of cDNA, 5 μl of primer, and 10 μl of SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) per well, the gene-specific PCR products were measured continuously by means of a GeneAmp 5700 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) during 40 cycles. The threshold cycle of each target product was determined and set in relation to the amplification plot of GAPDH. The difference in threshold cycle values of two genes was used to calculate the fold difference as previously described.

Cloning of the CTLA4 promoter and construction of deletion constructs

The mouse CTLA4 promoter containing −1221 bp from the transcription start site was cloned into the pXP2 basic vector, which contains the luciferase reporter gene, as described previously (19). The luciferase construct that contains the 5′ deletion constructs –335 (p335) was sequenced in both directions by dideoxy sequencing (19).

Transfections and reporter gene assays

CTLA4 promoter luciferase reporter constructs (described above; 2 μg) and β-galactosidase reporter gene (pGK; 1 μg) were added to 2 × 106 EL4 cells resuspended in 100 μl of Nucleofector solution (Amaxa Biosystems) and electroporated using the C-9 program of the Nucleofector. After 24 h, cells were lysed in reporter lysis buffer (Promega). Then, 10 μl of the cell lysate was mixed with 100 μl of luciferase assay reagent (Promega) and luciferase activity was measured by a luminometer (Turner BioSystems). Luciferase activity was normalized for transfection efficiency by β-galactosidase activity measured with Galacto-light systems according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Applied Biosystems). Fold activation was calculated as the ratio of luciferase vs β-galactosidase activity.

Statistics

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed by GraphPad Prism software. Bonferroni correction for statistical adjustment of the p-value for multiple comparisons was applied as a post-hoc analysis. Data are reported as means ± SEM. Statistical significance was defined by p < 0.05.

Results

SP-D decreases allergen induced immune responses

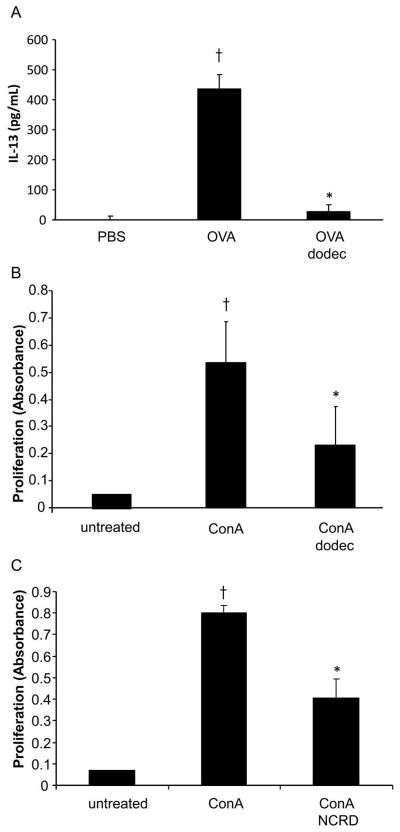

We asked whether administration of SP-D, using full length SP-D dodecamers (dodec), would impact allergic immune responses in vivo. We examined a murine model of allergen OVA induced pulmonary inflammation (Fig. 1, schema). As expected, OVA sensitized and challenged mice exhibited a significant increase in BAL IL-13 when compared with PBS control mice (p < 0.05; Fig. 2A). Administration of SP-D dodec significantly decreased allergen-induced BAL IL-13 (p < 0.05; Fig. 2A).

Figure 1. Schema of a murine model of allergen induced responses.

Wild type (BALB/c) mice received allergen ovalbumin (OVA) or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with adjuvant aluminum hydroxide (alum) by intraperitoneal (i.p.) sensitization on days 0 and 7. Mice were challenged with OVA or PBS by aerosol on days 14 to 20 and harvested on day 21. In separate experiments, SP-D (either dodec or NCRD) was administered intratracheally (i.t.) (3 μg) on days 13, 14 and 19. In additional experiments, anti-CTLA4 antibody (aCTLA4) or control Ig was injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) on day -1 prior to allergen sensitization.

Figure 2. SP-D decreases allergen-induced IL-13 in vivo and lymphocyte proliferation in vitro.

A, Mice (BALB/c) were sensitized and challenged with allergen OVA as described in Methods. Full length SP-D (dodec) was administered intratracheally (3 μg) on days 13, 14 and 19. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was harvested on day 21 for analysis of IL-13 cytokine by ELISA. Data is shown as geometric mean ± SEM (n = 6/group for IL-13). † OVA vs PBS; * OVA dodec vs OVA (p < 0.05). B and C, Murine splenocytes (BALB/c) were stimulated with mitogen Concanavalin A (ConA, 1 μg/ml) for 12 hours, and treated with dodec or SP-D NCRD (10 μg/ml) for 24 hours. Proliferation was measured by using BrdU labeling. Values are means ± SEM. † ConA vs untreated (p < 0.05); * ConA dodec or ConA NCRD vs ConA (p < 0.05).

SP-D and T cell interactions

SP-D dodec and SP-D NCRD decreases lymphocyte activation

T cells play a critical role in asthma pathogenesis (20). To investigate whether SP-D would affect T cell function, two forms of SP-D, full length SP-D dodec and a shorter fragment of SP-D containing neck and carbohydrate recognition domain (NCRD) were tested in lymphocyte proliferation. Both SP-D dodec and NCRD significantly decreased lymphocytic proliferation in spleen cells activated with mitogen Concanavalin A (p < 0.05; Fig. 2, B and C).

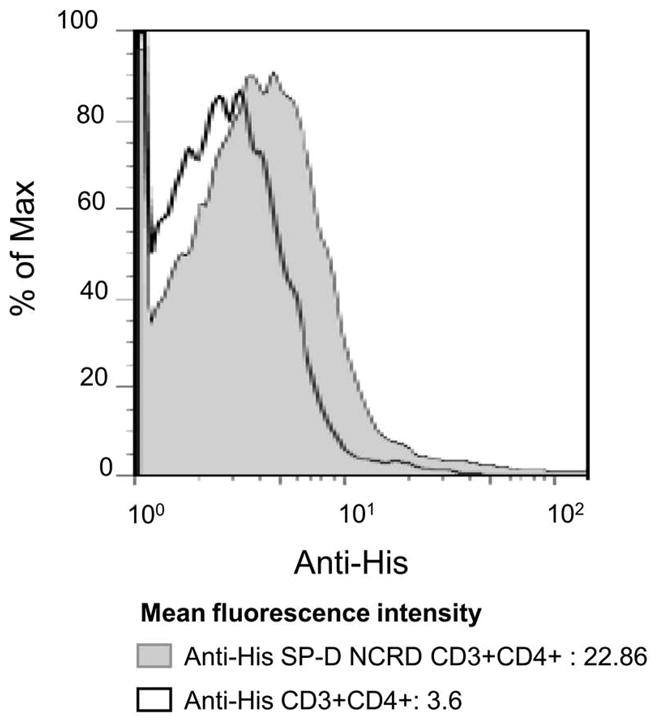

SP-D NCRD interacts with murine T cells

We next asked whether SP-D NCRD might interact with T cells. SP-D NCRD fusion protein (as described in Methods) contains a His-tag, a fusion protein useful for tracking binding to cells. When His-tagged SP-D NCRD was incubated with spleen cells, a small increase of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) signal was detected by flow cytometry in CD3+CD4+ murine T cells, suggesting that SP-D NCRD may interact with T cells (Fig. 3). The mean fluorescence intensities (MFI) were 22.86 and 3.6, respectively. In the absence of SP-D NCRD, no binding of the antibody to CD3+CD4+ T cells was observed, supporting the concept that SP-D NCRD may bind to CD3+CD4+ T cells.

Figure 3. SP-D NCRD interacts with T cells.

Murine spleen cells (BALB/c) incubated with or without SP-D NCRD containing a 6X His Tag (2 μg/ml) were stained with anti-CD3, anti-CD4 and anti-His antibodies. The binding of His-tagged SP-D NCRD to spleen cells was assessed by flow cytometry in the CD3+CD4+ T cells. When His-tagged SP-D NCRD incubated with spleen cells, higher levels of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) signal were detected by flow cytometry (gray tinted histogram) comparing with untreated cells (black lined histogram). The figure is representative of 3 independent experiments.

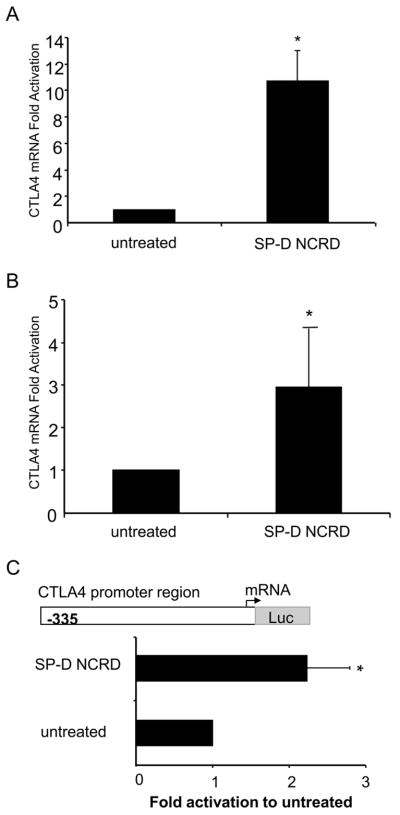

SP-D NCRD induces CTLA4 promoter activation and transcription in T cells

Based on SP-D suppression of T cell activation, we evaluated the SP-D NCRD modulation of T cell markers. We focused on CTLA4, a negative regulator of T cell activation, found primarily in T cells. Spleen cells and T cells (EL4) were activated with mitogen ConA and treated with SP-D NCRD. In primary spleen cells, SP-D NCRD augmented the levels of CTLA4 mRNA (11-fold relative to untreated, p < 0.05) (Fig. 4A). Also, SP-D NCRD increased the levels of CTLA4 mRNA in T cells (3-fold relative to untreated, p < 0.05) (Fig. 4B). We have previously shown that adaptive stimuli increase CTLA4 gene expression and is regulated at the transcriptional level (21). We asked whether SP-D NCRD would influence CTLA4 transcriptional activation. We examined a CTLA4 promoter construct consisting of 335 base pairs (p335) relative to the transcription start site. SP-D NCRD induced CTLA4 promoter region activation, as determined by a significant increase in the luciferase activity relative to untreated (p < 0.05; Fig. 4C).

Figure 4. SP-D NCRD increases CTLA4 mRNA levels and promoter activity in T cells.

(A) Murine spleen cells (BALB/c) and (B) Murine T cells (EL4) were treated with SP-D NCRD (500 ng/ml) for 24 hours. RNA was purified and analyzed by real-time PCR. Data are expressed as fold difference to untreated murine spleen cells and T cells. Values are means ± SEM for spleen cells (n = 3) and ± SEM for T cells (n = 6). * untreated vs SP-D NCRD (p < 0.05). (C) T cells (EL4) were transfected by nucleofection with a CTLA4 promoter luciferase (luc)-based reporter construct (−335 relative to the transcription starting site) and β-galactosidade reporter gene (PGK) construct. After 24 hours, cells were treated with SP-D NCRD (500 ng/ml) for 24 hours followed by analysis of reporter gene expression using a luminometer. Fold activation of Relative Light Unit (RLU) is calculated as the ratio of luciferase activity vs β-galactosidade activity. Fold induction is the ratio SP-D NCRD treated to untreated T cells. Data are means ± SEM (n = 4). * untreated vs SP-D NCRD (p < 0.05).

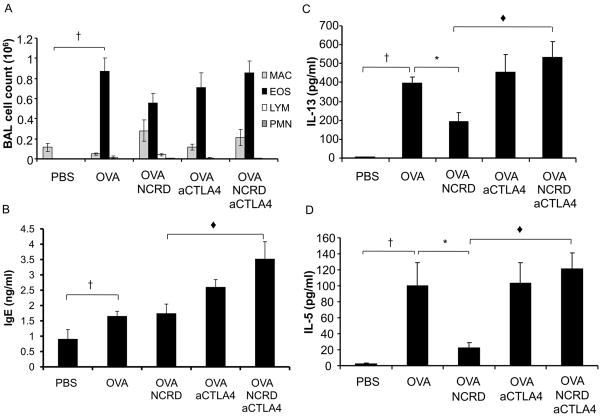

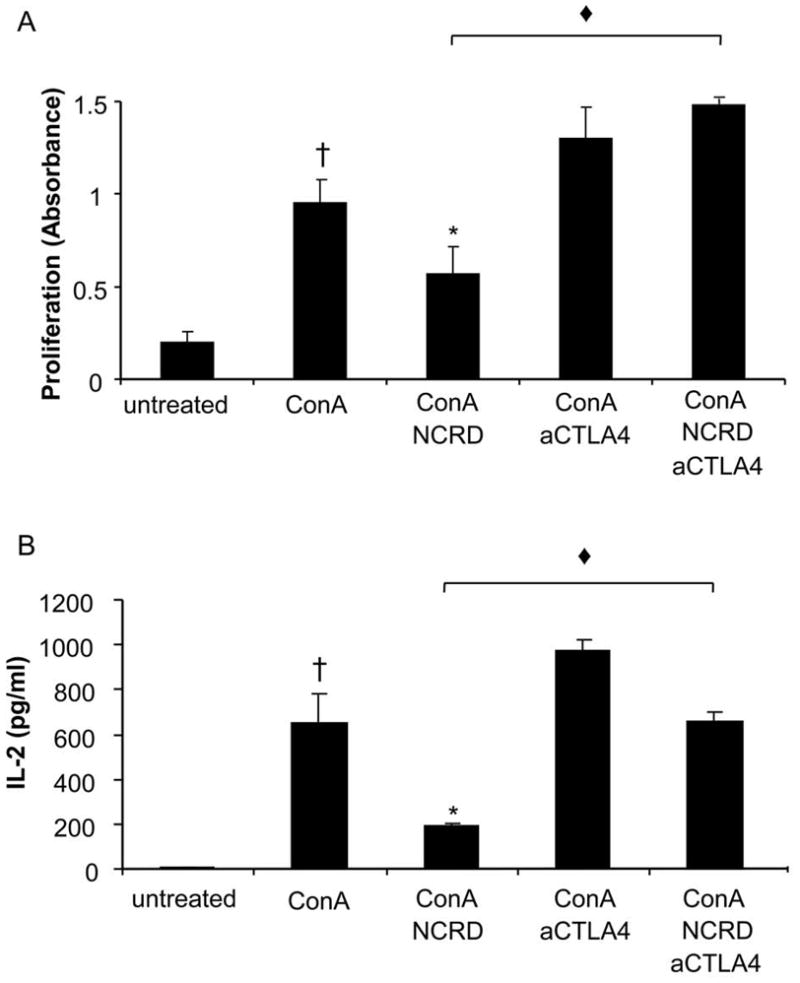

Administration of aCTLA4: Influence on SP-D NCRD mediated immune responses

We next asked whether SP-D repression of allergic responses might be mediated by CTLA4. We examined the effect of anti-CTLA4 antibody (aCTLA4) on SP-D NCRD mediated lymphoproliferation and IL-2 secretion (Fig. 5). SP-D NCRD significantly decreases lymphoproliferation and IL-2 production from activated splenocytes (p < 0.05; Fig. 5, A and B). In contrast, SP-D NCRD no longer decreases lymphoproliferation and IL-2 production in the presence of aCTLA4. The abrogation of the ability of SP-D NCRD to inhibit lymphoproliferation and IL-2 production suggests that SP-D may decrease T cell activation through modulation of CTLA4 pathways.

Figure 5. SP-D NCRD no longer decreases lymphoproliferation and IL-2 when aCTLA4 is administered.

Murine spleen cells (BALB/c) were activated with ConA (1 μg/ml) for 12 hours and treated with SP-D NCRD (10 μg/ml) for 24 hours. An anti-CTLA4 blocking antibody (aCTLA4, 10 μg) was administered (i.p.) 12 hours before SP-D NCRD administration. Proliferation was measured by using BrdU labeling (A) and supernatant was assayed for IL-2 by bead-based multiplex sandwich immunoassay (B). Values are means ± SEM. † ConA vs untreated (p < 0.05); * ConA NCRD vs ConA (p < 0.05); ◆ConA NCRD aCTLA4 vs ConA NCRD (p < 0.05).

To test the effect of CTLA4 blockade on SP-D modulation of allergic responses in vivo, we administered aCTLA4 to allergen sensitized and challenged mice (Fig. 6). Administration of aCTLA4 without SP-D NCRD resulted in maintained allergic responses (Fig. 6), which was not modified by control Ig (data not shown). aCTLA4 administration at different time points (i.e., day-1/7 and day -1/13) had similar effects (data not shown). Administration of aCTLA4 with SP-D NCRD results in maintained or enhanced allergic induced eosinophilia or IgE (Fig. 6, A and B, respectively). SP-D NCRD administration significantly decreased allergen induced IL-13 and IL-5 (Fig. 6, C and D). Administration of aCTLA4 with SP-D NCRD did not result in decreased allergen induced IL-13 and IL-5 (Fig. 6, C and D), in contrast to what was observed with administration of SP-D NCRD alone.

Figure 6. SP-D NCRD no longer decreases allergen induced responses when aCTLA4 is administered.

Mice (BALB/c) were sensitized and challenged with allergen OVA. aCTLA4 (100 μg) or control antibody hamster Ig (100 μg) was administered i.p. at day –1, and SP-D NCRD was administered i.t. at days 13, 14 and 19. Cell counts were determined by differential staining of cells isolated from BAL fluid. Total serum IgE and BAL IL-13 cytokine were measured by ELISA. BAL IL-5 was assayed by bead-based multiplex sandwich immunoassay. (A) BAL eosinophilia; (B) Serum IgE; (C) BAL IL-13; (D) BAL IL-5. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 6–15 per group). †OVA vs PBS (p < 0.05), *OVA NCRD vs OVA (p < 0.05); ◆OVA NCRD aCTLA4 vs OVA NCRD (p < 0.05).

Discussion

An increase in allergic inflammatory diseases, including asthma, has necessitated increased investigation of allergic immune mechanisms. In addition to analysis of adaptive antigen dependent immunity in asthma, recent scrutiny has turned to innate non antigen dependent immunity. Specifically, SP-D is critical for innate defense against exogenous molecules derived from pathogens, and may be crucial for immunomodulation of adaptive immune responses (3, 5). In this study, we investigated the role of SP-D in adaptive allergic responses. We administered SP-D in vivo and in vitro using two forms of SP-D, and focused on a fragment of SP-D containing the functionally important C-terminal lectin domains (SP-D NCRD). SP-D decreased lymphoproliferation and IL-2 cytokine production as well as allergen-induced cytokine levels. Our data suggest that SP-D may modulate T cell function through CTLA4, a negative regulator of T cell activation (19, 21). SP-D regulated CTLA4 transcription in T cells. SP-D no longer decreased lymphoproliferation and IL-2 cytokine production when CTLA4 signals were abrogated. Furthermore, SP-D no longer decreased allergen induced responses when CTLA4 was inhibited in a murine allergic model. Taken together, these data suggest that SP-D modulation of allergic responses may be mediated by CTLA4.

We have previously found that SP-D deficient mice exhibit enhanced allergic responses, consistent with an immunosuppressive role (3). Allergic and other inflammatory responses are accompanied by increased SP-D (5, 6). Immunostaining of SP-D is also increased in nonciliated epithelial cells of noncartilaginous airways in a murine allergic model in three murine strains (5). In our study, SP-D administration to OVA sensitized and challenged mice decreased allergic responses. One exception to SP-D effects is that allergen induced IgE was not decreased by SP-D in our model whereas other groups have shown that SP-D can reduce allergen induced IgE (10, 22, 23). Whether use of different forms of SP-D (i.e., recombinant 60kDa fragment of human SP-D (rfh SP-D), purified native SP-D), different allergens (i.e., house dust mite (Der 9), Aspergillus fumigates (Afu)), or mouse strains (i.e., C57BL/6) may differentially impact IgE remains to be determined. There are also prior examples of the divergent effects on allergic responses by different reagents, which may be due to timing or systemic effects (24). Related to SP-D impact on allergic responses, Haczku et al. showed that allergen induced SP-D is IL-4/IL-13-dependent, preventing further activation of sensitized T cells (6). SP-D administration in our study significantly decreased allergic induced IL-13. SP-D also decreases IL-4, albeit not significantly (data not shown). SP-D is not induced in lymphocyte deficient recombinase-activating gene-deficient (RAG) mice, suggesting that the allergen induced increase of SP-D requires T or B lymphocytes (5).

Activation of lymphocytes is important during allergic immune responses. Several studies have shown that SP-D inhibits lymphocyte activation. SP-D deficient mice exhibit a persistent T cell activation (25). Full length recombinant rat SP-D dodecamers inhibit IL-2 production and proliferation of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) stimulated by lectin and anti-CD3 (26). Native SP-D suppresses lymphocyte proliferation of PBMCs from children with asthma in the late phase of bronchial inflammation (12). SP-D can directly suppress CD3+/CD4+ T cell proliferation without accessory cells (13). SP-D and T cell interactions have been previously analyzed using SP-D purified from human BAL incubated with a T cell line (Jurket) (27). SP-D appeared to interact with late apoptotic cells in a Ca2+ and maltose independent fasion, suggesting that the lectin site of SP-D was not involved. In this study, we used a SP-D NCRD fusion protein containing a His tag useful for tracking binding to cells and analyzed its binding with murine spleen cells. We persistently observed an obvious but small increase in fluorescence intensity. In the absence of SP-D NCRD, no binding of the antibody to CD3+CD4+ T cells was observed. SP-D NCRD appeared to bind to CD3+CD4+ T cells in vitro. The specificity of the binding and whether these interactions are direct or indirect require further investigation. The results are consistent with the concept that SP-D may suppress lymphocyte proliferation by interaction with T cells. These data suggest a novel mechanism by which SP-D may bypass the middlemen, e.g. antigen-presenting cells, and perhaps modulate T cells directly.

To investigate the potential pathways by which SP-D NCRD modulates T cell activation, we focused on CTLA4, a negative regulator of T cells. Previous studies indicate that polymorphisms in the CTLA4 gene are associated with asthma, bronchial hyperresponsiveness and increase of serum IgE (28–30). A polymorphism found in the CTLA4 promoter (-318C/T) is associated with increase of total serum IgE in patients with asthma (30). Polymorphisms identified in CTLA4 gene are also involved in the regulation of IgE levels and development of allergic asthma (29, 30). Since CTLA4 is involved in maintaining the balance of the immune system, the disruption of CTLA4 signaling transduction by either gene polymorphisms or blockade may foster allergic inflammation. We and others have shown that blockade of CTLA4 signals in vivo enhances or maintains airway inflammation (31, 32). Overall, these findings suggest that modulation of CTLA4 signaling may impact T cells responses, thus modulating pulmonary allergic inflammation.

T cell activation is an adaptive immune response that plays an essential role in allergic inflammation. We previously showed that modulation of adaptive immunity can regulate CTLA4 function and decrease allergic inflammatory responses in vivo (16). We tested whether SP-D, an innate molecule, regulates CTLA4 signaling in T cells. Inhibition of CTLA4 signaling affected SP-D NCRD ability to abrogate T cell activation. CTLA4 activation during T cell differentiation inhibits polarization of naïve CD4+ T cells to Th2 cell subset as well as Th2 cytokine production (33–35). These data are consistent with our findings that SP-D no longer decreases allergen induced immune responses when CTLA4 signaling is blocked. One interpretation is that SP-D may interact with activated T cells and enhance CTLA4 activation, leading to suppression of T cell cytokine production (33). Overall, SP-D mediated modulation of CTLA4 may be a novel immune regulatory pathway that decreases allergic inflammatory responses.

We have previously determined regulatory elements in the CTLA4 promoter for adaptive induced increase of CTLA4 transcription (19, 21). We identified a 335-bp upstream CTLA4 promoter region that is important for inducible CTLA4 expression in activated T cells (21). Analysis of this CTLA4 upstream promoter region (−335 to −62) reveals potential DNA binding sites for NFAT, NF-κB, AP-1, as well as NF-IL2A (Oct-1) and IL6REBP (16, 21). Interestingly, SP-D also increases the same 335-bp regulatory region of the CTLA4 promoter in T cells as is increased by adaptive stimuli (Fig. 4C). SP-D may interact with T cells, and CTLA4 expression appears to be induced after this interaction. SP-D NCRD has been shown to bind to the extracellular domains of soluble forms of recombinant TLR2 (sTLR2) and TLR4 (sTLR4), with a different mechanism than its binding to phosphatidylinositol and lipopolysaccharide (36). Prior analysis of transcription factors suggests potential pathways for SP-D induced CTLA4 expression. SP-D negatively regulates NF-κB in alveolar macrophage (37). SP-D also suppresses Der p-induced activation of macrophages through suppression of the CD14/TLR signalling pathway (38). NFAT binding induces CTLA4 expression (19, 39, 40). We have previously shown that a TLR2 agonist induces CTLA4 (41). TLR4 signaling may increase CTLA4 in T cells as CTLA4 is decreased in TLR4-defective CD4+ T cells (42). We speculate that SP-D may bind to known (TLR2/TLR4) or unknown receptors, perhaps through its CRD domain, which leads to modification of transcription factor binding (e.g., NF-κB or NFAT) to the CTLA4 promoter. The specific pathways by which SP-D induces CTLA4 remains to be determined.

SP-D inhibits allergen-induced pulmonary responses, and increases CTLA4 mRNA levels and promoter activation in T cells. Blockade of CTLA4 decreases the ability of SP-D to inhibit allergen induced immune responses. Taken together, these results indicate that SP-D regulates CTLA4 and modulates allergen induced pulmonary inflammation. Future investigations regarding SP-D modulation of T cells may be applicable to distinct therapeutic approaches for allergic diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Takeshi Nakajima for assistance with flow cytometry, and Dr. Hong Zhen He for help with sample preparation.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant 5R01HL081663-05.

Abbreviations used in this paper: SP-D, surfactant protein D; NCRD, neck and carbohydrate recognition domain; aCTLA4, anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 mAb.

References

- 1.Crouch E, Parghi D, Kuan SF, Persson A. Surfactant protein D: subcellular localization in nonciliated bronchiolar epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:L60–66. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1992.263.1.L60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crouch E, Wright JR. Surfactant proteins a and d and pulmonary host defense. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;63:521–554. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schaub B, Westlake RM, He H, Arestides R, Haley KJ, Campo M, Velasco G, Bellou A, Hawgood S, Poulain FR, Perkins DL, Finn PW. Surfactant protein D deficiency influences allergic immune responses. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:1819–1826. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.02068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang JY, Shieh CC, Yu CK, Lei HY. Allergen-induced bronchial inflammation is associated with decreased levels of surfactant proteins A and D in a murine model of asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31:652–662. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haley KJ, Ciota A, Contreras JP, Boothby MR, Perkins DL, Finn PW. Alterations in lung collectins in an adaptive allergic immune response. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282:L573–584. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00117.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haczku A, Cao Y, Vass G, Kierstein S, Nath P, Atochina-Vasserman EN, Scanlon ST, Li L, Griswold DE, Chung KF, Poulain FR, Hawgood S, Beers MF, Crouch EC. IL-4 and IL-13 form a negative feedback circuit with surfactant protein-D in the allergic airway response. J Immunol. 2006;176:3557–3565. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kasper M, Sims G, Koslowski R, Kuss H, Thuemmler M, Fehrenbach H, Auten RL. Increased surfactant protein D in rat airway goblet and Clara cells during ovalbumin-induced allergic airway inflammation. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002;32:1251–1258. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2745.2002.01423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng G, Ueda T, Numao T, Kuroki Y, Nakajima H, Fukushima Y, Motojima S, Fukuda T. Increased levels of surfactant protein A and D in bronchoalveolar lavage fluids in patients with bronchial asthma. Eur Respir J. 2000;16:831–835. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00.16583100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koopmans JG, van der Zee JS, Krop EJ, Lopuhaa CE, Jansen HM, Batenburg JJ. Serum surfactant protein D is elevated in allergic patients. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:1827–1833. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.02083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madan T, Kishore U, Singh M, Strong P, Clark H, Hussain EM, Reid KB, Sarma PU. Surfactant proteins A and D protect mice against pulmonary hypersensitivity induced by Aspergillus fumigatus antigens and allergens. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:467–475. doi: 10.1172/JCI10124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kishor U, Madan T, Sarma PU, Singh M, Urban BC, Reid KB. Protective roles of pulmonary surfactant proteins, SP-A and SP-D, against lung allergy and infection caused by Aspergillus fumigatus. Immunobiology. 2002;205:610–618. doi: 10.1078/0171-2985-00158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang JY, Shieh CC, You PF, Lei HY, Reid KB. Inhibitory effect of pulmonary surfactant proteins A and D on allergen-induced lymphocyte proliferation and histamine release in children with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:510–518. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.2.9709111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borron PJ, Mostaghel EA, Doyle C, Walsh ES, McHeyzer-Williams MG, Wright JR. Pulmonary surfactant proteins A and D directly suppress CD3+/CD4+ cell function: evidence for two shared mechanisms. J Immunol. 2002;169:5844–5850. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linsley PS, Brady W, Urnes M, Grosmaire LS, Damle NK, Ledbetter JA. CTLA-4 is a second receptor for the B cell activation antigen B7. J Exp Med. 1991;174:561–569. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.3.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walunas TL, Lenschow DJ, Bakker CY, Linsley PS, Freeman GJ, Green JM, Thompson CB, Bluestone JA. CTLA-4 can function as a negative regulator of T cell activation. Immunity. 1994;1:405–413. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jen KY, Campo M, He H, Makani SS, Velasco G, Rothstein DM, Perkins DL, Finn PW. CD45RB ligation inhibits allergic pulmonary inflammation by inducing CTLA4 transcription. J Immunol. 2007;179:4212–4218. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.4212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crouch E, Tu Y, Briner D, McDonald B, Smith K, Holmskov U, Hartshorn K. Ligand specificity of human surfactant protein D: expression of a mutant trimeric collectin that shows enhanced interactions with influenza A virus. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17046–17056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413932200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang H, Head J, Kosma P, Brade H, Muller-Loennies S, Sheikh S, McDonald B, Smith K, Cafarella T, Seaton B, Crouch E. Recognition of heptoses and the inner core of bacterial lipopolysaccharides by surfactant protein d. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2008;47:710–720. doi: 10.1021/bi7020553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finn PW, He H, Wang Y, Wang Z, Guan G, Listman J, Perkins DL. Synergistic induction of CTLA-4 expression by costimulation with TCR plus CD28 signals mediated by increased transcription and messenger ribonucleic acid stability. J Immunol. 1997;158:4074–4081. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mamessier E, Nieves A, Lorec AM, Dupuy P, Pinot D, Pinet C, Vervloet D, Magnan A. T-cell activation during exacerbations: a longitudinal study in refractory asthma. Allergy. 2008;63:1202–1210. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perkins D, Wang Z, Donovan C, He H, Mark D, Guan G, Wang Y, Walunas T, Bluestone J, Listman J, Finn PW. Regulation of CTLA-4 expression during T cell activation. J Immunol. 1996;156:4154–4159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strong P, Townsend P, Mackay R, Reid KB, Clark HW. A recombinant fragment of human SP-D reduces allergic responses in mice sensitized to house dust miteallergens. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;134:181–187. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu CF, Chen YL, Shieh CC, Yu CK, Reid KB, Wang JY. Therapeutic effect of surfactant protein D in allergic inflammation of mite-sensitized mice. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:515–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleming CM, He H, Ciota A, Perkins D, Finn PW. Administration of pentoxifylline during allergen sensitization dissociates pulmonary allergic inflammation from airway hyperresponsiveness. J Immunol. 2001;167:1703–1711. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fisher JH, Larson J, Cool C, Dow SW. Lymphocyte activation in the lungs of SP-D null mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;27:24–33. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.27.1.4563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borron PJ, Crouch EC, Lewis JF, Wright JR, Possmayer F, Fraher LJ. Recombinant rat surfactant-associated protein D inhibits human T lymphocyte proliferation and IL-2 production. J Immunol. 1998;161:4599–4603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jakel A, Clark H, Reid KB, Sim RB. The human lung surfactant proteins A (SP-A) and D (SP-D) interact with apoptotic target cells by different binding mechanisms. Immunobiology. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hizawa N, Yamaguchi E, Jinushi E, Konno S, Kawakami Y, Nishimura M. Increased total serum IgE levels in patients with asthma and promoter polymorphisms at CTLA4 and FCER1B. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:74–79. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.116119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howard TD, Postma DS, Hawkins GA, Koppelman GH, Zheng SL, Wysong AK, Xu J, Meyers DA, Bleecker ER. Fine mapping of an IgE-controlling gene on chromosome 2q: Analysis of CTLA4 and CD28. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110:743–751. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.128723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munthe-Kaas MC, Carlsen KH, Helms PJ, Gerritsen J, Whyte M, Feijen M, Skinningsrud B, Main M, Kwong GN, Lie BA, Lodrup Carlsen KC, Undlien DE. CTLA-4 polymorphisms in allergy and asthma and the TH1/TH2 paradigm. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hellings PW, Vandenberghe P, Kasran A, Coorevits L, Overbergh L, Mathieu C, Ceuppens JL. Blockade of CTLA-4 enhances allergic sensitization and eosinophilic airway inflammation in genetically predisposed mice. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:585–594. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200202)32:2<585::AID-IMMU585>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alenmyr L, Matheu V, Uller L, Greiff L, Malm-Erjefalt M, Ljunggren HG, Persson CG, Korsgren M. Blockade of CTLA-4 promotes airway inflammation in naive mice exposed to aerosolized allergen but fails to prevent inhalation tolerance. Scand J Immunol. 2005;62:437–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2005.01682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oosterwegel MA, Mandelbrot DA, Boyd SD, Lorsbach RB, Jarrett DY, Abbas AK, Sharpe AH. The role of CTLA-4 in regulating Th2 differentiation. J Immunol. 1999;163:2634–2639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ubaldi V, Gatta L, Pace L, Doria G, Pioli C. CTLA-4 engagement inhibits Th2 but not Th1 cell polarisation. Clin Dev Immunol. 2003;10:13–17. doi: 10.1080/10446670310001598519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alegre ML, Shiels H, Thompson CB, Gajewski TF. Expression and function of CTLA-4 in Th1 and Th2 cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:3347–3356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohya M, Nishitani C, Sano H, Yamada C, Mitsuzawa H, Shimizu T, Saito T, Smith K, Crouch E, Kuroki Y. Human pulmonary surfactant protein D binds the extracellular domains of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 through the carbohydrate recognition domain by a mechanism different from its binding to phosphatidylinositol and lipopolysaccharide. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2006;45:8657–8664. doi: 10.1021/bi060176z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshida M, Korfhagen TR, Whitsett JA. Surfactant protein D regulates NF-kappa B and matrix metalloproteinase production in alveolar macrophages via oxidant-sensitive pathways. J Immunol. 2001;166:7514–7519. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu CF, Rivere M, Huang HJ, Puzo G, Wang JY. Surfactant protein D inhibits mite-induced alveolar macrophage and dendritic cell activations through TLR signalling and DC-SIGN expression. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40:111–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller RE, Fayen JD, Mohammad SF, Stein K, Kadereit S, Woods KD, Sramkoski RM, Jacobberger JW, Templeton D, Shurin SB, Laughlin MJ. Reduced CTLA-4 protein and messenger RNA expression in umbilical cord blood T lymphocytes. Exp Hematol. 2002;30:738–744. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00831-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gibson HM, Hedgcock CJ, Aufiero BM, Wilson AJ, Hafner MS, Tsokos GC, Wong HK. Induction of the CTLA-4 gene in human lymphocytes is dependent on NFAT binding the proximal promoter. J Immunol. 2007;179:3831–3840. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schaub B, Campo M, He H, Perkins D, Gillman MW, Gold DR, Weiss S, Lieberman E, Finn PW. Neonatal immune responses to TLR2 stimulation: influence of maternal atopy on Foxp3 and IL-10 expression. Respir Res. 2006;7:40. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frisancho-Kiss S, Davis SE, Nyland JF, Frisancho JA, Cihakova D, Barrett MA, Rose NR, Fairweather D. Cutting edge: cross-regulation by TLR4 and T cell Ig mucin-3 determines sex differences in inflammatory heart disease. J Immunol. 2007;178:6710–6714. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]