Overview

Since its isolation in Uganda in 1937, West Nile virus (WNV) has been responsible for thousands of cases of morbidity and mortality in birds, horses, and humans. Historically, epidemics were localized to Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and parts of Asia, and primarily caused a mild febrile illness in humans. However, in the late 1990’s, the virus became more virulent and expanded its geographical range to North America. In humans, the clinical presentation ranges from asymptomatic (approximately 80% of infections) to encephalitis/paralysis and death (less than 1% of infections). There is no FDA-licensed vaccine for human use, and the only recommended treatment is supportive care. Individuals that survive infection often have a long recovery period. This article will review the current literature summarizing the molecular virology, epidemiology, clinical manifestations, pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, immunology, and protective measures against WNV and WNV infections in humans.

Keywords: West Nile virus, flavivirus, infection, pathogenesis, diagnosis

Virology and Molecular Biology of WNV

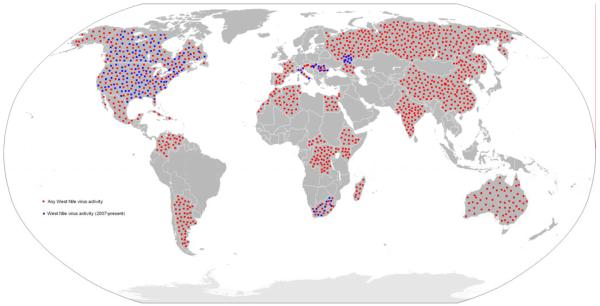

West Nile virus is a positive-stranded RNA virus in the family Flaviviridae (genus Flavivirus), which includes other human pathogens such as dengue, yellow fever, and Japanese encephalitis viruses [1, 2]. The virion consists of an envelope surrounding an icosahedral capsid of approximately 50 nm in size. The ~11 kilobase genome encodes a single open reading frame, which is flanked by 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTR). The approximately 3000 amino acid polyprotein is cleaved into ten proteins by cellular and viral proteases (Figure 1). Three of these proteins are the structural components required for virion formation (capsid protein (C)) and assembly into viral particles (premembrane (prM) and envelope proteins (E)). The other seven viral proteins are nonstructural (NS) proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B and NS5) and are all necessary for genome replication. NS3 contains an ATP-dependent helicase, and in conjunction with the NS2B protein, a serine protease, which is required for virus polyprotein processing. NS5 is a methyltransferase and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (NS5). The other NS proteins are small, generally hydrophobic proteins of disparate functions. NS1 is a secreted glycoprotein implicated in immune evasion [3]. NS2A plays a role in virus assembly as well as inhibiting IFN-β promoter activation [4, 5]. NS4A is responsible for a rapid expansion and modification of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) that helps establish replication domains [5-8]. NS4B blocks the IFN response [9-12]. Importantly, all the NS proteins appear to be necessary for efficient replication [13].

Figure 1. Schematic of WNV genome.

A representation of the WNV genome including the 3 structural proteins that make up virion particle and the 7 non-structural proteins necessary for virus replication and immune evasion.

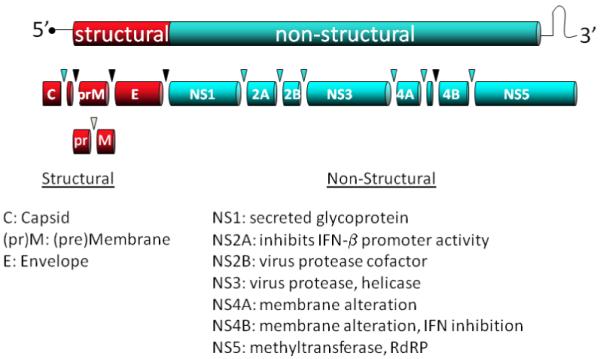

The flavivirus life cycle consists of 4 principal stages: attachment/entry, translation, replication, and assembly/egress (reviewed in {Clyde, 2006 #103;Lindenbach, 2001 #199}).WNV enters cells via receptor-mediated endocytosis, and is transported into endosomes. The WNV receptor is unknown. A number of cell-surface proteins are potential WNV receptors (DC-SIGN, Integrin alpha-v beta-3) [14-16] and the receptor required for WNV binding and entry may vary by cell type. Acidification of the endosomal compartment causes a conformational change in the E protein, resulting in fusion of the viral and endosomal membranes and release of the virus nucleocapsid into the cytoplasm [17, 18]. The viral RNA is translated and the polyprotein is processed. Genome replication is carried out in specific domains established by the viral proteins [19, 20]. As stated above, viral proteins cause massive expansion and modification of the ER. Two domains are important replication and virus protein processing: vesicle packets (VP) and convoluted membranes (CM), respectively [20-25] (Figure 2). Following replication and translation, genomes are packaged into virions, which mature through the ER-Golgi secretion pathway [19, 20, 26, 27]. Progeny viruses are released by exocytosis.

Figure 2. Scanned images are of West Nile virus isolated from brain tissue from an infected crow.

The tissue was cultured in a Vero cell for a 3-day incubation period. The Vero cells were fixed in glutaraldehyde, dehyrated, placed in an Epon resin, thin sectioned, placed on a copper grid, and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. The grids were then placed in the electron microscope and viewed. Total magnifications, image 65,625x. Image courtesy of CDC (Bruce Cropp, Microbiologist, Division of Vector-Borne Infectious Diseases).

Phylogeny

The most current phylogenetic studies (based upon sequences of entire or partial genome sequences) indicate five lineages of WNV [28]. The virus that entered North America belongs to lineage I (clade Ia). This lineage also contains viruses found in Europe, the Middle East and Africa. The genome of Kunjin virus, the Australian strain of WNV, also groups within lineage I (clade Ib). Lineage II is comprised of WNV mainly of African origin. Although there are exceptions, in general, lineage I (clade Ia) viruses can cause severe human neurologic disease whereas lineage I (clade Ib), and lineage II viruses generally cause a mild, self-limiting disease. Relatively little is known about the viruses that comprise lineages III, IV and V.

Epidemiology

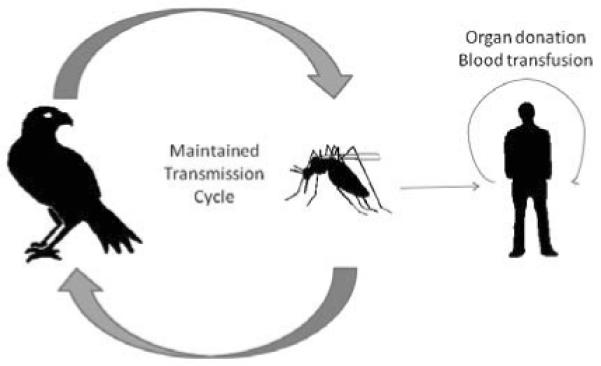

WNV is maintained in nature in a cycle between birds and mosquitoes (Figure 3). Although many different species of mosquito are capable of maintaining this cycle, the Culex species play the largest role in natural transmission (Figure 4). Not all infected mosquitoes preferentially feed upon birds, which can lead to other animals including humans becoming infected. Humans (and horses) are incidental or “dead-end” hosts in this cycle since the concentration of virus within the blood (viremia) is insufficient to infect a feeding naïve mosquito. Other natural modes of WNV transmission have been documented, but occur rarely. WNV transmission can occur between infected mother and newborn via the intrauterine route [29-31]or possibly by breast-feeding [32]. A recent study of pregnant women who became infected with WNV during the 2003-4 transmission in the United States suggested that adverse health side effects of the newborn infant due to WNV infection of the mother are rare, and those cases with infant illness/infection/mortality may be associated with WNV infection that occurred while the mother was infected within 1 month prepartem [33].

Figure 3. Diagram of the WNV transmission cycle.

The maintenance of WNV in nature depends upon many avian and mosquito species. Humans and other incidental hosts (like horses) become infected when WNV-infected mosquito takes a bloodmeal from them.

Figure 4. Culex mosquito.

The Culex species of mosquito is the most common vector of WNV. Photograph of Culex species mosquito feeding. Courtesy of USGS.

Within the human population, the virus can spread between individuals by more artificial means. In the early 2000’s, patients that received tainted blood or organs from viremic donors become infected [34-37]. These events highlighted the need to safeguard blood and organ donations from potentially viremic yet healthy donors, and relatively few infections via this route of transmission were reported since 2004.

The epidemiology of WNV is continuously changing. The virus was initially isolated from a febrile woman in Uganda in 1937 [38]. Since that time, few outbreaks of WNV in human or horse populations were recorded until the beginning of the 1990s. When disease was observed in humans, symptoms were typically mild and neurologic complications were rare {Murgue, 2001 #750; Hayes, 2001 #776}. Noteworthy exceptions during this time were outbreaks in Israel in the early 1950s and France in the 1960s, which were characterized by encephalitis in humans and horses. A series of outbreaks in the 1990s brought WNV into the spotlight; epidemics in Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, Italy, France, Romania, Israel, and Russia were associated with uncharacteristically severe human disease, including neurologic complications and death [39, 41-43]. In the summer of 1999, a cluster of patients with encephalitis in New York City signaled the entry of WNV into North America. The sequence of the New York 1999 strain of WNV is closest in identity to a viral isolate from Israel [44], but it is still a mystery how the virus traversed the Atlantic Ocean. In the past decade, there have been thousands of reported human cases of WNV disease (WN fever and WN encephalitis) accompanied by over a thousand deaths (Table 1). The geographic range of the virus currently extends north into Canada, west across all 48 contiguous states, and south into Mexico, the Caribbean, and Central and South America (Figure 5 and 6) {Blitvich, 2008 #876}. Since 2007, in addition to ongoing circulation of WNV in the Western Hemisphere, there have been outbreaks or isolations of WNV in Volograd (Russia) {Platonov, 2008 #877}, South Africa {Venter, 2009 #878}, Hungary {Krisztalovics, 2008 #879}, Romania {Popovici, 2008 #880}, and Italy {Rossini, 2008 #881}(Figure 5).

Table 1.

Summary of confirmed human cases of WN disease in the United States, 1999-2008a.

|

Year |

No. States Reportingb |

Total Cases |

Deaths | CFRc | Neurologic involvementd |

WN fevere |

Other symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 1 | 62 | 7 | 11.29% | 59 | 3 | 0 |

| 2000 | 3 | 21 | 2 | 9.52% | 19 | 2 | 0 |

| 2001 | 10 | 66 | 10 | 15.15% | 64 | 2 | 0 |

| 2002 | 39 +DCf | 4156 | 284 | 6.83% | 2946 | 1160 | 50 |

| 2003 | 45 + DC | 9862 | 264 | 2.68% | 2866 | 6830 | 166 |

| 2004 | 40 + DC | 2539 | 100 | 3.94% | 1142 | 1269 | 128 |

| 2005 | 43 + DC | 3000 | 119 | 3.97% | 1294 | 1607 | 99 |

| 2006 | 43 + DC | 4269 | 177 | 4.15% | 1459 | 2616 | 194 |

| 2007 | 43 | 3630 | 124 | 3.42% | 1217 | 2350 | 63 |

| 2008 | 45 + DC | 1356 | 44 | 3.24% | 687 | 624 | 45 |

data obtained from the CDC, accessed on May 13, 2009

the number of states reporting CDC-confirmed cases of WNV infections in humans

CFR= case fatality rate; determined as percentage of deaths from total CDC-confirmed reported cases

neurologic involvement is comprised of encephalitis, meningitis

WN fever; febrile illness with no neurologic involvement

DC= District of Columbia

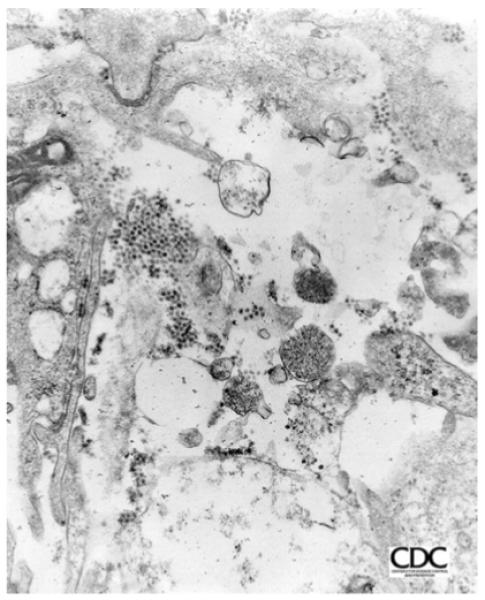

Figure 5. Distribution of WNV.

Countries with historic or recent (2007-present) WNV activity (isolations from mosquitoes, birds, horses or humans) are highlighted in red and blue, respectively.

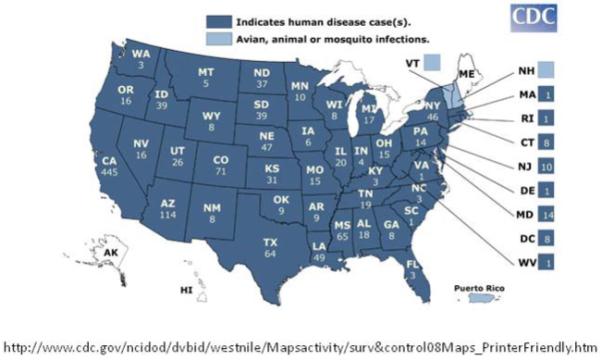

Figure 6.

The number of confirmed human cases of WNV disease in the United States in 2008. Courtesy of CDC.

In 2008 alone, there were 1338 cases of WNV disease reported to the CDC and resulted in 43 deaths within the United States (http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/westnile/surv&controlCaseCount08_detailed.htm).

Clinical presentation

It is difficult to accurately predict the incubation period of WNV in humans (time from mosquito bite/infection to the presentation of symptoms), but it is ~2-15 days [34, 45]. The majority (>80%) of WNV infections are asymptomatic. Symptomatic infections are primarily a mild, self-limiting febrile illness. However, approximately 1% of infected persons develop neurologic infections and disease. Most symptomatic patients exhibit mild illness with fever, sometimes associated with headache, myalgias, nausea and vomiting, and chills [34, 46-49]. Further, some patients briefly present papular rash on the arms, legs, or trunk. These symptoms follow relatively predictable pattern with illness generally lasting less than seven days. However, a number of patients experience severe fatigue and malaise during convalescence.

Approximately 5 percent of patients with symptomatic WNV infection develop neurologic disease. WNV neurologic symptoms include meningitis, encephalitis, and poliomyelitis-like disease, presented as acute flaccid paralysis [50]. WNV encephalitis and/or meningitis are characterized by rapid onset of headache, photophobia, back pain, confusion and continued fever. WNV poliomyelitis-like syndrome is characterized by acute onset of asymmetric weakness and absent reflexes without pain. Patients presenting with flaccid paralysis require further testing to determine nature and degree of disease. Diagnostic tests including cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination should be performed in order to differentiate WNV infection from stroke, myopathy, and Guillain-Barre Syndrome. Other clinical symptoms may include tremor, myoclonus, postural instability, bradykinesia, and signs of parkinsonism.

Pathogenesis

Understanding the full range of WNV pathogenesis in humans has been difficult, mainly due to the difference in virulence between WNV strains, the high prevalence of asymptomatic or sub-clinical infections, and the relative infrequency of laboratory-confirmed human infections. Little has been published about human infections with WNV of limited virulence. The vast majority of our current knowledge regarding WNV pathogenesis resulted from animal models (mostly rodent) infected under controlled conditions with a known amount of needle-inoculated virus, which may not accurately reflect the course of a natural infection in humans. Nevertheless, many descriptive accounts have been documented following the course of infection in humans suffering from WN fever and WN encephalitis resulting from a virulent lineage I WNV infection.

WNV-infected mosquitoes transmit the virus to humans following a bloodmeal from the host. During this process, mosquito saliva contaminated with WNV is deposited in the blood and skin tissue. Virus contained within the skin is presumed to infect resident dendritic cells such as Langerhans cells (MHCII+/NLDC145+/E-cadherin+ cells), which then traffic to the draining lymph node [51, 52]. Shortly thereafter, virus amplifies in the tissues and results in a transient, low-level viremia, lasting a few days, and typically wanes with the production of anti-WNV IgM antibodies [53]. Following viremia the virus infects multiple organs in the body of the host, including the spleen, liver, and kidneys. Interestingly, 8 days after onset of symptoms, WNV was detected in the urine (viruria) of a patient with encephalitis [54], which is consistent with animal (hamster) experiments demonstrating viruria [54] and the presence of viral infection in the kidneys [55, 56].

Upon entering the CNS, WNV causes severe neurological disease. WNV may enter the brain though a combination of mechanisms that facilitates viral neuroinvasion, such as direct infection with or without a breakdown of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and/or virus transport along peripheral neurons. High viremia may easily lead to an infection of the brain if the BBB is disrupted and high viremia is correlated with severity of infection in experimentally infected mice [57]. Viremia and high viral titers in the periphery alone do not predict neuroinvasion. Host proteins such as Drak2 (death-associated protein-kinaserelated 2), ICAM-1 (intercellular adhesion molecule), MIP (macrophage migration inhibitory factor) and MMP-9 (matrix metaloproeinase 9) have all been implicated in altering BBB permeability during WNV infection [58-61]. The virus may pass into the CNS without disrupting the BBB [62]. The host’s response to infection may also contribute to WNV pathogenesis. Studies from experimentally infected mice suggest that the innate immune sensing molecule Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) may play a role in WNV invasion of CNS [63], possibly by mediating the upregulation of TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor alpha), thereby resulting in capillary leakage and increased BBB permeability [64]. The pro-inflammatory chemokines/cytokines MCP-5 (monocyte chemoattractant protein 5), MIF, (IP-10) interferon gamma-inducible protein 10, MIC (monokine induced by gamma interferon), IFN-γ (interferon gamma) and TNF-α were all upregulated in the brains of experimentally infected mice, suggesting that the host immune response may be (at least partially) responsible for neurolgical symptoms of the disease [58, 65]. However, an increase in BBB leakage does not accurately predict WNV-induced mortality in hamsters, nor does lethal infection increase BBB permeability in all strains of mice [66]. WNV may enter the brain by directly infecting and retrograde spreading along neurons in the periphery [67]. Entering the brain via infected peripheral neurons is a likely entry route since the level of viremia is low and leakage into the CNS by a breakdown of the BBB is less likely compared to animals with a high titer of circulating WNV in the blood. The discrepancies observed regarding BBB compromise suggest that further research is required to determine the exact mechanism through which WNV enters the CNS.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of WNV infection depends on a number of factors, including environmental conditions, behaviors, and clinical symptoms. Patient history will give crucial clues to diagnosis. For example, if a patient presents with clinical symptoms, including fever and headache, one must consider the distribution of WNV and its mosquito vector. Endemic areas must consider WNV infection, especially during the summer months. Further, the patient history should suggest exposure to mosquitoes through outdoor activities. An initial physical examination will confirm clinical symptoms of fever, headache, myalgia, or the more severe meningitis and flaccid paralysis. Also, the presence of mosquito bites on the skin will assist in diagnosis.

To confirm the initial diagnosis, specific laboratory tests must be ordered (Table 2). To date, the most consistent manner to verify WNV infection is serology [47, 49]. WNV antigen specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) will confirm infection. Serological tests include acute or convalescent samples of serum or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) to determine the WNV-specific antibody profile by ELISA. The best test involves IgM-specific ELISA (MAC-ELISA) in which serum is collected within 8 to 21 days after the appearance of clinical symptoms. This test is commercially available and relatively inexpensive [34]. Also, serology can be performed to analyze immune responses. The presence of reactive lymphocytes or monocytes in CSF samples is indicative of WNV neurologic infection. More dramatically, a massive influx of polymorphonuclear cells occurs. In patients with WNV neuroinvasion, > 40% of cells in the CSF are neutrophils [68]. Plaque reduction and neutralization tests (PRNT) allow for identification of virus specificity. Virology tests can directly confirm the presence of virus. Serum or CSF is collected and virus is amplified within permissive cells and sequenced. This test is time-consuming and expensive. Finally, molecular biology tools can be employed to confirm the presence of virus. The nucleic acid test (NAT) is a powerful tool to detect WNV genomes. Serum or CSF is collected during the initial phases of virus infection can be directly amplified, or used to detect viral RNA by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (Q-RT-PCR) with virus-specific primers.

TnQTable 2. Laboratory Tests and Diagnosis of WNV Infection.

| Test | Positive Results |

|---|---|

| CBC | Anemia, lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia |

| IgM-specific ELISA | WNV-specific IgM antibodies detected |

| PRNT | Known virus stock growth inhibited in tissue culture by serum, indicating neutralizing antibodies |

| NAT | PCR amplification shows presence of WNV genome RNA |

|

Virus isolation/Plaque

assay |

Serum or CSF contain virus as seen in plaque assay |

| CSF analysis | Antibodies and/or virus present by ELISA or plaque assay, Elevated protein and increased polymorphonuclear cells, Negative gram stain |

| EMG/NCS | Severe effects on anterior horn cells |

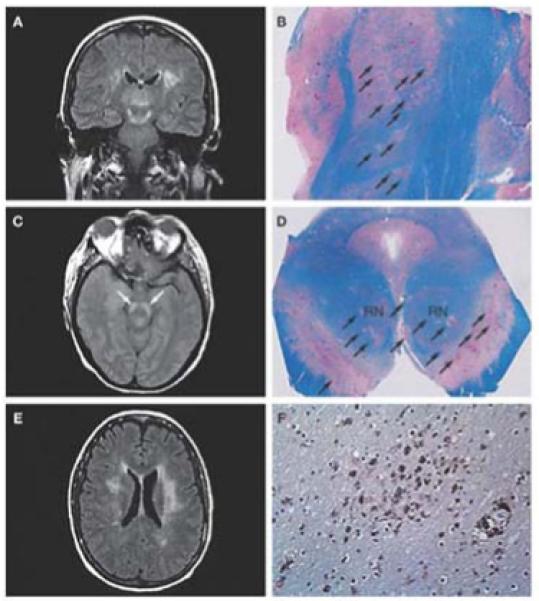

Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging suggests abnormalities in the brain and meninges of WNV-infected patients presenting with CNS disease [46, 69, 70] (Figure 7). The regions of the CNS most commonly affected are basal gangli, thalami, brain stem, ventral horns, and spinal cord. However, the majority of these studies were performed retrospectively. Thus, the results do not provide predictive capabilities to WNV infection.

Figure 7. Radiographic and neuropathologic findings in West Nile virus encephalitis.

(A) Coronal fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) magnetic resonance image shows an area of abnormally increased signal in the thalami, substantia nigra (extending superiorly toward the subthalamic nuclei) and white matter. (B) Corresponding tissue section from the same patient at autopsy 15 days later, stained with Luxol fast blue–periodic acid Schiff for myelin, shows numerous ovoid foci of necrosis and pallor throughout the thalamus and subthalamic nucleus (arrows). (C) Axial proton density image at the level of the midbrain shows a bilaterally increased signal in the substantia nigra (arrows). (D) Corresponding tissue section at autopsy, stained with Luxol fast blue–periodic acid Schiff, illustrates multifocal involvement of the substantia nigra (arrows), with nearly 50% of the area destroyed; the red nuclei are clearly affected. (E) Axial FLAIR image at the level of the lateral ventricle bodies shows a bilaterally increased signal within the white matter. A scan performed approximately 5 months earlier demonstrated an abnormal signal in the left periventricular white matter. This signal increased once West Nile virus encephalitis developed, and the lesions in the right cerebral white matter (left side of photograph) were new. (F) Photomicrograph taken from the right periventricular white matter, immunostained with the HAM56 antibody, shows numerous macrophages, both in perivascular areas (lower right) and diffusely throughout the white matter (center). Permission: Kleinschmidt-DeMaster BK et al. (2004). Arch Neurology 61: 1210-1220.

Differential diagnosis

A number of diseases manifest as symptoms similar to West Nile virus, including the encephalitides viruses (such as JEV and Murray Valley encephalitis virus) and bacterial meningitis. Therefore, differential diagnosis is crucial to determining WNV infection. A differential diagnosis is required when a patient presents with unexplained febrile illness, encephalitis or extreme headache, or meningitis. Thus far, the only manner to differentiate between causes of encephalitis/meningitis is diagnostic and serological laboratory tests to identify the specific pathogen causing the symptoms.

Treatment and long-term outcomes

Currently, patients infected with WNV have limited treatment options. The primary course of action is supportive care. There is no FDA-licensed vaccine to combat WN disease in humans, despite the research of many laboratories and institutions and vaccines available for use in horses.

Furthermore, there are no effective antiviral to combat WNV infection. Two classical antiviral compounds, interferon and ribavirin, showed promising results in vitro [71, 72] but it is unclear if these compounds are effective in patients [73-77]. Passively transferring anti-WNV immunoglobulin has been shown to be effective in mouse and hamster models [78] and may be helpful in patients [79, 80].

Long-term complications (1 year or greater after infection) are common in patients recovering from WNV infection. The most common self-reported symptom is fatigue and weakness, although myalgia, arthralgia, headaches, and neurologic complications, such as altered mental depression, tremors and loss of memory and concentration are not uncommon [81]. There is also evidence from animal models [55, 82, 83] and human autopsies [84, 85] that the virus may persist in some individuals, as measured by isolation of virus or viral genomes or antigen months after infection or symptom presentation. Experimentally infected hamsters show long-term neurological sequela, which appears to coincide with the presence of both viral antigen and genome within areas of the brain showing neuropathology [83]. Although the direct evidence of persistence in humans is limited at this time, many patients have long-lasting WNV-specific IgM titers in the serum and CNS, suggesting that persistent infections may be more common than previously indicated [86-88].

Immunity

Both the innate and adaptive immune responses mounted against WNV are critically important for controlling infection. Type I interferons (alpha and beta) are important for limiting virus levels, reducing neuronal death, and increasing survival [57]. The amount of interferon made by the host in response to infection appears to be (at least in part) dependent upon the strain and/or virulence of the virus; mice infected with lineage I WNV with attenuating mutations produce less type I IFN than mice infected with virulent lineage I WNV [89]. Furthermore, WNV strains that are more resistant to the affects of IFN (like some virulent lineage I viruses) are more virulent than IFN-sensitive stains (like lineage II strains) [90].

The adaptive immune response also plays a role in controlling infection. Studies using WNV-infected genetically engineered knockout mice indicate that both T- [91-96]and B- [97]cells are critical for controlling infection. CD8+ T-cell recruitment to the brain by neurons expressing CXCL10 and by CD40-CD40 ligand interactions help reduce the viral burden in the brain and increase survival in experimentally infected mice [94, 98]. B-cells are activated within the lymph nodes of WNV-infected mice 48-72 hours after infection in an IFNα/β-signaling dependent manner, and B-cells secreting WNV-specific IgM were detected on day 7 post infection [99]. IgM is critically important for the control of early WNV infection, and passive transfer of WNV-specific IgM could protect IgM-deficient mice from lethal WNV infection [100]. Approximately 3-4 days after WNV-specific IgM is detectable, anti-WNV IgG titers are measurable in patients [53]. IgG is the predominant antibody most likely confering long-term immunity against WNV re-infection. Although not enough data exists, immunity against WNV in convalescent patients is presumed to be life-long.

Vaccination

Although no FDA-approved vaccine exists for human use, there are effective, licensed vaccines for the treatment of horses. The success has encouraged others to develop these and other strategies for human vaccines. Currently, there are a number of ongoing clinical trials.

There are several strategies being pursued for WNV vaccine development (Table 3). The first strategy is inoculation of multiple doses of inactivated virus [101, 102]. Fort Dodge Animal Health developed this strategy by formalin inactivating whole virus. This formulation has been approved for horses. The second strategy involves the production of WNV antigens from a heterologous virus backbone. The vectors being used are canarypox (Recombitek™), Yellow fever virus (Chimerivax ™), and Dengue 4 (WNV-DEN4) [103-106]. The Recombitek™ vaccine has been licensed for use in horses. The third approach is DNA vaccination. WNV structural antigens (prM-E) are expressed from DNA plasmids [107]. The final strategy is inoculation with purified viral proteins [108-111]. These proteins can be produced in mammalian cell culture, bacteria, or yeast. Interestingly, a recent study by Seino, et al. compared the efficacy of three available vaccines [112]. Their study showed that horses vaccinated with the live, chimeric virus in the yellow fever or canarypox vectors had fewer clinical signs of WNV disease than animals receiving inactivated virus.

Table 3. WNV vaccines.

A partial list of licensed and preclinical vaccines against WNV.

| Type | Antigen | Sponsor | Stage of Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chimeric (vector) | |||

| Recombitek ™ (canarypox) | WNV-prM-E | Merial | Licensed for horses |

| Chimerivax ™ (yellow fever virus) | WNV-prM-E | Acambis | Phase II |

| WNV-DENV4 (dengue virus 4) | WNV-prM-E | NIAID/NIH | Phase II |

| DNA | |||

| WNV-DIII | WNV-DIII | Multiple labs | Preclinical |

| WNV-E | WNV-E | Multiple labs | Preclinical |

| WNV-prM-E | WNV-prM-E | Multiple labs | Preclinical |

| Inactivated/Killed | |||

| Innovator ™ | Whole virus | Fort Dodge Animal Health | Licensed for horses |

| Subvirion Particles/Virus-like Particles | |||

| WNV-prM-E | WNV-prM-E | Multiple labs | preclinical |

Summary

In summary, WNV infection is a serious threat to public health, especially to the immunocompromised and elderly. The virus is maintained in an enzootic cycle between mosquitoes and birds, with humans and other mammals as incidental hosts. Since its introduction to the Western hemisphere in 1999, WNV has spread across North and South America in fewer than 10 years. The majority of human infections are asymptomatic. However, clinical manifestations range from relatively mild febrile illness to very severe neurological sequelae, including acute flaccid paralysis and encephalitis. Currently, the virus is the most significant cause of viral encephalitis in the United States. Efficient diagnosis of WNV infection requires a detailed history, including potential exposure to contaminated mosquitoes, as well as sensitive serological and virology assays. Recent studies have shed light on virus-host interactions, including pathogenesis and immune evasion. Lastly, there are no prophylactic or therapeutic measures that exist to combat the diseases caused by WNV infection, thus warranting future research.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by T32 Grant #AI060525-04 from the National Institute of Heath (SR), W81XWH-BAA-06-1 and W81XWH-BAA-06-2 (TMR), and CVR Funds (JE).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Shannan L. Rossi, Center for Vaccine Research and Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Ted M. Ross, Department of Microbiology and Genetics, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Jared D. Evans, Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

References

- 1.Gould EA, Solomon T. Pathogenic flaviviruses. Lancet. 2008;371(9611):500–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60238-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindenbach BD, Rice CM. Flaviviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Knipe HP, editor. Fields Virology. Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2001. pp. 991–1041. DM. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schlesinger JJ. Flavivirus nonstructural protein NS1: complementary surprises. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(50):18879–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609522103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leung JY, et al. Role of nonstructural protein NS2A in flavivirus assembly. J Virol. 2008;82(10):4731–41. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00002-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mackenzie JM, et al. Subcellular localization and some biochemical properties of the flavivirus Kunjin nonstructural proteins NS2A and NS4A. Virology. 1998;245(2):203–15. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egloff MP, et al. An RNA cap (nucleoside-2′-O-)-methyltransferase in the flavivirus RNA polymerase NS5: crystal structure and functional characterization. Embo J. 2002;21(11):2757–68. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.11.2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khromykh AA, Kenney MT, Westaway EG. trans-Complementation of flavivirus RNA polymerase gene NS5 by using Kunjin virus replicon-expressing BHK cells. J Virol. 1998;72(9):7270–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7270-7279.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Speight G, et al. Gene mapping and positive identification of the non-structural proteins NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4B and NS5 of the flavivirus Kunjin and their cleavage sites. J Gen Virol. 1988;69(Pt 1):23–34. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-1-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans JD, Seeger C. Differential effects of mutations in NS4B on West Nile virus replication and inhibition of interferon signaling. J Virol. 2007;81(21):11809–16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00791-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu WJ, et al. Inhibition of interferon signaling by the New York 99 strain and Kunjin subtype of West Nile virus involves blockage of STAT1 and STAT2 activation by nonstructural proteins. J Virol. 2005;79(3):1934–42. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1934-1942.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munoz-Jordan JL, et al. Inhibition of alpha/beta interferon signaling by the NS4B protein of flaviviruses. J Virol. 2005;79(13):8004–13. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.13.8004-8013.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munoz-Jordan JL, et al. Inhibition of interferon signaling by dengue virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(24):14333–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2335168100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khromykh AA, Sedlak PL, Westaway EG. cis- and trans-acting elements in flavivirus RNA replication. J Virol. 2000;74(7):3253–63. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.7.3253-3263.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chu JJ, Ng ML. Interaction of West Nile virus with alpha v beta 3 integrin mediates virus entry into cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(52):54533–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410208200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chu JJ, Ng ML. Infectious entry of West Nile virus occurs through a clathrin-mediated endocytic pathway. J Virol. 2004;78(19):10543–55. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10543-10555.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medigeshi GR, et al. West Nile virus entry requires cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains and is independent of alphavbeta3 integrin. J Virol. 2008;82(11):5212–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00008-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Modis Y, et al. Structure of the dengue virus envelope protein after membrane fusion. Nature. 2004;427(6972):313–9. doi: 10.1038/nature02165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mukhopadhyay S, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG. A structural perspective of the flavivirus life cycle. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3(1):13–22. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mackenzie JM, Westaway EG. Assembly and maturation of the flavivirus Kunjin virus appear to occur in the rough endoplasmic reticulum and along the secretory pathway, respectively. J Virol. 2001;75(22):10787–99. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.22.10787-10799.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Westaway EG, Ng ML. Replication of flaviviruses: separation of membrane translation sites of Kunjin virus proteins and of cell proteins. Virology. 1980;106(1):107–22. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(80)90226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Westaway EG, Mackenzie JM, Khromykh AA. Replication and gene function in Kunjin virus. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2002;267:323–51. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-59403-8_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Westaway EG, et al. Ultrastructure of Kunjin virus-infected cells: colocalization of NS1 and NS3 with double-stranded RNA, and of NS2B with NS3, in virus-induced membrane structures. J Virol. 1997;71(9):6650–61. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6650-6661.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ng ML, et al. Immunofluorescent sites in vero cells infected with the flavivirus Kunjin. Arch Virol. 1983;78(3-4):177–90. doi: 10.1007/BF01311313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bartenschlager R, Miller S. Molecular aspects of Dengue virus replication. Future Microbiol. 2008;3:155–65. doi: 10.2217/17460913.3.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Welsch S, et al. Composition and three-dimensional architecture of the dengue virus replication and assembly sites. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5(4):365–75. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyanari Y, et al. The lipid droplet is an important organelle for hepatitis C virus production. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(9):1089–97. doi: 10.1038/ncb1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyanari Y, et al. Hepatitis C virus non-structural proteins in the probable membranous compartment function in viral genome replication. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(50):50301–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305684200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bondre VP, et al. West Nile virus isolates from India: evidence for a distinct genetic lineage. J Gen Virol. 2007;88(Pt 3):875–84. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82403-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Intrauterine West Nile virus infection--New York, 2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51(50):1135–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Intrauterine West Nile virus infection--New York, 2002. JAMA. 2003;289(3):295–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alpert SG, Fergerson J, Noel LP. Intrauterine West Nile virus: ocular and systemic findings. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136(4):733–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(03)00452-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hinckley AF, O’Leary DR, Hayes EB. Transmission of West Nile virus through human breast milk seems to be rare. Pediatrics. 2007;119(3):e666–71. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Leary DR, et al. Birth outcomes following West Nile Virus infection of pregnant women in the United States: 2003-2004. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):e537–45. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petersen LR, Marfin AA. West Nile virus: a primer for the clinician. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(3):173–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-3-200208060-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iwamoto M, et al. Transmission of West Nile virus from an organ donor to four transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(22):2196–203. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Biggerstaff BJ, Petersen LR. Estimated risk of transmission of the West Nile virus through blood transfusion in the US, 2002. Transfusion. 2003;43(8):1007–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2003.00480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Detection of West Nile virus in blood donations--United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(32):769–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smithburn KC, Hughes TP, Burke AW, Paul JH. A neurotropic virus isolated from the blood of a native of Uganda. Am. J. Trop. Medicine. 1940;20:471–492. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murgue B, et al. West Nile in the Mediterranean basin: 1950-2000. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;951:117–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb02690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hayes CG. West Nile virus: Uganda, 1937, to New York City, 1999. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;951:25–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb02682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bin H, et al. West Nile fever in Israel 1999-2000: from geese to humans. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;951:127–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb02691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Platonov AE, et al. Outbreak of West Nile virus infection, Volgograd Region, Russia, 1999. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7(1):128–32. doi: 10.3201/eid0701.010118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsai TF, et al. West Nile encephalitis epidemic in southeastern Romania. Lancet. 1998;352(9130):767–71. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)03538-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lanciotti RS, et al. Origin of the West Nile virus responsible for an outbreak of encephalitis in the northeastern United States. Science. 1999;286(5448):2333–7. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5448.2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mostashari F, et al. Epidemic West Nile encephalitis, New York, 1999: results of a household-based seroepidemiological survey. Lancet. 2001;358(9278):261–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05480-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brilla R, et al. Clinical and neuroradiologic features of 39 consecutive cases of West Nile Virus meningoencephalitis. J Neurol Sci. 2004;220(1-2):37–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hayes EB, Sejvar JJ, Zaki SR, Lanciotti RS, Bode AV, Campbell GL. Virology, pathology, and clinical manifestations of West Nile virus disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11(8):1174–9. doi: 10.3201/eid1108.050289b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petersen LR, Roehrig JT, Hughes JM. West Nile virus encephalitis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16):1225–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMo020128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tyler KL. West Nile virus infection in the United States. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(8):1190–5. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.8.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Campbell GL, et al. West Nile virus. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2(9):519–29. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(02)00368-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Byrne S, Halliday GM, Johnston LJ, King NJ. Interleukin-1 beta but not tumor necrosis factor is involved in West Nile virus-induced Langerhans cell migration from the skin in C57BL/6 mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117(3):702–9. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnston L, Halliday GM, King NJ. Langerhans cells migrate to local lymph nodes following cutaneous infection with an arbovirus. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;114(3):560–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Busch MP, et al. Virus and antibody dynamics in acute west nile virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2008;198(7):984–93. doi: 10.1086/591467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tonry JH, et al. Persistent shedding of West Nile virus in urine of experimentally infected hamsters. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72(3):320–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tesh RB, et al. Persistent West Nile virus infection in the golden hamster: studies on its mechanism and possible implications for other flavivirus infections. J Infect Dis. 2005;192(2):287–95. doi: 10.1086/431153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ding X, et al. Nucleotide and amino acid changes in West Nile virus strains exhibiting renal tropism in hamsters. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73(4):803–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Samuel MA, Diamond MS. Alpha/beta interferon protects against lethal West Nile virus infection by restricting cellular tropism and enhancing neuronal survival. J Virol. 2005;79(21):13350–61. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.21.13350-13361.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arjona A, et al. Abrogation of macrophage migration inhibitory factor decreases West Nile virus lethality by limiting viral neuroinvasion. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(10):3059–66. doi: 10.1172/JCI32218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dai J, et al. Icam-1 participates in the entry of west nile virus into the central nervous system. J Virol. 2008;82(8):4164–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02621-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang P, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase 9 facilitates West Nile virus entry into the brain. J Virol. 2008;82(18):8978–85. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00314-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang S, et al. Drak2 contributes to West Nile virus entry into the brain and lethal encephalitis. J Immunol. 2008;181(3):2084–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Verma S, et al. West Nile virus infection modulates human brain microvascular endothelial cells tight junction proteins and cell adhesion molecules: Transmigration across the in vitro blood-brain barrier. Virology. 2009;385(2):425–33. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang T, Town T, Alexopoulou L, Anderson JF, Fikrig E, Flavell RA. Toll-like receptor 3 mediates West Nile virus entry into the brain causing lethal encephalitis. Nat Med. 2004;10(12):1366–73. doi: 10.1038/nm1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Diamond MS, Klein RS. West Nile virus: crossing the blood-brain barrier. Nat Med. 2004;10(12):1294–5. doi: 10.1038/nm1204-1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Garcia-Tapia D, et al. West Nile virus encephalitis: sequential histopathological and immunological events in a murine model of infection. J Neurovirol. 2007;13(2):130–8. doi: 10.1080/13550280601187185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Morrey JD, et al. Increased blood-brain barrier permeability is not a primary determinant for lethality of West Nile virus infection in rodents. J Gen Virol. 2008;89(Pt 2):467–73. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83345-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Samuel MA, et al. Axonal transport mediates West Nile virus entry into the central nervous system and induces acute flaccid paralysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(43):17140–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705837104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tyler KL, et al. CSF findings in 250 patients with serologically confirmed West Nile virus meningitis and encephalitis. Neurology. 2006;66(3):361–5. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000195890.70898.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Petropoulou KA, et al. West Nile virus meningoencephalitis: MR imaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26(8):1986–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ali M, et al. West Nile virus infection: MR imaging findings in the nervous system. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26(2):289–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rossi SL, et al. Adaptation of West Nile virus replicons to cells in culture and use of replicon-bearing cells to probe antiviral action. Virology. 2005;331(2):457–70. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Anderson J, Rahal JJ. Efficacy of interferon alpha-2b and ribavirin against West Nile virus in vitro. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8(1):107–8. doi: 10.3201/eid0801.010252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chan-Tack KM, Forrest G. Failure of interferon alpha-2b in a patient with West Nile virus meningoencephalitis and acute flaccid paralysis. Scand J Infect Dis. 2005;37(11-12):944–6. doi: 10.1080/00365540500262690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chowers MY, et al. Clinical characteristics of the West Nile fever outbreak, Israel, 2000. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7(4):675–8. doi: 10.3201/eid0704.010414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kalil AC, et al. Use of interferon-alpha in patients with West Nile encephalitis: report of 2 cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(5):764–6. doi: 10.1086/427945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sayao AL, et al. Calgary experience with West Nile virus neurological syndrome during the late summer of 2003. Can J Neurol Sci. 2004;31(2):194–203. doi: 10.1017/s031716710005383x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Weiss D, et al. Clinical findings of West Nile virus infection in hospitalized patients, New York and New Jersey, 2000. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7(4):654–8. doi: 10.3201/eid0704.010409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Morrey JD, et al. Efficacy of orally administered T-705 pyrazine analog on lethal West Nile virus infection in rodents. Antiviral Res. 2008;80(3):377–9. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ben-Nathan D, et al. Using high titer West Nile intravenous immunoglobulin from selected Israeli donors for treatment of West Nile virus infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Saquib R, et al. West Nile virus encephalitis in a renal transplant recipient: the role of intravenous immunoglobulin. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52(5):e19–21. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sejvar JJ. The long-term outcomes of human West Nile virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(12):1617–24. doi: 10.1086/518281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pogodina VV, et al. Study on West Nile virus persistence in monkeys. Arch Virol. 1983;75(1-2):71–86. doi: 10.1007/BF01314128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Siddharthan V, et al. Persistent West Nile virus associated with a neurological sequela in hamsters identified by motor unit number estimation. J Virol. 2009;83(9):4251–61. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00017-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Penn RG, et al. Persistent neuroinvasive West Nile virus infection in an immunocompromised patient. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(5):680–3. doi: 10.1086/500216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brenner W, et al. West Nile Virus encephalopathy in an allogeneic stem cell transplant recipient: use of quantitative PCR for diagnosis and assessment of viral clearance. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;36(4):369–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kapoor H, et al. Persistence of West Nile Virus (WNV) IgM antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with CNS disease. J Clin Virol. 2004;31(4):289–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Prince HE, et al. Persistence of West Nile virus-specific antibodies in viremic blood donors. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2007;14(9):1228–30. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00233-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Roehrig JT, et al. Persistence of virus-reactive serum immunoglobulin m antibody in confirmed west nile virus encephalitis cases. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9(3):376–9. doi: 10.3201/eid0903.020531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rossi SL, et al. Mutations in West Nile virus nonstructural proteins that facilitate replicon persistence in vitro attenuate virus replication in vitro and in vivo. Virology. 2007;364(1):184–95. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Keller BC, et al. Resistance to alpha/beta interferon is a determinant of West Nile virus replication fitness and virulence. J Virol. 2006;80(19):9424–34. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00768-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shrestha B, Diamond MS. Role of CD8+ T cells in control of West Nile virus infection. J Virol. 2004;78(15):8312–21. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.15.8312-8321.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shrestha B, Samuel MA, Diamond MS. CD8+ T cells require perforin to clear West Nile virus from infected neurons. J Virol. 2006;80(1):119–29. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.1.119-129.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shrestha B, et al. Gamma interferon plays a crucial early antiviral role in protection against West Nile virus infection. J Virol. 2006;80(11):5338–48. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00274-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sitati EM, Diamond MS. CD4+ T-cell responses are required for clearance of West Nile virus from the central nervous system. J Virol. 2006;80(24):12060–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01650-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wang T, et al. IFN-gamma-producing gamma delta T cells help control murine West Nile virus infection. J Immunol. 2003;171(5):2524–31. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wang Y, et al. CD8+ T cells mediate recovery and immunopathology in West Nile virus encephalitis. J Virol. 2003;77(24):13323–34. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.24.13323-13334.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Diamond MS, et al. B cells and antibody play critical roles in the immediate defense of disseminated infection by West Nile encephalitis virus. J Virol. 2003;77(4):2578–86. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.4.2578-2586.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Klein RS, et al. Neuronal CXCL10 directs CD8+ T-cell recruitment and control of West Nile virus encephalitis. J Virol. 2005;79(17):11457–66. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.17.11457-11466.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Purtha WE, et al. Early B-cell activation after West Nile virus infection requires alpha/beta interferon but not antigen receptor signaling. J Virol. 2008;82(22):10964–74. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01646-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Diamond MS, et al. A critical role for induced IgM in the protection against West Nile virus infection. J Exp Med. 2003;198(12):1853–62. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ng T, et al. Equine vaccine for West Nile virus. Dev Biol (Basel) 2003;114:221–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Samina I, et al. An inactivated West Nile virus vaccine for domestic geese-efficacy study and a summary of 4 years of field application. Vaccine. 2005;23(41):4955–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Arroyo J, et al. ChimeriVax-West Nile virus live-attenuated vaccine: preclinical evaluation of safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy. J Virol. 2004;78(22):12497–507. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.22.12497-12507.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Minke JM, et al. Recombinant canarypoxvirus vaccine carrying the prM/E genes of West Nile virus protects horses against a West Nile virus-mosquito challenge. Arch Virol Suppl. 2004;(18):221–30. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-0572-6_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Monath TP, et al. A live, attenuated recombinant West Nile virus vaccine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(17):6694–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601932103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pletnev AG, et al. Molecularly engineered live-attenuated chimeric West Nile/dengue virus vaccines protect rhesus monkeys from West Nile virus. Virology. 2003;314(1):190–5. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00450-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Davis BS, et al. West Nile virus recombinant DNA vaccine protects mouse and horse from virus challenge and expresses in vitro a noninfectious recombinant antigen that can be used in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. J Virol. 2001;75(9):4040–7. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.9.4040-4047.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chu JH, Chiang CC, Ng ML. Immunization of flavivirus West Nile recombinant envelope domain III protein induced specific immune response and protection against West Nile virus infection. J Immunol. 2007;178(5):2699–705. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ledizet M, et al. A recombinant envelope protein vaccine against West Nile virus. Vaccine. 2005;23(30):3915–24. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lieberman MM, et al. Preparation and immunogenic properties of a recombinant West Nile subunit vaccine. Vaccine. 2007;25(3):414–23. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Qiao M, et al. Induction of sterilizing immunity against West Nile Virus (WNV), by immunization with WNV-like particles produced in insect cells. J Infect Dis. 2004;190(12):2104–8. doi: 10.1086/425933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Seino KK, et al. Comparative efficacies of three commercially available vaccines against West Nile Virus (WNV) in a short-duration challenge trial involving an equine WNV encephalitis model. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2007;14(11):1465–71. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00249-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]